Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. NK Cells and PCa

2.1. NK cells: Pathogenesis Significance in PCa

2.1.1. Impaired Proliferation of NK Cells

2.1.2. Decreased Cytotoxicity

2.1.3. Diminished Tumor Infiltration

2.2. NK Cells: Screening/Diagnosis Significance in PCa

2.2.1. Radionuclide Labeling Method

2.2.2. Flow Cytometry and Machine Learning

2.2.3. NK Vue Cytokine Release Method

2.2.4. Secretome Analysis

2.2.5. MICA ELISA

2.2.6. Molecular Profiling

2.3. NK Cells: Prognostic and Predictive Significance in PCa

2.3.1. NK Cells and Prognostic Significance

2.3.2. NK Cells and Predictive Significance

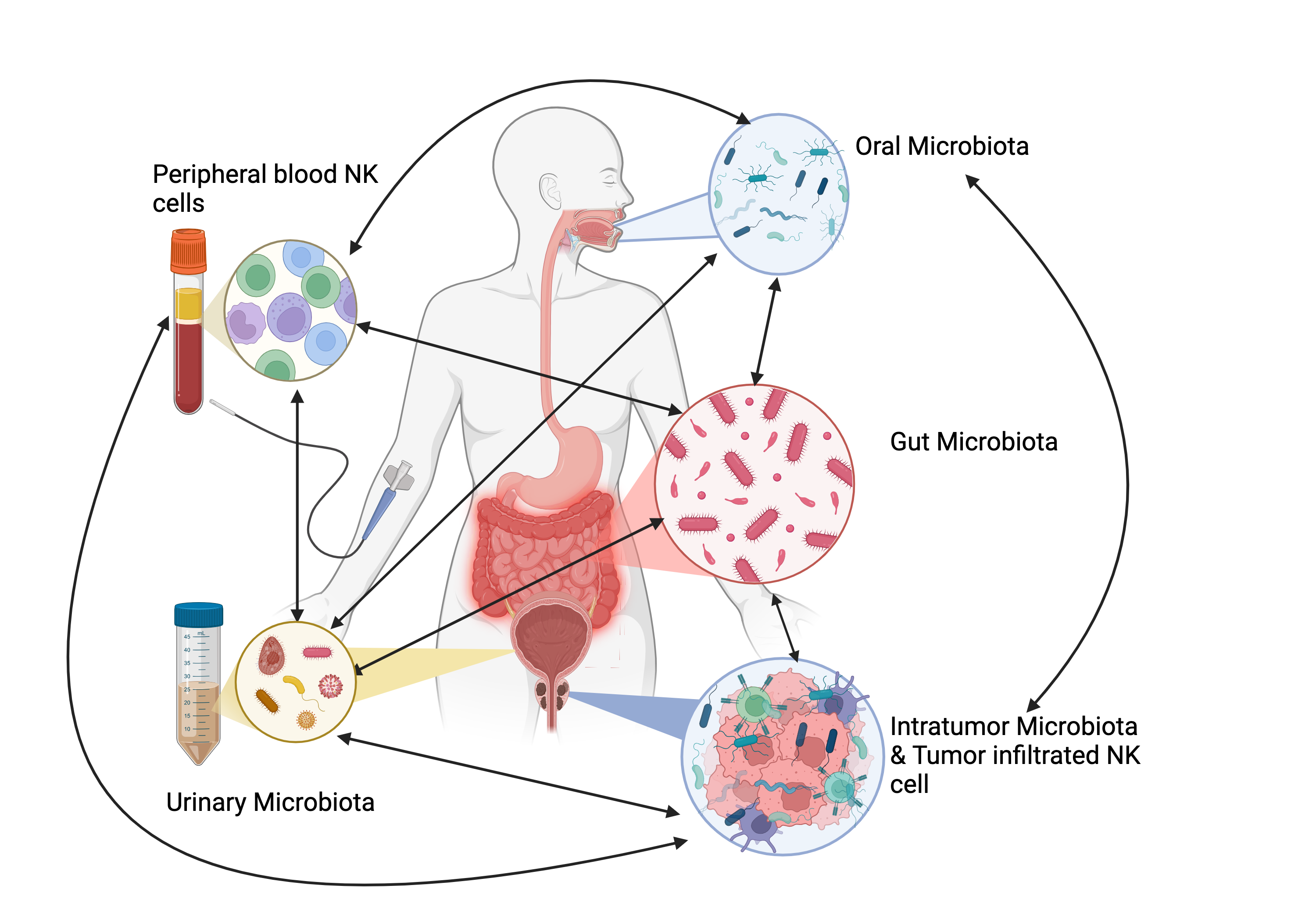

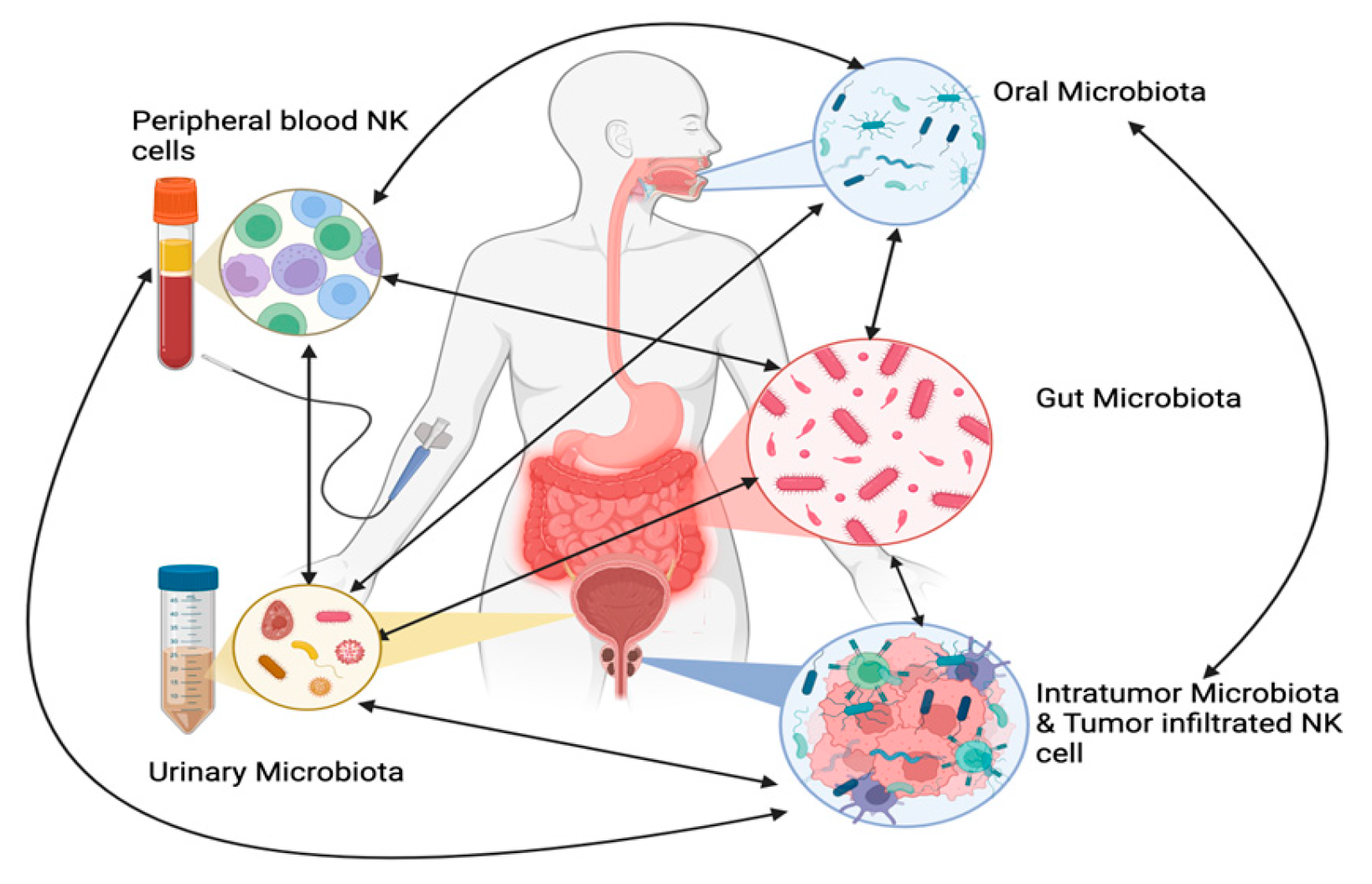

3. Microbiome and PCa

3.1. Oral Microbiota

3.2. Gut Microbiota

3.3. Urinary Microbiota

3.4. Intraprostatic/Intratumoral Microbio

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F., Laversanne, M., Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries.. CA Cancer J Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D. J., Nielsen, M. E., Han, M. & Partin, A. W. Contemporary evaluation of the D’amico risk classification of prostate cancer. Urology 70, 931–935 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Sotosek, S. et al. Comparative study of frequency of different lymphocytes subpopulation in peripheral blood of patients with prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift 123, 718–725 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Neppl-Huber, C. et al. Changes in incidence, survival and mortality of prostate cancer in Europe and the United States in the PSA era: additional diagnoses and avoided deaths. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 23, 1325–1334 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Semjonow, A., Brandt, B., Oberpenning, F., Roth, S. & Hertle, L. Discordance of assay methods creates pitfalls for the interpretation of prostate-specific antigen values 3–16 (1996).

- Schröder, F. H. et al. Early Detection of Prostate Cancer in 2007. European Urology 53, 468–477 (2008).

- Qaseem, A., Barry, M. J., Denberg, T. D., Owens, D. K. & Shekelle, P. Screening for Prostate Cancer: A Guidance Statement From the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine 158, 761–761 (2013).

- Scarpato, K. R. & Albertsen, P. C. Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening Guidelines. Prostate Cancer: Science and Clinical Practice: Second Edition 111–117 (2016).

- Hodge, K. K., Mcneal, J. E. & Stamey, T. A. Ultrasound guided transrectal core biopsies of the palpably abnormal prostate. The Journal of urology 142, 66–70 (1989). [CrossRef]

- Djavan, B. et al. Prospective evaluation of prostate cancer detected on biopsies 1, 2, 3 and 4: when should we stop. The Journal of urology 166, 1679–1683 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Boesen, L. Magnetic resonance imaging-transrectal ultrasound image fusion guidance of prostate biopsies: current status, challenges and future perspectives. Scandinavian Journal of Urology. Taylor and Francis Ltd. 53, 89–96 (2019).

- Graham, J., Baker, M., Macbeth, F. & Titshall, V. Diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer: summary of NICE guidance. (2008). [CrossRef]

- Aragon-Ching, J. B., Williams, K. M. & Gulley, J. L. (2007).

