Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.1.1. Sampling, Preparation and Processing of Samples

| Salt | Acerola extract | Salicornia powder | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | - | - | - |

| Salt | 1% | - | - |

| Salt and Acerola | 1% | 0.3% | - |

| Salic. 1% | - | - | 1% |

| Salic. 2% | - | - | 2% |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | - | 0.3% | 1% |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | - | 0.3% | 2% |

2.1.2. Packaging and Storage of Samples

2.2. Microbial Analysis

2.3. Physical and Chemical Analyses

2.3. Instrumental Colour Measurement

2.4. Sensory Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Microorganisms Quantification

| Microorganism | log ufc/ g sample |

|---|---|

| Total mesophiles | 4.59 ± 0.17 |

| Total psychrotrophs | 4.91 ± 0.17 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 3.69 ± 1.43 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 4.19 ± 0.47 |

| Brochothrix thermosphacta | 3.61 ± 0.32 |

| Lactic acid bacteria | 2.70 ± 0.49 |

| Molds and Yeasts | - |

| Salmonella spp. | - |

| E. coli | - |

| L. monocytogenes | - |

| Time | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 | p | |

| Mesophiles | ||||||

| Control | 5.58 ± 0.43 | 6.70 ± 0.25 | 6.81 ± 0.78 | 7.50 ± 1.29 | 6.70 ± 1.65 | n.s. |

| Salt | 5.48 ± 0.51 | 6.61 ± 0.28 | 6.84 ± 0.95 | 7.44 ± 0.88 | 6.46 ± 2.07 | n.s. |

| Salt and Acerola | 5.58 ± 0.66 | 6.58 ± 0.12 | 6.99 ± 0.64 | 6.96 ± 0.38 | 6.35 ± 1.17 | n.s. |

| Salic. 1% | 6.46 ± 0.05 | 5.85 ± 1.16 | 6.96 ± 0.63 | 6.87 ± 0.02 | 6.66 ± 0.51 | n.s. |

| Salic. 2% | 6.10 ± 0.63 | 6.88 ± 0.43 | 7.36 ± 0.63 | 6.96 ± 0.50 | 6.85 ± 0.73 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 6.47 ± 0.15 | 6.43 ± 0.20 | 7.13 ± 0.46 | 7.01 ± 0.39 | 6.11 ± 0.69 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 6.52 ± 0.07 | 7.00 ± 0.63 | 7.30 ± 0.56 | 7.22 ± 0.40 | 6.98 ± 0.81 | n.s. |

| Psychrotrophs | ||||||

| Control | 5.92 ± 0.68 | 7.12 ± 0.20 | 7.48 ± 0.28 | 7.61 ± 0.63 | 7.88 ± 0.33 | ≤ 0.01 |

| Salt | 5.40 ± 0.67 | 6.99 ± 0.58 | 7.76 ± 0.35 | 7.79 ± 0.56 | 7.97 ± 0.27 | ≤ 0.01 |

| Salt and Acerola | 5.58 ± 0.57 | 6.89 ± 0.65 | 7.49 ± 0.31 | 7.75 ± 0.44 | 7.37 ± 0.16 | ≤ 0.001 |

| Salic. 1% | 5.05 ± 0.52 | 6.88 ± 0.36 | 7.55 ± 0.14 | 7.63 ± 0.90 | 7.86 ± 0.34 | ≤ 0.001 |

| Salic. 2% | 5.30 ± 0.66 | 7.10 ± 0.51 | 7.98 ± 0.05 | 7.75 ± 0.47 | 7.91 ± 0.03 | ≤ 0.001 |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 5.23 ± 0.48 | 7.15 ± 0.93 | 7.93 ± 0.21 | 7.70 ± 0.64 | 8.09 ± 0.04 | ≤ 0.001 |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 5.18 ± 0.59 | 6.67 ± 0.93 | 7.72 ± 0.13 | 7.49 ± 0.22 | 7.47 ± 0.57 | ≤ 0.01 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | ||||||

| Control | 2.81 ± 1.12 | 3.90 ± 0.81 | 4.66 ± 1.63 | 4.87 ± 0.42 | 4.64 ± 0.86 | n.s. |

| Salt | 3.17 ± 0.61 | 4.06 ± 0.66 | 4.64 ± 1.26 | 4.89 ± 0.63 | 4.26 ± 1.30 | n.s. |

| Salt and Acerola | 3.28 ± 0.20 | 4.08 ± 0.14 | 4.71 ± 1.16 | 4.99 ± 0.94 | 4.94 ± 0.36 | n.s. |

