1. Introduction

Peritonitis is one of most common surgical patologies with a significant impact on human health. It is a condition that occurs in the peritoneal cavity and is characterized by localized or generalized inflammation of the peritoneum. The cause can be bacterial, fungal, or chemical. We distinguish: primary peritonitis, secondary peritonitis, and tertiary peritonitis.

- -

Primary peritonitis, or spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, is a spontaneous bacterial infection of the peritoneal cavity that occurs most often in the first years of life in children and in adult patients with low immunity or liver cirrhosis.

- -

Secondary peritonitis is represented by the secondary inflammation of the peritoneum due to injuries to the intraperitoneal organs, either their perforation, necrosis, or inflammation.

- -

Tertiary peritonitis is a pathology with a slightly more blurred definition and is evidenced by persistent peritoneal inflammation after a secondary peritonitis has already been treated surgically, and persist for more than 48 hours, either because of the virulence and antibiotic resistance of the microorganisms incriminated or because of the immunocompromised host [

1].

Peritonitis can also be classified as localized or generalized. In this article, we will focus on secundary peritonitis, given the higher incidence in surgical department and almost absolute surgical indication. The incidence of secondary peritonitis is difficult to assess given the variety of pathologies that determine it. According to some studies, secondary peritonitis represents about 1% of all presentations in the emergency department of the hospital and is the second cause of sepsis in patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit. Among the first statistical data on the treatment of peritonitis were available starting with the end of the 19th century (Mikulicz-1889, Kronlein-1885, Körte 1892). One of the first scientists to obtain a decrease in postoperative mortality in peritonitis was Kirschner, from 80-100% to about 60% in 1926 [

2]. The surgical management of patients with secondary peritonitis has not changed much since the advent of surgery in the contemporary era and is still highly complex and represents a challenge for doctors. The goal is to eliminate the septic focus, the necrotic tissues, intensive washing of the peritoneal cavity, and adequate drainage of the surgical site. Even though we have a lot of new medical imaging and laboratory technologies and a variety of antibiotics available, mortality remains quite high nowadays, especially in those who develop severe sepsis, at approximately 35–55% [

3]. Certainly one of the implications of the unfavorable evolution of secondary peritonitis are the risk factors associated with the patient. The etiology, prevalence and impact of acute surgical abdomen caused by generalized peritonitis is quite varied, many of the patients are past their 6th decade of life, with associated concomitant pathologies and poor conditions [

4]. In this review, we will try to find and discuss the prognostic factors and highlight the most important of them.

2. Matherial and Methods

This article was made with the aim of analyzing the relevant current knowledge regarding the prognostic factors that modify morbidity and mortality in generalized secondary peritonitis. We used the databases PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Medline to perform a detailed search using key words that included: peritonitis, prognostic, mortality, morbidity, abdominal sepsis, artificial intelligence. The search was limited to articles in English language released between 2000 and 2024. A few older articles have been accepted to help us with valuable general information. However, we still relied on articles from the last 10 years.

3. Results

A total of 145 articles were identified potentially relevant. After reading the title, 93 were included. After reading the summary, 61 remained. In the next step, these 61 articles were analyzed in detail. In the end, the 40 most relevant articles from our point of view were selected that addressed prognostic factors in generalized secondary peritonitis and helped us carry out this review article. We tried to identify the currently known prognostic factors, to find out how they are applied in current practice and what are the future directions.

4. Discussion

Secondary peritonitis is a common surgical emergency that poses a life-threatening condition with high rates of mortality and morbidity. Prompt source control, combined with antibiotic therapy, modern intensive care, and sepsis treatment, plays a crucial role in determining the outcome [

5]. While intra-abdominal sepsis can affect individuals of all ages, it has a more significant impact on the elderly compared to younger patients. The signs and symptoms are typically characteristic of an acute abdomen, allowing for a rapid clinical diagnosis of peritonitis in most cases. However, many patients present to the hospital late, with already established generalized peritonitis, purulent contamination, and varying degrees of septicemia. A reduced physiological reserve, along with existing systemic illnesses, leads to poorer outcomes, especially in the elderly, immunosuppressed individuals, and those with serious comorbid conditions [

6].

