1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Context

The Internet of Things (IoT) has emerged as a transformative force across various domains, including healthcare, agriculture, manufacturing and education. IoT refers to a network of interconnected devices embedded with sensors and software that facilitate data collection and sharing. In education, IoT enables the creation of smart environments where data from learners and their surroundings can be leveraged to enhance teaching and learning processes [

1,

2,

3].

Personalized Online Learning (POL) represents a paradigm shift from traditional education models by tailoring content, pace and methods to individual learners’ needs. POL has gained prominence in addressing the diverse requirements of learners in digital environments. However, its effectiveness heavily depends on the systems’ ability to adapt to real-time changes in learner behavior and context. IoT, with its capacity for real-time data collection and contextual awareness, has become a key enabler of advanced POL systems [

4,

5].

IoT-driven POL systems utilize technologies such as wearable sensors, environmental monitors and edge devices to gather data on learners’ physiological states, engagement levels and learning preferences. This data feeds adaptive learning algorithms that dynamically adjust instructional content, fostering better engagement, improved outcomes and a more inclusive learning experience [

6,

7].

The integration of IoT into POL leverages advanced technological and pedagogical methods to enhance educational experiences. These approaches include IoT-ready platforms like the MaTHiSiS project, which capture learners’ affective states through devices such as smartphones and robots, enabling non-linear and personalized learning paths using “learning atoms” and “learning graphs” and implement serious games [

8]. Big data analysis and decision support systems are applied in IoT-enabled environments to tailor college English learning experiences through algorithms like Adaptive Resonance Theory eXponential Smoothing for real-time customization based on student profiles [

9]. Machine learning techniques, such as Singular Value Decomposition and collaborative filtering, are utilized in smart education systems for personalized course recommendations based on academic performance [

10]. IoT-based systems, such as those using Raspberry Pi, offer personalized content recommendations, fostering engagement and efficiency [

2]. Additionally, IoT integration with generative AI enables dynamic adaptation in real-time, as seen in English language education for personalized oral assessments [

11]. Scalable IoT networks emphasize adaptive sensing, virtualization, fog computing, and user-centric networking to enhance personalized services [

12]. During pandemics, IoT and AI enabled sustainable education through real-time feedback and automatic grading [

13]. Learning analytics integrated with IoT and chatbots provide real-time monitoring and interventions, bridging gaps in current educational systems [

14]. IoT in personal learning environments connects physical and virtual activities, enhancing inclusivity and self-determination [

15]. The Ambient and Pervasive Personalized Learning Ecosystem (APPLE) framework leverages IoT for scalable, learner-centered ecosystems while addressing challenges like interoperability and ethical considerations [

16]. IoT tools, such as smartwatches and fitness bands, are employed in STEM education to measure experimental parameters, enhancing learning personalization [

17]. These approaches collectively illustrate the transformative potential of IoT in creating adaptive, efficient, and inclusive POL systems, grounded in both technological innovations and pedagogical strategies.

1.2. Research Motivation and Objectives

The increasing adoption of IoT across various domains offers a unique opportunity to transform POL by leveraging real-time data analytics and sensor technology to develop adaptive, context-aware learning environments. Despite the promising advancements, the adoption of IoT in educational settings brings different challenges related to technical integration, resource constrains, data processing, security and privacy and system interoperability. These challenges prevent the full realization of IoT-enabled POL systems that are capable of truly personalized education delivery.

A study conducted by Betts et. al. (2022) leverages IoT to create learner-centered environments, emphasizing data collection, interoperability, and ethical considerations. While not systematic, this discussion offers a foundation for future reviews by highlighting critical implementation factors [

16]. A literature review conducted by Razzaque & Hamdan (2020) focuses on aligning IoT technologies with learning outcomes (LOs) and learning styles (LS) in higher education, proposing an interdisciplinary model to improve curriculum design and e-learning experiences, addressing shortcomings in traditional teaching methods [

18]. The thematic literature review conducted by Vinaya & Prasad (2020) emphasizes IoT’s transformative impact on POL by enabling customized educational experiences and real-time student monitoring [

19].

Despite its potential, IoT integration in POL is still in its early stages. Educational institutions face challenges in implementing IoT due to technical, ethical and financial constraints. Furthermore, existing literature often addresses specific IoT applications without presenting a comprehensive overview of the techniques and their broader implications for POL systems. This creates a need for a systematic review to consolidate knowledge and identify opportunities for further exploration. By conducting a systematic review of existing literature and technological applications, this study aims to identify and analyze the effective strategies and significant gaps in the current IoT technological and pedagogical integration approaches. This research is driven by the goal to advance our understanding of IoT’s role in education, facilitating the development of more effective, scalable, and learner-centered educational technologies.

The objectives of this research are multi-faceted and aim to systematically evaluate the current landscape of IoT integration in POL systems. Specifically, the study seeks to:

Systematically categorize the existing IoT technological approaches, models and methodologies employed in POL, and analyze their impact on learning personalization, engagement and learning outcome.

Assess the effectiveness of utilized pedagogical approaches in IoT based POL systems in enhancing learner engagement and educational outcomes.

Provide actionable recommendations for educators, technologists, and policymakers to improve the integration of IoT technologies in personalized learning environments.

By achieving these objectives, the research intends to provide a comprehensive overview of the IoT’s potential to transform POL, ensuring it is adaptive, inclusive, and effective across diverse educational contexts.

This review systematically examines peer-reviewed literature on IoT integration in POL, focusing on works published within the seven years. It incorporates studies that explore the intersection of IoT and POL, excluding those addressing these areas in isolation. The review methodology follows established protocol to ensure objective and reproductive results, including comprehensive database searches, predefined inclusion criteria and detailed data analysis and synthesis.

The potential contributions of this review are multifaceted:

Providing a consolidated framework of IoT technological and pedagogical approaches implemented in IoT based POL systems, guiding future research directions.

Offering educators and practitioners insights into practical and effective IoT integration strategies to enhance learner outcomes.

Informing policymakers about the technological pedagogical, ethical and logistical considerations for scaling IoT in educational contexts.

Develop a framework to integrate IoT in POL by taking in consideration main research gaps identified by this systematic review.

Through these contributions, this review seeks to bridge the knowledge gap in IoT-driven personalization of online learning and foster the development of robust, scalable and ethical educational frameworks.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 focuses on the systematic review research methodology.

Section 3 represent the results of the study by identifying technological and pedagogical approaches utilized in POL systems and providing some benefits of implementing these approaches.

Section 4 discuss about main finding and limitations. Finally,

Section 5 presents conclusions and future directions, highlighting opportunities for further research and advancements in this domain. After this study based on literature review, now we are trying to present the methodology of our research.

2. Methodology

The objective of this study is to identify what technological and pedagogical approaches in IoT based POL systems, identify research gaps and propose a general solution framework for identified main gaps. Its original focus is on the intersection between IoT integration techniques and pedagogical approaches used to implement in these approaches. To achieve a complete overview of the area, we comprehensively review IoT in Education papers that address POL methods, techniques and frameworks.

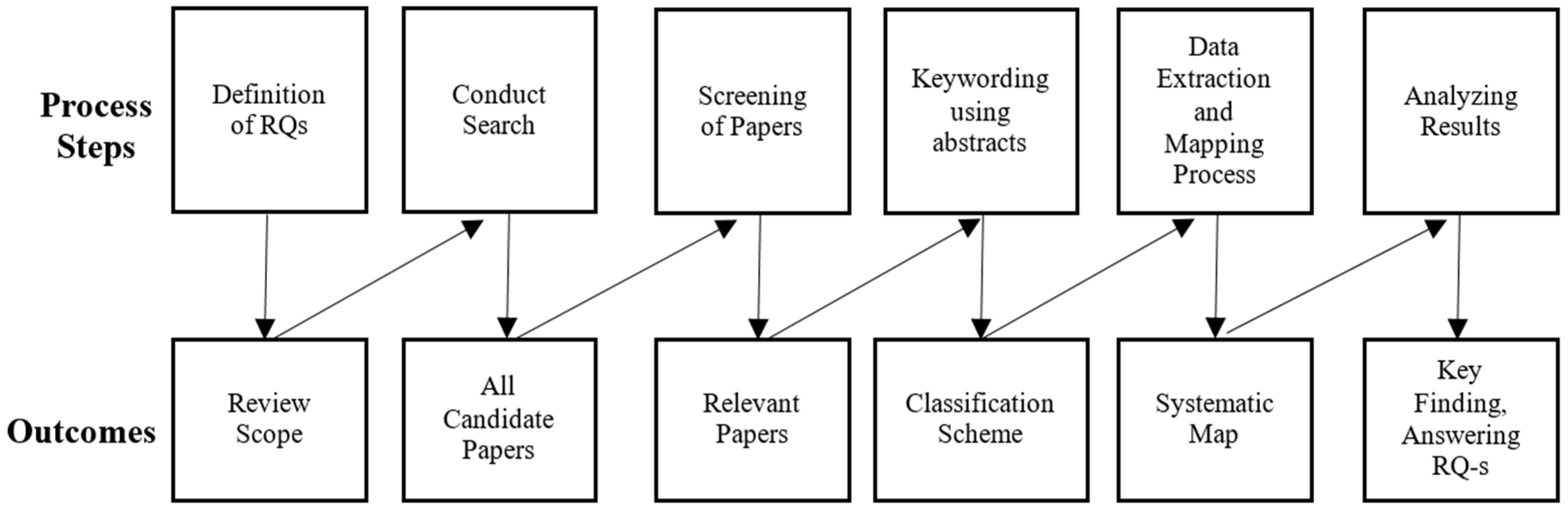

2.1. Systematic Mapping Study

There are different systematic review study guidelines that can be implemented to conduct the systematic review; [