- Patrikidou, A. et al. Who dies from prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Disease 17, 348–352 (2014).

- Koo, K. C. et al. Reduction of the CD16-CD56bright NK cell subset precedes NK cell dysfunction in prostate cancer. PLoS One 8, 1–8 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Choe, B. K., Frost, P., Morrison, M. K. & Rose, N. R. Natural killer cell activity of prostatic cancer patients. Cancer investigation 5, 285–291 (1987).

- Hirz, T. et al. Dissecting the immune suppressive human prostate tumor microenvironment via integrated single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses. Nat Commun 14, 663–663 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Pasero, C. et al. Inherent and Tumor-Driven Immune Tolerance in the Prostate Microenvironment Impairs Natural Killer Cell Antitumor Activity. Cancer research 76, 2153–2165 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Santos, M. F. et al. Comparative analysis of innate immune system function in metastatic breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer patients with circulating tumor cells. Experimental and molecular pathology 96, 367–374 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Stovgaard, E. S., Nielsen, D., Hogdall, E. & Balslev, E. Triple negative breast cancer - prognostic role of immune-related factors: a systematic review. Acta Oncologica 57, 74–82 (2017).

- Abel, A. M., Yang, C., Thakar, M. S. & Malarkannan, S. Natural Killer Cells: Development, Maturation, and Clinical Utilization. Frontiers in Immunology 9 (2018).

- Hu, W., Wang, G., Huang, D., Sui, M. & Xu, Y. Cancer Immunotherapy Based on Natural Killer Cells: Current Progress and New Opportunities. Frontiers in Immunology 10 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Poli, A. et al. CD56bright natural killer (NK) cells: an important NK cell subset. Immunology 126, 458–465 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Gannon, P. O. et al. Characterization of the intra-prostatic immune cell infiltration in androgendeprived prostate cancer patients. Journal of immunological methods 348, 9–17 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Hanna, J. et al. Novel Insights on Human NK Cells’ Immunological Modalities Revealed by Gene Expression Profiling. The Journal of Immunology 173, 6547–6563 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Yu, C., Young, H. A. & Ortaldo, J. R. Characterization of cytokine differential induction of STAT complexes in primary human T and NK cells. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 64, 245–258 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Moretta, A. et al. Activating receptors and coreceptors involved in human natural killer cell mediated cytolysis. Annual review of immunology 19, 197–223 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Nausch, N. & Cerwenka, A. NKG2D ligands in tumor immunity. Oncogene 27, 5944–5958 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, S., Ferry, A., Guedes, J. & Guerra, N. The Paradoxical Role of NKG2D in Cancer Immunity. Frontiers in Immunology 9 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Nigro, C. L. et al. NK-mediated antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity in solid tumors: biological evidence and clinical perspectives. Annals of translational medicine 7, 105–105 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Kasai, M. et al. Brief Definitive Report Direct Evidence that Natural Killer Cells in Nonimmune Spleen Cell Populations Prevent Tumor Growth In Vivo (1979).

- Hood, S. P. et al. Phenotype and Function of Activated Natural Killer Cells From Patients With Prostate Cancer: Patient-Dependent Responses to Priming and IL-2 Activation. Frontiers in Immunology 9 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Zhan, B., Tadao, T. & Totsuhiro, M. Immunohistochemical study of HNK-1 (leu-7) antigen in prostate cancer and its clinical significance. Chin Med J (Engl) 108, 516–537 (1995).

- Heidegger, I. et al. A Systematic Review of the Emerging Role of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer: Will Combination Strategies Improve Efficacy? European urology oncology 4, 745–754 (2020).

- Feng, K., Ren, F. & Wang, X. Association between oral microbiome and seven types of cancers in East Asian population: a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis.. Front Mol Biosci 10, 1327893–1327893 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Salachan, P. V. & Sørensen, K. D. Dysbiotic microbes and how to find them: a review of microbiome profiling in prostate cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 41, 31–31 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. et al. Influence of Intratumor Microbiome on Clinical Outcome and Immune Processes in Prostate Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 12 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Jewett, A. et al. Natural Killer Cells: Diverse Functions in Tumor Immunity and Defects in Pre-neoplastic and Neoplastic Stages of Tumorigenesis. Molecular Therapy Oncolytics 16, 41–52 (2020).https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2019.11.002.

- Fanijavadi, S., Thomassen, M. & Jensen, L. H. (2024).

- Brittenden, J. Natural killer cells and cancer. Cancer 77, 1226–1269 (1996).

- Zhao, S. G. et al. The immune landscape of prostate cancer and nomination of PD-L2 as a potential therapeutic target. J Natl Cancer Inst 111, 301–311 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. et al. Perturbation of NK cell peripheral homeostasis accelerates prostate carcinoma metastasis. J Clin Invest 123, 4410–4432 (2013).

- Liu, X. et al. MiRNA-296-3p-ICAM-1 axis promotes metastasis of prostate cancer by possible enhancing survival of natural killer cell-resistant circulating tumour cells. Cell Death Dis 4, 1–15 (2013).

