Submitted:

01 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

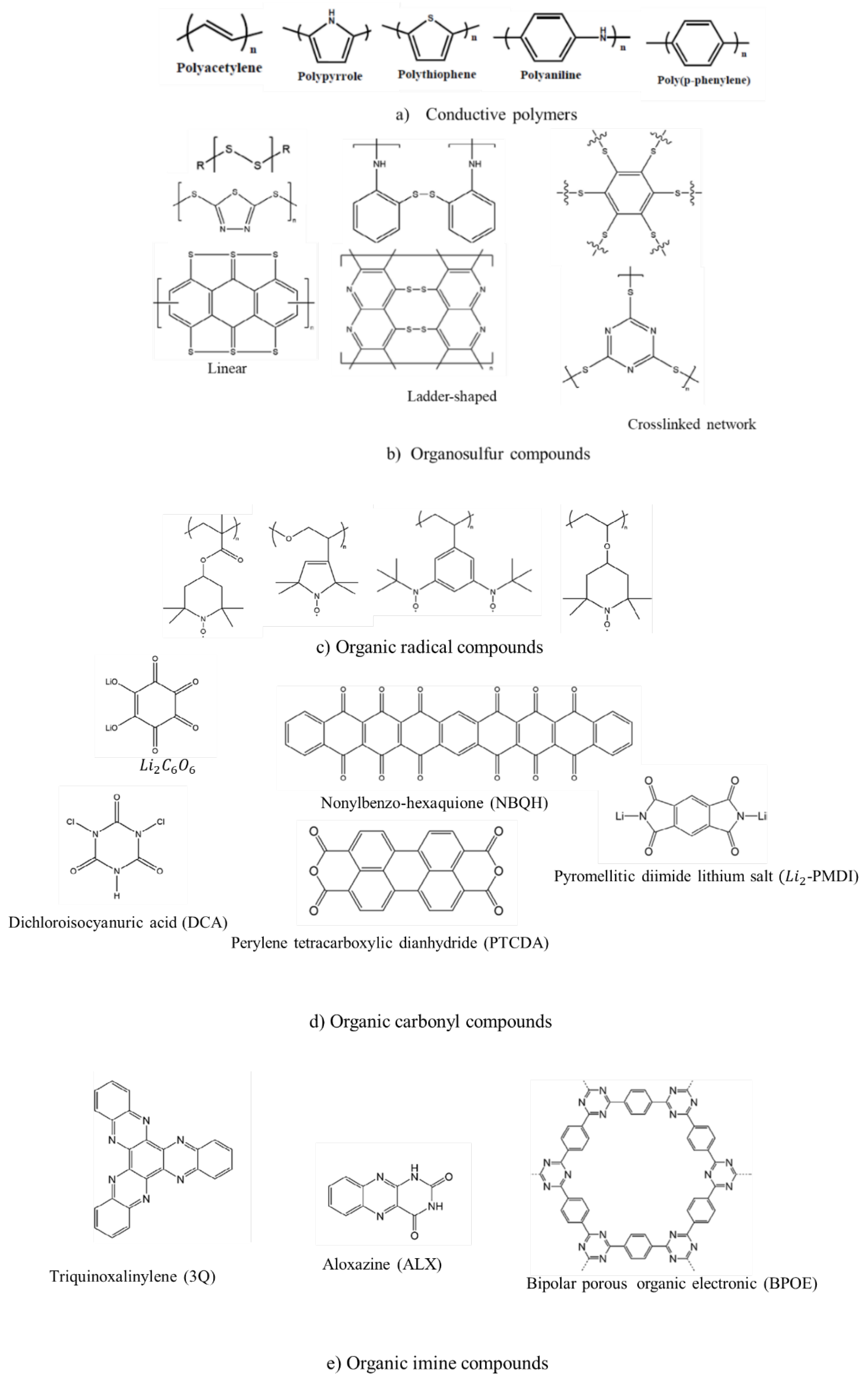

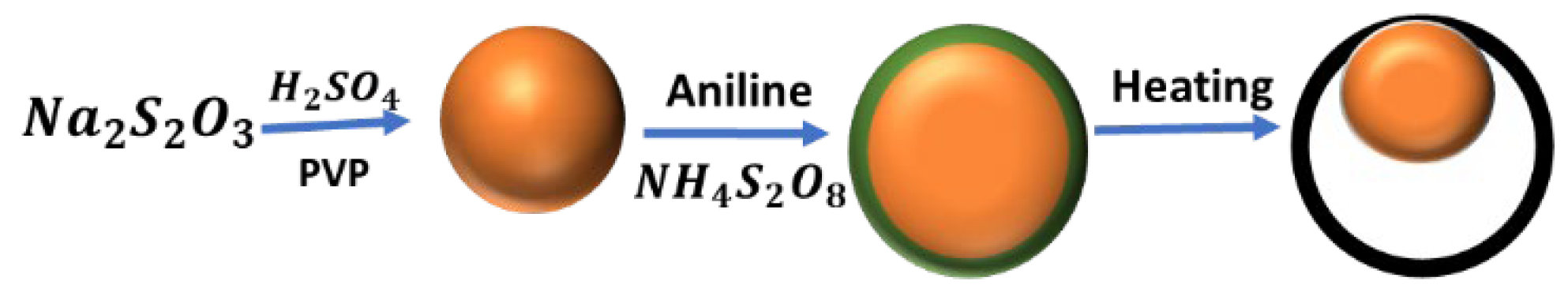

Organic materials have emerged as promising candidates for cathode materials in lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitors, offering unique properties and advantages over traditional inorganic counterparts. This review explores the utilization of organic compounds as cathode materials in energy storage devices, focusing on their application in lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitors. The review looks into various types of organic materials, organosulfur compounds, organic free radical compounds, organic carbonyl compounds, conducting polymers, and imine compounds. The advantages, challenges, and ongoing developments in this field are explored, highlighting the potential of organic cathode materials in achieving higher energy density, improved cycling stability, and environmental sustainability. The comprehensive analysis of organic cathode materials provides insights into their electrochemical performance, electrode reaction mechanisms, and design strategies such as molecular structure modification, hybridization with inorganic components, porous architectures, conductive additives, electrolyte optimization, binder selection, and electrode architecture for enhancing their efficiency and performance. Moreover, future research in the field of organic cathode materials should focus on addressing current limitations such as low energy density, cycling stability, poor rate capability, and potential safety concerns, and advancing their performance. This includes enhancing conductivity, optimizing synthesis methods, improving structural stability, addressing capacity fading and cycle life issues, exploring new redox-active organic compounds, and paving the way for the next generation of high-performance energy storage devices. Additionally, the development of scalable and cost-effective manufacturing processes for organic cathode materials is crucial for their commercial viability.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Conductive Polymers

2.1. Polyaniline (PANI)

2.2. Polypyrrole (PPy)

| Materials | Method of preparation | Capacitance retention | Cyclability | Advantage | Disadvantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| polypyrrole-LiFePO4 (PPy-LiFePO4) composites | Polymerization process | Higher reversible capacity and improved cycling | [23] | |||

| PPy-H4 [PVMo 11O40] and PPy-H5 [PV2Mo10O40] | Chemical polymerization method | Exhibits outstanding capacitance of 561.1 F/g | 95% of its capacitance after 4500 cycles | Pseudo-capacitance behavior and exhibits outstanding capacitance. Both PPy-H5 [PV2Mo10O40] and PPy-H4 [PVMo11O40] have cell capacitances of 5.38 and 9.15 mF, respectively, indicating that they are suitable for use in tiny SC cells. |

[26] | |

| A binary composite polypyrrole@MnMoO4 | in-situ oxidative polymerization | attained 462.9Fg-1 at a rate of 5mVs-1 and 374.8Fg-1 with a current density of 0.2Ag-1 in a three-electrode setup | After 1000 cycles, it preserved 80.6% of its initial capacitance |

outstanding electrochemical performance of PPy@MnMoO4 composite | [27] | |

| polyimide matrix-single wall carbon nanotube, SWCNT, composite electrode materials, modified by polypyrrole electrodeposition | produced maximum specific capacitance values of up to 84.88 F/g and 127.13 F/g, respectively | After more than 500 testing cycles, a capacitance retention of more than 80% was attained | The enhanced electrochemical performance of the nanocomposite was favorably correlated with the electrochemical polymerization-induced doping of PPy into the electrode material. The specific capacitance and capacity of the composite electrodes improve dramatically with an increase in process parameters like pyrrole, Py concentration, and the number of dopants |

[28] |

2.3. Polythiophene (PTs)

| Materials | Method of preparation | Capacitance retention | Cyclability | Advantage | Disadvantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| polythiophene (PTh)/multiwall carbon nanotube (MWNT) composites | Mechanical ball milling, solution mixing, and in situ | The thermal conductivity somewhat increases, the electrical conductivity significantly increases, and the Seebeck coefficient marginally varies, changing from 27.7 to 22.7 V/K | [38] | |||

| polythiophene carbon composites | In-situ oxidative polymerization method | High specific capacity (106 mAh g-1 at a current density of 1 A g-1), and | Good stability (maintaining 58% of initial capacity after 10000 cycles), | Excellent rate performance (90 mAh g-1 at a high current density of 3.5 A g-1) | [39] | |

