1. Introduction

In 2020, according to GLOBOCAN, colorectal cancer (CRC) was estimated to account for 10% of global cancer incidence and 9.4% of cancer deaths, second only to lung cancer, which was estimated to account for 18% of deaths [

1,

2,

3]. Based on projections of an ageing population, population growth and human development, the global number of new colorectal cancer cases is projected to reach 3.2 million in 2040 [

4,

5]. In the UK, over 30,000 new cases of colorectal cancers are diagnosed annually [

6].

Despite the technical improvements made in recent years, there are still a large number of patients presenting very late to the hospital with complicated tumors, sometimes requiring only palliative interventions. The rate of emergency presentations varies between 8% and 34%, most of which are caused by obstructive and perforated tumors [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]

Complicated right colon cancer represents a pathology with a significant morbidity and mortality rate, especially in emergency surgery. "

Emergency colorectal cancer surgery is recognized to be associated with high morbidity and mortality rates" [

14]. This condition, which may be associated with various complications such as obstruction, perforation or massive bleeding, requires careful evaluation of the factors influencing the postoperative course of patients. Studies have shown that "

despite advances in surgical techniques and perioperative management, postoperative death rates remain high, particularly among patients with multiple comorbidities or advanced disease" [

9,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Compared with patients receiving elective surgery, those requiring emergency surgery face higher morbidity and mortality rates. These poorer outcomes are thought to be caused not only by the nature of the emergency, but also due to the fact that patients presenting as emergent often have greater physiologic imbalances, dehydration, electrolyte disturbances, poor nutritional status, and neglected comorbidities [

19,

20,

21,

22]

Colon obstruction complicates between 10 and 19% of colon cancer cases. It is a risk factor for a poor prognosis: immediate postoperative mortality ranges from 15 to 30%, compared with 1 to 5% for elective surgery, and the morbidity rate is twice as high as for elective surgery [

23,

24,

25,

26].

Early detection leads to 5-year survival rates of up to 97.4% for early-stage cancer [

27].

On the other hand, late detection with extensive metastatic disease may reduce this survival rate to 8.1% at 5 years [

28]. Studies show that at the time of diagnosis 20% of patients are in the metastatic phase, the podium being occupied by the liver, followed by the lung [

29,

30,

31,

32].

The prognosis of patients with complicated rectal colon cancer depends on a multitude of factors that influence the final outcome. Among these, "

the patient’s age, the presence of other chronic conditions (such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus or chronic renal failure" [

33], nutritional status before surgery and the complexity of the complication are key determinants.

Timing of diagnosis also plays an important role and "delays in identifying complications increase the risk of mortality" [

34].

The patient’s functional status before surgery is another critical element. "

Preoperative assessments, such as asa (American Society of Anesthesiologists)

scores,

are essential to predict the risks of surgery" [

33]. In addition, "

advanced tumors, the presence of metastases, and lymph node infiltration" are biological elements that worsen prognosis and increase the risk of death [

33].

The surgical techniques used and the experience of the surgical team influence both immediate and long-term outcomes. "Surgery performed in specialized centers by multidisciplinary teams can improve patient prognosis by reducing intraoperative and postoperative complications" [

34,

35]. These prognostic factors should be taken into account in surgical planning and postoperative management to optimize patient survival and quality of life.

2. Material and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed a group of 95 patients admitted in emergency in the County Emergency Hospital St. Apostol Apostol Andrei Galati with complicated tumors of the right colon - occlusive, perforated or hemorrhagic. A series of clinical and biological parameters were followed in order to identify prognostic factors in the occurrence of death.

Statistical analysis was performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics software package (version 23.0). The significance threshold considered for statistical hypotheses was α = 0.05.

We used the Pearson Chi-Square test and likelihood ratio to see if there was a connection between the fact of death and variables such as gender, background, symptoms, laboratory tests, case mix, case mix, intra- and postoperative complications, septic status, invasion of neighboring organs and metastases.

In order to check whether there is a correlation between the numerical variables, we calculated the Spearman coefficient and the associated probability.

Two independent samples t-test was performed in order to investigate whether there were statistically significant differences in the means of Davies score, Charlson score, Charlson score, Charlson or number of days of hospitalization between the group of deceased and the group of other patients.

Kaplan-Meier (KM) is a non-parametric method used to estimate the probability of survival over certain points in time. The main variable is the time measured from the patient’s entry into the study until the critical event occurs (which is death). In addition, the survival distributions of two or more groups, defined in terms of a particular factor, can be compared. The Area under Curve (AUC) or Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) is used to evaluate the performance of a binary classification model, i.e. it checks how well the model is able to distinguish between events and non-events (in our case death). An AUC value of 0.6-0.69 is considered poor, a value of 0.7-0.79 is considered adequate, and an AUC score of 0.8-0.89 is strong and excellent for 0.9-1.0.

3. Result

The study analyzes data obtained from a group of patients aged between 42 and 87 years (mean age = 67.6 years, st. dev. = 10.9218). The group is composed of 45.3% women, 54.7% men, urban (72.6%) and rural (27.4%). Symptoms include: abdominal pain (94.7%), absence of bowel movements (48.4%), nausea (89.5%), vomiting (64.2%), weight loss (16.8%). As for laboratory tests, we observe pathological values of leukocytes (49.5%), anemia (77.9%), pathological values of platelets (14.7%), pathological values of blood glucose (27.4%), pathologic creatinine values (40%), electrolyte disturbances (36.8%), acidosis (21.1%), pathologic protein values (18.9%), pathologic albumin values (14.7%), coagulation disorders (13.7%). Casexia was present in 15.8% of patients. We encountered OI complications (4.2%), septic state (6.3%), invasion of neighboring organs (15.8%), metastasis (24.2%), PO complications (27.4%). Postoperative mortality was 12.63% (12/95).

Table 1 shows patients’ demographics, comorbidities and laboratory information, and statistical correlation with postoperative mortality.

The Pearson Chi-Square test was used to determine the degree of association between two categorical variables. Postoperative mortality may be associated with: sex (χ 2 = 7.561, p = 0.006), weight loss (χ 2 = 16.883, p < 0.001), type of general condition (χ 2= 24.459, p< 0.001), casexia

(χ 2 = 26.739, p < 0.001), leukocytes (χ 2 = 6.299, p = 0.012), anemia (χ 2 = 3.898, p = 0.048),

platelets (χ 2 = 20.776, p , p < 0.001), glycemia (χ 2 = 6.625, p , p = 0.010), creatinine (χ 2 = 4.070,

p = 0.044), electrolyte disturbances (χ 2 = 8.595, p = 0.003), total protein (χ 2 = 4.242, p = 0.039), septic status (χ 2 = 16.944, p , p < 0.001), PO complications (χ 2 = 36.450, p < 0.001).

We were unable to establish a relationship between postoperative death and the groups of age (p = 0.789), environment of origin (p = 0.844), MI. - abdominal pain (p = 0.058), MI. - absence of transit (p = 0.907), MI. - nausea (p = 0.458), MI. - vomiting (p = 0.272), HDI (p = 0.759), app non neo 1/0 (p = 0.160), app neopl 1/0 (p = 0.273), onset (p = 0.277), acidosis (p = 0.061), albumin (p = 0.186), coagulation disorder (p = 0.222), localization code (p = 0.738), DG PREOP (p = 0.227), COMPL IO (p = 0.447), INT-INTERV (p = 0.659), scar abdomen (p = 0.162), type of surgery (p = 0.353), asoc manouvres (p = 0.112), invasion of neighboring organs (p = 0.0449), metastases (p = 0.430), preg colon (p = 0.058), Reinterv (p = 0.503), Scheme type (p = 0.110), days hospitalization (p = 0.165).

Table 2.

| Descriptive Statistics |

|---|

| |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Variance |

| Age |

42.0 |

87.0 |

67.600 |

10.9218 |

119.285 |

| Duration of surgical intervention (hours) |

1.0 |

4.0 |

2.205 |

0.5812 |

0.338 |

| Davies score |

1.0 |

4.0 |

1.811 |

0.7621 |

0.581 |

| Charlson score |

2.0 |

11.0 |

4.453 |

2.8649 |

8.208 |

| Charlson adjusted score |

6.0 |

18.0 |

10.811 |

3.2000 |

10.240 |

| Number of hospitalization days |

1.0 |

48.0 |

16.084 |

7.0328 |

49.461 |

For the numerical values we performed the Spearman correlation test and observed that there are correlations, between age and number of days of hospitalization (ρ = 0.216, p = 0.035), age and Davies score (ρ = 0.294, p = 0.004), age and Charlson score (ρ = 0.205, p = 0.047), age and adjusted Charlson score (ρ = 0.509, p < 0.001), duration of surgery and number of days of hospitalization (ρ = 0.223, p = 0.023), number of days of hospitalization and postoperative day of death (ρ = 0.755, p = 0.003), Davies score and Charlson score (ρ = 0.654, p < 0.001), Davies score and adjusted Charlson score (ρ = 0.550, p < 0.001), Charlson score and adjusted Charlson score (ρ = 0.908, p < 0.001)

Table 3 presents an analysis of the mean values of Davis score, Charlson score, adjusted Charlson score, and number of days of hospitalization for the group of deceased patients compared to the group of other patients.

