3.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

The

Table 1 lists three different machine learning models along with their parameters and corresponding values. Here's an analysis of each model and its parameters:

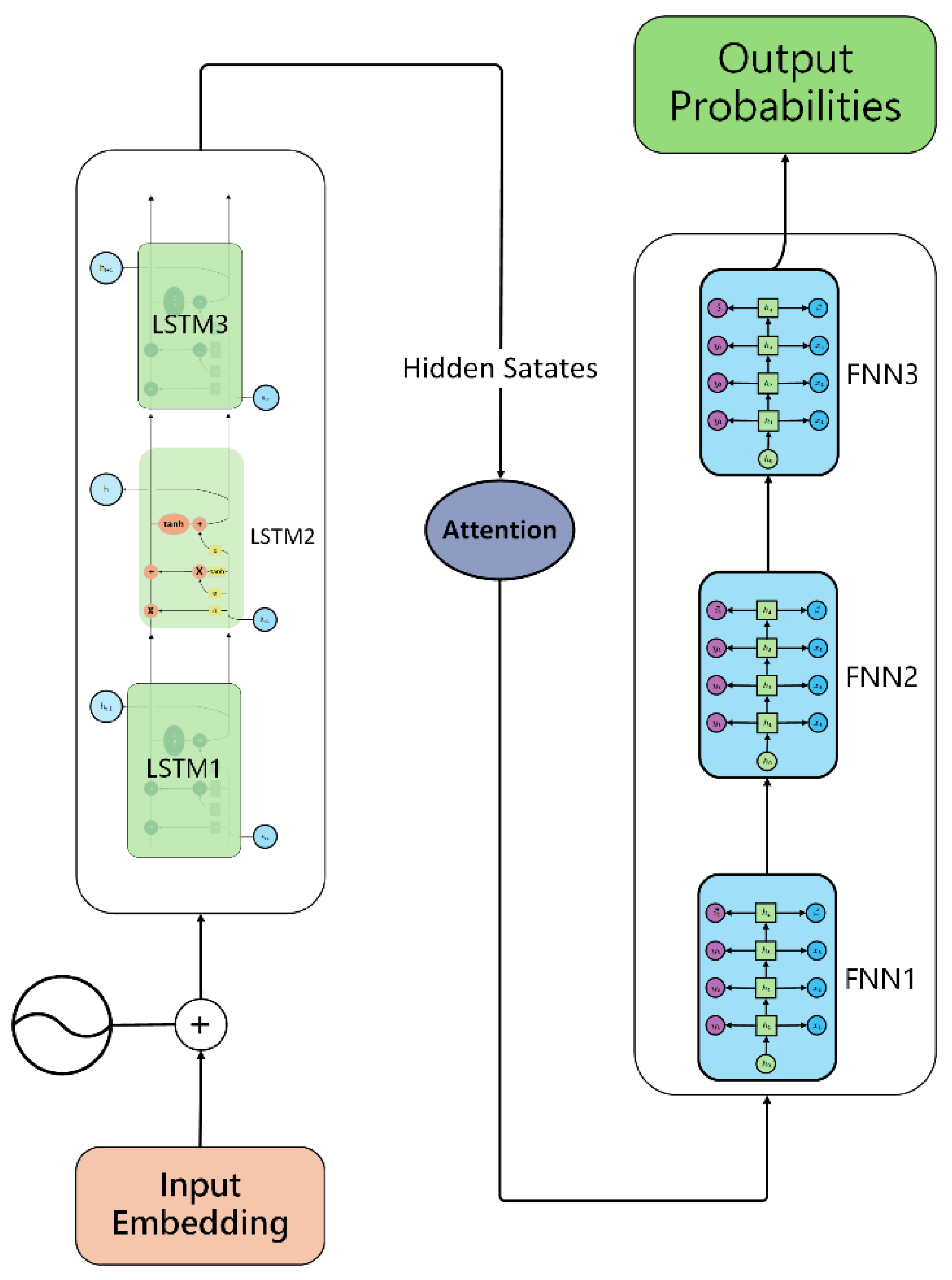

The input layer size is set to 1, indicating that only one feature is input at each time step. The hidden layer size is 512, meaning that each hidden layer contains 512 neurons. The number of layers is 4, suggesting that the LSTM network consists of 4 hidden layers. The sequence length is 50, which typically refers to the number of time steps in the input sequence. The learning rate, which is set to 2e-5, is utilised to regulate the rate at which the model updates its weights during the training process.

