Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

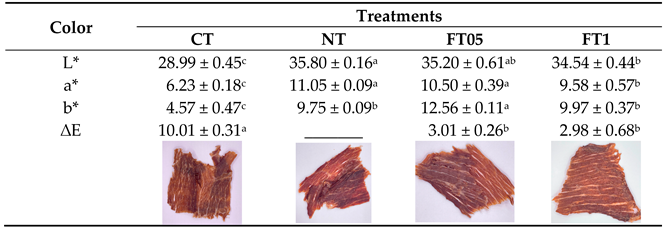

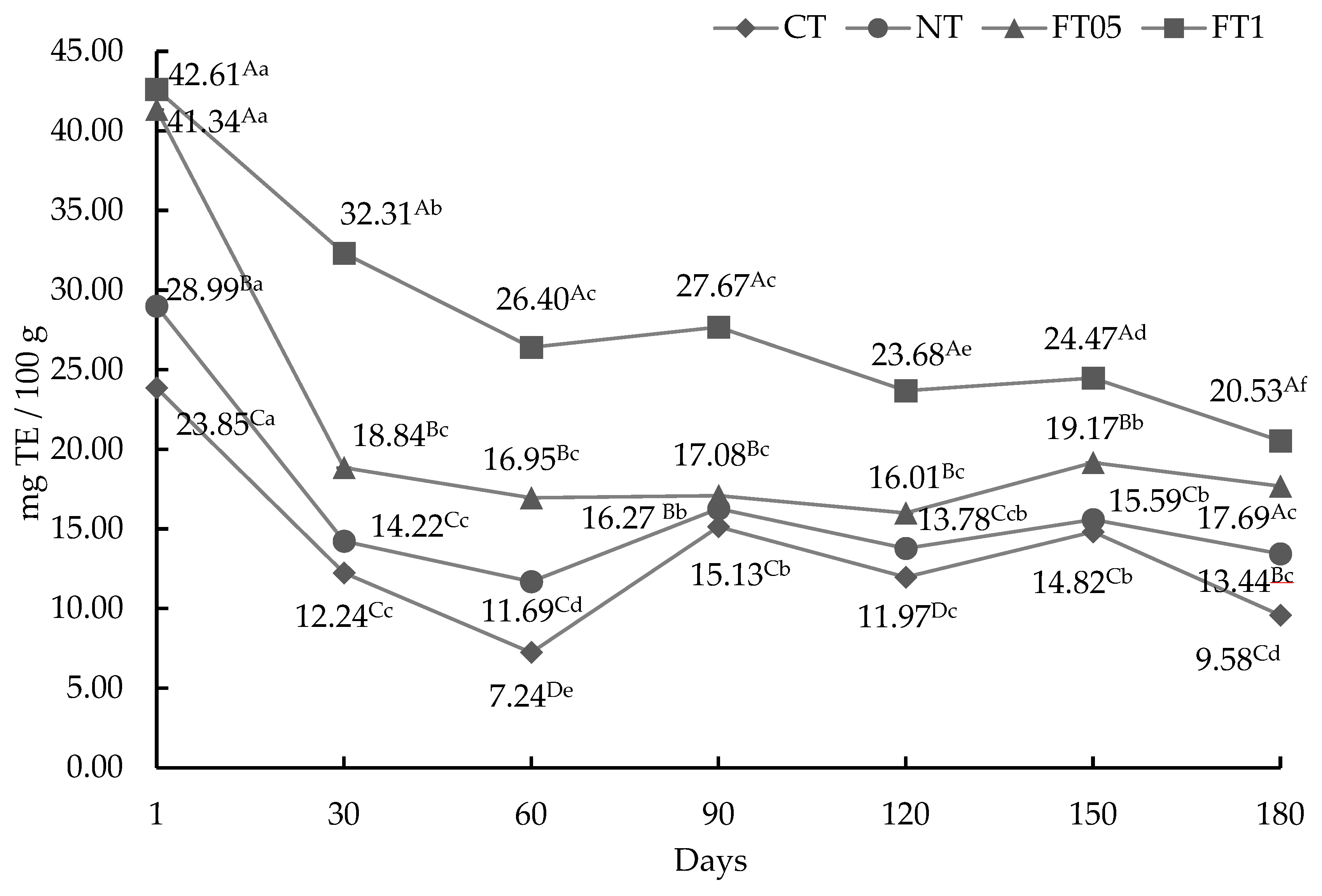

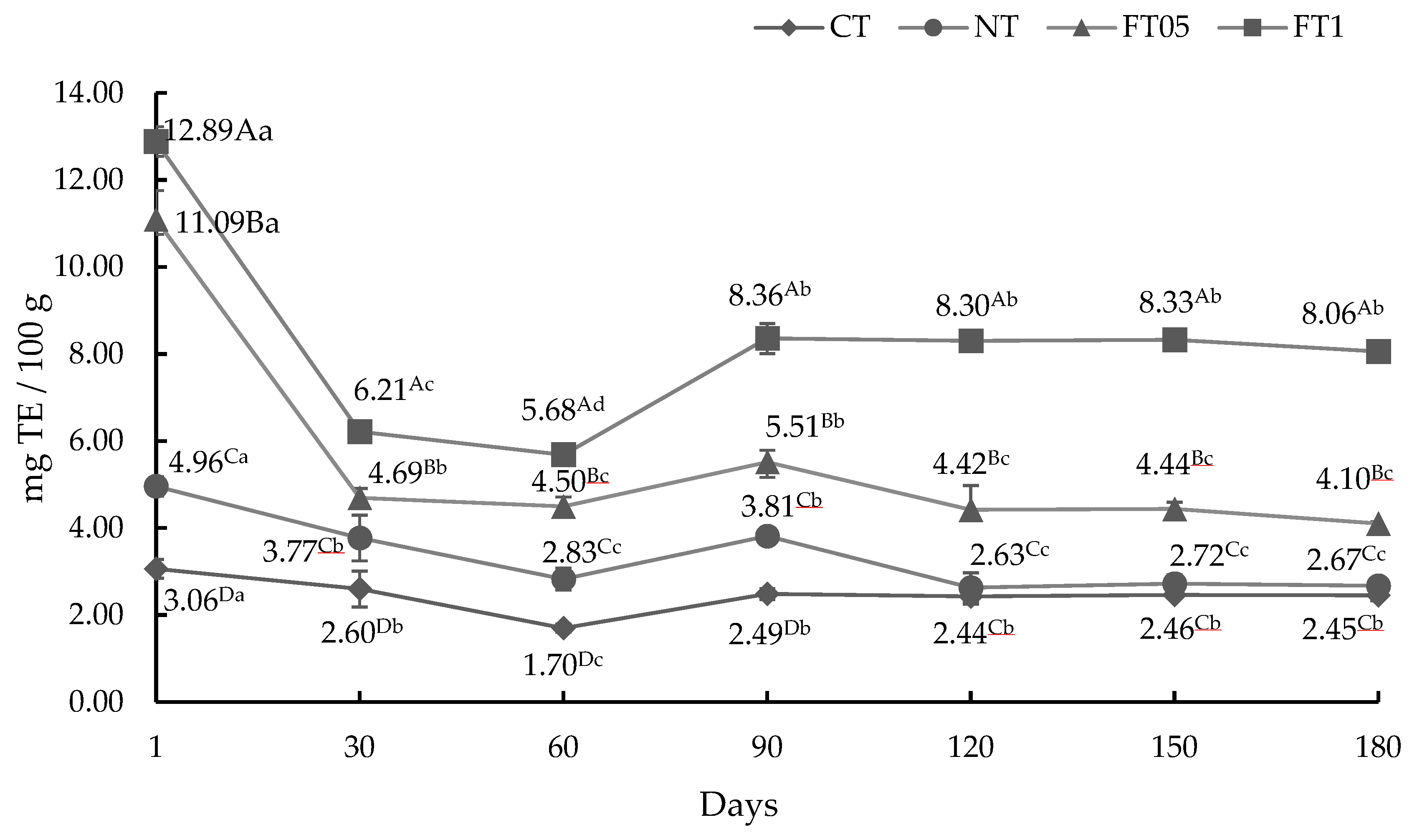

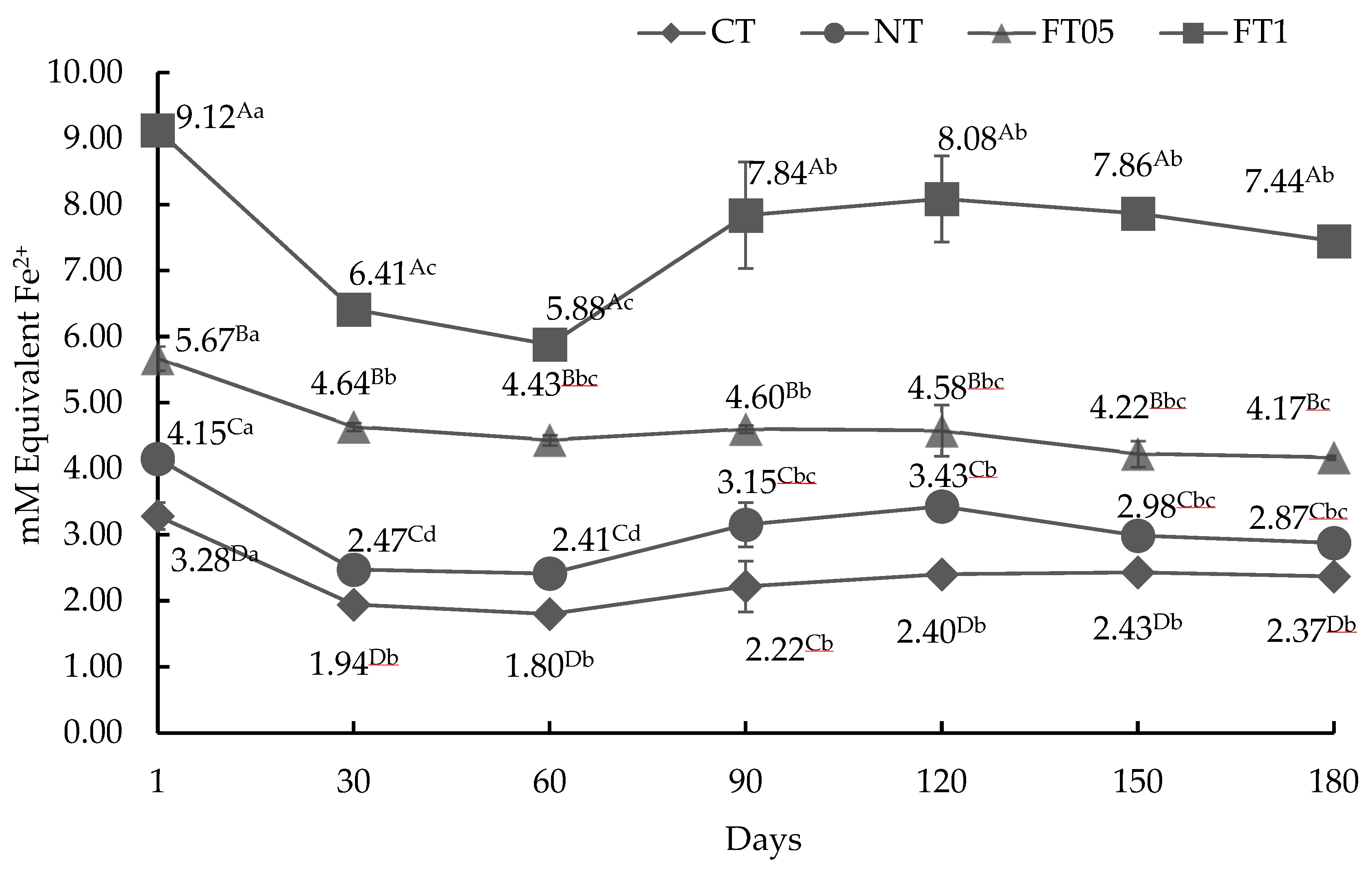

Ferulic acid (FA) is an antimicrobial and antioxidant phenolic compound located in the cell walls of plants and therefore classified as a natural antioxidant. The objective of this study was to assess the antimicrobial and antioxidant potential of FA as a substitute for nitrites in the elaboration of dried meat (DM) . Four treatments were evaluated: DM without nitrites or FA (control treatment; CT), DM with nitrites (NT), DM with 0.05% of FA (FT05), and DM with 0.1% of FA (FT1). The antioxidant activity (ABTS, DPPH, and FRAP), lipid oxidation (TBARS), and microbiological quality were evaluated throughout DM shelf life. Protein, fat, and ash content were not different among NT, FT05, and FT1 (p > 0.05). NT and FT05 had lower moisture content (p < 0.05) compared to CT and FT1. And NT had the highest sodium content (p < 0.05). Regarding color, no differences (p > 0.05) were found among NT and FT05 in L* and a* values, but FT05 presented the highest b* value among all treatments (p < 0.05). However, color differences (ΔE) values between NT and FA treatments indicate that the color change is not noticeable to the human eye. Meanwhile, FT1 and FT05 exhibited the highest (p < 0.05) AA and the lowest lipid oxidation throughout their shelf life. Total aerobic mesophiles counts were detected only on day 1 and were lower (p < 0.05) in the treatments with FA. Finally, the change in the formulation of dried meat by using ferulic acid instead of nitrites was not sensorially detected by panelists. These findings suggest that incorporating natural antioxidants such as FA can improve the oxidative stability of dried meat, and it has a potential application as an antioxidant in meat products. However, further research is needed to study the effect of nitrite substitution using FA in combination with other potential natural antioxidants.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Treatments

