Introduction

Common bean production is vital in Western Kenya due to its economic, nutritional, environmental, and cultural significance (Ojiem, 2018). It provides a crucial source of income for smallholder farmers, supports regional trade, and contributes to food security by offering affordable, protein-rich food (Lisciani et al., 2024). However, bean production in this region faces several challenges, including pests and diseases, climate change, poor soil fertility, limited access to quality seeds, inadequate market access, post-harvest losses, lack of agricultural knowledge, and high input costs (Farrow & Muthoni Andriatsitohaina, 2020; Abobatta et al., 2021). Viral diseases, particularly the Bean Common Mosaic Virus (BCMV), Bean Common Necrotic Virus (BCMNV) (H. S. Singh & Lamani, 2024), and Bean Yellow Mosaic Virus (BYMV) among others, are known to cause significant yield and quality losses. Various approaches have been employed to mitigate these diseases, such as integrated pest management (IPM), using resistant bean varieties, crop rotation, and proper spacing to reduce disease spread. However, resource-poor farmers often struggle to afford and adopt these interventions.

Metabolic profiling has emerged as an essential tool for understanding the biochemical responses of plants to various stressors (Satrio et al., 2024), including viral infections (Khan et al., 2022). In regions like Western Kenya, where smallholder farmers rely heavily on common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) for nutrition, protein, and income, these viral diseases pose a significant threat to food security, especially in settings where access to diagnostic tools, pest management strategies, and agricultural extension services is limited. There are two approaches in metabolomics; Targeted metabolomics is crucial in understanding plant defense mechanisms and nutrition by comprehensively analyzing specific metabolites (Sharma et al., 2021). In addition, targeted metabolomics allows for the identification and quantification of key compounds such as phytohormones, secondary metabolites, and defense-related chemicals, which are produced by plants in response to biotic and abiotic stresses (Castro-Moretti et al., 2020; Vo et al., 2021). This approach has been used to identify metabolic pathways activated during stress responses, enabling the identification of potential biomarkers for disease resistance (Maia et al., 2020; Satrio et al., 2024) and improving our understanding of how plants defend themselves against pathogens, pests, or environmental stressors. In addition, targeted metabolomics offers insights into the composition of essential nutrients, including vitamins, amino acids, and minerals, present in plants (Kumar et al., 2017; D. P. Singh et al., 2022). By analyzing these metabolites, we can assess the nutritional value of crops, identify variations in nutrient levels across different plant varieties or growth conditions, and optimize agricultural practices to enhance crop yields and nutritional content. Furthermore, developing crops with improved nutrient profiles or increased resistance to stress can contribute to food security and human health.

Untargeted metabolome profiling is critical in understanding the biochemical complexities associated with viral infections in common beans, particularly in resource-limited settings like Western Kenya. This approach involves the comprehensive analysis of a wide array of metabolites without prior specification of which molecules to target, thereby providing a holistic view of the metabolic alterations occurring post-infection. By utilizing advanced analytical techniques such as Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, we can identify and quantify various metabolic pathways that may be disrupted by viral pathogens (Manchester & Anand, 2017; Purdy, 2019). In examining the untargeted metabolome profiles of beans affected by viral diseases, insights can be gained into the plant’s stress response mechanisms and overall health. Such detailed profiling not only enhances our understanding of plant-pathogen interactions but also aids in developing targeted management strategies to improve crop resilience in affected regions.

Viral infections have been shown to disrupt plant growth and reproduction, resulting in significant modifications to plant metabolism (Zhao & Li, 2021). These changes are thought to reflect the plant’s defense mechanisms, nutrient allocation, and overall physiological state (Di Carli et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2020). However, many studies have pointed out that the full extent of these metabolic shifts and their implications for plant health and resistance mechanisms remain poorly understood, especially in the context of resource-poor farming systems. Furthermore, the lack of reliable and accessible diagnostic methods makes it difficult for farmers to detect viral infections early, which hinders timely intervention and the adoption of effective agricultural practices.

This study aimed to characterize the targeted and untargeted metabolome profiles of common beans infected by viral diseases to address challenges in viral disease detection and crop resilience. Targeted metabolomics focuses on specific metabolites, enabling the identification of metabolic markers related to disease presence and progression. In contrast, untargeted metabolomics provides a broader view of the entire metabolome, revealing biochemical pathways and potential novel biomarkers. By combining these approaches, we seek to provide a comprehensive understanding of how viral infections impact plant metabolism. In addition, this further aimed to identify key metabolic alterations in response to viral infections, correlating these changes with disease severity and resistance mechanisms. Identifying specific biomarkers could improve early detection and disease monitoring, while also contributing to breeding programs for developing viral-resistant bean varieties, enhancing crop resilience in resource-limited environments.

