Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Radiotherapy as a Mainstream Procedure for the Treatment of Cancer Pain

- Brachytherapy (BRT) is a form of localized RT used to treat various types of cancer, which involves placing a radioactive source directly inside or very close to the tumor. This allows for high doses of radiation to be delivered directly to the cancerous tissue simultaneously minimizing radiation exposure to surrounding healthy tissues. The localized radiation can help shrink tumors, alleviate obstruction, and reduce inflammation, which can lead to significant pain relief [6]. This technique is particularly effective in cases where cancer causes localized pain due to soft tissue masses, for instance in head and neck cancers, prostate cancers, gynecological malignancies [7]. Sometimes BRT is used to treat painful bone metastases, particularly in areas like the spine, pelvis or other bones where radiation can be delivered precisely [8]. In cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, or reproductive organs, BRT can be used to treat obstruction-related pain, especially when tumors are pressing on other organs or nerves. Various radioactive isotopes are used in BRT, such as iridium-192 (192Ir), cesium-137 (137Cs), cobalt-60 (60Co), radium-226 (226Ra), or yttrium-90 (90Y), which are placed in close proximity to the tumor for a strictly defined period of time. The various types of BRT are described in Table 1.

- 2.

- The mechanism of action in radioisotope therapy is radiation-induced destruction of cells, which is a technique that differs slightly from that of RT. In radioisotope therapy, the most commonly used elements are strontium-89 (89Sr), samarium-153 (153Sm), phosphorus-32 (32P), radium-223 and (alpharadium) [16,17,18], as described in Table 2. The most widely used strontium isotope is an analog of calcium and selectively accumulates in metastatic lesions in the bones [19,20]. The therapeutic action is based on the emission of beta radiation, which destroys cancer cells with minimal damage to the surrounding healthy tissues [21]. The most common indication for the use of radioactive strontium isotopes is multiple, painful bone metastases that cannot be irradiated with external sources (teletherapy) due to their extensive distribution. The effects of isotopic therapy last from 3 to 12 months, and the onset of action may not become apparent until several weeks after the treatment. Occasionally, before the therapeutic effect occurs, there may be a transient increase in pain symptoms, in which case the patient may require a temporary increase in analgesic doses [22,23]. Isotope treatment can be used in combination with RT, provided there is an appropriate time interval after prior monitoring of blood morphological parameters.

3. The Molecular Mechanism of Radiotherapy

4. Radiotherapy as a Painkiller

4.1. Radiotherapy as a Mainstage Procedure in Painful Metastatic Bone Cancer

- bone pain resulting from the presence of metastatic lesions, e.g., in the spine

- osteolytic metastases with significant bone loss that threaten fractures

- conditions following pathological bone fractures

4.2. Radiotherapy as an Effective Analgesic Procedure in Advanced Head and Neck Cancer Patients

4.3. Radiotherapy as an Effective Procedure in Inflammatory Joint Diseases

4.4. Pain Flares

4.5. Factors Predicting RT Effectiveness

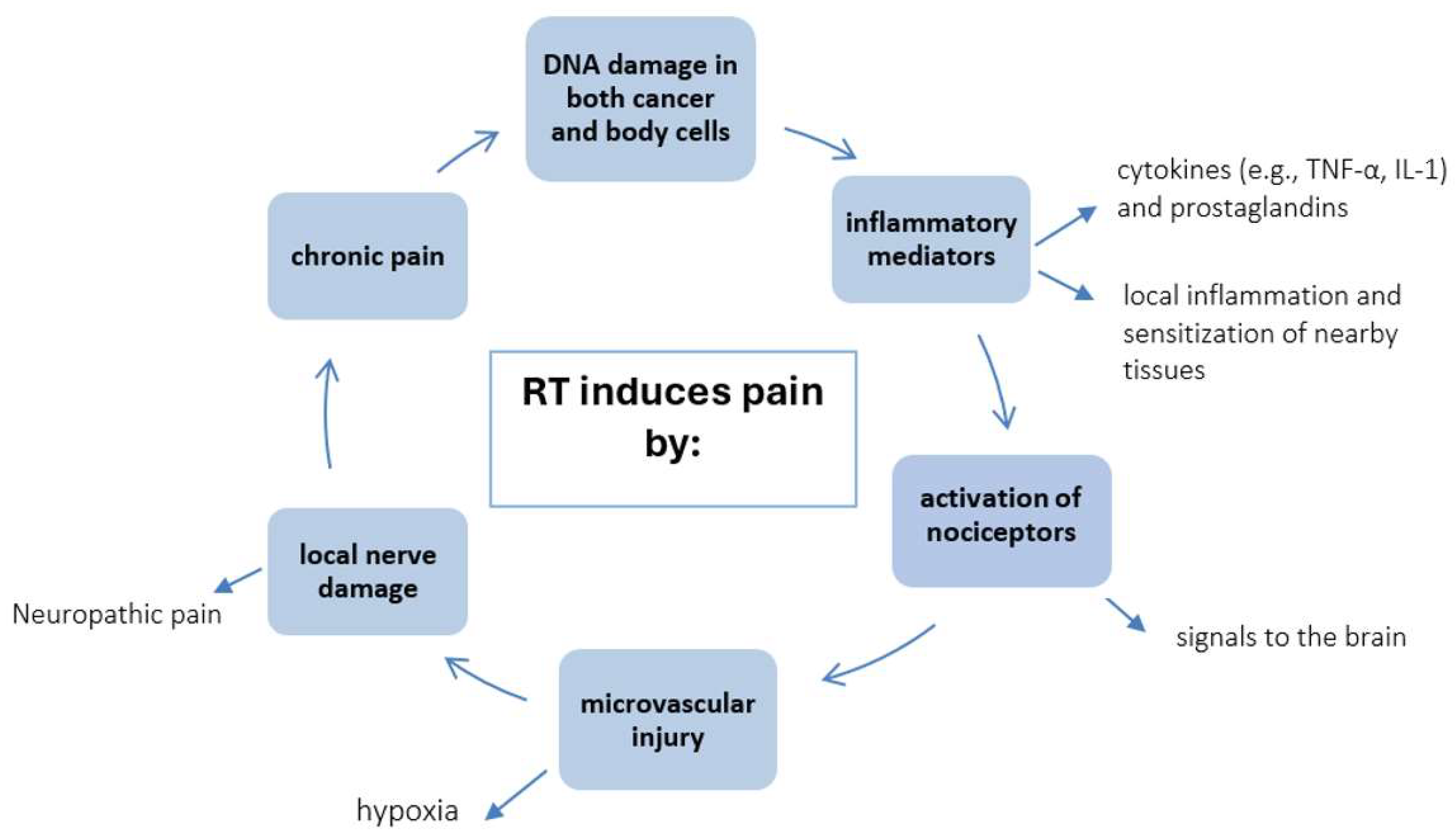

5. The Other Side of the Coin in the Effect of Radiotherapy

5.1. Pain as a Consequence of Radiotherapy

5.2. Painful Complications After RT

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarawal J.P., Swangsilpa T., van der Linden Y., Rades D., Jeremic B., Hoskin P.J. The Role of External Beam Radiotherapy in the Management of Bone Metastases. Clin. Oncol. 2006,8,747–760. [CrossRef]