Figure 1.

Peritonitis due to perforation of the jejunum (Source: Emergency Clinical Hospital “Sf Apostol Andrei” Galaţi, Surgical Clinic. The patient gave her consent to use her personal data and photos by signing the hospitalization form).

Figure 1.

Peritonitis due to perforation of the jejunum (Source: Emergency Clinical Hospital “Sf Apostol Andrei” Galaţi, Surgical Clinic. The patient gave her consent to use her personal data and photos by signing the hospitalization form).

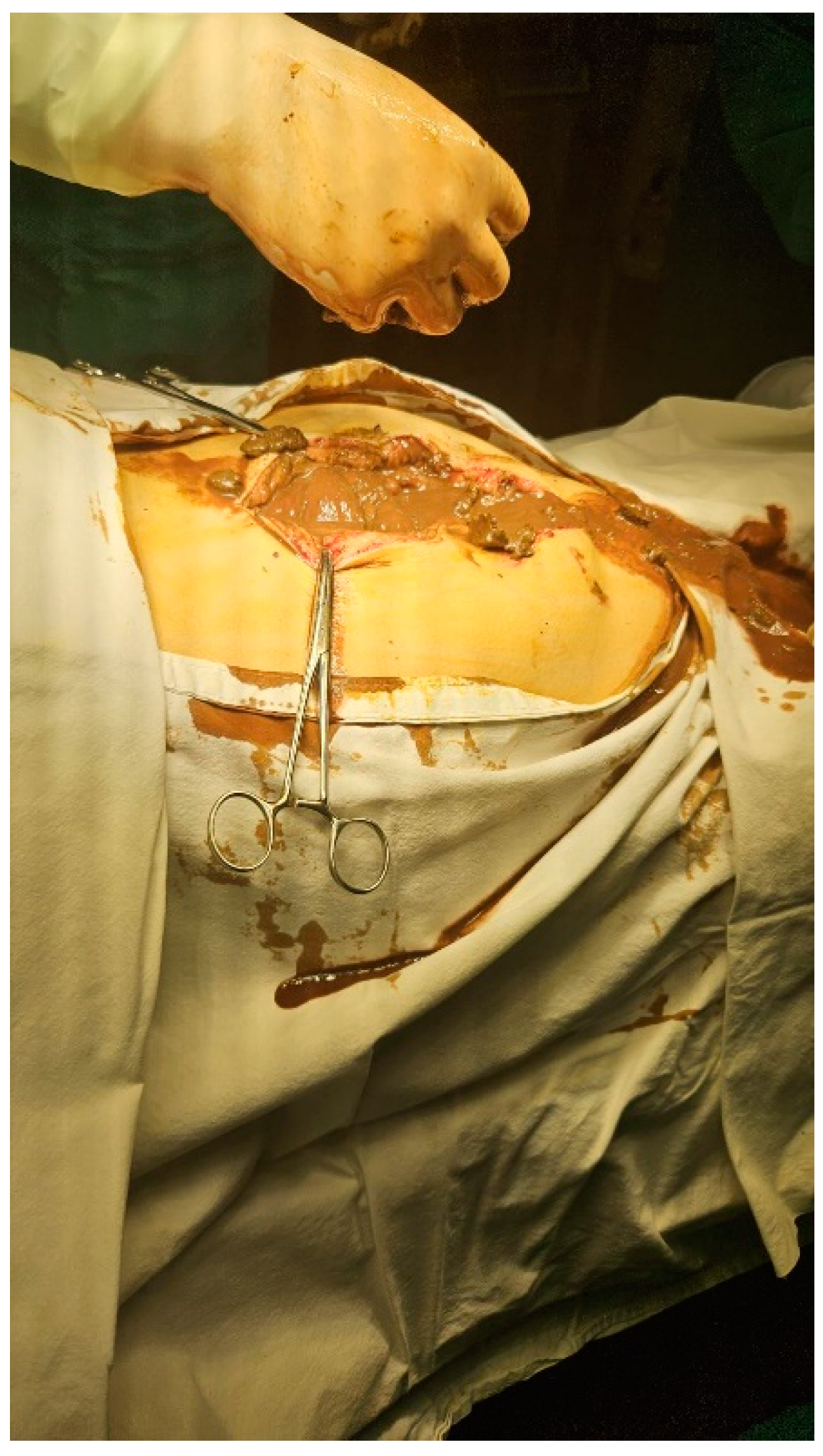

Figure 2.