2.2. Dried Meat Elaboration

2.3. Physicochemical Composition

2.4. pH

2.5. Sodium Determination

2.7. Color

2.8. Antioxidant Activity (AA)

2.9. Lipid Oxidation

2.10. Microbiological Analysis

2.11. Sensory Evaluation

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Composition and Correlation Between Variables

3.2. Color

|

| Moisture | Ashes | Fat | Protein | L* | a* | b* | Sodium | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 1 | -0.375 | 0.879 | -0.966 | -0.817 | 0.018 | 1.000* | -0.484 |

| p-value | 0.755 | 0.316 | 0.168 | 0.391 | 0.988 | 0.018 | 0.678 | |

| Ashes | 1 | -0.772 | 0.121 | 0.840 | 0.920 | -0.401 | 0.993 | |

| p-value | 0.439 | 0.923 | 0.365 | 0.256 | 0.737 | 0.077 | ||

| Fat | 1 | -0.725 | -0.993 | -0.461 | 0.892 | -0.843 | ||

| p-value | 0.484 | 0.074 | 0.695 | 0.298 | 0.362 | |||

| Protein | 1 | 0.639 | -0.278 | -0.958 | 0.240 | |||

| p-value | 0.558 | 0.821 | 0.186 | 0.846 | ||||

| L | 1 | 0.561 | -0.833 | 0.900 | ||||

| p-value | 0.621 | 0.373 | 0.287 | |||||

| a | 1 | -0.010 | 0.866 | |||||

| p-value | 0.993 | 0.333 | ||||||

| b | 1 | -0.509 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.660 | |||||||

| Sodium | 1 |

| Moisture | Ashes | Fat | Protein | L | a | b | Sodium | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 1 | 1.000** | -1.000** | -1.000** | 1.000** | 1.000** | -0.866 | 0.000 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.333 | 1.000 | |

| Ashes | 1 | -1.000** | -1.000** | 1.000** | 1.000** | -0.866 | 0.000 | |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.333 | 1.000 | ||

| Fat | 1 | 1.000** | -1.000** | -1.000** | 0.869 | 0.007 | ||

| p-value | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.329 | 0.996 | |||

| Protein | 1 | -1.000** | -1.000** | 0.863 | -0.006 | |||

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.337 | 0.996 | ||||

| L | 1 | 1.000** | -0.866 | 0.000 | ||||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.333 | 1.000 | |||||

| a | 1 | -0.866 | 0.000 | |||||

| p-value | 0.333 | 1.000 | ||||||

| b | 1 | 0.500 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.667 | |||||||

| Sodium | 1 |

| Moisture | Ashes | Fat | Protein | L | a | b | Sodium | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 1 | 1.000** | -1.000** | -1.000** | 1.000** | 1.000** | -.866 | .866 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |

| Ashes | 1 | -1.000** | -1.000** | 1.000** | 1.000** | -0.866 | 0.866 | |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.333 | 0.333 | ||

| Fat | 1 | 1.000** | -1.000** | -1.000** | 0.869 | -0.869 | ||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.329 | 0.329 | |||

| Protein | 1 | -1.000** | -1.000** | 0.869 | -0.869 | |||

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.329 | 0.329 | ||||

| L | 1 | 1.000** | -0.866 | 0.866 | ||||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |||||

| a | 1 | -0.866 | 0.866 | |||||

| p-value | 0.333 | 0.333 | ||||||

| b | 1 | -1.000** | ||||||

| p-value | 0.000 | |||||||

| Sodium | 1 |

| Moisture | Ashes | Fat | Protein | L | a | b | Sodium | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 1 | 1.000** | -1.000** | -1.000** | 1.000** | 1.000** | -.866 | .866 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |

| Ashes | 1 | -1.000** | -1.000** | 1.000** | 1.000** | -0.866 | 0.866 | |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.333 | 0.333 | ||

| Fat | 1 | 1.000** | -1.000** | -1.000** | 0.869 | -0.869 | ||

| p-value | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.329 | 0.329 | |||

| Protein | 1 | -1.000** | -1.000** | 0.863 | -0.863 | |||

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.337 | 0.337 | ||||

| L | 1 | 1.000** | -0.866 | 0.866 | ||||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |||||

