1. Introduction

The residual stresses in multilayer coatings are strongly dependent on several factors such as layer thickness and numbers, coating and substrate materials, thermal expansion coefficient mismatch between substrate and coating material, deposition techniques, process parameters and working pressure (Huff, 2022). These stresses are critical in multilayer structures and play an important role in the performance and reliability of coatings, impacting mechanical and physical properties like hardness, adhesion, fracture, fatigue and corrosion resistance. Therefore, it is essential to understand the origin and evaluation of residual stresses in coatings by means of suitable and reliable techniques, and to develop methods to predict and control them to be able to design multilayer films with high performance (Sebastiani et al., 2020). The residual stresses are determined in the form of elastic strain and for analyzing the depth profile of residual strain, it is important to understand the in-depth lattice strain functions (Bemporad et al., 2014; Korsunsky et al., 2010).

Nowadays, residual stress measurements are generally conducted with more advanced techniques with spatial resolution ranging from micron to sub-nano level. Most commonly these are divided into three categories named as non-destructive, destructive and semi-destructive techniques. Non-destructive residual stress measurement includes ultrasonic method (Hwang et al., 2021; Zhan et al., 2017), laser acoustic wave method (L. Zhang et al., 2022), diffraction method (Genzel & Reimers, 2022), Raman spectroscopy method (Ye & Jiang, 2020), and HRSTEM-GPA method (Quillin et al., 2023). Destructive techniques consist of counter, crack compliance and stripping methods (GUO et al., 2021; Nervi & Szabó, 2007). Lastly, semi-destructive techniques combine the above two, including the hole-drilling (Bobzin et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2021) and the FIB-DIC ring-core milling method (Sebastiani et al., 2011, 2020).

Here in this article, the residual stress measurements are performed using non-destructive HRSTEM-GPA technique and semi-destructive FIB-DIC technique. The non-destructive high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) can provide quantitative information on the elastic strain present in materials at sub-nanometric scale. Two types of image processing methods can be employed to extract deformation maps from lattice spacing variations across HRTEM images: geometric phase analysis (GPA) which relies on Fourier space information (Hÿtch et al., 1998; M.J. Hÿtch, 1997) and real-space peak-finding methods (Galindo et al., 2007) that benchmark the position of intensity maxima in the area under analysis against the intensity distribution in a non-distorted lattice region. Both approaches yield similar results, however, real space algorithms typically require human intervention when dealing with the highly distorted dislocation cores, while GPA is not only straightforwardly employed but also generates deformation maps in agreement with the linear elastic theory of dislocations (Hÿtch et al., 2003, 2006).

The Fourier Transform (FT) of a perfect lattice image gives rise to sharply peaked frequencies (Bragg spots), while local variations in interplanar distance produce diffuse intensity centered around the mean Bragg spots. GPA is based on filtering with a numerical aperture specific Bragg spots and corresponding diffuse intensity. The Fourier coefficients Hg are allowed to become a function of position r in the image (Hg(r)), and the Δg deviations can consequently be equated to an additional phase term P(r) in the Fourier coefficient mapped in real space. The fundamental assumption of the methodology lies in assuming that each set of real-space lattice fringes can be described by the mean frequency g with the local displacement of the sinusoidal function dictated by the phase. The vectorial displacement field can then be directly inferred from. Thus, phase maps of two non-colinear g can be used to generate strain maps by differentiation. The P(r) phase is called geometric as it pertains to changes in the position of lattice fringes in an image rather than to the phase of periodicities in the electron wavefunction emerging from the crystal.

In general, the reliability of strain mapping relies on the constant spatial relationship between the intensity maxima in the image and the relative positions of the atomic columns in the specimen, which is the hallmark of high angle annular dark field images in high resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (HRSTEM). Nevertheless, the method is relative and does not allow to determine the absolute distortion field present in the sample. In addition, it can be affected by thin foil relaxation, local crystal tilts and thickness and/or composition variations.

The semi-destructive Focused Ion Beam – Digital Image Correlation (FIB-DIC) ring-core milling technique can be used to measure the residual stresses at sub-micron level, is an accurate method that does not completely damage the crystal structure and is unaffected by the amorphous structure (Korsunsky et al., 2009). The technique is a combination of FIB ring-core milling, acquiring high-resolution scanning electron microscopy (HRSEM) images after each milling step, and surface displacement calculation using MATLAB-based DIC analysis (Lord et al., 2018; Lunt et al., 2015).

FIB micro-milling induces controlled strain relaxation at the stressed coating surfaces. Then the relaxation strain is measured at the coating’s surface of HRSEM micrographs using DIC MATLAB based routine, and residual stress profile throughout the coating thickness is then calculated from the MATLAB-based ResIdual Stress Evaluation (RISE) toolbox (considering number of coating layers, layer thicknesses, pillar diameter, relaxation strain, elastic modulus and poison’s ratio of both substrate and coating layers, respectively) (Zeng et al., 2024). The FIB-DIC method has been widely used and proved its accuracy for semi-destructive residual stress measurement of thin films (Chen et al., 2020; Korsunsky et al., 2009; Salvati et al., 2019; Sebastiani et al., 2011, 2014), numerous researchers have used the conventional calibration coefficient for the depth resolved residual stress calculation especially for the multilayer coatings as its evaluating the stress profile throughout the coating thickness.

In this article, the heterogeneous AlGaN and GaN multilayer coatings were deposited on a sapphire substrate using metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy (MOVPE) method. These coatings exhibit excellent optical and structural properties that make them good candidates for optical applications such as optical sensors (Yin et al., 2021). Some previous studies state that AlGaN/AlN/GaN heterogeneous structures grown on epitaxial AlN/Sapphire substrate show high electron Hall mobility of 2500 cm2/Vs that corresponds to efficient and fast charge transfer, essential for applications like transport conductive oxides, photovoltaic cells, and electronic devices (Miyoshi et al., 2004). The AlN/GaN/sapphire heterostructure shows temperature coefficient of frequency (TCF) value of -34.6 ppm/oC, demonstrating the potential of the waveguiding layer acoustic waves (WLAW) that makes them suitable for high temperature package less acoustic wave devices(Bartoli et al., 2018). These high-quality, low-sheet-resistive layers are of key importance to avoid current crowding in quaternary AlGaN/GaN multiple-quantum-well deep-ultraviolet light-emitting diodes over sapphire substrates (J. P. Zhang et al., 2002).

The aim of this study was to assessment of residual stresses within the multilayer coatings thicknesses and make a critical comparison between two different techniques (non-destructive and semi-destructive) exhibiting different levels of spatial resolutions, ranging from sub-micron to sub-nano level, in order to check the reliability and compatibility of both techniques in terms of accuracy and efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production of Multilayer Coatings

The investigated structures have been epitaxially grown on single side polished, two-inch diameter, 430 ± 15µm thick sapphire substrates. The C-plane (0001)-oriented substrates with off angle toward M-axis 0.2 ± 0.1° and toward A-axis 0 ± 0.1° have been chosen as a standard alternative substrate for epitaxial growth of nitrides. The quality of the substrates was defined by the supplier by the etch pits density (EPD) at the level lower than 5E8/cm

2, total thickness variation (TTV) ≤10 µm and bowing < 10 µm. The growth of the periodical structures has been preceded by metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy (MOVPE) method in a vertical flip-top closed coupled showerhead (FT 3x2 CCS) AIXTRON reactor, designed for three 2’ diameter wafers. For the growth of nitrides, hydrogen (H2) was used as a carrier gas and ammonia (NH3), trimethylgallium (TMGa), trimethylaluminium (TMAl) as precursors. Standard of 1.7 µm thick undoped GaN buffer layer and subsequent undoped Al

