Introduction

Endodontics, a specialized branch of dentistry, focuses on diagnosing and treating dental pulp and periradicular tissues. Over the decades, it has evolved from basic techniques to becoming a cornerstone of modern dental care. This review traces its historical development, highlights technological advancements, and explores its integration into contemporary practices, emphasizing its growing importance in patient-centered care.

Adapting to the challenges of the present is a recurring theme in the narrative of endodontics, emphasizing the imperative for continuous progress in addressing the ever-evolving landscape of dental care. Technological integration is at the forefront of this evolution, reshaping endodontic practices with advanced imaging techniques like Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) and precision-enhancing instrumentation methods, such as Rotary and Reciprocating Systems. The emergence of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) has been transformative for diagnostics, particularly since the 1990s. Recent advancements, such as shortened imaging times and diminished radiation exposure, have positioned CBCT as an instrumental asset in contemporary endodontics. Empirical evidence underscores its supremacy in diagnosing periapical lesions, thereby augmenting diagnostic precision. According to endorsement by dental associations, CBCT emerges as invaluable, particularly in the identification of vertical root fractures (VRFs).

Nevertheless, the universal suitability of CBCT for crack assessments manifests variations, underscoring the necessity for a nuanced comprehension [

1,

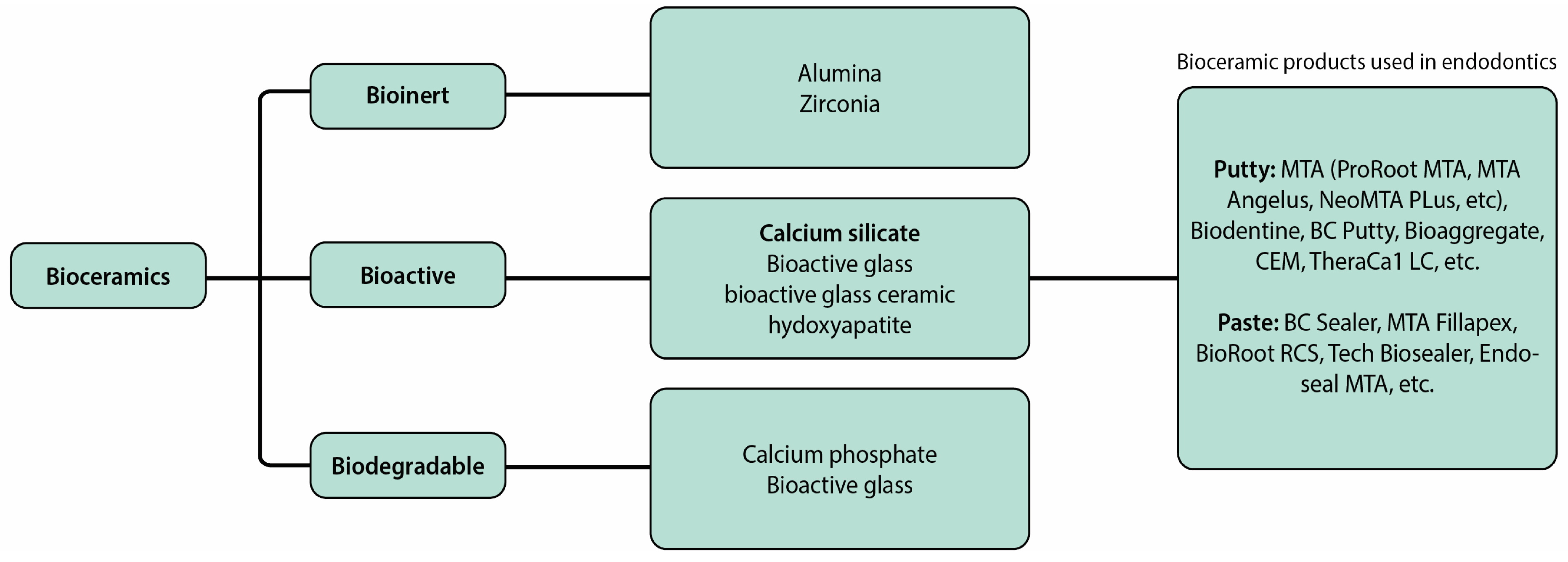

2]. The contemporary paradigm also witnesses a shift towards bioactive materials and regenerative therapies in endodontics. Bioceramic sealers, stem cell therapies, and the utilization of nanotechnology underscore the field’s commitment to biologically driven approaches, revolutionizing traditional treatment modalities. Bioceramic sealers, including calcium silicate-based cements (CSCs) like mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA), have become pivotal for their exceptional properties and biocompatibility. Despite limitations, MTA remains A popular root-end filler material. Concurrently, the integration of nanotechnology in endodontics, featuring nanofibers, liposomes, micelles, and nanoparticles, presents significant advancements in drug delivery systems and addressing microbial biofilms [

3,

4].

Additionally, the intricate neurovascular considerations in endodontics underscore the need for a nuanced approach. Nerve mapping, advancements in local anesthesia techniques, and a focus on vascular supply considerations highlight the complexity of endodontic procedures and the necessity for a meticulous understanding of neurovascular structures. Non-surgical endodontic treatment begins with crucial access cavity preparation for accurate root canal cleaning. Errors at this stage can complicate treatment outcomes. To address complexities like calcified canals, 3D printed guides inspired by guided implant surgery principles precisely locate root canals, minimizing procedural risks. Endodontic procedures near the inferior alveolar nerve pose a risk of neurologic deficits, emphasizing the need for clinician awareness and precision to ensure safe and successful interventions [

5].

As we embark on this exploration, the subsequent sections of this research review will delve into specific topics, offering a detailed analysis of technological advances in endodontic imaging and instrumentation, bioactive materials and regenerative therapies, and neurovascular considerations. Each facet contributes to the intricate tapestry of endodontics, reflecting its historical journey, addressing current challenges, and hinting at the promising horizons that lie ahead.

Technological Advances in Endodontic Imaging and Instrumentation

Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) and Its Impact on Diagnostics

In dentistry, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) is the foremost three-dimensional (3D) imaging technique. CBCT has gained significant prominence Since the 1990s, particularly in medical imaging applications like angiography. Dental diagnosis and treatment planning have been completely transformed since its introduction to the field.

Recent technical developments have allowed CBCT scanners to capture pictures in a significantly shorter amount of time than previous models, create images with greater quality, lower radiation exposure to patients, and have smaller footprints than previous models [

6,

7]. As a result, its application in endodontics is expanding quickly. Numerous studies have been conducted to compare CBCT with conventional radiographic techniques and evaluate its effectiveness in detecting endodontic pathologies.

A research investigation contrasting digital periapical radiography (PAR) with CBCT imaging to diagnose artificial periapical lesions revealed that CBCT imaging displayed greater precision in detecting simulated lesions of different sizes and positions. Additionally, the study indicated that when evaluating teeth without periapical radiolucency, there was no noticeable distinction between CBCT imaging and PAR.

CBCT imaging has been proven to significantly affect decision-making processes in therapeutic endodontics. In recognition of its importance, the American Association of Endodontics (AAE) and the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology (AAOMR) have jointly issued a statement recommending the use of CBCT imaging in various endodontic situations. This statement is based on a thorough review of existing literature and provides evidence-based guidelines.

One specific recommendation highlighted in the statement is the utilization of CBCT scanning for the identification of potential vertical root fractures (VRFs). In a study involving 40 teeth displaying clinical indications of VRFs, traditional radiography (PAR) failed to detect any fracture lines. Consequently, CBCT scans were employed, proving to be 88% accurate in identifying VRFs. However, another study aimed at assessing the extent of tooth cracks using both PAR and CBCT imaging in a controlled laboratory environment revealed that neither method accurately quantified the extent of cracks. This suggests that while CBCT imaging can be highly valuable for specific diagnostic purposes, it may not be universally suitable for all types of crack assessment [

8,

9].

CBCT scanners come in various models with different technical specifications. The scanning process involves image acquisition and reconstruction. CBCT scans use X-ray rotation, and The quantity of acquired projections and the duration of the scan may differ. Four scanning parameters (mAs, kV, FOV, and voxel size) affect image quality and radiation dose. Tube current determines X-ray flux and exposure time impacts dose. Higher mA reduces image noise. Tube voltage affects X-ray beam energy, penetration, dose, and image quality [

10,

11].

CBCT technology has advanced significantly, offering shorter imaging times, reduced radiation exposure, and improved image quality. These improvements enhance diagnostic precision, particularly in identifying periapical lesions, calcified canals, and vertical root fractures. Such advancements make CBCT an indispensable tool for complex endodontic cases

For all endodontic procedures, it is increasingly the preferred imaging method. CBCT’s 3D imaging capabilities enhance treatment efficiency by aiding in the diagnosis of calcified canals and evaluating failures in prior treatments. Its ability to provide detailed insights ensures better clinical decision-making for complex cases. Endodontists, for the most part, only handle complex cases [

12,

13].