| a | 1 | -0.866 | 0.866 | |||||

| p-value | 0.333 | 0.333 | ||||||

| b | 1 | -1.000** | ||||||

| p-value | 0.000 | |||||||

| Sodium | 1 |

3.3. Antioxidant Activity (AA)

3.3.1. AA by ABTS Method

3.3.2. AA by DPPH Method

3.3.3. AA by FRAP Method

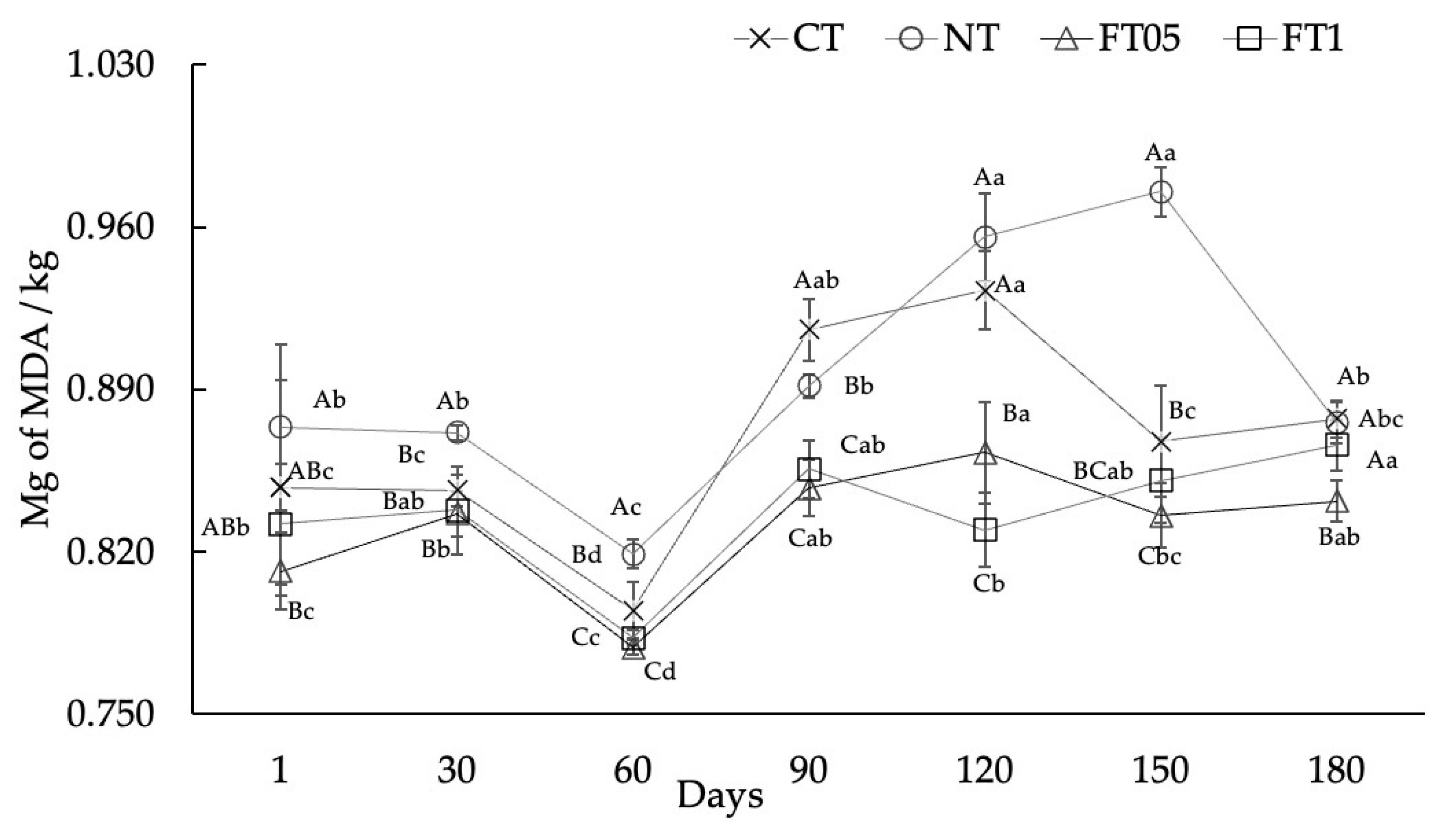

3.4. Lipid Oxidation

3.5. Microbiological Analysis

| Days | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | NT | FT05 | FT1 | |

| 1 | 4.86 ± 0.03a | 4.75 ± 0.17a | 4.3 ± 0.11b | 4.0 ± 0.01b |

| 60 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 180 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