The output layer is characterised by a size of 1, signifying that the network produces a solitary output value. The network comprises a total of three layers, encompassing the input layer, a hidden layer, and the output layer. The learning rate is configured to 2e-5, aligning with the LSTM model, and it governs the rate at which weights are updated during the training process.

N_estimator: The number of estimators is 100, referring to the number of weak learners used in the AdaBoost algorithm. Learning rate: The value of the learning rate is 0.1, the function of which is to regulate the contribution of each weak learner. Random state: The random state is 42, which is employed to ensure the reproducibility of results, especially in the process of data splitting and model training.

These parameters are of pivotal significance for the performance and training process of the models. For instance, the size and number of hidden layers affect the complexity and learning capacity of the model, while the learning rate influences the stability and convergence speed during training. The parameters for the AdaBoost Regressor are outlined in

Table 1.

The

Table 2 illustrates three network models, accompanied by their associated parameters and corresponding values. The LSTM model is characterized by the following parameters: The input layer is sized 1, indicating that the dimension or the number of features of the input data is 1.The size of the hidden layers is 512, implying that each hidden layer contains 512 neurons. A larger hidden layer size may enable the model to learn more complex patterns, but it may also increase the computational cost and the risk of overfitting. The number of layers is 4. More layers allow the model to perform more in-depth feature extraction and learning, but it may also bring about problems such as overfitting, which requires appropriate regularization and other means to control. The length of the sequence is 50, which may be related to the sequential nature of the input data. In the context of time series data, for instance, 50 may denote the sequence length of 50 time steps input to the model on each occasion. The learning rate is set to 2e-5, a value which, while typically ensuring stability during training, can result in a reduced convergence speed. With regard to the FNN model:

The size of the hidden layer is 512, which has a similar impact on the model's learning ability as the hidden layer size of the LSTM. The output layer is 1, indicating that the output of this model is a single value, which may be suitable for regression and other tasks. The number of layers is 3, a relatively shallow network structure, which may have different trade-offs in learning ability and computational complexity.

The learning rate is set to 2e-5, and it is anticipated that this will have a comparable effect on the characteristics of the training process to that observed in the LSTM model. The N_estimator is set to 100, which may be indicative of the number of estimators in the model. For instance, in the context of ensemble learning, 100 base learners may be employed.

In the context of the Gradient Boosting Regressor model, the learning rate is set at 0.1, which is notably higher than the rates employed in LSTM and FNN models. This may result in more rapid weight updates during the training phase.

The

Table 3 shows that the Input Layer Size is defined as follows: The input layer size is set to 1, indicating that the network processes a single feature at each time step, a common configuration for univariate time series data.

Hidden Layer Size: The hidden layer size is set to 512, suggesting a substantial capacity for the network to capture complex patterns within the data through a significant number of neurons. Number of Layers: With four layers specified, the LSTM network is configured to have multiple hidden layers, which can enhance its ability to learn and represent temporal dependencies in the data. Learning Rate: The learning rate is set to 2e-5, a conservative value that ensures the model's weights are updated gradually during training, potentially leading to more stable convergence and preventing overshooting. Finally, the sequence length is set to 50, which is a standard value that allows the network to effectively utilise a moderate range of past data points when making predictions. The sequence length is set to 50, which defines the number of time steps that the LSTM considers when making predictions, allowing it to leverage information from a moderate window of past data points.

This format provides a clear and concise description of each hyperparameter, explaining its role and the implications of its value in the context of the LSTM network's performance.

The

Table 4 presents three network models (LSTM, FNN, KNN) along with their relevant parameters and corresponding values.