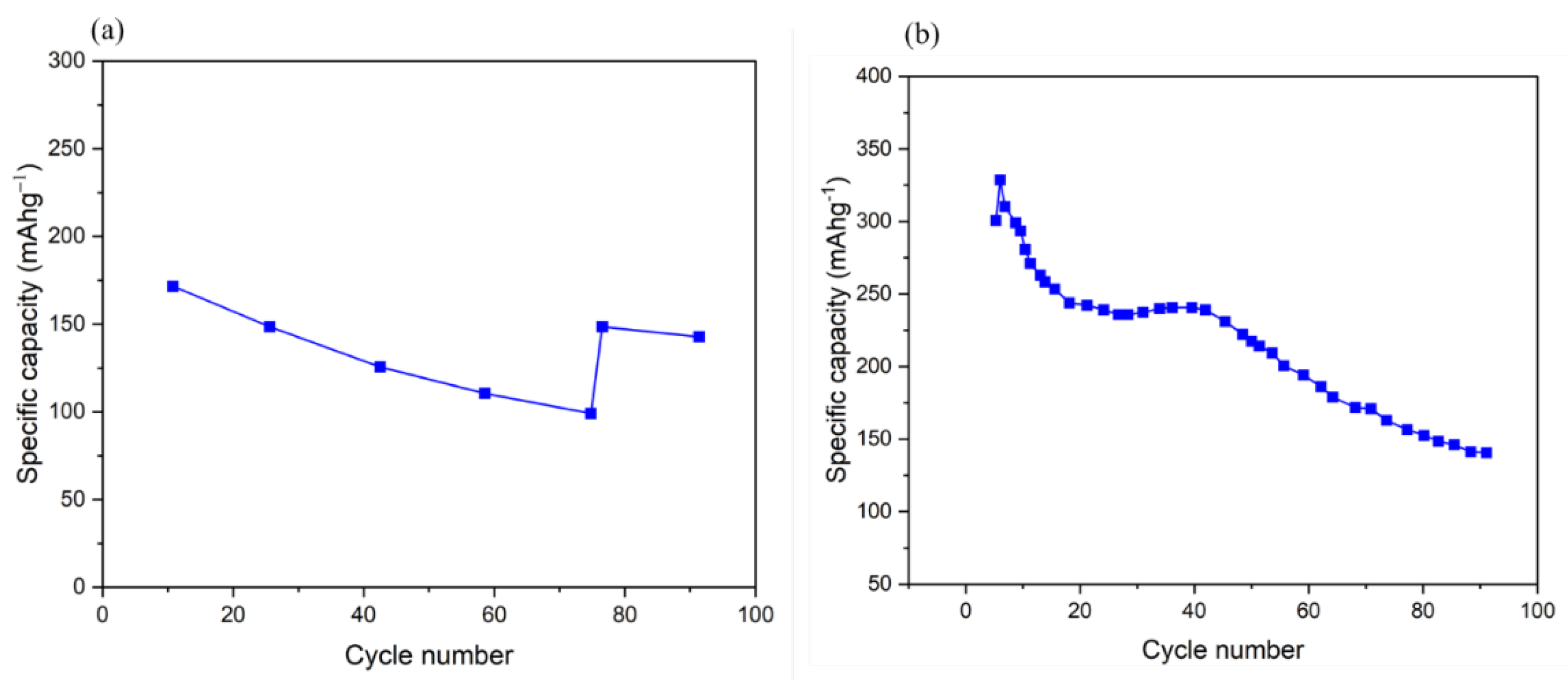

| Novel polythiophene/carbon composites | In-situ chemical polymerization | Remarkable high reversible electrochemical capacity of ~300mAhg-1 (or ~200AhL-1) | Retention of ≥95% after 100 cycles | Could be used as a high-capacity anode material for all-organic storage batteries | [40] | |

| Sulfur/polythiophene composite | low-cost, non-toxic, and scalable technique | An initial discharge capacity of 1074.3 mAh g-1, and | After 90 cycles at 0.1 C, it still had 595.5 mAh g-1 | Successfully prevented the shuttle phenomena and the loss of the sulfur active material during cycling, was associated with the increased composite cycle performance | [43] |

2.4. Organosulfur Compounds

| Materials | Method of preparation | Capacitance retention | Cyclability | Advantage | Disadvantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrous sulfurized TTCA/PAN (STTCA@SPAN) composite | Electrospinning process and inverse vulcanization | 1301 mAh g-1 high-rate capacities of 1028,957, 827, and 660 mAh g-1 at 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 C-rates |

cycle stability over 400 cycles | Exceptional compatibility with carbonate-based electrolytes After a prolonged charge/discharge operation, the cross-linked fibrous morphology retains the cathode's structural stability |

Poor redox kinetics. | [48] |

| Poly (diallyl tetrasulfide) cathode | Radical polymerization | high capacity of 700 mAh g-1 | steady capacity retention of 85% even after 300 cycles | Can store significant quantities of charge per unit mass via a highly reversible redox reaction. The theoretical energy content is much higher than the traditional battery materials and other potential materials such as conducting polymers and intercalation compounds |

[49] | |

| 1,4-bis(diphenylphosphanyl) tetrasulfide (BDPPTS) |

Electrochemical oxidation diphenyl dithiophosphinic acid | High output voltage (2.9 V) | 74.8% capacity retention after 500 cycles | [49] |