20,

21,

22], however, selected systematic mapping guidelines [

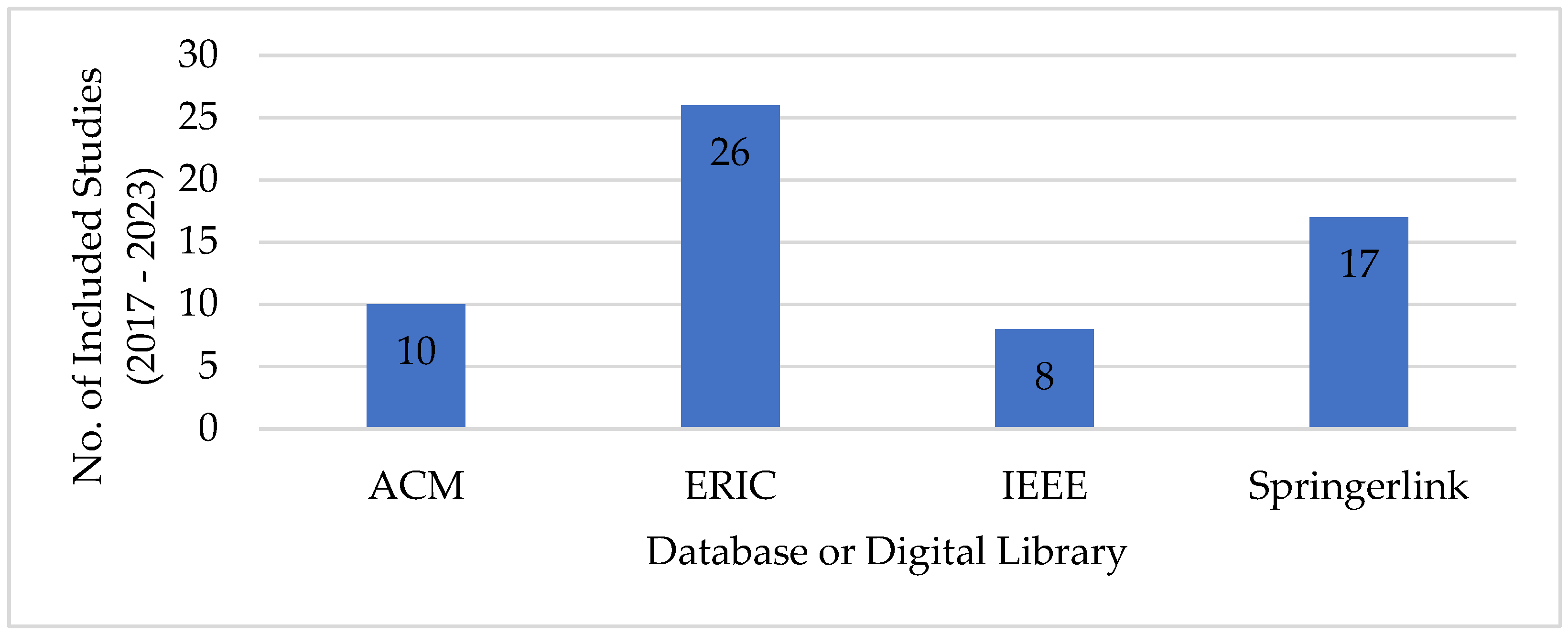

23] consolidated the best practices suggested by other researchers. According to Petersen et al. (2015) a systematic mapping review process begins by formulating research questions (RQs). The next steps involve screening the papers based on their title, abstract, and keyword metadata and then to the full content to answer the RQs. The systematic mapping process conducted in this study is represented in

Figure 1 [

23].

2.2. Definitions of Research Questions

The systematic review focused on answering two essential research questions to explore the integration of IoT into POL systems comprehensively. These questions guided the review process and formed the basis for data synthesis and analysis.

Based on study motivation and objectives (

Section 1.2), we propose following research question (RQ) to guide the search and selection process:

R.Q.1: What are the technological approaches and techniques used to integrate IoT in POL systems?

R.Q.2: What are the pedagogical approaches and methods used to integrate IoT in POL systems?

The first research question aimed to classify and evaluate the range of IoT technologies and approaches used in POL systems, such as Physical Devices and Controllers used in IoT based POL systems, IoT protocols and communication models, Middleware and IoT Platforms, Data Processing (Cloud, Edge and Fog Computing), IoT Tools and frameworks, Learning Analytics and AI/ML Integration and Security and Privacy (Encryption, Authentication and Authorization, Blockchain). The second research question identifies and analyses main pedagogical approaches and methods used in IoT-based POL systems such as Personalized and Adaptive Learning, Collaborative Learning, Active and Interactive Learning, Problem, Project and Task based Learning Approaches, Cognitive Load Theory based approaches, knowledge presentation approaches and main feedback techniques.

These research questions collectively provided a structured framework for analyzing the intersection of IoT technology, educational practices and the challenges inherent in creating effective, inclusive and secure POL systems. The findings derived from addressing these questions contribute to a deeper understanding of IoT’s transformative potential in education.

2.3. Conducting the Search

Identifying the search string of publications was the first step in conducting a systematic review research process. To identify keywords and formulate search string from research questions we followed PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes) criteria developed by Petersen et al. (2015) [

23]. These criteria are defined in

Table 1.

Table 1.

PICO of the study.

Table 1.

PICO of the study.

| Property |

Description |

| Population |

Primary studies which integrate IoT in POL systems (both theoretical and empirical studies). |

| Intervention |

Technological and pedagogical approaches utilized within IoT based POL systems. |

| Comparison |

Comparing different technological and pedagogical approaches employed within IoT based POL systems. |

| Outcome |

Evaluation of technological and pedagogical approaches used in IoT based POL systems. |

To explore how IoT is integrated in POL systems in primary studies we formulated a search string that reveals combination of IoT and POL systems. There are three main concepts of the search string ‘‘Internet of Things’’, ‘‘Personalized” and “Online Learning’’ derived from research questions. Our basic string was (Internet of Things AND Personalized AND Online Learning). To extend the scope of research we conducted an investigation of literature for synonyms or interchangeably used terms of identified main concepts. To construct the full string, we used AND Boolean operator to combine main concepts and OR Boolean operator to express synonyms or interchangeably used terms of main concepts.

To conduct our research, we implemented the search string in ACM and IEEEXplore digital libraries and on Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) and Springer Link databases. To find latest trends we limited the research from January 2017 to March 2023. Based on the research methodology detailed in this section, the subsequent section presents our findings, highlighting Technological and Pedagogical approaches employed in IoT based POL systems.

From an initial pool of approximately 6,500 articles retrieved through the search protocol, 61 studies were ultimately selected for inclusion after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Detailed results of implementation of search string and results are show in

Table 2.

Inclusion criteria focused on peer-reviewed articles published within the last seven years, emphasizing empirical, experimental, or theoretical studies related to IoT integration in POL. Papers that tangentially mention IoT integration in POL are not included in the study.

Table 3 provides detailed Inclusion and Exclusion criteria that guided candidate studies selection process.

Table 2.

Number of unique studies and search strings (Time interval: 2017–2023).

Table 2.

Number of unique studies and search strings (Time interval: 2017–2023).

| Source |

Basic string |

Full String |

Invalid Resources |

Duplicates within Search Strings |

Duplicates between Databases |

Library Total |

| ACM Digital Library |

305 |

165 |

79 |

13 |

23 |

355 |

| Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) |

8 |

898 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

899 |

| IEEEXplore |

38 |

150 |

1 |

9 |

0 |

178 |

| Springer Link |

2363 |

2514 |

1 |

565 |

4 |

4307 |

| Total |

2714 |

3727 |

88 |

587 |

27 |

5739 |

Table 3.

Criteria used for including and excluding research studies.

Table 3.

