3.1. Subsection

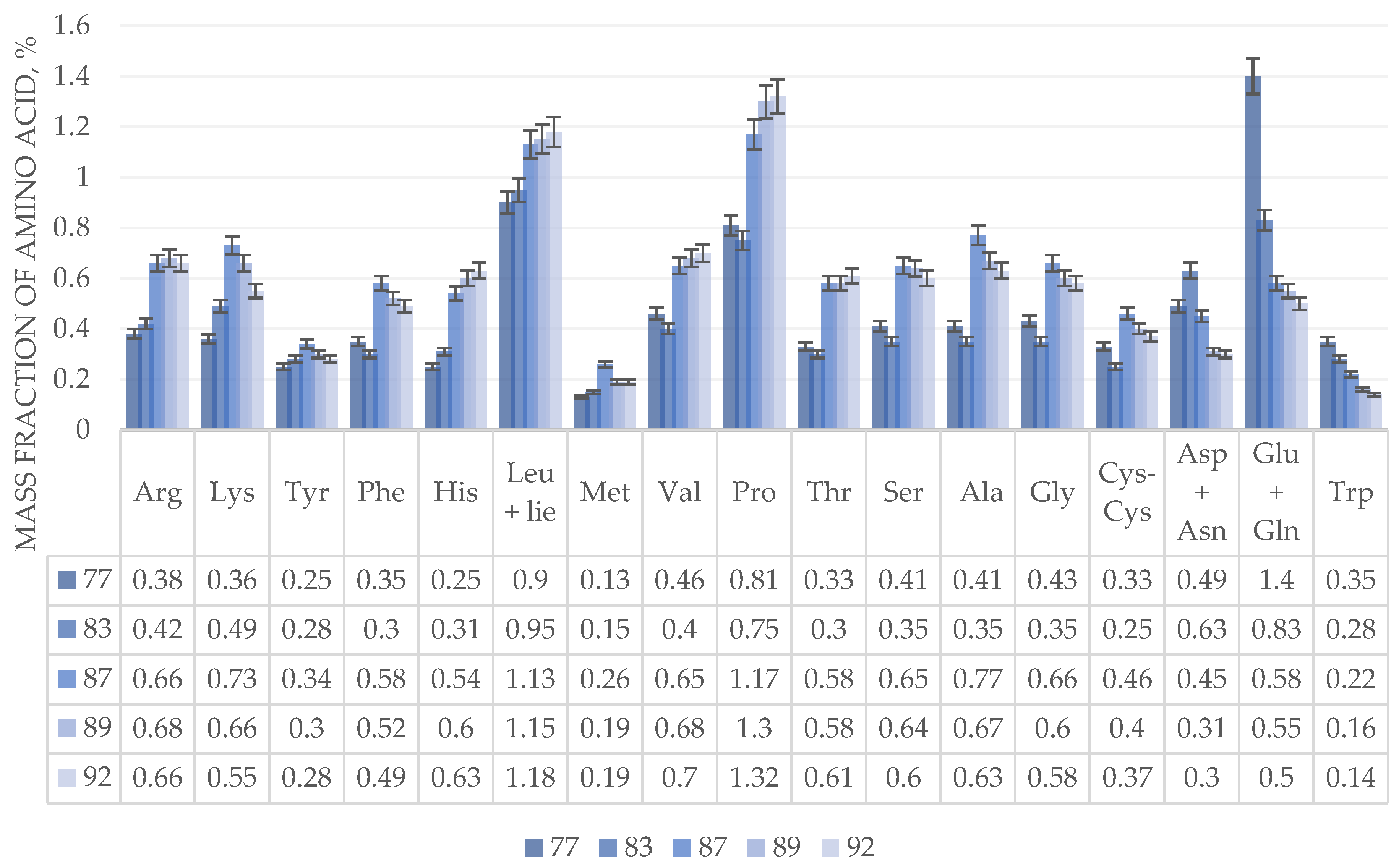

The results of the study show that the milk ripeness stage (stage 77 on the BBCH scale) has the highest content of glutamic acid, glutamine and tryptophan, and during the transition to wax ripeness there is a sharp decrease, which continues after full ripeness.

The content of aspartic acid and asparagine in the early wax ripeness phase (83 on the BBCH scale) reaches its peak values, after which, like glutamic acid, glutamine and tryptophan, they decrease before and after full ripeness.