3. Organic Radical Compounds

4. Organic Carbonyl Compounds

4.1. Quinone Compound Cathode Materials

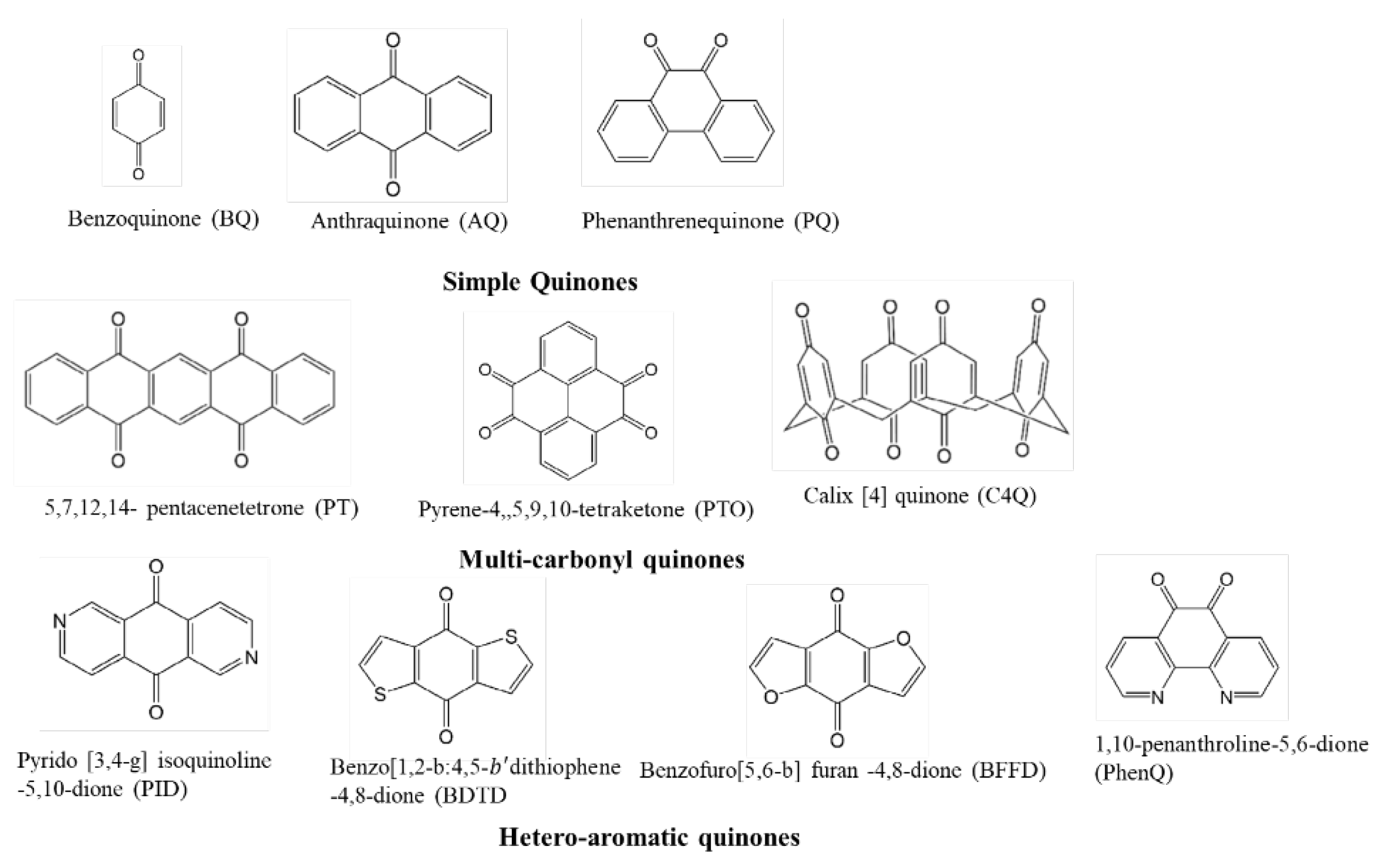

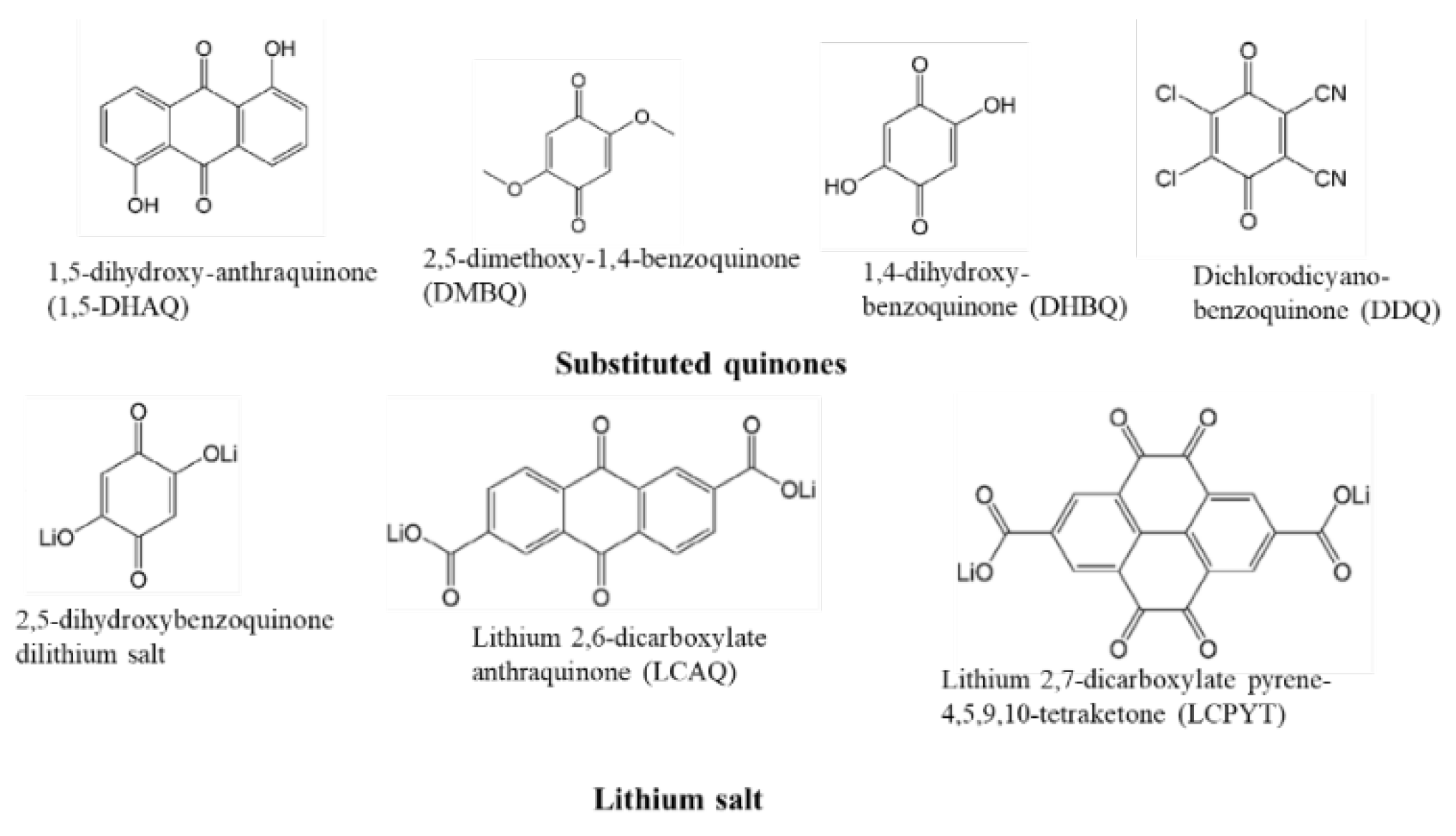

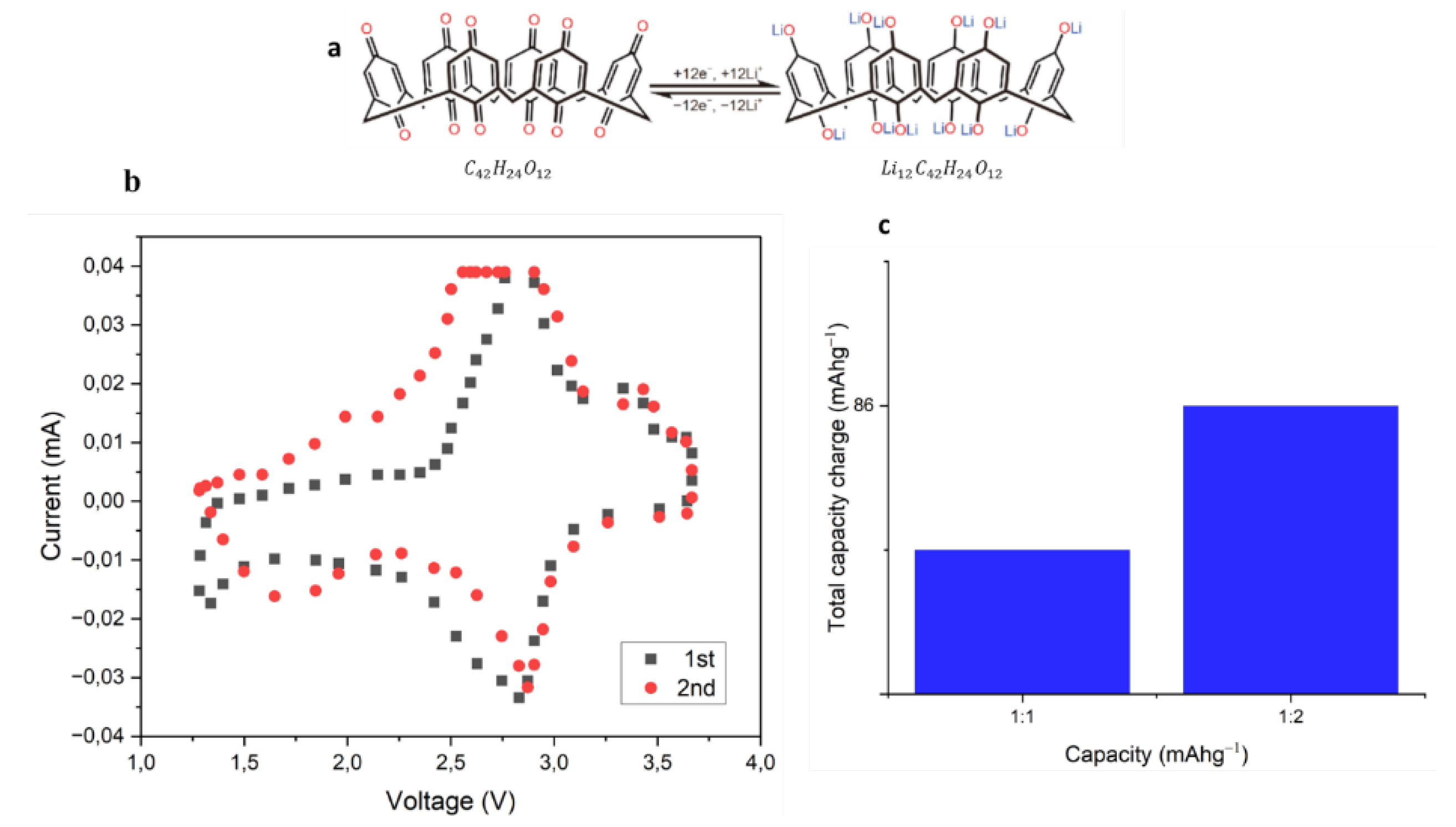

4.1.1. Categories of Quinone Compound Cathode Materials

4.1.2. Electrochemical Performance of Natural Quinones as Organic Electrodes for LIBs

| Materials | Method of preparation | Capacitance retention | Cyclability | Advantage | Disadvantage | Reference |

| lithiated quinone molecule (Li2C6O6) composite | Using myo-inositol | reversible capacity of up to 580 mAhg-1 | Best electrochemical reversibility | [67] | ||

| PADAQ composite | Through the Facile oxidation process | Initial capacity of 101 mAh g-1 at current density of 400 mAg-1 At high current density of 1400 mA g-1, specific capacity 95 mAh g-1, |

After 14 cycles, increases to 143 mAh g-1. after 50 cycles maintains 126 mAh g-1 |

Excellent cyclability and rate performance | high solubility in organic electrolytes and poor intrinsic conductivity | [67] |

| C6Q composite | Through Synthesis, diazonium coupling, reduction, and oxidation. |

Initial capacity of up to 423 mA h g-1 (or around 95% of theoretical capacity) | 195 mA h g-1 after 300 cycles | Excellent rates have less impedance and are more stable throughout the cycling | [69] |