The table summarizes key hyperparameters for LSTM, FNN, and KNN models, highlighting LSTM's deep architecture with 4 layers and a hidden size of 512 for complex temporal data processing, FNN's single output for regression tasks with a similar hidden size, and KNN's flexible boosting stages and learning rates suited for diverse regression challenges, with a focus on balancing model complexity and performance.

The

Table 5 details the configurations of three machine learning models. The LSTM, designed for temporal data, has an input layer for a single feature, 512-neuron hidden layers across 4 layers, and a sequence length of 50, with a 2e-5 learning rate for stable training. The FNN, with a comparable 512-neuron hidden layer, features a [

4,

4,

3] layered structure for complex data representation and shares the LSTM's learning rate. The K-Neighbors Regressor is configured with 5 neighbors to balance local data consideration with generalization. These settings are tailored for optimal learning and prediction accuracy across the models.

As illustrated in

Table 6, three network models (LSTM, FNN, Cat Boost Regressor) are presented, accompanied by their respective parameters and values.

For the LSTM model, the input layer size is set to 1, denoting the dimension or feature count of the input data.The size of the hidden layer is 512, which, although larger sizes may facilitate the learning of complex patterns, can increase costs and the risk of overfitting.The layers are as follows: 4, for in-depth feature extraction and learning, may cause overfitting.he sequence length of 50 is related to the input data's sequential nature.The learning rate of 2e-5 is a crucial parameter, as it ensures stability during training while moderating convergence.

For the Feedforward Neural Network (FNN):Hidden layer size: 512, similar impact on learning ability.The output layer: 1, which is suitable for regression.The layers are as follows: [3, 3, 4], with trade-offs in learning and complexity.The learning rate of 2e-5 has a discernible impact on the training process.The iterations are as follows: 1000, with the possibility of overfitting or prolonged training with higher values.

For the Cat Boost Regressor:Learning rate: 0.1, a larger value may facilitate more rapid weight updates but can also result in oscillations.The depth parameter, set at 6, has been observed to facilitate the learning of complex relationships; however, it has also been noted to increase the risk of overfitting.Finally, the verbosity parameter, set at 100, is related to the degree of information provided by the model.

It is imperative to note that these settings have a profound impact on the performance of the model, its operational speed, and its capacity for generalisation. It is recommended that these settings be adjusted and optimized based on the specific characteristics of the data and the intended tasks, with the objective of achieving the best possible outcome. In this regard, it is essential to take into account factors such as the complexity of the data, the available computing resources, and the associated time costs.

The

Table 7 provides a concise overview of the hyperparameter settings for three machine learning models: LSTM, FNN, and Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. The LSTM model is configured with an input layer size of 1, 512 neurons in the hidden layers, 4 layers deep, a sequence length of 50, and a learning rate of 2e-5, making it suitable for capturing temporal dependencies in data. The FNN, with a single output and 512 neurons in its hidden layer, is set with 3 layers and the same learning rate of 2e-5 as the LSTM, indicating a design for complex pattern recognition with a focus on regression tasks. The Gradient Boosting Decision Tree is parameterized with 100 estimators, a learning rate of 0.1, a maximum depth of 3, and a random state of 42, which suggests a robust setup for handling various types of data and avoiding overfitting through controlled randomness. These configurations highlight a balance between model complexity and generalization capabilities.

The provided

Table 8 outlines the optimized hyperparameters for three machine learning models: LSTM, FNN, and Optimal Random Forest Regressor. The LSTM configuration is designed to handle time-series data effectively, with an input layer dimension of 2, a substantial hidden layer size of 256, a model depth of 4 layers, a sequence length of 5, and an aggressive learning rate of 1e-4 to facilitate faster convergence. The FNN, with its 256-neuron hidden layer, single output neuron, and a total of 3 layers, is configured with a conservative learning rate of 2e-5, likely to ensure stable learning for its regression tasks. The Optimal Random Forest Regressor stands out with a high number of 1316 estimators, a considerable depth of 312, and specific criteria for minimum leaf size (5) and minimum split (2), suggesting a model that has been meticulously tuned for accuracy and generalization. This ensemble model's parameters indicate a preference for a complex model structure to capture intricate data relationships.