048Ga

0.52N /GaN (Sample A) or Al

0.22Ga

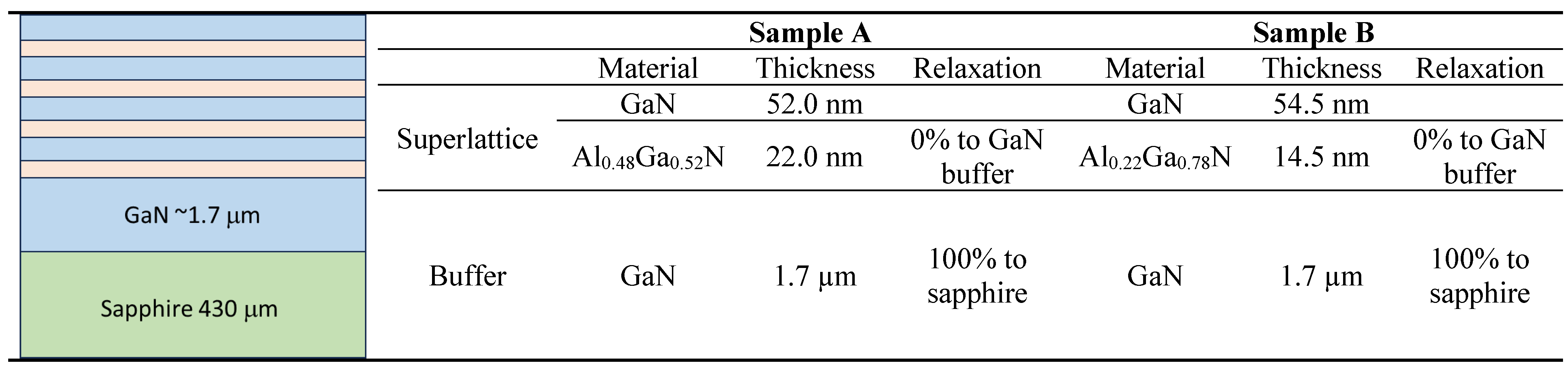

0.78N/GaN (Sample B) periodical structures have been grown at 50 mbar in the reactor and at 1060 and 1080°C for the buffer and superlattices respectively. In situ reflectance monitoring was performed using a Laytec EpiTT system operating with a 633 nm laser. Emissivity-corrected pyrometry (true temperature) was used to determine the sample surface temperature during growth. The schematic illustrations of investigated multilayer coating structure geometry with the thickness measurement of each layer are presented in

Table 1. The multilayer coatings exhibit four alternative sublayers of AlGaN and GaN with the total thickness of 296 nm and 276 nm for sample A and B, respectively. In both cases, a 1.7 µm thick buffer layer of GaN was used for better adhesion and growth of the coatings.

Table 1.

The structural data of the investigated samples A and B.

Table 1.

The structural data of the investigated samples A and B.

2.2. XRD Analysis

High resolution X-ray diffraction technique (HRXRD) was used to determine structural data of each investigated sample. HRXRD scans of 00.2 reflection were performed, and asymmetrical 11.4 reciprocal space maps (RSMs) were obtained to determine the thicknesses, composition, relaxation and crystal quality of the subsequently grown layers. All structural data have been determined by means of curves fitting to the 2theta/omega scan of 00.2 reflection preceded by analysis of reciprocal space maps around the 11.4 lattice point. The Empyrean X-ray diffractometer equipped with Cu kα1 = 1.540597 Å wavelength source and supported by a Pixcel3D detector with a hybrid monochromator in incidence beam mode has been used for that investigation. The quality of the epitaxial samples, including interface sharpness and uniformity were verified by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging.

2.3. GPA Suitability

GPA can be successfully employed to map elastic strain provided the sample is not extremely deformed, since the atomic columns need to be clearly discerned, and an unstrained region with the same crystallographic orientation is present in every field-of-view to be used as reference. The localized strain associated with coherent interfaces or semi-coherent interfaces with misfit dislocations is particularly suited for GPA. However, these extended defects must be observed in edge-on and end-on orientations, respectively. The AlGaN/GaN multilayer coatings produced by MOVPE exhibited localized strain at the interfaces and relatively defect-free regions in the layers, rendering them suitable for GPA. In contrast, the generalized high level of residual strain and small crystallite sizes in the samples prepared by sputtering precluded the use of GPA.

2.4. TEM Lamella Preparation

Lamellas of the multilayer samples produced by sputtering and pulsed laser deposition were precisely sectioned with a gallium focused ion beam using an FEI Helios G4 Dual-Beam instrument at 30 kV and, subsequently, polished at 5 and 2 kV for removal of amorphous layers.

2.5. High Resolution – Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (HR-STEM) and Geometric Phase Analysis (GPA)

A DCOR Cs probe-corrected FEI Titan G2 60-300 instrument, with 0.08 nm nominal spatial resolution when operated at 200 kV, was used for the HRSTEM work. A high-angle annular dark field obtained with a convergence angle of 22 mrad was employed for image acquisition.

The distribution of misfit strain at the interfaces between the layers produced by PLD was evaluated by GPA using the FRWR tools plugin for digital micrograph. This method was used to investigate type-III residual stresses (σRS, III) existing over atomic dimensions.

The key steps of GPA involved:

Selection of two non-colinear reciprocal vectors g1 and g2 from the power spectrum.

Selection of the size of the Gaussian mask (resolution).

Selection of a reference image from which the positions of the mean g vectors were established, and around which the masks were centered.

The two-phase maps were used to calculate the local displacement and map the strain components and the rotation.

2.6. Focused Ion Beam – Digital Image Correlation (FIB-DIC) Method

The residual stress measurements were carried out by the FIB-DIC micro-ring core method on a FEI Helios Nanolab 600 dual beam focused ion beam scanning electron microscope (FIB/SEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), using a specifically developed automated procedure (Sebastiani et al., 2011). The milling was performed using an annular trench with an inner diameter of 2 µm while employing a current of 28 pA at the acceleration voltage of 30 kV. Ten high resolution secondary electron images were acquired before and after each milling step using an integral of 150 images at a dwell time of 50 ns. The automatic procedure continuously monitored and corrected electron and ion beam drift while maintaining the same contrast of the reference image. The milling was performed until the h/D ratio of 0.2 was achieved, where h and D represent the milling depth and the pillar diameter, respectively. The h/D ratio of 0.2 ensures an optimal strain relief, as demonstrated in several recent publications (Korsunsky et al., 2018; Salvati et al., 2019; Sebastiani et al., 2020). After the milling cycle, all the HRSEM images were processed with a customized MATLAB v2.1.0.0 based DIC code(MATLAB Central. Digital Image Correlation and Tracking., 2016) to calculate the relaxation strain over the pillar surface. The residual stress profiles in the multilayer coatings were calculated using RISE toolbox MATLAB-based routines that considered relaxation strain calculated by DIC as input and elastic modulus (E) and Poisson’s ratio (v) for both coatings and substrate material.

