Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Type of Study

Study Population

Data Collection

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Lifestyle Risk Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Endorses Landmark Public Health Decisions on Essential Medicines for Multiple Sclerosis Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/26-07-2023-who-endorses-landmark-public-health-decisions-on-essential-medicines-for-multiple-sclerosis.

- Dobson, R.; Giovannoni, G. Multiple Sclerosis - a Review. Eur J Neurol 2019, 26, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, N.; Smith, T.W. An Update on Immunopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Behav 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintore, M.; Otero-Romero, S.; Río, J.; Arrambide, G.; Pujal, B.; Tur, C.; Galán, I.; Comabella, M.; Nos, C.; Arévalo, M.J.; et al. Contribution of the Symptomatic Lesion in Establishing MS Diagnosis and Prognosis. Neurology 2016, 87, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis: 2017 Revisions of the McDonald Criteria. Lancet Neurol 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinley, M.P.; Cohen, J.A. Evolution of the Diagnostic Criteria in Multiple Sclerosis. In Neuroimmunology; Piquet, A.L., Alvarez, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 75–87. ISBN 978-3-030-61882-7. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is the Socioeconomic Burden of Cardiovascular Disease? Available online: https://www.wifor.com/en/socioeconomic-burden-of-cardiovascular-disease/ (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- HISTORY OF INTERFERON TREATMENTS IN MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS – 60 YEARS OF PROGRESS – Farmacia Journal. Available online: https://farmaciajournal.com/issue-articles/history-of-interferon-treatments-in-multiple-sclerosis-60-years-of-progress/ (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Cree, B.A.C.; Oksenberg, J.R.; Hauser, S.L. Multiple Sclerosis: Two Decades of Progress. Lancet Neurol 2022, 21, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.R.; Askari, M.; Azadani, N.N.; Ataei, A.; Ghadimi, K.; Tavoosi, N.; Falahatian, M. Mechanism and Adverse Effects of Multiple Sclerosis Drugs: A Review Article. Part 1. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 2019, 11, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Plesa, C.F.; Chitimus, D.M.; Sirbu, C.A.; Țânțu, M.M.; Ghinescu, M.C.; Anghel, D.; Ionita-Radu, F. Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura in Interferon Beta-1a-Treated Patient Diagnosed with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Case Report. Life 2022, Vol. 12, Page 80 2022, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalkh, G.; Abi Nahed, R.; Macaron, G.; Rensel, M. Safety of Newer Disease Modifying Therapies in Multiple Sclerosis. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 9, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palladino, R.; Marrie, R.A.; Majeed, A.; Chataway, J. Evaluating the Risk of Macrovascular Events and Mortality Among People With Multiple Sclerosis in England. JAMA Neurol 2020, 77, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrie, R.A.; Reider, N.; Cohen, J.; Stuve, O.; Trojano, M.; Cutter, G.; Reingold, S.; Sorensen, P.S. A Systematic Review of the Incidence and Prevalence of Cardiac, Cerebrovascular, and Peripheral Vascular Disease in Multiple Sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2015, 21, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhas-Hamiel, O.; Livne, M.; Harari, G.; Achiron, A. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome Components in Multiple Sclerosis Patients with Significant Disability. Eur J Neurol 2015, 22, 1275–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrie, R.A.; Horwitz, R.I. Emerging Effects of Comorbidities on Multiple Sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2010, 9, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maric, G.; Pekmezovic, T.; Tamas, O.; Veselinovic, N.; Jovanovic, A.; Lalic, K.; Mesaros, S.; Drulovic, J. Impact of Comorbidities on the Disability Progression in Multiple Sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2022, 145, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magyari, M.; Sorensen, P.S. Comorbidity in Multiple Sclerosis. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.; Rudick, R.A.; Hara-Cleaver, C.; Marrie, R.A. Validation of a Self-Report Comorbidity Questionnaire for Multiple Sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology 2010, 35, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadidi, E.; Mohammadi, M.; Moradi, T. High Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases after Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2013, 19, 1336–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Hu, T.; He, K.; Ying, J.; Cui, H. Multiple Sclerosis and the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, D.; Michels, S.; Schöpe, J.; Schwingshackl, L.; Tumani, H.; Senel, M. Associations between Multiple Sclerosis and Incidence of Heart Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, L. da S.; Damasceno, N.R.T.; Maia, F.N.; Carvalho, B.M. de; Maia, C.S.C.; D’Almeida, J.A.C.; Melo, M.L.P. de Cardiovascular Risk Estimated in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis: A Case-Control Study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakimovski, D.; Topolski, M.; Genovese, A.V.; Weinstock - Guttman, B.; Zivadinov, R. Vascular Aspects of Multiple Sclerosis: Emphasis on Perfusion and Cardiovascular Comorbidities. Expert Rev Neurother 2019, 19, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diebold, M.; Derfuss, T. Immunological Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis. Semin Hematol 2016, 53, S54–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csenteri, O.; Jancsó, Z.; Szöllösi, G.J.; Andréka, P.; Vajer, P. Differences of Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Clinical Practice Using SCORE and SCORE2. Open Heart 2022, 9, e002087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyari, M. Gender Differences in Multiple Sclerosis Epidemiology and Treatment Response. Dan Med J 2016, 63, B5212. [Google Scholar]

