1. Introduction

Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems offer a versatile, rapid and efficient approach to protein synthesis and have demonstrated production of proteins with high molecular weight; 120 kDa in E. coli, 116 kDa in insect, 160 kDa – 260 kDa in HeLa and rabbit reticulocyte [

1,

2,

3]. With the maturation of this technology over the past decade, focus has now shifted to instant production of proteins at any desired time and location for utility in fields such as pharmaceuticals (biotherapeutics), diagnostics and biomanufacturing (small molecules and platform compounds). These on-demand systems are required to be compact, easily transportable and stable, for suitability in resource-limited settings and/or extreme environments [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These requirements are fulfilled, in part, by lyophilised CFPS systems, including "just-add-water" approaches, which offer enhanced stability compared to liquid CFPS [

8,

9]. Lyophilised CFPS has been shown to retain 79% ± 16% activity at 4°C, and 35.3% ± 7.3% activity at 23 °C for two weeks, surpassing the 56.7% ± 8.9% at 4 °C and no activity at 23 °C reported for liquid extracts [

10]. Meanwhile, Pardee et al. showed that freeze dried cell-free reactions derived from NEB PURExpress™ were stable up to one year at room temperature, which they exploited, for in vitro diagnostics applications [

11]. The fact that the reconstituted CFPS system is more stable than cell derived CFPS systems suggests that the complex mixture of proteins in the latter may be accelerating degradation.

Sugars and other molecules are often incorporated as excipients for biotherapeutic formulation and stabilisation, aiding preservation of native protein structure during lyophilisation and at elevated storage temperatures [

12]. Sugars exert their mechanism of action by forming a protective shell through water replacement and strengthening intramolecular hydrogen bonds, thereby protecting proteins from denaturation and aggregation [

13]. This influence makes sugars a valuable additive in CFPS reactions for stabilisation of proteins under stressful conditions, such as during lyophilisation, freeze-thaw, and heat shock. Highly reported candidates for CFPS stabilisation include sucrose, trehalose, and lactose, and molecular crowding agents such as PEG, trimethylglycine, and dextran (e.g. β-cyclodextrin) [

10,

14,

15,

16]. Agents with different mechanisms of action (

e.g. sugars and crowding agents) can be supplemented together for a beneficial combinatorial effect on stability. Previously discussed lyophilised CFPS stored at 23°C for two weeks displayed full preservation through the combinatorial effect of three supplements (trehalose, trimethylglycine, and PEG), an improvement from 35.3% ± 7.3% activity with no supplements [

10].

In this work, we aimed to assess the potential of cell-free systems for on-site applications compared to traditional expression methods, and their ability to be employed in resource-constrained settings in a user-friendly manner. We first described an optimised in-house bacterial cell-free system with capabilities that matched commercial systems such as PURExpress® through overexpression of soluble T7 RNA polymerase. We next experimented with lyophilised pellets and cellulose stacks and evaluated their impacts on CFPS yield and stability. As our results indicated a loss of stability over time, we turned our attention to screening various supplements that have had known positive effects in the past. Previously unknown effects of the supplements on CFPS kinetics were discovered and further insights into short-term stability were obtained. Taking inspiration from previous simplistic design of experiments (DoE) type approaches for other applications, we opted for a similar approach to identify combinations of high-performing supplement [

17]. One such DoE combination from our minimalistic design led to 100% preservation of CFPS stability at room temperature for one month. Based on the work carried out here compared to elsewhere, we found that optimisation of supplements must be carried out for each unique CFPS system due to variability in stability between research groups. Our short-term screening and design of experiments approach describes a minimalistic and cost-effective method for improvement of CFPS stability without time and resource-intensive studies, which can be easily transferable to other CFPS systems. Additionally, the systems described in this paper brings on-demand biomanufacturing and biosensing one step closer to utilisation in extreme and low-resource environments while reducing the costs and carbon footprint associated with unstable systems requiring cold-chain supply.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Growth Condition

Escherichia coli BL21 Star (DE3) [E. coli BL21 Star (DE3)] was transformed with plasmid pAR1219, purchased from Sigma Aldrich (TargeTron™), to obtain recombinant strain E. coli BL21 Star (DE3)-pAR1219; which was used for all the extract preparation except otherwise mentioned. The superfolder green fluorescence protein (sfGFP) gene fragment sfgfp was obtained from pBAD24-sfgfpx1 (Addgene plasmid #51558), amplified by PCR and assembled using NEB HiFi DNA into a pET20b vector with a 6xHistidine tag to obtain pET20b-sfgfp-6xHis (the template DNA for CFPS, except otherwise mentioned) and cloned into E. coli NEB5α. Also, empty pET20b (the control DNA for CFPS, except otherwise mentioned) was cloned into E. coli NEB5α. Plasmid DNA (pET20b-sfgfp-6xHis and pET20b) was extracted from E. coli NEB5α - pET20b-sfgfp-6xHis and E. coli NEB5α - pET20b, grown overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, supplemented with 100 µg/mL ampicillin at 37°C and 250 revolution per minute (RPM). A maxiprep kit (Qiagen) was used to perform plasmid extraction following manufacturer’s protocol. DNA was eluted in nuclease-free water and the final concentration was measured using a Nanodrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific).

2.2. Cell-Free Extract Preparation

E. coli BL21 Star (DE3)-pAR1219 cells were grown overnight in LB broth supplemented with 100 µg/mL ampicillin. This overnight culture was used to inoculate 750 mL 1x YTPG media (10 g/L yeast extract, 16 g/L tryptone, 7 g/L KH2PO4, 3 g/L K2HPO4, 0.4 M glucose and 5 g/L NaCl) supplemented with 100 µg/mL ampicillin in 2 L baffled shake flasks, at a starting optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1. Cell growth was conducted at 37°C, 250 RPM, and T7 polymerase expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside) at OD600 0.8. Thereafter, cells were allowed to grow up to OD600 4.0 and harvested by centrifugation at 7000 RPM and 4°C for 5 minutes. Cell pellet was washed three times and lastly resuspended in S30A buffer (50 mM Tris, 14 mM magnesium glutamate, 60 mM potassium glutamate, pH 7.8). Cell suspension was supplemented with protease inhibitor (Roche) and 2 mM dithiothreitol. Extract was prepared by sonication of harvested cell suspension for 3 minutes (four cycles of 45 seconds with one-minute rest intervals) on ice using a Bandelin Sonopuls HD 2070 ultraprobe Digital Sonicator (Bandelin Electronics, Berlin, Germany) at 70% amplitude. Lysate was supplemented with an additional 2 mM dithiothreitol followed by clarified by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 18,000 x g and 4°C. A run-off reaction was then carried out for one hour at 37°C and 250 RPM. The final extract was prepared by centrifuging the run-off reaction for 10 minutes at 12,000 x g and 4°C, which was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until use. Protein concentration was quantified using a Micro BCA™ Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.3. Cell-Free Protein Synthesis

In-house CFPS reactions were set up on ice as previously described

18, and were incubated at 37°C and 180 RPM with composition outlined in

Table 1, whereas kinetic sfGFP fluorescence assays were set up in black, flat bottom 96-well assay plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reaction mix varied according to experimental design where the volume of water or stock concentration was adjusted where necessary and master mixes were prepared for DoE experiments to reduce variation in the incubation times for each condition. Supplements described in the stability studies were prepared as 1 M stocks in nuclease free water and stored at 4°C for up to a month. Polyethylene glycol (PEG; molecular weight 600 g/mol, 6000 g/mol, and 8000 g/mol) was prepared as a 50% w/v stock, diluted in nuclease-free water.

Lyophilised cell-free reactions were prepared in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after set-up. The reactions were placed in a freeze-drier prechilled to -60°C and were lyophilised overnight under vacuum (<120 mTorr) using a VirTis Benchtop Lyophiliser Sentry 2.0.

Analytic techniques for determining cell-free sfGFP synthesis included time course and endpoint analyses. For kinetic time course analysis, continuous fluorescence readings were taken for 12 - 24 hours in a plate reader (TECAN Spark® Multimode Microplate reader) every 10 minutes. For timepoint analysis, fluorescence recordings and protein samples were retrieved after incubation of cell-free reactions for four hours in a shaker incubator revolving at 180 RPM. Recordings were taken using a NanoDrop™ 3300 Fluorospectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In both cases, the excitation and emission wavelength for sfGFP detection were 485 nm and 510 nm, respectively.

2.4. CFPS on Cellulose Stacks

Lyophilization of aqueous components onto paper discs serves as a versatile scaffold for the assembly of CFPS reactions in a modular fashion. Preliminary experiments employed toilet paper; however, due to the absence of controlled and verified properties, an exploration for an alternative substrate ensued. Seven paper types with validated laboratory applications were evaluated: Toilet paper; Whatman Number 1 filter paper; Whatman Number 5 filter paper; Cellulose triacetate (Selectophore®); Hydrosart Membrane Filter (Sartorius); Polyethersulfone membrane (Sartorius); Nitrocellulose Membrane, 0.45 µm (BioRad).

Autoclaved and hole-punched paper discs of 5 mm diameter each were added to either extract supplemented with RNAse Inhibitor, DNA template, or energy and buffers, with final concentrations outlined in

Table 1. Freeze drying was carried out by flash-freezing paper containing tubes in liquid nitrogen and lyophilised overnight. Rehydration was carried out by layering each of the three papers (one each with extract, DNA, and buffers – see

Figure 2, c) in one tube with the addition of 40 µL S30A buffer. Reactions were incubated at 37°C and 180 RPM overnight, unless otherwise specified. sfGFP expression was determined as described previously.

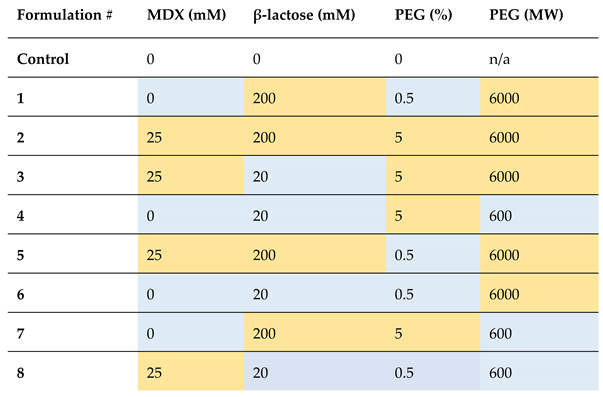

2.5. Design of Experiments (DoE)

A two-factor factorial design was employed to investigate the relationship between sfGFP fluorescence and four independent variables (supplement final concentration in cell-free reaction): maltodextrin (mM), β-lactose (mM), PEG (MW), and PEG (%). The experimental design was generated using MiniTab software (Version 21.3) ‘general full factorial design’ tool. The study consists of 8 experimental runs including 3 repeats for each additive combination, and a control run with the absence of the 4 test factors. Randomization of the run order was performed using a seed generated by the software. Samples were prepared, lyophilised, and rehydrated as described previously with the addition of the run-specific factors. The fluorescence of the samples was used as the response variable, as the standard proxy for sfGFP yield. MiniTab was further used for factorial design analysis in a stepwise selection method to automatically select main effects and/or two-factor interactions using a factorial regression model and factorial ANOVA. The response variable (fluorescence) was regressed against the main effects and two-way interactions of the factors. Coded coefficients were derived to facilitate comparisons between factors.

2.6. Stability Studies

The accelerated stability studies of lyophilised CFPS were planned according to temperature, humidity and time requirements as per ICH guidelines. An adequate number of 50 µL stability samples were prepared and lyophilised in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. Each stability sample was labelled with a batch number, temperature, date of preparation, and sampling time point and placed in a stability oven (40°C ± 2°C/75% RH ± 5% RH) or cold room (4°C). For room temperature experiments (average 19°C), samples were placed on the lab bench beside a temperature monitor (Thermopro TP49). Sample stability at set time points was analysed by first rehydrating the sample with S30A buffer to 80% reaction volume following incubation at 37°C for 16 hours at 180 RPM, followed by endpoint fluorescence analysis.

