Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Waste Cooking Oils (WCOs) ARE produced in large quantities worldwide from hospitality, household and other industrial compartments. Today many Countries have no specific legislation regarding WCOs management, generating a crucial environmental problem. Presently WCOs are mainly employed by industry as feedstock for biodiesel and energy production. Nevertheless, the use of WCOs as a primary feedstock for second generation biodiesel production depends on its availability, and often import of biodiesel or WCOs from other countries is required. Additionally, the EU is pushing towards the privileged use of biowaste for alternative high value products, other than biodiesel, to reach carbon neutrality by 2050. Thus, the aim of this review is to give an overall comprehensive panorama of the production, impacts, regulations and restrictions affecting WCOs, and their possible uses to produce high value materials such as bio lubricants, bio surfactants, polymers and polymer additives, road and construction additives, bio solvents among others. Interestingly many reviews have been reported in the literature addressing the use of WCOs for the preparation of a specific class of polymer, but a general comprehensive review on the argument is missing.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

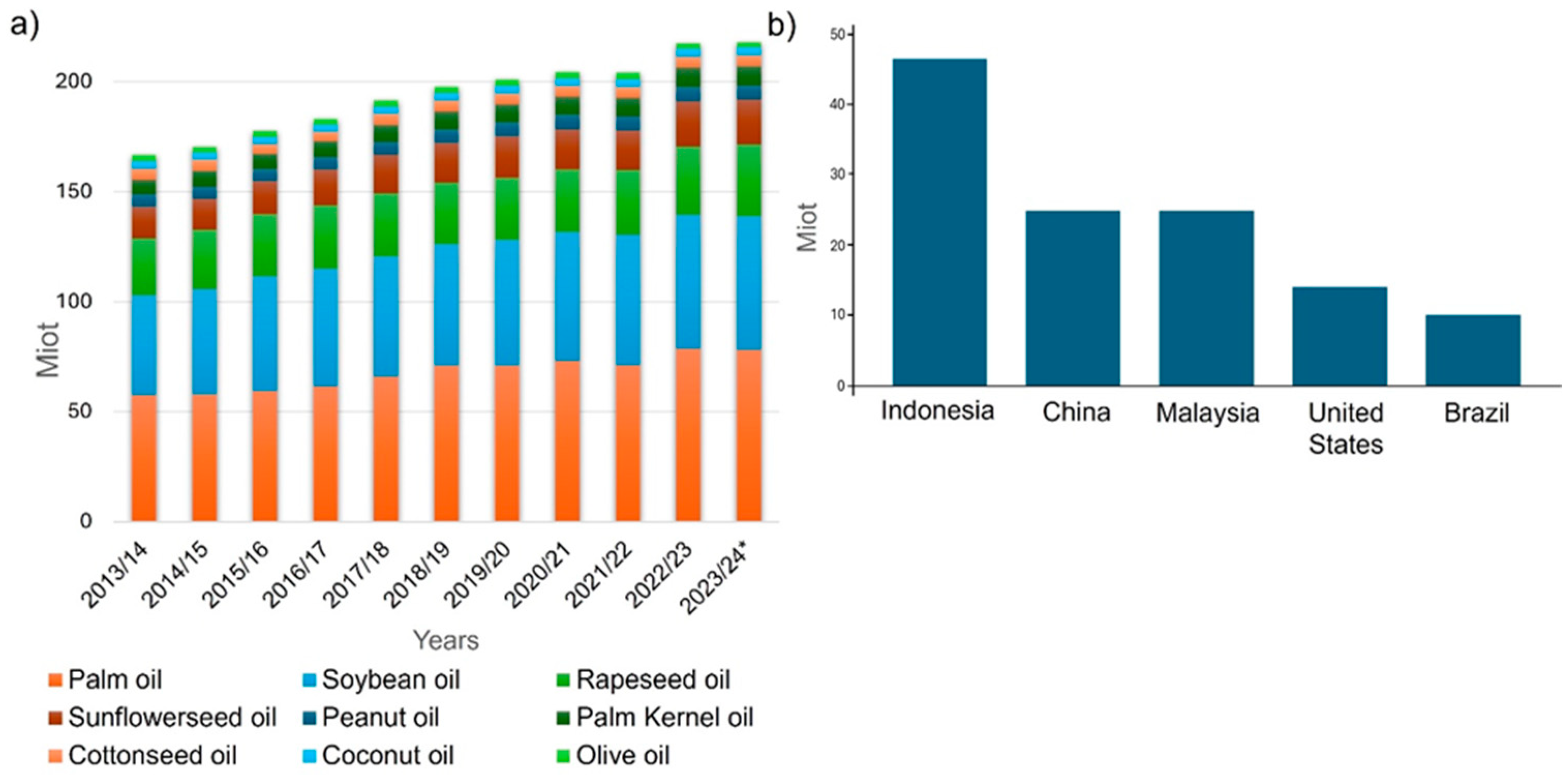

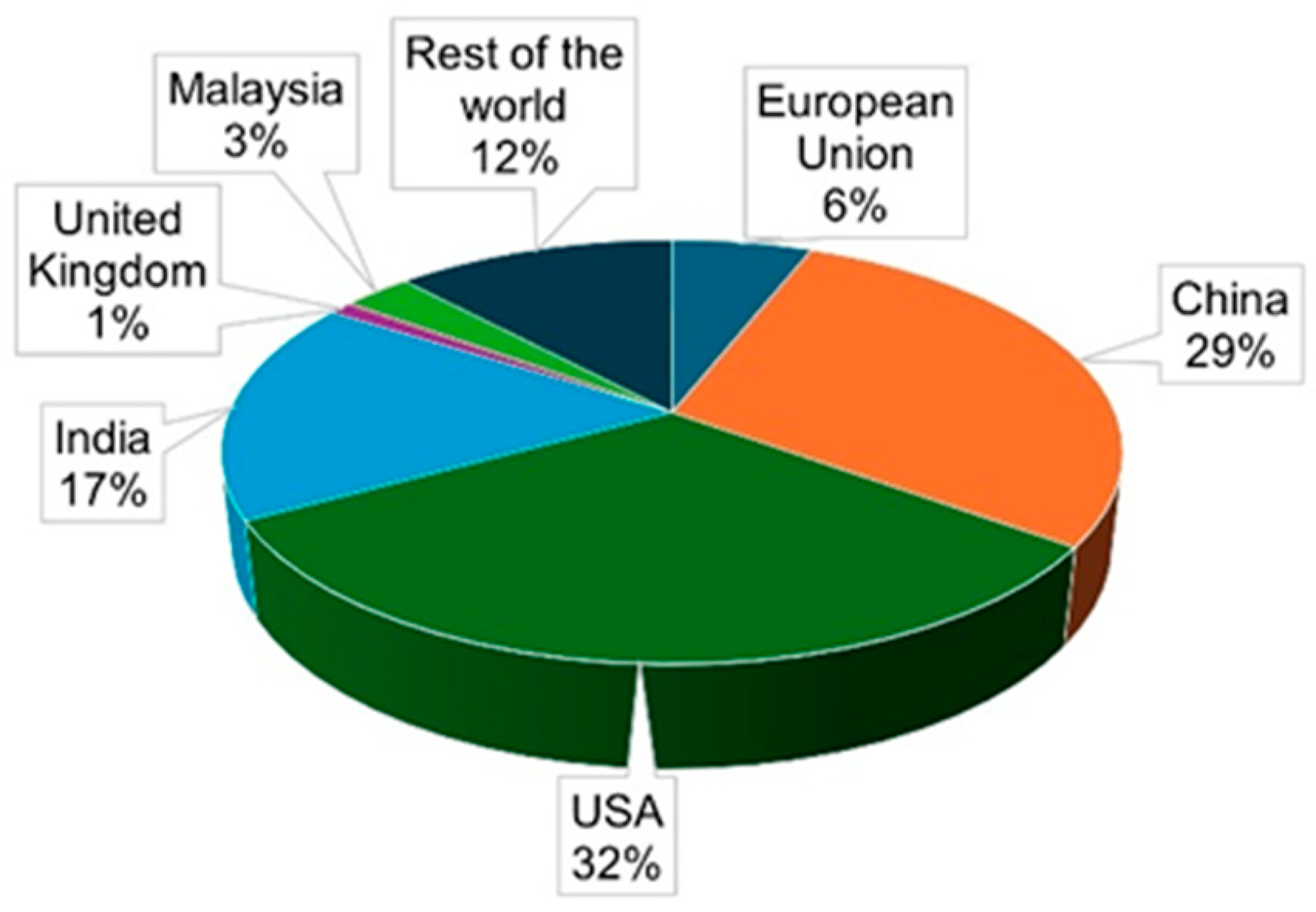

3. WCOs Production and Market

4. EU Regulations and Restrictions Affecting WCOs

5. Environmental Impacts of WCOs

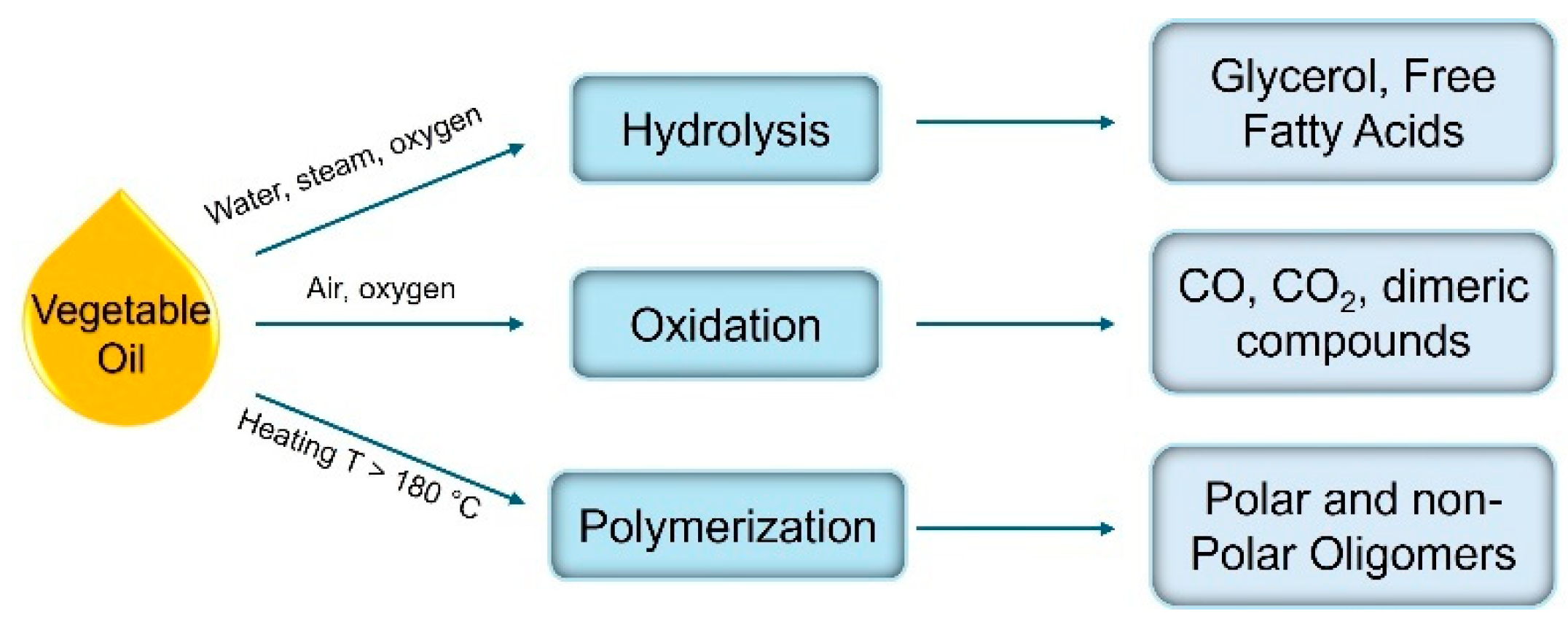

6. WCOs Composition and Pre-Treatments

7. WCOs for Bio Lubricants and Bio Surfactants

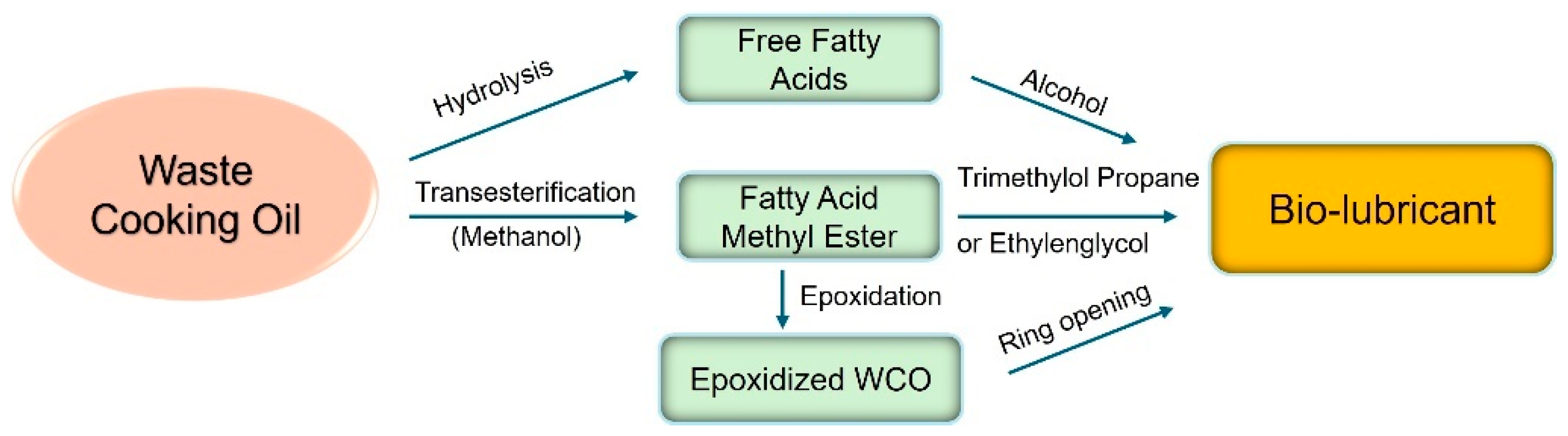

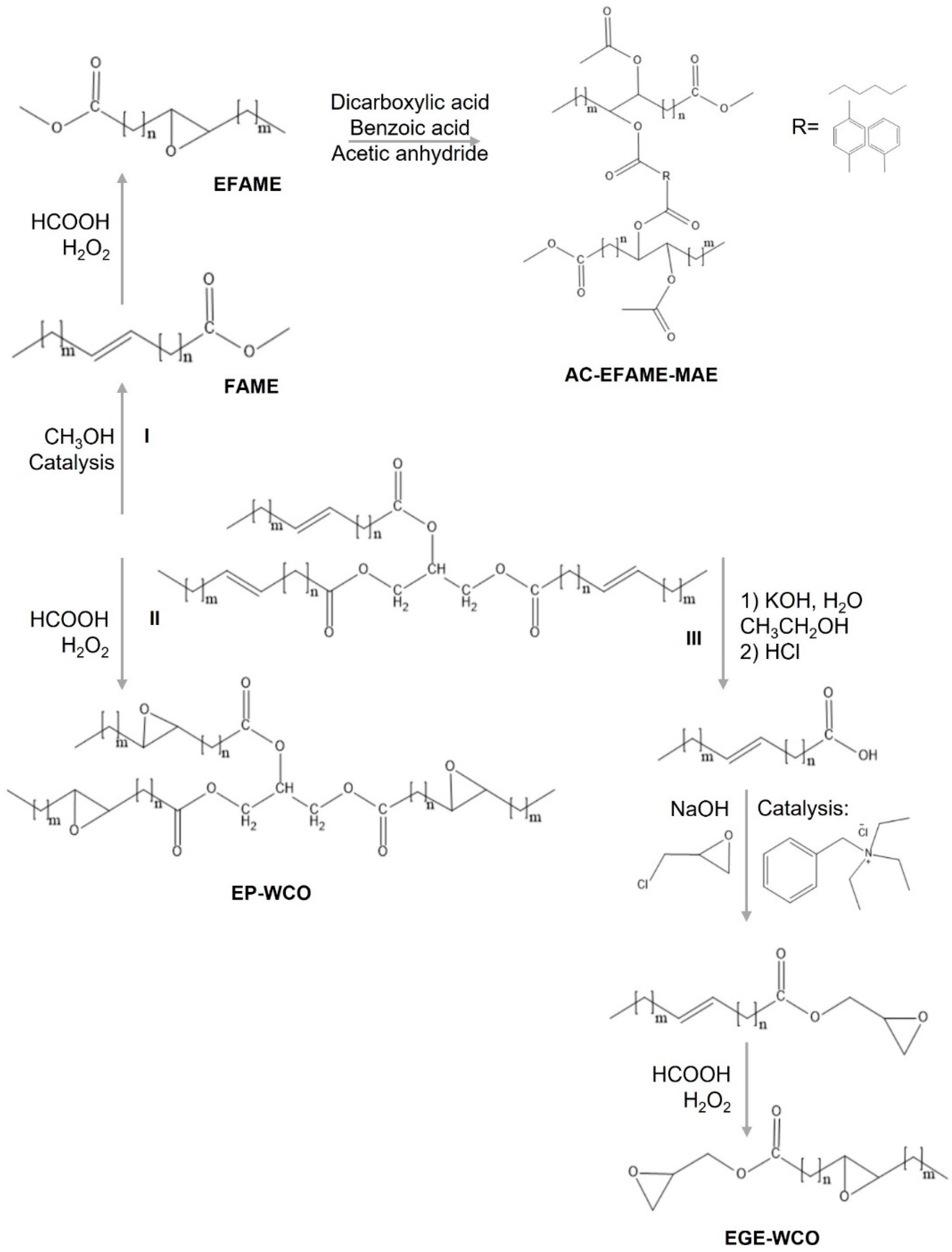

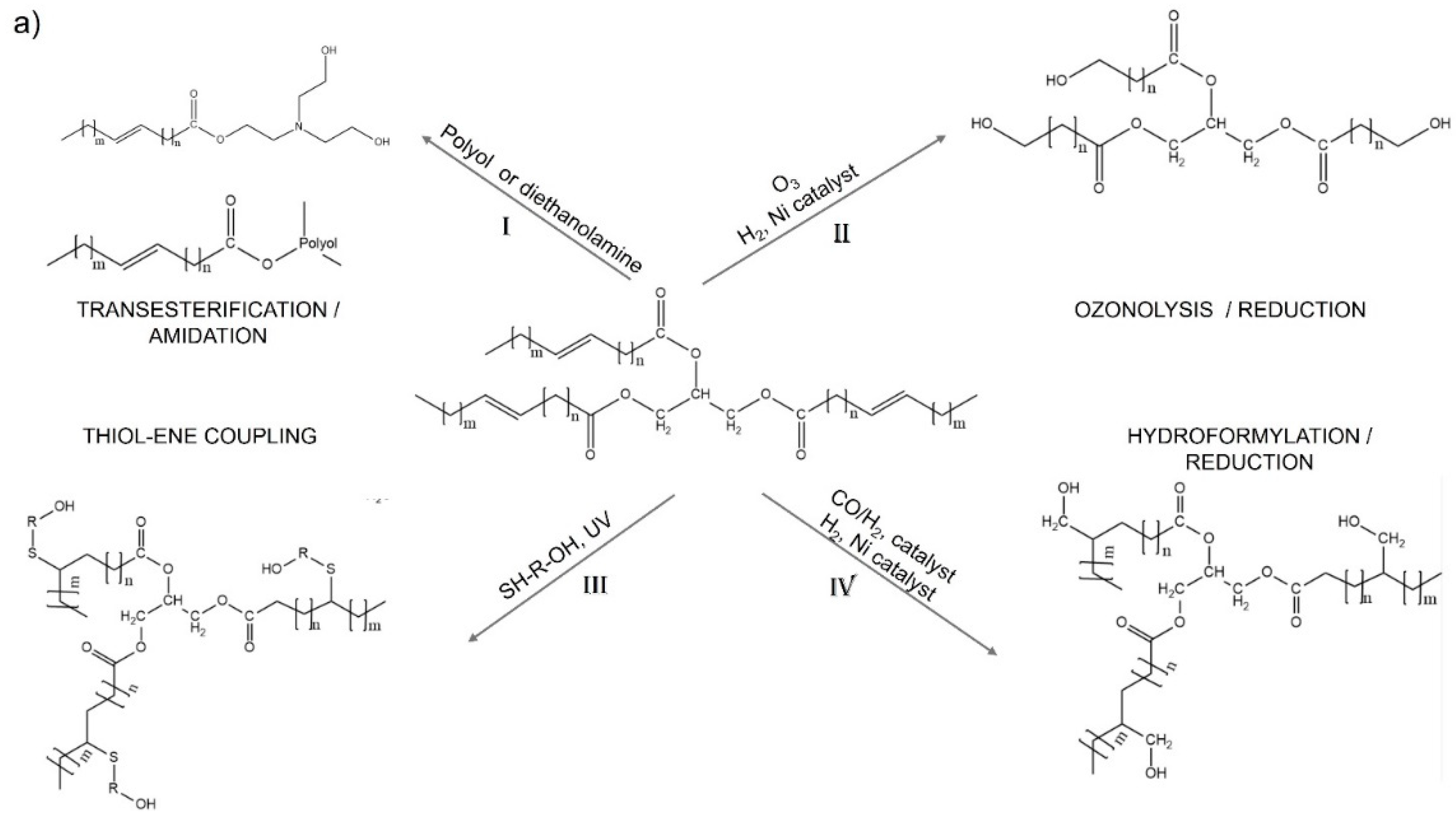

7.1. Bio Lubricants

7.2. Bio Surfactants

8. WCOs for Polymer Additives

9. WCOs for Polymer Synthesis

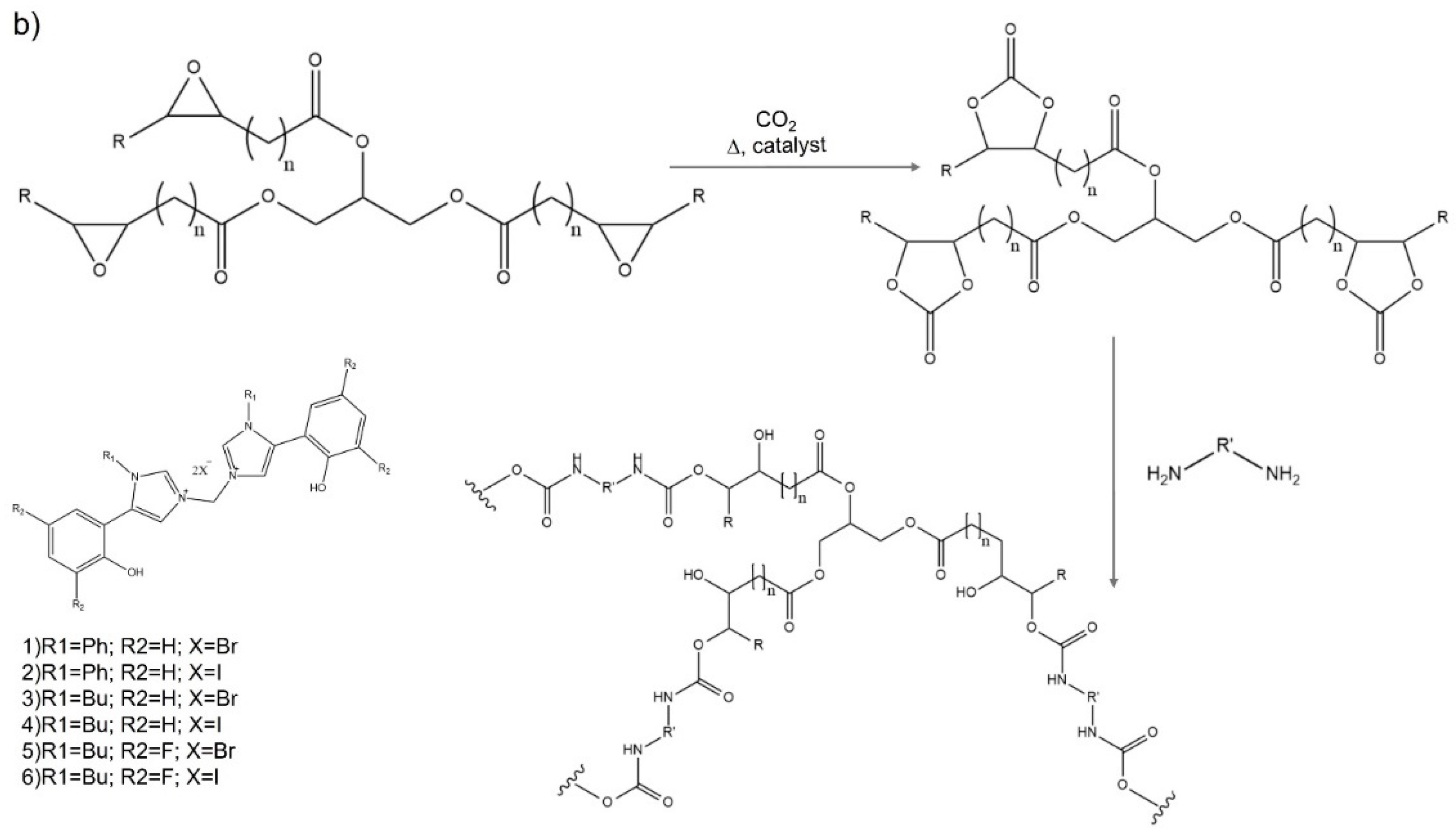

9.1. Polyurethane

9.2. Acrylic Polymers

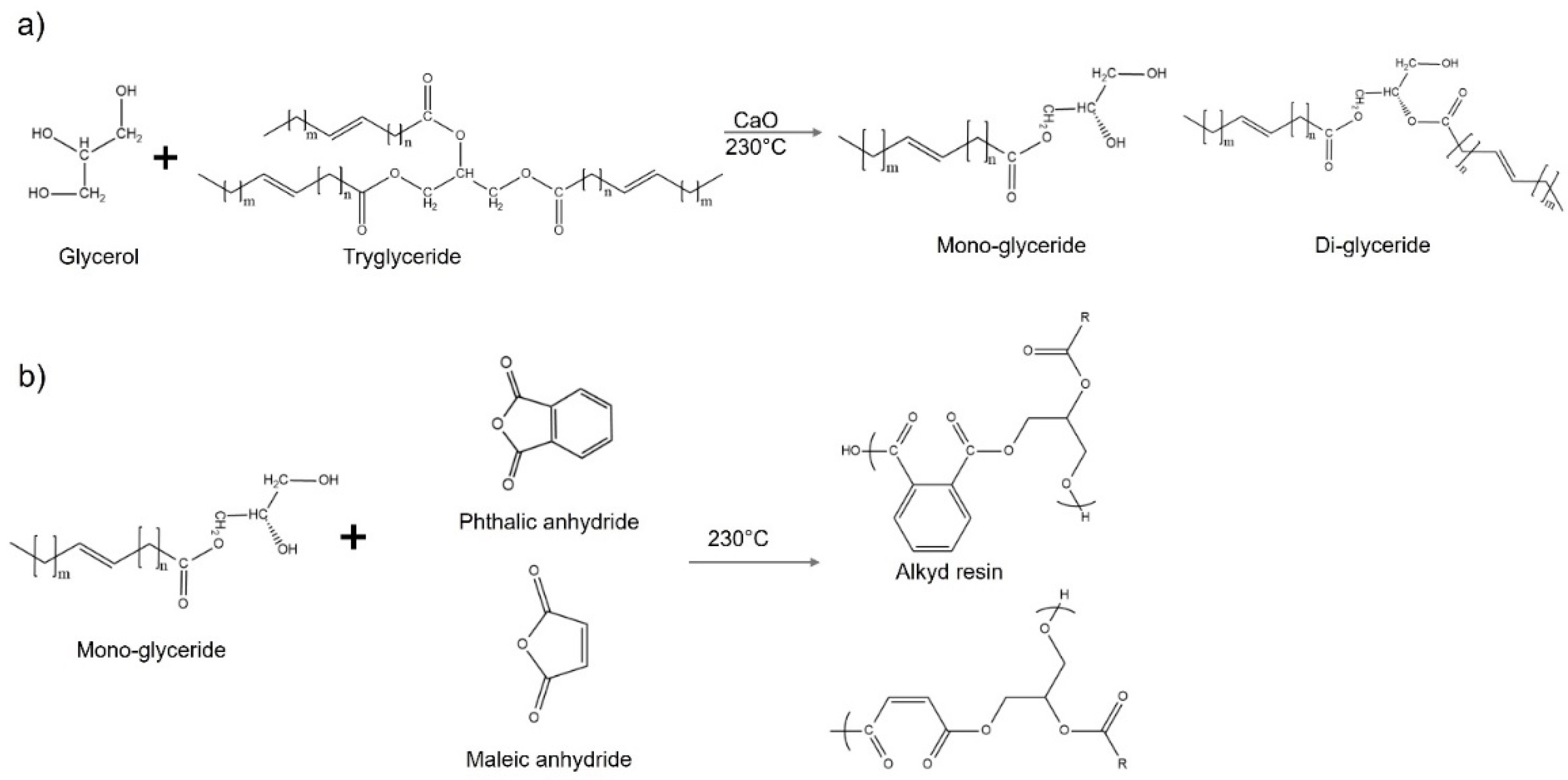

9.3. Alkyd Esters

9.4. Epoxy Resins

10. Waste Cooking Oil for Roads and Constructions

