1. Introduction

Cerebrocardiovascular disease(s) (CCVD) including coronary artery disease, ischemic heart disease, and stroke are the leading cause of mortality globally and are a major cause of disability [

1,

2,

3]. Further, central conduit extracranial vascular arterial stiffness/stiffening (VAS) as measured using carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV), is an independent predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [

4,

5]. Multiple risk factors for the development of VAS include advancing age [

5,

6,

7]; essential hypertension (HTN) [

6,

8]; metabolic syndrome (MetS) [

9]; diabetes-specifically type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and insulin resistance (IR) [

10,

11,

12]; obesity [

13,

14], unhealthy lifestyles such as smoking [

15], physical inactivity-sedentary lifestyle [

16], and high salt, high caloric intake as occurs with the diet-induced obesity Western style diets [

17,

18]. Importantly, note that the risk factors for the development of VAS parellel the risk factors for the development of CCVD [

19,

20]. Also, VAS may begin in youth to middle age and some have even reported that VAS may preceed the development of HTN and metabolic risks in youth [

21].

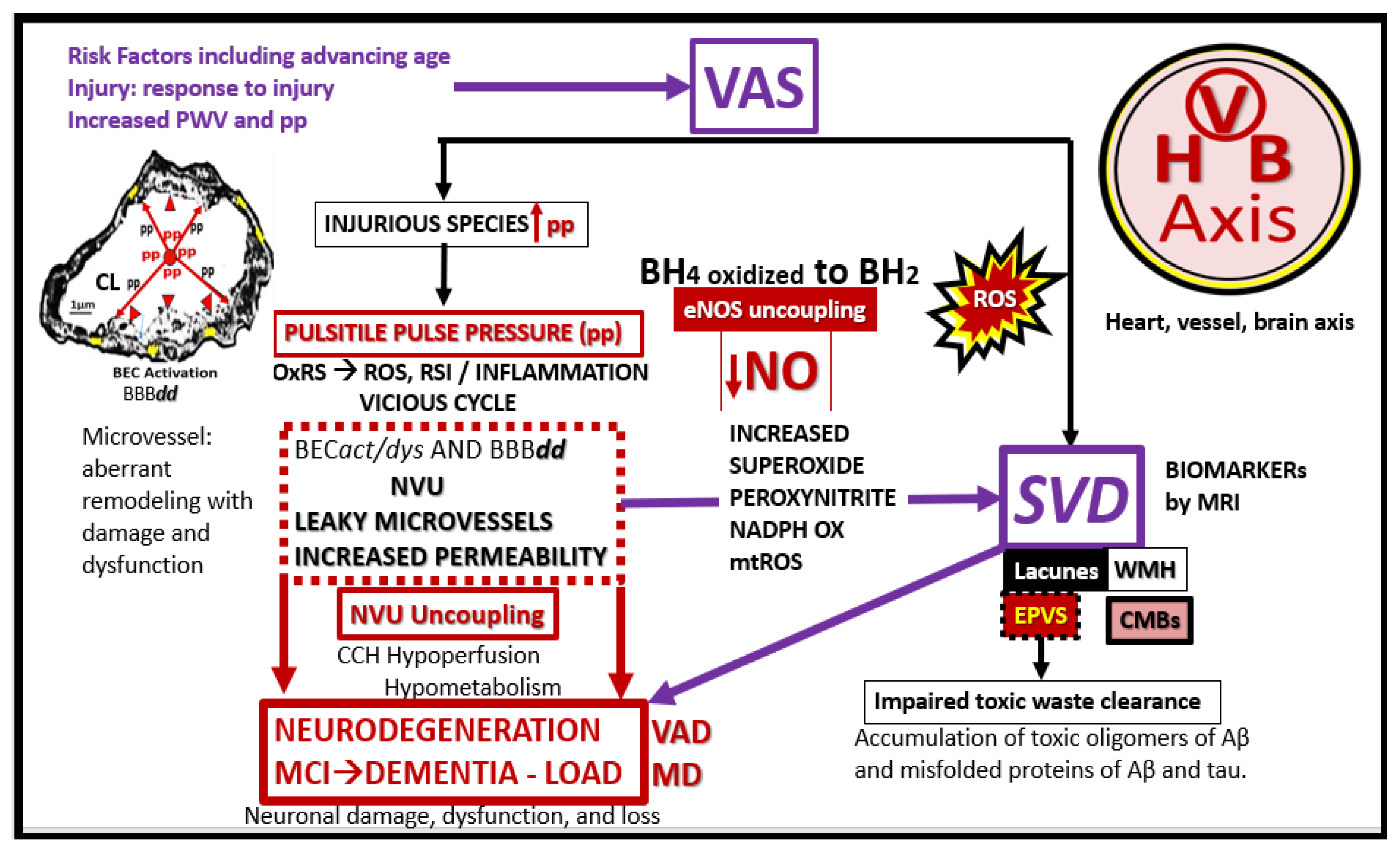

Recent evidence obtained from preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated an intricate connection between extracranial atherosclerotic vascular disease, HTN and VAS in the peripheral circulation [

22]. Further, VAS and subsequent cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) with its association to brain endothelial cell activation and dysfunction (BEC

act/dys) and blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction and disruption (BBB

dd) of the neurovascular unit (NVU) with increased permeability result in neurodegeneration and the development and progression of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) [

22,

23]. The findings of systemic extracranial atherosclerosis, vascular ossif ication-calcification remodeling, MetS, and HTN inclusive of both essential and the more predominant isolated systolic hypertension are frequent predisposing factors for the development of VAS [

6,

8,

22,

23].

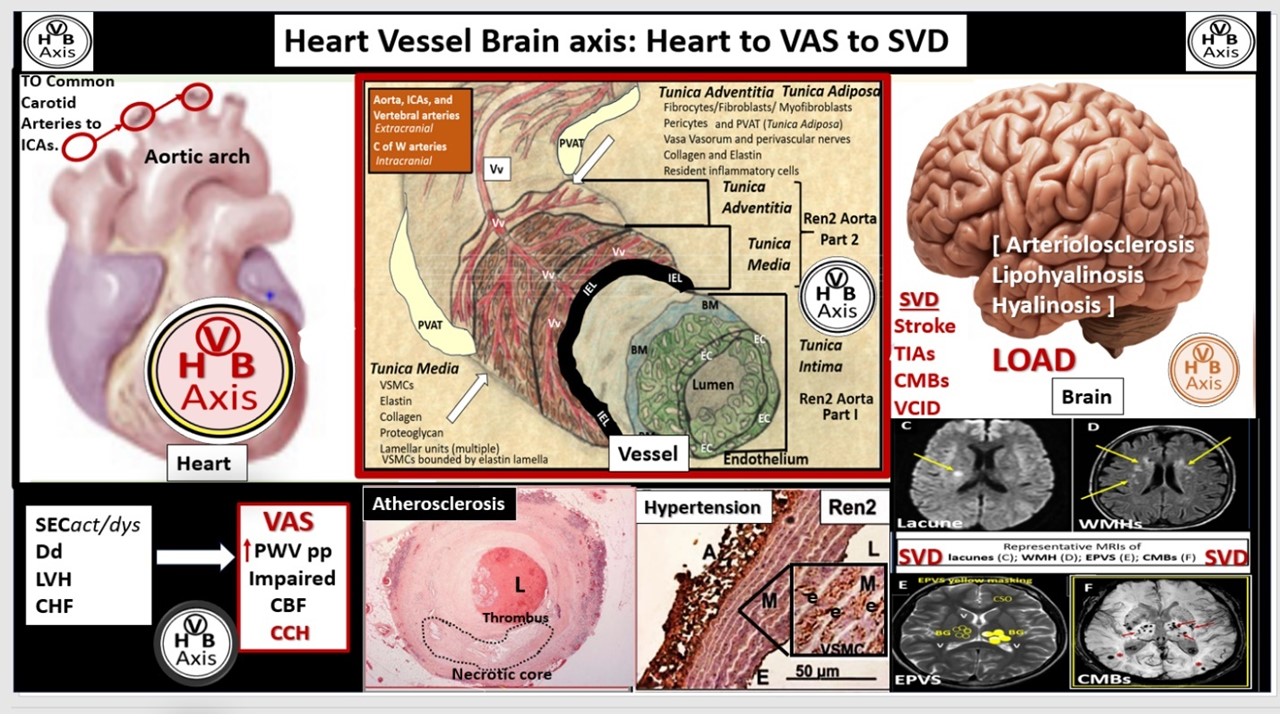

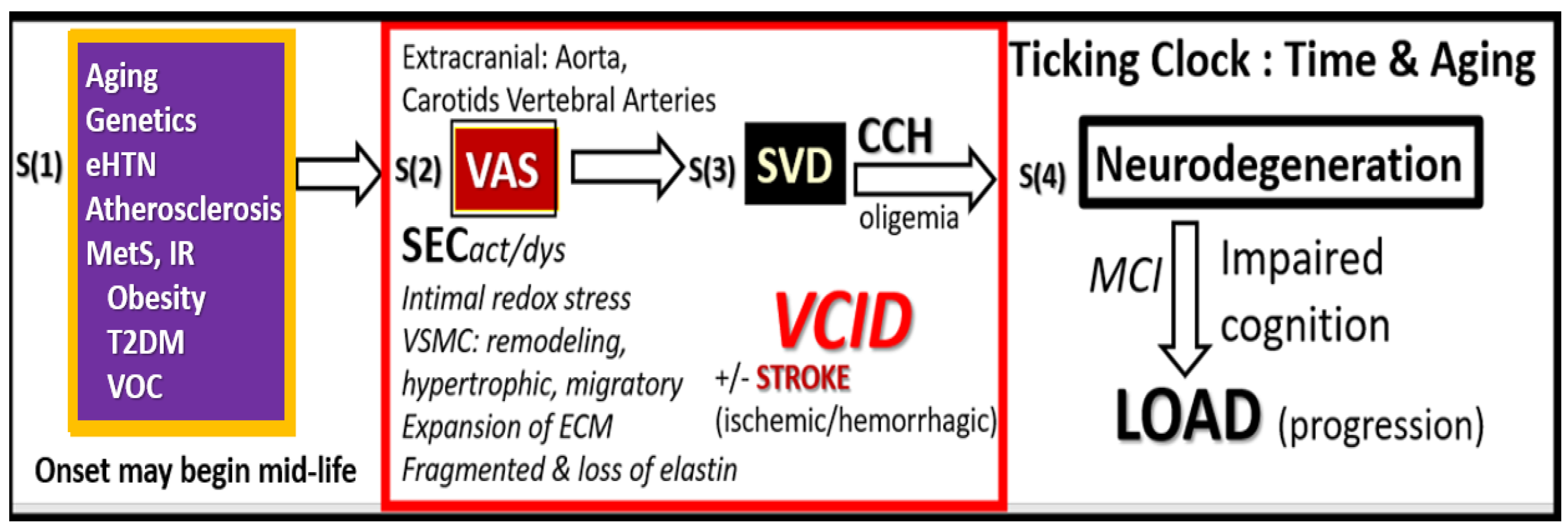

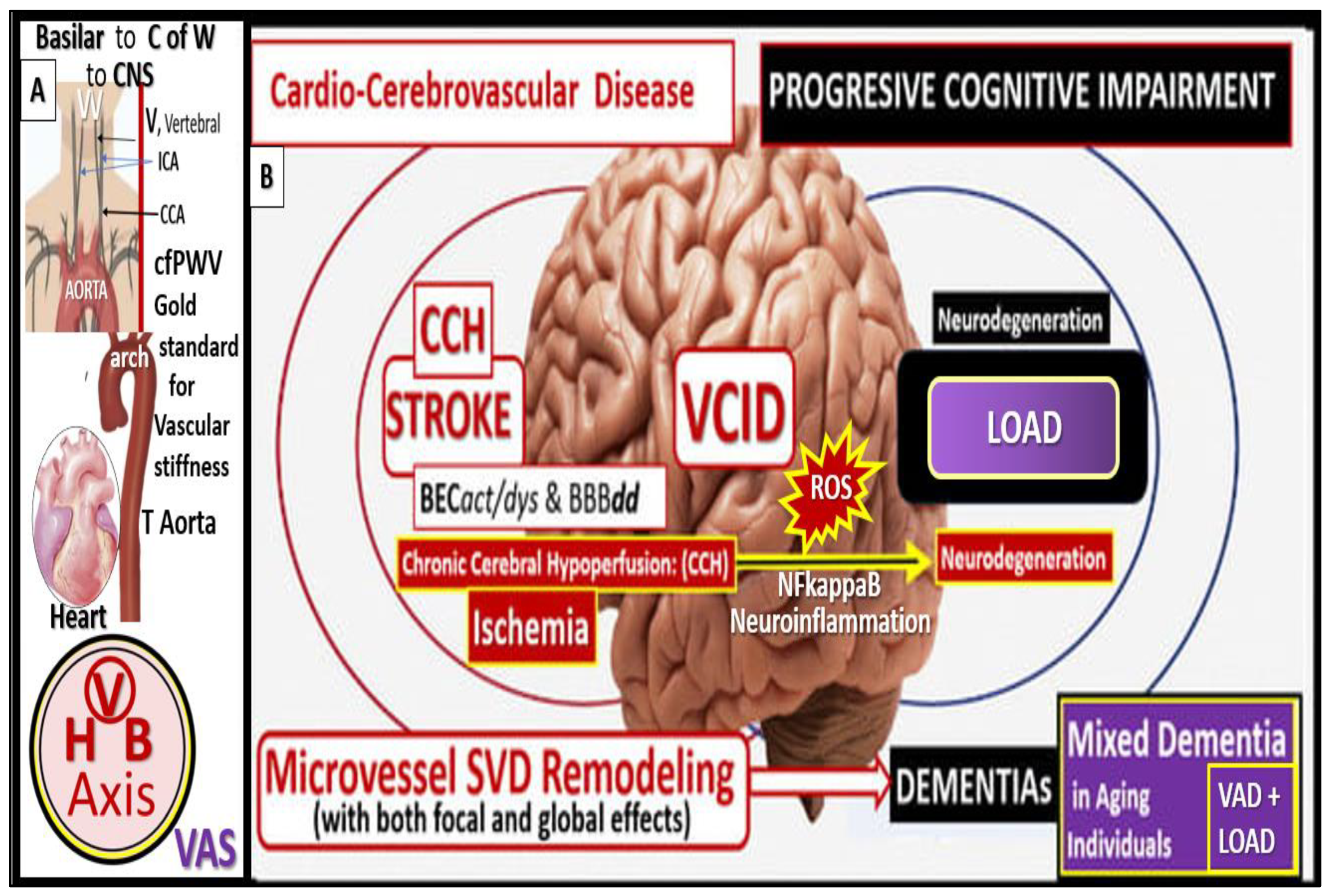

The damaging effects of increased pulsatile pulse pressure (pp) due to VAS is known to be one of the many injurious stimuli to both the systemic and brain endothelial cells, which result in the development of SVD, neurodegeneration, and LOAD to support a heart-vascular-brain (HVB) axis (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) [

24,

25,

26,

27].

