Our results demonstrate that in the first phase of the beta cell response to elevated glucose, glycolysis and mitochondrial OxPhos play a crucial role in generating ATP, which needs to “fill up” the cell to establish conditions necessary for beta cell function, including insulin secretion controlled by Ca2+ signaling and cataplerotic/anaplerotic fluxes in the TCA cycle. The process begins with glucose-derived pyruvate being channeled into the “clockwise” TCA cycle, generating NADH and FADH2 as energetic molecules that fuel the electron transport chain to produce ATP. This first phase, associated with the first Ca2+ pulse, culminates in a significant increase in cellular ATP, particularly in the primary ATP compartments: and . This rise in ATP inhibits the “clockwise” TCA cycle by downregulating PDH activity, shifting the TCA cycle into the “anticlockwise” direction. This shift activates PC, redirecting pyruvate into the PEP cycle, which translocates mitochondrial ATP into the microdomains () near KATP channels.

The activation of the PEP cycle represents the terminal step of the first phase and the entry into the second phase of the beta cell response to glucose stimulation. The second phase is characterized by a repetitive cycling of PEP cycle activity and OxPhos phases. This phase relies on the fine regulation of ATP production across all compartments, with the most precise regulation occurring in the microdomains (). During this phase, the cell can reduce the glycolytic flux of fresh carbon, operating in a highly energy-efficient manner to regulate insulin secretion. We provide a rough estimate of the energy cost-efficiency achieved through local ATP () regulation, demonstrating that the interplay with PEP cycling allows the cell to “reduce costs” while maintaining the signaling needed for effective insulin secretion.

3.1. Glycolytic and Mitochondrial ATP Production in the 1st Phase

In beta cells, stimulation with glucose triggers a biphasic response characterized by ATP production, Ca

2+ signaling, and insulin secretion. We emphasize that the first-phase response differs dynamically from the second-phase response. Experimental studies have shown that during the first phase, ATP production precedes the Ca

2+ response. In contrast, during the second phase, Ca

2+ dynamics take precedence over ATP production [

2]. Our model, in alignment with these experimental findings, enables detailed flux analyses and determination of the resulting concentrations.

