Submitted:

11 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

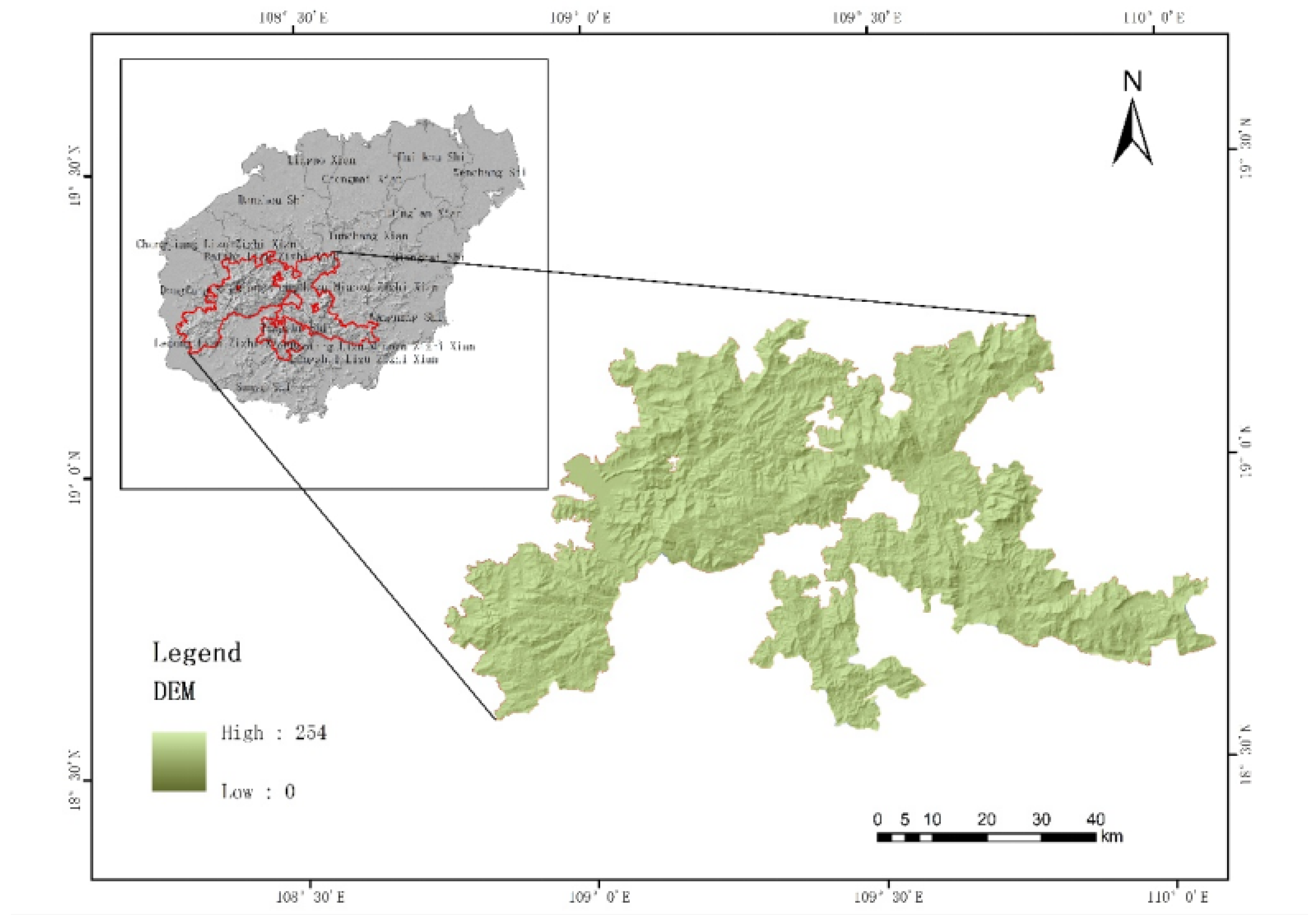

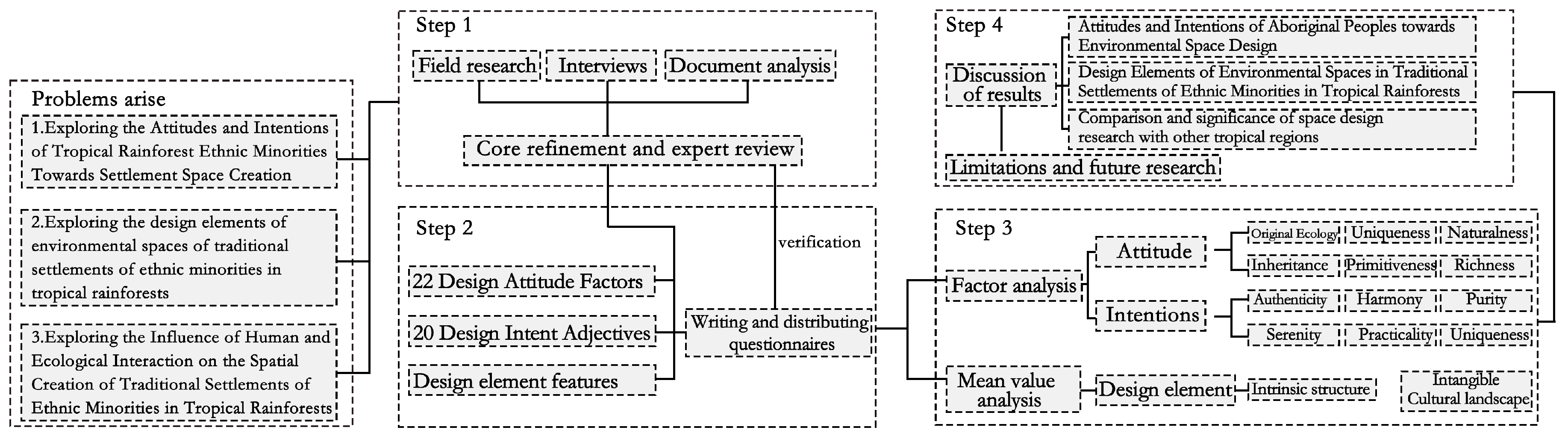

2. Methods and Data

2.1. Survey Design and Analysis Methods

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Sample Introduction

3.2. Attitudinal Factor Analysis of Spatial Environment Design for Traditional Li Settlements

3.3. Factor Analysis of Spatial Environmental Imagery in Traditional Li Settlements

3.4. Factor Analysis of the Design Elements of Space Creation for Traditional Li Settlements

3.4.1. Research Methods on Design Elements of Space Creation for Traditional Li Settlements

3.4.2. Analysis of the Mean Value of Design Elements in Traditional Li Village Spatial Planning

3.4.3. Analysis of Mean Values for Road Structure, Water System, and Farmland Landscape

4. Conclusions

4.1. Aboriginal Attitudes and Intentions Towards the Design of Environmental Spaces

4.2. Elements of Environmental Space Design for Traditional Settlements of Ethnic Minorities in Tropical Rainforests

4.3. Comparison with Other Spatial Design Studies in the Tropics and Research Implications

Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, L.; Tang, Y. Towards the Contemporary Conservation of Cultural Heritages: An Overview of Their Conservation History. 7, 175–192. [CrossRef]