Importantly, neurovascular remodeling and impairment of neurovascular integrity develop due to the brain’s known high flow and low capillary resistance [

22,

23,

28]. Therefore, it is important to explore the existing tight relationship between aging, hypertension, plus the multiple risk factors for the development of VAS to better understand this complex disease process and apply interventions that might mitigate the increased risk of microvessel remodeling and SVD, in order to maintain the cognitive abilities in the increasingly aging global population and the development and progression of LOAD.

2. Advancing Age and Essential Hypertension (HTN)

Avancing age is the strongest risk factor for the development of VAS [

29]. Fatigue and failure from increased pp associates with chonic wall stress that associates with stiffening of systtemic endothelial cell(s) (SECs), elastin fragmentation and loss of the internal elastic lamina and elastin lamellar units with increased collagen stiffening, VSMC stiffening, and the accumulation of advanced glycation endproducts (AGE) and its receptor (RAGE) with increased reactive oxygen species with increased matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) throughout advancing age (30). Aging is associated with a decrease in elastin and increased stiffer collagen within arterial vessels and an increase in PWV with increased pp [

29,

30]. Advanced aging is followed by HTN, which is the second most common cause of VAS [

30].

HTN also increases in prevalence with advancing age and advanced aging and HTN are the two main detrminants of VAS [

30,

31]. Importantly, HTN and VAS are intricately related with bidirectional effects, in that HTN increases VAS and VAS increasingly affects HTN [

32]. HTN results in a direct increased mechanical stress and injury to the vascular wall, which includes systemic endothelial activation and dysfunction (SECact/dys) with a proinflammatory phenotype and decreased nitric oxide bioavailability, oxidative redox stress (OxRS), inflammation, inceased stiffer collagen and elastin degradation and loss of recoil with loss of elastin lammelar units, and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). In a like manner VAS results in a decreased buffering-cushioning effect of the vessel wall, premature arrival of the reflected pulse wave that results in increased systolic blood pressure and increased pp, which results in SEC injury that results in a response to injury wound healing mechanism with stiffer collagen accumulation, fibrosis, and elastin fragmentation-related vascular ossification and calcification (VOC) [

32]. Further, aging-related HTN may be characterized by a significant increase in systolic blood pressure with little or no change in diastolic blood pressure or even lowering of diastolic blood pressure that it termed ISH [

33]. Also, aging associates with increased effects on the MetS and the neurohomormonal axis with increased nervous system activity, increased aldosterone and salt sensitivity that both result in increase vascular inflammation with increased tumor necrosis alpha (TNFalpha), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1(MCP-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and increased leukocyte infiltration of SECs, which contribute to VAS and subsequent HTN (

Figure 3) [

33].

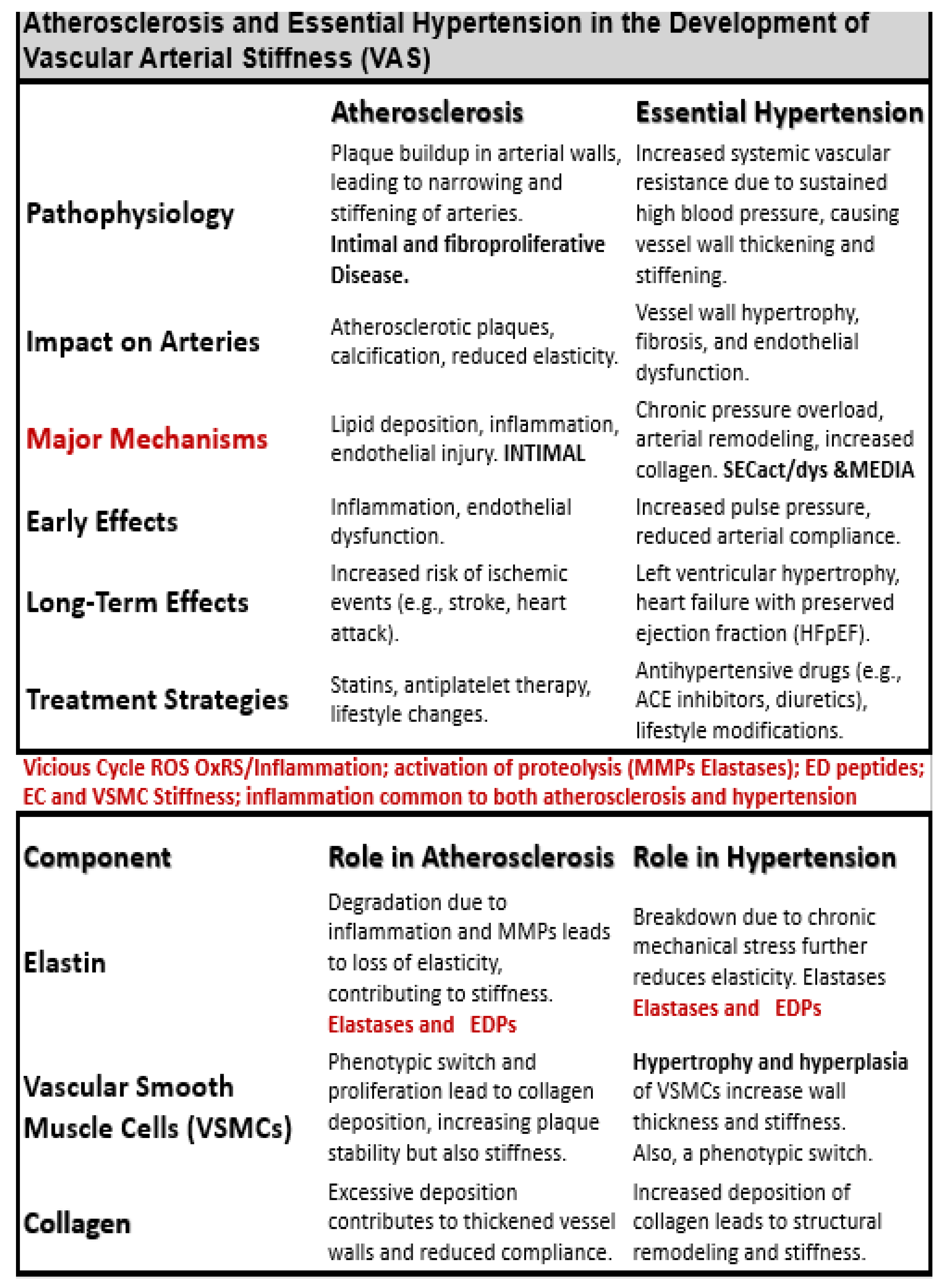

Many decades of research have implicated HTN and atherosclerosis as potential modifiable risk factors in the development of VAS, SVD, stroke, with neurodegeneration and LOAD [

34,

35]. Indeed, both atherosclerosis and HTN are implicated in the development and progression of VAS and SVD; however, they frequently co-exist and may be present simultaneously especially in older individuals. Therefore, it is appropriate to compare and contrast how they each are implicated in the development of VAS to result in SVD (

Table 1) [

6,

36,

37].

Additionally, multiple risk factors for the development of atherosclerosis and eHTN including the MetS play an important role (

Figure 4) [

37,

38].

Atherosclerotic calcifications are the most common form of calcific vasculopathy [

39]. Plus, vascular calcifications occur in both atherosclerosis and HTN; however, calcification is more strongly associated with atherosclerosis with increasing VAS. Also, HTN is more strongly associated with SVD since HTN is more commonly associated with microvessels in the brain as compared to atherosclerosis [

6,

40].

Importantly, studies show that HTN is linked to brain amyloid beta (Aβ) deposition in older adults and suggest that VAS plays a central role in this relationship [

41,

42,

43,

44]. VAS consists of a reduced capacity of arteries to expand (impaired vasodilation) as a result of stiffness, which impairs their ability to accommodate or cushion the increase in pressure from blood and ejection pressure from the heart during systole. Thus, VAS with decreased compliance allows for the transmission of increased pulsatile pulse pressure deeper into the periphery and microvessels of the distal-end organ systems microvessels present in the brain with high flow and low resistance. Regardless, VAS due to the effects of HTN and atherosclerosis appears to be an important risk factor for the development of SVD, which allows for the unification of several clinical phenotypes including SVD, cerebrovascular disease, stroke, neurodegeneration, impaired cognition, dementia, and LOAD. Indeed, VAS may be considered a potential modifiable risk factor that may even be considered as a nexus for the development of neurodegeneration and LOAD via BEC

act/dys, BBB

dd, OxRS, neuroinflammation, and SVD (

Figure 5) [

1,

2].

3. Atherosclerosis of Extracranial Aorta, Carotids, and Vertebral Arteries

Atherosclerosis is a leading cause of vascular disease (cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular disease) globally [

45] and is significantly associated with LOAD when utilizing carotid intima-media thickness to assess the degree of atherosclerosis [

46]. Additionally, atherosclerosis is a systemic chronic, progressive, and dysfunctional endothelial-intimal disease associated with SEC

act/dys that initially occurs at bifurcations and regions of turbulent blood flow. Atherosclerosis typically begins at the extracranial iliac arteries, femoral bifurcations, aorta, and progresses cephalad over time to involve the coronaries, carotids, and vertebral extracranial arteries that eventually progress to the branching cranial arteries extending from the circle of Willis and its arterial branches to the larger pial arteries of the brain where the smaller arterial microvesssels develop mostly arteriolosclersis, hyalinosis or lipohyalinosis [

3,

27,

47,

48]. Atherosclerosis is also a focal occurring, chronic proinflammatory (a definite driving force of atherogenesis), fibroproliferative, angiogenic, prothrombotic, multifactorial disease beginning in the arterial intima that is facilitated by multiple injurious species as in

Figure 1 and especially the penetration and retention of atherogenic modified-oxidized low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (modLDL-C/small dense LDL-C particles and oxLDL-C), triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and low high density lipoproteins (HDL-C) of the atherogenic lipid triad phenotype, hemodynamic, OxRS, inflammation via a monocyte to foamy lipid laden macrophage within the intimal space Once initiated in the intima the disease progresses to involve the vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) of the tunica media and the proinflammatory aspect of this disease now involves the uptake of inflammatory monocytes that eventually remodel to lipid-laden macrophage foam cells with further intimal growth that may eventually involve the tunica media via VSMC hypertrophy, proliferation, migration that associates with increased collagen and proteoglycans along with the fragmentation, degradation, and loss of elastin that contributes to VAS during the progression of atherogenesis (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) [

3,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54].