10.1. WCO for Asphalt Production

10.2. WCOs for Concrete

11. WCOs as Bio Solvents

12. Other Applications

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferrusca, M.C.; Romero, R.; Martínez, S.L.; Ramírez-Serrano, A.; Natividad, R. Biodiesel Production from Waste Cooking Oil: A Perspective on Catalytic Processes. Processes 2023, 11, 1952. [CrossRef]

- Statista, 2024a. Global production of vegetable oils from 2000/01 to 2023/24. https://www.statista.com/statistics/263978/global-vegetable-oil-production-since-2000-200.

- Azahar, W.N.A.W.; Bujang, M.; Jaya, R.P.; Hainin, M.R.; Mohamed, A.; Ngad, N.; Jayanti, D.S. The potential of waste cooking oil as bio-asphalt for alternative binder - an overview. J. Teknol. 2016, 78, 3722. [CrossRef]

- Iowa Farm Bureau, 2022. What’s Cooking with Vegetable Oils. https://www.iowafarmbureau.com/Article/Whats-Cooking-with-Vegetable-Oils.

- Markets and Markets, 2023. Biofuel market. https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/biofuels-market-297.html?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwwMqvBhCtARIsAIXsZpYveQ0-50boErhnWFXCgq_Z0oq8tQpxCUuu7vgZ44hackufMVylwJEaAmf-EALw_wcB.

- NationMaster, 2023. Vegetable Oils Production.

- Oils and fats international, 2021. Global vegetable oil production in 2021/22 crop year set to reach record high. https://www.ofimagazine.com/news/global-vegetable-oil-production-in-2021-22-crop-year-set-to-reach-record-high.

- Statista, 2024b. Forecast volume of vegetable oil consumed in the European Union (EU 27) from 2018 to 2032. https://www.statista.com/statistics/614522/vegetable-oil-consumption-volume-european-union-28/.

- Statista, 2024c. Consumption of vegetable oils worldwide from 2013/14 to 2023/2024, by oil type. https://www.statista.com/statistics/263937/vegetable-oils-global-consumption/.

- Isaksson, B. Demand for edible oils increases as biofuel industry grows. Biofuels International 2023. https://biofuels-news.com/news/demand-for-edible-oils-increases-as-biofuel-industry-grows/ (accessed 7.10.24).

