1. Introduction

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI), one of the most challenging liver conditions, is characterized by sudden liver inflammation due to exposure to hepatotoxic substances or their metabolites [

1,

2]. Pharmacologically, there are two types of DILI: dose-dependent or intrinsic and dose-independent or idiosyncratic. Dose-dependent injury (in cases of Acetaminophen overdose) can develop when the drug dose exceeds the limit for toxicity, the damage being proportional to the administered dose. Idiosyncratic liver injury is not dose or treatment duration dependent, frequently developing at therapeutic doses [

3].

A wide variety of drugs may cause a spectrum of liver disease, from simple anti-pyretic drugs like Paracetamol to multiple dietary herb supplements.

Acetaminophen is one of the most used analgesics, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory drug. Although it is safe at therapeutic doses, overdoses of Acetaminophen can cause severe liver injury. After ingestion, around 90% of the Acetaminophen is metabolized in nontoxic compounds (sulfate and glucuronide), which are conjugated in the liver and then excreted into the urine. Approximately 5-9% of Acetaminophen is metabolized by cytochrome p450 into a more toxic form (

N-acetyl-

p benzoquinone imine - NAPQI) which can induce oxidative injury and hepatocellular necrosis. Only 2% of acetaminophen is excreted unchanged in the urine [

4,

5,

6].

Herbal drugs and dietary supplements are a major growing concern globally for liver injury [

7]. Whitania Somnifera (or Indian Ginseng), popularly known as Ashwagandha, widely used in Indian Ayurvedic medicine [

8], is an herb used in dietary supplements for relieving stress and anxiety, improving sleep, increasing muscle mass and strength, improving sexual function in both males and females, increasing memory and as “immune booster”. It can induce serious liver injury, acute decompensation of cirrhosis, and acute-on-chronic liver failure. The predominant pattern of liver injury is cholestatic, with or without inflammation and sometimes necrosis, with jaundice and pruritus as clinical presentation [

9].

In multiple sclerosis (MS) there are many therapeutic options, most of the available disease modifying therapies (DMT’s) causing DILI.

DMT’s, used for reducing the frequency of relapses, disability, and accumulation of irreversible damage, interfere with a variety of immunological mechanisms, not being free of potential hepatic toxic effects [

10,

11]. Different mechanisms of liver injury during DMT’s treatment can be autoimmune, with viral reactivation, and in rare cases, with idiosyncratic reactions with unpredictable acute liver failure [

2,

10].

DMT’s can be classified in moderate efficiency treatments (beta interferon, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate) and highly efficiency treatments (natalizumab, fingolimod, alemtuzumab, cladribine, ocrelizumab), every treatment being individualized for every patient due to the risk–benefit profile, with induction and escalation strategies [

12].

Natalizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody anti integrin that blocks leukocyte adhesion to vascular cell adhesion receptor on endothelial cells, thus inhibiting their migration into the central nervous system. Natalizumab was approved for MS treatment for the first time in 2004 and is administered at a dose of 300 mg by intravenous and recently by subcutaneous infusion every 4 weeks [

13].

Several adverse effects of Natalizumab reported are rash, abdominal discomfort, nausea, depression, fatigue, urinary tract infection and lower and upper respiratory tracts infection. One important complication is progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a serious neurological condition associated with John Cunningham virus reactivation in the nervous system [

14].

Hepatotoxicity can appear at any time during treatment, even after the first administration. Natalizumab-induced liver injury has been reported after the first dose, with increases in liver enzymes usually after 6 or more days, or may follow after multiple doses. Liver toxicity at Natalizumab has an idiosyncratic autoimmune-like pattern, with non-severe acute hepatitis (with a hepatocellular involvement) and sometimes with positive autoantibodies, mainly anti-nuclear and anti-smooth muscle antibodies [

15,

16].

Severe cases of both Natalizumab-induced liver injury and autoimmune hepatitis triggered by treatment with Natalizumab have been reported, with cases overlapping these two conditions and characterized by the presence of autoantibodies and a histological pattern of plasma cell infiltration, with no recurrence after steroid withdrawal [

16].

2. Case Presentation

We present the cases of a female patient diagnosed with MS, with natalizumab as immunomodulatory treatment initialized 7 years ago, who suddenly developed acute liver injury.

39 years female patient, diagnosed with MS at the age of 27 years old, with brainstem syndrome as disease onset, with multiple relapses during the evolution, had undergone multiple therapies: 1) Glatiramer Acetate for one year and a half, (2) Interferon-beta for two years, therapies withdrawn due to treatment failure with clinical and imaging activity, and escalation to current immunomodulatory treatment with 3) Natalizumab (infusion no. 81).