Peritonitis due to perforation of the colon (Source: Emergency Clinical Hospital “Sf Apostol Andrei” Galaţi, Surgical Clinic. The patient gave her consent to use her personal data and photos by signing the hospitalization form).

Figure 2.

Peritonitis due to perforation of the colon (Source: Emergency Clinical Hospital “Sf Apostol Andrei” Galaţi, Surgical Clinic. The patient gave her consent to use her personal data and photos by signing the hospitalization form).

4.1. Age

Age is one of the most frequently used statistical indicators in medical specialty research. The aging process definitely brings metabolic, functional and structural changes to the tissues. This amplifies the action of aggression factors on the elderly patient. In developed countries, patients over the age of 60 constitute an important part of the population, so this criterion must be taken into account, being a challenge for case management. The study of Alessandro Neri concluded that at univariate analysis “Age older than 80 years old resulted significantly associated to increased risk of mortality”. Also variables that were statistically significant were analysed in a logistic regression: “age over 80 years resulted independent predictors of mortality at multivariate analysis” [

7]. The same result in the multivariate analysis and another study on 104 patients which confirms that age over 80 years is an independent predictor [

8]. Another important study on 11,202 patients with peritonitis shows us that advanced age is independently associated with severe sepsis in multivariate analysis [

9]. An important part of studies by other authors concludes that age is an important prognostic factor in secondary periodontitis and different age levels of 60 or 70 years were identified in the univariate analysis as important predictors of a poorer prognosis. But this value is often lost in multivariate analysis [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Another study, however, indicates that age did not have a significant impact on morbidity. The influence of age on outcomes is likely due to the presence of comorbidities and reduced physiological reserves associated with advanced age [

14].

Age was found to be an independent factor linked to shock and mortality in patients with peritonitis. It is known that both the incidence of septic shock and mortality rates rise with age, irrespective of the infection source [

15]. The changes in innate and acquired immunity among older adults are well documented: reduced phagocytosis and chemotaxis of polymorphonuclear cells, along with decreased activity of natural killer cells, may partly explain the increased susceptibility to infections in this age group. Additionally, poor nutritional status and diminished physiological reserves commonly seen in elderly patients may also play a role [

16,

17].

4.2. Comorbidities

Diffuse peritonitis is a condition associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The mortality rate within 30 days ranges from 15 % to 20 %, and this rate is notably influenced by the presence of serious comorbid condition [

18,

19,

20]. The overall health of the patient is crucial for predicting their future outcome. To assess prognosis, various scoring systems have been created, but these systems can be quite complex due to the many parameters they involve [

21,

22]. Surgeons need to quickly gauge the risk of a severe or fatal outcome either before or during surgery, but they often face time constraints that make it impractical to use these intricate scoring systems. Consequently, the patient’s prognosis frequently influences the decisions made during the surgical procedure.

The most commonly reported comorbidities that considerably worsen patient prognosis include cancer, preoperative organ failure, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular conditions, and diabetes mellitus [

18,

23,

24].

Petr Špička in his study published in 2022 on a number of 274 patients diagnosed with diffuse peritonitis found that having two or more severe comorbidities is a major negative prognostic factor that significantly increases both mortality and morbidity. In his cohort, 61% of patients with diffuse peritonitis had two or more severe comorbidities, which aligns with the patients' age distribution. It is obvious that older individuals and those with multiple health conditions are more susceptible to peritonitis. He concluded that cardiovascular disease, cancer, hypertension, and having two or more severe comorbidities significantly increase both mortality and morbidity rates, consistent with recent research. In his study cohort, pulmonary disease was found to impact the mortality rate but did not affect the morbidity rate [

25].

