1. Introduction

Oral and oropharyngeal cancer (OC) is the 6th most common cancer globally, and the only major cancer whose outcomes continue to worsen. While this situation is in part related to the rising global prevalence of HPV, the primary barrier to better outcomes remains unchanged: late diagnosis and delayed treatment [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. While OC treatment outcomes are good when the condition is diagnosed at an early stage, morbidity and mortality are high for later-stage lesions [

6,

7,

8,

9].

The majority of oral cancers are presumed to develop from oral potentially malignant lesions (OPML)[

10]. These lesions typically can be detected by visual inspection during screening. However, differentiating OPML from benign lesions can be challenging, and existing tools are unable to predict malignant change in premalignant lesions, which require regular monitoring to ensure early detection of any progression towards malignancy. The typical pathway to care for an individual with an oral lesion presents unusual challenges that all constitute barriers to early diagnosis and treatment. Persons from low resource, minority, and underserved (LRMU) populations carry the highest OC risk [

6,

7,

8,

9,

11]. Unfortunately, these populations have limited access to regular dental and medical care, so that they are not routinely screened for OC risk [

11]. Dentists and hygienists are mandated to screen routinely for OC risk at every visit. This screening step is essential, because it is a positive risk screening outcome that triggers specialist referral for surgical biopsy, diagnosis and either treatment or heightened monitoring. Even when individuals from LRMU populations have access to screening, their compliance with specialist referrals are constrained by challenges that include cost, fear, unfamiliarity with specialist and academic centers, family care duties, lack of transportation, language barriers and cultural barriers [

12,

13]. Thus, specialist referral compliance from these individuals is typically low for all branches of medicine, ranging from 18-55% [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

A recent study in an LRMU population of individuals who had screened positive for increased OC risk reported that 83% of individuals complied with a Telehealth OC specialist referral within 6 months, whereas only 30% of subjects complied with an in-person specialist referral. Of the individuals who attended the first specialist appointment, approx. 85% then attended a second follow-up in-person specialist visit, so that, after 6 months, 72.5% of Telehealth subjects had entered into the continuum of care vs. 25% of individuals who had opted for the initial in-person specialist visit [

19].

Studies in other areas of medicine have confirmed the value of Telehealth in overcoming barriers to care. This field of research was greatly expanded during the COVID-19 epidemic [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. For example, in one pediatric study in a low-resource setting (LRS), investigators found that in-person specialist referral compliance increased by a factor of 3 after a preceding remote visit with the specialist [

28]. While Telehealth has the potential to overcome many of the greatest barriers to improving OC outcomes, its implementation in the field of oral health remains limited. One extensive systematic review reported that, even when Telehealth is employed in the OC realm, an asynchronous communication mode is typically used. Unfortunately this indirect form of communication forfeits most of the benefits of Telehealth [

29].

Our overall hypothesis is that providing a remote option for the first specialist visit can overcome many of the critical barriers to compliance. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a remote intraoral camera-based Telehealth platform prototype in improving access to OC specialists in LRMU patients suspicious of OPML. Specific aims included: (a) compare patient compliance with in-person vs. Telehealth specialist referral, (b) determine the efficacy and ease of use of a remote specialist intra-oral examination. The long-term goal is to improve specialist referral compliance for LRMU individuals with increased OC risk, to ensure better and more equitable health outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This project was conducted in full compliance with University of California Irvine’s IRB-approved protocol #2002-2805; and by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania, under protocol # 855247. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, all of whom completed the study in accordance with the approved protocol.

2.1. Subjects

Forty subjects who had screened positive for OPMLs at Concorde College of Dental Hygiene in Garden Grove, CA, West Coast University Dental Hygiene Clinic in Anaheim, CA, and the University of California, Irvine’s Clinics were recruited. Subject demographics are shown in

Table 1.

