Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Anthelmintics, Vitamins and Minerals

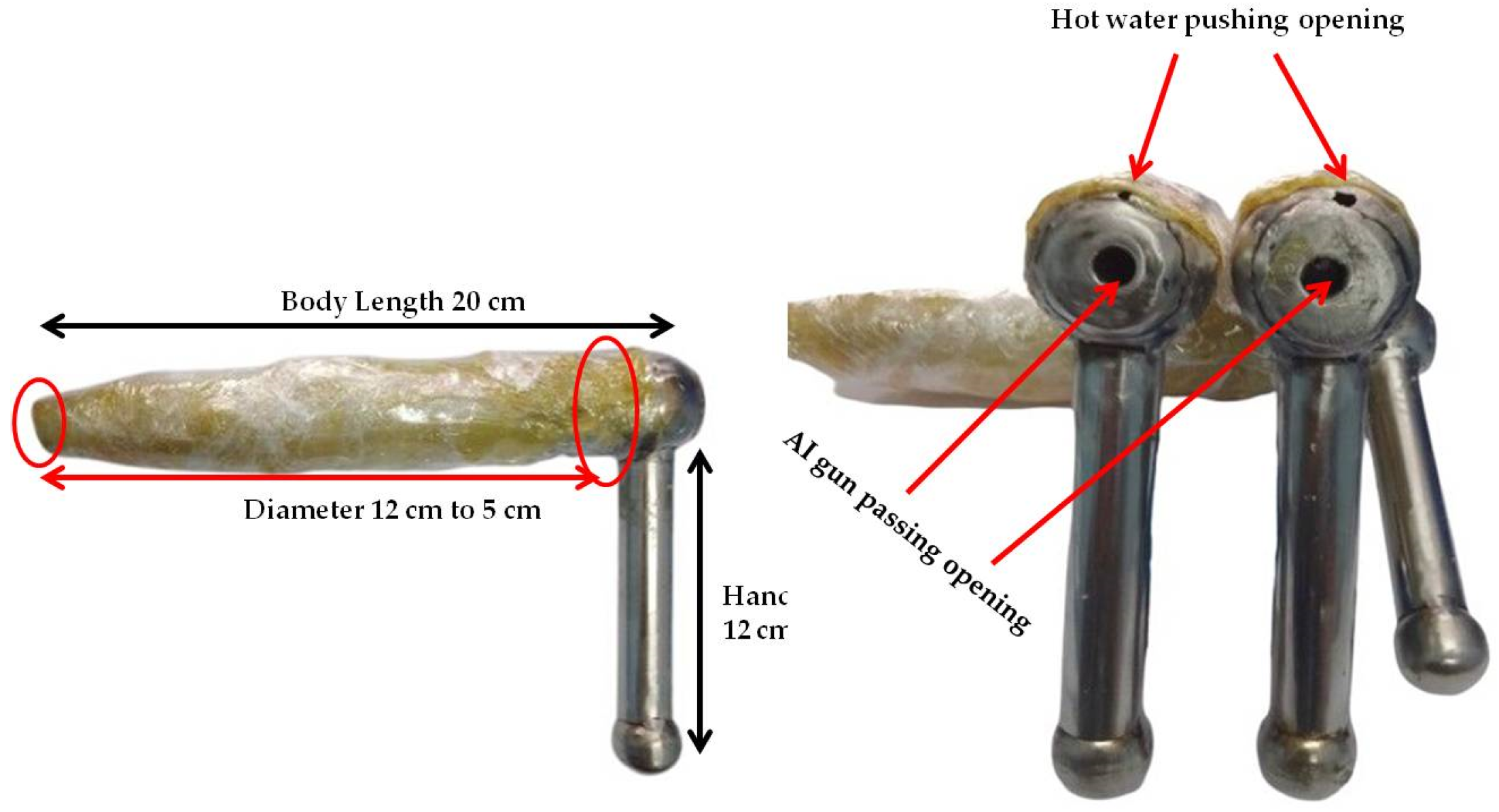

2.1.2. Modified Penis Like Device (mPLD)/Artificial Penis

2.1.3. Semen

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Study Area and Period

2.2.2. Selection and Management of Buffalo Heifers/Cows

2.2.3. Grouping of Animals

2.2.4. Use of mPLD/Artificial Penis

2.2.5. Experimental Design

2.2.6. Estrus Detection and Insemination

2.2.7. Pregnancy Diagnosis

2.2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

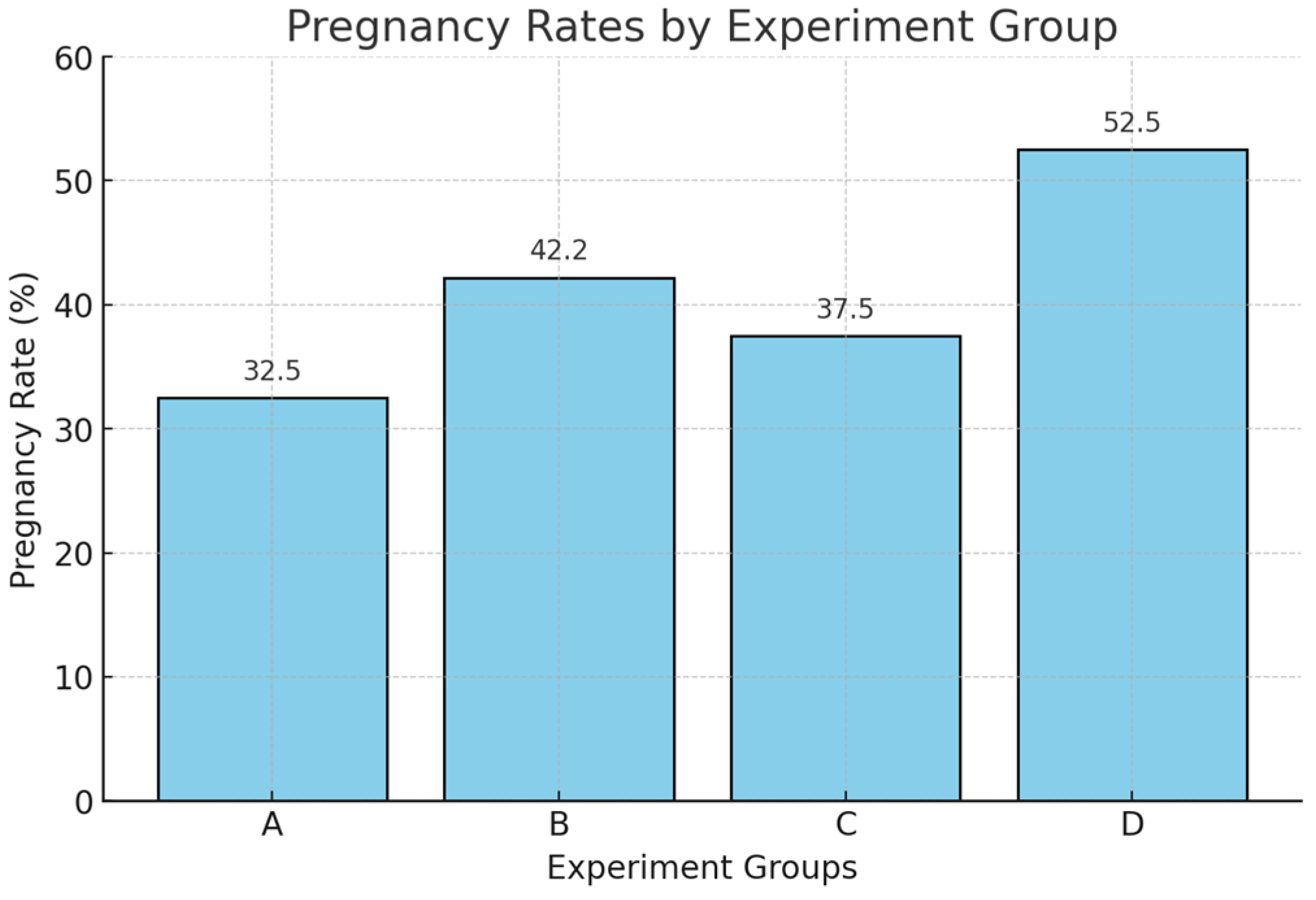

3.1. Pregnancy Rate in Different Intervention

3.2. Factors Influencing the Pregnancy Rate

3.2.1. Age of Animals

3.2.2. Parity of Cows

3.2.3. Body Weight

3.2.4. Reproductive Health

3.2.5. Calving Difficulties

3.2.6. Heat Detection Methods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DLS. Department of Livestock Services. Annual Report on Livestock; Division of Livestock Statistics, Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Faruque, M.O.; Hasnath, M.A.; Siddique, N.U. Present status of buffaloes and their productivity. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 1990, 3, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, I. Controlled Reproduction in Cattle and Buffaloes; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 1996; Volume 1, p. 452. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, S.; Swarna, M.; Paul, A.K. Improvement of bovine pregnancy rate through intra-vaginal bio-stimulation with penis-like device. Bangladesh J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2022, 57, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramiro, V.; Filho, O.; Cooke, R.F.; de Mello, G.A.; Pereira, V.M.; Vasconcelos, J.L.M.; Pohler, K.G. The effect of clitoral stimulation post artificial insemination on pregnancy rates of multiparous Bos indicus beef cows submitted to estradiol/progesterone-based estrus synchronization protocol. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warriach, H.M.; Ahmad, N. Follicular waves during the oestrus cycle in Nili-Ravi buffaloes undergoing spontaneous and PGF2α-induced luteolysis. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2008, 101, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenoweth, P.J. Sexual behavior of the bull: A review. J. Dairy Sci. 1983, 66, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, A.; Biswas, D.; Fakruzzaman, M.; Deb, G.K.; Hossain, S.M.J.; Alam, M.A.; Khandoker, M.A.M.Y.; Paul, A.K. Enhancement of the pregnancy rate of buffalo cows through intra-vaginal bio-stimulation with penis-like device in the coastal area of Bangladesh. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2024, 12, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, G.C. A Textbook of Animal Husbandry, 8th ed.; Oxford & IBH Publishing Company Pvt. Limited: New Delhi, India, 2010; p. 435. [Google Scholar]

- Wangchuk, K.; Wangdi, J.; Mindu, M. Comparison and reliability of techniques to estimate live cattle body weight. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2017, 46, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. SYSTAT 6.0 for Windows: Statistics; SPSS Inc: Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf, M.R.; Martins, J.P.N.; Husnaina, A.; Riaz, U.; Riaz, H.; Sattar, A. Effect of oestradiol benzoate on oestrus intensity and pregnancy rate in CIDR-treated anoestrus nulliparous and multiparous buffalo. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 159, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huque, K. A performance profile of dairying in Bangladesh—Programs, policies and way forwards. Bangladesh J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 43, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Kamboj, M.L.; Raheja, N.; Kumar, S.; Saini, M.; Lathwal, S.S. Influence of bull bio-stimulation on age at puberty and reproductive performance of Sahiwal heifers. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 90, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiol, C.; Ungerfeld, R. Positive effects of bio-stimulation on luteinizing hormone concentration and follicular development in anestrus beef heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.; Brown, H.; Patel, S.; Walker, R. The reproductive lifespan in cattle: A review. Anim. Sci. J. 2020, 91, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.A.; Ahmed, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Hossain, K.M. Status of buffalo production in Bangladesh compared to SAARC countries. Asian J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 10, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Hall, D. Influence of parity on fertility in dairy cows. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2017, 52, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, R.L.; Gokhale, S.B. Factors affecting pregnancy rate in cows under field condition. Indian J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 52, 298–302. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.; Miller, T.; Wilson, P.; Clark, E. Body condition and reproductive efficiency in livestock. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Johnson, P.; Ramirez, D.; Foster, K. Reproductive health management in livestock: Challenges and solutions. Theriogenology 2019, 128, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufti, M.M.R.; Alam, M.K.; Sarker, M.S.; Bostami, A.B.M.R.; Das, N.G. Study on factors affecting the conception rate in Red Chittagong cows. Bangladesh J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 39, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; Smith, J.; Evans, H.; Taylor, B. Impact of calving difficulties on subsequent fertility. Vet. J. 2016, 109, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Lopez, R.; Turner, K.; Martinez, L. Comparing heat detection methods in cattle: Teaser bulls vs manual observation. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 102, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Category (n) | Pregnancy rate % (n) | ꭓ2 & p value | Group wise Pregnancy rate n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | ||||

