Submitted:

07 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

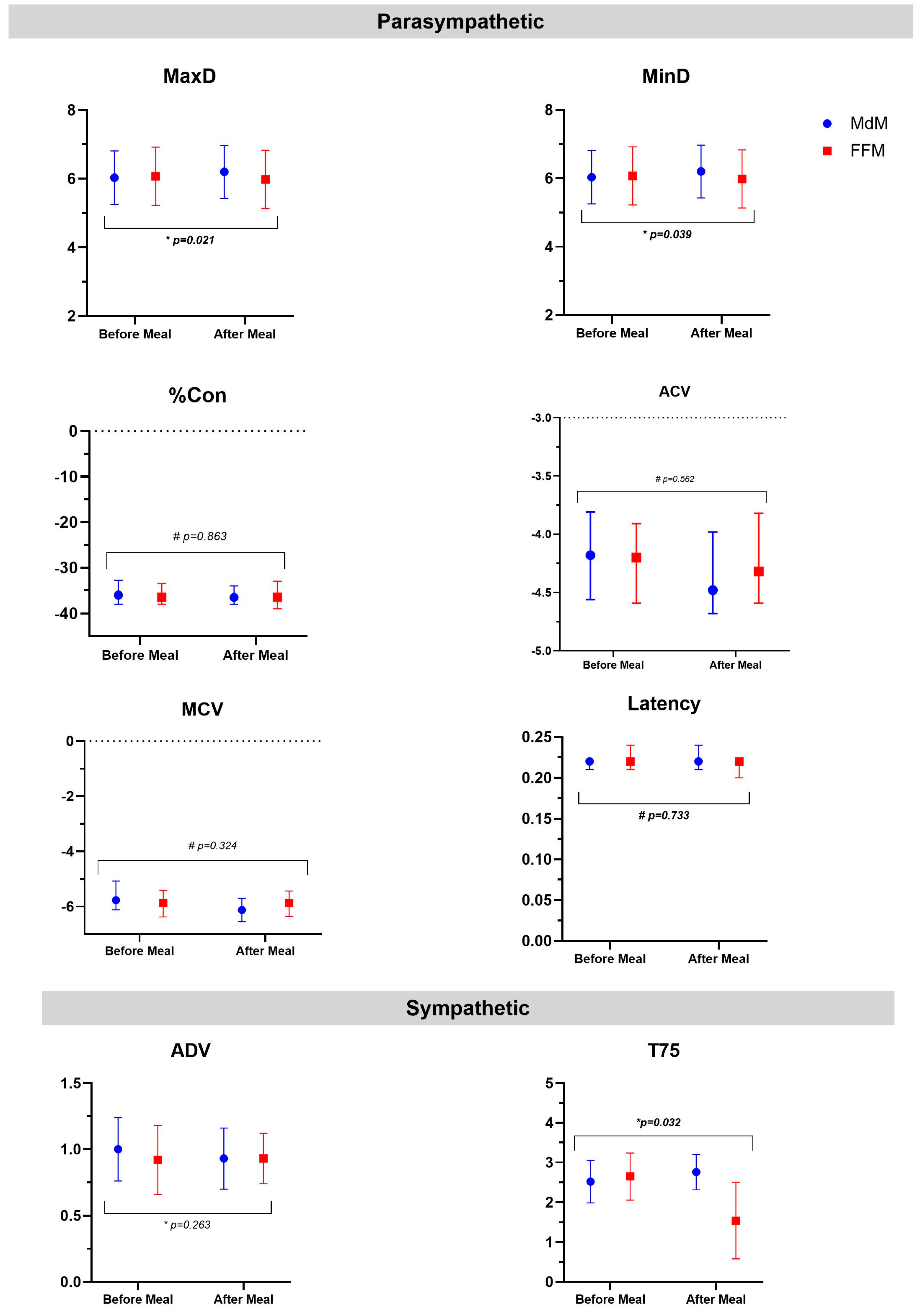

This study aimed to assess the acute effects of two isoenergetic but micronutrient-diverse meals—a Mediterranean-like meal (MdM) and a fast food-like meal (FFM)—on the autonomic nervous system (ANS), lung function, and airway inflammation response. Forty-six participants were enrolled in a randomized cross-over clinical trial, consuming two isoenergetic meals: FFM (burger, fries, and sugar-sweetened drink) and MdM (vegetable soup, whole wheat pasta, salad, olive oil, sardines, fruit, and water). Pupillometry assessed parasympathetic (MaxD, MinD, Con, ACV, MCV) and sympathetic (ADV, T75) nervous system outcomes. Lung function and airway inflammation were measured before and after each meal through spirometry and fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), respectively. Mixed-effects model analysis showed that MdM was associated with a hegemony of parasympathetic response, with a significant increase of MaxD associated with a faster constriction velocity (ACV and MCV); on the other side, the FFM associated with changes in the sympathetic response, showing a quicker redilation velocity (decreased of T75). After adjusting for confounders, mixed-effects models revealed that the FFM significantly decreased T75. Regarding lung function, a meal negatively impacted FVC (ae= -0.079, p<0.001) and FEV1 (ae= -0.04, p= 0.017); however, FeNO increased, although after adjusting, no difference between meals was seen. In conclusion, our study showed that FFM counteracted the parasympathetic activity of a meal, while a meal, irrespective of the type, decreased lung function and increased airway inflammation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Intervention Protocol

2.2.1. Fast Food and Mediterranean Meal

2.3. Outcomes Assessment

2.3.1. Airway Inflammation

2.3.2. Lung Function

2.3.3. Autonomic nervous system

2.4. Other Procedures

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodrigues, M. , et al., Diet quality, asthma and airway inflammation in school-aged children. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol, 2023.

- Wood, L.G. , Diet and lung disease-Are fruits and vegetables the ideal whole-food intervention? Respirology, 2021, 26, 527–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, R. , et al., Associations of a Plant-centered Diet and Lung Function Decline across Early to Mid-Adulthood: The CARDIA Lung Study. Res Sq, 2023.

- Struven, A. , et al., Obesity, Nutrition and Heart Rate Variability. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(8).

- Barros, R. , et al., Dietary patterns and asthma prevalence, incidence and control. Clin Exp Allergy, 2015, 45, 1673–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazouz, H. , et al., Mediterranean diet and lung function, sensitization, and asthma at school age: The PARIS cohort. Pediatr Allergy Immunol, 2021, 32, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, V.A., S. S. Chavan, and K.J. Tracey, Bioelectronic Medicine: From Preclinical Studies on the Inflammatory Reflex to New Approaches in Disease Diagnosis and Treatment. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2020. 10(3).

