Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Construction of Single-Chain eCGβ/α

2.3. Transfection into CHO DG44 Cells and Isolation of Single Cells Expressing rec-eCG Proteins

2.4. Production and Quantitation Analysis of rec-eCG Proteins

2.5. Western Blotting and Enzymatic Digestion of N-linked Oligosaccharides

2.6. Construction of eLH/CGR, rLH/CGR, and rFSHR Expression Vectors

2.7. cAMP Analysis Using Homogeneous Time-Resolved Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (HTRF) Assays

2.8. Measurement of pERK1/2 Levels by Homogeneous Time-Resolved Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (HTRF) Assays

2.9. Measurement of Phospho-ERK1/2 by Western Blot

2.10. Measurement of β-Arrestin 2 Recruitment

2.11. Data and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Single Cells Expressing rec-eCG in CHO-DG44 Cells

3.2. Western Blot Analysis of rec-eCG

3.3. cAMP Responsiveness of rec-eCG in Cells Expressing eLH/CGR, rLH/CGR, and rFSHR

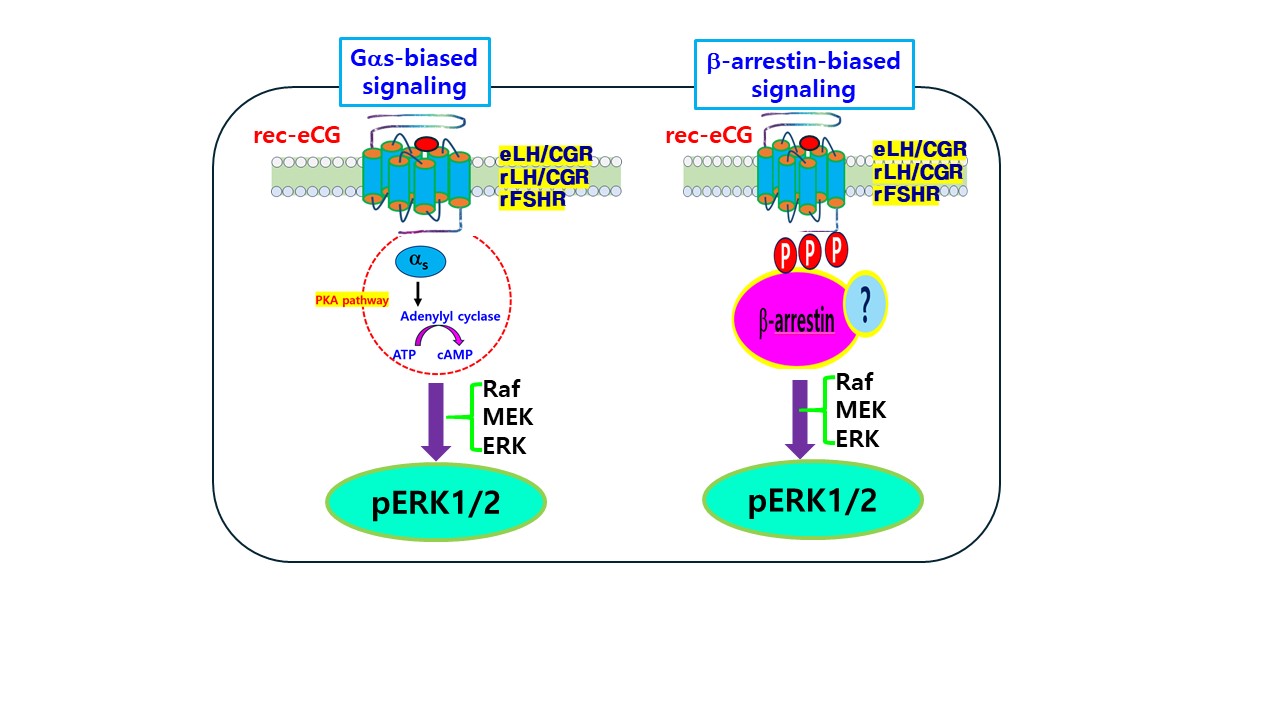

3.4. Identification of eLH/CGR-, rLH/CGR-, and rFSHR-Mediated pERK1/2 Activation

3.5. β-arrestin 2 Recruitment in PathHunter CHO-K1 Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chopineau, M.; Maurel, M.-C.; Combarnous, Y.; Durand, P. Topography of equine chorionic gonadotropin epitopes relative to the luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor interaction sites. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1993, 92, 229–239. [CrossRef]

