1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) is targeting the elimination of onchocerciasis by 2030 [

1]. In this perspective, Ov16 antibody seroprevalence surveys using Ov16 ELISA techniques have been proposed to evaluate the impact of interventions in targeted areas [

1]. Different Enzyme Linked ImmunoSorbent Assays (ELISA) protocols have been developed (Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas (OEPA) ELISA, Centers for Disease Control (CDC) ELISA, SD Bioline ELISA). However, to carry out these tests, samples need to be transported to a specialized laboratory, which requires a robust cold chain, specialized equipment, and trained personnel. These logistical hurdles have favored the acceptance of Ov16-antibody rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) for field-testing. The latter are more convenient for a point-of-care approach in remote villages but may not be as performant as a laboratory-based ELISA test.

Comparing the performances of Ov16 SD Bioline RDT with laboratory-based Ov16 ELISA has yielded different outcomes in different populations. Among persons with onchocerciasis-associated epilepsy in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the anti-Ov16 ELISA test performed on the participants’ stored serum was more sensitive (83%) than the Ov16 SD Bioline RDT (75%) performed on freshly collected blood [

2]. These sensitivities were determined by comparing each test with the combined results of the other two tests (i.e., the skin snip and whichever anti-Ov16 test was not being evaluated). In contrast, a 99.2% concordance was found between ELISA on dried blood spots (DBS) and Ov16 SD Bioline RDT results (performed on fresh blood) in a study among the general population in rural Cameroon [

3].

The WHO currently recommends the Ov16 SD Bioline RDT on DBS for monitoring onchocerciasis elimination [

4]. However, these approaches are not capable of fully supporting the needs of late-stage control or elimination programs. For onchocerciasis elimination mapping (OEM), diagnostics with a high specificity are needed to minimize the likelihood of treatment decisions being triggered by false positive results. Conversely, in places where stopping mass drug administration (MDA) is considered, diagnostics must also be sensitive enough to detect the weakest positives so that areas needing additional treatment are not missed.

In 2021, the WHO published two Target Product Profiles (TPPs) [

5] describing the desired specifications for new diagnostic tests that would support the two most immediate needs: (a) mapping onchocerciasis in areas of low prevalence and deciding when to start MDA (“Mapping TPP”), and (b) deciding when to stop-MDA programs (“Stopping TPP”). The desired format is a field-deployable RDT, ideally a lateral flow assay (LFA), which is WHO’s preferred format because it is particularly well suited for usage in low-resource settings. For onchocerciasis elimination mapping purposes, the test needs to be ≥ 60% sensitive and ≥ 99.8% specific, whereas supporting stop-MDA decisions require the test to be ≥ 89% sensitive and ≥ 99.8% specific [

5]. The requirement for these high sensitivity and specificity values is dictated by the need to detect as little as 1‒2% of disease prevalence with sufficient statistical confidence, without encountering false positives due to potential cross-reactivity with other filarial parasites.

Based on a WHO call to improve

Onchocerca volvulus RDT performance in terms of sensitivity and specificity, Drugs & Diagnostics for Tropical Diseases (DDTD), San Diego, California has created a new serological RDT for onchocerciasis [

6]. A first prototype (version A) was formatted as a biplex LFA, with four antigens combined into two different test lines. Line 1 detects the presence of human IgG4 antibodies specific for Ov16 and OvOC3261 antigens. Line 2 detects IgG4 antibodies specific for Ov33.3 [

7] and OvOC10469 [

8]. A test is considered positive only if both test lines are visible. Imposing this condition is expected to sacrifice some sensitivity but to improve the overall specificity of the test, which was the goal to be achieved.

It is important to note that the different antigens involved (Ov16, Ov33.3, OvOC3261, and OvOC10469) are expressed by different life stages of the parasite. Ov16 is expressed by infective L3-stage larvae, and therefore humans can develop antibodies to Ov16 when exposed to an infective bite, even if the infective L3 larvae do not mature into adults [

9]. In contrast, Ov33.3 is expressed by adult worms, and OvOC3261 and OvOC10469 are expressed by the microfilariae, and therefore a serological response is observed only after adults have developed and reproduced [

10]. Furthermore, OvOC3261-specific IgG4 antibodies appear to wane faster upon treatment than their Ov16-specific counterpart [

11].