- Fried, S. , et al., Interactions between the microbiota and enteric nervous system during gut-brain disorders. Neuropharmacology, 2021, 197, 108721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agustí, A. , et al., Interplay Between the Gut-Brain Axis, Obesity and Cognitive Function. Front Neurosci, 2018, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnagarin, R. , et al., Autonomic Regulation of Glucose Homeostasis: a Specific Role for Sympathetic Nervous System Activation. Curr Diab Rep, 2018, 18, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J. , et al., Effects of weight changes in the autonomic nervous system: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr, 2019, 38, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, K. , et al., Gender-Based Vegetarian and Nonvegetarian Dietary Impact on Cardiac Autonomic Function of Heart Rate Variability. J Am Coll Nutr, 2021, 40, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciência, I. , et al., School environment associates with lung function and autonomic nervous system activity in children: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep, 2019, 9, 15156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro Mendes, F. , et al., Increasing Vegetable Diversity Consumption Impacts the Sympathetic Nervous System Activity in School-Aged Children. Nutrients, 2021. 13(5).

- Maunder, E., D. K. Dulson, and D.M. Shaw, Autonomic and Perceptual Responses to Induction of a Ketogenic Diet in Free-Living Endurance Athletes: A Randomized, Crossover Trial. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 2021, 16, 1603–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laugero, K.D. and N.L. Keim, A Diet Pattern Characterized by Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Is Associated with Lower Decision-Making Performance in the Iowa Gambling Task, Elevated Stress Exposure, and Altered Autonomic Nervous System Reactivity in Men and Women. Nutrients, 2023. 15(18).

- Connett, G.J. , Asthma, classical conditioning, and the autonomic nervous system - a hypothesis for why children wheeze. Arch Dis Child, 2024, 109, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennequin, G. , et al., Physically active men present a healthier cardiometabolic profile in response to a balanced meal compared to inactive men. Eur J Appl Physiol, 2023, 123, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzolino, D. , et al., Cardiac autonomic regulation in response to a mixed meal is impaired in obese children and adolescents: the role played by insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2014, 99, 3199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzo, A. , et al., Mediterranean meal versus Western meal effects on postprandial ox-LDL, oxidative and inflammatory gene expression in healthy subjects: a randomized controlled trial for nutrigenomic approach in cardiometabolic risk. Acta Diabetol, 2017, 54, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönknecht, Y.B. , et al., APOE ɛ4 Is Associated with Postprandial Inflammation in Older Adults with Metabolic Syndrome Traits. Nutrients, 2021. 13(11).