Criteria used for including and excluding research studies.

| Inclusion Criteria |

Exclusion Criteria |

| Included content of IoT that investigates Educational perspectives to POL i.e., methods, frameworks and use cases |

Duplicate papers from the same study in different databases. |

| Published between January 2017 and March 2023. |

Mention of IoT is tangential with different scopes not directly related to POL |

| Written in English with full-text available. |

Publications not written in English |

| Peer-reviewed journal literatures |

Publications not directly related to our topic |

| Included content of IoT that investigates Educational perspectives to POL i.e., methods, frameworks and use cases |

Full-text is inaccessible |

2.4. Screening of Paper

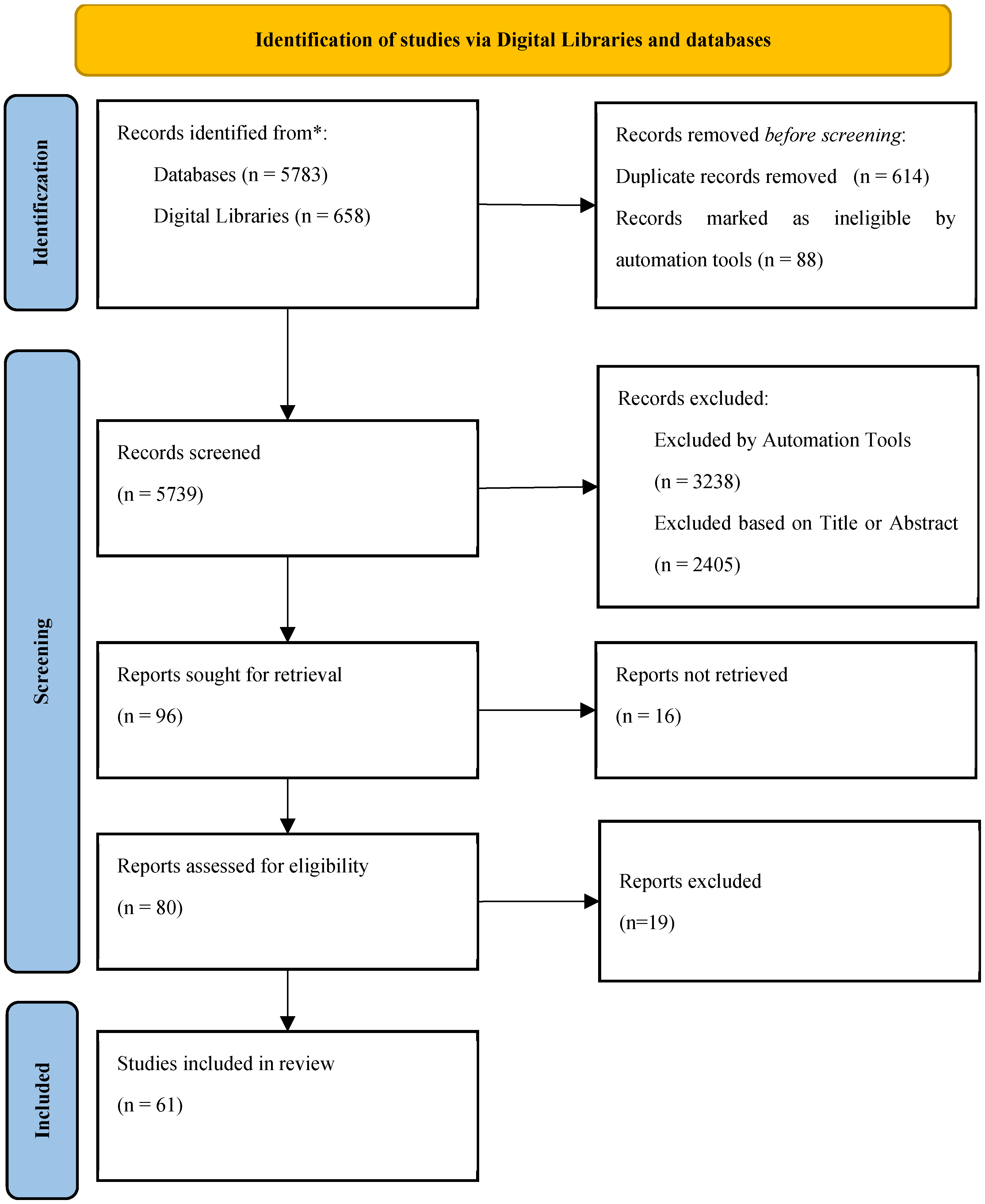

Based on the research questions and Inclusion and Exclusion criteria of this mapping study the most relevant papers were identified during the screening process. Based on study title, abstract and keywords we included or excluded each study found with the search string. From the database search, we identified a total of 6441 papers published during 2017– 2023-time span. Most of the publications are in the Springer link digital database.

Phase 1 involved the automatic removal of 88 invalid sources not meant for citation, such as workshop programs, keynotes, book covers, speeches, retracted articles, PhD thesis and unpublished works. Furthermore, with the help of spreadsheet software we automatically removed 614 duplicate papers. Thus, 5739 references remained. In phase 2, we applied further filtering, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria,

Table 4, to titles and keywords, producing 2510 and then we manually excluded 2405 articles firstly based on titles and then based on abstracts studies as recommended by [

55] resulting on 96 candidate studies. Furthermore, 16 irretrievable studies were removed from analysis. In the last phase after full text reading of candidate studies we excluded 19 papers as not totally related to our systematic mapping study resulting on 61 accepted studies. The number of included and excluded papers for each Phase is presented in

Figure 2 by using the PRISMA flowchart.

The following section presents key findings of the systematic mapping study, offering insights that directly reflect the study’s objectives. To outline the results, we followed the structure and layout of a systematic mapping study conducted by Cico et. al. [

24].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Results

Table 4 presents the distribution of publications over the years from January 2017 to March 2023 of primary studies.

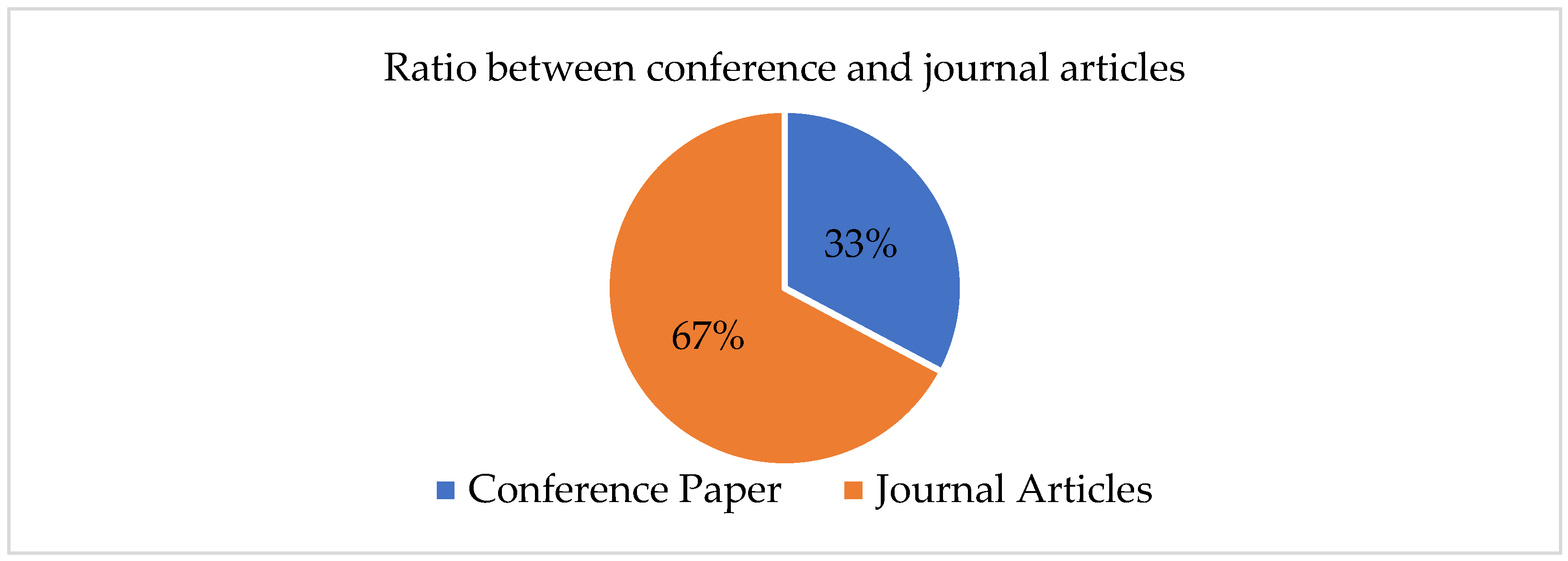

The integration of IoT into POL systems is an interdisciplinary field between information technology and education. For this reason, finding nearly 43% of the primary studies in ERIC database makes sense, as this database contains scholarly articles related to education and the integration of different technologies into education to improve the quality of learning. The Springerlink database is the second most utilized source, with 17 publications, representing 28% of the total.

Figure 4 provides an overview of the distribution of publications across different digital databases and libraries.

Figure 4.

Number of included studies (publication databases and digital libraries).

Figure 4.

Number of included studies (publication databases and digital libraries).

Figure 5 presents the distribution ration of selected studies based on publication type.

Figure 5.

Ratio of included studies between conference and journal articles.

Figure 5.

Ratio of included studies between conference and journal articles.

Table 5 provides a detailed list of journal titles with more than one study selected.

In addition, there was only one conference titled “2019 IEEE 25th International Symposium for Design and Technology in Electronic Packaging (SIITME)” that has more than one selected study.

3.2. What are the Technological Approaches and Techniques Used to Integrate IoT?

This systematic review identified a variety of technological approaches and techniques used in IoT-based POL systems. These approaches leverage advancements in IoT, machine learning and real-time data analysis to create adaptive and learner-centered educational environments. IoT technological approaches in POL systems are analyzed based on Internet of Things World Forum (IoTWF) reference model architecture to identify implemented approaches.

The IoTWF reference model is a seven-layer architecture designed to standardize and guide the development of IoT systems. Each layer has specific functions that, when integrated, facilitate seamless data flow and interaction between devices and applications. In the context of POL, this model can be applied to create adaptive and responsive educational environments [

25].