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

While CBCT has transformed 3D imaging in endodontics, Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) offers a complementary approach with its noninvasive, non-radioactive capabilities. Initially developed for ophthalmology, OCT has expanded its applications to dentistry, where it aids in detecting enamel cracks, root fractures, and internal structures with high precision. Additionally, it has been adapted for diagnosing coronary atherosclerosis by utilizing a modified catheter as an optical fiber. Over time, the application of OCT has expanded to include various fields such as dermatology, neurology, and dentistry.

Within dentistry, the OCT system proves adept at diagnosing a range of caries, including occlusal, proximal, and cervical caries. Its utility extends to the comparison of various adhesive materials concerning gap formations beneath composite restorations. Moreover, OCT is instrumental in identifying enamel cracks, vertical root fractures, and cracks within dental composite materials. OCT’s primary benefit in dentistry is its capacity to non-invasively and accurately detect and characterize small defects in dental tissues, materials, and structures. This includes identifying additional canals, isthmuses, recesses, or intra-radicular connections (

Figure 1) [

14,

15,

16].

OCT fundamentally depends on low-coherence interferometry, wherein near-infrared (NIR) light is directed at a tissue sample. Cross-sectional images are generated from the backscattered light and the time delay of the echoes, which are captured by a detector and presented on a screen. Recent research has concentrated on evolving OCT into a high-speed imaging modality capable of rapidly and accurately collecting data. To overcome challenges related to large equipment and limited access to confined spaces, substantial advancements have been made to both the detector and the OCT source. These developments have led to the creation of portable devices that can be integrated into endoscopes, catheters, and biopsy needles, thereby significantly expanding the range of applications and potential uses.

Two primary types of OCT exist: time-domain OCT (TD-OCT) and Fourier-domain OCT (FD-OCT). TD-OCT, the original concept, relies on white light interferometry. It employs A broadband light source, such as a superluminescent diode (SLD), and a Michelson/Mach-Zehnder interferometer. Light is split by a beam splitter, with one arm directed toward a reference mirror and the other toward the sample or biological tissue. A photodetector detects the backscattered light, compares it to the reference arm, and generates an image. In TD-OCT, both the reference arm and tissue probe move, limiting imaging speed and making the equipment less suitable for clinical applications.Nevertheless, TD-OCT achieves an image resolution of 10 µm or less

FD-OCT emerged as an enhancement over TD-OCT and eliminates the need for a moving reference arm. This advancement results in accelerated imaging speeds and diminished scanning delays. FD- OCT can be subdivided into spectral domain OCT (SD-OCT) and swept-source OCT (SS-OCT). Enamel and dentin cracks and fractures can induce symptoms varying from mild hypersensitivity to tooth devitalization. Clinical examination and transillumination are conventional methods employed to assess cracks and fractures, discerning their extent and depth. Fried et al. conducted an assessment utilizing NIR OCT imaging at 1300 nm to detect and characterize fissures in both enamel and dentin, both in vitro and in vivo.

The diagnosis of cracked tooth syndrome has been facilitated by utilizing SS-OCT images capable of identifying various fracture line characteristics. This diagnostic approach has proven reliable in detecting structural cracks and craze lines. Researchers discovered that 3D SS-OCT enables non-destructive imaging and analysis of fractured enamel, uncovering a correlation between crack patterns, tooth types, and their respective locations. In addition, 3D OCT is more successful than digital radiography and CBCT in detecting vertical root fractures. OCT imaging has also been used to evaluate the root canal system, with studies demonstrating its capacity to examine internal root morphology and identify gaps between the tooth and the post/core junction. Real-time OCT a significant impact on producing videos showcasing resin core growth, leading to improved sealing at the tooth and post margins. Additionally, SS-OCT has been instrumental in detecting the often elusive second mesiobuccal canal (MB2) in maxillary first molars, a challenging task conventionally. These diverse applications underscore the transformative potential of OCT in routine dental practice. In summary, SS-OCT provides valuable information for diagnosing cracked tooth syndrome, identifying root fractures, assessing the root canal system, and improving treatment outcomes.

In the present day of technological advancement, site-specific and specialty-specific OCT systems are already beginning to appear. Many handheld instruments with tiny tips for intraoral dental application have been identified

As more information from in vivo research becomes accessible, the OCT will become more and more integrated into daily dental treatments. OCT may one day be regarded as the gold standard diagnostic instrument for the identification and evaluation of a variety of disorders and lesions affecting the orofacial area. The largest challenge, though, will be teaching oral healthcare workers how to utilize these devices and integrating them into the undergraduate and graduate curricula [

17,

18,

19].

Advanced Instrumentation Techniques (e.g., Rotary and Reciprocating Systems) and Their Benefits

Endodontists utilize both rotary and reciprocating methods for root canal instrumentation, which describe the motions and movements of endodontic files during the shaping and cleaning of root canals. Manufacturers have developed rotary and reciprocating shaping equipment with diverse designs and improved alloys to enhance the predictability and safety of root canal preparation. Clinicians must determine the appropriate equipment and procedures to achieve the optimal final shape by current treatment standards. Two primary considerations persist: determining the acceptable final apical size and establishing the optimal overall form of the prepared root canal.

Rotary systems involve the continuous rotation of endodontic files for efficient and effective dentin and debris removal. These systems utilize nickel-titanium (NiTi) files designed to withstand rotational forces and maintain their shape. NiTi files have evolved since their introduction by Walia in 1988, with manufacturers introducing novel designs, alloys, manufacturing processes, heat treatments, and movements. These advancements aim to enhance the mechanical characteristics of flexibility, efficiency, and cutting ability. Various sizes, tapers, and designs of NiTi files are available, allowing for their use. In different canal shapes and complexities. Examples of popular rotary systems include ProTaper, Twisted File, and Mtwo. In endodontic treatment, rotating tools are now possible because of the invention of nickel-titanium alloys [

20,

21,

22].

Rotary instrumentation is more efficient in deciduous teeth than in permanent teeth due to shorter root canal lengths. Rotary instrumentation reduces debris extrusion and improves obturation efficiency. It improves patient compliance and reduces treatment time for shaping canals, which is a major problem in pediatric endodontics. Pediatric endodontic systems include ProFile, ProTaper, Hero 642, Mtwo, K3, FlexMaster, and Wave One [

22].

The reciprocating movement in endodontics has emerged as a simplified and safer approach for root canal preparation. Initially met with skepticism, it has gained acceptance based on clinical experience and scientific validation over the past decade. Reciprocating systems, such as WaveOne, Reciproc, and OneShape, offer several advantages over rotary movement.

One major advantage is the reduced risk of file fracture. The reciprocating motion minimizes torsional stress on the files, decreasing the likelihood of file separation or breakage. This addresses a significant concern associated with rotary instrumentation. Additionally, the reciprocating movement allows for a single-file approach, simplifying the preparation process. This can save time and enhance efficiency.

The successful validation of reciprocating systems through scientific scrutiny has solidified its place in endodontic practice. Clinicians have quickly adopted this technique due to its clinical benefits. The reduced risk of complications and simplified workflow have made reciprocation a compelling choice for root canal instrumentation [

23,

24,

25].

Bioactive Materials and Regenerative Therapies in Endodontics

Bioceramic Sealers and Their Properties in Obturation

Bioceramics encompass a range of biocompatible materials, such as alumina, zirconia, bioactive glass, glass ceramics, hydroxyapatite, calcium silicate, and resorbable calcium phosphate, among others. These materials interact with surrounding tissues, determining their classification as bioinert, bioactive, or biodegradable. In the field of endodontics, bioactive bioceramics, particularly calcium silicate-based cements (CSCs), are extensively employed because of their outstanding physical and chemical properties, along with their biocompatibility and bioactivity [

3]. Among these materials, mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA), derived from Portland cement, has been extensively studied and utilized in endodontics since its introduction as a root-end filling material in 1993 and subsequent FDA approval in 1997. Despite its favorable biocompatibility and sealing abilities, MTA does have drawbacks, including extended curing time, high expense, and the possibility of discoloration [

3,

26].

Figure 2.

Illustrates different types of bioceramics used in endodontics [

3].

Figure 2.

Illustrates different types of bioceramics used in endodontics [

3].

During the late 2000s and early 2010s, various bioceramics were developed and employed in endodontic treatment, boasting biological properties similar to MTA. These properties include antibacterial effects, low toxicity to cells, and minimal inflammatory responses.Notable examples of such materials include Biodentine, EndoSequence Root Repair Material (ERRM), BioAggregate, and calcium-enriched mixtures (CEM), which have seen widespread adoption in clinical settings. Biodentine, introduced to the dental market in 2009 as an alternative to dentin, offers the advantage of easy penetration into open dentinal tubules, facilitating its efficient use in dental procedures [

3].