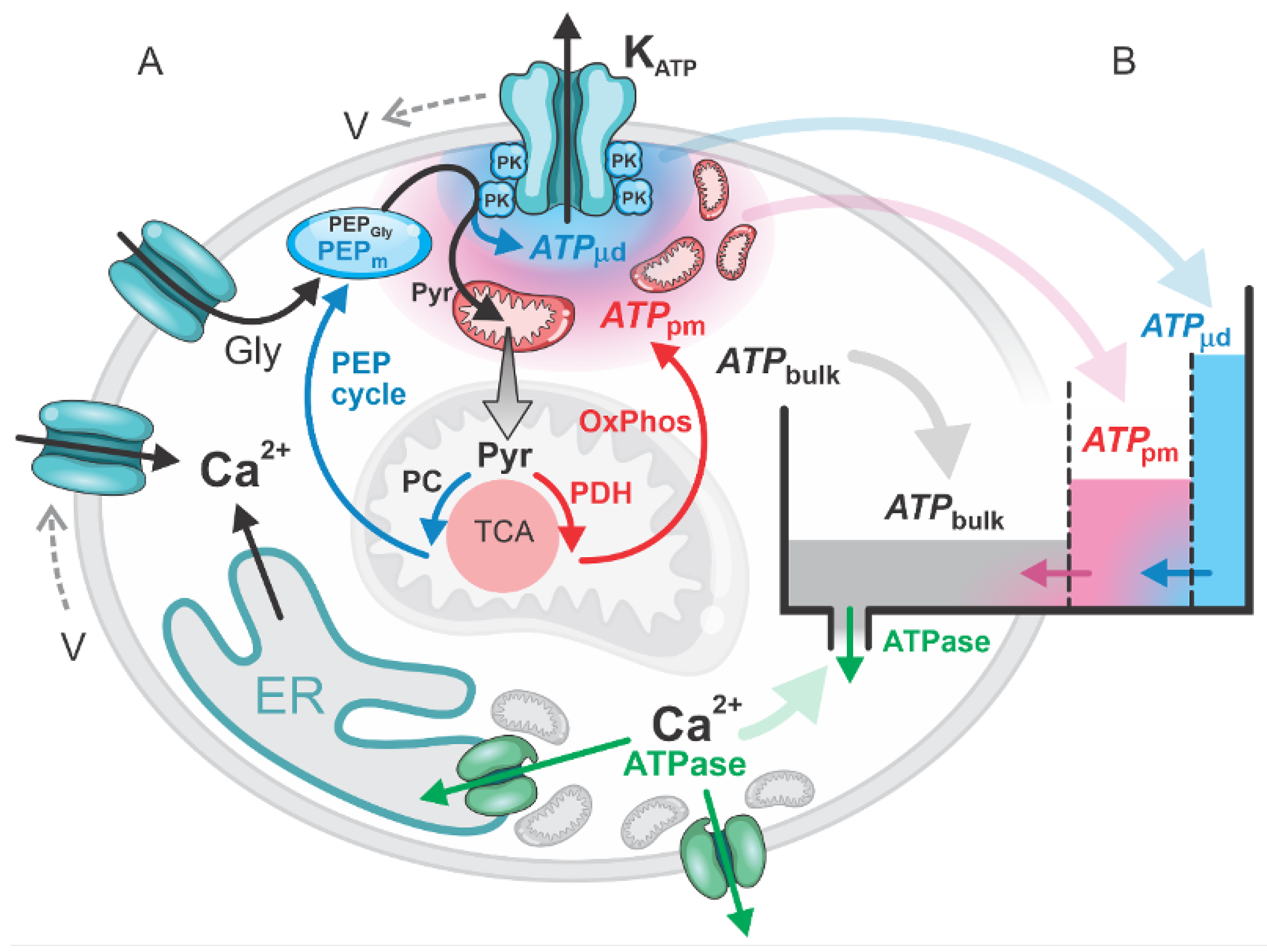

Figure 2 illustrates the interplay between ATP fluxes and Ca

2+ dynamics, specifically considering ATP production via mitochondrial OxPhos and ATP consumption by ATPases (see the central part B of

Figure 2).

At the onset of the first phase, ATP production is dominated by glycolysis and OxPhos, driven by the "metabolic push" initiated by glucose (

Figure 2A). The ATP generated from glycolytic PEP (

PEPGly) and mitochondrial OxPhos significantly exceeds the smaller contribution from mitochondrial PEP (

PEPm) production. Overall, ATP production surpasses the minimal ATP consumption by ATPases, which remain relatively inactive before the first Ca

2+ spike. This phase is characterized by glycolysis and OxPhos “pumping” ATP into the system. During this phase, glucose undergoes glycolysis and rapid oxidation, resulting in a swift rise in ATP production that contributes to a gradual increase in bulk ATP concentration (

), a more pronounced increase in subplasma membrane ATP concentration (

), and ultimately an ATP rise in the microdomains near the K

ATP channels (

). This localized ATP increase leads to the closure of K

ATP channels, triggering the first Ca

2+ spike (

Figure 2C). However, despite the rapid glycolytic ATP production and the OxPhos activity at the beginning of the first phase, the initial rise in ATP concentration within the microdomains surrounding the K

ATP channels barely reaches the threshold required to close these channels. This is due to high diffusion of ATP away from the subplasmalemmal region, where ATP concentrations are initially low (

Figure 2C).

After the first Ca

2+ spike, ATPases are activated, primarily to pump Ca

2+ into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The resulting ATP consumption causes a transient decrease in ATP concentration, which activates mitochondrial OxPhos to replenish ATP. This transition signifies the metabolic shift to the “metabolic pull” phase, where ATPase activity and Ca

2+ dynamics drive ATP production. In this phase, ATP demand activates OxPhos, pulling pyruvate into the TCA cycle to sustain ATP generation (

Figure 2B).

It is important to emphasize that following the initial closure of K

ATP channels and the first Ca

2+ spike, ATP levels first transiently decrease due to activation of ATPases but then continue to rise. The elevated ATP concentrations, combined with the gradual reduction in ATPase activity following the diminished Ca

2+ dynamics, lead to a slowdown in OxPhos and further shift the TCA cycle toward its reverse direction. This metabolic transition marks the onset of the anaplerotic phase and the upregulation of the PEP cycle. High concentrations of

PEPm drive localized ATP production, further elevating ATP levels within the microdomains surrounding the K

ATP channels (

). The localized ATP increase initiates the second Ca

2+ spike, signaling the start of the second phase (

Figure 2B).

Throughout the second phase, bulk ATP concentrations remain elevated, albeit with slight oscillations. Mitochondrial PEP cycling functions as a finely tuned mechanism, providing additional ATP on top of the already elevated subplasmalemmal ATP levels. This localized ATP production ensures that, due to the oscillatory nature of the process, ATP concentrations within the microdomains near the KATP channels () alternately reach sufficiently high levels to close the channels and trigger subsequent Ca2+ pulses.