- Lin J, Hsieh RK, Chen JS, Lee KD, Rau KM, Shao YY, Sung YC, Yeh SP, Chang CS, Liu TC, Wu MF, Lee MY, Yu MS, Yen CJ, Lai PY, Hwang WL, Chiou TJ. Satisfaction with pain management and impact of pain on quality of life in cancer patients. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2020,16,2:e91-e98. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierko E, Hempel D, Zuzda K, Wojtukiewicz MZ. Personalized Radiation Therapy in Cancer Pain Management. Cancers (Basel). 2019,11,3,:390. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chow E., Zeng L., Salvo N., Dennis K., Tsao M., Lutz S. Update on the Systematic Review of Palliative Radiotherapy Trials for Bone Metastases. Clin. Oncol. 2012,24,112–124. [CrossRef]

- Baskar R, Lee KA, Yeo R, Yeoh KW. Cancer and radiation therapy: current advances and future directions. Int J Med Sci. 2012,9,3,193-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jooya A, Talla K, Wei R, Huang F, Dennis K, Gaudet M. Systematic review of brachytherapy for symptom palliation. Brachytherapy. 2022, 6,912-932. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra-Bolaños Á, Jiménez-Gil M, Federico M, Domínguez-Díaz Y, Valencia L, Rodríguez-Pérez A. Pain in High-Dose-Rate Brachytherapy for Cervical Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Pers Med. 2023, 13, 8,1187. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mao G, Theodore N. Spinal brachytherapy. Neuro Oncol. 2022, 24,S62-S68. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bossi A, Foulon S, Maldonado X, Sargos P, MacDermott R, Kelly P, Fléchon A, Tombal B, Supiot S, Berthold D, Ronchin P, Kacso G, Salem N, Calabro F, Berdah JF, Hasbini A, Silva M, Boustani J, Ribault H, Fizazi K; PEACE-1 investigators. Efficacy and safety of prostate radiotherapy in de novo metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (PEACE-1): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study with a 2 × 2 factorial design. Lancet. 2024, 404, 10467,:2065-2076. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzysztofiak T, Kamińska-Winciorek G, Pilśniak A, Wojcieszek P. High dose rate brachytherapy in nonmelanoma skin cancer-Systematic review. Dermatol Ther. 2022, 9,e15675. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao Q., Wang H., Meng N., Jiang Y., Jiang P., Gao Y., Tian S., Liu C., Yang R., Wang J., et al. CT- guidance interstitial 125Iodine seed brachytherapy as a salvage therapy for recurrent spinal primary tumors. Radiat. Oncol. 2014, 9,301. [CrossRef]

- Qian J., Bao Z., Zou J., Yang H. Effect of pedicle fixation combined with 125I seed implantation for metastatic thoracolumbar tumors. J. Pain Res. 2016 ,9,271–278.

- Nag S, Hu KS. Intraoperative high-dose-rate brachytherapy. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003, 4,1079-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He J, Mai Q, Yang F, Zhuang W, Gou Q, Zhou Z, Xu R, Chen X, Mo Z. Feasibility and Clinical Value of CT-Guided 125I Brachytherapy for Pain Palliation in Patients With Breast Cancer and Bone Metastases After External Beam Radiotherapy Failure. Front Oncol. 2021, 11,627158. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zuckerman S.L., Lim J., Yamada Y., Bilsky M.H., Laufer I. Brachytherapy in Spinal Tumors: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurg. 2018, 118, e235–e244. [CrossRef]

- Parker C., Heinrich D., O’Sullivan J.M., Fossa S., Chodacki A., Demkow T., Cross A., Bolstad B., Garcia- Vargas J., Sartor O. Sartor Overall survival benefit of radium-223 chloride (Alpharadin) in the treatment of patients with symptomatic bone metastases in Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer (CRPC): A phase III randomized trial (ALSYMPCA) Eur. J. Cancer. 2011, 47,3. [CrossRef]

- Choi J.Y. Treatment of Bone Metastasis with Bone-Targeting Radiopharmaceuticals. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2018,52,200–207. [CrossRef]

- Ma Y.-B., Yan W.-L., Dai J.-C., Xu F., Yuan Q., Shi H.-H. Strontium-89: A desirable therapeutic for bone metastases of prostate cancer. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2008,14,819–822.

- Ogawa K., Washiyama K. Bone Target Radiotracers for Palliative Therapy of Bone Metastases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19,3290–3300. [CrossRef]

- Finlay I.G., Mason M.D., Shelley M. Radioisotopes for the palliation of metastatic bone cancer: A systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2005, 6,392–400. [CrossRef]

- Fettich J., Padhy A., Nair N., Morales R., Tanumihardja M., Riccabonna G., Nair G. Comparative clinical efficacy and safety of Phosphorus-32 and Strontium-89 in the palliative treatment of metastatic bone pain: Results of an IAEA Coordinated Research Project. World J. Nucl. Med. 2003 ,34,226–231.

- Parker C., Nilsson S., Heinrich D., Helle S.I., O’Sullivan J.M., Fosså S.D., Chodacki A., Wiechno P.,Logue J., Seke M., et al. Alpha Emitter Radium-223 and Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl.J. Med. 2013, 369,213–223. [CrossRef]

- Dolezal J., Vizda J., Odrazka K. Prospective evaluation of samarium-153-EDTMP radionuclide treatment for bone metastases in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Urol. Int. 2007, 78,50–57. [CrossRef]

- Dafermou A., Colamussi P., Giganti M., Cittanti C., Bestagno M., Piffanelli A. A multicentre observational study of radionuclide therapy in patients with painful bone metastases of prostate cancer. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2001, 28,788–798. [CrossRef]

- Baczyk M., Milecki P., Baczyk E., Sowiński J. The effectivness of strontium 89 in palliative therapy of painful prostate cancer bone metastases. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2003, 5,364–368.

- Sciuto R., Festa A., Pasqualoni R., Semprebene A., Rea S., Bergomi S., Maini C.L. Metastatic bone pain palliation with 89-Sr and 186-Re-HEDP in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2001, 66,101–109. [CrossRef]

- Zenda S., Nakagami Y., Toshima M., Arahira S., Kawashima M., Matsumoto Y., Kinoshita H., Satake M., Akimoto T. Strontium-89 (Sr-89) chloride in the treatment of various cancer patients with multiple bone metastases. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 19,739–743. [CrossRef]

- Laing A.H., Ackery D.M., Bayly R.J., Buchanan R.B., Lewington V.J., McEwan A.J.B., Macleod P.M., Zivanovic M.A. Strontium-89 chloride for pain palliation in prostatic skeletal malignancy. Br. J. Radiol. 1991, 64,817–822. [CrossRef]

- Sartor O., Reid R.H., Hoskin P.J., Quick D.P., Ell P.J., Coleman R.E., Kotler J.A., Freeman L.M., Olivier P. Samarium-153-lexidronam complex for treatment of painful bone metastases in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Urology 2004, 63, 940–945. [CrossRef]

- Serafini A.N., Houston S.J., Resche I., Quick D.P., Grund F.M., Ell P.J., Bertrand A., Ahmann F.R., Orihuela E., Reid R.H., et al. Palliation of pain associated with metastatic bone cancer using samarium- 153 lexidronam: A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 1574–1581. [CrossRef]