Expanding upon the use of bioactive bioceramics in endodontics, they find prominent applications as sealer materials. These sealers play a crucial role in achieving an effective and enduring seal between endodontic obturation materials and the intricate root dentinal walls, ensuring the overall success of the treatment. Moreover, within the broader scope of endodontic procedures, root canal therapy stands as a pivotal intervention. The main goal is to eliminate infection from the complex root canal system while effectively filling and sealing the root canal space. Ceramic sealers have attracted considerable interest in this regard due to their favorable attributes. These sealers, characterized by their alkaline pH, exhibit impressive biocompatibility, bioactivity, and lack of toxicity. Additionally, their dimensional stability and ability to strengthen roots after obturation contributes to their attractiveness, positioning them as a prominent area of focus in endodontic research and clinical application [

22]. In this context, the utilization of a root canal sealer becomes crucial to address imperfections and enhance the adaptability of the root-filling material to the canal walls. Without this intervention, the risk of leakage and failure is notably heightened [

25]. This approach is integral in preventing nutrient loss, averting reinfection of the root canal, and minimizing the accumulation of residual bacteria, thereby effectively controlling endodontic infection. When MTA Fillapex (Angelus, Londrina, Brazil) entered the market in 2010, it marked a milestone as the first sealer based on MTA. The composition of this sealer primarily includes silica, MTA (40%), and a salicylate resin matrix [

22,

27].

Stem Cell Therapies and Tissue Engineering in Regenerative Endodontics

Decay, trauma, or dental abnormalities may induce dental pulp necrosis. Consequently, a bacterial infection in the root canal may lead to apical periodontitis, which can either be asymptomatic or present with pain and other symptoms [

28]. Regenerative endodontics seeks to restore normal pulp function in teeth with reversible pulpitis and to regenerate the pulp-dentin complex in teeth affected by persistent inflammation or necrosis [

29].

Regenerative endodontics has garnered significant attention for its potential to restore normal pulp function in immature and mature teeth. While promising, this approach faces challenges, including the need for multiple appointments, high treatment costs, and the risk of root fractures during long-term calcium hydroxide exposure. Overcoming these hurdles requires further research to streamline protocols and improve accessibility. Additionally, the dental pulp acts as a sensory organ, perceiving temperature and pathogenic stimuli. Neuronal deafferentation following pulp loss may contribute to persistent pain and trigeminal nerve alterations. Pulp regeneration would restore pulp functions, complete root formation, and enhance long-term tooth survival [

28].

Otherwise, Endodontic treatment causes cessation of vascular perfusion or innervation, which makes tooth more brittle, prone to decay and periapical infections, and more likely to fracture [

30]. Scaffolds are important 3-dimensional microstructural materials that offer both structural support and a biological environment for cell growth and tissue formation [

30,

31].

Collagen, a widely used scaffold material, is derived from proteins and is plentiful in various tissues. It possesses biocompatibility, permeability, and biodegradability, which facilitate cell migration, adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. Growth factors, including TGFβ, VEGF, BMP, FGF, PDGF, and NGF, play crucial roles in signaling processes during the regeneration of the dentin-pulp complex. These growth factors attach to cell surface receptors, thereby triggering cellular processes such as proliferation, angiogenesis, and neovascularization. Moreover, growth factors contribute to tissue healing and regeneration by promoting odontogenic differentiation and supporting collagen formation. Tissue engineering in endodontic treatment is focused on the restoration of damaged or lost natural pulp tissue, thus reinstating full tooth functionality while reducing reliance on artificial materials [

30].

Stem cells can be sourced from a variety of tissues, including teeth, buccal mucosa, skin, fat, and bone. Among these, stem cells derived from the pulp of exfoliated deciduous teeth, known as SHED (stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth), represent a particularly promising and accessible option for tissue regeneration. SHEDs are capable of generating dentin-pulp tissues and also exhibit notable immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive properties [

30]. Stem cells, capable of self-renewal and differentiation into diverse cell types, provide novel avenues for tissue regeneration and disease treatment. Oral and maxillofacial tissues harbor adult mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs), making them rich sources for stem cells and potential targets for stem cell-based therapies in dentistry [

32]. The discovery of SHEDs by Miura et al. in 2003 marked a significant milestone in this field [

30].

Endodontic tissue engineering (ETE) comprises two approaches: cell-based (CB-ETE) and primary cell-free (CF-ETE) procedures [

28,

33]. CB-ETE involves ex vivo expansion of cells and their transplantation into scaffolds with growth factors. Obtaining donor tissues or cells and implementing this approach pose challenges [

28,

34]. Conversely, endogenous stem or progenitor cells are used in CF-ETE. attracted by cell-free scaffolds infused with signaling molecules. Introducing autologous platelet products facilitates tissue formation, though the biological outcomes of platelet-based procedures remain uncertain despite successful clinical trials [

28,

35,

36].

This treatment has several challenges, making it less common. These factors encompass the requirement for multiple appointments, the extended duration of the treatment, and the prolonged exposure of the tooth to calcium hydroxide, which increases the risk of root fracture [

28].

Neurovascular Considerations in Endodontics

Understanding neurovascular structures is critical to avoiding iatrogenic injuries and ensuring successful outcomes. Nerve mapping and advancements in anesthesia techniques have reduced procedural risks and improved pain management. Additionally, regenerative endodontics increasingly considers vascular supply to enhance tissue vitality and healing.

Nerve Mapping and Its Relevance in Avoiding Iatrogenic Nerve Injuries During Root Canal Procedures

The first step in non-surgical endodontic treatment is the preparation of the access cavity. This crucial phase is necessary for precisely locating the root canal system, which enables thorough cleaning and shaping to effectively remove microorganisms. Any inaccuracies during this stage may result in various intraoperative complications, including overlooking root canals, causing root perforations, instrument fractures, or compromising the coronal structure’s integrity. Such errors can adversely affect the prognosis of the root canal treatment and consequently jeopardize the survival of the tooth. Several modifications, including calcified canals and diverse anatomical variations, contribute to the increased complexity of non-surgical endodontic treatment. To address these challenges and enhance the results of intricate endodontic cases, 3D-printed guides have been introduced, applying principles akin to those used in guided implant surgery. Within the field of endodontics, 3D templates play a crucial role in pinpointing root canals during non-surgical treatment, particularly in situations with notable risks of procedural errors, such as root perforation, which could significantly compromise the overall success of the treatment [

5].

Endodontic procedures frequently carry the risk of unintentional harm to the inferior alveolar nerve located within the inferior alveolar canal (IAC). Studies highlight the proximity of mandibular first and second molars to the IAC, emphasizing the importance for clinicians to understand the relationships between root apices and the anatomical position of the IAC. Deviations in the positioning of root apices concerning the IAC present a significant risk factor during endodontic procedures, as such inaccuracies can lead to neurological issues such as anesthesia, paresthesia, and pain.The proximity between the inferior alveolar canal (IAC) and the apices of mandibular teeth is of significant importance in various endodontic procedures. Non-surgical treatments on mandibular premolars and molars may potentially cause chemical or mechanical trauma, with over-instrumentation posing a risk of nerve damage. Pressure from root canal sealers and endodontic materials, as well as chemical irritation from irritants, can lead to temporary or permanent damage to the neurovascular bundle, resulting in postoperative paresthesia or anesthesia. Additionally, gutta-percha products, frequently used for root canal filling, may provoke reactions ranging from none to chronic inflammation in both soft and hard tissues, attributable to the presence of oxides and antioxidants in the gutta-percha compound [

37,

38,

39].

Advances in Local Anesthesia Techniques for Precise and Effective Pain Management

Effective pain management during root canal treatment is crucial for various causes. Firstly, patients expect and desire a treatment that is devoid of discomfort. Secondly, adept intra-operative pain control not only minimizes post-operative pain but also streamlines its subsequent management.

Thirdly, a negative experience due to pain during treatment can make patients hesitant about undergoing future root canal procedures. Therefore, achieving pain-free treatment should be the primary goal for every dentist. While local anesthesia is the primary method for pain management during root canal treatment, alternative approaches may be utilized in certain situations. These alternatives may involve pre-treatment with systemic anti-inflammatory medications and methods designed to reduce discomfort associated with the injection process.

Effective pain management during treatment can be achieved through three mechanisms: obstructing nociceptive impulses in peripheral nerves, diminishing nociceptive input at the treatment site, and suppressing pain perception within the central nervous system (CNS). Local anesthetics play a key role in blocking nociceptive impulses generated during treatment, whereas Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective in reducing nociceptive input by inhibiting the production of prostaglandins at the site of treatment or injury.

One of the preoperative strategies involves considering the use of Premedication After diagnosing the condition to alleviate Pain and inflammation at the site of treatment. Topical anesthesia is another strategy that involves applying a numbing agent before local anesthetic injections. Numerous studies have explored the effectiveness of topical anesthesia in decreasing injection pain, yet there is no consensus on its impact on needle insertion or injection-related pain. Results may be influenced by factors like injection site, timing of topical solution application, and the chosen agent. The positive effects of topical anesthesia are not consistently observed for palatal or inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) injections. Formulations containing 60% lignocaine or a combination of 2.5% lignocaine and 2.5% prilocaine show enhanced effects compared to 20% benzocaine. Additionally, topical anesthetics may also exert a placebo effect, signaling to the patient that the treating dentist prioritizes their comfort during the procedure [

40,

41].

