1. Introduction

The rapid evolution of educational technology has opened new avenues for delivering complex concepts to younger audiences. One such avenue is the use of serious games, which merge entertainment with pedagogical goals. This paper focuses on a serious game designed to address two critical and intertwined topics: nutritional health and environmental sustainability. These issues are particularly relevant for Generation Alpha, who will grow up in a world facing mounting challenges related to food security and climate change. The app discussed in this study leverages Augmented Reality (AR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) to create an engaging, interactive learning experience. Through AR, users interact with a virtual supermarket, selecting food items as they would in a real environment. Two AI-driven Non-Player Characters (NPCs), powered by ChatGPT, evaluate the choices made by users. Each NPC provides feedback tailored to one of two core educational themes: nutritional education and environmental sustainability.

Augmented reality (AR) and serious games are proving to be transformative in the field of nutrition education. Research highlights their ability to enhance engagement, knowledge retention, and influence dietary behavior positively. For instance, Paramita et al. [

1] emphasize that AR can reduce boredom and heighten interest in learning about nutrition. Interactive games and simulations are also effective tools. McMahon and Henderson [

2] explore mobile-based pervasive games that utilize QR codes, making dietary learning engaging for children. Similarly, Barwood et al. [

3] report on computer games’ efficacy in promoting healthier food choices among young users. Educational innovations extend to professional training as well. Camacho and Guevara [

4] note the benefits of AR in dietetics education, providing realistic and interactive training environments that surpass traditional methods.

Participatory game design is another promising approach. Leong et al. [

5] detail the development of video games aimed at improving children’s nutrition knowledge, highlighting the importance of balancing engagement with concerns like screen time. Moreover, AR and virtual reality (VR) applications are gaining traction. For example, Pilut et al. [

6] show how a VR grocery store tour can boost self-efficacy in purchasing healthy foods, suggesting broader implications for serious games in enhancing nutrition literacy. Overall, these studies collectively underscore the significant potential of AR and serious games in making nutrition education more effective and enjoyable.

In relation to the second educational objective, food sustainability, the intersection of food sustainability, serious games and augmented reality (AR) is an innovative area of research that offers promising strategies for promoting sustainable eating habits and education. AR has been shown to effectively engage users by providing interactive experiences that enhance dietary behaviors and support sustainable nutrition practices. Serious games leverage interactive and immersive gameplay to instill sustainable nutrition values. The game “You Better Eat to Survive!” exemplifies how virtual reality (VR) can incorporate real food consumption to enhance social interaction and sustainable eating behaviors [

7]. Beyond traditional gameplay, AR and VR technologies foster more profound behavioral changes by simulating real-world consequences. A study by Plechatá et al. [

8] demonstrated that VR interventions could reduce dietary footprints by enhancing awareness of the environmental impact of food choices. Meanwhile, Fritz et al. [

9] show that AR enhances food desirability by enabling users to mentally simulate consumption, promoting healthier and sustainable purchasing decisions.

ChatGPT is emerging as a promising tool in the realm of nutrition education, offering personalized learning experiences and supporting dietary education. For instance, Garcia [

10] explores ChatGPT’s potential as a virtual dietitian, highlighting its ability to improve nutrition knowledge through personalized meal planning and educational materials. Similarly, Ray [

11] notes the increasing use of AI technologies, including ChatGPT, in academic settings for nutrition and dietetics. The accuracy and effectiveness of ChatGPT in responding to nutrition-related queries have also been tested. Kirk et al. [

12] found that ChatGPT provided more scientifically correct and actionable answers compared to human dieticians. However, Mishra et al. [

13] caution about potential harm in complex medical nutrition scenarios, emphasizing the need for responsible use by healthcare professionals. Beyond individual learning, ChatGPT aids in healthcare education. Sallam [

14] highlights its role in personalized learning and critical thinking. Despite its potential, challenges like generating incorrect information remain, as noted by Lo [

15]. ChatGPT’s application extends to specific patient groups, such as those with chronic kidney disease, where Acharya et al. [

16] report its potential in enhancing nutrition education through accurate and timely responses. While ChatGPT shows significant promise, further research is essential to refine its use and address limitations in nutrition education [

17]. This dual approach of leveraging technology while maintaining professional oversight could redefine the educational landscape in dietetics and nutrition.

While generative AI applications in education are rapidly emerging, current research has primarily focused on their ability to deliver personalized learning experiences and facilitate interactive dialogue. Studies demonstrate the potential of AI to improve engagement and adapt content dynamically to learner needs. However, critical gaps remain unaddressed in the literature, particularly in the following areas.

Lack of Objective Evaluation Frameworks. Existing AI-driven educational tools often lack a robust framework for evaluating their effectiveness against specific, measurable learning objectives. While they may improve user engagement, their alignment with predefined educational goals is seldom systematically assessed.

Iterative Improvement Based on Learning Outcomes. Most AI applications in education do not incorporate iterative processes to refine their content delivery based on feedback or performance relative to educational objectives. This limits their capacity to adapt and improve in achieving targeted learning outcomes.

Integrating AI and AR in serious games. Although AR and AI have been used independently in education, their combined potential for immersive and adaptive learning experiences has been little explored. Furthermore, the integration of generative AI in AR-based serious games to achieve specific educational goals has not been explored in depth.

This study aims to fill these gaps by presenting an innovative framework for evaluating and optimising AI-driven educational feedback within a serious game.

This study focuses on ARFood, a serious game designed to educate Generation Alpha about nutritional health and environmental sustainability. Based on the previous gaps, the research questions of the paper are as follows

RQ1. How effectively can AR engage teenagers in generating realistic virtual shopping carts to analyse their purchasing behaviour?

RQ2. Can the responses of an AI-based generative non-player character (NPC), designed to communicate in an engaging and accessible language for Generation Alpha, be systematically evaluated for alignment with specific educational goals?

RQ3. Can the results of the evaluation be used to improve the appropriateness of NPC responses to specific educational objectives?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. ARFood’s Storytelling

To explore the potential of integrating Augmented Reality (AR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) in educational serious games, we developed ARFood—an app designed to teach Generation Alpha about nutritional health and environmental sustainability. ARFood is an educational augmented reality application designed to immerse middle school students in a journey of food education and sustainability awareness through interactive storytelling and gameplay.

The adventure begins when players enter the ARFood universe where they are asked to choose a nickname to establish their unique identity within the game. Players are then faced with the task of selecting the configuration of the household to which the food will be allocated. Options range from a single person to a family of five, including the progressive choice of a ’rainbow family’, which promotes inclusivity and reflects different modern family structures.

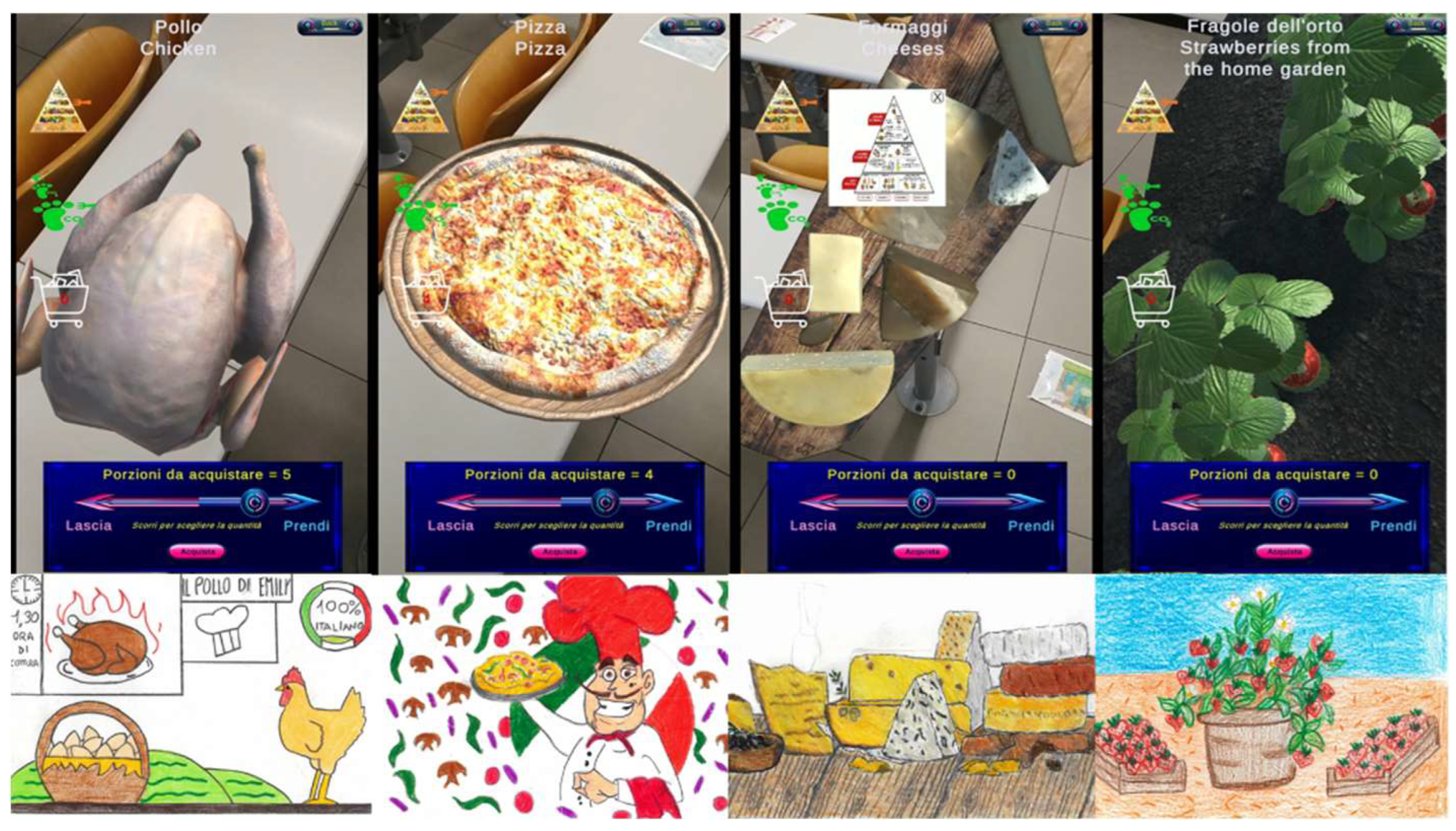

As players progress, they are transported to the heart of the app’s educational core: the virtual supermarket. This immersive environment serves as a dynamic classroom where students can explore and understand the complexities of food choices, nutritional value and environmental impact. Play in the virtual supermarket involves the use of target cards designed by the students themselves. When scanned, these cards reveal detailed 3D models of a wide range of food products, adding an immersive dimension to the learning experience (

Figure 1).