4.2. Organic Acid Anhydride Cathode Materials

4.3. Imide Compound Cathode Materials

4.3.1 Types of Imide Compound Cathode Materials

4.3.2. Electrochemical Efficiency of Imide Compound Cathode Materials

Organic Imine Compounds

| Polymeric system | Monomeric system | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular structure | They are large, repetitive chains of monomer units in the polymeric structures. These chains, which can be straight or branched, come together to form a three-dimensional structure or network. | They are individual molecules that are not chemically bonded together in the monomeric systems. No bigger network structure is formed by these molecules, regardless of how simple or complicated they are. | [4] |

| Cycle life | Extended cycle life such as in PANI nanofibers goes up to 1000 cycles, PPy-H4 [PVMo11O40] and PPy-H5 [PV2Mo10O40] 4500 cycles, polythiophene carbon composites 10000 cycles. polymeric systems generally exhibit superior cycle life compared to monomeric systems | Have a shorter cycle life such as in PADAQ composite 50 cycles, C6Q composite 300 cycles | [13,26,39,68,69] |

| Mechanism | The behavior and characteristics of polymeric systems is determined by interactions and entanglements between polymer chain like in PANI nanofiber, polythiophene (PTh)/multiwall carbon nanotube (MWNT) composites, Poly (diallyl tetrasulfide) (PDTS) cathode | They behave as individual molecules without extensive intermolecular interactions such as in Fibrous sulfurized TTCA/PAN (STTCA@SPAN) composite | . [13,39,49,50] |

| Stability | Good stability against degradation, mechanical strain, and fatigue brought on by cycling. Assuring structural integrity and preventing degradation or loss of active material are made possible by the dense network structure and entanglements between polymer chains. polythiophene carbon composites (maintaining 58% of initial capacity after 10000 cycles), poly (anthraquinonyl sulfide) (PAQS) cathodes stable cycling behavior for 100 cycles with high capacities up to 180 mA h g-1 | Less stability than polymeric systems due to weaker intermolecular interactions and the absence of a robust network structure. This can result in reduced capacitance retention over repeated cycles. Fibrous sulfurized TTCA/PAN (STTCA@SPAN) composite (cycle stability over 400 cycles) | [39,48,98] |

| Capacitance retention | Polymeric systems with strong capacitance retention over numerous cycles include those made of conducting polymers or polymer electrolyte-based systems. PANI/S composite (89.7% capacity retention after 200 cycles at 0.3 C) PPy-H4 [PVMo11O40] and PPy-H5 [PV2Mo10O40] 95% of its capacitance after 4500 cycles, Novel polythiophene/carbon composites retention of ≥95% after 100 cycles |

Depending on the particular molecular structure and characteristics, monomeric systems may display various levels of capacitance retention. 1,4-bis(diphenylphosphanyl) tetrasulfide (BDPPTS) 74.8% capacity retention after 500 cycles, PADAQ composites (58% capacity retention after 100 cycles, C6Q composite Initial capacity of up to 423 mA h g-1 (or around 95% of theoretical capacity) |

[9,26,40,49,67,69] |

| Higher potential | Conducting polymer relatively higher such as in polypyrrole/carbon nanotube composite's −0.5 to 0.5 V | Here it contains a redox-active functional group such as in quinones like in PADAQ's cycle performance at 1.0-3.7 V | [23,67] |

| Doped | Higher doping capability as can be seen in the case of conducting polymers and enhanced conductivity through charge transfer between the polymer and dopant molecules/ions as seen in the case of PANI and polypyrrole | Limited doping capability when compared with polymeric systems such as poly (2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy-4-yl methacrylate) | [28,55,56] |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

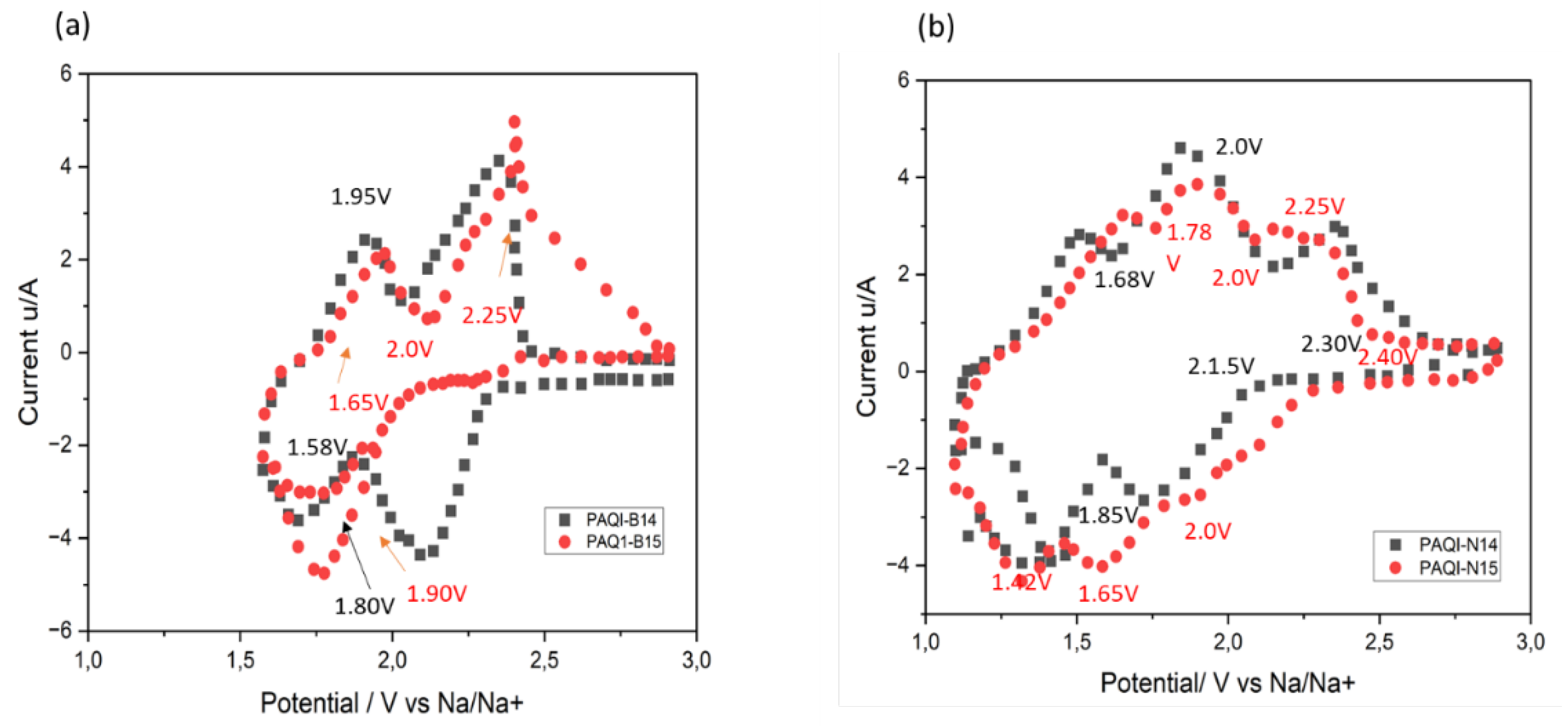

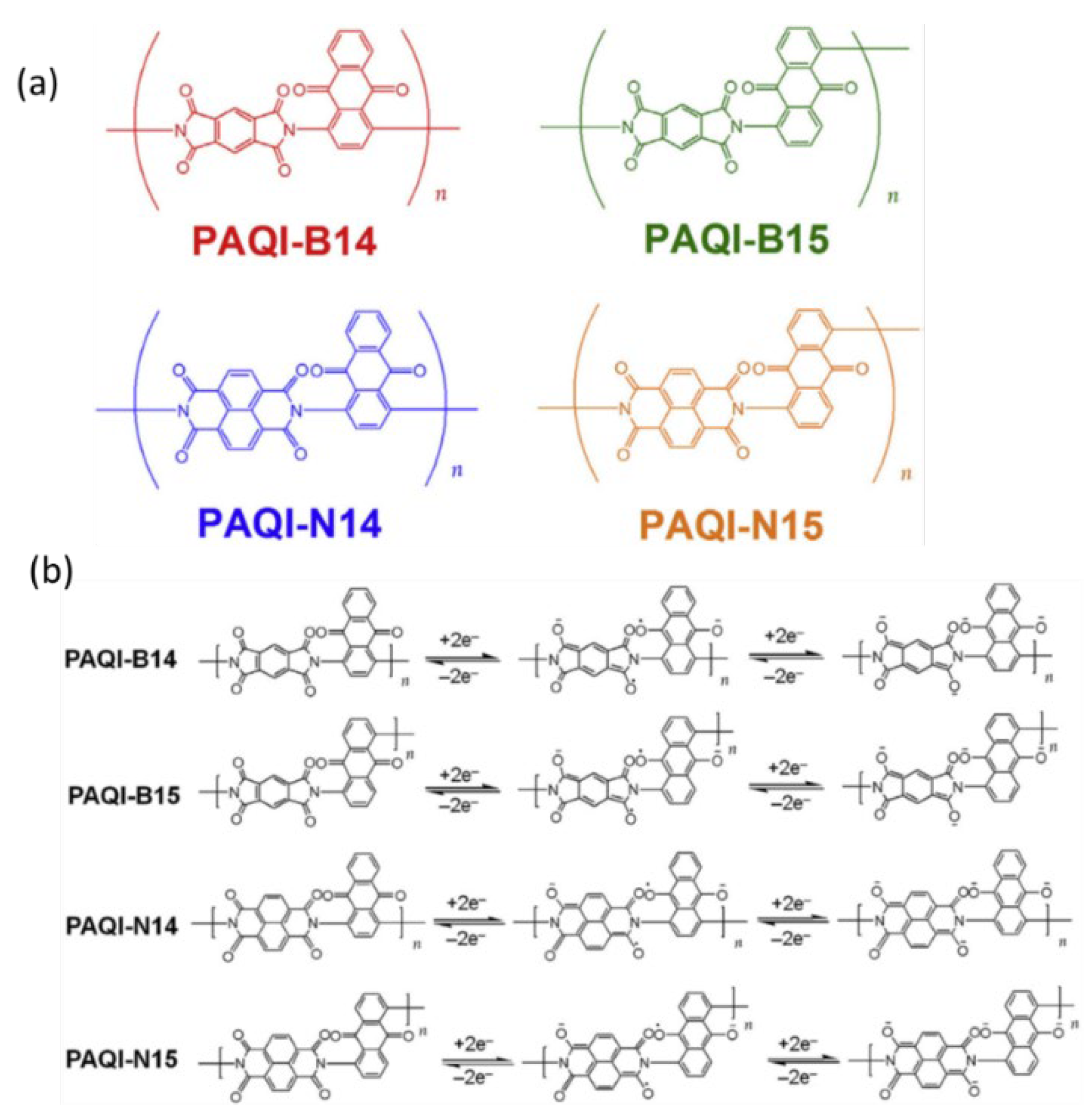

- Xu, F., Wang, H., Wu, M., Nan, J., Li, T. and Cao, S.A., 2018. Electrochemical properties of poly (anthraquinonyl imide) s as high-capacity organic cathode materials for Li-ion batteries. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 214, pp.120-125.

