In this section, we explain how the literature answers the research questions in this study. We divided the results into three subsections. First, we introduce the DTs identified in the literature and discuss their applications along the building’s life cycle, from a cradle-to-cradle perspective (RQ1). Second, we investigate the integrations of the different DTs and how they contribute to the digitization of CE strategies in the building sector (RQ2). Then, we discuss how the DTs identified in the literature can help overcome the main challenges in the transition towards CE in the AEC industry (RQ3). Finally, we identify and discuss the main limitations and needs for improvement of the DTs (RQ4).

3.1. Digital Technologies for Circular Economy and Their Application Along a Building’s Lifecycle

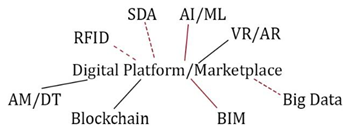

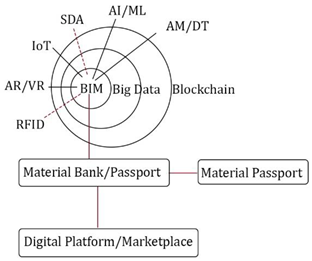

The systematic review of 71 papers revealed following ten DTs that are currently used to support the transition to CE in the AEC industry: Building Information Modelling (BIM), spatial data acquisition (SDA) technologies, artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML), Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain, digital twin, augmented reality and virtual reality (AR/VR), digital platform/marketplace, material passports (MP), and additive manufacturing and digital fabrication (AM/DF). This section discusses the applications of each DT along a building’s life cycle. For each subsection discussing the DT applications, we italicized the building’s life cycle phases (e.g., design product manufacturing, distribution, construction, etc.).

