Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Introduction: Integrating generative AI into medical education addresses challenges in developing clinical cases for case-based learning (CBL), a method that enhances critical thinking and learner engagement through realistic scenarios. Traditional CBL is resource-intensive and less scalable. Generative AI can produce realistic text and adapt to learning needs, offering promising solutions. This scoping review maps existing literature on generative AI's use in creating clinical cases for CBL and identifies research gaps. Methods: This review follows Arksey and O'Malley’s (2005) framework, enhanced by Levac et al. (2010), and aligns with PRISMA-ScR guidelines. A systematic search will occur across major databases like PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, ERIC, and CINAHL, along with gray literature. Inclusion criteria focus on studies published in English between 2014 and 2024, examining generative AI in case-based learning (CBL) in medical education. Two independent reviewers will screen and extract data, iteratively charted using a standardized tool. Data will be summarized narratively and thematically to identify trends, challenges, and gaps. Results: The review will present a comprehensive synthesis of current applications of generative AI in CBL, focusing on the types of models utilized, educational outcomes, and learner perceptions. Key challenges, including ethical and technical barriers, will be emphasized. The findings will also outline future directions and recommendations for integrating generative AI into medical education. Discussion: This review will enhance understanding of generative AI's role in improving CBL by addressing resource constraints and scalability challenges while maintaining pedagogical integrity. The findings will guide educators, policymakers, and researchers on best practices, emerging opportunities, and areas needing further exploration. Conclusion: Generative AI has significant potential to revolutionize competency-based learning (CBL) in medical education. By mapping current evidence, this review will offer valuable insights into its potential applications, effectiveness, and challenges, paving the way for innovative and adaptive educational strategies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

- Substantial clinical content.

- Contributions from multiple subject matter experts.

- Significant time to develop and provide personalized feedback (Sultana et al., 2024).

1.2. Research Objectives

- Identify the types of generative AI models used (e.g., ChatGPT and Gemini) and their specific roles in developing clinical cases.

- Explore the educational contexts in which these models are applied, including undergraduate education, postgraduate training, and continuing professional development.

-

Investigate the reported impact of generative AI-assisted CBL on learner outcomes, such as:

- ○

- Clinical reasoning.

- ○

- Knowledge acquisition.

- ○

- Problem-solving and decision-making skills.

- ○

- Learner engagement and satisfaction.

- Analyze perceptions, experiences, and feedback from learners and educators regarding the use of generative AI in CBL.

- Identify factors influencing AI-generated clinical cases' acceptance, usability, and trustworthiness.

- Highlight technical, pedagogical, and logistical barriers to implementing generative AI in CBL.

- Explore ethical concerns, including data bias, accuracy, academic integrity, and professional development implications.

- ●

- Identify gaps in the existing body of literature related to the role of generative AI in CBL.

- ●

- Suggest areas for further investigation, including:

- ○

- Enhancing the scalability and adaptability of AI-generated clinical cases.

- ○

- Developing guidelines for ethical and effective integration of generative AI into medical curricula.

- Provide evidence-based recommendations for stakeholders, including educators, administrators, and policymakers, to guide the integration of generative AI technologies into health professions education.

2. Methodology

2.1. Scoping Review Framework

- Stage 1: Identifying the research questions (outlined below)

- Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies (search strategy and databases)

- Stage 3: Study selection (eligibility criteria)

- Stage 4: Charting the data (organization of findings)

- Stage 5: Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

- Stage 6 (optional): Consultation with relevant stakeholders

2.2. Identifying the Research Questions

- What generative AI applications (such as ChatGPT-4 and ChatGPT-3) currently exist for the development of clinical cases?

- Does this technology have a clear and established role in enhancing the educational outcomes of learners?

- Are there any reported learner perceptions associated with using generative AI to solve cases in medical education?

- What ethical concerns and technical barriers might arise when implementing AI for CBL?

- What gaps are identified in the current literature on the role of generative AI in CBL, and what future policies, directions, and research are needed?

2.3. Search Strategy

- PubMed/MEDLINE

- Scopus

- Web of Science

- EMBASE

- ERIC

- CINAHL

- Cochrane Library

- Google Scholar (to capture gray literature)

- "Generative AI"

- "Large Language Model"

- "ChatGPT"

- "Case-Based Learning"

- "Medical Education"

- "Clinical Cases"

-

Inclusion Criteria:

- ○

- Articles published in English between 2014 and 2024.

- ○

- Peer-reviewed primary studies (e.g., observational, qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods) and secondary studies (e.g., systematic reviews, meta-analyses).

- ○

- Studies focused on generative AI applications in developing clinical cases for CBL in medical education.

- ○

- Studies involving health professions students or practicing healthcare professionals.

-

Exclusion Criteria:

- ○

- Articles not related to generative AI or medical education.