The highest amount of amino acids lysine, tyrosine, phenylalanine, methionine, alanine, glycine, cystine in the grain heap of wheat of the Admiral variety is observed at the stage of hard wax ripeness (stage 88 on the BBCH scale), after which there is a smooth decrease before and after full ripeness. The content of histidine, leucine, isoleucine, valine, proline, threonine, and serine increases throughout the growing season.

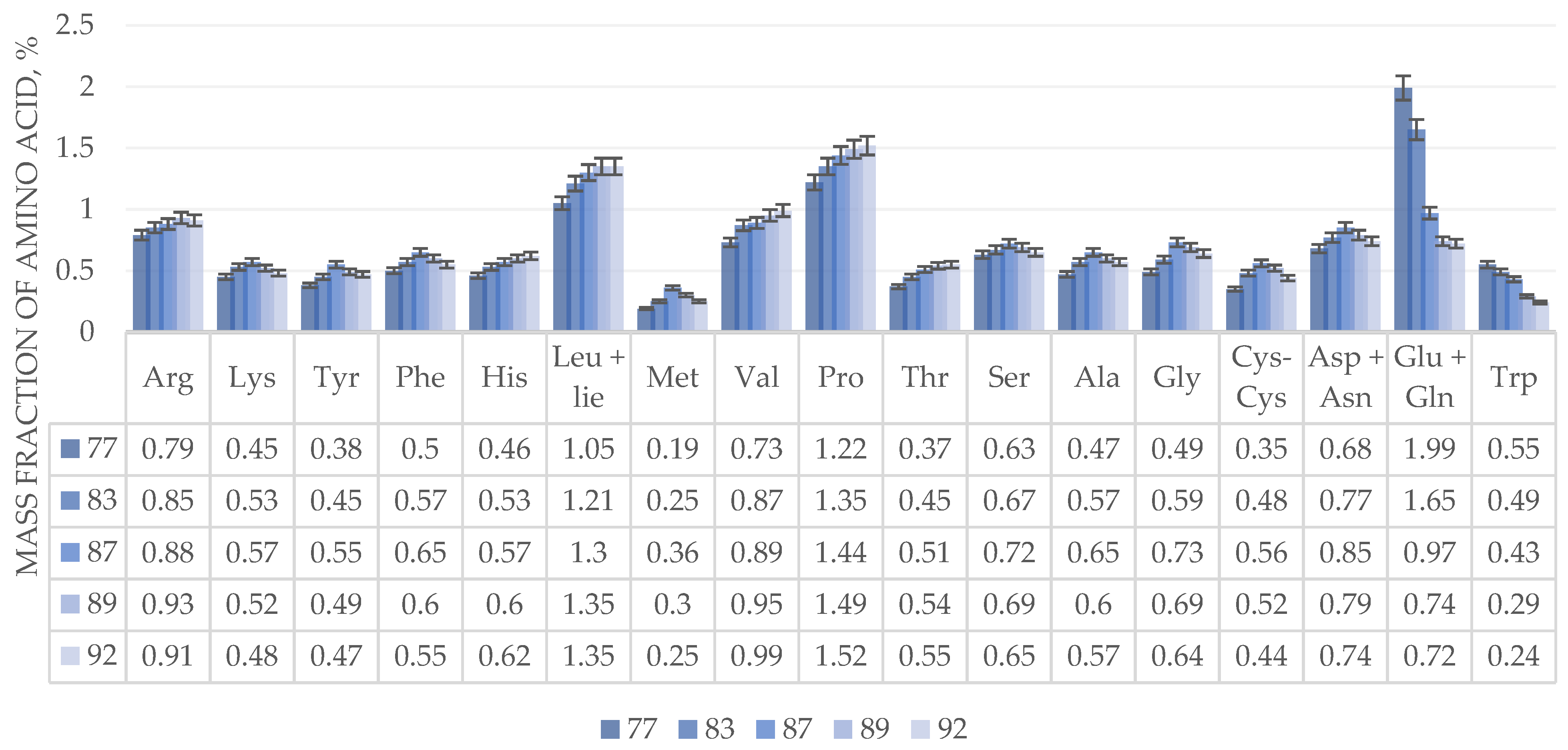

The dynamics of changes in the amino acid composition of the grain heap of perennial winter wheat (trititrigia) of the Pamyati Lyubimovoy variety is similar to the dynamics of annual winter wheat of the Admiral variety. The amino acid composition of perennial wheat is higher than that of annual winter wheat of the Admiral variety by an average of 1.5-2.0 times. In addition, the accumulation of amino acids in perennial wheat occurs more smoothly than in annual wheat.