- Waters, K., Altiparmak, S.O., Shutters, S.T., Thies, C. The Green Mirage: The EU’s Complex Relationship with Palm Oil Biodiesel in the Context of Environmental Narratives and Global Trade Dynamics. Energies 2024, 17, 343. [CrossRef]

- Awogbemi, O., Inambao, F., Onuh, E.I., 2018. A review of the performance and emissions of compression ignition engine fuelled with waste cooking oil methyl ester, in: 2018 International Conference on the Domestic Use of Energy (DUE). IEEE, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Awogbemi, O.; Onuh, E.I.; Inambao, F.L. Comparative study of properties and fatty acid composition of some neat vegetable oils and waste cooking oils. International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies 2019, 14, 417–425. [CrossRef]

- Saba, T., Estephane, J., El Khoury, B., El Khoury, M., Khazma, M., El Zakhem, H., Aouad, S., 2016. Biodiesel production from refined sunflower vegetable oil over KOH/ZSM5 catalysts. Renew. Energy 2016, 90, 301–306. [CrossRef]

- Foo, W.H., Chia, W.Y., Tang, D.Y.Y., Koay, S.S.N., Lim, S.S., Chew, K.W. The conundrum of waste cooking oil: Transforming hazard into energy. J. Hazard Mater. 2021, 417, 126129. [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, L., Mendecka, B., Carnevale, E. Comparative life cycle assessment of alternative strategies for energy recovery from used cooking oil. J. Environ. Manage 2018, 216, 235–245. [CrossRef]

- Aniołowska, M., Zahran, H., Kita, A. The effect of pan frying on thermooxidative stability of refined rapeseed oil and professional blend. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 712–720. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.R., Nogueira, R., Nunes, L.M. Quantitative assessment of the valorisation of used cooking oils in 23 countries. Waste Management 2018, 78, 611–620. [CrossRef]

- Olu-Arotiowa, O.A., Odesanmi, A.A, Adedotun, B.K., Ajibade, O.A., Olasesan, I.P., Odofin, O.L., Abass, A. O. Review on environmental impact and valourization of waste cooking oil. LAUTECH Journal of Engineering and Technology 2022, 16, 144–163. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366618878.