The patient had recent history of an airway infection treated with 4-5 capsules of Paracetamol per day for 7 days. She had history of consumption of dietary supplement with Ashwagandha herbs in the last month, with the desire to lose weight.

She presented at emergency room with jaundice, pruritus, and lower limbs ecchymoses. There was no fever, myalgia, diarrhea, or abdominal pain. She denied alcohol in-take and use of illicit drugs.

On physical examination, she was overweight and there was no flapping or features of chronic liver disease. She was medically stable with a blood pressure of 110/60 mmHg, a pulse of 75 beats per minute, a respiration rate of 20 breaths per minute, and a normal temperature.

Abdominal ultra-sound showed a liver with normal morphology, with no cholelithiasis and no signs of cholecystitis, and no dilatation of the biliary tract.

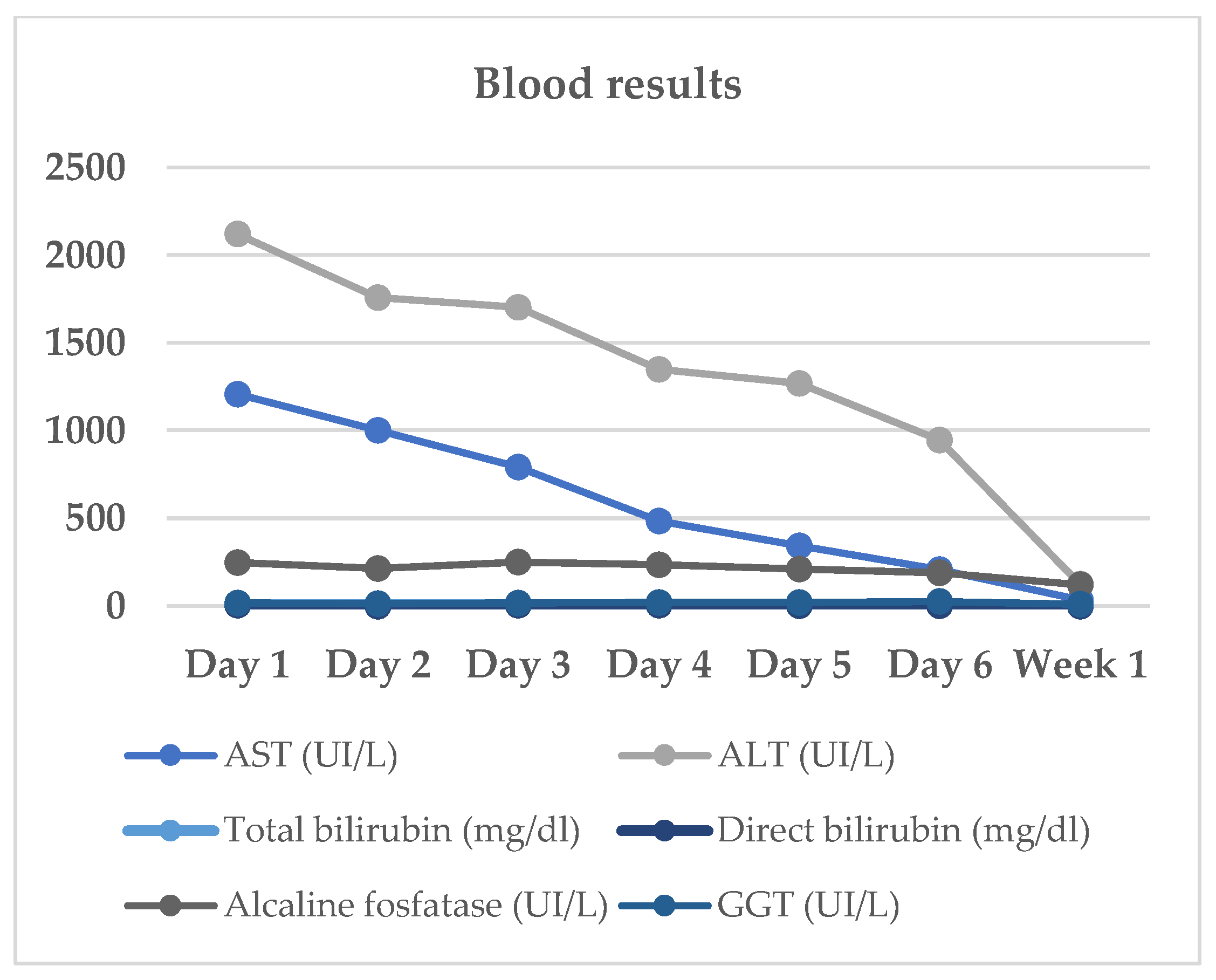

The patient’s complete blood count showed a white blood cell (WBC) of 11.9 10^3/mL (segmented neutrophils 68.5%, lymphocytes 25%, eosinophil 0.3%), hemoglobin of 12.3 g/dL, hematocrit of 31.1%, and platelet count of 368.000/mL. The serum biochemical assay showed the following results: creatinine, 0.46 mg/dL; Na, 139 mEq/L; K, 4.0 mEq/L. Laboratory results revealed aminotransferases levels higher than 1000UI/L (ALT-2120 UI/L, AST-1208 UI/L), higher total bilirubin (7.9 mg/dL) and alkaline phosphatase (247 UI/L).

Table 1

Screening for autoimmune hepatitis was negative, all autoimmune markers were negative: anti-nuclear antibody (Ab), anti-mitochondrial Ab, anti-smooth muscle Ab and anti-liver kidney microsomal Ab.

Table 2

Screening for infectious hepatitis was negative. The anti-Hepatitis A Virus Antibodies, Hepatitis B surface Antigen, anti-Hepatitis B e-Antibodies and Antigen, anti-Hepatitis C Virus Antibodies, anti-Hepatitis E Virus Antibodies, tests results were all negative. There was no serologic evidence of recent infection with Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr Virus, or Herpes Simplex Virus.

Table 3

The scenario of a toxic hepatitis induced by recently used drugs (Paracetamol and Ashwagandha dietary supplement) led the medical team to start oral prednisone 40 mg/day.

She was then discharged from the hospital for outpatient follow-up. The dosage of corticosteroid has been progressively reduced in the outpatient follow-up.

She progressively improved in clinical and laboratory test results

Table 1/

Figure 1, with normalization of the serum levels of liver enzymes and bilirubin 1 month after stating the oral prednisone. There was no further increase of liver enzymes after discontinuation of corticosteroid therapy and dietary supplement.

Far from the normalization of the liver enzymes and from stopping consumption of herb supplements, the patient resumed the immunomodulatory treatment with Natalizumab, without changes in hepatic function.

