3.1.1. General Reagent and Analytical Information

All solvents used were purified according to standard procedures or of HPLC or p.a. grade purchased from commercial sources. Chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Schnelldorf, Germany) TCI (Eschborn, Germany) and BLD Pharm (Kaiserslautern). IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer FTIR Paragon 1000 spectrometer. NMR spectra were recorded on Jeol JNMR-GX 400 (400 MHz), Jeol JNMR-GX 500 (500 MHz), Avance III HD Bruker BioSpin (400 MHz) and Avance III HD Bruker BioSpin (500 MHz) spectrometers. Spectra were recorded in deuterated solvents and signal assignments were carried out based on 1H, 13C, DEPT, HMQC, HMBC, and COSY spectra. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) and J values are reported in hertz. High- resolution mass spectra were performed by electrospray ionization (ESI) using a Thermo Finnigan LTQ FT Ultra spectrometer or electron impact (EI) at 70 eV on a Jeol GCmate II or on a Finnigan MAT 95 spectrometer. All reactions were monitored by GC/MS or thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using precoated plastic sheets POLYGRAM®SIL G/UV254 from Macherey-Nagel (Düren, Germany). Compounds on TLC plates were detected under UV light at 254 and 366 nm. Separations with flash column chromatography (FCC) were performed on Merck silica gel 60 as stationary phase. Melting points were determined by the open tube capillary method on a Büchi melting point B- 540 apparatus and are uncorrected. HPLC purities were determined using an HP Agilent 1100 HPLC with a diode array detector and an Agilent Zorbax Eclipse plus C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm; 5 μm) with acetonitrile/water in different proportions as mobile phase.