- Fingas, M. Vegetable Oil Spills, in: Handbook of Oil Spill Science and Technology. Wiley, 2014, pp. 79–91. [CrossRef]

- Zahri, K.N.M., Zulkharnain, A., Sabri, S., Gomez-Fuentes, C., Ahmad, S.A. Research Trends of Biodegradation of Cooking Oil in Antarctica from 2001 to 2021: A Bibliometric Analysis Based on the Scopus Database. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2050. [CrossRef]

- Foo, W.H., Koay, S.S.N., Chia, S.R., Chia, W.Y., Tang, D.Y.Y., Nomanbhay, S., Chew, K.W. Recent advances in the conversion of waste cooking oil into value-added products: A review. Fuel 2022, 324. [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, J., Orjuela, A., Sánchez, D.L., Narváez, P.C., Katryniok, B., Clark, J. Pre-treatment of used cooking oils for the production of green chemicals: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 1215129. [CrossRef]

- Capuano, D., Costa, M., Di Fraia, S., Massarotti, N., Vanoli, L. Direct use of waste vegetable oil in internal combustion engines. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017. [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Cabello, M., Garcia, I.L., Leiva-Candia, D., Dorado, M.P. Valorization of food waste based on its composition through the concept of biorefinery. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2018, 14, 67–79. [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Cabello, M., García, I.L., Sáez-Bastante, J., Pinzi, S., Koutinas, A.A., Dorado, M.P. Food waste from restaurant sector – Characterization for biorefinery approach. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 301, 122779. [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Cabello, M., Leiva-Candia, D., Castro-Cantarero, J.L., Pinzi, S., Dorado, M.P. Valorization of food waste from restaurants by transesterification of the lipid fraction. Fuel 2018, 215, 492–498. [CrossRef]

- Chrysikou, L.P., Dagonikou, V., Dimitriadis, A., Bezergianni, S. Waste cooking oils exploitation targeting EU 2020 diesel fuel production: Environmental and economic benefits. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 566–575. [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, B., Bidini, G., Zampilli, M., Laranci, P., Bartocci, P., Fantozzi, F. Straight and waste vegetable oil in engines: Review and experimental measurement of emissions, fuel consumption and injector fouling on a turbocharged commercial engine. Fuel 2016, 182, 198–209. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R., Anzar, N., Sharma, P., Malode, S.J., Shetti, N.P., Narang, J., Kakarla, R.R. Converting biowaste into sustainable bioenergy through various processes. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mannu, A., Ferro, M., Di Pietro, M.E., Mele, A. Innovative applications of waste cooking oil as raw material. Sci. Prog. 2019, 102, 153–160. [CrossRef]

- Namoco, C.S., Comaling, V.C., Buna, C.C. Utilization of used cooking oil as an alternative cooking fuel resource. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2017, 12, 435–442.

- Ostadkalayeh, Z.H., Babaeipour, V., Pakdehi, S.G., Sazandehchi, P. Optimization of Biodiesel Production Process from Household Waste Oil, Rapeseed, and Microalgae Oils as a Suitable Alternative for Jet Fuel. Bioenergy Res. 2023, 16, 1733–1745. [CrossRef]

- Sahar, Sadaf, S., Iqbal, J., Ullah, I., Bhatti, H.N., Nouren, S., Habib-ur-Rehman, Nisar, J., Iqbal, M. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil: An efficient technique to convert waste into biodiesel. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 41, 220–226. [CrossRef]

- Sudalai, S., Prabakaran, S., Varalakksmi, V., Sai Kireeti, I., Upasana, B., Yuvasri, A., Arumugam, A. A review on oilcake biomass waste into biofuels: Current conversion techniques, sustainable applications, and challenges: Waste to energy approach (WtE). Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 314, 118724. [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, V., Gatto, V., Samiolo, R., Scolaro, C., Brahimi, S., Facchin, M., Visco, A. Plastics today: Key challenges and EU strategies towards carbon neutrality: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 334, 122102. [CrossRef]

- Visco, A., Scolaro, C., Facchin, M., Brahimi, S., Belhamdi, H., Gatto, V., Beghetto, V. Agri-Food Wastes for Bioplastics: European Prospective on Possible Applications in Their Second Life for a Circular Economy. Polymers 2022, 14, 2752. [CrossRef]

- Facchin, M., Gatto, V., Samiolo, R., Conca, S., Santandrea, D., Beghetto, V. May 1,3,5-Triazine derivatives be the future of leather tanning? A critical review. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 345, 123472. [CrossRef]

- Sole, R., Gatto, V., Conca, S., Bardella, N., Morandini, A., Beghetto, V. Sustainable Triazine-Based Dehydro-Condensation Agents for Amide Synthesis. Molecules, 2021, 26, 191. [CrossRef]

- Purohit, V.B., Pięta, M., Pietrasik, J., Plummer, C.M. Towards sustainability and a circular Economy: ROMP for the goal of fully degradable and chemically recyclable polymers. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 208, 112847. [CrossRef]

- Thushari, I., Babel, S. Comparative study of the environmental impacts of used cooking oil valorization options in Thailand. J. Environ. Manage 2020, 310, 114810. [CrossRef]

- Hamze, H., Akia, M., Yazdani, F. Optimization of biodiesel production from the waste cooking oil using response surface methodology. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2015, 94, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, J., Martel Martín, S., Baldino, S., Prandi, C., Mannu, A. European Union Legislation Overview about Used Vegetable Oils Recycling: The Spanish and Italian Case Studies. Processes 2020, 8, 798. [CrossRef]

- Mannu, A., Garroni, S., Ibanez Porras, J., Mele, A. Available Technologies and Materials for Waste Cooking Oil Recycling. Processes 2020, 8, 366. [CrossRef]

- Mannu, A., Ferro, M., Dugoni, G.C., Panzeri, W., Petretto, G.L., Urgeghe, P., Mele, A. Improving the recycling technology of waste cooking oils: Chemical fingerprint as tool for non-biodiesel application. Waste Management 2019, 96, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z., Dierenfeld, E.S., Wang, X., Chen, X., Shurson, G.C. A critical analysis of challenges and opportunities for upcycling food waste to animal feed to reduce climate and resource burdens. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 203, 107418. [CrossRef]

- Panadare, D.C., Rathod, V.K. Applications of Waste Cooking Oil Other Than Biodiesel: A Review, Iranian J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 12, 55-76. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.ijche.com/article_11253_54b41ee620eb7a8972ee3e37776dad5f.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiMoK66rouIAxWPg_0HHbj0DNgQFnoECBsQAQ&usg=AOvVaw11QJ42AupQ5PiqrF-UlbHz.

- Salemdeeb, R., zu Ermgassen, E.K.H.J., Kim, M.H., Balmford, A., Al-Tabbaa, A. Environmental and health impacts of using food waste as animal feed: a comparative analysis of food waste management options. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 871–880. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A., Ahmmed, R., Ahsan, S.M., Rana, J., Ghosh, M.K., Nandi, R. A comprehensive review of food waste valorization for the sustainable management of global food waste. Sustainable Food Technology 2024, 2, 48–69. [CrossRef]

- Bardella, N., Facchin, M., Fabris, E., Baldan, M., Beghetto, V. Waste Cooking Oil as Eco-Friendly Rejuvenator for Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement. Materials 2024, 17, 1477. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Xue, L., Xie, W., You, Z., Yang, X. Laboratory investigation on chemical and rheological properties of bio-asphalt binders incorporating waste cooking oil. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 348–358. [CrossRef]

- Staroń, A., Chwastowski, J., Kijania-Kontak, M., Wiśniewski, M., Staroń, P. Bio-enriched composite materials derived from waste cooking oil for selective reduction of odour intensity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16311. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Wang, J., Kang, H. Effect of waste cooking oil on the performance of EVA modified asphalt and its mechanism analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14072. [CrossRef]

- Onn, M., Jalil, M.J., Mohd Yusoff, N.I.S., Edward, E.B., Wahit, M.U. A comprehensive review on chemical route to convert waste cooking oils to renewable polymeric materials. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 211, 118194. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N., Agarwal, P., Porwal, J., Porwal, S.K. Evaluation of multifunctional green copolymer additives–doped waste cooking oil–extracted natural antioxidant in biolubricant formulation. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 761–770. [CrossRef]

- Marriam, F., Irshad, A., Umer, I., Asghar, M.A., Atif, M. Vegetable oils as bio-based precursors for epoxies. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 31, 100935. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N., Agarwal, P., Porwal, S.K. Natural Antioxidant Extracted Waste Cooking Oil as Sustainable Biolubricant Formulation in Tribological and Rheological Applications. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 3127–3137. [CrossRef]

- Wierzchowska, K., Derewiaka, D., Zieniuk, B., Nowak, D., Fabiszewska, A. Whey and post-frying oil as substrates in the process of microbial lipids obtaining: a value-added product with nutritional benefits. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 2675–2688. [CrossRef]

- Lhuissier, M., Couvert, A., Amrane, A., Kane, A., Audic, J.L. Characterization and selection of waste oils for the absorption and biodegradation of VOC of different hydrophobicities. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 138, 482–489. [CrossRef]

- Worthington, M.J.H., Kucera, R.L., Albuquerque, I.S., Gibson, C.T., Sibley, A., Slattery, A.D., Campbell, J.A., Alboaiji, S.F.K., Muller, K.A., Young, J., Adamson, N., Gascooke, J.R., Jampaiah, D., Sabri, Y.M., Bhargava, S.K., Ippolito, S.J., Lewis, D.A., Quinton, J.S., Ellis, A. V., Johs, A., Bernardes, G.J.L., Chalker, J.M. Laying Waste to Mercury: Inexpensive Sorbents Made from Sulfur and Recycled Cooking Oils. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 16219–16230. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Available online: URL https://commission.europa.eu/index_en (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- European Law portal. Available online: URL https://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html?locale=en (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- European Commission press corner. Available online: URL https://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html?locale=en (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- European Environment. Agency Available online: URL https://www.eea.europa.eu/en (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- European Chemicals Agency. Available online: URL https://echa.europa.eu/it/home (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Statista. Available online: URL https://www.statista.com/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Eurostat portal. Available online: URL https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Zhao, Yakun, Zhu, K., Li, J., Zhao, Yu, Li, S., Zhang, C., Xiao, D., Yu, A. High-efficiency production of bisabolene from waste cooking oil by metabolically engineered Yarrowia lipolytica. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 2497–2513. [CrossRef]

- Khedaywi, T., Melhem, M. Effect of Waste Vegetable Oil on Properties of Asphalt Cement and Asphalt Concrete Mixtures: An Overview. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2024, 17, 280–290. [CrossRef]

- Math, M.C., Kumar, S.P., Chetty, S. V. Technologies for biodiesel production from used cooking oil - A review. Sustain. Energy Dev. 2010, 14, 339–345. [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, G., Kanna, P.R., Taler, D., Sobota, T. Review of Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) as a Feedstock for Biofuel—Indian Perspective. Energies 2023, 16, 1739. [CrossRef]

- Matušinec, J., Hrabec, D., Šomplák, R., Nevrlý, V., Pecha, J., Smejkalová, V., Redutskiy, Y. Cooking oil and fat waste management: A review of the current state. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2020, 81, 763–768. [CrossRef]