The

Table 9 presents three network models (LSTM, FNN, XG-Boost Regressor) along with their relevant parameters and corresponding values.

For the LSTM model: The size of the input layer is 1, indicating that the dimension or the number of features of the input data is 1.The size of the hidden layers is 512, meaning each hidden layer has 512 neurons. A larger hidden layer size may enable the model to learn more complex patterns, but it may also increase the computational cost and the risk of overfitting. The number of layers is 4. More layers allow the model to perform more in-depth feature extraction and learning, but it may also bring about issues such as overfitting, which requires appropriate regularization and other means to control. The length of the sequence is 49, which may be related to the sequential nature of the input data. For example, when dealing with time series data, 49 may represent the sequence length of 49 time steps input to the model each time. The learning rate is 2e-5. A smaller learning rate usually makes the training process more stable, but it may lead to a slower convergence speed.

For the FNN model: The size of the hidden layer is 512, which has a similar impact on the model's learning ability as the hidden layer size of the LSTM. The output layer is 1, indicating that the output of this model is a single value, which may be suitable for regression and other tasks. The number of layers is 5, a relatively deeper network structure, which has different trade-offs in learning ability and computational complexity. The learning rate is 2e-5, and the characteristics of the training process will be similarly affected N estimators is [100, 200], which may be related to the range of the number of estimators in the model.