2.7. SDS-Page and Western Blotting

For analysis of protein expression, SDS-Page (Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) and western blotting techniques were employed. Samples were denatured with SDS containing sample buffer and separated on a 12% TGX (Tris/Glycine/SDS) gel. Following electrophoresis, gel was stained using InstantBlue™ Coomassie stain (Abcam). For western blot analysis, the gel was instead transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad) using a BioRad Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer system and the SuperSignal™ West HisProbe kit (Thermo Scientific™) was used to obtain an image of the blot (BioRad Gel Doc) following chemiluminescent detection.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Significance was determined between conditions using unpaired, two-tailed t-tests using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA, unless otherwise specified. For stability studies, one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s multiple comparisons test was performed for comparing supplemented CFPS stored for various time points against 0-week and unsupplemented/fresh CFPS. The adjusted p-value denotes the significance of preservation, where p < 0.0001 is marked ****, 0.0001 to 0.001 by ***, 0.001 to 0.01 by **, 0.01 to 0.05 by * and ≥ 0.05 by ns (not significant).

3. Results

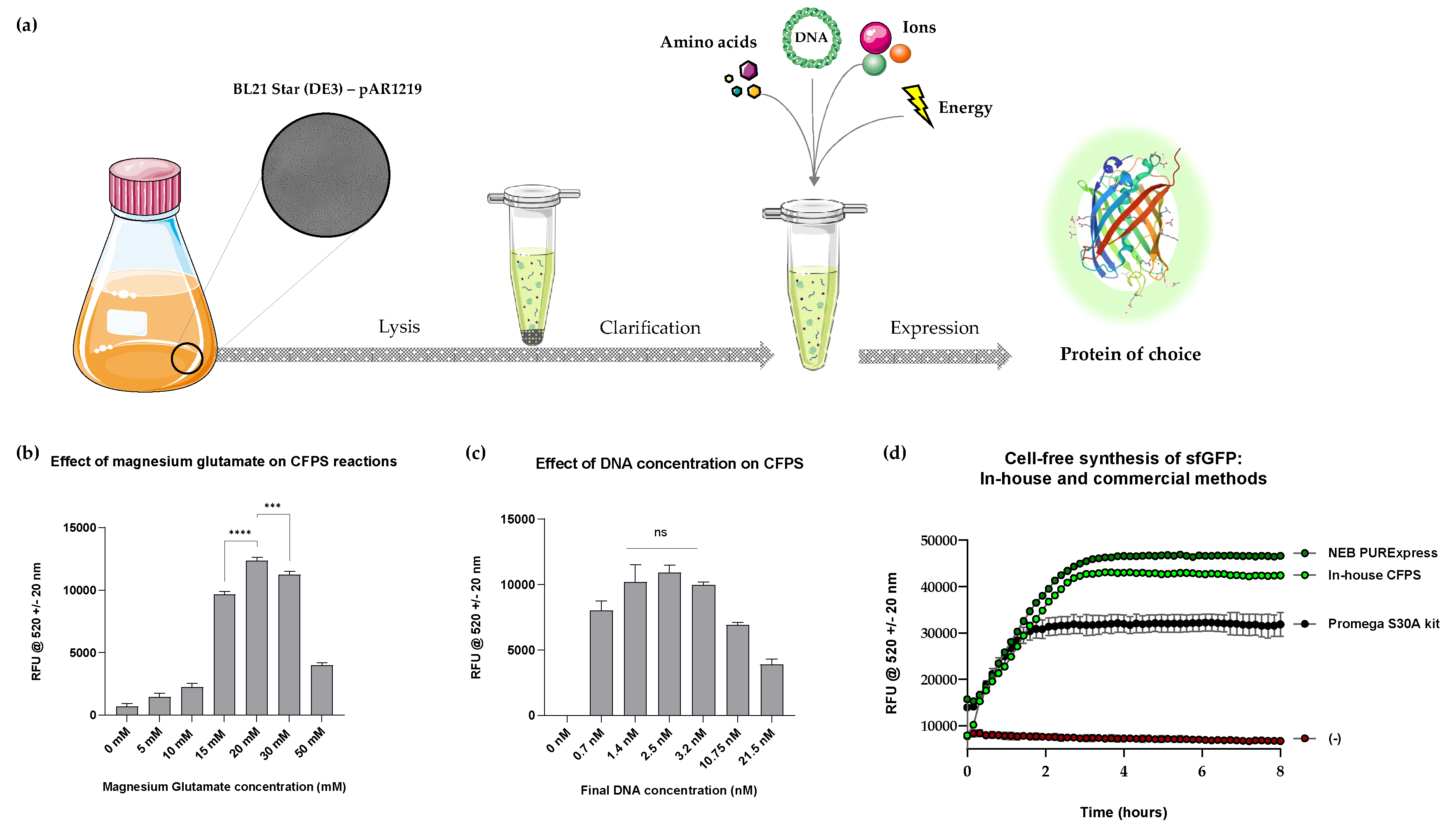

3.1. Development and Optimisation of Bacterial Cell-Free System

Wild type (WT) E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) was chosen as the lead candidate for cell-free extract preparation owing to its high protein expression capabilities, quick growth/reaction times, and an already well-established history with CFPS.18 Due to the high level of soluble and active T7 polymerase required for effective CFPS, the enzyme is often supplemented in the reaction, making it more expensive and time-consuming. To address this challenge and optimise CFPS, pAR1219 was transformed in WT E. coli to enhance its endogenous levels of T7 RNA polymerase. We observed that the growth rate of the transformed strain was not significantly different to WT (

Supplementary Figure S1). Additionally, T7 polymerase expression levels were detected in both the E. coli BL21 Star (DE3)-pAR1219 and WT within two hours after induction using SDS-Page analysis. However, stronger expression was seen in E. coli BL21 Star (DE3)-pAR1219 induced with IPTG. Although a similar pattern was observed five hours after induction, T7 polymerase was present predominantly in the insoluble fraction (

Supplementary Figure S5). These results suggest that cells used for cell-free extract preparation must be harvested by 2 hours post-induction at 37°C. This corelates well with mid-exponential phase of growth and timings of harvest reported in other methods [19,20,21,22].

Successful CFPS relies on optimal concentrations of multiple components in the reaction mix. Magnesium ions (Mg2+) is a known cofactor for the many enzymes involved in translation, is involved in ribosome assembly, and appears to play a protective role during lyophilisation of proteins [23,24,25]. One of the key objectives of this study was to identify an optimal magnesium glutamate (Mg-Glu) concentration, as previous studies have particularly emphasised the importance of its optimisation for each new cell-free extract preparation [23,26,27].

A range of Mg-Glu concentrations (0 mM to 50 mM) was chosen and time course analyses were performed in 5 mM increments. It was clear that an absence of Mg-Glu inhibited protein synthesis and the highest fluorescence signal was detected in samples that contained 20 mM Mg-Glu (

Figure 1, b). Concentrations higher than 20 mM seemed to repress protein synthesis, agreeing with other reported outcome [28,29]. Hence, 20 mM Mg-Glu was utilised for all subsequent studies. In addition, a range of DNA concentrations were tested in the Mg-Glu optimised reaction conditions, to identify the concentration that produced the highest fluorescence. Endpoint fluorescence showed an increase in sfGFP with increasing DNA concentrations until 2.5 nM. Then, the yield decreased as a function of DNA concentration (2.5 nM – 21.5 nM;

Figure 1, c). Thus, 2.5 nM DNA and 20 mM Mg-Glu were selected as the optimal concentration for all subsequent studies.

Performance of the optimised reaction composition was compared with commercial CFPS systems such as PURExpress® (manufactured by NEB) and the E. coli S30A Extract System for Circular DNA (manufactured by Promega). PURExpress® is a frontrunning, well-understood and highly efficient reconstituted system composed of purified enzymes derived from E. coli BL21 cells. The Promega system consists of crude bacterial cell extract (from an OmpT endoproteinase and Ion protease knockout strain). Both kits were commercialised from previously published work and are some of the most popular CFPS kits in the market [30,31,32]. Our optimised system was benchmarked against the two commercial systems by comparing the trend of sfGFP synthesis over time under identical conditions (50 µL reactions incubated at 37°C, the temperature recommended by both manufacturers). Time course analyses revealed that our in-house CFPS system closely mimicked the PURExpress® trend and exceeded the yield from the Promega system (

Figure 1, d). While the yield of sfGFP from PURExpress® exceeded both that of the in-house and Promega system, the yield of in-house CFPS was significantly higher than Promega and closely matched (to 90%) that of PURExpress®. Since in-house CFPS and Promega CFPS were based on similar strains, enhancement of T7 RNA polymerase levels and optimisation of Mg-Glu and DNA concentration alone has led to an increase in CFPS yield. Optimisation of other component concentrations such as energy mix could be explored for the possibility of further exceeding output.

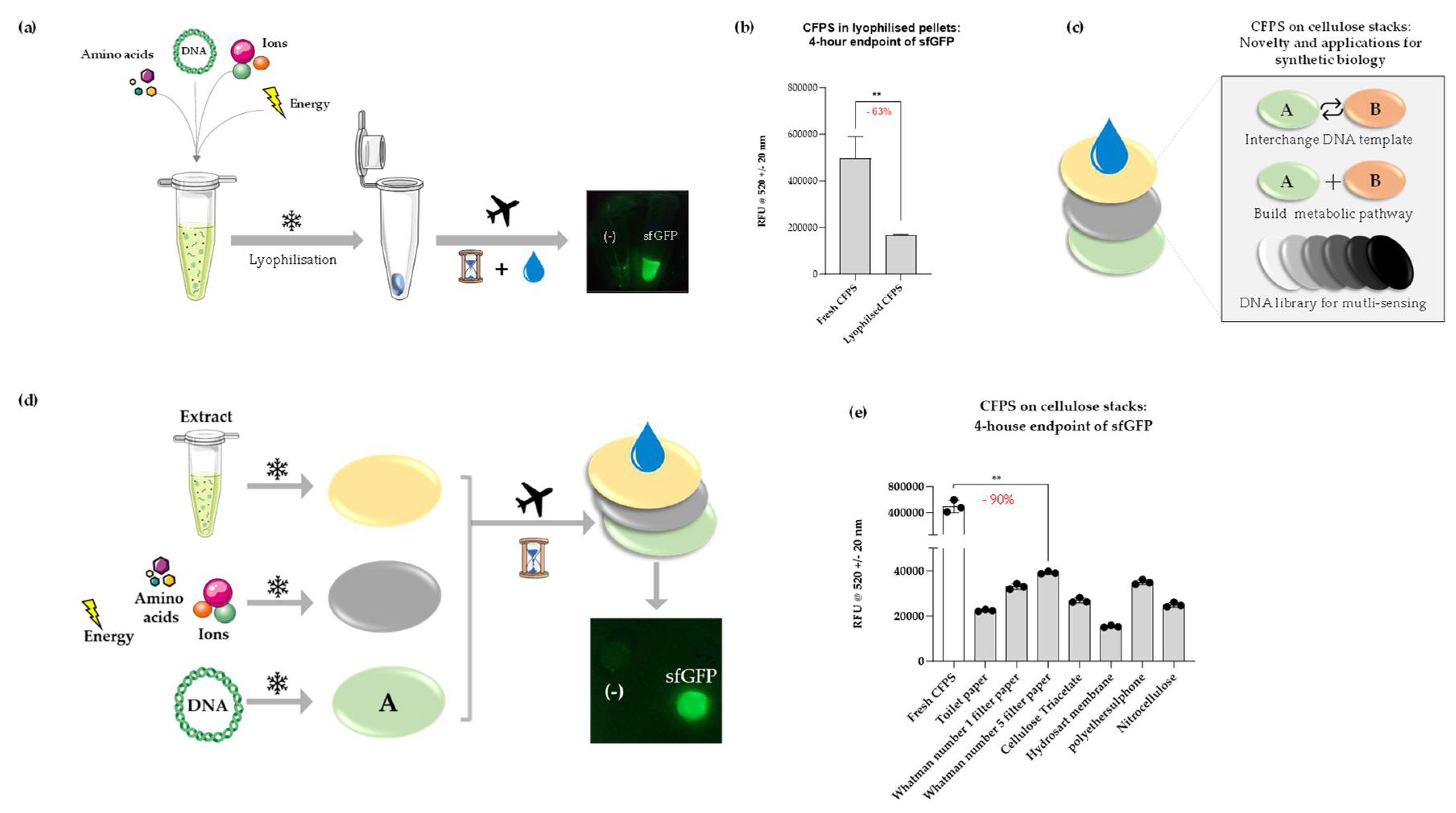

3.2. On-Demand Synthesis Enabled by Lyophilised and Paper-Based Formats

Lyophilisation (or freeze-drying) is one of the most employed methods for the development of solid formulations of proteins mainly to enhance stability. This method offers many benefits and presents many challenges, which are mostly well-understood and thoroughly reviewed in the past few decades [33,34,35]. Lyophilisation methods were also, unsurprisingly, employed for cell-free systems, with both extracts and whole cell-free reactions preserved. This contributed to enhanced stability, when compared to standard liquid formats, but also enabled easy transportation and revival after rehydration - attributes that are highly desirable for on-site and on-demand applications [9,14,36,37].