4. Discussion

We report the case of a female patient diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, with Natalizumab as current immunomodulatory treatment (infusion no. 81), with Ashwagandha-related drug induced liver injury, precipitated by using the anti-pyretic drug Paracetamol. The predominant pattern of liver injury was cholestatic, with jaundice as the notable clinical presentation. There was a long and detailed diagnostic evaluation to rule out other causes for the acute liver injury. The Ashwagandha-induced liver injury was self-limiting with treatment and supportive care.

Natalizumab-induced liver injury is rare and may occur any time during treatment, especially after the first or second dose infusions. It is usually non-severe acute hepatitis and resolves spontaneously [

16,

17].

According to the phase III trials (AFFIRM, SENTINEL, ASCEND), abnormal liver function tests on patient with Natalizumab as immunomodulatory treatment, were reported in 5% of patients and were graded as severe in less than 1% of patients [

17,

18,

19]. Safety data are available for up to 2 years of treatment in these trials, however, in extension studies up to 10 years, a rate of serious hepatobiliary adverse events was confirmed in less than 1% of patients [

18,

19,

20].

Since 2009, there were reported over 30 cases of severe liver injury induced by Natalizumab, listed in the adverse event reporting system. The authors estimated the frequency of liver injury from Natalizumab to be 17 per 100,000 exposed patients. [

16,

21] Hepatotoxicity can arise at any time during treatment, especially after the first administration.

Ashwagandha is beneficial for many conditions, including exercise capacity and physical performance, sleep, reducing stress and anxiety.

Although generally it is considered safe to consume, there is a high report of drug induced liver injury due to Ashwagandha use, the mechanism of damage being the presence of herb-specific compounds called withanolides that can cause irreversible damage of hepatocellular DNA [

22,

23].

The reports of Ashwagandha-induced liver injury have been published in medical literature since 2011. The first case reports were from Japan, followed by multiple reports from United States, India, Germany, and Poland. There were largest cohorts of Ashwagandha-related liver injuries, although cases of liver injury due to Ashwagandha could be more.

Most herbal drugs contain multi-ingredient compounds and is difficult to demonstrate the exact compound that is responsible for liver injury. In most of the cohorts, patients used only Ashwagandha supplements, establishing with certainty and concern that Ashwagandha can cause severe liver injury and death among most of the patients [

22,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].In the case of our patient, she used only Ashwagandha supplement.