The t-test for two independent samples shows that there are no statistically significant differences between the mean values of the groups defined by patients who did or did not die postoperatively for the Davies score (t = -1.751, p = 0.083, CI = -0.8699− 0.0547), for the Charlson score (t = -1.695, p = 0.093, CI = -3.2247− 0.2549), for the adjusted Charlson score (t = -1.384, p = 0.170, CI = -3.3145− 0.5916) and for the number of days of hospitalization (t = 1.504, p = 0.363, CI = -0.091− 0.510). We note, however, that the mean values of the scores are higher for deceased patients and the mean number of days of hospitalization is lower for these patients.

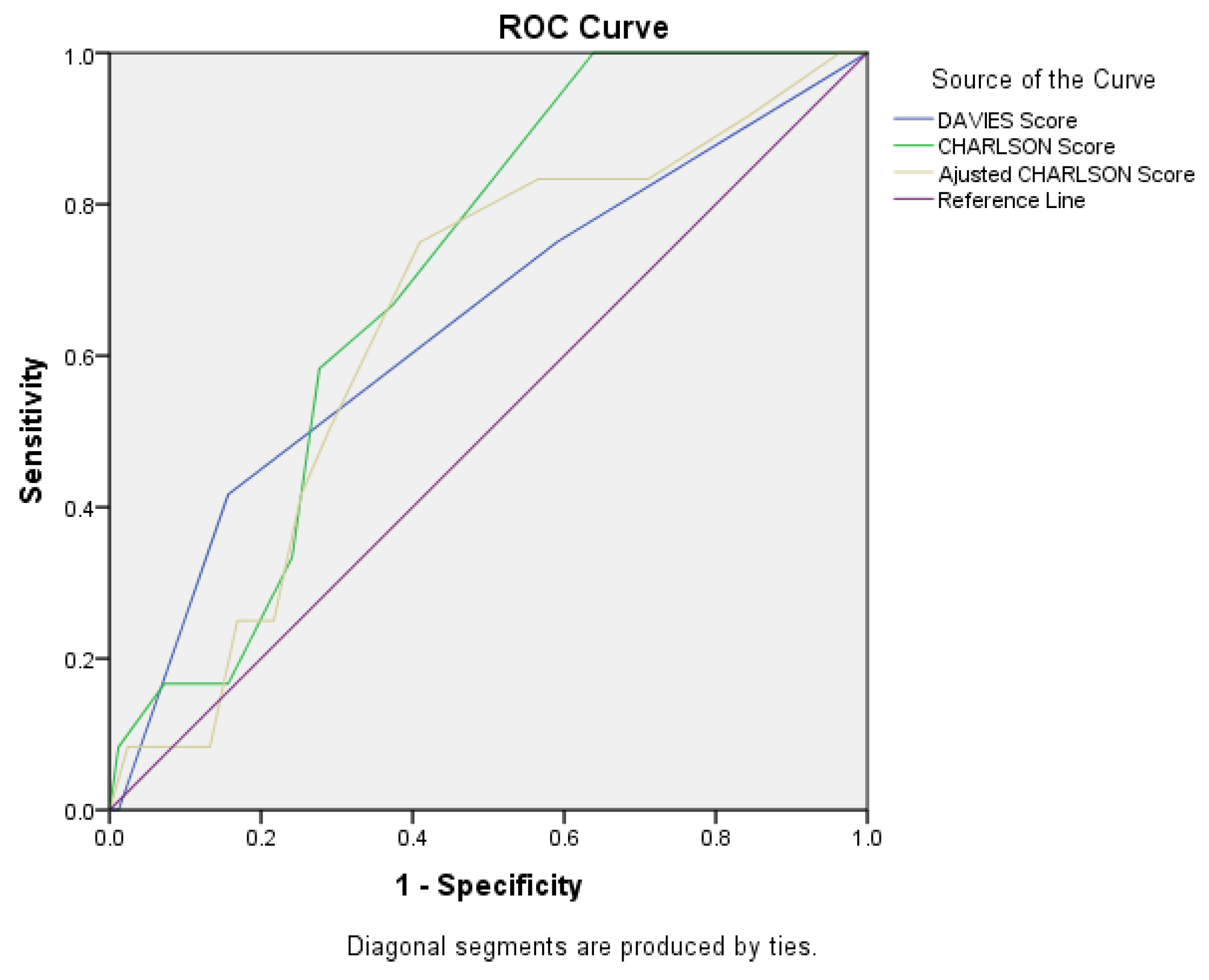

Figure 1.

ROC Curve for Davies score, Charlson score, and adjusted Charlson score.

Figure 1.

ROC Curve for Davies score, Charlson score, and adjusted Charlson score.

The AUC value for the Charlson score was 0.702 (95%CI = 0.579 - 0.826, p = 0.024), which indicates the Charlson score as an adequate predictor of postoperative mortality. For the Davies score, we obtained AUC = 0.642 (95%CI = 0.464 - 0.819, p = 0.114), and for the Charlson score we calculated AUC = 0.644 (95%CI = 0.487 - 0.801, p = 0.108).

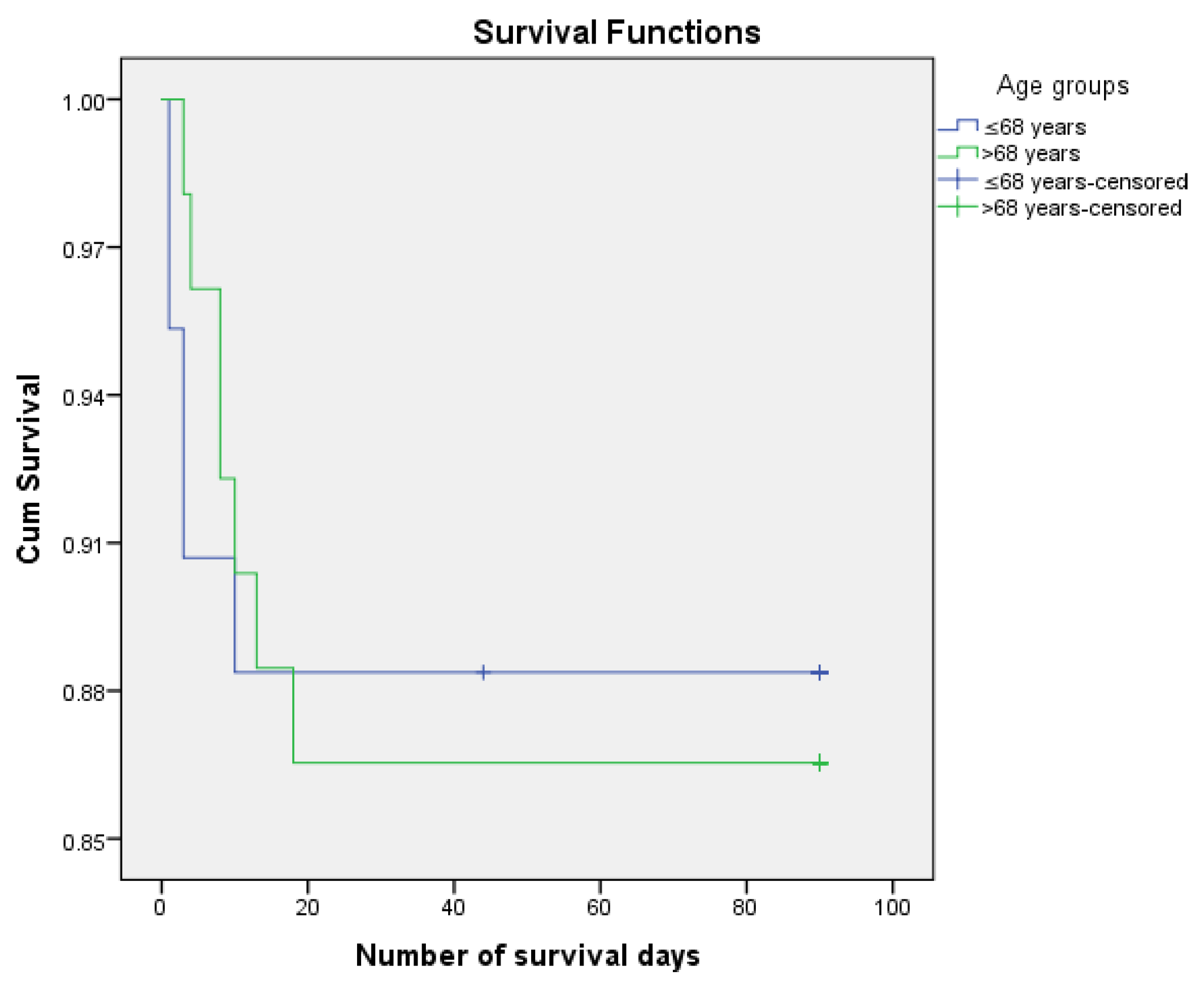

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier survirval curves according to age.