- Heckenberger, M.; Neves, E. Amazonian Archaeology. 38, 251–266. [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, E.; Schulz, C.; Martín Brañas, M. Wetland Spirits and Indigenous Knowledge: Implications for the Conservation of Wetlands in the Peruvian Amazon. 3, 100107. [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Cullen-Unsworth, L.C.; Talbot, L.D.; McIntyre-Tamwoy, S. Empowering Indigenous Peoples’ Biocultural Diversity through World Heritage Cultural Landscapes: A Case Study from the Australian Humid Tropical Forests. 17, 571–591. [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Liu, J. Investigation into the Thermal Comfort and Some Passive Strategies for Traditional Architecture of Li Nationality in South China. 32, 1349–1371. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. The Definition of Indigenous Peoples and Its Applicability in China. 22, 232–258. [CrossRef]

- Corntassel, J. Who Is Indigenous? ‘Peoplehood’ and Ethnonationalist Approaches to Rearticulating Indigenous Identity. 9, 75–100. [CrossRef]

- Atmanti, F.P.; Uekita, Y. Preserving Tradition: The Role of Community Customs and Sustainable Practices in Traditional House Preservation on Nias Island, Indonesia. 0, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Imsong, R.; Kumar, A. Transformations in the Vernacular Buildings of Nagaland, India. In Potency of the Vernacular Settlements; Routledge.