The supermarket is meticulously organized into different food categories with different nutritional value and ecological footprint: Processed and packaged products, Fresh vegetable and animal products, Organic or locally sourced foods, Home Garden Section. A unique feature of the ARFood supermarket, this area allows students to engage with life-size 3D models of vegetable crops. Players can simulate food production and consumption at home, highlighting the joys and benefits of growing your own food and promoting sustainable living practices. By navigating these categories, students can understand the multifaceted nature of food consumption and its broader implications for personal health and environmental sustainability.

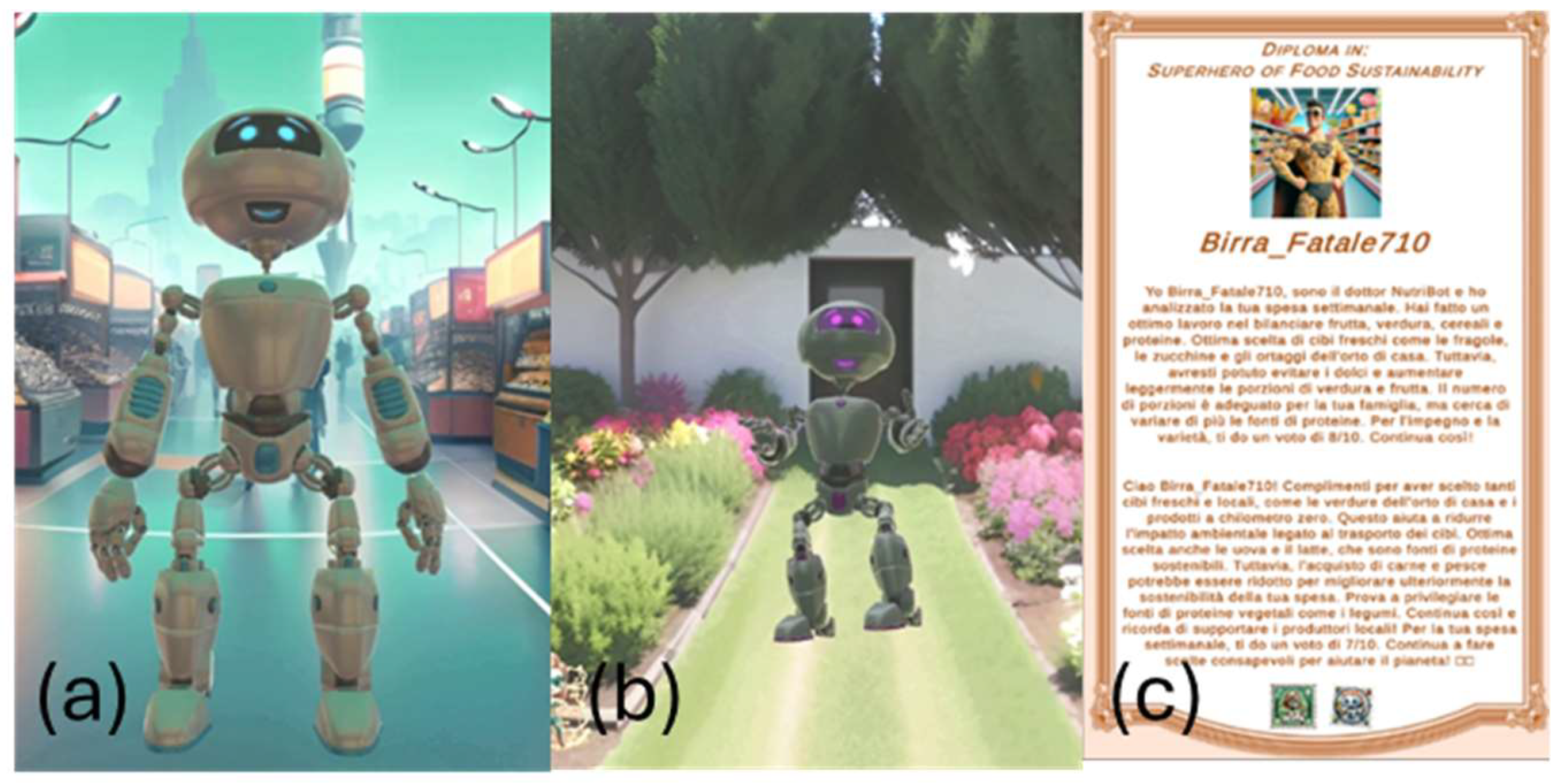

At the end of the shopping experience, players’ choices are evaluated by the two NPCs: NutriBot and CyberFlora. These characters were designed with distinct personalities and communication styles to resonate with young audiences and make the educational content engaging and memorable.

The NutriBot prompt (

Figure 2a) is designed with a lively hip-hop personality in order to engage students through energetic interactions and contemporary, fun and upbeat language. In contrast, the CyberFlora prompt (

Figure 2b) is structured with the essence of New Age wisdom pre offer a calm and reflective perspective on food and sustainability. This character provides insights into the environmental impact of food choices, fostering a deeper understanding of environmental responsibility. Her interactive feedback serves as a personalized nutrition guide, reinforcing ARFood’s educational goals. By adapting their communication to different learning styles, NutriBot and CyberFlora aim to enhance the app’s ability to engage and motivate young learners.

The culmination of the ARFood experience is the delivery of a personalised diploma (

Figure 2c). This diploma is more than just a certificate of completion; it encapsulates the player’s educational journey and reflects their learning and achievements during the game. It includes NutriBot and CyberFlora assessments that provide personalised feedback on the player’s choices and progress.

2.2. Methods

The study employs a five-step process to iteratively improve NPCs prompt effectiveness:

Initial Prompt Development: Each NPC is initialized with a base prompt designed to provide feedback aligned with its educational goals.

Data collection: A sample of participants interacts with the app, each generating a virtual shopping cart. Each cart is evaluated twice: once by the nutrition NPC and once by the sustainability NPC.

Educational Objective Decomposition: Nutritional education and sustainability education are each broken down into five specific objectives.

Evaluation Using Zero-Shot RoBERTa classifier: a zero-shot classifier assesses how well the NPCs’ feedback aligns with the predefined educational objectives. For each evaluation, probabilities are assigned to indicate the relevance of the NPCs’ responses to the five objectives.

Prompt Refinement: Based on RoBERTa’s classification results, prompts are modified to emphasize underrepresented objectives. The app then re-evaluates the carts using the updated prompts.

2.2.1. Initial Prompt Development

ARFood was developed in Unity 3D and the integration with the OpenAI API was realized via a wrapper in C# by programming the OpenAI API with the following prompts. The Nutribot message was set with the following parameters:

{ role = “system”, content = “You are a character in a virtual reality serious game app. Introduce yourself as Dr. NutriBot. The purpose of the app is to teach middle school children about nutrition education. You are a virtual nutrition doctor. You must judge a weekly shopping cart that the game participants have virtually purchased and explain what they did right and what they did wrong. You must rate the groceries from 1 to 10. Each cart is a different game participant. Do all the grading in rap style in Italian. Also rate whether the number of servings is appropriate for the family’s weekly needs considering the number of people. Use a maximum of 200 words.”}

The CyberFlora message was set with the following parameters:

{ role = “system”, content = “You are a character in a virtual reality serious game app. Introduce yourself as CyberFlora professor of ecology. The purpose of the app is to teach middle school children about food sustainability and the ecological footprint of foods. You must judge a weekly shopping cart that the game participants have virtually purchased and explain what they did right and what they did wrong. Give a rating solely on ecological sustainability. Don’t do nutritional evaluations. Do the whole evaluation in New Age style. Use a maximum of 200 words.”}

When the player decides to finish shopping and move on to evaluation by the two characters the App generates a text string describing the composition of the chosen family and the contents of the virtual shopping cart. The string constitutes the second argument of the message sent to the OpenAI API. Below is an example of the string.

{ role = “user”, content = “The weekly shopping is for a family of 2 person. My cart contains: 10 servings of fruit. 7 servings of vegetables. 2 servings of bread. 2 servings of pasta. 4 servings of rice. 1 portion of beef. 2 servings of fish. 1 serving of cheese. 3 servings of legumes. 3 servings of pizza. 4 servings of eggs. 2 servings of fruitcake. 1 serving of strawberries from home garden. 1 portion of home garden Zucchini. 1 portion of Peaches from home garden. 1 portion of Home-grown garden salad. 1 portion of home-grown garden tomatoes. 1 portion of Home-grown garden carrots. 2 servings of Km 0 Caciotta cheese. 1 portion of Km 0 oil.” }.

The app was developed in the unity 3D programming environment.

2.2.2. Data Collection

The study involved the recruitment of participants from second- and third-year classes of a middle school. A total of 83 students participated, comprising 50.6% female and 49.4% male, with ages ranging from 12 to 16 years. Each participant engaged with the ARFood app, creating a virtual shopping cart by selecting various food items. The data collected included detailed records of the virtual cart contents, categorized by food type and household size.

After completing their shopping carts, each participant received evaluations from the two AI-powered Non-Player Characters (NPCs). The feedback from the NPCs was recorded separately, capturing both nutritional and sustainability assessments. Once the player’s ratings had been generated by the two NPCs NutriBot and CyberFlora, the app would create a database record containing the player’s nickname, the contents of the shopping basket, and the texts of the nutritional and environmental ratings. The record was sent to the teacher’s email. At the end of the 83 students’ experiences, the records were merged into a single database. The comprehensive dataset summarizing all participants’ shopping cart contents and the corresponding NPC evaluations is included as supplementary material. This dataset serves as the basis for subsequent analyses.

2.2.3. Educational objective decomposition

To ensure comprehensive educational feedback, the objectives for the nutritional NPC, referred to as Nutribot, were divided into eight specific goals.

Healthy Choices: Encouraging users to select nutrient-dense foods over highly processed or sugary options.

Balanced Diet: Promoting a diet that includes appropriate proportions of macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals).

Variety of Foods: Emphasizing the importance of diverse food intake to ensure a well-rounded nutrient profile.

Nutritional Education: Providing foundational knowledge on food labels, nutrient functions, and the benefits of different food groups.

Portion Control: Teaching users how to manage portion sizes to avoid overeating while still meeting nutritional needs.

Snack Quality: Guiding users toward healthier snack options that align with overall dietary goals.

Unhealthy Eating: Identifying and discouraging consumption patterns linked to negative health outcomes, such as excessive intake of sugary beverages or fast food.