While Ov16 is already a well-established biomarker in the field of onchocerciasis, to the best of our knowledge, OvOC3261, OvOC10469, and Ov33.3 have never been evaluated in the field. It was therefore of interest to evaluate this new DDTD biplex A RDT in the field alongside the Ov16 SD Bioline RDT during a serosurvey among children in Maridi County, an onchocerciasis-endemic area in South Sudan. This study represents the first field evaluation of the DDTD biplex A RDT, and its goal was to compare its sensitivity relative to a monoplex anti-Ov16 test, as well as provide feedback to the test developers on the ease of use and feasibility of using this novel test. The study was not designed to evaluate the specificity of the onchocerciasis DDTD biplex A RDT, which can best be done in non-endemic areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

South Sudan is known to have multiple endemic hotspots of onchocerciasis, including Maridi County in the Western Equatoria State. Maridi County is home to over 115,000 individuals [

11] and is traversed by the Maridi River upon which a dam was built in the 1950s. The dam spillway was identified as the sole blackfly breeding site in Maridi [

12], fueling onchocerciasis transmission in the neighboring villages. In Maridi, the onchocerciasis elimination program includes two strategies: (1) bi-annual Community Directed Treatment with ivermectin (CDTi) and (2) a community based “slash and clear“ vector control method (depleting the blackfly vector population by removing vegetation from the dam’s surface).

This study was conducted in February 2023 in five sites of which Kazana 1, Kazana 2, and Hai-Matara are situated in proximity of the dam (high-transmission zone) and Hai-Tarawa and Hai-Gabat are located further away from the dam (low-transmission zone).

2.2. Study Procedures

In February 2023, a cross-sectional study was conducted in some villages of Maridi. Several weeks before the survey, the research team contacted the community leaders to inform them about the study and obtain their consent and collaboration. One day before participant recruitment, community mobilizers notified villagers about the study and informed them of the site chosen in each village where the eligible children (three to nine years old) would be tested (schools, churches, etc). On the day of the study in each village, the mobilizers used megaphones and health care workers (HCWs) went from house-to-house to gather more participants. All children for whom informed consent was provided by an adult caretaker were enrolled in the study (assent was obtained from children aged seven to nine years).

A short questionnaire was administered to the caretaker and the child to collect relevant information about the child’s history (age, sex, village of residence, previous ivermectin intake, itching/skin lesions, epilepsy). Thereafter, all the participating children were finger-pricked with a 2 millimeter retractable lancet (Ergo lance). A few drops of blood were obtained from the participant’s finger and used for: (i) an Ov16 SD Bioline RDT (Abbott, Illinois, United States); (ii) a DDTD biplex A RDT. Both rapid tests were performed following the manufacturers’ instructions, which stipulated a waiting time of 30 minutes before reading the final test results. For each participant, photos of both RDT types were taken at 20 minutes, 30 minutes, and 60 minutes after performing the tests. We used paper tape to indicate the initial testing time and the read-out times for monitoring purposes. Timings were vigilantly followed up using a smartphone. However, any other type of chronograph would do as well if no photographing of the RDTs is required. All data was collected into the REDCap online platform [

13] using electronic tablets.

Five HCWs from different medical backgrounds and training levels (including a nurse, two clinical officers, and two midwives), were trained in a two-hour hour session to perform the DDTD biplex A RDT. Feasibility and acceptability of the DDTD biplex A RDT were assessed by administering a standardized questionnaire (Supplement 1) to these HCW at the end of the serosurvey.

2.3. Data Analysis

Study data were checked and uploaded into the REDCap secure online platform daily. The final datasets were exported from REDCap and cleaned in Excel spreadsheets, after which they were transferred to the software R version 4.2.2 for analysis. The working assumption was that an DDTD Biplex A RDT was positive when both test lines (T1 and 2) were positive. Other assumptions were added to investigate the individual value of each test line, including: (1) “T1 or T2” one of the lines should be positive for the test result to be considered positive; (2) “All T1”, if T1 was positive, the test result was considered positive; (3) “All T2”, if T2 was positive, the test result was considered positive; (4) “Only T1”, a test was considered positive if only T1 and not T2 was positive; (5) “Only T2”, a test was considered positive if only T2 and not T1 was positive. Continuous variables were summarized as median with interquartile range (IQR), while categorical variables were expressed as percentages.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Study Participants

In total, 239 children aged 3–9 years participated in the study. The median age was six years (IQR: 4-8) and 46% were males. Ninety-two (37.1%) children had some form of dermatitis, as evidenced by itching and/or visible skin lesions. Furthermore, four (1.7%) children were considered to have epilepsy based on their history.