3.2. Role of PEP Cycle and local ATP Production in the 2nd Phase

As noted in the previous section, the first phase is characterized by ATP being “

filled up” in the cell, primarily driven by a large glycolytic flux that provides a high influx of glucose-derived carbon and energy. The end products of glycolysis, PEP and pyruvate, serve as key sources of ATP: PEP is directly converted into pyruvate via PK, generating ATP locally, while pyruvate is channeled into the TCA cycle via PDH, contributing to OxPhos-driven ATP production. In contrast, the second phase is marked by a finely tuned interplay between the PEP cycle and alternating OxPhos activity. This interplay enables energy-efficient and precise regulation of K

ATP channel activity and Ca

2+ dynamics, ensuring effective beta cell function. The detailed mechanisms underlying this regulatory interplay and their implications for cellular function are explored in the following section.

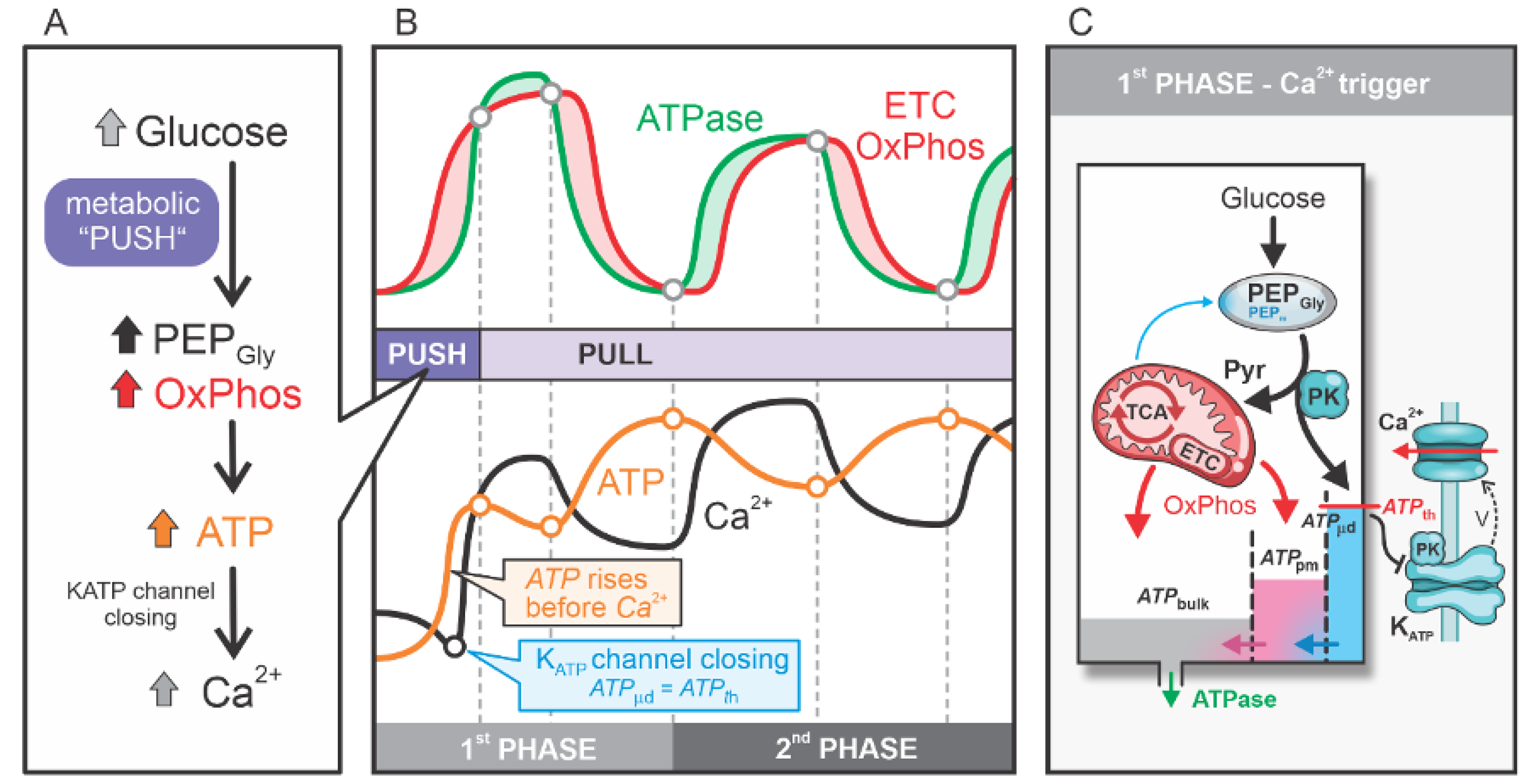

Figure 3 illustrates the ATP production dynamics in the 1

st and 2

nd phases. In

Figure 3A, the primary processes involved in these pathways are highlighted, while

Figure 3B presents an analysis of the associated flux and concentration dynamics.