3.6. Sensory Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mediani, A.; Hamezah, H.S.; Jam, F.A.; Mahadi, N.F.; Chan, S.X.Y.; Rohani, E.R.; Che-Lah, N.H.; Azlan, U.K.; Khairul-Annuar, N.A.; Azman, N.A.F.; Bunawan, H.; Sarian, M.N.; Kamal, N.; Abas, F. A comprehensive review of drying meat products and the associated effects and changes. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1057366. [CrossRef]

- Directriz de cumplimiento del FSIS para carne seca y carne seca de aves de corral producida por establecimientos pequeños y muy pequeños. Directriz de cumplimiento de 2014. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Food Safety and Inspection Service. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/guidelines/2014-0010. (accesed on 30 October 2024).

- Echegaray, N.; Pateiro, M.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Chabani, Z.; Farag, M.A.; Domínguez, R. Measurement of antioxidant capacity of meat and meat products: Methods and applications. Molecules 2021, 26(13), 3880. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Cárdenas, L. (2015). Efecto del tiempo de secado y de distintos cortes de músculos de res en las características fisicoquímicas y sensoriales de carne seca (cecina). ACI Avances En Ciencias E Ingenierías, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Gómez, I.; Janardhanan, R.; Ibañez, F.C.; Beriain, M.J. The effects of processing and preservation technologies on meat quality: Sensory and nutritional aspects. Foods 2020, 9(10), 1416. [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M. H., Trisha, A. T., Rahman, M., Talukdar, S., Kobun, R., Huda, N., & Zzaman, W. (2022). Nitrites in cured meats, health risk issues, alternatives to nitrites: a review. Foods, 11(21), 3355. [CrossRef]

- Battaglia Richi, E., Baumer, B., Conrad, B., Darioli, R., Schmid, A., & Keller, U. (2015). Health risks associated with meat consumption: a review of epidemiological studies. International journal for vitamin and nutrition research. Internationale Zeitschrift fur Vitamin- und Ernahrungsforschung. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res, 85(1-2), 70–78. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira-Silva, E.; Batista, R. Ferulic acid and naturally occurring compounds bearing a feruloyl moiety: a review on their structures, occurrence, and potential health benefits. CRFSFS 2017, 16(4), 580-616. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Rui, Y.; Guo, S.; Luan, F.; Liu, R.; Zeng, N. Ferulic acid: A review of its pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and derivatives. Life Sci. 2021, 284, 119921. [CrossRef]

- Zduńska, K.; Dana, A.; Kolodziejczak, A.; Rotsztejn, H. Antioxidant properties of ferulic acid and its possible application. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018, 31(6), 332-336. [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis, 15th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Inc., Virginia, USA, 1990.

- Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-F-150 S-1981. Determinación de cloruro de sodio en salmueras. Alimentos Para Humanos . Available online: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4716889&fecha=15/02/1982#gsc.tab=0 (accesed on 30 October 2024).

- Aportela-Palacios, A.; Sosa-Morales, M.E.; Vélez-Ruiz, J.F. Rheological and physicochemical behavior of fortified yogurt, with fiber and calcium. J. Texture Stud. 2005, 36, 333–349. [CrossRef]

- Thaipong, K.; Boonprakob, U.; Crosby, K.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Hawkins Byrne, D. Comparison of ABTS, DPPH, FRAP, and ORAC assays for estimating antioxidant activity from guava fruit extracts. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19(6–7), 669–675. [CrossRef]

- Pfalzgraf, A.; Frigg, M.; Steinhart, H. Contenido de tocoferol y oxidación lipídica en el músculo y el tejido adiposo del cerdo durante Almacenamiento. J. Agric. 1995, 43, 1339-1342.

- Meilgaard, M.C.; Civille, G.V.; Carr, B.T. Sensory evaluation techniques, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, 2007; https://doi.org/10.1201/b16452.

