1. Introduction

Myocarditis in dogs is linked to severe consequences, such as fatality or lasting damage to the heart. Regrettably, the precise cause is frequently unidentified. However, systemic viral infections or bacterial agents are frequently associated [

1,

2]. Canine parvovirus (CPV) is widely recognized as a leading cause of myocarditis in young puppies. Nevertheless, many veterinarians believe that the extensive use of vaccines has significantly reduced the occurrence of parvovirus (PV) myocarditis in dogs [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Diseases caused by Parvoviridae, of which CPV is a member, are of critical importance in the field of veterinary medicine. This family consists of icosahedral, non-enveloped, small (23–26 nm) viruses with linear, single-stranded DNA genomes.

CPV-2 is a highly pathogenic virus for canids, causing almost 100% illness and up to 10% death in uninfected adults, and 91% death in puppies [

8]. Puppies infected between 6 weeks and six months of age may experience acute hemorrhagic enteritis, panleukopenia, and lymphoid necrosis as pathological consequences. Early in the CPV outbreak, myocarditis was also detected in weanling puppies [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Puppies born to mothers without prior exposure to the CPV-2 are vulnerable to infection of heart muscle cells and subsequent development of necrotizing myocarditis, which can be fatal. This susceptibility occurs when the puppies are infected within two weeks after birth or, less typically, during the late stages of pregnancy [

15]. Myocardial infection often leads to heart failure or sudden death in infants between 3 and 4 weeks old. Neonatal puppies that were experimentally infected with CPV-2 showed a step-by-step process of heart muscle cell death and loss, followed by inflammation and the formation of scar tissue. This process happened simultaneously with the disappearance of viral structures and substances [

16]. Death related to progressive cardiac injury and heart failure may be delayed several months after infection with variable lymphocytic myocarditis and interstitial or replacement fibrosis observed in older puppies (7–15 weeks) surviving acute infection [

12,

15].

CPV-2 infection commonly leads to myocarditis in young dogs, resulting in further myocardial destruction, inflammation, and replacement fibrosis [

1,

17]. Although our study did identify myocardial viral nucleic acid by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in puppies with dilated cardiomyopathy or myocarditis, we evaluated the hypothesis that myocardial CPV-2 infection is underrecognized and is associated with cardiac damage in dogs less than one-year-old [

1].

2. Materials and Methods

This case report details the sudden death of 27 puppies who were brought to the Laboratory of Pathological Anatomy at the University Veterinary Clinics, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Timisoara. These puppies had a suspected history of parvovirus exposure during the prenatal period. Performing diagnostic assessment involves conducting a pathologic evaluation of deceased puppies, specifically evaluating their heart tissue for CPV-2 using PCR.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue from the Laboratory of Pathological Anatomy within the University Veterinary Clinics, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Timisoara, archives were used to evaluate the prevalence of CPV-2 in puppies with myocarditis and/or myocardial fibrosis. An investigation was conducted on 27 archived cases from May 2019 to December 2021. The purpose was to identify puppies, regardless of breed or sex, that were one year old or younger and had been diagnosed with conditions such as "myocardial fibrosis," "myocarditis," "cardiac fibrosis," "chronic myocarditis," "fibrosing cardiomyopathy," "cardiac failure," "restrictive cardiomyopathy," or "end-stage heart." The histopathology was assessed by a veterinary pathologist (A.S.) who was unaware of the illness status. Heart tissue samples were collected and tested by PCR for each 27 of the puppies.

The cardiac tissue samples undergo processing to extract DNA, and the presence of the viral genome is often evaluated by a PCR-based assay utilizing primers that target specific sections of the viral genome [

18]. Accurately detecting a viral genome relies on the quantity of the initial tissue sample, the quality of the extracted DNA, and the successful PCR amplification. A viral infection can lead to acute heart inflammation, often associated with a significant viral load. This viral load can be easily measured using a PCR reaction. However, in the case of a prolonged viral infection with a lower overall viral load, it may be necessary to do numerous iterations of DNA extraction to detect viral genomes reliably.

The QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) was used to extract nucleic acid from 10-mm-thick FFPE tissue sections. The PCR procedure included RPS19 primers for the housekeeping gene and VP1 to VP2 primers for the parvoviral genes [

1,

19,

20]. The practical detection limit was determined to be 10 copies by performing a serial dilution of a quantified CPV-2 VP2 amplicon produced using the CPV-940F and PV-1617R primers, which include the sequences CGTGG TGTAACTCAAATGGGAAA and GGATTCCA AGTATGAGAGGCTCTT, respectively. For every PCR experiment, both negative and positive controls were utilized. The negative control involved a "no-template" response, while the positive control consisted of canine intestinal tissue infected with CPV-2 (verified through viral isolation).