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier survirval curves according to age.

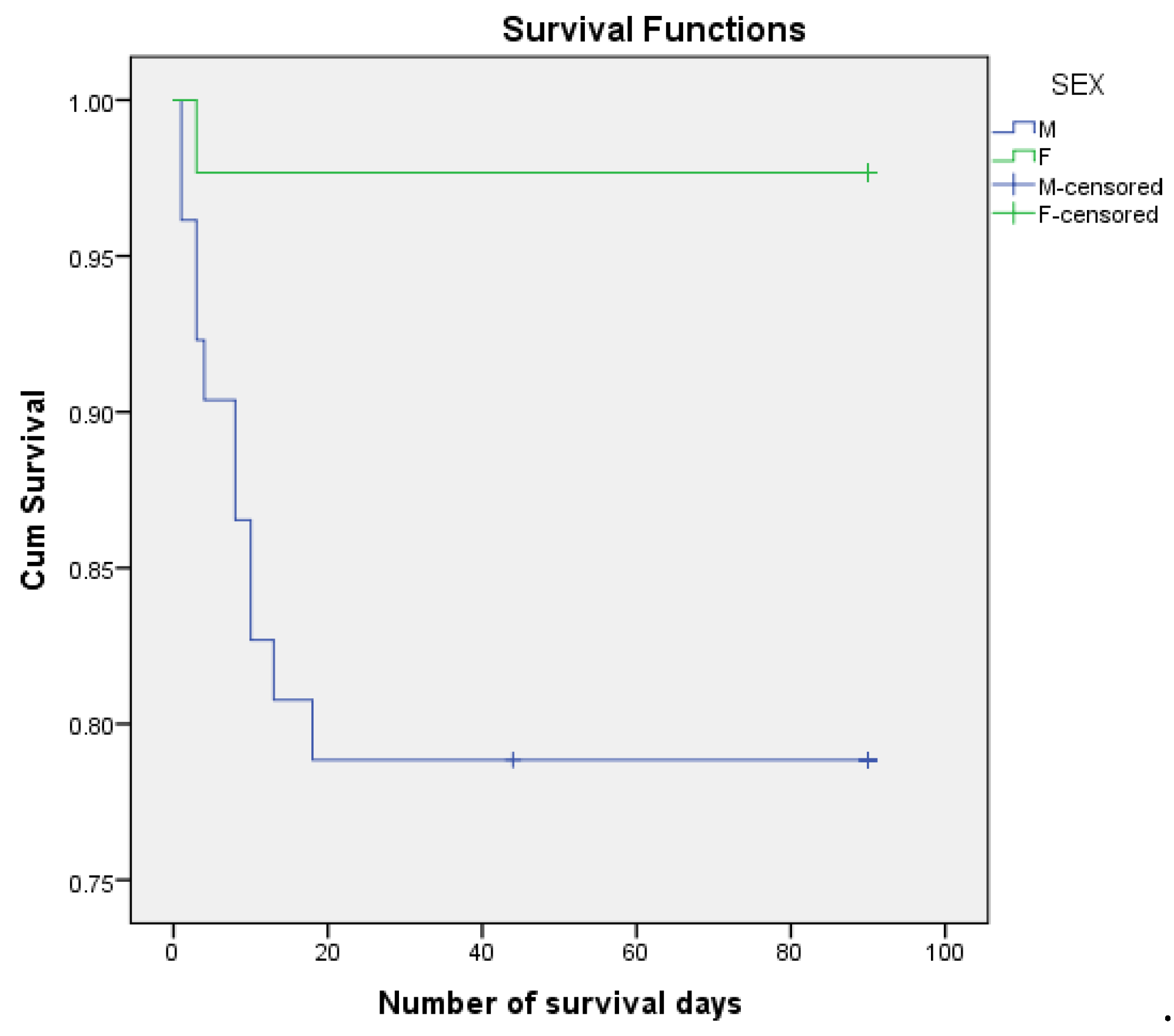

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier survirval curves according to sex.

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier survirval curves according to sex.

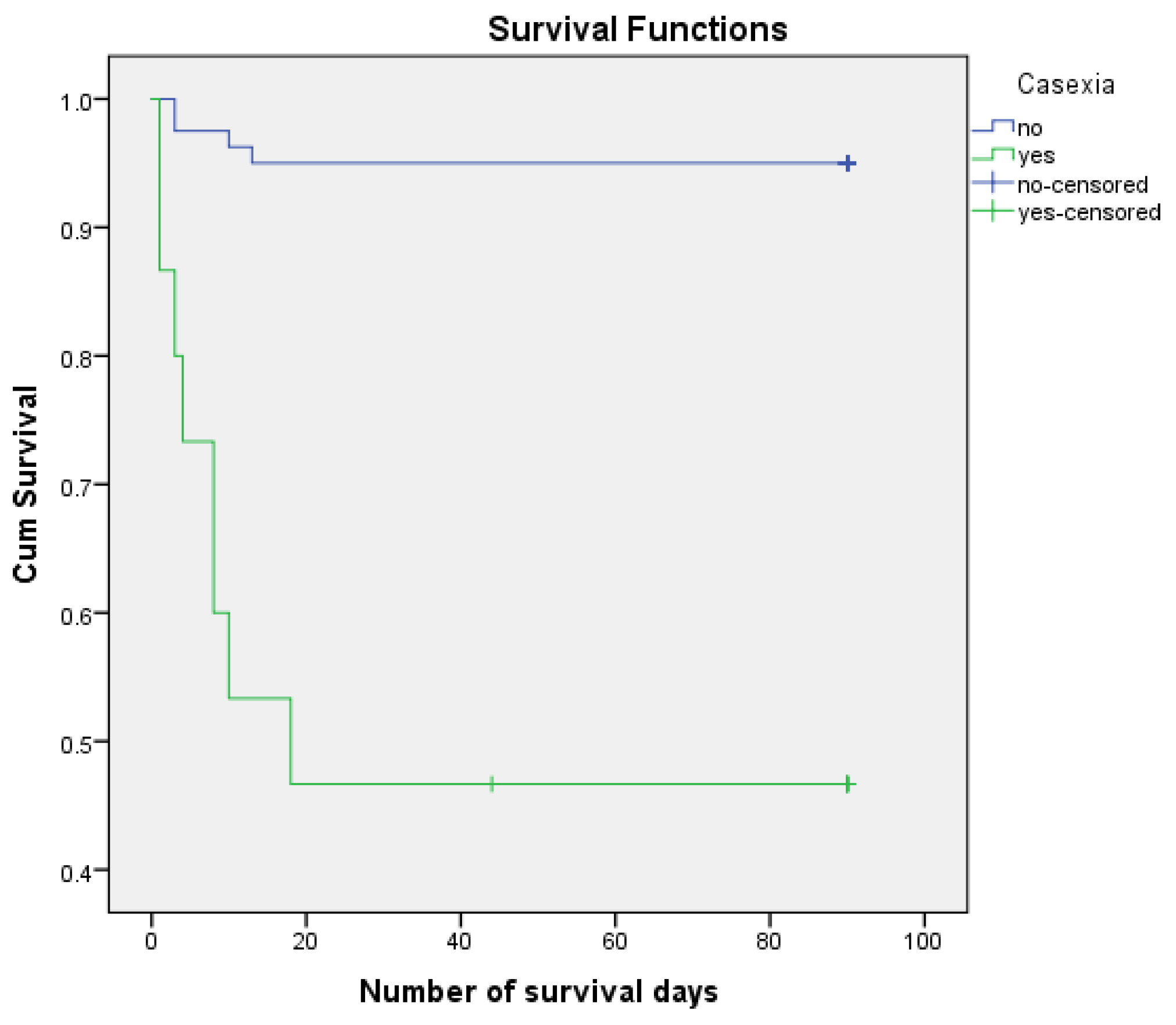

Figure 4.

Survirval curves Kaplan Meier according to casexia.

Figure 4.

Survirval curves Kaplan Meier according to casexia.