- Sui, D., Xu, L., Zhang, H., Sun, Z., Kan, B., Ma, Y. and Chen, Y., 2020. A 3D cross-linked graphene-based honeycomb carbon composite with excellent confinement effect of organic cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. Carbon, 157, pp.656-662.

- Shi, T., Li, G., Han, Y., Gao, Y., Wang, F., Hu, Z., Cai, T., Chu, J. and Song, Z., 2022. Oxidized indanthrone is a cost-effective and high-performance organic cathode material for rechargeable lithium batteries. Energy Storage Materials, 50, pp.265-273.

- Lyu, H., Sun, X.G. and Dai, S., 2021. Organic Cathode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries: Past, Present, and Future. Advanced Energy and Sustainability Research, 2(1), p.2000044.

- Wang, Y., Zhao, X., Wang, Y., Qiu, W., Song, E., Wang, S. and Liu, J., 2022. Trinitroaromatic Salts as High-Energy-Density Organic Cathode Materials for Li-Ion Batteries. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

- Liu, K., Zhao, H., Ye, D. and Zhang, J., 2021. Recent progress in organic Polymers-Composited sulfur materials as cathodes for Lithium-Sulfur battery. Chemical Engineering Journal, 417, p.129309.

- Nezakati, T., Seifalian, A., Tan, A. and Seifalian, A.M., 2018. Conductive polymers: opportunities and challenges in biomedical applications. Chemical Reviews, 118(14), pp.6766-6843.

- Li, Z. and Gong, L., 2020. Research progress on applications of polyaniline (PANI) for electrochemical energy storage and conversion. Materials, 13(3), p.548.

- Yan, J., Li, B. and Liu, X., 2015. Nano-porous sulfur–polyaniline electrodes for lithium–sulfurbatteries. Nano Energy, 18, pp.245-252.

- Chen, H., Chen, J.S., Zhou, H.H., Jiao, S.Q., Chen, J.H. and Kuang, Y.F., 2004. The application of nano-fibrous polyaniline in an electrochemical capacitor. ACTA PHYSICO-CHIMICA SINICA, 20(6), pp.593-597.

- Zhou, H., Chen, H., Luo, S., Lu, G., Wei, W. and Kuang, Y., 2005. The effect of the polyaniline morphology on the performance of polyaniline supercapacitors. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry, 9, pp.574-580.

- Liu, J., Zhou, M., Fan, L.Z., Li, P. and Qu, X., 2010. Porous polyaniline exhibits highly enhanced electrochemical capacitance performance. Electrochimica Acta, 55(20), pp.5819-5822.

- Wang, H., Lin, J. and Shen, Z.X., 2016. Polyaniline (PANi) based electrode materials for energy storage and conversion. Journal of Science: Advanced materials and devices, 1(3), pp.225-255.

- Chen, W.C., Wen, T.C. and Teng, H., 2003. Polyaniline-deposited porous carbon electrode for supercapacitor. Electrochimica Acta, 48(6), pp.641-649.

- Ferchichi, K., Hbaieb, S., Amdouni, N., Pralong, V. and Chevalier, Y., 2014. Pickering emulsion polymerization of polyaniline/LiCoO 2 nanoparticles used as cathode materials for lithium batteries. Ionics, 20, pp.1301-1314.

- Ferchichi, K., Hbaieb, S., Amdouni, N., Pralong, V. and Chevalier, Y., 2013. Structural and electrochemical characterization of polyaniline/LiCoO 2 nanocomposites prepared via a Pickering emulsion. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry, 17, pp.1435-1447.

- Su, C., Lu, G., Xu, L. and Zhang, C., 2012. Preparation of LiFePO4/Carbon/PANI-CSA composite and its properties as high-capacity cathodes for lithium-ion batteries. Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 159(3), p.A305.

- Taghizadeh, A., Taghizadeh, M., Jouyandeh, M., Yazdi, M.K., Zarrintaj, P., Saeb, M.R., Lima, E.C. and Gupta, V.K., 2020. Conductive polymers in water treatment: a review. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 312, p.113447.

- Wang, H., Lin, J. and Shen, Z.X., 2016. Polyaniline (PANi) based electrode materials for energy storage and conversion. Journal of Science: Advanced materials and devices, 1(3), pp.225-255.

- MA, C., SG, P., PR, G., RN, M., Shashwati, S. and VB, P., 2011. Synthesis and characterization of polypyrrole (PPy) thin films. Soft nanoscience letters, 2011.

- Ramanavičius, A., Ramanavičienė, A. and Malinauskas, A., 2006. Electrochemical sensors based on conducting polymer—polypyrrole. Electrochimica acta, 51(27), pp.6025-6037.

- An, H., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Zheng, L., Wang, X., Yi, L., Bai, L. and Zhang, X., 2010. Polypyrrole/carbon aerogel composite materials for supercapacitor. Journal of Power Sources, 195(19), pp.6964-6969.

- Mi, H., Zhang, X., Xu, Y. and Xiao, F., 2010. Synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical behavior of polypyrrole/carbon nanotube composites using organometallic-functionalized carbon nanotubes. Applied Surface Science, 256(7), pp.2284-2288.

- Wang, G.X., Yang, L., Chen, Y., Wang, J.Z., Bewlay, S. and Liu, H.K., 2005. An investigation of polypyrrole-LiFePO4 composite cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochimica Acta, 50(24), pp.4649-4654.

- Wang, J., Chen, J., Konstantinov, K., Zhao, L., Ng, S.H., Wang, G.X., Guo, Z.P. and Liu, H.K., 2006. Sulfur-polypyrrole composite positive electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. Electrochimica Acta, 51(22), pp.4634-4638.

- Vannathan, A.A., Maity, S., Kella, T., Shee, D., Das, P.P. and Mal, S.S., 2020. In situ, vanadophosphomolybdate was impregnated into conducting polypyrrole for the supercapacitor. Electrochimica Acta, 364, p.137286.

- Wang, H., Song, Y., Zhou, J., Xu, X., Hong, W., Yan, J., Xue, R., Zhao, H., Liu, Y. and Gao, J., 2016. High-performance supercapacitor materials based on polypyrrole composites embedded with core-sheath polypyrrole@ MnMoO4 nanorods. Electrochimica Acta, 212, pp.775-783.

- Gooneratne, R. and Iroh, J.O., 2022. Polypyrrole Modified Carbon Nanotube/Polyimide Electrode Materials for Supercapacitors and Lithium-ion Batteries. Energies, 15(24), p.9509.

- Liu, L., Tian, F., Wang, X., Yang, Z., Zhou, M. and Wang, X., 2012. Porous polythiophene as a cathode material for lithium batteries with high capacity and good cycling stability. Reactive and Functional Polymers, 72(1), pp.45-49.

- Senthilkumar, B., Thenamirtham, P. and Selvan, R.K., 2011. Structural and electrochemical properties of polythiophene. Applied Surface Science, 257(21), pp.9063-9067.

- Jose, M.A., Varghese, S. and Antony, M.J., 2016. In situ chemical oxidative polymerization for ordered conducting polythiophene nanostructures in the presence of dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate.

- Gök, A., Omastová, M. and Yavuz, A.G., 2007. Synthesis and characterization of polythiophenes prepared in the presence of surfactants. Synthetic metals, 157(1), pp.23-29.

- Omastova, M., Trchova, M., Kovářová, J. and Stejskal, J., 2003. Synthesis and structural study of polypyrroles prepared in the presence of surfactants. Synthetic metals, 138(3), pp.447-455.

- Geetha, S. and Trivedi, D.C., 2005. A new route to synthesize high-degree polythiophene in a room temperature melt medium. Synthetic metals, 155(1), pp.232-239.

- Zhang, X., Chen, K., Sun, Z., Hu, G., Xiao, R., Cheng, H.M. and Li, F., 2020. Structure-related electrochemical performance of organosulfur compounds for lithium–sulfur batteries. Energy & Environmental Science, 13(4), pp.1076-1095.