| Salic. 1% | 3.28 ± 0.91 | 3.87 ± 0.66 | 4.71 ± 1.54 | 4.71 ± 0.54 | 4.27 ± 1.37 | n.s. |

| Salic. 2% | 2.98 ± 0.53 | 3.72 ± 0.68 | 5.14 ± 1.29 | 4.66 ± 0.56 | 4.19 ± 1.43 | ≤ 0.05 |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 3.39 ± 0.55 | 4.60 ± 1.37 | 4.52 ± 0.35 | 6.18 ± 1.22 | 5.14 ± 0.13 | ≤ 0.05 |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 3.10 ± 0.35 | 4.10 ± 0.25 | 4.95 ± 0.83 | 5.08 ± 0.78 | 4.73 ± 1.24 | ≤ 0.05 |

| LAB | ||||||

| Control | 3.27 ± 0.31 | 4.46 ± 0.98 | 5.96 ± 0.85 | 7.10 ± 1.16 | 4.89 ± 0.28 | ≤ 0.01 |

| Salt | 3.59 ± 1.86 | 4.20 ± 0.46 | 6.05 ± 1.13 | 7.50 ± 1.32 | 4.93 ± 0.16 | ≤ 0.01 |

| Salt and Acerola | 3.37 ± 0.54 | 4.56 ± 0.72 | 6.21 ± 0.90 | 7.05 ± 0.98 | 4.52 ± 0.12 | ≤ 0.05 |

| Salic. 1% | 3.21 ± 0.62 | 4.58 ± 0.47 | 6.18 ± 1.05 | 6.83 ± 0.83 | 5.11 ± 0.66 | ≤ 0.01 |

| Salic. 2% | 3.02 ± 0.33 | 3.91 ± 0.37 | 6.10 ± 0.81 | 6.45 ± 0.95 | 5.06 ± 0.24 | ≤ 0.01 |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 4.13 ± 1.93 | 3.97 ± 0.66 | 5.59 ± 0.88 | 6.93 ± 0.91 | 5.16 ± 0.55 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 4.03 ± 1.89 | 4.40 ± 0.62 | 5.52 ± 0.60 | 6.71 ± 0.17 | 6.29 ± 1.37 | n.s. |

| B. thermosphacta | ||||||

| Control | 3.55 ± 0.87 | 5.81 ± 0.14 | 5.84 ± 0.91 | 5.56 ± 1.02 | 5.83 ± 1.30 | ≤ 0.05 |

| Salt | 3.74 ± 0.73 | 5.29 ± 0.43 | 5.79 ± 1.26 | 6.38 ± 0.91 | 5.18 ± 2.65 | n.s. |

| Salt and Acerola | 3.95 ± 0.85 | 5.32 ± 0.53 | 5.71 ± 0.83 | 5.67 ± 0.74 | 5.29 ± 1.31 | n.s. |

| Salic. 1% | 3.95 ± 0.74 | 5.35 ± 0.10 | 5.45 ± 1.26 | 5.13 ± 0.89 | 4.93 ± 1.74 | n.s. |

| Salic. 2% | 3.73 ± 1.22 | 4.91 ± 0.53 | 6.20 ± 1.65 | 4.68 ± 1.65 | 4.75 ± 2.48 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 3.25 ± 0.70 | 4.93 ± 0.44 | 5.07 ± 1.52 | 4.35 ± 1.85 | 4.85 ± 0.61 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 3.50 ± 0.58 | 4.92 ± 0.23 | 5.77 ± 1.22 | 5.36 ± 0.83 | 4.66 ± 2.34 | n.s. |

| Molds and Yeasts | ||||||

| Control | 2.60 ± 0.52 | 2.89 ± 0.77 | 3.50 ± 0.74 | 3.84 ± 0.08 | 3.89 ± 0.36 | n.s. |

| Salt | 2.90 ± 0.26 | 3.00 ± 0.35 | 3.45 ± 0.40 | 3.79 ± 0.38 | 3.39 ± 0.23 | n.s. |

| Salt and Acerola | 2.68 ± 0.14 | 3.07 ± 0.22 | 3.32 ± 0.34 | 3.50 ± 1.11 | 3.19 ± 1.01 | n.s. |

| Salic. 1% | 2.85 ± 0.24 | 3.34 ± 0.39 | 3.09 ± 0.36 | 3.13 ± 0.98 | 3.57 ± 0.74 | n.s. |