- Peng, P.; Zhou, X.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, L.; Wu, J.; Rong, Y. An Exploration of the Self-Similarity of Traditional Settlements: The Case of Xiaoliangjiang Village in Jingxing, Hebei, China. 12. [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Yao, Q.; Long, B.; An, N.; Liu, Y. Progress in the Research of Features and Characteristics of Mountainous Rural Settlements: Distribution, Issues, and Trends. 16, 4410. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Song, Z. Landscape Gene and Image Representation of Traditional Settlements in East Qinling Mountain: Based on the Survey of 11 Villages. 51, 234–246. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, B.; Zhu, J.; Sun, L. Traditional Village Research Based on Culture-Landscape Genes: A Case of Tujia Traditional Villages in Shizhu, Chongqing, China. 23, 325–343. [CrossRef]

- Tahroodi, F.M.; Ujang, N. Engaging in Social Interaction: Relationships between the Accessibility of Path Structure and Intensity of Passive Social Interaction in Urban Parks. 16, 112–133. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Josef, S.; Min, Q.; Tan, M.; Cheng, F. Visualizing the Cultural Landscape Gene of Traditional Settlements in China: A Semiotic Perspective. 9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, R.; Yi, X.; Qiu, H. Spatial Distribution of Toponyms and Formation Mechanism in Traditional Villages in Western Hunan, China. 12. [CrossRef]

- Nur, R.; Gunawan, A.; Pratiwi, P.I. Model of Traditional Settlement Landscape of Lakkang Island Based on Local Culture. 13, 1209–1222.

- Prideaux, B.; McNamara, K.; Thompson, M. The Irony of Tourism: Visitor Reflections of Their Impacts on Australia’s World Heritage Rainforest. 11, 102–117. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Cai, M.; Shi, Y. Research on Location Characteristics of Traditional Settlement of Ethnic Groups in the Hainan Island Based on GIS Technologies. Vol. 136. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. A Century of Integrated Research on the Human-Environment System in Chinese Human Geography. 46, 988–1008. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.F.; Carballo-Cruz, F.; Ribeiro, J.C. Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Development in the Context of a New Governance Framework for Portuguese Protected Areas: The Case of a Small Peripheral Natural Park. 112, 103451. [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; He, R.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhuo, S.; Zhou, P. Spatial Configuration and Accessibility Assessment of Recreational Resources in Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park. 16. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xing, J.; Chen, K.; Chen, S.; Lu, Y.; Liu, J. The Value, Protection, and Tourism Transformation of Li Ethnic Group’s Traditional Settlements under the Background of "Double Heritage". 9, 11–20.

- Zhou, L.F. Cultural Duality: Investigating ’double Heritage’ Transformation among the Li People. 11, 18–28.

- Franco, L.S.; Shanahan, D.F.; Fuller, R.A. A Review of the Benefits of Nature Experiences: More than Meets the Eye. 14, 864. [CrossRef]

- Ilovan, O.R.; Markuszewska, I. Introduction: Place Attachment – Theory and Practice. In Preserving and Constructing Place Attachment in Europe; Ilovan, O.R.; Markuszewska, I., Eds.; Springer International Publishing; pp. 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. A Book Review: Case Study.

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C.; Gadgil, M. Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Biodiversity, Resilience and Sustainability. In Biodiversity Conservation: Problems and Policies. Papers from the Biodiversity Programme Beijer International Institute of Ecological Economics Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences; Perrings, C.A.; Mäler, K.G.; Folke, C.; Holling, C.S.; Jansson, B.O., Eds.; Springer Netherlands; pp. 269–287. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Zhang, X.; Murray, A.T. Spatial Optimization for Land-Use Allocation: Accounting for Sustainability Concerns. 41, 579–600. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Wen, B.; He, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, F. Application of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Analysis to Rural Spatial Sustainability Evaluation: A Systematic Review. 19, 6572. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Mateus, R.; Bragança, L.; Correia da Silva, J.J. Portuguese Vernacular Architecture: The Contribution of Vernacular Materials and Design Approaches for Sustainable Construction. 58, 324–336. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. Exploring Low-Carbon Design and Construction Techniques: Lessons from Vernacular Architecture. 11, 165. [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y. Social Organisation of the Li Tribe of Hainan Island. 10, 115–126. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; She, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, S. Study on Ecological Adaptability of Traditional Village Construction in Hainan Volcanic Areas. 22, 494–512. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.W.; Umezaki, M.; Ohtsuka, R. Inter-Household Variation in Adoption of Cash Cropping and Its Effects on Labor and Dietary Patterns: A Study in a Li Hamlet in Hainan Island, China. 114, 165–173. [CrossRef]

- He, X. The Last of the Li: Ritual Texts and Shifting Ethnicities in Hainan. 18, 236–249. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. The Traditional Settlement and Architectural Space Form of Hainan Based on Marine Climate. 112, 15–18. [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, G. Sustainability Lesson Learnt from the Traditional and Vernacular Architecture.