- Parker C., Heinrich D., O’Sullivan J.M., Fossa S., Chodacki A., Demkow T., Cross A., Bolstad B., Garcia- Vargas J., Sartor O. Sartor Overall survival benefit of radium-223 chloride (Alpharadin) in the treatment of patients with symptomatic bone metastases in Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer (CRPC): A phase III randomized trial (ALSYMPCA) Eur. J. Cancer. 2011, 47,3. [CrossRef]

- Parker C., Nilsson S., Heinrich D., Helle S.I., O’Sullivan J.M., Fosså S.D., Chodacki A., Wiechno P.,Logue J., Seke M., et al. Alpha Emitter Radium-223 and Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl.J. Med. 2013, 369,213–223. [CrossRef]

- Han S.H., de Klerk J.M.H., Tan S., van het Schip A.D., Derksen B.H., van Dijk A., Kruitwagen C.L.J.J., Blijham G.H., van Rijk P.P., Zonnenberg B.A. The PLACORHEN study: A double-blind, placebo- controlled, randomized radionuclide study with (186) Re-etidronate in hormone-resistant prostate cancer patients with painful bone metastases. Placebo Controlled Rhenium Study. J. Nucl. Med. 2002, 43, 1150–1156.

- Han S.H., Zonneberg B.A., de Klerk J.M., Quirijnen J.M., van het Schip A.D., van Dijk A., Blijham G.H., van Rijk P.P. 186Re-etidronate in breast cancer patients with metastatic bone pain. J. Nucl. Med.1999, 40, 639–642.

- Palmedo H., Guhlke S., Bender H., Sartor J., Schoeneich G., Risse J., Grünwald F., Knapp F.F., Biersack H.J. Dose escalation study with rhenium-188 hydroxyethylidene diphosphonate in prostate cancer patients with osseous metastases. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2000, 27,123–130. [CrossRef]

- Liepe K., Hliscs R., Kropp J., Gruning T., Runge R., Koch R., Knapp F.F.J., Franke W.G. Rhenium-188- HEDP in the palliative treatment of bone metastases. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2000, 15, 261–265. [CrossRef]

- Goblirsch, M.J.; Zwolak, P.P.; Clohisy, D.R. Biology of Bone Cancer Pain. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 6231s–6235s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goblirsch, M.; Mathews, W.; Lynch, C.; Alaei, P.; Gerbi, B.J.; Mantyh, P.W.; Clohisy, D.R. Radiation treatment decreases bone cancer pain, osteolysis and tumor size. Radiat. Res. 2004, 161, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLeod K, Laird BJA, Carragher NO, Hoskin P, Fallon MT, Sande TA. Predicting Response to Radiotherapy in Cancer-Induced Bone Pain: Cytokines as a Potential Biomarker? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2020 ,32,10 ,e203-e208. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, R.; Shan, H. Study on the Correlation between Pain and Cytokine Expression in the Peripheral Blood of Patients with Bone Metastasis of Malignant Cancer Treated Using External Radiation Therapy. Pain Res Manag. 2022, 2022,1119014. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cun-Jin S, Jian-Hao X, Xu L, Feng-Lun Z, Jie P, Ai-Ming S, Duan-Min H, Yun-Li Y, Tong L, Yu-Song Z. X- ray induces mechanical and heat allodynia in mouse via TRPA1 and TRPV1 activation. Mol Pain. 2019, 1744806919849201. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Habberstad R, Aass N, Mollnes TE, Damås JK, Brunelli C, Rossi R, Garcia-Alonso E, Kaasa S, Klepstad P. Inflammatory Markers and Radiotherapy Response in Patients With Painful Bone Metastases. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022, 64,4,330-339. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertho A, Iturri L, Prezado Y. Radiation-induced immune response in novel radiotherapy approaches FLASH and spatially fractionated radiotherapies. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2023 ,376:37-68. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutt S, Ahmed MM, Loo BW Jr, Strober S. Novel Radiation Therapy Paradigms and Immunomodulation: Heresies and Hope. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2020, 30,2,194-200. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Song XJ, Wang ZB, Gan Q, Walters ET. cAMP and cGMP contribute to sensory neuron hyperexcitability and hyperalgesia in rats with dorsal root ganglia compression. J Neurophysiol. 2006, 95,1,479-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng JH, Walters ET, Song XJ. Dissociation of dorsal root ganglion neurons induces hyperexcitability that is maintained by increased responsiveness to cAMP and cGMP. J Neurophysiol. 2007, 97,1,15-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu S, Liu YP, Song WB, Song XJ. EphrinB-EphB receptor signaling contributes to bone cancer pain via Toll-like receptor and proinflammatory cytokines in rat spinal cord. Pain 2013, 154,12,2823- 2835. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu G, Dong Y, He X, Zhao P, Yang A, Zhou R, Ma J, Xie Z, Song XJ. Radiotherapy Suppresses Bone Cancer Pain through Inhibiting Activation of cAMP Signaling in Rat Dorsal Root Ganglion and Spinal Cord. Mediators Inflamm. 2016, 5093095. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koswig S, Budach V. Remineralisation und Schmerzlinderung von Knochenmetastasen nach unterschiedlich fraktionierter Strahlentherapie (10 mal 3 Gy vs. 1 mal 8 Gy). Eine prospektive Studie [Remineralization and pain relief in bone metastases after after different radiotherapy fractions (10 times 3 Gy vs. 1 time 8 Gy). A prospective study]. Strahlenther Onkol. 1999, 175,10,500-8. German. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprave, T.; Verma, V.; Förster, R.; Schlampp, I.; Hees, K.; Bruckner, T.; Bostel, T.; El Shafie, R.A.; Welzel, T.; Nicolay, N.H.; et al. Bone density and pain response following intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for vertebral metastases—Secondary results of a randomized trial. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 13, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei R.L., Mattes M.D., Yu J., Thrasher A., Shu H.-K., Paganetti H., De Los Santos J., Koontz B., Abraham C., Balboni T. Attitudes of radiation oncologists toward palliative and supportive care in the United States: Report on national membership survey by the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2017,7,113–119. [CrossRef]

- Murakami S, Kitani A, Kubota T, Uezono Y. Increased pain after palliative radiotherapy: not only due to cancer progression. Ann Palliat Med. 2024, 13, 18-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brozović G, Lesar N, Janev D, Bošnjak T, Muhaxhiri B. CANCER PAIN AND THERAPY. Acta Clin Croat. 2022, 61,103-108. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ng S.P., Koay E.J. Current and emerging radiotherapy strategies for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: stereotactic, intensity modulated and particle radiotherapy. Ann. Pancreat. Cancer. 2018,1,22. [CrossRef]

- Ryan J.F., Rosati L.M., Groot V.P., Le D.T., Zheng L., Laheru D.A., Shin E.J., Jackson J., Moore J., Narang A.K., et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for palliative management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in elderly and medically inoperable patients. Oncotarget. 2018, 9,16427–16436. [CrossRef]

- Arscott WT, Emmett J, Ghiam AF, Jones JA. Palliative Radiotherapy: Inpatients, Outpatients, and the Changing Role of Supportive Care in Radiation Oncology. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2020;34(1):253-277.