| Salic. 2% | 2.59 ± 0.03 | 2.63 ± 0.57 | 3.31 ± 0.62 | 3.25 ± 0.51 | 3.44 ± 0.41 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 3.05 ± 0.36 | 3.00 ± 0.18 | 2.97 ± 0.25 | 3.56 ± 0.32 | 3.76 ± 0.97 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 3.19 ± 0.81 | 2.97 ± 0.36 | 3.69 ± 0.44 | 3.44 ± 0.69 | 3.20 ± 0.59 | n.s. |

| Pseudomonasspp. | ||||||

| Control | 3.66 ± 0.42 | 4.43 ± 0.32 | 4.53 ± 0.52 | 4.91 ± 0.41 | 4.49 ± 0.70 | n.s. |

| Salt | 4.13 ± 0.96 | 4.38 ± 0.17 | 4.41 ± 0.74 | 5.19 ± 0.66 | 4.86 ± 0.61 | n.s. |

| Salt and Acerola | 3.84 ± 0.57 | 4.14 ± 0.17 | 4.41 ± 0.45 | 4.86 ± 0.93 | 4.11 ± 0.16 | n.s. |

| Salic. 1% | 3.84 ± 0.38 | 3.78 ± 0.20 | 4.76 ± 0.52 | 4.71 ± 0.58 | 4.30 ± 0.43 | n.s. |

| Salic. 2% | 3.32 ± 0.24 | 4.08 ± 0.18 | 4.37 ± 0.60 | 4.43 ± 0.37 | 4.55 ± 1.21 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 3.69 ± 0.41 | 3.95 ± 0.21 | 4.31 ± 0.67 | 4.91 ± 0.54 | 5.00 ± 0.06 | ≤ 0.05 |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 4.46 ± 0.93 | 4.10 ± 0.34 | 4.82 ± 0.78 | 4.76 ± 0.72 | 4.24 ± 0.34 | n.s. |

3.2. Physical-Chemical Parameters

| Time | ||||||

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 | p | |

| pH | ||||||

| Control | 5.77 ± 0.19 | 5.74 ± 0.26 | 5.78 ± 0.14 | 5.69 ± 0.26 | 5.64 ± 0.23 | n.s. |

| Salt | 5.66 ± 0.14 | 5.59 ± 0.08 | 5.54 ± 0.04 | 5.49 ± 0.03 | 5.44 ± 0.15 | n.s. |

| Salt and Acerola | 5.69 ± 0.18 | 5.67 ± 0.11 | 5.62 ± 0.13 | 5.66 ± 0.16 | 5.50 ± 0.13 | n.s. |

| Salic. 1% | 5.65 ± 0.15 | 5.53 ± 0.12 | 5.50 ± 0.08 | 5.39 ± 0.07 | 5.34 ± 0.15 | n.s. |

| Salic. 2% | 5.62 ± 0.20 | 5.58 ± 0.21 | 5.42 ± 0.18 | 5.38 ± 0.13 | 5.25 ± 0.01 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 5.70 ± 0.19 | 5.62 ± 0.17 | 5.52 ± 0.10 | 5.49 ± 0.10 | 5.62 ± 0.26 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 5.70 ± 0.18 | 5.70 ± 0.25 | 5.60 ± 0.13 | 5.59 ± 0.20 | 5.51 ± 0.19 | n.s. |

| p | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| aw | ||||||

| Control | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 4.00 ± 5.19 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | n.s. |

| Salt | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.00 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | n.s. |

| Salt and Acerola | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.00 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | n.s. |

| Salic. 1% | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | n.s. |

| Salic. 2% | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.00 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.00 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.00 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.00 | 0.98 ± 0.00 | 0.98 ± 0.00 | 0.98 ± 0.00 | n.s. |

| p | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| L* | ||||||

| Control | 39.03 ± 0.96 a | 44.38 ± 2.58 a | 41.04 ± 0.43 a | 41.79 ± 1.36 a | 41.16 ± 2.32 | ≤ 0.05 |

| Salt | 37.04 ± 1.85 ab | 40.08 ± 0.59 ab | 40.25 ± 0.70 ab | 38.99 ± 1.72 ab | 41.30 ± 3.17 | n.s. |

| Salt and Acerola | 38.40 ± 2.43 a | 39.06 ± 2.94 ab | 37.62 ± 2.27 abc | 38.70 ± 1.32 abc | 40.33 ± 1.54 | n.s. |