3.2.1. Physical Devices and Controllers Used in IoT Based POL Systems

The integration of IoT devices into POL environments involves diverse technologies that enhance educational experiences by leveraging real-time data collection and adaptive learning capabilities. Raspberry Pi 3.0 serves as a critical learning edge device due to its compatibility with major broker architectures, offering greater software library support than smaller platforms like Arduino, ESP32 and Photon [

26].

Mobile devices play a significant role, particularly in low-income regions, where their widespread possession enables educational access without advanced infrastructure. They are utilized to deliver Augmented Reality (AR) content, facilitating flexible and portable learning experiences, as well as supporting active learning through apps and fieldwork [

27,

28,

29]. Additionally, smart mobile devices such as iPads and iPhones enhance personalized learning environments by supporting communication and collaboration between students and tutors, both on and off campus [

30].

Wearable devices, including wristbands, smartphones and smartwatches, provide a wealth of data to monitor students’ physiological and engagement levels during learning activities. Wristbands, for instance, measure heart rate and blood pressure, offering insights into physical and mental states [

5]. Smartwatches, equipped with biosensors, track metrics like heart rate variability in real-time, ensuring a non-invasive data collection process [

31]. Beyond health monitoring, wearable technologies assess engagement levels through methods such as electro-dermal activity and skin temperature analysis, enabling tailored feedback and improving student interaction in digital learning [

32].

IoT sensor technologies significantly enhance context awareness in POL. Systems equipped with accelerometers, GPS and ambient light sensors gather data on motion, location and environmental conditions to adapt content formats to suit learners’ environments [

4]. Advanced setups include NFC readers and tags, which facilitate interaction between learners and IoT-integrated robots for immersive educational experiences [

33]. A prototype developed with Arduino Uno R3 and Grove modules measures classroom conditions like temperature, humidity and air quality, transmitting the data online for analysis [

34]. Furthermore, multi-touch systems with biometric scanners and interactive whiteboards improve classroom engagement and digital attendance, while RFID technologies streamline campus operations, including attendance and parking management [

35]. IoT-enabled devices embedded in educational settings not only track students’ psychological well-being but also manage academic resources efficiently. Sensor networks, including webcams and fitness trackers, collect emotional and behavioral data that inform adaptive learning processes, fostering a holistic educational experience [

36].

The integration of IoT devices into POL environments leverages diverse technologies—ranging from edge devices like Raspberry Pi to mobile, wearable and sensor-based systems—that collectively enhance educational experiences by enabling real-time data collection, adaptive content delivery, physiological monitoring and context-aware learning, ultimately fostering flexibility, engagement and personalized education across varied learning contexts.

3.2.2. Communication Technologies

The use of IoT protocols and communication models are essential to integrate IoT in POL systems. This integration relies on protocols such as MQTT, AMQP, CoAP and XMPP to establish efficient and secure communication frameworks. CoAP is particularly well-known for its resource efficiency in low-power scenarios, while MQTT and AMQP excel in managing large-scale operations and topic hierarchies, making them suitable for expansive educational systems [

26,

37,

38]. Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) supports seamless, non-intrusive data transmission from wearable devices to connected systems, ensuring that data collection remains distraction-free for learners [

39]. Furthermore, application-layer protocols like MQTT and AMQP play a crucial role in enabling advanced AI-driven functionalities, such as adaptive and prescriptive learning, by effectively transmitting data to cloud environments for analysis [

38]. Additionally, network infrastructures like 3G mobile networks ensure broad signal coverage for the delivery of educational content, while cloud communication layers enhance overall system responsiveness and scalability in smart learning scenarios [

6,

40].

The communication models used in IoT-based POL systems leverage both network-level and device-to-device interaction to ensure dynamic data exchange and system scalability. Publish-subscribe models, supported by protocols like MQTT and AMQP, enable real-time communication between sensors, devices and servers, which is critical for adaptive learning environments [

26,

37]. BLE further facilitates device-to-device communication, particularly for wearable devices, ensuring smooth data flow without disrupting learning activities [

39].

The integration of IoT into POL systems relays on robust communication models and protocols, such as MQTT, AMQP, CoAP and BLE, which ensure efficient data exchange, scalability and support for adaptive learning functionalities, while network infrastructure enhance responsiveness and system-wide scalability.

3.2.3. Middleware and IoT Platforms

In IoT-based POL, APIs are crucial for integrating advanced functionalities into learning tools. For emotion recognition, APIs such as Microsoft Cognitive Services-API, Google Cloud Vision-API and CLMtrackr enable the detection of emotions and facial expressions from images and videos, facilitating the personalization of learning content without requiring extensive machine learning expertise [

41]. A webcam-based tool leverages these APIs, along with additional features like eye-gaze tracking and heartbeat monitoring, to assess learners’ emotional states and adapt content to their needs [

36]. Additionally, the Dialogflow API is employed to automate data management tasks, such as uploading and updating learning content, streamlining the development process by directly building intents from the database [

42].

IoT platforms like MaTHiSiS integrate sensors in devices such as laptops, tablets and smartphones, capturing data on learners’ affective states to personalize educational content. These systems also leverage mobile and robotic devices, which are equipped with sensors to gather data on students’ interactions and emotional health [

8]. These integrations collectively enhance the ability to provide a responsive and tailored learning experience.

3.2.4. Data Processing and Storage

The findings from selected research studies highlight the fundamental role of IoT, edge computing and cloud-based technologies in enhancing online education systems by providing scalability, flexibility and cost-effectiveness for personalized learning services. Raspberry Pi 3.0 is identified as an effective edge device for IoT applications in education due to its compatibility with major broker architectures, surpassing smaller platforms like Arduino, ESP32 and Photon [

26].

The Cloud of Things (CoT) framework is utilized to combine IoT with cloud computing, ensuring robust infrastructure for data storage, processing and service delivery [

43]. Cloud computing enables the deployment of learner models and personalization parameters as web services hosted on various servers, ensuring high availability [

44]. A personal cloud environment bridges the digital divide by enabling learners to access resources without relying on high-end devices. The integration of mobile learning with cloud-based services promotes resource sharing and expands access to educational resources and knowledge exchange while reducing institutional technology burden [

45]. Real-time synchronization of sensor data and programs through cloud storage allows teachers to monitor student activities, promoting collaboration and cross-user interaction [

37]. Tools like Google Meet, Sheets, Forms and Classroom exemplify how cloud-based platforms can facilitate virtual meetings, data management, assessments and coursework organization, supporting flexible and accessible learning experiences [

46].

The integration of IoT with cloud computing is critical for creating smart educational systems. The cloud layer not only serves as a secure data repository but also integrates big data analytics to interpret patterns and communicate insights to IoT devices [

6]. Advanced processing services, including affect detection and learning graph adaptation, are hosted in the cloud, enhancing the platform’s adaptability, scalability and performance [

8]. The use of Content Delivery Network (CDN) ensures efficient distribution of educational materials while maintaining high performance and security through encryption and tokenization processes [

30].

3.2.5. Tools and Frameworks

The Learning Ecology Framework emphasizes the design of effective Ubiquitous, Mobile and Immersive (UMI) educational scenarios by focusing on space and time considerations. These aspects distinguish UMI scenarios from generic technological tools, ensuring they are integrated into educational contexts with clear differentiation. This framework supports educators in creating environments conducive to adaptive learning [

47].

A Virtualization Framework is proposed using VMware vSphere Hypervisor-ESXi to establish a technical foundation for mobile cloud learning. It optimizes learning by integrating various educational technologies into a cost-effective, collaborative platform. This framework plays a key role in outcome-based education, enabling efficient knowledge transfer and resource sharing for personalized learning experiences [

45].

The Data Analytics Framework addresses the processing and analysis of IoT data from heterogeneous sources. It enables adaptive learning environments by uncovering patterns and supporting knowledge discovery. A notable feature of this framework is its use of an ontology database for knowledge classification and exchange. Smart Objects autonomously exchange knowledge based on inference rules, enhancing adaptability and personalization [

38]. Additionally, Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques enrich this framework by generating hypothetical rules, such as synonyms and categories, to create dynamic knowledge bases.

A Reinforcement Learning (RL) Framework, named FaiR-IoT, adapts IoT applications to human variability using three levels of RL agents: Multisample RL, Governor RL and Mediator RL. These agents address intra-human, inter-human and multi-human variability, ensuring system fairness and personalization. Multi-agent RL further enhances this approach by optimizing interactions between humans and IoT systems. Simulation models validate its application, such as studying driving behaviors or human thermal comfort in smart homes [

48].

The Smart Learning Management Frameworks (SLMF) centralize educational components like lecture materials, assessments and feedback to streamline education management. This framework provides students with comprehensive access to their learning progress and course content, facilitating a structured and personalized learning experience [

30].

Voas’s Primitives Framework outlines IoT scenarios in education through its fundamental components: sensors, communication channels, aggregators, decision triggers and external utilities. This framework facilitates understanding the interactions and dependencies within IoT-enabled learning systems [

36].

A Contextual Bandit Framework is utilized to integrate student and environmental contexts into recommendation systems. By incorporating contextual features, this framework refines decision-making processes, ensuring enhanced personalization in learning recommendations [

49].