- ○

- Studies focusing exclusively on non-generative AI.

- ○

- Publications in languages other than English.

2.4. Study Selection

| Criterion | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

| Study design | Primary research studies (observational cohort, quantitative and qualitative studies, mixed-methods, random clinical trials) and secondary study types (systematic reviews, meta-analyses, conference proceedings/abstracts, dissertation and theses) |

Editorials, opinions, commentaries (articles lacking original data) |

| Population | Healthcare professionals (e.g. medical doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals) and health professions students in training (undergraduate, postgraduate education and continuing professional development) |

Professionals not engaged in the healthcare field (e.g finance, business and art) or students pursuing undergradaute and postgraduate degrees not related to health disciplines |

|

Focus of study (intervention) |

Studies specifically discussing the use, application and impact of generative AI in developing cases in CBL framework in medical education or training | Studies focusing on non-generative AI usage in relation to CBL application, implementation and impact in medical education |

| Outcomes | Changes in learners’ perceptions or documented alterations in their clinical reasoning abilities, engagement, knowledge acquisition, problem-solving and decision-making skills or any progression outcomes |

No changes in learners’ perceptions or documented alterations in their clinical reasoning, engagement, knowledge acquisition, problem-solving and decision-making skills or no indicator on progression outcomes |

| Language | Articles published in the English language | Articles published in languages other than English (Unless translation is permittable) |

| Publication date | Articles published in the last 10 years (2014 – present) | Articles published before 2014 |

2.5. Charting of Data

- Study Characteristics: Study ID, year of publication, country of origin, journal name, author(s), study title, study design, sample size, educational context (e.g., academic, clinical), and study duration.

- Population Details: Demographic information (e.g., age, gender), type of participants (e.g., students, healthcare professionals), and level of training (e.g., undergraduate, postgraduate, or continuing professional development).

- Generative AI Model Characteristics: Specific models used (e.g., ChatGPT or Gemini), language and platform utilized, topic or focus of case-based learning (CBL), learning objectives of the clinical cases, and the duration and frequency of the clinical cases.

- Educational Outcomes: Reported outcomes for learners, including clinical reasoning, knowledge retention, problem-solving skills, and learner engagement. Evaluation metrics (e.g., surveys, tests) and time points of measurements will also be recorded.

- Key Findings: Main results related to generative AI applications, any statistical analysis conducted, and thematic findings (if applicable).

- Challenges and Limitations: Ethical concerns, technical barriers, and pedagogical limitations identified by the authors.

- Future Directions: Recommendations for future research, implications for clinical practice, and gaps or suggestions proposed by the authors.

2.6. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

2.7. Consultation with Stakeholders (Optional stage)

3. Dissemination Plans

3.1. Ethics

3.2. Dissemination Plans

- Academic Publications: The scoping review will be submitted to a high-impact, peer-reviewed journal focused on medical education or educational technology to ensure wide dissemination among researchers and educators. Supplemental materials, including thematic maps and data visualizations, will enhance the accessibility and interpretability of the findings.

- Conference Presentations: The results will be presented at major international and regional conferences, such as AMEE (Association for Medical Education in Europe), Ottawa Conference, or local symposia on health professions education. These presentations will include both oral sessions and interactive workshops to engage diverse stakeholders.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Briefings and summaries of the findings will be prepared for key stakeholders, including educators, administrators, policymakers, and AI experts. Tailored recommendations will be provided to guide decision-making regarding the integration of generative AI into medical curricula.

- Social Media Outreach: Key findings will be shared through professional social media platforms, such as LinkedIn, to reach a global audience of medical educators and technology enthusiasts. Short, visually engaging posts with infographics and highlights will be designed to encourage broader discussion and knowledge sharing.

- Collaborative Knowledge Translation: Partnerships will be sought with organizations and institutions in medical education to develop practical guidelines or training modules based on the review findings. Workshops and webinars will be organized to facilitate the translation of evidence into actionable practices.

- Local and Regional Dissemination: Efforts will be made to disseminate the findings within the MENA region, leveraging local networks and forums to promote the relevance of generative AI applications in regional educational contexts. Multilingual summaries may be created to address language diversity in the region.

- Public Engagement: Accessible summaries of the findings will be shared with the broader public through blogs, podcasts, or media interviews to foster awareness of the potential of generative AI in improving medical education outcomes.