- Pasero, C. et al. Highly effective NK cells are associated with good prognosis in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Oncotarget 6, 14360–14373 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Morse, M. D. & Mcneel, D. G. Prostate cancer patients on androgen deprivation therapy develop persistent changes in adaptive immune responses. Hum Immunol 71, 496–504 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Singh, J. et al. Levels of plasma cytokine in patients undergoing neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy and external beam radiation therapy for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Ann Transl Med 8, 636–636 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Page, S. T. et al. Effect of medical castration on CD4+ CD25+ T cells, CD8+ T cell IFN-γ expression, and NK cells: A physiological role for testosterone and/or its metabolites. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 290, 856–863 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Dethlefsen, C. et al. Exercise regulates breast cancer cell viability: Systemic training adaptations versus acute exercise responses. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 159, 469–479 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C. M., White, M. J., Goodier, M. R. & Riley, E. M. Functional significance of CD57 Expression on human NK cells and relevance to disease. Frontiers in Immunology 4, 422–422 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Hojan, K. et al. Physical exercise for functional capacity, blood immune function, fatigue, and quality of life in high-risk prostate cancer patients during radiotherapy: A prospective, randomized clinical study. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 52, 489–501 (2016).

- Zheng, W., Ling, S., Cao, Y., Shao, C. & Sun, X. Combined use of NK cells and radiotherapy in the treatment of solid tumors.. Front Immunol 14 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. et al. Docetaxel remodels prostate cancer immune microenvironment and enhances checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Theranostics 12, 4965–79 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, N., Stoner, L., Farajivafa, V. & Hanson, E. D. Exercise training, circulating cytokine levels and immune function in cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 81, 92–104 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Hanson, E. D., Bates, L. C., Moertl, K. & Evans, E. S. Natural Killer Cell Mobilization in Breast and Prostate Cancer Survivors: The Implications of Altered Stress Hormones Following Acute Exercise. Endocrines 2021 2, 121–132. [CrossRef]

- Hanson, E. D., Sakkal, S. & Que, S. Natural killer cell mobilization and egress following acute exercise in men with prostate cancer. Experimental Physiology 105, 1524–1539 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Nieman, D. C. Exercise, infection, and immunity. International Journal of Sports Medicine 15, 131–141 (1994).

- Maria, A. D., Bozzano, F., Cantoni, C. & Moretta, L. Revisiting human natural killer cell subset function revealed cytolytic CD56dimCD16+ NK cells as rapid producers of abundant IFN-γ on activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 728–732 (2011).

- Campbell, J. P. et al. Acute exercise mobilises CD8+ T lymphocytes exhibiting an effector-memory phenotype. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 23, 767–775 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Rooney, B. V. et al. Lymphocytes and monocytes egress peripheral blood within minutes after cessation of steady state exercise: A detailed temporal analysis of leukocyte extravasation. Physiology & Behavior 194, 260–267 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Shephard, R. J. Adhesion molecules, catecholamines and leucocyte redistribution during and following exercise. Sports Med 33, 261–284 (2003).

- Hanson, E. D. et al. Altered stress hormone response following acute exercise during prostate cancer treatment. Scan- dinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 28, 1925–1933 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Galvao, D. A. et al. Endocrine and immune responses to resistance training in prostate cancer patients. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases 11, 160–165 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. P. & Turner, J. E. Debunking the myth of exercise-induced immune suppression: redefining the impact of exercise on immunological health across the lifespan. Frontiers in Immunology 9, 648–648 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kared, H., Martelli, S., Ng, T. P., Pender, S. L. & Larbi, A. CD57 in human natural killer cells and T-lymphocytes 65, 441–452 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Bigley, A. B. et al. Acute exercise preferentially redeploys NK-cells with a highly-differentiated phenotype and aug- ments cytotoxicity against lymphoma and multiple myeloma target cells. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 39, 160–171 (2014).

- Vivier, E. Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science 331, 44–49 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Jaw, J. J., Stutzman, N. C., Zou, Z. & Sun, P. D. Natural killer cell-produced IFN-γ and TNF-α induce target cell cytolysis through up-regulation of ICAM-1. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 91, 299–309 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. et al. (2018).

- Gallazzi, M. et al. Prostate Cancer Peripheral Blood NK Cells Show Enhanced CD9, CD49a, CXCR4, CXCL8, MMP-9 Production and Secrete Monocyte-Recruiting and Polarizing Factors. Frontiers in Immunology 11 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Lundholm, M. et al. Prostate Tumor-Derived Exosomes Down-Regulate NKG2D Expression on Natural Killer Cells and CD8+ T Cells: Mechanism of Immune Evasion. PLoS ONE 9, 108925–108925 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Marumo, K., Ikeuchi, K., Baba, S., Ueno, M. & Tazaki, H. Natural killer cell activity and recycling capacity of natural killer cells in patients with carcinoma of the prostate.. The Keio journal of medicine 38, 27–35 (1989). [CrossRef]

- Lahat, N., Levin, A. B., Moskovitz, R. D. & B. The relationship between clinical stage, natural killer activity and related immunological parameters in adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 28, 208– 212 (1989).

- Wu, J. D. et al. Prevalent expression of the immunostimulatory MHC class I chain-related molecule is counteracted by shedding in prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Investigation 114, 560–568 (2004). [CrossRef]

- López-Vázquez, A. et al. Protective effect of the HLA-Bw4I80 epitope and the killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DS1 gene against the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. The Journal of infectious diseases 192, 162–165 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Middleton, D. et al. Analysis of KIR gene frequencies in HLA class I characterised bladder, colorectal and laryngeal tumours. Tissue antigens 69, 220–226 (2007).