2.2. Protocol

After completing the in-person standard OC risk screening, patients with a positive screening outcome for OPMLs were provided full details about this study and asked whether they would like to participate. Individuals were told that non-participation would not affect their treatment in any way. Those who opted into the study provided written informed consent. Using identical language each time, subjects were asked to indicate whether they preferred conventional referral to an in-person specialist, or a Telehealth in-home visit with the specialist. Subjects were told that neither form of specialist visit would incur any costs for them. Individuals who had chosen the Telehealth option were given a return appointment at the community clinic for a remote specialist visit that included the services of an interpreter as needed. Individuals who had selected the in-person specialist visit were asked to select a specialist from the list of providers to the clinics participating in this study. Subjects were offered whatever assistance they needed at no cost to them, including family care, transportation, an interpreter to accompany them on their specialist visit and the ability to bring one support person such as a family member or friend with them to the appointment.

2.3. Telehealth Specialist Visit

The Telehealth visit was completed in the community clinic. Staff noted travel time to and from the clinic for each subject, as well as instruction and Telehealth visit durations. They also recorded any assistance that the subject received with regard to transportation, family care and interpreter services. Next, the research staff briefly showed the subject how to operate the Telehealth system, and after that timepoint, they only assisted the subject if absolutely necessary. Researchers recorded how many such interventions were necessary, and the reason for them. During the remote specialist inspection, the patient moved the intra-oral camera wand around the oral cavity according to instructions over the smartphone from the remote oral medicine specialist. The remote visit continued until a full 8-point visual examination of the mouth had been completed. Patients who were non-compliant with the first scheduled remote specialist visit received a weekly text message or phone call reminder encouraging them to reschedule. Communications and compliance were recorded throughout the study.

2.4. Telehealth System

The HIPAA-compliant prototype Telehealth system utilized in this study consists of a prototype intraoral camera, a computer tablet with Wi-Fi connection, and a bridging application (app). The app consists of two components: (1) an app that is installed on the study tablet that allows a patient to view their oral cavity on the screen display; and (2) a partner app that is installed on the remote specialist’s computer that automatically interfaces with Zoom, allowing for secure synchronous viewing of the patient’s oral cavity, as well as the ability to capture still and video images during use.