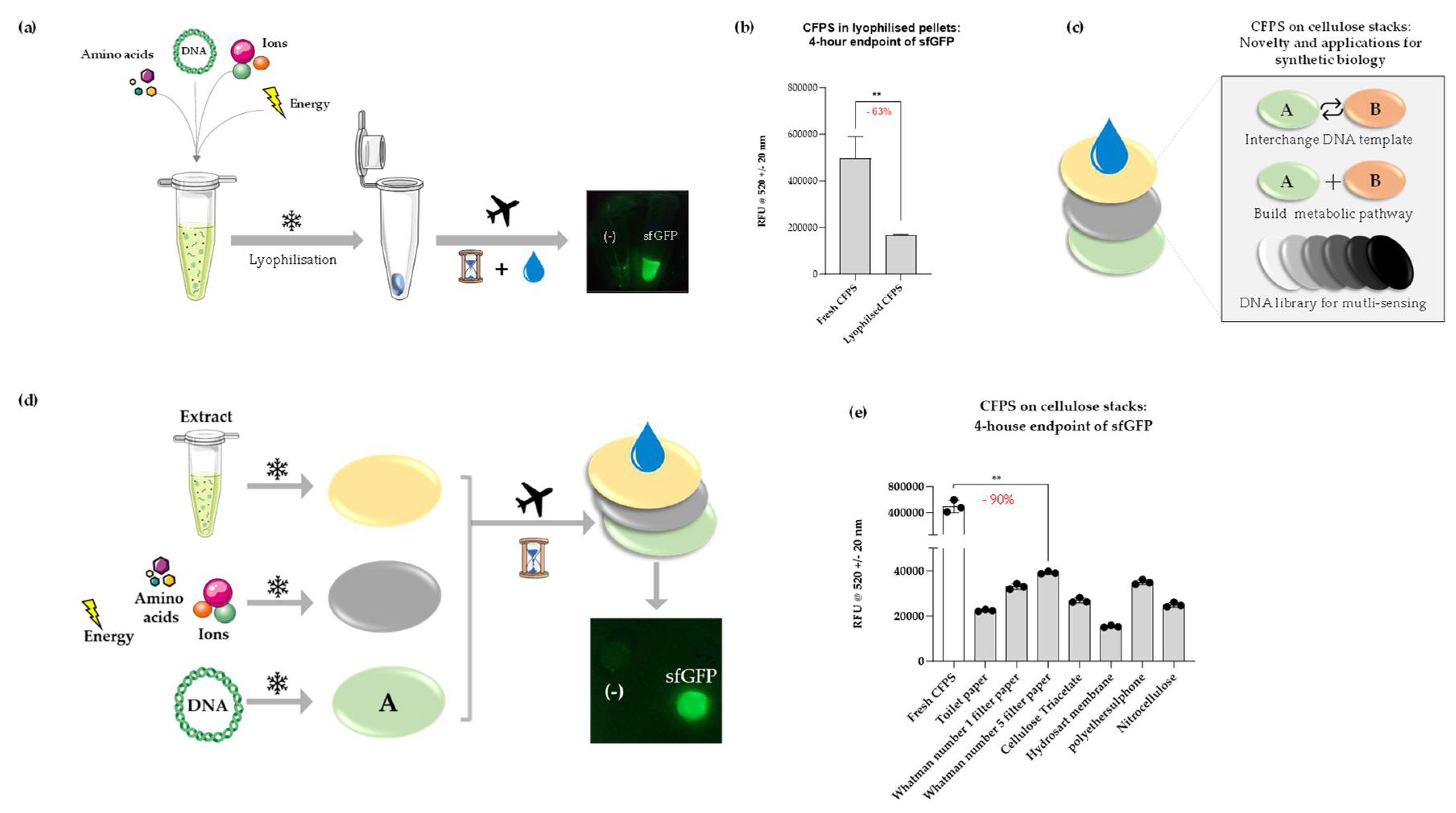

We first evaluated the ability of CFPS to be preserved in this manner, by lyophilising cell-free reactions overnight (

Figure 2, a). The impact of this procedure was studied by measuring cell-free sfGFP synthesis immediately following rehydration of the lyophilised pellets. sfGFP fluorescence from samples that underwent lyophilisation was reduced by ~ 63% when compared to freshly prepared CFPS reactions (

Figure 2, b). Despite this, a strong fluorescence signal was observed when samples were placed under a blue-light transilluminator. We applied this lyophilisation method to develop a tunable paper-based CFPS platform, primarily for biosensing applications similar to others described for educational kits and portable applications [11,39,40]. The intention behind the paper-based platform is to create an interchangeable and flexible approach where the DNA component may be easily changed to produce any therapeutic at point-of-care, that is also easy to adapt for high-throughput sensing applications (

Figure 2, c). The key components of this platform were three cellulose discs individually lyophilised with the following CFPS components: cell extract; energy; DNA (

Figure 2, d). The system was designed such that each lyophilised disc could be layered and rehydrated in a modular fashion to kickstart protein synthesis. Seven types of paper were tested for their ability to support lyophilised CFPS components: toilet paper; Whatman Number 1 filter paper, 11 µm; Whatman Number 5 filter paper, 2.5 µm; cellulose triacetate (Selectophore®); Type 144 Hydrosart Ultra Filtration Membrane Discs, 10 kDa MWCO (Sartorius™); polyethersulfone membrane, 0.1 µm, 10 kDa MWCO (Sartorius™) and Nitrocellulose Membrane, 0.45 µm (BioRad).

sfGFP signal from rehydrated cellulose stacks ranged widely depending on the type of paper used (

Figure 2, d). However, a significant reduction (~ 90%) was noted when compared to freshly prepared CFPS reactions, which may perhaps be attributed to the variation in component concentration retained on each layer. Whatman Number 5 filter paper reported the highest signal of all materials tested, whereas hydrosart membrane reported the lowest. Polyethersulphone was initially chosen due to its existing applications in hollow fiber bioreactors and its ability to adsorb proteins efficiently [41]; CFPS reactions supported on this polymer produced the second-highest signal. Evidently, the material properties affect the stability and efficiency of CFPS components immobilised on a stack support. Although it is difficult to draw specific conclusions on the effect of each material due to non-disclosure of all materials by the commercial suppliers, we anticipate highly cellulosic materials supported the reactions well and envisage further investigation by scanning electron microscopy which could shed light on the influence of parameters such as pore size and molecular interaction on CFPS supported on cellulose stacks. Nevertheless, Whatman Number 5 filter paper was identified to be an efficient and cost-effective support for lyophilised CFPS, which contains potential for further improvement in yield with the addition of lyoprotectants. Yet, the signal, as it is, from this cellulose type is adequate for many applications involving on-site biosensing, for example, with easy visualisation of signal under a blue light transilluminator as pictured (

Figure 2, d).

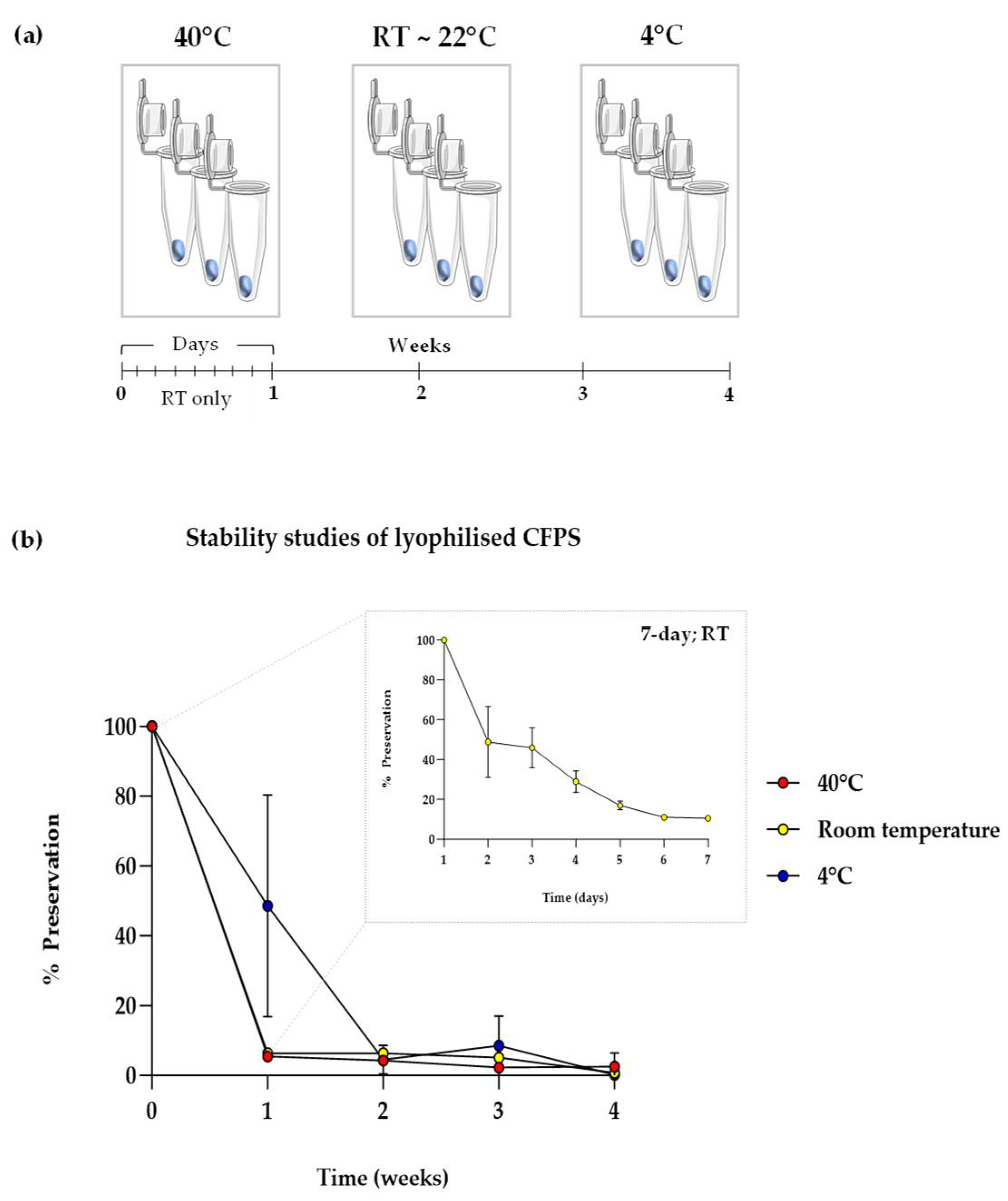

3.3. Lyophilised Cell-Free Systems Perform Poorly in Pharma-Grade Stability Tests

A well-known bottleneck in cell-free synthetic biology is the need to store cell-free components from -20°C to -80°C, owing to their degradation at elevated temperatures. A similar trend for lyophilised cell-free systems has been reported previously, however, the rate of degradation is slower than in aqueous systems, which is attributed to the motionless molecular dynamics in solid state [14,42]. To test if this applied to our lyophilised CFPS system, lyophilised pellets containing sfGFP DNA template were subject to stability studies at three temperatures, namely, 40°C, room temperature (RT; average 19°C) and 4°C (

Figure 3, a). Samples stored at a set temperature were rehydrated and surveyed for cell-free sfGFP synthesis at 5 time-points from day 0 (immediately after lyophilisation) to weeks 1, 2, 3 and 4. lyophilised pellets stored at RT were further sampled from days 1 – 7.