- Ade, C.J., S. K. Rosenkranz, and C.A. Harms, The effects of short-term fish oil supplementation on pulmonary function and airway inflammation following a high-fat meal. Eur J Appl Physiol, 2014, 114, 675–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauer, S.R. , et al., Publication guidelines and recommendations for pupillary measurement in psychophysiological studies. Psychophysiology, 2022, 59, e14035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferencová, N. , et al., Eye pupil - a window into central autonomic regulation via emotional/cognitive processing. Physiol Res, 2021. 70(Suppl4): p. S669-s682.

- Jenkins, Z.M. , et al., Autonomic Nervous System Function in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review. Front Neurosci, 2021, 15, 682208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang, J. , et al., Parasympathetic Activity and Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness in Athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2016, 48, 2100–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D. , et al., Meal-exercise challenge and physical activity reduction impact on immunity and inflammation (MERIIT trial). Contemp Clin Trials Commun, 2018, 10, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbo, P. , et al., Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 2002, 102, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweik, R.A. , et al., An official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2011, 184, 602–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoracic, S. , ATS/ERS recommendations for standardized procedures for the online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide, 2005. J Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2005, 171, 912–930. [Google Scholar]

- Excellence, N.I.f.C. , Measuring fractional exhaled nitric oxide concentration in asthma: NIOX MINO, NIOX VERO and NObreath. 2014.

- Miller, M.R. , et al., Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J, 2005, 26, 319–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, GLI-2012 Excel Sheet Calculator. J Global Lung Function Initiative, 2013.

- Couto, M. , et al., Exploratory study comparing dysautonomia between asthmatic and non-asthmatic elite swimmers. Rev Port Pneumol (2006), 2015, 21, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Committees, G.E.a.S. From the Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2015. 2015.

- Organization, W.H. Global Database on Body Mass Index: BMI Classification.. [cited 2015; Available from: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp.

- Lu, C.L. , et al., Postprandial changes of sympathovagal balance measured by heart rate variability. Dig Dis Sci, 1999, 44, 857–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, N. , et al., The effect of a high-carbohydrate meal on postprandial thermogenesis and sympathetic nervous system activity in boys with a recent onset of obesity. Metabolism, 2005, 54, 430–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halnes, I. , et al., Soluble Fibre Meal Challenge Reduces Airway Inflammation and Expression of GPR43 and GPR41 in Asthma. Nutrients, 2017. 9(1).

- Kurti, S.P. , et al., Does moderate intensity exercise attenuate the postprandial lipemic and airway inflammatory response to a high-fat meal? Biomed Res Int, 2015, 2015, 647952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilleminault, L. , et al., Diet and Asthma: Is It Time to Adapt Our Message? Nutrients, 2017. 9(11).

- Rodrigues, M. , et al., Diet and Asthma: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci., 2023, 13, 6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorli-Aguilar, M. , et al., Dietary patterns are associated with lung function among Spanish smokers without respiratory disease. BMC Pulm Med, 2016, 16, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, H. , et al., Association between the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Asthma in Adults from Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil. Nutrients, 2023. 15(14).

- Mattos, S. , et al., Effects of weight loss through lifestyle changes on heart rate variability in overweight and obese patients: A systematic review. Clin Nutr, 2022, 41, 2577–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, D. , et al., Effect of Low-Energy Diets Differing in Fiber, Red Meat, and Coffee Intake on Cardiac Autonomic Function in Obese Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2015, 38, 1750–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, Y. , et al., Higher energy intake at dinner decreases parasympathetic activity during nighttime sleep in menstruating women: A randomized controlled trial. Physiol Behav, 2018, 194, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polutchko, S.K., G. N.E. Glime, and B. Demmig-Adams, Synergistic Action of Membrane-Bound and Water-Soluble Antioxidants in Neuroprotection. Molecules, 2021. 26(17).