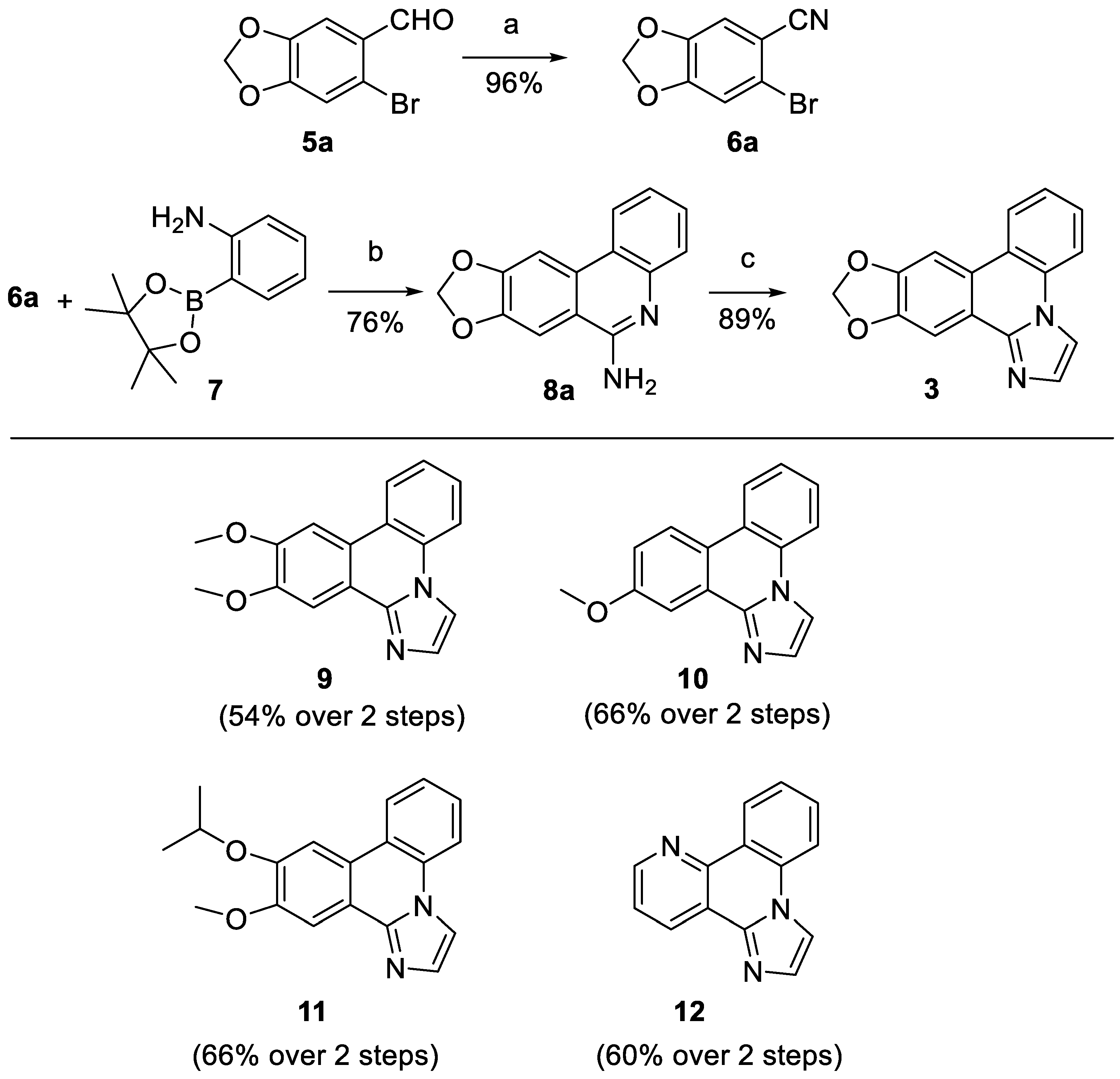

General procedure A for the conversion of aromatic aldehydes into nitriles. The aldehyde 5a-e (10 mmol, 1.0 eq) was dissolved in DMSO and hydroxylamine hydrochloride (15 mmol, 1.5 eq) was added. The mixture was heated to 90 °C and stirred for 1 h at this temperature. After cooling to room temperature water (20 mL) was added and the suspension was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 x 15 mL). The organic phases were pooled, washed with brine (3 x 15 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with the declared eluent.

General procedure B for the synthesis of aminophenanthridines 7a-7e. Substituted 2-bromobenzonitrile 6a-e (2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq), 2-aminophenylboronic acid pinacol ester (7) (548 mg, 2.50 mmol, 1.00 eq) and bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(II) chloride (88 mg, 0.013 mmol, 0.050 eq) were dissolved in 15 mL dry, degassed DMF in a Schlenk round-bottom flask under N2. Afterwards 4 mL of a shortly degassed aqueous 2 M Na2CO3 solution was added, and the yellow suspension was stirred at 80 °C for 16 h. After cooling to room temperature, the crude mixture was filtrated through a short plug of Celite, which was subsequently washed with 50 mL methylene chloride and 50 mL methylene chloride /methanol 9:1. Then the combined organic solution was mixed with 100 mL water and the organic phase was separated. The aqueous phase was extracted twice with 25 mL methylene chloride, the organic fractions were pooled, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with the declared eluent.

General procedure C for the cyclization to the imidazophenanthridine ring system. Substituted 6-aminophenanthridine 8a-e (0.42 mmol, 1.0 eq), chloroacetaldehyde (50% in water, 0.11 mL, 4.3 eq) and Na2CO3 (71 mg, 0.84 mmol, 2.0 eq) were mixed with 3 mL isopropanol and 3 mL water. The suspension was refluxed for 1 h. After cooling to room temperature 10 mL water were added and the suspension was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 x 10 mL). The organic phases were pooled, washed with brine (10 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated. The crude product was purified by silica column chromatography with the declared eluent.