In all temperatures tested, stability dropped significantly over four weeks (

Figure 3, b). All samples stored at 40°C and RT lost activity just one week after storage. Activity of samples at 4°C was significantly higher at one week compared to the former, however a high variation was observed. This suggests that lowering the temperature may enhance stability in the short-term, owing to higher survival rates of proteins and energy components in lyophilised CFPS. Furthermore, a 50% drop in stability was observed just after one day of storage at room temperature, which reduced to 75% by days 4 and 5. By day 7 (1 week), all stability was lost, which was the observed result for all succeeding data points and temperatures. In summary, the shelf-life of lyophilised CFPS was found to be < 1 week and requires substantial improvement for utility. This is, however, not an uncommon result, as similar diminishing trends in stability have been reported previously, where no stability was observed in uncomplemented CFPS after just one day of storage at 37°C [43]. On a similar note, it was discussed that the cell-free extract degraded faster than the other buffer components. Therefore, innovative solutions for enhancing protein stability may aid any efforts in improving the long-term stability of lyophilised CFPS systems, which was our next focus.

3.4. Effects of Various Lyoprotectants and Stabilisers on CFPS Kinetics and Stability at Room Temperature

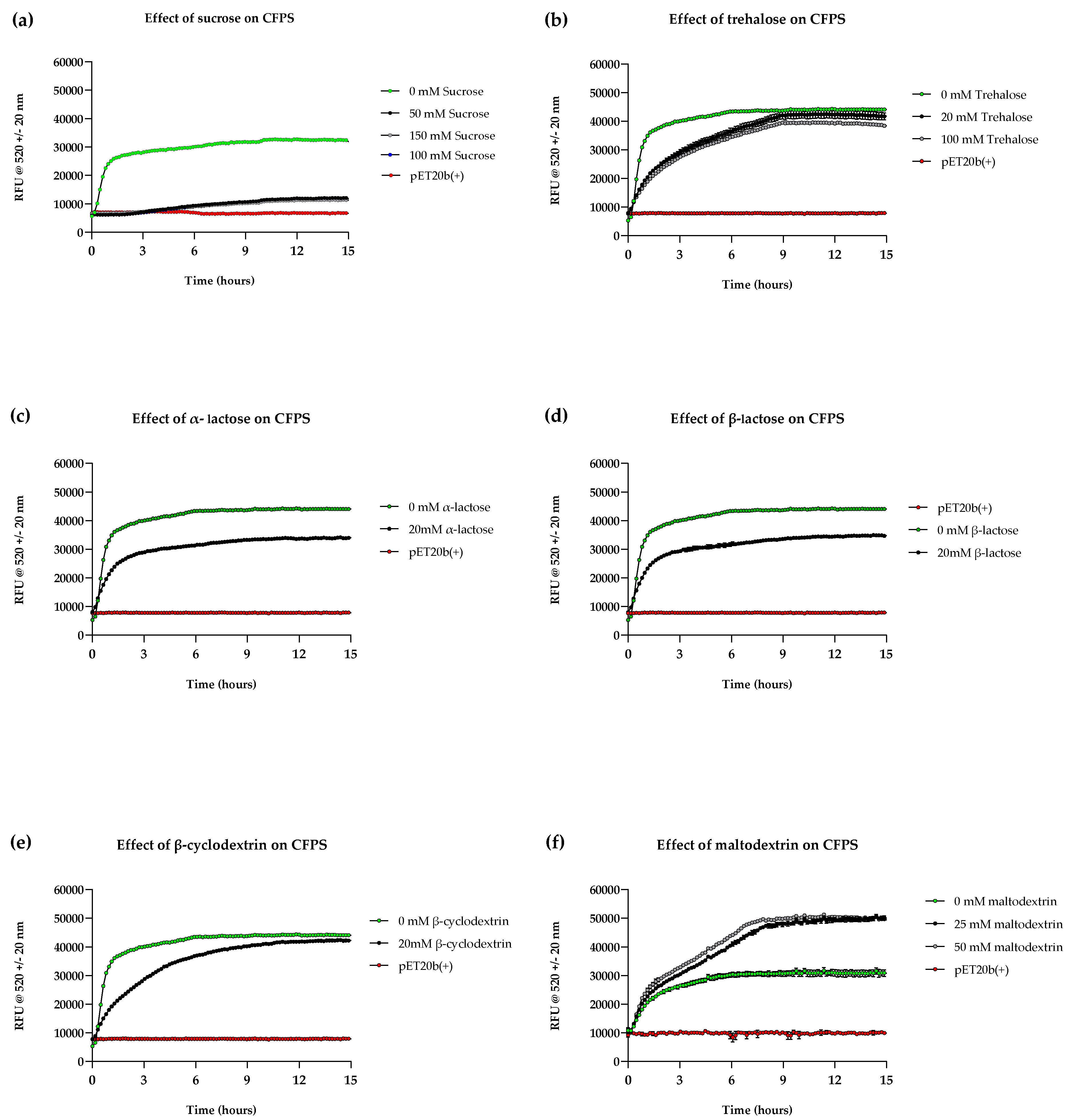

Sugars are often incorporated as excipients in biotherapeutic stabilisation for their ability to preserve native protein structures. During lyophilisation, this is preserved in an amorphous state [12]. Indeed, most reported candidates in literature for CFPS shelf-life stabilisation were carbohydrates such as sucrose, trehalose and lactose, but also other molecular crowding agents such as trimethylglycine and dextrins (e.g. β-cyclodextrin) [10,14,15,16]. We initially sought to study the effect of select protectants sucrose, trehalose, α-lactose, β-lactose, β-cyclodextrin, and maltodextrin (MDX) on cell-free reaction kinetics prior to their impact on stability. Reaction kinetics provides insight into the effects of a particular supplement, which in turn is a key parameter that is required to adapt system design according to the intended application. An example would be rapid point-of-care CFPS whether it is necessary for biomanufacturing or diagnostics, where faster kinetics are desirable. Additionally, no kinetic data is currently available for several of the supplements we investigated.

Time course analyses were conducted to monitor sfGFP synthesis upon supplementation at various concentrations that were selected based upon previously published work, serving as an initial starting point; ranges of concentrations were tested for some candidates where advised [10,14,15,16]. The first observation was that cell-free kinetics and yield were notably different in all supplemented reactions when compared to unsupplemented reactions (

Figure 4). Reactions supplemented with sucrose, trehalose, and β-cyclodextrin displayed significantly lower reaction rates, where synthesis reached saturation at ~ 8 hours whereas unsupplemented reactions saturated 3 – 4 hours after commencement. Reactions supplemented with α/β-lactose displayed dynamics similar to unsupplemented reactions, however sfGFP fluorescence was compromised. Most supplemented reactions had significantly lower signal, with sucrose displaying the lowest (30% of the unsupplemented reaction) and trehalose and β-cyclodextrin displaying the highest (90 and 95% fluorescence of unsupplemented reaction). The low rates of reaction and subsequent yields could be attributed to molar ratios of the supplement and proteins in the cell-free extract – as high affinity of supplements to water reduces molecules available for protein interaction.44 This may explain why a concentration-dependent decrease in yield was observed in reactions supplemented with trehalose and sucrose (e.g. 100 mM trehalose supplement had reduced fluorescence compared to a 20 mM supplement).

On the other hand, MDX outperformed the unsupplemented reaction, suggesting a yield that is 1.5 times that of the latter (

Figure 4, f). As for the reaction kinetics, the initial reaction rate matched that of the unsupplemented reaction, but it was followed by another slower exponential phase in both concentrations tested. By 16 hours, there was no significant difference between 25 mM and 50 mM MDX-supplemented reactions. The increase in sfGFP synthesis may be explained by the role of MDX as a secondary energy source. The second exponential phase of the reaction can be attributed to the slow metabolism of MDX and its phosphate scavenging properties, as accumulation of inorganic phosphate typically leads to reaction saturation [45,46].

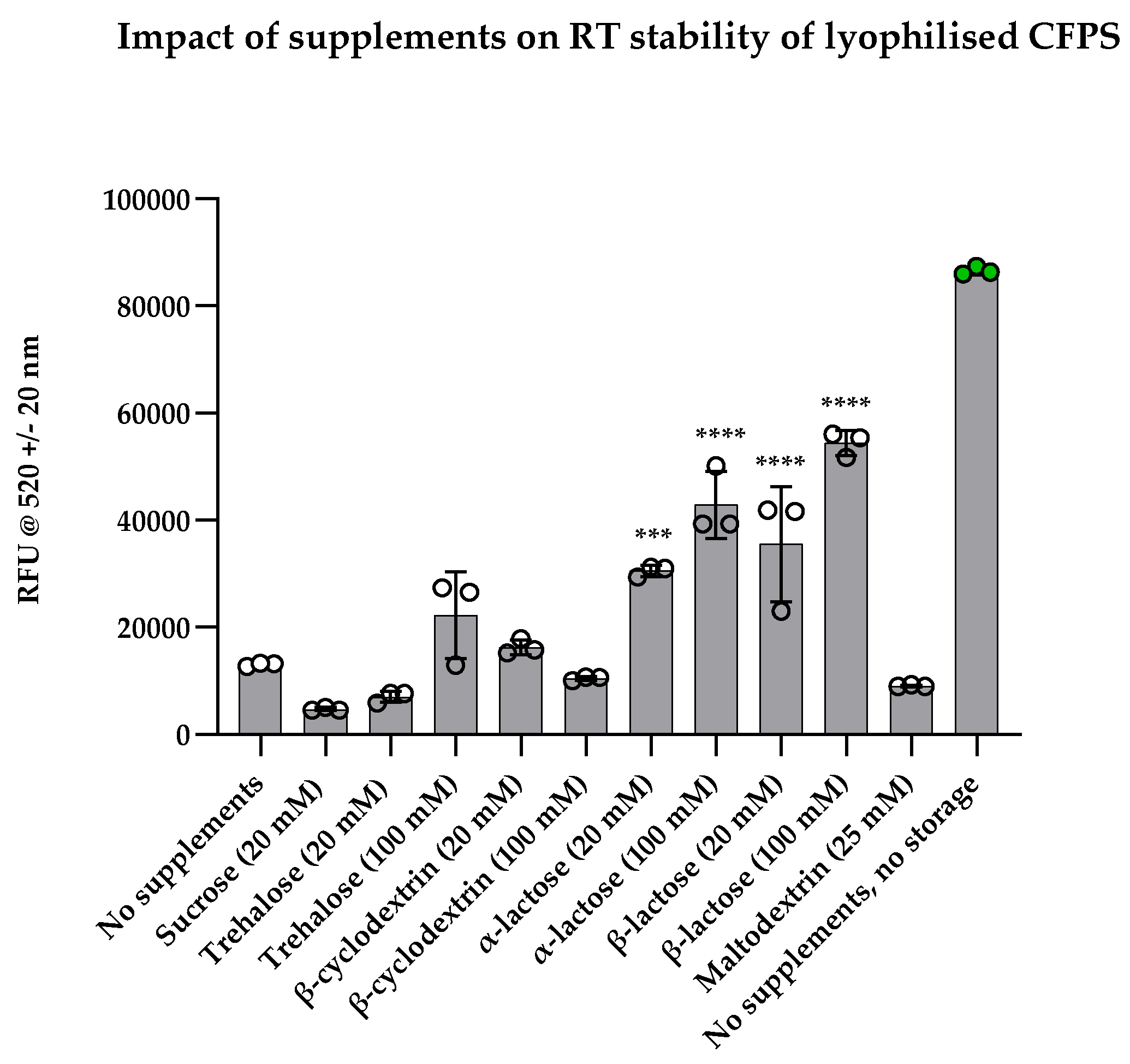

We then utilised a short-term stability screening approach which significantly accelerated the time taken to identify the best CFPS stabilisers without extensive long-term stability studies. Preservation of stability was evaluated by measuring sfGFP fluorescence after rehydrating supplemented reactions following five days of storage at RT, where a fresh CFPS reaction without any supplements or storage served as a positive control. Sucrose was chosen for short-term stability testing despite significant reduction in yield (in