3. Results

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction

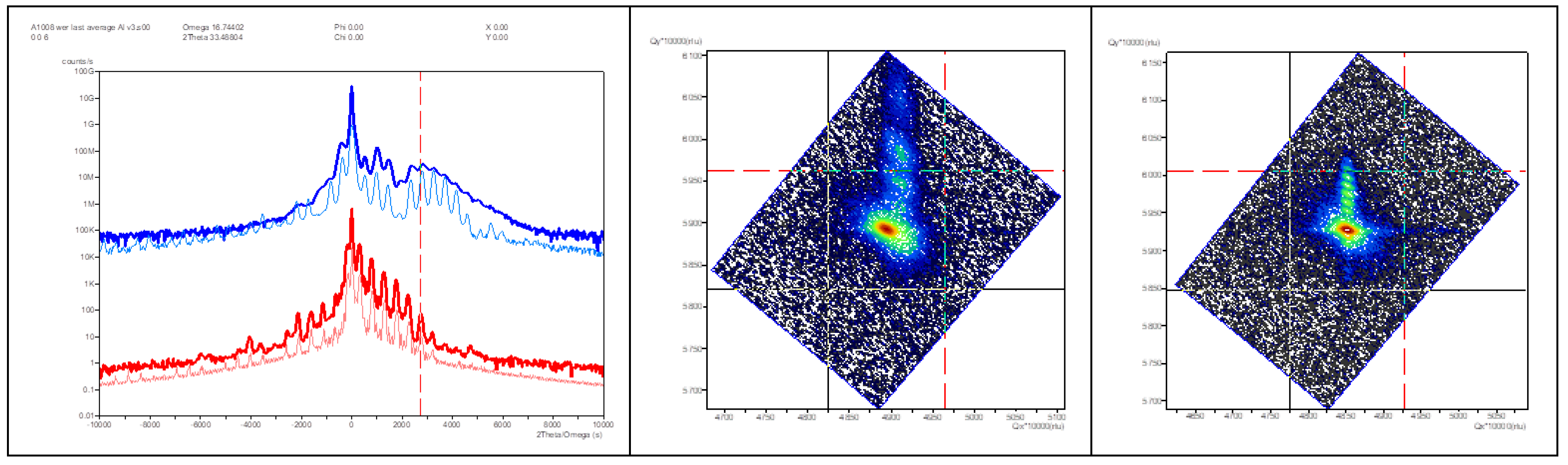

The X-ray diffraction scans show the epitaxial growth of both sets of multilayer coatings on sapphire substrate which makes them suitable for the HRSTEM-GPA analysis for the evaluation of the localized strain at the sub-nano level. The reciprocal space maps (RSMs) measured using XRD as shown in

Figure 1. It is confirmed that the crystal quality of the AlGaN and GaN layers becomes better with increasing distance of the respective layer from the substrate. This improvement, which concerns mainly a decrease of the dislocation density and a reduction of the mosaicity of the layers, is visible on the width of the 11.4 reciprocal lattice points. The detailed sublayers geometrical growth and coating thicknesses of each layer are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. GPA Method

The GPA can only be used reliably for localized strain mapping. Annealing was performed for 2 hours at 600 °C on a piece of the CTN CT 4 layers sample to characterize the stress at the interfaces. However, the stress level was still at levels high enough to prevent effective GPA. It was then decided to produce films with epitaxial interfaces. Then multilayers consisting of Al0.48Ga0.52N/GaN (A) and Al0.22Ga0.78N/GaN (B) were produced, sectioned by focused ion-beam for STEM and analyzed by GPA. The analysis was carried out in 5 regions of sample A.