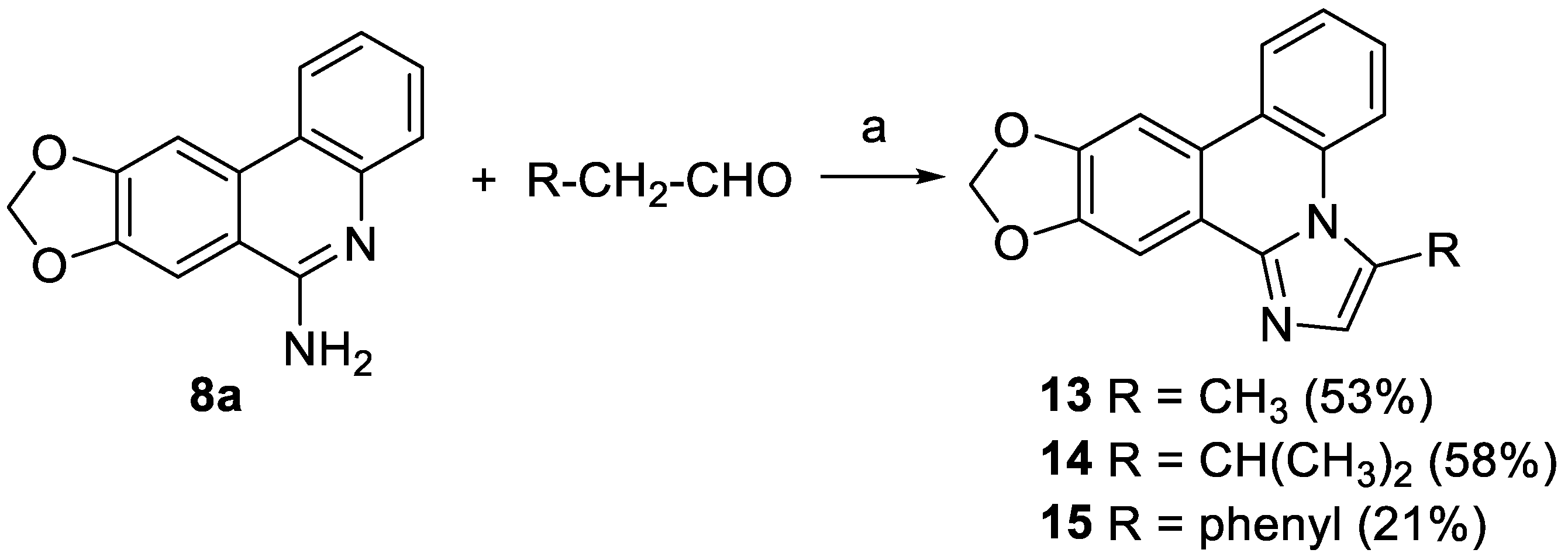

General procedure D for the cyclization to ring D-substituted imidazophenanthridines 13-15. Aminophenanthridine 8a (48 mg, 0.20 mmol, 1.0 eq) and sulfur (103 mg, 3.20 mmol, 16.0 eq) were suspended in 1 mL DMSO/cyclohexane (2:1). The appropriate aldehyde (0.30 mmol, 1.5 eq) was added and the mixture was heated at 120 °C overnight. After cooling to room temperature water (10 mL) was added and the black mixture was extracted with methylene chloride (3 x 10 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with brine (2 x 10 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated. The crude product was purified by silica column chromatography with the declared eluent.

6-Bromobenzo[d][1,3]dioxole-5-carbonitrile (6a). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure A starting from aldehyde 5a. Eluent for FSC isohexane/ethyl acetate 2:1 to afford 6a as a colourless solid (2.17 g, 9.05 mmol, 96%). m.p. 134-135 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.09 (s, 1H, 6-H), 7.03 (s, 1H, 3-H), 6.10 (s, 2H, -OCH2O-). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 152.25 (C-2), 147.47 (C-1), 119.00 (C-4), 117.36 (-CN), 113.43 (C-6), 112.59 (C-3), 107.98 (C-5), 103.06 (-OCH2O-). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 2913, 2231, 1495, 1480, 1259, 1111, 1031, 922, 880, 838, 737. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C8H4BrNO2 (M)•+: 224.9425 found: 224.9423.

2-Bromo-4,5-dimethoxybenzonitrile (6b). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure A from 2-bromo-4,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (5b). Eluent for FSC isohexane/ethyl acetate 5:1 to afford 6b as a colourless solid (2.23 g, 9.22 mmol, 92%). m.p. 117-119 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 7.10 (s, 1H, 3-H), 7.07 (s, 1H, 6-H), 3.89 (s, 3H, 1’-H), 3.84 (s, 3H, 2’H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 153.46 (C-4), 148.74 (C-5), 117.62 (C-2), 117.21 (-CN), 115.53 (C-6), 115.44 (C-3), 106.63 (C-1), 56.41 (C-1’), 56.27 (C-2’).IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 2942, 2229, 1592, 1505, 1377, 1261, 1219, 1168, 1035, 952, 874, 853, 794. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C9H8BrNO2 (M)•+: 240.9733 found: 240.9736.