Methodology

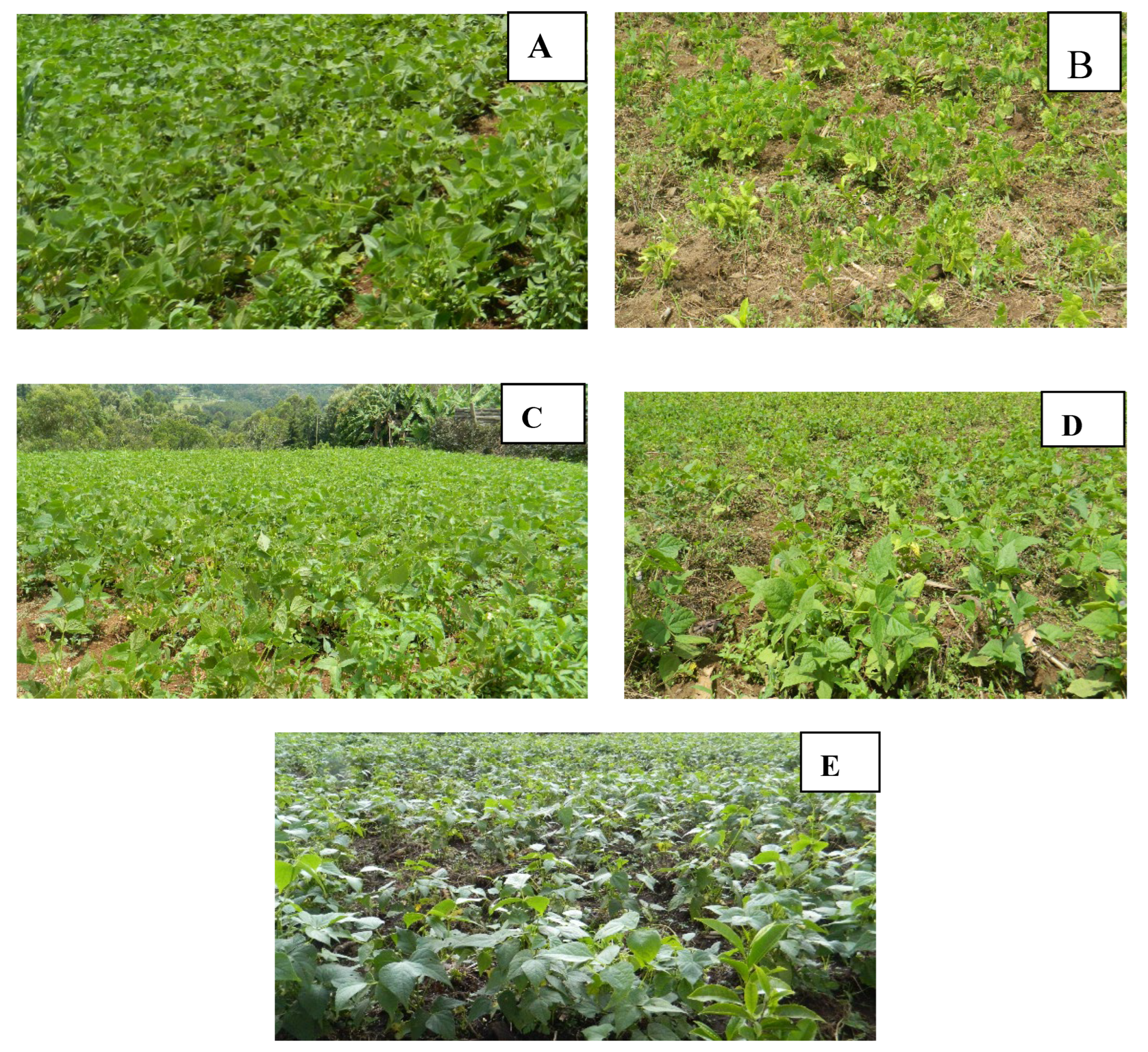

Four study sites were selected within the Western Region of Kenya: Musasa (Vihiga), Sichilayi (Kakamega), Butula (Busia), and Tuti (Bungoma). At these sites, the Rosecoco bean cultivar was planted and subjected to mechanical inoculation (Bhat et al., 2020) with BCMV, BCMNV, and CMV viruses at the three-leaf stage. Control plots were established using virus-free Rosecoco seeds planted under similar conditions to serve as a baseline comparison (

Figure 1). The inoculum for the mechanical transmission experiments was prepared from fresh or lyophilized leaves of Common bean plants infected with BCMV and BCMNV. The infected plant material was homogenized in potassium phosphate buffer (0.01 M, pH 7.0) at 1:5 (w/v). The homogenate was then filtered through Muslin cloth to remove large debris, yielding a clarified inoculum. This inoculum was used immediately for vascular puncture inoculation. inoculation, the leaves of the target plants were dusted with 400-mesh carborundum to facilitate virus entry by creating micro-abrasions on the leaf surface. Control plants were similarly dusted with carborundum but inoculated with phosphate buffer alone to ensure the validity of the experimental setup. For the control experiment, all plants were maintained in a greenhouse under controlled environmental conditions, with temperatures ranging from 25 to 30°C, for 30 days. The plants were monitored daily for symptom development, and serological validation of virus acquisition was performed using ELISA tests with the relevant antisera

Samples were collected at the near-flowering stage, consisting of 50 leaf samples (at least 10 from each of the 4 study site) and 10 samples from virus-free controls. The samples were quickly snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen, stored at −80°C, freeze-dried, and sent to the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany for metabolome analysis.

Targeted and Untargeted Metabolome

The Leaf samples collected were ground using a HG-600 Geno/Grinder® 2010 (Cole-Parmer, New Jersey, USA) for 60 secs at 1150 strokes/min and extracted in 1mL of extraction buffer (200 mL Milli-Q water and 800mL HPLC grade MeOH) with standards (12.5 ng phytohormone IS) for 24 hours, then centrifuged at 19,000g for 20 minutes at 4oC. About 600-700 µL of the supernatant was transferred into 1.8mL autosampler vials and stored at -20°C until analyzed. The filtrate obtained was analyzed using liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry (LCMS-9030 qTOF, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) to quantify metabolites at various intervals. Chromatographic separation was performed on a Shim-pack Velox C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 2.7 µm particle size) maintained at 55°C (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). A 3 µL injection volume was used for all samples, which were analyzed with a binary mobile phase: solvent A consisted of 0.1% formic acid in Milli-Q HPLC grade water (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and solvent B was UHPLC grade methanol with 0.1% formic acid (Romil Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom). The analysis was conducted on a qTOF high-definition mass spectrometer operating in negative electrospray ionization mode. The instrument parameters included a nebulizer voltage of 4.0 kV, interface temperature of 300°C, dry gas flow of 3 L/min, detector voltage of 1.8 kV, heat block temperature of 400°C, DL temperature of 280°C, and flight tube temperature of 42°C. Ion fragmentation was induced using argon gas with collision energies of 30 eV and a 5 eV spread (Ramabulana et al., 2021).