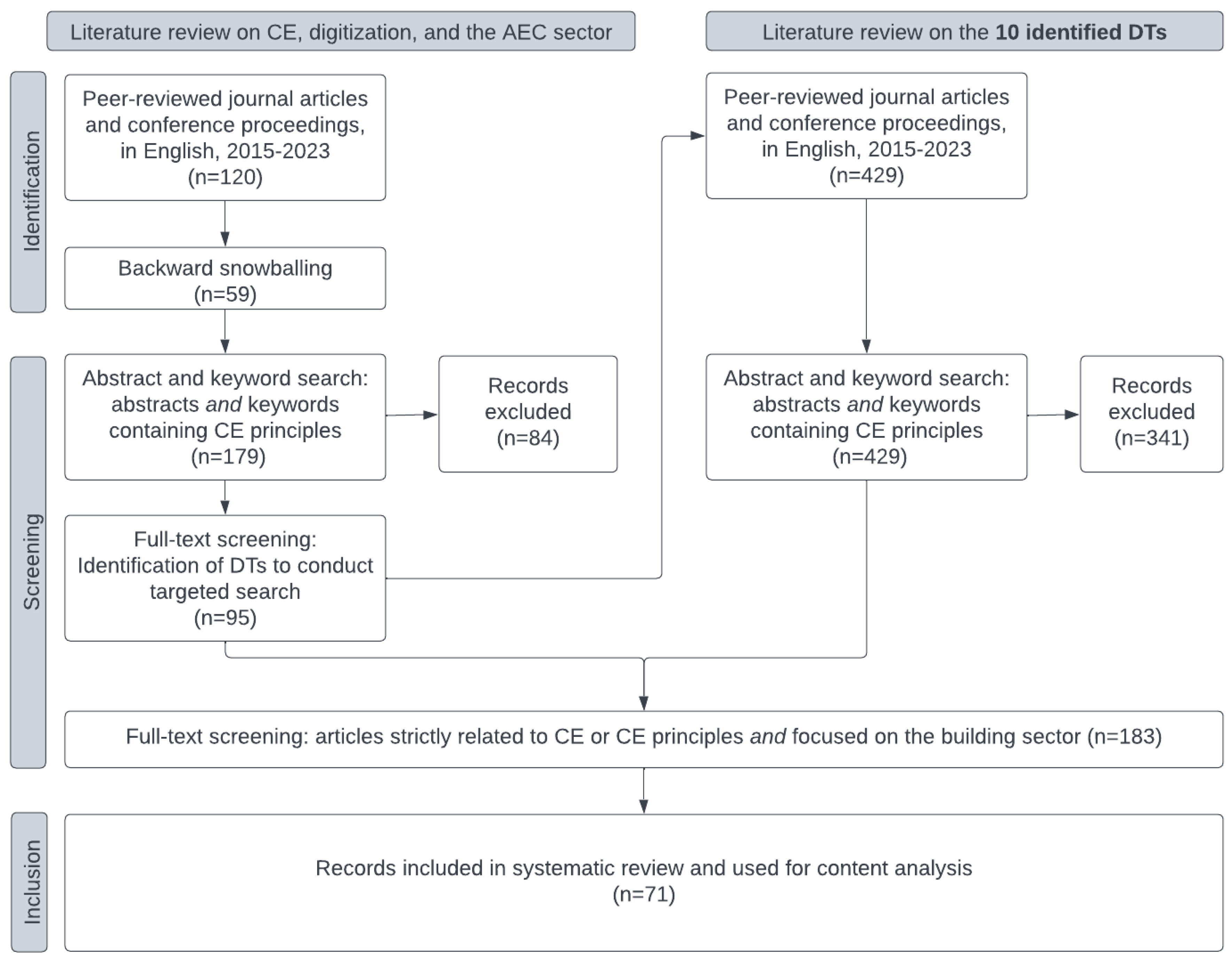

Table 4 summarizes the main DTs and their applications, while

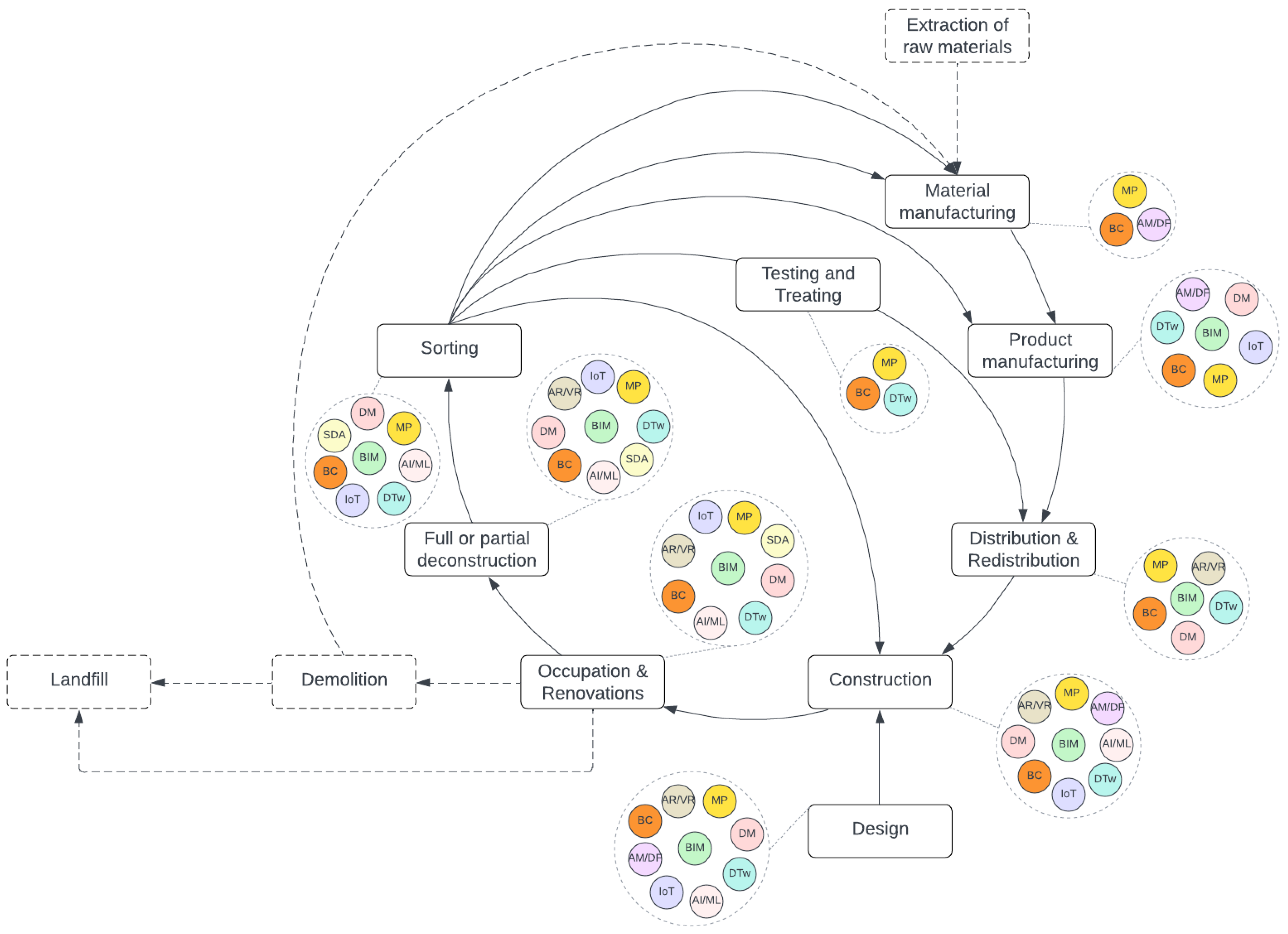

Figure 1 represents the distribution of DTs along each phase of a building’s life cycle, from a CE (cradle-to-cradle) perspective.

3.1.1. Building Information Modelling (BIM)

Building Information Modeling (BIM) has emerged as a prominent technology, getting a substantial interest due to its potential in addressing challenges associated with the transition to a CE (Li et al., 2020). BIM provides a comprehensive digital representation that encompasses critical information, including the 3D geometry of buildings, material properties, and the quantity of building elements. This wide range of attributes has rendered BIM a versatile tool, widely adopted by stakeholders in the AEC industries for purposes ranging from design, visualization, optimization, and cost estimation to maintenance, construction, and management planning (Honic et al., 2019).

At the design phase, BIM has been used to enable DfD in buildings. For example, Schaubroeck et al. (2022) have proposed novel workflows that enable the modeling of building joints and their disassembly, facilitating the storage and definition of deconstruction information in a 3D model database. Another possible use of BIM during circular design is assessing the salvage potential of different building components (Akanbi et al., 2018). BIM is also a powerful tool to enable building systems’ monitoring and timely maintenance during the occupation phase. By harnessing IoT devices and sensors, real-time data can be collected and fed into BIM systems, enabling automated monitoring and analysis of building performance (Elghaish et al., 2023; Xue et al., 2021). Real-time data in BIM models can also facilitate the tracking and management of components for potential reuse after the end-of-life stage. This approach proves particularly feasible when buildings are designed in modular systems and prefabricated building products (product manufacturing phase), allowing for easy disassembly and reassembly (Xing et al., 2020).

Machine learning algorithms can further enhance building automation by leveraging the large volumes of data generated, enabling predictive modeling, optimization, and decision-making processes within the BIM framework. The integration of IoT, big data, and machine learning with BIM holds significant potential to streamline workflows, improve efficiency, and enhance the overall management and operation of built environments (Gordon et al., 2023).

The potential of BIM has also been explored for the building deconstruction phase. Van den Berg et al. (2021) investigated how BIM can reorganize deconstruction practices by (1) analyzing existing building stock in a 3D environment, (2) labeling and storing reusable elements in digital platforms, and (3) simulating the deconstruction process in a 4D environment. Moreover, to address safety concerns and improve the effectiveness of building element disassembly, the concept of “8D BIM” has been introduced in the literature. This approach involves incorporating safety information into the geometric model during the design and deconstruction phases (Charef, 2022). By considering safety factors during the modeling process, the potential risks and hazards associated with the disassembly process can be better identified and mitigated. The integration of safety information within BIM models enhances the accuracy and predictability of disassembly projects (Sanchez et al., 2021).

After deconstruction, BIM can also be applied to material sorting. Guerra et al. (2020) developed a 4D-BIM approach that enables the visual planning of on-site waste management, specifically focusing on concrete waste. By integrating time-related information into the BIM model, construction waste can be quantified and managed effectively, promoting reuse and recycling practices. The sorted materials can be integrated into a 3D database and integrated into BIM, which offers a platform for companies to list reclaimed materials, thus facilitating the matching of supply and demand during the redistribution phase. Through this platform, BIM serves as an interconnected medium for stakeholders to exchange material properties information, such as maintenance, deconstruction, replacement, and reuse data (Cetin et al., 2022; Elghaish et al., 2023).