2-Bromo-5-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzonitrile. The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure A from commercially available 2-bromo-5-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde. Eluent for FSC isohexane/ethyl acetate 1:1 to afford the target compound as a colourless solid (2.19 g, 9.62 mmol, 96%). m.p. 160-163 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.07 (s, 1H, -OH), 7.35 (s, 1H, 6-H), 7.17 (s, 1H, 3-H), 3.87 (s, 3H, -OCH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 152.69 (C-4), 146.49 (C-5), 119.39 (C-3), 117.70 (C-2), 116.24 (C-6), 114.44 (-CN), 105.35 (C-1), 56.40 (-OCH3). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 3367, 2229, 1608, 1508, 1438, 1286, 1267, 1211, 1160, 1020, 867, 842, 804. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C8H6BrNO2 (M)•+: 226.9576 found: 226.9582.

2-Bromo-5-isopropoxy-4-methoxybenzonitrile (6d). 2-Bromo-5-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzonitrile (1.14 g, 5.00 mmol, 1.00 eq) was dissolved in dry acetone (50 mL), K2CO3 (1.24 g, 7.50 mmol, 1.50 eq) added, and the resulting suspension stirred for 15 minutes. 2-Iodopropane (1.5 mL, 15 mmol, 3.0 eq) was added and the mixture was stirred for 48 h at 50 °C. Brine (100 mL) was added and the suspension extracted with ethyl acetate (3x 50 mL). The organic phases were pooled, washed with brine (50 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated resulting in a yellow oil, which was purified by silica column chromatography (isohexane/ethyl acetate 2:1) to afford 6d as a colorless solid (1.28 g, 4.73 mmol, 95 %). m.p. 89-91 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 7.10 (s, 1H, 3-H or 6-H), 7.09 (s, 1H, 3-H or 6-H), 4.49 (hept, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H, 1’-H), 3.87 (s, 3H, -OCH3), 1.33 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 6H, 2’-H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 154.68 (C-4), 146.83 (C-5), 119.18 (C-6), 117.65 (C-2), 117.10 (-CN), 116.01 (C-3), 106.62 (C-1), 72.16 (C-1’), 56.37 (-OCH3), 21.52 (C-2’). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 2922, 2223, 1588, 1504, 1437, 1377, 1268, 1259, 1217, 1166, 1138, 1027, 921, 860, 798. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C9H8BrNO2 (M)•+: 269.0046 found: 269.0049.

2-Bromonicotinonitrile (6e). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure A from commercially available 2-bromo-3-pyridinecarboxaldehyde. Eluent for FSC isohexane/ethyl acetate 5:1 to afford 6e as a colourless solid (1.72 g, 9.41 mmol, 94%). m.p. 107-109 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 8.60 (dd, J = 4.9, 1.9 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 8.03 (dd, J = 7.7, 2.0 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 7.41 (dd, J = 7.7, 4.9 Hz, 1H, 5-H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 152.92 (C-6), 152.52 (C-2), 142.72 (C-4), 122.38 (C-5), 114.67 (-CN), 110.82 (C-3).IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 3081, 3065, 2236, 1577, 1398, 1145, 1131, 1079, 807, 7356, 672. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C6H3BrN2 (M)•+: 181.9474 found: 181.9478.

[1,3]Dioxolo[4,5-j]phenanthridin-6-amine (8a). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure B starting from nitrile 6a. Eluent for FSC isohexane/ethyl acetate 1:2 (containing 1% triethylamine) to afford 8a as a beige solid (455 mg, 1.91 mmol, 76%). m.p. 250-252 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.35 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 8.13 (s, 1H, 11-H), 7.81 (s, 1H, 7-H), 7.52 – 7.39 (m, 2H, 1-H, 3-H), 7.21 (ddd, J = 8.3, 6.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 2-H), 6.78 (s, 2H, NH2), 6.22 (s, 2H, OCH2O). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 155.06 (C-6), 150.41 (C-7a or C-10a), 147.63 (C-7a or C-10a), 144.56 (C-4a), 130.71 (C-11a), 127.81 (C-3), 125.50 (C-1), 122.37 (C-4), 121.44 (C-2), 120.58 (C-11b), 114.07 (C-6a), 102.25 (C-7), 101.91 (OCH2O), 100.81 (C-11). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 3484, 3059, 1660, 1454, 1233, 1035, 1029, 938, 753, 731. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C14H10N2O2 (M)•+: 238.0737 found: 238.0738.