Injection Strategies

Proves challenging to isolate the specific impact of topical anesthesia or any other factor, given their concurrent involvement in each injection. Pain experienced during injection may be influenced by factors such as the needle size, injection site, anesthetic type, injection speed, and the use of topical anesthesia. Local anesthetic solutions vary in pH, with lower pH solutions potentially causing a burning sensation due to their acidic content. Limited randomized double-blinded studies examining pain levels from different anesthetic solutions suggest that prilocaine, articaine, and plain lignocaine result in lower pain levels compared to 2% lignocaine with adrenaline (1:80,000 or 1:100,000).

However, Studies with high levels of evidence indicate that there are no significant differences in injection pain among different anesthetic solutions. Regarding injection site effects, the commonly held belief that maxillary buccal infiltration causes less pain than inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) injections was not supported in the sole randomized double-blinded study on this topic. In instances where the injection site has minimal connective tissue, such as in palatal injections in the maxilla, the type of anesthetic solution used does not have a discernible impact on injection pain [

42,

43,

44].

Vascular Supply Considerations in Regenerative Endodontics for Enhanced Tissue Vitality and Healing

In contemporary endodontics, there is a notable shift toward regenerating necrosed pulp tissue rather than resorting to traditional non-surgical root canal treatments, particularly in immature teeth. Regenerative endodontic procedures are biologically centered approaches aimed at replacing damaged dentin and cells within the pulp-dentin complex. Currently, regenerative endodontics encompasses two principal concepts: guided tissue regeneration and tissue engineering [

45,

46,

47].

The goal of therapy is to address complex cases by regenerating functional pulpal tissue through methods known as regenerative endodontic procedures (REPs). Regenerative endodontic therapy involves biologically based techniques designed to replace damaged structures, including dentin and root components, as well as cells of the pulp-dentin complex [

48,

49].

Guided Tissue Regeneration

Guided tissue regeneration, also referred to as revascularization, involves regenerating tissue along with the blood clot formation. The field of tissue engineering with stem cells is continuously advancing, and both these approaches converge with the shared objective of stimulating physiological pulp formation through the activation of stem cells [

45].

Tissue Engineering

Pulpal regeneration has emerged as a fascinating and relatively recent pathway for implementing strategies of tissue engineering. Tissue engineering encompasses three essential elements (A) Scaffolds, (B) Morphogens, and (C) Cell therapy. These components have been utilized individually and in combination across various studies to regenerate the pulp-dentin complex.

Scaffolds

Scaffolds serve as three-dimensional frameworks for cells, acting as extracellular matrices for specified durations. They establish an environment conducive to cell migration and proliferation and can be customized in terms of shape and composition. These materials, whether natural such as collagen, hyaluronic acid, chitosan, and chitin or synthetic such as polylactic acid, polyglycolic acid, tricalcium phosphate, and hydroxyapatite are widely used. Natural polymers typically offer superior biocompatibility, whereas synthetic polymers allow for better control over physicochemical properties, including degradation rate, microstructure, and mechanical strength. For effective endodontic tissue engineering therapy, it is crucial to organize pulp stem cells within a three-dimensional scaffold that supports cell organization and vascularization. This involves using a porous polymer scaffold seeded with pulp stem cells, which should incorporate growth factors to promote stem cell proliferation and differentiation, thereby accelerating tissue development. Additionally, the scaffold may include nutrients to support cell survival and growth, and potentially antibiotics to prevent bacterial contamination in canal systems. The scaffold also provides essential mechanical and biological support for the replacement tissue. In cases of exposed pulp, dentin chips have demonstrated efficacy in stimulating reparative dentin bridge formation. Dentin chips not only offer a matrix for pulp stem cell attachment but also serve as a reservoir for growth factors. The inherent reparative activity of pulp stem cells in response to dentin chips underscores the potential of scaffolds in regenerating the pulp-dentin complex [

48].

Morphogens

Growth factors have the potential to regulate stem cell activity by influencing factors such as increased proliferation, inducing cell differentiation into other tissue types, or encouraging stem cells to produce and release mineralized matrix.Various growth factors, such as transforming growth factors (TGFs), bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and insulin-like growth factor (IGF), have proven effective in the regeneration of the dentin-pulp complex.

In particular, growth factors from the transforming growth factor beta (TGFB) family are crucial for cellular signaling involved in odontoblast differentiation and the stimulation of dentin matrix secretion. Consequently, the use of these growth factors in conjunction with postnatal stem cells is vital for the successful tissue engineering replacement of diseased tooth pulp [

48,

50,

51].

Harnessing Nanotechnology for Advanced Endodontic Solutions

Overview of Nanotechnology in Dentistry:

Nanotechnology has emerged as a transformative force, enabling precise drug delivery, enhanced antimicrobial properties, and improved sealing through nanoparticles and nanofibers. Applications include nanoparticle-based disinfectants, bioactive glass nanoparticles for sealing, and nanofiber scaffolds for guided tissue regeneration. However, challenges such as biocompatibility, cost, and potential environmental impacts require further research.

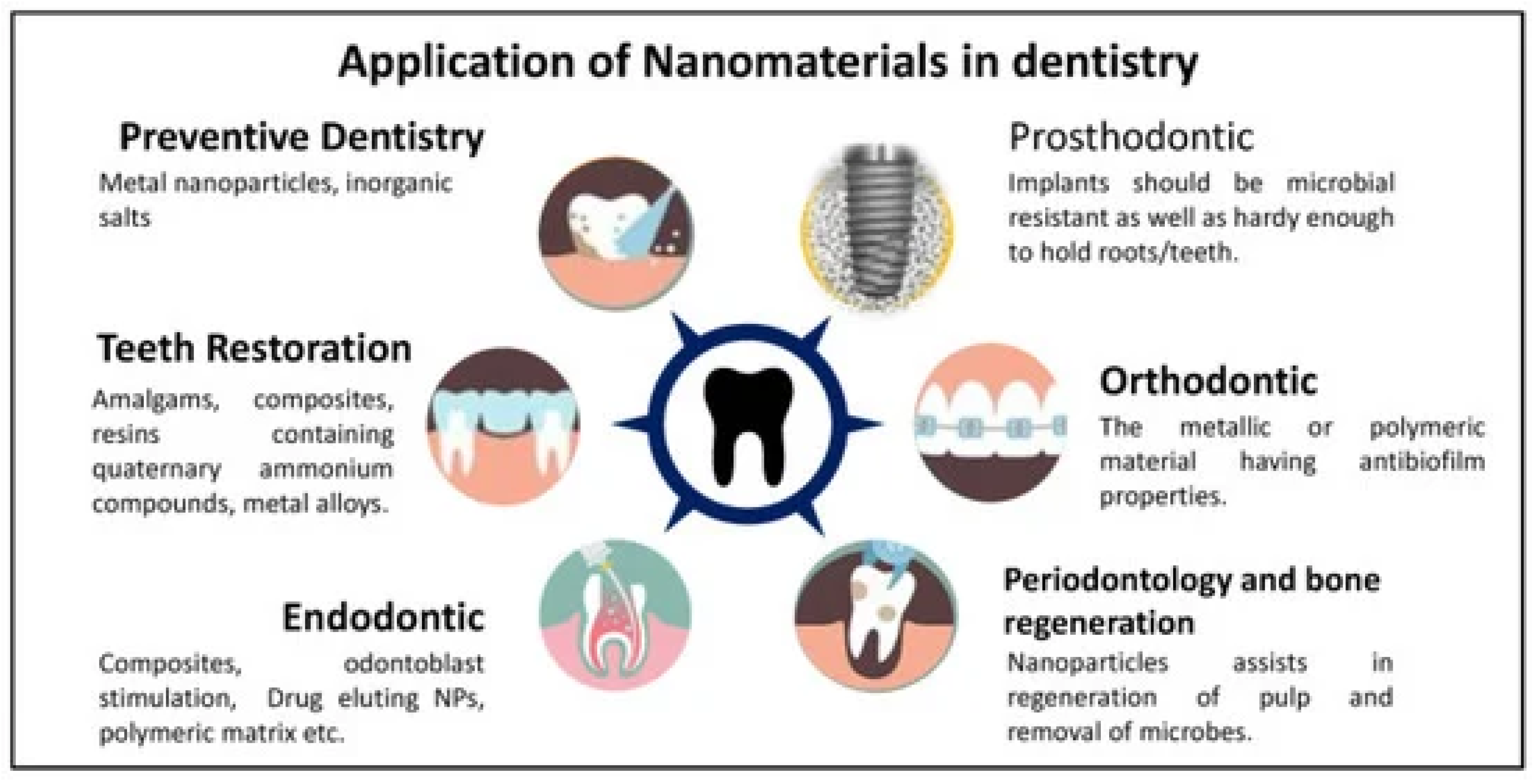

The field of medical science has been greatly influenced by the emergence of nanomaterials, and their remarkable applications have extended to the field of dental science [

52], as presented in (Figure 3). Nanomaterials exhibit various shapes, such as nanotubes, nanorods, and nanowires, with their effectiveness directly proportional to their particle size and increased surface area [

4,

53]. Dentistry, as a rapidly advancing medical discipline, benefits from nanotechnology in areas such as sealers, obturating materials, composites, root repair materials, disinfectants, instrument coatings, drug-related therapy at the nanoscale, and pulp regeneration [

4,

54,

55].