3. Results

3.1. PCR

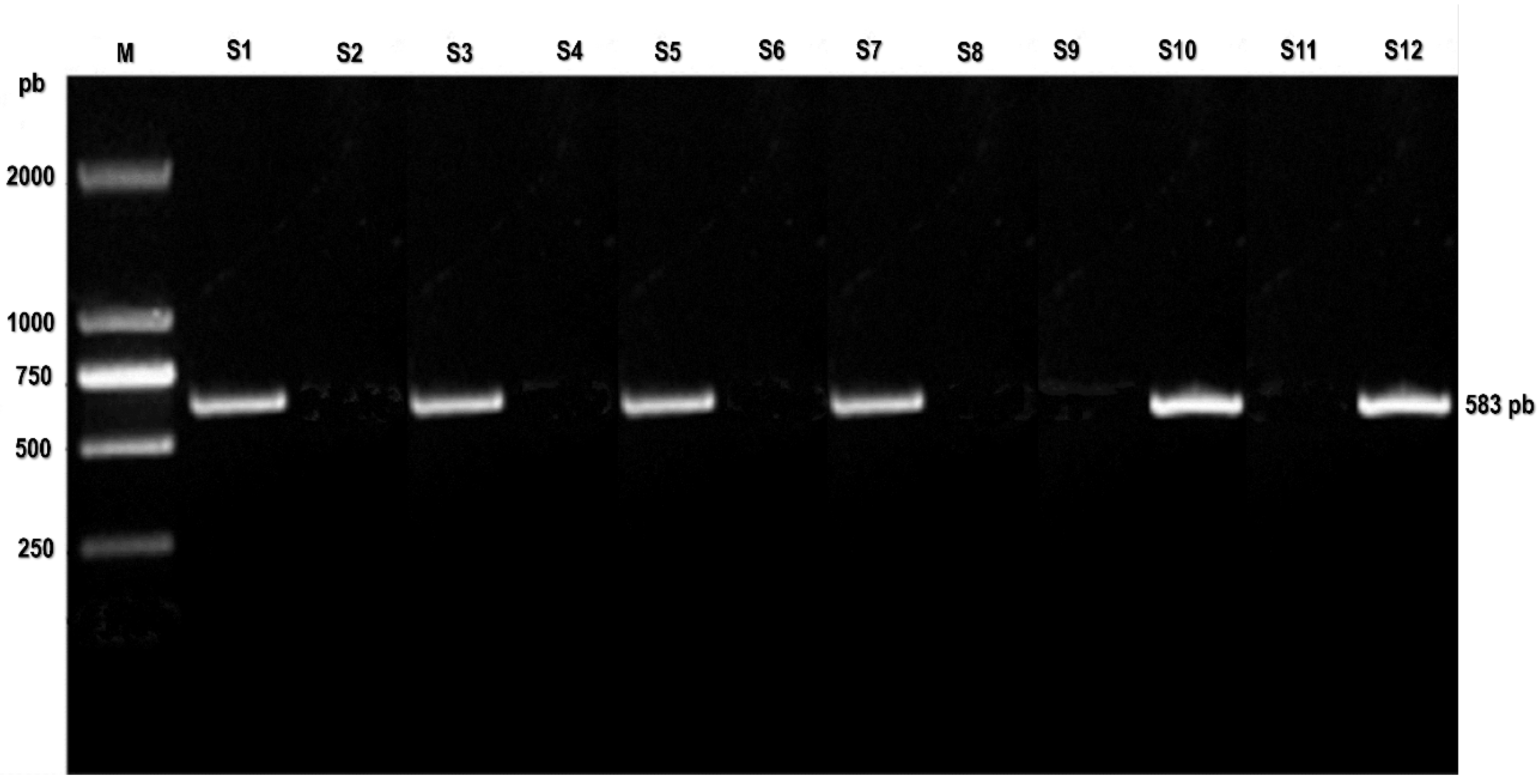

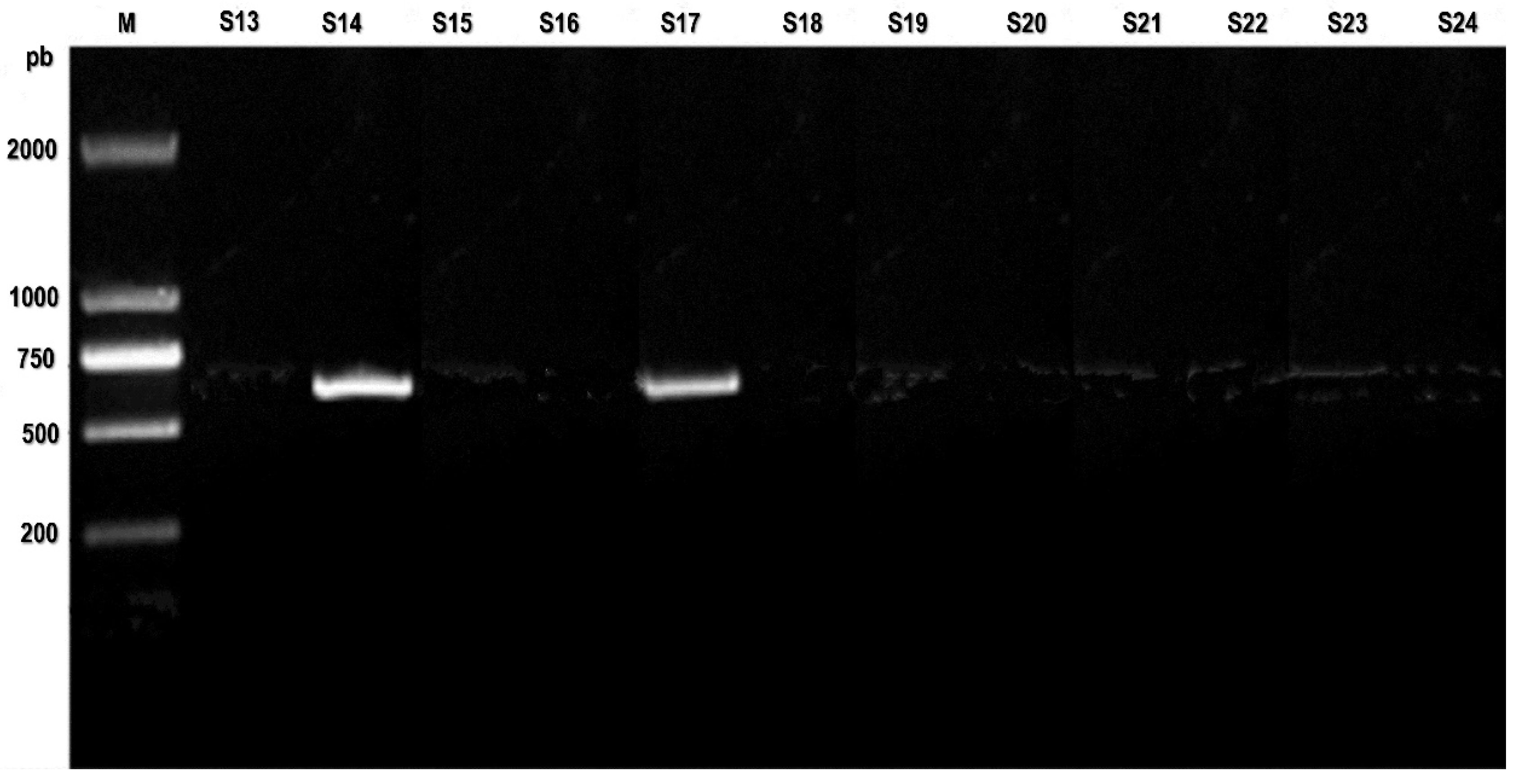

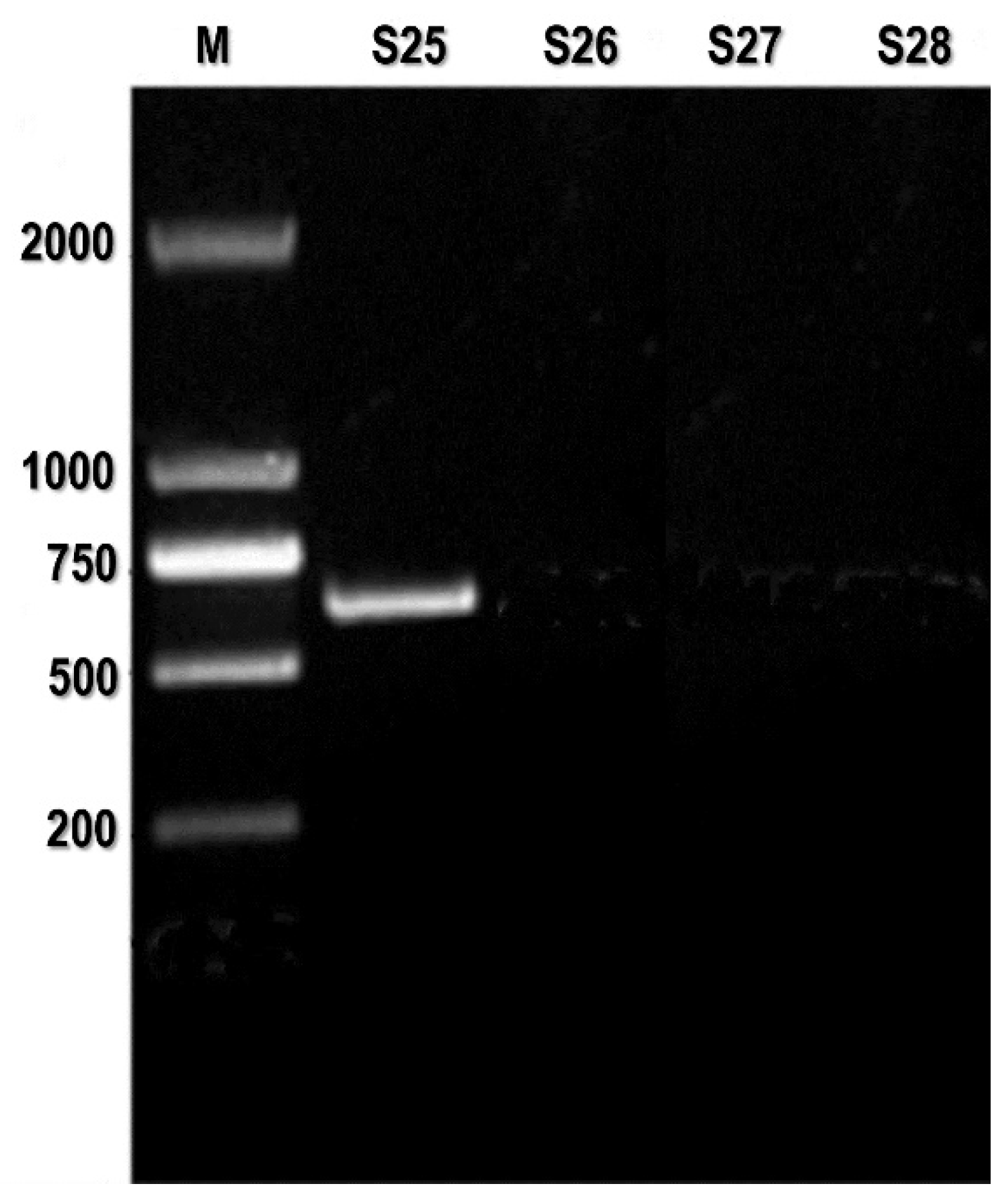

Conventional (PCR) utilizing VP1/VP2 PV primers successfully amplified the anticipated 583 base pair result in 9 out of the 27 cases (

Figure S1,

Figure S2, and

Figure S3).

Figure S1.

PCR assay: PCR detects CPV-2 in heart tissue samples. M: DL2000 DNA marker; S1 positive control; S2-S12 heart tissue samples.

Figure S1.

PCR assay: PCR detects CPV-2 in heart tissue samples. M: DL2000 DNA marker; S1 positive control; S2-S12 heart tissue samples.

Figure S2.

PCR assay: PCR detects CPV-2 in heart tissue samples. M: DL2000 DNA marker; S13-S24 heart tissue samples.

Figure S2.

PCR assay: PCR detects CPV-2 in heart tissue samples. M: DL2000 DNA marker; S13-S24 heart tissue samples.

Figure S3.