- Liang, Y., Tao, Z. and Chen, J., 2012. Organic electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. Advanced Energy Materials, 2(7), pp.742-769.

- Zhang, X., Chen, K., Sun, Z., Hu, G., Xiao, R., Cheng, H.M. and Li, F., 2020. Structure-related electrochemical performance of organosulfur compounds for lithium–sulfur batteries. Energy & Environmental Science, 13(4), pp.1076-1095.

- Wang, L., Jia, X., Wang, D., Zhu, G. and Li, J., 2013. Preparation and thermoelectric properties of polythiophene/multiwalled carbon nanotube composites. Synthetic metals, 181, pp.79-85.

- Kong, D., Fan, H., Wang, X., Hu, H., Li, B., Wang, D., Tian, S., Gao, X. and Xing, W., 2021, February. Polythiophene/Carbon Microsphere Composite as a High-Performance Cathode Material for Aluminium-ion Batteries. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 651, No. 2, p. 022032). IOP Publishing.

- Zhu, L.M., Shi, W., Zhao, R.R., Cao, Y.L., Ai, X.P., Lei, A.W. and Yang, H.X., 2013. n-Dopable polythiophenes as high-capacity anode materials for all-organic Li-ion batteries. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, 688, pp.118-122.

- Thakur, A.K., Majumder, M., Choudhary, R.B. and Pimpalkar, S.N., 2016, September. Supercapacitor based on electropolymerized polythiophene and multiwalled carbon nanotubes composites. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 149, No. 1, p. 012166). IOP Publishing.

- Li, Z., Guo, A. and Liu, D., 2022. Water-Soluble Conductive Composite Binder for High-Performance Silicon Anode in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries, 8(6), p.54.

- Li, Z., Xu, R., Deng, S., Su, X., Wu, W., Liu, S. and Wu, M., 2018. MnS decorated N/S codoped 3D graphene which is used as cathode of the lithium-sulfur battery. Applied Surface Science, 433, pp.10-15.

- Zhang, W., Ma, F., Guo, S., Chen, X., Zeng, Z., Wu, Q., Li, S., Cheng, S. and Xie, J., 2022. A model cathode for mechanistic study of organosulfide electrochemistry in Li-organosulfide batteries. Journal of Energy Chemistry, 66, pp.440-447.

- Weret, M.A., Kuo, C.F.J., Su, W.N., Zeleke, T.S., Huang, C.J., Sahalie, N.A., Zegeye, T.A., Wondimkun, Z.T., Fenta, F.W., Jote, B.A. and Tsai, M.C., 2022. Fibrous organosulfur cathode materials with high bonded sulfur for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries. Journal of Power Sources, 541, p.231693.

- Zhang, Q., Ma, Q., Wang, R., Liu, Z., Zhai, Y., Pang, Y., Tang, Y., Wang, Q., Wu, K., Wu, H. and Zhang, Y., 2023. Recent progress in advanced organosulfur cathode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. Materials Today.

- NuLi, Y., Guo, Z., Liu, H. and Yang, J., 2007. A new class of cathode materials for rechargeable magnesium batteries: organosulfur compounds based on sulfur–sulfur bonds. Electrochemistry Communications, 9(8), pp.1913-1917.

- Nishide, H., Iwasa, S., Pu, Y.J., Suga, T., Nakahara, K. and Satoh, M., 2004. Organic radical battery: nitroxide polymers as a cathode-active material. Electrochimica acta, 50(2-3), pp.827-831.

- Khelifa, F., Ershov, S., Habibi, Y., Snyders, R. and Dubois, P., 2016. Free-radical-induced grafting from plasma polymer surfaces. Chemical Reviews, 116(6), pp.3975-4005.

- Ashfaq, A., Clochard, M.C., Coqueret, X., Dispenza, C., Driscoll, M.S., Ulański, P. and Al-Sheikhly, M., 2020. Polymerization reactions and modifications of polymers by ionizing radiation. Polymers, 12(12), p.2877.

- Xie, Y., Zhang, K., Yamauchi, Y., Oyaizu, K. and Jia, Z., 2021. Nitroxide radical polymers for emerging plastic energy storage and organic electronics: fundamentals, materials, and applications. Materials Horizons, 8(3), pp.803-829.

- Kim, J.K., Cheruvally, G., Ahn, J.H., Seo, Y.G., Choi, D.S., Lee, S.H. and Song, C.E., 2008. Organic radical battery with PTMA cathode: Effect of PTMA content on electrochemical properties. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 14(3), pp.371-376.

- Zhao, L., Wang, W., Wang, A., Yuan, K., Chen, S. and Yang, Y., 2013. A novel polyquinone cathode material for rechargeable lithium batteries. Journal of power sources, 233, pp.23-27.

- Liang, Y., Tao, Z. and Chen, J., 2012. Organic electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. Advanced Energy Materials, 2(7), pp.742-769.

- Zhu, X. and Jing, Y., 2022. Natural quinone molecules as effective cathode materials for nonaqueous lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources, 531, p.231291.

- Kotal, M., Jakhar, S., Roy, S. and Sharma, H.K., 2022. Cathode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries: Recent progress and future prospects. Journal of Energy Storage, 47, p.103534.

- Bhosale, M.E., Chae, S., Kim, J.M. and Choi, J.Y., 2018. Organic small molecules and polymers as an electrode material for rechargeable lithium ion batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 6(41), pp.19885-19911.

- Li, S., Liu, Y., Dai, L., Li, S., Wang, B., Xie, J. and Li, P., 2022. A stable covalent organic framework cathode enables ultra-long cycle life for alkali and multivalent metal rechargeable batteries. Energy Storage Materials, 48, pp.439-446.

- Shadike, Z., Tan, S., Wang, Q.C., Lin, R., Hu, E., Qu, D. and Yang, X.Q., 2021. Review on organosulfur materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. Materials Horizons, 8(2), pp.471-500.

- Nakahara, K., Oyaizu, K. and Nishide, H., 2011. Organic radical battery approaching practical use. Chemistry letters, 40(3), pp.222-227.

- Wu, Y., Zeng, R., Nan, J., Shu, D., Qiu, Y. and Chou, S.L., 2017. Quinone electrode materials for rechargeable lithium/sodium ion batteries. Advanced Energy Materials, 7(24), p.1700278.

- McSkimming, A. and Colbran, S.B., 2013. The coordination chemistry of organo-hydride donors: new prospects for efficient multi-electron reduction. Chemical Society Reviews, 42(12), pp.5439-5488.

- Power, P.P., 2003. Persistent and stable radicals of the heavier main group elements and related species. Chemical Reviews, 103(3), pp.789-810.

- Zhao, L. Wang, W., Wang, A., Yuan, K., Chen, S. and Yang, Y., 2013. A novel polyquinone cathode material for rechargeable lithium batteries. Journal of power sources, 233, pp.23-27.

- Huang, W. Zhang, X., Zheng, S., Zhou, W., Xie, J., Yang, Z. and Zhang, Q., 2020. Calix [6] quinone as high-performance cathode for lithium-ion battery. Sci. China Mater, 63(3), pp.339-346.

- Huang, W. Liu, S., Li, C., Lin, Y., Hu, P., Sun, Z. and Zhang, Q., 2022. Calix [8] quinone: A new promising macrocyclic molecule as an efficient organic cathode in lithium ion batteries with a highly-concentrated electrolyte. EcoMat, 4(5), p.e12214.

- Amin, K. Mao, L. and Wei, Z., 2019. Recent progress in polymeric carbonyl-based electrode materials for lithium and sodium ion batteries. Macromolecular rapid communications, 40(1), p.1800565.

- Tran, N.A. Do Van Thanh, N. and Le, M.L.P., 2021. Organic positive materials for magnesium batteries: A review. Chemistry–A European Journal, 27(36), pp.9198-9217.

- Banerjee, A. Khossossi, N., Luo, W. and Ahuja, R., 2022. Promise and reality of organic electrodes from materials design and charge storage perspective. Journal of Materials Chemistry A.

- Xu, J. Dou, S., Cui, X., Liu, W., Zhang, Z., Deng, Y., Hu, W. and Chen, Y., 2021. Potassium-based electrochemical energy storage devices: Development status and future prospect. Energy Storage Materials, 34, pp.85-106.

- Kotal, M. Jakhar, S., Roy, S. and Sharma, H.K., 2022. Cathode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries: Recent progress and future prospects. Journal of Energy Storage, 47, p.103534.

- Zhu, L. Ding, G., Xie, L., Cao, X., Liu, J., Lei, X. and Ma, J., 2019. Conjugated carbonyl compounds as high-performance cathode materials for rechargeable batteries. Chemistry of Materials, 31(21), pp.8582-8612.

- Wang, J. Wang, X., Li, H., Yang, X. and Zhang, Y., 2016. Intrinsic factors attenuate the performance of anhydride organic cathode materials of lithium battery. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, 773, pp.22-26.