3.2. Comparison Between the Prototype DDTD Biplex A RDT and the Ov16 SD Bioline RDT Results

The

O. volvulus seroprevalence per participant characteristics determined by Ov16 SD Bioline RDT and DDTD biplex A RDT are shown in

Table 1. The seroprevalence with the Ov16 SD Bioline RDT was 30.1% (72/239) while DDTD biplex A RDT (both T1 and T2 lines visible) resulted in a significantly lower seroprevalence of 15.5% (37/239; p<0.001) (

Table 1).

Both tests showed the highest seroprevalence in Kazana 1 and Kazana 2. With the Ov16 SD Bioline RDT, significantly more children with dermatitis tested positive than children without the condition (p=0.002). Although no statistically significant difference was found between seroprevalences of children presenting with and without dermatitis with the DDTD biplex A RDT (p=0.14), there was also a higher trend among children with dermatitis. Both RDT tests showed no significant difference in seroprevalence between children with and without a history of ivermectin intake (Ov16 SD Bioline RDT p=0.33; DDTD biplex A p=0.71), nor between sexes (Ov16 SD Bioline RDT p=0.86; DDTD biplex A RDT p=0.85) and age-groups (Ov16 SD Bioline RDT p=0.72; DDTD biplex A p=0.12). Of the four children with epilepsy, none tested positive with neither RDTs.

O. volvulus seroprevalence per participant characteristics using different DDTD biplex A RDT seropositivity criteria are shown as supplementary material (

Table S1).

3.3. DDTD Biplex A RDT: Analysis of Test Lines

With the DDTD biplex A RDT, a total of 91 children tested positive for at least one of the two test lines (“T1 or T2”;

Table 2). Amongst those 91 cases, a majority were positive only for line T1 (52%; 47/91), some for both test lines (41%; 37/91), and a few only for line T2 only (8%; 7/91). Making the line distribution 52:41:8.

Both the seroprevalence calculated using “T1 or T2” (38.1%) and “All T1” (35.2%) were found to be significantly higher than the seroprevalence calculated using the manufacturers read-out instructions, “T1 and T2”, which was 15.5% (37/239); p<0.001 (

Table 2). Whereas no significant difference was observed when comparing “T1 and T2” (15.5%) with “All T2” (18.4%; p=0.46) and “Only T1” (19.7%; p=0.28). Though, the seroprevalence of “T1 and T2” (15.5%) was significantly higher than “Only T2” (2.9%; p<0.001) (

Table 2).

When comparing these seroprevalences to Ov16 SD Bioline RDT (30.1%, 72/239), no significant difference was found with “T1 or T2” (38.1%; p=0.08), nor “All T1” (35.2%; p=0.28). Though, Ov16 SD Bioline RDT’s seroprevalence was significantly higher than “All T2” (18.4%; p=0.004), “Only T1” (19.7%; p=0.01), and “Only T2” (2.9%; p<0.001) (

Table 2).

Twenty children were found to test positive for at least one line (T1 and/or T2) with DDTD biplex A while testing negative for Ov16 SD Bioline RDT (

Table 3). In contrast, only one child tested positive for Ov16 SD Bioline RDT and negative for DDTD biplex A’s both test lines. However, 41 children tested positive for Ov16 SD Bioline RDT and negative for DDTD biplex A RDT using the “T1 and T2” positivity assumptions suggested by the manufacturers.