- Dong, R.; Li, Y.; Yang, D. Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors Analysis of Hainan’s Tropical Marine Cultural Landscape. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Environmental Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Technology (ERSGIT 2023). SPIE, Vol. 12988, pp. 150–159. [CrossRef]

- Chongyi, F.; Goodman, D.S.G. Hainan: Communal Politics and the Struggle for Identity. In China’s Provinces in Reform; Routledge.

- Hongli, X. The Primitive Pile-Dwelling of Li Nationality in Hainan and Transition.

- Marshall, G.; Jonker, L. An Introduction to Descriptive Statistics: A Review and Practical Guide. 16, e1–e7. [CrossRef]

- Reise, S.P.; Waller, N.G.; Comrey, A.L. Factor Analysis and Scale Revision. 12, 287–297. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.O.; Adhikari, N.K.; Beyene, J. The Ratio of Means Method as an Alternative to Mean Differences for Analyzing Continuous Outcome Variables in Meta-Analysis: A Simulation Study. 8, 32. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.f.; Chiou, S.c. Study on the Sustainable Development of Human Settlement Space Environment in Traditional Villages. 11, 4186. [CrossRef]

- Vythoulka, A.; Delegou, E.T.; Caradimas, C.; Moropoulou, A. Protection and Revealing of Traditional Settlements and Cultural Assets, as a Tool for Sustainable Development: The Case of Kythera Island in Greece. 10, 1324. [CrossRef]

- Diasana Putra, I.D.G.A. Proceedings of the 4th Biennale ICIAP (International Conference on Indonesian Architecture and Planning).

- Yang, G.; Yu, Z.; Luo, T.; Lone, S.K. Residents’ Urbanized Landscape Preferences in Rural Areas Reveal the Importance of Naturalness-Livability Contrast. 32, 1493–1512. [CrossRef]

- Ridder, B. The Naturalness versus Wildness Debate: Ambiguity, Inconsistency, and Unattainable Objectivity. 15, 8–12. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, D.; Chen, X.; Fadelelseed, S. Inheritance and Evolution of the Spatial Form of Traditional Rural Settlement. 3. [CrossRef]

- Dang, A.; Wang, F. Information Technology Methods for Locality Preservation and Inheritance of Settlement Cultural Landscape. 30, 437–441. [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, S.A. Regional Settlement Pattern Studies. 16, 225–285. [CrossRef]

- Akbar, N.; Abubakar, I.R.; Bouregh, A.S. Fostering Urban Sustainability through the Ecological Wisdom of Traditional Settlements. 12, 10033. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q. Research on Subjective-Cultural Ecological Design System of Vernacular Architecture. 14, 13564. [CrossRef]

- Rishbeth, C. Ethnic Minority Groups and the Design of Public Open Space: An Inclusive Landscape? 26, 351–366. [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Xiong, R.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W. Traditional Architectural Heritage Conservation and Green Renovation with Eco Materials: Design Strategy and Field Practice in Cultural Tibetan Town. 16, 6834. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zakaria, S.A. Morphological Characteristics and Sustainable Adaptive Reuse Strategies of Regional Cultural Architecture: A Case Study of Fenghuang Ancient Town, Xiangxi, China. 15, 119. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Jamaludin, O.; Doh, S.I. Protection and Development Strategies for Traditional Ethnic Minority Villages in Sichuan: A Case Study of a Qiang Traditional Village. 15.