Tolonen in his multivariate logistic regression analysis identified the severity of sepsis, chronic renal failure, and preexisting cardiovascular disease as independent predictors of 30-day mortality or the need for ICU admission. Additionally, the use of corticosteroids, presence of metastatic malignant disease or lymphoma, and sepsis severity were found to be independent risk factors [

18].

In a 2013 study, Parwez Sajad Khan concluded that the presence of comorbidities significantly impacted both morbidity and mortality in his series: “

58.5% of the patients with co morbidity developed complications and 39% died. In comparison, only 18.6% developed complications and only 1.6% died of the patients who had no co-morbid condition” [

14].

The impact of comorbidities on outcomes is well supported by other researchers [

26,

27,

28].

4.3. The Mannheim Peritonitis Index (MPI)

Various scoring systems are employed to predict the outcomes in patients with peritonitis. These systems serve as valuable tools for forecasting the prognosis and prioritizing treatment to enhance patient care in cases of peritonitis. One of the most famous and important scores for perforating peritonitis is the Mannheim Peritonitis Index (MPI). It was developed by Linder et al. in 1987 based on clinical observations and risk factors from 1,243 patients with purulent peritonitis to predict mortality in cases of perforation peritonitis [

29]. The scoring system includes eight factors, covering demographic, physiological, and disease-specific elements, with a maximum score of 47. In the original study, using a cutoff value of >26, the MPI demonstrated good sensitivity (84%), specificity (79%), and overall accuracy (81%) in identifying patients at higher risk of mortality

Table 1.

Mannheim Peritonitis Index (MPI).

Table 1.

Mannheim Peritonitis Index (MPI).

| Riskfactor |

Score |

| Age >50 years |

5 |

| Female sex |

5 |

| Organ failure |

7 |

| Malignancy |

4 |

| Preoperative duration of peritonitis > 24h |

4 |

| Origin of sepsis non colonic |

4 |

| Diffuse generalized peritonitis |

6 |

| Exudate |

|

| Clear |

0 |

| Cloudy, purulent |

6 |

| Fecal |

12 |

| Definitions of organ failure |

|

| Kidney |

Creatinine level> 177 umol/L

Urea level> 167 mmol/L

Oliguria< 20ml/h |

| Lung |

PO2< 50 mmHg

PCO2 > 50 mmHg |

| Shock |

Hypodynamic or Hyperdynamic |

Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of the MPI as an independent prognostic scoring system for predicting outcomes in secondary peritonitis. We have compared a few of these studies (

Table 2).

Pathak et al., in their recent study (2023) on a group of 235 patients, compared different prognostic scores: Mannheim Peritonitis Index (MPI), the Jabalpur Peritonitis Index, and p-POSSUM. It was a prospective observational cohort study conducted between 2018 and 2020 on patients with secondary non-traumatic peritonitis who underwent laparotomy. The study concluded that the Mannheim Peritonitis Index and p-POSSUM had nearly equivalent performance, with AUCs of 0.757 and 0.756, respectively, indicating fair diagnostic performance. The MPI predicted mortality with a sensitivity of 85% (95% CI 74–92) and a specificity of 58% (95% CI 50–65), at a cutoff of MPI ≥ 27 [

30].

A 1994 study, one of the earliest but with a large sample size of 2,003 patients, concluded that the Mannheim Peritonitis Index is a simple and reliable tool for assessing risk and classifying patients with peritoneal inflammation (sensitivity- 86%, specificity- 74%) [

31].