Adaptive Frameworks in mobile learning tailor content to learner profiles and goals. Context-aware modules are integral part of these frameworks, considering situational and learner-specific factors to recommend sequences of activities. The Situation, Background, Assessment and Recommendation (SBAR) Framework extends this approach by utilizing machine learning techniques like Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS) to model context and adaptively organize, present and facilitate learning interactions in mobile learning. By defining learning paths based on active learner feedback and context, SBAR enhances personalization and active engagement [

50].

The discussed frameworks collectively demonstrate the potential of integrating advanced technologies like IoT, data analytics, RL and virtualization into educational systems, emphasizing personalization, context-awareness and adaptability to enhance learning experiences, optimize resource utilization and foster active engagement in e-learning environments.

3.2.6. Learning Analytics and AI/ML Integration

Machine Learning (ML) plays a crucial role in IoT-based POL, enabling the adaptation of educational content and strategies to meet individual learner needs. Various studies employ ML techniques to classify, predict and analyze student engagement, behavior and knowledge states using IoT-generated data.

One approach leverages decision trees and rule-based systems, such as OneR, PART and J48 (C4.5), to model and predict student engagement patterns. These methods provide intelligible outputs that aid in understanding and optimizing student interactions within learning environments [

51]. Similarly, machine learning algorithms like RNN, RCNN and SOCSW are employed to enhance the Mod-Knowledge agent’s ability to classify student responses and questions. The use of supervised and unsupervised methods is determined by the characteristics of the dataset [

52].

Data mining and ML are also used to transform education by tailoring content based on individual preferences and cognitive demands, creating highly personalized learning experiences [

53]. Additionally, a ML-based context fusion model processes low-level multi-domain context DATA to derive high-level contextual information, enabling adaptive intelligence services in IoT environments [

54]. Clustering techniques, such as K-means, are applied to predict clusters of time-based data, providing insights into student behavior and engagement during e-learning sessions [

55].

In another study, supervised rule-based learning algorithms are highlighted for their ability to process IoT-generated data, transforming raw input streams into meaningful knowledge. These self-assigned rules play a key role in creating adaptive learning systems [

38]. ML techniques are also integrated with wearable devices to analyze activity data and enhance student health and engagement, promoting healthy behaviors alongside learning [

39].

Advanced classifiers such as AdaBoost, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting, SVM, KNN and Random Forest are utilized to predict and recommend personalized learning resources based on learner profiles [

56]. These algorithms analyze data collected from IoT devices to uncover student learning patterns and behaviors, enabling personalized learning experiences and providing actionable insights for educators [

35].

Other applications of ML include the development of intelligent guidance and personalized teaching strategies. Adaptive engines such as the ANFIS forms the foundations for customizing learning content and presentation to the learner’s needs [

50]. AI and ML capabilities embedded in smart mobile devices enable features like voice and face recognition and AR, allowing these devices to act as intelligent tutors that dynamically adjust to individual educational needs and preferences [

29].

ML serves as a foundation in IoT-based POL, offering diverse techniques and algorithms—ranging from rule-based systems and clustering methods to advanced classifiers and adaptive engines—that enable the analysis and adaptation of educational content, fostering personalized, context-aware and engaging learning experiences tailored to individual learner needs and preferences.

3.2.7. Privacy and Security

In IoT-based POL systems, various privacy and security techniques are employed to protect user data and ensure system reliability. These techniques focus on securing communication, preserving user privacy and safeguarding sensitive educational information.

The robustness of IoT-based learning platforms is ensured through comprehensive physical and network security measures. Testing procedures include assessing the system’s ability to recover from unauthorized shutdowns and implementing encryption techniques to protect user information during data transmission and storage [

57]. Firewalls are also utilized to restrict unauthorized access, maintaining the security and integrity of sensitive educational data [

1].

Some systems integrate mobile instant messaging (MIM) applications like Telegram for secure communication. Telegram’s features, such as data encryption and cloud storage, are leveraged to maintain privacy and confidentiality for both students and instructors. This integration demonstrates a focus on ensuring secure communication channels in educational settings, while also supporting collaborative learning and real-time feedback [

58].

Advanced privacy-preserving techniques such as Federated Learning (FL) and Differential Privacy (DP) are employed in the development of secure recommender systems. FL allows model training to occur directly on user devices, ensuring that sensitive data remains local and is not transmitted to a central server, thereby enhancing privacy. Differential privacy further strengthens the privacy by adding controlled noise to data, making it difficult to identify individual users from aggregated model outputs. Techniques such as gradient clipping and Gaussian noise are employed to safeguard the influence of any single data point on the model’s updates, ensuring compliance with privacy standards [

59].

In addition, encryption methods ensure secure data transmission, while role-based access control restricts unauthorized access, meanwhile blockchain technology offers a decentralized and tamper-resistant approach to safeguarding learner data, enhancing trust in adaptive systems [

16,

48].

In IoT-based POL systems, a multi-layered approach combining encryption, secure communication channels, privacy-preserving methods like federated learning and differential privacy and advanced technologies such as blockchain ensures the protection of sensitive user data, system reliability and compliance with privacy standards, fostering a secure and trustworthy educational environment.

3.3. What Are the Pedagogical Approaches and Methods Used to Integrate IoT in POL?

3.3.1. Personalized Learning

Personalized learning integrates diverse methods and techniques to adapt educational experiences to individual learners’ needs. Pedagogical strategies emphasize independence and flexibility, allowing learners to engage at their own pace with adaptive and personalized content. This includes adaptive content and evaluation systems focus on personalize assessments by aligning them with individual learning processes, mapping knowledge effectively, and promoting inclusivity [

57,

60]. Personalized mastery-based approaches enable learners to progress at their own pace where an adaptive instructional system leverage real-time data analysis to provide targeted scaffolding and feedback, enhancing personalized instruction and fostering more effective learning experiences [

16].

IoT-driven systems collect and analyze sensor data to tailor content based on learners’ emotional states, environmental contexts, and engagement levels. For example, Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is used to select focus-enhancing music [

61]. Smart devices also facilitate the creation of Personalized Learning Environments (PLEs) by adapting to contextual factors like location and noise levels [

29,

62]. The Personalized Context-Aware Recommendation (PCAR) system employs the Intelligent Personalized Context-Aware Learning (IPCAL) algorithm to analyze learning behaviors and adapt content to the learner’s environment and needs, delivering interactive, context-aware materials that foster engaging learning experiences [

40].

Technologies like the New multi-Personalized Recommender system for e-Learning (NPR-eL) integrate learner properties, including preferences, background knowledge, and memory capacity, to adapt learning materials [

63]. Personalized chatbots provide tailored feedback and content to address diverse learning styles and paces [

58], while adaptive engines structure educational materials hierarchically, transforming them into accessible formats like chatbots [

42]. Additionally, heuristic algorithms and evolutionary approaches, such as Ant Colony Optimization, sequence learning objects based on the learner’s context [

50]. Device context considerations ensure content is appropriately formatted for mobile devices, optimizing delivery [

64].

Personalized learning paths are generated based on learner profiles, considering factors such as course difficulty, concept continuity, and individual preferences. Web services provide personalization parameters like language preferences and knowledge levels, supporting efficient curriculum sequencing and enhancing engagement and learning efficiency [

44,

65]. Course recommendation systems further tailor content to learner profiles, addressing the “one size fits all” challenge by aligning resources with individual goals and preferences [

66,

67]. Multimedia recommendation tools assess readability and popularity metrics to match materials to learners’ levels and preferences [

2].

The combination of Cloud of Things (CoT) and Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) enables adaptive, scalable, and flexible personalization by leveraging real-time data for instant behavioral analysis. Technologies such as facial recognition enhance this process, allowing instructors to dynamically adjust teaching methods in response to students’ needs, feedback, and engagement, particularly in virtual classrooms [

30,

35,

43].

Personalized learning methods combine advanced technologies, behavior-based analytics, and adaptive pedagogies to create individualized learning experiences. By leveraging IoT and context-aware systems, these approaches improve engagement, efficiency, and learner outcomes across diverse contexts. The implementation of such models and systems highlights a growing trend toward tailored, student-centered education, emphasizing flexibility and inclusivity [

64].

Personalized learning effectively leverages IoT and adaptive technologies to tailor educational experiences to individual needs, employing a variety of strategies from personalized content adaptation to advanced data analytics. These approaches enhance learner engagement and achievement by delivering flexible, inclusive, and context-aware educational experiences, setting a robust foundation for future innovations in personalized education.

3.3.2. Adaptive Learning

Individualized approaches are central to adaptive learning, leveraging learner models to represent preferences, abilities, and levels. These models ensure content delivery is learner-centric, enhancing relevance and effectiveness. Adaptive tools such as reasoning mechanisms for personalized teaching strategies provide intelligent guidance tailored to individual needs. Similarly, systems like NPR-eL optimize personalization by integrating multiple learner characteristics, fostering student-centered learning environments [

1,

63,

68].

Adaptive e-learning platforms integrate emotional and contextual data to customize learning environments. For example, the MaTHiSiS platform uses learning graphs to adjust content based on progress and emotional responses. IoT-enabled systems further enhance education by dynamically adapting feedback and resources based on emotional engagement, often using biometric tools like facial emotion detection to modify content and teaching methods in real-time. These systems also address inclusivity by tailoring materials and strategies for students with special needs, ensuring equity in educational experiences [

8,

36].