Chronic liver disease patients develop more severe drug induced liver injury, showing in these cases a poor prognosis. In some reports, drug induced liver injury in patients with underlying liver disease has been associated with high mortality rates, up to 16%, compared to almost 5% in patients without pre-existing liver disease [

22,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

In our patient history there was no chronic liver disease, or no use of alcohol. The patient had concomitant hepatotoxic medicine use, the antipyretic drug Paracetamol.

In all cohorts of Ashwagandha reports there were a whole viral hepatitis screening, which was considered very unlikely to cause the pattern of liver injury described, which was predominantly cholestatic with only moderate elevation in hepatic enzymes aminotransferases [

22,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].The autoimmune hepatitis screening, revealed in one cohort that there were cases with positive autoantibodies with high serum IgG without other classical features of autoimmune hepatitis [

22]. Mild elevations of autoimmune markers are very commonly described in patients with drug induced liver injury, especially in the context of herb induced liver damage [

22].

Severe cases of both Natalizumab-induced liver injury and autoimmune hepatitis triggered by Natalizumab have been reported in literature, with many cases overlapping these two conditions and characterized by the presence of autoantibodies, but without recurrence after steroid withdrawal [

16]. In our case, there was a long and detailed diagnostic evaluation to rule out other causes for the acute liver injury, the screening for viral and autoimmune hepatitis being negative, with no positive autoantibodies.

In all the cohorts, the Ashwagandha use indication was for stress and anxiety, in young or middle-aged people, with clinical presentation of jaundice and cholestasis. Most patients consumed the herb as per label instructions or as the indication prescribed [

22,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. In our case, the patient used Ashwagandha supplement as part of her diet programme, the clinical presentation being with jaundice, pruritus, and lower limbs ecchymoses. The withdrawal of supplement and treatment with immunosuppression cortisone resolved the jaundice and the hepatitis.

5. Conclusions

The case report highlights the difficulty to establish the multiple etiologies and the management of an acute hepatitis in a MS patient with Natalizumab as immunomodulatory treatment, a drug that can induce liver injury but after the first infusions, and recent history of ingestion of toxic hepatic drugs.

The diagnosis of drug induced liver injury can be considered one of the most challenging diagnoses. A wide variety of drugs can cause a spectrum of liver disease. Diseased modified therapies approved for multiple sclerosis treatment, can have potential hepatic toxic effects, but mostly after the first infusions. Simple anti-pyretic drugs like paracetamol or multiple dietary herb supplements can induce liver injury. Ashwagandha herb, extensively used in the Indian systems of traditional medicine, is a dietary supplement and a potential liver-damaging factor.

In view of many documented cases of liver damage caused by Ashwagandha or other drugs, with unknown metabolic mechanisms of substances contained in it, there should be a great attention to patients reporting the use of different drugs and herbs and presenting with symptoms of liver damage.

There should be a high public education on avoiding unrecommended and potentially harmful drugs and herbal supplements, with the purpose to reduce the number of cases of drug liver injury.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-M.D.-M. and S.P.; methodology, M.-M.D.-M., S.P. and C.A.P.; software, M.-M.D.-M.; validation, S.P. and C.A.P.; formal analysis, M.-M.D.-M. and S.P.; investigation, M.-M.D.-M., S.P. and C.A.P.; resources, M.-M.D.-M., S.P. and C.A.P.; data curation, M.-M.D.-M. and S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.-M.D.-M. and S.P.; writing—review and editing, M.-M.D.-M.; visualization, M.-M.D.-M.; supervision, S.P. and C.A.P.; project administration, C.A.P. We, the authors, are the only persons responsible for the content of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. It did not require permission from an ethical committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dijmărescu I, Guță OM, Brezeanu LE, Dijmărescu AD, Becheanu CA, Păcurar D. Drug-Induced Hepatitis in Children: The Experience of a Single Center in Romania. Children 2022; 9: 1136. [CrossRef]

- Andrade RJ, Aithal GP, Björnsson ES et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Drug-induced liver injury. J Hepatol 2019; 70: 1222–1261. [CrossRef]

- David S, Hamilton JP, Hopkins J. Drug-induced Liver Injury. 2010;

- Hou Y-C, Lin J-L, Huang W-H et al. Outcomes of patients with acetaminophen-associated toxic hepatitis at a far east poison center. 2013; [CrossRef]

- Jollow DJ, Mitchell JR, Potter WZ, Davis DC, Gillette JR, Brodie BB. ACETAMINOPHEN-INDUCED HEPATIC NECROSIS. II. ROLE OF COVALENT BINDING IN VIVO. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 1973; 187.

- Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of acetaminophen (paracetamol) poisoning in children and adolescents - UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-acetaminophen-paracetamol-poisoning-in-children-and-adolescents (3 August 2024, date last accessed).