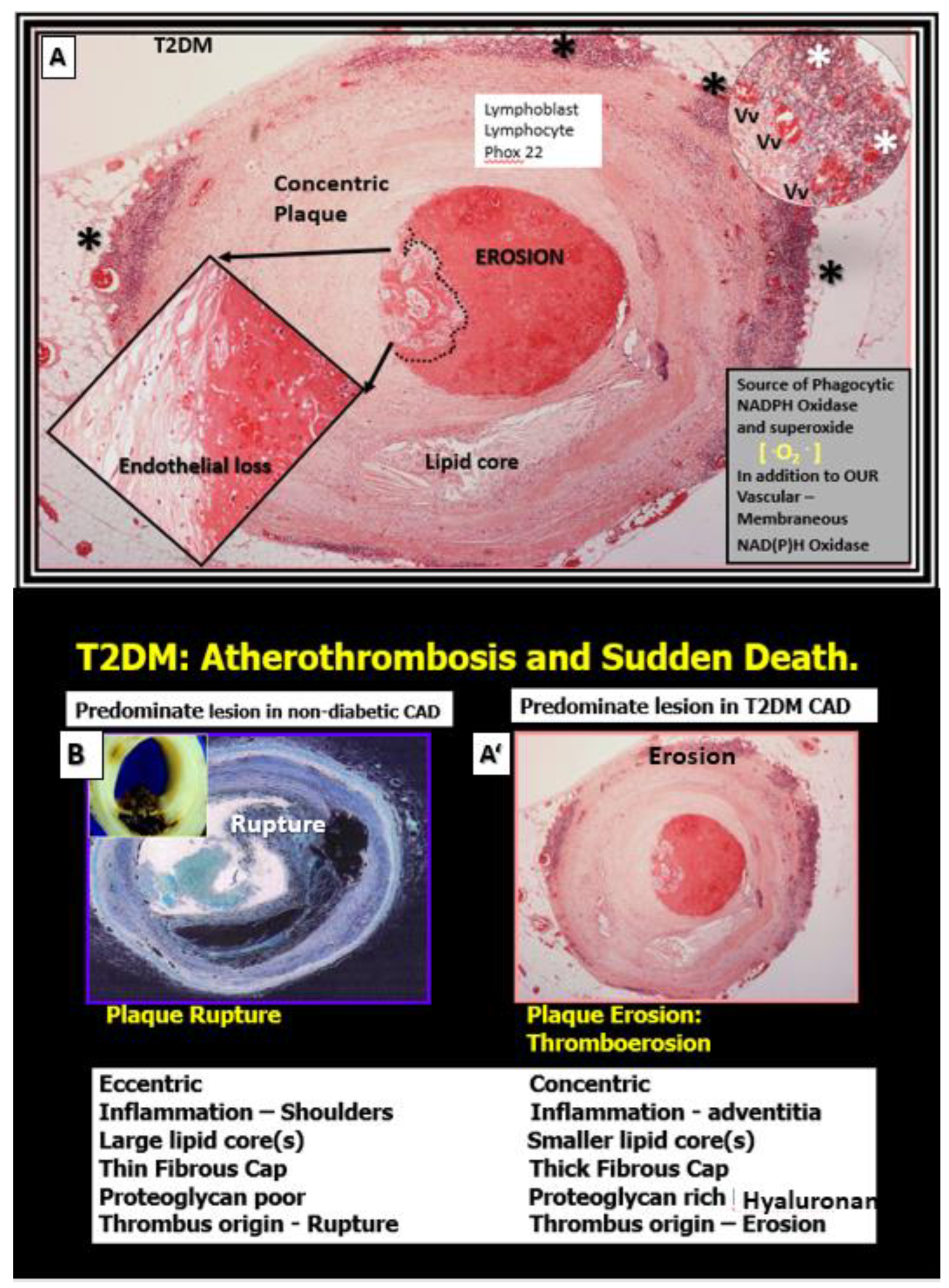

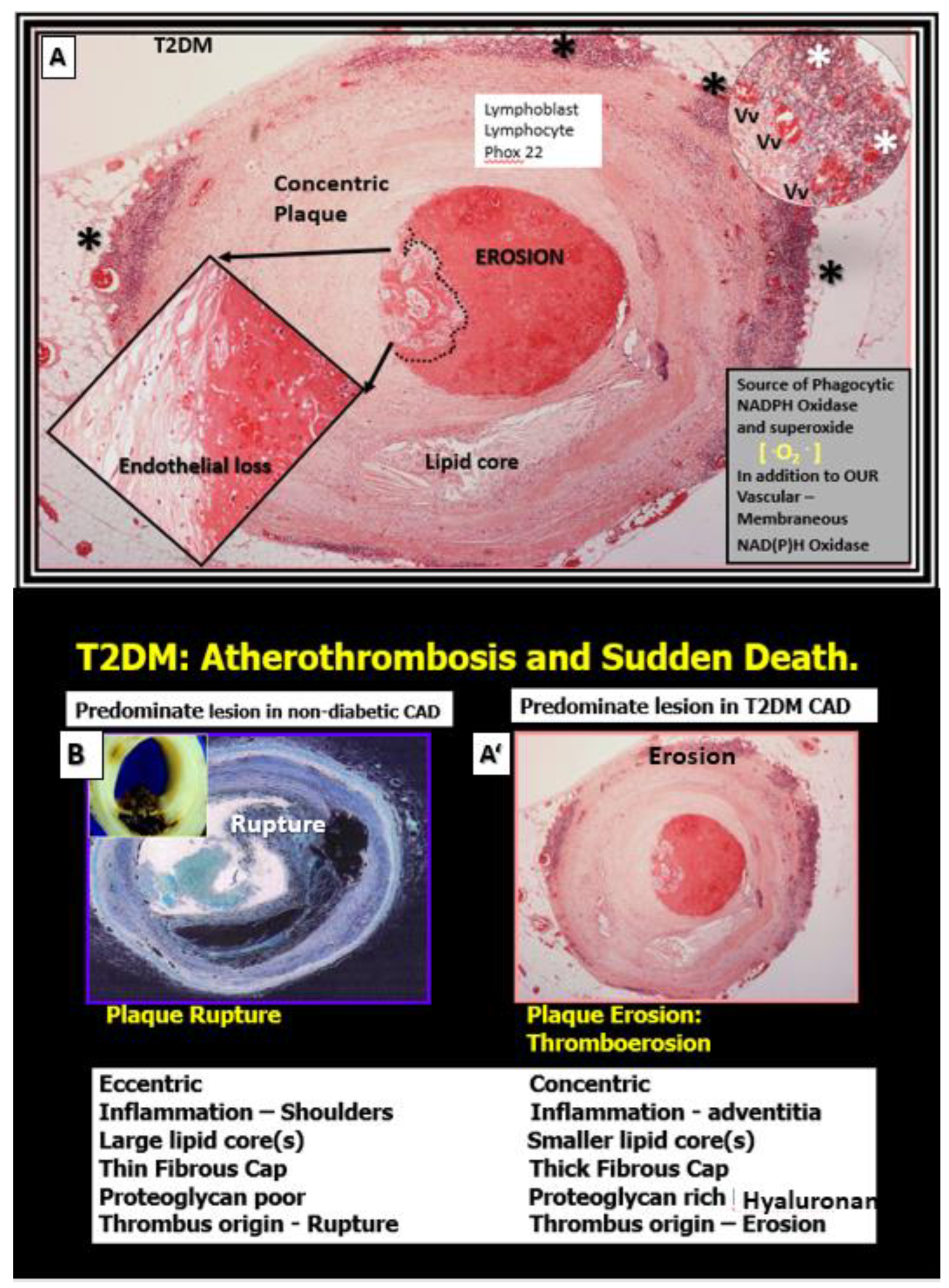

There is convincing evidence that T2DM and the MetS are associated with greater arterial stiffness and atherosclerosis as compared to non-diabetic individuals [

55]. Importantly, this increased VAS may at least in part, help to explain the increased CCVD risk in individuals with diabetes and the MetS (

Figure 7) [

55,

56].

Figure 7.

Comparison of non-diabetic plaque rupture to diabetic (T2DM) plaque erosion to result in atherothrombosis and sudden death. Panel A depicts an erosive plaque in a 58 year old female individual with history of T2DM, obesity, hypertension, and previous stroke who presented with acute ventricular tachycardia and sudden death due to a left mid-anterior descending coronary occlusion with an erosive concentric plaque. Note the extensive mononuclear vasculitic type adventital infiltrate associated with this concentric erosive thrombotic plaque. While each of these vulnerable plaques in panel B and A’ associate with increased extracranial vascular arterial stiffness they may result in similar clinical outcomes, i.e., sudden death due to atherothrombosis. Non-diabetic plaques are more prone to rupture while T2DM individuals are more prone to develop thromboerosion and result in sudden death. Additionally, T2DM individuals are known to have increased vascular stiffness as compared to non-diabetic individuals. Panels A and A’are hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Panel B is H&E stained (pseudo-colored blue in order to contrast colors with A and A’). Modified images provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

56]. Asterisks, vasculitic lymphocytic infiltrate within the adventita; CAD, coronary artery disease; P22 Phox (underlined in red), is the light chain of the NADPHOx enzyme and its positive staining strongly suggests increased oxidative stress within the plaque and the adventitia that may contribute to plaque instability and erosion in T2DM; Vv, vasa vasorum.

Figure 7.

Comparison of non-diabetic plaque rupture to diabetic (T2DM) plaque erosion to result in atherothrombosis and sudden death. Panel A depicts an erosive plaque in a 58 year old female individual with history of T2DM, obesity, hypertension, and previous stroke who presented with acute ventricular tachycardia and sudden death due to a left mid-anterior descending coronary occlusion with an erosive concentric plaque. Note the extensive mononuclear vasculitic type adventital infiltrate associated with this concentric erosive thrombotic plaque. While each of these vulnerable plaques in panel B and A’ associate with increased extracranial vascular arterial stiffness they may result in similar clinical outcomes, i.e., sudden death due to atherothrombosis. Non-diabetic plaques are more prone to rupture while T2DM individuals are more prone to develop thromboerosion and result in sudden death. Additionally, T2DM individuals are known to have increased vascular stiffness as compared to non-diabetic individuals. Panels A and A’are hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Panel B is H&E stained (pseudo-colored blue in order to contrast colors with A and A’). Modified images provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

56]. Asterisks, vasculitic lymphocytic infiltrate within the adventita; CAD, coronary artery disease; P22 Phox (underlined in red), is the light chain of the NADPHOx enzyme and its positive staining strongly suggests increased oxidative stress within the plaque and the adventitia that may contribute to plaque instability and erosion in T2DM; Vv, vasa vasorum.

Interestingly, not only does the elevated glucose in T2DM cause an increase in AGE, which promotes collagen crosslinking but also interacts with its receptor RAGE and gives rise to increased OxRS that can increase the fragmentation of elastin within the media. Concurrently, this increase in glucose and AGE instigate a phenotypic switch in the VSMCs of the media from a contractile type to a synthetic type that increases the synthesis of stiffer collagen and also hyaluronon ECM components as in

Figure 7 to result in increased VAS [

57].

Even though atherosclerosis is defined as being a chronic progressive intimal disease, it is important to note that even when there is continued atheroma lipid expansion that these lesions do not usually become clinically symptomatic unless there are superimporsed progressive remodeling changes including the deposition of thrombotic material (introplaque hemorrhage), inflammation, calcification, and malignant-like invasion via angiogenesis of the atheromatous plaque with plque hemorrhage and rupture [

47,

51].

Vascular Ossification/Calcification (VOC)

VOC may be defined as the deposition of calcium phosphate complexes in the form of hydroxyapatite [Ca

10(PO

4)

6(OH)

2] in vessels, which result in increased VAS [

58]. While VOC of arteries is one of the characteristics of vascular aging [

59,

60], it also is capable of being increased in pathological processes such as HTN, diabetes, CKD, and hereditary disorders (

Figure 8) [

61,

62,

63].

VOC may occur at different locations (intimal or media calcificaitons or both) in the arterial wall that are known to be associated with different risk factors and outcomes [

58,

64]. Indeed, arterial calcification is no longer thought to be just a passive process associated with aging, but involves a reporgramming of the media VSMCs from a contractile state to a synthetic proliferative and migratory phenotype capable of becoming an osteogenic cell within the media and intima [

63,

65]. Importantly, these local VSMC cues are different for atherosclerotic aortic intimal calcification, which involves inflammation, OxRS, and apoptosis in contrast to medial calcification that associates with aging, HTN, senescence, and uremia of renal failure with multiple elevations of uremic toxins and specifically elevated calcium and phosphate levels [

62,

65]. Interestingly, elastin dedradtion/fragmention results in the release of bioactive elastin degradation products (EDPs), which are capable of inducing an osteogenic switch of VSMCs from a contractile to a synthetic phenotype and once switched these cells are capable of producing calcification in the tunica media that have a prediletion to adhere to these damaged elastin lamella within either the media or the elastin of the internal elastic lamina (IEL) of intima regions [

66]. Importantly, McEniery et al., have pointed out that in both preclinical animal and human studies that arterial calcification is associated with aortic stiffness and HTN [

67].

4. Endothelial Interface: Systemic Endothelial Cells (SECs) and Brain Endothelial Cells (BECs)

The brain endothelial functional interface is highly selective and acts as a continuous monolayer of gatekepper BECs with barrier functions that provide tight (specialized occludin, claudin, junctional adherens molecule proteins) and adherens junctions (VE-Cadherins) to create a BBB and prevent paracellular trafficking. Importantly, the BEC interface with its most luminal layer of extracellular matrix (ECM) termed the endothelial glycocalyx (ecGCx) that serves as a protective shield to the vessel contents [

68,

69] are known to initially separate the circulating blood from the CNS cells and interstitial fluid and are also known to have a paucity of pinoyctosis [

70,

71].