- Combarnous, Y.; Guillo, F.; Martinat, N. Comparison of in vitro follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) activity of equine gonadotropins (luteinizing hormone, FSH, and chorionic gonadotropin) in male and female rats. Endocrinology 1984, 115, 1821–1827. [CrossRef]

- Galet, C.; Guillou, F.; Foulon-Gauze, F.; Combarnous, Y.; Chopineau, M. The β104-109 sequence is essential for the secretion of correctly folded single-chain βα horse LH/CG and for its activity. J. Endocrinol. 2009, 203, 167–174.

- Legardinier, S.; Poirier, J.-C.; Klett, D.; Combarnous, Y.; Cahoreau, C. Stability and biological activities of heterodimeric and single-chain equine LH/chorionic gonadotropin variants. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 40, 185–198. [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.G.; Parsons, T.F. Glycoprotein Hormones: Structure and Function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1981, 50, 465–495. [CrossRef]

- Min, K.-S.; Hattori, N.; Aikawa, J.-I.; Shiota, K.; Ogawa, T. Site-Directed Mutagenesis of Recombinant Equine Chorionic Gonadotropin/Luteinizing Hormone: Differential Role of Oligosaccharides in Luteinizing Hormone- and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone-Like Activities.. Endocr. J. 1996, 43, 585–593. [CrossRef]

- Min, K.-S.; Hiyama, T.; Seong, H.-H.; Hattori, N.; Tanaka, S.; Shiota, K. Biological Activities of Tethered Equine Chorionic Gonadotropin (eCG) and Its Deglycosylated Mutants. J. Reprod. Dev. 2004, 50, 297–304. [CrossRef]

- Min, K.-S.; Park, J.-J.; Byambaragchaa, M.; Kang, M.-H. Characterization of tethered equine chorionic gonadotropin and its deglycosylated mutants by ovulation stimulation in mice. BMC Biotechnol. 2019, 19, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Min, K.S.; Park, J.J.; Lee, Y.S.; Byambaragchaa, M.; Kang, M.H. Comparative gene expressing profiling of mouse ovaries upon stimulation with natural equine chorionic gonadotropin (N-eCG) and tethered recombinant-eCG (R-eCG). BMC Biotechnol. 2020, 20, 59. [CrossRef]

- Boeta, M.; Zarco, L. Luteogenic and luteotropic effects of eCG during pregnancy in the mare. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2012, 130, 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Conley, A. Review of the reproductive endocrinology of the pregnant and parturient mare. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 355–365. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Flores, G.; Velázquez-Cantón, E.; Boeta, M.; Zarco, L. Luteoprotective Role of Equine Chorionic Gonadotropin (eCG) During Pregnancy in the Mare. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2014, 49, 420–426. [CrossRef]

- de Mestre, A.; Bacon, S.; Costa, C.; Leadbeater, J.; Noronha, L.; Stewart, F.; Antczak, D. Modeling Trophoblast Differentiation using Equine Chorionic Girdle Vesicles. Placenta 2008, 29, 158–169. [CrossRef]

- E Read, J.; Cabrera-Sharp, V.; Offord, V.; Mirczuk, S.M.; Allen, S.P.; Fowkes, R.C.; de Mestre, A.M. Dynamic changes in gene expression and signalling during trophoblast development in the horse. Reproduction 2018, 156, 313–330. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.C.; Mussio, P.E.; Villarraza, J.; Tardivo, M.B.; Antuña, S.; Fontana, D.; Ceaglio, N.; Prieto, C. Physicochemical Characterization of a Recombinant eCG and Comparative Studies with PMSG Commercial Preparations. Protein J. 2023, 42, 24–36. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.E.; Meyers, M.A.; Palmer, J.; Veeramachaneni, D.N.R.; Magee, C.; de Mestre, A.M.; Antczak, D.F.; Hollinshead, F.K. Production of Mare Chorionic Girdle Organoids That Secrete Equine Chorionic Gonadotropin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9538. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.D.; Martinuk, S.D. Equine chorionic gonadotropin. Endocr. Rev. 1991, 12, 27–44. [CrossRef]