- Dai, J. , et al., Mediterranean dietary pattern is associated with improved cardiac autonomic function among middle-aged men: a twin study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, 2010, 3, 366–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tentolouris, N. , et al., Differential effects of high-fat and high-carbohydrate isoenergetic meals on cardiac autonomic nervous system activity in lean and obese women. Metabolism, 2003, 52, 1426–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, A.C. , et al., Provitamin A Carotenoid-Biofortified Maize Consumption Increases Pupillary Responsiveness among Zambian Children in a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Nutr, 2016, 146, 2551–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, K. , et al., Nutritional Status Measures Are Correlated with Pupillary Responsiveness in Zambian Children. J Nutr, 2018, 148, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R.M. and L. Ghiadoni, Polyphenols, Antioxidants and the Sympathetic Nervous System. Curr Pharm Des, 2018, 24, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, H. and T.D. Çapar, Bioactive Compounds of Fruits and Vegetables, in Minimally Processed Refrigerated Fruits and Vegetables, F. Yildiz and R.C. Wiley, Editors. 2017, Springer US: Boston, MA. p. 723-745.

- Papadopoulou, R.T. , et al., The Acute Effect of Meal Timing on the Gut Microbiome and the Cardiometabolic Health of the Host: A Crossover Randomized Control Trial. Ann Nutr Metab, 2020, 76, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalin, R.E. , et al., Mediterranean Diet and Lung Function in Adults Current Smokers: A Cross-Sectional Analysis in the MEDISTAR Project. Nutrients, 2023. 15(5).

- Bakolis, I. , et al., Dietary patterns and respiratory health in adults from nine European countries-Evidence from the GA(2) LEN study. Clin Exp Allergy, 2018, 48, 1474–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Larsen, V. , et al., Dietary antioxidants and 10-year lung function decline in adults from the ECRHS survey. Eur Respir J, 2017. 50(6).

- McDiarmid, K.P. , et al., The Impact of Meal Dietary Inflammatory Index on Exercise-Induced Changes in Airway Inflammation in Adults with Asthma. Nutrients, 2022. 14(20).

- Shi, L. , et al., Assessment of Combination of Automated Pupillometry and Heart Rate Variability to Detect Driving Fatigue. Front Public Health, 2022, 10, 828428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n= 46) |

|

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 26 (57) |

| Age, years (median, 25th-75th) | 25, 22-30 |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 43 (94) |

| Height, cm (mean ±SD) | 169 ±10.4 |

| BMI, n (%) | |

| Average weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) | 25 (54) |

| Overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2) | 17 (37) |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 4 (9) |

| Active smokers, n (%) | 7 (15) |

| Asthma diagnosis, n (%) | 13 (28.3) |

| MdM | FFM | |||||

| Measurements | Before | After | p | Before | After | p |

| Parasympathetic | ||||||

| MaxD, mm (mean ±SD) | 6.03 ±0.78 | 6.20 ±0.77 | 0.043a | 6.07 ±0.85 | 5.98 ±0.85 | 0.249a |

| MinD, mm (mean ±SD) | 3.93 ±0.62 | 3.97 ±0.60 | 0.128a | 3.92 ±0.66 | 3.87 ±0.72 | 0.352a |

| %Con (%) | -36.0 (-38.0; -32.8) | -36.5 (-38.0; -34.0) | 0.072b | -36.5 (-38.0; -33.5) | -36.5 (-39.0; -33.0) | 0.467b |

| Latency, sec | 0.22 (0.21; 0.22) | 0.22 (0.21; 0.24) | 0.461b | 0.22 (0.21; 0.24) | 0.22 (0.20; 0.22) | 0.876b |

| ACV, mm/sec | -4.18 (-4.56; -3.81) | -4.48 (-4.68; -3.98) | 0.035b | -4.20 (-4.59; -3.91) | -4.32 (-4.59; -3.82) | 0.483b |

| MCV, mm/sec | -5.77 (-6.12; -5.08) | -6.13 (-6.55; -5.71) | 0.003b | -5.87 (-6.38; -5.42) | -5.87 (-6.36; -5.44) | 0.324b |

| Sympathetic | ||||||

| ADV, mm/sec (mean ±SD) | 1.00 ±0.24 | 0.93 ±0.23 | 0.030a | 0.92 ±0.26 | 0.93 ±0.19 | 0,.412a |

| T75, sec (mean ±SD) | 2.52 ±0.53 | 2.76 ±0.44 | 0.454a | 2.65 ±0.59 | 1.54 ±0.96 | 0.012a |