In a retrospective analysis of 168 patients from 2015, Piotr Budzyński aimed to evaluate the MPI score to determine the probability of death among the Polish population undergoing surgery for peritonitis. The optimal cut-off point for the MPI was calculated based on ROC analysis. He concluded that the MPI is a simple and reliable tool for predicting mortality in patients undergoing surgery for peritonitis. It also aids in assessing the risk of postoperative complications and determining the need for intensive care unit treatment. Although the Mannheim score is simple to use and effective, it has some disadvantages, it cannot serve as a preoperative system for stratifying patients by death risk at admission. This is because it requires intraoperative evaluation, such as the type of fluid in the peritoneal cavity, the anatomical site of perforation and histopathological analysis. Another limitation of the score is that it does not account for chronic diseases or major systemic disorders, which are critical risk factors for mortality and serious complications [

32].

In 2017, Pattanaik published a prospective observational study, stating that "

the ROC curve showed the highest sensitivity and specificity of 79% and 70%, respectively, at an MPI of 25." He concluded that the MPI system is effective in predicting mortality, easy to use, and an excellent option for predicting morbidity [

33].

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of MPI scores (some randomly chosen studies).

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of MPI scores (some randomly chosen studies).

| Study |

Sample size |

Sensivity (%) |

Specifity (%) |

| Pathak et al. (2023) [30] |

235 |

85 |

58 |

|

Rajesh Sharma et al. (2015) [34] |

100 |

92 |

78 |

|

Muralidhar et al. (2014) [35] |

50 |

72 |

71 |

| Billing et al. (1994) [31] |

2003 |

86 |

74 |

| Budzyński et al. (2015) [32] |

168 |

66,7 |

97,9 |

| S. K. Pattanaik et al. (2017) [33] |

120 |

79 |

70 |

| Caronna et al. (2021) [36] |

70 |

77,8 |

72,1 |

4.4. The Microbiology

The microbiological spectrum of secondary peritonitis is undergoing changes. The recent recognition of shifts in microbial ecology in critical illness has enhanced our understanding of the factors driving multi-organ failure. Moreover, multi-drug resistant organisms have become increasingly prevalent globally. The “Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections Worldwide” association study highlighted the rising incidence of these resistant organisms [

37]. For example, the occurrence of extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli nearly tripled worldwide from 2002 to 2008, while resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae approaches 20% [

38]. Enterococci species, often found in nosocomial sepsis, are also showing increased resistance. Pseudomonas infections are now recognized as an independent risk factor for mortality, and candidal infections have been shown to significantly raise mortality rates in critically injured patients [

39,

40]. As resistance patterns continue to evolve, resistant organisms increasingly impact the outcomes of critically ill patients with abdominal sepsis. Therefore, we advocate for all surgeons to support the Global Alliance for Infections in Surgery, which aims to educate and involve all professionals in the fight with surgical infections [

41].

4.5. Future Directions. Artificial Intelligence

Terms like AI, machine learning, and deep learning are becoming more and more common in everyday life and across all professions. Medicine is no exception, even though interaction between people is an essential factor in the domain [

42]. Artificial intelligence (AI) is making significant strides in the field of surgery as well and its application in managing abdominal sepsis is gaining attention where early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are crucial for improving outcomes. In this context, AI offers the potential to assist healthcare professionals by improving diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment planning [

43].

One of the key areas where AI is proving beneficial is in the development of predictive models for clinical outcomes. For example, AI can analyze large datasets from patients with peritonitis, incorporating factors such as: patient demographics, comorbidities, laboratory data, imaging studies to predict mortality or morbidity risk and postoperative complications. This can aid in timely decision-making, helping physicians identify high-risk patients who may require intensive care or more aggressive treatment strategies. Predictive algorithms like the Mannheim Peritonitis Index have already shown effectiveness, as I described above in this article, but AI-enhanced models could further refine their accuracy by using machine learning techniques to continuously update and improve predictions based on new data.

AI-driven image analysis is another promising area. AI algorithms can be trained to detect subtle patterns in these images, this could reduce the time taken to identify peritoneal inflammation, bowel perforations, or abscesses, allowing for quicker intervention and better patient outcomes [

44].

Furthermore, AI can assist in the optimization of treatment plans. By analyzing data from numerous cases, AI can help tailor antibiotic therapy, predict patient responses. This can enhance the precision of treatment and potentially reduce the length of hospital stays and healthcare costs.