- Fairchild A., Harris K., Barnes E., Wong R., Lutz S., Bezjak A., Cheung P., Chow E. Palliative thoracic radiotherapy for lung cancer: A systematic review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4001–4011. [CrossRef]

- Lutz ST. Palliative radiotherapy: history, recent advances, and future directions. Ann Palliat Med. 2019, 8, 3,240-245. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu X, Zhang B, Zhang S, Xia X, Sun S, Wu D. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for superior vena cava syndrome. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2011,27,4,756-757. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Williams GR, Manjunath SH, Butala AA, Jones JA. Palliative Radiotherapy for Advanced Cancers: Indications and Outcomes. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2021, 3,3, 563-580. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui JK, Perlow HK, Upadhyay R, McCalla A, Raval RR, Thomas EM, Blakaj DM, Beyer SJ, Palmer JD. Advances in Radiotherapy for Brain Metastases. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2023, 323,56,9-586. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoni D, Mesny E, El Kabbaj O, Josset S, Noël G, Biau J, Feuvret L, Latorzeff I. Role of radiotherapy in the management of brain oligometastases. Cancer Radiother. 2024, 28,1,103-110. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho S, Chu MK. Headache in Brain Tumors. Neurol Clin. 2024, 42,2,487-496. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuneo A, Murinova N. Headache Management in Individuals with Brain Tumor. Semin Neurol. 2024, 44,1,74-89. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondi V, Bauman G, Bradfield L, Burri SH, Cabrera AR, Cunningham DA, Eaton BR, Hattangadi-Gluth JA, Kim MM, Kotecha R, Kraemer L, Li J, Nagpal S, Rusthoven CG, Suh JH, Tomé WA, Wang TJC, Zimmer AS, Ziu M, Brown PD. Radiation Therapy for Brain Metastases: An ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2022, 12,4,265-282. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagliardi F, De Domenico P, Snider S, Nizzola MG, Mortini P. Efficacy of neoadjuvant stereotactic radiotherapy in brain metastases from solid cancer: a systematic review of literature and meta- analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 2023, 46,1,130. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodensohn R, Kaempfel AL, Boulesteix AL, Orzelek AM, Corradini S, Fleischmann DF, Forbrig R, Garny S, Hadi I, Hofmaier J, Minniti G, Mansmann U, Pazos Escudero M, Thon N, Belka C, Niyazi M. Stereotactic radiosurgery versus whole-brain radiotherapy in patients with 4-10 brain metastases: A nonrandomized controlled trial. Radiother Oncol. 2023, 186,109744. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono T, Nemoto K. Re-Whole Brain Radiotherapy May Be One of the Treatment Choices for Symptomatic Brain Metastases Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 4,21,5293. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coleman RE, Croucher PI, Padhani AR, Clézardin P, Chow E, Fallon M, Guise T, Colangeli S, Capanna R, Costa L. Bone metastases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020, 6,1,83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcangeli G., Pinnarò P., Rambone R., Giannarelli D., Benassi M. A phase III randomized study on the sequencing of radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the conservative management of early-stage breast cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006, 64,61–167. [CrossRef]

- Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Trivellas A, Eschweiler J, Tingart M, Driessen A. Bone metastases: a comprehensive review of the literature. Mol Biol Rep. 2020, 47,8,6337-6345. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harstell W.F., Santosh Y. Palliation of bone metastases. In: Halperin E., Perez C., Brady L., editors. Principles and Practice of Radiat. Oncol. 2013, 1, 1778–1791.

- Cook GJR, Goh V. Molecular Imaging of Bone Metastases and Their Response to Therapy. J Nucl Med. 2020, 61,6,799-806. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakhki VR, Anvari K, Sadeghi R, Mahmoudian AS, Torabian-Kakhki M. Pattern and distribution of bone metastases in common malignant tumors. Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur. 2013, 16,2,66-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clézardin P, Coleman R, Puppo M, Ottewell P, Bonnelye E, Paycha F, Confavreux CB, Holen I. Bone metastasis: mechanisms, therapies, and biomarkers. Physiol Rev. 2021, 101,3,797-855. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Käkönen SM, Mundy GR. Mechanisms of osteolytic bone metastases in breast carcinoma. Cancer 2003, 1,97,834-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guise TA, Mohammad KS, Clines G, Stebbins EG, Wong DH, Higgins LS, Vessella R, Corey E, Padalecki S, Suva L, Chirgwin JM. Basic mechanisms responsible for osteolytic and osteoblastic bone metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Oct 15;12(20 Pt 2):6213s-6216s. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challapalli A, Aziz S, Khoo V, Kumar A, Olson R, Ashford RU, Gabbar OA, Rai B, Bahl A. Spine and Non- spine Bone Metastases - Current Controversies and Future Direction. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2020, 32,11,728-744. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouhassira, D.; Luporsi, E.; Krakowski, I. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pain with or without neuropathic characteristics in patients with cancer. Pain 2017, 158, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinboonyahgoon, N.; Luansritisakul, C. Neuropathic pain feature in cancer-induced bone pain: Does it matter? A prospective observational study. Korean J. Pain 2023, 36, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos DE. Radiotherapy for neuropathic pain due to bone metastases. Ann Palliat Med. 2015, 4,220-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouveia AG, Chan DCW, Hoskin PJ, Marta GN, Trippa F, Maranzano E, Chow E, Silva MF. Advances in radiotherapy in bone metastases in the context of new target therapies and ablative alternatives: A critical review. Radiother Oncol. 2021, 163,55-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestdagh F, Steyaert A, Lavand'homme P. Cancer Pain Management: A Narrative Review of Current Concepts, Strategies, and Techniques. Curr Oncol. 2023, 30,7,6838-6858. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Takei D, Tagami K. Management of cancer pain due to bone metastasis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2023 ,41,3,327-336. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz S., Berk L., Chang E., Chow E., Hahn C., Hoskin P., Howell D., Konski A., Kachnic L., Lo S., et al. Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: An ASTRO evidence-based guideline. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011, 79,965–976. [CrossRef]

- Tseng YD. Radiation Therapy for Painful Bone Metastases: Fractionation, Recalcification, and Symptom Control. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2023, 2,139-147. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam T.C., Tseng Y. Defining the radiation oncologist’s role in palliative care and radiotherapy. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2018, 7,1002. [CrossRef]

- Sierko E, Hempel D, Zuzda K, Wojtukiewicz MZ. Personalized Radiation Therapy in Cancer Pain Management. Cancers (Basel). 2019, 11,3,390. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koswig S., Budach V. Remineralization and pain relief in bone metastases after after different radiotherapy fractions (10 times 3 Gy vs. 1 time 8 Gy). A prospective study. Strahlenther. Onkol. 1999, 175,500–508. [CrossRef]

- Foro Arnalot P., Fontanals A.V., Galcerán J.C., Lynd F., Latiesas X.S., de Dios N.R., Castillejo A.R., Bassols M.L., Galán J.L., Conejo I.M., et al. Randomized clinical trial with two palliative radiotherapy regimens in painful bone metastases: 30 Gy in 10 fractions compared with 8 Gy in single fraction. Radiother. Oncol. 2008, 89,150–155. [CrossRef]