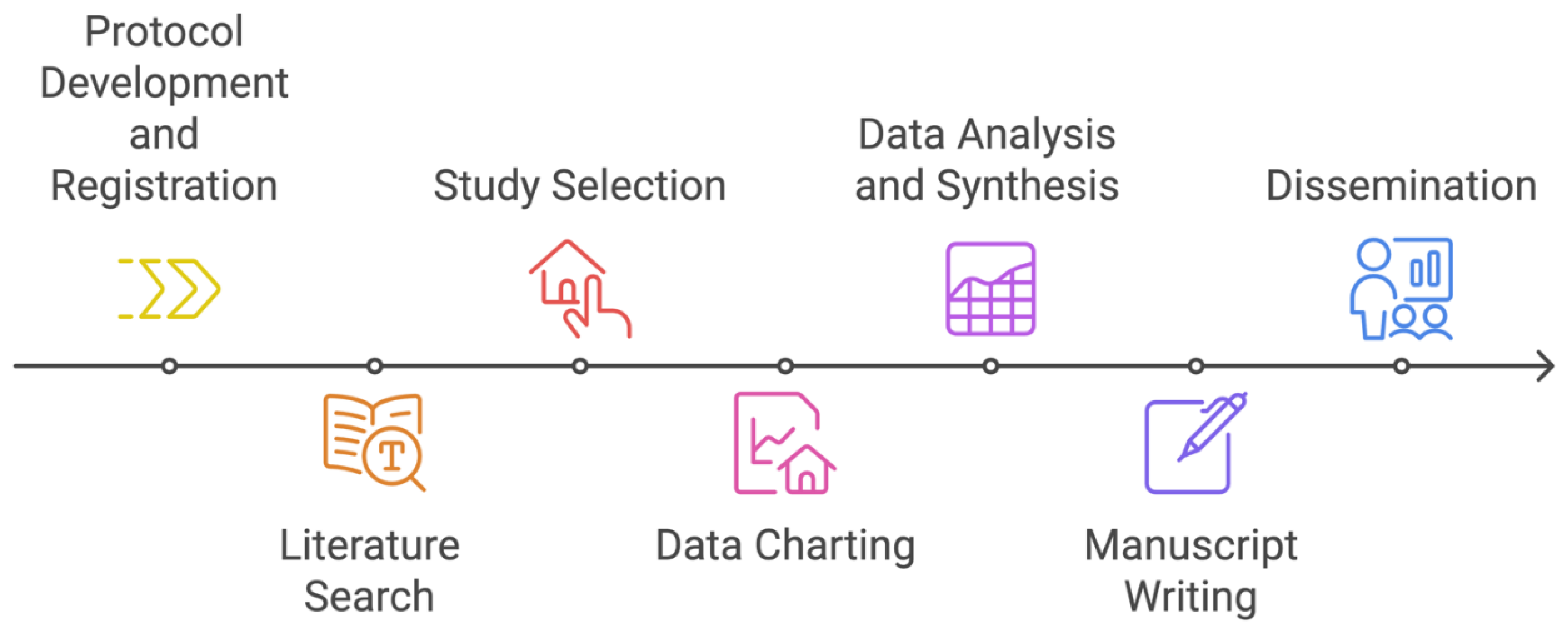

3.3. Timeline

- Protocol Development and Registration: 5 weeks (Weeks 1-5)

- Literature Search: 4 weeks (Weeks 6-9)

- Study Selection: 6 weeks (Weeks 10-15)

- Data Charting: 4 weeks (Weeks 16-19)

- Data Analysis and Synthesis: 8 weeks (Weeks 20-27)

- Manuscript Writing: 6 weeks (Weeks 28-33)

- Dissemination: 8 weeks (Weeks 34-41)

3.4. Limitations

3.5. Implications for Future Research

Appendix A. Draft of Initial Search Strategy in Some Databases

| Database |

Query *(AND) |

Date limitation |

Langauge restriction |

Publication type |

| PubMed | ("Generative AI"[MeSH] OR "Generative Artificial Intelligence"[MeSH] OR "Large Languge Model"[MeSH]) OR "CHATGPT"[MeSH]) OR ("Clinical Case"[MeSH] OR "Case-Based Learning"[MeSH]) OR ("Medical Education"[MeSH]) OR ("Medical Training"[MeSH]) | AND ("2014/01/01"[publication date] |

AND English [language] | AND (Journal Article[publication type] OR Review[publication type]) |

| Scopus | ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( generative AND ai ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( chatgpt ) OR ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( lange AND language AND model ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( clinical AND case ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( medical AND education ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( case AND based AND learning ) | AND PUBYEAR > 2014 |

AND (LIMITTO( LANGAUGE, "English")) |

AND (LIMITTO( DOCTYPE, "ar") OR LIMITTO( DOCTYPE, "re")) |

| EMBASE | ('generative ai'/exp OR 'generative ai' OR (generative AND ai) OR 'clinical case':ab,ti) OR (chatgpt:ab,ti) OR 'medical education':ab,ti) OR medical learning:ab,ti) OR ('case AND based AND learning:ab,ti) OR (healthcare AND training:ab,ti) | AND [2014-2024]/py | AND [english]/lim | AND ([article]/lim OR [review]/lim) |

| CINAHL | ("Generative AI" OR "Chatgpt" OR "AI") OR ("Clinical Case" OR "Case-Based Learning" OR "CBL") OR ("Medical Education") OR ("Deep Learning") OR ("clinical training") OR ("health education") | AND ("2014/01/01"[publication date] |