- Portela, P. et al. Analysis of KIR gene frequencies and HLA class I genotypes in prostate cancer and control group.International Journal of Immunogenetics 39, 423–428 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. et al. Natural killer cells suppress enzalutamide resistance and cell invasion in the castration resistant prostate cancer via targeting the androgen receptor splicing variant 7 (ARv7).. Cancer letters 398, 62–69 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kantoff, P. W. et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 363, 411–433 (2010).

- Jähnisch, H. et al. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy for prostate cancer. Clin Dev Immunol 517493–517493 (2010).

- Wirth, M., Schmitz-Dräger, B. J. & Ackermann, R. Functional properties of natural killer cells in carcinoma of the prostate. The Journal of urology 133, 973–978 (1985). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H. et al. Destructive impact of t-lymphocytes, NK and mast cells on basal cell layers: implications for tumor invasion. BMC Cancer 13, 258–258 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Pello, O. M. et al. Role of c-MYC in alternative activation of human macrophages and tumor-associated macrophage biology. Blood 119, 411–432 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Comito, G. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and M2-polarized macrophages synergize during prostate carcinoma progression. Oncogene.

- Dufresne, S. Exercise training improves radiotherapy efficiency in a murine model of prostate cancer. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 34, 4984–4996 (2020).

- Barkin, J., Rodriguez-Suarez, R. & Betito, K. Association between natural killer cell activity and prostate cancer: a pilot study. Can J Urol 24, 8708–8721 (2017).

- Tarle, M., Kraljic’, I. & Kaštelan, M. Comparison between NK cell activity and prostate cancer stage and grade in untreated patients: correlation with tumor markers and hormonal serotest data. Urological Research 21, 17–21 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Hood, S. P. et al. Identifying prostate cancer and its clinical risk in asymptomatic men using machine learning of high dimensional peripheral blood flow cytometric natural killer cell subset phenotyping data. 9 (2020).

- Tae, B. S. et al. Can natural killer cell activity help screen patients requiring a biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer? International Brazilian Journal of Urology : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology 46, 244–252 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Vidal, A. C. et al. Natural killer cell activity and prostate cancer risk in veteran men undergoing prostate biopsy. Cancer epidemiology 62, 101578–101578 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Barkin, J., Rodriguez-Suarez, R. & Betito, K. immunotherapies can provide opportunities for evaluating human immune responses. neoadjuvant trials with jnci. oxfordjournals.org JNCI | Article 8, 8708–8721 (2017).

- Song, W. et al. The clinical usefulness of natural killer cell activity in patients with suspected or diagnosed prostate cancer: an observational cross-sectional study. OncoTargets and therapy 2018, 3883–3889 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Coca, S. et al. The prognostic significance of intratumoral natural killer cells in patients with colerectal carcinoma. Cancer 79, 2320–2328 (1997).

- Zorko, N. A., Makovec, A. & Elliott, A. Natural Killer Cell Infiltration in Prostate Cancers Predict Improved Patient Outcomes. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis (2024). [CrossRef]

- Tuong, Z., Kelvin et al. Resolving the immune landscape of human prostate at a single-cell level in health and cancer. Cell Reports 37. [CrossRef]

- Vranova, J. et al. The evolution of rectal and urinary toxicity and immune response in prostate cancer patients treated with two three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy techniques. Radiation Oncology 6, 87–87 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. et al. Lower postoperative natural killer cell activity is associated with positive surgical margins after radical prostatectomy. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi 119, 1673–1683 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Blomgren, H. et al. Natural killer activity in peripheral lymphocyte population following local radiation therapy. Acta radiologica. Oncology 19, 139–143 (1980). [CrossRef]

- Jochems, C. et al. A combination trial of vaccine plus ipilimumab in metastatic castrationresistant prostate cancer patients: immune correlates. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 63, 407–418 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J. et al. Elevated IL-8, TNF-α, and MCP-1 in men with metastatic prostate cancer starting androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) are associated with shorter time to castration-resistance and overall survival. The Prostate 74, 820–828 (2014).

- Hansen, T. et al. Correlation between natural killer cell activity and treatment effect in patients with disseminated cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 36, 12029–12029 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Yirga, A. et al. Monocyte counts and prostate cancer outcomes in white and black men: results from the SEARCH database. Cancer Causes Control CCC 32, 189–97 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T. et al. Serum monocyte fraction of white blood cells is increased in patients with high Gleason score prostate cancer. Oncotarget 8, 35255–61 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Shigeta, K. et al. High absolute monocyte count predicts poor clinical outcome in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with docetaxel chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 23, 4115–4137 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Angel Charles, Ryan M. Thomas,The Influence of the microbiome on the innate immune microenvironment of solid tumors, Neoplasia, Volume 37, 2023, 100878, ISSN 1476-5586. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L. E., Olson, B. M. & Mcneel, D. G. Pretreatment antigen-specific immunity and regulation - association with subsequent immune response to anti-tumor DNA vaccination. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer 5 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Madan, R. A. et al. Clinical and immunologic impact of short-course enzalutamide alone and with immunotherapy in non-metastatic castration sensitive prostate cancer. J Immunother. Cancer 9 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. J., Park, M., Choi, A. & Yoo, S. Microbiome and Prostate Cancer: Emerging Diagnostic and Therapeutic Opportunities. Pharmaceuticals 2024. [CrossRef]

- Inamura, K. Oral-Gut Microbiome Crosstalk in Cancer. Cancers 2023, 3396–3396. [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Y. et al. Oral-Gut Microbiome Axis in Gastrointestinal Disease and Cancer. Cancers 2124–2124 (2021).