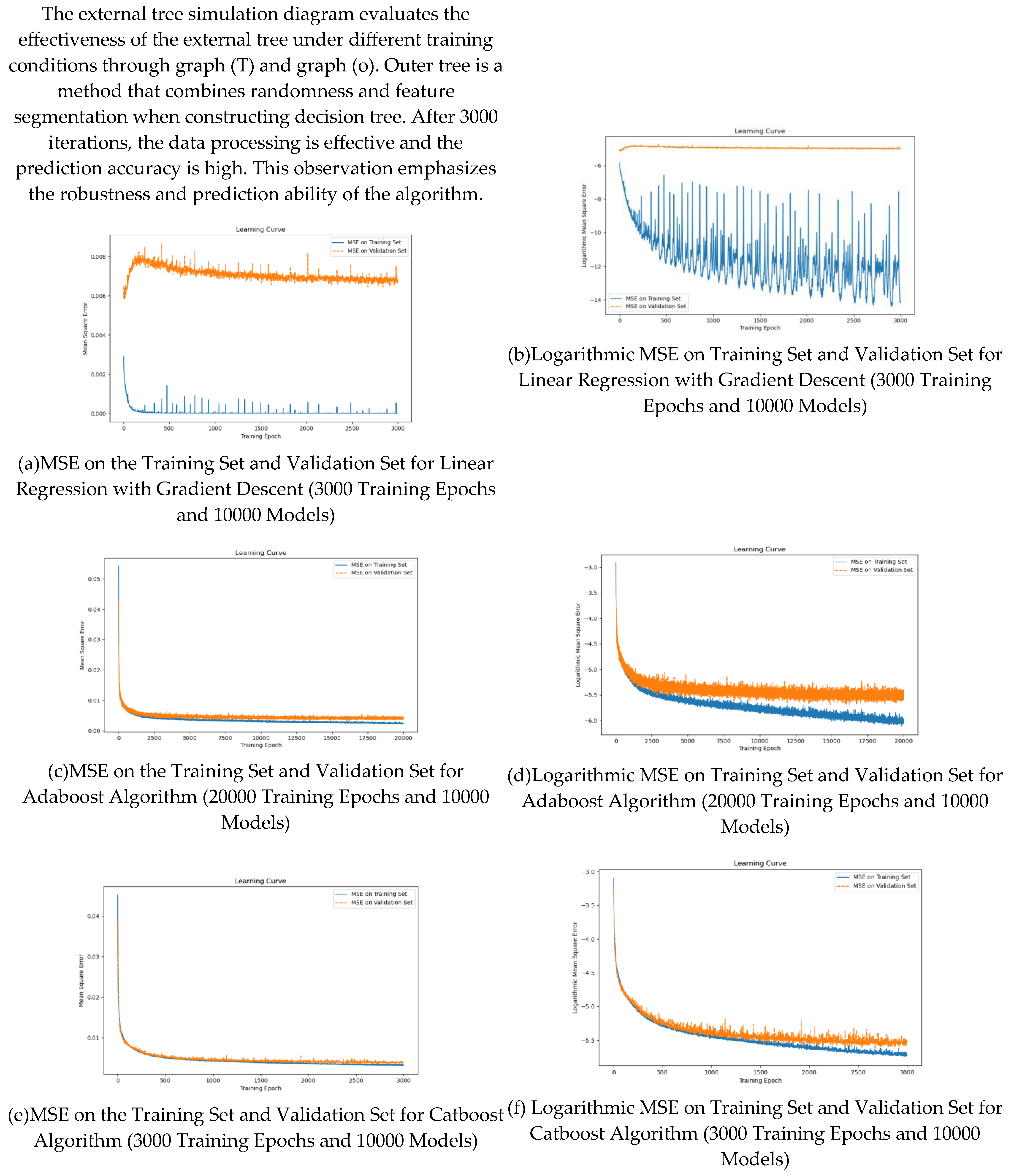

3.2. Comparison of the effectiveness of different machine learning algorithms

The Figures (a) and (b) illustrate the training process of linear regression model using gradient descent. As the number of iterations increases, the loss function decreases significantly, indicating that the model gradually learns and adapts to the data set. When the number of iterations reaches 3000, the model converges to the minimum loss value, which indicates that it successfully captures the linear relationship in the data and is ready for the accurate prediction task.

The performance trajectory of AdaBoost algorithm is shown in figures (c) and (d). The ensemble method aggregates weak learners into robust classifiers. With the increase of the number of weak learners, the classification accuracy is significantly improved. At 3000 iterations, the accuracy of the model is stable at a significant high level, which emphasizes the effectiveness of AdaBoost in enhancing the collective prediction ability of multiple weak classifiers to improve the overall performance.

Figures (E) and (f) show the performance of catboost in different training operations. The model can deal with classification features well, and the prediction error decreases with the increase of iteration times. After 3000 iterations, the model achieved satisfactory results, effectively managed the classification input, and provided accurate prediction.

Gbdt simulation diagrams (g) and (H) illustrate the training dynamics of the gradient lifting decision tree algorithm. Gbdt is an integrated technology that gradually establishes a decision tree to improve prediction. The results show that the consistency of prediction error decreases with the increase of the tree. After 3000 experiments, gbdt successfully identifies the complex patterns in the data, which provides a solid foundation for reliable prediction results.