| Age (year) | ≤3 to 4 (32) |

43.75 (14) |

0.925 0.819 |

0 (0.0) |

5 (21.43) | 5 (35.71) | 6 (42.86) |

| 4.1 to 5 (42) |

45.24 (19) | 2 (10.53) | 5 (26.32) | 3 (15.79) | 9 (47.37) | ||

| 5 .1 to 6 (58) |

41.38 (24) | 6 (25.00) | 7 (29.17) | 6 (25.00) | 5 (20.83) | ||

| >6 to ≥7 (28) |

32.14 (9) | 5 (55.56) | 2 (22.22) | 1 (11.11) | 1 (11.11) | ||

| Parity (number) | P0 (36) | 47.22 (17) |

1.628 0.804 |

3 (17.65) | 10 (58.82) | 2 (11.76) | 2 (11.76) |

| P1 (32) | 40.63 (13) | 3 (23.08) | 3 (23.08) | 4 (30.77) | 3 (23.08) | ||

| P2 (58) | 37.93 (22) | 4 (18.18) | 2 (9.09) | 5 (22.73) | 11 (50.00) | ||

| P3 (24) | 50.00 (12) | 3 (25.00) | 1 (8,33) | 3 (25.00) | 5 (41.67) | ||

| ≥P4 (10) | 33.33 (2) | 0 (0.0) |

1 (50.00) | 1 (50.00) | 0 (0.0) |

||

| Body weight (kg) | ≤200 to 300 (48) |

33.33 (16) | 1.080 0.583 |

3 (18.75) | 4 (25.00) | 2 (12.50) | 7 (43.75) |

| 301 to 400 (83) |

45.78 (38) | 8 (21.05) | 11 (28.95) | 8 (21.05) | 11 (28.95) | ||

| >400 (29) |

41.38 (12) | 2 (16.67) | 2 (16.67) | 5 (41.67) | 3 (25.00) | ||

| Reproductive Health (RH) | Good (31) |

35.48 (11) | 2.279 0.320 |

3 (27.27) | 2 (18.18) | 5 (45.45) | 1 (9.09) |

| Moderate (123) |

43.90 (54) | 10 (18.52) | 14 (25.93) | 10 (18.52) | 20 (37.04) | ||

| Poor (6) |

16.67 (1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Calving Difficulties (CD) | Yes (5) | 20.00 (1) | 0.962 0.327 |

0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No (155) | 41.94 (65) | 13 (20.00) | 17 (26.15) | 14 (21.54) | 21 (32.31) | ||

| Heat detection | By farmer (147) |

39.46 (58) | 2.403 0.121 |

10 (17.24) | 14 (24.14) | 14 (24.14) | 20 (34.48) |

| By teaser bull (13) |

61.54 (8) | 3 (37.50) | 3 (37.50) | 1 (12.50) | 1 (12.50) | ||

| Factors | Variables | Coeficient | Std. Error |

Wald | Sig. | Odd ratio |

95% Confidence Interval for odd ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| Age | ≤3 to 4 | - | - | 1.648 | 0.649 | - | - | - |

| 4.1 to 5 | -0.271 | 0.520 | 0.271 | 0.603 | 0.763 | 0.309 | 2.626 | |

| 5 .1 to 6 | -0.331 | 0.464 | 0.510 | 0.475 | 0.718 | 0.323 | 2.104 | |

| >6 to ≥7 | 0.301 | 0.530 | 0.322 | 0.571 | 1.351 | 0.488 | 4.145 | |

| Parity | P0 | - | - | 3.028 | 0.553 | - | - | - |

| P1 | -1.110 | 0.977 | 1.292 | 0.256 | 0.330 | 0.050 | 2.306 | |

| P2 | -0.718 | 1.006 | 0.510 | 0.475 | 0.488 | 0.071 | 3.757 | |

| P3 | -0.435 | 0.938 | 0.215 | 0.643 | 0.647 | 0.127 | 5.458 | |

| P4 | -0.950 | 0.995 | 0.912 | 0.340 | 0.387 | 0.063 | 3.367 | |

| Body weight | ≤200 to 300 | - | - | 2.195 | .334 | - | - | |

| 301 to 400 | 0.342 | 0.560 | 0.373 | .541 | 1.407 | 0.487 | 4.894 | |

| >400 | -0.280 | 0.514 | 0.297 | .586 | 0.756 | 0.282 | 2.238 | |

| Reproductive Health | Good | - | - | 2.551 | .279 | . | . | |

| Moderate | -1.087 | 1.249 | 0.757 | 0.384 | 0.337 | 0.032 | 4.533 | |

| Poor | -1.531 | 1.154 | 1.761 | 0.184 | 0.216 | 0.028 | 2.684 | |

| Calving Difficulties | Yes | - | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| No | 1.482 | 1.186 | 1.561 | 0.212 | 4.400 | 0.390 | 42.267 | |

| Heat detection | By farmer | - | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| By teaser bull | 1.394 | 0.701 | 3.951 | 0.047 | 4.032 | 1.109 | 18.798 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).