| Salic. 1% | 33.85 ± 0.68 bc | 37.66 ± 0.77 b | 37.86 ± 0.61 abc | 38.06 ± 0.70 bc | 39.92 ± 0.54 | ≤ 0.001 |

| Salic. 2% | 33.61 ± 0.91 bc | 37.67 ± 3.99 b | 37.46 ± 1.73 bc | 36.90 ± 1.30 bc | 37.12 ± 0.90 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 36.13 ± 2.28 abc | 37.66 ± 1.49 b | 38.81 ± 1.31 ab | 38.99 ± 0.74 ab | 37.67 ± 0.40 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 32.61 ± 0.61 c | 36.67 ± 2.47 b | 34.54 ± 0.66 c | 35.53 ± 1.22 c | 37.05 ± 1.92 | ≤ 0.05 |

| p | ≤ 0.001 | ≤ 0.05 | ≤ 0.001 | ≤ 0.001 | ≤ 0.05 | |

| a* | ||||||

| Control | 21.86 ± 0.84 a | 23.30 ± 3.99 | 21.17 ± 2.48 a | 21.38 ± 1.51 a | 16.75 ± 0.60 | ≤ 0.05 |

| Salt | 19.56 ± 0.77 ab | 21.46 ± 0.71 | 22.35 ± 1.35 a | 20.97 ± 1.70 ab | 18.22 ± 1.53 | ≤ 0.05 |

| Salt and Acerola | 18.85 ± 0.25 ab | 22.22 ± 1.59 | 19.45 ± 1.82 ab | 18.78 ± 0.92 abc | 16.07 ± 3.23 | ≤ 0.05 |

| Salic. 1% | 17.63 ± 1.96 b | 16.23 ± 4.10 | 17.37 ± 0.77 ab | 17.61 ± 0.18 bc | 15.18 ± 3.85 | n.s. |

| Salic. 2% | 14.43 ± 1.62 cd | 15.23 ± 2.77 | 17.00 ± 5.35 ab | 14.01 ± 1.23 de | 12.96 ± 2.49 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 16.53 ± 0.31 bc | 15.57 ± 2.53 | 17.00 ± 0.44 ab | 16.69 ± 1.47 cd | 15.96 ± 3.76 | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 12.85 ± 1.01 d | 17.27 ± 5.52 | 14.05 ± 1.82 b | 12.60 ± 0.75 e | 12.55 ± 1.99 | n.s. |

| p | ≤ 0.001 | ≤ 0.05 | ≤ 0.05 | ≤ 0.001 | n.s. | |

| b* | ||||||

| Control | 12.51 ± 0.95 | 11.96 ± 1.18 | 12.27 ± 1.55 | 11.28 ± 2.69 | 8.17 ± 2.92 b | n.s. |

| Salt | 11.05 ± 0.72 | 12.71 ± 1.01 | 13.36 ± 0.41 | 12.23 ± 0.93 | 11.51 ± 0.40 ab | ≤ 0.05 |

| Salt and Acerola | 10.99 ± 1.41 | 12.68 ± 1.21 | 11.46 ± 1.25 | 10.82 ± 1.23 | 8.87 ± 1.30 ab | n.s. |

| Salic. 1% | 12.76 ± 0.95 | 12.84 ± 1.30 | 12.58 ± 0.66 | 12.41 ± 0.74 | 11.79 ± 0.11 a | n.s. |

| Salic. 2% | 12.16 ± 0.20 | 12.14 ± 2.06 | 12.95 ± 1.46 | 11.80 ± 0.66 | 11.02 ± 0.40 ab | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 1% | 12.99 ± 0.77 | 12.34 ± 0.27 | 12.75 ± 0.40 | 11.83 ± 1.96 | 10.51 ± 0.86 ab | n.s. |

| Acerola and Salic. 2% | 11.40 ± 0.57 | 13.42 ± 1.46 | 11.99 ± 0.62 | 11.29 ± 0.71 | 10.32 ± 0.67 ab | ≤ 0.05 |