3.4. Effect of Timing on the Test Results

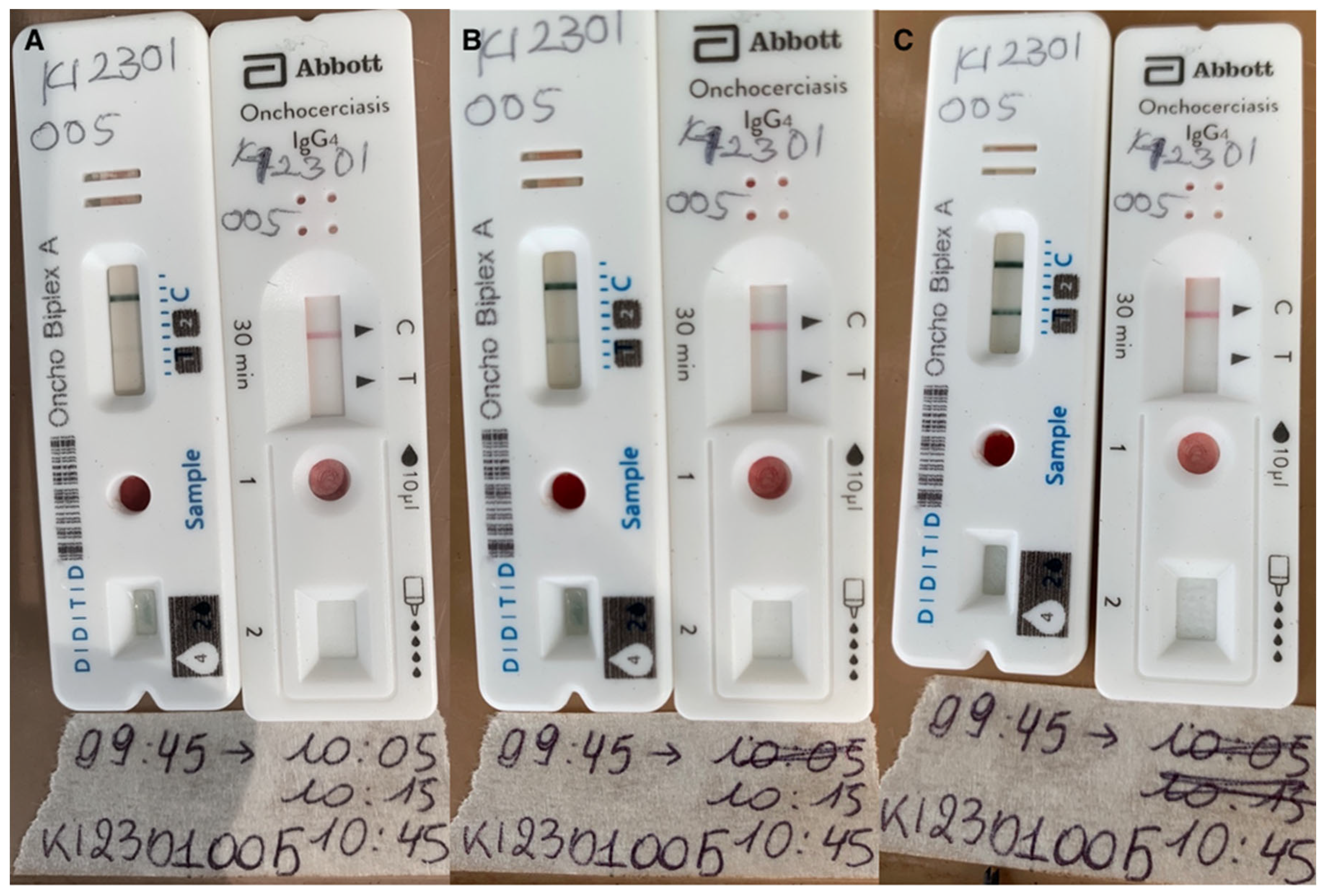

The timed pictures revealed that 91.2% (83/91) of positive DDTD biplex A RDT tests were positive after 20 minutes and the remaining 8.8% (8/91) turned positive after 30 minutes. In addition, 37% (33/90) of test lines tended to turn brighter from 30 to 60 minutes (e.g.

Figure 1).

3.5. Feasibility and Acceptability of the Prototype DDTD Biplex A RDT

The prototype DDTD biplex A RDT was found to be feasible, acceptable, and easy to use in the field by all five HCWs who participated in the study. The HCWs mentioned the similarity between the DDTD biplex A RDT and other finger-pricked based RDTs, such as for HIV and malaria, which made them familiar with the required test procedures. A two-hour training session was sufficient for all HCWs to perform the test and fill the participants’ questionnaires correctly. However, there were difficulties in monitoring the timings of several tests simultaneously by the HCWs, especially as there was a continuous influx of children for whom study consent had to be sought. The most effective way of organizing the HCWs for the RDT research purpose was in teams of two, one to manage participant intake and questionnaire administration, and one to perform the test. This in addition to a person designated for test read-outs who remained stationed in a central place. Based on observation, time calculation for read-out proved to be difficult. Therefore, additional training was provided to ensure correct read-out timing.

The area surrounding the read-out desk was used as a waiting area for people who would like to be notified of their test results, thereby creating the opportunity to report results effectively and efficiently.

4. Discussion

The anti-Ov16 seroprevalence was 30.1% (72/239) with the Ov16 SD Bioline RDT, whereas with the DDTD biplex A RDT (both T1 and T2 lines positive) the seroprevalence was statistically significantly lower at 15.5% (37/239; p<0.001). Considering only the DDTD biplex A RDT T1 line detecting Ov16 and OvOC3261 antibodies, the seroprevalence was 35.1% (84/239), which is not significantly higher than the seroprevalence determined with the Ov16 SD Bioline RDT (p=0.28).