The first phase of the beta cell response to high glucose corresponds to the initial Ca

2+ pulse and encompasses the metabolic pathway “

Push OxPhos”–“

Pull OxPhos”–“

Anaplerotic PEP Cycle”, denoted as steps 1-2-3 in

Figure 3A. Steps 1 (marked with grey circle in

Figure 3) and 2 (marked with a red circle in

Figure 3) are oxidative processes characterized by “

Push OxPhos” and “

Pull OxPhos”. Step 1 represents the “

metabolic push” of glucose directly driving OxPhos activity, whereas in Step 2, OxPhos is “

pulled” by high ATPase activity following the first Ca

2+ spike in the cell. By the end of Step 2, ATPase activity slows down, allowing OxPhos flux to exceed ATPase flux, leading to a rise in ATP levels. This increase in ATP slows down glycolysis and PDH activity, effectively reducing the “

clockwise” flux of the TCA cycle. This marks the transition to the step 3 (marked with a blue circle in

Figure 3) representing “

Anaplerotic PEP Cycle”, characterized by a significant pyruvate flux into the PEP cycle via PC and an increase in mitochondrial PEP flux (

) into the cytosol. The rise in cytosolic PEP, particularly near K

ATP channels, supports local ATP production via PK. This localized ATP increase

to the threshold value (

), closing the K

ATP channels and triggering a new Ca

2+ spike, marking the start of the second phase.

The second phase operates as a repetitive cycling process of “

Pull OxPhos”–“

Anaplerotic PEP Cycle” (denoted as cycling steps 2-3 in

Figure 3A). In Step 2, pyruvate enters the TCA cycle in the “

clockwise” direction via PDH, producing NADH and FADH

2, which are channeled into the electron transport chain (ETC) for ATP production. This OxPhos phase is “

pulled” by high ATPase activity, which sequesters Ca

2+ into the ER and partially removes it from the cell (

Figure 3B). At the beginning of Step 2,

and

are at their maximal levels, and

reaches the threshold value (

), triggering the Ca

2+ spike. The elevated Ca

2+ concentration immediately after the spike requires increased ATPase activity to sequester Ca

2+ into the ER and pump it out of the cell. As ATPase activity exceeds ATP production by OxPhos,

and

begin to decline (

Figure 3B). However, despite this decline,

remains above the threshold (

) throughout Step 2, supported by the high initial flux of mitochondrial PEP (

). Although

gradually decreases during Step 2, the K

ATP channels remain closed, the membrane stays depolarized, and the Ca

2+ pulse is prolonged. This is consistent with experimental data showing reduced K

ATP channel conductance under depolarized membrane conditions [

18,

19]

In Step 3, OxPhos activity surpasses ATPase activity, allowing

and

to rise, reaching their maximal levels by the end of this phase. The increased ATP concentration inhibits PDH activity and stimulates PC activity, effectively redirecting pyruvate into the “

anticlockwise” TCA cycle via PC, fueling the “

Anaplerotic PEP Cycle”. This cycle redistributes ATP from mitochondria into the microdomains near K

ATP channels, where PK activity is high. The conversion of PEP into pyruvate via PK further elevates local

. By the end of Step 3,

is sufficiently high to close the K

ATP channels, triggering a new Ca

2+ pulse and marking the return to Step 2. The repetitive cycling between Step 2 (“

Pull OxPhos”) and Step 3 (“

Anaplerotic PEP Cycle”) defines the entire second phase of the beta cell response to high glucose stimulation, as depicted in

Figure 3.

From

Figure 3, we observe that PEP production is not critically important during the first phase. Although local ATP production occurs in the microdomains near K

ATP channels, the diffusion of ATP is driven by a steep concentration gradient due to the relatively low bulk ATP concentration. Only temporarily does the ATP concentration in the microdomain reach the threshold value (

), initiating the first Ca

2+ spike. However, the cell must “

fill up” its ATP pool to a level that enables the operation of the second phase.

During the second phase, the PEP cycle plays a leading role, characterized by a “filled-up” ATP pool throughout the cell, facilitating fine-tuned local ATP production in the microdomains near KATP channels. This anaplerotic PEP cycle effectively translocates ATP from mitochondria to these microdomains, triggering Ca2+ pulses. The elevated Ca2+ concentrations subsequently activate ATPases, which reduce ATP levels. This decrease in ATP concentration, combined with high Ca2+ levels, activates PDH, enhancing TCA cycle flux and promoting OxPhos. These two processes—the anaplerotic PEP cycle and the OxPhos “pulled” by ATPases—operate in an alternating manner as long as there is sufficient carbon input (e.g., glucose).