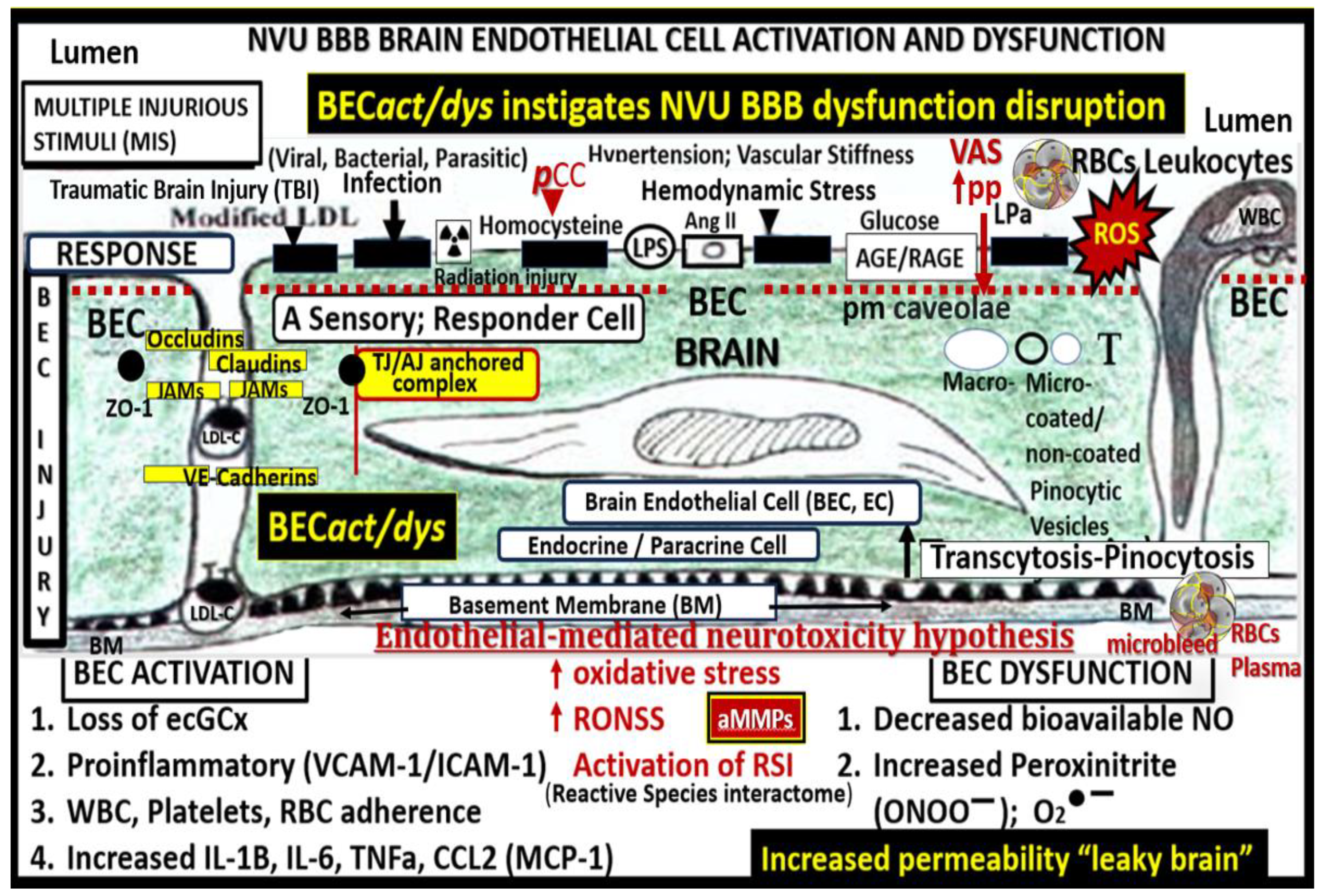

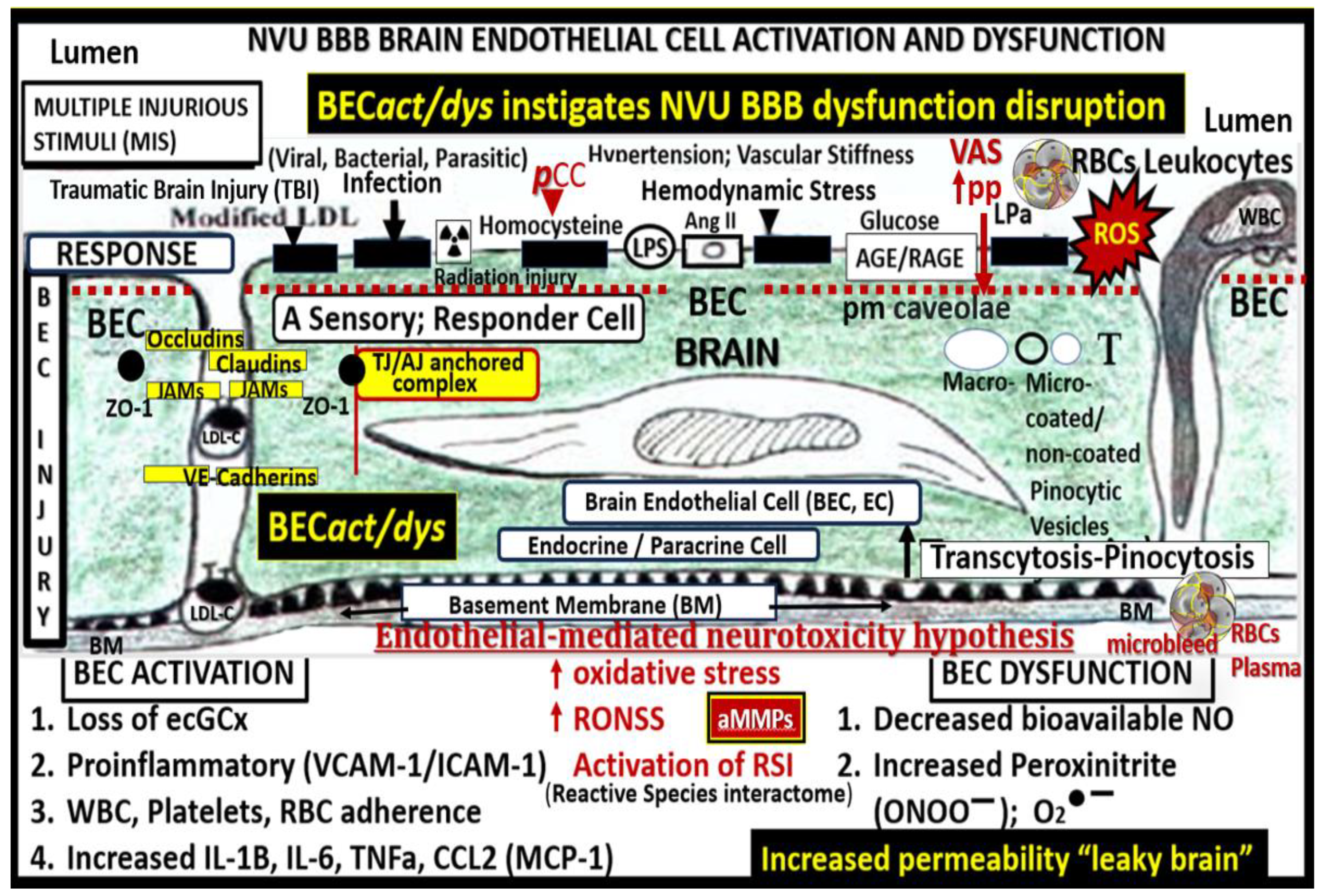

SECs and BECs activation indicate an endothelial proinflammatory response, while SECs and BECs dysfunction indicate a decrease in protective (antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic, and vasodilation effects) bioavailable nitric oxide (NO) [

36,

53,

72]. The peripheral SECs are constantly being exposed to numerous injurious stimuli as in

Figure 1, which are capable of inducing SEC

act/dys. These exposures are known to instigate SEC activation resulting in a proinlammatory endothelium that is not only responsible for the increased delivery of leukocytes to the central nervous system (CNS) neurovascular units BBB with increased permeability but also deliver increased peripheral cytokines and chemokines (

pCC). Further, these increased

pCC associate with endothelial dysfunction and decreased NO with increased OxRS and neuroinflammation, which eventually create a double vicious cycle between OxRS and inflammation via the nuclear factor-kappa B in SECs and at the NVU BEC BBB interface (

Figure 9) [

72].

Notably, these double vicious cycles in

Figure 5 contribute to a proconstrictive state at the precapillary arterioles and true capillary of the NVU in addition to leukocyte adhesion and even stalling of cerebral blood flow. Also, advanced glycation endproducts and their receptors (AGE/RAGE) activation result in increased OxRS that in turn activates local MMP-2, 9 with increased proteolysis including the BBB tight and adherens junctions with resulting increased permeability. These changes contribute to endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) uncoupling and decreased NO bioavailability with hypoperfusion and hypometabolism to regional neurons with neurodegeneration, impaired cognition, brain atrophy and LOAD.

NO synthesized and secreted by SECs and BECs is known to function as a vasculo-protectant, in that, it has antiplatelet, antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, antiatherosclerotic and vasorelaxant effects as a gasotransmitter synthesized by the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) enzyme. NO is capable of undergoing paracrine signaling to the immediate surrounding pericytes (at the level of capillary NVUs) and vascular smooth muscle cells (at the level of arterioles and arteries) to result in vasorelaxation due to its activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase to increase the synthesis of 3,5-cyclic guanosine monophosphate [

73].

Decreased NO bioavailability as occurs in CCVDs due to endothelial dysfunction is due largely to eNOS uncoupling, wherein increased OxRS results in the excessive oxidation of the essential coenzyme tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) to the ineffective dihydrobiopterin (BH2). Notebly, the eNOS reaction will only run if its essential coenzyme is fully reduced to its BH4 moiety. Also, elevated asymmetrical dimethyl arginine (ADMA), a known competitive inhibitor of eNOS enzyme reaction) is capable of decreasing bioavailable NO [

72,

73]. Indeed, SEC and BEC dysfunction with decreased bioavailable NO sound an alarm not only to the SECs and BECs but also other supportive cells of extracranial arteries (VSMCs) and the microvessel NVU mural supportive cells (Pcs and connecting astrocyte endfeet of NVU) as well as the CNS cells (

Figure 10) [

25,

73].

ECs (SECs and BECs) are the first cells to be exposed to multiple injurious species as in

Figure 1 and

Figure 6 and they react to these injuries with an injury response that has multiple phases resulting in structural and functional responses. Over the past decade authors have observed at least 10 ultrastructural remodeling phenotypes in the thoracic aorta and NVU ECs in various models that associate with BEC

act/dys, BBB

dd, SVD, and VAS in aortic ECs and microvascular NVU BECs from various models (

Figure 11) [

25,

26,

27].

Western Diet-Induced Obestity Is Also Known to Contain a High-Salt Component That Increases VAS

Importantly, the heavily consumed Western diet is consistently known to have not only a high fat and carbohydrate component but also a high sodium-salt component that also contributes to an increase in VAS [

74,

75]. Elevations of sodium chloride in the Western diet are toxic to the vascular endothelium and are known to result in endothelial glycocalyx dysfunction and damage with attenuation and/or loss, EC OxRS, EC

act/dys that induces a proinflammatory endothelium with decreased NO bioavailablity, activation of MMP-2, 9, TGFβ, transglutaminase 2, elastin fragmentation and increased collagen with decreased elastin/collagen ratio and crosslinking in addition to activating the RAAS and increase AT-1 receptors along with increased endothelial sodium channel (eNAC) actiity to promote VAS as illustrated in

Figure 10 [

74,

75,

76].

5. Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) Role in the Development of VAS

The MetS is a metabolic disorder that consists of a cluster of multiple risk factors including hyperlipidemia (obesity), hyperinsulinemia (IR), essential HTN, hyperglycemia (impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and T2DM and associated variables. In addition to paralleling the obesity epidemic, the MetS associates with an increased risk for the development of T2DM and cerebrocardiovascular disease [

38]. Each of the previous four H (horsemen) risk factor clustering, in addition to the MetS itself, play an important role in the development of VAS and LOAD [

9,

77,

78]. MetS is a strong predictor of CCVD disease and VAS, which is increasingly being recognized as a CCVD risk factor, plus components of the MetS are capable of interacting to synergistically impact carotid intimal media thickness and VAS (

Figure 12) [

78,

79].

While the MetS may be viewed as a risk syndrome, it provides a definite platform for the clustering of multiple risk factors and variables that is now known to associate with VAS and this not only helps to broaden our knowledge but also to further bridge the relationship of MetS, VAS, SVD, and neurodegeneration as outlined in the sequence of events as previously outlined in

Figure 2 and

Figure 5.

6. Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Elastin, Elastin-Derived Products (EDPs), Collagen, and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs) of the Arterial Tunica Media in Vascular Arterial Stiffening (VAS)

In addition to structural remodeling and functional changes in the ECs, VAS also develops due to remodeling alterations in the vascular extracellular matrix characterized by a degraded and fragmented decrease in the elastic recoil protein elastin via elastinolysis and an increase in the stiffer organized collagen via increased synthesis by media VSMCs [

50,

80]. These findings are further facilitated by the processes of OxRS, inflammation/metainflammation, and AGEs with increased collagen crosslinking that lead to decreased elasticity and vessel compliance with increased PWV and pp [

80,

81]. The VSMCs also develop a synthetic phenotype responsible for increased synthesis of stiffer collagen and proteoglycans (PGNs) that become synthetic, hypertrophic, and capable of migration in contrast to normal contractile phenotypes, termed phenotypic switching (

Figure 13) [

50,

82].

The ECM of the arterial tunica media is composed of elastin, collagen, glycoproteins and proteoglycans, which confers tensile strength and provides viscoelasticity of the conduit arterial vessel walls [

83,

84,

85]. Importantly, when the elastin undergoes elastolysis there is the generation of elastin-derived fragments that are a rich source of EDPs [

85,

86,

87]. Elastic fibers can be degraded and fragmented by mechanical fatigue, calcification, glycation, lipid peroxidation, and importantly, protease-elastase digestion with fragmentation-degradation [

88]. Elastolysis-elastin degradation is due primarily to elastases that are comprised by MMPs (MMP-2, 7, 9, and 12) and cathepsin cysteine proteases, such as cathepsin S that are activated in response to OxRS primarily generated within the vessel by EC

act/dys, activated macrophages, and synthetic VSMCs (

Figure 14) [

85,

86,

87,

88,

89].

It is known that VSMCs become stiff similar to ECs when examined by atomic force microscopy measurements in addition to increasing synthesis of stiffer collagen and PGN [

83]. This VSMC stiffness contributes to the overall global increase in aortic stiffening with aging. Notably, this VSMC stiffness is in addition to the fragmentation of elastin with the loss of elastic recoil, increased collagen and PGN synthesis by the synthetic VSMC phenotypes and the stresses placed upon the VSMCs due to mechanotransduction [

83,

84]. Phenotypic switching from contractile to synthetic, proliferative, and migratory VSMC in VAS allows these migratory VSMC to become mobile and tranverse the media to the IEL where they are capable of degrading the IEL and create a neointimal subendothelial space [

90,

91]. In the Ren2 models, angiotensin-II (AngII) elevation and OxRS are important for the invasive nature of the IEL with the creation of the neointima (

Figure 15) [

50].

The phenotypic switch of the VSMCs in hypertension and diabetic obese models as in

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 result in the degradation of elastin lamella and the IELresulting in the EDFs and the production of bioactive EDPs [

92]. Bioactive EDPs (matrikines-elastokines) and interactions with their receptior elastin receptor complex (ERC) result in multiple functions that contribute to VAS. EDPs promote inflammation; react with RAGE to increase ROS, NFkappaB, and MMP activtation; activate cytokines including TNFα and IL-6; increase crosslinking of collagen; promote VSMC phenotypic switching. These contributions amplify further elastin degradation all of which, promote VAS in CCVDs [

88,

92,

93].

At this juncture it is noteworthy to point out that transglutaminase 2 (TG2) is an enzyme ubiquitously expressed in the vasculature, which promotes the synthesis and crosslinking of extracellular matrix collagen. Increased transglutaminase 2 (TG2) is a known collagen crosslinker that associates with VAS and affects the extracellular matrix by increasing collagen deposition, and crosslinking (in a calcium-dependent manner) that has been long recognized as critical player in vascular stiffening [

94,

95]. In this regard it is notable that Ramirez-Perez et al. were able to show that cystamine (a nonspecific TG2 inhibitor) was able to reduce vascular stiffness in Western diet-fed female mice; however, they did not determine the extent of these findings in regards to the role of cystamine also being a antioxidant that could also contribute to the vascular destiffening effects in these models [

95].

7. Conclusion and Future Directions

Recently, there has been considerable epidemiological, clinical-pathological and basic science observations that has allowed the research community to reconsider the important role of vascular factors in cognitive impairment. These observations have made it possible to now identify vascular dysfunction and damage (including VAS and SVD) as being critical components of the pathophysiology of age-related dementias including LOAD (

Figure 16) [

96,

97,

98,

99].