| p | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ≤ 0.05 | |

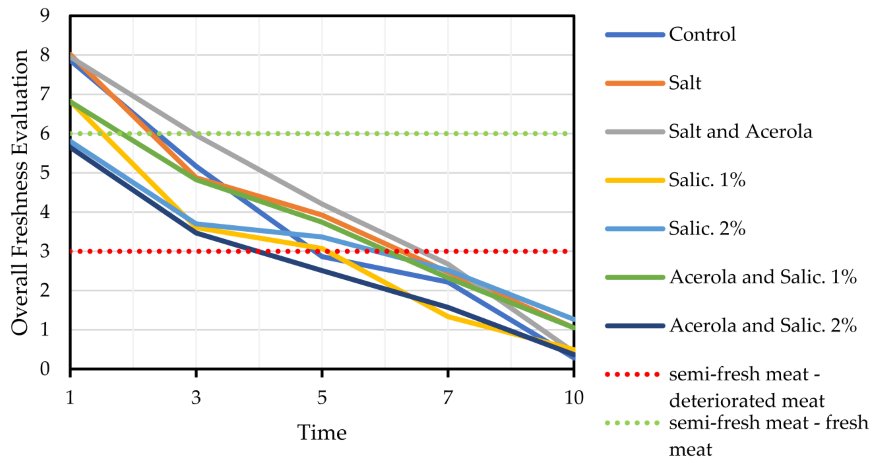

3.3. Sensory Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DOP | Protected Designation of Origin |

| LAB | Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| CIE | Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage |

| OFE | Overall Freshness Evaluation |

References

- Official Journal of the European Union Commission Regulation (EU) No 601/2014 of 4 June 2014 Amending Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards the Food Categories of Meat and the Use of Certain Food Additives in Meat Preparations; Brussels, 2014.

- González, N.; Marquès, M.; Nadal, M.; Domingo, J.L. Meat Consumption: Which Are the Current Global Risks? A Review of Recent (2010–2020) Evidences. Food Research International 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, R.; Hassan, M.M.; Cheng, Z.; Mills, J.; Hou, C.; Realini, C.E.; Chen, L.; Day, L.; Zheng, X.; et al. Active Packaging for the Extended Shelf-Life of Meat: Perspectives from Consumption Habits, Market Requirements and Packaging Practices in China and New Zealand. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoelscher, H.; Fell, E.L.; Colet, R.; Nascimento, L.H.; Backes, Â.S.; Backes, G.T.; Cansian, R.L.; Valduga, E.; Steffens, C. Antioxidant Activity of Rosemary Extract, Acerola Extract and a Mixture of Tocopherols in Sausage during Storage at 8 °C. J Food Sci Technol 2024, 61, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability Labels on Food Products: Consumer Motivation, Understanding and Use. Food Policy 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Guideline: Sodium Intake for Adults and Children; Geneva, 2012.

- United Nations General Assembly; Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; New York, 2015.

- Realini, C.E.; Guàrdia, M.D.; Díaz, I.; García-Regueiro, J.A.; Arnau, J. Effects of Acerola Fruit Extract on Sensory and Shelf-Life of Salted Beef Patties from Grinds Differing in Fatty Acid Composition. Meat Sci 2014, 99, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paiva, G.B.; Trindade, M.A.; Romero, J.T.; da Silva-Barretto, A.C. Antioxidant Effect of Acerola Fruit Powder, Rosemary and Licorice Extract in Caiman Meat Nuggets Containing Mechanically Separated Caiman Meat. Meat Sci 2021, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchopárová, M.; Janoud, Š.; Rydlova, L.; Beňo, F.; Pohůnek, V.; Ševčík, R. Effect of Acerola (Malpighia Emarginata DC.) Fruit Extract on the Quality of Soft Salami. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Mi, L.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Xu, Z. Integration of Untargeted Metabolomics and Object-Oriented Data-Processing Protocols to Characterize Acerola Powder Composition as Functional Food Ingredient. Antioxidants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, Ł.; Porębska, I.; Świder, O.; Sokołowska, B.; Szczepańska-Stolarczyk, J.; Lendzion, K.; Marszałek, K. The Impact of Plant Additives on the Quality and Safety of Ostrich Meat Sausages. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.; Cavaleiro, C.; Ramos, F. Sodium Reduction in Bread: A Role for Glasswort (Salicornia Ramosissima J. Woods). Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2017, 16, 1056–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájar, A.M.; Romero-Bernal, M.; del Río, C.; Montaner, J. A Review on Polyphenols in Salicornia Ramosissima with Special Emphasis on Their Beneficial Effects on Brain Ischemia. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, M.; Roque, M.J.; Cavaleiro, C.; Ramos, F. Nutrient Value of Salicornia Ramosissima—A Green Extraction Process for Mineral Analysis. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2021, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limongelli, F.; Crupi, P.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Corbo, F.; Muraglia, M. Overview of the Polyphenols in Salicornia: From Recovery to Health-Promoting Effect. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, I.; Leite, A.; Vasconcelos, L.; Rodrigues, S.; Mateo, J.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Teixeira, A. Sodium Reduction in Traditional Dry-Cured Pork Belly Using Glasswort Powder (Salicornia Herbacea) as a Partial NaCl Replacer. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carne Mertolenga Denominação de Origem Protegida - Caderno de Especificações.