- Nongkynrih A., Dhull A.K., Kaushal V., Atri R., Dhankhar R., Kamboj K. Comparison of Single Versus Multifraction Radiotherapy in Palliation of Painful Bone Metastases. World J. Oncol. 2018, 9,91–95. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi SP, Faccenda V, Pacifico P, Parma G, Saufi S, Ferrario F, Belmonte M, Sala L, De Ponti E, Panizza D, Arcangeli S. Short-term pain control after palliative radiotherapy for uncomplicated bone metastases: a prospective cohort study. Med Oncol. 2023, 41,1,13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachnic L., Berk L. Palliative Single-Fraction Radiation Therapy: How Much More Evidence Is Needed? JNCI. 2005, 97,786–788. [CrossRef]

- Chow E., Zeng L., Salvo N., Dennis K., Tsao M., Lutz S. Update on the Systematic Review of Palliative Radiotherapy Trials for Bone Metastases. Clin. Oncol. 2012;24:112–124. [CrossRef]

- Chow E., van der Linden Y.M., Roos D., Hartsell W.F., Hoskin P., Wu J.S.Y., Brundage M.D., Nabid A., Tissing-Tan C.J.A., Oei B., et al. Single versus multiple fractions of repeat radiation for painful bone metastases: A randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15,164–171. [CrossRef]

- Roos D.E., Turner S.L., O’Brien P.C., Smith J.G., Spry N.A., Burmeister B.H., Hoskin P.J., Ball D.L. Randomized trial of 8 Gy in 1 versus 20 Gy in 5 fractions of radiotherapy for neuropathic pain due to bone metastases (Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group, TROG 96.05) Radiother. Oncol. 2005,75,54–63. [CrossRef]

- Saito T., Tomitaka E., Toya R., Matsuyama T., Ninomura S., Watakabe T., Oya N. A neuropathic pain component as a predictor of improvement in pain interference after radiotherapy for painful tumors: A secondary analysis of a prospective observational study. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 12,34–39. [CrossRef]

- Saito AI, Hirai T, Inoue T, Hojo N, Kawai S, Kato Y, Ito K, Kato M, Ozawa Y, Shinjo H, Toda K, Yoshimura RI. Time to Pain Relapse After Palliative Radiotherapy for Bone Metastasis: A Prospective Multi-institutional Study. Anticancer Res. 2023, 43,2,865-873. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz S., Balboni T., Jones J., Lo S., Petit J., Rich S.E., Wong R., Hahn C. Palliative radiation therapy for bone metastases: Update of an ASTRO Evidence-Based Guideline. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 7,4–12. [CrossRef]

- van der Velden J, Willmann J, Spałek M, Oldenburger E, Brown S, Kazmierska J, Andratschke N, Menten J, van der Linden Y, Hoskin P. ESTRO ACROP guidelines for external beam radiotherapy of patients with uncomplicated bone metastases. Radiother Oncol. 2022, 173,197-206. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldenburger E, Brown S, Willmann J, van der Velden JM, Spałek M, van der Linden YM, Kazmierska J, Menten J, Andratschke N, Hoskin P. ESTRO ACROP guidelines for external beam radiotherapy of patients with complicated bone metastases. Radiother Oncol. 2022, 173,240-253. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenland E, Leer JW, van Houwelingen H, Post WJ, van den Hout WB, Kievit J, de Haes H, Martijn H, Oei B, Vonk E, van der Steen-Banasik E, Wiggenraad RG, Hoogenhout J, Wárlám-Rodenhuis C, van Tienhoven G, Wanders R, Pomp J, van Reijn M, van Mierlo I, Rutten E. The effect of a single fraction compared to multiple fractions on painful bone metastases: a global analysis of the Dutch Bone Metastasis Study. Radiother Oncol. 1999, 2,101-9. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(99)00110-3. Erratum in: Radiother Oncol 1999 Nov;53(2):167. Leer, J [corrected to Leer, JW]; van Mierlo ,T [corrected to van Mierlo, I]. PMID: 10577695.

- Koswig S, Buchali A, Böhmer D, Schlenger L, Budach V. Palliative Strahlentherapie von Knochenmetastasen. Eine retrospective Analyse von 176 Patienten [Palliative radiotherapy of bone metastases. A retrospective analysis of 176 patients]. Strahlenther Onkol. 1999, 175,10,509-14. German. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos DE, Turner SL, O'Brien PC, Smith JG, Spry NA, Burmeister BH, Hoskin PJ, Ball DL; Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group, TROG 96.05. Randomized trial of 8 Gy in 1 versus 20 Gy in 5 fractions of radiotherapy for neuropathic pain due to bone metastases (Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group, TROG 96.05). Radiother Oncol. 2005, 75,1,54-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Bruner DW, Scarantino CW, Ivker RA, Roach M 3rd, Suh JH, Demas WF, Movsas B, Petersen IA, Konski AA, Cleeland CS, Janjan NA, DeSilvio M. Randomized trial of short- versus long-course radiotherapy for palliation of painful bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005, 97,11,798-804. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foro Arnalot P, Fontanals AV, Galcerán JC, Lynd F, Latiesas XS, de Dios NR, Castillejo AR, Bassols ML, Galán JL, Conejo IM, López MA. Randomized clinical trial with two palliative radiotherapy regimens in painful bone metastases: 30 Gy in 10 fractions compared with 8 Gy in single fraction. Radiother Oncol. 2008, 89,2,150-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nongkynrih A, Dhull AK, Kaushal V, Atri R, Dhankhar R, Kamboj K. Comparison of Single Versus Multifraction Radiotherapy in Palliation of Painful Bone Metastases. World J Oncol. 2018, 9,3,91-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nguyen QN, Chun SG, Chow E, Komaki R, Liao Z, Zacharia R, Szeto BK, Welsh JW, Hahn SM, Fuller CD, Moon BS, Bird JE, Satcher R, Lin PP, Jeter M, O'Reilly MS, Lewis VO. Single-Fraction Stereotactic vs Conventional Multifraction Radiotherapy for Pain Relief in Patients With Predominantly Nonspine Bone Metastases: A Randomized Phase 2 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5,6,872-878. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0192. Erratum in: JAMA Oncol. 2021 Oct 1;7(10):1581. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.3081. PMID: 31021390; PMCID: PMC6487911.

- Nguyen EK, Ruschin M, Zhang B, Soliman H, Myrehaug S, Detsky J, Chen H, Sahgal A, Tseng CL. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for spine metastases: a review of 24 Gy in 2 daily fractions. J Neurooncol. 2023, 163,1, 15-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilski M, Konat-Bąska K, Mastroleo F, Hoskin P, Alicja Jereczek-Fossa B, Marvaso G, Korga M, Klas J, Zych K, Bijak P, Kukiełka A, Fijuth J, Kuncman Ł. Half body irradiation (HBI) for bone metastases in the modern radiotherapy technique era - A systematic review. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2024, 49,100845. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Delinikolas P., Patatoukas G., Kouloulias V., Dilvoi M., Plousi A., Efstathopoulos E., Platoni K. A novel Hemi-Body Irradiation technique using electron beams (HBIe−) Phys. Medica. 2018, 46,16–24. [CrossRef]

- Pal S., Dutta S., Adhikary S., Bhattacharya B., Ghosh B., Patra N. Hemi body irradiation: An economical way of palliation of pain in bone metastasis in advanced cancer. South Asian J. Cancer. 2014, 3,28. [CrossRef]