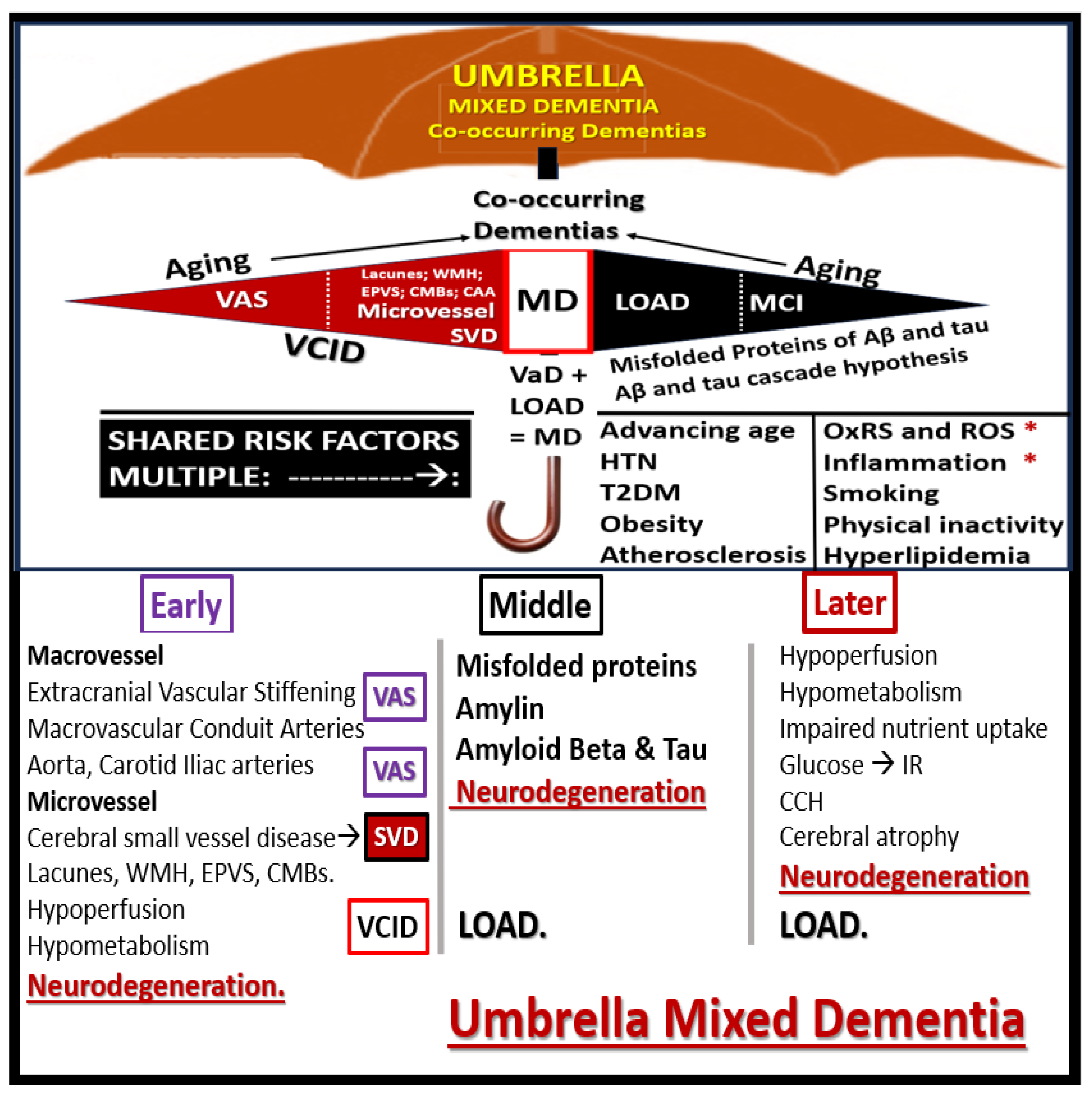

Over time there has been accumulating and consistent evidence that support and definitely implicate both VAS and SVD in the pathogenesis of impaired cognition, neurodegeneration, and dementia including LOAD (

Figure 17) [

27,

100,

101,

102].

Future directions regarding the importance of extracranial vascular stiffening (VAS) revolve around a resurrgance of interest regarding the role of not only VAS but also microvessel remodeling in the development of neurodegeneration as a co-occurance or mixed dementia (MD) of aging along with the LOAD type dementia. While the authors have focused on the importance of VAS throughout this narrative review, we posit that an integrative approach with somewhat of a paradigm shift of an umbrella approach be strongly entertained to examine this burgeoning age-related dementia (

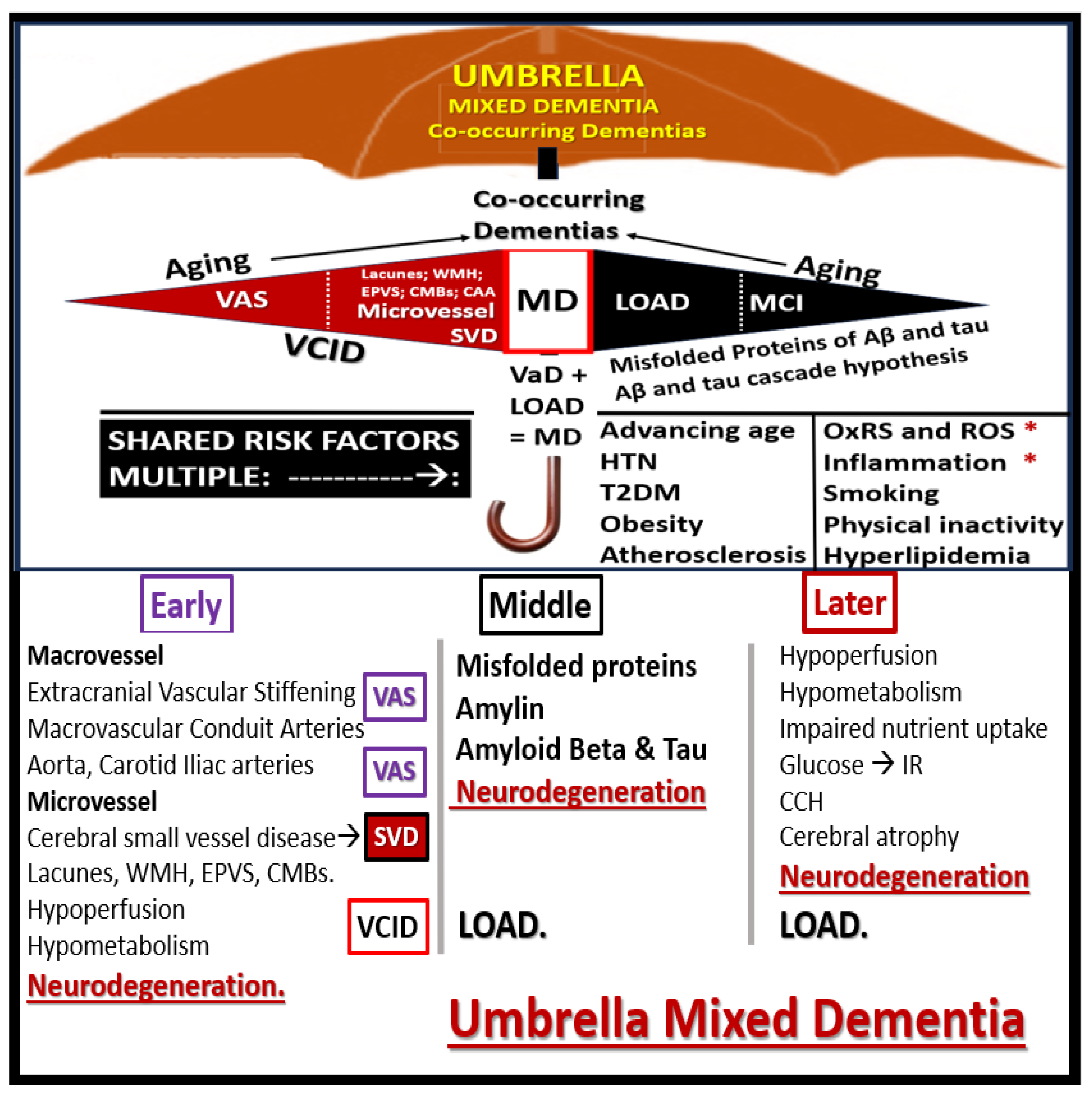

Figure 18).

It is suggested that this problem of age-related dementia be approached in an integrative manner without discriminating between being a strictly sporadic Alzheimer’s disease or LOAD and VaD and consider their co-occurrence as a MD, since they share so many similar risks factors. As the emerging knowledge continues to grow in the field of VCID and their emerging biomarkers (MarkVCID biomarker consortium:

https://markvcid.partners.org/about/news), it is felt that the co-occurrence of LOAD and VaD (i.e., MD) will continue to become a more futuristic concept allowing the MD concept to flourish [

103,

104].

Targeting multiple modifiable risk factors have become the main therapeutic strategy to improve arterial stiffness and the additional use of omega-3 fatty acid intake, RAAS antagonists, metformin, HMG-CoA reductase in hibitors have been found to be useful in those individuals with HTN and diabetes as well as those indivituals at high cardiovascular risk [

105]. In addition to metformin, both of the antidiabetic drugs (GLP-1R agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors) have the potential and have been shown to decrease VAS [

106,

107]. However, there is currently a lack of thereapeutic strategies specifically directed at the treatment of VAS. Notably, Ramirez-Perez, et al. found that cystamine (a non-specific TG2 antagonist with antioxidant effects) was able to reduce VAS in female Western diet-fed mice [

95] and these results may help to instigate future trials with other treatment modalities to specifically decrease VAS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.H.; methodology, M.R.H. and N.T.; software, M.R.H.; validation, M.R.H. and N.T.; formal analysis, M.R.H. and N.T.; investigation, M.R.H. and N.T.; resources, M.R.H.; data curation, M.R.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.H.; writing—review and editing, M.R.H. and N.T.; visualization, M.R.H.; supervision, M.R.H.; project administration, M.R.H.; funding acquisition, M.R.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Author has not received grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The tissues provided for the representative electron microscopic images utilized in this manuscript were all approved in advance by the University of Missouri Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (No. 190; 7 July 2017). The animals were cared for in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans Hospital and the University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA, which conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials can be provided upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Tatyana Shulyatnikova for the contribution of artistic illustrations and editing of this manuscript. The author would also like to acknowledge DeAna Grant Research Specialist of the Electron Microscopy Core Facility at the Roy Blunt NextGen Precision Health Research Center, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

Aβ, amyloid beta;AGE, advanced glycation endproducts; ADMA, asymmetrical dimethyl arginine; BBB, blood–brain barrier; BEC(s), brain endothelial cell(s); BECact/dys, brain endothelial cell activation/dysfunction; BBBdd, blood-brain barrier dysfunction disruption; BH4-BH2, tetrahydrobiopterin and dihydrobiopterin; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; CBF, cerebral blood flow; CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; CL, capillary lumen; CMB(s), cerebral microbleeds; CNS, central nervous system; cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines chemokines; HTN, hypertension; HVB, heart vessel brain; IL-6, interleukin-6; IR, insulin resistance; ECM, extracellular matrix; EDPs, elastin derived peptides; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ERC, elastin receptor complex; LOAD, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease; MCI, mild or minimal cognitive impairment; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattract protine-1; MD(s), mixed dementias; MetS, metabolic syndrome; MMP-2,-9, matrix metalloproteinase-2,-9; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mtROS, mitochondrial ROS; NADPH Ox, nicotine adenine diphosphate reduced oxidase; ND, neurodegeneration;, NO, nitric oxide; NVU, neurovascular unit; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; pCC, peripheral cytokines chemokines; PWV, pulse wave velocity; pp, pulsatile pulse pressure; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation endproducts; RAAS, renin angiotensin aldosterone system; Ren2, transgenic heterozygous (mRen2)27; transgenic heterozygous (mRen2)27 transgenic heterozygous (mRen2)27 transgenic heterozygous (mRen2)27 ROS, reactive oxygen species, RONS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen species; RONSS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur species; RSI, reactive species interactome; SECs, systemic endothelial cells; SECact/dys, systemic endothelial cell activation/dysfunction; SVD, cerebral small vessel disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; TEM, transmission electron microscopy;, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VaD, vascular dementia; VAS, vascular arterial stiffness; VCID, vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia; VOC, vascular ossification-calcification; VSMC(s), vascular smooth muscle cells; WMH, white matter hyperintensities.