3.1.2. Spatial Data Acquisition

Spatial data acquisition (SDA) tools aim at collecting data on the location, shape, and attributes of physical objects. Examples of SDA digital tools include geographic information systems (GIS), light detection and ranging (LiDAR), simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) photogrammetry, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UMV). SDA has been used in CE research to capture data from the existing building and materials stocks to enable CE throughout the building’s life cycle. While methods like LiDAR are used to capture data at a building’s scale, GIS has emerged as a prevalent computational tool to examine the dynamic patterns of material transactions at a regional scale (Mastrucci et al., 2017).

On a building’s scale, studies have applied SDA techniques to create as-built BIM models of existing buildings (occupation phase), a framework commonly referred to as Scan-to-BIM. For example, Kovacic & Honic (2021) used laser scanning and ground penetrating radar techniques to capture the geometry and material composition of building components, respectively. They developed a framework to capture and integrate the data into a BIM model with the aim to enable material passports (MP). Meanwhile, Mêda et al. (2023) demonstrated the potential of mobile LiDAR technology and Scan-to-BIM to creating an accessible methodology to enable digital waste audits during building renovation. They tested the methodology in an apartment case study and were able to collect all the necessary data in four hours, including estimated quantities of the materials present in the apartment. Similarly, (Gordon et al., 2023) applied mobile photography and consumer-grade LiDAR devices followed by photogrammetry and point cloud data analysis to perform a pre-deconstruction Scan-to-BIM. The authors focused their analysis on the potential recovery of structural steel components.

Researchers have also studied the potential of SDA techniques to estimate building material flows at a city scale. Stephan & Athanassiadis (2018) paved the way to future studies by creating a framework to quantify, spatialize, and estimate material flows in urban stocks. With a focus on material replacement flows during building renovation, the authors created archetypes of representative buildings based on parameters like land use, building age and height, and building components and materials. Then, they integrated the archetypes with a GIS model to spatialize the buildings and materials over time for the city of Melbourne, Australia. Mohammadiziazi & Bilec (2023) used GIS to collect data on the building footprint of commercial buildings in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, while other building attributes such as height, exterior wall materials, floor count, and window-to-wall ratio were estimated using a combination of LiDAR, photogrammetry, and image processing framework. The study’s goal was to estimate the material flows during building renovation for the entire commercial building stock in Pittsburgh. Honic et al. (2023) combined similar SDA techniques to calculate building material intensities and predict building stocks. They used GIS data to obtain the gross volume of a residential building in Vienna, Austria, which the authors considered an archetype representative of other residential buildings from the same period. LiDAR was used to capture the building’s geometry, and a pre-demolition audit was conducted to investigate the types and occurrences of building materials. Then, using GIS data, the authors estimated the material stocks of similar residential buildings in the city of Vienna.

Both studies from Mohammadiziazi & Bilec (2023) and Honic et al. (2023) have the goal of creating data to enable urban mining (Heisel and Rau-Oberhuber, 2020), which would promote the recirculation of building materials. GIS has been extensively applied in similar urban mining studies, enabling spatial data visualization, management, analysis, and modeling. Other examples include Yuan et al. (2023), Wang et al. (2019), Sprecher et al. (2022), Kleemann et al. (2017), and Heeren & Hellweg (2019). In this context, 4D GIS has emerged as a significant approach for identifying temporal patterns of material stocks and their evolution (Rajaratnam et al., 2023).

Finally, SDA technologies can be used to assess and classify waste materials to create libraries of reusable materials during the sorting phase. Yu & Fingrut (2022) used UAVs, hand-held cameras, laser scanning, and photogrammetry to generate and process images from wood waste from wood mills and logging sites in London, UK. The authors then created a material database library of regular and irregular wood for reuse and recycling and discussed the possibility of applying a similar methodology to help sort other waste streams in the future. Likewise, Wu et al. (2016) proposed a GIS-based approach for quantifying the demolition waste from the final disposal to improve waste management strategies and recycling rates.

3.1.3. Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning

Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to the capacity of computers or machines to imitate human cognitive abilities, and it comprises several sub-branches that employ diverse techniques. For instance, Machine Learning (ML) involves training algorithms to learn from data and identify patterns to make decisions with minimal supervision, while Deep Learning is capable of self-training for more complex tasks (Stuart & Norvic, 2003). Everyday examples of AI applications include chatbots, face recognition systems, voice-controlled digital assistants, and online language translators. In the AEC industry, emerging applications include project schedule optimization and worker safety improvement (Setaki and van Timmeren, 2022).

At the design phase, ML has been used to aid DfD by predicting the reusability of deconstructable building materials. Rakhshan et al. (2021) employed supervised ML algorithms to identify the factors contributing to the reusability of structural elements in buildings. The authors adopted a questionnaire-based methodology to collect data from the construction industry, enabling an initial assessment of the technical reusability of existing buildings designed for deconstruction. At the occupation phase, AI can be integrated with Digital Twins to enable timely maintenance in buildings. Cetin et al. (2022) applied a novel digitization framework to create a digital twin of the Dutch housing stock through AI. The integration of AI enhanced the digital system by enhancing the model in terms of recognizing building elements, measuring dimensions, and detecting anomalies through image recognition system in the skin elements of the buildings.

AI models have also been applied to estimate waste generation during the construction and deconstruction phases. Lu et al. (2021) developed and compared various AI models, including Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Grey Models (GM), Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), and Decision Trees to estimate construction waste generation. The results indicated that GM and ANN exhibited higher prediction accuracy, albeit with challenges in interpretation. On the other hand, MLR and DT showed lower accuracy but provided more easily interpretable information. AI and ML models can also help predict, model, simulate, and optimize various aspects during the deconstruction and material sorting phases of a building. For example, Oluleye et al. (2023) combined Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Deep Neural Network (DNN) models to predict and sort post-deconstruction materials and optimize material collection and site selection for recycling facilities. Similarly, Davis et al. (2021) developed a deep CNN to identify and sort construction materials post-demolition with a 94% accuracy rate. The authors highlighted the potential of integrating CNN with robotics as a means of automating on-site sorting of post-deconstruction or demolition waste.