- Li, B.; Yang, F.; Long, X.; Liu, X.; Cheng, B.; Dou, Y. The Organic Renewal of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of Logical Space Restoration and Physical Space Adaptation: A Case Study of Laoche Village, China. 144, 102988. [CrossRef]

- Chunai, X.; Qin, L.; Yinzhu, Z. Ethnic Cultural Identity Crisis and Its Adaptation Taking Blang Ethnic Group in Yunnan Province as an Example. Atlantis Press, pp. 230–237. [CrossRef]

- Yuzhong, C.; Chantaree, T.; Sriruksa, K.; Sriruksa, A. Analyzing Architectural and Cultural Dong Minority Ethnic Wisdom through Dong Villages’ Drum Towers at Tongdao County in the Pingtan River Basin. 22. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.C. Settlement in the Humid Tropical Life Zones of Latin America. 12, 34–42, [25765663].

- Cardoso, A.C.; Silva, H.; Melo, A.C.; Araújo, D. Urban Tropical Forest: Where Nature and Human Settlements Are Assets for Overcoming Dependency, but How Can Urbanisation Theories Identify These Potentials? In Emerging Urban Spaces: A Planetary Perspective; Horn, P.; Alfaro d’Alencon, P.; Duarte Cardoso, A.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing; pp. 177–199. [CrossRef]

- Sirajuddin, Z.; Fitriaty, P.; Shen, Z. Pengataa, ToKaili Customary Spatial Planning: A Record of Tropical Settlements in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. 6, 547–569. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Ara, D.R. Modernity in Tradition: Reflections on Building Design and Technology in the Asian Vernacular. 4, 46–55. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, K. Beyond Tropical Regionalism: The Architecture of Southeast Asia. In A Critical History of Contemporary Architecture; Routledge.

- Sierra-Huelsz, J.A.; Kainer, K.A. Tourism Consumption of Biodiversity: A Global Exploration of Forest Product Use in Thatched Tropical Resort Architecture. 94, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Nunn, P.D.; Campbell, J.R. Rediscovering the Past to Negotiate the Future: How Knowledge about Settlement History on High Tropical Pacific Islands Might Facilitate Future Relocations. 35, 100546. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. Cultural Landscapes and Asia: Reconciling International and Southeast Asian Regional Values. 34, 7–31. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, S.; Tao, T.; Gong, M.; Bai, J. Spatial Reconstruction of Rural Settlements Based on Livability and Population Flow. 126, 102614. [CrossRef]

- Henning, D.H. Nature Based Tourism Can Help Conserve Tropical Forests. 18, 45–50. [CrossRef]

| Rank | Word | Frequency | Weighted Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ecology | 570 | 8.10 |

| 2 | Region | 436 | 6.18 |

| 3 | Characteristic | 430 | 6.14 |

| 4 | Nature | 418 | 5.94 |

| 5 | Culture | 350 | 4.98 |

| 6 | Inheritance | 290 | 4.14 |

| 7 | Local | 282 | 3.78 |

| 8 | History | 218 | 3.06 |

| 9 | Wisdom | 182 | 2.62 |

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| FT1 | The traditional Li settlement culture embodies respect and reverence for nature. [28] |

| FT2 | The location selection and architectural style of Li settlements fully reflect adaptation to the natural environment. [29] |

| FT3 | Open street layout with crisscrossing streets and alleys, forming good ventilation. [30] |

| FT4 | Traditional Li architecture mostly uses natural materials. [31] |

| FT5 | Diverse environment of mountains, forests, grasslands, and fields. [32] |

| FT6 | Rich cultural landscapes. [33] |

| FT7 | Protection and inheritance of ecological wisdom. [34] |

| FT8 | Traditional settlements are important carriers of cultural inheritance. |

| FT9 | Protection and inheritance of traditional architectural skills. |

| FT10 | Protection and inheritance of traditional craftsmanship. [35] |

| FT11 | Simple and ancient cultural and artistic style. [36] |

| FT12 | Architecture and planning in traditional settlements should reflect ecological and environmental protection concepts. [32] |

| FT13 | Use simple architectural forms and materials to reduce environmental damage. |

| FT14 | Appropriate size, few traces of artificial carving. |

| FT15 | Traditional settlements and the surrounding natural environment form an ecologically balanced system. [37] |

| FT16 | Traditional settlements are laid out according to local conditions. [37] |

| FT17 | Buildings in traditional settlements often use locally renewable materials. [38] |

| FT18 | Traditional Li architecture is mainly made of bamboo and wood. |

| FT19 | The differences in geographical environment, climate conditions, and resource endowment show unique regional characteristics. [39] |

| FT20 | Unique spatial organization and landscape. [40] |

| FT21 | Unique boat-shaped house architecture. [41] |

| FT22 | The architectural structure and color have no excessive decoration. [41] |