8,9-Dimethoxyphenanthridin-6-amine (8b). The synthesis was accomplished following the General Procedure B starting from nitrile 6b. Eluent for FSC ethyl acetate/ triethylamine 99:1 to afford 8b as an off-white solid (403 mg, 1.58 mmol, 63%). m.p. 215-216 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 8.29 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 7.86 (s, 1H, 7-H), 7.66 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 1-H), 7.52 (ddd, J = 8.2, 7.0, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 2-H), 7.37 (ddd, J = 8.2, 7.0, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 3-H), 7.20 (s, 1H, 10-H), 5.20 – 5.15 (br s, 2H, -NH2), 4.08 (s, 3H, 2’-H), 4.00 (s, 3H, 1’-H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 154.57 (C-6), 153.15 (C-9), 150.29 (C-8), 144.57 (C-4a), 130.00 (C-10a), 128.47 (C-3), 127.20 (C-2), 123.30 (C-1), 122.07 (C-4), 121.89 (C-10b), 113.56 (C-6a), 104.27 (C-10), 103.57 (C-7), 56.59 (C-2’), 56.51 (C-1’). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 3384, 3155, 1661, 1615, 1524, 1451, 1359, 1266, 1206, 1021, 803, 749, 732. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C15H14N2O2 (M)•+: 254.1050 found: 254.1051.

8-Methoxyphenanthridin-6-amine (8c). The synthesis was accomplished following the General Procedure B starting from commercially available 2-bromo-5-methoxybenzonitrile (6c). Eluent for FSC ethyl acetate/ triethylamine 99:1 to afford 8c as an off-white solid (450 mg, 2.01 mmol, 80%). m.p. 174-175 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.56 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H, 10-H), 8.37 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 7.77 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H, 7-H), 7.51 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 1-H), 7.43 (m, 2H, 9-H, 2-H), 7.24 (ddd, J = 8.2, 6.8, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 3-H), 6.99 (s, 2H, NH2), 3.93 (s, 3H, OCH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 158.45 (C-8), 155.11 (C-6), 143.97 (C-4a), 127.52 (C-10a), 127.31 (C-3), 125.46 (C-2), 124.28 (C-4), 121.73 (C-9, C-10), 120.37 (C-10b), 120.19 (C-1), 119.89 (C-6a), 105.82 (C-7), 55.70 (-OCH3). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 3392, 3099, 1616, 1532, 1407, 1345, 1254, 1221, 1035, 999, 821, 752, 745, 729. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C14H12N2O (M)•+: 224.0944 found: 224.0950.

8-Isopropoxy-9-methoxyphenanthridin-6-amine (8d). The synthesis was accomplished following the General Procedure B starting from nitrile 6d. Eluent for FSC ethyl acetate/ triethylamine 99:1 to afford 8d as an off-white solid (564 mg, 2.00 mmol, 80%). m.p. 208-210 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.42 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 7.97 (s, 1H, 7-H), 7.74 (s, 1H, 10-H), 7.51 – 7.37 (m, 2H, 1-H, 3-H), 7.22 (ddd, J = 8.2, 6.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 2-H), 6.85 (s, 2H, -NH2), 4.86 (hept, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H, 1’-H), 4.01 (s, 3H, -OCH3), 1.34 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 6H, 2’-H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 155.42 (C-6), 153.19 (C-9), 147.54 (C-8), 144.97 (C-4a), 129.05 (C-10a), 127.96 (C-3), 125.91 (C-1), 122.69 (C-4), 121.65 (C-2), 120.79 (C-10b), 113.40 (C-6a), 108.52 (C-10), 104.04 (C-7), 70.66 (C-1’), 56.25 (-OCH3), 22.32 (C-2’). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 3460, 3133, 1646, 1506, 1450, 1263, 1203, 1106, 1022, 850, 761, 737 HRMS (EI): calcd. for C17H18N2O2 (M)•+: 282.1368 found: 282.1358.