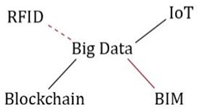

3.1.4. Internet of Things (IoT)

The Internet of Things (IoT) is characterized as a self-configuring information network, based on standard and interoperable communication protocols, where physical and virtual entities possess identities, physical attributes, and virtual personalities, and are seamlessly integrated into the network through intelligent interfaces (Li et al., 2014). IoT enables smartphones, electronic devices, and machines to communicate with each other by creating a network of things through technologies such as Radio Frequency Identification System (RFID), wireless sensor networks and cloud computing (Li et al., 2014). The large amount of data produced from this communication is analyzed with big data analytics to identify the hidden patterns and provide valuable insights (Lopes de Sousa Jabbour et al., 2018).

IoT has the potential to support the transition to CE by enhancing traceability and visibility throughout the construction process, facilitating dynamic decision-making, promoting collaboration among stakeholders, and improving post-deconstruction resource management (sorting phase) (Zhai et al., 2019). For instance, Giovanardi et al. (2023) developed an IoT framework for tracking, storing, and sharing data related to façade systems from product manufacturing to design, maintenance (occupation phase), and deconstruction. Within this framework, five functions were identified, including the implementation of smart contracts to enhance safety and circularity within the supply chain, optimization of processes and predictive assessments to reduce resource consumption, adoption of a data-driven approach to redesign products and processes, support for new business models based on service exchange to promote dematerialization in the market, and the establishment of a digital materials database to enhance material reuse and recycling efforts. More applications of IoT to building circularity involve BIM integration and were discussed in the BIM section above.

3.1.5. Blockchain

Blockchain is based on a distributed peer-to-peer system that enables secured transaction of data by allowing the information flowing through the project life cycle without missing and manipulating of data (Wang et al., 2017). It has five attributes which are transparency of transactions, immutability (i.e., data cannot be modified or deleted), security, consensus, and smart contracts (Arun et al., 2019). From the CE perspective it promotes increasing functionality, efficiency, and visibility by providing decentralized tracking of information such as material and waste flows (Setaki and van Timmeren, 2022). Blockchain technology also provides opportunities for maintaining the value of resources throughout their life cycle (Wang et al., 2017). With the integration of BIM and GIS, blockchain facilitates secure peer-to-peer collaboration within the supply chain (Cetin et al., 2021).

Within the CE context in the AEC industry, blockchain technology has emerged as a promising solution for effectively tracking material flow throughout the entire building life cycle, along with material passports, IoT, and digital platforms (Cetin et al., 2021). This integration of technologies facilitates slowing resource loops through automated and timely maintenance and closing resource loops through the redistribution of materials for reuse. For example, blockchain databases can function as geospatial maps that are interconnected with BIM to enable the efficient tracking of materials for supply and demand purposes (Copeland & Bilec, 2020). Another Blockchain-BIM integration is proposed by Elghaish et al. (2023). The authors developed an integrated framework that connects blockchain adoption with the construction supply chain, from building occupation to deconstruction, and material sorting, treatment, and redistribution. The authors suggest the development of BIM families derived from existing buildings, which can be shared on a secure and interconnected platform. This platform enables tracking material details, quantities, delivery destinations, and the treatment process of hazardous products/materials. Additionally, it facilitates creating a bank of BIM families for reusable items. The authors further recommend the integration with IoT to fully automate the system, fostering collaboration among designers, asset owners, and government authorities.

Blockchain can also be integrated with digital twin technology. Teisserenc and Sepasgozar (2021a,b) have developed a novel theoretical and conceptual model for integrating blockchain and digital twins in the construction. They utilize BIM and its dimensions as fundamental data for the blockchain-digital twin framework. The use of blockchain-based networks enables decentralized collaboration through automated processing via smart contracts. It also enhances data sharing within a decentralized data value chain (Teisserenc and Sepasgozar, 2021a). The integration of blockchain technology ensures cybersecurity, data integrity, immutability, traceability, and transparency or privacy of information through decentralized storage systems, cloud computing systems, and IoT network management (Teisserenc and Sepasgozar, 2021b).

3.1.6. Digital Twin

The concept of digital twin has gained prominence as a transformative approach within the context of CE and the built environment. Digital twin represents a virtual replica or portrayal of a physical object, system, or process, achieved through the integration of real-time data, simulations, and advanced analytics (De Reuver et al., 2018). This dynamic and interactive model closely mimics the characteristics, behavior, and performance of its physical counterpart, enabling real-time monitoring and optimization of the associated object or system. Consequently, digital twin fosters improved decision-making, predictive maintenance strategies, and enhanced overall performance across diverse domains, including manufacturing, infrastructure, and the built environment (Teisserenc and Sepasgozar, 2021b).

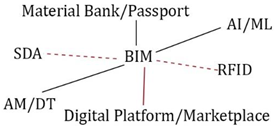

Within the existing literature, BIM has predominantly served as the digital twin platform due to its capacity to store building information enriched with real-time data acquired from physical assets (Jemal et al., 2023). To ensure the effective functioning of digital twins, three key components are essential: a 3D model of the building, integration with a wireless sensor network, and the application of big data analytics (Tao et al., 2018). Furthermore, to enable a fully automated system, researcher proposed the integration of digital twins with machine learning techniques driven by data collected from sensors and simulations (Cetin et al., 2022).

Digital twin technology has emerged as a prominent tool for effectively managing resources in buildings and infrastructure over their entire lifespan, offering the potential to develop a comprehensive 3D material database for lifecycle data management (Cetin et al., 2021). Cetin et al. (2022) presented a framework wherein a 3D digital twin of the Dutch building stock was generated by integrating scanning technologies, UAVs, BIM, and AI. This framework offers support in enhancing work processes, facilitating data access, sharing, and improving maintenance operations during the building occupation phase. Although the digital twin concept remains relatively vague, it also has the potential of proactively analyzing and optimizing design and construction phases, and planning for deconstruction (Mêda et al., 2021).

3.1.7. Augmented Reality & Virtual Reality (AR & VR)

Augmented reality (AR) is characterized as an extension of the physical world by incorporating computer-generated 3D models, while virtual reality (VR) entails the creation of an immersive virtual environment that replaces the user’s perception of the actual surroundings with a digitally simulated environment by utilizing multi-display setups (Jemal et al., 2023). Within the AEC industry, AR and VR technologies are harnessed in conjunction with BIM to enhance project visualization capabilities (Setaki and van Timmeren, 2022). The integration of AR and VR offers valuable support across various stages of the AEC life cycle, including stakeholder collaboration, building design, design review, construction, operation (occupation phase), and management (Setaki and van Timmeren, 2022). However, despite the potential benefits, the adoption and utilization of AR and VR in the AEC industry remain in a preliminary phase, requiring further research to improve workflows and develop novel technological resources in this domain (Caldas et al., 2022).

Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) technologies offer the ability to visualize various aspects of a building and its construction process, thereby enabling designers and stakeholders to assess deconstruction strategies during the design phase and facilitating the deconstruction process (Caldas et al., 2022). These technologies also allow for the use of virtual models in design, construction, and maintenance stages, enabling the selection of appropriate materials for the building’s maintenance (Caldas et al., 2022). Through integration with IoT, BIM, robots, 3D printing, and UAVs, AR and VR present significant opportunities for optimizing material usage and promoting material reuse (Setaki and van Timmeren, 2022). For example, O’Grady et al. (2021) proposed the integration of VR and BIM in a model demonstrating the implementation of CE design principles in the built environment. By incorporating BIM, digital twin, and VR technologies, their prototype building showed visual representations of materials and components that could be reintroduced into the supply chain at the end of their life cycle (i.e., redistribution phase). Furthermore, the VR models demonstrated opportunities for future renovation, disassembly, deconstruction, and demolition, emphasizing the benefits of AR and VR in supporting CE in the construction industry (O’Grady et al., 2021).

3.1.8. Digital Platform / Marketplace

Digital platforms or marketplaces are software-based systems that are characterized as layered modular systems with standardized interfaces, enabling interoperability between different modules (Baldwin and Woodard, 2009). In the existing literature, digital platforms are often categorized into two main approaches: tool-based platforms that focus on enhancing the production process, with incorporating BIM, and collaboration platforms that bring together diverse stakeholders to facilitate improved engagement and collaboration (Kovacic et al., 2020).

Digital platforms have been increasingly explored in the AEC sector. For example, Luciano et al. (2019) have developed a multi-user platform designed for the management of construction projects in green public procurement, with a focus on resource management, recirculation of materials, and environmental impact reduction. This platform encompasses several elements, including technical standards, environmental laws, databases, and interactive maps, and serves as a comprehensive tool for controlling all stages and procedures of construction projects. By involving all participants in the supply chain throughout the entire project’s life cycle, this platform provides an integrated and holistic approach to transparently, efficiently, and comprehensively manage all phases associated with the development of public works.

Other studies have explored the potential of digital platforms to manage data throughout the building’s life cycle. In a study by Xing et al. (2020), a digital platform utilizing BIM digital twins within a Cloud system was developed to enable the identification and exchange of reusable components. This platform facilitates real-time tracking, monitoring, and management of lifecycle information, including ownership history, maintenance records, technical specifications, and physical characteristics, while fostering data sharing among stakeholders. Similarly, Kovacic et al. (2020) developed a digital platform integrated with BIM to optimize resource utilization, predict waste generation, and facilitate recycling. This platform aims to enhance productivity, optimize material usage throughout the CE life cycle, and promote mutual learning and coordination.

Digital marketplaces can also be developed to create material inventories of secondary resources sourced from renovation, maintenance, and deconstruction operations, thereby contributing to narrowing and closing material loops by connecting supply and demand chains for material redistribution (Cetin et al., 2022). Cetin et al. (2021) have proposed a framework that leverages digital platforms integrated with BIM, GIS, and blockchain technologies to create interconnected networks of knowledge and value. These platforms enable stakeholders such as architects, engineers, consultants, and demolition contractors to exchange information and provide expert insights regarding the utilization of reclaimed materials in renovation or new construction projects (Cetin et al., 2022).

3.1.9. Material Passports

The concept of the material passport (MP) has been developed to digitally store comprehensive material information throughout the entire life cycle of a product, facilitating its recovery during the end-of-life phase. MPs serve as digital records containing datasets that identify materials, including their characteristics, location, history, and ownership status. These passports prove valuable in evaluating material flows and determining the market value of different qualities of used building materials (BAMB, 2020). For example, Copeland and Bilec (2020) developed a geospatial mapping system integrated with BAMB that collaborates with non-profit organizations or third-party entities to recertify, upcycle, test, and track materials. Sprecher et al. (2022) highlighted the value of categorizing materials based on their quality in a database, enabling detailed planning and efficient matching of circular demolition and material flows.

In the existing literature, the implementation of MPs has primarily been carried out within BIM or other digital platforms (Cetin et al., 2021). For example, Honic et al. (2021) employed a BIM-based MP to assess the recycling potential and applicability at the end-of-life stage of an existing building. Similarly, Cai and Waldmann (2019) proposed a material and component bank that serves as a management entity for transferring materials and components from deconstructed constructions to new projects. This bank, which operates throughout the phases of construction planning, utilization, maintenance, demolition, sorting, and redistribution, relies on a database supported by BIM to ensure up-to-date material information throughout a building’s lifetime.

3.1.10. Additive Manufacturing and Digital Fabrication

Additive manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D printing, has been increasingly explored in the construction industry and referred to as one of the pillars of Industry 4.0 to enable CE (Giglio et al., 2022; Pasco et al., 2022). AM is a type of digital fabrication (DF), where the manufacturing process is controlled by a computer and based on computer-aided design (CAD). In AM, materials are printed in layers to form a product, and each layer uses a single material as input. This layered manufacturing process can be combined with DfD principles during the design phase to create building products and assemblies that are easy to disassemble, which enables the recovery of each material for recycling (Giglio et al., 2022). Using recycled materials in 3D-printing was found to enhance resource efficiency and reduce carbon emissions, energy consumption, and waste generation, while maintaining comparable quality and mechanical performance when compared to conventional materials (Olawumi et al., 2023).

AM can be used to manufacture materials or building products using recovered waste materials like biochar for Portland cement fabrication (Vergara et al., 2023) or polystyrene and wool for insulation blocks (de Rubeis, 2022), or biobased and renewable materials like clay (Alonso Madrid et al., 2023), wood particles (Fico et al., 2022; Kromoser et al., 2022, 2023), or mycelium-based materials (Bitting et al., 2022). Another promising area is using AM to fabricate replacement parts during the remanufacturing of building products, which is especially beneficial when the manufacturer has discontinued the production of a product’s component (Giglio et al., 2022; Schlesinger et al., 2023).