Figure 4, a), owing to its stability conferring properties previously reported in literature [

16]. The addition of sucrose, trehalose, β-cyclodextrin, and maltodextrin had no significant difference when compared with unsupplemented reactions (

Figure 5). On the other hand, lactose had significantly higher stabilising properties. When preserved with 20 mM α-lactose, activity of CFPS was significantly higher than unsupplemented CFPS (p = 0.0005). Higher concentration of α-lactose (100 mM) further increased activity significantly (p < 0.0001). Both 20 mM and 100 mM β-lactose significantly preserved CFPS activity (p < 0.0001). The mean fluorescence values for reactions preserved with 20 mM α-lactose was lower than that of β-lactose and similarly, 100 mM α-lactose was lower than that of β-lactose. This difference perhaps arises from higher solubility and higher compaction of β-lactose (due to the presence of more spherical particles and a higher degree of fragmentation). Alternatively, α-lactose may be spatially repulsing proteins in the cell-free extract due to steric hindrance caused by the secondary hydroxyl group in its chemical structure.

Collectively, these findings led to the identification of β-lactose as an ideal candidate for short-term preservation of lyophilised CFPS. However, the lack of preservation observed in sucrose and maltodextrin-supplemented reactions were not in agreement with previously reported findings [

16]. Warfel et al. found that maltodextrin and sucrose enhanced CFPS stability over 4 weeks at 37°C when supplemented with three concentrations: 30 mg/mL, 60 mg/mL and 100 mg/mL, however, lactose was not tested [

16]. These contradictions suggest that optimisation of lyoprotectants and cryoprotectants should perhaps be optimised for each unique CFPS system, akin to the differences in optimal glutamate concentrations reported between groups working on similar CFPS systems.

3.5. DoE Strategy Enables the Identification of Combinations of Protectants That Enhance Room-Temperature Stability of Lyophilised Cell-Free System

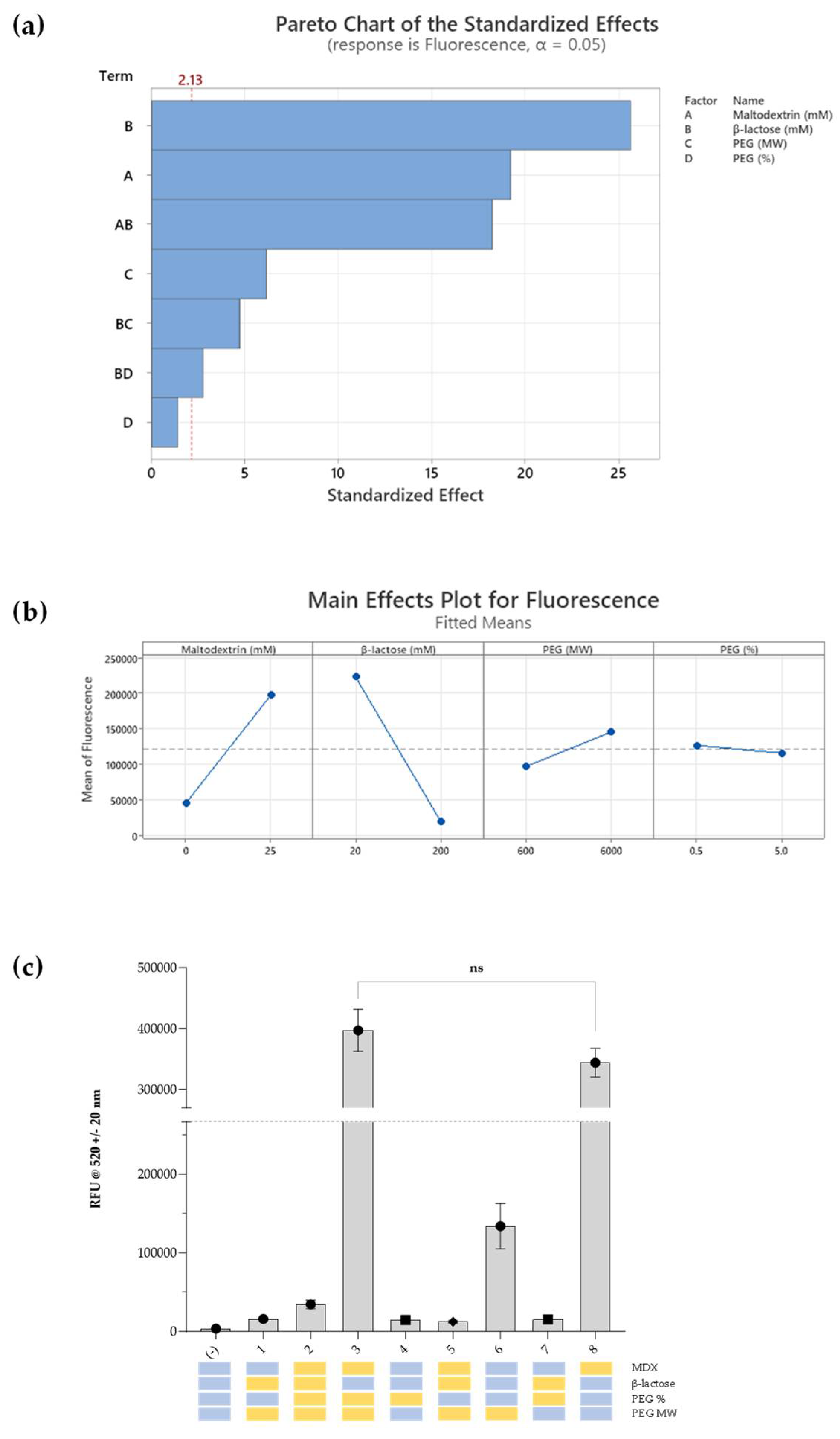

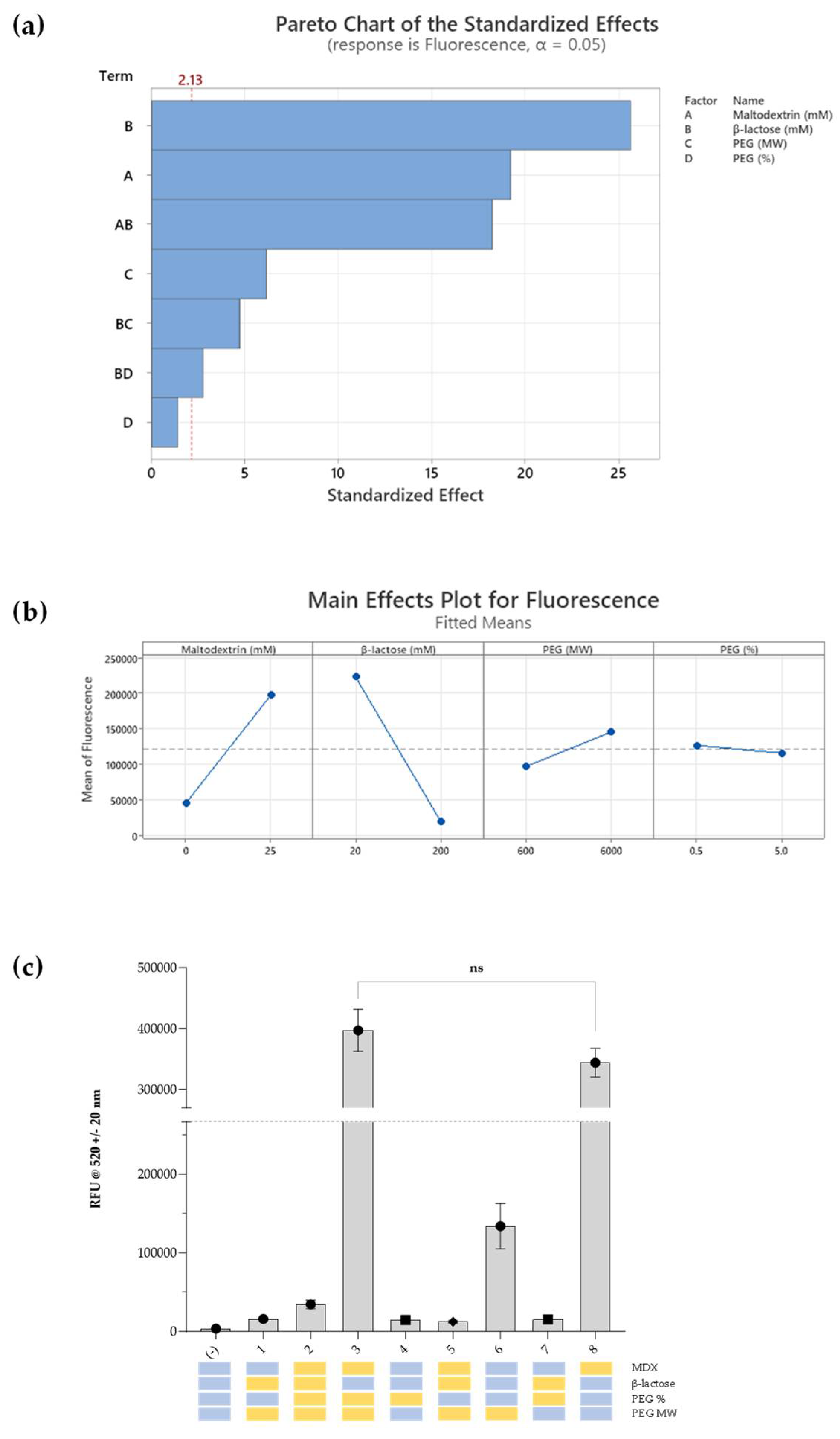

Sugars clearly play an important role in stabilising cell-free components at room temperature and improving CFPS yields, based on the one-factor-at-a-time screening approach employed so far. However, their combinatorial effects and impact of molecular crowding are still unknown. Based on yield-improving effects of maltodextrin (

Figure 4, f) and stability conferring properties of β-lactose (

Figure 5), we hypothesised that their combinatorial effect may lead to longer-term CFPS stability. Therefore, we selected four main factors: MDX, β-lactose, PEG % and PEG molecular weight (MW) and utilised a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach to investigate their effects on the stability and productivity of CFPS. This approach was adopted to systematically investigate the effects of interactions between factors and a two-level design was initially adopted to minimise sample size while maintaining a sufficient evaluation of the factors in just eight experimental runs, plus a control group with no additives (Table 2).

Table 2.