Benzo[h][1,6]naphthyridin-5-amine (8e). The synthesis was accomplished following the General Procedure B starting from nitrile 6e. Eluent for FSC ethyl acetate/ triethylamine 99:1 to afford 8e as an off-white solid (475mg, 2.43 mmol, 97%). m.p. 128-130°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.09 (dd, J = 4.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H, 2-H), 8.75 (m, 2H, 4-H, 10-H), 7.71 (ddd, J = 8.3, 4.4, 0.7 Hz, 1H, 3-H), 7.64 – 7.53 (m, 2H, 7-H, 8-H), 7.32 (ddd, J = 8.2, 6.8, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 9-H), 7.23 (s, 2H, -NH2). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 156.05 (C-5), 153.16 (C-2), 149.71 (C-10b), 147.48 (C-6a), 133.25 (C-4), 130.72 (C-8), 125.72 (C-7), 123.71 (C-10), 122.85 (C-3), 122.40 (C-9), 121.77 (C-10a), 114.25 (C-4a). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 3102, 1652, 1470, 1104, 740. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C12H9N3 (M)•+: 195.0791 found: 195.0791.

[1,3]Dioxolo[4,5-j]imidazo[1,2-f]phenanthridine (3, zephycandidine A). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure C using

8a as substituted phenanthridine. Eluent for FSC isohexane/ethyl acetate 1:1 to afford

3 as a colorless solid (98 mg, 0.37 mmol, 89%). m.p. 242-244 °C (lit. [

4]: 242-243 °C, lit. [

5]: 242-245 °C).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 8.24 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 8-H), 8.02 (s, 1H, 9-H), 7.95 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 2-H), 7.84 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 7.71 (s, 1H, 13-H), 7.60 – 7.54 (m, 2H, 3-H, 6-H), 7.48 (ddd, J = 8.4, 7.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H, 7-H), 6.13 (s, 2H, -OCH

2O-).

13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 149.42 (C-9a), 148.76 (C-12), 142.63 (C-13b), 131.34 (C-2), 131.11 (C-4a), 128.01 (C-6), 124.96 (C-7), 123.83 (C-8), 123.31 (C-8b), 121.75 (C-13a), 119.50 (C-8a), 115.84 (C-5), 111.53 (C-3), 102.88 (C-9), 101.76 (-OCH

2O-), 101.39 (C-13). IR (ATR): ṽ

max/cm

-1 = 2920, 1506, 1462, 1331, 1260, 1035, 848, 736 HRMS (EI): calcd. for C

16H

10N

2O

2 (M)

•+: 262.0737 found: 262.0737. HPLC purity: >99%.

10,11-Dimethoxyimidazo[1,2-f]phenanthridine (9). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure C using 8b as substituted phenanthridine. Eluent for FSC ethyl acetate/triethylamine 99:1 to afford 9 as an off-white solid (99 mg, 0.36 mmol, 85%). m.p. 165-166 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 8.34 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 8.01 – 7.98 (m, 2H, 3-H, 12-H), 7.88 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H, 8-H), 7.71 (s, 1H, 2-H), 7.59 (ddd, J = 8.3, 7.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 7.51 (s, 1H, 9-H), 7.51 (td, J = 7.0, 1.3 Hz, 1H, 7-H), 4.05 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.04 (s, 3H, OCH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 151.22 (C-10 or C-11), 151.20 (C-10 or C-11), 142.94 (C-12b), 131.84 (C-4a), 131.59 (C-2), 128.36 (C-6), 125.36 (C-8), 124.15 (C-7), 122.12 (C-8b), 121.99 (C-8a), 118.61 (C-12a), 116.48 (C-5), 112.23 (C-3), 105.40 (C-12), 104.50 (C-9), 56.64 (-OCH3), 56.53 (-OCH3). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 2830, 1615, 1516, 1478, 1455, 1274, 1212, 1161, 1142, 1033, 1017, 854, 793, 753, 711. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C17H14N2O2 (M)•+: 278.1055 found: 278.1050. HPLC purity: >99%.