PCR assay: PCR detects CPV-2 in heart tissue samples. M: DL2000 DNA marker; S25-S27 heart tissue samples; S28 negative control.

Figure S3.

PCR assay: PCR detects CPV-2 in heart tissue samples. M: DL2000 DNA marker; S25-S27 heart tissue samples; S28 negative control.

Amplification of CPV-2 sequences was either performed directly from heart tissues or after amplification; the amplicons were submitted to nucleotide sequencing. All analyzed samples were positive for VP2 sequences, yielding 583bp products, which were purified and submitted to nucleotide sequencing. The nucleotide sequencing revealed an overall high amino acid identity (in general, 100%) with CPV-2c and lower identities with CPV2a (until 98.8%) and CPV2b (until 99.4%). The analysis of amino acid sequences of the VP2 segment revealed that 9 samples presented a glutamic acid at residue 426. According to previous studies [

1], the glutamic acid at position 426 represents a signature of variants belonging to the CPV-2c genotype.

3.2. Histopathologic Findings

The postmortem test conducted at the Laboratory of Pathological Anatomy within the University Veterinary Clinics, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Timisoara, found that the 27 puppies had enlarged hearts with several patches of pale myocardium in both the left and right ventricles. The cut surfaces of the left and right ventricular free walls likewise had a pale appearance. The thickness of the left ventricular free wall was 6 mm. The thickness of the right ventricular free wall was 3.6 mm. The heart constituted 1.33% of the total body weight, within the predicted range of 0.7% to 0.8% in adult and newborn dogs. [

21]. The thoracic and abdominal cavities contained approximately 7 milliliters of serosanguinous fluid.