- Butnev, V.Y.; Gotschall, R.R.; Baker, V.L.; Moore, W.T.; Bousfield, G.R. Negative influence of O-linked oligosaccharides of high molecular weight equine chorionic gonadotropin on its luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor-binding activities.. Endocrinology 1996, 137, 2530–2542. [CrossRef]

- Fares, F. The role of O-linked and N-linked oligosaccharides on the structure–function of glycoprotein hormones: Development of agonists and antagonists. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 2006, 1760, 560–567. [CrossRef]

- Sugino, H.; Bousfield, G.R.; Moore, Jr.W.T.; Ward, D.N. Structural studies on equine gonadotropins: amino acid sequence of equine chorionic gonadotropin β-subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 8603–8609.

- Bousfield, G.R.; Sugino, H.; Ward, D.N. Demonstration of a COOH-terminal extension on equine lutropin by means of a common acid-labile bond in equine lutropin and equine chorionic gonadotropin.. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 9531–9533. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ispierto, I.; López-Helguera, I.; Martino, A.; López-Gatius, F. Reproductive Performance of Anoestrous High-Producing Dairy Cows Improved by Adding Equine Chorionic Gonadotrophin to a Progesterone-Based Oestrous Synchronizing Protocol. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2011, 47, 752–758. [CrossRef]

- Pacala, N.; Corin, N.; Bencsik, I.; Dronca, D.; Cean, A.; Boleman, A.; Caraba, V.; Papp, S. Stimulation of the reproductive function at cyclic cows by ovsynch and PRID/eCG. Anim. Sci. Biotech. 2010, 43, 317–320.

- Combarnous, Y.; Mariot, J.; Relav, L.; Nguyen, T.M.D.; Klett, D. Choice of protocol for the in vivo bioassay of equine Chorionic Gonadotropin (eCG / PMSG) in immature female rats. Theriogenology 2019, 130, 99–102. [CrossRef]

- Sim, B.-W.; Park, C.-W.; Kang, M.-H.; Min, K.-S. Abnormal gene expression in regular and aggregated somatic cell nuclear transfer placentas. BMC Biotechnol. 2017, 17, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Crispo, M.; Meikle, M.N.; Schlapp, G.; Menchaca, A. Ovarian superstimulatory response and embryo development using a new recombinant glycoprotein with eCG-like activity in mice. Theriogenology 2021, 164, 31–35. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Byambaragchaa, M.; Kang, H.J.; Choi, S.H.; Kang, M.H.; Min, K.S. Specific roles of N- and O-linked oligosaccharide sites on biological activity of equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG) in cells expressing rat luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor (LH/CGR) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSHR). BMC Biotechnol, 2021, 21, 52.

- Jazayeri, S.H.; Amiri-Yekta, A.; Gourabi, H.; Emami, B.A.; Halfinezhad, Z.; Abolghasemi, S.; Fatemi, N.; Daneshipour, A.; Ghahremani, M.H.; Sanati, M.H.; et al. Comparative Assessment on the Expression Level of Recombinant Human Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) in Serum-Containing Versus Protein-Free Culture Media. Mol. Biotechnol. 2017, 59, 490–498. [CrossRef]

- Thennati, R.; Singh, S.K.; Nage, N.; Patel, Y.; Bose, S.K.; Burade, V.; Ranbhor, R.S.; Limited, S.P.I.; Ovitrelle Analytical characterization of recombinant hCG and comparative studies with reference product. Biol. Targets Ther. 2018, ume 12, 23–35. [CrossRef]

- Doan, C.C., Le, T.L., Ho, N.Q.C., Hoang, N.S. Effects of ubiquitous chromatin opening element (UCOE) on recombinant anti-TNFalpha antibody production and expression stability in CHO-DG44 cells. Cytotechnology 2022, 74, 31–49. [CrossRef]

- Kazeto, Y.; Ito, R.; Tanaka, T.; Suzuki, H.; Ozaki, Y.; Okuzawa, K.; Gen, K. Establishment of cell-lines stably expressing recombinant Japanese eel follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone using CHO-DG44 cells: full induced ovarian development at different modes. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1201250. [CrossRef]

- Byambaragchaa, M.; Kim, S.-G.; Park, S.H.; Shin, M.G.; Kim, S.-K.; Kang, M.-H.; Min, K.-S. Production of Recombinant Single-Chain Eel Luteinizing Hormone and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Analogs in Chinese Hamster Ovary Suspension Cell Culture. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 542–556. [CrossRef]