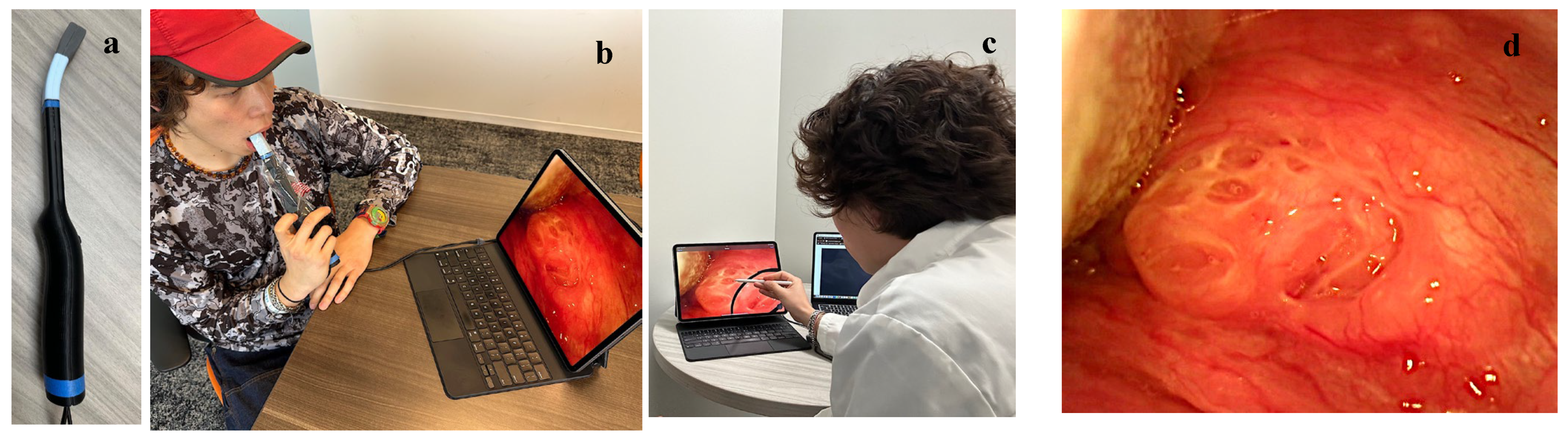

Figure 1 shows the prototype Telehealth system and its usage. The intraoral camera has a unique 180-degree flexible neck, enabling it to be adjusted for optimal viewing of all areas of the mouth and the tonsils. It also features autofocus functionality with a long focal range, allowing for imaging access to the entire oral cavity, including the tonsillar pillars, floor of mouth, posterior buccal and all palatal regions while minimizing contact with oral tissues to avoid triggering the gag reflex.

The prototype Telehealth system (

Figure 1a) was designed to integrate seamlessly with the Zoom Telehealth app for ease of use for both the patient and remote specialist. For each Telehealth session, the remote specialist initiated contact with the patient using Zoom. This triggered a notification on the study tablet instructing the patient to accept the call, thus establishing the connection between the intraoral camera, study tablet, and screen sharing with the specialist. Prior to each use of the intraoral camera, a disposable sterile sheath was applied. During each remote visit, the specialist provided verbal instructions to the patient regarding probe placement and angulation as they completed a full intra-oral visual examination (

Figure 1b). The specialist was able to capture still images and/or record video footage throughout the call, similar to any standard Zoom Telehealth call (

Figure 1 c,d). After the remote session, patients rated the Telehealth platform’s ease of use and their satisfaction with the Telehealth experience on a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0-10. Subjects were also asked to indicate their preference between Telehealth appointments versus in-person consultations for future appointments. (Yes/No)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Study data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc. Boston, MA 02110). A Fisher exact test was used to compare the proportions of subjects who showed compliance, with p < 0.05 set as the level of significance.

3. Results

Twenty-four subjects opted for a Telehealth specialist visit, and sixteen chose to attend an in-person specialist appointment. The demographics of the two study groups were comparable (

Table 1). Approximately 2/3 of subjects in each group were non-native English speakers. Interestingly, 67% of females opted for Telehealth visits vs. 56% of males, and the mean age of the remote specialist group was 5 years older than that of the in-person visit group.

Of the 24 subjects who requested a Telehealth visit, 7/24 requested an interpreter, 24/24 said they would bring a family member for support, 2/24 requested assistance with family care and 8/24 requested transportation to and from the community clinic. Sixteen were non-native English speakers. The 20/24 subjects who actually attended their Telehealth visit spent an average of 26 minutes each way traveling to the community clinic, 4 minutes learning how to use the Telehealth system, and 28 minutes on the Telehealth call. Their mean score for Telehealth ease of use was 8.1/10 and mean overall satisfaction with the Telehealth visit scored 8.7/10 (

Table 2), which is significantly better (p=0.0116) than the 6.9/10 patient satisfaction with the in-person visit. All subjects in the Telehealth group were able to operate the intraoral camera and the zoom Telehealth App satisfactorily. Specialists were also able to complete a full intra-oral inspection in all patients. Two individuals required some help from the clinic assistant to initiate the zoom meeting.

Ten of sixteen individuals who requested an in-person specialist visit were non-native English speakers. Six of them requested an interpreter, all 16 indicated that they would bring a family member to the office visit, 2 requested assistance with family care and 11 needed transportation to the in-person appointment. Travel time to the specialist’s office averaged 67 minutes each way and on average the office visit lasted 26 minutes. Subjects’ mean overall satisfaction with the in person visit scored 6.9/10 (

Table 2).

In the Telehealth group, 16/24 subjects attended the first scheduled remote specialist visit; 4/24 attended rescheduled visits within 3 months, and 4/24 did not comply at all. Of the 7/16 subjects who completed the in person visit, 3/16 attended the first scheduled visit, 4/16 complied within 3 months. 9/16 did not comply at all with specialist referral (

Table 3).