DoE experimental set-up consisting of four factors (maltodextrin; MDX, β-lactose, PEG % and PEG molecular weight; MW) each with two levels (low/high/presence/absence; low/absence highlighted in blue and high/presence highlighted in orange). A formulation without any of the additives was employed as a control run.

Table 2.

DoE experimental set-up consisting of four factors (maltodextrin; MDX, β-lactose, PEG % and PEG molecular weight; MW) each with two levels (low/high/presence/absence; low/absence highlighted in blue and high/presence highlighted in orange). A formulation without any of the additives was employed as a control run.

Eight DoE sample groups were applied using factorial regression modelling to endpoint sfGFP fluorescence after rehydration following RT storage for five days (

Figure 6). A substantial positive impact on sfGFP synthesis was evident with the addition of maltodextrin (coefficient: 13125 [p < 0.05];

Figure 6, a & b). Similarly, lower concentrations of β-lactose exhibited a significant increase in sfGFP fluorescence (coefficient: −220.4 [p < 0.05]), and formulations containing high molecular weight PEG demonstrated a smaller yet statistically significant fluorescence increase (coefficient: 17.47 [p < 0.05]). The percentage of PEG, however, did not yield a statistically significant impact on fluorescence (

Figure 6, a). A notable interaction was observed between MDX and low β-lactose concentrations (coefficient: −64.09 [p < 0.05]). The goodness of fit for the model was assessed through standard deviation of residuals and R2 values. The model demonstrated high explanatory power (R2 = 99.00%) with adjusted and predicted R2 values of 98.53% and 97.75% respectively and the model exhibited overall significance (F value = 212.15, p < 0.05).

Our analyses facilitated the discovery of two high-performing formulations, both featuring MDX (25 mM) and low concentrations of β-lactose (20 mM) (

Figure 6, c). These formulations not only exhibited increased short-term stability, retaining full stability for five days, but also demonstrated increased sfGFP production when compared to fresh CFPS without these additives. This was thought to be a positive consequence of the yield-enhancing properties of MDX, and stability-enhancing properties of β-lactose seen in our previous studies. The role of PEG and its corresponding molecular weight was not clear, however, does not seem to be as critical as MDX and β-lactose, since no significant difference was detected between the two high-performing formulations (

Figure 6, c). Their roles could potentially be uncovered through further experimental designs with multiple levels for each factor.

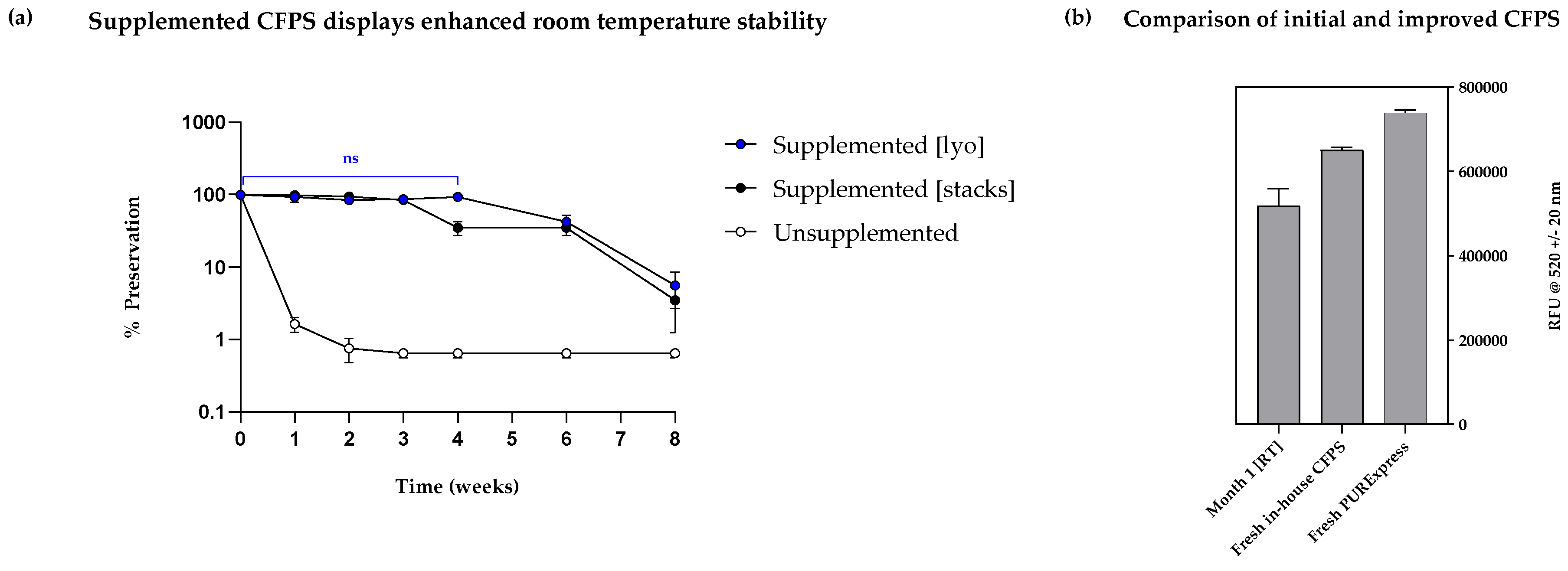

To validate the suitability of the high-performing formulations for sustained room temperature storage, a comprehensive long-term study was next undertaken. Formulation #3 (25 mM MDX, 20 mM β-lactose and 5% PEG 6000) was chosen owing to its highest mean fluorescence and significantly similar outcome to formulation #8 (25 mM MDX, 20 mM β-lactose and 0.5% PEG 600). The experimental set-up for the long-term stability study was similar to the short-term studies, with the exception of several samples prepared for timed data points up to 2 months. Furthermore, preservation of CFPS was tested on two formats, namely, lyophilised pellets and cellulose stacks (Whatman number 5 filter paper) to evaluate long-term applicability of the two systems. The experimental samples contained formulation #3 and this was tested alongside an unsupplemented sample and a negative control for each format.

Firstly, a highly fluorescent signal was observed in the lyophilised reactions containing formulation #3, which was sustained from week 0 to week 4. No significant differences were detected in weekly time points from week 0 to week 4, indicating that 100% stability was achieved for one month (Turkeys multiple comparisons test p = 0.8101;

Figure 7, a). Secondly, samples preserved with formulation #3 on cellulose dropped from 100% to > 80% preservation by week 3 and further decreased to ~ 40% by week 4. Although this result still indicates significantly higher preservation when compared to unsupplemented reactions which dropped to near 0% preservation by week 1, lyophilised pellets were found to preserve CFPS better than cellulose stacks for one month. However, by week 6, lyophilised pellets and cellulose stacks had significantly similar rates of preservation (< 50%) which both dropped to inactive levels by week 8. Collectively, there has been a significant increase in the stability of our CFPS system from < 1 week to 1+ months, which offers a promising solution for longer utilisation of CFPS on both lyophilised pellets and cellulose stacks. The capabilities of this system could be further increased by storage under vacuum, but the applications for our system are inclusive of transport to extreme environments such as space and deep-sea vehicles where this may not be feasible. The DoE approach we have undertaken serves as an efficient initial screening design. If stability beyond one to two months is required, further improvements can be made by executing further DoEs – incorporating generous sample size and a multi-factorial approach can facilitate better coverage of concentrations, especially for factors such as MDX where only presence or absence was tested.

Whilst the observed output from lyophilised pellets preserved with the new formulation was lower than both fresh in-house and PURExpress® reactions, the stability and yield were both substantially higher than what was previously observed in unprotected CFPS (

Figure 7, b). This implies that the newly identified formulation functions both as a lyoprotectant as well as a stabiliser, minimising damage arising from shear forces, light and heat. This systematic approach, guided by DoE, could be used to further advance our understanding of the interplay between additives and CFPS yield and further optimise formulations with improved stability and productivity. Due to the simplicity of the design used, this approach could be easily adapted by other groups to investigate a larger number of factors to further optimise reaction formulation, where stability is of interest. Finally, the cost of our reaction was found to be five times lower than that of PURExpress®, making our system more cost-effective and affordable (

Supplementary Table S1). The low-cost improves accessibility of the technology and the products that are synthesised as a result - the cost of distribution can be further discounted as the system does not require cold storage for at least one month. Collectively, these attributes make the system highly suitable for applications in low-resource environments. With further improvements to stability, applications in extreme environments are hoped to be realised.

4. Conclusions

We illustrated an optimised bacterial CFPS system for high-level expression of sfGFP, comparable to highly efficient commercial systems such as PURExpress®. Lyophilised pellets and cellulose stack formats were conceptualised for flexible implementation of CFPS in resource-scarce environments, where shelf-life and stability of the system was found to be poor. Our strategy of initial screening followed by a minimalistic design of experiments promoted the discovery of formulations with β-lactose and maltodextrin that enhanced sfGFP expression even after five days of room temperature storage when compared to fresh CFPS with no storage. Long-term stability studies revealed 100% preservation of lyophilised CFPS containing this formulation for up to one month, with cellulose stacks displaying > 80%. Thus, we conclude that lyophilised and paper-based systems preserved with the reported formulation contain promising potential for on-demand biomanufacturing and remote biosensing. The success of the formulation underscores the potential of minimalist design of experiments as a powerful tool in optimising and tailoring additives for CFPS systems to enhance productivity and stability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org. Figure S. 1 (a): Growth curve of BL21 Star (DE3) – pAR1219 compared with BL21 Star (DE3) shown with and without IPTG induction (n = 6); (b) SDS-Page analysis of BL21 Star (DE3) (top) and BL21 Star (DE3)-pAR1219 (bottom). Both sol-uble and insoluble fractions were collected in the following times: 0 hr sample taken before induction; 2 hr, 5 hr and 24 hr samples taken after those hours of induction respectively. ‘Lad’ indicates molecular ladder. Arrow indicates expected size of T7 RNA polymerase. Induced samples are labelled ‘I’ and soluble sample are highlighted within a grey box. Figure S. 2: (a) Experimental set up for turbidimetric growth analysis of BL21 Star (DE3) – pAR1219. Each circle indi-cates 1 flask. BL21 Star (DE3) - pAR1219 growth curves at (a) 25°C, (b) 30°C and (c) 37°C respectively. Grey dotted line indicates time of induction and error bars are smaller than data points, where they are not visible (n = 9; Data are shown as mean ± SD. Figure S. 3: SDS-Page analysis of (a) soluble and (b) insoluble BL21 Star (DE3)-pAR1219 cell extract obtained from cells grown at 25°C and induced using varied concentrations of IPTG (0 – 1 mM IPTG). ‘Lad’ indicates molecular ladder. Figure S. 4: SDS-Page analysis of (a) soluble and (b) insoluble BL21 Star (DE3)-pAR1219 cell extract obtained from cells grown at 30°C and induced using varied concentrations of IPTG (0 – 1 mM IPTG). Lad’ indicates molecular ladder. Figure S. 5: SDS-Page analysis of (a) soluble and (b) insoluble BL21 Star (DE3)-pAR1219 cell extract obtained from cells grown at 37°C and induced using varied concentrations of IPTG (0 mM – 1 mM IPTG). Lad’ indicates molecular ladder. Table S 1: Cost breakdown of the reaction components used in this work. Cost per reaction was calculated from price/litre based on value of individually purchased goods. In-house CFPS reactions costed 58p per reaction. Table S 2: Cost per litre of CFPS and cost per reaction (50 µl) for in-house CFPS