- Byambaragchaa, M.; Park, S.H.; Kim, S.-G.; Shin, M.G.; Kim, S.-K.; Hur, S.-P.; Park, M.-H.; Kang, M.-H.; Min, K.-S. Stable Production of a Tethered Recombinant Eel Luteinizing Hormone Analog with High Potency in CHO DG44 Cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 6085–6099. [CrossRef]

- Byambaragchaa, M.; Park, S.H.; Kim, S.-G.; Shin, M.G.; Kim, S.-K.; Park, M.-H.; Kang, M.-H.; Min, K.-S. Stable Production of a Recombinant Single-Chain Eel Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Analog in CHO DG44 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7282. [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.Y. Inactivating mutations of G protein-coupled receptors and disease: Structure-function insights and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 111, 949–973. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-H.; Byambaragchaa, M.; Kim, D.-J.; Lee, J.-H.; Kang, M.-H.; Min, K.-S. Specific Signal Transduction of Constitutively Activating (D576G) and Inactivating (R476H) Mutants of Agonist-Stimulated Luteinizing Hormone Receptor in Eel. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9133. [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, K.; Ascoli, M. Lutropin/choriogonadotropin stimulate the proliferation of primary cultures of rat Leydig cells through a pathway that involves activation of the extracellularly regulated kinase 1/2 cascade. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 3214–3225. [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, K.; Ascoli, M. A co-coculture system reveals the involvement of intercellular pathways as mediators of the lutropin receptor (LHR)-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in Leydig cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 25–37. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Shenoy, S.K.; Wei, H.; Lefkowitz, R.J. Differential Kinetic and Spatial Patterns of β-Arrestin and G Protein-mediated ERK Activation by the Angiotensin II Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 35518–35525. [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.-R.; Reiter, E.; Ahn, S.; Kim, J.; Chen, W.; Lefkowitz, R.J. Different G protein-coupled receptor kinases govern G protein and β-arrestin-mediated signaling of V2 vasopressin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 1448–1453. [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, S.K.; Draka, M.K.; Nelson, C.D.; Houtz, D.A.; Xiao, K.; Madabushi, S.; Reiter, E.; Premont, R.T.; Lichtarge, O.; Lefkowitz, R.J. beta-arrestin-dependent, G protein-independent ERK1/2 activation by the beta2 adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 1261–1273.

- Shenoy, S.K.; Barak, L.S.; Xiao, K.; Ahn, S.; Berthouze, M.; Shukla, A.K.; Luttrell, L.M.; Lefkowitz, R.J. Ubiquitination of β-Arrestin Links Seven-transmembrane Receptor Endocytosis and ERK Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 29549–29562. [CrossRef]

- Slosky, L.M.; Bai, Y.; Toth, K.; Ray, C.; Rochelle, L.K.; Badea, A.; Chandrasekhar, R.; Pogorelov, V.M.; Abraham, D.M.; Atluri, N.; et al. β-Arrestin-Biased Allosteric Modulator of NTSR1 Selectively Attenuates Addictive Behaviors. Cell 2020, 181, 1364–1379.e14. [CrossRef]

- Kara, E.; Crépieux, P.; Gauthier, C.; Martinat, N.; Piketty, V.; Guillou, F.; Reiter, E. A Phosphorylation Cluster of Five Serine and Threonine Residues in the C-Terminus of the Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor Is Important for Desensitization But Not for β-Arrestin-Mediated ERK Activation. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 3014–3026. [CrossRef]

- Piketty, V.; Kara, E.; Guillou, F.; Reiter, E.; Crepieux, P. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation independently of beta-arrestin- and dynamin-mediated FSH receptor internalization. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2006, 4, 33–33. [CrossRef]

- Luttrell, L.M.; Wang, J.; Plouffe, B.; Smith, J.S.; Yamani, L.; Kaur, S.; Jean-Charles, P.-Y.; Gauthier, C.; Lee, M.-H.; Pani, B.; et al. Manifold roles of β-arrestins in GPCR signaling elucidated with siRNA and CRISPR/Cas9. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

- Flack, M.; Froehlich, J.; Bennet, A.; Anasti, J.; Nisula, B. Site-directed mutagenesis defines the individual roles of the glycosylation sites on follicle-stimulating hormone. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 14015–14020. [CrossRef]