Ching Cheng in his study from 2023 applied Artificial Intelligence of LINE Chatbot with the aim of improving the self-care of patients who perform peritoneal dialysis. With the help of artificial intelligence, peritonitis proportion reduced from 0.93 to 0.8/100 patient month [

45].

Another study from 2023 describes the usefulness of artificial intelligence in acute appendicitis, including in late cases when acute peritonitis associated with appendicitis occurs. The authors conclude that AI algorithms show great potential in diagnosing and predicting acute appendicitis (AA), frequently outperforming traditional methods and clinical scoring systems like the Alvarado score in both speed and accuracy [

46].

Despite these advancements, challenges remain. The integration of AI into clinical practice requires robust datasets, regulatory approvals, and collaboration between AI developers and healthcare providers. Ethical concerns regarding data privacy and the potential for AI to replace human judgment also need to be carefully managed.

5. Conclusions

There is a large amount of data on prognostic factors, making it difficult to systematize. Especially age, severe sepsis, cancer, preoperative organ failure, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular conditions and diabetes mellitus have been identified as factors that increase morbidity and mortality in secondary generalized peritonitis. Various scores have been developed over time to assess prognosis, with one of the most accessible being the Mannheim Peritonitis Index. However, the available evidence could serve as a database for artificial intelligence, which promises to significantly aid us in the near future.

References

- Ross, J.T.; Matthay, M.A.; Harris, H.W. Secondary peritonitis: principles of diagnosis and intervention. BMJ 2018, 361, k1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzheimer, R.G. Management of secondary peritonitis. In Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented; Holzheimer, R.G., Mannick, J.A., Eds.; Zuckschwerdt; Munich, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ouf, T.I.; Jumuah, W.A.A.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Abdelbaset, R.I. Mortality rate in patients with Secondary Peritonitis in Ain Shams University Hospitals as regard Mannheim Peritonitis Index (MPI) score. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 2020, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doklestić, S.K.; Bajec, D.D.; Djukić, R.V.; Bumbaširević, V.; Detanac, A.D.; Detanac, S.D.; Bracanović, M.; Karamarković, R.A. Secondary peritonitis -evaluation of 204 cases and literature review. Journal of medicine and life 2014, 7, 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Strobel, O.; Werner, J. Surgical therapy of peritonitis. Chirurg 2011, 82, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, M.; Franke, C.; Ohmann, C.; Yang, Q.; the Acute Abdominal Pain Study Group Acute appendicitis in late adulthood: incidence, presentation, and outcome. Results of a prospective multicenter acute abdominal pain study and a review of the literature. Langenbeck's Arch. Surg. 2000, 385, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, A.; Marrelli, D.; Scheiterle, M.; Di Mare, G.; Sforza, S.; Roviello, F. Re-evaluation of Mannheim prognostic index in perforative peritonitis: Prognostic role of advanced age. A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 13, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamone, G.; Licari, L.; Falco, N.; Augello, G.; Tutino, R.; Campanella, S.; Guercio, G.; Gulotta, G. Mannheim Peritonitis Index (MPI) and elderly population: prognostic evaluation in acute secondary peritonitis. Il Giornale di Chirurgia - Journal of the Italian Association of Hospital Surgeons 2016, 37, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya Daniel, A.; Nathens Avery, B. Risk Factors for Severe Sepsis in Secondary Peritonitis. Surgical Infections, 2003/12/01, p 355-362, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers.