Adaptive systems leverage models like the Felder-Silverman Learning Style Model (FSLSM), Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), and the Ortony, Clore, and Collins (OCC) framework to align content with learners’ styles, personalities, and emotional states. By tailoring material formats to individual preferences and contexts, these systems enhance comprehension and engagement. Features such as motivational strategies, interactive elements, and an adaptive engine that selects personalized content delivery modes further enrich the learning experience, making it more effective and user-centric [

4,

7].

Pedagogical methods in adaptive systems extend to adapting content for sociocultural and socioeconomic contexts, especially in low- and middle-income countries, aligning educational practices with local realities. Interactive and engaging content, designed with multisensory elements, addresses challenges related to learner engagement and comprehension of complex materials [

27,

69].

Cutting-edge approaches in adaptive systems include real-time brain activity monitoring, enabling dynamic content adjustments to maintain engagement and mitigate fatigue during critical moments. These innovations exemplify the potential of adaptive technologies to optimize learning experiences at a granular level [

70].

Adaptive e-learning systems demonstrate the integration of personalized pedagogical methods and cutting-edge technologies, such as IoT and real-time emotional monitoring, to create dynamic, inclusive, and effective learning environments tailored to diverse learner needs and contexts, thereby revolutionizing educational experiences and outcomes.

3.3.3. Collaborative Learning

Selected research articles highlight a wide range of methods, techniques and approaches employed to foster collaborative learning in various educational settings. By leveraging technology and pedagogical innovations, these approaches aim to enhance student engagement, teamwork and critical thinking.

One approach focus on mobile device integration to support communication and interaction among students and educators in a framework based on social constructivist theory. This approach emphasizes student-centered learning and active engagement through collaborative interactions with peers and instructors [

27]. Similarly, the WIoTED system facilitates collaborative and student-centered learning environments by enabling students to engage with smart objects and wearable devices, employing active-participatory methods to significantly improve engagement and learning outcomes [

51]. Another method integrates scientific inquiry and reflection into collaborative scenarios, blending constructivist principles with problem-solving tasks to promote authentic learning experiences [

47].

Digital tools such as forums, messaging and chat platforms are main instruments utilized in building communities of learners. These tools encourage peer interaction, enabling students to collaboratively understand and apply course materials [

66].

Several studies emphasize group-based learning activities. For instance, students collaboratively design and execute experiments, fostering teamwork and problem-solving skills [

37]. A Problem-Based Learning in Cloud Learning Environments (PBL-CLE) process further enhances collaboration by allowing students to collectively research, discuss and synthesize knowledge, strengthening their analytical thinking abilities [

46]. An AR-based approach also encourages peer discussions and collaborative problem-solving, utilizing augmented reality to engage students in joint learning activities [

28]. In addition, a tool like Google Docs is highlighted in enabling learners to work together on multimedia projects, sharing information effectively and promoting teamwork [

2]. Similarly, the MaTHiSiS platform incorporates activities that encourage peer support and communication, enhancing collaborative understanding through teamwork [

8]. Moreover, learning management systems are employed to support collaborative and volunteering activities, particularly in enhancing speaking and writing skills, thereby developing social and personal capabilities [

53].

IoT technologies are also highlighted for their ability to foster collaborative environments through hands-on tasks and communication, which improve both technical and conceptual understanding. Group activities like developing energy-saving strategies demonstrate how collaboration can foster critical teamwork and communication skills [

6,

71].

Advanced strategies include the application of multi-agent RL, reflecting collaborative pedagogies where multiple agents (or learners) work together to solve problems and achieve shared goals [

48]. A notable technique involves a teaching coordination agent within a student learning module, which facilitates knowledge sharing and problem-solving through a collaborative mechanism [

1].

These studies emphasize the significance of collaborative learning methods and technologies in enhancing critical thinking, communication, and teamwork skills, thereby creating a more interactive and engaging educational experience.

3.3.4. Active and Interactive Learning

Active learning is facilitated through diverse methods, techniques and approaches designed to actively engage learners and promote their participation in the learning process. Reflective practices, metacognition, and effective communication are essential components of strategies aimed at fostering active learning and enhancing student engagement at a deeper level [

58]. Active learning is emphasized in techniques where learners engage through quizzes, assignments and collaborative platforms, ensuring they are not mere recipients of information but actively participate in the learning process [

66]. Dialogue-based active learning is another effective approach, as tools like forums and chats facilitate knowledge-building through interaction [

72]. In addition, proactive learning suggestions delivered by chatbots encourage students to take ownership of their academic performance by focusing on controllable learning factors [

73].

Active learning extends beyond traditional settings through mobile-enabled fieldwork and practical experiences, while challenge-based Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) embody its principles by replacing traditional lectures with interactive, dynamic scenarios that foster engagement and diverse learning experiences [

29].

Interactive learning encompasses a variety of methods, techniques and approaches aimed at fostering engagement, collaboration and practical understanding. Scenario-based interactive learning environments leverage real-world contexts to create engaging and relatable experiences, particularly for young English Foreign Language (EFL) learners. By incorporating virtual tutors and interactive discussions, these models enhance comprehension while fostering meaningful connections with the material. This approach ensures an enjoyable and effective learning process by integrating practical scenarios that resonate with learners [

33].

Interactive learning strategies, including pair work and group activities, are designed to enhance engagement and reduce anxiety in virtual language classes. By fostering collaboration and interaction, these techniques help combat feelings of isolation and boredom, promoting a sense of community and active participation among students [

74].

Collaborative and interactive learning leverages a group-oriented approach, enabling students to share resources and build collective knowledge through personal cloud environments. This integration facilitates seamless access to learning materials and encourages the exchange of ideas, fostering a dynamic and enriched learning experience [

45].

Textual and interactive learning integrates structured course materials with interactive dialogues and discussions, guided by a textual tutor functioning as a virtual teacher. This approach enhances comprehension through interactive engagement, enabling learners to absorb and apply knowledge more effectively [

68].

Integrating IoT devices like Raspberry Pi and sensor modules into the classroom enhances interactive learning by providing hands-on technological experiences. This approach stimulates curiosity, builds technical skills, and deepens understanding through practical engagement, making it a fundamental element of active learning [

2]. IoT- based smart laboratories facilitate real-time interaction with sensors and smart objects, promoting both hands-on practical experiences and the development of cognitive skills in educational settings [

6]. Smart devices and sensors in interactive learning environments enhance engagement by enabling real-time interaction with educational content. The integration of IoT increases interactivity, creating a dynamic and immersive learning experience [

75].

Innovative interactive environments, such as those in museums, leverage immersive technologies like smart glasses to enhance educational experiences. These tools enable learners to interact more deeply with exhibits, enriching content and fostering greater engagement, demonstrating the versatility of interactive learning in non-traditional settings [

76].

A wide range of strategies and techniques utilized in interactive and active learning, from dialogue-based tools to IoT-enhanced environments, illustrate the transformative potential of integrating advanced technologies and collaborative approaches in education. These methods not only deepen engagement and comprehension but also foster an inclusive, dynamic, and hands-on learning atmosphere, ultimately enhancing the educational experience across various settings.

3.3.5. Problem-Based Learning Approaches

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) emerges as a prominent approach that involves learners in tackling real-world problems to develop solutions through active participation and critical thinking. It is supported by IoT technologies in ubiquitous learning systems to enhance hands-on experiences [

26]. PBL follows a structured process that includes problem posing, analysis, understanding, researching, synthesis, conclusion, evaluation and presentation, fostering deeper learning engagement [

46]. The use of AR applications further augments PBL by enabling students to solve operational problems interactively [

28].

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) fosters critical thinking and collaborative problem-solving through teacher-led questions, supported by interactive platforms and discussion areas that enhance communication, knowledge exchange, and engagement in online learning environments [

67].

Project-Based Learning (PjBL) emphasizes real-world application through student-driven projects, where students design multimedia instructional tools, fostering collaboration, active engagement, and hands-on learning. These educational strategies leverage hands-on learning techniques, with IoT sensors enabling direct interaction with technology to make abstract scientific concepts tangible, while dataflow programming fosters computational thinking by integrating practices like data collection, transformation, and visualization into science education [

37]. Similarly, the GAIA project highlights practical exercises involving IoT devices such as Raspberry Pi and sensors to collect and analyze environmental data, aiming to enhance students’ digital skills and real-world IoT applications experience [

71].

UMI-oriented educational scenarios emphasize hands-on activities such as interaction, experimentation, project management, and artifact creation, while interdisciplinary PjBL integrate IoT concepts into practical applications, promoting active knowledge construction and skills [

47].

Task-Based Learning (TBL) focuses on practical activities that simulate real-world applications. For instance, task-based activities within virtual worlds include grammar quizzes and conversational exercises to enhance language skills [

77]. IoT supports TBL by providing real-time feedback and encouraging active participation in learning activities [

53]. A specific example involves participants completing tasks in natural language within an Active and Assisted Living (AAL) context, which required understanding and visually modeling tasks, bridging theoretical knowledge and practical application [

41].

In summary, these methodologies, techniques and approaches illustrate diverse and innovative ways to engage students in meaningful, real-world problem-solving and learning experiences. Each method integrates technology and interactive strategies to deepen learning outcomes and skill development in various educational contexts.