| Factor Indicator | Factor Loading | Eigenvalue | Contribution Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Original Ecology | |||

| Layout adapted to local conditions | 0.667 | 4.922 | 22.215 |

| Ecological balance with the environment | 0.646 | ||

| Simple construction forms and materials | 0.635 | ||

| Locally renewable materials | 0.630 | ||

| Ecological and environmental protection in planning | 0.598 | ||

| Factor 2: Uniqueness | |||

| Unique boat-shaped house architecture | 0.713 | 2.563 | 11.899 |

| Bamboo and wood structure | 0.706 | ||

| Unique spatial organization and landscape | 0.679 | ||

| Unique regional characteristics | 0.661 | ||

| Factor 3: Naturalness | |||

| Adaptation to natural environment | 0.750 | 1.718 | 7.136 |

| Use of natural materials | 0.732 | ||

| Open street layout for ventilation | 0.521 | ||

| Respect and reverence for nature | 0.439 | ||

| Factor 4: Inheritance | |||

| Cultural inheritance through settlements | 0.590 | 1.485 | 5.971 |

| Preservation of architectural skills | 0.561 | ||

| Preservation of ecological wisdom | 0.488 | ||

| Preservation of traditional craftsmanship | 0.469 | ||

| Factor 5: Primitiveness | |||

| Appropriate size, minimal carving | 0.685 | 1.254 | 4.853 |

| No excessive decoration | 0.644 | ||

| Simple and ancient style | 0.601 | ||

| Factor 6: Richness | |||

| Rich cultural landscapes | 0.677 | 0.986 | 4.207 |

| Diverse environments | 0.656 | ||

| Cumulative Contribution Rate | 56.281% | ||

| Factor Indicator | Factor Loading | Eigenvalue | Contribution Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Authenticity | |||

| Natural | 0.712 | 3.045 | 15.241 |

| Ecological | 0.637 | ||

| Rustic | 0.601 | ||

| Leisurely | 0.553 | ||

| Simple | 0.519 | ||

| Factor 2: Harmony | |||

| Neat | 0.719 | 2.819 | 14.105 |

| Rhythmic | 0.687 | ||

| Harmonious | 0.682 | ||

| Gentle | 0.389 | ||

| Factor 3: Purity | |||

| Elegant | 0.781 | 1.379 | 6.891 |

| Fresh | 0.652 | ||

| Simple | 0.647 | ||

| Refreshing | 0.451 | ||

| Factor 4: Serenity | |||

| Spiritual | 0.754 | 1.202 | 5.539 |

| Elegant | 0.671 | ||

| Simple | 0.533 | ||

| Factor 5: Practicality | |||

| Strict | 0.819 | 1.023 | 5.118 |

| Solemn | 0.729 | ||

| Factor 6: Uniqueness | |||

| Unique | 0.944 | 0.944 | 4.721 |

| Personal | 0.617 | ||

| Innovative | 0.580 | ||

| Cumulative Contribution Rate | 52.050% | ||

| Design Element | Primary Category | Secondary Category |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Structure |

Space Type | Boundary Space Residential Space Living Space |

| Architectural Feature | Individual Form Materials and Structure Layout and Organization |

|

| Road Structure | Road Structure Herringbone Zigzag |

|

| Water System | Surface Water Linear Water Connected Style |

|

| Plants | - | |

| Farmland | Terraced Fields Interwoven |

|

| Intangible Cultural Landscape |

Religion | Totem |

| Custom | Agriculture Festival |

|

| Traditional Craft | Li Brocade Tattoo |

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 | X7 | X8 | |

| N | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Mean | 2.40 | 2.75 | 2.95 | 3.95 | 3.10 | 2.65 | 1.80 | 2.70 |

| Space Types | Building Characteristics | |||||

| Boundary Space | Residential Space | Living Space | Individual Form | Layout & Organization | Building Materials | |

| N | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| Mean | 2.45 | 3.50 | 3.18 | 2.82 | 3.57 | 3.05 |

| Road Structure | Water System | Farmland Landscape | ||||||

| Fishbone | Zigzag | Tree-like | Continuous | Surface | Linear | Terraced | Intersected | |

| N | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| Mean | 3.01 | 3.56 | 2.56 | 3.29 | 3.34 | 2.97 | 3.34 | 2.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).