- Keytsman, C.; Eijnde, B.O.; Hansen, D.; Verboven, K.; Wens, I. Elevated Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Multiple Sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2017, 17, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorobantu, M.; Tautu, O.-F.; Dimulescu, D.; Sinescu, C.; Gusbeth-Tatomir, P.; Arsenescu-Georgescu, C.; Mitu, F.; Lighezan, D.; Pop, C.; Babes, K.; et al. Perspectives on Hypertension’s Prevalence, Treatment and Control in a High Cardiovascular Risk East European Country. J Hypertens 2018, 36, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hâncu, A.; Roman, G.; Bala, C.; Timar, B.; Roman, D.; Păun, D.; Mechanick, J.I. Diabetes Care in Romania: A Lesson on the Central Role of Lifestyle Medicine. Am J Lifestyle Med 2023, 15598276231195572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, C.M.; Mullen, K.-A.; Foulds, H.J.A.; Jaffer, S.; Nerenberg, K.; Gulati, M.; Parast, N.; Tegg, N.; Gonsalves, C.A.; Grewal, J.; et al. CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEART HEALTH ALLIANCE ATLAS: EPIDEMIOLOGY, DIAGNOSIS, AND MANAGEMENT OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE IN WOMEN Chapter 7: Sex, Gender, and the Social Determinants of Health. CJC Open 2023, S2589790X23002111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics | Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/hlth_ehis_sk1c/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=440194bd-fc13-44d8-9c4c-bec758227f5e (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Karimi, S.; Andayeshgar, B.; Khatony, A. Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Stress in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis in Kermanshah-Iran: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics | Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ilc_pw01/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Aune, D.; Sen, A.; Prasad, M.; Norat, T.; Janszky, I.; Tonstad, S.; Romundstad, P.; Vatten, L.J. BMI and All Cause Mortality: Systematic Review and Non-Linear Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of 230 Cohort Studies with 3.74 Million Deaths among 30.3 Million Participants. BMJ 2016, i2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardiotis, E.; Tsouris, Z.; Aslanidou, P.; Aloizou, A.-M.; Sokratous, M.; Provatas, A.; Siokas, V.; Deretzi, G.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.M. Body Mass Index in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Neurol Res 2019, 41, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbartabar Toori, M.; Kiani, F.; Sayehmiri, F.; Sayehmiri, K.; Mohsenzadeh, Y.; Ostovar, R.; Angha, P.; Mohsenzadeh, Y. Prevalence of Hypercholesterolemia, High LDL, and Low HDL in Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Iran J Med Sci 2018, 43, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koca, N.; Seferoğlu, M. Effects of Disease-Modifying Therapies on Lipid Parameters in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2023, 77, 104876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazeri, M.; Bazrafshan, H.; Abolhasani Foroughi, A. Serum Inflammatory Markers in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis and Their Association with Clinical Manifestations and MRI Findings. Acta Neurol Belg 2022, 122, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzo, M.; Reia, A.; Maniscalco, G.T.; Luiso, F.; Lanzillo, R.; Russo, C.V.; Carotenuto, A.; Allegorico, L.; Palladino, R.; Brescia Morra, V.; et al. The Framingham Cardiovascular Risk Score and 5-year Progression of Multiple Sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2021, 28, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion criteria |

| Patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis |

| Patients under treatment through the National Health Program for MS between September 2022 and September 2023 |

| Patients whose paraclinical investigations are in the hospital record |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Patients who had serious concomitant diseases (cancer, hepatitis, etc.) or treatments (e.g., chemotherapy) that could interfere with cardiovascular risk (3) |