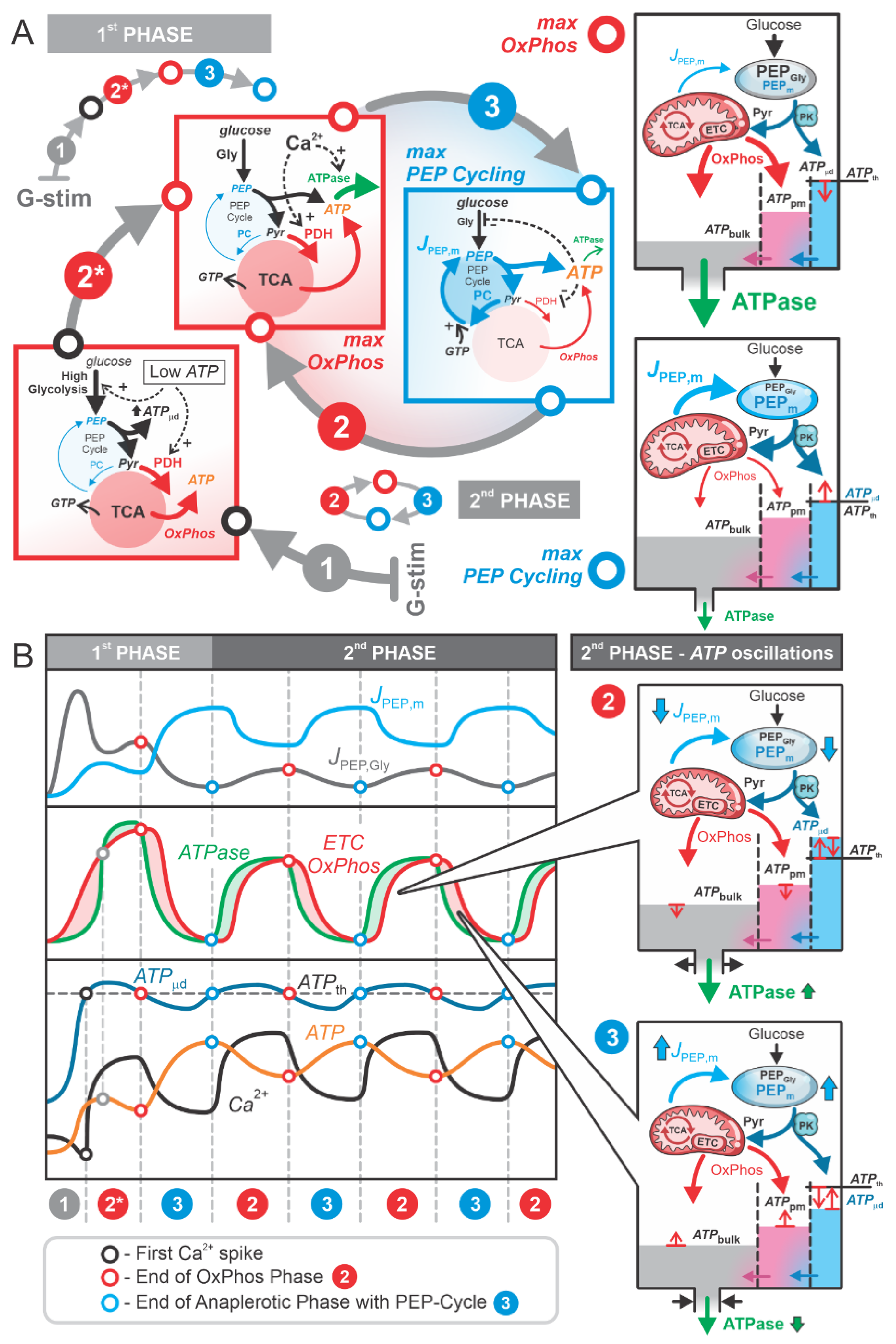

The glycolytic flux during the second phase is lower than in the first phase, as energy demands are reduced. This observation is supported by Foster et al. [

11], who demonstrated that the amplitude, duty cycle, and period of Ca

2+ oscillations increase when PC activity in mitochondria (PC2), and consequently mitochondrial PEP production, is inhibited. Inhibited PEP cycling reduces PEP delivery to the subplasmalemmal region near K

ATP channels, which slows ATP production via PK, delays the increase in

, and prolongs the time required to reach the threshold value for triggering the next Ca

2+ spike (

).