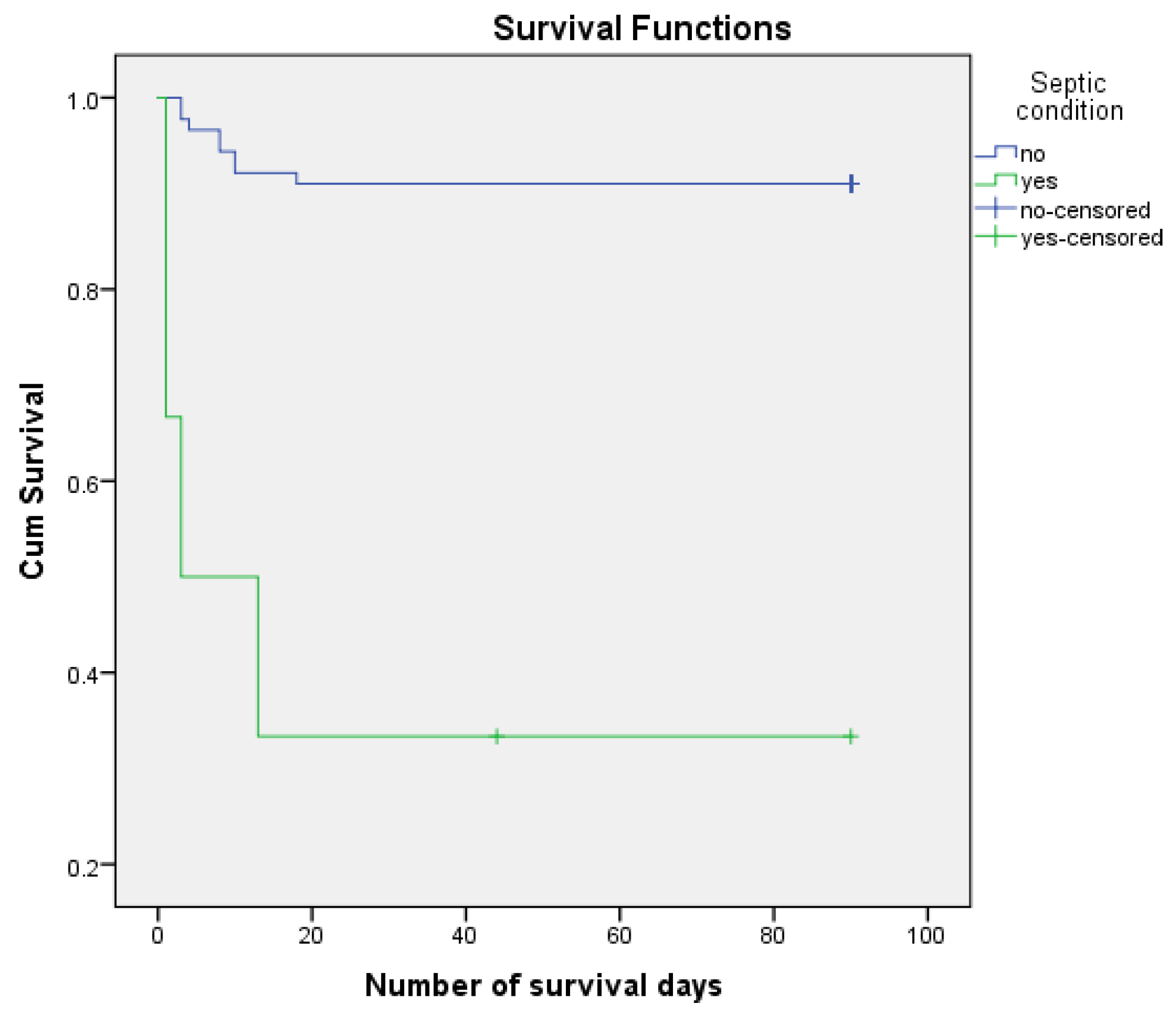

Figure 4.

Survirval Kaplan Meier curves according to septic condition.

Figure 4.

Survirval Kaplan Meier curves according to septic condition.

We analyzed the risk of postoperative death knowing that 12.6% of patients died postoperatively and 87.4% managed to survive the first 3 months (90 days) after surgery. We performed the survival analysis using the Kaplan-Meier method and the Log Rank (Mantel-Cox) statistical method considering the number of days of postoperative survival as a time variable. We also estimated mean survival duration. The results obtained were confirmed using Cox Regression (HR) The results are presented in

Table 4.

4. Discuss

In the study it was observed that the average age of patients with complicated right colon cancer is 67 years, they are mainly urban males, who presented in the emergency room most frequently for abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and absence of bowel transit.

Amri et al. show in a 2015 study show that patients diagnosed and treated as an emergency department for colon cancer present with distinct symptoms from those treated electively. Notably, they present to the emergency room with higher rates of abdominal pain or bloating (56.9% vs. 24.5%) and constipation (13.7% vs. 5.3%). Furthermore, patients who arrive at the emergency room frequently present with severe symptoms, including bowel obstruction (30.4% vs. 2.7%), perforation (15.7% vs. 0.8%), and bleeding (15.7% vs. 1.4%) [

36]

Another study conducted in 2021 on a group of 449 patients with complicated colon cancer highlights that the gender distribution of patients shows a predominance of males, with an M/F ratio of 274/175; urban patients being more numerous, with a U/R ratio of 292/157, data comparable to those obtained by us. The distribution by age groups reveals that the most affected decades are the 8th and 9th (24% and 36.3%, respectively), and the mean age was 68 years [

34,

37].

In terms of symptoms, the aforementioned study showed that abdominal pain was present in 96.65% of patients analyzed. Nausea was recorded in 88.41% of patients and absence of bowel transit in 73.71%. In smaller percentages: vomiting - 46.77%, weight loss - 22.71% and only 3.34% of the cases presented hematochezia.

All patients who underwent stoma or internal shunts had abdominal pain on admission, those with no bowel transit were associated with stoma with or without tumor resection, and those with vomiting had internal shunts. In those with hematochezia, resections with anastomosis were performed. The majority of patients (83.74%) had bowel obstruction; 12.69% had tumor site or diastatic perforations and 3.56% had hemorrhagic tumors. In patients diagnosed with lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage, resections with anastomosis were performed, those with obstruction were statistically associated with internal bypass, and those with digestive perforations underwent stoma resection.

A small percentage of patients present within the first 24 hours of symptom onset, in our study the percentage was 8.43%; similar studies show that 6.45% of patients presented to emergency departments in less than 24 hours. The aforementioned study also analyzed the correlation between late presentation and surgical intervention, finding that patients with symptoms onset within 2-5 days were statistically associated with internal shunts, those with onset between 6-14 days had stoma with or without tumor resection, and those with onset more than 14 days later had resection with anastomosis.

General condition on admission was graded progressively from good to severe according to ECOG status. We found that 21.69% of patients were categorized as ECOG 0, 36.14% ECOG 1 and 32.53% ECOG 2. Another study shows similar results, only 18.49% patients had a good general status (ECOG 0), the others showed various changes: up to had a severe general status (ECOG 4) - 7.35% of patients . This had an influence on the type of surgery practiced, thus in patients with good or satisfactory general condition, resections with anastomosis were performed, in those with impaired general condition (ECOG2) resections with stoma or internal bypass were performed, and in ECOG3 patients stomas were performed.

We identified 8.43% of patients with casexia (estimated by BMI <18.5). In other studies the percentage was higher - 21.82%, which was statistically associated with ostomies.

In our study the patients had changes in biological parameters, changes found in other studies in which laboratory tests showed changes in leukocytes, 65.29% patients had anemia on admission, 14.7% had thrombocytosis/thrombocytopenia, 22.27% had changes in blood glucose on admission, 39.42% had increases in creatinine, 30.06% had electrolyte disturbances, 21.82% had metabolic acidosis. 11.80% of patients had coagulation disorders; 9.13% had a septic state on admission [

34].

We did not observe the statistical significance for survival of the following factors: age groups (p = 0.845), background (p = 0.835), MI. - abdominal pain (p = 0.845), MI. (p = 0.071), MI. - absent transit (p = 0.897), MI. - nausea (p = 0.487), MI. - vomiting (p = 0.317), HDI (p = 0.769), app non neo 1/0 (p = 0.152), app neopl 1/0 (p = 0.267), onset (p = 0.459) anemia (p = 0.054), albumin (p = 203), coagulation disorders (p = 0.196), localization code (p = 0.728), DG PREOP (p = 0.109), COMPL IO (p = 0.497), INT-INTERV (p = 0.708), scar abdomen (p = 0.157), type of surgery (p = 0.240), asoc manvre (p = 0.077), invasion of neighboring organs (p = 0.465), metastases (p = 0.393), preg colon (p = 0.053), reinterv (p = 0.517), type of scheme (p = 0.602), days of hospitalization (p = 0.147).

Of the female patients 2.33% died postoperatively, compared to male patients of whom 21.15% died. The mean estimated number of days of survival was 72,481 days for males and 87,977 days for females. The mortality risk associated with sex was - HR = 0.102, 95% CI(0.013, 0.787) (p = 0.029).

We observed an increased risk of postoperative death associated with weight loss - HR = 8.941, 95% CI (2.824, 28.303) (p < 0.001). 6.32% of patients without weight loss and 43.75% of patients with weight loss died. The mean estimated postoperative survival was 84.899 days for non-weight-loss patients and 52.813 days for weight-loss patients.

Casexia may be associated with the risk of postoperative death - HR = 14.179, 95% CI 4.246, 47.346) ) (p < 0.001). 53.33% of patients with casexia died postoperatively and only 5.0% of patients without casexia died postoperatively. The estimated number of days of survival in patients with casexia was 45,533 and in those without casexia was 85,863.