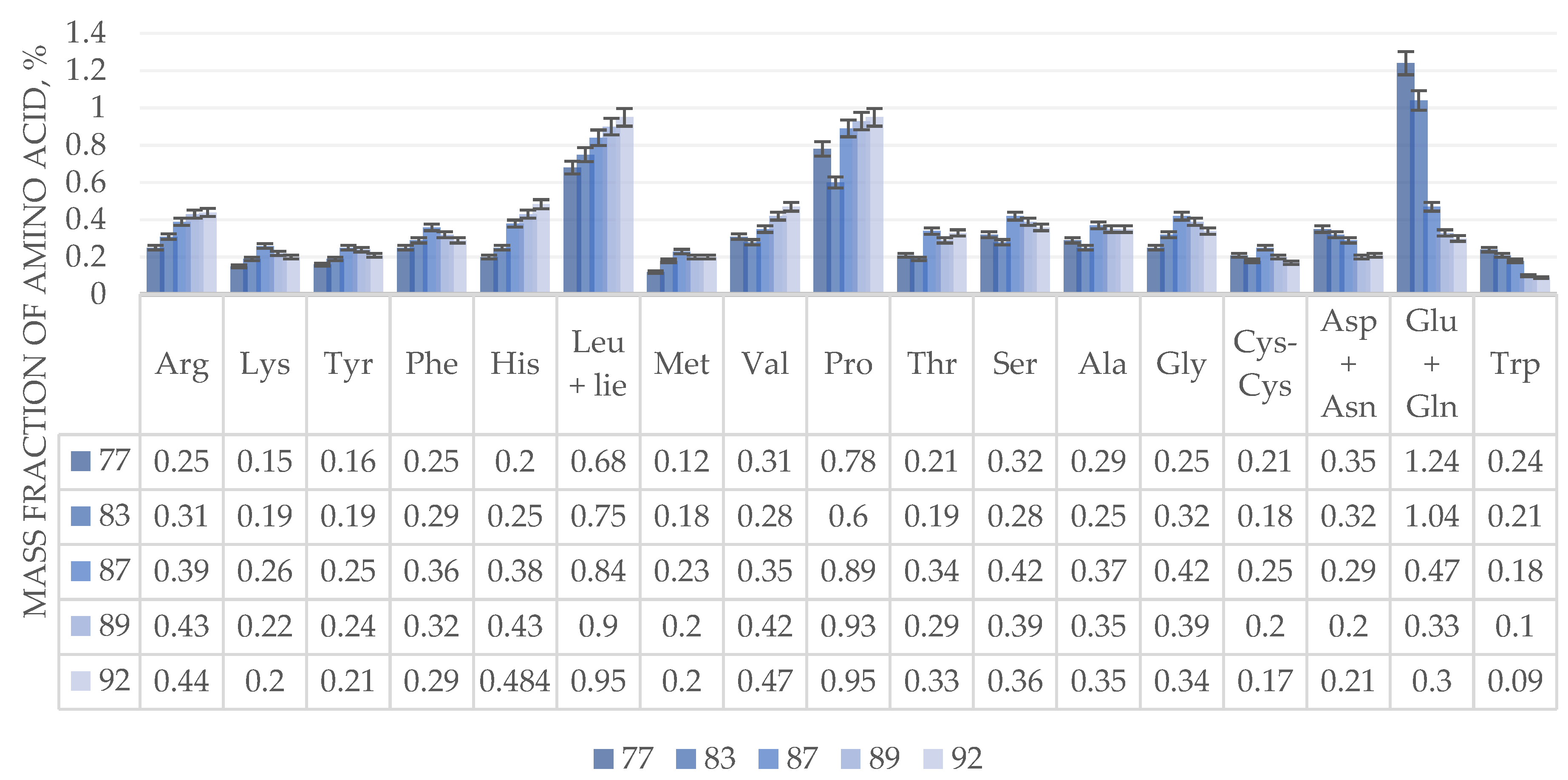

In terms of the content and dynamics of amino acid changes, the Sova variety of blue wheat grass is similar to the Admiral variety of annual winter wheat. The Sova variety of blue wheat grass, in comparison with the previous two analyzed crops, has a lower content of amino acids. It contains a low amount of lysine and tyrosine – more than 2 times. The dynamics of changes in the amino acid composition of the Sova variety of blue wheat grass is similar to the previous crops – the Admiral variety of annual winter wheat and the Pamyati Lyubimovoy variety of trititrigia wheat, with the exception of aspartic acid and asparagine. Its amount reaches peak values at the stage of late milk ripeness and continues to decrease until full ripeness.

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10 present the results of the study of the content of protein, moisture, iron, phosphorus, selenium, zinc, starch and Vitamin E in a heap of cereal crops.

Table 3 shows that all three studied crops have higher peak protein values at the hard wax ripeness stage (stage 87 on the BBCH scale), after which they decrease by 0.1–0.5%. Also, after full ripeness, the protein content in the grain heap decreases by 0.3–0.4%.

The dynamics of moisture change in the heap of cereal crops demonstrates a smooth decrease to the wax ripeness stage and a sharp decrease in moisture before the onset of full ripeness. The grain of winter wheat of the Admiral variety is larger than that of the other two studied crops, as a result of which the grain heap of wheat of the Admiral variety has higher moisture.

The iron content increases smoothly up to the stage of hard wax ripeness. Then, having reached peak values in this phase of 51–53 mg/kg, there is a sharp decrease in the grain heap of annual winter wheat of the Admiral variety and perennial winter wheat (trititrigia) of the Pamyati Lyubimovoy variety. In these crops, the iron content in the phase of full ripeness is lower than in the stage of late milk ripeness. In the grain heap of the Sova variety of blue wheatgrass, iron accumulates up to the onset of full ripeness and only slightly decreases after the onset of full ripeness (stage 92 on the BBCH scale).