This delay implies that more time is needed to produce sufficient ATP for the subplasmalemmal ATP concentration (

) to reach the threshold value required to trigger a Ca

2+ spike (

). During this longer process, greater amounts of Ca

2+ must be released and re-sequestered, resulting in increased energy fluxes in the system. To estimate the additional power required for Ca

2+ release and re-sequestration, experimental traces of Ca

2+ oscillations from Foster et al. [

11] were analyzed.

We modeled the experimental Ca2+ traces using a modified Heaviside function:

Equation (1)

where

A is the amplitude,

T is period,

D is duty cycle (fraction of each oscillation spent in the electrically active state), and

S is parameter controlling oscillation steepness. The

function was fitted separately for the wild-type mice (WT) and mice with β-cell PCK2 deletion of PCK2 (PCK2-

KO) (

Figure 4A).

The power () required for Ca2+ handling was estimated by calculating the area under the curve (AUC) of ATPase flux for each individual oscillation using the formula:

Equation (2)

where T is the oscillation period, and represents the ATP flux () governed by the Ca2+-dependent kinetics of calcium store refilling:

Equation (3)

where

is the maximum rate of

pumping, n = 2 (cooperativity of calcium binding) and

Km = 0.5 µM (half-saturation constant) [

20].

By inserting Equation (3) into Equation (2) and calculating the relative difference between the

AUC for WT and PCK2-βKO mice, the parameter

cancels out. Thus,

can be set to an arbitrary value, and for simplicity, we set

. The calculated

AUC values were 0.78 for WT mice and 1.20 for PCK2-βKO mice (see

Figure 4B). After normalizing the

AUC values by the duration of each oscillation period (

s and

s), the power ratio between WT and PCK2-βKO mice was found to be 1:1.18. This indicates that calcium handling in PCK2-βKO mice requires approximately 18% more power, reflecting reduced efficiency compared to WT mice.

As shown in

Figure 4, the approximately 18% energy savings facilitated by the PEP cycle and localized ATP production in microdomains are critically important. While an 18% saving might seem modest, it is essential to emphasize that the second phase of the beta cell response to elevated glucose can be lasting several tens of minutes to hours [

21]. Therefore, this efficient handling of small amounts of Ca

2+ and the corresponding localized ATP elevations in microdomains play a crucial role in maintaining normal and healthy beta cell function, ensuring effective and sustained insulin secretion.