- Chiesa, D. et al. Human NK cell response to pathogens. Semin Immunol 26, 152–60 (2014).

- Ljunggren, H. G. & Kärre, K. In search of the “missing self”: MHC molecules and NK cell recognition. Immunol Today. 11, 237–281 (1990).

- Black, A. et al. PLCO: Evolution of an Epidemiologic Resource and Opportunities for Future Studies. Rev. Recent. Clin. Trials 10, 238–245 (2015).

- Prakash, P., Verma, S. & Gupta, S. Gut Microbiome and Risk of Lethal Prostate Cancer: Beyond the Boundaries. Cancers 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nearing, J. T., Declercq, V. & Langille, M. G. Investigating the oral microbiome in retrospective and prospective cases of prostate, colon, and breast cancer. Biofilms Microbiomes 9, 23–23 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. P. B. D., Alluri, L. S. C., Bissada, N. F. & Gupta, S. Association between oral pathogens and prostate cancer: Building the relationship. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol 7, 1–10 (2019).

- Alluri, L. S. C. et al. Presence of Specific Periodontal Pathogens in Prostate Gland Diagnosed with Chronic Inflammation and Adenocarcinoma. 17742–17742 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zha, C. et al. Potential role of gut microbiota in prostate cancer: Immunity, metabolites, pathways of action? Front. Oncol 1196217–1196217 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Reichard, C. A. et al. Gut Microbiome-Dependent Metabolic Pathways and Risk of Lethal Prostate Cancer: Prospective Analysis of a PLCO Cancer Screening Trial Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev 2022, 192–199. [CrossRef]

- Liss, M. A. et al. Metabolic Biosynthesis Pathways Identified from Fecal Microbiome Associated with Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol 74, 575–582 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W., Wu, K. & Long, Z. Gut dysbiosis promotes prostate cancer progression and docetaxel resistance via activat- ing NF-κB-IL6-STAT3 axis. 10, 94–94 (2022).

- Golombos, D. M. et al. The role of gut microbiome in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer: A prospective, pilot study. Urology 111, 122–128 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.-Y. Causality investigation among gut microbiota, immune cells, and prostate diseases: a Mendelian randomiza- tion study. Frontiers in microbiology 15, 1445304–1445304 (2024).

- Alanee, S. et al. A prospective study to examine the association of the urinary and fecal microbiota with prostate cancer diagnosis after transrectal biopsy of the prostate using 16sRNA gene analysis. Prostate 79, 81–87 (2019).

- Daisley, B. A. et al. Abiraterone acetate preferentially enriches for the gut commensal Akkermansia muciniphila in castrate-resistant prostate cancer patients. Nat. Commun 4822–4822 (2020).

- Liu, Y. & Jiang, H. Compositional differences of gut microbiome in matched hormone-sensitive and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Transl. Androl. Urol 2020, 1937–1944. [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M. et al. The gut microbiota associated with high-Gleason prostate cancer. Cancer Sci 112, 3125–3135 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Pernigoni, N. et al. Commensal bacteria promote endocrine resistance in prostate cancer through androgen biosynthesis. Science 374, 216–224 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Yu, S. H. & Jung, S. I. The potential role of urinary microbiome in benign prostate hyperplasia/lower urinary tract symptoms. Diagnostics 2022 12, 1862–1862. [CrossRef]

- Sfanos, K. S., Yegnasubramanian, S., Nelson, W. G. & Marzo, A. M. D. The inflammatory microenvironment and microbiome in prostate cancer development. Nat. Rev. Urol 15, 11–24 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Yow, M. A. et al. Characterisation of microbial communities within aggressive prostate cancer tissues. Infect. Agent. Cancer 12, 4–4 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D. E. et al. Bacterial communities of the coronal sulcus and distal urethra of adolescent males. PLoS ONE 7, 36298–36298 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Jayalath, S. & Magana-Arachchi, D. Dysbiosis of the human urinary microbiome and its association to diseases affecting the urinary system. Indian. J. Microbiol 2022, 153–166. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. et al. Urinary microbiota in patients with prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Arch. Med. Sci 11, 385–394 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, E. et al. Profiling the urinary microbiome in men with positive versus negative biopsies for prostate cancer. J. Urol 199, 161–171 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Hurst, R. et al. Microbiomes of urine and the prostate are linked to human prostate cancer risk groups. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 412–419.

- Ravich, A. & Ravich, R. A. Prophylaxis of cancer of the prostate, penis, and cervix by circumcision. N Y State J Med. 51 (1951).

- De Martel, S. & Franceschi. Infections and cancer: established associations and new hypotheses. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol (2009).

- Miyake, K. et al. Mycoplasma genitalium Infection and Chronic Inflammation in Human Prostate Cancer: Detection Using Prostatectomy and Needle Biopsy Specimens. Cell (2019).

- Cavarretta, R. et al. Microbiome of the Prostate Tumor Microenvironment. European Urology 72, 625–631 (2017).