Motivation to Healthy Eating: Fostering a positive attitude toward making consistent healthy choices and maintaining long-term dietary improvements.

These objectives aim to guide users toward healthier and more sustainable dietary habits. These dimensions are grounded in evidence-based dietary guidelines, which emphasize the importance of balanced and diverse nutrition for promoting health and preventing chronic diseases. These dimensions reflect core dietary guidelines emphasized by organizations like the World Health Organization [

18] and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics[

19].

The evaluation of serious games in nutrition education aligns with key educational objectives supported by evidence-based practices in health promotion and behavior change. Research indicates that fostering Healthy Choices can significantly reduce the risk of chronic diseases by encouraging nutrient-dense food selections over processed options [

20]. Promoting a Balanced Diet, including appropriate macronutrient and micronutrient ratios, is crucial for maintaining physiological health and preventing nutrient deficiencies, as emphasized in dietary guidelines [

4]. Encouraging a Variety of Foods ensures a comprehensive nutrient intake, a strategy linked to improved overall health outcomes [

5]. Additionally, Nutritional Education through gamified content has been shown to enhance user understanding of food labels and nutrient functions, facilitating informed dietary decisions [

2]. Addressing Portion Control aids in preventing overeating, a key factor in obesity prevention, as outlined by Frederico [

22]. Moreover, guiding users toward higher Snack Quality supports the integration of healthier alternatives into daily habits, aligning with long-term dietary goals. By identifying Unhealthy Eating patterns, serious games can discourage behaviors associated with negative health outcomes, such as high consumption of sugary drinks and fast food [

23]. Lastly, these interventions aim to build Motivation to Healthy Eating, a psychological component critical for sustaining dietary improvements over time [

24]. These dimensions collectively support the use of serious games as an effective tool for advancing nutritional knowledge and fostering healthier eating behaviors.

To effectively assess and improve the educational impact of the app, the concept of environmental sustainability was divided into eight specific objectives, each reflecting a critical aspect of ecological responsibility. These objectives guide the feedback provided by the NPC tasked with sustainability education, named CyberFlora:

Ecological Impact: Encouraging users to consider the broader environmental consequences of their food choices, such as habitat destruction or pollution.

Carbon Footprint: Promoting awareness of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production, transportation, and consumption of selected items.

Use of Sustainable Products: Highlighting the importance of selecting items made with sustainable resources or through environmentally friendly practices.

Waste Reduction: Teaching strategies to minimize food and material waste, emphasizing responsible consumption and proper disposal methods.

Support for Local Products: Advocating for locally sourced items to reduce transportation emissions and support regional economies.

Biodiversity Support: Encouraging choices that protect or enhance biodiversity, such as avoiding products linked to monoculture farming or deforestation.

Minimizing Packaging Waste: Highlighting the importance of selecting products with minimal or eco-friendly packaging to reduce plastic and non-biodegradable waste.

Organic Food Preference: Promoting the selection of organic products, which are grown without synthetic pesticides or fertilizers, contributing to healthier ecosystems.

Each of these objectives is integrated into the NPC’s evaluation framework, ensuring that feedback aligns with specific, actionable goals. This decomposition allows for a focused and measurable approach to sustainability education, providing users with comprehensive guidance on improving their environmental impact through informed shopping decisions.

The integration of sustainability objectives into serious games is supported by a growing body of literature highlighting their potential to enhance educational outcomes. Serious games effectively foster environmental awareness by blending entertainment with educational content, thus engaging users in active learning processes. For instance, Lameras et al. [

25] found that games designed around sustainability themes can significantly improve users’ understanding of ecological issues and promote conceptual shifts toward sustainable thinking. Similarly, Hallinger et al. [

26] emphasize the importance of incorporating diverse sustainability dimensions—environmental, economic, and social—into game-based learning to achieve holistic educational impacts.

Moreover, the ability of games to simulate complex systems allows players to explore the interdependencies within ecological and economic frameworks. Katsaliaki and Mustafee [

27] highlight how decision-based games enhance comprehension of sustainable development strategies by immersing users in realistic scenarios. This pedagogical strategy aligns with findings from Fabricatore and López [

28], who observed that interactive games not only improve problem-solving skills but also increase awareness of sustainability principles through engaging gameplay.

The structured feedback provided by game elements, such as the NPC CyberFlora, further ensures that users receive actionable insights aligned with sustainability goals. This feedback mechanism is critical for reinforcing educational content and encouraging behavior change, as indicated by Emblen-Perry [

29], who notes the role of serious games in promoting critical reflection on sustainability practices. These insights underscore the value of serious games as innovative tools for environmental education, capable of transforming abstract sustainability concepts into tangible learning experiences.

2.2.4. Evaluation Using Zero-Shot RoBERTa Classifier

To assess the alignment of the NPCs’ feedback with the predefined educational objectives, a zero-shot classification approach was employed using a RoBERTa-based model.

The zero-shot RoBERTa classifier is an advanced tool designed to classify text without requiring specific training data for unseen classes [

30]. This approach leverages transfer learning, allowing the model to predict labels for entirely new categories based on pre-trained knowledge. Unlike traditional classifiers, zero-shot learning frameworks like RoBERTa extend the scope of applicability by embedding textual entailment, where the input text and potential labels are treated as a natural language inference problem [

31].

The zero-shot RoBERTa classifier is an advanced tool designed to classify text without requiring specific training data for unseen classes. This approach leverages transfer learning, allowing the model to predict labels for entirely new categories based on pre-trained knowledge. Unlike traditional classifiers, zero-shot learning frameworks like RoBERTa extend the scope of applicability by embedding textual entailment, where the input text and potential labels are treated as a natural language inference problem [

31].

RoBERTa operates on the principle of contextual embeddings, enriching classification by understanding the semantic relationships between input text and label descriptions. This capability is particularly useful in evaluating complex domains like nutrition education and sustainability, where predefined labels can be abstract [

32]. For instance, a classifier may assess the probability that an evaluation aligns with specific learning objectives by calculating similarity scores between the textual representations of the evaluation and each learning objective’s definition.

Mathematically, if

T represents the textual input and L represents the label description, the classifier uses a function

P(L|T) to compute the likelihood of

L given

T. This is often framed as:

where E(·) denotes the embedding function, and cos refers to cosine similarity. This probabilistic approach ensures that even without explicit training data for a specific class, the model can infer relationships and provide meaningful classifications [

33].

Overall, zero-shot classification using RoBERTa exemplifies a robust methodology for evaluating learning objectives in domains where traditional labeled datasets are unavailable or infeasible to construct [

34].

In the application of the RoBERTa classifier, the evaluation was based on two sets of 10 educational objectives: nutrition education and food sustainability education. For each evaluation, the classifier assigns likelihoods to each objective within these sets, ensuring that the total probability for each set sums to 1.

This normalization approach can be mathematically expressed as:

where:

P(Oᵢ | T) is the likelihood of the i-th objective given the evaluation T; Oᵢ represents an individual learning objective within the set; the summation ensures that the distribution of probabilities across the objectives for each thematic set adheres to the principle of probability normalization.

The RoBERTa classifier was applied to the two corpora of NPC evaluations using the transforEmotion package in the R software environment [

35].

2.2.5. Prompt Refinement

he prompt refinement phase involved incorporating the educational objectives directly into the programming of the two NPCs, NutriBot and CyberFlora. These objectives were previously used to evaluate the initial, more generic prompts. For NutriBot, the refined prompt explicitly integrated the goals of nutritional education as follows:

{“role” = “system”, “content” = “You are a character in a virtual reality serious game app. Introduce yourself as Dr. NutriBot. The purpose of the app is to teach middle school children about nutrition education. You are a virtual nutrition doctor. You must judge a weekly shopping cart that the game participants have virtually purchased and explain what they did right and what they did wrong. Pay special attention to portion size, portion control, unhealthy eating habits, junk food consumption, and snack quality. Be sure to address whether the portions are too large or too small, if junk food is overrepresented, and whether snacks are nutritious. You must rate the groceries from 1 to 10. Each cart is a different game participant. Do all the grading in rap style. Also, rate whether the number of servings is appropriate for the family’s weekly needs considering the number of people. Use a maximum of 200 words.”}

For CyberFlora, the refined prompt incorporated the goals of food sustainability education:

{“role” = “system”, “content” = “You are a character in a virtual reality serious game app. Introduce yourself as CyberFlora, professor of ecology. The purpose of the app is to teach middle school children about food sustainability and the ecological footprint of foods. You must judge a weekly shopping cart that the game participants have virtually purchased and explain what they did right and what they did wrong. Focus particularly on the carbon footprint of the items, waste reduction, biodiversity support, and whether the food is organic or from a garden. Give a rating solely on ecological sustainability, avoiding nutritional evaluations. Do the whole evaluation in a peaceful, New Age style, using a maximum of 200 words.”}

These refined prompts were applied to the dataset of virtual shopping carts created by 79 students, generating two new sets of evaluations: one for nutritional education and another for sustainability. Both sets of judgments were then re-evaluated using the RoBERTa zero-shot classifier, following the same procedure outlined in

Section 2.2.4. This iterative process ensured that the NPCs’ feedback became more aligned with the educational goals, enhancing the overall pedagogical effectiveness of the app.