11-Methoxyimidazo[1,2-f]phenanthridine (10). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure C using 8c as substituted phenanthridine. Eluent for FSC ethyl acetate/triethylamine 99:1 to afford 10 as an off-white solid (85 mg, 0.34 mmol, 82%). m.p. 99°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 8.40 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 9-H), 8.32 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 8.06 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H, 2-H), 8.04 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H, 3-H), 7.90 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H, 8-H), 7.60 (ddd, J = 8.4, 7.2, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 7.56 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H, 12-H), 7.52 (ddd, J = 8.4, 7.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H, 7-H), 7.25 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.8 Hz, 1H, 10-H), 4.00 (s, 3H, -OCH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 160.02 (C-11), 142.03 (C-12b), 130.75 (C-4a or C-2), 130.70 (C-4a or C-2), 127.83 (C-7), 125.26 (C-6), 124.73 (C-12a), 124.26 (C-9), 123.62 (C-5), 121.86 (C-8a), 121.09 (C-8b), 118.38 (C-10), 115.83 (C-8), 112.35 (C-3), 105.19 (C-12), 55.76 (-OCH3).IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 3434, 1617, 1472, 1325, 1291, 1036, 862, 750. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C16H12N2O (M)•+: 248.0944 found: 248.0943. HPLC purity: 99%.

11-Isopropoxy-10-methoxyimidazo[1,2-f]phenanthridine (11, THK-121). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure C using 8d as substituted phenanthridine. Eluent for FSC ethyl acetate/triethylamine 99:1 to afford 11 as an off-white solid (107 mg, 0.35 mmol, 83%). m.p. 73°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 8.36 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 8.03 (s, 1H, 12-H), 8.00 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, 3-H), 7.90 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H, 8-H), 7.76 (s, 1H, 9-H), 7.60 (ddd, J = 8.3, 7.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 7-H), 7.54 – 7.50 (m, 2H, 2-H, 6-H), 4.87 (hept, 1H, 1’-H), 4.05 (s, 3H, -OCH3), 1.45 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 6H, 2’-H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 152.09 (C-10), 149.45 (C-11), 142.96 (C-12b), 131.83 (C-4a), 131.50 (C-2), 128.33 (C-6), 125.40 (C-8), 124.15 (C-7), 122.20 (C-8b), 121.87 (C-8a), 118.62 (C-12a), 116.50 (C-5), 112.23 (C-3), 108.01 (C-12), 105.03 (C-9), 71.56 (C-1’), 56.60 (-OCH3), 22.30 (C-2’). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 2976, 1614, 1514, 1453, 1384, 1263, 1209, 1107, 1022, 953, 924, 849, 798, 718. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C19H18N2O2 (M)•+: 306.1363 found: 306.1364. HPLC purity: >99%.

Benzo[h]imidazo[2,1-f][1,6]naphthyridine (12). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure C using 8e as substituted phenanthridine. Eluent for FSC ethyl acetate/ triethylamine 99:1 to afford 12 as an off-white solid (57 mg, 0.26 mmol, 62%). m.p. 253-255 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 9.06 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 8.91 (dd, J = 4.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 10-H), 8.85 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 12-H), 8.07 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H, 3-H), 7.91 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.1 Hz, 1H, 8-H), 7.74 (ddd, J = 8.4, 7.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 7.63 – 7.54 (m, 3H, 2-H, 7-H, 11-H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 150.09 (C-10), 144.68 (C-8b), 141.38 (C-12b), 133.19 (C-4a), 131.93 (C-2), 131.37 (C-12), 130.48 (C-6), 126.07 (C-8), 125.32 (C-7), 123.35 (C-11), 122.73 (C-8a), 119.42 (C-12a), 115.30 (C-5), 112.61 (C-3). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 3319, 3148, 1653, 1581, 1479, 1472, 1395, 1295, 1080, 750, 726. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C14H9N3 (M)•+: 219.0791 found: 219.0790. HPLC purity: 98%.