67.5% of subjects complied with any form of specialist referral within 3 months. Initial compliance (attending the first scheduled visit) was significantly better in the Telehealth group: 66.7% vs 18.6%. Three-month referral compliance was also significantly better in the Telehealth group: 83.3% vs. 43.6%. (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

The premise of this study is that, if specialist access by LRMU individuals with increased OC risk can be improved, outcomes will also benefit. The fact that OC outcomes are especially poor in this high-risk group with little specialist access adds further urgency to finding a scalable solution to this challenge.

The first step in the pathway to OC management is non-specialist screening for OC risk, typically by dentists or hygienists who are mandated to complete a risk assessment during office visits. Unfortunately, conventional screening is only 40-60% accurate [

30,

31]. Various technologies and approaches are being developed and evaluated to overcome this first barrier in the pathway to care, some with very promising results. However, improved screening and triage will only translate into better OC outcomes if patients who screen positive have a workable pathway to specialist access and utilize it. Because most OC specialists are situated in academic or hospital centers in large cities, accessing them can be arduous, costly and daunting, especially for individuals who are not familiar with such settings.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Telehealth emerged as an important modality for providing healthcare to patients [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Mandate-compliant communication, record-keeping and reimbursement pathways were also developed and validated. It is on this foundation that the current study is based, with the goal of identifying a viable pathway to bridge the gap from screening to specialist diagnosis and subsequent management in LRMU individuals with increased OC risk.

Participants were asked to select the specialist visit option of their choice, rather than being randomized to the in person or the remote option, in order to identify which form of specialist visit patients prefer, and to maximize the potential for referral compliance. Interestingly, older patients did not prefer the in-person option to a greater extent than younger study participants. The mean age of the Telehealth group was 5 years greater than that of the in-person group. The 4 oldest subjects in this study all opted for a remote specialist visit. Thus, pre-study concerns that permitting patients to choose their specialist visit mode might result in a much younger population in the Telehealth group were unfounded. These results are in agreement with the findings of some other studies that also reported a slight preference for Telehealth amongst older individuals [

32,

33]. Perhaps older individuals are more reluctant to leave their home and travel long distances, especially when most of them use cellphones on a daily basis [

34]. In this study, the travel time to the in-person specialist appointment was more than twice as long as to the Telehealth appointment, which may well have served as a deterrent to completion of the in-person visit. Other studies have reported that barriers in patient confidence [

35,

36,

37], as well as a low ability to use telemedicine, lack of literacy, lack of assistance from others, and also physical and cognitive disabilities may contribute to reduced acceptance of Telehealth modalities by the elderly [

35,

36,

37]. In this study, the design of the prototype Telehealth technology and its usage were specifically tailored to overcome some of these potential hurdles: by situating the Telehealth visit in a local and familiar community location, subjects were less anxious. They could be shown how to use the technology by staff and helped as needed. Moreover, patients were encouraged to bring a friend or family member to the Telehealth visit to assist as needed and to reduce anxiety, and a translator was readily available to assist with any language barriers.

Most study participants were not native English speakers. Because a very similar percentage of each group (66.7% vs 62.5%) fell into this category, the potential effect of this variable on patient conduct was considered minimal.

Twice as many individuals from a low-resource population selected the Telehealth option vs. the in-person specialist visit despite all of the potential and perceived barriers to remote care. This finding supports the premise that Telehealth can be implemented, and indeed is welcomed, in all sectors of low-resource populations, independent of age or other demographics. This finding is supported by a broader analysis of Telehealth adoption. For example, a New York Times (NYT) article reports that nine million people under Medicare alone used telemedicine services during the early months of the [COVID-19] crisis [

38]. Early data does not show wide variations in use by race or ethnicity [

39]. In addition to federal spending through Medicare, nearly USD 4 billion was billed nationally for Telehealth visits during March and April, compared to less than USD 60 million for the same two months of 2019 [

39].