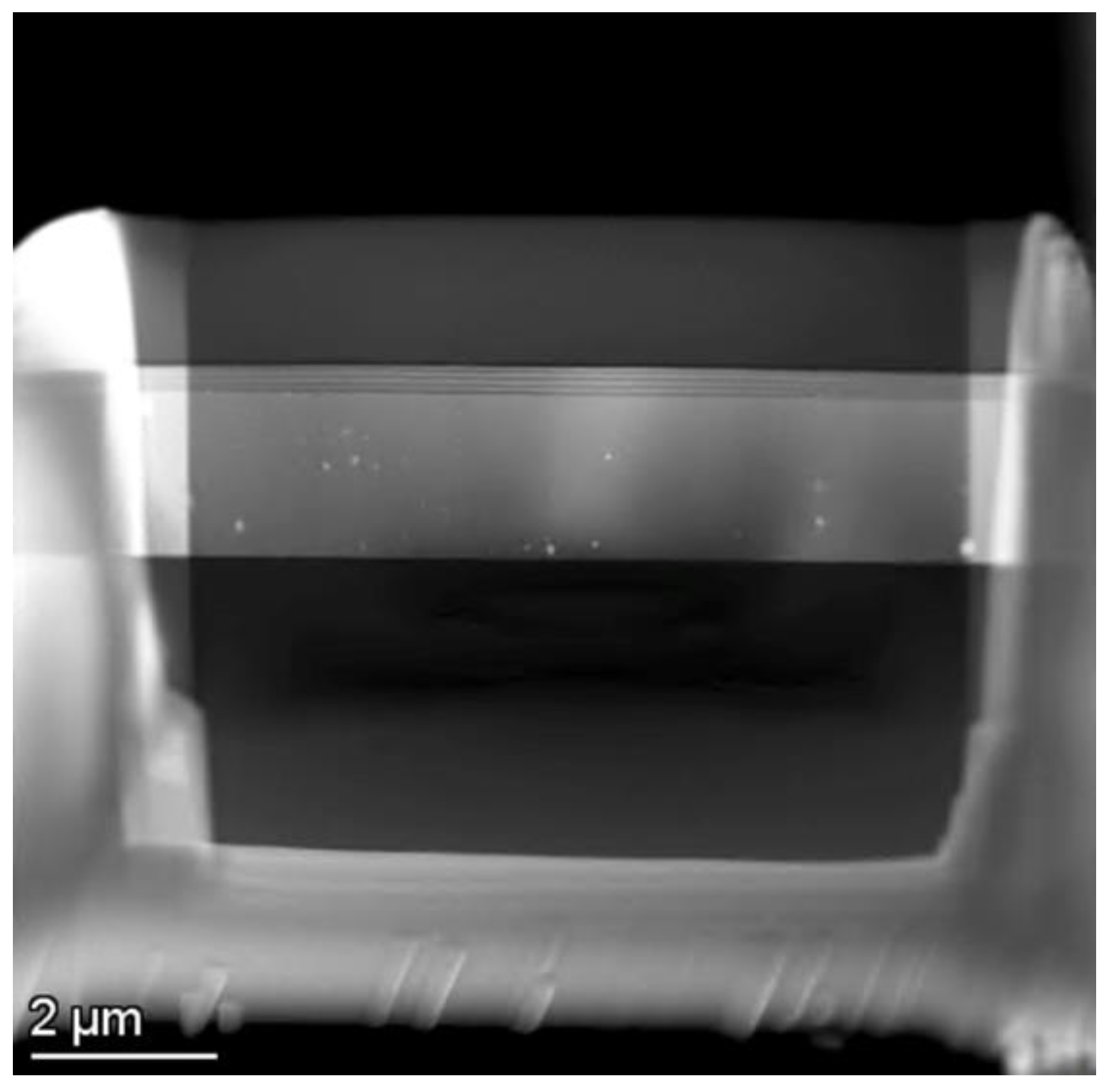

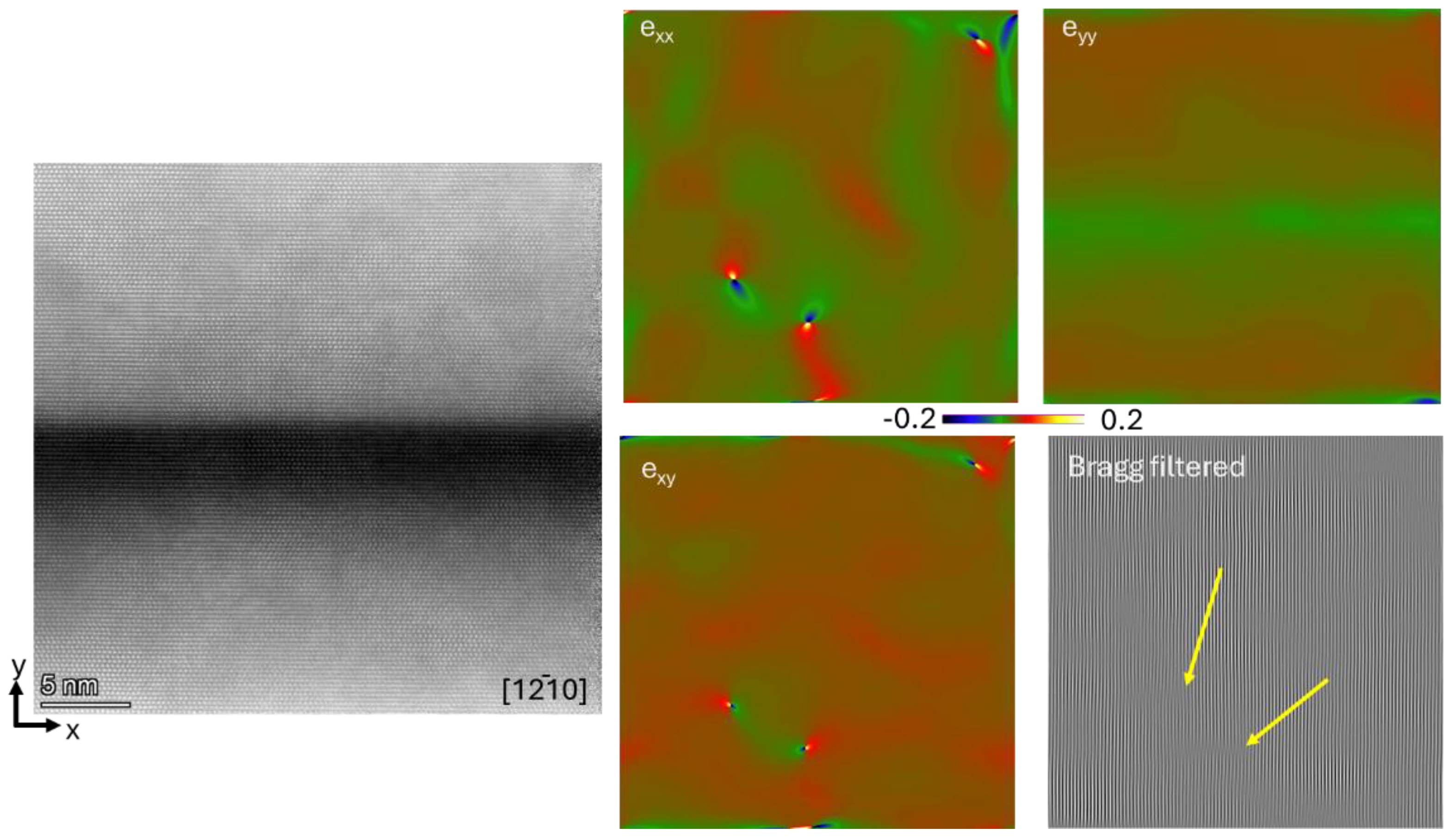

The GPA results Indicate that the thin film exhibits residual compressive stress both In plane and perpendicular to the substrate. The STEM lamella of Al

0.22Ga

0.78N/GaN was prepared by FIB as shown in

Figure 2.

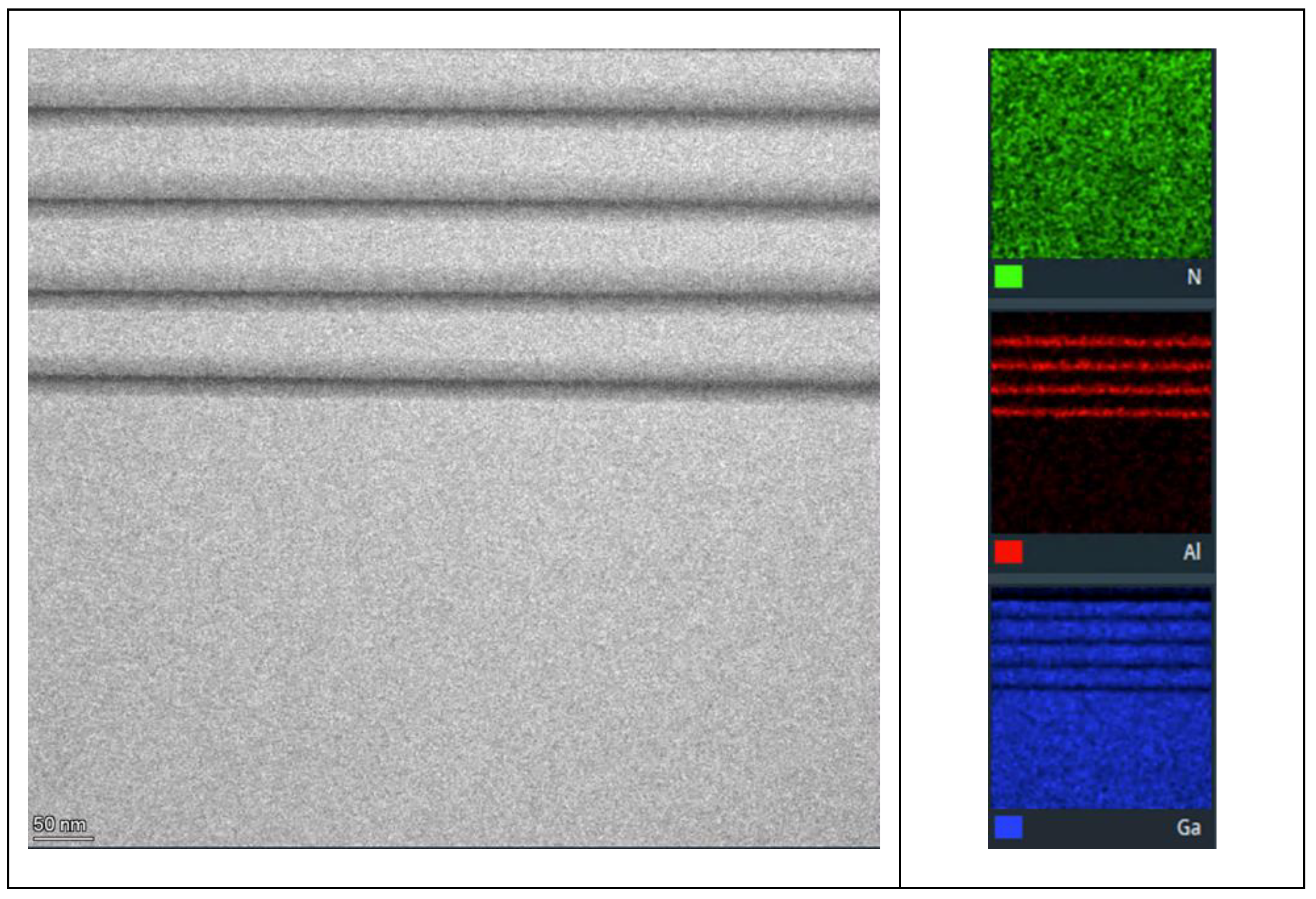

The Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) analysis was performed in order to determine the layer microstructure and identify the elemental composition of the layer’s material to assess its integrity and uniformity as shown in

Figure 3. The SEM-EDS analysis confirms the expected elemental composition of the multilayer coating, the color-coded maps showing the distribution of the key elements (Al, Ga and N) in the coating.

Figure 4 and 5 present illustrative examples of the GPA measurements performed on the Al

0.48Ga

0.52N/GaN (A) and Al

0.22Ga

0.78N/GaN (B), respectively. The colored images show the long-range stress fields emanating from misfit interfacial dislocations (b, c, d). Bragg-filtered images revealing the position of the edge dislocations are also presented ©.

The TEM-GPA method successfully maps the localized strain states associated with misfit dislocations in the two sets of multilayer coatings with different layer geometries (Sample A and B). The average stresses extracted from 5 different regions in each sample yielded the average stress state. These results are statistically limited due to the scale of lattice images. Still, they allow interpreting the contribution of the localized interfacial strain to the overall residual stress of the coatings as shown in

Table 2.