3-Methyl-[1,3]dioxolo[4,5-j]imidazo[1,2-f]phenanthridine (13). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure D using propanal (23 µL, 0.30 mmol) as aldehyde. Eluent for FSC isohexane/ethyl acetate 1:1 to afford 13 as a colorless solid (29 mg, 0.11 mmol, 53%). m.p. 180-182 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 8.34 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.3 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 8.30 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.6 Hz, 1H, 8-H), 7.97 (s, 1H, 13-H), 7.73 (s, 1H, 9-H), 7.56 (ddd, J = 8.5, 7.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H, 7-H or 6-H), 7.49 (ddd, J = 8.3, 7.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H, 7-H or 6-H), 7.21 (q, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H, 2-H), 6.12 (s, 2H, -OCH2O-), 2.91 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 3H, -CH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 149.78 (C-9a or C-12a), 149.34 (C-9a or C-12a), 143.79 (C-13b), 134.26 (C-8a), 131.40 (C-2), 127.96 (C-6), 125.67 (C-3), 124.96 (C-7), 124.30 (C-8), 123.39 (C-8a), 122.94 (C-4a), 120.64 (C-13a), 116.98 (C-5), 102.94 (C-13), 102.46 (-OCH2O-), 101.60 (C-9), 15.64 (-CH3). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 2874, 1504, 1445, 1380, 1291, 1247, 1040, 871, 744. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C17H12N2O2 (M)•+: 276.0893 found: 276.0898. HPLC purity: 96%.

3-Isopropyl-[1,3]dioxolo[4,5-j]imidazo[1,2-f]phenanthridine (14). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure D using 3-methylbutanal (32 µL, 0.30 mmol) as aldehyde. Eluent for FSC isohexane/ethyl acetate 1:1 to afford 14 as a colorless solid (35 mg, 0.12 mmol, 58%). m.p. 170-171 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 8.28 (ddd, J = 10.9, 8.3, 1.1 Hz, 2H, 5-H, 8-H), 7.99 (s, 1H, 13-H), 7.72 (s, 1H, 9-H), 7.57 (ddd, J = 8.5, 7.1, 1.6 Hz, 1H, 7-H), 7.48 (ddd, J = 8.1, 7.1, 1.2 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 7.31 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H, 2-H), 6.11 (s, 2H, -OCH2O-), 3.79 (hept, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H, 1’-H), 1.49 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H, 2’-H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 149.24 (C-12a), 148.74 (C-9a), 143.53 (C-13b), 136.84 (C-3), 133.46 (C-4a), 127.79 (C-2), 127.40 (C-7), 124.34 (C-6), 123.78 (C-8), 122.89 (C-8b), 122.60 (C-13a), 120.17 (C-8a), 117.12 (C-5), 102.47 (C-13), 101.88 (-OCH2O-), 100.92 (C-9), 27.56 (C-1’), 22.48 (C-2’). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 1459, 1247, 1041, 871, 744 HRMS (EI): calcd. for C19H16N2O2 (M)•+: 304.1206 found: 304.1203. HPLC purity: 96%.

3-Phenyl-[1,3]dioxolo[4,5-j]imidazo[1,2-f]phenanthridine (15). The synthesis was accomplished following General Procedure D using phenylacetaldehyde (35 µL, 0.30 mmol) as aldehyde. Eluent for FSC isohexane/ethyl acetate 1:1 to afford 15 as a colorless solid (14 mg, 0.04 mmol, 21%). m.p. 232-233 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 8.27 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.5 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 8.04 (s, 1H, 13-H), 7.77 (s, 1H, 9-H), 7.57 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.2 Hz, 1H, 8-H), 7.55 – 7.49 (m, 5H, 2’-h, 3’-H, 4’-H, 5’-H, 6’-H), 7.40 (ddd, J = 8.3, 7.1, 1.2 Hz, 1H, 7-H), 7.38 (s, 1H, 2-H), 7.23 – 7.18 (m, 1H, 6-H), 6.15 (s, 2H, -OCH2O-). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methylene chloride-d2) δ 149.50 (C-12a), 148.83 (C-9a), 143.74 (C-13b), 132.50 (C-3), 132.42 (C-2), 132.28 (C-1’), 129.87 (C-3’, C-5’), 129.46 (C-4’), 128.76 (C-2’, C-6’), 128.48 (C-4a), 126.89 (C-6), 124.60 (C-7), 123.76 (C-5), 123.47 (C-8a), 122.51 (C-13a), 119.87 (C-8b), 117.85 (C-8), 102.63 (C-13), 101.99 (-OCH2O-), 101.16 (C-9). IR (ATR): ṽmax/cm-1 = 2904, 1449, 1237, 1036, 910, 860, 767, 754, 748, 704. HRMS (EI): calcd. for C22H14N2O2 (M)•+: 338.1050 found: 338.1051. HPLC purity: 95%.