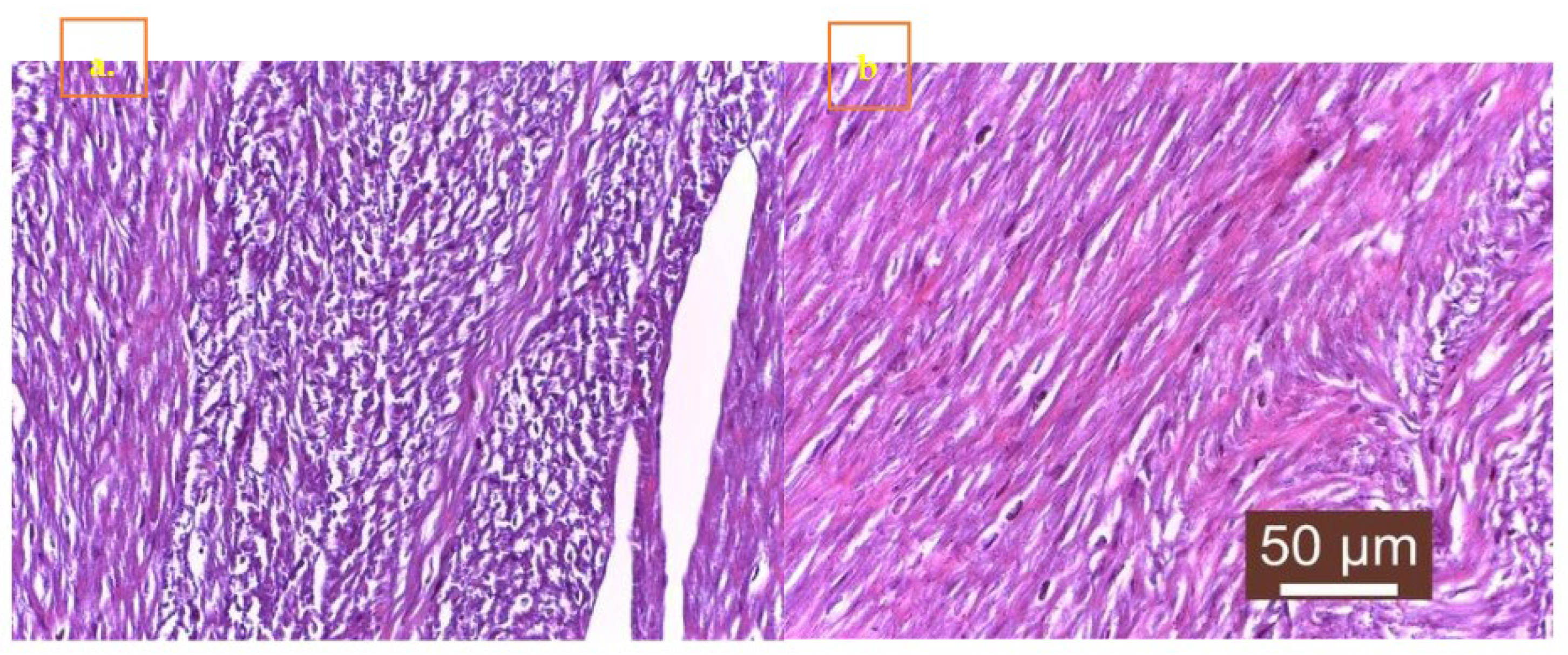

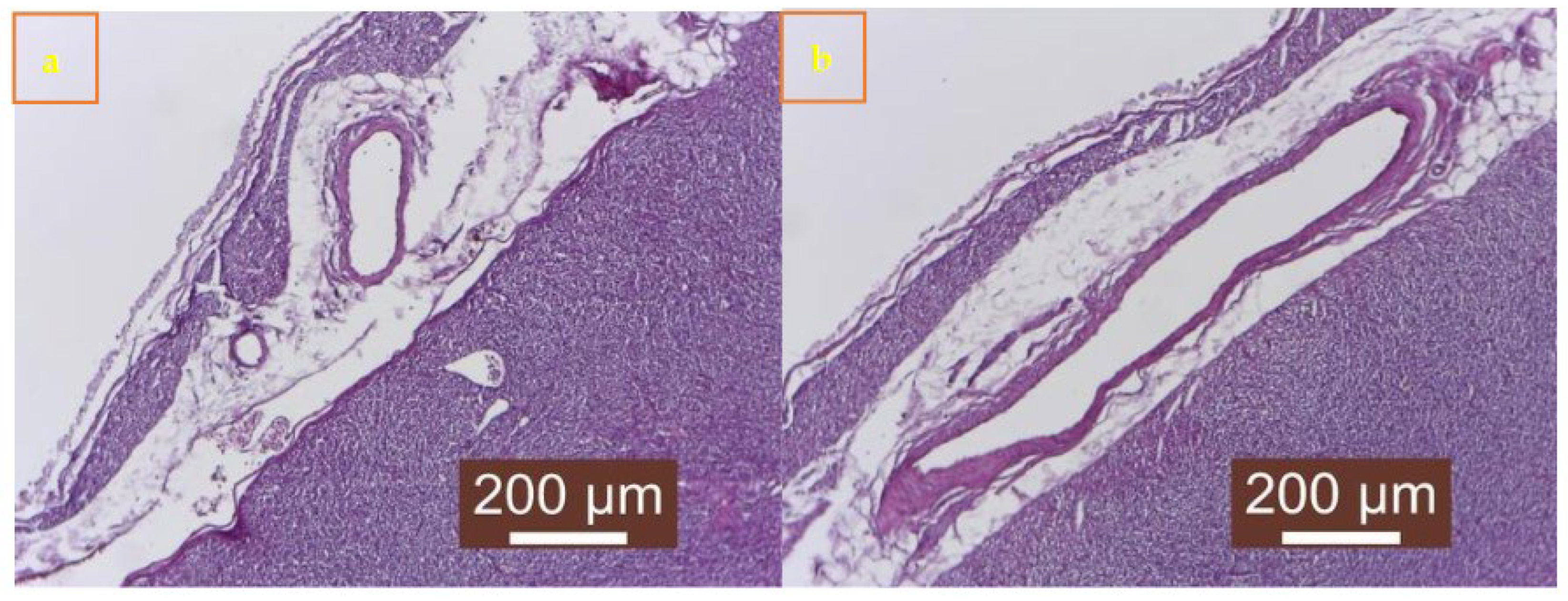

Of the 27 cases, 19 showed signs of cardiomyocyte necrosis, all 27 showed inflammation, and 14 displayed myocardial fibrosis. The inflammatory infiltrates comprised macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils (

Figure 4S b and

Figure 5S a and b). Out of the 27 cases, 11 (40.74%) exhibited a combination of necrosis, inflammation, and fibrosis (

Figure 4S a). Additionally, 5 cases (18.51%) mostly showed necrosis, whereas 3 cases (11.12%) predominantly displayed fibrosis (Table S2 and S3). No parvoviral intranuclear inclusions were detected.

The occurrence of cardiomyocyte necrosis, myocarditis, and myocardial fibrosis was compared between the 9 instances positive for CPV and the 18 cases negative for CPV. Cardiomyocyte necrosis occurred less frequently in instances that tested positive for CPV compared to cases that tested negative for CPV (5 out of 9 cases; 55.56% vs. 14 out of 18 cases; 77.78%; P = .003, Fisher exact test). The prevalence of myocardial inflammation was similar across CPV-positive and CPV-negative cases, with 66.67% (6/9) and 83.84% (15/18) respectively. Similarly, the prevalence of myocardial fibrosis was 55.56% (5/9) in CPV-positive cases and 50% (9/18) in CPV-negative cases. Out of the four patients that tested positive for CPV, two (22.23%) showed a major lesion of cardiomyocyte necrosis, one (11.12%) showed neutrophilic-histiocytic myocarditis, and one case (11.12%) showed lymphohistiocytic myocarditis. Out of the 18 cases where CPV could not be detected, the most common kind of damage was necrosis of the heart muscle cells in 8 cases (44.45%), followed by myocarditis in 7 cases (38.4%), fibrosis in 2 cases (7%), and a combination of different patterns in 5 cases (18%).

Out of the instances tested positive for CPV (58%), seven exhibited a combination of necrosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. On the other hand, out of the cases without detectable CPV (39%), 11 showed the same combination of necrosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Myocardial perivasculitis/vasculitis (4/28) and myocardial inflammation characterized by abundant neutrophils and/or macrophages (7/28) were histological characteristics only observed when CPV was undetectable.