Figure 3.

Nanomaterial applications in dentistry. Reprinted from an open-access source [

54].

Figure 3.

Nanomaterial applications in dentistry. Reprinted from an open-access source [

54].

Nanomaterials in Preventive Dentistry

Nanomaterials significantly enhance dental care products, especially for antibacterial action and remineralization. Key pathogens like Streptococcus mutans and Porphyromonas gingivalis contribute to dental diseases. Metallic nanoparticles such as silver (AgNPs) and gold (AuNPs) provide effective solutions, with AgNPs disrupting bacterial membranes in toothpaste.

Ceramic nanoparticles, particularly hydroxyapatite (HAp), are vital for remineralizing enamel and whitening teeth. Formulations with nano-hydroxyapatite (nHAp) effectively balance antibacterial properties and remineralization, promoting enamel restoration. Silica nanoparticles also show antibacterial effects in mouthwashes, inhibiting oral pathogens. Innovative nanoparticles like nMS-nAg-Chx can transform cariogenic biofilms into non-cariogenic forms, showcasing their preventive potential in dentistry.

In addition, nanocoatings enhance dental implants by promoting osseointegration and reducing inflammation. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles exhibit antimicrobial properties and support osteoblast proliferation, while HAp coatings improve bone integration and implant stability. In orthodontics, nanocoatings reduce plaque formation and friction on braces, enhancing patient comfort. Studies indicate that coated orthodontic wires, such as copper-doped titanium nitride (TiN-Cu), possess antibacterial properties and corrosion resistance, suggesting promising clinical applications [

55].

Their properties and potential applications in oral hygiene products are presented in

Table 1 [

56].

Nanomaterials in Restorative Dentistry

Nanocomposites have revolutionized dental fillings, surpassing traditional materials like amalgam and composite resins. By incorporating nanoparticles (NPs) such as silica and zirconia, these materials exhibit enhanced mechanical strength, improved hardness, and superior wear resistance, which reduces the risk of secondary caries.

Research shows that adding NPs significantly enhances the mechanical properties of dental composite resins. For instance, zirconium dioxide (ZrO2) and titanium dioxide (TiO2) increase flexural strength beyond ISO standards. Modifications using methacrylated quaternary ammonium silanes enhance the dispersion and mechanical characteristics of silica NPs. Additionally, zinc-doped polymeric NPs boost dentin hardness and elasticity, while zirconia and silica NPs improve the flexural strength of 3D-printed dental resins.

In terms of adhesives, nano adhesives enriched with NPs offer better bonding strength and degradation resistance, essential for preventing microleakage. Studies show that NPs like zirconia and silver phosphate enhance antibacterial properties and bond strength. Bioactive glass NPs can reinforce caries-affected dentin, and adding copper and zinc oxide NPs to adhesives has shown no negative impact on bond strength, indicating their potential to improve dental restorations [

55].

Nanomaterials in Endodontics

Embracing these technological advancements in tools and materials is crucial in endodontics to enhance procedures and achieve higher success rates. The diverse array of liposomes, micelles, polymer-based NPs, nano-emulsions, nanogels, and inorganic NPs have extensive applications in nano-drug delivery systems, enabling precise administration with reduced cytotoxicity. In endodontics, nanofibers act as drug carriers, offering biocompatibility, tissue resemblance, and bactericidal properties. These carriers can be classified for pulp revascularization based on their composition, including polyacids like lactic, glycolic, and caprolactone [

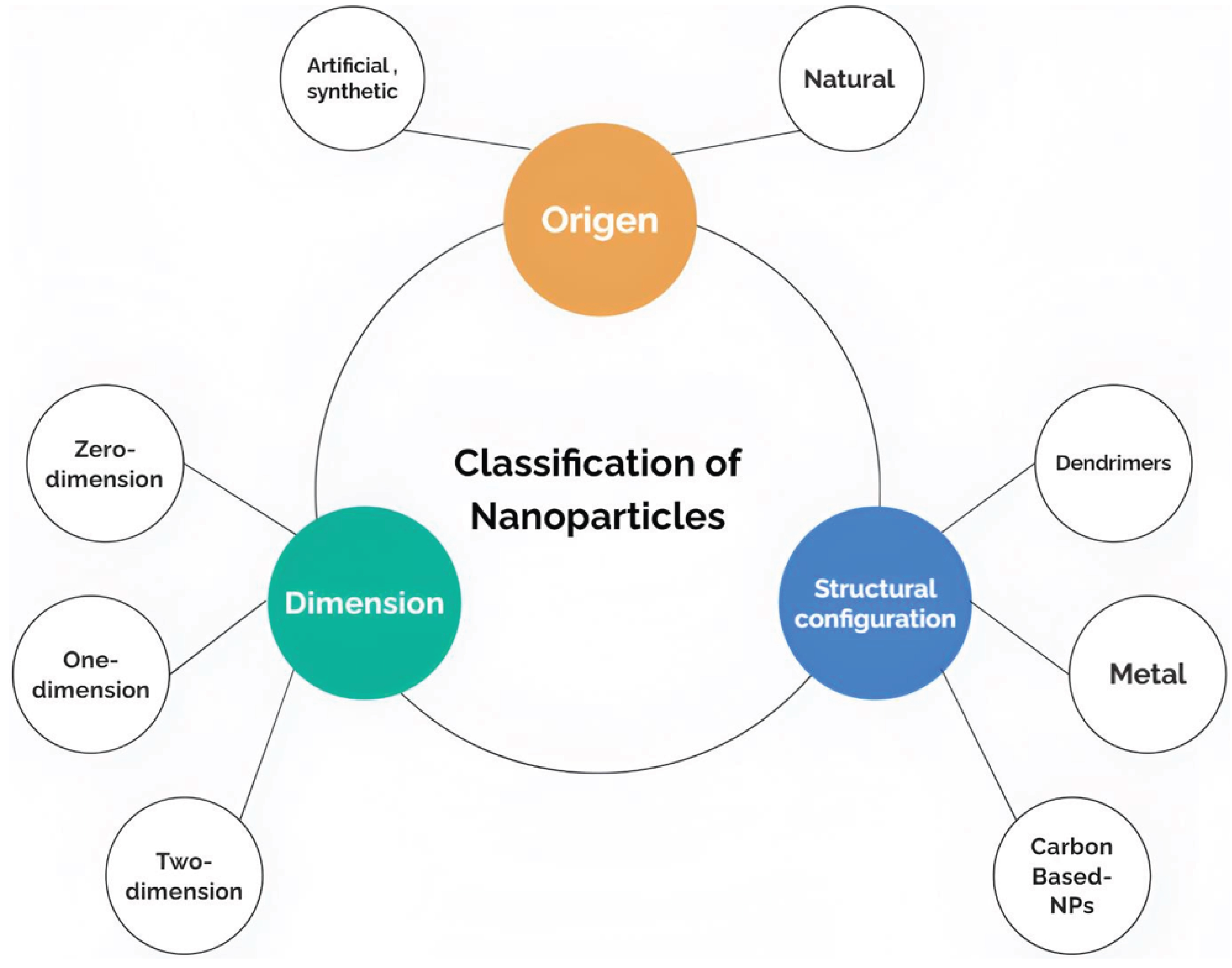

4]. Nanoparticles, due to their superior bonding capabilities and surface chemistry, offer a promising approach to combat microbial biofilms within the root canal system, addressing a persistent concern in endodontics.

Nanoparticles (NPs) are systematically categorized based on their origin, dimension, and structural configuration, as illustrated in (Figure 4). Moreover, the utilization of nanoparticles as antibacterial agents involves employing distinct mechanisms that differ from the antimicrobial mechanisms of conventional therapies [

52,

57]. NPs possess certain advantages due to their inherent characteristics, such as reduced stability, weaker molecular bonding, and interactions with other molecules. These characteristics contribute to their greater efficacy [

58]. Moreover, the noteworthy volume to surface area ratio of NPs affect the energy dynamics of these particles. NPs also contribute to disrupting cell wall synthesis and inhibiting various enzymes, such as DNA gyrase and DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Furthermore, to maximize the benefits provided by NPs, their mechanical, optical, chemical, and electrical properties can be tailored [

52].

Figure 4.

Shows Nanoparticles Classification [

52].

Figure 4.

Shows Nanoparticles Classification [

52].

Nanoparticles in Root Canal Disinfection

Endodontic disorders are among the most costly dental issues in developed countries, necessitating effective cleaning and disinfection of root canals. Nanoparticles (NPs) play a crucial role in enhancing endodontic disinfection due to their ability to penetrate complex canal systems, surpassing the limitations of traditional disinfectants [

55]. Nanoparticles (NPs) exhibit considerable potential at achieving effective root canal disinfection, emphasizing their antibacterial spectrum and biocompatibility for prospective clinical applications.