- Saneyoshi, T.; Min, K.S.; Ma, J.X.; Nambo, Y.; Hiyama, T.; Tanaka, S.; Shiota, K. Equine follicle-stimulating hormone: molecular cloning of beta subunit and biological role of the asparagine-linked oligosaccharide at asparagine56 of alpha subunit. Biol. Reprod. 2001, 65, 1686–1690. [CrossRef]

- Villarraza, C.J.; Antuña, S.; Tardivo, M.B.; Rodríguez, M.C.; Mussio, P.; Cattaneo, L.; Fontana, D.; Díaz, P.U.; Ortega, H.H.; Tríbulo, A.; et al. Development of a suitable manufacturing process for production of a bioactive recombinant equine chorionic gonadotropin (reCG) in CHO-K1 cells. Theriogenology 2021, 172, 8–19. [CrossRef]

- Legardinier, S.; Cahoreau, C.; Klett, D.; Combarnous, Y. Involvement of equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG) carbohydrate side chains in its bioactivity; lessons from recombinant hormone expressed in insect cells. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 2005, 45, 255–259. [CrossRef]

- A Bishop, L.; Robertson, D.M.; Cahir, N.; Schofield, P.R. Specific roles for the asparagine-linked carbohydrate residues of recombinant human follicle stimulating hormone in receptor binding and signal transduction.. Mol. Endocrinol. 1994, 8, 722–731. [CrossRef]

- Matzuk, M.; Hsueh, A.J.W.; Lapolt, P.; Tsafriri, A.; Keene, J.L.; Boime, I. The biological role of the carboxyl-terminal extension of human chorionic gonadotropin β-subunit. Endocrinology 1990, 126, 376–383. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Bahl, O.P. Recombinant carbohydrate variant to human choriogonadotropin β-subunit (hCG β) decarboxyl terminus (115-145). J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 6246–6251.

- Byambaragchaa, M.; Kim, D.-J.; Kang, M.-H.; Min, K.-S. Site specificity of eel luteinizing hormone N-linked oligosaccharides in signal transduction. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2018, 268, 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Luttrell, L.M.; Roudabush, F.L.; Choy, E.W.; Miller, W.E.; Field, M.E.; Pierce, K.L.; Lefkowitz, R.J. Activation and targeting to extracellular signal-regulated kinases by beta-arrestin scaffolds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 2449–2454. [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Lynch, M.J.; Huston, E.; Beyermann, M.; Eichhorst, J.; Adams, D.R.; Klussmann, E.; Houslay, M.D.; Baillie, G.S. MEK1 Binds Directly to βArrestin1, Influencing Both Its Phosphorylation by ERK and the Timing of Its Isoprenaline-stimulated Internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 11425–11435. [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Coffa, S.; Fu, H.; Gurevich, V.V. How does arrestin assemble MAPKs into a signaling complex? J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 685–694.

- O’Hayre, M.; Eichel, K.; Avino, S.; Zhao, X.; Steffen, D.J.; Feng, X.; Kawakami, K.; Aoki, J.; Messer, K.; Sunahara, R.; Inoue, A.; von Zastrow, M.; Gutkind, J.S. Genetic evidence that β-arrestins are dispensable for the initiation of β2-adrenergic receptor signaling to ERK. Sci. Signal. 2017, 10(484). [CrossRef]

- Drube, J.; Haider, R.S.; Matthees, E.S.F.; Reichel, M.; Zeiner, J.; Fritzwanker, S.; Ziegler, C.; Barz, S.; Klement, L.; Filor, J.; et al. GPCR kinase knockout cells reveal the impact of individual GRKs on arrestin binding and GPCR regulation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 540. [CrossRef]

| Receptors | cAMP responses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Basala (nM / 10⁴ cells) |

EC₅₀b (ng/mL) |

Rmaxc (nM/10⁴ cells) |

|

| eLH/CGR | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 0.20 (1.0-fold) (0.16 to 0.27) d |

186.8 ± 3.1 (1.0-fold) |

| rLH/CGR | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 0.03 (6.6-fold) (0.02 to 0.03) |

85.5 ± 1.4 (0.46-fold) |

| rFSHR | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.10 (2.0-fold) (0.08 to 0.13) |

50.3 ± 0.9 (0.27-fold) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).