3.3.6. Cognitive Load Approaches

The application of Cognitive Load Theory and related approaches is evident in various studies, utilizing diverse methods and techniques to enhance learning outcomes. These efforts focus on optimizing instructional design, leveraging multimedia tools and stimulating cognitive and metacognitive development.

Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning, applied in chemistry education, emphasizes combining auditory and visual elements to help learners visualize and comprehend abstract concepts, enabling educators to create engaging multimedia materials that enhance mental representation and improve learning effectiveness [

78].

The integration of Embodied Cognitive Theory in the metaverse leverages immersive virtual environments to foster deeper understanding through sensorimotor engagement, while approaches like the Focus on Language and Cognitive Development utilize human-like feedback and bodily movements to enhance holistic learning; meanwhile, Cognitive Load Theory addresses cognitive regulation by optimizing instructional design to balance cognitive demands, prevent overload, and improve retention [

5].

In the realm of neuroscience and digital learning, the Digital Dynamic Modulation (DDM) technique is utilized to enhance cognitive functions by embedding beta wave frequencies into video content. This innovative method aims to improve attention, memory and awareness levels, offering a technologically advanced approach to cognitive enhancement. By stimulating the brain’s beta frequency range, learners can experience improved short-term and long-term memory retention, crucial for effective education [

70]. Lastly, personalized learning environments (PLEs) are enriched with Cognitive and Metacognitive Assistance to aid students in developing their thinking and learning strategies. Smart mobile devices facilitate this personalization, enabling students to engage in tailored cognitive support that addresses individual learning needs [

29].

Collectively, these methods and approaches demonstrate a multifaceted effort to implement cognitive load theory and its variants, enhancing the learning process through multimedia, immersive environments and personalized technologies.

3.3.7. Knowledge Presentation Approaches

The content presents a structured approach to knowledge organization, response generation and learning enhancement, leveraging various methods and techniques. Each method, paired with its respective strategies, showcases a robust framework for improving educational experiences.

The knowledge abstraction and response generation methodology emphasizes analyzing course content and tailoring responses using tools like Dialogflow. This dual approach not only extracts insights from course materials but also utilizes data-driven characteristics to customize responses effectively [

42].

Knowledge exchange and learning is another approach, where Smart Objects (SOs) autonomously exchange knowledge through advertising and service searching. This approach mirrors collaborative learning, allowing entities to share information dynamically, fostering a symbiotic learning environment [

38].

A significant contribution to personalized learning comes through curriculum sequencing, which aligns learning materials with individual learner profiles. These profiles consider factors such as course difficulty and concept continuity, ensuring tailored learning paths that enhance educational outcomes. This approach is essential for personalized e-learning systems, emphasizing efficiency and learner-centric progression [

65].

Additionally, a system proposed by [

8] supports non-linear learning paths, aligning with individual learning styles and preferences. This flexibility enhances the adaptability of IoT-based educational frameworks, catering to diverse learning paces and improving overall engagement and understanding.

The integration of knowledge organization techniques is exemplified by the “Story of Things” system. Here, IoT and augmented reality enhance hands-on interactions, enabling young learners to learn about objects from their daily lives, fostering practical and interactive learning experiences [

36].

Knowledge tracing emerges as a critical pedagogical approach, using machine learning algorithms to analyze student interactions and measure their knowledge states. This method, facilitated by the Mod-Knowledge agent, supports personalized material recommendations and ensures the learner’s progress is both supported and informed [

52]

Effective knowledge transfer is another highlighted strategy, ensuring learners can not only access but also utilize acquired knowledge effectively. This aspect underscores the importance of facilitating meaningful learning outcomes through accessible and practical knowledge dissemination frameworks [

50].

The integration of ontology and knowledge classification organizes information into primary, secondary, and invented categories, enabling adaptive learning frameworks in IoT systems to effectively structure educational content for enhanced comprehension and learner adaptability [

38].

This combination of methods, ranging from machine learning-driven knowledge tracing to the integration of IoT in practical learning, underscores a comprehensive strategy to enhance educational experiences across varied learning paradigms.

3.3.8. Feedback Approaches

The integration of feedback mechanisms into educational systems is demonstrated through a variety of methods, techniques and approaches that enhance learning effectiveness and personalization.

Interactive mechanisms such as quizzes with hints and feedback encourage active engagement and self-assessment. Learners can rate the helpfulness of hints, promoting active learning and providing insights into their understanding of the material [

7]. In addition, quizzes and feedback-driven systems adapt recommendations based on learner input, promoting active and effective content delivery [

40].

Direct observation methods [

51] enable teachers to monitor student engagement and provide real-time feedback, fostering immediate adjustments to teaching strategies. Likewise, feedback systems designed to enhance motivation through interactive learning objects [

62] ensure that students remain actively involved in the learning process. The adaptability of learning strategies is emphasized in systems where students monitor environmental conditions, allowing immediate feedback to inform adjustments to their strategies or environments. The integration of RL adds another layer, where systems adapt through experiential learning and feedback, mirroring traditional pedagogical approaches [

34]. Similarly, RL framework adapt strategies based on performance feedback, aligning with iterative educational processes where formative assessments and performance metrics refine learning strategies and strengthen conceptual understanding through continuous feedback [

48].

Iterative learning approaches are seen in systems like Dataflow, which utilize live feedback and data visualization to help students debug and refine their experiments. Post-experience surveys reflect on students’ attitudes and experiences, enabling educators to adjust pedagogical methods [

37]. Broader system approaches integrate input, process, output and feedback components, ensuring interconnectedness and continuous improvement in learning outcomes through systematic feedback and assessment [

46].

Evaluation metrics such as Hits@k and normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain at k (nDCG@k) [

59] and System Usability Scale (SUS) [

41] serve as feedback mechanisms in assessing systems’ performance and learnability. These methods ensure iterative refinement, similar to formative assessment in educational contexts.

Biofeedback methods monitor physiological signals, providing real-time feedback on students’ health and learning behaviors, which supports academic success [

31]. Incorporating IoT devices [

70] enables dynamic adjustments to educational content based on learners’ brain activity, providing real-time feedback to maintain engagement.

Assessment modules and continuous feedback mechanisms enable personalized learning by evaluating students’ understanding and guiding improvement, while teacher-student interaction through feedback collection supports adaptive teaching strategies and intelligent guidance [

1].

Chatbots with tailored feedback support diverse learning styles to promote inclusivity, while rating systems ensure high-quality interactions and continuous improvement through response evaluation [

58,

73].

This diversity of methods and approaches underscores the importance of feedback in enhancing both individual and systemic educational processes, tailored to varied learning environments and goals.

3.4. Main Research Gaps in IoT based POL Systems

We categorize identified main research gaps based on conducted research questions. Following section summarize main research gaps in relation to technological and pedagogical approaches implemented.

3.4.1. Main IoT Technological Integration Research Gaps

Research on integrating IoT technologies into POL systems has revealed several significant gaps that require attention. One critical area is the optimization of architectures and cost reduction. Studies suggest the need for exploring alternative IoT messaging protocols such as Data Distribution Service (DDS) and more affordable hardware solutions like Arduino-based microcontrollers. Additionally, optimizing the system core, including data center processes, and evaluating back-end servers for enhanced efficiency in data processing and fog computing, remains an unmet requirement [

26].

The integration of context awareness into IoT systems is another gap in current research. While many systems focus on technical performance, they often neglect to evaluate how effectively these technologies adapt to diverse user environments and conditions. For instance, assessing the contextual adaptability of learning systems is essential to ensure their relevance across varying scenarios and individual needs [

4,

62]. Similarly, scalability issues and the lack of longitudinal studies limit the understanding of IoT systems’ long-term impacts on personalized learning. Most studies involve short-term evaluations and lack diversity in sample populations, underscoring the need for broader and longer-term research [

34,

40].

Emerging technologies such as augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and advanced machine learning remain underutilized in IoT-enabled learning systems. These technologies have immense potential to enhance personalization by providing adaptive learning paths and real-time feedback. However, their integration is still in its infancy, leaving significant opportunities for further exploration [

7,

43]. Similarly, applying multimodal learning analytics, which involves integrating data from sensors, accelerometers, and video, remains a gap. Such analytics could substantially improve the adaptability and outcomes of learning systems but have yet to be adequately explored [

38,

51].

Another crucial gap lies in ensuring usability and accessibility across diverse devices. Many IoT systems lack user-friendly interfaces, making them less accessible and limiting their broader application [

51,

62]. In addition, security and privacy concerns, particularly regarding data authenticity and confidentiality in IoT-based learning systems, remain a pressing issue that warrants comprehensive research and technological innovation [

31,

43].

Lastly, while IoT systems can monitor physical and emotional states through advanced sensors, limited studies examine how these variables influence learning outcomes. For example, tracking factors like temperature, air quality, and emotional engagement could provide valuable insights into optimizing learning environments but require more focused investigation [

5,

34].

3.4.2. Main IoT Pedagogical Integration Research Gaps

Pedagogical research gaps in integrating IoT technologies into POL systems reveal several critical areas for development. A significant challenge lies in the absence of well-defined pedagogical frameworks to align IoT technologies with teaching objectives. While smart laboratories have demonstrated the potential for interactive and practical learning, the lack of structured methodologies prevents educators from fully leveraging IoT tools to achieve desired educational outcomes. This gap is especially pronounced when attempting to integrate authentic tasks that promote active learning [

6].