- Biondo, S.; Ramos, E.; Fraccalvieri, D.; Kreisler, E.; Ragué, J.M.; Jaurrieta, E. Comparative study of left colonic Peritonitis Severity Score and Mannheim Peritonitis Index. Br. J. Surg. 2006, 93, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.-K.; Bang, S.-L.; Sim, R. Surgery for Small Bowel Perforation in an Asian Population: Predictors of Morbidity and Mortality. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2010, 14, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.-K.; Hong, C.-C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.Z.; Sim, R. Predictors of Outcome Following Surgery in Colonic Perforation: An Institution’s Experience Over 6 Years. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2011, 15, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, J.T.; Kiviniemi, H.; Laitinen, S. Prognostic Factors of Perforated Sigmoid Diverticulitis in the Elderly. Dig. Surg. 2005, 22, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, P.S.; Dar, L.A.; Hayat, H. Predictors of mortality and morbidity in peritonitis in a developing country. Turk. J. Surg. 2013, 29, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus, D.C.; Linde-Zwirble, W.T.; Lidicker, J.; Clermont, G.; Carcillo, J.; Pinsky, M.R. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: Analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 29, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, C.R.; Boehmer, E.D.; Kovacs, E.J. The aging innate immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2005, 17, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luțenco, V.; Rebegea, L.; Beznea, A.; Tocu, G.; Moraru, M.; Mihailov, O.M.; Ciuntu, B.M.; Luțenco, V.; Stanculea, F.C.; Mihailov, R. Innovative Surgical Approaches That Improve Individual Outcomes in Advanced Breast Cancer. Int. J. Women's Health 2024, 16, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolonen, M.; Sallinen, V.; Mentula, P.; Leppäniemi, A. Preoperative prognostic factors for severe diffuse secondary peritonitis: a retrospective study. Langenbeck's Arch. Surg. 2016, 401, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, D.S.; Dembla, A.; Mahanty, P.R.; Kant, S.; Chatterjee, A.; Samaddar, D.P.; Chugh, P. Comparative analysis of APACHE-II and P-POSSUM scoring systems in predicting postoperative mortality in patients undergoing emergency laparotomy. World J. Clin. Cases 2019, 7, 2227–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, D.I.; Murray, D.; Pichel, A.C.; Varley, S.; Peden, C.J. Variations in mortality after emergency laparotomy: the first report of the UK Emergency Laparotomy Network. Br. J. Anaesth. 2012, 109, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špička, P.; Chudáček, J.; Řezáč, T.; Starý, L.; Horáček, R.; Klos, D. Prognostic Significance of Simple Scoring Systems in the Prediction of Diffuse Peritonitis Morbidity and Mortality. Life 2022, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Hoore, W.; Bouckaert, A.; Tilquin, C. Practical considerations on the use of the charlson comorbidity index with administrative data bases. J. Clin. Epidemiology 1996, 49, 1429–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montravers, P.; Esposito-Farèse, M.; Lasocki, S.; Grall, N.; Veber, B.; Eloy, P.; Seguin, P.; Weiss, E.; Dupont, H. Risk factors for therapeutic failure in the management of post-operative peritonitis: a post hoc analysis of the DURAPOP trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 3303–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaya, D.A.; Nathens, A.B. Risk Factors for Severe Sepsis in Secondary Peritonitis. Surg. Infect. 2003, 4, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špička, P.; Chudáček, J.; Řezáč, T.; Vomáčková, K.; Ambrož, R.; Molnár, J.; Klos, D.; Vrba, R. Prognostic significance of comorbidities in patients with diffuse peritonitis. Eur. Surg. 2022, 54, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailov, R.; Firescu, D.; Constantin, G.B.; Mihailov, O.M.; Hoara, P.; Birla, R.; Patrascu, T.; Panaitescu, E. Mortality Risk Stratification in Emergency Surgery for Obstructive Colon Cancer—External Validation of International Scores, American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Surgical Risk Calculator (SRC), and the Dedicated Score of French Surgical Association (AFC/OCC Score). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, G.B.; Firescu, D.; Voicu, D.; Stefanescu, B.; Serban, R.M.C.; Berbece, S.; Panaitescu, E.; Birla, R.; Marica, C.; Constantinoiu, S. Analysis of Prognostic Factors in Complicated Colorectal Cancer Operated in Emergency. Chirurgia 2020, 115, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulari, K.; Leppäniemi, A. Severe Secondary Peritonitis following Gastrointestinal Tract Perforation. Scand. J. Surg. 2004, 93, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, M.M.; Wacha, H.; Feldmann, U.; Wesch, G.; Streifensand, R.A.; Gundlach, E. [The Mannheim peritonitis index. An instrument for the intraoperative prognosis of peritonitis]. Chirurg 1987, 58, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, A.A.; Agrawal, V.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, K.; Bagla, C.; Fouzdar, A. Prediction of mortality in secondary peritonitis: a prospective study comparing p-POSSUM, Mannheim Peritonitis Index, and Jabalpur Peritonitis Index. Perioper. Med. 2023, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billing, A.; Fröhlich, D.; Schildberg, F.W. Prediction of outcome using the Mannheim peritonitis index in 2003 patients. Peritonitis Study Group. Br. J. Surg. 1994, 81, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzyński, P.; Dworak, J.; Natkaniec, M.; Pędziwiatr, M.; Major, P.; Migaczewski, M.; Matłok, M.; Budzyński, A. The usefulness of the Mannheim Peritonitis index score in assessing the condition of patients treated for peritonitis. Pol. J. Surg. 2015, 87, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, S.K.; John, A.; Kumar, V.A. Comparison of mannheim peritonitis index and revised multiple organ failure score in predicting mortality and morbidity of patients with secondary peritonitis. Int. Surg. J. 2017, 4, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, V.; Sharma, R.; Jain, S.; Joshi, T.; Tyagi, A.; Chaphekar, R. A prospective study evaluating utility of Mannheim peritonitis index in predicting prognosis of perforation peritonitis. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2015, 6, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A, M.V. Efficacy of Mannheim Peritonitis Index ( M PI ) Score in Patients with Secondary Peritonitis. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, NC01-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobome, S.R.; Allode, S.A.; Hodonou, M.A.; Hessou, T.K.; Caronna, R. Mannheim Peritonitis Index: usefulness in a context with limited resources. J. Gastric. Surg. 2021, 3(2). [Google Scholar]