3D-printed materials can also be combined with off-site construction to minimize waste during the construction phase (Oval et al., 2023; Pasco et al., 2022). In fact, researchers are experimenting with 3D-printing entire structures and buildings using natural materials. For example, a 3D-printed housing model was designed and built using a biopolymer made of recovered waste materials (i.e., lignin, a byproduct of paper manufacturing) and natural fibers (Giglio et al., 2022). The housing model was designed to follow CE principles: DfD, biobased materials, recycled materials, and durable structure.

3.3. Digital Technologies and the Barriers for a Circular Economy Transition in the Construction Industry

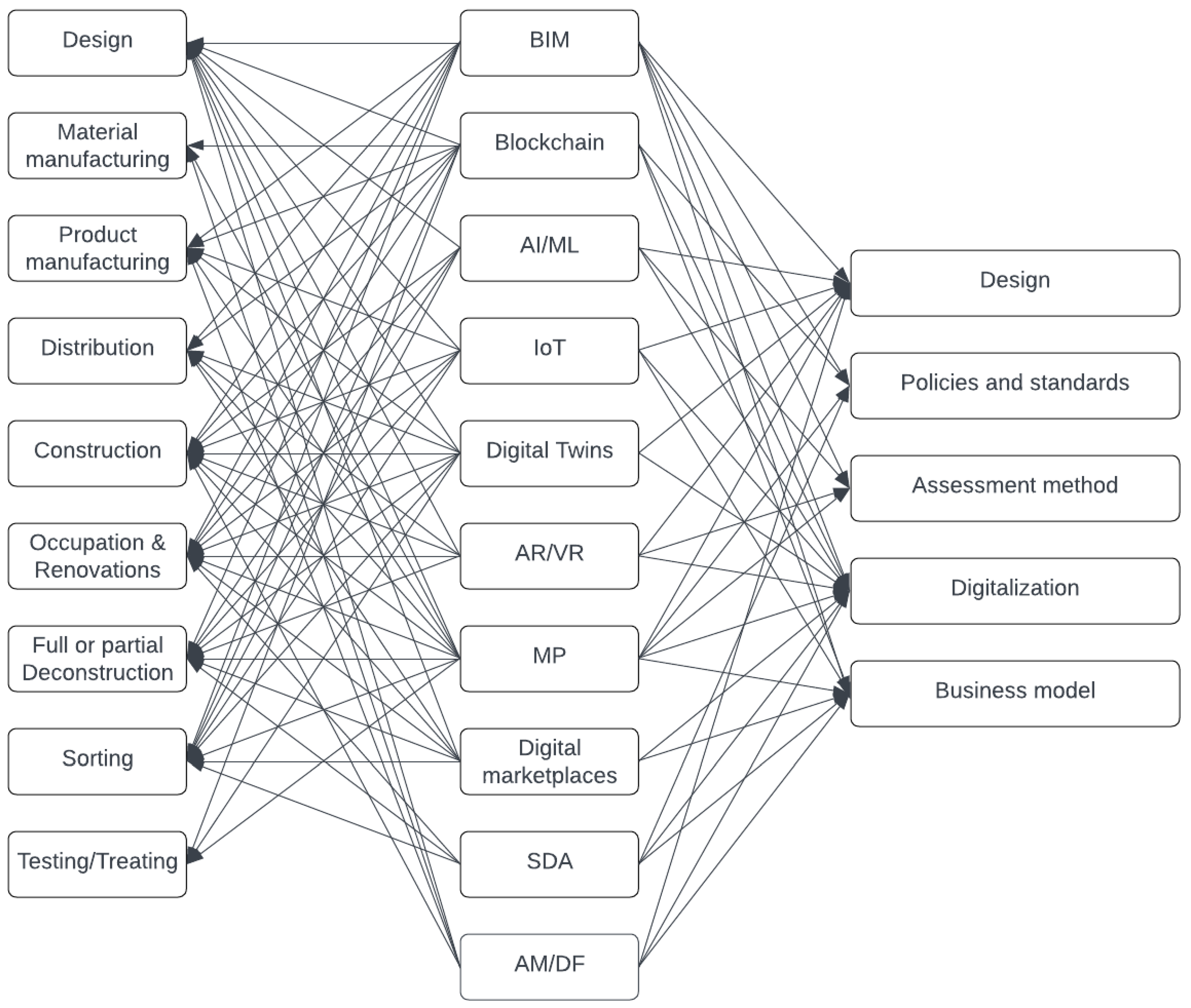

The challenges for CE implementation in the AEC industry are well documented, and several reviews and empirical studies have been conducted on the topic in the past few years (e.g., Wuni, 2022; Cruz Rios et al., 2021; Ghisellini et al., 2018; Hart et al., 2019; Hossain & Ng, 2018; Pomponi & Moncaster, 2017; Cruz Rios et al., 2015). Recently, Gasparri et al. (2023) identified and ranked the barriers in the literature from both reviews and empirical studies. The top 5 ranked barriers as addressed by the literature were: 1) Design; 2) Policies and standards; 3) Assessment method; 4) Digitalization; and 5) Business models. In this section, we explain how the DTs explored in this study offer pathways to overcome those barriers. In particular, the digitization barrier is the overarching theme of this study and will be explored in terms of integration of DTs in the next section.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationships between the phases of a building’s life cycle (left), the DTs (center), and the CE barriers (right).

3.3.1. Design

The design barrier refers to the need for innovative and integrated CE design strategies, especially strategies that move from recycling to reducing and reusing materials (Gasparri et al., 2023; Keles et al., 2024). DfD strategies can highly benefit from innovative design technologies. For example, Schaubroeck et a. (2022) have proposed the integration of disassembly parameters on BIM. Rakhshan et al. (2021) have employed ML algorithms to predict the reusability of building components. Another example is the design of a building or building system to be constructed in several single-material recoverable layers (Giglio et al., 2022). Future research opportunities include the integration of BIM and VR to visualize the disassembly sequence of a building during the design phase, the integration of digital twins, IoT, and MPs to enable on-site material reuse during building retrofits, AI/ML algorithms to automate the DfD decision-making process by integrating factors like salvage potential, environmental impacts, life cycle cost, and safety considerations, or AM/DF technologies to enable the production of prefabricated modules designed for future disassembly and reassembly.