The lungs, liver, and heart had notable histologic abnormalities that are frequently observed in cases of heart failure. The lungs exhibited a modest level of alveolar histiocytosis. The liver exhibited slight centrilobular congestion and considerable hepatic vacuolar alteration of the lipid type. The heart had pronounced, persistent, scattered, and regionally widespread degeneration and replacement of myofibers with fibrous connective tissue. The myocardium was invaded by a small to moderate amount of lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory cells. The cardiac ventricular wall portion that showed pallor tested significantly positive for CPV-2 on PCR analysis. Nevertheless, there were no observable histologic alterations in the intestines. The necropsy findings confirmed that the cause of death for the puppies in our investigation was CPV infection.

4. Discussions

CPV-2 is a highly harmful virus for canids, causing almost 100% illness and up to 10% death in uninfected adult animals. In puppies, the mortality rate can reach 91% [

8,

15]. Puppies born to mothers who have not been previously exposed to the illness are at risk of developing necrotizing myocarditis, a condition characterized by the infection of heart muscle cells and subsequent tissue death. This infection is most likely to occur within two weeks after birth or, less typically, during the late stages of pregnancy [

1,

22]. Myocardial infection often leads to heart failure or sudden death in infants between 3 and 4 weeks old. Neonatal puppies that were intentionally infected with CPV-2 showed a step-by-step process of heart muscle cell death and loss, followed by inflammation and the formation of fibrous tissue. This process happens simultaneously with the disappearance of viral particles and substances that trigger an immune response [

23]. Death resulting from progressive cardiac damage and heart failure may occur several months after infection with varied lymphocytic myocarditis and interstitial or replacement fibrosis, which are commonly seen in older puppies aged 7 to 15 weeks. Enduring an acute infection [

1,

2,

24].