- Zedan, A. H., Hansen, T. F. et al. Natural killer cell activity in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer patients treated with enzalutamide.. Sci Rep (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kastelan, M., Kraljic’, I. & Tarle, M. NK cell activity in treated prostate cancer patients as a probe for circulating tumor cells: hormone regulatory effects in vivo. Prostate 21, 111–131 (199). [CrossRef]

- Riley, R. D. et al. Reporting of prognostic markers: current problems and development of guidelines for evidence-based practice in the future. British Journal of Cancer 88, 1191–1198 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Fanijavadi, S.; Thomassen, M.; Jensen, L.H. Targeting Triple NK Cell Suppression Mechanisms: A Comprehensive Review of Biomarkers in Pancreatic Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 515. [CrossRef]

| Year/Reference | No/Population | Sample/Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021/ [69] | 35/Local, Local advanced PCa 27/Control |

PB, Tumor tissue/ Flowcytometry |

In comparison to the control group, tumor-associated NK cells from PCa patients exhibited significantly elevated mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic factors. Additionally, these NK cells showed a marked downregulation of NKG2D. Overall, NK cells in PCa patients adopted a pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic |

| 2018/ [68] | 10/PCa 10/Control |

Tumor tissue Isolated lymphocyte/ Flowcytometry |

Compared to normal tissue, lymphocytes isolated from PCa showed significantly higher levels of miR-224, which plays a protective role for cancer cells against NK cell-mediated destruction. HIF-1α was found to upregulate miR-224, leading to the inhibition of NCR1/NKp46 and reducing the killing efficiency of NK cells in prostate cancer. |

| 2016/ [18] |

16 /Localized PCa 5 /mPCa 20 /Normal tissue from patients with PCa |

PB, Tumor and normal tissue/ Flowcytomery, 51-Cr release |

A highly immunosuppressive environment in PCa significantly impairs NKA at multiple levels. |

| 2015/ [44] | 18/ Treatment naive PCa, de novo: 10 /SCR 8/ LCR 10 / Control |

PM/ Flow cytometry |

The low expression of activating receptors and reduced cytotoxicity of NK cells contribute to the pathogenesis of Pca. |

| 2014/ [70] | 18/CRPC 8 Control |

PM, Isolated lymphocyte/ Flow cytometry |

Prostate tumor-derived exosomes act as downregulators of the NKG2D-mediated cytotoxic response. |

| 2013/ [15] | 51/ PCa treatment naive 54/ Healthy control |

PMBC/NK Vue |

PCa patients exhibit a higher CD56^dim^ to CD56^bright^ NK cell ratio compared to the control group. |

| 2013/ [81] | 100 PCa 150 BC |

Tumor tissue/Immunohistochemistry | NK cell infiltration in the early stages of PCa is associated with focal disruption of the tumor capsule. |

| 2012/ [76] | 200 Untreated localized Pca 185 Healthy control |

Blood sample (DNA)/PCR | There is no evidence of a potential role for the KIR gene system in PCa. |

| 2011/ [3] | 20 Localized, local advanced Pca 20 BPH 20 Healthy control |

PBMC/Flow cytometry |

The percentage of NK cells and their subsets did not vary among the groups examined. |

| 2004/ [73] | 23/ PCa 10/ Healthy control |

Serum/ Cell line Immunohistochemical staining |

Advanced cancer is associated with high expression of MICs and low NKA. |

| 1989/ [72] | 49 Localized and advanced PCa 15 Healthy controls |

PB, Cell line /Flowcytometry |

Aberrant immune functions in the early stages, with an exacerbation of these immune abnormalities observed in advanced PCa. . |

| 1989/ [71] | 7 Localized PCa 6 Advanced PCa 25 Control |

PB, Cell line/ 51-Cr release | MRC in advanced PCa was lower than in localized PCa and the control group. |

| 1987/ [16] | 10 Localized PCa 49 Advanced PCa 10 BPH 20 Control |

PB, Cell line/ 51-Cr release |

Compared to other groups, patients with advanced PCa demonstrated significantly lower NKA, which was not attributed |

| 1985/ [80] | 8 Pca T2N0M0 8 PCa T3-T4NxM0-1 7 Control |

PB, Cell line/ 51-Cr release | Compared to the control group, beta interferon-induced augmentation of NKA was significantly reduced in the periprostatic lymph nodes of PCa patients. Additionally, the spontaneous cytotoxicity of peripheral NK cells was markedly suppressed in advanced PCa. |

| Year/Reference | No/Population | Sample/method | Main Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020/ [87] | 41 Asymptomatic PCa (PSA<20ng/ml) 31 Control (Benign) |

PB/ Flow cytometric profiling combined to Machine learning |

NK cell profiling identified 8 features of NK cells, which distinguishe between PCa and benign disease. NK cell profiling could serve as a potential screening tool for prostate cancer detection. |

| 2020/ [88] | 18 PCa, GS>7 8 PCa, GS=7 24 PCa, GS=6 52 PCa, Benign |

PB/NK Vue | NKA demonstrated a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 73% for detecting PCa, with a cut-off value of 500 pg/mL. |

| 2019/ [89] |

25 Localized PCa 37 Local advanced, advanced 32 Not detected in biopsies. |

PB/NK Vue |

Low NKAcan serve as a predictive tool for positive prostate cancer biopsy, with a cut-off value of 200 pg/mL |

| 2018/ [91] |

221/ Pca 18 GS 9-10 25 GS 8 49 GS 7 43 GS 6 86/ Biopsy negative |

PB/NK Vue | The study could not confirm the usefulness of NKA for detecting PCa or predicting the Gleason grade. |

| 2017/ [90] | 21 /PCa 22/ Biopsy negative |

PB/NK Vue Tissue |

The researchers of the study showed that the absolute risk for PCa is 86% when NKA is low. |

| 2014/ [] |

8/ mPCA 36/ mBC 30/ mCRC |

PB/ Flow Cytometry |

High levels of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are associated with low NKA levels. |

| 2013/ [15] | 51/ PCa 8 GS=9 8 GS=8 25 GS=7 10 GS=6 54/Biopsy negative |

PB/NK Vue | NKA demonstrates a sensitivity of 72% and specificity of 74% for detecting PCa, with a cut-off value of 530.9 pg/mL. |

| 2004/ [73] | 23/ PCa 10/ Healthy control |

Serum/ ELISA | sMIC is proposed as a novel biomarker for the detection of high-grade PCa. |

| 1993/ [86] | 23/ Localized and advanced PCa 10/Healthy control 6 Chronic diseases |