Overall referral compliance varied significantly between the 2 modes of specialist visit. Only 18.6% of subjects attended the first in-person specialist visit, and 43.6% of individuals in this group complied with referral within 3 months. In the in-person appointment group, 66.7% of patients attended their first Telehealth visit, and 83.3% completed their Telehealth specialist visit within 3 months. The considerable difference in compliance between the 2 groups is similar to that reported from an earlier study in another low-resource population [

19]. Furthermore, in that study approximately 85% of individuals who complied with either form of first visit subsequently complied with a second in-person specialist visit for entry into the pathway of care. That finding underlines the importance of tailoring the first specialist visit to the individual needs of the patient who is undergoing specialist referral, as it appears that a successful first specialist visit provides the basis for excellent compliance with in-person follow-up appointments and entry into the pathway of care. As oral cancer outcomes are primarily determined by cancer stage at time of diagnosis, and an increase in the time up to treatment of as little as 2 months significantly increases risk of death [

4,

40], better compliance with specialist referral can serve as a powerful tool to address the inequitably high morbidity and mortality that are experienced by individuals in low-resource settings [

41,

42,

43,

44].

While this study was carefully designed to achieve its stated goals, it had several weaknesses. Because subjects were permitted to choose their desired form of specialist visit, group sizes were not comparable and there may have been bias in subjects’ compliance and behavior. The decision was made to allow subjects to follow their preference, because this approach parallels current practice in many areas of medicine. Patients are now routinely offered the choice between in-person and Telehealth visits in many spheres of medical care, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the Telehealth protocol followed in this study during the remote specialist visits parallels the process as we envisage it in future use in community settings.

Another issue that merits further investigation is the role that regular reminder communications and the provision of child/elder care, transportation and interpreters may have played in promoting referral compliance. Larger randomized studies that address these variables are now under way to further explore these questions.

5. Conclusions

A novel, community-based Telehealth platform may improve specialist referral compliance in individuals from low resource settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization (AL, DM, RL, PWS), methodology (TT, AA, WD, CD, DM, AL, AH, PWS) software (CD, AA, WD, RL), validation (PWS, AL, DM, AC) formal analysis (TT), investigation, resources (CW, PWS), data curation (CW, PWS), writing original draft preparation (AH, AL, PWS)—, writing—review and editing (AH, AL, DM, RL, TT, PWS), visualization (WD, CD, AA, PWS), supervision (CW, AA, PWS), project administration (CW, AA,PWS), funding acquisition (RL, PWS). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

TRDRP T31IR1825: NCRR NCATS NIH UL1 TR0001414; NIH UH3EBO22623; NIHRO1DE030682; R44CA265514; R01DE030682; University of California, Irvine Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program; The Bach Fund Award from the University of Pennsylvania, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center (PPMC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of California, Irvine, under protocol #2002-2805; and by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania, under protocol # 855247.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results may be available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Stathopoulos P, Smith WP. Analysis of survival rates following primary surgery of 178 consecutive patients with oral cancer in a large district general hospital. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2017, 16, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massano J, Regateiro FS, Januário G, Ferreira A. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: review of prognostic and predictive factors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006, 102, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragin CCR, Modugno F, Gollin SM. The epidemiology and risk factors of head and neck cancer: a focus on human papillomavirus. J Dent Res. 2007, 86, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.T.; Galloway, T.J.; Handorf, E.A.; Egleston, B.L.; Wang, L.S.; Mehra, R.; Flieder, D.B.; Ridge, J.A. Survival Impact of Increasing Time to Treatment Initiation for Patients with Head and Neck Cancer in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGurk, M.; Chan, C.; Jones, J.; O’Regan, E.; Sherriff, M. Delay in Diagnosis and Its Effect on Outcome in Head and Neck Cancer. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2005, 43, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, C.E.; de Jong, J.D.; Verheij, R.A.; Jansen, T.; Korevaar, J.C.; de Bakker, D.H. Compliance with Referrals to Medical Specialist Care: Patient and General Practice Determinants: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckard, G.J.; Borkowski, N.; Diaz, D.; Sanchez, C.; Boisette, S.A. Improving Timeliness and Efficiency in the Referral Process for Safety Net Providers: Application of the Lean Six Sigma Methodology. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2010, 33, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, C.B.; Shadmi, E.; Nutting, P.A.; Starfield, B. Specialty Referral Completion among Primary Care Patients: Results from the ASPN Referral Study. Ann. Fam. Med. 2007, 5, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Highlights Oral Health Neglect Affecting Nearly Half of the World’s Population. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/18-11-2022-who-highlights-oral-health-neglect-affecting-nearly-half-of-the-world-s-population (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson NW, Waal IVD. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa J Oral Pathol Med 2007, 36, 575–580.