AND LA "English" |

AND (PT "Journal Article" OR PT "Review") |

Appendix B. Preliminary Data Charting Form

- ▪

- Reviewer name:

- ▪

- Date of review:

- ▪

- Additional notes or comments:

| Study characteristics | Study ID |

| Year of publication | |

| Country of origin | |

| Journal name | |

| Author(s) | |

| Study title | |

| Study design | |

| Sample size | |

| Educational context (e.g. academic, clinical) | |

| Study duration | |

| Population details | Demographic data (age, gender, etc..) |

| Type of participants (students, healthcare professionals) | |

| Level of training (undergraduate, postgraduate or continuing professional development) | |

| Generative AI models (intervention) characteristics | Specific models used (e.g. ChatGPT-4 or ChatGPT-3) |

| Language used | |

| Platform utilized (if any) | |

| Topic/focus of CBL | |

| Learning objectives of the clinical cases | |

| Duration and frequency of the clinical cases | |

| Educational outcomes | Outcomes for students (e.g. learner engagement, knowledge retention, clinical reasoning, and problem-solving) |

| Evaluation metrics (self-reported surveys or any other measurement tool) | |

| Time-points of measurements | |

| Relevant key findings | Main reported results related to the intervention |

| Any statistical analysis reported | |

| Thematic analysis (if any) | |

| Challenges and limitations (reported by authors) | Ethical concerns |

| Technical barriers | |

| Pedagogical limitations | |

| Future implications (proposed by authors) | Recommendations for future research |

| Implications for clinical practice | |

| Any identified gaps and suggestions |

References

- Arksey, H., and L. O'Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8, 1: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbenyuk, A., L. Powell, and N. Zary. 2024. Feasibility and Educational Value of Clinical Cases Generated Using Large Language Models. Stud Health Technol Inform 316: 1524–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, M. A. C., A. Miles, and J. E. Asbridge. 2024. Modern medical schools curricula: Necessary innovations and priorities for change. J Eval Clin Pract 30, 2: 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, J., S. Alexander, S. T. Wright, and K. Gilliland. 2024. Generative AI in Undergraduate Medical Education: A Rapid Review. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development 11: 23821205241266697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, H., S. J. Griffin, I. Kuhn, and J. A. Usher-Smith. 2020. Software tools to support title and abstract screening for systematic reviews in healthcare: an evaluation. BMC Med Res Methodol 20, 1: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jowsey, T., J. Stokes-Parish, R. Singleton, and M. Todorovic. 2023. Medical education empowered by generative artificial intelligence large language models. Trends Mol Med 29, 12: 971–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G., J. Rehncy, K. S. Kahal, J. Singh, V. Sharma, P. S. Matreja, and H. Grewal. 2020. Case-Based Learning as an Effective Tool in Teaching Pharmacology to Undergraduate Medical Students in a Large Group Setting. J Med Educ Curric Dev 7: 2382120520920640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D., H. Colquhoun, and K. K. O'Brien. 2010. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 5: 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, J., M. Sampson, D. M. Salzwedel, E. Cogo, V. Foerster, and C. Lefebvre. 2016. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. In J Clin Epidemiol. vol. 75, pp. 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, S. F. 2016. Case-Based Learning and its Application in Medical and Health-Care Fields: A Review of Worldwide Literature. J Med Educ Curric Dev 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M. D., C. M. Godfrey, H. Khalil, P. McInerney, D. Parker, and C. B. Soares. 2015. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 13, 3: 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preiksaitis, C., and C. Rose. 2023. Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Scoping Review. JMIR Med Educ 9: e48785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, T. S., R. M. Gite, D. A. Tawde, C. Jena, K. Khatoon, and M. Kapoor. 2024. Advancing Healthcare Education: A Comprehensive Review of Case-based Learning. Indian Journal of Continuing Nursing Education 25, 1: 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thistlethwaite, J. E., D. Davies, S. Ekeocha, J. M. Kidd, C. MacDougall, P. Matthews, J. Purkis, and D. Clay. 2012. The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 23. Med Teach 34, 6: e421–e444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A. C., E. Lillie, W. Zarin, K. K. O'Brien, H. Colquhoun, D. Levac, D. Moher, M. D. J. Peters, T. Horsley, L. Weeks, S. Hempel, E. A. Akl, C. Chang, J. McGowan, L. Stewart, L. Hartling, A. Aldcroft, M. G. Wilson, C. Garritty, and S. E. Straus. 2018. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 169, 7: 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).