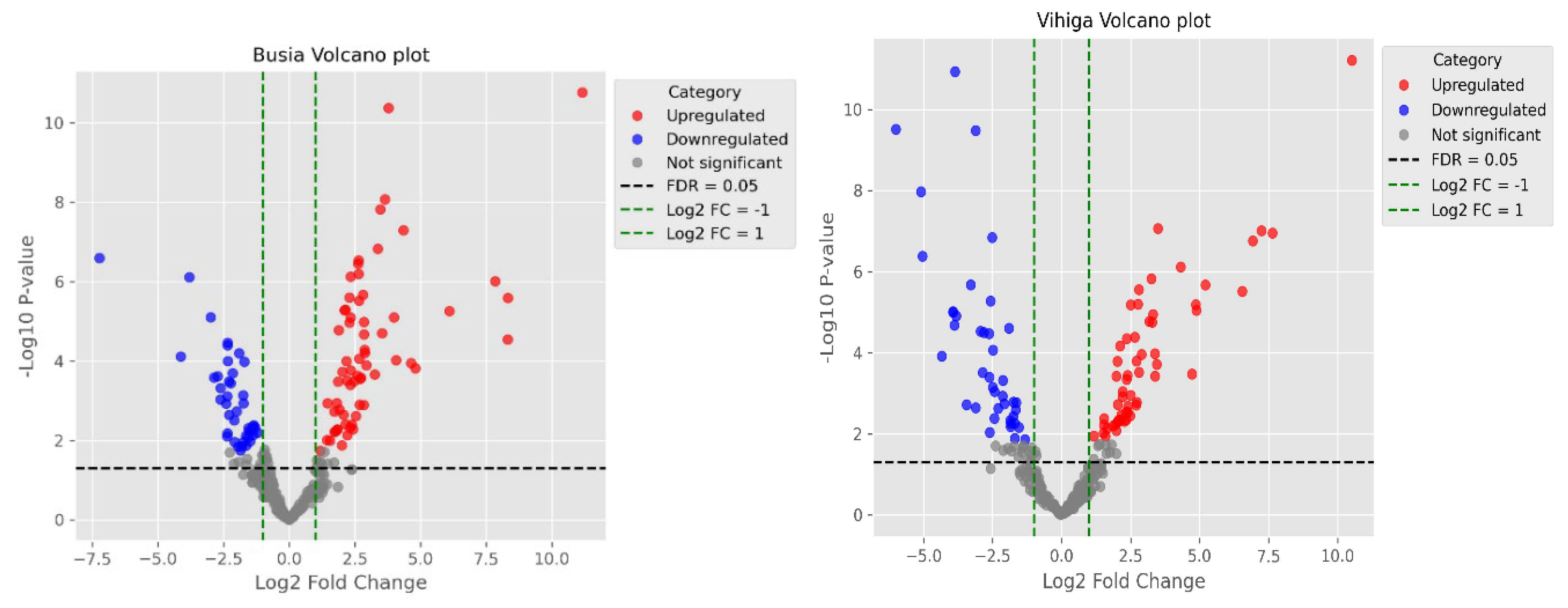

Data pre-processing was performed using XCMS, with HPLC/UHD qTOF parameters employing the centWave feature detection method. A maximum threshold of 15 ppm, a signal-to-noise ratio of 6, and prefilters for intensity and noise set to 100 and 3, respectively, were applied. Retention time correction was done using the Obiwarp method with profStep, while alignment required a minimum sample fraction of 0.5 and an m/z width of 0.015. The data was initially analyzed by visualizing the mass spectra and generating a feature table using MZmine v4.4.0, with parameters adjusted to optimize data processing. Feature quantification was normalized based on the original masses of the samples using custom Python scripts developed with pandas v2.2.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted using the PCA module from sklearn. decomposition. Differential expression of metabolites was assessed with the edgeR v4.0 package, and the results were visualized through volcano plots and heatmaps, generated using Python scripts built with matplotlib.pyplot.

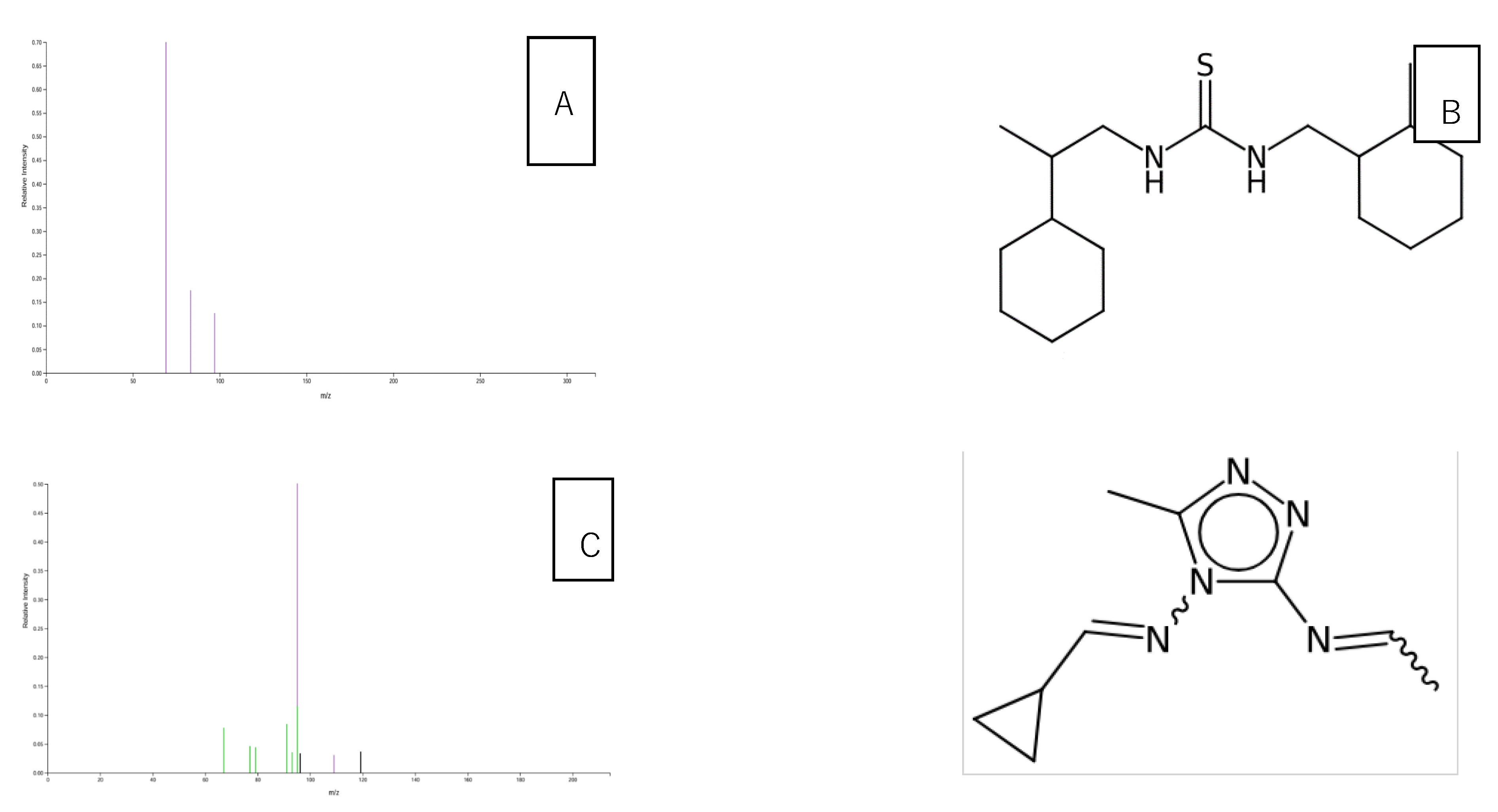

The mascot generic format (mfg) files and metadata for the respective treatments were processed on the GNPS2 online platform for networking and Sirius v6 for spectral annotation. Spectral searches utilized libraries such as GNPS, Biocyc, CHEBI, COCONUT, DSSTox, Blood Exposome, FooDB, HMBD, HSDB, KEGG, KNApSAck, LOTUS, LipidMaps, Maconda, MeSH, MiMeDB, NORMAN, Plantcyc, PubChem, PubMed, SuperNatural, TeroMOL and YMDB embedded in Sirius (Böcker et al., 2009; Ludwig et al., 2020). Metabolites were matched to GNPS2-linked databases and were putatively annotated or verified through searches in compound databases using their peak mass and isomeric SMILES. Further confirmation of annotations was carried out through literature searches of relevant studies. Metabolite concentrations were then analyzed to identify enriched metabolomic pathways. Pathway overrepresentation was assessed using a hypergeometric test.

Phytohormone Analysis

Phytohormone analysis was carried out by LC-MS/MS, following the method of (Heyer et al., 2018) Heyer et al. (2018), using an Agilent 1260 series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies), with modifications. A tandem mass spectrometer, QTRAP 6500 (SCIEX, Darmstadt, Germany), was used, and the chromatographic gradient was adjusted. Chromatographic separation was performed on a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 column (50 × 4.6 mm, 1.8 µm, Agilent Technologies). The mobile phases were water with 0.05% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B). The elution profile was as follows: 0–0.5 min, 5% B; 0.5–9.5 min, 5–58% B; 9.5–9.51 min, 58–100% B; 9.52–11.0 min, 100% B; and 11.01–14.0 min, 5% B. The flow rate was maintained at 1.1 ml/min, and the column temperature was set to 25 °C. The mass spectrometer operated in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode in negative ionization mode.