3. Results

3.1. The Dataset of Virtual Shopping Carts

3.1.1. Spending Behavior

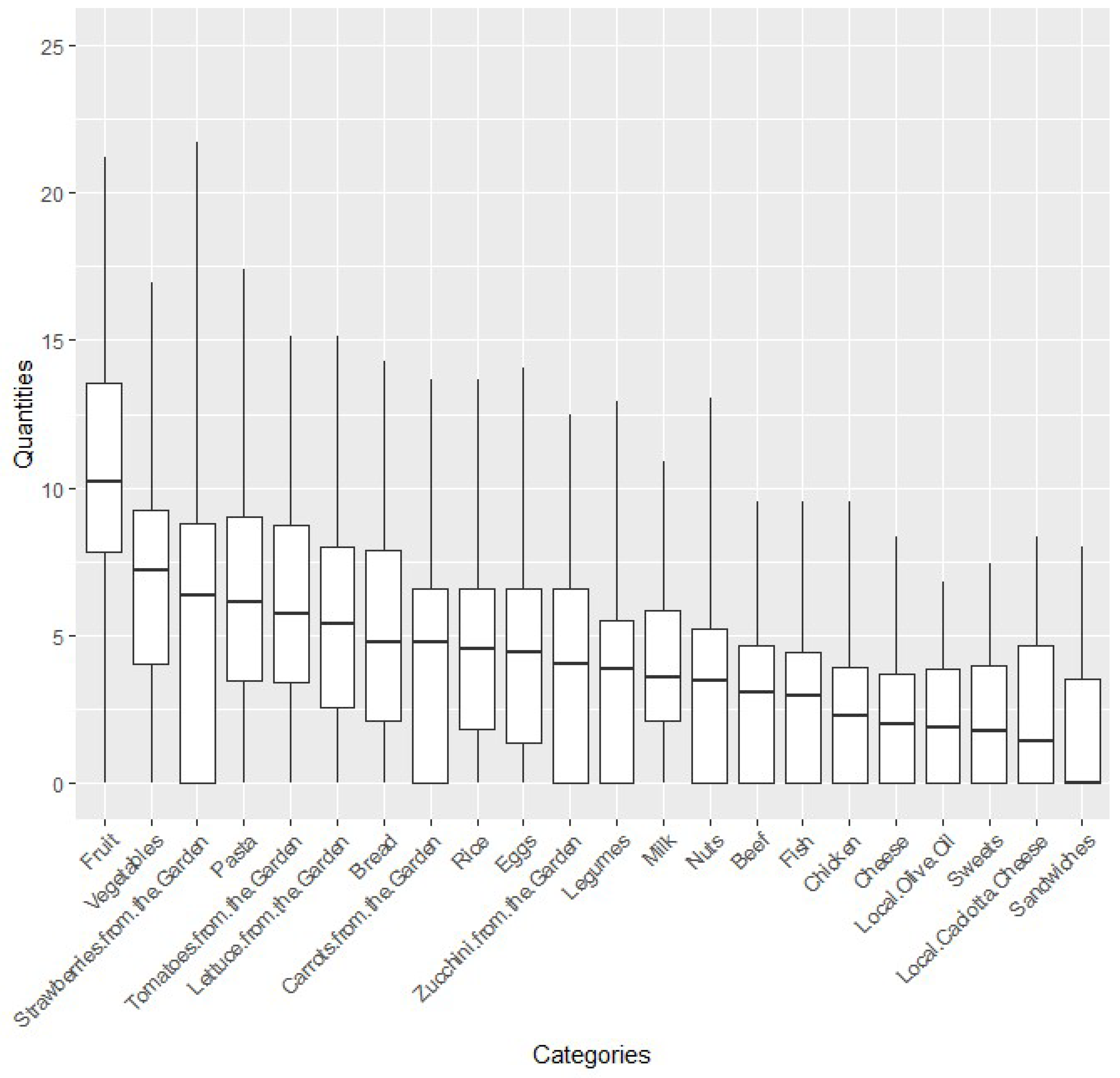

To analyse the shopping behaviour of adolescents using the AR-based serious game app, a standardisation procedure was applied to the data of 83 virtual shopping carts. This procedure normalised the quantity of each product as a percentage of the total products selected in each shopping cart. This step ensured comparability between the different shopping carts, as participants simulated purchases for different time periods, e.g., for daily or weekly needs, and for households with different numbers of members. By standardising the data, preference and allocation patterns could be identified independently of absolute quantities.

Fruit and vegetables emerged as important components in shopping carts (

Figure 3). Fruit accounted for a median of 11.1% and an average of 12.2% of the total cart, with some participants allocating up to 36.1% of their choices to this category. Vegetables were slightly less emphasised, with a median of 7.4% and an average of 7.3%, although the maximum contribution of 33.3% suggests that some adolescents gave high priority to this food group.

Locally grown and garden produce brought a further level of diversity to the trolleys. Items such as strawberries, courgettes, lettuce, tomatoes and carrots were frequently included, with averages of 6.5%, 4.0%, 5.4%, 5.8% and 4.8% respectively. The highest values for strawberries (35.7%) and tomatoes (38.1%) highlight the occasional strong preference for fresh, garden-grown produce. Local specialities, such as caciotta cheese and olive oil, played a minor but distinct role, with median contributions of 1.4% and 1.9% respectively.

Staple foods, including bread, pasta and rice, occupied a significant share of the carts, reflecting their centrality in meal planning. Bread had a median contribution of 4.8% and a mean contribution of 5.4%, with some participants dedicating up to 30% of their trolley to this category. Pasta followed closely, with a median of 6.2% and an average of 6.7%, while rice was slightly less important, with a median of 4.5% and an average of 4.6%. These staples underline the importance of familiar and versatile ingredients in the purchasing decisions of adolescents.

Protein sources showed considerable variability between animal- and vegetable-based options. Animal proteins, such as chicken, beef and fish, were generally less emphasised, with median contributions of 2.3%, 3.0% and 2.9%, respectively. However, the inclusion of fish in particular carts reached 20%, indicating an occasional priority of this category. In contrast, proteins of vegetable origin, such as legumes and nuts, showed a median contribution of 3.8% and 3.5%, respectively. Legumes were present in quantities up to 23.5%, while nuts reached a high of 33.3%, highlighting the potential appeal of these elements in promoting sustainable and healthy eating habits.

Dairy products and sweets played a minor role in shopping carts. Milk represented a median of 3.6%, with maximum contributions reaching 20%, while cheese showed a median of 2.0% and an average of 2.2%. Sweets, although present, were generally not a priority, with a median contribution of 1.7% and a maximum contribution of 19.4%. This suggests that adolescents may have responded to the implicit or explicit encouragement in the application to focus on healthier options.