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, G.A.; Roth, G.A.; Fuster, V. The global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors: 2020 and beyond. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019, 74, 2529–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecelja, M.; Chowienczyk, P. Role of arterial stiffness in cardiovascular disease. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis. 2012, 1, cvd2012012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.F.; Parise, H.; Benjamin, E.J.; et al. “Changes in arterial stiffness and wave reflection with advancing age in the Framingham Heart Study. ” Hypertension. 2004, 43, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safar, M.E.; Asmar, R.; Benetos, A.; Blacher, J.; Boutouyrie, P.; Lacolley, P.; et al. Interaction Between Hypertension and Arterial Stiffness. Hypertension. 2018, 72, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, J.A.; Andrés, V.; Castiglioni, S.; Giudici, A.; Lau, E.S.; Nemcsik, J.; et al. Aging and Vascular Disease: A Multidisciplinary Overview. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P.; Asmar, R.; Gautier, I.; Laloux, B.; Guize, L.; Ducimetiere, P.; Benetos, A. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2001, 37, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Vicente, W.R.P.; Rodrigues, S.; Cepeda, F.X.; Jordão, C.P.; Costa-Hong, V.; Dutra-Marques, A.C.B.; et al. Arterial stiffness and its association with clustering of metabolic syndrome risk factors. Diabetol Metabol Syndr. 2017, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.B.; Mitchell, G.F.; Gill, D.; Burgess, S.; Rahman, M.; Hanff, T.C.; Ramachandran, V.S.; Mutalik, K.M.; Townsend, R.R.; Chirinos, J.A. Arterial Stiffness and Diabetes Risk in Framingham Heart Study and UK Biobank. Circ Res. 2022, 131, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Huang, J.; Wu, T.; Qi, L. Arterial Stiffness, Genetic Risk, and Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2022, 45, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbina, E.M.; Gao, Z.; Khoury, P.R.; Martin, L.J.; Dolan, L.M. Insulin resistance and arterial stiffness in healthy adolescents and young adults. Diabetologia. 2012, 55, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safar, M.E.; Czernichow, S.; Blacher, J. Obesity, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006, 17, S109–S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroor, A.R.; Jia, G.; Sowers, J.R. Cellular mechanisms underlying obesity-induced arterial stiffness. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2017, 314, R387–R398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camplain, R.; Meyer, M.L.; Takana, H.; Palta, P.; Agarwal, S.K.; Aguila, D.; Butler, K.R.; Heiss, G. Smoking Behaviors and Arterial Stiffness Measured by Pulse Wave Velocity in Older Adults: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Hypertens. 2016, 29, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saladini, F. Effects of Different Kinds of Physical Activity on Vascular Function. J Clin Med. 2023, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Perez, F.I.; Cabral-Amador, F.J.; Whaley-Connell, A.T.; Aroor, A.R.; Morales-Quinones, M.; Woodford, M.L.; et al. Cystamine reduces vascular stiffness in Western diet-fed female mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022, 322, H167–H180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, J.; Ramirez-Perez, F.I.; Habibi, J.; Bostick, B.; Aroor, A.R.; Hayden, M.R.; et al. Regular Exercise Reduces Endothelial Cortical Stiffness in Western Diet-Fed Female Mice. Hypertension 2016, 68, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Sloten, T.T.; Stehouwer, C.D.A. Carotid Stiffness: A Novel Cerebrovascular Disease Risk Factor. Pulse (Basel) 2016, 4, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieman, S.J.; Melenovsky, V.; Kass, D.A. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005, 25, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbaje, A.O. Arterial stiffness precedes hypertension and metabolic risks in youth: a review. Journal of Hypertension. 2022, 49, 1887–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyúl-Tóth, Á.; Patai, R.; Csiszar, A.; Ungvari, A.; Gulej, R.; Mukli, P.; et al. Linking peripheral atherosclerosis to blood–brain barrier disruption: Elucidating its role as a manifestation of cerebral small vessel disease in vascular cognitive impairment. Geroscience. 2024, 46, 6511–6536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.M.; Craft, S.; Lopez, O.L. Review of ‘the potential role of arterial stiffness in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease’. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2015, 5, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.R.; Tyagi, S.C. Intimal redox stress: accelerated atherosclerosis in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atheroscleropathy. 2002, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.R. Brain endothelial cell activation and dysfunction associate with and contribute to the development of enlarged perivascular spaces and cerebral small vessel disease. Histol Histopathol. 2024, 39, 1565–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R. Brain Injury: Response to Injury Wound-Healing Mechanisms and Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023, 59, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R. Paying Homage to Microvessel Remodeling and Small Vessel Disease in Neurodegeneration: Implications for the Development of Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. J Vasc Dis. 2024, 3, 419–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorin-Trescases, N.; de Montgolfier, O.; Pinçon, A.; Raignault, A.; Caland, L.; Labbé, P.; Thorin, E. Impact of pulse pressure on cerebrovascular events leading to age-related cognitive decline. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018, 314, H1214–H1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.F. Arterial Stiffness in Aging: Does It Have a Place in Clinical Practice?: Recent Advances in Hypertension. Hypertension. 2021, 77, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwald, S.E. Ageing of the conduit arteries. J Pathol. 2007, 211, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P. Arterial Stiffness and Hypertension in the Elderly. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020, 7, 544302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.L. Arterial stiffness and hypertension. Clin Hypertens. 2023, 29, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z. Aging, Arterial Stiffness, and Hypertension. Hypertension. 2015, 65, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMahon, S.; Peto, R.; Cutler, J.; Collins, R.; Sorlie, P.; Neaton, J.; et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1: prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990, 335, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiesmann, M.; Kiliaan, A.J.; Claassen, J.A. Vascular aspects of cognitive impairment and dementia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013, 33, 1696–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, P. Current Concepts of the Pathogenesis of the Acute Coronary Syndromes. Circulation 104, 365–372. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poznyak, A.V.; Sadykhov, N.K.; Kartuesov, A.G.; Borisov, E.E.; Melnichenko, A.A.; Grechko AVOrekhov, A.N. Hypertension as a risk factor for atherosclerosis: Cardiovascular risk assessment. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 9, 959285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.R. Overview and New Insights into the Metabolic Syndrome: Risk Factors and Emerging Variables in the Development of Type 2 Diabetes and Cerebrocardiovascular Disease. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023, 59, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demer, L.L.; Tintut, Y. Vascular Calcification: Pathobiology of a Multifaceted Disease. Circulation 2008, 117, 2938–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagita, Y. Distinct pathophysiology of small vessel disease from atherosclerosis. Hypertens Res. 2024, 47, 3073–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langbaum, J.B.; Chen, K.; Launer, L.J.; et al. Blood pressure is associated with higher brain amyloid burden and lower glucose metabolism in healthy late middle-age persons. Neurobiol Aging. 2012, 33, 827–e811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, J.B.; Toledo, E.; Weiner, M.W.; et al. Cardiovascular risk factors, cortisol, and amyloid-beta deposition in Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 2012, 8, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.M.; Kuller, L.H.; Barinas-Mitchell, E.J.M.; et al. Pulse wave velocity is associated with β-amyloid deposition in the brains of very elderly adults. Neurology. 2013, 81, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, T.M.; Kuller, L.H.; Barinas-Mitchell, E.J.M.; et al. Arterial stiffness and beta-amyloid progression in nondemented elderly adults. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrrington, W.; Lacey, B.; Sherliker, P.; Armitage, J.; Lewington, S. Epidemiology of Atherosclerosis and the Potential to Reduce the Global Burden of Atherothrombotic Disease. Circ Res. 2016, 118, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Shi, X.; Xing, Y.; Tang, Y. Association between atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stary, H.C. Composition and classification of human atherosclerotic lesions. Virchows Arch A Pathology Anat Histopathol. 1992, 421, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stary, H.C.; Blankenhorn, D.H.; Chandler, A.B.; Glagov, S.; Insull Jr, W.; Richardson, M.; et al. A definition of the intima of human arteries and of its atherosclerosis-prone regions. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1992, 85, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R.; Habibi, J.; Joginpally, T.; Karuparthi, P.R.; Sowers, J.R. Ultrastructure Study of Transgenic Ren2 Rat Aorta - Part 1: Endothelium and Intima. Cardiorenal Med. 2012, 2, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.R.; Sowers, J.R.; DeMarco, V.G. Ultrastructure study of the transgenic REN2 rat aorta – part 2: media, external elastic lamina, and adventitia. Biomed Reviews. 2019, 30, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R.; Tyagi, S.C. Vasa vasorum in plaque angiogenesis, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and atheroscleropathy: a malignant transformation. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2004, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006, 47, C7–C12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R.; Reidy, M. Many roads lead to atheroma. Nat Med. 1995, 1, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stehouwer, C.D.; Henry, R.M.; Ferreira, I. Arterial stiffness in diabetes and the metabolic syndrome: a pathway to cardiovascular disease. Diabetologia. 2008, 51, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R.; Karuparthi, P.R.; Chaudhury, N.A.; Gorindarajan, G.; Habibi, J.; Ortman, R.A. Autoimmune Vasculitits and Plaque Erosion in the Cardiometabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes mellitus. J Cardiometabolic Syn. 2007, 1, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, K.A.; Chai, S.; Chen, H.; Danielsen, C.C.; Simonsen, U.; Wogensen, L. Mechanisms involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and arterial stiffness induced by hyaluronan accumulation. Atherosclerosis. 2016, 244, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, M. Arterial Calcification and Its Association With Stroke: Implication of Risk, Prognosis, Treatment Response, and Prevention. Front Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 845215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.H.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, L.J.; Wong, K.S. Intracranial Artery Calcification and Its Clinical Significance. J Clin Neurol. 2016, 12, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesauro, M.; Mauriello, A.; Rovella, V.; Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli, M.; Cardillo, C.; Melino, G.; Daniele, N.D. Arterial ageing: from endothelial dysfunction to vascular calcification. J Intern Med. 2017, 281, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Rementer, C.; Giachelli, C.M. Vascular Calcification: an Update on Mechanisms and Challenges in Treatment. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013, 93, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.R.; Tyagi, S.C.; Kolb, L.; Sowers, J.R.; Khanna, R. Vascular ossification-calcification in metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and calciphylaxis-calcific uremic arteriolopathy: the emerging role of sodium thiosulfate. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2005, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowers, K.M.; Hayden, M.R. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy: Pathophysiology, reactive oxygen species and therapeutic approaches. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010, 3, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, A.; Van Hecke, W.; Spliet, W.G.M.; Goldschmeding, R.; Isgum, I.; Kockelkoren, R.; et al. Predominance of Nonatherosclerotic Internal Elastic Lamina Calcification in the Intracranial Internal Carotid Artery. Stroke. 2016, 47, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, A.L.; Speer, M.Y.; Scatena, M.; Giachelli, C.M.; Shanahan, C.M. Role of smooth muscle cells in vascular calcification: implications in atherosclerosis and arterial stiffness. Cardiovasc Res. 2018, 114, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, A.; Leaf, E.M.; Abbadi, M.; Giachelli, C.M. Elastin Degradation and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotype Change Precede Cell Loss and Arterial Medial Calcification in a Uremic Mouse Model of Chronic Kidney Disease. Am J Pathol. 2011, 178, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEniery, C.M.; McDonnell, B.J.; So, A.; Aitken, S.; Bolton, C.E.; Munnery, M.; et al. Aortic calcification is associated with aortic stiffness and isolated systolic hypertension in healthy individuals. Hypertension. 2009, 53, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R. The Brain Endothelial Cell Glycocalyx Plays a Crucial Role in the Development of Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Life (Basel). 2023, 13, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogné, S.; Flamion, B.; Caron, N. Endothelial glycocalyx as a shield against diabetic vascular complications: Involvement of hyaluronan and hyaluronidases. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018, 38, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, W.A. From blood–brain barrier to blood–brain interface: new opportunities for CNS drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, M.A.; Wilson, M.L.; Banks, W.A. In vitro modeling of blood–brain barrier and interface functions in neuroimmune communication. Fluids and Barriers. 2020, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.K. Linking endothelial dysfunction with endothelial cell activation. J Clin Invest. 2013, 123, 540–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, R.C.; Loscalzo, J. Vascular nitric oxide: formation and function. J Blood Med. 2010, 1, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patik, J.C.; Lennon, S.L.; Farquhar, W.B.; Edwards, D.G. Mechanisms of Dietary Sodium-Induced Impairments in Endothelial Function and Potential Countermeasures. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safar, M.E.; Thuilliez, C.; Richard, V.; Benetos, A. Pressure-independent contribution of sodium to large artery structure and function in hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2000, 46, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, A.; Salvi, L.; Coruzzi, P.; Salvi, P.; Parati, G. Sodium Intake and Hypertension. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milionis, H.J.; Florentin, M.; Giannopoulos, S. Metabolic syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease: a link to a vascular hypothesis. CNS Spectr. 2008, 13, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scuteri, A.; Najjar, S.S.; Muller, D.C.; Andres, R.; Hougaku, H.; Metter, J.; Lakatta, E.G. Metabolic syndrome amplifies the age-associated increases in vascular thickness and stiffness. Am Coll Cardiol. 2004, 43, 1388–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillaci, G.; Pirro, M.; Vaudo, G.; Mannarino, M.R.; Savarese, G.; Pucci, G.; Franklin, S.S.; Mannarino, E. Metabolic Syndrome Is Associated With Aortic Stiffness in Untreated Essential Hypertension. Hypertension. 2005, 45, 1078–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro-Silva, J.C.; Nolasco, P.; Krieger, J.E.; Miyakawa, A.A. Dynamic Crosstalk between Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and the Aged Extracellular Matrix. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 10175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnier, V.M.; Mustata, G.T.; Biemel, K.L.; Reihl, O.; Lederer, M.O.; Zhenyu, D.; Sell, D.R. Cross-Linking of the Extracellular Matrix by the Maillard Reaction in Aging and Diabetes: An Update on “a Puzzle Nearing Resolution”. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1043, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.Y.; Chen, A.Q.; Zhang, H.; Gao, X.F.; Kong, X.Q.; Zhang, J.J. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Phenotypic Switching in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells. 2022, 11, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Trzeciakowski, J.P.; Gansner, M.; Depre, C.; et al. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Stiffness as a Mechanism for Increased Aortic Stiffness with Aging. Circ Res. 2010, 107, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiquet, M.; Gelman, L.; Lutz, R.; Maier, S. From mechanotransduction to extracellular matrix gene expression in fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009, 1793, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsuda, S.; Kaji, T. Atherosclerosis and extracellular matrix. Atheroscl thromb. 2003, 10, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.; Tomlinson, L.A.; Ford, M.L.; McMahon, L.P.; Rajkumar, C.; Holt, S.G. Elastin Degradation Is Associated With Progressive Aortic Stiffening and All-Cause Mortality in Predialysis Chronic Kidney Disease. Hypertension. 2012, 59, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocciolone, A.J.; Hawes, J.Z.; Staiculescu, M.C.; Johnson, E.O.; Murshed, M.; Wagenseil, J.E. Elastin, arterial mechanics, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018, 315, H189–H205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duca, L.; Blaise, S.; Romier, B.; Laffargue, M.; Gayral, S.; El Btaouri, G.; et al. Matrix ageing and vascular impacts: focus on elastin fragmentation. Cardiovasc Res. 2016, 110, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.R. Empagliflozin Ameliorates Tinica Adiposa Expansion and Vascular Stiffening of the Descending Aorta in Female db db Mice. Adipobiology 2020, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, S.F.; Zahradka, P. Vascular smooth muscler cell motility: From migration to invasion. Exp Clin Cardiol 2010, 15, e75–e85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ridley, A.J.; Schwartz, M.A.; Burridge, K.; Firtel, R.A.; Ginsberg, M.H.; Borisy, G.; Parsons, J.T.; Horwitz, A.R. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003, 302, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Page, A.; Khalil, A.; Vermette, P.; Frost, E.H.; Larbi, A.; Witkowski, J.M.; Fulop, T. The role of elastin-derived peptides in human physiology and diseases. Matrix Biol. 2019, 84, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahart, A.; Hocine, T.; Albrecht, C.; Henry, A.; Sarazin, T.; Martiny, L.; et al. Role of elastin peptides and elastin receptor complex in metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 2980–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babici, D.; Kudej, R.K.; McNulty, T.; Zhang, J.; Oydanich, M.; Berkman, T.; et al. Mechanisms of increased vascular stiffness down the aortic tree in aging, premenopausal female monkeys. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020, 319, H222–H234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Perez, F.I.; Cabral-Amador, F.J.; Whaley-Connell, A.T.; Aroor, A.R.; Morales-Quinones, M.; Woodford, M.L.; et al. Cystamine reduces vascular stiffness in Western diet-fed female mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022, 322, H167–H180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iadecola, C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2004, 5, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadecola, C . The neurovascular unit coming of age: a journey through neurovascular coupling in health and disease. Neuron 2017, 96, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadecola, C.; Duering, M.; Hachinski, V.; Joutel, A.; Pendlebury, S.T.; Schneider, J.A.; Dichgans, M. Vascular Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019, 73, 3326–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.R. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Increases the Risk of Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease: Ultrastructural Remodeling of the Neurovascular Unit and Diabetic Gliopathy. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabkin, S.W. Arterial stiffness: detection and consequences in cognitive impairment and dementia of the elderly. J Alzheimer’s disease. 2012, 32, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabkin, S.W.; Jarvie, G. Comparison of vascular stiff-ness in vascular dementia, Alzheimer dementia and cognitive impairment. Blood Pressure. 2011, 20, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Rourke, M.F.; Safar, M.E. Relationship between aortic stiffening and microvascular disease in brain and kidney:Cause and logic of therapy. Hypertension. 2005, 46, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kling, M.A.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Wolk, D.A.; Lee, V.M.Y.; Arnold, S.E. Alzheimers Dement. 2012, 9, 76–92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.R. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Increases The Risk of Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease: Ultrastructural Remodeling of the Neurovascular Unit and Diabetic Gliopathy. BrainSci. 2019, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.F.; Liu, P.Y.; Wu, T.J.; Hung, Y.; Yang, S.P.; Lin, G.M. Therapeutic modification of arterial stiffness: An update and comprehensive review. World J Cardiol. 2015, 7, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Effects of first-line antidiabetic drugs on the improvement of arterial stiffness: A Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Diabetes. 2023, 15, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroor, A.R.; Das, N.A.; Carpenter, A.J.; Habibi, J.; Jia, G.; Ramirez-Perez, F.I.; et al. Glycemic control by the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin decreases aortic stiffness, renal resistivity index and kidney injury. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018, 17, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Multiple peripheral-systemic injurious species affect the brain endothelial cells (BECs). Notably, these injurious species also contribute to systemic endothelial cells (SECs) and vascular remodeling to result in vascular arterial stiffening (VAS). These injurious species activate not only SECs but also the BECs of the neurovascular unit (NVU), resulting in BEC activation and dysfunction (BEC

act/dys) and blood–brain barrier dysfunction/disruption (BBB

dd). BEC

act/dys and BBB

dd are biomarkers for the development of cerebral small vessel disease (SVD). Likewise, SVD may serve as biomarkers of BEC

act/dys and BBB

dd). Note the red-dashed line at the top of this image, which designates the EC plasmalemma location of the multiple injurious species that are responsible for initial SEC and BEC injury in multiple clinical diseases and structural remodeling abnormalities including SVD. SEC injurious species result in a SEC fragmentation and attenuation and/or loss of elastin that is replaced with stiffened collagen and accumulation of proteoglycans along with vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy and migratory phenotypes in addition to SEC stiffening contributing to VAS. BEC insulin resistance associated with an increase in glucose and the AGE receptor (RAGE) interaction is also important in the development of BEC

act/dys, BBB

dd, and neurodegeneration (not shown). Also, note that angiotensinII (AngII) denotes the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) including the endothelial cell mineralocorticoid receptor (ECMR) for aldosterone and that both play a role in the development of arterial stiffening. This modified image is provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