| MdM | FFM | |||||

| Measurements | Before | After | p | Before | After | p |

| Lung function | ||||||

| FVC, median (25th; 75th) | 4.08 (3.55; 5.40) | 4.08 (3.44; 4.98) | 0.023b | 4.13 (3.45; 5.52) | 4.19 (3.52; 5.44) | 0.029b |

| FEV1, median (25th; 75th) | 3.67(2.93;4.44) | 3.58(2.94:4.41) | 0.055 b | 3.65(3.03;4.48) | 3.73(3.00;4.45) | 0.245 b |

| FEV1/FVC | 85.7 ±5.43 | 86.2 ±5.20 | 0.311a | 85.6 ±5.70 | 86.3 ±5.29 | 0.118a |

| FEF25/75 | 4.0 ±1.11 | 4.09 ±1.21 | 0.110a | 4.11 ±1.10 | 4.09 ±1.13 | 0.817a |

| Airway inflammation | ||||||

| FeNO, ppb, median (25th; 75th) | 25.7 (16.3; 49.3) | 30.8 (25.6; 62.3) | <0.001b | 25.0 (14.3; 47.0) | 29.3 (17.0; 51.7) | 0.040b |

| Fixed Effects | Random Effects | Model Fit | |||||||

| Intercept | Meal FFM vs. MdM |

Time After vs. Before |

Intercept | Residual | Log-likelihood | AIC | BIC | ||

| MaxD | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 6.09 | -0.08 | 0.04 | -- | -- | -138.56 | 287.13 | 302.50 | |

| SE | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.06 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.47 | 0.17 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.68 | 0.41 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 53.81 | 117.99 | 117.19 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.215 | 0.508 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 8.83 | -0.08 | 0.04 | -- | -- | -140.15 | 300.30 | 331.05 | |

| SE | 0.83 | 0.07 | 0.06 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.40 | 0.17 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.63 | 0.41 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 35.27 | 117.89 | 117.22 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.222 | 0.508 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| MinD | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 3.96 | -0.06 | 0.01 | -- | -- | -98.90 | 207.79 | 223.04 | |

| SE | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.05 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.33 | 0.10 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.58 | 0.32 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 51.20 | 113.80 | 113.05 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.231 | 0.792 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 6.03 | -0.06 | 0.01 | -- | -- | -102.11 | 224.22 | 254.72 | |

| SE | 0.71 | 0.05 | 0.05 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.30 | 0.10 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.55 | 0.32 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 35.03 | 113.76 | 113.19 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.233 | 0.788 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| %Con | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | -35.20 | -0.13 | -0.21 | -- | -- | -376.14 | 762.28 | 777.60 | |

| SE | 0.64 | 0.29 | 0.29 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 14.53 | 3.81 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 3.29 | 1.82 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 48.58 | 115.53 | 114.96 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.651 | 0.470 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | -30.36 | -0.13 | -0.21 | -- | -- | -372.72 | 765.43 | 796.06 | |

| SE | 5.03 | 0.29 | 0.29 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 15.39 | 3.29 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 3.92 | 1.82 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 34.83 | 115.30 | 114.91 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.652 | 0.474 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| ACV | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | -4.21 | 0.13 | -0.04 | -- | -- | -144.81 | 299.62 | 314.62 | |

| SE | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.08 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.17 | 0.25 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.41 | 0.50 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 86.37 | 118.36 | 116.42 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.109 | 0.629 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | -5.03 | 0.12 | -0.04 | -- | -- | -150.01 | 320.01 | 350.01 | |

| SE | 0.58 | 0.08 | 0.08 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.15 | 0.25 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.39 | 0.50 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 34.84 | 117.40 | 115.76 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.127 | 0.624 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| MCV | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | -5.78 | -0.003 | -0.28 | -- | -- | -245.37 | 500.73 | 516.08 | |

| SE | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.35 | 1.01 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.59 | 1.01 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 107.93 | 119.07 | 116.67 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.984 | 0.079 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | -6.34 | -2.61x10-3 | -0.28 | -- | -- | -250.77 | 521.54 | 552.23 | |

| SE | 1.03 | 0.16 | 0.16 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.41 | 0.64 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 1.01 | 1.01 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 35.55 | 118.34 | 116.43 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.987 | 0.079 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| ADV | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 0.97 | -0.02 | -0.03 | -- | -- | 167.48 | -22.95 | -7.93 | |