Discussion

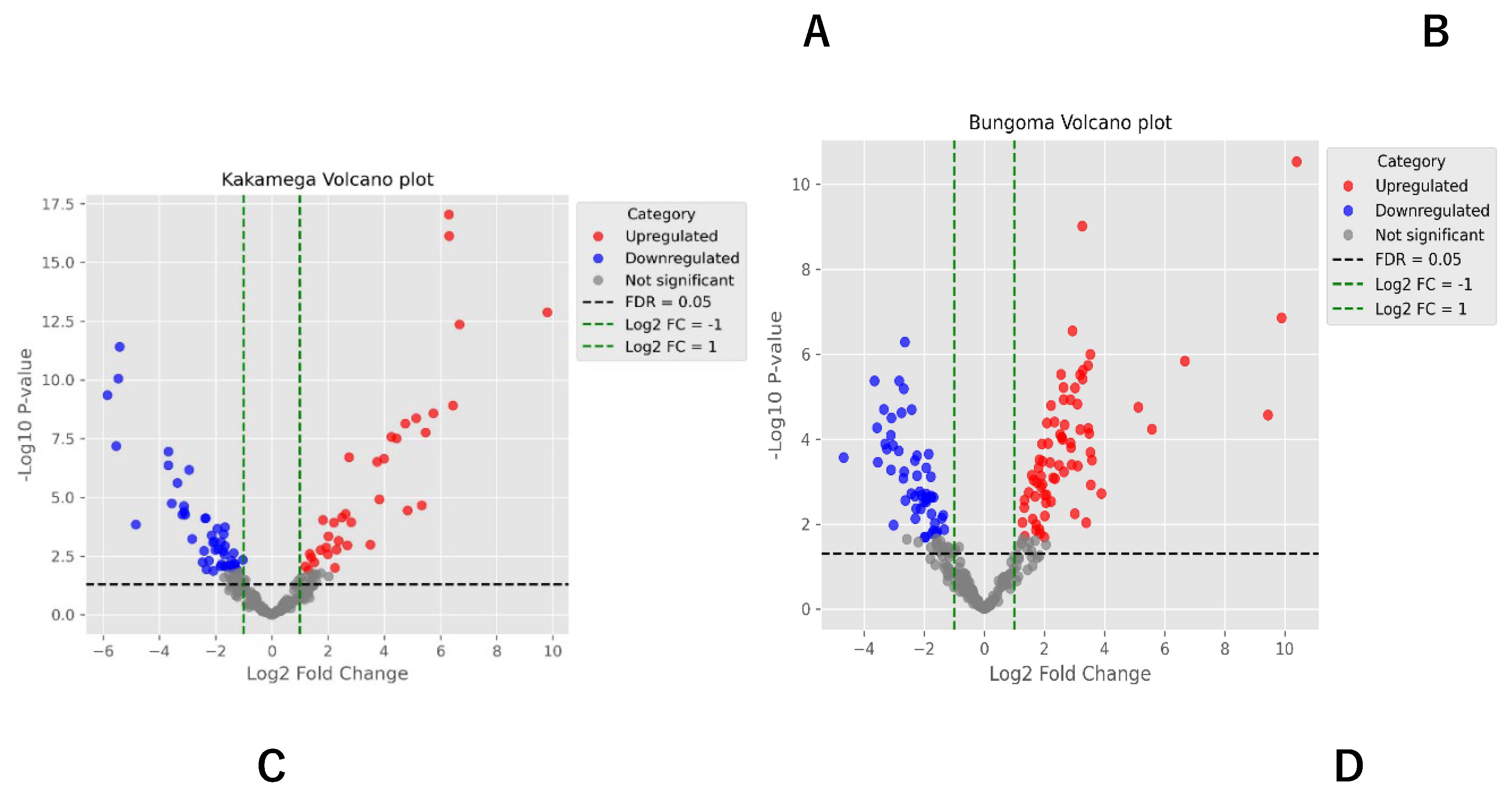

This study identified a total of 354 metabolites across seven metabolic pathways, revealing a complex interplay of biochemical processes. The alkaloid pathway exhibited a balanced distribution of upregulated and downregulated metabolites, suggesting dynamic regulation in response to the experimental conditions. Upregulation in alkaloid synthesis could reflect an adaptive response to the biotic stress the common bean was subjected to, while the downregulation of 11 metabolites may indicate a reduction in some alkaloid production when not needed under these conditions. Notwithstanding these findings, the alkaloid pathway has been associated with enhancing the nutritional value of a healthy diet and improving the adaptability of Broad bean seeds (Vicia faba L.) (Shi et al., 2022). Similarly, another study identified 29 differential metabolites and 19 genes (14 structural and 5 regulatory) in Chenopodium quinoa (wild.), revealing consistent variations in flavonoid, phenolic acid, and alkaloid metabolites across different quinoa types (Liu et al., 2023) were linked to mechanisms shaping taste and quality.

The amino acid and peptide pathway exhibited a large number of downregulated metabolites (8 downregulated, 4 upregulated), potentially reflecting a reduction in amino acid synthesis under the studied conditions. Amino acids serve as essential building blocks for proteins (Battezzati & Riso, 2002) and gaseous signaling molecules, including ethylene, nitric oxide, and hydrogen sulfide (Brosnan & Rooyackers, 2012). This observed downregulation may indicate a metabolic shift towards alternative pathways, such as energy storage or the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites.

Carbohydrate metabolism plays a crucial role in stress tolerance and plant adaptive mechanisms, including responses to temperature stress (Nguyen, 2018) and drought tolerance (Dwivedi et al., 2023). In this study, the carbohydrate pathway exhibited no upregulated metabolites and only minimal downregulation, indicating its stability and limited involvement in the observed metabolic reprogramming. The reason for this could be that probably alternative energy sources, such as fatty acids, may have played a more prominent role under the studied conditions.

Flavonoids are natural products known for their significant role in protecting against various human diseases. Several bioactive flavonoids, including chalcones, flavones, flavanones, flavanols, isoflavonoids, and proanthocyanidins, are found in diverse parts of plants such as leaves, roots, bark, stems, flowers, weeds, and fruits. These compounds are synthesized in higher plants through the shikimate, phenylpropanoid, and polyketide pathways (Rehan, 2021).The polyketide pathway demonstrated a complex response, with 14 metabolites being downregulated and 8 upregulated. This indicates that while certain metabolites within this pathway may be upregulated for defense or specialized functions, the overall activity of the pathway may be diminished, reflecting shifts in metabolic priorities toward other processes. Similarly, the shikimate and phenylpropanoid pathways exhibited a reduction in metabolite production, with 16 metabolites downregulated and only one upregulated. This may indicate a potential shift away from the synthesis of aromatic and secondary metabolites, possibly to prioritize more immediate metabolic needs.

In contrast, the terpenoid pathway displayed a mixed response, with 11 metabolites upregulated and 28 downregulated. This indicates selective synthesis of certain terpenoids, likely in response to environmental stimuli or as part of the plant’s defense mechanisms, while other components of the pathway were suppressed. These findings highlight the dynamic regulation of metabolic pathways in response to shifting environmental and physiological demands.

Very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs), defined as fatty acids with more than 18 carbon atoms, are critical for physiological and structural functions in plants. VLCFAs are key components of membrane lipids, maintaining membrane homeostasis and selectively accumulating in the sphingolipids of the plasma membrane’s outer leaflet, where they play a vital role in intercellular communication (Batsale et al., 2021). Additionally, VLCFAs are found in phospholipids such as phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine, influencing membrane domain organization and interleaflet coupling. In epidermal cells, they serve as precursors for the cuticular waxes that form the plant cuticle, which is essential for regulating interactions with the external environment (Batsale et al., 2021). Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), produced by colonic bacteria and derived from dietary sources, contribute to human health through their metabolic and signaling properties. Their physiological functions are determined by the length of their aliphatic tails and are mediated by the activation of specific membrane receptors (González-Bosch et al., 2021).