The postoperative death rate was 26.92% in patients with glycemia and 7.25% in other patients. The median number of estimated survival days was 67,538 in patients with glycemia and 84,000 in others. The mortality risk associated with glycemia was - HR = 0.243, 95% CI (0.077, 0.766) (p = 0.016).

The percentage of postoperative death was 21.05% in patients with creatinine and 7.02% in other patients. The median number of days of estimated survival was 72,395 in creatinine patients and 84,228 in others. The mortality risk associated with creatinine was - HR = 0.312, 95% CI (0.094, 1.037) (p = 0.047).

The risk of mortality associated with electrolyte disturbances was - HR = 5.711, 95% CI (1.545, 21.105) (p = 0.009). The median number of estimated survival days was 68,600 for those with electrolyte disturbances and 85,850 for the remaining patients. Percentagewise, 27.71% of patients with electrolyte disturbances and 5.00% of the remaining patients died.

We determined a risk of postoperative death associated with acidosis - HR = 2.972, 95% CI (0.942, 9.371) (p = 0.048). The median number of days of survival estimated for patients with acidosis was 68,750 and 82,360 for the remaining patients. Postoperatively, 25.00% of patients with acidosis and 9.33% of the remaining patients died.

The risk of postoperative death associated with sepsis is HR = 12.186, 95% CI (3.631, 40.895) (p < 0.001). The median number of days of survival for patients with septic status was estimated at 33.000 and 82.629 for the remaining patients. Postoperatively, 66.67% of patients with acidosis and 8.98% of the remaining patients died. It should be noted that septic state was present in only 6.32% of the analyzed sample.

Tumors located on the right side of the colon are reported to be more advanced at diagnosis. In a smaller study, tumor location was not associated with significant differences in survival.

However, in a large prospective cohort study in the USA of nearly 78,000 patients operated on for colon cancer, postoperative mortality was found to be higher in patients with right colon tumors than in those with left colon tumors (4.0% vs. 5.3%). Also, median age was higher for patients with right colon tumors (73 vs. 69 years), the proportion of poorly differentiated tumors was higher (25% vs. 14%), and median survival was lower (78 months vs. 89 months). Adjusted multivariate analysis showed that the risk of death within five years was higher for right colon tumors. These data emphasize the need for a differentiated approach in the management of right versus left colon cancer, given the unique characteristics and different impact on patient survival [

38].

Another recent study conducted in Romania in 2022 identifies the following causes of death in patients with complicated colon cancer: septic shock, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, anastomotic fistula, acute respiratory failure, acute renal failure and bowel obstruction. Nine independent predictors of 30-day postoperative mortality were identified in a multivariate logistic analysis model:

Age > 70 years,

Congestive heart failure, ECOG > 2 (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Oncology Group performance status),

Sepsis, Obesity, Cachexia, Abnormal platelet values, Abnormal creatinine values, Proximal tumors [40].

The association of comorbidities with the occurrence of postoperative complications in patients with colon cancer is also supported by literature data. Among pre-existing conditions, liver cirrhosis and chronic liver disease, obesity, diabetes, history of operated digestive cancer or other major abdominal surgery, pulmonary disease and pre-existing renal failure are factors that increase morbidity [

14,

40,

41,

42,

43]

Another study mentions congestive heart failure and chronic renal failure as being associated with higher death rates in emergency colorectal surgery [

44,

45].

Nilsen et al. show in a study published in 2021 and conducted on a large number of patients that among patients with colorectal cancer, older age, advanced disease stage, and a higher level of comorbidities were significantly associated with increased odds of being diagnosed in an emergency presentation. Patients with locally advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer were 2- fold and 5-fold more likely, respectively, to be diagnosed after an emergency presentation compared with patients with localized disease, and patients with colon cancer were 2.7-fold more likely to be diagnosed on an emergency presentation compared with patients with rectal cancer. One-year overall survival for patients who had an emergency presentation prior to colorectal cancer diagnosis was 67.7%, whereas for patients without an emergency presentation it was 90.2% [

46]

In our study, although the age-adjusted Davies, Charlson and Charlson comorbidity scores had higher values in patients who died, we could not assess statistical significance. Despite our findings, other studies have shown that a significant number of comorbidities is one of the most important predictors of postoperative complications and early mortality [

47].

Another study analyzing prognostic factors in complicated colorectal cancer mentions associated cardiac pathology (especially fibrillation) as one of the most important risk factors [

48,

49,

50].

Analyzing the risks of death and survival of patients with complicated colorectal cancer, Constantin et al. show that inflammation-based prognostic scores such as NLR (neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio), PLR (platelet/lymphocyte ratio), LMR (lymphocyte/monocyte ratio) and PNI (prognostic nutritional index), SIR scores, were associated with survival of colorectal tumor patients. In univariate analysis, high values of NLR and PLR were found to be risk factors and high values of LMR and PNI were found to be protective factors for survival of colorectal tumor patients undergoing emergency surgery. Increased PLR value is an independent risk factor for patients in the group, while increased values of LMR and PNI are independent protective factors for survival [

51].

On a 2023 study of 391 patients with complicated colorectal cancer, Constantin et al. show that the NLR inflammation-based prognostic score, an outcome of systemic inflammatory response, was associated with patient survival. In univariate analysis, we found that elevated NLR values are risk factors for survival in colorectal cancer patients undergoing emergency surgery [

52]

Although no statistically significant correlation between the presence of metastases and the occurrence of postoperative death was obtained in our study group, Honghua Peng et al. find that liver metastases are a poor prognostic factor for survival [

53]

Studying the problem of survival in patients with advanced colon cancer, Taeyeong Eom et al. show through their study the contribution to the understanding of prognostic factors in T4 colon cancer, emphasizing that en bloc resection, surgical technique and adjuvant chemotherapy play a significant role in improving prognosis. Although no significant differences in outcome were observed between T4a and T4b in curative surgery, the type of surgery (laparoscopic vs. open) and the use of adjuvant chemotherapy were important factors in long-term survival [

54]

5. Conclusions

The postoperative death rate in patients with complicated right colon cancer is high. Most complications were occlusive, followed by hemorrhagic and perforative complications. Less than 10% of patients presented within the first 24 hours of symptom onset. The most relevant prognostic factors in the occurrence of death were weight loss, casexia, renal failure, electrolyte disturbances and metabolic acidosis.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin.2018;68(6):394-424. [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Feb 4. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33538338. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int J Cancer. 2021 Apr 5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33588. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33818764. [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Xu, P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101174. [CrossRef] [PubMed]. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Diskshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methotds and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136(5),E359-386. [CrossRef]

- Cancer Research UK. CancerStats Monograph 2004. London: Cancer Research UK, 2004.

- Jestin, P.; Nilsson, J.; Heurgren, M.; Pahlman, L.; Glimelius, B.; Gunnarsson, U. Emergency surgery for colonic cancer in a defined population. Br. J. Surg. 2005, 92, 94- 100 [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Nascimbeni, R.; Ngassa, H.; Di Fabio, F.; Valloncini, E.; Di Betta, E.; Salerni, B. Emergency surgery for complicated colorectal cancer. A two-decade trend analysis. Dig. Surg. 2008, 25, 133-139. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Barnett A, Cedar A, Siddiqui F, et al. Colorectal cancer emergencies. J Gastrointest Cancer 2013;44(2):132-42.

- Gunnarsson H, Holm T, Ekholm A, et al. Emergency presentation of colon cancer is most frequent during summer. Colorectal Dis 2011;13(6):663-8 Barrett J, Jiwa M, Rose P, Hamilton W. Pathways to the diagnosis of colorectal cancer: an observational study in three UK cities. Fam. Pract. 2005; Advance Access published on November 14, 2005; doi:10.1093/fampra/cmi093. [CrossRef]

- Mella J, Biffin A, Radcliffe AG, Stamatakis JD, Steele RJ. Population-based audit of colorectal cancer management in two UK health regions. Colorectal cancer working group, royal college of surgeons of England clinical epidemiology and audit unit. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 1731-1736.

- Trickett JP, Donaldson DR, Bearn PE, Scott HJ, Hassall AC. A study on the routes of referral for patients with colorectal cancer and its affect on the time to surgery and pathological stage. Colorect Dis 2004; 6: 428-431. [CrossRef]

- Cuffy M, Abir F, Audisio RA, Longo WE. Colorectal cancer presenting as surgical emergencies. Surg Oncol 2004; 13: 149-15. [CrossRef]

- Mihailov R, Firescu D, Constantin GB, Șerban C, Panaitescu E, Marica C, Bîrlă R, Pătrașcu T. Nomogram for prediction of postoperative morbidity in patients with colon cancer requiring emergency therapy. Medical science monitor 2022;e936303-1-11. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira F, Akaishi EH, Ushinohama AZ, et al. Can we respect the principles of oncologic resection in an emergency surgery to treat colon cancer? World J Emerg Surg 2015;10:5.