3.3. FIB-DIC Method

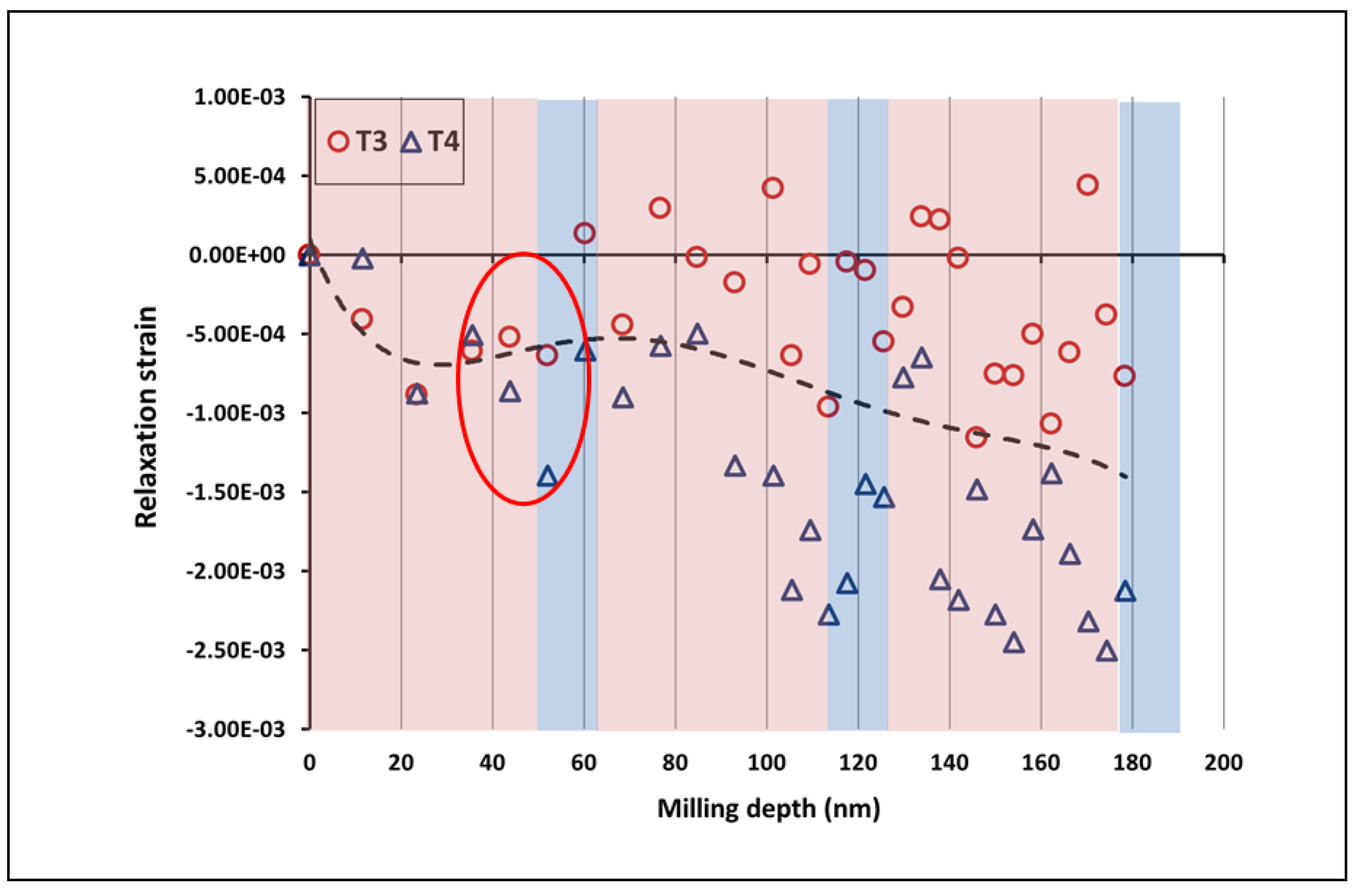

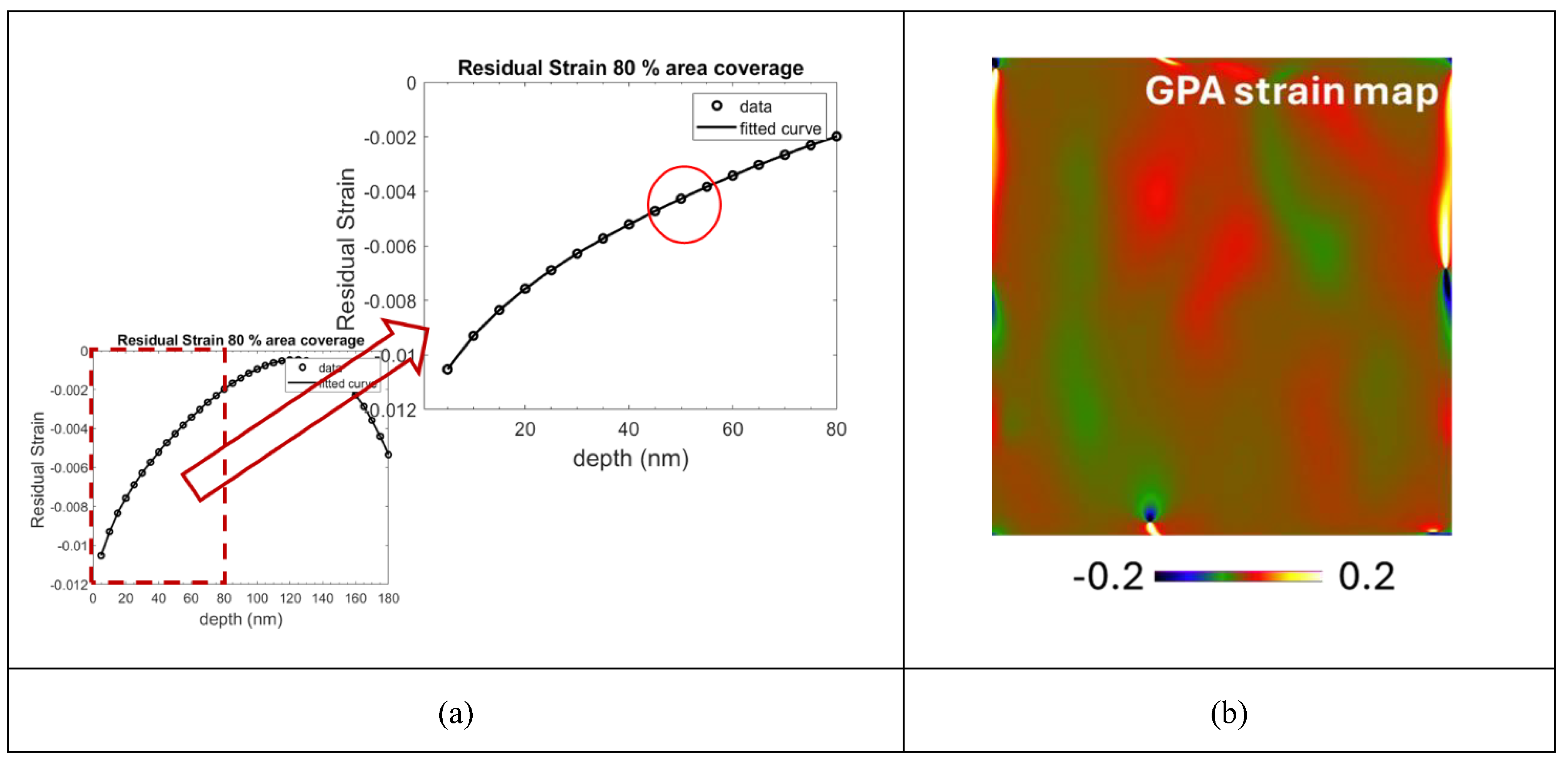

FIB-DIC ring-core residual stress measurement, the relaxation strains are evaluated from DIC analysis of SEM images obtained after each milling step. The plot is drawn between relaxation strain values and milling depth at each milling step (

Figure 6). The relaxation strain curves are evaluated by DIC analysis and residual strain profiles were calculated by RISE toolbox. The sampling region of interest for the case of TEM-GPA method is highlighted in red circles in both relaxation strain and residual strain profiles, respectively.