- Monika, Banga, S., Pathak, V. V. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil: A comprehensive review on the application of heterogenous catalysts. Energy Nexus 2023, 10, 100209. [CrossRef]

- Nanda, S., Rana, R., Hunter, H.N., Fang, Z., Dalai, A.K., Kozinski, J.A. Hydrothermal catalytic processing of waste cooking oil for hydrogen-rich syngas production. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 195, 935–945. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L., Ribeiro, A., Ferreira, A., Valério, N., Pinheiro, V., Araújo, J., Vilarinho, C., Carvalho, J. Turning waste cooking oils into biofuels—valorization technologies: A review. Energies 2022, 15, 116. [CrossRef]

- Ortner, M.E., Müller, W., Schneider, I., Bockreis, A. Environmental assessment of three different utilization paths of waste cooking oil from households. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Meneses, L., Hari, A., Inayat, A., Yousef, L.A., Alarab, S., Abdallah, M., Shanableh, A., Ghenai, C., Shanmugam, S., Kikas, T. Recent advances on biodiesel production from waste cooking oil (WCO): A review of reactors, catalysts, and optimization techniques impacting the production. Fuel 2023, 348, 128514. [CrossRef]

- Tamošiūnas, A., Gimžauskaitė, D., Aikas, M., Uscila, R., Praspaliauskas, M., Eimontas, J. Gasification of Waste Cooking Oil to Syngas by Thermal Arc Plasma. Energies 2019, 12, 2612. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., Li, Y., Liao, M., Song, Q., Wang, C., Weng, J., Zhao, M., Gao, N. Catalytic pyrolysis of waste cooking oil for hydrogen-rich syngas production over bimetallic Fe-Ru/ZSM-5 catalyst. Fuel Processing Technology 2023, 247, 107812. [CrossRef]

- Sabino, J., Liborio, D.O., Arias, S., Gonzalez, J.F., Barbosa, C.M.B.M., Carvalho, F.R., Frety, R., Barros, I.C.L., Pacheco, J.G.A. Hydrogen-Free Deoxygenation of Oleic Acid and Industrial Vegetable Oil Waste on CuNiAl Catalysts for Biofuel Production. Energies 2023, 16. [CrossRef]

- Suzihaque, M.U.H., Alwi, H., Kalthum Ibrahim, U., Abdullah, S., Haron, N. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil: A brief review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 63, S490–S495. [CrossRef]

- Aransiola, E.F., Ojumu, T.V., Oyekola, O.O., Madzimbamuto, T.F., Ikhu-Omoregbe, D.I.O. A review of current technology for biodiesel production: State of the art. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 61, 276–297. [CrossRef]

- Tsoutsos, T., Tournaki, S., Gkouskos, Z., Paraíba, O., Giglio, F., García, P.Q., Braga, J., Adrianos, H., Filice, M. Quality Characteristics of Biodiesel Produced from Used Cooking Oil in Southern Europe. Chem. Eng. 2019, 3, 19. [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, C., Freire, F., Olivetti, E.A., Kirchain, R., Dias, L.C. Analysis of cost-environmental trade-offs in biodiesel production incorporating waste feedstocks: A multi-objective programming approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 64–73. [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Ravelo, V., Schallenberg-Rodriguez, J. Biodiesel production as a solution to waste cooking oil (WCO) disposal. Will any type of WCO do for a transesterification process? A quality assessment. J. Environ. Manage 2018, 228, 117–129. [CrossRef]

- Cadillo-Benalcazar, J.J., Bukkens, S.G.F., Ripa, M., Giampietro, M. Why does the European Union produce biofuels? Examining consistency and plausibility in prevailing narratives with quantitative storytelling. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101810. [CrossRef]

- Outili, N., Kerras, H., Meniai, A.H. Recent conventional and non-conventional WCO pretreatment methods: Implementation of green chemistry principles and metrics. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 41, 100794. [CrossRef]

- Ripa, M., Cadillo-Benalcazar, J.J., Giampietro, M. Cutting through the biofuel confusion: A conceptual framework to check the feasibility, viability and desirability of biofuels. Energy Strategy Reviews 2021, 35, 100642. [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, C., Queirós, J., Freire, F. Biodiesel from Waste Cooking Oils in Portugal: Alternative Collection Systems. Waste Biomass Valorization 2015, 6, 771–779. [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2023/2413, 2023. Amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and Directive 98/70/EC as regards the promotion of energy from renewable sources, and repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652, European Parliament and of the Council. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2023/2413/oj. (accessed 03.08.2024).

- Directive 75/439/EEC, 1975. Disposal of waste oils, The council of the European communities. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/1975/439/oj. (accessed 20.09.2024).

- Directive 2014/955/EU, 2014. Commission Decision of 18 December 2014 amending Decision 2000/532/EC on the list of waste pursuant to Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council Text with EEA relevance, European Parliament and of the Council . http://data.europa.eu/eli/dec/2014/955/oj. (accessed 03.02.2024).

- Directive 75/442/EEC, 1975. Council Directive 75/442/EEC of 15 July 1975 on waste, The council of the european communities. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/1975/442/oj. (accessed 15.10.2024).

- Directive 2008/98/EC, 2008. Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on waste and repealing certain Directives (Text with EEA relevance), European Parliament and of the Council . http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/98/oj. (accessed 25.12.2024).

- Directive (EU) 2018/851, 2018. Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive 2008/98/EC on waste (Text with EEA relevance), European Parliament and of the Council. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/851/oj. (accessed 03.12.2024).

- Borrello, M., Caracciolo, F., Lombardi, A., Pascucci, S., Cembalo, L. Consumers’ Perspective on Circular Economy Strategy for Reducing Food Waste. Sustainability 2017, 9, 141. [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, V., Bardella, N., Samiolo, R., Gatto, V., Conca, S., Sole, R., Molin, G., Gattolin, A., Ongaro, N. By-products from mechanical recycling of polyolefins improve hot mix asphalt performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128627. [CrossRef]

- CONOE Annual Report 2018. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=http://www.conoe.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/ANNUAL-REPORT-2018.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiB-v_3touIAxVJ8LsIHS8kAKAQFnoECBUQAQ&usg=AOvVaw0pNXsTRFSIaiWl9aUnWgPQ (accessed 23.11.2024).

- De Feo, G., Di Domenico, A., Ferrara, C., Abate, S., Sesti Osseo, L. Evolution of Waste Cooking Oil Collection in an Area with Long-Standing Waste Management Problems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8578. [CrossRef]

- De Feo, G., Ferrara, C., Giordano, L., Ossèo, L.S. Assessment of Three Recycling Pathways for Waste Cooking Oil as Feedstock in the Production of Biodiesel, Biolubricant, and Biosurfactant: A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Approach. Recycling 2023, 8, 64. [CrossRef]

- Foo, W.H., Koay, S.S.N., Tang, D.Y.Y., Chia, W.Y., Chew, K.W., Show, P.L. Safety control of waste cooking oil: transforming hazard into multifarious products with available pre-treatment processes. Food Mater. Res. 2022, 2, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Bazina, N., He, J. Analysis of fatty acid profiles of free fatty acids generated in deep-frying process. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3085–3092. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-M., Kim, J.-M. Monitoring of Used Frying Oils and Frying Times for Frying Chicken Nuggets Using Peroxide Value and Acid Value. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2016, 36, 612–616. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.G., Dalai, A.K. Waste Cooking OilAn Economical Source for Biodiesel: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 2901–2913. [CrossRef]

- Awogbemi, O., Kallon, D.V. Von, Aigbodion, V.S., Panda, S. Advances in biotechnological applications of waste cooking oil. CSCEE 2021, 4, 100158. [CrossRef]

- Fabiszewska, U.A., Białecka-Florjańczyk, E. Factors influencing synthesis of extracellular lipases by yarrowia lipolytica in medium containing vegetable oils. J. microbiol., biotechnol. food sci. 2014, 4, 231–237. [CrossRef]

- Liepins, J., Balina, K., Soloha, R., Berzina, I., Lukasa, L.K., Dace, E. Glycolipid biosurfactant production from waste cooking oils by yeast: Review of substrates, producers and products. Fermentation 2021, 7, 136. [CrossRef]

- Wadekar, S., Kale, S., Lali, A., Bhowmick, D., Pratap, A. Sophorolipid Production by Starmerella bombicola (ATCC 22214) from Virgin and Waste Frying Oils, and the Effects of Activated Earth Treatment of the Waste Oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2012, 89, 1029–1039. [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Cabello, M., Sáez-Bastante, J., Pinzi, S., Dorado, M.P. Optimization of solid food waste oil biodiesel by ultrasound-assisted transesterification. Fuel 2019, 255, 115817. [CrossRef]

- EN 14214. International standard that describes the minimum requirements for Biodiesel production from vegetable oils. https://www.chemeurope.com/en/encyclopedia/EN_14214.html. (Accessed 08.23.2024).

- Hussein, R.Z.K., Attia, N.K., Fouad, M.K., ElSheltawy, S.T. Experimental investigation and process simulation of biolubricant production from waste cooking oil. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 144, 105850. [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.-Y., Ma, C., Qin, W.-Q., Mtui, H.I., Wang, W., Liu, J., Yang, S.-Z., Mu, B.-Z. A synergetic binary system of waste cooking oil-derived bio-based surfactants and its interfacial performance for enhanced oil recovery. Colloids and Surfaces C: Environmental Aspects 2024, 2, 100039. [CrossRef]

- Jia, P., Zhang, M., Hu, L., Song, F., Feng, G., Zhou, Y. A Strategy for Nonmigrating Plasticized PVC Modified with Mannich base of Waste Cooking Oil Methyl Ester. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.H., Botelho, B.G., Oliveira, L.S., Franca, A.S. Sustainable synthesis of epoxidized waste cooking oil and its application as a plasticizer for polyvinyl chloride films. Eur. Polym J. 2018, 99, 142–149. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T., Wu, Z., Xie, Q., Fang, J., Hu, Y., Lu, M., Xia, F., Nie, Y., Ji, J. Structural modification of waste cooking oil methyl esters as cleaner plasticizer to substitute toxic dioctyl phthalate. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 1021–1030. [CrossRef]

- Moretti, C., Junginger, M., Shen, L. Environmental life cycle assessment of polypropylene made from used cooking oil. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 157, 104750. [CrossRef]

- Tremblay-Parrado, K.K., Astrain, C. G., Avérous, L. click chemistry for the synthesis of biobased polymers and networks derived from vegetable oils. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 4296–4327. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Huo, Y., Su, Q., Lu, D., Wu, Y., Dong, X., Gao, Y. Sustainable high-strength alkali-activated slag concrete is achieved by recycling emulsified waste cooking oil. Front Mater. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ingrassia, L.P., Lu, X., Ferrotti, G., Canestrari, F. Renewable materials in bituminous binders and mixtures: Speculative pretext or reliable opportunity? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 144, 209–222. [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, K.D., Dokandari, A.P., Raufi, H., Topal, A., Sengoz, B. Feasibility and mixture performance assessment of waste oil based rejuvenators in high-RAP asphalt mixtures. Mater. Res. Express 2023, 10, 045306. [CrossRef]

- Sun, D., Lu, T., Xiao, F., Zhu, X., Sun, G. Formulation and aging resistance of modified bio-asphalt containing high percentage of waste cooking oil residues. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 1203–1214. [CrossRef]

- Straits research, 2024. Bio-Lubricants Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Base Oil Type (Vegetable Oils, Animal Fats), By Application (Chainsaw Oils, Hydraulic Fluids), By End-User (Industrial, Commercial Transport, Passenger Vehicles ) and By Region(North America, Europe, APAC, Middle East and Africa, LATAM) Forecasts, 2023-2031 [WWW Document]. https://straitsresearch.com/report/bio-lubricants-market#:~:text=The%20global%20bio%2Dlubricants%20market,the%20forecast%20period%202023%2D2031 (accessed 8.19.24).