With the DDTD biplex A RDT, a total of 91 children tested positive for at least one of the two test lines, with a line distribution of 51:41:8 where most children tested positive for T1. This distribution is noticeably different from previously reported distributions by the NIH (9:84:7) and CDC (7:84:9), where most samples proved positive for both tests lines (calculated from figure 6C of [

10]). This presumably reflects the fact that NIH and CDC evaluations were conducted using sera from people with confirmed infection. Meanwhile, the current study was performed in the field, as a survey, using whole blood obtained by finger-pricking. Moreover, this survey involved a younger population that could have been exposed to

O. volvulus infective bites (Ov16) and therefore be positive by test line 1. However, they may have had less time and possibilities to develop a patent infection (Ov33.3, OvOC10469) and could have therefore remained negative for test line 2. Indeed, an increasing anti-Ov16 seroprevalence with age has previously been observed in another community-based study in the DRC [

14]. Both anti-Ov16/anti-OvOC3261 (line T1) and anti-Ov33.3/anti-OvOC10469 (line T2) seropositivity were associated with dermatitis, which is mediated by the

O. volvulus microfilariae. OvOC3261 is indeed thought to be expressed solely or at least primarily by the microfilariae [

8]. Further longitudinal studies in children are needed to fully understand the seroconversion dynamics of the different antigens involved, especially as surveys within this age group (3-9 years old) are recommended by WHO to monitor the onchocerciasis elimination targets [

4].

The fact that the seroprevalence for anti-Ov16/anti-OvOC3261 (35.1%) was twice as high as that for anti-Ov33.3/anti-OvOC10469 (18.4%) is consistent with the fact that the antigens are expressed at different stages of the parasite lifecycle. It should be emphasized that the DDTD biplex A RDT is intended to be counted as positive only if both lines are positive (15.5%), and this needs to be contrasted again with the higher anti-Ov16 seroprevalence (35.1%). As a result, if the DDTD biplex A RDT or a similar version thereof is to be used in making start- or stop-MDA decisions, the seroprevalence thresholds used to make such decisions may need to be different than if based solely on anti-Ov16. Refining these thresholds will require significant further operational research.

Additional studies including well characterized human adult populations and in other onchocerciasis-endemic regions will be needed to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the DDTD biplex A RDT compared to a gold standard. In such studies, study participants should be skin snip tested and assessed for parasitological co-infections, particularly other filarial parasites capable of eliciting cross-reactive immune responses. Notably, individuals should be tested for the presence of

Mansonella perstans, often occurring as a co-infection in persons with onchocerciasis in South Sudan to exclude possible cross-reactivity with

M. perstans antibodies that may influence the specificity of the test [

15].

Our study had several limitations. For ethical reasons, no skin snips were done to ascertain the diagnosis of onchocerciasis in the participating children, hence the true sensitivity of the RDTs compared to microfilariae-positive children could not be assessed. The final set-up that was adopted for performing the RDT required up to three HCWs (two mobile, plus one stationary read-out supervisor) and allowed for some door-to-door recruitment by the mobile HCWs. This approach certainly provides better epidemiological predictions by simulating community seroprevalence with greater accuracy. On the downside, it also implied increased personnel costs in case this strategy is to be replicated.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, Maridi remains a hotspot for O. volvulus transmission even after implementation of elimination measures. These measures should be strengthened even further and ivermectin treatment coverage should be increased to move towards the onchocerciasis elimination goals of WHO slated for 2030. A highly sensitive and specific O. volvulus RDT that could be done in the field would be an important tool to plan O. volvulus elimination measures and assess the progress towards elimination. Whether the DDTD biplex D test, a newly optimised version of the DDTD biplex RDT, could be such a test will need to be investigated in additional studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Questionnaire:

O. volvulus Rapid Diagnostic Test Assessment Form for Children 3–9 years. Table S1:

O. volvulus seroprevalence per participant characteristics using different DDTD biplex A RDT positivity criteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H., S.R.J. M.B. and R.C.; methodology, A.H., L-J. A., and R.C.; software, A.H.; validation, R.C.; formal analysis, A.H. and J.N.S.F.; investigation, S.R.J and A.H.; resources, R.C. and M.B.; data curation, A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H., R.C. and J.N.S.F.; writing—review and editing, A.H., S.R.J., C.L., L-J.A., M.B., D.K.D.S., K.D.K.D., Y.Y.B., J.N.S.F. and R.C.; visualization, A.H.; project administration, R.C.; funding acquisition, K.D.K.D. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Research Council, grant number 768815 and the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO), grant number: 1296723N.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of Antwerp’s ethics committee (Ref: BUN B300201940004) and the ethics committee of the Ministry of Health of South Sudan MOH/RERB 56/2022 (Protocol No RERB_MOH 48/18/09/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the clinical officers, nurses and research assistants who conducted the surveys; to the Maridi Health Sciences Institute and Amref Health Africa for using its facilities, equipment, and vehicles; to the Western Equatoria State and the Maridi County governments for their support; and to the population of the Maridi settlements for their cooperation and participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CDC |

Centre for Disease Control |

| CDTi |

Community Directed Treatment with ivermectin |

| DBS |

Dry blood spots |

| DDTD |

Drugs & Diagnostics for Tropical Diseases |

| ELISA |

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay |

| HCW |

Health care worker |

| LFA |

Lateral flow assay |

| MDA |

Mass drug administration |

| OEPA |

Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas |

| O. volvulus |

Onchocerca volvulus |

| RDT |

Rapid diagnostic test |

| TTP |

Target Product Profile |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- WHO. Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030. 2020.

- Hotterbeekx A, Perneel J, Mandro M, Abhafule G, Siewe Fodjo JN, Dusabimana A, et al. Comparison of Diagnostic Tests for Onchocerca volvulus in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Pathogens. 2020;9(6).

- Ekanya R, Beng AA, Anim MA, Pangwoh YZ, Dibando OE, Gandjui NVT, et al. Concordance between Ov16 Rapid Diagnostic Test(RDT) and Ov16 Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for the Diagnosis of Onchocerciasis in Areas of Contrasting Endemicity in Cameroon. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2023;21:e00290.

- Guidelines for stopping mass drug administration and verifying elimination of human onchocerciasis: criteria and procedures. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016. Report No.: WHO/HTM/NTD/PCT/2016.1.

- WHO. Onchocerciasis: diagnostic target product profile to support preventive chemotherapy. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240024496; Accessed 10 January 2025.

- Biamonte MA, Cantey PT, Coulibaly YI, Gass KM, Hamill LC, Hanna C, et al. Onchocerciasis: Target product profiles of in vitro diagnostics to support onchocerciasis elimination mapping and mass drug administration stopping decisions. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(8):e0010682.

- Feeser KR, Cama V, Priest JW, Thiele EA, Wiegand RE, Lakwo T, et al. Characterizing Reactivity to Onchocerca volvulus Antigens in Multiplex Bead Assays. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(3):666-72.

- Bennuru S, Cotton JA, Ribeiro JM, Grote A, Harsha B, Holroyd N, et al. Stage-Specific Transcriptome and Proteome Analyses of the Filarial Parasite Onchocerca volvulus and Its Wolbachia Endosymbiont. mBio. 2016;7(6).

- Eberhard ML, Dickerson JW, Tsang VC, Walker EM, Ottesen EA, Chandrashekar R, et al. Onchocerca volvulus: parasitologic and serologic responses in experimentally infected chimpanzees and mangabey monkeys. Exp Parasitol. 1995;80(3):454-62.

- Bennuru S, Oduro-Boateng G, Osigwe C, Del Valle P, Golden A, Ogawa GM, et al. Integrating Multiple Biomarkers to Increase Sensitivity for the Detection of Onchocerca volvulus Infection. J Infect Dis. 2020;221(11):1805-15.

- South Sudan - County Population Estimates - 2015-2020 - Humanitarian Data Exchange. [Available from: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/south-sudan-county-population-estimates-2015-2020; Accessed 10 January 2025.

- Lakwo TL, Raimon S, Tionga M, Siewe Fodjo JN, Alinda P, Sebit WJ, et al. The Role of the Maridi Dam in Causing an Onchocerciasis-Associated Epilepsy Epidemic in Maridi, South Sudan: An Epidemiological, Sociological, and Entomological Study. Pathogens. 2020;9(4).

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

- Lenaerts E, Mandro M, Mukendi D, Suykerbuyk P, Dolo H, Wonya'Rossi D, et al. High prevalence of epilepsy in onchocerciasis endemic health areas in Democratic Republic of the Congo. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):68.

- Tumwine JK, Vandemaele K, Chungong S, Richer M, Anker M, Ayana Y, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of nodding syndrome in Mundri County, southern Sudan. Afr Health Sci. 2012;12(3):242-8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).