- Ryu S, Deshmukh S, Timmerman RD, Movsas B, Gerszten P, Yin FF, Dicker A, Abraham CD, Zhong J, Shiao SL, Tuli R, Desai A, Mell LK, Iyengar P, Hitchcock YJ, Allen AM, Burton S, Brown D, Sharp HJ, Dunlap NE, Siddiqui MS, Chen TH, Pugh SL, Kachnic LA. Stereotactic Radiosurgery vs Conventional Radiotherapy for Localized Vertebral Metastases of the Spine: Phase 3 Results of NRG Oncology/RTOG 0631 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9,6,800-807. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nguyen EK, Ruschin M, Zhang B, Soliman H, Myrehaug S, Detsky J, Chen H, Sahgal A, Tseng CL. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for spine metastases: a review of 24 Gy in 2 daily fractions. J Neurooncol. 2023, 163,1,15-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma D.A., Salama J.K., Lo S.S., Senan S., Treasure T., Govindan R., Weichselbaum R. The oligometastatic state-separating truth from wishful thinking. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 11,549–557. [CrossRef]

- Osborn V.W., Lee A., Yamada Y. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Spinal Malignancies. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 17. [CrossRef]

- Bindels BJJ, Mercier C, Gal R, Verlaan JJ, Verhoeff JJC, Dirix P, Ost P, Kasperts N, van der Linden YM, Verkooijen HM, van der Velden JM. Stereotactic Body and Conventional Radiotherapy for Painful Bone Metastases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024, 7,2,e2355409. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shahid Iqbal M, Kelly C, Kovarik J, Goranov B, Shaikh G, Morgan D, Dobrowsky W, Paleri V. Palliative radiotherapy for locally advanced non-metastatic head and neck cancer: A systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 2018, 126,3,558-567. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingeta GT, Worku YT, Awol M, Woldetsadik ES, Assefa M, Chama TZ, Feyisa JD, Bedada HF, Adem MI, Mengesha T, Wong R. Outcome of Hypofractionated Palliative Radiotherapy Regimens for Patients With Advanced Head and Neck Cancer in Tikur Anbessa Hospital, Ethiopia: A Prospective Cohort Study. JCO Glob Oncol. 2024, 10,e2300253. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schaller AKCS, Peterson A, Bäckryd E. Pain management in patients undergoing radiation therapy for head and neck cancer - a descriptive study. Scand J Pain. 2020, 21,2,256-265. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

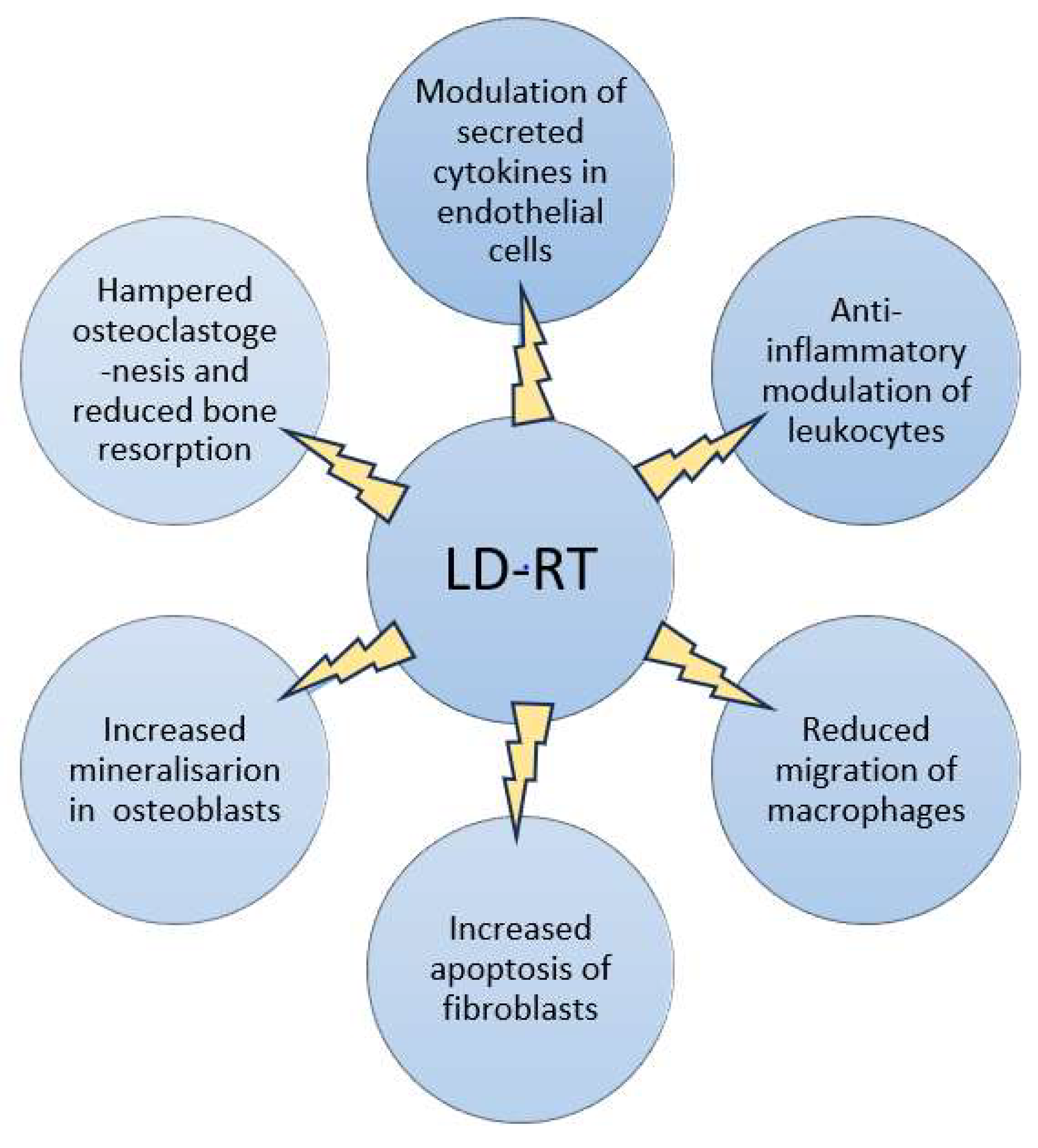

- Trott KR, Kamprad F. Radiobiological mechanisms of anti-inflammatory radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 1999, 51,3,197-203. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas M, Sabater S, Hernández V, Rovirosa A, Lara PC, Biete A, Panés J. Anti-inflammatory effects of low-dose radiotherapy. Indications, dose, and radiobiological mechanisms involved. Strahlenther Onkol. 2012, 188,11,975-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rühle A, Tkotsch E, Mravlag R, Haehl E, Spohn SKB, Zamboglou C, Huber PE, Debus J, Grosu AL, Sprave T, Nicolay NH. Low-dose radiotherapy for painful osteoarthritis of the elderly: A multicenter analysis of 970 patients with 1185 treated sites. Strahlenther Onkol. 2021, 197,10, 895-902. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdelmaqsoud A, Vorotniak N, Strauß D, Hentschel B. The analgesic effect of low-dose radiotherapy in treating benign musculoskeletal painful disorders using different energies: A retrospective cohort study. JRP 2023, 22,e78. [CrossRef]

- Weissmann T, Rückert M, Zhou JG, Seeling M, Lettmaier S, Donaubauer AJ, Nimmerjahn F, Ott OJ, Hecht M, Putz F, Fietkau R, Frey B, Gaipl US, Deloch L. Low-Dose Radiotherapy Leads to a Systemic Anti-Inflammatory Shift in the Pre-Clinical K/BxN Serum Transfer Model and Reduces Osteoarthritic Pain in Patients. Front Immunol. 2022, 12,777792. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Javadinia, S A, Nazeminezhad, N, Ghahramani-Asl, R et al. Low-dose radiation therapy for osteoarthritis and enthesopathies: a review of current data. Int J Radiat Biol 2021, 97,10,1352–1367. [CrossRef]

- Loblaw DA, Wu JS, Kirkbride P, et al. Pain flare in patients with bone metastases after palliative radiotherapy--a nested randomized control trial. Support. Care Cancer 2007,15,451-5.