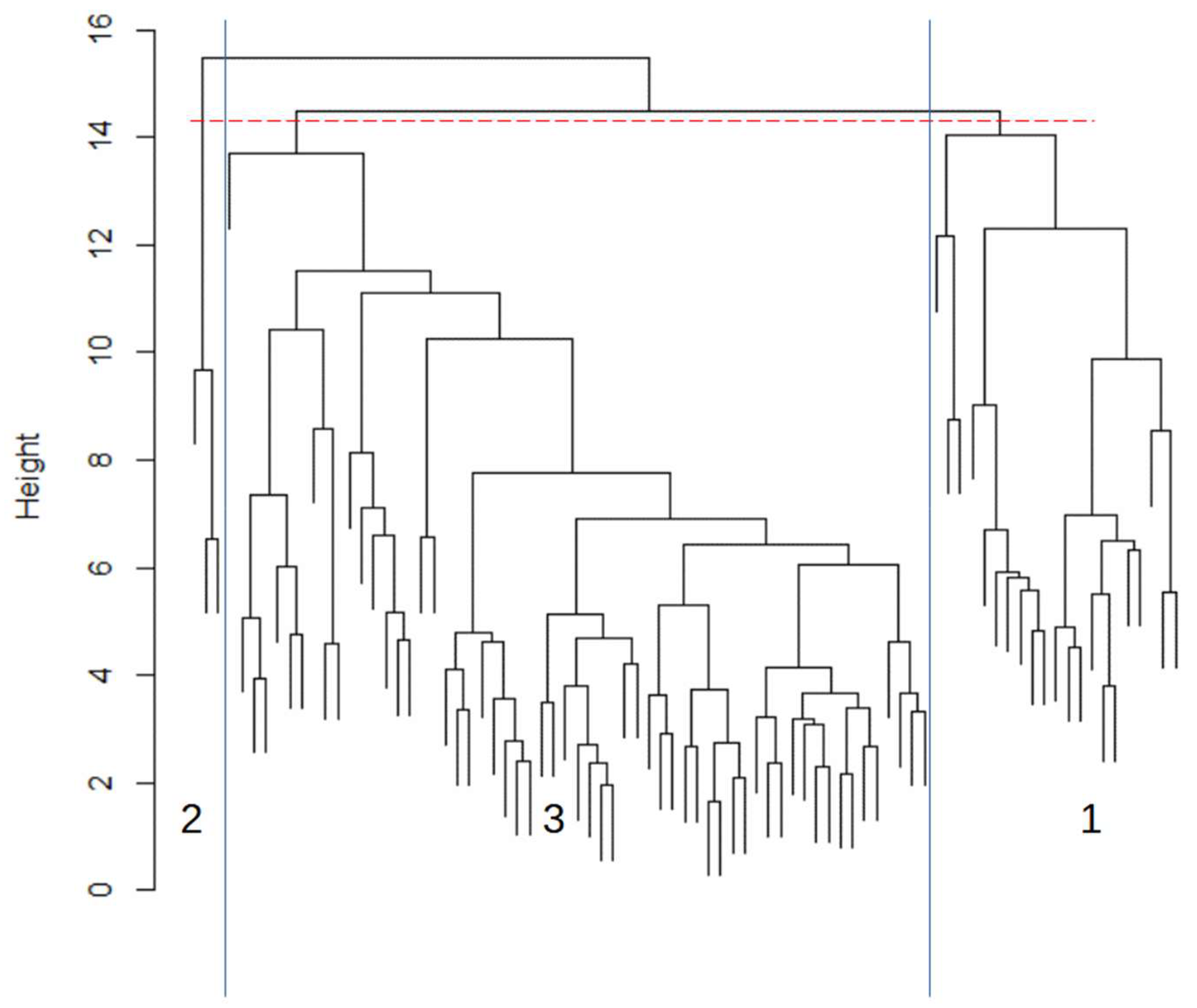

3.1.2. Cluster Analysis

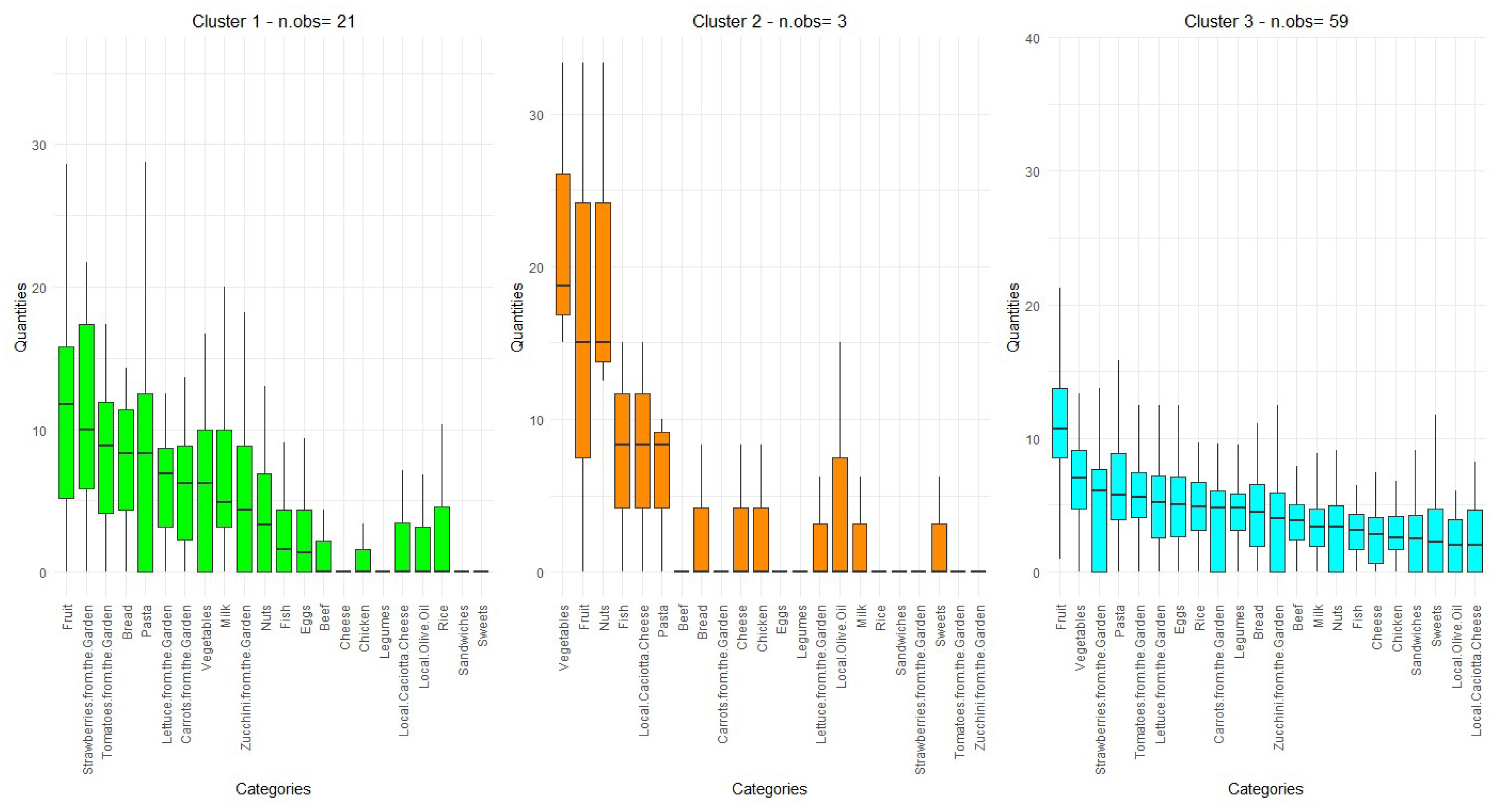

To further the understanding of the spending patterns observed in the 83 virtual shopping carts created by the adolescents with the AR application, a hierarchical clustering analysis was conducted. The standardised dataset, normalised to express the proportion of each product to the total items in the cart, was used to calculate a distance matrix. The Ward.D2 method was applied to the hierarchical clustering process, generating the attached dendrogram. The dendrogram (

Figure 4) revealed the presence of three distinct clusters, comprising 21 observations in cluster 1, 3 observations in cluster 2 and 59 observations in cluster 3.

Cluster 1, comprising 21 observations, reflects a balanced spending behaviour characterised by a moderate emphasis on fruit and vegetables, with median contributions of 11.8% and 6.3% respectively (

Figure 5). Commodities, such as bread and pasta, also occupy a prominent place, with median proportions of 8.3% for both categories. However, protein sources, particularly those of animal origin such as chicken, beef and fish, are minimally represented. The median contributions for these elements are negligible or nil, suggesting a limited focus on these categories. Proteins of vegetable origin, including legumes and nuts, are present but not highly emphasised, with median contributions of 1.5% and 3.8% respectively. In particular, dairy products such as milk have a higher presence, with an average of 6.7%. Locally grown products such as strawberries, tomatoes and courgettes are relatively more important in this cluster, with average contributions of 11.9%, 7.7% and 5.8% respectively, underlining a preference for fresh produce. Local specialities such as olive oil and caciotta cheese have a minimal contribution, with averages of 2.3% and 1.8%.

Cluster 2, comprising only 3 observations, presents a distinctly different pattern, characterised by a high emphasis on fruit and vegetables (

Figure 5). These categories have an average contribution of 16.1% and 22.4% respectively. Dried fruit is another key component, with an average contribution of 20.3%. Commodities such as bread, pasta and rice are largely neglected, with average contributions of 2.8%, 6.1% and 0%, respectively. Animal protein, sweets and dairy products are minimally represented, with negligible or no median values. This cluster is also characterised by the limited inclusion of garden articles and local specialities, which appear in very low proportions or are absent altogether. The spending pattern of Cluster 2 shows a focus on fresh and nutrient-dense categories, potentially reflecting preferences aligned with plant-based or minimalist dietary patterns.

Cluster 3, the largest group with 59 observations, represents a more diverse and balanced spending behaviour (

Figure 5). Fruit and vegetables remain important components, with average contributions of 12.4% and 6.9% respectively. Commodities, including bread, pasta and rice, are moderately represented, with average proportions of 4.8%, 6.3% and 5.4% respectively. Protein sources in this cluster show a more even distribution, with average contributions of 3.1% for chicken, 4.1% for beef and 3.3% for fish. Proteins of vegetable origin, such as legumes and nuts, also play a prominent role, with averages of 4.7% and 3.3%. Sweets, although present, are not a dominant category, with an average of 3.1%. Dairy products, including milk and cheese, have a moderate contribution, with averages of 3.4% and 2.7%. Fruit and vegetables and local specialities have a stronger presence in this cluster than in cluster 2. Items such as strawberries, lettuce and tomatoes contribute with averages of 5.1%, 5.4% and 6.2%, respectively. Local caciotta and olive oil are present in small but significant proportions, with averages of 2.3% and 2.1%.

3.2. Initial Prompt Development

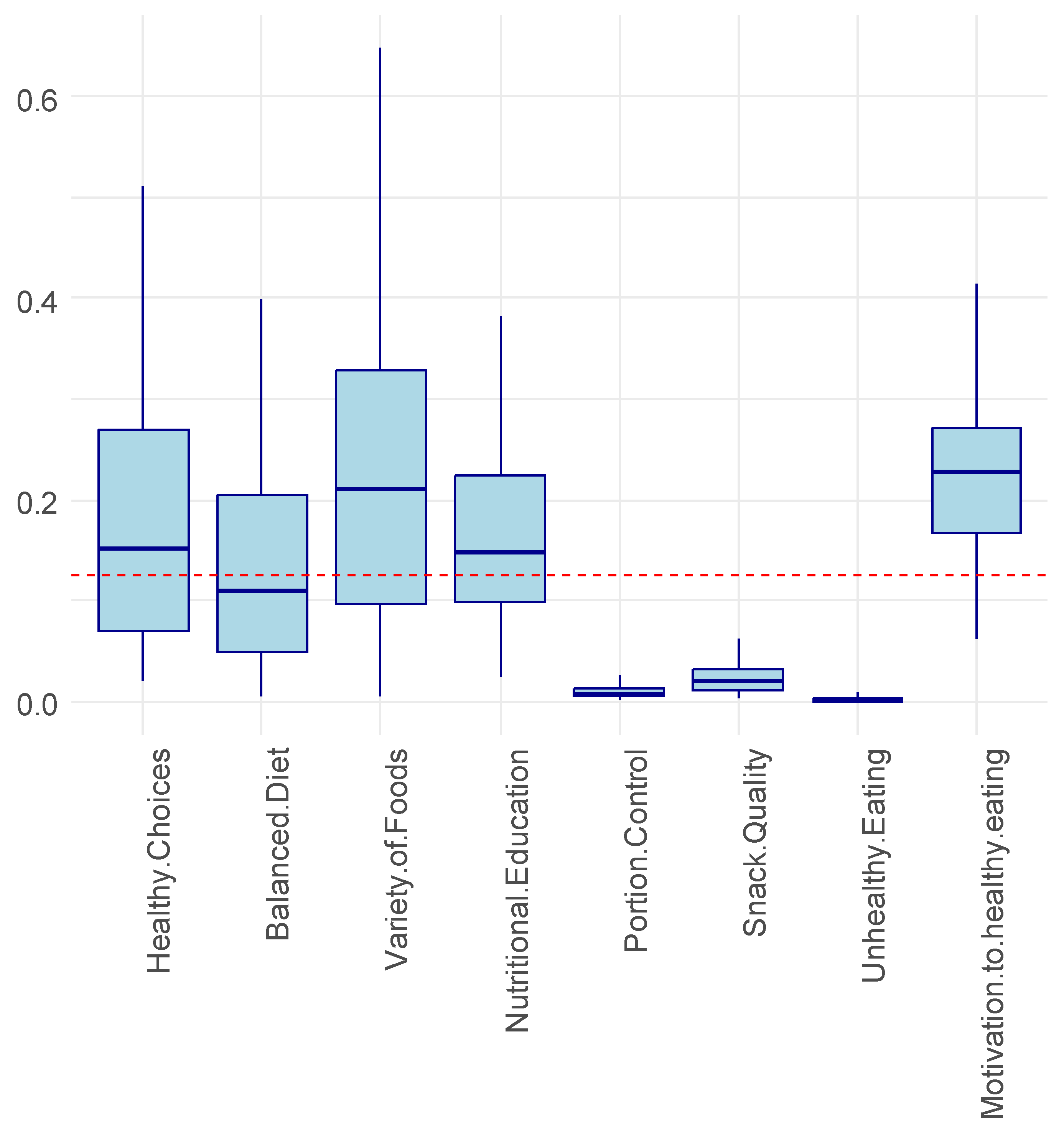

The boxplots in

Figure 6 summarizes NutriBot’s performance in evaluating virtual shopping carts based on eight educational objectives. The results reveal a clear imbalance in how the NPC addresses these objectives under the initial prompt.

Variety of Foods, Nutritional Education, and Motivation to Healthy Eating show the highest levels of engagement. These objectives have relatively high median values (0.21, 0.15, and 0.23, respectively) and broader interquartile ranges, indicating consistent and thorough feedback. The high maximum values for these categories also highlight NutriBot’s strong focus on promoting dietary diversity and motivation for healthier choices.

In contrast, objectives like Portion Control, Snack Quality, and Unhealthy Eating receive significantly less attention, with median values close to zero. Portion Control, in particular, exhibits the lowest coverage, with most evaluations clustering near the minimum. This demonstrates that the initial prompt did not sufficiently guide NutriBot to address these critical aspects of nutrition education.

Additionally, Healthy Choices and Balanced Diet receive moderate attention, with medians of 0.15 and 0.11, respectively. Although these objectives are more consistently covered than the lowest-performing ones, the distribution of scores suggests room for improvement in providing more comprehensive evaluations.