3,

4,

5,

6]. AGE, advanced glycation end products; Ang II, angiotensin two; BBB, blood–brain barrier; BEC, brain endothelial cell; BBB

dd, blood–brain barrier dysfunction and disruption; BEC

act/dys, brain endothelial cell activation/dysfunction; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin; CCL2, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; Cox-2, cyclo-oxygenase-2; Cox-2/PGE2 axis, cyclo-oxygenase-2/prostaglandin E2; downward arrows, arrowheads, denote call outs; ecGCx, endothelial glycocalyx; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; JAMs, junctional adhesion molecules; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LPa, lipoprotein little a; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; NO, nitric oxide; Nox2, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NADPH Ox); peroxinitrite (ONOO-); pnsCC, peripheral nervous system cytokines/chemokines; pp, pulsatile-pulse pressure;, NVU, neurovascular unit; RBC, red blood cell; Red arrows, denote increase; RONSS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur species; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RSI, reactive species interactome; T, transcytosis; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; underlining, denotes emphasis; upward arrows, denote increase; VCAM-1, vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1; WBC, white blood cell.

Figure 1.

Multiple peripheral-systemic injurious species affect the brain endothelial cells (BECs). Notably, these injurious species also contribute to systemic endothelial cells (SECs) and vascular remodeling to result in vascular arterial stiffening (VAS). These injurious species activate not only SECs but also the BECs of the neurovascular unit (NVU), resulting in BEC activation and dysfunction (BEC

act/dys) and blood–brain barrier dysfunction/disruption (BBB

dd). BEC

act/dys and BBB

dd are biomarkers for the development of cerebral small vessel disease (SVD). Likewise, SVD may serve as biomarkers of BEC

act/dys and BBB

dd). Note the red-dashed line at the top of this image, which designates the EC plasmalemma location of the multiple injurious species that are responsible for initial SEC and BEC injury in multiple clinical diseases and structural remodeling abnormalities including SVD. SEC injurious species result in a SEC fragmentation and attenuation and/or loss of elastin that is replaced with stiffened collagen and accumulation of proteoglycans along with vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy and migratory phenotypes in addition to SEC stiffening contributing to VAS. BEC insulin resistance associated with an increase in glucose and the AGE receptor (RAGE) interaction is also important in the development of BEC

act/dys, BBB

dd, and neurodegeneration (not shown). Also, note that angiotensinII (AngII) denotes the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) including the endothelial cell mineralocorticoid receptor (ECMR) for aldosterone and that both play a role in the development of arterial stiffening. This modified image is provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

3,

4,

5,

6]. AGE, advanced glycation end products; Ang II, angiotensin two; BBB, blood–brain barrier; BEC, brain endothelial cell; BBB

dd, blood–brain barrier dysfunction and disruption; BEC

act/dys, brain endothelial cell activation/dysfunction; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin; CCL2, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; Cox-2, cyclo-oxygenase-2; Cox-2/PGE2 axis, cyclo-oxygenase-2/prostaglandin E2; downward arrows, arrowheads, denote call outs; ecGCx, endothelial glycocalyx; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; JAMs, junctional adhesion molecules; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LPa, lipoprotein little a; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; NO, nitric oxide; Nox2, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NADPH Ox); peroxinitrite (ONOO-); pnsCC, peripheral nervous system cytokines/chemokines; pp, pulsatile-pulse pressure;, NVU, neurovascular unit; RBC, red blood cell; Red arrows, denote increase; RONSS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur species; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RSI, reactive species interactome; T, transcytosis; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; underlining, denotes emphasis; upward arrows, denote increase; VCAM-1, vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1; WBC, white blood cell.

Figure 2.

Possible four-step sequence of events (S1–S4) implicating extracranial vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) in the development and progression of neurodegeneration and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). Step 1. Aging, Genetics, Hypertension inclusive of essential hypertension (eHTN) and the more predominant isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) in the elderly, and atherosclerosis that is inclusive of vascular ossification calcification (VOC), metabolic syndrome (MetS), insulin resistance (IR), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Step 2. Extracranial vascular arterial stiffening/stiffness (VAS), oxidative redox stress and vascular inflammation, stroke (primarily ischemic and secondarily hemorrhagic), and vascular contributions to impaired cognition and dementia (VCID). Step 3. Small Vessel Disease (SVD) including lacunes, white matter hyperintensities, enlarged perivascular spaces, and cerebral microbleeds. Step 4. Neurodegeneration, atrophy, and LOAD. ECM, extracellular matrix including both collagen and proteoglycans; CCH, chronic cerebral hypoperfusion and hypometabolism; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; SECact/dys, systemic endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell(s).

Figure 2.

Possible four-step sequence of events (S1–S4) implicating extracranial vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) in the development and progression of neurodegeneration and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). Step 1. Aging, Genetics, Hypertension inclusive of essential hypertension (eHTN) and the more predominant isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) in the elderly, and atherosclerosis that is inclusive of vascular ossification calcification (VOC), metabolic syndrome (MetS), insulin resistance (IR), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Step 2. Extracranial vascular arterial stiffening/stiffness (VAS), oxidative redox stress and vascular inflammation, stroke (primarily ischemic and secondarily hemorrhagic), and vascular contributions to impaired cognition and dementia (VCID). Step 3. Small Vessel Disease (SVD) including lacunes, white matter hyperintensities, enlarged perivascular spaces, and cerebral microbleeds. Step 4. Neurodegeneration, atrophy, and LOAD. ECM, extracellular matrix including both collagen and proteoglycans; CCH, chronic cerebral hypoperfusion and hypometabolism; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; SECact/dys, systemic endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell(s).

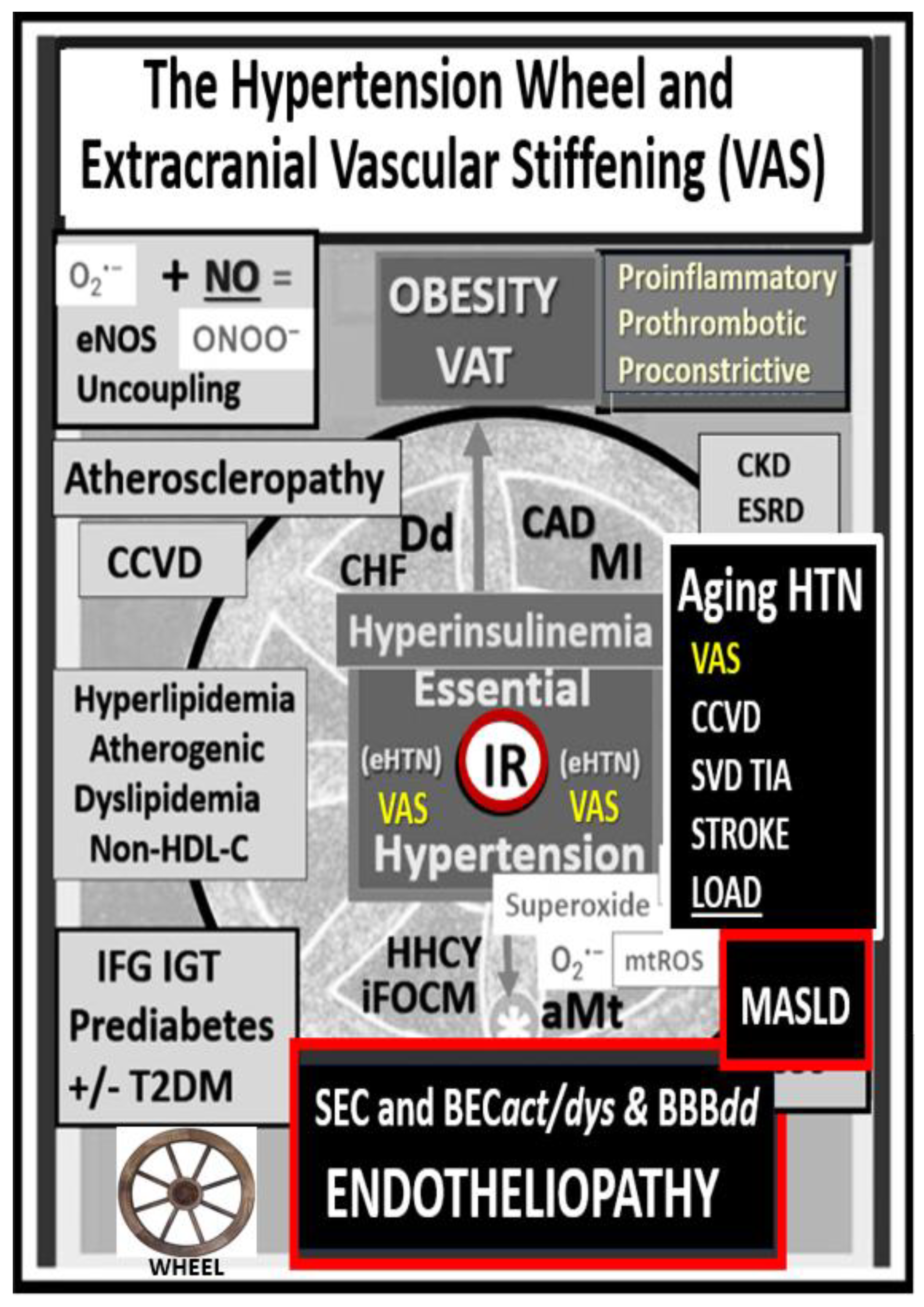

Figure 3.

The essential hypertension (HTN) wheel. This HTN wheel depicts insulin resistance (IR) as a central core feature of the wheel as it is in the MetS. IR is a central mediator for the development of HTN and impaired fasting glucose (IFG)-impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)–type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM), along with multiple metabolic and clinical boxed-in conditions that surround the outer portions of this hypertension wheel. Obesity is placed at the top of the wheel because it is believed to be the driving force behind the subsequent clinical end-organ remodeling and disease in addition to the development of HTN. Systemic and brain endothelial cell activation and dysfunction (SEC and BEC at the bottom of the wheel result in increased peroxynitrite (ONOO

−) and decreased nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability (asterick). Peroxynitrite is generated by the reaction between superoxide and NO. Note the multiple diseases that are associated with HTN, and the wheel depicts the interconnectedness between HTN and the multiple disease states, including vascular stiffening. Thus, obesity, IR, HTN, and T2DM are not to be underestimated. Atheroscleropathy is a term that may be used when discussing accelerated atherosclerosis and macrovascular disease in those individuals with T2DM and the MetS. The wheel was chosen as a background icon (bottom left) because it goes round and round, and over time it just keeps on turning and results in vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) and end-organ damage in the heart-vacular-brain axis that has high capillary flow with low resistance and increased vulnerability to the increased pulsatile pulse pressure and pulse wave velocity associated with vascular stiffening, HTN, and microvascular disease. Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

34]. Asterisk, equals emphasis; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; Dd, diastolic dysfunction

; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; LOAD, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated liver disease; MI, myocardial infarction; mtROS, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species; O

2•–, superoxide; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Figure 3.