In the common bean plant, 131 metabolites were found to be downregulated across various pathways, with the fatty acid pathway exhibiting the largest reduction (53 metabolites). This point to significant shifts in lipid metabolism, potentially linked to energy demands, stress responses, or regulatory feedback mechanisms. Terpenoid metabolism also showed substantial downregulation (28 metabolites), suggesting adjustments in secondary metabolite production. Conversely, carbohydrate metabolism displayed minimal downregulation, indicating it was not a primary target of metabolic reprogramming.

The observed upregulation of certain fatty acid and terpenoid metabolites, alongside the downregulation of others, suggests a complex metabolic shift likely driven by stress or resource allocation. Fatty acids and secondary metabolites such as terpenoids appear to play pivotal roles in plant adaptation to environmental stressors, while carbohydrate metabolism remains relatively stable, possibly reflecting reliance on fatty acids for energy. These outcomes suggest coordinated metabolic reprogramming, with a focus on lipid and secondary metabolite synthesis, while carbohydrate metabolism remains conserved. Future research should explore the regulatory mechanisms underlying fatty acid and terpenoid pathways, as well as their interactions and shared metabolic controls.

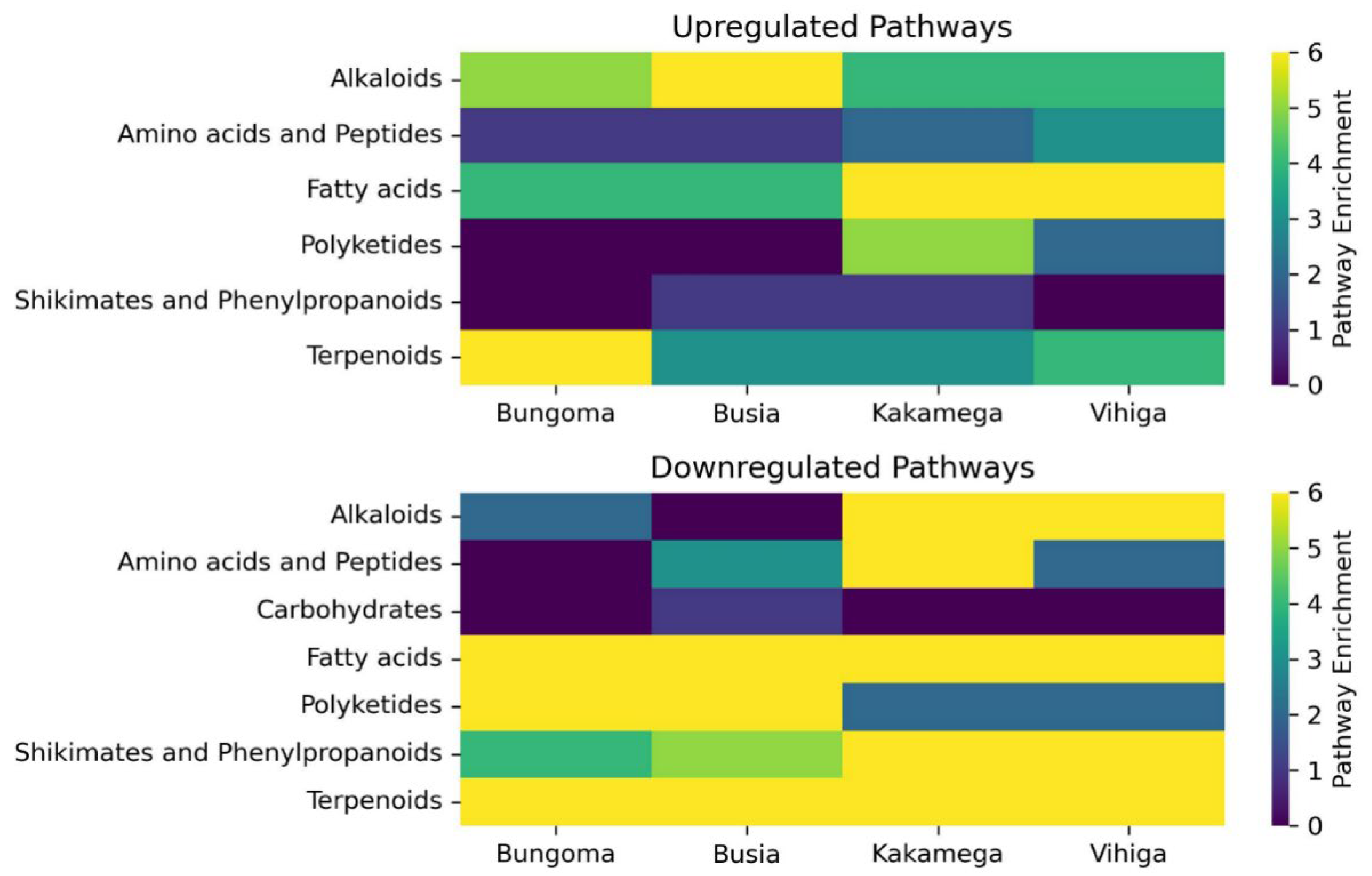

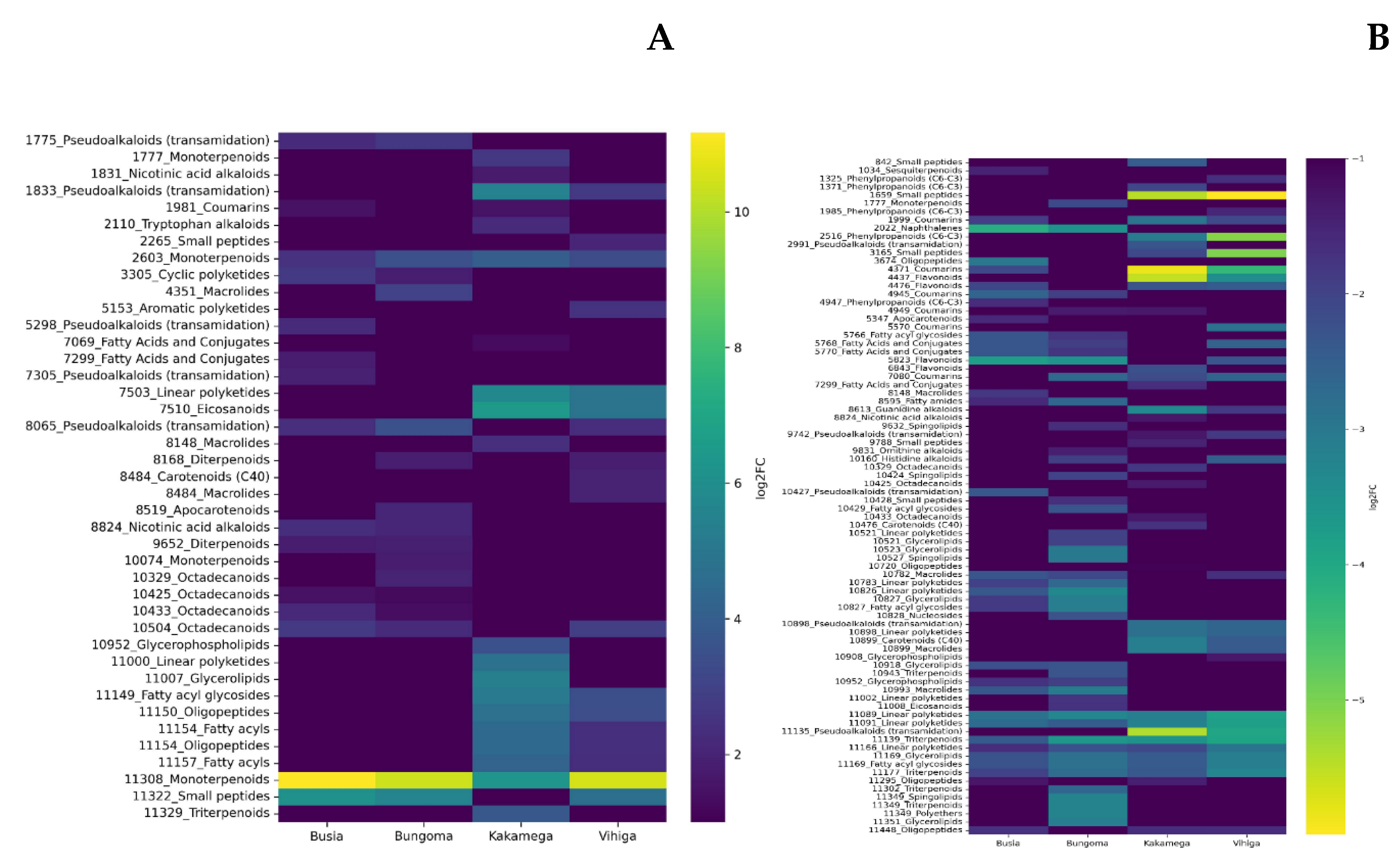

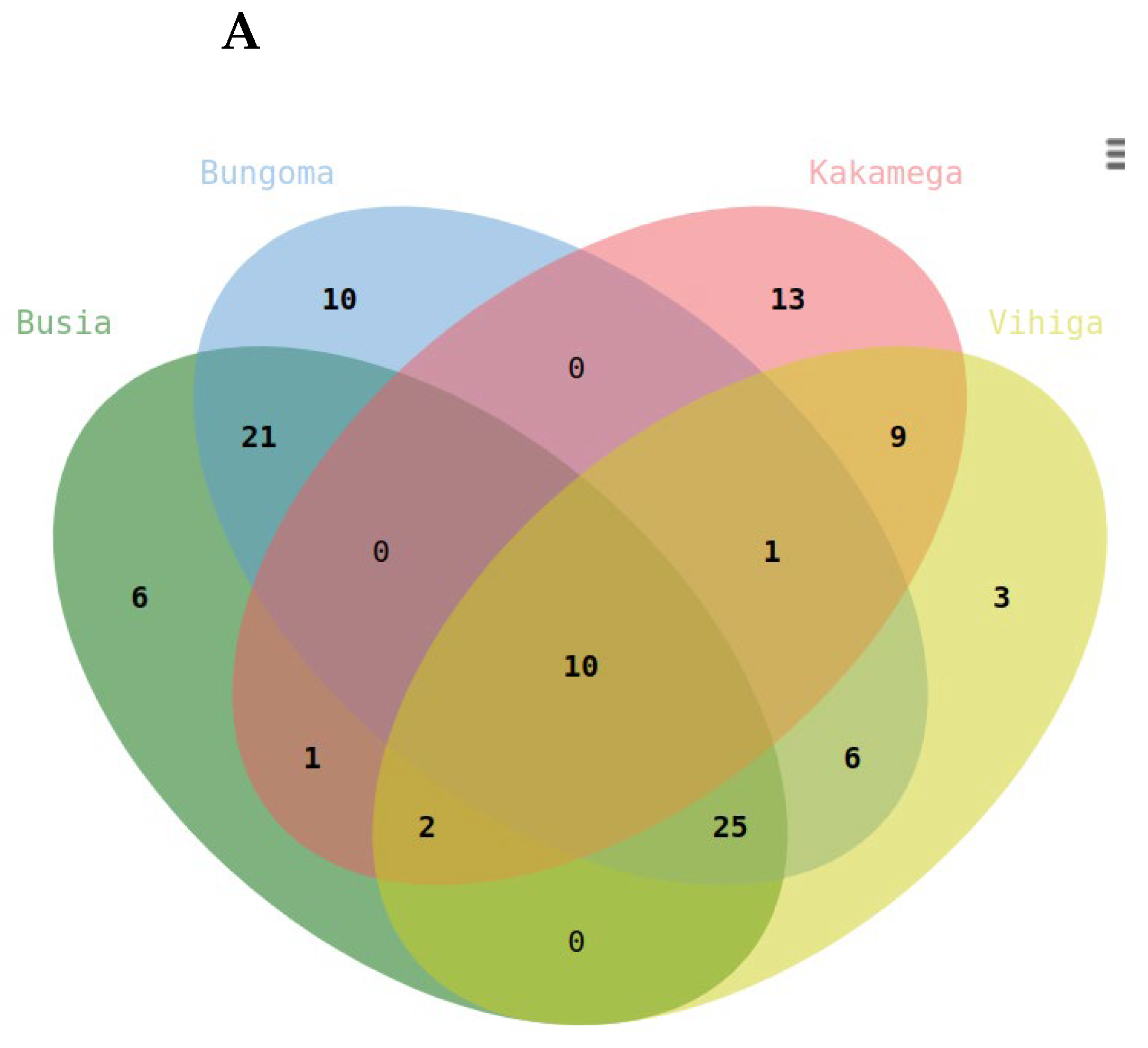

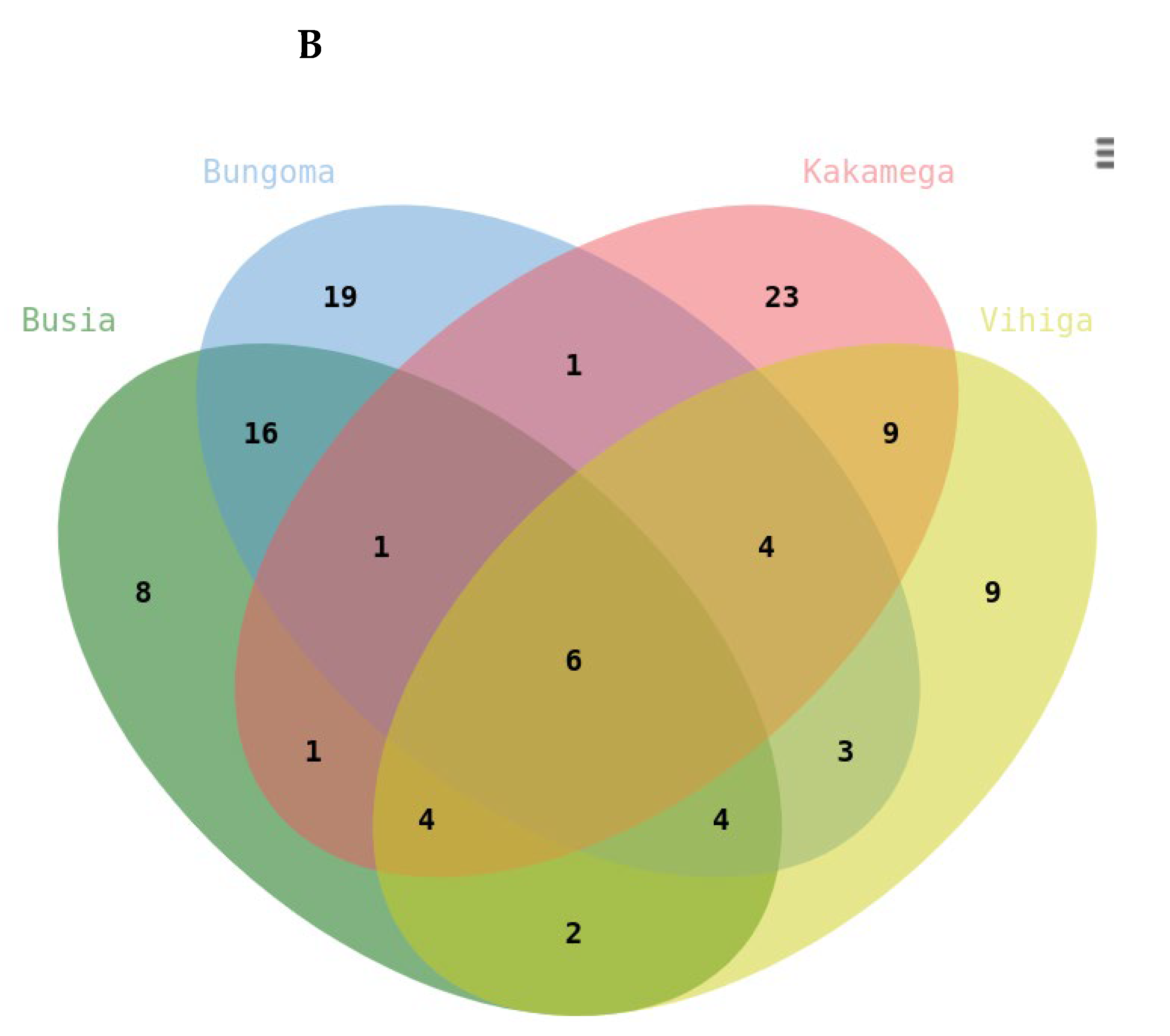

The study also revealed distinct regional patterns in metabolite expression, highlighting the influence of environmental and geographical factors. Kakamega exhibited the highest number of unique downregulated metabolites (23), followed by Bungoma (19), Vihiga (9), and Busia (8). This regional variation suggests that local conditions, including soil composition, climate, and biotic factors, may shape the metabolic profiles of plants. Despite these regional differences, six metabolites were commonly downregulated across all four regions. These included terpene glycosides, fatty acyls, triterpenoids, glycosylglycerols, and alkyl glycosides. The downregulation of these metabolites suggests their potential role in the plant’s metabolic response to shared environmental stressors or conditions, such as nutrient limitations or biotic stress. These metabolites could also serve as biomarkers for disease monitoring or regional agricultural applications.