| Patients who refused to answer the questionnaire (2) |

| Women aged ≥ 60 years and men aged ≥ 55 years* (11) |

| Patients with Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) (1) |

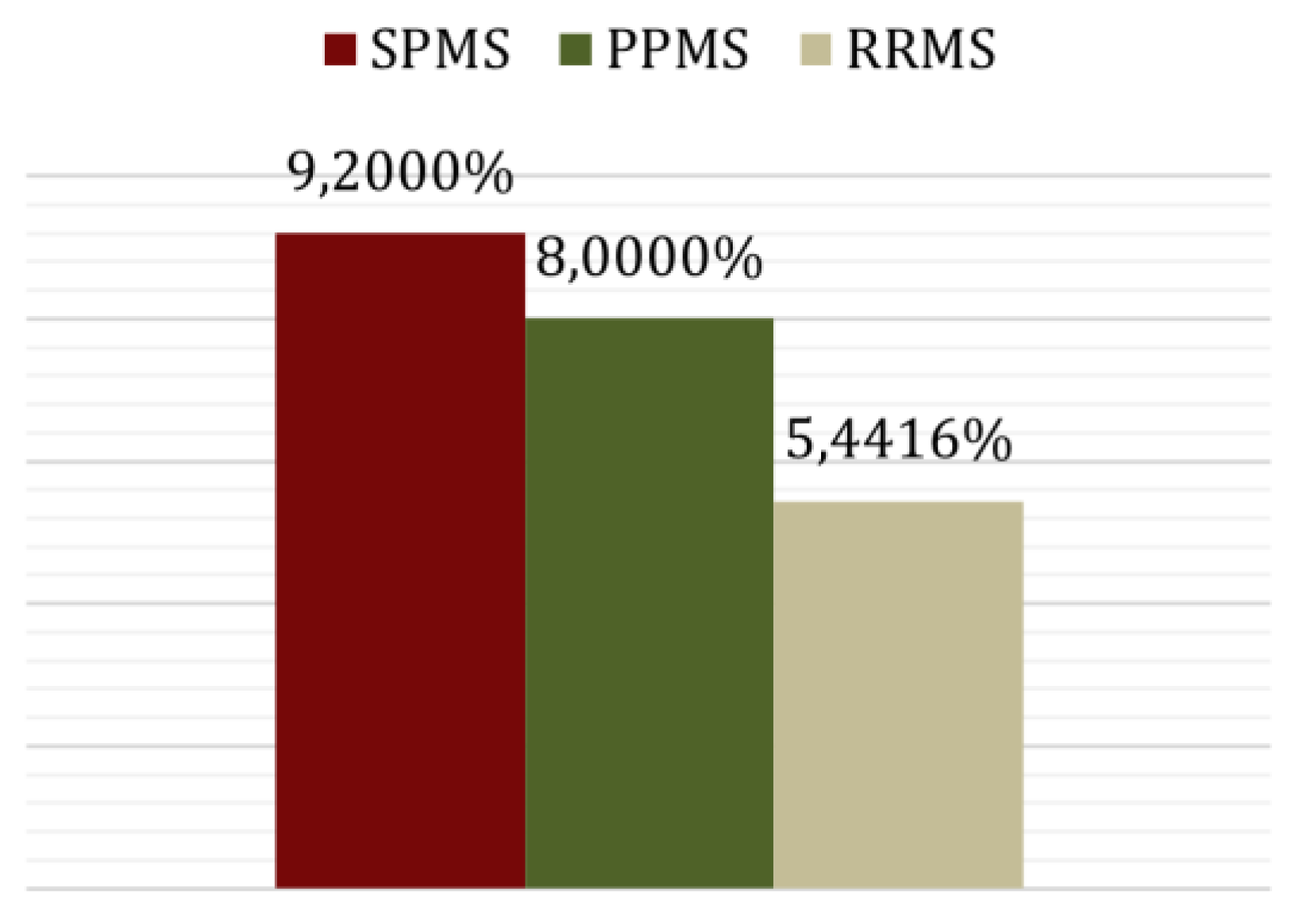

| MS-type | Number (percentage) of patients | Average years of disease progression |

|---|---|---|

| Relapsing-remitting MS | 77 (84.62%) | 8.72 |

| Secondary-progressive MS | 10 (10.99%) | 13.44 |

| Primary-progressive MS | 4 (4.40%) | 4.08 |

| Level of Physical Activity | Average Age (years) | Average EDSS Score | Average BMI (kg/m²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary (minimal activity, mostly sitting/watching TV) | 45.23 | 4.9545 | 21.5350 |

| Light Activity (slow walking, household chores) | 46.22 | 2.6300 | 24.9327 |

| Moderate Activity (walking more than 30 minutes daily, cycling, dancing) | 37.75 | 1.5625 | 23.1498 |

| Intense Activity (regular sports: jogging, cycling, yoga, etc.) | 33.89 | 1.5000 | 22.6430 |

| Blood Test | Mean | Standard deviation | Biological reference intervals |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Glycemia (mg/dl) |

97,5948 | 36,5822 | 74,00 - 100,00 |

|

Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) |

198,4817 | 38,5618 | <200 - normal 200 - 239 – moderate risk >240 – high risk |

|

LDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) |

120,8003 | 36,6784 | <100 -normal 100 - 129 – low risk 130 - 159 – moderate risk >160 – high risk |

|

HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) |

56,6636 | 14,9341 | 10 - 40 (male)/ 50 (female) high risk 41/51 - 90 normal |

|

ESR (Erythrocytesedimentation rate) (mm/1h) |

13,4407 | 10,9580 | 0,00 - 20,00 |

|

Creatinine (mg/dl) |

0,7369 | 0,1711 | 0,51-0,95 |

|

Urea (mg/dl) |

29,3637 | 8,5922 | 17,00-43,00 |

| Mean SCORE (%) | ||

| Cholesterol <200 mg/dl | Cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dl | |

| Triglycerides <150 mg/dl | 5,4523 | 5,62068 |

| Triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl | 4,1111 | 10,3636 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).