Chitosan Nanoparticles (CS): Chitosan, a biopolymer derived from chitin, can be synthesized in multiple forms, including powders, hydrogels, films, and scaffolds. Notably, CS possesses pronounced antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal properties, with a higher susceptibility observed in Gram-positive bacteria compared to Gram-negative strains. The mechanism underlying the antibacterial activity of CS involves electrostatic interactions between the positively charged chitosan and the negatively charged bacterial cell membranes. This interaction increases cell wall permeability, resulting in cell lysis and the subsequent release of intracellular components, which ultimately leads to bacterial death.

The advantages of chitosan nanoparticles are manifold. They are non-toxic to mammalian cells, making them suitable for biomedical applications. Furthermore, chitosan exhibits color compatibility with dental tissues, which is critical for aesthetic considerations in restorative dentistry. Additionally, chitosan is cost-effective and readily available, enhancing its practicality for clinical use. Its chemical structure allows for easy modification, enabling the tailoring of its properties to enhance antimicrobial efficacy [

59].

Bioactive Glass Nanoparticles (BAG): Comprised of silicon dioxide, sodium oxide, calcium dioxide, and phosphorus pentoxide, BAG nanoparticles are characterized by their amorphous nature. Their antibacterial action is attributed to the elevation of pH upon ion release in an aqueous environment, osmotic effects that can inhibit bacterial growth, and the precipitation of calcium and phosphorus on bacterial surfaces, facilitating mineralization [

59].

Silver Nanoparticles: Renowned for their antibacterial properties, silver nanoparticles disrupt bacterial membranes by interacting with sulfhydryl groups in proteins and DNA. This interaction alters cellular functions, leading to increased membrane permeability and leakage of cellular constituents [

55,

59].

Emerging disinfection strategies are designed to overcome the limitations of traditional methods by targeting biofilm bacteria in both the main canals and the uninstrumented regions of the root canal system. Innovations include the incorporation of NPs into root canal sealers, functionalization of NPs to enhance antibacterial properties, and modifications for antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (PDT) [

59].

Commonly used disinfectants include calcium hydroxide, potassium iodine, and chlorhexidine (CHX). Studies have demonstrated the efficacy of CHX-loaded biodegradable NPs for sustained release and antibacterial action against

Enterococcus faecalis. Other research highlights the use of propolis NPs and calcium hydroxide-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NPs, both exhibiting significant antimicrobial effectiveness. Despite their advantages, concerns regarding potential tooth discoloration and cytotoxicity highlight the need for further investigation into the long-term effects and safety of NPs in endodontic applications [

55,

60].

Disinfection of the endodontic system is primarily accomplished using calcium hydroxide and/or antibiotic pastes. Although calcium hydroxide is effective, its ability to penetrate dentinal tubules is constrained by its low solubility. Triple antibiotic paste (TAP) has demonstrated efficacy; however, it may hinder the revascularization of newly formed pulpal tissue, adversely affecting stem cell differentiation and potentially leading to dentin discoloration. As a result, TAP has largely been supplanted by double-antibiotic paste (DAP), which omits minocycline to prevent discoloration. Nonetheless, antibiotic pastes can be challenging to remove from the endodontic system and may contribute to dentin decalcification with prolonged application [

61].

Nano-Based Sealers

Traditional sealers often lack antimicrobial properties and can allow bacterial growth. The integration of antibacterial nanoparticles (NPs) into root canal sealers enhances both the direct and diffusible antibacterial properties of these materials. Chitosan nanoparticles (CS NPs) have been shown to diminish the adhesion of

Enterococcus faecalis to root canal dentin. Additionally, quaternary ammonium polyethyleneimine NPs can augment the antibacterial efficacy of various root canal sealers and temporary restorative materials [

55,

59].

Zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs have been shown to improve sealants’ physical strength and antibacterial properties, effectively combating

Streptococcus mutans. Further studies on needle-like ZnO nanostructures indicate their ability to disrupt bacterial membranes and improve sealant properties without compromising mechanical integrity. Innovative formulations using nano-apatite and calcium silicate-based sealers have demonstrated promising sealing abilities and biocompatibility. Propolis-loaded NPs and calcium phosphate (CaP) NPs enhance sealing performance while providing antibacterial benefits and remineralization [

55].

These nanoparticles exert bactericidal effects through adsorption and penetration into the bacterial cell wall. Subsequently, they interact with the protein and lipid layers of the cell membrane, obstructing the exchange of essential ions. Furthermore, bioactive glass nanoparticles (BAG NPs) facilitate the closure of interfacial gaps between the root canal walls and core filling materials, contributing to improved sealing and overall treatment efficacy [

59].

Nanofibers and Their Applications in Pulp Regeneration

Nanofibers, particularly those synthesized from polycaprolactone (PCL), represent a notable advancement in the domain of pulp regeneration, especially for young permanent teeth affected by pulpal necrosis. The utilization of electrospinning techniques enables the creation of nanofiber scaffolds that closely mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM), thereby fostering an optimal environment for cellular adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. Notably, scaffolds infused with fibronectin (FN) have been developed to enhance the bioactive potential of human apical papilla cells (hAPCs).

Research indicates that the orientation of nanofibers, whether aligned or randomly arranged—significantly influences cellular morphology and behavior, promoting cell migration and collagen synthesis. Furthermore, these scaffolds can be combined with bioactive molecules, such as growth factors and antibiotics, to facilitate controlled release, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy. This innovative approach effectively addresses the limitations of conventional therapies by promoting efficient healing processes and supporting the regeneration of healthy pulp tissue. Overall, the application of nanofibers in pulp regeneration not only aids in the restoration of dental health but also offers a promising strategy for guided tissue regeneration in endodontically compromised teeth [

61,

62].

Future Directions and Unresolved Questions

Looking beyond the current avant-garde of endodontic science, the next evolutionary wave hinges on embracing nanotechnology not as a mere adjunct but as the central force reshaping the biological, technological, and clinical architectures of pulp therapy. Yet within this exciting vision lie profound, unanswered questions that challenge conventional wisdom and demand courageous new lines of inquiry. Can future nanomaterials transcend static functionalities to become truly adaptive, sensing early molecular disturbances in the pulp’s microenvironment and dynamically deploying tailored antimicrobials or growth factors before irreversible damage occurs? Will gene editing and synthetic biology converge with advanced nano-engineering, enabling patient-specific molecular “fingerprinting” that informs entirely bespoke regenerative strategies? Could clinicians one day direct bioactive nanofibers, programmed at a genomic level, to induce target cells into an odontoblastic phenotype, selectively secreting new dentinal matrix that not only repairs structural deficits but also confers enhanced resilience against future insults? Beyond conventional pulp-dentin regeneration, what if nanomaterials could subtly reshape the oral ecosystem itself—engineering symbiotic biofilms rather than attempting to eradicate all microbial life, thus promoting a balanced microenvironment that inherently resists pathogenic incursions?

To achieve this, integrative frameworks must be designed, forging interdisciplinary collaborations among molecular biologists, materials scientists, data engineers, and clinical experts. This raises fresh questions: how can AI-driven imaging analytics merge with nanodiagnostic tools to generate a continuous feedback loop, adapting treatment protocols in real-time based on evolving biochemical signatures within the tooth? Might sophisticated machine learning algorithms predict disease trajectories early enough to preemptively re-establish pulp vitality, guided by ultrafine robotic endodontic instrumentation? The reliability and reproducibility of these cutting-edge methods remain uncertain, posing yet another line of inquiry: what standards, validation protocols, and regulatory pathways are required to ensure clinical translation is both safe and ethically sound? And as these sophisticated interventions gain traction, how should dental education evolve to equip future endodontists with the multifaceted skill sets—ranging from genomic interpretation to nanorobotic device calibration—necessary to navigate a dramatically altered therapeutic landscape?

In pushing beyond current horizons, novel questions of sustainability and equity emerge: can these advanced nano-therapeutics be scaled and simplified for global dissemination, ensuring that the benefits of this technological renaissance do not remain confined to elite clinics in well-resourced regions? Furthermore, understanding and mitigating unintended consequences—such as the potential environmental impacts of widespread nanomaterial use, or the long-term stability of engineered biofilms—will be essential. As endodontics strides into this new era of complexity and promise, the field must embrace a mindset that is simultaneously visionary and cautious, daring to ask not only how to enhance pulp vitality but also how to align these breakthroughs with broader ethical, social, and ecological values. Only by grappling with these profound, interconnected questions can endodontics truly transcend its past and present, forging a biofuturistic paradigm that redefines both the practice of dentistry and the very meaning of oral health.