- Conway DI, Petticrew M, Marlborough H, Berthiller J, Hashibe M, Macpherson LM. Socioeconomic inequalities and oral cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Int J Cancer. 2008, 122, 2811–9.

- Patel MP, Schettini P, O’Leary CP, Bosworth HP, Anderson JB, Shah KP. Closing the Referral Loop: An Analysis of Primary Care Referrals to Specialists in a Large Health System. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widdifield J, Bernatsky S, Thorne JC, Bombardier C, Jaakkimainen RL, Wing L, Paterson JM, Ivers N, Butt D, Lyddiatt A, et al. Wait Times to Rheumatology Care for Patients with Rheumatic Diseases: A Data Linkage Study of Primary Care Electronic Medical Records and Administrative Data. Can. Med. Assoc. J. Open 2016, 4, E205–E212. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, T.; Kadakia, N.; Aribo, C.; Gochi, A.; Kim, G.Y.; Solomon, N.; Molkara, A.; Molina, D.C.; Plasencia, A.; Lum, S.S. Compliance with Surgical Oncology Specialty Care at a Safety Net Facility. Am. Surg. 2021, 87, 1545–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguet, C.; Gilchrist, V.; McCord, G. The Consultation and Referral Process. A Report from NEON. Northeastern Ohio Network Research Group. J. Fam. Pract. 1998, 46, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vukmir, R.B.; Kremen, R.; Dehart, D.A.; Menegazzi, J. Compliance with Emergency Department Patient Referral. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1992, 10, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglam-Aydinatay, B.; Uysal, S.; Taner, T. Facilitators and Barriers to Referral Compliance among Dental Patients with Increased Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2018, 76, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S.R.; Ades, P.A.; Thompson, P.D. The Role of Cardiac Rehabilitation in Patients with Heart Disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 27, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen J, Takesh T, Parsangi N, Song B, Liang R, Wilder-Smith P. Compliance with Specialist Referral for Increased Cancer Risk in Low-Resource Settings: In-Person vs. Telehealth Options. Cancers. 2023, 15, 2775.

- Weiner, M.; El Hoyek, G.; Wang, L.; Dexter, P.R.; Zerr, A.D.; Perkins, A.J.; James, F.; Juneja, R. A Web-Based Generalist–Specialist System to Improve Scheduling of Outpatient Specialty Consultations in an Academic Center. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanti, R.M.; Stoopler, E.T.; Weinstein, G.S.; Newman, J.G.; Cannady, S.B.; Rajasekaran, K.; Tanaka, T.I.; O’Malley, B.W.; Le, A.D.; Sollecito, T.P. Considerations in the Evaluation and Management of Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders during the COVID -19 Pandemic. Head Neck 2020, 42, 1497–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.; Yang, S.; Melnikova, A.; Abouakl, M.; Lin, K.; Takesh, T.; Wink, C.; Le, A.; Messadi, D.; Osann, K.; et al. Novel Approach to Improving Specialist Access in Underserved Populations with Suspicious Oral Lesions. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haydon, H.M.; Caffery, L.J.; Snoswell, C.L.; Thomas, E.E.; Taylor, M.; Budge, M.; Probert, J.; Smith, A.C. Optimising Specialist Geriatric Medicine Services by Telehealth. J. Telemed. Telecare 2021, 27, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guzman, K.R.; Caffery, L.J.; Smith, A.C.; Snoswell, C.L. Specialist Consultation Activity and Costs in Australia: Before and after the Introduction of COVID-19 Telehealth Funding. J. Telemed. Telecare 2021, 27, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, D.; Hope, K.D.; Arthur, L.C.; Weinberger, S.M.; Ronai, C.; Johnson, J.N.; Snyder, C.S. Telehealth for Pediatric Cardiology Practitioners in the Time of COVID-19. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2020, 41, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doraiswamy, S.; Abraham, A.; Mamtani, R.; Cheema, S. Use of Telehealth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e24087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNicola, N.; Grossman, D.; Marko, K.; Sonalkar, S.; Butler Tobah, Y.S.; Ganju, N.; Witkop, C.T.; Henderson, J.T.; Butler, J.L.; Lowery, C. Telehealth Interventions to Improve Obstetric and Gynecologic Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrest, C.B.; Glade, G.B.; Baker, A.E.; Bocian, A.; von Schrader, S.; Starfield, B. Coordination of Specialty Referrals and Physician Satisfaction with Referral Care. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000, 154, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgel-Juarez, N.; Torres-Pereira, C.; Haddad, A.E.; Sheehy, L.; Finestone, H.; Mallet, K.; Wiseman, M.; Hour, K.; Flowers, H.L. Accuracy and Effectiveness of Teledentistry: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Evid.-Based Dent.