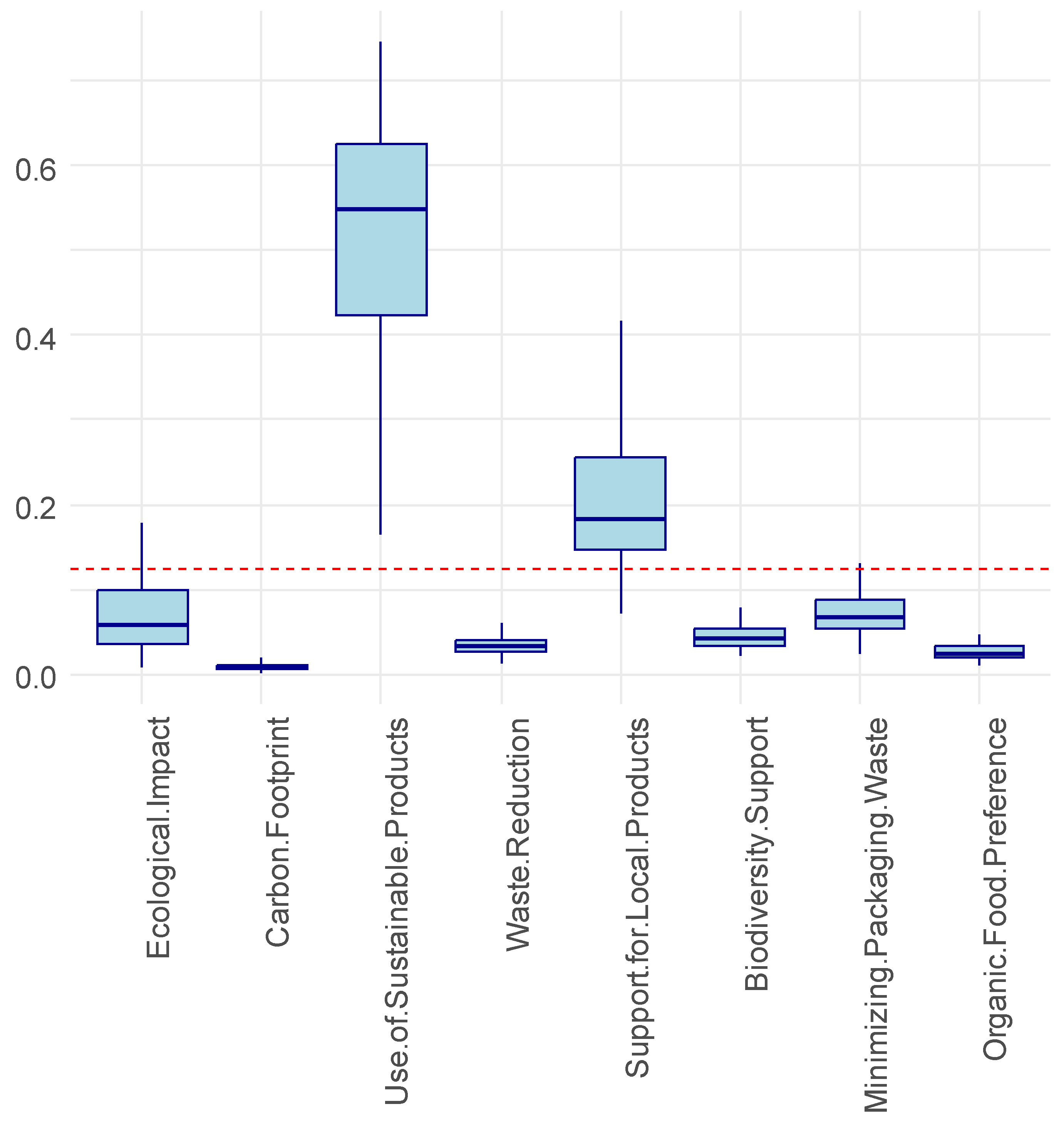

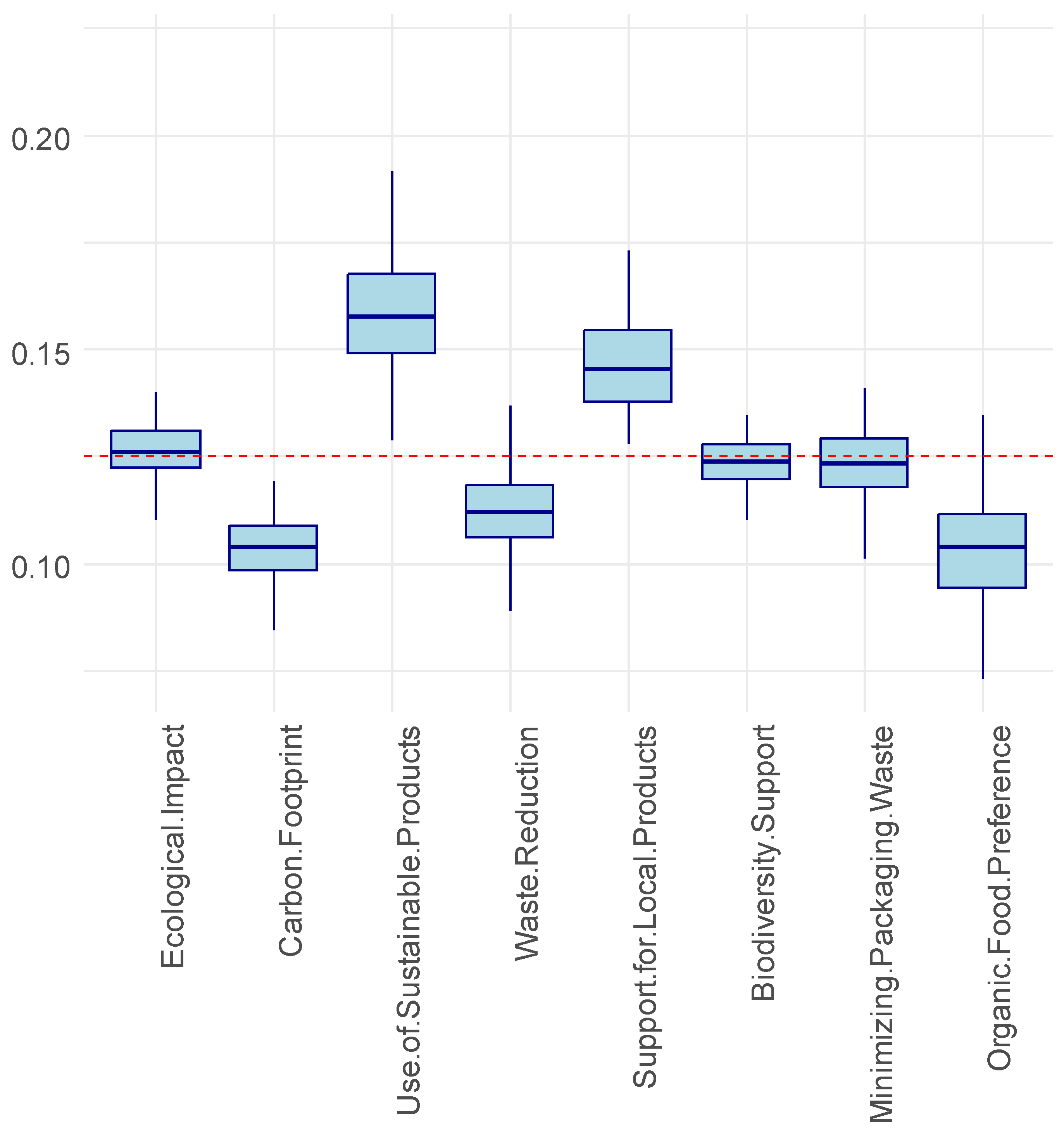

The boxplot analysis provides a detailed overview of CyberFlora’s evaluations across ten ecological objectives using the initial generic prompt (

Figure 7). The boxplot visualizes the distribution of CyberFlora’s evaluations across eight educational objectives, highlighting significant disparities in how the NPC addresses these goals under the initial generic prompt. The red dashed line at 0.125 represents the balanced probability threshold, indicating the level at which all objectives would receive equal attention.

The results show that CyberFlora prioritizes certain objectives disproportionately. Use of Sustainable Products stands out, with a mean probability of 0.5155 and a median of 0.5475, significantly exceeding the balanced threshold. Similarly, Support for Local Products also shows relatively high coverage, with a mean of 0.2100.

In contrast, several objectives fall well below the balanced threshold. Carbon Footprint, with a mean of 0.0096 and a median of 0.0079, and Ecological Impact, with a mean of 0.0709, are notably underrepresented. Waste Reduction, Biodiversity Support, and Organic Food Preference also display low probabilities, indicating limited focus on these critical aspects of sustainability.

These findings suggest that the initial prompt guides CyberFlora to emphasize specific aspects of sustainability, particularly the use of sustainable and local products, while neglecting other equally important goals such as reducing carbon footprint and promoting biodiversity. This imbalance underscores the necessity of refining the prompt to ensure more comprehensive coverage across all educational objectives.