- Aykin-Dinçer, E.; Atli, B.; Çakmak, Ö.; Canavar, S.; Çalışkan, A. Drying kinetics and quality characteristics of microwave-assisted hot air-dried beef chips. JMPEE 2021, 55(3), 219-235. [CrossRef]

- Zdanowska-Sasiadek, Z.; Marchewka, J.; Horbanczuk, J.O.; Wierzbicka, A.; Lipinska, P.; Józwik, A.; Atanasov, A.G.; Huminiecki, Ł.; Sieron, A.; Sieron, K.; Strzałkowska, N.; Stelmasiak, A.; De Smet, S.; Hecke, T.V.; Hoffman, L.C. Nutrients composition in fit snacks made from ostrich, beef and chicken dried meat. Molecules 2018, 23(6), 1267. [CrossRef]

- Seo, J. K., Eom, J. U., & Yang, H. S. (2023). Comparison between Berkshire and crossbreed on meat quality, and investigation of the relationship with fatty acid composition and meat quality. J Anim Sci Technol, 65(5), 1081–1093. [CrossRef]

- Lim, H. J., Kim, G. D., Jung, E. Y., Seo, H. W., Joo, S. T., Jin, S. K., & Yang, H. S. (2014). Effect of curing time on the physicochemical and sensory properties of beef jerky replaced salt with soy sauce, red pepper paste and soybean paste. J Anim. Sci. (Asian-Australasian), 27(8), 1174–1180. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Zhu, M., Hu, X., Pan, J., & Zhang, G. (2022). Exploring the binding mechanism of ferulic acid and ovalbumin: insights from spectroscopy, molecular docking and dynamics simulation. J. Agric. Food. Sci. 102(9), 3835–3846. [CrossRef]

- Villamil-Galindo, E.; Piagentini, A.M. Uso de nitritos y nitratos en la industria cárnica lo bueno, lo malo, y el modelo matemático para optimizar su uso. Una revisión. Revista de La Asociación Colombiana de Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos (ACTA).

- 2021, 29(56), 41-76.

- Dimakopoulou-Papazoglou, D.; Katsanidis, E. Effect of maltodextrin, sodium chloride, and liquid smoke on the mass transfer kinetics and storage stability of osmotically dehydrated beef meat. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10(11), 2034-2045. [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, D.K.; Bryan, N. S. Sodium nitrite: The “cure” for nitric oxide insufficiency. Meat Science 2012, 92(3), 274-279. [CrossRef]

- Sorroza-Rojas, N.A.; Jinez-Sorroza, B.E.; Grijalva-Endara, A. de las M.; Naranjo-Álvarez, J. de L. El cloruro de sodio (NaCl) y los efectos en la alimentación. Recimundo 2019, 3(1), 913-937. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Navas, J.S.; Rodríguez De Stouvenel, A. Characterization of Colombian quesillo cheese by spectrocolorimetry. Vitae 2012, 19(2), 178-185. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C. N., Orvañanos-Guerrero, M. T., Domínguez-Soberanes, J., & Álvarez-Cisneros, Y. M. (2023). Analysis of beef quality according to color changes using computer vision and white-box machine learning techniques. Heliyon, 9(7), e17976. [CrossRef]

- Bampi, M.; Schmidt, F.C.; Laurindo, J.B. A fast-drying method for the production of salted-and-dried meat. Food Sci. Technol. (Brazil) 2019, 39, 526-534. [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. D., Go, G. W., Lim, H. J., Jung, E. Y., Seo, H. W., Jeong, J. Y., Joo, S. T., & Yang, H. S. (2014). Physicochemical characteristics of beef jerky cured with salted-fermented anchovy and shrimp. Food Sci. Anim. (Korean), 34(1), 99–105. [CrossRef]

- Kruk, O., & Ugnivenko, A. (2024). Relationship between the chemical composition, physical, technological, and sensory properties of beef and the colour of muscle tissue. Anim. Sci. Food Technol, 15(1), 42-54. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Salman, Z.; Kadim, I.T.; Mothershaw, A.; Al-Riziqi, M.H.; Guizani, N.; Mahgoub, O.; Ali, A. Microbial and physico-chemical characteristics of dried meat processed by different methods. Int. J. Food Eng. 2005, 1(2), 3. [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, A.; Karasu, S.; Akcicek, A.; Kayacan, S. Effects of different drying methods on drying kinetics, microstructure, color, and the rehydration ratio of minced meat. Foods 2019, 8(6), 216. [CrossRef]

- Suman, S. P., & Joseph, P. (2013). Myoglobin chemistry and meat color. Annual Review of Food Sci. Technol. 4, 79–99. [CrossRef]

- Sepe HA, Faustman C, Lee S, Tang J, Suman SP, Venkitanarayanan KS. 2005. Effects of reducing agents on premature browning in ground beef. Food chem. 93:571–76. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Ovando, A.; Mejía-Reyes, J.D.; García-Cabrera, K.E.; Velázquez-Ovalle, G. Capacidad antioxidante: conceptos, métodos de cuantificación y su aplicación en la caracterización de frutos tropicales y productos derivados. RCIA 2022, 9(1), 9-33. [CrossRef]