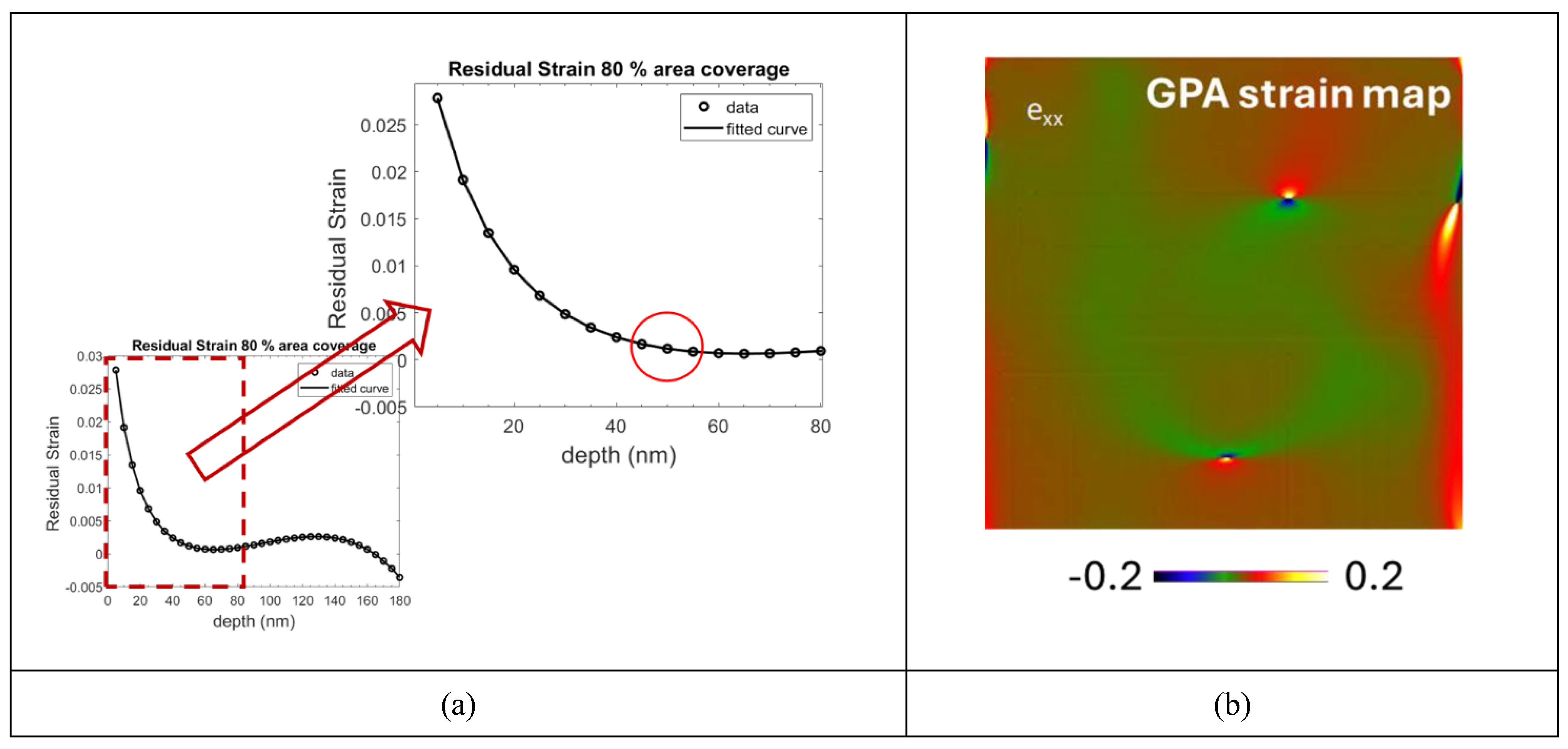

A comparison between the residual strain calculated by the RISE toolbox and TEM-GPA method is presented in

Figure 7. The residual strain calculated by the FIB-DIC method in the GPA inspected region is 7.64E-4 which is slightly different from -3.39E-3 evaluated by the GPA method. The difference between these values is very minimal, however this might have occurred because of the dislocations in that GPA map (

Figure 8b).

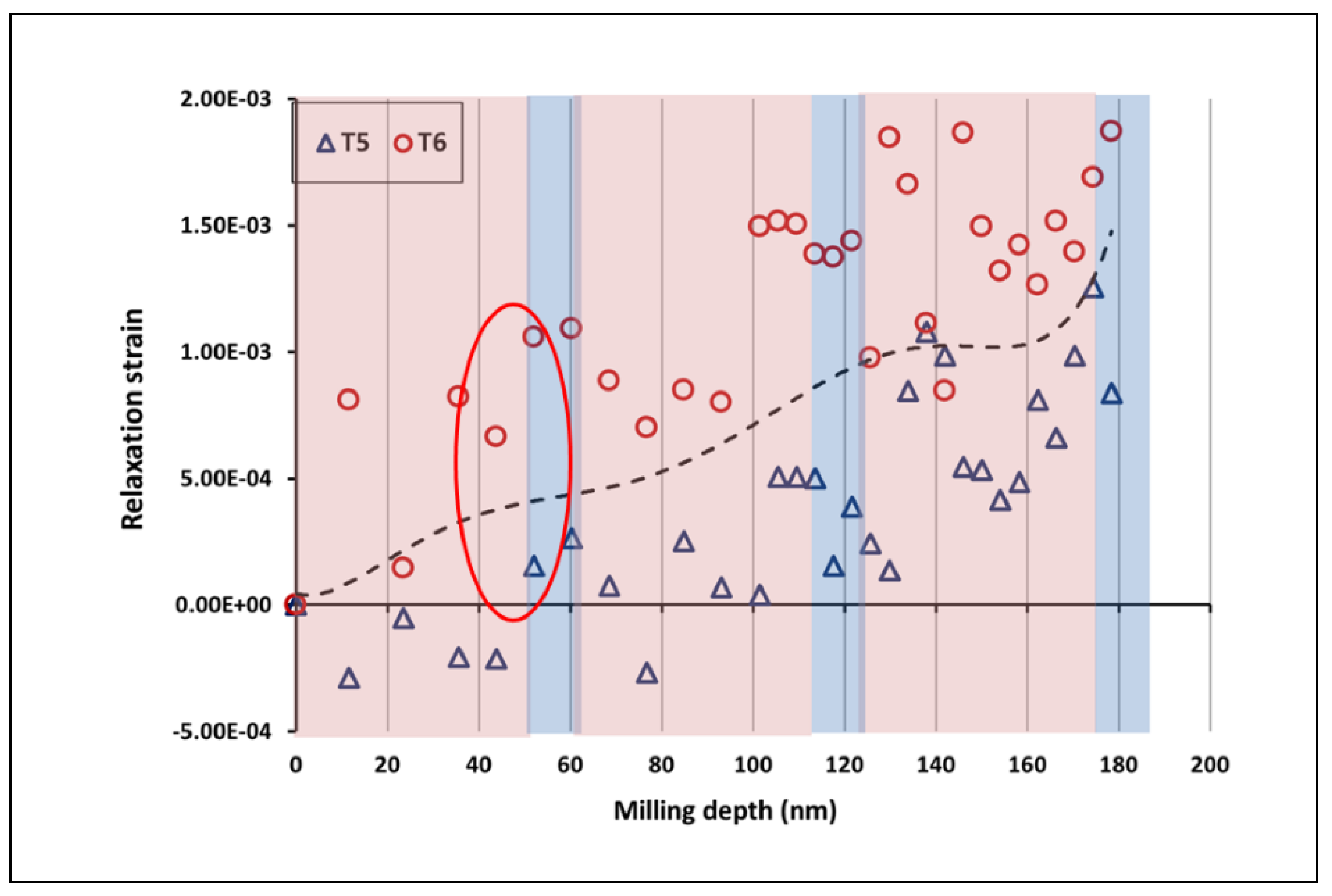

In the case of Sample B, there is a very promising match between the residual strain values obtained by both techniques, FIB-DIC and TEM-GPA, respectively. The relaxation strain curves are presented in

Figure 8, which shows positive relaxation strain values that correspond to the presence of compressive residual stresses within the coating thicknesses. The red encircled areas on all the strain profiles are the interfacial sampling region for GPA method.

The residual strain values calculated by FIB-DIC and TEM-GPA methods are presented in

Figure 9, which shows a strong validation and profound accuracy between both high-spatial resolution techniques.