- Joshi, J.R., Bhanderi, K.K., Patel, J. V. Waste cooking oil as a promising source for bio lubricants- A review. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2023, 100, 100820. [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi, M.R., Malpartida, I., Tsang, C.-W., Lin, C.S.K., Len, C. Recent advances on the catalytic conversion of waste cooking oil. Molecular Catal. 2020, 494, 111128. [CrossRef]

- Kutluk, B.G., Kutluk, T., Kapucu, N. Enzymatic Synthesis of Trimethylolpropane-Bases Biolubricants from Waste Edible Oil Biodiesel Using Different Types of Biocatalysis. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng 2022, 41, 3234–3243. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S., Chandar, T., Pradhan, S., Prasad, L. Lubricant from Waste Cooking Oil, in: Lubricants from Renewable Feedstocks. Wiley, 2024, pp. 291–335. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Ji, H., Song, Y., Ma, S., Xiong, W., Chen, C., Chen, B., Zhang, X. Green preparation of branched biolubricant by chemically modifying waste cooking oil with lipase and ionic liquid. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122918. [CrossRef]

- Borugadda, V.B., Goud, V. V. Improved thermo-oxidative stability of structurally modified waste cooking oil methyl esters for bio-lubricant application. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 4515–4524. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A., Mitra, D., Biswas, D. Biolubricant synthesis from waste cooking oil via enzymatic hydrolysis followed by chemical esterification. JCTB 2023, 88, 139–144. [CrossRef]

- Dabai, U.M., Owuna, J.F., Sokoto, A.M., Abubakar, L.A. Assessment of Quality Parameters of Ecofriendly Biolubricant from Waste Cooking Palm Oil. Asian J. Applied Chemistry Research 2018, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Bahadi, M., Salimon, J., Derawi, D. Synthesis of di-trimethylolpropane tetraester-based biolubricant from Elaeis guineensis kernel oil via homogeneous acid-catalyzed transesterification. Renew. Energy 2021, 171, 981–993. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, W.C.A., Luiz, J.H.H., Fernandez-Lafuente, R., Hirata, D.B., Mendes, A.A. Eco-friendly production of trimethylolpropane triesters from refined and used soybean cooking oils using an immobilized low-cost lipase (Eversa>® Transform 2.0) as heterogeneous catalyst. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 155, 106302. [CrossRef]

- Ivan-Tan, C.T., Islam, A., Yunus, R., Taufiq-Yap, Y.H. Screening of solid base catalysts on palm oil based biolubricant synthesis. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 441–451. [CrossRef]

- Owuna, F.J., Dabai, M.U., Sokoto, M.A., Dangoggo, S.M., Bagudo, B.U., Birnin-Yauri, U.A., Hassan, L.G., Sada, I., Abubakar, A.L., Jibrin, M.S. Chemical modification of vegetable oils for the production of biolubricants using trimethylolpropane: A review. Egypt. J. Pet. 2020, 29, 75–82. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Liu, M.Y., Fan, X.G., Wang, L., Liang, J.Y., Jin, X.Y., Che, R.J., Ying, W.Y., Chen, S.P. 4D printing of multifunctional photocurable resin based on waste cooking oil. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 16344-16358.

- Wang, E., Ma, X., Tang, S., Yan, R., Wang, Y., Riley, W.W., Reaney, M.J.T. Synthesis and oxidative stability of trimethylolpropane fatty acid triester as a biolubricant base oil from waste cooking oil. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 66, 371–378. [CrossRef]

- Lakkoju, B., Vemulapalli, V. Synthesis and characterization of triol based bio-lubricant from waste cooking oil. AIP Conference proceedings 2020, 2297, p. 020002. [CrossRef]

- Bashiri, S., Ghobadian, B., Dehghani Soufi, M., Gorjian, S. Chemical modification of sunflower waste cooking oil for biolubricant production through epoxidation reaction. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2021, 4, 119–127. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Wang, X. Bio-lubricants derived from waste cooking oil with improved oxidation stability and low-temperature properties. J. Oleo. Sci. 2015, 64, 367–374. [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, H., Adhikari, S., Roy, P., Shelley, M., Hassani, E., Oh, T.-S. Synthesis of Novel Biolubricants from Waste Cooking Oil and Cyclic Oxygenates through an Integrated Catalytic Process. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 13424–13437. [CrossRef]

- Turco, R., Tesser, R., Vitiello, R., Russo, V., Andini, S., Serio, M. Di. Synthesis of Biolubricant Basestocks from Epoxidized Soybean Oil. Catalysts 2017, 7, 309. [CrossRef]

- Borah, M.J., Das, A., Das, V., Bhuyan, N., Deka, D. Transesterification of waste cooking oil for biodiesel production catalyzed by Zn substituted waste egg shell derived CaO nanocatalyst. Fuel 2019, 242, 345–354. [CrossRef]

- Ghafar, F., Sapawe, N., Dzazita Jemain, E., Safwan Alikasturi, A., Masripan, N. Study on The Potential of Waste Cockle Shell Derived Calcium Oxide for Biolubricant Production. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 19, 1346–1353. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J.R., Miranda, L.P., Fernandez-Lafuente, R., Tardioli, P.W. Immobilization of Eversa® Transform via CLEA Technology Converts It in a Suitable Biocatalyst for Biolubricant Production Using Waste Cooking Oil. Molecules 2021, 26, 193. [CrossRef]

- Sarno, M., Iuliano, M., Cirillo, C. Optimized procedure for the preparation of an enzymatic nanocatalyst to produce a bio-lubricant from waste cooking oil. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 377, 120273. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y., Lin, H., Zhang, S., Yang, Z., Yuan, T. One-Step Synthesis of Novel Renewable Vegetable Oil-Based Acrylate Prepolymers and Their Application in UV-Curable Coatings. Polymers 2020, 12, 1165. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A., Kuching Sarawak, P., Hafizah Naihi, M. Analysis of Produced Bio-Surfactants from Waste Cooking Oil and Pure Coconut. IJISRT 2019, 4, 682–685. ISSN 2456-2165.

- De, S., Malik, S., Ghosh, A., Saha, R., Saha, B. A review on natural surfactants. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 65757–65767. [CrossRef]

- Inès, M., Dhouha, G. Glycolipid biosurfactants: Potential related biomedical and biotechnological applications. Carbohydr. Res. 2015, 416, 59–69. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y., To, M.H., Siddiqui, M.A., Wang, H., Lodens, S., Chopra, S.S., Kaur, G., Roelants, S.L.K.W., Lin, C.S.K. Sustainable biosurfactant production from secondary feedstock—recent advances, process optimization and perspectives. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, N., Alam, P., Bhonsle, A.K., Ngomade, S.B.L., Agarwal, T., Singh, R.K., Atray, N. Valorization of used cooking oil into bio-based surfactant: modeling and optimization using response surface methodology. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Q., Cai, B.X., Xu, W.J., Gang, H.Z., Liu, J.F., Yang, S.Z., Mu, B.Z. The rebirth of waste cooking oil to novel bio-based surfactants. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5. [CrossRef]

- Market Research Engine, 2022. Biosurfactants Market Research. Available on line URL https://www.marketresearchengine.com/biosurfactants-market?srsltid=AfmBOopWbMrQRk5GEZTHLe-xSaQJk4fBT84YEX_zBlJ5Rqe64EyXE1tJ (accessed 08.12.2024).

- Jahan, R., Bodratti, A.M., Tsianou, M., Alexandridis, P. Biosurfactants, natural alternatives to synthetic surfactants: Physicochemical properties and applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 275, 102061. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Peñalver, P., Koh, A., Gross, R., Gea, T., Font, X. Biosurfactants from Waste: Structures and Interfacial Properties of Sophorolipids Produced from a Residual Oil Cake. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2020, 23, 481–486. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K., Toor, S.S., Brandão, J., Pedersen, T.H., Rosendahl, L.A. Optimized conversion of waste cooking oil into ecofriendly bio-based polymeric surfactant- A solution for enhanced oil recovery and green fuel compatibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294. [CrossRef]

- Cameotra, S.S., Makkar, R.S. Biosurfactant-enhanced bioremediation of hydrophobic pollutants. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 82, 97–116. [CrossRef]

- Gaur, V.K., Sharma, P., Sirohi, R., Varjani, S., Taherzadeh, M.J., Chang, J.-S., Yong Ng, H., Wong, J.W.C., Kim, S.-H. Production of biosurfactants from agro-industrial waste and waste cooking oil in a circular bioeconomy: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126059. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, K., Sharma, P., Gaur, V.K., Gupta, P., Pandey, U., Varjani, S., Pandey, A., Wong, J.W.C., Chang, J.S. Oily waste to biosurfactant: A path towards carbon neutrality and environmental sustainability. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 30. [CrossRef]

- Nurdin, S., Yunus, R.M., Nour, A.H., Gimbun, J., Aisyah Azman, N.N., Sivaguru, M. V. Restoration of waste cooking oil (WCO) using alkaline hydrolysis technique (ALHYT) for future biodetergent 11. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2016, 11, 6405–6410. ISSN 1819-6608.

- Yusuff, A.S., Porwal, J., Bhonsle, A.K., Rawat, N., Atray, N. Valorization of used cooking oil as a source of anionic surfactant fatty acid methyl ester sulfonate: process optimization and characterization studies. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 8903–8914. [CrossRef]

- Permadani, R.L., Ibadurrohman, M., Slamet. Utilization of waste cooking oil as raw material for synthesis of Methyl Ester Sulfonates (MES) surfactant, in: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Institute of Physics Publishing 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., Tian, S., Guo, J., Ren, X., Li, X., Gao, S. Synthesis, Characterization and Exploratory Application of Anionic Surfactant Fatty Acid Methyl Ester Sulfonate from Waste Cooking Oil. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2016, 19, 467–475. [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, M.G., Paolotti, L., Rocchi, L., Boggia, A. The Role of Environmental Evaluation within Circular Economy: An Application of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Method in the Detergents Sector. Environ. Climate Technol. 2019, 23, 238–257. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q., Li, X., Dong, J. Synthesis of branched surfactant via ethoxylation of oleic acid derivative and its surface properties. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 258, 117747. [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, M.M., Tantawy, A.H., Soliman, K.A., Abd El-Lateef, H.M. Cationic gemini-surfactants based on waste cooking oil as new ‘green’ inhibitors for N80-steel corrosion in sulphuric acid: A combined empirical and theoretical approaches. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1203, 127442. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Hernández, L., Meléndez-Ortiz, H.I., Cortez-Mazatan, G.Y., Vaillant-Sánchez, S., Peralta-Rodríguez, R.D. Gemini and Bicephalous Surfactants: A Review on Their Synthesis, Micelle Formation, and Uses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1798. [CrossRef]

- Bocqué, M., Voirin, C., Lapinte, V., Caillol, S., Robin, J.J. Petro-based and bio-based plasticizers: Chemical structures to plasticizing properties. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2016, 54, 11–33. [CrossRef]

- Silviana, Anggoro, D.D., Kumoro, A.C. Waste cooking oil utilisation as bio-plasticiser through epoxidation using inorganic acids as homogeneous catalysts. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 56, 1861–1866. [CrossRef]

- Carlos, K.S., de Jager, L.S., Begley, T.H. Investigation of the primary plasticisers present in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) products currently authorised as food contact materials. Food Addit. 2018, 35, 1214–1222. [CrossRef]

- Friday Etuk, I., Ekwere Inyang, U. Applications of Various Plasticizers in the Plastic Industry-Review. IJEMT 2024, 10, 38–55.