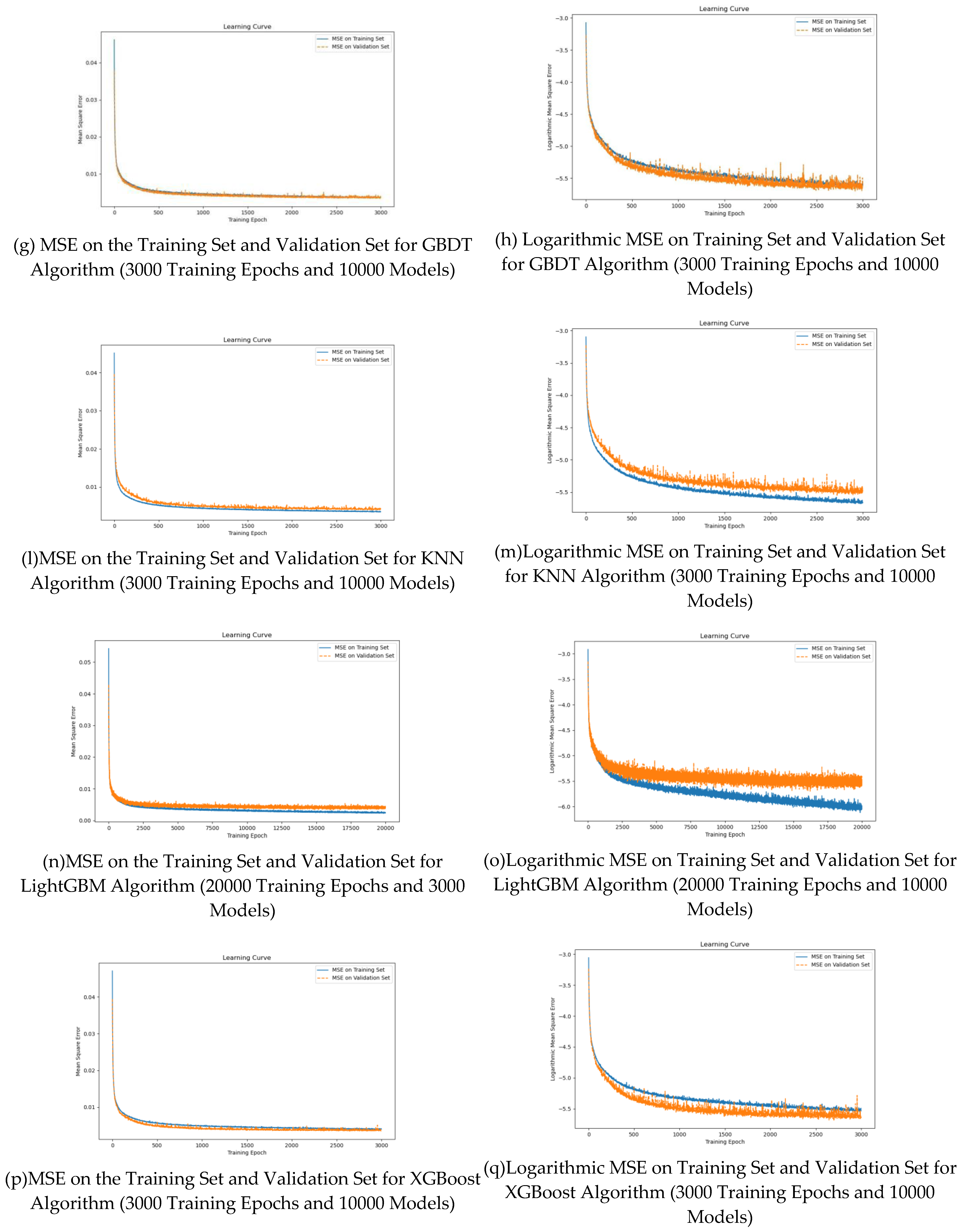

Figures (L) and (m) test the performance of KNN algorithm under different parameter configurations. KNN algorithm depends on the closeness between samples for classification or regression, and shows different prediction accuracy under different K values. Through 3000 iterations, the model can select the best K value according to the data distribution, so as to optimize the prediction performance.

Figures (n) and (o) show the effectiveness of lightgbm in different training iterations. A notable feature of lightgbm is its speed and memory efficiency. As the number of iterations increases to 20000, the prediction error of lightgbm decreases significantly, and the accuracy and stability of the model are improved.

The prediction performance of xgboost regression model in different training stages is described in detail with (P) and (q) labeled graphs. Xgboost is a machine learning algorithm known for its effectiveness in processing large-scale data. After 3000 iterations, the prediction error is significantly reduced. This decline means the effective fitting of data, and emphasizes the robust prediction ability of the algorithm.