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tejasvi Shivakumar, Valentine Anyanwu and Philip M. Williams; Data curation, Tejasvi Shivakumar; Formal analysis, Tejasvi Shivakumar; Funding acquisition, Philip M. Williams; Investigation, Tejasvi Shivakumar, Joshua Clark and Alice Goode; Methodology, Tejasvi Shivakumar; Project administration, Philip M. Williams; Resources, Philip M. Williams; Supervision, Valentine Anyanwu and Philip M. Williams; Validation, Tejasvi Shivakumar and Valentine Anyanwu; Visualization, Tejasvi Shivakumar; Writing – original draft, Tejasvi Shivakumar; Writing – review & editing, Tejasvi Shivakumar, Joshua Clark, Alice Goode and Philip M. Williams.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kate Adamala from the University of Minnesota for devising the paper stack configuration, Michael Jewett and Katherine Warfel, now at Stanford University, and Nigel Savage from the European Space Agency for helpful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ezure, T.; Suzuki, T.; Higashide, S.; Shintani, E.; Endo, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Shikata, M.; Ito, M.; Tanimizu, K.; Nishimura, O. Cell-free protein synthesis system prepared from insect cells by freeze-thawing. Biotechnol Prog 2006, 22(6), 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikami, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Masutani, M.; Yokoyama, S.; Imataka, H. A human cell-derived in vitro coupled transcription/translation system optimized for production of recombinant proteins. Protein Expr Purif 2008, 62(2), 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goering, A. W.; Li, J.; McClure, R. A.; Thomson, R. J.; Jewett, M. C.; Kelleher, N. L. In Vitro Reconstruction of Nonribosomal Peptide Biosynthesis Directly from DNA Using Cell-Free Protein Synthesis. ACS Synth Biol 2017, 6(1), 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E. J.; Ling, G. S. Battlefield medicine: paradigm shift for pharmaceuticals manufacturing. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol 2014, 68(4), 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiga, R.; Al-adhami, M.; Andar, A.; Borhani, S.; Brown, S.; Burgenson, D.; Cooper, M. A.; Deldari, S.; Frey, D. D.; Ge, X.; et al. Point-of-care production of therapeutic proteins of good-manufacturing-practice quality. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2018, 2(9), 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, J. C.; Jaroentomeechai, T.; Moeller, T. D.; Hershewe, J. M.; Warfel, K. F.; Moricz, B. S.; Martini, A. M.; Dubner, R. S.; Hsu, K. J.; Stevenson, T. C.; et al. On-demand biomanufacturing of protective conjugate vaccines. Sci Adv 2021, 7 (6). [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Wang, L.; Zang, L.; Wang, Q.; Qi, D.; Dai, Z. On-demand biomanufacturing through synthetic biology approach. Materials Today Bio 2023, 18, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardee, K.; Slomovic, S.; Nguyen, P. Q.; Lee, J. W.; Donghia, N.; Burrill, D.; Ferrante, T.; McSorley, F. R.; Furuta, Y.; Vernet, A.; et al. Portable, On-Demand Biomolecular Manufacturing. Cell 2016, 167 (1), 248-259.e212. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, A. S.; Smith, M. T.; Bennett, A. M.; Williams, J. B.; Pitt, W. G.; Bundy, B. C. Cell-free protein synthesis of a cytotoxic cancer therapeutic: Onconase production and a just-add-water cell-free system. Biotechnol J 2016, 11(2), 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorio, N. E.; Kao, W. Y.; Williams, L. C.; Hight, C. M.; Patel, P.; Watts, K. R.; Oza, J. P. Unlocking Applications of Cell-Free Biotechnology through Enhanced Shelf Life and Productivity of E. coli Extracts. ACS Synthetic Biology 2020, 9(4), 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardee, K.; Green, A. A.; Ferrante, T.; Cameron, D. E.; DaleyKeyser, A.; Yin, P.; Collins, J. J. Paper-based synthetic gene networks. Cell 2014, 159(4), 940–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, N.; Bouchard, A.; Hofland, G. W.; Witkamp, G. J.; Crommelin, D. J.; Jiskoot, W. Distinct effects of sucrose and trehalose on protein stability during supercritical fluid drying and freeze-drying. Eur J Pharm Sci 2006, 27(4), 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brom, J. A.; Petrikis, R. G.; Pielak, G. J. How Sugars Protect Dry Protein Structure. Biochemistry 2023, 62(5), 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M. T.; Berkheimer, S. D.; Werner, C. J.; Bundy, B. C. Lyophilized Escherichia coli-based cell-free systems for robust, high-density, long-term storage. Biotechniques 2014, 56(4), 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Ding, X.; Lu, Y. Development of a robust Escherichia coli-based cell-free protein synthesis application platform. Biochem Eng J 2021, 165, 107830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfel, K. F.; Williams, A.; Wong, D. A.; Sobol, S. E.; Desai, P.; Li, J.; Chang, Y. F.; DeLisa, M. P.; Karim, A. S.; Jewett, M. C. A Low-Cost, Thermostable, Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Platform for On-Demand Production of Conjugate Vaccines. ACS Synth Biol 2023, 12(1), 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spice, A. J.; Aw, R.; Bracewell, D. G.; Polizzi, K. M. Improving the reaction mix of a Pichia pastoris cell-free system using a design of experiments approach to minimise experimental effort. Synth Syst Biotechnol 2020, 5(3), 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au - Levine, M. Z.; Au - Gregorio, N. E.; Au - Jewett, M. C.; Au - Watts, K. R.; Au - Oza, J. P. Escherichia coli-Based Cell-Free Protein Synthesis: Protocols for a robust, flexible, and accessible platform technology. JoVE 2019, (144), e58882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krinsky, N.; Kaduri, M.; Shainsky-Roitman, J.; Goldfeder, M.; Ivanir, E.; Benhar, I.; Shoham, Y.; Schroeder, A. A Simple and Rapid Method for Preparing a Cell-Free Bacterial Lysate for Protein Synthesis. PLOS ONE 2016, 11(10), e0165137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Copeland, C. E.; Padumane, S. R.; Kwon, Y. C. A Crude Extract Preparation and Optimization from a Genomically Engineered Escherichia coli for the Cell-Free Protein Synthesis System: Practical Laboratory Guideline. Methods Protoc 2019, 2 (3). [CrossRef]

- Dopp, J. L.; Jo, Y. R.; Reuel, N. F. Methods to reduce variability in E. Coli-based cell-free protein expression experiments. Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology 2019, 4 (4), 204-211. [CrossRef]

- Levine, M. Z.; So, B.; Mullin, A. C.; Watts, K. R.; Oza, J. P. Redesigned upstream processing enables a 24-hour workflow from E. coli cells to cell-free protein synthesis. bioRxiv 2019, 729699. [CrossRef]

- Jewett, M. C.; Miller, M. L.; Chen, Y.; Swartz, J. R. Continued protein synthesis at low [ATP] and [GTP] enables cell adaptation during energy limitation. J Bacteriol 2009, 191(3), 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, L.; Yang, D. The Protection Role of Magnesium Ions on Coupled Transcription and Translation in Lyophilized Cell-Free System. ACS Synth Biol 2020, 9(4), 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A. S.; Bernier, C. R.; Hsiao, C.; Okafor, C. D.; Tannenbaum, E.; Stern, J.; Gaucher, E.; Schneider, D.; Hud, N. V.; Harvey, S. C.; et al. RNA-magnesium-protein interactions in large ribosomal subunit. J Phys Chem B 2012, 116(28), 8113–8120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. W.; Kim, D. M.; Choi, C. Y. Rapid production of milligram quantities of proteins in a batch cell-free protein synthesis system. J Biotechnol 2006, 124(2), 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, A. D.; Kelley-Loughnane, N.; Lucks, J. B.; Jewett, M. C. Deconstructing Cell-Free Extract Preparation for in Vitro Activation of Transcriptional Genetic Circuitry. ACS Synth Biol 2019, 8(2), 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, A. M.; Jan, E.; Sarnow, P. Initiation factor-independent translation mediated by the hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site. Rna 2006, 12(5), 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, V. H.; Greene, J. M.; Sengupta, A. M.; Sontag, E. D. Translation inhibition and resource balance in the TX-TL cell-free gene expression system. Synth Biol (Oxf) 2017, 2(1), ysx005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubay, G. In vitro synthesis of protein in microbial systems. Annu Rev Genet 1973, 7, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubay, G. The isolation and properties of CAP, the catabolite gene activator. Methods Enzymol 1980, 65(1), 856–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Inoue, A.; Tomari, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Yokogawa, T.; Nishikawa, K.; Ueda, T. Cell-free translation reconstituted with purified components. Nature Biotechnology 2001, 19(8), 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Lyophilization and development of solid protein pharmaceuticals. Int J Pharm 2000, 203 (1-2), 1-60. [CrossRef]

- Kasper, J. C.; Winter, G.; Friess, W. Recent advances and further challenges in lyophilization. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2013, 85(2), 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Ren, G.-y.; Duan, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, W.-C.; Ang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Ren, X. A comprehensive review on stability of therapeutic proteins treated by freeze-drying: induced stresses and stabilization mechanisms involved in processing. Drying Technology 2022, 40, 3373–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, K. M.; Hunt, J. P.; Wilkerson, J. W.; Funk, P. J.; Swensen, R. L.; Carver, W. C.; Christian, M. L.; Bundy, B. C. Endotoxin-Free E. coli-Based Cell-Free Protein Synthesis: Pre-Expression Endotoxin Removal Approaches for on-Demand Cancer Therapeutic Production. Biotechnol J 2019, 14 (3), e1800271. [CrossRef]

- Des Soye, B. J.; Gerbasi, V. R.; Thomas, P. M.; Kelleher, N. L.; Jewett, M. C. A Highly Productive, One-Pot Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Platform Based on Genomically Recoded Escherichia coli. Cell Chem Biol 2019, 26 (12), 1743-1754.e1749. [CrossRef]

- Merivaara, A.; Zini, J.; Koivunotko, E.; Valkonen, S.; Korhonen, O.; Fernandes, F. M.; Yliperttula, M. Preservation of biomaterials and cells by freeze-drying: Change of paradigm. J Control Release 2021, 336, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräwe, A.; Dreyer, A.; Vornholt, T.; Barteczko, U.; Buchholz, L.; Drews, G.; Ho, U. L.; Jackowski, M. E.; Kracht, M.; Lüders, J.; et al. A paper-based, cell-free biosensor system for the detection of heavy metals and date rape drugs. PLoS One 2019, 14(3), e0210940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Hua, R.; Xing, Y.; Lu, Y. Portable environment-signal detection biosensors with cell-free synthetic biosystems. RSC Advances 2020, 10 (64), 39261-39265. [CrossRef]

- Patkar, A. Y.; Bowen, B. D.; Piret, J. M. Protein adsorption in polysulfone hollow fiber bioreactors used for serum-free mammalian cell culture. Biotechnol Bioeng 1993, 42(9), 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cui, Y.; Cao, Z.; Ma, S.; Lu, Y. Strategy exploration for developing robust lyophilized cell-free systems. Biotechnology Notes 2021, 2, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karig, D. K.; Bessling, S.; Thielen, P.; Zhang, S.; Wolfe, J. Preservation of protein expression systems at elevated temperatures for portable therapeutic production. J R Soc Interface 2017, 14 (129). [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Chavez, F.; Arce, A.; Adhikari, A.; Vadhin, S.; Pedroza-Garcia, J. A.; Gandini, C.; Ajioka, J. W.; Molloy, J.; Sanchez-Nieto, S.; Varner, J. D.; et al. Constructing Cell-Free Expression Systems for Low-Cost Access. ACS Synth Biol 2022, 11(3), 1114–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. M.; Swartz, J. R. Prolonging cell-free protein synthesis by selective reagent additions. Biotechnol Prog 2000, 16(3), 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. H. P. Cell-free protein synthesis energized by slowly-metabolized maltodextrin. BMC Biotechnology 2009, 9(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J. F.; Chiu, W. S.; Gray, V.; Toale, H.; Tobyn, M.; Wu, Y. Investigation into the degree of variability in the solid-state properties of common pharmaceutical excipients-anhydrous lactose. AAPS PharmSciTech 2010, 11(4), 1552–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(a) Cell-free workflow demonstrating the use of E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) – pAR1219 cells to create cell-free extract, which can then be supplemented with amino acids, DNA, ions and energy to synthesise a protein of choice. (b) Graph showing sfGFP fluorescence from cell-free reactions at varying concentrations of Mg-Glu after 4 hours of incubation; (b) Graph showing sfGFP fluorescence from cell-free reactions at varying concentrations of DNA after 4 hours of incubation. Fluorescence was normalised with negative control reactions (pET20b). (d) A comparison of time course analysis of sfGFP production (mg/mL) in in-house and commercial CFPS systems (PURExpress™ and Promega S30A kit for circular DNA). P value > 0.05 = ns, P < 0.05 = *, P < 0.01 = **, P < 0.001 = *** and P < 0.0001 = ****; experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Figure 1.