3.3. Prompt Refinement

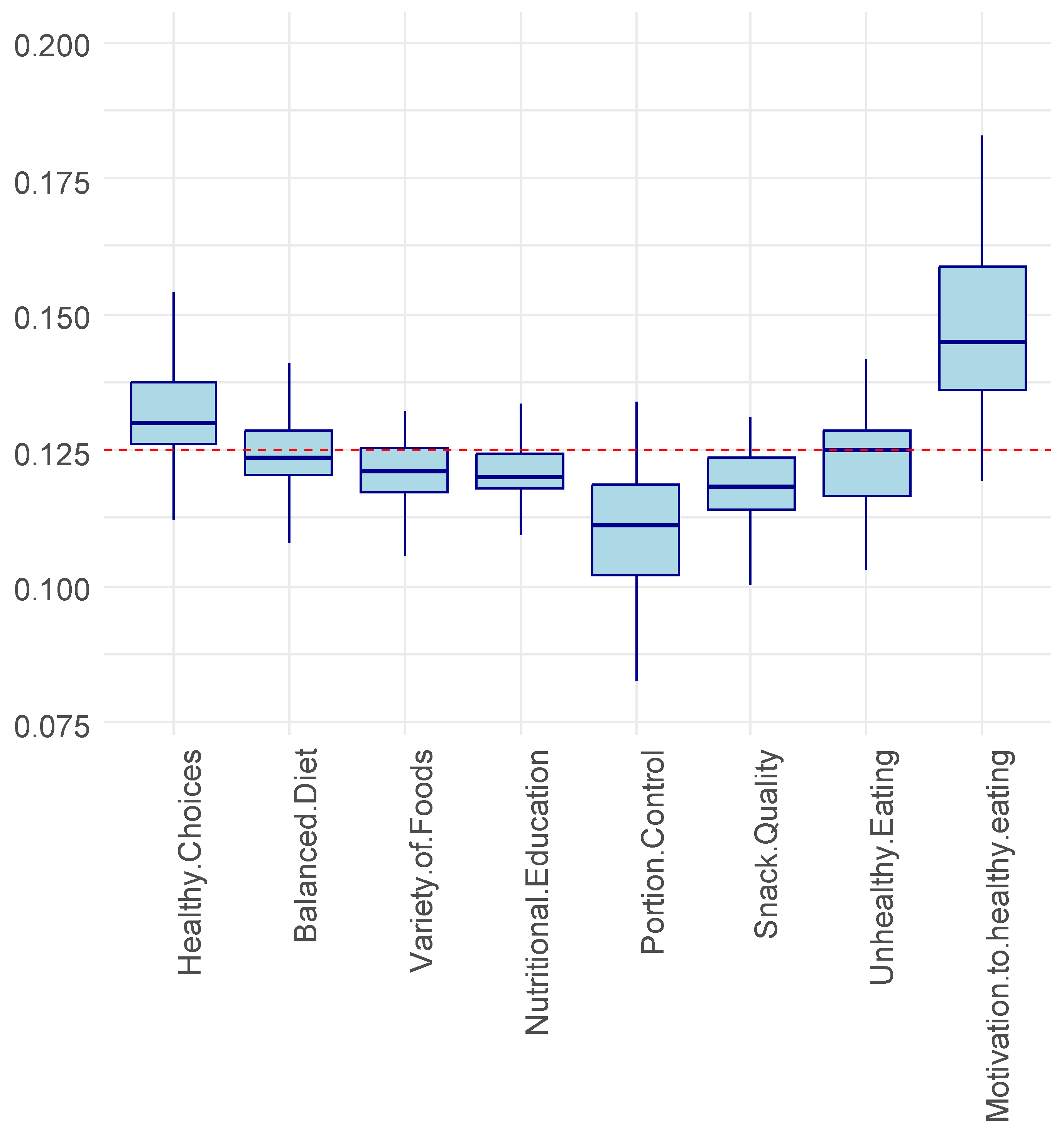

The graph in

Figure 8 presents the distribution of NutriBot’s evaluations across eight educational objectives after refining the prompt to explicitly incorporate these goals. The refined prompt led to a more balanced coverage of all objectives, as evidenced by the distribution of probabilities aligning closely around the equipartition probability of 0.125 (indicated by the red dashed line).

Compared to the evaluations from the original generic prompt, where some objectives were overemphasized while others were largely neglected, the refined prompt ensured a more even representation. The boxplots show that the median probabilities for all eight objectives, including Healthy Choices, Balanced Diet, Variety of Foods, Nutritional Education, Snack Quality, Unhealthy Eating, Portion Control, and Motivation to Healthy Eating, hover near 0.125. Furthermore, the interquartile ranges (IQRs) are narrow and consistent, indicating low variability and stable performance across different evaluations.

This improvement underscores the success of the refined prompt in guiding NutriBot to deliver comprehensive feedback. The probability that NutriBot addresses each educational objective is now more evenly distributed, ensuring that all key aspects of nutritional education are adequately covered. This balanced feedback enhances the app’s effectiveness in promoting a holistic understanding of healthy eating among its users.

The boxplot in

Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of CyberFlora’s evaluations across eight educational objectives after refining the prompt to explicitly incorporate these targets. The refined prompt yields significantly more balanced feedback compared to the initial generic prompt. The median values for all objectives, including Ecological Impact, Carbon Footprint, Use of Sustainable Products, Waste Reduction, Support for Local Products, Biodiversity Support, Minimizing Packaging Waste, and Organic Food Preference, are consistently close to the theoretical equipartition probability of 0.125 (1/8). This is highlighted by the red dashed line in the graph. The variability, as reflected by the interquartile ranges, is relatively low across objectives, suggesting that CyberFlora’s evaluations are now evenly distributed. No single objective dominates, and none are significantly underrepresented. For instance, Carbon Footprint, Support for Local Products, and Biodiversity Support maintain similar probabilities to Waste Reduction and Organic Food Preference, showing that the NPC addresses each aspect of sustainability education with comparable frequency.

These findings mirror those observed with NutriBot’s refined prompt. The explicit integration of educational objectives leads to a more holistic and equitable evaluation process. This refined design ensures that CyberFlora provides feedback that thoroughly covers all key sustainability goals, thereby enhancing the educational impact of the app.

4. Discussion

The integration of Augmented Reality (AR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) in education has shown great promise in addressing complex topics such as nutritional health and environmental sustainability, as evidenced by the ARFood app. The results of this study support its potential as an effective tool for engaging Generation Alpha in these critical areas.

In response to RQ1, the use of AR technology facilitated a realistic and engaging simulation, promoting user interaction and retention of educational content.

Overall, the virtual shopping cart data reveal a balanced allocation of resources among the major food groups, with fruit and vegetables consistently favoured. The inclusion of staples such as bread, pasta and rice reflects a practical approach to meal composition, while the relatively low emphasis on animal protein suggests an intentional preference for plant-based options or the influence of the app’s educational design. The presence of sweets and processed foods was significantly limited, which probably reflects both the app’s objectives and the engagement of adolescents with its framework for healthy eating.

This shopping pattern also has significant implications for environmental sustainability. The priority given to plant-based foods such as fruit, vegetables, legumes and nuts over animal-based proteins is in line with dietary patterns that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and resource use. In addition, the emphasis on locally grown produce and gardens supports sustainable agricultural practices, minimising transport-related emissions and fostering links with local food systems. By placing little emphasis on high-impact foods, such as beef and processed products, the adolescents in this study demonstrate a potential alignment with environmentally conscious consumption patterns. These findings highlight the role that gamified educational interventions can play in promoting not only healthier but also more sustainable eating behaviours, contributing to broader efforts in promoting sustainable food systems. Further research could explore the long-term impact of such interventions on environmental attitudes and purchasing habits in the real world.

Cluster analysis reveals distinct spending patterns among the three groups of adolescents. Cluster 1 shows a balanced but low-protein spending behaviour, with a preference for fresh produce. Cluster 2 emphasises fruit, vegetables and nuts, reflecting a minimalist, vegetable-oriented approach. Cluster 3, on the other hand, shows a varied and balanced pattern, integrating a wide range of food categories, including plant- and animal-based options. These results underline the potential of the AR serious game application to accommodate and reflect diverse food preferences, providing an educational platform that aligns with both individual choices and broader sustainability goals.

In response to RQ2, the identification of specific educational goals in nutrition and sustainability verified that simplified hip-hop style prompts for Nutribot and New Age style prompts for CyberFlora allowed for partial and limited alignment with the identified educational dimensions. Results from evaluating NutriBot ratings with the RoBERTa classifier confirm that the initial prompt strongly emphasizes fruit and vegetable balance, dietary diversity, and local and homegrown products, while consistently neglecting goals such as portion control, variety of protein sources, and whole foods and grains. These shortcomings underscore the need for immediate refinement to ensure that NutriBot provides a more comprehensive assessment of all educational objectives, thereby improving its effectiveness as an educational tool.

The uneven distribution of the relevance of CyberFlora’s ratings to the dimensions of food sustainability indicates that while the initial prompt was successful in eliciting responses related to some high-level sustainability goals, it failed to comprehensively address others.

The identified gaps highlight the need for targeted and detailed prompt design to ensure balanced coverage of all educational goals. This finding underscores the importance of refining prompts to achieve a more holistic and effective educational experience.

Addressing RQ3, the iterative process proved instrumental in refining NPC responses to better align with educational objectives. For instance, NutriBot’s focus on underrepresented goals such as portion control and snack quality improved markedly with refined prompts, leading to a more holistic coverage of critical nutritional aspects. This improvement is evidenced by a significant increase in the alignment of feedback with predefined educational targets, highlighting NutriBot’s enhanced ability to guide users toward healthier dietary habits. Similarly, CyberFlora achieved more balanced coverage across all sustainability objectives, addressing prior gaps in areas like waste reduction and biodiversity support. These refinements underscore the effectiveness of iterative evaluations, demonstrating how targeted adjustments can optimize the educational value of AI-driven tools. Moreover, the process highlights the adaptability of such technologies in evolving educational landscapes, ensuring their relevance and efficacy in addressing diverse learning needs. This study highlights that the educational objectives were successfully achieved while preserving NutriBot’s hip-hop style and CyberFlora’s new-age tone. This demonstrates the feasibility of combining accuracy and comprehensiveness of educational content with an engaging and dynamic communication style. The findings underscore the effectiveness of well-designed and rigorously tested prompts in delivering educational messages in a manner that is both informative and appealing to the target audience.

The findings of this study align with existing literature on the use of Augmented Reality (AR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) in education, particularly in the domains of nutrition and personalized learning.

The ARFood app’s use of AR to create engaging and realistic simulations for teaching nutritional health is consistent with the conclusions of Yigitbas and Mazur [

36], who found that AR and Virtual Reality (VR) technologies effectively support healthy eating by providing additional product information and new learning applications. Similarly, McGuirt et al. [

37] highlighted the potential of Extended Reality (XR) technologies to increase the accessibility and attractiveness of nutrition education programs, which aligns with ARFood’s approach to engaging Generation Alpha.

The iterative refinement of AI-based Non-Player Characters (NPCs) in ARFood to provide personalized feedback aligns with findings by Maghsudi et al. [

38], who noted that AI in higher education is used for assessment, evaluation, and intelligent tutoring systems, thereby enhancing personalized learning experiences.

The study’s iterative process to refine NPC responses for better alignment with educational objectives reflects the adaptability of AI-driven educational tools. The results obtained confirm that the correct wording of prompts is crucial in the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in education, as it directly affects the quality and relevance of the responses generated. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of this practice. For example, Denny et al. [

40] introduced the concept of ‘Prompt Problems’ to help students develop skills in creating effective prompts for code generators based on large language models (LLM). Furthermore, Ng and Fung [

41] have shown that the careful design of prompts, including specific information about learners, effectively guides AI in generating coherent and pedagogically sound learning paths, improving the effectiveness of personalised instruction.