The phosphorus content increases slowly throughout all the stages under study. A sharp increase (almost 2 times) occurs after full ripeness and reaches 0.37–0.49%.

Selenium content reaches its peak values at the stage of hard wax ripeness. After full ripeness, selenium content decreases almost by 2 times in two studied samples - grain heap of annual winter wheat of the Admiral variety and grain heap of perennial winter wheat (trititrigia) of the Pamyati Lyubimovoy variety. In grain heap of the Sova variety of wheatgrass, selenium content practically does not change after full ripeness. This is probably due to the presence of a large amount of non-grain part in the grain heap of the Sova variety of wheatgrass, which is typical for this type of crop (Sova variety of wheatgrass has a large amount of green mass in comparison with other grain crops [

15]).

The zinc content at early stages of ripeness (milk and wax 77–87) remains practically unchanged. After full ripeness, the amount decreases slightly by 4–9 mg/kg.

Starch accumulation in grain occurs throughout the growing season and reaches peak values at full maturity. The grain heap of the Sova variety of wheatgrass contains 1.6 times less starch than the other two analyzed samples.

The content of Vitamin E also increases after full ripeness. Vitamin E is fat-soluble and is found mainly in the embryo, so its amount increases sharply after full ripeness – when the embryo is fully formed (increase from 4.71 to 30.22 mg/kg). The change in the quality indicators of grain is similar in all three samples.

3.2. Results of the Study of Prebiotic Activity of Grain Heap of Wheat of Early Stages of Maturity

To study the prebiotic activity, we used a grain heap of Admiral wheat of the hard wax ripeness stage (87 on the BBCH scale), since it is at this stage that the highest content of all the nutrients studied in this work is observed.

3.2.1. Study of the Effect of High Concentrations of Milk Ripeness Wheat in the Chicken Microbiota Model

An artificial intestinal environment of a chicken was used as a model medium. Concentrations of 5%, 2% and 1% were used, since concentrations of 2% were the most effective in our previous studies with essential oil plant cakes. The results are presented in

Table 11.