- Greco, A., Ferrari, F., Maffezzoli, A. UV and thermal stability of soft PVC plasticized with cardanol derivatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 757–764. [CrossRef]

- He, Z., Lu, Y., Lin, C., Jia, H., Wu, H., Cao, F., Ouyang, P. Designing anti-migration furan-based plasticizers and their plasticization properties in poly (vinyl chloride) blends. Polym. Test 2020, 91, 106793. [CrossRef]

- Sahnoune Millot, M., Devémy, J., Chennell, P., Pinguet, J., Dequidt, A., Sautou, V., Malfreyt, P. Leaching of plasticizers from PVC medical devices: A molecular interpretation of experimental migration data. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 396, 123965. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y., Miao, D., Kong, L., Jiang, J., Guo, Z. Preparation and Performance Test of the Super-Hydrophobic Polyurethane Coating Based on Waste Cooking Oil. Coatings 2019, 9, 861. [CrossRef]

- Feng, G., Ma, Y., Zhang, M., Jia, P., Liu, C., Zhou, Y. Synthesis of Bio-base Plasticizer Using Waste Cooking Oil and Its Performance Testing in Soft Poly(vinyl chloride) Films. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2019, 4, 99–110. [CrossRef]

- Jia, P., Ma, Y., Kong, Q., Xu, L., Hu, Y., Hu, L., Zhou, Y. Graft modification of polyvinyl chloride with epoxidized biomass-based monomers for preparing flexible polyvinyl chloride materials without plasticizer migration. Mater. Today Chem. 2019, 13, 49–58. [CrossRef]

- Thirupathiah, G., Satapathy, S., Palanisamy, A. Studies on epoxidised castor oil as co-plasticizer with epoxidised soyabean oil for PVC processing. J. Renew. Mater. 2019, 7, 775–785. [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.-L., Yue, X., Hao, B., Ma, P.-C. A sustainable poly(vinyl chloride) plasticizer derivated from waste cooking oil. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122781. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Jiang, P., Nie, Z., Wang, H., Dai, Z., Deng, J., Cao, Z. Synthesis of an efficient bio-based plasticizer derived from waste cooking oil and its performance testing in PVC. Polym. Test 2020, 90, 106625. [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.-X., Yin, G.-Z., Ye, W., Jiang, Y., Wang, N., Wang, D.-Y. Exploiting Waste towards More Sustainable Flame-Retardant Solutions for Polymers: A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 2266. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J., Zhang, S., Lu, T., Li, R., Zhong, T., Zhu, X. Design and synthesis of ethoxylated esters derived from waste frying oil as anti-ultraviolet and efficient primary plasticizers for poly(vinyl chloride). J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 1274–1282. [CrossRef]

- Polaczek, K., Kurańska, M., Auguścik-Królikowska, M., Prociak, A., Ryszkowska, J. Open-cell polyurethane foams of very low density modified with various palm oil-based bio-polyols in accordance with cleaner production. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125875. [CrossRef]

- Gadhave, R. V., Mahanwar, P.A., Gadekar, P.T. Bio-Renewable Sources for Synthesis of Eco-Friendly Polyurethane Adhesives—Review. Open J. Polym. Chem. 2017, 7, 57–75. [CrossRef]

- Sarim, M., Alavi Nikje, M.M., Dargahi, M. Preparation and Characterization of Polyurethane Rigid Foam Nanocomposites from Used Cooking Oil and Perlite. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Mangal, M., Rao, C.V., Banerjee, T. Bioplastic: an eco-friendly alternative to non-biodegradable plastic. Polym Int. 2023, 72, 984–996. [CrossRef]

- Orjuela, A., Clark, J. Green chemicals from used cooking oils: Trends, challenges, and opportunities. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 26, 100369. [CrossRef]

- Salleh, W.N.F.W., Tahir, S.M., Mohamed, N.S. Synthesis of waste cooking oil-based polyurethane for solid polymer electrolyte. Polymer Bulletin 2018, 75, 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Sawpan, M.A. Polyurethanes from vegetable oils and applications: a review. J. Polym. Res. 2018, 25, 184. [CrossRef]

- Delavarde, A., Savin, G., Derkenne, P., Boursier, M., Morales-Cerrada, R., Nottelet, B., Pinaud, J., Caillol, S. Sustainable polyurethanes: toward new cutting-edge opportunities. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2024, 151, 101805. [CrossRef]

- Maulana, S., Wibowo, E.S., Mardawati, E., Iswanto, A.H., Papadopoulos, A., Lubis, M.A.R. Eco-Friendly and High-Performance Bio-Polyurethane Adhesives from Vegetable Oils: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1613. [CrossRef]

- Paciorek-Sadowska, J., Borowicz, M., Isbrandt, M., Czupryński, B., Apiecionek, Ł. The Use of Waste from the Production of Rapeseed Oil for Obtaining of New Polyurethane Composites. Polymers 2019, 11, 1431. [CrossRef]

- Pu, M., Fang, C., Zhou, X., Wang, D., Lin, Y., Lei, W., Li, L. Recent Advances in Environment-Friendly Polyurethanes from Polyols Recovered from the Recycling and Renewable Resources: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1889. [CrossRef]

- Asare, M.A., de Souza, F.M., Gupta, R.K. Waste to Resource: Synthesis of Polyurethanes from Waste Cooking Oil. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 18400–18411. [CrossRef]

- Kurańska, M., Banaś, J., Polaczek, K., Banaś, M., Prociak, A., Kuc, J., Uram, K., Lubera, T. Evaluation of application potential of used cooking oils in the synthesis of polyol compounds. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103506. [CrossRef]

- Malewska, E., Polaczek, K., Kurańska, M. Impact of Various Catalysts on Transesterification of Used Cooking Oil and Foaming Processes of Polyurethane Systems. Materials 2022, 15, 7807. [CrossRef]

- Raofuddin, D.N.A., Azmi, I.S., Jalil, M.J. Catalytic Epoxidation of Oleic Acid Derived from Waste Cooking Oil by In Situ Peracids. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 803–814. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, B.S., Benitez, B., Querini, C.A., Mendow, G. Transesterification of sunflower oil with ethanol using sodium ethoxide as catalyst. Effect of the reaction conditions. Fuel Processing Technology 2015, 131, 29–35. [CrossRef]

- Kurańska, M., Malewska, E. Waste cooking oil as starting resource to produce bio-polyol - analysis of transesteryfication process using gel permeation chromatography. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 162, 113294. [CrossRef]

- Kurańska, M., Benes, H., Polaczek, K., Trhlikova, O., Walterova, Z., Prociak, A. Effect of homogeneous catalysts on ring opening reactions of epoxidized cooking oils. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 162–169. [CrossRef]

- Skleničková, K., Abbrent, S., Halecký, M., Kočí, V., Beneš, H. Biodegradability and ecotoxicity of polyurethane foams: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 157–202. [CrossRef]

- Haq, I. ul, Akram, A., Nawaz, A., Zohu, X., Abbas, S.Z., Xu, Y., Rafatullah, M. Comparative analysis of various waste cooking oils for esterification and transesterification processes to produce biodiesel. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2021, 462–473. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, D., Velasco, M., Malagón-Romero, D. Production of polyurethanes from used vegetable oil-based polyols. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2020, 79, 337–342. [CrossRef]

- Lubis, M., Prayogo, M.A., Harahap, M.B., Iriany, Ginting, M.H.S., Lazuardi, I.N., Akbar, R. The effect of fibre loading on characterization and mechanical properties of polyurethane foam composites derived waste cooking oil, polyol and toluene diisocyanate with adding filler sugar palm (Arenga pinnata) fibre. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1122, 012109. [CrossRef]

- Paraskar, P.M., Prabhudesai, M.S., Hatkar, V.M., Kulkarni, R.D. Vegetable oil based polyurethane coatings – A sustainable approach: A review. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 156, 106267. [CrossRef]

- Silva, R., Barros-Timmons, A., Quinteiro, P. Life cycle assessment of fossil- and bio-based polyurethane foams: a review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139697. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Osma, J.A., Martínez, J., de la Cruz-Martínez, F., Caballero, M.P., Fernández-Baeza, J., Rodríguez-López, J., Otero, A., Lara-Sánchez, A., Tejeda, J. Development of hydroxy-containing imidazole organocatalysts for CO2 fixation into cyclic carbonates. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 1981–1987. [CrossRef]

- Werlinger, F., Caballero, M.P., Trofymchuk, O.S., Flores, M.E., Moreno-Villoslada, I., Cruz-Martínez, F. de la, Castro-Osma, J.A., Tejeda, J., Martínez, J., Lara-Sánchez, A. Turning waste into resources. Efficient synthesis of biopolyurethanes from used cooking oils and CO2. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 79, 102659. [CrossRef]

- Onn, M., Mustafa, H., Azman, H.A., Ahmad, Z., Wahit, M.U. Synthesis and Characterization of Photocrosslinkable Acrylic Prepolymers from Waste Palm Frying Oil. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2023, 106, 379–384. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B., Sufi, A., Ghosh Biswas, R., Hisatsune, A., Moxley-Paquette, V., Ning, P., Soong, R., Dicks, A.P., Simpson, A.J. Direct Conversion of McDonald’s Waste Cooking Oil into a Biodegradable High-Resolution 3D-Printing Resin. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 1171–1177. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W., Deng, X., Tian, S., Wang, S., He, Y., Zheng, B., Xin, K., Zhou, Z., Tang, L. Whole-Waste synthesis of Kilogram-Scale Macropores adsorbent materials for Wide-Range oil and heavy metal removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 128750. [CrossRef]

- Voet, V.S.D., Guit, J., Loos, K. Sustainable Photopolymers in 3D Printing: A Review on Biobased, Biodegradable, and Recyclable Alternatives. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2021, 42. [CrossRef]

- Heriyanto, H., Suhendi, E., Asyuni, N.F., Shahila, I.K. Effect of Bayah natural zeolite for purification of waste cooking oil as feedstock of alkyd resin. Teknika: Jurnal. Sains dan Teknologi. 2022, 18, 49. [CrossRef]

- Silvianti, F., Wijayanti, W., Sudjarwo, W.A.A., Dewi, W.B. Synthesis of Alkyd Resin Modified with Waste Palm Cooking Oil as Precursor Using Pretreatment with Zeolite Adsorbent. Sci. Technol. Indonesia 2018, 3, 119–122. [CrossRef]

- Markets and Markets, 2024. Epoxy resin market by physical form, raw materilas, application, end-use industry and region- global forecast to 2028. https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/epoxy-resins-market-762.html.