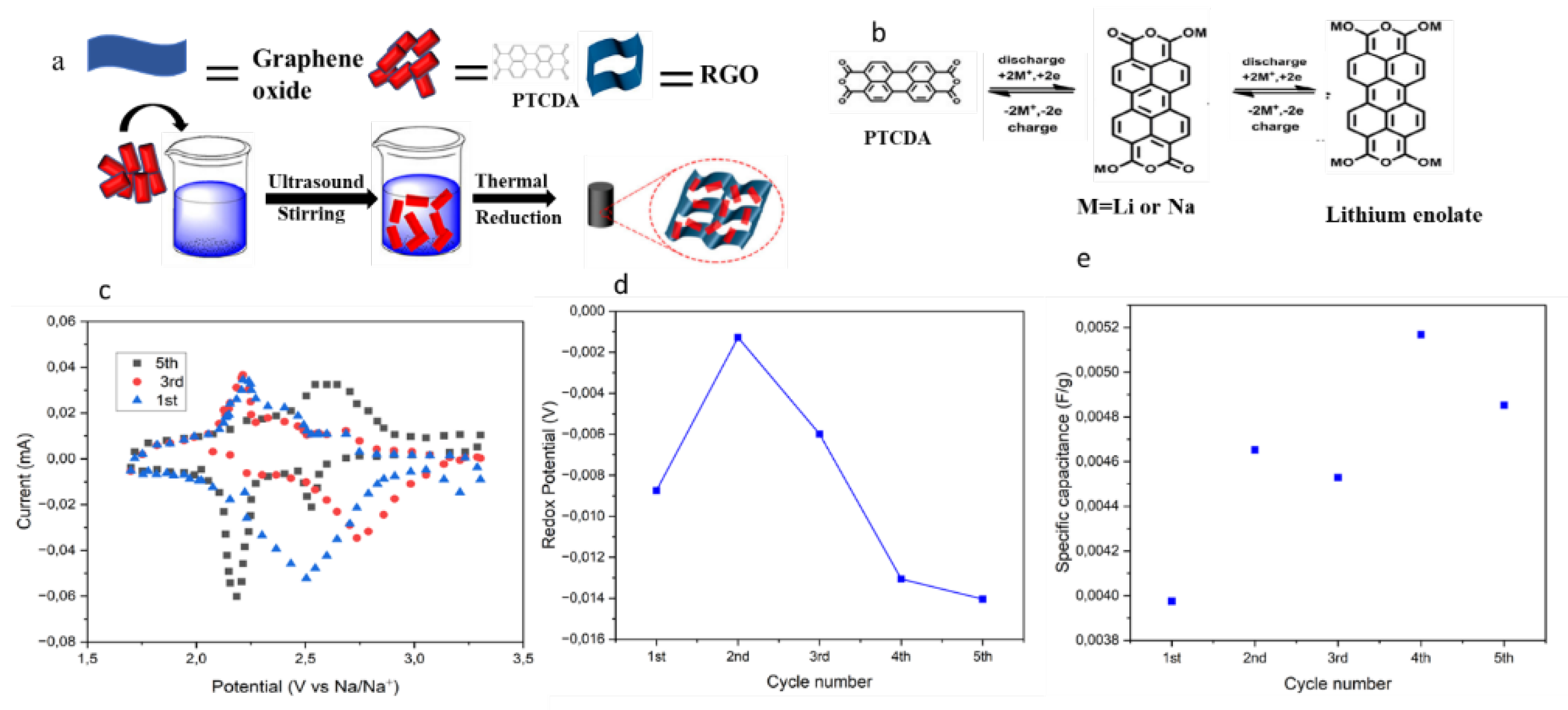

- Yuan, C. Wu, Q., Li, Q., Duan, Q., Li, Y. and Wang, H.G., 2018. Nanoengineered ultralight organic cathode based on aromatic carbonyl compound/graphene aerogel for green lithium and sodium ion batteries. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 6(7), pp.8392-8399.

- Luo, W. Allen, M., Raju, V. and Ji, X., 2014. An Organic pigment as a high-performance cathode for sodium-ion batteries. Advanced Energy Materials, 4(15), p.1400554.

- Poizot, P. Gaubicher, J., Renault, S., Dubois, L., Liang, Y. and Yao, Y., 2020. Opportunities and challenges for organic electrodes in electrochemical energy storage. Chemical reviews, 120(14), pp.6490-6557.

- Zhu, Z. Jiang, T., Ali, M., Meng, Y., Jin, Y., Cui, Y. and Chen, W., 2022. Rechargeable batteries for grid-scale energy storage. Chemical Reviews, 122(22), pp.16610-16751.

- Sun, T. Xie, J., Guo, W., Li, D.S. and Zhang, Q., 2020. Covalent–organic frameworks: advanced organic electrode materials for rechargeable batteries. Advanced Energy Materials, 10(19), p.1904199.

- Peng, H. Yu, Q., Wang, S., Kim, J., Rowan, A.E., Nanjundan, A.K., Yamauchi, Y. and Yu, J., 2019. Molecular design strategies for electrochemical behavior of aromatic carbonyl compounds in organic and aqueous electrolytes. Advanced Science, 6(17), p.1900431.

- Van Der Jagt, R. Vasileiadis, A., Veldhuizen, H., Shao, P., Feng, X., Ganapathy, S., Habisreutinger, N.C., van der Veen, M.A., Wang, C., Wagemaker, M. and van der Zwaag, S., 2021. Synthesis and structure–property relationships of polyimide covalent organic frameworks for carbon dioxide capture and (aqueous) sodium-ion batteries. Chemistry of Materials, 33(3), pp.818-833.

- Duan, H. Li, K., Xie, M., Chen, J.M., Zhou, H.G., Wu, X., Ning, G.H., Cooper, A.I. and Li, D., 2021. Scalable synthesis of ultrathin polyimide covalent organic framework nanosheets for high-performance lithium–sulfur batteries. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 143(46), pp.19446-19453.

- Zhao, Q. Zhu, Z. and Chen, J., 2017. Molecular engineering with organic carbonyl electrode materials for advanced stationary and redox flow rechargeable batteries. Advanced Materials, 29(48), p.1607007.

- Oubaha, H. Gohy, J.F. and Melinte, S., 2019. Carbonyl-based π-conjugated materials: from synthesis to applications in lithium-ion batteries. ChemPlusChem, 84(9), pp.1179-1214.

- Li, C. and Wonneberger, H., 2012. Perylene imides for organic photovoltaics: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Advanced Materials, 24(5), pp.613-636.

- Renault, S. Geng, J., Dolhem, F. and Poizot, P., 2011. Evaluation of polyketones with N-cyclic structure as electrode material for electrochemical energy storage: case of pyromellitic diimide dilithium salt. Chemical Communications, 47(8), pp.2414-2416.

- Xu, K. 2014. Electrolytes and interphases in Li-ion batteries and beyond. Chemical reviews, 114(23), pp.11503-11618.

- Kim, D.J. Je, S.H., Sampath, S., Choi, J.W. and Coskun, A., 2012. Effect of N-substitution in naphthalenediimides on the electrochemical performance of organic rechargeable batteries. Rsc Advances, 2(21), pp.7968-7970.

- Zhuang, Y. Seong, J.G. and Lee, Y.M., 2019. Polyimides containing aliphatic/alicyclic segments in the main chains. Progress in Polymer Science, 92, pp.35-88.

- Song, Z. Zhan, H. and Zhou, Y., 2010. Polyimides: promising energy-storage materials. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 49(45), pp.8444-8448.

- Kapaev, R.R. Scherbakov, A.G., Shestakov, A.F., Stevenson, K.J. and Troshin, P.A., 2021. m-Phenylenediamine as a Building Block for Polyimide Battery Cathode Materials. ACS Applied Energy Materials, 4(5), pp.4465-4472.

- Wu, F. Maier, J. and Yu, Y., 2020. Guidelines and trends for next-generation rechargeable lithium and lithium-ion batteries. Chemical Society Reviews, 49(5), pp.1569-1614.

- Wang, M. Zhang, H., Cui, J., Yao, S., Shen, X., Park, T.J. and Kim, J.K., 2021. Recent advances in emerging nonaqueous K-ion batteries: from mechanistic insights to practical applications. Energy Storage Materials, 39, pp.305-346.

- Li, K. Wang, Y., Gao, B., Lv, X., Si, Z. and Wang, H.G., 2021. Conjugated microporous polyarylimides immobilization on carbon nanotubes with improved utilization of carbonyls as cathode materials for lithium/sodium-ion batteries. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 601, pp.446-453.

- Xu, F. Wang, H., Lin, J., Luo, X., Cao, S.A. and Yang, H., 2016. Poly (anthraquinonyl imide) as a high capacity organic cathode material for Na-ion batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 4(29), pp.11491-11497.

- Yang, H. Lee, J., Cheong, J.Y., Wang, Y., Duan, G., Hou, H., Jiang, S. and Kim, I.D., 2021. Molecular engineering of carbonyl organic electrodes for rechargeable metal-ion batteries: fundamentals, recent advances, and challenges. Energy & Environmental Science, 14(8), pp.4228-4267.