- Chow E, Ling A, Davis L, et al. Pain flare following external beam radiotherapy and meaningful change in pain scores in the treatment of bone metastases. Radiother Oncol 2005, 75:64-9. [CrossRef]

- Hird A, Chow E, Zhang L, et al. Determining the incidence of pain flare following palliative radiotherapy for symptomatic bone metastases: results from three canadian cancer centers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009, 75,193-7.

- Loblaw, D.A.; Wu, J.S.; Kirkbride, P.; Panzarella, T.; Smith, K.; Aslanidis, J.; Warde, P. Pain flare in patients with bone metastases after palliative radiotherapy—A nested randomized control trial. Support. Care Cancer 2007, 15, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow E, Meyer RM, Ding K, et al. Dexamethasone in the prophylaxis of radiation-induced pain flare after palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015, 16,1463-72.

- van der Velden JM, Peters M, Verlaan JJ, Versteeg AL, Zhang L, Tsao M, Danjoux C, Barnes E, van Vulpen M, Chow E, Verkooijen HM. Development and Internal Validation of a Clinical Risk Score to Predict Pain Response After Palliative Radiation Therapy in Patients With Bone Metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017, 99,4,859-866. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.07.029. Epub 2017 Jul 31.Erratum in: Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019 Aug 1;104(5):1186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.05.016. PMID: 29063851.

- Fabregat C, Almendros S, Navarro-Martin A, Gonzalez J. Pain Flare-Effect Prophylaxis With Corticosteroids on Bone Radiotherapy Treatment: A Systematic Review. Pain Pract. 2020, 20,1,101-109. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habberstad R, Frøseth TCS, Aass N, Bjerkeset E, Abramova T, Garcia-Alonso E, Caputo M, Rossi R, Boland JW, Brunelli C, Lund JÅ, Kaasa S, Klepstad P. Clinical Predictors for Analgesic Response to Radiotherapy in Patients with Painful Bone Metastases. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021, 62,4,681- 690. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donati CM, Maggiore CM, Maltoni M, Rossi R, Nardi E, Zamagni A, Siepe G, Mammini F, Cellini F, Di Rito A, Portaluri M, De Tommaso C, Santacaterina A, Tamburella C, Di Franco R, Parisi S, Cossa S, Fusco V, Bianculli A, Ziccarelli P, Ziccarelli L, Genovesi D, Caravatta L, Deodato F, Macchia G, Fiorica F, Napoli G, Buwenge M, Morganti AG. Adequacy of Pain Management in Patients Referred for Radiation Therapy: A Subanalysis of the Multicenter ARISE-1 Study. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 16,1,109. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Delanian S, Lefaix JL, Pradat PF. Radiation-induced neuropathy in cancer survivors. Radiother Oncol. 2012;105(3):273–282. [CrossRef]

- Fathers E, Thrush D, Huson SM, Norman A. Radiation-induced brachial plexopathy in women treated for carcinoma of the breast. Clin Rehabil. 2002, 16,2,160–165. [CrossRef]

- Andreyev HJ, Wotherspoon A, Denham JW, Hauer-Jensen M. Defining pelvic-radiation disease for the survivorship era. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11,4,310–312. [CrossRef]

- Elahi F, Callahan D, Greenlee J, Dann TL. Pudendal entrapment neuropathy: a rare complication of pelvic radiation therapy. Pain Physician. 2013, 16,6,E793–E797.

- WHO Guidelines for the Pharmacological and Radiotherapeutic Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Adolescents. Geneva: WHO 2018. [PubMed]

- Doo AR, Shin YS, Yoo S, Park JK. Radiation-induced neuropathic pain successfully treated with systemic lidocaine administration. J Pain Res. 2018, 11,545-548. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moisset X. Neuropathic pain: Evidence based recommendations. Presse Med. 2024, 53,2,104232. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai JH, Liu IT, Su PF, Huang YT, Chiu GL, Chen YY, Lai WS, Lin PC. Lidocaine transdermal patches reduced pain intensity in neuropathic cancer patients already receiving opioid treatment. BMC Palliat Care. 2023, 22,1,4. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stubblefield MD: Cancer Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed. New York, Demos Medical 2018.

- Pradat PF, Bouche P, Delanian S. Sciatic nerve moneuropathy: an unusual late effect of radiotherapy. Muscle Nerve. 2009, 40,5,872-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu Y, Tsai W, Sokolof J. Sciatic Neuropathy After Radiation Treatment. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2021, 100,12,e198-e199. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr CM, Benson JC, DeLone DR, Diehn FE, Kim DK, Ma D, Nagelschneider AA, Madhavan AA, Johnson DR. Manifestations of radiation toxicity in the head, neck, and spine: An image-based review. Neuroradiol J. 2022, 4,427-436. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chopra S, Kamdar D, Tulunay Ugur OE, et al. Factors predictive of severity of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible. Head & Neck 2011, 33,1600–1605. [CrossRef]

- Alhilali L, Reynolds AR, Fakhran S. Osteoradionecrosis after radiation therapy for head and neck cancer: differentiation from recurrent disease with CT and PET/CT imaging. Am J Neuroradiology 2014, 35,1405–1411. [CrossRef]