Conclusions

Endodontics, once defined by rudimentary tools and conventional treatment approaches, has evolved into a remarkably sophisticated discipline, propelled by continuous advancements in imaging technologies, regenerative methodologies, biomimetic materials, and nanotechnology. The integration of CBCT, OCT, and other high-resolution imaging modalities has enriched diagnostic precision, mitigating treatment uncertainties and streamlining complex interventions. Rotating and reciprocating instrumentation systems, alongside regenerative procedures driven by stem cells and growth factors, have reconceptualized the traditional goals of endodontic therapy—no longer merely preserving teeth, but aiming to reestablish lost vitality and restore the dentin-pulp complex. Nanotechnology has emerged as a cornerstone of this paradigm shift, enabling the engineering of bioactive surfaces, antimicrobial carriers, and drug delivery systems designed to orchestrate tissue healing at the molecular scale. Sealing materials infused with nanoparticles now offer improved mechanical strength, effective antibiofilm strategies, and enhanced biocompatibility, ultimately reinforcing the structural integrity and longevity of treated teeth.

Importantly, these multifaceted innovations are not isolated achievements but form a dynamic, interdependent network. High-end imaging guides strategic placement of regenerative scaffolds and nanomaterials; synergistic interactions between bioactive ceramics and nanoparticles optimize sealing and disinfection; and precise understanding of neurovascular intricacies refines anesthetic protocols and reduces procedural morbidity. Such a holistic perspective has positioned endodontics as a field that transcends the confines of its original scope, steadily progressing toward biologically inspired solutions that align with the principles of minimally invasive dentistry and patient-centric care.

Collectively, these breakthroughs reaffirm that endodontics, as a specialty, is poised to meet evolving clinical challenges with agility and innovation. By doing so, it not only improves clinical outcomes but also enhances patient satisfaction, comfort, and trust in dental interventions. The current body of knowledge illuminates a clear trajectory: endodontics is rapidly maturing into a domain where advanced science, engineering principles, and biological insight converge, generating treatment solutions that would have seemed visionary only a few decades ago.

Author Contributions

All authors have made the conception and design of the review paper, contributed significantly to the drafting and refinement of the manuscript, and provided substantial intellectual input throughout the analysis and critical review process. Additionally, All authors have actively participated in the acquisition of relevant literature and materials, ensuring the accuracy and completeness of the content. Furthermore, all authors have been involved in the critical review and revision of the manuscript, providing valuable insights and feedback. Finally, all authors have given their final approval of the version to be published and take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to our supervisor, XX, for his invaluable contributions to this research review paper. His significant input in refining the content and providing final approval of the manuscript played a crucial role in its completion. We are so deeply grateful to Ali Alsuraifi for his exceptional contributions in creating high-quality illustrations that enriched the presentation of our work. We also would like to extend our heartfelt appreciation to Abdullah Ayad for his outstanding contributions to this research review paper. His leadership in guiding the entire review process and his exceptional contributions were instrumental in shaping the quality and completeness of this work.

Declaration Regarding the Use of AI-Assisted Readability Enhancement

I hereby affirm that the utilization of AI-assisted tools in the refinement of the manuscript was strictly limited to enhancing its readability. At no point were AI technologies employed to supplant essential authorial responsibilities, including the generation of scientific, pedagogic, or medical insights, the formulation of scientific conclusions, or the issuance of clinical recommendations. The implementation of AI for readability enhancement was rigorously supervised under the discerning eye of human oversight and control.

References

- Spagnuolo, G. (2022). Cone-Beam computed tomography and the related scientific evidence. Applied Sciences, 12(14), 7140. [CrossRef]

- Chogle, S., Zuaitar, M., Sarkis, R., Saadoun, M., Mecham, A., & Zhao, Y. (2020). The recommendation of Cone-beam computed tomography and its effect on endodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. Journal of Endodontics, 46(2), 162–168. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X., & Xu, X. (2023). Bioceramics in Endodontics: updates and future Perspectives. Bioengineering, 10(3), 354. [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewski, W., Dobrzyński, M., Zawadzka-Knefel, A., Lubojański, A., Dobrzyński, W., Janecki, M., Kurek, K., Szymonowicz, M., Wiglusz, R. J., & Rybak, Z. (2021). Nanomaterials application in endodontics.

-

Materials, 14(18), 5296. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D. C., Reis, E., Marques, J. A., Falacho, R. I., & Palma, P. J. (2022). Guided Endodontics: Static vs. Dynamic Computer-Aided Techniques—A Literature Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(9), 1516. [CrossRef]

- Kaasalainen, T., Ekholm, M., Siiskonen, T., & Kortesniemi, M. (2021). Dental cone beam CT: An updated review. Physica Medica, 88, 193-217. [CrossRef]

- Mazzi-Chaves, J. F., De Camargo, R. V., Borges, A. F., Silva, R. G., Pauwels, R., Silva-Sousa, Y. T. C., & Sousa-Neto, M. D. (2021). Cone-Beam Computed Tomography in Endodontics—State of the Art. Current Oral Health Reports, 8(2), 9–22. [CrossRef]

- Luz, L. B., Vizzotto, M. B., Xavier, P. N. I., Vianna-Wanzeler, A. M., da Silveira, H. L. D., & Montagner, F. (2022). The impact of cone-beam computed tomography on diagnostic thinking, treatment option, and confidence in dental trauma cases: a before and after study. Journal of Endodontics, 48(3), 320-328. [CrossRef]

- Alzamzami, Z. T., Abulhamael, A. M., Talim, D. J., Khawaji, H., Barzanji, S. A., & Roges, R. (2019). Cone- beam Computed tomographic Usage: Survey of American Endodontists. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, 20(10), 1132–1137. [CrossRef]

- Sajja, S., Lee, Y., Eriksson, M., Nordström, H., Sahgal, A., Hashemi, M.,… & Ruschin, M. (2020). Technical principles of dual-energy cone beam computed tomography and clinical applications for radiation therapy. Advances in radiation oncology, 5(1), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Topală, F., Nica, L., Boariu, M., Negruțiu, M. L., Sinescu, C., Marinescu, A., Cirligeriu, L. E., Stratul, Ş., Rusu, D., Chincia, R., Duma, V., & Podoleanu, A. G. (2021). En-face optical coherence tomography analysis of gold and silver nanoparticles in endodontic irrigating solutions: An in vitro study. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 22(3). [CrossRef]

- Patel, S., Kelly, R., & Pimentel, T. (2022). The Use of Cone-Beam Computed Tomography in Endodontics, 719–733. [CrossRef]

- Rashed, B., Iino, Y., Ebihara, A., & Okiji, T. (2019). Evaluation of Crack Formation and Propagation with Ultrasonic Root-End Preparation and Obturation Using a Digital Microscope and Optical Coherence Tomography. Scanning, 2019, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y., Yoshiyama, M., Tagami, J., & Sumi, Y. (2020). Evaluation of dental caries, tooth crack, and age-related changes in tooth structure using optical coherence tomography. Japanese Dental Science Review, 56(1), 109-118. [CrossRef]

- Janjua, O. S., Jeelani, W., Khan, M. I., Qureshi, S. M., Shaikh, M. S., Zafar, M. S., & Khurshid, Z. (2023). Use of Optical Coherence Tomography in Dentistry. International Journal of Dentistry, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Peters, O. A., & Arias, A. (2022). Rotary and Reciprocating Motions During Canal Preparation. Endodontic Advances and Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines, 283-310. [CrossRef]

- Luong, M. N., Shimada, Y., Araki, K., Yoshiyama, M., Tagami, J., & Sadr, A. (2020). Diagnosis of occlusal caries with dynamic slicing of 3D optical coherence tomography images. Sensors, 20(6), 1659. [CrossRef]

- Janjua, O. S., Jeelani, W., Khan, M. I., Qureshi, S. M., Shaikh, M. S., Zafar, M. S., & Khurshid, Z. (2023). Use of Optical Coherence Tomography in Dentistry. International Journal of Dentistry, 2023, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Jindal, L., Bhat, N., Mehta, S., Bansal, S., Sharma, S., & Kumar, A. (2020). Rotary endodontics in pediatric dentistry: Literature review. Int J Health Biol Sci, 3(2), 09-13.

- Liang, Y., & Yue, L. (2022). Evolution and development: engine-driven endodontic rotary nickel-titanium instruments. International journal of oral science, 14(1), 12. [CrossRef]

- Souza, E. M., Silva, E. J. N. L., De Deus, G., Versiani, M. A., & Zuolo, M. L. (2021). Scientific and educational aspects of reciprocating movement. In Springer eBooks (pp. 215–248). [CrossRef]

- Munitić, M. Š., Peričić, T. P., Utrobičić, A., Bago, I., & Puljak, L. (2019). Antimicrobial efficacy of commercially available endodontic bioceramic root canal sealers: A systematic review. PLOS ONE, 14(10), e0223575. [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, S., Katge, F., Poojari, M., & Patil, D. P. (2020). Clinical evaluation and comparison of obturation quality using pediatric rotary file, rotary endodontic… ResearchGate. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353339193_Clinical_Evaluation_and_Comparison_of_Obturation_Quality_Using_Pediatric_Rotary_File_Rotary_Endodontic_File_and_H_File_in_Root_Canal_of_Primary_Molars_A_Double_Blinded_Randomized_Controlled_Trial.