The presented data show that the waxy wheat grain heap had a significant effect on the chicken microbiota. The number of lactic acid bacteria increased, the pH level of the medium decreased. The number of opportunistic microorganisms decreased, the number of E. coli fell to values below the threshold for this technique. On the other hand, the concentration of bifidobacteria and bacilli also decreased.

In general, an excessively high concentration of waxy wheat grain heap, despite the increase in the number of lactic acid bacteria, has a negative effect on the microbiota, reducing diversity and completely suppressing some groups of microorganisms. Nevertheless, such shifts show the high potential of waxy wheat grain heap as a prebiotic.

3.2.2. Study of Low Concentrations of Milky Ripeness Wheat in the Chicken Microbiota Model

An artificial chicken intestinal environment was used as a model medium. Concentrations of 0.1%, 0.25%, 0.5% were used. The addition of sugar at a concentration of 0.1% was also used as a positive control. It was necessary to determine whether the observed effect was based on the content of prebiotic components or only on the content of simple sugars in the composition of the wheat grain heap. The results obtained are presented in

Table 12.

The presented data show that the microbiota responded weaker to the introduction of waxy wheat grain heap: concentrations of 0.1% and 0.25% did not have a reliable effect on the number and ratio of microorganism groups in the chicken microbiota. A concentration of 0.5% led to an increase in the number of lactobacilli and a decrease in the number of enterococci.

Sugar, even in a deliberately overestimated concentration, did not have a reliable effect on the chicken microbiota, which means that the effect we observed is not associated with the presence of simple sugars in wheat.

3.2.3. Study of Average Concentrations of Milk-Ripe Wheat in the Chicken Microbiota Model

At this stage, the concentrations that seemed the most promising after the first two stages were evaluated - 0.5%, 0.75% and 1%. The results are presented in

Table 13.

The presented data show that the effect of introducing waxy wheat grain heap is weaker than the first experiment and is comparable to the second. All three concentrations caused an increase in the number of lactobacilli. At a concentration of 0.5%, a decrease in the number of E. coli and bacilli is noted, at concentrations of 0.75% and 1% - E. coli, enterococci and bacilli.

3.2.4. Study of Waxy Wheat Grain Heap in the Quail Microbiota Model

To assess the effect of waxy wheat grain heap on the microbiota of other birds, a model of quail cecum microbiota was studied. Milky ripeness wheat was used at a concentration of 0.5%, 0.75% and 1%. The obtained data are presented in

Table 14.

The presented data show that the effect of waxy wheat grain heap on the microbiota of quails is weaker than on the microbiota of chickens. Among the groups representing opportunistic microorganisms, no reliable change in the number was noted when introducing waxy wheat grain heap. No change in the number of bifidobacteria was noted either. At the same time, the number of lactobacilli and other lactic acid bacteria increased significantly, by more than two orders of magnitude, which repeats the trend noted in experiments on the model chicken environment. 3.2.5 Study of dry grain heap of waxy ripeness wheat for the number of microorganisms of different groups under the conditions of the quail microbiota model, CFU/ml

In order to check whether the activity of the grain heap of waxy ripeness wheat changes after drying, wheat in the amount of 1 g, 0.75 g and 0.5 g (which corresponds to 1%, 0.75% and 0.5% concentration) was dried in a dry-heat oven at a temperature of 80 ° C. The moisture content of the wheat was 32%. The results obtained are shown in

Table 15. The concentrations are recalculated for the actual moisture content of the grain heap of waxy ripeness wheat.

As in the previous case, no reliable differences were noted in the number of microorganism groups from the control values, with the exception of the number of lactic acid bacteria, which increased by two orders of magnitude.

3.2.6. Effect of Waxy Wheat Grain Heap on Lactobacilli

Data on the effect of waxy wheat grain heap on the pH of the medium after incubation with

Limosilactobacillus frumenti KL31 are presented in

Table 16.

It can be noted that on the nutrient medium rich in sugars (MRS) a significant decrease in the pH level is observed during the incubation of Limosilactobacillus frumenti KL31. On the artificial intestinal medium containing trace amounts of simple sugars, the pH remains neutral. At the same time, the introduction of both wet and dry grain heap of waxy ripeness wheat leads to an increase in the production of lactic acid by Limosilactobacillus frumenti KL31. This means that the grain heap of waxy ripeness wheat contains carbohydrates that can serve as an energy source for lactobacilli.