4. Discussion

The structural properties of MOVPE grown AlGaN/GaN multilayer coatings have been investigated by high resolution x-ray diffraction (HRXRD) and reciprocal space maps (RSMs) techniques. The two sets of coatings, 4-fold alternative sublayer geometry (AlGaN/GaN), different sublayer thickness with 1.7µm GaN buffer layer deposited on the sapphire substrate by MOVPE method. The sublayers thicknesses and total thickness were measured by FIB cross-section, the sample-A and sample-B have a total thickness of 296 nm and 276 nm, respectively. The residual strain values at the interfacial regions between the first layers within the heterogeneous multilayer coatings are calculated by using two advanced techniques with different spatial resolution (from sub-micron to sub-nano scale), HRSTEM-GPA and FIB-DIC, respectively.

The epitaxial growth of these coatings is confirmed by HRXRD and RSMs techniques, which makes them suitable for the TEM-GPA analysis. HRXRD scans with the reflection of 00.2 were performed, and asymmetrical 11.4 RSM maps were obtained to determine the thicknesses, composition, relaxation and crystal quality of the subsequently grown layers. The structural data were analyzed by means of curves fitting to the 2theta/omega scan of 00.2 reflection preceded by analysis of reciprocal space maps around the 11.4 lattice point which confirm its epitaxial growth (Feng et al., 2019; Mudie et al., 2003).

Comparison between these two techniques

In the case of sample B: Al0.22Ga0.78N/GaN coatings, there are similar residual strain values are obtained from both techniques (FIB-DIC and TEM-GPA; -4.27E-3 and -4.54E-3), negative strain values corresponding to the presence of tensile stresses within the coatings structure. Both high-spatial resolution techniques provide strong validation and accurate results for the same region of interest within the coatings thicknesses.

For the Al0.48Ga0.52N/GaN coatings (sample-A), the negative residual strain value of -3.39E-03 obtained by TEM-GPA method which represents the tensile residual stresses, while FIB-DIC method provides slightly different residual strain of 7.68E-04, positive value which corresponds to the presence of very little compressive stresses within the interfacial coatings layer thicknesses and considered to be close to zero. The strain values for sample A are still comparable to some extent as the difference is quite small. The change in the calculated values might be due to the presence of dislocations in the GPA maps and exhibiting the different spatial resolution. The main reason other than having difference in spatial resolution, could be annealing of the samples before GPA method as compared to the FIB-DIC there is no annealing needed before the experiment.

Effect of dislocation:

The presence of dislocations strongly influences the residual strains within the multilayer coatings. The dislocations can act as stress-relief mechanisms in coatings as the lattice mismatch between the adjacent layers generate excessive strain dislocations from the interfaces to partially relieve this strain. The introduction of dislocations reduces the residual strain but can lead to localized distortions near the interfaces. This redistribution of strain depends on the density and type of dislocation (e.g., edge or screw dislocations). The network of misfit dislocation may develop at the interfaces within multilayers because of significant lattice mismatches. These dislocations accommodate the mismatch and minimize the buildup of elastic strain energy.

Such networks can stabilize the structure by reducing overall strain energy, but they may also introduce localized stress concentrations that could lead to failure under mechanical or thermal loading. The dislocations in multilayer thin coatings can either relieve or redistribute residual strain, depending on factors such as the lattice mismatch, layer thickness, temperature, and material properties. While they generally help in strain relaxation, they can also introduce localized stresses that may affect the mechanical integrity and durability of the coating system.

Both are high-spatial resolution techniques ranging from sub-micro (FIB-DIC) to sub-nano scale (HRSTEM-GPA). The combination of these techniques provides us with the more validated, trusted and accurate results regarding the residual strain at the interfacial layers within the complex and heterogeneous coatings. The TEM-GPA method is restricted to presence of polycrystallinity and cannot be analyzed by highly stressed multilayer coatings while the FIB-DIC method can be applied to a wide range of materials irrespective of the crystal structures and stress state. The difference between the samples may not be significant given the small sampling size associated with STEM analysis.

5. Conclusions

Heterogenous multilayer AlGaN/GaN coatings with GaN buffer layer were successfully grown on C-plane oriented-sapphire substrate via MOVPE. Two different sets of AlGaN/GaN multilayer coatings with different layer thickness were investigated. The structural properties and layer thicknesses of the as-grown coatings were evaluated by HRXRD and RSMs techniques that show epitaxially grown coatings well suited for HRTEM-GPA analysis. The residual strain values were calculated by two different high-spatially resolved techniques with the resolution ranging from sub-micron to sub-nano level, FIB-DIC and HRSTEM-GA.

A critical comparison was made between the residual strain obtained by two different techniques on the AlGaN/GaN multilayer coatings. Both techniques show consistent results, negative residual strain (-4.5E-3) that represents the presence of tensile residual stresses, for sample B with no dislocation on the GPA map. The sampling area of interest (AOI) was selected at the interfaces of the first two layers (encircled in red on the strain curves).

The influence of dislocation is quite evident in the case of sample B exhibiting the two dislocations on the GPA map, for that reason, the residual strain calculated by HRSTEM-GPA method is -3.39E-3 while the FIB-DIC method shows strain value of 7.5E-4. The reason for the change in results is because of the presence of dislocation on the selected AOI which can be avoided for the similar results as for the sample B with no dislocation.

The combination of these two high-resolution techniques provides the validated residual stress values with high precision calculated at sub-micron to sub-nano level. This comparative study on residual stress measurement can help the scientific community to choose coating synthesis techniques and deposition parameters to produce efficient coatings with high structural durability depending on their applications. Further studies can be conducted in different nanostructured multilayer coatings that undergo different annealing treatments and application of these developed comparisons on the wide spectrum of industrial use cases.

CRediT author statement

Saqib Rashid: Conceptualization (Equal), Data Curation (Lead), Formal Analysis (Lead), Investigation (Lead), Methodology (Lead), Visualization (Equal), Writing – Original Draft (Lead), Writing – Review & Editing (Equal) Edoardo Rossi: Data Curation (Supporting), Investigation (Supporting), Validation (Supporting), Visualization (Equal), Writing – Review & Editing (Equal); Marco Sebastiani: Conceptualization (Lead), Funding Acquisition (Lead), Methodology (Equal), Supervision (Lead), Validation (Supporting), Writing – Original Draft (Equal), Writing – Review & Editing (Supporting); Spyros Diplas: Data Curation (Supporting), Investigation (Equal), Writing – Original Draft (Supporting); Patricia Almeida Carvalho: Data Curation (Supporting), Investigation (Equal), Writing – Original Draft (Supporting); Damian Pucicki: Resources (Lead), Writing – Original Draft (Supporting); Rafal Kuna: Resources (Lead), Writing – Original Draft (Supporting).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the EU H2020 Project “Harmonisation of EU-wide nanomechanics protocols and relevant data exchange procedures, across representative cases; standardization, interoperability, data workflow” (NanoMECommons) under Grant Agreement No. 952869.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Bartoli, F., Aubert, T., Moutaouekkil, M., Streque, J., Pigeat, P., Zhgoon, S., Talbi, A., Hage-Ali, S., M’Jahed, H., & Elmazria, O. (2018). AlN/GaN/Sapphire heterostructure for high-temperature packageless acoustic wave devices. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 283, 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Bemporad, E., Brisotto, M., Depero, L. E., Gelfi, M., Korsunsky, A. M., Lunt, A. J. G., & Sebastiani, M. (2014). A critical comparison between XRD and FIB residual stress measurement techniques in thin films. Thin Solid Films, 572, 224–231. [CrossRef]

- Bobzin, K., Wietheger, W., Knoch, M. A., Schacht, A., Reisgen, U., Sharma, R., & Oster, L. (2020). Comparison of Residual Stress Measurements Conducted by X-ray Stress Analysis and Incremental Hole Drilling Method. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology, 29(6), 1218–1228. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. Y.-F., Chou, Y.-C., Wang, Z.-Y., Lin, W.-Y., & Lin, M.-T. (2020). Using Digital Image Correlation on SEM Images of Strain Field after Ion Beam Milling for the Residual Stress Measurement of Thin Films. Materials, 13(6), 1291. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., Saravade, V., Chung, T.-F., Dong, Y., Zhou, H., Kucukgok, B., Ferguson, I. T., & Lu, N. (2019). Strain-stress study of AlxGa1−xN/AlN heterostructures on c-plane sapphire and related optical properties. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 10172. [CrossRef]