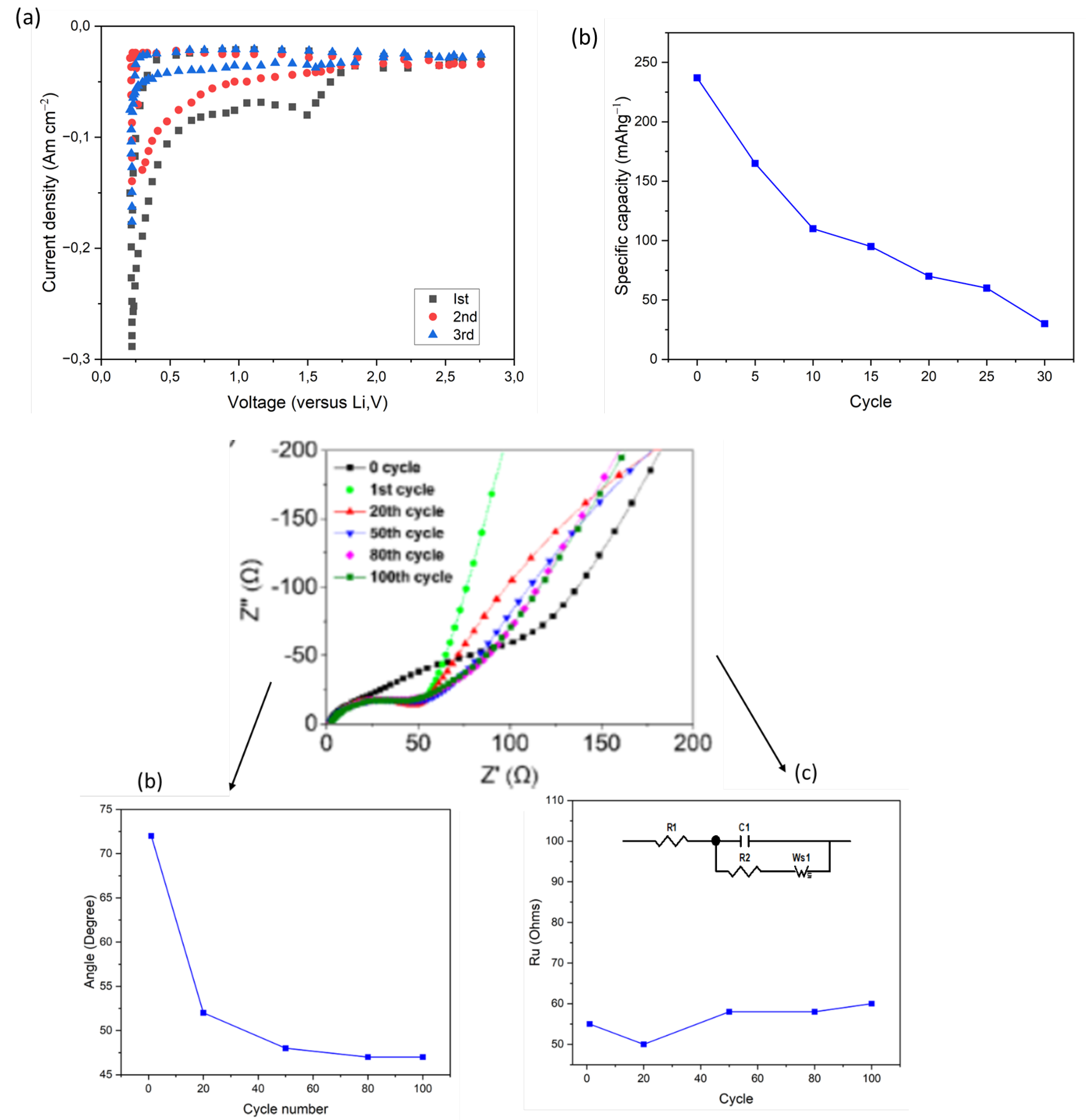

- Song, Z. Xu, T., Gordin, M.L., Jiang, Y.B., Bae, I.T., Xiao, Q., Zhan, H., Liu, J. and Wang, D., 2012. Polymer–graphene nanocomposites as ultrafast-charge and-discharge cathodes for rechargeable lithium batteries. Nano letters, 12(5), pp.2205-2211.

- Wu, H. Wang, K., Meng, Y., Lu, K. and Wei, Z., 2013. An organic cathode material based on a polyimide/CNT nanocomposite for lithium ion batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 1(21), pp.6366-6372.

- Lyu, H. Li, P., Liu, J., Mahurin, S., Chen, J., Hensley, D.K., Veith, G.M., Guo, Z., Dai, S. and Sun, X.G., 2018. Aromatic polyimide/graphene composite organic cathodes for fast and sustainable lithium-ion batteries. ChemSusChem, 11(4), pp.763-772.

- Wan, B. Dong, X., Yang, X., Wang, J., Zheng, M.S., Dang, Z.M., Chen, G. and Zha, J.W., 2023. Rising of Dynamic Polyimide Materials: A Versatile Dielectric for Electrical and Electronic Applications. Advanced Materials, p.2301185.

- You, C. Wu, X., Yuan, X., Chen, Y., Liu, L., Zhu, Y., Fu, L., Wu, Y., Guo, Y.G. and van Ree, T., 2020. Advances in rechargeable Mg batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 8(48), pp.25601-25625.

- Wang, Y. Liu, Z., Wang, C., Hu, Y., Lin, H., Kong, W., Ma, J. and Jin, Z., 2020. π-Conjugated polyimide-based organic cathodes with extremely long cycling life for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Energy Storage Materials, 26, pp.494-502.

- Luo, C. Ji, X., Hou, S., Eidson, N., Fan, X., Liang, Y., Deng, T., Jiang, J. and Wang, C., 2018. Azo compounds derived from electrochemical reduction of nitro compounds for high performance Li-ion batteries. Advanced Materials, 30(23), p.1706498.

- Ciaccia, M. and Di Stefano, S., 2015. Mechanisms of imine exchange reactions in organic solvents. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 13(3), pp.646-654.

- Long, Z. Shi, C., Wu, C., Yuan, L., Qiao, H. and Wang, K., 2022. Heterostructure Fe 2 O 3 nanorods@ imine-based covalent organic framework for long cycling and high-rate lithium storage. Nanoscale, 14(5), pp.1906-1920.

- Okafor, P.A. and Iroh, J.O., 2015. Fabrication of porous graphene/polyimide composites using leachable poly-acrylic resin for enhanced electrochemical and energy storage capabilities. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 3(33), pp.17230-17240.

- Tie, Z. and Niu, Z., 2020. Design strategies for high-performance aqueous Zn/organic batteries. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 59(48), pp.21293-21303.

- Lian, L. Li, K., Ren, L., Han, D., Lv, X. and Wang, H.G., 2023. Imine-linked triazine-based conjugated microporous polymers/carbon nanotube composites as organic anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 657, p.130496.

- Pang, Y. Li, H., Zhang, S., Ma, Q., Xiong, P., Wang, R., Zhai, Y., Li, H., Kang, H., Liu, Y. and Zhang, L., 2022. Conjugated porous polyimide poly (2, 6-diaminoanthraquinone) benzamide with good stability and high-performance as a cathode for sodium ion batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 10(3), pp.1514-1521.

- Kuan, H.C. Luu, N.T., Ivanov, A.S., Chen, T.H., Popovs, I., Lee, J.C. and Kaveevivitchai, W., 2022. A nitrogen-and carbonyl-rich conjugated small-molecule organic cathode for high-performance sodium-ion batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 10(30), pp.16249-16257.

- Waller, P.J. AlFaraj, Y.S., Diercks, C.S., Jarenwattananon, N.N. and Yaghi, O.M., 2018. Conversion of imine to oxazole and thiazole linkages in covalent organic frameworks. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 140(29), pp.9099-9103.

- Chen, R. Zhao, J., Yu, Z., Cong, M., Wang, Y., Wang, M., Li, G., Li, Z. and Zhao, Y., 2022. Post-synthetic Fully π-Conjugated Three-Dimensional Covalent Organic Frameworks for High-Performance Lithium Storage. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

- Yusran, Y. Fang, Q. and Valtchev, V., 2020. Electroactive covalent organic frameworks: design, synthesis, and applications. Advanced Materials, 32(44), p.2002038.

- Kotal, M. Jakhar, S., Roy, S. and Sharma, H.K., 2022. Cathode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries: Recent progress and future prospects. Journal of Energy Storage, 47, p.103534.

| Materials | Method of preparation | Capacitance retention | Cyclability | Advantage | Disadvantage | Reference |

| Graphene nanosheets (GNSs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and PANI | Easy chemical in-situ process | 1035 F g-1, 1 mV s-1 | 6% loss after 1000 cycles | exceptionally high specific capacitance | [8] | |

| PANI/S composite | In situ chlorine substitution and vulcanization reactions | Reversible capacity 750 mAh/g | 89.7% capacity retention after 200 cycles at 0.3 C | high rate performance | Low sulfur loading | [9] |

| PANI nanofibers | Interfacial polymerization | 554 Fg-1 -57 Fg-1 | 31% after 1000 cycles | Pure PANI's instability and minimal capacitance contribution make it potentially unsuitable for use as the supercapacitor electrode | [13] | |

| PANI porous carbon electrodes | Electrochemical polymerization | 180 Fg-1 dropped from 180 to 163 Fg-1 |

After 1000 cycles | low conductivity, cycling instability, and structural instability | [15] | |

| PANI/LiCoO2 nanocomposites | Pickering emulsion method | Specific capacity 136 mAh/g | Improved specific capacities | [16] | ||

| A PANI-CSA (camphorsulfonic acid)/C-LFP | Coating C-LFP with PANI-CAS in m-cresol solution. | 10% attained specific capacity up to 165.3mAh/g | The composite cathodes gave improved specific discharge, specific capacity, and rate capabilities | [18] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).