- De Pedro-Muñoz, A., Rico-Romano, C., Sánchez-Llobet, P., Montiel-Company, J. M., & Mena-Alvarez, J. (2024). Cyclic Fatigue Resistance of Rotary versus Reciprocating Endodontic Files: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(3), 882. [CrossRef]

- Pontoriero, D. I. K., Cagidiaco, E. F., Cardinali, F., Fornara, R., Amato, M., Grandini, S., & Ferrari, M. (2022). Sealing ability of two bioceramic sealers used in combination with three obturation techniques. Journal of Osseointegration, 14(3), 143-148. [CrossRef]

- Parirokh, M.; Torabinejad, M. Mineral trioxide aggregate: A comprehensive literature review—Part III: Clinical applications, drawbacks, and mechanism of action. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess D, Solomon E, Spears R, He J (2011) Retreatability of a bioceramic root canal sealing material. J Endod 37: 1547–1549. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widbiller, M., Knüttel, H., Meschi, N., & Terol, F. D. (2022). Effectiveness of endodontic tissue engineering in treatment of apical periodontitis: A systematic review. International Endodontic Journal, 56(S3), 533–548. [CrossRef]

- Thalakiriyawa, D. S., & Dissanayaka, W. L. (2023). Advances in Regenerative Dentistry Approaches: an update. International Dental Journal. [CrossRef]

- Sugiaman, V. K., Djuanda, R., Pranata, N., Naliani, S., Demolsky, W. L., & Jeffrey, J. (2022). Tissue Engineering with Stem Cell from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth (SHED) and Collagen Matrix, Regulated by Growth Factor in Regenerating the Dental Pulp. Polymers, 14(18), 3712. [CrossRef]

- Dong C, Lv Y. Application of Collagen Scaffold in Tissue Engineering: Recent Advances and New Perspectives. Polymers (Basel). 2016 Feb 4;8(2):42. [CrossRef]

- Mitsiadis, TA, Orsini, G, & Jimenez-Rojo, L (2015) Stem cell- based approaches in dentistry European Cells and Materials (ECM), 30, 248-57. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.M., Huang, G.T., Sigurdsson, A. & Kahler, B. (2021) Clinicalcell- based versus cell-free regenerative endodontics: clarifica-tion of concept and term. International Endodontic Journal, 54,887– 901. [CrossRef]

- Ohkoshi, S., Hirono, H., Nakahara, T. & Ishikawa, H. (2018) Dentalpulp cell bank as a possible future source of individual hepato-cytes. World Journal of Hepatology, 10, 702–707. [CrossRef]

- Galler, K. M., & Widbiller, M. (2017). Perspectives for cell-homing approaches to engineer dental pulp. Journal of Endodontics, 43(9), S40–S45. [CrossRef]

- Galler, K.M. & Widbiller, M. (2020) Cell-free approaches for dentalpulp tissue engineering. Journal of Endodontics, 46, S143–S149. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S., Alharbi, H. M., Alharbi, A. S., Soliman, M., Eldwakhly, E., & Abdelhafeez, M. M. (2022). Assessment of the Proximity of the Inferior Alveolar Canal with the Mandibular Root Apices and Cortical Plates—A Retrospective Cone Beam Computed Tomographic Analysis. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(11), 1784. [CrossRef]

- Koray, M., & Tosun, T. (2019). Oral mucosal trauma and injuries. In IntechOpen eBooks. [CrossRef]

- Kämmerer, P. W., Heimes, D., Hartmann, A., Kesting, M., Khoury, F., Schiegnitz, E., Thiem, D. G. E., Wiltfang, J., Al-Nawas, B., & Kämmerer, W. (2024). Clinical insights into traumatic injury of the inferior alveolar and lingual nerves: a comprehensive approach from diagnosis to therapeutic interventions. Clinical Oral Investigations, 28(4). [CrossRef]

- Thiem, D.G.E., Schnaith, F., Van Aken, C.M.E. et al. Extraction of mandibular premolars and molars: comparison between local infiltration via pressure syringe and inferior alveolar nerve block anesthesia.Clin Oral Invest 22, 1523–1530 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Anesthetic Effectiveness of articaine and lidocaine in Pediatric patients during Dental Procedures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. (2020, July 15). PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32847666/.

- Abbott, P., & Parirokh, M. (2018). Strategies for managing pain during endodontic treatment. Australian Endodontic Journal, 44(2), 99–113. [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, F., Ege, B., & Tosun, S. (2021). The effect ofpre- operative submucosal administration of dexamethasone, tramadol, articaine on the success rate of inferior alveolarnerve block on mandibular molars with symptomaticirreversible pulpitis: A randomized, double- blindplacebo- controlled clinical trial. International EndodonticJournal, 54(11), 1982-1992.

- Nivedha, V., Sherwood, I. A., Abbott, P. V., Ramaprabha, B., & Bhargavi, P. (2020). Pre-operative ketorolac efficacy with different anesthetics, irrigants during single visit root canal treatment of mandibular molars with acute irreversible pulpitis. Australian Endodontic Journal, 46(3), 343–350. [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, H., Kaushik, M., & Sharma, R. (2016). Regenerative endodontics—creating new horizons. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials, 104(4), 676-685. [CrossRef]

- Khan, I., Neumann, C., & Sinha, M. (2020). Tissue regeneration and reprogramming. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 515–534). [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Yang, G., Li, J., Ding, M., Zhou, N., Dong, H., & Mou, Y. (2020). Stem cell therapies for periodontal tissue regeneration: a network meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Stem cell research & therapy, 11(1), 427. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. H. (2018). Regenerative endodontic (Doctoral dissertation, Ministry of High Education And Scientific Research University of Baghdad College of Dentistry Regenerative endodontic A project submitted to College of Dentistry, Baghdad University). Available online: https://shorturl.at/JlcFs.

- Wei, X., Yang, M., Yue, L. et al. Expert consensus on regenerative endodontic procedures. Int J Oral Sci 14, 55 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Yuan, G., & Yang, G. (2021). Effects of transforming growth factor-β1 on odontoblastic differentiation in dental papilla cells is determined by IPO7 expression level. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 545, 105–111. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y., Cheng, X., Liu, X., Guo, Q., Wang, Z., Fu, Y., He, W., & Yu, Q. (2023). Transforming growth factor-β1 promotes early odontoblastic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells via activating AKT, Erk1/2 and p38 MAPK pathways. Journal of dental sciences, 18(1), 87–94.

- Raura, N., Garg, A., Arora, A., & Roma, M. (2020). Nanoparticle technology and its implications in endodontics: a review. Biomaterials Research, 24(1). [CrossRef]

- Demir, E. (2021). A review on nanotoxicity and nanogenotoxicity of different shapes of nanomaterials. Journal of Applied Toxicology, 41(1), 118-147. [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasalu, P.K.P.; Dora, C.P.; Swami, R.; Jasthi, V.C.; Shiroorkar, P.N.; Nagaraja, S.; Asdaq, S.M.B.; Anwer, K. Nanomaterials in Dentistry: Current Applications and Future Scope. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolae, C. L., Pîrvulescu, D. C., Niculescu, A. G., Rădulescu, M., Grumezescu, A. M., & Croitoru, G. A. (2024). An Overview of Nanotechnology in Dental Medicine. Journal of Composites Science, 8(9), 352.

- Carrouel, F.; Viennot, S.; Ottolenghi, L.; Gaillard, C.; Bourgeois, D. Nanoparticles as Anti-Microbial, Anti-Inflammatory, and Remineralizing Agents in Oral Care Cosmetics: A Review of the Current Situation. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spirescu, V. A., Chircov, C., Grumezescu, A. M., & Andronescu, E. (2021). Polymeric nanoparticles for antimicrobial therapies: An up-to-date overview. Polymers, 13(5), 724. [CrossRef]

- Capuano N, Amato A, Dell’Annunziata F, Giordano F, Folliero V, Di Spirito F, More PR, De Filippis A, Martina S, Amato M, Galdiero M, Iandolo A, Franci G. Nanoparticles and Their Antibacterial Application in Endodontics. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023 Dec 1;12(12):1690. [CrossRef]

- Kishen, A., & Shrestha, A. (2015). Nanoparticles for endodontic disinfection. Nanotechnology in endodontics: current and potential clinical applications, 97-119.

- Roig-Soriano X, Souto EB, Elmsmari F, Garcia ML, Espina M, Duran-Sindreu F, Sánchez-López E, González Sánchez JA. Nanoparticles in Endodontics Disinfection: State of the Art. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Jul 21;14(7):1519. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Candrea, S., Muntean, A., Băbțan, A. M., Boca, A., Feurdean, C. N., Bordea, I. R., … & Ilea, A. (2024). The Use of Nanofibers in Regenerative Endodontic Therapy—A Systematic Review. Fibers, 12(5), 42.

- Leite, M. L., Soares, D. G., Anovazzi, G., Mendes Soares, I. P., Hebling, J., & de Souza Costa, C. A. (2021). Development of fibronectin-loaded nanofiber scaffolds for guided pulp tissue regeneration. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials, 109(9), 1244-1258.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).