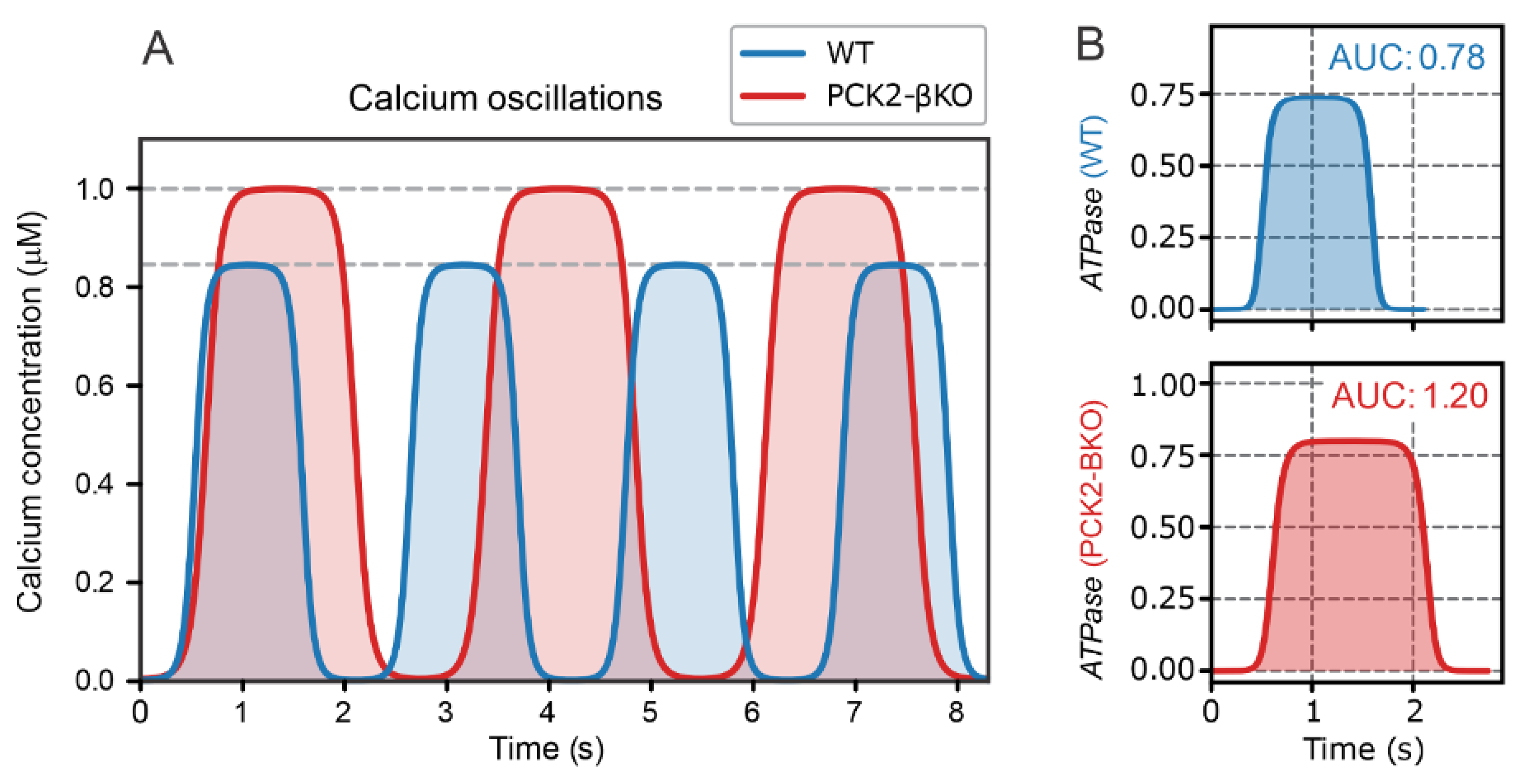

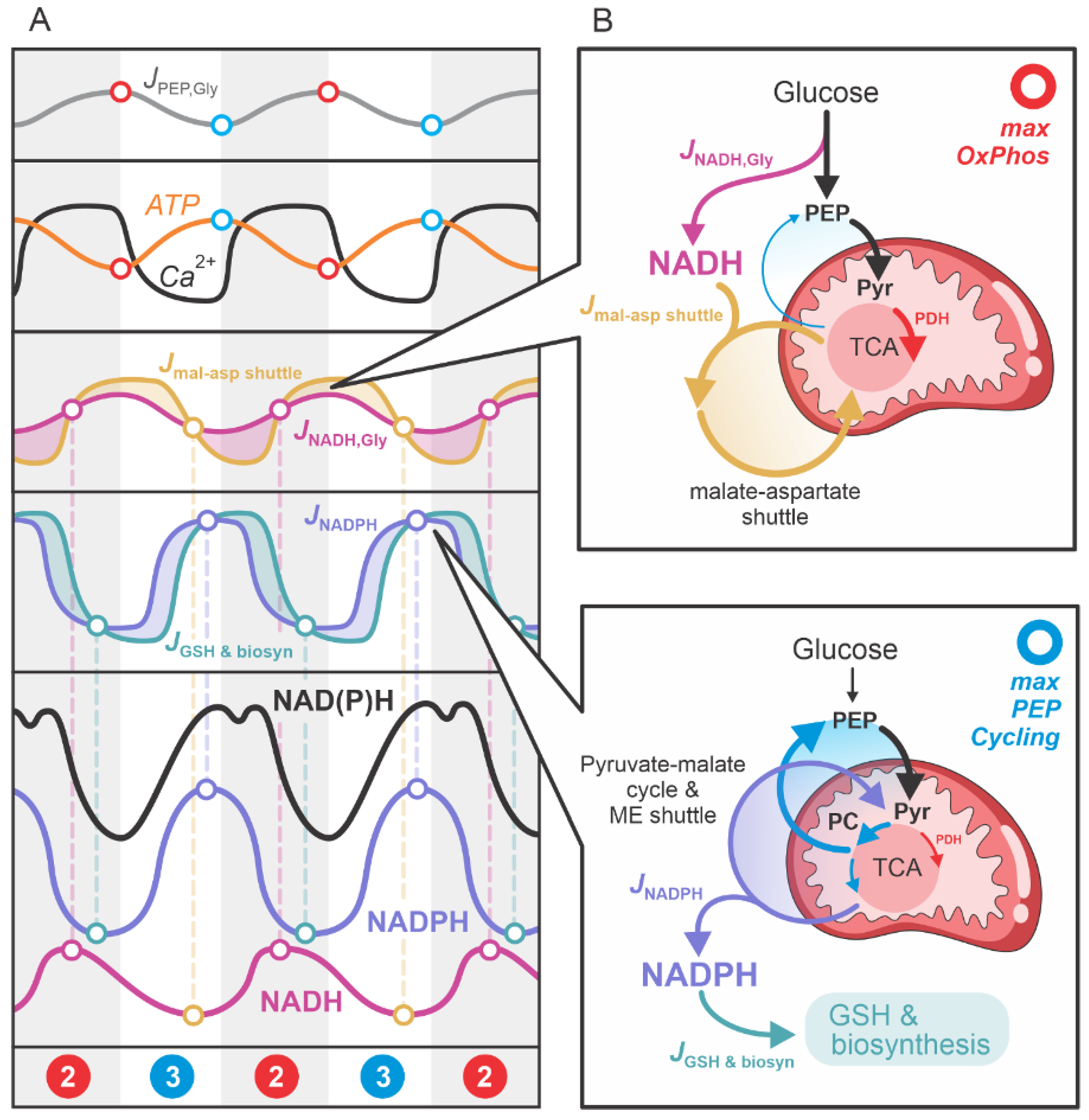

3.3. Cyclic NADH and NADPH Production in the 2nd Phase

The second phase of the beta cell response to high glucose operates as a repetitive cycling process of “

Pull OxPhos”–“

Anaplerotic PEP Cycle”, as illustrated in

Figure 3. The transition from Step 2 to Step 3 is characterized by the highest rates of OxPhos activity, denoted in red in

Figure 3. This notation is maintained in

Figure 5, where the critical features of the OxPhos phase are highlighted. During this phase, pyruvate is channeled via PDH into the “

clockwise” TCA cycle, producing NADH, which is subsequently utilized for ATP production in the ETC. Conversely, the transition from Step 3 to Step 2, denoted in blue, represents the peak activity of the PEP cycle, with pyruvate fluxing in the “

anticlockwise” TCA cycle direction via PC and feeding into the PEP cycle. The “

anticlockwise” TCA cycle direction is associated with NADPH production through several metabolic pathways linked to glucose and, in physiological conditions, glutamine metabolism. For a recent model of this metabolism in beta cells, see [

1].

One of the strengths of this model is its ability to predict the production of NADH and NADPH in stimulated beta cells. This is particularly important because experimentally it is challenging—if not impossible in most cases—to distinguish between NADH and NADPH concentrations. Experimental data are typically represented as NAD(P)H concentrations, indicating joint measurement of NADH and NADPH. In the experiments by Merrins et al. [

22], high-resolution measurements of NAD(P)H concentrations revealed an impressive “

double spike” pattern in the oscillatory traces. Our model successfully explains the “

double-spike” dynamics of NAD(P)H concentrations in stimulated beta cells.

To facilitate understanding of this process,

Figure 5 graphically illustrates the primary metabolic pathways contributing to NADH (red) and NADPH (blue) production.