- Sartelli, M.; Catena, F.; Ansaloni, L.; Coccolini, F.; Corbella, D.; E Moore, E.; Malangoni, M.; Velmahos, G.; Coimbra, R.; Koike, K.; et al. Complicated intra-abdominal infections worldwide: the definitive data of the CIAOW Study. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2014, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartelli, M.; Bassetti, M. Martin-Loeches I: Abdominal sepsis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Sakr, Y.; Sprung, C.L.; Ranieri, V.M.; Reinhart, K.; Gerlach, H.; Moreno, R.; Carlet, J.; Le Gall, J.-R.; Payen, D.; et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: Results of the SOAP study. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Righi, E.; Ansaldi, F.; Merelli, M.; Cecilia, T.; De Pascale, G.; Diaz-Martin, A.; Luzzati, R.; Rosin, C.; Lagunes, L.; et al. A multicenter study of septic shock due to candidemia: outcomes and predictors of mortality. Intensiv. Care Med. 2014, 40, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartelli, M.; Weber, D.G.; Ruppé, E.; Bassetti, M.; Wright, B.J.; Ansaloni, L.; Catena, F.; Coccolini, F.; Abu-Zidan, F.M.; Coimbra, R.; et al. Antimicrobials: a global alliance for optimizing their rational use in intra-abdominal infections (AGORA). World J. Emerg. Surg. 2016, 11, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luțenco, V.; Țocu, G.; Guliciuc, M.; Moraru, M.; Candussi, I.L.; Dănilă, M.; Luțenco, V.; Dimofte, F.; Mihailov, O.M.; Mihailov, R. New Horizons of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine and Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amisha; Malik, P.; Pathania, M.; Rathaur, V.K. Overview of artificial intelligence in medicine. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 2328–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, A.; Parmar, C.; Quackenbush, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Lin, W.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Chiang, C.; Hung, K. Implementation of artificial intelligence Chatbot in peritoneal dialysis nursing care: Experience from a Taiwan medical center. Nephrology 2023, 28, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issaiy, M.; Zarei, D.; Saghazadeh, A. Artificial Intelligence and Acute Appendicitis: A Systematic Review of Diagnostic and Prognostic Models. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2023, 18, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).