- Ito K, Nakajima Y, Ogawa H, Taguchi K. Fracture risk following stereotactic body radiotherapy for long bone metastases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2022, 52,1,47-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi T, Demura S, Kato S, Shinmura K, Yokogawa N, Yonezawa N, Shimizu T, Oku N, Murakami H, Tsuchiya H. Effects of Radiation on the Bone Strength of Spinal Vertebrae in Rats. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2022, 47,12,E514-E520. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berk L. The effects of high-dose radiation therapy on bone: a scoping review. Radiat Oncol J. 2024, 42,2,95-103. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yaprak G, Gemici C, Temizkan S, Ozdemir S, Dogan BC, Seseogullari OO. Osteoporosis development and vertebral fractures after abdominal irradiation in patients with gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018, 11,18,1,972. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berk L. The effects of high-dose radiation therapy on bone: a scoping review. Radiat Oncol J. 2024, 42,2,95-103. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Choi YJ. Cancer treatment-induced bone loss. Korean J Intern Med. 2024, 39,5,731-745. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Adlakha P, Maheshwari G, Dhanawat A, Sinwer R, Singhal M, Jakhar SL, Sharma N, Kumar HS. Comparison of two schedules of hypo-fractionated radiotherapy in locally advanced head-and-neck cancers. J Cancer Res Ther. 2022, 18,S151-S156. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal AS, Jones J, Lin A. Palliative Radiation Therapy for Head and Neck Cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019, 1,105,2,254-266. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gewandter JS, Walker J, Heckler CE, Morrow GR, Ryan JL. Characterization of skin reactions and pain reported by patients receiving radiation therapy for cancer at different sites. J Support Oncol. 2013, 11,4,183-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park J, Lee JE. Comparison between 1-week and 2-week palliative radiotherapy courses for superior vena cava syndrome. Radiat Oncol J. 2023, 41,3,178-185. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu J, Yang G, An W, Wang W, Li F, Meng Y, Wang X. Correlations between the severity of radiation-induced oral mucositis and salivary epidermal growth factor as well as inflammatory cytokines in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2023, 45,5,1122-1129. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young J, Rattan D, Cheung A, Lazarakis S, McGilvray S. Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review. Scand J Pain. 2023, 15,24,1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam E, Wong G, Zhang L, Drost L, Karam I, Yee C, McCurdy-Franks E, Razvi Y, Ariello K, Wan BA, Nolen A, Wang K, DeAngelis C, Chow E. Self-reported pain in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2021, 29,1,155-167. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan BA, Pidduck W, Zhang L, Nolen A, Yee C, Wang K, Chow S, Chan S, Drost L, Soliman H, Leung E, Sousa P, Lewis D, DeAngelis C, Taylor P, Chow E. Patient-Reported Pain in Patients with Breast Cancer Who Receive Radiotherapy. Pain Manag Nurs. 2021, 22,3,402-407. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buwenge M, Macchia G, Arcelli A, Frakulli R, Fuccio L, Guerri S, Grassi E, Cammelli S, Cellini F, Morganti AG. Stereotactic radiotherapy of pancreatic cancer: a systematic review on pain relief. J Pain Res. 2018, 4,11,2169-2178. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Friedes C, Butala AA. Palliative radiotherapy for pancreatic cancer. Ann Palliat Med. 2024, 13,1,1-4. doi: 10.21037/apm-23-560. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biran A, Bolnykh I, Rimmer B, Cunliffe A, Durrant L, Hancock J, Ludlow H, Pedley I, Rees C, Sharp L. A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies of Chronic Bowel Symptoms in Cancer Survivors following Pelvic Radiotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15,16,4037. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bisson E, Piton L, Durand B, Sarrade T, Huguet F. Palliative pelvic radiotherapy for symptomatic frail or metastatic patients with rectal adenocarcinoma: A systematic review. Dig Liver Dis. 2024, 9,S1590-8658(24)00890-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanachai M, Theerapancharoen V, Laothamatas J, Pongpech S, Kraiphibul P, Chanwitayanuchit T, Pochanugool L, Dangprasert S, Sarnvivad P, Sinpornchai V, Kuonsongtum V, Pirabul R, Yongvithisatid P. Early neurological complications after stereotactic radiosurgery/radiotherapy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2001, 84,12,1729-37. [PubMed]

- Zaki P, Barbour A, Zaki MM, Tseng YD, Amin AG, Venur V, McGranahan T, Vellayappan B, Palmer JD, Chao ST, Yang JT, Foote M, Redmond KJ, Chang EL, Sahgal A, Lo SS, Schaub SK. Emergent radiotherapy for spinal cord compression/impingement-a narrative review. Ann Palliat Med. 2023, 12,6, 1447-1462. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gojsevic M, Shariati S, Chan AW, Bonomo P, Zhang E, Kennedy SKF, Rajeswaran T, Rades D, Vassiliou V, Soliman H, Lee SF, Wong HCY, Rembielak A, Oldenburger E, Akkila S, Azevedo L, Chow E; EORTC Quality of Life Group. Quality of life in patients with malignant spinal cord compression: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2023, 31,12,736. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vistad I, Cvancarova M, Kristensen GB, Fosså SD. A study of chronic pelvic pain after radiotherapy in survivors of locally advanced cervical cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2011, 5,2,208-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Robijns J, Censabella S, Bollen H, Claes S, Van Bever L, Becker J, Pannekoeke L, Bulens P, Van de Werf E. Vaginal mucositis in patients with gynaecological cancer undergoing (chemo-)radiotherapy: a retrospective analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022, 42,6,2156-2163. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of brachytherapy | Location of applicator |

| interstitial | the applicator is placed inside the tumor e.g., prostate cancer [9] |

| surface | a contact applicator used in the treatment of skin cancers [10] |

| intracavitary | the radiation source is placed within body cavities, e.g., in the uterus, oral cavity cancers or spinal canal cancers [11] |

| intraluminal | an applicator is inserted into the lumen of a cancer-infiltrated bronchus, e.g., irradiation of an intrabronchial lesion leads to its reduction and improved bronchial patency, thereby decreasing dyspnea and cancer pain [12] |

| intraoperative | an applicator is placed in the post operative cavity, e.g., following removal of a breast tumor [13] |

| Radionuclide | Cancer | Indicate | Pain relief effect | Pain-free period |

| Strontium-89 Chloride | Prostate [24,25] breast26, lung, head and neck, colorectal [27] |

Bone pain | 63–88% | 6 weeks – 6 months |

| Samarium-153- EDTMP | lung, prostate [28,29] breast, osteosarcoma30 |

Bone pain | 62–78% | 3–8 months |

| Radium-223- Dichloride | Prostate [31,32] | Castration resistant prostate bone pain |

41-72% | Up to 16 weeks |

| Rhenium-186- HEDP | Prostate [33], breast [34] | Bone pain | 38% and 82% | 5–12 months |

| Rhenium-188- HEDP | Prostate [35,36] | progressive hormone- resistant prostate carcinoma and bone pain |

64-76% | 6 weeks |

| Study | RT scheme |

Complete pain response |

Partial pain response |

| Steenland et al., 1999 [102] |

1 × 8 Gy 6 × 4 Gy |

72% 69% |

37% 33% |

| Koswing et al., 1999 [103] |

1 × 8 Gy 10 × 3 Gy |

79% 82% |

31% 33% |

| Roos et al., 2005 [104] | 1 × 8 Gy 10 × 3 Gy |

61% 53% |

15% 18% |

| Hartsell et al., 2005 [105] |

1 × 8 Gy 10 × 3 Gy |

65% 66% |

15% 18% |

| Foro Arnalot et al., 2008 [106] |

1 × 8 Gy 10 × 3 Gy |

75% 86% |

15% 13% |

| Nongkynrih et al., 2018 [107] | 1 × 8 Gy 5 × 4 Gy 10 × 3 Gy |

80% 75% 85% |

20% 20% 20% |

| Nguygen et al., 2019 [108] |

1 x 12Gy-16 Gy 10 x 3 Gy |

55% 34% |

52% 19% |

| Ryu et al., 2023 [112] | 1 x 16-18 Gy 1x 8 Gy |

60% 41% |

- |

| Nguygen et al., 2023 [109] | 2x 12 Gy | 83-94% | - |

| Radiotherapy as a double-edged sword - examples | |

| Painkiller in: | Pain Factor: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).