3.3.2. Policies and Standards

The need for CE-specific policy packages and standards was identified as another recurring challenge in the literature (Gasparri et al., 2023). Researchers have highlighted the need for higher government support in terms of building codes, standards for material reuse, mandatory labeling or building products and materials, regional and municipal action plans, recycling and reuse targets, mandates, and financial incentives for CE in the AEC industry (Keles & Yazicioglu, 2023). While there are studies on policy interventions for the CE transition, there is still a lack of information regarding how DTs can contribute to these policy interventions, including quality standards, procurement criteria, taxation, and reforms in construction and demolition activities (Yu et al., 2022). However, researchers have highlighted the DT potential to support CE policies and standards by generating, storing, and disseminating data, enhancing accountability and transparency, and enabling secure data management along the supply chain.

DTs can serve as effective tools to engage governmental structures in developing awareness of the CE by revising existing codes and regulations or introducing new policies (Jemal et al., 2023). A shift towards digitalizing regulatory processes would facilitate the adoption of digital technologies in the built environment (Teisserenc and Sepasgozar, 2021b). For instance, blockchain and legal smart contracts can enhance accountability and traceability of legal information, digital identities, and data ownership, with addressing the lack of standardization (Teisserenc and Sepasgozar, 2021b).

SDA tools like GIS can generate critical data on material flows to inform CE policymaking and urban planning. For example, Wang et al. (2019) developed a 4D GIS model to analyze C&D waste flows and applied this model in a case study conducted in Shenzhen, a city experiencing rapid urban renewal. The proposed 4D GIS model demonstrated the ability to accurately capture the current state and future trends of C&D waste collection and transportation. Another example is introduced in Kleemann et al. (2017): the authors presented a GIS-based analysis to validate the demolition statistics and waste generation in Vienna by applying change detection based on image matching. They discussed that relying solely on statistical data for estimating demolition waste generation is insufficient in accurately predicting the amount and composition of waste. However, when this statistical data is combined with information regarding planned construction projects and urban development through GIS, it becomes possible to project and coordinate the potential utilization of recycled materials. Additionally, GIS can be employed in conjunction with BIM and MPs to facilitate urban data management, promote energy-efficient building and urban design practices, optimize building climate requirements, and monitor supply chain logistics and material flows (Wang et al., 2019).

3.3.3. Assessment Methods

The lack of assessment methods that integrate environmental, social, and economic impacts of CE strategies have been extensively discussed in the literature. Researchers have discussed the need for dynamic assessment methods that account for the socioeconomic changes over time, and the need for tools to aid decision-making in early design phases (Gasparri et al., 2023)

In the context of the CE, BIM emerges as a transformative technology that offers significant potential for mitigating environmental impact and advancing sustainability in the built environment through its comprehensive digital representation and analytical capabilities (Charef and Emmitt, 2021). The emphasis is primarily placed on closing material loops through recycling and reuse practices at the end of a product’s life cycle, as well as incorporating secondary materials into the production process. According to Xue et al. (2021), to advance sustainability objectives, the integration of BIM with LCA can be pursued across three distinct levels. At the first level, BIM can be employed to accurately quantify materials and architectural elements, thereby facilitating the generation of environmental life cycle inventory data. BIM can be further utilized as a design tool by incorporating environmental information into its framework. This integration enables designers to make informed decisions and consider environmental factors throughout the design process. Finally, there is potential to develop automated processes that rely on environmental life cycle inventory data and specialized software. By automating certain aspects of the assessment process, the efficiency and accuracy of sustainability evaluations can be enhanced. Overall, the integration of BIM and LCA at these three levels offers a promising pathway to achieve and enhance sustainability objectives in the built environment (Xue et al., 2021).

3.3.4. Business Model

Another frequently discussed challenge in the CE literature for the AEC sector is the need for new circular business models such as product leasing or product-service systems that promote material durability and timely maintenance, and the need for promoting supply chain collaboration and value co-creation (Gasparri et al., 2023). While circular business models often demand significant cultural and behavioral changes that are beyond the technological domain, a few DTs can have critical roles in this transition. For example, digital platforms function as virtual marketplaces that facilitate the exchange of goods and services, while also enabling the operation of product-service systems. They play a vital role in supporting CE practices by creating opportunities for the development of circular products and services (Konietzko et al., 2019; Gawer & Cusumano, 2014). AM offers flexibility for remanufacturing businesses by aiding material reuse and low-cost production of small batch parts that can be used to replaced damaged or missing parts in existing products (M. T. Islam et al., 2022). Blockchain technology and peer-to-peer transactions can enhance financial inclusivity, transparency, and accountability in CE initiatives, and maintain the value of building products throughout their life cycle (Wang et al., 2017). IoT technologies like RFID can be integrated with MPs and blockchain to enable real-time data collection and monitoring and enable timely maintenance, which is invaluable in circular business models (Cetin et al., 2021). Blockchain and IoT can also be integrated with GIS to promote collaboration among the supply chain and the effective management of end-of-life resources (Zhai et al., 2019; Cetin et al., 2021).

Despite the DT potential in enabling circular business models, research on those DT applications has remained largely theoretical. More case studies and pilot projects are needed to demonstrate the feasibility of product-service systems and other circular business models in the AEC industry, and to test the potential applications of the DTs mentioned above.

3.4. Digital Technology Limitations and Future Research Needs

The integration of digital tools for CE transition in the built environment presents promising opportunities for resource optimization and sustainable practices. However, several research gaps exist, indicating directions for future investigations. Technological challenges were identified in the literature from different perspectives. There is a growing development on addressing the technological challenges; however, solving problems about the circular transition in the built environment remains limited (Yu et al., 2022). In this section, we identified these challenges under four topics: (1) data management challenges, (2) BIM and GIS limitations and clarity issues, (3) validation and automation challenges, (4) collaboration and information management challenges.

3.4.1. Data Management Challenges

Data management is one of the most frequently challenges mentioned limitations in literature. It has been suggested that tracing the information and collecting in a physical and digital memory (e.g., material passport) would solve the problem of findability, accessibility, and loss of a large amount of information over time (Giovannardi et al. 2023). However, there are still problems with data quality and reliability as the data is not readily accessible or easily interpreted (Giovannardi et al., 2023; Yuan et al., 2023; Heeren and Hellweg, 2019). Furthermore, errors occurred from various reasons such as missing data or missing elements due to the complexity of the construction process (Gordon et al., 2023). When predicting demolition waste generation based on statistical data, assumptions need to be made, which can introduce uncertainties in the results (Kleemann et al., 2017). Moreover, data collection before demolition often relies on expert estimates, as materials are collected by different subcontractors at different times. This could cause uncertainties in the dataset (Sprecher et al., 2022).