PB/51-Cr | NK lytic activity in patients with untreated PCa effectively differentiates between tumor dissemination and localized PCa. |

| 1992 | 51 mPCa: 6 DES 11 Estracyt 9 CPA 7 Orchiectomy 12 Orchiectomy +CPA 6 Orchiectomy +Flutamide 7 Healthy control |

PB/51-Cr | Low NKA levels in treated PCa patients suggest the presence of CTCs monitoring for treatment response diagnostic application. |

| 1987/ [16] | |||

| 1985/ [80] |

| Year/Reference | No/Population | Sample/Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024/ [93] | 3365 samples of mPCa 87551 samples of 44 distinct tumor type |

FFPE/ quanTIseq |

NK cell infiltration lead to improved Pca patient outcomes. |

| 2023/ [141] | 87 mCRPC |

PB NK vue |

In the late stage mCRPC patients receiving enzalutamide, higher NKA levels correlated with poorer treatment responses suggesting that NK cells may negatively impact advanced prostate cancer and could serve as predictive markers for treatment efficacy. |

| 2020/ [96] | 24 negative surgical margin 27 positive margin 10 healthy |

PB NK vue |

Higher postoperative NKA levels are associated with an increased likelihood of negative surgical margins, indicating better prognosis. |

| 2018/ [100] | 19 mPCa 23 mOCa 51 mCRC |

PB NK Vue |

Lower NKA levels correlate with reduced response rates and shorter PFS. An increase from low to normal NKA, highlighting its predictive potential. |

| 2017/ [105] | 22 non metastatic non castrate 16 CRPC |

PB FlowCytometry |

The fr The frequency of NK cells does not differ between immune responders and non-responders following vaccination, suggesting limited predictive value. |

| 2015/ [44] | 18 Treatment naive PCa, de novo: 10 SCR 8 LCR 10 Control |

PB FlowCytometry |

NKp30 NKp30 and NKp46 are predictor markers for OS with p-values of 0.0018 and 0.0009, respectively. p-vaof. TCR also demonstrates significance with p-values of 0.007, 0.009, and 0,0001, indicating their prognostic and predictive potential (log-rank test). |

| 2014/ [98] | 30 mCPC | PB Flow Cytometry |

High High lev High levels of Tim-3(+) NK cells after vaccination, compared to before vaccination, are associated with longer OS, indicating their prognostic significance. |

| 2014/ [99] | 72 mPCa before ADT or no longer than 3 months 50 mPCa ADT +/- Risedronate |

Serum Multiplex electrochemiluminescence |

Higher cytokine levels observed 0.5 months after the initiation of ADT are associated with shorter TCR and OS, potentially indicating resistance to treatment, with no relation to IL-2 levels. This highlights no prognostic and predictive value of IL-2 as an NK cell activator |

| 2014/ [19] | 8 mPCa 36 mBC 30 mCRC |

PB CellSearch CTC test |

High CTCs represent low NKA and high risk of poor prognosis. |

| 2013/ [15] | 51 Pca no prior treatment 54 Healthy control |

PB NK Vue |

A higher CD56dim/CD56bright ratio or lower levels of CD56bright cells are associated with poor prognosis. |

| 2012/ [81] | 100 PCa, 150 BC |

Tumor Tissue IHC |

NK cell infiltration in the early stage PCa is linked to focal disruptions of the tumor capsule and poor prognosis. |

| 2011/ [95] | 197/PCa, 3DRT 116 T1-T4 WP 81 T1-T4 PO |

PB Flowcytometry |

A positive correlation exists between NK cell numbers and bone marrow irradiated with 5-25 Gy, as well as with acute GU, late GU, and GI toxicities. This upregulation of NK cytotoxicity is associated with better prognosis and predictive outcomes. |

| 2009/ [1,24] | 35 PCa neoadjuvant ADT+RT 40 Pca RP |

Tumor tissue IHC |

Higher levels of CD56+ NK cells are associated with a lower risk of PCa progression, indicating their potential prognostic application. |

| 2004/ [73] | 23 Localized and advanced PCa 10 Healthy donor |

Serum ELISA |

Higher levels of sMIC are associated with poor prognosis, highlighting its potential prognostic application. |

| 1995 [33] | 11 Localized PCa, RP, TURP 41 Advanced, Castration (medical or surgical) 10 BPH |

Tumor tissue |

Higher expression of HNK-1 antigen is associated with longer survival and PFS, indicating its prognostic and predictive value. |

| 1992/ [140] | |||

| 1989/ [71] | 7 Localized PCa 6 Advanced PCa 25 Healthy control |

PB, cell line K562 | NKA, Vmax, and MRC levels in advanced PCa are lower than those in localized PCa and control groups, indicating potential prognostic significance. |

| 1980/ [97] | 6 PCa 7 UBC 24 BC |

PB/51-Cr release | NKA is positively associated with prognosis, indicating its potential prognostic value. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).