CPV-2 infection is a common cause of myocarditis and consequent myocardial injury, inflammation, and replacement fibrosis in young dogs [

1,

22]. Despite a previous study's failure to detect viral genetic material in the heart muscle of adult dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy or myocarditis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), we aimed to investigate the possibility that canine parvovirus type 2 (CPV-2) infection in the heart muscle is not being adequately recognized and may be linked to cardiac injury in dogs younger than 2 years old [

1].

Unsurprisingly, most of our cases with myocardial CPV-2 DNA displayed lesions in line with CPV-2 myocarditis. Furthermore, we detected parvoviral indicators in the heart muscle cells of dogs with CPV-2 enteritis who had not previously been diagnosed with a myocardial infection. Typically, simultaneous occurrences of intestinal and cardiac diseases are not commonly observed in animals or litters that are infected spontaneously or in laboratory experiments. However, it has been found that viruses obtained from myocardial tissues can induce enteritis when tested in experiments [

9,

25,

26]. Our research suggests that subclinical myocardial CPV-2 infection, as compared to enteric disease, may harm the myocardium and play a role in the development of cardiac disease.

The age of dogs who tested positive for CPV-2 in our study indicates a broader period of vulnerability to cardiac complications caused by CPV-2. Parvoviruses rely on the cellular processes of actively dividing cells in the S-phase for their replication. Therefore, the vulnerability of the heart to CPV infection may be linked to the initially high rate of DNA synthesis in cardiomyocytes of newborn animals, followed by a decrease as they age [

1,

2,

26]. Viral VP2 mRNA was highest in younger dogs, specifically those aged between 21 and 56 days. However, there was a significant presence of viral mRNA in the hearts of specific older puppies, with the ISH signal being found in the exact location of the heart muscle cells in dogs up to 84 days old. Research on the development of the heart muscle in dogs has indicated that factors that promote the replication of CPV-2 are present from birth until the puppies stop nursing. Nevertheless, there is significant variation in the growth patterns of various dog breeds, influenced by characteristics such as breed type and other variables. These variations can impact the development of the heart and the likelihood of developing CPV-2 myocarditis [

1,

9,

27].

5. Conclusions

Viral VP2 mRNA and ISH signals were highest in younger dogs, specifically those aged between 21 and 56 days. However, there was a significant presence of viral mRNA in the hearts of specific older puppies, with the ISH signal being found in the exact location of the heart muscle cells in dogs up to 84 days old. Research on the development of the heart muscle in dogs has indicated that factors that promote the replication of CPV-2 are present from birth until the puppies stop nursing. Nevertheless, there is significant variation in the growth patterns of various dog breeds, influenced by characteristics such as breed type and other variables. These variations can impact the development of the heart and the likelihood of developing CPV myocarditis.

The scope of our investigation is restricted, as the identification of an agent using PCR does not necessarily imply a causal relationship. This investigation was restricted to identifying a solitary factor, and the findings do not preclude the potential contribution of other factors. The scope of this case study was restricted to dogs less than 1 year old. Therefore, the applicability of these findings to cardiac necrosis, inflammation, or fibrosis in older dogs remains uncertain.

The results of our recent case study indicate a strong correlation between CPV infection and the occurrence of myocarditis and cardiac fibrosis in young dogs. This discovery implies that canine parvovirus (CPV) infection of the heart muscle is a present and often overlooked factor in causing damage to the heart in dogs. Moreover, our data indicate a widened period of vulnerability of the heart to CPV myocarditis. Although PCR has contextual limitations, it is a highly sensitive diagnostic for diagnosing parvoviral myocarditis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and S.A.P.; methodology, A.S.; software, S.M.; validation, A.S., I.L. and S.A.P.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, I.L.; resources, S.O.V.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D. and A.S.H.; writing—review and editing, J.D.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, S.O.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Experimental Units and University of Life Sciences for financial support. Also, the authors acknowledge the technical support, materials, and sample processing provided by the Laboratories from the Horia Cernescu Research Unit Timisoara.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ford J, McEndaffer L, Renshaw R, Molesan A, Kelly K. Parvovirus Infection Is Associated with Myocarditis and Myocardial Fibrosis in Young Dogs. Vet Pathol. 2017; 54(6), 964-971. [CrossRef]

- Dines B, Kellihan H, Allen C, Loynachan A, Bochsler P and Newbury S. Case report: Long-term survival in puppies assessed with echocardiography, electrocardiography and cardiac troponin I after acute death in littermates due to parvoviral myocarditis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10:1229756. [CrossRef]

- Horecka, K.; Porter, S.; Amirian, E.S.; Jefferson, E. A Decade of Treatment of Canine Parvovirus in an Animal Shelter: A Retrospective Study. Animals 2020, 10, 939. [CrossRef]

- Mylonakis, M.; Kalli, I.; Rallis, T. Canine parvoviral enteritis: An update on the clinical diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Vet. Med. Res. Rep. 2016, 7, 91–100.