- European Commission; Commission Staff Working Document: Evaluation of Geographical Indications and Traditional Specialities Guaranteed Protected in the EU; SWD(2021) 427 final; Brussels, 2021.

- Bourafai-Aziez, A.; Jacob, D.; Charpentier, G.; Cassin, E.; Rousselot, G.; Moing, A.; Deborde, C. Development, Validation, and Use of 1H-NMR Spectroscopy for Evaluating the Quality of Acerola-Based Food Supplements and Quantifying Ascorbic Acid. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olędzki, R.; Harasym, J. Acerola (Malpighia Emarginata) Anti-Inflammatory Activity—A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezadri, T.; Villaño, D.; Fernández-Pachón, M.S.; García-Parrilla, M.C.; Troncoso, A.M. Antioxidant Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Acerola (Malpighia Emarginata DC.) Fruits and Derivatives. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2008, 21, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuffs, S.W.; Herfst, C.A.; Baroja, M.L.; Podskalniy, V.A.; DeJong, E.N.; Coleman, C.E.M.; McCormick, J.K. Regulation of Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin-1 by the Accessory Gene Regulator in Staphylococcus Aureus Is Mediated by the Repressor of Toxins. Mol Microbiol 2019, 112, 1163–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nychas, G.J.E.; Skandamis, P.N.; Tassou, C.C.; Koutsoumanis, K.P. Meat Spoilage during Distribution. Meat Sci 2008, 78, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Spoilage Microorganisms; Blackburn, C. de W., Ed.; 1st ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 2006.

- Holley, R.A. Brochothrix. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 331–334.

- Limbo, S.; Torri, L.; Sinelli, N.; Franzetti, L.; Casiraghi, E. Evaluation and Predictive Modeling of Shelf Life of Minced Beef Stored in High-Oxygen Modified Atmosphere Packaging at Different Temperatures. Meat Sci 2010, 84, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremonte, P.; Sorrentino, E.; Succi, M.; Tipaldi, L.; Pannella, G.; Ibañez, E.; Mendiola, J.A.; Di Renzo, T.; Reale, A.; Coppola, R. Antimicrobial Effect of Malpighia Punicifolia and Extension of Water Buffalo Steak Shelf-Life. J Food Sci 2016, 81, M97–M105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leygonie, C.; Britz, T.J.; Hoffman, L.C. Impact of Freezing and Thawing on the Quality of Meat: Review. Meat Sci 2012, 91, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waimin, J.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Heredia-Rivera, U.; Kerr, N.A.; Nejati, S.; Gallina, N.L.F.; Bhunia, A.K.; Rahimi, R. Low-Cost Nonreversible Electronic-Free Wireless PH Sensor for Spoilage Detection in Packaged Meat Products. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2022, 14, 45752–45764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husin, N.; Zulkhairi, M.; Rahim, A.; Azizan, M.; Noor, M.; Fitry, I.; Rashedi, M.; Hassan, N. Real-Time Monitoring of Food Freshness Using Delphinidin-Based Visual Indicator. Malaysian Journal of Analytical Sciences 2020, 24, 558–569. [Google Scholar]

- Alves da Paz, M.E.; de Barcelos, S.C.; Cals de Oliveira, V.; Pinto, M.B.; Alves Teixeira Sá, D.M. Impact of Adding Dehydrated Acerola (Malpighia Emarginata DC) on the Microbiological, Colorimetric, and Sensory Characteristics of Acerola Ice Cream. Int J Gastron Food Sci 2025, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Activity in Foods; Barbosa-Cánovas, G. V., Fontana, A.J., Schmidt, S.J., Labuza, T.P., Eds.; Wiley, 2007; ISBN 9780813824086.

- Li, X.; Lindahl, G.; Zamaratskaia, G.; Lundström, K. Influence of Vacuum Skin Packaging on Color Stability of Beef Longissimus Lumborum Compared with Vacuum and High-Oxygen Modified Atmosphere Packaging. Meat Sci 2012, 92, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Salueña, B.; Sáenz Gamasa, C.; Diñeiro Rubial, J.M.; Alberdi Odriozola, C. CIELAB Color Paths during Meat Shelf Life. Meat Sci 2019, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).