- Chalieopanyarwong V, Boonpipipattanapong T, Prechawittayakul P, et al. Endoscopic obstruction is associated with higher risk of acute events requiring emergency operation in colorectal cancer patients. World J Emerg Surg 2013;8:34. [CrossRef]

- Tekkis PP, Kinsman R, Thompson MR, Stamatakis JD, The Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland study of large bowel obstruction caused by colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 76-81. [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson H, Jennische K, Forssell S, et al. Heterogeneity of colon cancer patients reported as emergencies. World J Surg. 2014;38(7):1819-1826. [CrossRef]

- Renzi C, Lyratzopoulos G, Card T, Chu TP, Macleod U, Rachet B. Do colorectal cancer patients diagnosed as an emergency differ from non-emergency patients in their consultation patterns and symptoms? A longitudinal data-linkage study in England. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(7):866-875. [CrossRef]

- Bayar B, Yilmaz KB, Akinci M, et al. An evaluation of treatment results of emergency versus elective surgery in colorectal cancer patients. Ulus Cerrahi Derg 2016;32:11-7. [CrossRef]

- Bass G, Fleming C, Conneely J, et al. Emergency first presentation of colorectal cancer predicts significantly poorer outcomes: a review of 356 consecutive Irish patients. Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52(4):678-84.

- Alvarez JA, Baldonedo RF, Bear IG, et al. Presentation, treatment, and multivariate analysis of risk factors for obstructive and perforative colorectal carcinoma. Am J Surg 2005;190:376-82. [CrossRef]

- Hogan J, Samaha G, Burke J, et al. Emergency presenting colon cancer is an independent predictor of adverse disease-free survival. Int Surg. 2015;100(1):77-86. [CrossRef]

- Mantion G, Panis Y. Mortality and morbidity in colorectal surgery. Report of the Association franc¸aise de chirurgie. Paris: Arnette ed; 2003, 4-28.

- Rault A, Collet D, Sa Cunha A, Larroude D, Ndobo’epoy F, Masson B. Surgical management of obstructed colonic cancer. Ann Chir 2005;130:331-5.

- Alves A, Panis Y, Mathieu P, et al. Postoperative mortality and morbidity in French patients undergoing colorectal surgery: results of a prospective multicenter study. Arch Surg 2005;140(3):278-83.

- Carter Paulson E, Mahmoud N, Wirtalla C, Armstrong K. Acuity and survival in colon cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:385-92. [CrossRef]

- Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Sargent DJ, et al. Revised TN categorization for colon cancer based on national survival outcomes data. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:264-71. [CrossRef]

- O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Ko CY. Colon cancer survival rates with the new American Joint Committee on Cancer sixth edition staging. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:1420-5. [CrossRef]

- Cook AD, Single R and McCahill LE. Surgical resection of primary tumors in patients who present with stage IV colorectal cancer: an analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data, 1988 to 2000. Ann Surg Oncol 2005; 12: 637-645. [CrossRef]

- Disibio G and French SW. Metastatic patterns of cancers: results from a large autopsy study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008; 132: 931-939. [CrossRef]

- Hess KR, Varadhachary GR, Taylor SH, et al. Metastatic patterns in adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2006; 106: 1624-1633. [CrossRef]

- Weiss L, Grundmann E, Torhorst J, et al. Haematogenous metastatic patterns in colonic carcinoma: an analysis of 1541 necropsies. J Pathol 1986; 150: 195-203.

- Constantin GB, Firescu D, Mihailov R, Constantin I, Ștefanopol IA, Iordan AD, Ștefănescu BI, Bîrlă R, Panaitescu E. A novel clinical nomogram for predicting overall survival in patients with emergency surgery for colorectal cancer. Journal of personalized medicine 2023;13(575):1-17. [CrossRef]

- Mihailov R, Firescu D, Voicu D, Constantin GB, Beznea A, Rebegea L, Șerban C, Panaitescu E, Bîrlă R, Pătrașcu T. Challenges and solutions in choosing the surgical treatment in patients with complicated colon cancer operated in an emergency- a retrospective study. CHIRURGIA 2021;116(3):312-320. [CrossRef]

- Luțenco V, Rebegea L, Beznea A, Tocu G, Moraru M, Mihailov OM, Ciuntu BM, Luțenco V, Stanculea FC, Mihailov R. Innovative Surgical Approaches That Improve Individual Outcomes in Advanced Breast Cancer. Int J Womens Health. 2024;16:555-560. [CrossRef]

- Colon cancer surgery following emergency presentation: effects on admission and stage- adjusted outcomes Ramzi Amri, M.Sc., Liliana G. Bordeianou, M.D., M.P.H., Patricia Sylla, M.D., David L. Berger, M.D.*.

- Savu E, Vasile L, Serbanescu MS, Alexandru DO, Gheonea IA, Pirici D, Paitici S, Mogoanta SS. Clinicopathological Analysis of Complicated Colorectal Cancer: A Five- Year Retrospective Study from a Single Surgery Unit. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023 Jun 9;13(12):2016. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13122016. PMID: 37370913; PMCID: PMC10296966. [CrossRef]

- Iacopetta B. Are there two sides to colorectal cancer? Int J Cancer 2002;101:403-8. 267. Distler P, Holt PR. Are right- and left-sided colon neoplasms distinct tumors? Dig Dis 1997;15:302-11.

- 1, Mortality Risk Stratification in Emergency Surgery for Obstructive Colon Cancer-External Validation of International Scores, American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Surgical Risk Calculator (SRC), and the Dedicated Score of French Surgical Association (AFC/OCC Score) Raul Mihailov 1 , Dorel Firescu 1 , Georgiana Bianca Constantin 2 , Oana Mariana Mihailov 3 , Petre Hoara 4 , Rodica Birla 4,* , Traian Patrascu 4 and Eugenia Panaitescu.

- Konopke R, Schubert J, Stöltzing O, et al. Predictive factors of early outcome after palliative surgery for colorectal carcinoma. Innov Surg Sci. 2020;5(3-4):91-103; [CrossRef]

- Paolino J, Steinhagen MR. Colorectal surgery in cirrhotic patients.ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:239293;

- Lacatus M, Costin L, Bodean V, et al. The outcome of colorectal surgery in cirrhotic patients: A case match report. Chirurgia. 2018;113(2):210-17; [CrossRef]

- Kaser SA, Hofmann I, Willi N, et al. Liver Cirrhosis/Severe fibrosis is a risk factor for anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:1563037. [CrossRef]

- Arnarson Ö, Syk I, Butt ST. Who should operate patients presenting with emergent colon cancer? A comparison of short- and long-term outcome depending on surgical sub- specialization. World J Emerg Surg. 2023 Jan 9;18(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s13017-023-00474-y. PMID: 36624451; PMCID: PMC9830814. [CrossRef]

- Tan KK, Sim R. Surgery for obstructed colorectal malignancy in an Asian population: predictors of morbidity and comparison between left and right-sided cancers. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:295-302. [CrossRef]

- Nilssen Y, Eriksen MT, Guren MG, Møller B. Factors associated with emergency-onset diagnosis, time to treatment and type of treatment in colorectal cancer patients in Norway. BMC Cancer. 2021 Jun 30;21(1):757. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08415-1. PMID: 34187404; PMCID: PMC8244161. [CrossRef]

- Costa, Gianluca, Frezza, Barbara, Fransvea, Pietro, Massa, Giulia, Ferri, Mario, Mercantini, Paolo, Balducci, Genoveffa, Buondonno, Antonio, Rocca, Aldo and Ceccarelli, Graziano. "Clinico-pathologic features of colon cancer patients undergoing emergency surgery: a comparison between elderly and non-elderly patients" Open Medicine, vol. 14, no. 1, 2019, pp. 726-734. [CrossRef]

- Constantin GB, Firescu D, Voicu D, Ștefănescu B, Serban RMC, Berbece S, Panaitescu E, Bîrla R, Marica C, Constantinoiu S. Analysis of Prognostic Factors in Complicated Colorectal Cancer Operated in Emergency. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2020 Jan-Feb;115(1):23-38. doi: 10.21614/chirurgia.115.1.23. PMID: 32155397. [CrossRef]

- Constantin, Georgiana Bianca & Firescu, Dorel & Voicu, D. & Stefanescu, Bogdan & Mihailov, Raul & Serban, C. & Panaitescu, Eugenia & Birla, Rodica & Constantinoiu, Silviu. (2020). Emergency surgery for complicated colorectal cancer -What we choose: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of Military Medicine. CXXIII. 258-266. 10.55453/rjmm.2020.123.4.4.4. [CrossRef]

- Kurtoğlu Ahmet , Kurtoğlu Ertuğrul , Akgümüş Alkame , Çar Bekir , Eken Özgür , Sârbu Ioan , Ciongradi Carmen Iulia , Alexe Dan Iulian , Candussi Iuliana Laura, Evaluation of electrocardiographic parameters in amputee football players, Frontiers in Psychology 14, 2023, www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1189712 DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1189712 ISSN=1664-1078. [CrossRef]