The ARFood app not only aligns with existing research on the use of Augmented Reality (AR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) in education but also extends these findings in several significant ways. While previous studies have explored the use of AR and AI for nutrition education, ARFood uniquely combines these technologies to address both nutritional health and environmental sustainability. By guiding users toward balanced diets and eco-friendly food choices, ARFood provides a holistic educational experience that encompasses multiple dimensions of well-being. ARFood employs AI-based Non-Player Characters (NPCs) that offer tailored feedback on users’ food selections, enhancing the personalization of the learning experience. This approach builds upon existing research by demonstrating the effectiveness of AI in delivering customized educational content, thereby increasing user engagement and knowledge retention. The development of ARFood involved an iterative process to refine NPC feedback, ensuring alignment with educational objectives. This method not only improved the quality of information provided but also showcased the adaptability of AI-driven educational tools in meeting diverse learning needs. By incorporating gamified elements and immersive AR experiences, ARFood effectively engages Generation Alpha, catering to their digital proficiency and learning preferences. This strategy enhances motivation and participation, addressing challenges identified in previous studies regarding student engagement in educational programs.

However, this study has limitations. The sample size, while sufficient for initial analysis, may not generalize to broader populations. Additionally, the reliance on a single zero-shot classification model might overlook nuanced feedback gaps. The absence of longitudinal data limits insights into long-term behavioral impacts. Addressing these limitations in future research could involve expanding the participant base, incorporating diverse AI models, and conducting longitudinal studies to assess the sustainability of the observed educational benefits.

Future developments could include integrating adaptive learning mechanisms to tailor feedback dynamically based on individual user progress. Expanding the application to address other sustainability and health topics, such as water conservation or physical activity, could further enhance its educational value. Finally, collaborative features enabling peer interaction might enrich the learning experience and foster collective awareness.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the integration of Augmented Reality (AR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the ARFood app, designed to educate Generation Alpha about nutritional health and environmental sustainability. By evaluating virtual shopping cart behaviors and refining AI-driven NPC feedback, the app effectively aligned with predefined educational objectives. Key results include the successful application of iterative prompt refinement, leading to comprehensive coverage of nutritional and sustainability goals.

The findings underscore ARFood’s potential to enhance user engagement and learning outcomes through immersive and adaptive technologies. Users demonstrated improved awareness and decision-making regarding balanced diets and sustainable food practices. Despite some limitations, such as sample size and the need for longitudinal data, the study provides a robust framework for future developments in educational serious games.

ARFood’s innovative approach highlights the possibilities for leveraging AR and AI in educational contexts. By addressing current gaps and expanding its scope, this framework could inspire broader applications, ultimately contributing to the development of informed, sustainability-conscious generations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C., T.B., M.B. and I.B.; methodology, I.B.; software, I.B. and M.B.; validation, I.C., I.B. and T.B.; data curation, I.B.; and T.B. writing—original draft preparation, I.B.; writing—review and editing, I.B.; visualization, T.B.; supervision, I.C.; project administration, I.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the University of Florence Ethics Committee exempted our research from obtaining ethical clearance because it was not an interventional or medical study.

Informed Consent Statement

The serious game was presented as an anonymous survey and therefore, according to EU laws, informed consent was not required. At the time of collecting the requested information, this information is not associated with the student’s personal data.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are included as supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the Principal Valeria Bonatti and the teaching staff of Istituto comprensoriale statale Giovanni Falcone e Paolo Borsellino in Gavorrano (GR). for their invaluable support and collaboration. Their dedication and commitment to education have greatly contributed to the success of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Paramita, A., Yulia, C., & Nikmawati, E. E. (2021, March). Augmented reality in nutrition education. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 1098, No. 2, p. 022108). IOP Publishing.

- McMahon, M., & Henderson, S. (2011). Enhancing nutritional learning outcomes within a simulation and pervasive game-based strategy. In S. de Freitas, & P. Maharg (Eds.), Digital games and learning (pp. 131-143). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Barwood, D., Smith, S., Miller, M. R., Boston, J., Masek, M., & Devine, A. (2020). Transformational game trial in nutrition education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 45(4). [CrossRef]

- Camacho, S., & Guevara, R. (2014). Augmented reality and simulation in dietetics education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 46(4), S77-S78. [CrossRef]

- Leong, C., Liesaputra, V., Morrison, C., Parameswaran, P., Grace, D., Healey, D., Ware, L., Palmer, O., Goddard, E., & Houghton, L. (2021). Designing video games for nutrition education: A participatory approach. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 53(7), 613-620. [CrossRef]

- Pilut, J., Litchfield, R., Hollis, J., Lanningham-Foster, L., & Wolff, M. (2021). Virtual reality grocery store tour: Impact on nutrition education and self-efficacy. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 121(9), A17. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, P., Khot, R. A., & Mueller, F. F. (2018, March). “ You Better Eat to Survive” Exploring Cooperative Eating in Virtual Reality Games. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (pp. 398-408).

- Plechatá, A., Morton, T., Perez-Cueto, F. J., & Makransky, G. (2022). A randomized trial testing the effectiveness of virtual reality as a tool for pro-environmental dietary change. Scientific reports, 12(1), 14315.

- Fritz, W., Hadi, R., & Stephen, A. (2023). From tablet to table: How augmented reality influences food desirability. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 51(3), 503-529.

- Garcia, M. B. (2023). ChatGPT as a virtual dietitian: Exploring its potential as a tool for improving nutrition knowledge. Applied Sciences, 6(5), 96. [CrossRef]

- Ray, P. (2023). Is ChatGPT really helpful for nutrition and dietetics? Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 123(10), 593–598. [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D., van Eijnatten, E. J. M., & Camps, G. (2023). Comparison of answers between ChatGPT and human dieticians to common nutrition questions. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2023, 5548684. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V., Jafri, F., Kareem, N. A., Aboobacker, R., & Noora, F. (2024). Evaluation of accuracy and potential harm of ChatGPT in medical nutrition therapy: A case-based approach. F1000Research, 13, 137. [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. (2023). ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: Systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. Healthcare, 11(6), 887. [CrossRef]

- Lo, C. (2023). What is the impact of ChatGPT on education? A rapid review of the literature. Education Sciences, 13(4), 410. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P., Alba, R., Krisanapan, P., Acharya, C. M., Suppadungsuk, S., Csongrádi, É., Mao, M., Craici, I. M., Miao, J., Thongprayoon, C., & Cheungpasitporn, W. (2024). AI-driven patient education in chronic kidney disease: Evaluating chatbot responses against clinical guidelines. Diseases, 12(8), 185. [CrossRef]

- Güner, E., & Ülker, M. T. (2024). Can artificial intelligence replace dietitians? A conversation with ChatGPT. Journal of Food and Nutrition Guidance, 4(2), 2474. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2020). Guideline: Dietary guidelines and principles for healthy eating. Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565716.

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. (2021). Nutrition and health promotion. Retrieved from https://www.eatright.org/.

- Barwood, D., Smith, S., Miller, M. R., Boston, J., Masek, M., & Devine, A. (2020). Transformational game trial in nutrition education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 45(4). [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M., & Henderson, S. (2011). Enhancing nutritional learning outcomes within a simulation and pervasive game-based strategy. In Handbook of Research on Improving Learning and Motivation through Educational Games: Multidisciplinary Approaches (pp. 126-141). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Frederico, C. (2012). Results of a dietitian survey about nutrition games. Games for Health Journal, 1(1), 44-48. [CrossRef]

- Pilut, J., Litchfield, R., Hollis, J., Lanningham-Foster, L., & Wolff, M. (2021). Virtual reality grocery store tour: Impact on nutrition education and self-efficacy. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 121(9), A84. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M. B. (2023). ChatGPT as a virtual dietitian: Exploring its potential as a tool for improving nutrition knowledge. Applied System Innovation, 6(5), 96. [CrossRef]

- Lameras, P., Petridis, P., & Dunwell, I. (2014). Raising awareness on sustainability issues through a mobile game. Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Interactive Mobile Communication Technologies and Learning (IMCTL), 107–112. [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., Wang, R., Chatpinyakoop, C., Nguyen, V. T., & Nguyen, U. P. (2020). A bibliometric review of research on simulations and serious games used in educating for sustainability, 1997–2019. Journal of Cleaner Production, 120358. [CrossRef]

- Katsaliaki, K., & Mustafee, N. (2015). Edutainment for sustainable development. Simulation & Gaming, 46(6), 647–672. [CrossRef]

- Fabricatore, C., & López, X. (2018). Enhancing student engagement in business sustainability through games. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 19(3), 635–650. [CrossRef]

- Emblen-Perry, K. (2018). Enhancing student engagement in business sustainability through games. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 19(3), 635–650. [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y. L. (2024). Market intelligence applications leveraging a product-specific Sentence-RoBERTa model. Applied Soft Computing, 165, 112077.

- Lake, T. (2022). Flexible job classification with zero-shot learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.12678. [CrossRef]

- Gera, A., Halfon, A., Shnarch, E., Perlitz, Y., Ein-Dor, L., & Slonim, N. (2022). Zero-shot text classification with self-training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.17541. [CrossRef]

- Daghaghi, S., Medini, T., & Shrivastava, A. (2019). Semantic similarity based softmax classifier for zero-shot learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.04790. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.04790.

- Wang, W., Zheng, V., Yu, H., & Miao, C. (2019). A survey of zero-shot learning. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST), 10(2), 1-37. [CrossRef]

- Tomašević, A., Christensen, A., & Golino, H. (2024). transforEmotion: Sentiment Analysis for Text, Image and Video using Transformer Models (Version 0.1.5) [Software]. Available at https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=transforEmotion.

- Yigitbas, E., & Mazur, J. (2024, June). Augmented and Virtual Reality for Diet and Nutritional Education: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments (pp. 88-97).

- McGuirt, J. T., Cooke, N. K., Burgermaster, M., Enahora, B., Huebner, G., Meng, Y., ... & Wong, S. S. (2020). Extended reality technologies in nutrition education and behavior: comprehensive scoping review and future directions. Nutrients, 12(9), 2899.

- Maghsudi, S., Lan, A., Xu, J., & van Der Schaar, M. (2021). Personalized education in the artificial intelligence era: what to expect next. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 38(3), 37-50.

- St-Hilaire, F., Vu, D. D., Frau, A., Burns, N., Faraji, F., Potochny, J., ... & Kochmar, E. (2022). A new era: Intelligent tutoring systems will transform online learning for millions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.03724.

- Denny, P., Leinonen, J., Prather, J., Luxton-Reilly, A., Amarouche, T., Becker, B. A., & Reeves, B. N. (2023). Promptly: Using prompt problems to teach learners how to effectively utilize ai code generators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.16364.

- Ng, C., & Fung, Y. (2024). Educational Personalized Learning Path Planning with Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.11773.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).