- Sardella A, Demarosi F, Lodi G, Canegallo L, Rimondini L, Carrassi A. Accuracy of referrals to a specialist oral medicine unit by general medical and dental practitioners and the educational implications. J Dent Educ. 2007, 71, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein JB, Güneri P, Boyacioglu H, Abt E. . The limitations of the clinical oral examination in detecting dysplastic oral lesions and oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012, 143, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen N, Liu P. Assessing Elderly User Preference for Telehealth Solutions in China: Exploratory Quantitative Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022, 10, e27272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepu ́lveda-Loyola W, Rodr ́ıguez-Sa ́nchez I, Pe ́rez-Rodr ́ıguez P, et al. Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on health in older people: mental and physical effects and recommendations. J Nutr Health Aging 2020, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/489255/percentage-of-us-smartphone-owners-by-age-group/.

- Hawley CE, Genovese N, Owsiany MT, et al. Rapid integration of home telehealth visits amidstCOVID- 19: what do older adults need to succeed? J Ame Geri Soc 2020, 68, 2431–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips NA, Chertkow H, Pichora-Fuller MK, et al. Special issues on using the montreal cognitive assessment for telemedicine assessment during COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020, 68, 942–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg N, Schumann M, Kraft K, et al. Telemedicine and telecare for older patients - a systematic review. Maturitas Elsevier Ireland Ltd 2012; 73: 94–114.

- New York Times. “Is TeleMedicine Here to Stay?”. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/03/health/covid- telemedicine-congress.html (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- FAIR Health Study Analyzes Telehealth. Available online: https://www.fairhealth.org/article/fair-health-study-analyzes- Telehealth (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Agarwal, A.K.; Sethi, A.; Sareen, D.; Dhingra, S. Treatment Delay in Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancer in Our Population: The Role of Socio-Economic Factors and Health-Seeking Behaviour. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 63, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, S. Early Diagnosis of Oral Cancer. Cancer 1988, 62, 1796–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, S., Jr.; Gorsky, M.; Lozada, F. Oral Leukoplakia and Malignant Transformation. A Follow-up Study of 257 Patients. Cancer 1984, 53, 563–568. [Google Scholar]

- Alston, P.A.; Knapp, J.; Luomanen, J.C. Who Will Tend the Dental Safety Net? J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 2014, 42, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, P.C.; Mehta, F.S.; Daftary, D.K.; Pindborg, J.J.; Bhonsle, R.B.; Jalnawalla, P.N.; Sinor, P.N.; Pitkar, V.K.; Murti, P.R.; Irani, R.R.; et al. Incidence Rates of Oral Cancer and Natural History of Oral Precancerous Lesions in a 10-Year Follow-up Study of Indian Villagers. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1980, 8, 287–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).