In Busia, Bungoma, and Vihiga counties, monoterpenes (Mapping ID 11308) were the most upregulated metabolites, reflecting an increased defense response to biotic stressors. Monoterpenes are known to play roles in plant defense (Li et al., 2023), including insect repellence (Abdelgaleil et al., 2024) and UV protection (Qasim et al., 2024). In Kakamega, eicosanoids (Mapping ID 7510), pseudoalkaloids (Mapping ID 1833), and monoterpenoids (Mapping ID 11308) were upregulated, signifying a specific response to stress or inflammatory processes eclusive to this region.

The downregulation of metabolites across counties suggests a prioritization of primary metabolism over secondary metabolite production under experimental conditions. In Kakamega, the downregulation of pseudoalkaloids, guanidine alkaloids, flavonoids, coumarins, and small peptides may indicate a reduction in metabolic resources allocated to defense and antioxidant production. Similarly, Bungoma and Busia counties showed downregulation of metabolites related to defense, such as triterpenoids, flavonoids, and naphthalenes.

Vihiga County exhibited the broadest range of downregulated metabolites, reflecting a widespread alteration in metabolic pathways. This includes the downregulation of triterpenoids, pseudoalkaloids, linear polyketides, coumarins, small peptides, and phenylpropanoids, suggesting complex responses to environmental or physiological stress.