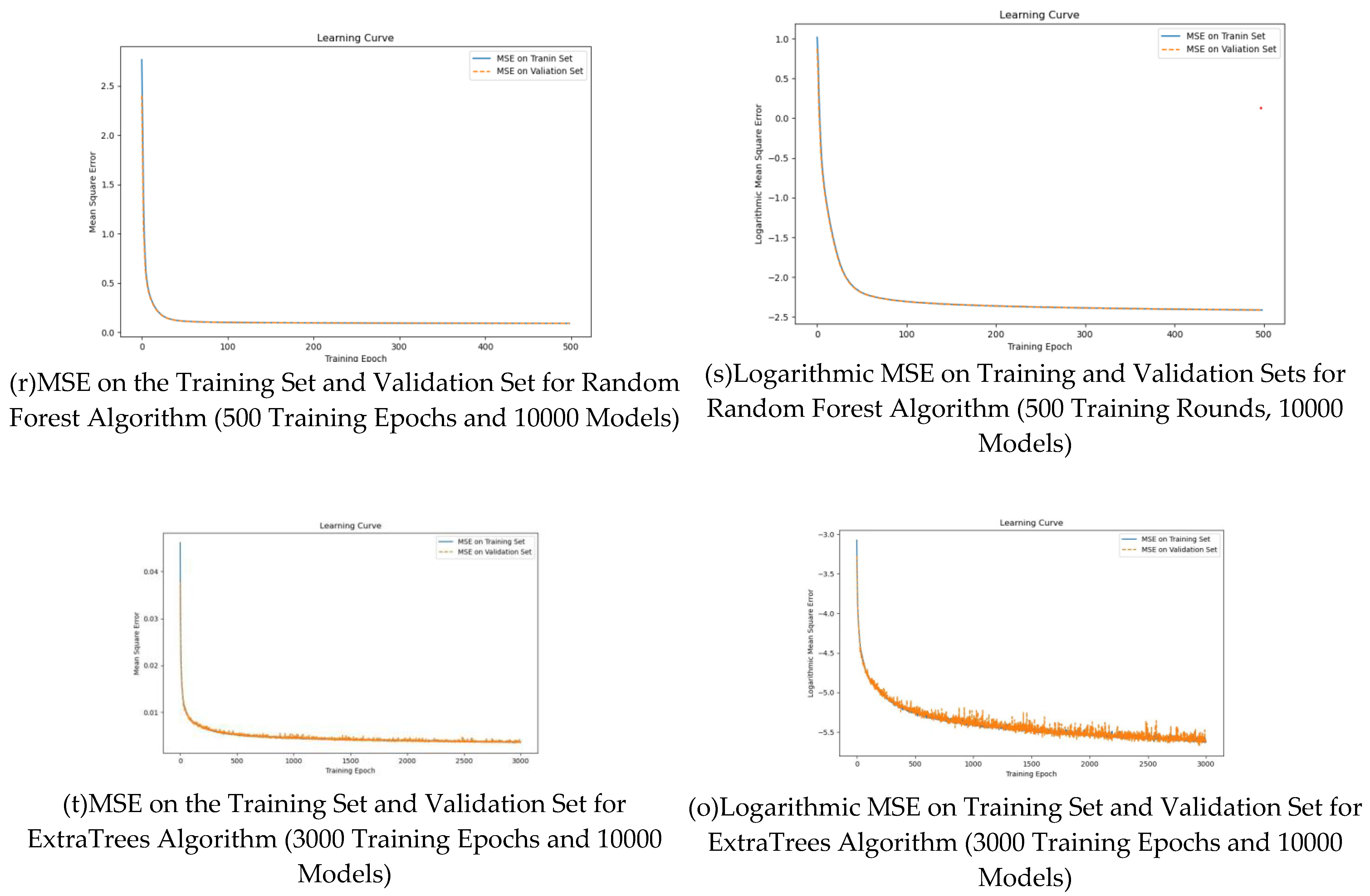

Stochastic Forest simulation is to train stochastic EST algorithm on a large number of data sets. The training results are shown in figures (R) and (s). Random forest algorithm is a comprehensive method that uses multiple decision trees to aggregate their predictions by voting or averaging. Experiments show that the algorithm achieves high prediction accuracy through 20000 data sets and 50000 iterations. The results show that the model can make full use of data information, reduce the over fitting ability, and produce reliable prediction results.