(a) Cell-free workflow demonstrating the use of E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) – pAR1219 cells to create cell-free extract, which can then be supplemented with amino acids, DNA, ions and energy to synthesise a protein of choice. (b) Graph showing sfGFP fluorescence from cell-free reactions at varying concentrations of Mg-Glu after 4 hours of incubation; (b) Graph showing sfGFP fluorescence from cell-free reactions at varying concentrations of DNA after 4 hours of incubation. Fluorescence was normalised with negative control reactions (pET20b). (d) A comparison of time course analysis of sfGFP production (mg/mL) in in-house and commercial CFPS systems (PURExpress™ and Promega S30A kit for circular DNA). P value > 0.05 = ns, P < 0.05 = *, P < 0.01 = **, P < 0.001 = *** and P < 0.0001 = ****; experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic of CFPS in lyophilised format; fluorescence was detected following rehydration of lyophilised pellets containing sfGFP DNA (‘sfGFP’) and no template (‘-‘) imaged under a blue light transilluminator. (b) Comparative analysis of endpoint sfGFP signal between freshly prepared and lyophilised CFPS samples normalised to negative control samples. (c) Illustration of the novelty of cellulose stack format. The DNA layer can be easily interchanged for biomanufacturing or biosensing applications and is particularly useful for multiple sensing (e.g. heavy metal contamination) applications using the same sample in the field. (d) Schematic of CFPS on cellulose stacks separated onto three cellulose discs, corresponding to DNA, cell-free extract, and energy/buffer constituents respectively. Fluorescence was detected following rehydration of cellulose stacks containing sfGFP DNA (‘sfGFP’) and no template (‘-‘) imaged under a blue light transilluminator. (e) Comparative analysis of endpoint sfGFP signal following rehydration of lyophilised cellulose stacks on various paper substrates normalised to negative control samples, shown alongside a freshly prepared reaction. P value > 0.05 = ns, P < 0.05 = *, P < 0.01 = **, P < 0.001 = *** and P < 0.0001 = ****; experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic of CFPS in lyophilised format; fluorescence was detected following rehydration of lyophilised pellets containing sfGFP DNA (‘sfGFP’) and no template (‘-‘) imaged under a blue light transilluminator. (b) Comparative analysis of endpoint sfGFP signal between freshly prepared and lyophilised CFPS samples normalised to negative control samples. (c) Illustration of the novelty of cellulose stack format. The DNA layer can be easily interchanged for biomanufacturing or biosensing applications and is particularly useful for multiple sensing (e.g. heavy metal contamination) applications using the same sample in the field. (d) Schematic of CFPS on cellulose stacks separated onto three cellulose discs, corresponding to DNA, cell-free extract, and energy/buffer constituents respectively. Fluorescence was detected following rehydration of cellulose stacks containing sfGFP DNA (‘sfGFP’) and no template (‘-‘) imaged under a blue light transilluminator. (e) Comparative analysis of endpoint sfGFP signal following rehydration of lyophilised cellulose stacks on various paper substrates normalised to negative control samples, shown alongside a freshly prepared reaction. P value > 0.05 = ns, P < 0.05 = *, P < 0.01 = **, P < 0.001 = *** and P < 0.0001 = ****; experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Figure 3.

Stability studies of lytophilised CFPS. (a) Schematic illustrating the experimental plan for a 4-week stability study at a range of temperatures, with readings taken every day per week for samples stored at room temperature (RT). (b) CFPS in lyophilised pellets format after storage for 1 month at 40°C, RT (~ 22°C) and 4°C with data points shown for the first seven days for samples RT (box). sfGFP fluorescence was normalised to negative control (pET20b reactions) and % preservation was calculated by normalising obtained fluorescence values to day 0/week 0 fluorescence values i.e. samples with no storage; experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Figure 3.

Stability studies of lytophilised CFPS. (a) Schematic illustrating the experimental plan for a 4-week stability study at a range of temperatures, with readings taken every day per week for samples stored at room temperature (RT). (b) CFPS in lyophilised pellets format after storage for 1 month at 40°C, RT (~ 22°C) and 4°C with data points shown for the first seven days for samples RT (box). sfGFP fluorescence was normalised to negative control (pET20b reactions) and % preservation was calculated by normalising obtained fluorescence values to day 0/week 0 fluorescence values i.e. samples with no storage; experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Figure 4.

Impact of various supplements on CFPS. Time course analysis showing expression of sfGFP from in-house cell reactions in aqueous format supplemented with (a) sucrose, (b) trehalose, (c) α-lactose, (d) β-lactose, € β-cyclodextrin and (f) maltodextrin, compared with unsupplemented reactions (0 mM) and negative control (‘pET20b +’) at 37°C. Experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Figure 4.

Impact of various supplements on CFPS. Time course analysis showing expression of sfGFP from in-house cell reactions in aqueous format supplemented with (a) sucrose, (b) trehalose, (c) α-lactose, (d) β-lactose, € β-cyclodextrin and (f) maltodextrin, compared with unsupplemented reactions (0 mM) and negative control (‘pET20b +’) at 37°C. Experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Figure 5.

Effect of supplements on short-term stability. Graph shows sfGFP fluorescence following rehydration of lyophilised cell-free pellets with S30A buffer after storage at RT for five days. Experimental samples were normalised to negative control (pET20b+) and shown alongside unsupplemented control (‘no supplements’) and a positive control (‘no supplements, no storage’). Reactions with significantly high stability compared to unsupplemented reactions are indicated with significance values above bars; experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD; P-value > 0.05 = ns, P < 0.05 = *, P < 0.01 = **, P < 0.001 = *** and P < 0.0001 = ****.

Figure 5.

Effect of supplements on short-term stability. Graph shows sfGFP fluorescence following rehydration of lyophilised cell-free pellets with S30A buffer after storage at RT for five days. Experimental samples were normalised to negative control (pET20b+) and shown alongside unsupplemented control (‘no supplements’) and a positive control (‘no supplements, no storage’). Reactions with significantly high stability compared to unsupplemented reactions are indicated with significance values above bars; experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD; P-value > 0.05 = ns, P < 0.05 = *, P < 0.01 = **, P < 0.001 = *** and P < 0.0001 = ****.

Figure 6.

(a) Pareto chart of standardized effects for fluorescence response. This chart illustrates the standardized effects of factors and interactions derived from a factorial regression model on fluorescence. Each bar represents the standardized effect of a specific factor or interaction, arranged in descending order. The cut-off line, (--- 2.13), represents the significance threshold based on α-level = 0.05. Factors and interactions above this line are considered statistically significant (p < 0.05). (b) Main effects for fluorescence plot showcases the impact of individual factors on the fitted means of fluorescence derived from the factorial regression model. Vertical bars indicate the magnitude and direction of the effect for each factor, providing a visual representation of their influence on fluorescence. (c) Short-term stability studies. Graph showing sfGFP fluorescence following rehydration of lyophilised cell-free pellets with S30A buffer after storage at RT for five days. Experimental samples were supplemented with the variables shown below the data points marked in yellow blocks (high concentrations or presence of MDX) and blue blocks (low concentrations and absence of MDX). ‘pET20b+’ corresponds to the negative control, and the positive control (fresh CFPS in aqueous format without storage) is indicated by the grey dotted line (RFU = 27,5000). Experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Figure 6.

(a) Pareto chart of standardized effects for fluorescence response. This chart illustrates the standardized effects of factors and interactions derived from a factorial regression model on fluorescence. Each bar represents the standardized effect of a specific factor or interaction, arranged in descending order. The cut-off line, (--- 2.13), represents the significance threshold based on α-level = 0.05. Factors and interactions above this line are considered statistically significant (p < 0.05). (b) Main effects for fluorescence plot showcases the impact of individual factors on the fitted means of fluorescence derived from the factorial regression model. Vertical bars indicate the magnitude and direction of the effect for each factor, providing a visual representation of their influence on fluorescence. (c) Short-term stability studies. Graph showing sfGFP fluorescence following rehydration of lyophilised cell-free pellets with S30A buffer after storage at RT for five days. Experimental samples were supplemented with the variables shown below the data points marked in yellow blocks (high concentrations or presence of MDX) and blue blocks (low concentrations and absence of MDX). ‘pET20b+’ corresponds to the negative control, and the positive control (fresh CFPS in aqueous format without storage) is indicated by the grey dotted line (RFU = 27,5000). Experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Figure 7.

(a) Two-month stability study investigating the effects of supplements on sample preservation at room temperature both in lyophilised pellet (supplemented [lyo]’) and cellulose stacks (‘supplemented [stacks]’) formats (lyophilised on Whatman number 5 discs) compared with unsupplemented reactions. Supplemented samples were prepared using the standard reaction components, with the addition of the formulation identified from the DoE (25 mM maltodextrin, 20 mM of β-lactose, and 0.5% of 6000 MW PEG). % preservation was calculated by normalising obtained fluorescence values to day 0/week 0 fluorescence values i.e. samples with no storage. (b) Comparison between fresh PURExpress™, fresh in-house CFPS system and rehydrated in-house system supplemented as in (a), stored for 1-month at RT. sfGFP fluorescence was normalised to negative control (pET20b reactions); experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Figure 7.

(a) Two-month stability study investigating the effects of supplements on sample preservation at room temperature both in lyophilised pellet (supplemented [lyo]’) and cellulose stacks (‘supplemented [stacks]’) formats (lyophilised on Whatman number 5 discs) compared with unsupplemented reactions. Supplemented samples were prepared using the standard reaction components, with the addition of the formulation identified from the DoE (25 mM maltodextrin, 20 mM of β-lactose, and 0.5% of 6000 MW PEG). % preservation was calculated by normalising obtained fluorescence values to day 0/week 0 fluorescence values i.e. samples with no storage. (b) Comparison between fresh PURExpress™, fresh in-house CFPS system and rehydrated in-house system supplemented as in (a), stored for 1-month at RT. sfGFP fluorescence was normalised to negative control (pET20b reactions); experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); data are shown as mean ± SD.

Table 1.

Final concentrations of components in CFPS reactions.

Table 1.

Final concentrations of components in CFPS reactions.

| Component |

Final concentration |

Procurement |

|

E. coli cell-free extract (40% v/v) |

40% v/v |

Prepared in-house |

| Energy components master mix |

160 mM HEPES, 4.8 mM ATP sodium salt, 4.8 mM ATP potassium salt, 4.15 mM GTP, 3.2 mM UTP, 3.2 mM CTP, 0.95 mM Coenzyme A, 1.3 mM NAD, 2.5 mM cAMP, 0.27 mM Folinic acid, 3.3 mM Spermidine, 118.7 mM 3-PGA |

Prepared in-house |

| Amino acid mixture |

2.5 mM each |

Prepared in-house |

| Plasmid DNA |

10 nM |

Prepared in-house |

| Magnesium glutamate |

20 mM |

Sigma Aldrich |

| Potassium glutamate |

50 mM |

Sigma Aldrich |

| RNase Inhibitor |

4 units |

Roche |

| Polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG) |

2% |

Sigma Aldrich |

| Nuclease free water |

to 50 μL |

ThermoScientific |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).