- Constantin GB, Firescu D, Voicu D, Ștefănescu B, Serban RMC, Panaitescu E, Bîrlă R, Constantinoiu S. The Importance of Systemic Inflammation Markers in the Survival of Patients with Complicated Colorectal Cancer, Operated in Emergency. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2020 Jan-Feb;115(1):39-49. doi: 10.21614/chirurgia.115.1.39. PMID: 32155398. [CrossRef]

- Constantin GB, Firescu D, Mihailov R, Constantin I, Ștefanopol IA, Iordan AD, Ștefănescu BI, Panaitescu E, Constantinoiu S, Bîrlă R. The Systemic Infl ammation Marker NLR as a Prognostic Factor in Complicated Colorectal Cancer. 2023 Jan 31; 4(1): 141-149. doi: 10.37871/jbres1658, Article ID: JBRES1658, Available at: https://www.jelsciences.com/articles/jbres1658.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Peng H, Liu G, Bao Y, Zhang X, Zhou L, Huang C, Song C, Song Z, Cao S, Dang S, Zhang J, Huang T, Wu Y, Wu Y, Xu M, Song L, Cao P. Prognostic Factors of Colorectal Cancer: A Comparative Study on Patients With or Without Liver Metastasis. Front Oncol. 2021 Dec 21;11:626190. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.626190. PMID: 34993129; PMCID: PMC87243310. [CrossRef]

- Eom T, Lee Y, Kim J, Park I, Park I, Gwak G, Cho H, Yang K, Kim K, Bae BN. Prognostic Factors Affecting Disease-Free Survival and Overall Survival in T4 Colon Cancer. Ann Coloproctol. 2021 Aug;37(4):259-265. doi: 10.3393/ac.2020.00759.0108. Epub 2021 Jun 24. Erratum in: Ann Coloproctol. 2023 Oct;39(5):444. doi: 10.3393/ac.2020.00759.0108.0108.e1. PMID: 34167188; PMCID: PMC8391044. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

| |

|

Postoperative deaths - No |

Postoperative deaths - Yes |

p-value (test) |

| Age groups |

≤68 years |

38/83 (45.78%) |

5/12 (41.67%) |

0.789(1)

|

| |

>68 years |

45/83 (54.22%) |

7/12 (58.33%) |

|

| Sex |

M |

41/83 (49.40%) |

11/12 (91.67%) |

0.006(1)

|

| |

F |

42/83 (50.60%) |

1/12 (8.33%) |

|

| Urban/rural area |

U |

60/83 (72.29%) |

9/12 (75.00%) |

0.844(1)

|

| |

R |

23/83 (27.71%) |

3/12 (25.00%) |

|

| Abdominal pain |

No |

3/83 (3.61%) |

2/12 (16.67%) |

0.058(1)

|

| |

Yes |

80/83 (96.39%) |

10/12 (83.33%) |

|

| Absence of transit |

No |

43/83 (51.81%) |

6/12 (50.00%) |

0.907(1)

|

| |

Yes |

40/83 (48.19%) |

6/12 (50.00%) |

|

| Nausea |

No |

8/83 (9.64%) |

2/12 (16.67%) |

0.458(1)

|

| |

Yes |

75/83 (90.36%) |

10/12 (83.33%) |

|

| Vomiting |

No |

28/83 (33.73%) |

6/12 (50.00%) |

0.272(1)

|

| |

Yes |

55/83 (66.27%) |

6/12 (50.00%) |

|

| Weight loss |

No |

74/83 (89.16%) |

5/12 (41.67%) |

0.000(1)

|

| |

Yes |

9/83 (10.84%) |

7/12 (58.33%) |

|

| Lower digestive hemorrhage |

No |

78/83 (93.98%) |

11/12 (91.67%) |

0.759(1)

|

| |

Yes |

5/83 (6.02%) |

1/12 (8.33%) |

|

| app non neo 1/0 |

No |

31/83 (37.35%) |

2/12 (16.67%) |

0.160(1)

|

| |

Yes |

52/83 (62.65%) |

10/12 (83.33%) |

|

| app neopl 1/0 |

No |

81/83 (97.59%) |

11/12 (91.67%) |

0.273(1)

|

| |

Yes |

2/83 (2.41%) |

1/12 (8.33%) |

|

| Onset of symptoms |

≤1 day |

7/83 (8.43%) |

0/12 (0.00%) |

0.277(2)

|

| |

2-5 days |

47/83 (56.63%) |

6/12 (50.00%) |

|

| |

>14 days |

29/83 (34.94%) |

6/12 (50.00%) |

|

| Type of general status |

0 |

18/83 (21.69%) |

0/12 (0.00%) |

0.000(2)

|

| |

1 |

30/83 (36.14%) |

1/12 (8.33%) |

|

| |

2 |

27/83 (32.53%) |

4/12 (33.33%) |

|

| |

3 |

6/83 (7.23%) |

3/12 (25.00%) |

|

| |

4 |

2/83 (2.41%) |

4/12 (33.33%) |

|

| Cachexia |

No |

76/83 (91.57%) |

4/12 (33.33%) |

0.000(1)

|

| |

Yes |

7/83 (8.43%) |

8/12 (66.67%) |

|

| Leukocytes |

N |

46/83 (55.42%) |

2/12 (16.67%) |

0.012(1)

|

| |

P |

37/83 (44.58%) |

10/12 (83.33%) |

|

| Anemia |

No |

21/83 (25.30%) |

0/12 (0.00%) |

0.048(1)

|

| |

Yes |

62/83 (74.70%) |

12/12 (100.00%) |

|

| Platelets |

P |

7/83 (8.43%) |

7/12 (58.33%) |

0.000(1)

|

| |

N |

76/83 (91.57%) |

5/12 (41.67%) |

|

| Blood glucose |

P |

19/83 (22.89%) |

7/12 (58.33%) |

0.010(1)

|

| |

N |

64/83 (77.11%) |

5/12 (41.67%) |

|

| Creatinine |

P |

30/83 (36.14%) |

8/12 (66.67%) |

0.044(1)

|

| |

N |

53/83 (63.86%) |

4/12 (33.33%) |

|

| Electrolyte disorders |

No |

57/83 (68.67%) |

3/12 (25.00%) |

0.003(1)

|

| |

Yes |

26/83 (31.33%) |

9/12 (75.00%) |

|

| Acidosis |

No |

68/83 (81.93%) |

7/12 (58.33%) |

0.061(1)

|

| |

Yes |

15/83 (18.07%) |

5/12 (41.67%) |

|

| Total proteins |

N |

10/83 (12.05%) |

0/12 (0.00%) |

0.039(1)

|

| |

P |

12/83 (14.46%) |

6/12 (50.00%) |

|

| Albumin |

N |

7/83 (8.43%) |

0/12 (0.00%) |

0.186(1)

|

| |

P |

11/83 (13.25%) |

3/12 (25.00%) |

|

| Coagulation disorders |

No |

73/83 (87.95%) |

9/12 (75.00%) |

0.222(1)

|

| |

Yes |

10/83 (12.05%) |

3/12 (25.00%) |

|

| Location code |

C18.0 |

36/83 (43.37%) |

6/12 (50.00%) |

0.738(2)

|

| |

C18.2 |

17/83 (20.48%) |

3/12 (25.00%) |

|

| |

C18.3 |

30/83 (36.14%) |

3/12 (25.00%) |

|

| Preop. diagnosis |

H |

8/83 (9.64%) |

1/12 (8.33%) |

0.227(2)

|

| |

O |

69/83 (83.13%) |

8/12 (66.67%) |

|

| |

P |

6/83 (7.23%) |

3/12 (25.00%) |

|

| Intra-oper. complications |

No |

80/83 (96.39%) |

11/12 (91.67%) |

0.447(1)

|

| |

Yes |

3/83 (3.61%) |

1/12 (8.33%) |

|

| Septic status |

No |

81/83 (97.59%) |

8/12 (66.67%) |

0.000(1)

|

| |

Yes |

2/83 (2.41%) |

4/12 (33.33%) |

|

| Interval-intervention |

<12 h |

36/83 (43.37%) |

6/12 (50.00%) |

0.659(2)

|

| |

12-24 h |

15/83 (18.07%) |

1/12 (8.33%) |

|

| |

>24 h |

32/83 (38.55%) |

5/12 (41.67%) |

|

| Scar abdomen |

No |

64/83 (77.11%) |

7/12 (58.33%) |

0.162(1)

|

| |

Yes |

19/83 (22.89%) |

5/12 (41.67%) |

|

| Operation type |

1 |

2/83 (2.41%) |

1/12 (8.33%) |

0.353 (2)