| SE | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.03 | 0.03 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.16 | 0.17 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 74.79 | 108.15 | 107.24 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.440 | 0.229 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 1.08 | -0.02 | -0.03 | -- | -- | 5.35 | 9.29 | 39.33 | |

| SE | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.03 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.03 | 0.03 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.16 | 0.17 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 33.54 | 107.01 | 106.35 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.482 | 0.233 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| T75 | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 2.98 | -0.67 | -0.54 | -- | -- | -97.76 | 205.52 | 217.56 | |

| SE | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.18 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.16 | 0.61 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.17 | 0.78 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 79.0 | 79.0 | 79.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 3.46 | -0.68 | -0.52 | -- | -- | -97.63 | 215.27 | 239.34 | |

| SE | 0.63 | 0.16 | 0.17 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.10 | 0.53 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.07 | 0.73 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 74.0 | 74.0 | 74.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Fixed Effects | Random Effects | Model Fit | |||||||

| Intercept | Meal FFM vs. MdM |

Time After vs. Before |

Intercept | Residual | Log-likelihood | AIC | BIC | ||

| FVC | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 4.33 | 0.039 | -0.079 | -- | -- | -629.08 | 1302.15 | 1369.67 | |

| SE | 0.16 | 0.023 | 0.023 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 1.027 | 0.021 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 1.013 | 0.146 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 40.82 | 117.07 | 117.01 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.097 | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 1.63 | 0.039 | -0.079 | -- | -- | -14.72 | 75.44 | 146.17 | |

| SE | 1.35 | 0.023 | 0.023 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.963 | 0.021 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.981 | 0.146 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 21.98 | 117.01 | 116.98 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | 0.238 | 0.096 | <0.001 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| FEV1 | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 3.70 | 0.02 | -0.04 | -- | -- | -75.21 | 160.42 | 170.53 | |

| SE | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.02 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.66 | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.81 | 0.11 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 40.76 | 117.06 | 117.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.186 | 0.017 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 2.18 | 0.02 | -0.04 | -- | -- | -14.72 | 75.44 | 146.17 | |

| SE | 1.15 | 0.017 | 0.018 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 0.71 | 0.84 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.013 | 0.11 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 21.99 | 117.02 | 116.99 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | 0.072 | 0.186 | 0.017 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| FEV1/FVC | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 102.52 | 0.32 | 0.83 | -- | -- | -430.14 | 870.28 | 885.63 | |

| SE | 1.0 | 0.39 | 0.39 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 36.38 | 5.90 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 6.03 | 2.43 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 18.76 | 113.45 | 114.32 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.411 | 0.033 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 123.91 | 0.31 | -2.31 | -- | -- | -379.58 | 805.17 | 875.75 | |

| SE | 7.59 | 0.39 | 1.21 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 29.13 | 5.90 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 5.40 | 2.43 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 22.12 | 116.39 | 22.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.433 | 0.06 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| FEF25/75 | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 4.03 | 0.005 | 0.04 | -- | -- | -204.30 | 418.59 | 434.38 | |

| SE | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.04 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 1.22 | 0.07 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 1.11 | 0.26 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 42.27 | 117.17 | 117.01 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.905 | 0.349 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 4.61 | 0.004 | 0.830 | -- | -- | -104.90 | 219.80 | 235.18 | |

| SE | 1.35 | 0.04 | 0.39 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 1.26 | 1.12 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 0.07 | 0.26 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 22.03 | 117.13 | 116.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | 0.002 | 0.922 | 0.349 | -- | .-- | -- | -- | -- | |

| FeNO | |||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 44.08 | -4,15 | 3.79 | -- | -- | -705.05 | 1422.09 | 1440.51 | |

| SE | 6.81 | 2.19 | 2.16 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 1758.83 | 185.82 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 41.94 | 13.63 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 44.19 | 116.37 | 116.08 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | <0.001 | 0.058 | 0.083 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Estimate | -7.01 | -4.22 | 3.80 | -- | -- | -629.08 | 1302.15 | 1369.67 | |

| SE | 56.95 | 2.19 | 2.16 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Variance | -- | -- | -- | 1776.84 | 42.15 | -- | -- | -- | |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 185.82 | 13.63 | -- | -- | -- | |

| DF | 23.08 | 116.07 | 116.07 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| p | 0.903 | 0.057 | 0.082 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).