- Khatri, R.; Poonam, M.H.; Minakshi, P.C. Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment of Canine Parvovirus Disease in Dogs: A Mini Review. J. Veter-Sci. Med Diagn. 2017, 6, 06.

- Behdenna A, Lembo T, Calatayud O, et al. Transmission ecology of canine parvovirus in a multi-host, multi-pathogen system. Proc Biol Sci. 2019, 286(1899):20182772. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Buonavoglia, C.; Barrs, V.R. Canine parvovirus vaccination and immunisation failures: Are we far from disease eradication? Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 247, 108760.

- Eregowda CG, De UK, Singh M, et al. Assessment of certain biomarkers for predicting survival in response to treatment in dogs naturally infected with canine parvovirus. Microb Pathog. 2020, 149:104485.

- Jager, M.C., Tomlinson, J.E., Lopez-Astacio, R.A. et al. Small but mighty: old and new parvoviruses of veterinary significance. Virol J 18, 210 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Gallinella G. New insights into parvovirus research. Viruses. 2019, 11(11):1053.

- Dik, I.; Mustafa Emin, O.Z.; Avci, O.; Simsek, A. Determination of Canine Parvovirus Variants in Puppies by Molecular and Phylogenetic Analysis. Pak. Vet. J. 2022, 42, 171.

- Hao, X.; Li, Y.; Xiao, X.; Chen, B.; Zhou, P.; Li, S. The Changes in Canine Parvovirus Variants over the Years. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11540. [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; He, Y.; Wang, C.; Xiao, W.; Liu, R.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, P.; Li, S. The increasing prevalence of CPV-2c in domestic dogs in China. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9869.

- Qi, S.; Zhao, J.; Guo, D.; Sun, D. A Mini-Review on the Epidemiology of Canine Parvovirus in China. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 5.

- Temizkan, M.C.; Sevinc Temizkan, S. Canine Parvovirus in Turkey: First Whole-Genome Sequences, Strain Distribution, and Prevalence. Viruses 2023, 15, 957. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.Y.; Qiu, Y.; Pan, Z.H.; Wang, S.C.; Wang, B.; Wu, W.K.; Yu, J.M.; Yi, Y.; Sun, F.L.; Wang, K.C. Genome sequence characterization of canine parvoviruses prevalent in the Sichuan province of China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 897–907. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.; Wu, H.Y.; Lien, Y.X.; Chiou, M.T.; Lin, C.N. A SimpleProbe((R)) real-time PCR assay for differentiating the canine parvovirus type 2 genotype. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2019, 33, e22654.

- Schirò G, Mira F, Decaro N, et al. Persistence of DNA from canine parvovirus modified-live virus in canine tissues. Vet Res Commun. 2023, 47(2):567-574. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, Azam, Farmani, Naghmeh, & Rajabi, Milad. Detection of Canine Parvovirus by PCR and its association with some of risk factors. Revista MVZ Córdoba. 2018, 23(2), 6607-6616.

- Navarro C, Detection of Canine Parvovirus in Dogs by Means Polymerase Chain Reaction. 2020 - 7(6). AJBSR.

- Latimer HB. Variability in body and organ weights in the newborn dog and cat compared with that in the adult. Anat Rec. 1967, 157:449– 56. [CrossRef]

- Sime TA, Powell LL, Schildt JC, Olson EJ. Parvoviral myocarditis in a 5-week-old Dachshund: parvoviral myocarditis in a puppy. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2015, 25:765–9.

- Reichart D, Magnussen C, Zeller T, Blankenberg S. Dilated cardiomyopathy: from epidemiologic to genetic phenotypes. J Intern Med. 2019, 286:362–72.

- Doyle E. Canine parvovirus and other canine enteropathogens. In:Lila M, Janeczko S, Hurley KF, editors. Infectious Disease Management in Animal Shelters, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2021, p. 321–36.

- Spindel, M.E.; Krecic, M.R.; Slater, M.R.; Vigil, N. Evaluation of a Community’s Risk for Canine Parvovirus and Distemper Using Antibody Testing and GIS Mapping of Animal Shelter Intakes. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2018, 00, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Langhorn R, Willesen JL. Cardiac troponins in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2016, 30:36–50.

- Lakhdhir S, Viall A, Alloway E, Keene B, Baumgartner K, Ward J. Clinical presentation, cardiovascular findings, etiology, and outcome of myocarditis in dogs: 64 cases with presumptive antemortem diagnosis (26 confirmed postmortem) and 137 cases with postmortem diagnosis only (2004–2017). J Vet Cardiol. 2020, 30:44–56.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).