|

| |

3 |

17/83 (20.48%) |

4/12 (33.33%) |

|

| |

4 |

64/83 (77.11%) |

7/12 (58.33%) |

|

| Associated maneuvers |

- |

71/83 (85.54%) |

7/12 (58.33%) |

0.112(2)

|

| |

Major |

7/83 (8.43%) |

3/12 (25.00%) |

|

| |

Mino |

5/83 (6.02%) |

2/12 (16.67%) |

|

| Other organs invasion |

No |

69/83 (83.13%) |

11/12 (91.67%) |

0.449(1)

|

| |

Yes |

14/83 (16.87%) |

1/12 (8.33%) |

|

| Metastases |

No |

64/83 (77.11%) |

8/12 (66.67%) |

0.430(1)

|

| |

Yes |

19/83 (22.89%) |

4/12 (33.33%) |

|

| Preparation of colon |

No |

3/83 (3.61%) |

2/12 (16.67%) |

0.058(1)

|

| |

Yes |

80/83 (96.39%) |

10/12 (83.33%) |

|

| Postop. complications |

No |

69/83 (83.13%) |

0/12 (0.00%) |

0.000(1)

|

| |

Yes |

14/83 (16.87%) |

12/12 (100.00%) |

|

| Reinterventions |

No |

80/83 (96.39%) |

12/12 (100.00%) |

0.503(1)

|

| |

Yes |

3/83 (3.61%) |

0/12 (0.00%) |

|

| Scheme type |

1 |

44/83 (53.01%) |

4/12 (33.33%) |

0.110(2)

|

| |

2 |

23/83 (27.71%) |

5/12 (41.67%) |

|

| |

3 |

12/83 (14.46%) |

2/12 (16.67%) |

|

| |

4 |

4/83 (4.82%) |

1/12 (8.33%) |

|

| Number of hospitalization days |

<15 days |

31/83 (37.35%) |

7/12 (58.33) |

0.165(2)

|

| |

≥15 days |

52/83 (62.65%) |

5/12 (41.67) |

|

| Total |

|

83 |

12 |

|

Table 3.

| Postoperative deaths |

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Std. Error Mean |

| DAVIES score |

NO |

83 (87.37%) |

1.759 |

0.7423 |

0.0815 |

| |

YES |

12 (12.63%) |

2.167 |

0.8348 |

0.2410 |

| CHARLSON score |

NO |

83 (87.37%) |

4.265 |

2.8331 |

0.3110 |

| |

YES |

12 (12.63%) |

5.750 |

2.8644 |

0.8269 |

| CHARLSON adjusted score |

NO |

83 (87.37%) |

10.639 |

3.1990 |

0.3511 |

| YES |

12 (12.63%) |

12.000 |

3.0748 |

0.8876 |

| Number of hospitalization days |

NO |

83 (87.37%) |

16.494 |

6.0975 |

0.6693 |

| YES |

12 (12.63%) |

13.250 |

11.6395 |

3.3600 |

Table 4.

| |

|

Mean Estimate |

p-value

Log Rank (Mantel-Cox) |

Univariate |

|

| HR (95%CI) |

p_value |

| Age groups |

≤68 years |

79.953 |

0.845 |

1.120 (0.355, 3.529) |

0.846 |

| |

>68 years |

79.115 |

|

|

|

| Sex |

M |

72.481 |

0.007 |

0.102 (0.013, 0.787) |

0.029 |

| |

F |

87.977 |

|

|

|

| Urban/rural area |

U |

79.145 |

0.835 |

0.871 (0.236, 3.271) |

0.836 |

| |

R |

80.423 |

|

|

|

| Abdominal pain |

NO |

59.200 |

0.071 |

0.273 (0.060, 1.246) |

0.094 |

| |

YES |

80.622 |

|

|

|

| Absence of transit |

NO |

79.857 |

0.897 |

1.077 (0.347, 3.339) |

0.898 |

| |

YES |

79.109 |

|

|

|

| Nausea |

NO |

73.800 |

0.487 |

0.589 (0.129, 2.690) |

0.495 |

| |

YES |

80.165 |

|

|

|

| Vomiting |

NO |

75.912 |

0.317 |

0.567 (0.183, 1.758) |

0.326 |

| |

YES |

81.492 |

|

|

|

| Weight loss |

NO |

84.899 |

0.000 |

8.941 (2.824, 28.303) |

0.000 |

| |

YES |

52.813 |

|

|

|

| Lower digestive hemorrhage |

NO |

79.708 |

0.769 |

1.355 (0.175, 10.496) |

0.771 |

| |

YES |

76.333 |

|

|

|

| app non neo 1/0 |

NO |

85.242 |

0.152 |

2.867 (0.628, 13.087) |

0.174 |

| |

YES |

76.435 |

|

|

|

| app neopl 1/0 |

NO |

80.043 |

0.267 |

2.995 (0.386, 23.239) |

0.294 |

| |

YES |

62.667 |

|

|

|

| Onset of symptoms |

≤1 day |

|

0.459 |

1.344 (0.790, 2.285) |

0. 276 |

| |

2-5 days |

|

|

|

|

| |

>14 days |

|

|

|

|

| Cachexia |

NO |

85.863 |

0.000 |

14.179 (4.246, 47.346) |

0.000 |

| |

YES |

45.533 |

|

|

|

| White blood cells |

N |

86.542 |

0.012 |

5.565 (1.219, 25.408) |

0.027 |

| |

P |

72.298 |

|

|

|

| Anemia |

NO |

|

0.054 |

30.467 (0.101, 9195.175) |

0.271 |

| |

YES |

|

|

|

|

| Platelets |

P |

48.500 |

0.000 |

0.097 (0.031, 0.307) |

0.000 |

| |

N |

84.852 |

|

|

|

| Blood glucose |

P |

67.538 |

0.008 |

0.243 (0.077, 0.766) |

0.016 |

| |

N |

84.000 |

|

|

|

| Creatinine |

P |

72.395 |

0.043 |

0.312 (0.094, 1.037) |

0.047 |

| |

N |

84.228 |

|

|

|

| Electrolyte disorders |

NO |

85.850 |

0.003 |

5,711 (1.545, 21.105) |

0.009 |

| |

YES |

68.600 |

|

|

|

| Acidosis |

NO |

82.360 |

0.048 |

2.972 (0.942, 9.371) |

0.048 |

| |

YES |

68.750 |

|

|

|

| Coagulation disorders |

NO |

80.951 |

0.196 |

2.299 (0.622, 8.496) |

0.212 |

| |

YES |

70.308 |

|

|

|

| Location code |

C18.0 |

77.833 |

0.728 |

0.873 (0.572, 1.330) |

0.526 |

| |

C18.2 |

77.550 |

|

|

|

| |

C18.3 |

82.788 |

|

|

|

| Preop. diagnosis |

H |

80.889 |

0.109 |

2.601 (0.751, 9.002) |

0.131 |

| |

O |

81.390 |

|

|

|

| |

P |

61.889 |

|

|

|

| Intra-oper. complications |

NO |

79.879 |

0.497 |

1.988 (0.258, 15.482) |

0.508 |

| |

YES |

70.750 |

|

|

|

| Septic status |

NO |

82.629 |

0.000 |

12.186 (3.631, 40.895) |

0.000 |

| |

YES |

33.000 |

|

|

|

| Interval-interventions |

<12 h |

77.881 |

0.708 |

0.944 (0.506, 1.762) |

0.857 |

| |

12-24 h |

84.563 |

|

|

|

| |

>24 h |

79.135 |

|

|

|

| Scar abdomen |

NO |

81.718 |

0.167 |

2.191 (0.695, 6.906) |

0.181 |

| |

YES |

72.917 |

|

|

|

| Operation type |

1 |

61.000 |

0.240 |

0.599 (0.323, 1.110) |

0.103 |

| |

3 |

73.714 |

|

|

|

| |

4 |

81.986 |

|

|

|

| Associated maneuvers |

- |

82.436 |

0.077 |

0.292 (0.061, 1.407) |

0.125 |

| |

Major |

65.900 |

|

|

|

| |

Mino |

66.143 |

|

|

|

| Other organs invasion |

NO |

78.613 |

0.465 |

0.476 (0.061, 3.690) |

0.478 |

| |

YES |

84.200 |

|

|

|

| Metastases |

NO |

80.958 |

0.393 |

1.673 (0.504, 5.561) |

0.401 |

| |

YES |

74.913 |

|

|

|

| Colon preparation |

NO |

57.200 |

0.053 |

0.252 (0.055, 1.150) |

0.075 |

| |

YES |

80.733 |

|

|

|

| Scheme type |

1 |

83.063 |

0.602 |

1.378 (0.776, 2.446) |

0.274 |

| |

2 |

75.357 |

|

|

|

| |

3 |

78.143 |

|

|

|

| |

4 |

72.200 |

|

|

|

| Number of hospitalization days |

<15 days |

74.316 |

0.147 |

0.440 (0.140, 1.386) |

0.161 |

| |

≥15 days |

82.947 |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).