Another pressing issue is the limited ability of current systems to address the diverse learning needs of individual students. Many IoT-based platforms fail to accommodate variations in learner profiles, cognitive demands, and preferences. This limitation is particularly evident in systems that aim to monitor emotional and cognitive engagement but struggle to dynamically adapt to these variables in real-time. These gaps prevent the full realization of personalized learning experiences, particularly in environments where social and emotional learning is critical [

59,79].

Quantifying the human learning state outside laboratory-controlled environments remains a substantial research challenge. IoT systems often cannot distinguish learning-specific physiological signals from other states, such as stress or distraction. This shortfall affects their ability to offer real-time feedback and tailored learning interventions, which are essential for improving educational outcomes in dynamic settings [80].

Furthermore, the lack of interactivity in IoT-based systems limits their engagement potential. While these tools provide personalization through data analysis, they frequently overlook mechanisms for delivering real-time, adaptive feedback that enhances student participation. Without these features, IoT-enabled learning systems risk reducing motivation and engagement, key factors for successful learning outcomes [

2,

67].

Finally, ethical and privacy concerns present a significant barrier to adopting IoT technologies in education. The collection and analysis of sensitive student data raise questions about data security and responsible use. Despite the growing prevalence of IoT in learning environments, comprehensive strategies to address these concerns remain underdeveloped, posing risks to trust and adoption [

31,

48].

These research gaps provide a roadmap that requires interdisciplinary collaboration to design IoT systems that integrate advanced technologies with robust pedagogical strategies, ensuring they become more adaptive, efficient, ethical and secure and provide effective learning outcomes.

4. IoT based POL Framework

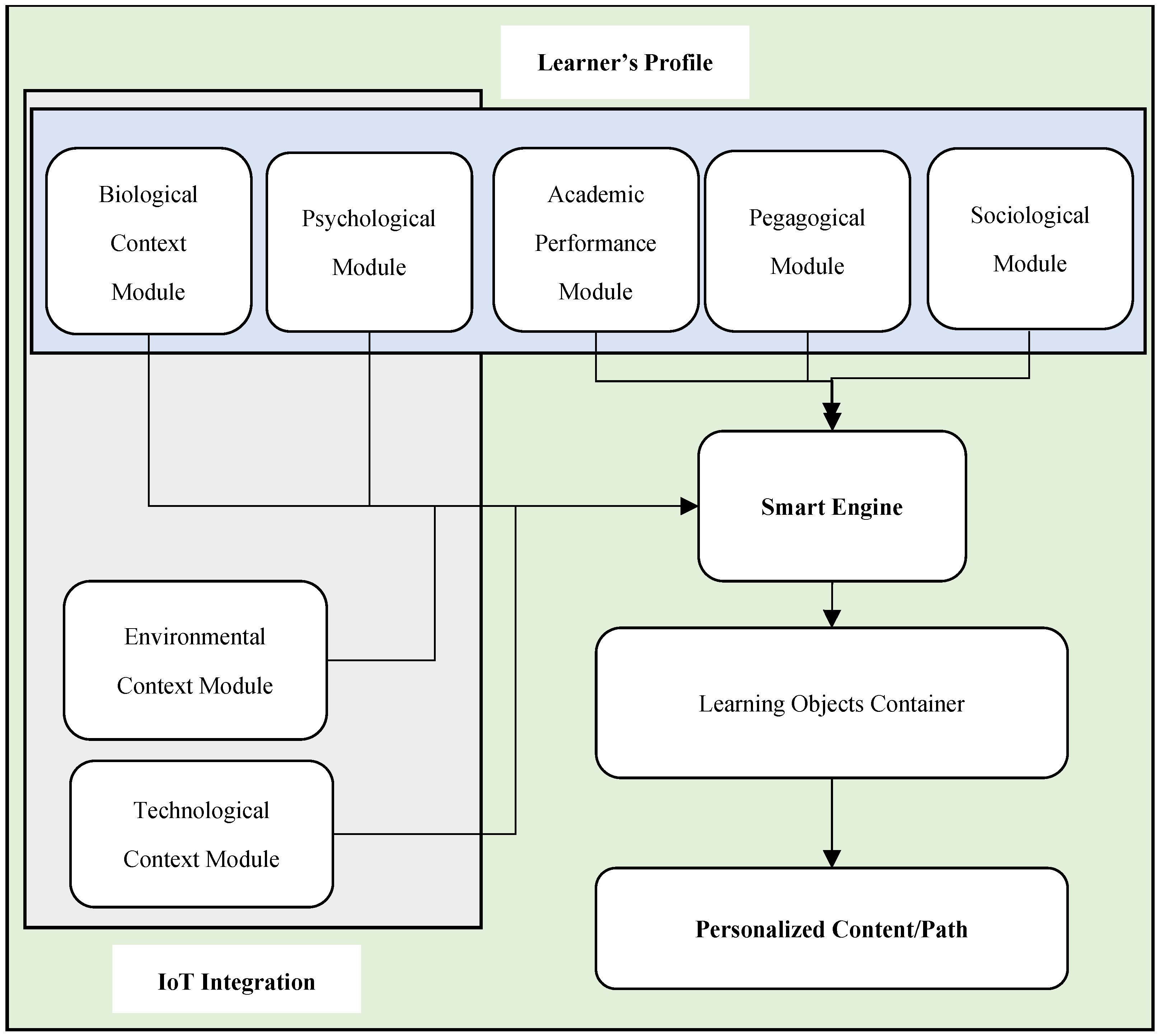

Based on the findings of this study and identified research gaps we propose a conceptual framework that takes into consideration these results and open the frontier for future research.

Figure 6.

Proposed Conceptual Model.

Figure 6.

Proposed Conceptual Model.

As learning process is a multidimensional process the proposed framework consists on different modules where each of them has different properties and fulfill different tasks to make POL as much inclusive as possible.

The main components of this framework are Learner’s Profile, IoT Integration, Smart Engine, Learning Object Container and Personalized Content. In this framework Academic Performance, Pedagogical, Psychological, Sociological and Biological Modules are integrated to gather to build an inclusive learner profile. IoT is integrated by adding Environmental and Technological modules, in addition to different personalization components added to Biological and Psychological Modules. Smart Engine collects and integrates data from Learner’s Profile and IoT Integration Modules and generate rules by using ML algorithms that are implemented to Learning Objects Container to define the content and the learning path based on the information generated by processed data. Learning Object Container defines the structure, the relationship and format and the difficulty level of Learning Objects and Learning Units. Personalized Content/Path Module provides the interface and the personalized learning service.

4.1. Learner’s Profile Modules

Main personalization parameters to construct the Academic Performance Module are Proficiency parameters (knowledge level, skills level, taken courses, level of study, test scores), Performance parameters (time spent on quizzes and assignments submission history), Interactions parameters (number exchanged messages and feedback messages) and Progress Parameters (current learning status, number of completed assignments, number of learning units).

Main personalization parameter to construct the Pedagogical Module is the Learning Style parameter measured by different Learning Style Questionnaires, based on different pedagogical and psychological theories. In addition, Learner’s Preferences (Media, language and learning speed preference) and Learning Patterns (Time of the day) are used to build the Pedagogical module.

Sociological Module includes personalization parameters of Interactions (forum interactions, engage with peers and systems, non-verbal interactions), Sociological environment (horizontal and vertical social networks) and Collaboration Patterns (No. of chats/messages/comments, participation in group projects, team working) to build the sociological profile of the learner that reflects each individual social and educational contexts.

4.2. IoT Integration Modules

Integration of IoT in existing POL systems incorporates to the system, Biological, Environmental and Technological contexts of the learner. In addition, it ads extra personalization components to Psychological and Pedagogical modules.

Learner’s Biological Context Module contains data about Hart Rate, Blood Pressure, Skin Temperature and Blood Oxygen, to infer Emotional State, Stress Level and Cognitive Ability.

Another important Module gained by IoT integration is the Environmental Components Profile which includes data about physical learning environmental conditions like temperature, sound level, location, light intensity, humidity which can be used to determine Physical Comfort, Content Format, Cognitive performance, Learning Space and Concentration.

To develop a comprehensive psychological profile of learners, a variety of personalization parameters and components can be integrated into the Psychological Module. Learner’s personality is integrated by implementing personality questionnaire, motivation towards learning content can be increased by the usage of encouraging messages and stress can be managed by implementing stress management techniques.

4.3. Smart Engine

Smart Engine is responsible to process all gathered data and generate rules to be implemented to Learning Object Container. The approach used to build the smart engine is the combination of multiple algorithms, which is one of the most commonly used approaches in POL systems. Classification algorithms are used to classify the learner’s prior knowledge, Learning Analytics are used to analyze learner’s indications, behavior and academic performance. Rule based algorithms are used to classify learner’s emotions, stress level, cognitive load and its contexts.

Core Interaction Rules in proposed framework are:

Learning Style Classification: Based on the Index of Learning Style (audio, text, video).

Knowledge Classification: Based on the accuracy of the answers provided (Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced).

Emotion Classification: Based on Learner’s Heart Rate.

Stress Level Classification: Based on Heart Rate Variability or Blood Pressure.