Keeping precise and up to date data requires skills, time, and investment (Cetin et al., 2022). To ensure the usability of data in end-of-life and maintenance phases, it is essential to update the data according to specified requirements. These specifications should be standardized to facilitate multiple activities (Charef, 2022). Uncertainties in data collection can arise due to outdated construction plans of demolished buildings and the reliance on literature from different geographical regions (Kleemann et al., 2017; Charef and Emmitt, 2021). Therefore, BIM and GIS models should be updated regularly throughout the life cycle of buildings and building products. Finally, poor digitalization in the construction industry is still a significant problem, which may cause cybersecurity and privacy invasion risks during data management (Li et al., 2020; Teisserenc and Sepasgozar, 2021a). Collaborative efforts and interdisciplinary research are necessary to update data and manage risks in the AEC industry.

4.1.2. BIM & GIS Limitations and Clarity Issues

Despite being widely recognized as a valuable digital tool in the context of the CE in the built environment, BIM still has several challenges that need to be addressed. One of the major concerns is the quality of BIM models, as they rely on complex and accurate information shared among stakeholders throughout the life cycle of building products (Charef, 2022; Guerra et al., 2020). Additionally, there is a lack of accurate BIM & GIS models prior to deconstruction process for the existing building stock due to using traditional drawings, schedules, and instructions (Guerra et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Kleemann et al., 2017). The accuracy of proposed approaches and estimations is thus dependent on the availability of BIM data and the quality of GIS data. Uncertainties arise due to the lack of clarity in the generalization of GIS and BIM, particularly in the categorization of buildings, which can affect the reliability of results (Gordon et al., 2023; Kleemann et al., 2017).

Moreover, BIM is still insufficient for developing disassembly models, as the process is time-consuming and requires significant processing power to accurately draw and model products in detail (Schaubroeck et al., 2022; Sanchez et al., 2020). Although BIM has proven to be a well-established tool for assessing, modeling, and optimizing material resources, further development is needed to address data management issues throughout the value chain, requiring the commitment of the entire AEC community (Kovacic et al., 2020). Furthermore, the adoption of CE principles within BIM, particularly in relation to LCA, is still limited, with a lack of focus on recyclability, reusability of materials, as well as renovation and demolition processes (Xue et al., 2021). This disconnection between BIM tools and end-of-life tools, C&D waste management tools, and LCA tools hinders open data exchange and integration between them, including material databases (Akbarieh et al., 2020). Addressing these challenges and enhancing the integration and compatibility of BIM with other tools and frameworks is crucial for advancing the CE agenda in the built environment.

4.1.3. Validation and Automation Challenges

A significant challenge in research studies within the context of the CE transition in the built environment is the need for validating frameworks and methodologies across different scales or cases. While several papers have proposed frameworks to address various challenges related to the CE transition in the built environment, these solutions still require validation through large-scale real-life cases in diverse contexts and settings (Elghaish et al., 2023; Xing et al., 2020). Specifically, frameworks focusing on end-of-life processes such as reuse, recycling, deconstruction, and material bank platforms have been developed but are still in a preliminary phase, as they represent novel systems within the CE transition in the built environment. Moreover, these studies have explored the integration of digital tools such as BIM, cloud computing, and blockchain technologies which hold significant potential for enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of CE practices in the built environment. However, due to their novelty and complexity, there is a need for more extensive research and investigation through real-life case studies to fully understand their applicability and effectiveness in different contexts (Elghaish et al., 2023; Xing et al., 2020; Guerra et al., 2020; Heisel and Rau-Oberhuber, 2020; Copeland and Bilec, 2020; Ge et al., 2017; Setaki and van Timmeren, 2022).

Moreover, it should be noted that all the studies included in the selected papers were conducted at specific sites, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other cities or regions. Therefore, the proposed solutions and strategies may not necessarily be applicable or effective in different case studies (Jemal et al., 2023; Cetin et al., 2022). Additionally, further research is needed to validate the findings across organizations of varying sizes and with the integration of diverse stakeholders (Honic et al., 2021). Studies that employed interview and workshop methodologies often rely on a limited number of data points, which may not fully represent the broader global findings (Cetin et al., 2021; Charef and Emmitt, 2021; Ganiyu et al., 2020). Similarly, studies utilizing AI and ML techniques require large datasets to enhance the accuracy and reliability of the results (Lu et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021; Akanbi et al., 2020; Oluleye et al., 2023). Specifically, in the context of end-of-life resource management studies, models should be tested and applied to different types of materials and structures to ensure their robustness and applicability. Similarly, the development and implementation of digital platforms and material banks necessitate the availability of various datasets (Heisel and Rau-Oberhuber, 2020; Kleemann et al., 2017). Consequently, it is crucial to conduct studies in multiple locations and increase the sample sizes to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and potential solutions.

Lastly, automating CE frameworks not only streamlines processes but also enhances accuracy and eliminates manual interventions, leading to improved resource management, reduced waste, and increased overall sustainability in the built environment. However, challenges such as interoperability, data privacy, and technological compatibility need to be addressed to fully realize the potential of automating CE frameworks with IoT and blockchain technologies (Elghaish et al., 2023; Guerra et al., 2020; Hiu Hoong et al., 2020).

4.1.4. Collaboration and Knowledge Management Challenges

The transition towards a CE in the built environment presents several technological challenges, particularly in the areas of collaboration and knowledge management. One key challenge is the lack of transparent data, which hinders the effective sharing and exchange of information among stakeholders. Without access to accurate and up-to-date data on resource consumption, waste generation, and recycling capabilities, it becomes difficult to make informed decisions and develop effective circular strategies (Setaki and van Timmeren, 2022). Additionally, there is a lack of platforms specifically designed to facilitate collaborative efforts and manage knowledge in the context of the CE. Existing platforms often lack the necessary features and functionalities to support collaborative workflows and enable seamless knowledge sharing among different actors in the built environment (Costa et al., 2022; Kovacic et al., 2020). Furthermore, a significant gap exists in the connection between construction, deconstruction plans, and end-of-life resource management strategies (Ge et al., 2017). The absence of integrated systems that link these aspects hampers the efficient and coordinated implementation of circular practices, as there is limited visibility and alignment between the various stages of a building’s life cycle. Addressing these collaboration and knowledge management challenges is crucial to foster effective communication, information sharing, and coordination among stakeholders, enabling a more seamless and integrated transition towards a CE in the built environment.