Figure 5A provides a flux analysis of the main processes involved in NADH and NADPH production: NADH production by glycolysis (

); NADH transport from the cytosol to mitochondria via the malate-aspartate shuttle (

); the net NADPH influx into the cytosol (

), which includes NADPH production through the anaplerotic pyruvate-malate cycle and anaplerotically driven NADPH shuttles, primarily the malic enzyme (ME) and isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) shuttles; and the net NADPH efflux from the cytosol (

), which accounts for NADPH usage in glutathione (GSH) synthesis and other biosynthetic processes. These fluxes vary significantly over time, resulting in oscillatory NADH and NADPH concentrations. The phase difference between these oscillations explains the experimentally observed “

double-spike” patterns in the NAD(P)H traces of activated beta cells.

To better understand the temporal dynamics of the main fluxes contributing to the cytosolic concentrations of NADH and NADPH,

Figure 5B presents the fluxes

,

,

, and

in relation to the primary glycolytic input flux and the TCA cycle fluxes. During the maximum OxPhos phase, the glycolytic flux is high, and the resulting pyruvate is primarily directed via PDH into the oxidative “

clockwise” TCA cycle. Glycolytic NADH production is elevated, and the NADH is shuttled into mitochondria through the malate-aspartate shuttle.

As NADH is converted to ATP and cytosolic ATP levels rise, glycolysis is inhibited. Additionally, elevated ATP levels inhibit PDH and activate PC, progressively shifting the TCA cycle toward the “anticlockwise” direction, including the PEP cycle. This anaplerotic phase generates NADPH through the pyruvate-malate cycle and facilitates NADPH transport from mitochondria to the cytosol via the ME and IDH shuttles. Concurrently, NADPH is utilized for antioxidative processes, such as GSH synthesis, and other biosynthetic pathways.