The essential hypertension (HTN) wheel. This HTN wheel depicts insulin resistance (IR) as a central core feature of the wheel as it is in the MetS. IR is a central mediator for the development of HTN and impaired fasting glucose (IFG)-impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)–type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM), along with multiple metabolic and clinical boxed-in conditions that surround the outer portions of this hypertension wheel. Obesity is placed at the top of the wheel because it is believed to be the driving force behind the subsequent clinical end-organ remodeling and disease in addition to the development of HTN. Systemic and brain endothelial cell activation and dysfunction (SEC and BEC at the bottom of the wheel result in increased peroxynitrite (ONOO

−) and decreased nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability (asterick). Peroxynitrite is generated by the reaction between superoxide and NO. Note the multiple diseases that are associated with HTN, and the wheel depicts the interconnectedness between HTN and the multiple disease states, including vascular stiffening. Thus, obesity, IR, HTN, and T2DM are not to be underestimated. Atheroscleropathy is a term that may be used when discussing accelerated atherosclerosis and macrovascular disease in those individuals with T2DM and the MetS. The wheel was chosen as a background icon (bottom left) because it goes round and round, and over time it just keeps on turning and results in vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) and end-organ damage in the heart-vacular-brain axis that has high capillary flow with low resistance and increased vulnerability to the increased pulsatile pulse pressure and pulse wave velocity associated with vascular stiffening, HTN, and microvascular disease. Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

34]. Asterisk, equals emphasis; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; Dd, diastolic dysfunction

; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; LOAD, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated liver disease; MI, myocardial infarction; mtROS, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species; O

2•–, superoxide; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

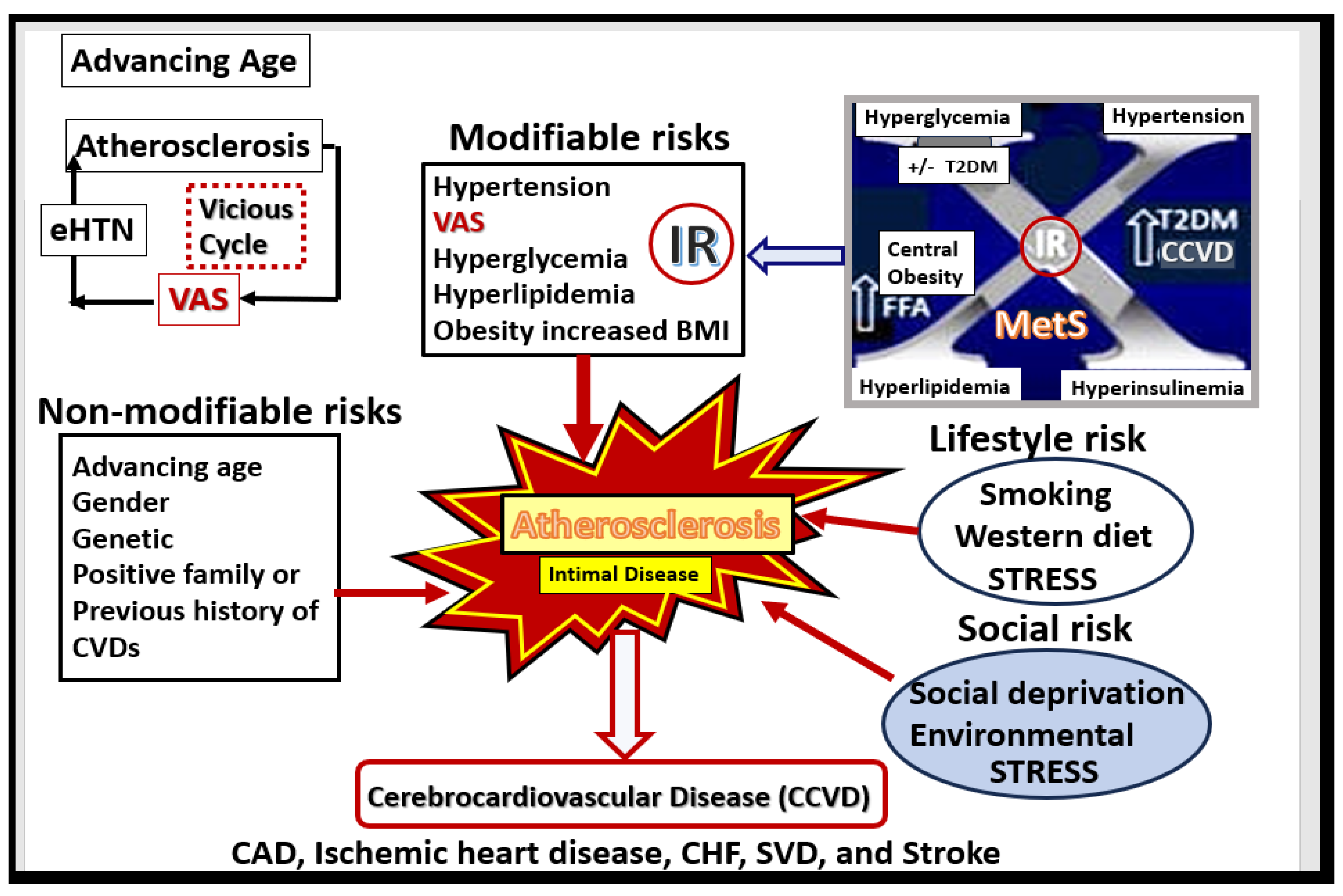

Figure 4.

Multiple risk factors for the development and progression of atherosclerosis. Note the important role of the MetS upper right and also the vicious cycle between atherosclerosis, eHTN and VAS that associates with advancing age. BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVDs, cardiovascular diseases; eHTN, essential hypertension; FFA, free fatty acids; IR, insulin resistance; MetS, metabolic syndrome; SVD, small vessel disease. T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; VAS, extracranial vascular arterial stiffness/stiffening.

Figure 4.

Multiple risk factors for the development and progression of atherosclerosis. Note the important role of the MetS upper right and also the vicious cycle between atherosclerosis, eHTN and VAS that associates with advancing age. BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVDs, cardiovascular diseases; eHTN, essential hypertension; FFA, free fatty acids; IR, insulin resistance; MetS, metabolic syndrome; SVD, small vessel disease. T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; VAS, extracranial vascular arterial stiffness/stiffening.

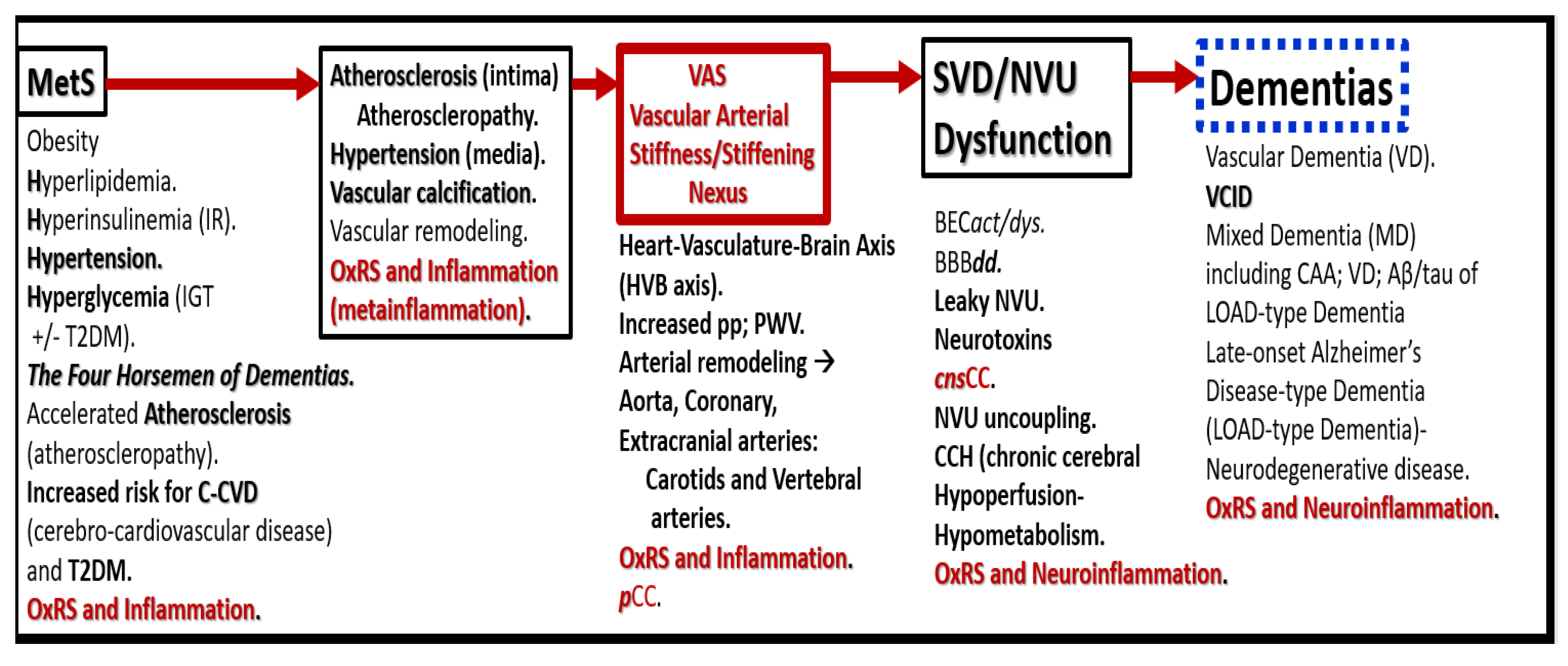

Figure 5.

Possible sequence of events in the development and progression of dementias. Vascular arterial stiffening/stiffness (VAS) may be the Nexus. This figure serves to further expand the information presented in

Figure 2. Aβ, amyloid beta, BEC

act/dys, brain endothelial cell activation/dysfunction; BBB

dd, blood-brain barrier dysfunction and disruption; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy;

cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines/chemokines; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; MetS, metabolic syndrome; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; NVU, neurovascular unit;

pCC, peripheral cytokines/chemokines; pp, pulse pressure; PWV, pulse wave velocity; SVD, small vessel disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; VCID, vascular contributions to impaired cognition and dementia.

Figure 5.

Possible sequence of events in the development and progression of dementias. Vascular arterial stiffening/stiffness (VAS) may be the Nexus. This figure serves to further expand the information presented in

Figure 2. Aβ, amyloid beta, BEC

act/dys, brain endothelial cell activation/dysfunction; BBB

dd, blood-brain barrier dysfunction and disruption; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy;

cnsCC, central nervous system cytokines/chemokines; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; MetS, metabolic syndrome; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; NVU, neurovascular unit;

pCC, peripheral cytokines/chemokines; pp, pulse pressure; PWV, pulse wave velocity; SVD, small vessel disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; VCID, vascular contributions to impaired cognition and dementia.

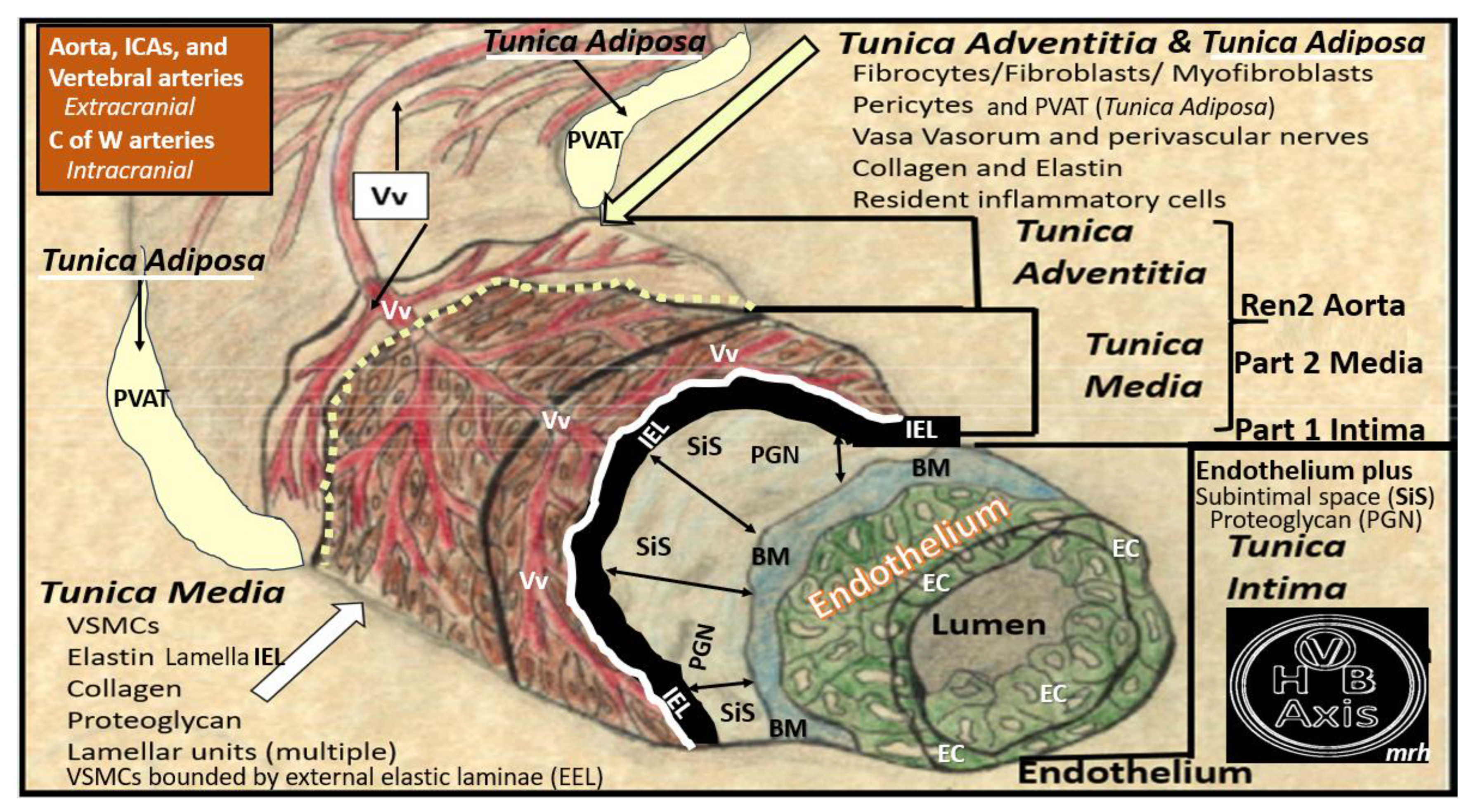

Figure 6.

Pull out model illustrating the three major tunica layers of arteries and how they are structurally interrelated. This illustration demonstrates the lumen that is surrounded by systemic and brain endothelial cells (SECs and BECs) (pseudo-colored green) that have a basement membrane (BM) pseudo-colored blue, and the proteoglycan (PGN)-rich subintimal space (SiS noted by double arrows). These three tunica layers begin most luminally with the tunica intima where atherosclerosis is known to begin. Next the thickend black line forms internal elastic lamina (IEL), which is demarcated by the bold white line, which separates the intima from the tunica media that encircles the artery and serves to allow elastic recoil of the artery once it is stretched along with multiple layers of the elastin lamella that bound the lamellar units containing the vascular smooth muscle cell(s) (VSMCs) pseudo-colored red and denoted by open white arrows that comprise the second tunica that is bound abluminally by the external elastic lamina (yellow dashed line). The most abluminal and third tunica is the tunica adventitia, which is demarcated by the yellow dashed line luminally and the perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) of the tunica adventitia that contains a loose connective tissue with multiple cells including pericytes, mast cells and occasional leukocytes through which, the vasa vasorum (Vv) flows as it penetrates the media to be referred to as the vessel within the vessel. The perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT underlined and pseudo-colored yellow) contains visceral adipocytes and extracellular matrix that is an extension of the tunica adventitia; however, some feel that it merits the distinction to be called the tunica adiposa due to its proinflammatory (metainflammatory) potential to result in aberrant arterial remodeling from the outside in. Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

14,

34]. C of W, circle of Willis; EL, elastin lamina; HVB, heart-vessel-brain axis; ICAs, internal carotid arteries; PGN, proteoglycan; Ren2 rat part I and II, ultrastructure study of the young male transgenic heterozygous (mRen2)27 (Ren2) rat hypertensive model: Aorta intima Part I and media-adventitia Part II with elevated renin, angiotensin II, angiotensin type-1 (AT-1) receptors, and aldosterone; Vv, vasa vasorum.

Figure 6.