- Galindo, P. L., Kret, S., Sanchez, A. M., Laval, J.-Y., Yáñez, A., Pizarro, J., Guerrero, E., Ben, T., & Molina, S. I. (2007). The Peak Pairs algorithm for strain mapping from HRTEM images. Ultramicroscopy, 107(12), 1186–1193. [CrossRef]

- Genzel, C., & Reimers, W. (2022). Depth-resolved X-ray residual stress analysis in PVD (Ti, Cr) N hard coatings. International Journal of Materials Research, 94(6), 655–661. [CrossRef]

- GUO, J., FU, H., PAN, B., & KANG, R. (2021). Recent progress of residual stress measurement methods: A review. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics, 34(2), 54–78. [CrossRef]

- Huff, M. (2022). Review Paper: Residual Stresses in Deposited Thin-Film Material Layers for Micro- and Nano-Systems Manufacturing. Micromachines, 13(12), 2084. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.-I., Kim, G., Kim, Y.-I., Park, J.-H., Choi, M. Y., & Kim, K.-B. (2021). Experimental Measurement of Residual Stress Distribution in Rail Specimens Using Ultrasonic LCR Waves. Applied Sciences, 11(19), 9306. [CrossRef]

- Hÿtch, M. J., Putaux, J.-L., & Pénisson, J.-M. (2003). Measurement of the displacement field of dislocations to 0.03 Å by electron microscopy. Nature, 423(6937), 270–273. [CrossRef]

- Hÿtch, M. J., Putaux, J.-L., & Thibault, J. (2006). Stress and strain around grain-boundary dislocations measured by high-resolution electron microscopy. Philosophical Magazine, 86(29–31), 4641–4656. [CrossRef]

- Hÿtch, M. J., Snoeck, E., & Kilaas, R. (1998). Quantitative measurement of displacement and strain fields from HREM micrographs. Ultramicroscopy, 74(3), 131–146. [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, A. M., Salvati, E., Lunt, A. G. J., Sui, T., Mughal, M. Z., Daniel, R., Keckes, J., Bemporad, E., & Sebastiani, M. (2018). Nanoscale residual stress depth profiling by Focused Ion Beam milling and eigenstrain analysis. Materials & Design, 145, 55–64. [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, A. M., Sebastiani, M., & Bemporad, E. (2009). Focused ion beam ring drilling for residual stress evaluation. Materials Letters, 63(22), 1961–1963. [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, A. M., Sebastiani, M., & Bemporad, E. (2010). Residual stress evaluation at the micrometer scale: Analysis of thin coatings by FIB milling and digital image correlation. Surface and Coatings Technology, 205(7), 2393–2403. [CrossRef]

- Lord, J., Cox, D., Ratzke, A., Sebastiani, M., Korsunsky, A., Salvati, E., Mughal, M. Z., & Bemporad, E. (2018). A good practice guide for measuring residual stresses using FIB-DIC.

- Lunt, A. J., Baimpas, N., Salvati, E., Dolbnya, I. P., Sui, T., Ying, S., Zhang, H., Kleppe, A. K., Dluhoš, J., & Korsunsky, A. M. (2015). A state-of-the-art review of micron-scale spatially resolved residual stress analysis by FIB-DIC ring-core milling and other techniques. The Journal of Strain Analysis for Engineering Design, 50(7), 426–444. [CrossRef]

- MATLAB Central. Digital Image Correlation and Tracking. (2016, July 2). MATLAB Central. Digital Image Correlation and Tracking. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/ matlabcentral/fileexchange/50994-digital-image-correlation-and-tracking.

- Miyoshi, M., Ishikawa, H., Egawa, T., Asai, K., Mouri, M., Shibata, T., Tanaka, M., & Oda, O. (2004). High-electron-mobility AlGaN∕AlN∕GaN heterostructures grown on 100-mm-diam epitaxial AlN/sapphire templates by metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy. Applied Physics Letters, 85(10), 1710–1712. [CrossRef]

- M.J. Hÿtch. (1997). GEOMETRIC PHASE ANALYSIS OF HIGH RESOLUTION ELECTRON MICROSCOPE IMAGES. Scanning Microscopy, 11, 53–66. Available online: https://www.ecmjournal.org/smi/pdf/smi97-05.pdf.

- Mudie, S., Pavlov, K., Morgan, M., Tabuchi, M., Takeda, Y., & Hester, J. (2003). High-Resolution X-Ray Diffractometry Investigation of Interface Layers in GaN/AlN Structures Grown on Sapphire Substrates. Surface Review and Letters, 10(02n03), 513–517. [CrossRef]

- Nervi, S., & Szabó, B. A. (2007). On the estimation of residual stresses by the crack compliance method. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 196(37–40), 3577–3584. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., Zhao, J., Chen, L., & Dong, J. (2021). Residual stress measurement combining blind-hole drilling and digital image correlation approach. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 176, 106346. [CrossRef]

- Quillin, K., Yeom, H., Pu, X., Frazer, D., Sasidhar, K. N., & Sridharan, K. (2023). Effects of elevated temperature exposure on the residual stress state and microstructure of PVD Cr coatings on SiC investigated via in situ X-ray diffraction and transmission electron microscopy. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 879, 145273. [CrossRef]

- Salvati, E., Romano-Brandt, L., Mughal, M. Z., Sebastiani, M., & Korsunsky, A. M. (2019). Generalised residual stress depth profiling at the nanoscale using focused ion beam milling. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 125, 488–501. [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, M., Eberl, C., Bemporad, E., Korsunsky, A. M., Nix, W. D., & Carassiti, F. (2014). Focused ion beam four-slot milling for Poisson’s ratio and residual stress evaluation at the micron scale. Surface and Coatings Technology, 251, 151–161. [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, M., Eberl, C., Bemporad, E., & Pharr, G. M. (2011). Depth-resolved residual stress analysis of thin coatings by a new FIB–DIC method. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 528(27), 7901–7908. [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, M., Rossi, E., Zeeshan Mughal, M., Benedetto, A., Jacquet, P., Salvati, E., & Korsunsky, A. M. (2020). Nano-Scale Residual Stress Profiling in Thin Multilayer Films with Non-Equibiaxial Stress State. Nanomaterials, 10(5), 853. [CrossRef]

- Ye, C., & Jiang, P. (2020). Accurate residual stress measurement as a function of depth in environmental barrier coatings via a combination of X-ray diffraction and Raman spectroscopy. Ceramics International, 46(8), 12613–12617. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J., Zhou, B., Li, L., Liu, Y., Guo, W., Talwar, D. N., He, K., Ferguson, I. T., Wan, L., & Feng, Z. C. (2021). Optical and structural properties of AlN thin films deposited on different faces of sapphire substrates. Semiconductor Science and Technology, 36(4), 045012. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.-Y., Nguyen, T. A. K., Dang, N. M., Wu, X.-W., Chen, T. Y.-F., & Lin, M.-T. (2024). FIB-DIC ring-core measurement of the residual stress on HiPIMS W/Cu and Cr/Cu multilayer thin films. Surface and Coatings Technology, 483, 130768. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y., Liu, C., Kong, X., & Lin, Z. (2017). Experiment and numerical simulation for laser ultrasonic measurement of residual stress. Ultrasonics, 73, 271–276. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. P., Wang, H. M., Gaevski, M. E., Chen, C. Q., Fareed, Q., Yang, J. W., Simin, G., & Khan, M. A. (2002). Crack-free thick AlGaN grown on sapphire using AlN/AlGaN superlattices for strain management. Applied Physics Letters, 80(19), 3542–3544. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Xiao, X., Qi, H., Huang, Y., & Qin, H. (2022). Quantitative and nondestructive determination of residual stress for SiO 2 thin film by laser-generated surface acoustic wave technique. Measurement Science and Technology, 33(4), 045601. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).