- Ghani, M. A., Barril, C., Bedgood, D. R., Jr, & Prenzler, P. D. (2017). Measurement of antioxidant activity with the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay. Food chemistry, 230, 195–207. [CrossRef]

- Horbańczuk, O. K., Kurek, M. A., Atanasov, A. G., Brnčić, M., & Rimac Brnčić, S. (2019). The effect of natural antioxidants on quality and shelf life of beef and beef products. Food Technol. Biotech, 57(4), 439–447. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Y., Lee, D. Y., Kim, O. Y., Kang, H. J., Kim, H. S., & Hur, S. J. (2020). Overview of studies on the use of natural antioxidative materials in meat products. Food Sci. Anim. Res. 40(6), 863–880. [CrossRef]

- Selani, M. M., Herrero, A. M., & Ruiz-Capillas, C. (2022). Plant antioxidants in dry fermented meat products with a healthier lipid profile. Foods, 11(22), 3558. [CrossRef]

- Bower, C.K., Schilke, K.F. and Daeschel, M.A. (2003), Antimicrobial properties of raisins in beef jerky preservation. J. Food Sci. 68: 1484-1489. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Z.; Xu, W.; Chen, Q.; The antioxidant properties, metabolism, application and mechanism of ferulic acid in medicine, food, cosmetics, livestock and poultry. Antioxidants 2024, 13 (853). [CrossRef]

- Elmas, F.; Bodruk, A.; Köprüalan, Ö.; Arikaya, Ş.; Koca, N.; Serdaroğlu, F.M.; Kaymak-Ertekin, F.; Koç, M. The effect of pre-drying methods on physicochemical, textural and sensory characteristics on puff dried Turkey breast meat. LWT 2021, 145, 111350. [CrossRef]

- Manessis, G.; Kalogianni, A.I.; Lazou, T.; Moschovas, M.; Bossis, I.; Gelasakis, A.I. Plant-derived natural antioxidants in meat and meat products. Antioxidants 2020, 9(12), 1-30. [CrossRef]

- Selani, M.M.; Shirado, G.A.N.; Margiotta, G.B.; Saldaña, E.; Spada, F.P.; Piedade, S.M.S.; Contreras-Castillo, C.J.; Canniatti-Brazaca, S.G. Effects of pineapple byproduct and canola oil as fat replacers on physicochemical and sensory qualities of low-fat beef burger. Meat science 2016, 112, 69-76. [CrossRef]

- Zioud, A.; Hajji, W.; Lobón, S.; Joy, M.; Bertolin, J.R.; Smeti, S.; Chabbouh, M.; Bellagha, S.; Essid, I. Effects of drying methods on chemical composition, lipid oxidation, and fatty acid profile of a traditional dried meat kaddid. Foods 2023, 12(20), 3837. [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.G.; Lee, S.S.; Seo, K.S.; Nam, K.C. Effects of different drying methods on quality traits of hanwoo beef jerky from low-valued cuts during storage. Korean J. Food Sci. An. 2012, 32(5), 531-539. [CrossRef]

- Nereyda, E., & Sauceda, R. Uso de agentes antimicrobianos naturales en la conservación de frutas y hortalizas. Ra Ximbai 2011, 7(1), 153-170. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=46116742014.

- Ijabadeniyi, O.A.; Govender, A.; Olagunju, O.F.; Oyedeji, A.B. The antimicrobial activity of two phenolic acids against foodborne Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes and their effectiveness in a meat system. Italian J. Food Sci. 2021, 33(1), 39-45. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | NT | FT05 | FT1 | |

| Protein | 64.05 ± 3.08a | 64.05 ± 1.63a | 64.84 ± 1.56a | 62.82 ±1.16a |

| Fat | 14.77± 0.51b | 15.77 ± 0.50a | 15.42 ± 0.28ab | 15.75 ± 0.09a |

| Ashes | 13.4 ± 0.9a | 12.38 ± 1.01a | 14.25 ± 1.26a | 14.49 ± 1.26a |

| Moisture | 7.58 ± 0.52a | 5.2 ± 0.30c | 5.24 ± 0.33c | 6.4 ± 0.21b |

| Sodium (mg/100g) | 2715.28 ± 22.11a | 3130.56 ± 25.80b | 2507.64 ± 30.83a | 2539.58 ± 29.25a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).