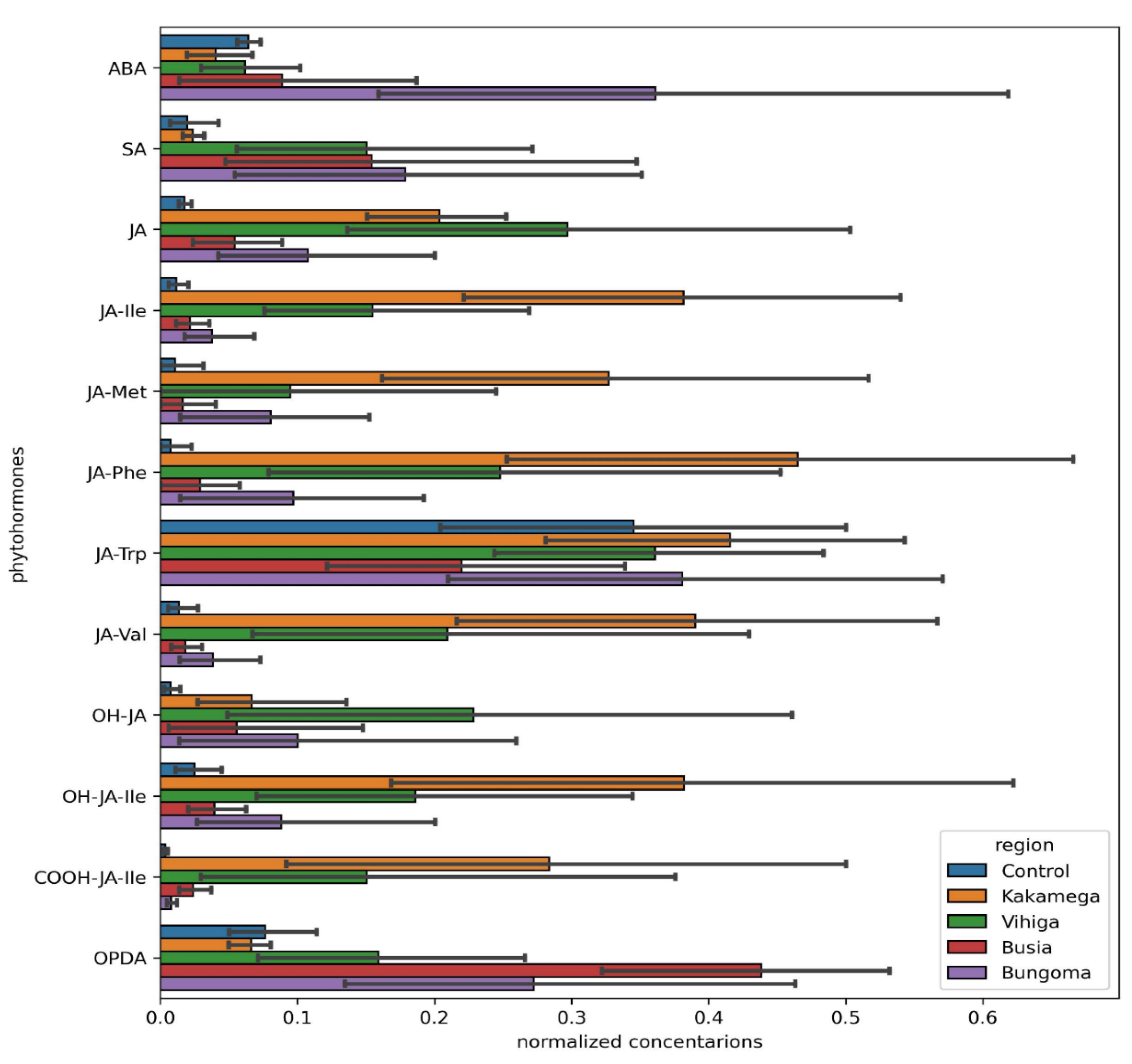

Phytohormones/ Targeted Metabolomics

The findings of this study reveal significant regional variability in the regulation of key phytohormones, particularly abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA), and jasmonic acid (JA) derivatives, which are crucial for plant defense and stress adaptation (Pigolev et al., 2023). These variations highlight the influence of local environmental factors such as soil composition, water availability, and climate on plant hormonal responses.

Abscisic acid (ABA), a hormone primarily linked to stress responses, particularly under drought or water-deficit conditions (Muhammad Aslam et al., 2022), was significantly upregulated in Bungoma and Kakamega (p-values of 0.0312* and 0.0257*, respectively). This indicates that the common bean plants in these regions likely responded to biotic (viral) stressors, which activated ABA signaling. In contrast, ABA showed no significant change in Busia and Vihiga (p-values of 0.0792 and 0.0890, respectively), which may indicate more stable environmental conditions or a reduced need for ABA-mediated stress responses in these areas.

Salicylic acid (SA), known for its role in plant immune responses and defense mechanisms (An & Mou, 2011; Irkitbay et al., 2022), was commonly upregulated across all four counties, with p-values ranging from 0.0022* to 0.0113*. This broad upregulation suggests that plants in these regions are facing environmental challenges—both biotic (e.g., pathogen attack) and abiotic (e.g., temperature fluctuations or water scarcity)—that activate the plant’s immune system. The consistent increase of SA plays an essential role in plant responses to stress across diverse environments (Zhao & Li, 2021).

Jasmonic acid (JA), a hormone involved in defense responses and stress adaptation (Wang et al., 2021), exhibited a more varied pattern across the counties. It was significantly upregulated in Kakamega and Vihiga (p = 0* and p = 0.0003*, respectively), indicating its active role in stress or defense pathways in these regions. In Bungoma, JA was also upregulated (p = 0.001), further suggesting an increase in defense mechanisms. However, in Busia, no significant changes in JA were observed (p = 0.1041), which could imply either that JA is not as pivotal in the region’s regulatory processes or that its regulation remains stable under local conditions.

The conjugated form of JA, jasmonic acid-isoleucine (JA-Ile), which is integral to defense signaling (Marquis et al., 2020), was significantly upregulated in Kakamega (p = 0.0022*) and Vihiga (p = 0.0003*), reinforcing the hormone’s role in stress or defense responses in these regions. Although JA-Ile also showed upregulation in Bungoma (p = 0.0257*), no significant change was observed in Busia (p = 0.1212), suggesting a regional disparity in its importance for plant metabolism and stress adaptation (Ma et al., 2023).

Other JA derivatives, such as JA-Met (a methylated form of jasmonic acid) and JA-Phe (a conjugate with phenylalanine) (Per et al., 2018), exhibited significant upregulation in some regions but not in others. JA-Met was notably upregulated in Bungoma (p = 0.0019*), while no significant changes were found in Kakamega, Busia, and Vihiga. In contrast, JA-Phe showed significant upregulation in Kakamega (p = 0.0005*) and Vihiga (p = 0.026*), suggesting its involvement in secondary metabolism and stress responses. These differences further highlight the region-specific role of JA derivatives in plant defense (Zhao and Li, 2021).

The hydroxyjasmonic acid (OH-JA) and its derivative OH-JA-Ile were also significantly upregulated in Bungoma and Vihiga (p-values ranging from 0.0008* to 0.02*), indicating that oxidative stress and defense mechanisms are prominent in these regions. However, Kakamega and Busia did not exhibit significant changes, suggesting that OH-JA and OH-JA-Ile may play a less critical role in these areas’ stress responses (Batsale et al., 2021).

Further analysis revealed significant changes in carboxylated JA forms, such as 12-JA (COOH-JA), and oxylipins like OPDA (Zhao & Li, 2021), which were notably upregulated in Kakamega and Vihiga (p-values ranging from 0.0032* to 0.0007* for COOH-JA, and 0.0173* to 0.0003* for OPDA). These metabolites likely play a role in stress adaptation and metabolic regulation in these regions. In contrast, Bungoma and Busia did not show significant alterations, reinforcing the idea that these regions experience less metabolic reprogramming in response to the biotic stress

Overall, these findings underscore the significant regional variability in the regulation of plant defense hormones, particularly JA and its derivatives, SA, and ABA. The upregulation of these hormones in most counties suggests their pivotal role in stress and defense responses, with local environmental factors such as climate, soil, and water availability likely influencing the extent and nature of hormonal regulation. Kakamega and Vihiga exhibited more consistent upregulation of defense-related hormones, indicating higher stress levels or a greater need for robust defense mechanisms. Conversely, Busia and Bungoma showed more selective responses, possibly due to more stable environmental conditions or different regulatory priorities in these areas. This regional variability highlights the complexity of plant stress responses and the influence of environmental context on hormonal regulation.

Implications and Future Directions

The observed upregulation and downregulation of metabolites across counties indicate the metabolic flexibility of plants in response to different environmental challenges. For instance, the upregulation of monoterpenes may reflect enhanced defense mechanisms triggered by stressors like herbivory or pathogen presence. The downregulation of secondary metabolites like flavonoids and alkaloids may signal a shift away from energy-costly processes in favour of more efficient metabolic pathways.

Geographical differences in metabolite profiles highlight the importance of local environmental factors in shaping plant metabolism. Understanding these variations is crucial for optimizing agricultural practices, enhancing crop resilience, and exploring the potential of specific metabolites for industrial or pharmaceutical applications.

Future Studies Should Focus on

Investigating the regulation of fatty acid and terpenoid pathways to understand their adaptation to specific biotic stress, while examining the interplay between their biosynthesis to uncover potential shared regulatory mechanisms or precursor molecules involved in their upregulation and downregulation.

Further research into the specific environmental and ecological factors influencing these hormonal shifts could help improve agricultural practices, particularly in developing region-specific strategies for enhancing plant resilience to stress.