- Shen T, Liu Y, Shang J et al. Incidence and Etiology of Drug-Induced Liver Injury in Mainland China. Gastroenterology 2019; 156: 2230-2241.e11. [CrossRef]

- Philips CA, Paramaguru R, Joy AK, Antony KL, Augustine P. Clinical outcomes, histopathological patterns, and chemical analysis of Ayurveda and herbal medicine associated with severe liver injury-A single-center experience from southern India. Indian J Gastroenterol 2018; 37: 9–17.

- Paul S, Chakraborty S, Anand U et al. Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (Ashwagandha): A comprehensive review on ethnopharmacology, pharmacotherapeutics, biomedicinal and toxicological aspects. Biomed Pharmacother 2021; 143. [CrossRef]

- Biolato M, Bianco A, Lucchini M, Gasbarrini A, Mirabella M, Grieco A. The Disease-Modifying Therapies of Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis and Liver Injury: A Narrative Review. CNS Drugs 2021; 35: 861–880. [CrossRef]

- Comi G, Radaelli M, Soelberg Sørensen P. Evolving concepts in the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2017; 389: 1347–1356. [CrossRef]

- Filippi M, Amato MP, Centonze D et al. Early use of high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies makes the difference in people with multiple sclerosis: an expert opinion. J Neurol 2022; 269: 5382.

- Ransohoff RM. Natalizumab for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 2622–2629.

- Niino M, Bodner C, Simard ML et al. Natalizumab effects on immune cell responses in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2006; 59: 748–754. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lapiscina EH, Lacruz F, Bolado-Concejo F et al. Natalizumab-induced autoimmune hepatitis in a patient with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2013; 19: 1234–1235. [CrossRef]

- Biolato M, Bianco A, Lucchini M, Gasbarrini A, Mirabella M, Grieco A. The Disease-Modifying Therapies of Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis and Liver Injury: A Narrative Review. CNS Drugs 2021; 35: 861–880. [CrossRef]

- Bezabeh S, Flowers CM, Kortepeter C, Avigan M. Clinically significant liver injury in patients treated with natalizumab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31: 1028–1035. [CrossRef]

- Polman CH, O’Connor PW, Havrdova E et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 899–910. [CrossRef]

- Rudick RA, Stuart WH, Calabresi PA et al. Natalizumab plus Interferon Beta-1a for Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. 2006; [CrossRef]

- Kapoor R, Ho PR, Campbell N et al. Effect of natalizumab on disease progression in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (ASCEND): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with an open-label extension. Lancet Neurol 2018; 17: 405–415. [CrossRef]

- Antezana A, Sigal S, Herbert J, Kister I. Natalizumab-induced hepatic injury: A case report and review of literature. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2015; 4: 495–498. [CrossRef]

- Philips CA, Valsan A, Theruvath AH et al. Ashwagandha-induced liver injury-A case series from India and literature review. Hepatol Commun 2023; 7. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui S, Ahmed N, Goswami M, Chakrabarty A, Chowdhury G. DNA damage by Withanone as a potential cause of liver toxicity observed for herbal products of Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha). Curr Res Toxicol 2021; 2: 72–81. [CrossRef]

- Lubarska M, Hałasiński P, Hryhorowicz S et al. Liver Dangers of Herbal Products: A Case Report of Ashwagandha-Induced Liver Injury. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20. [CrossRef]

- Björnsson HK, Björnsson ES, Avula B et al. Liver Injury due to Ashwagandha. A Case Series from Iceland and the U.S. Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Liver Int 2020; 40: 825. [CrossRef]

- Weber S, Gerbes AL. Ashwagandha-Induced Liver Injury: Self-Reports on Commercial Websites as Useful Adjunct Tools for Causality Assessment. Am J Gastroenterol 2021; 116: 2151–2152. [CrossRef]

- Ireland PJ, Hardy T, Burt AD, Donnelly MC. Drug-induced hepatocellular injury due to herbal supplement ashwagandha. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2021; 51: 363–365. [CrossRef]

- Rattu M, Maddock E, Espinosa J, Lucerna A, Bhatnagar N. An Herbal Liver Effect: Ashwagandha-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Rowan-Virtua Research Day 2022;

- Ali SMJ, Suresh MG, Sanchez-Cruz J, Anand C. S2976 Cry Me a Liver: Ashwagandha-Induced Liver Toxicity. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2022; 117: e1931–e1931.

- Tóth M, Benedek AE, Longerich T, Seitz H. Ashwagandha-induced acute liver injury: A case report. Clin Case Rep 2023; 11.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).