- Jaengmee, T., Pongmuksuwan, P., Kitisatorn, W. Development of bio-based epoxy resin from palm oil. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 52, 2357–2360. [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.L., Lai, J.C., Rahman, R.A., Adrus, N., Al-Saffar, Z.H., Hassan, A., Lim, T.H., Wahit, M.U. A review on recent approaches to sustainable bio-based epoxy vitrimer from epoxidized vegetable oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 189, 115857. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.A.M.M., Santos, M., Cernadas, T., Ferreira, P., Alves, P. Advances in the development of biobased epoxy resins: insight into more sustainable materials and future applications. Int. Mater. Rev. 2022, 119–149. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.C., Kirwan, K., Wilson, P.R., Coles, S.R. Sustainable Alternative Composites Using Waste Vegetable Oil Based Resins. J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 2464–2477. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Pei, Q., Li, K., Wang, Zhonghui, Huo, X., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., Kong, S. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the Rejuvenation Performance of Waste Cooking Oil with High Acid Value on Aged Asphalt. Molecules 2024, 29, 2830. [CrossRef]

- Xu, N., Wang, Hainian, Wang, Huimin, Kazemi, M., Fini, E. Research progress on resource utilization of waste cooking oil in asphalt materials: A state-of-the-art review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135427. [CrossRef]

- Baranowska, W., Rzepna, M., Ostrowski, P., Lewandowska, H. Radiation and Radical Grafting Compatibilization of Polymers for Improved Bituminous Binders—A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 1642. [CrossRef]

- Chamaa, A., Khatib, J., Elkordi, A. A review on the use of vegetable oil and its waste in construction applications. BAU Journal - Science and Technology 2020, 1. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, M., Kavitha Kathikeyan, S., Snekha, G., Vinothini, A. Experimental Investigation on Usage of Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) in Concrete Making and Adopting Innovative Curing Method. International Journal of Engineering Research and V5 2016. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S., Chandrappa, A.K. Influence of Blended Waste Cooking Oils on the Sustainable Asphalt Rejuvenation Considering Secondary Aging. International Journal of Pavement Research and Technology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Uz, V.E., Gökalp, İ. Sustainable recovery of waste vegetable cooking oil and aged bitumen: Optimized modification for short and long term aging cases. Waste Management 2020, 110, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Su, J., Liu, L., Liu, Z., Sun, G. Waste cooking oil based capsules for sustainable self-healing asphalt pavement: Encapsulation, characterization and fatigue-healing performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 136032. [CrossRef]

- Ji, H., Li, B., Li, X., Han, J., Liu, D., Dou, H., Fu, M., Yao, T. Waste cooking oil as a sustainable solution for UV-aged asphalt binder: Rheological, chemical and molecular structure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 420, 135149. [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A. Al, Wahhab, H.I.A.-A., Dalhat, M.A. Comparative laboratory evaluation of waste cooking oil rejuvenated asphalt concrete mixtures for high contents of reclaimed asphalt pavement. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2020, 21, 1297–1308. [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, H., Noorian, F. Laboratory investigation on the properties of asphalt concrete containing reclaimed asphalt pavement and waste cooking oil as recycling agent. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2021, 22, 539–549. [CrossRef]

- Al-Omari, A.A., Khedaywi, T.S., Khasawneh, M.A. Laboratory characterization of asphalt binders modified with waste vegetable oil using SuperPave specifications. Int. J. Pavement Res. Techn. 2018, 11, 68–76. [CrossRef]

- Jalkh, R., El-Rassy, H., Chehab, G.R., Abiad, M.G. Assessment of the Physico-Chemical Properties of Waste Cooking Oil and Spent Coffee Grounds Oil for Potential Use as Asphalt Binder Rejuvenators. Waste Biomass Valorization 2018, 9, 2125–2132. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.B., Hossain, K. Waste cooking oil as an asphalt rejuvenator: A state-of-the-art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 230, 116985. [CrossRef]

- Elahi, Z., Mohd Jakarni, F., Muniandy, R., Hassim, S., Ab Razak, M.S., Ansari, A.H., Ben Zair, M.M. Waste Cooking Oil as a Sustainable Bio Modifier for Asphalt Modification: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11506. [CrossRef]

- Elahi, Z., Jakarni, F.M., Muniandy, R., Hassim, S., Ab Razak, M.S., Ansari, A.H. Influence of novel modified waste cooking oil beads on rheological characteristics of bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 414, 134829. [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, M., Nizamuddin, S., Madapusi, S., Giustozzi, F. Sustainable asphalt rejuvenation using waste cooking oil: A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123304. [CrossRef]

- Alkuime, H., Kassem, E., Alshraiedeh, K.A., Bustanji, M., Aleih, A., Abukhamseh, F. Performance Assessment of Waste Cooking Oil-Modified Asphalt Mixtures. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 1228. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Xiao, F., Putman, B., Leng, B., Wu, S. High temperature properties of rejuvenating recovered binder with rejuvenator, waste cooking and cotton seed oils. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 59, 10–16. [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y., Dong, X., Gao, Y., Xu, X., Zeng, L., Wu, Y., Zhao, Y., Yang, Y., Su, Q., Huang, J., Lu, D. Effects of cooking oil on the shrinkage-reducing of high-strength concrete. Results in Materials 2024, 23, 100602. [CrossRef]

- Joni, H.H., Al-Rubaee, R.H.A., Al-zerkani, M.A. Rejuvenation of aged asphalt binder extracted from reclaimed asphalt pavement using waste vegetable and engine oils. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2019, 11, e00279. [CrossRef]

- Xinxin, C., Xuejuan, C., Boming, T., Yuanyuan, W., Xiaolong, L. Investigation on Possibility of Waste Vegetable Oil Rejuvenating Aged Asphalt. Applied Sciences 2018, 8, 765. [CrossRef]

- Azahar, W.N.A.W., Jaya, R.P., Hainin, M.R., Bujang, M., Ngadi, N. Mechanical performance of asphaltic concrete incorporating untreated and treated waste cooking oil. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 150, 653–663. [CrossRef]

- Oldham, D., Rajib, A., Dandamudi, K.P.R., Liu, Y., Deng, S., Fini, E.H. Transesterification of Waste Cooking Oil to Produce A Sustainable Rejuvenator for Aged Asphalt. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2021, 168, 105297. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z., Yi, J., Huang, Y., Feng, D., Guo, C. Properties of asphalt binder modified by bio-oil derived from waste cooking oil. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 102, 496–504. [CrossRef]

- Enfrin, M., Gowda, A., Giustozzi, F. Low-cost chemical modification of refined used cooking oil to produce long-lasting bio-asphalt pavements. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 204, 107493. [CrossRef]

- Yi, X., Dong, R., Shi, C., Yang, J., Leng, Z. The influence of the mass ratio of crumb rubber and waste cooking oil on the properties of rubberised bio-rejuvenator and rejuvenated asphalt. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2023, 24, 578–591. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Yu, Z., Lv, C., Meng, F., Yang, Y. Preparation of waste cooking oil emulsion as shrinkage reducing admixture and its potential use in high performance concrete: Effect on shrinkage and mechanical properties. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101488. [CrossRef]

- Tarnpradab, T., Unyaphan, S., Takahashi, F., Yoshikawa, K. Tar removal capacity of waste cooking oil absorption and waste char adsorption for rice husk gasification. Biofuels 2016, 7, 401–412. [CrossRef]

- Cappello, M., Brunazzi, E., Rossi, D., Seggiani, M. Absorption of n-butyl acetate from tannery air emissions by waste vegetable oil/water emulsions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112443. [CrossRef]

- Dong, R., Zhao, M., Tang, N. Characterization of crumb tire rubber lightly pyrolyzed in waste cooking oil and the properties of its modified bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 195, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Aldagari, S., Kabir, S.F., Lamanna, A., Fini, E.H. Functionalized Waste Plastic Granules to Enhance Sustainability of Bituminous Composites. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 183, 106353. [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, M., Fini, E.H. Preventing emissions of hazardous organic compounds from bituminous composites. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 344, 131067. [CrossRef]

- Yi, X., Dong, R., Tang, N. Development of a novel binder rejuvenator composed by waste cooking oil and crumb tire rubber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 236, 117621. [CrossRef]

- Gallart-Sirvent, P., Martín, M., Villorbina, G., Balcells, M., Solé, A., Barrenche, C., Cabeza, L.F., Canela-Garayoa, R. Fatty acid eutectic mixtures and derivatives from non-edible animal fat as phase change materials. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 24133–24139. [CrossRef]

- Kahwaji, S., White, M.A. Edible Oils as Practical Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 1627. [CrossRef]

- Afonso, I.S., Nobrega, G., Lima, R., Gomes, J.R., Ribeiro, J.E. Conventional and Recent Advances of Vegetable Oils as Metalworking Fluids (MWFs): A Review. Lubricants 2023, 11, 160. [CrossRef]

- Landi, F.A.F., Fabiani, C., Pisello, A.L. Palm oil for seasonal thermal energy storage applications in buildings: The potential of multiple melting ranges in blends of bio-based fatty acids. J. Energy Storage 2020, 29, 101431. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., Chen, M., Zhao, Y., Zhang, Y., Wu, Y., Zhang, J., Yang, X. Waste cooking oil applicable phase change capsules to improve thermoregulation of foamed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 432, 136538. [CrossRef]

- Irsyad, M., Amrizal, Harmen, Amrul, Susila Es, M.D., Diva Putra, A.R. Experimental study of the thermal properties of waste cooking oil applied as thermal energy storage. Results in Engineering 2023, 18, 101080. [CrossRef]

- Okogeri, O., Stathopoulos, V.N. What about greener phase change materials? A review on biobased phase change materials for thermal energy storage applications. Int. J. Thermofluids 2021, 10, 100081. [CrossRef]

- Gatto, V., Conca, S., Bardella, N., Beghetto, V. Efficient Triazine Derivatives for Collagenous Materials Stabilization. Materials 2021, 14, 3069. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Chen, M., Wu, S., Xu, H., Wan, P., Zhang, J. Preparation and characterization of phase change capsules containing waste cooking oil for asphalt binder thermoregulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 395, 132311. [CrossRef]

| Component | Sunflower oil(a) | Sunflower oil WCO(b) | Rapeseed oil(a) | Rapeseed oil WCO(a) | Palm Oil(a) | Palm oil WCO(a) | Sun foil(a) | Sun foil WCO(a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated Fatty Acids | 71.5 | 32.0 | 80.0-93.0 | 74.4 | 73-15 | |||

| Monounsaturated Fatty Acids | - | 62.0 | 20.0-7.0 | 27-6 | ||||

| Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids | 28.5 | 6.0 | 25.6 | 0-79 | ||||

| Acidic value (mg KOH/g oil) | 0.30 | 2.29 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.66-1.13 | 0.72-1.44 | ||

| pH | 7.38 | 5.34 | 6.34 | 5.73-6.19 | 8.63 | 6.14-6.61 | ||

| Density at 20°C (kg/m3) | 919.21 | 920.40 | 918.00 | 929.00 | 919.48 | 923.2-913.4 | 919.6 | 919.8-923.2 |

| Kinetic Viscosity at 40°C (mm2/s) | 28.744 | 31.381 | 63.286 | 68.568 | 27.962 | 44.254-38.407 | 28.224 | 43.521-35.236 |

| Molecular weight (g/mol) | 670.82 | 51.94 | 869.16 | 871.01 | 535.08 | 135.66-586.05 | 119.71 | 55.18-395.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).