Introduction

The levels of analysis perspective is well known in some branches of organismal biology. The idea goes back to the early ethologists, particularly Tinbergen, who pointed out that biological explanations for why an animal has a particular trait can come in many non-mutually exclusive forms (Tinbergen 1963; Sherman 1988; Sherman 1989). These forms tend to be associated with different branches of biology (although this is not always the case). For example, when considering why an animal has trait X, it is often pointless for a geneticist to argue with an evolutionary biologist focused on adaptation because they tend to seek non-mutually exclusive explanations. That the animal has a highly derived gene (or pathway), for example, which could be a cause for the presence or absence of the trait at the species level, is simply independent of the adaptive function of the trait. Moreover, there are developmental considerations having both to do with genetics, and the environment that also may affect our hypothetical trait X and are again, in most cases, non-mutually exclusive with respect to other explanations.

The levels of analysis perspective is not well known in every branch of biology, however. The cause may be that these ideas can appear obvious when stated in general terms and many scientists who know these things intuitively (even if they are not in possession of the jargon) see little need to belabor these points. However, this belief is misguided because there are cases in which the need to be explicit about such things is necessary. Further, such cases are not bizarre exceptions to the rule, but rather difficult problems that demand a consistent logical approach. The field of behavioral ecology, for example, had a period of time in the 1970s and 80s when difficult questions of this sort caused much acrimonious debate (Symons 1979; Gould 1987; Gould 1987; Sherman 1989). The cause of the male-like penises of female hyenas is a case in point. Some hypothesized that the trait was due to the high testosterone levels needed for female dominance (hyenas are matriarchal) causing the development of secondary male sexual characteristics as a side effect (Symons 1979; Gould 1987). Others pointed out that the female penises are used in communication and thus cannot be non-adaptive side effects (Alcock 1987). With a levels of analysis approach that separates the evolutionary origin (byproduct of high testosterone for other functions) with the current adaptive utility (signaling), the disagreement was largely resolved (Sherman 1989). There are many such cases, and they are well known to behavioral ecologists (Sherman 1988).

This paper argues that logical inconsistency of the sort meant to be corrected by the levels of analysis approach is currently causing confusion in the field of evolutionary genetics. Here, the question is not what a trait is for, but rather what a gene is for, and to what extent genes are either conserved across distant clades, or unique. As we will see, evolutionary origin explanations and current utility (mechanistic functional explanations) are often conflated in the literature when it comes to these issues causing unnecessary and counterproductive discussion (Moyers and Zhang 2015; Moyers and Zhang 2016; Weisman et al. 2020b; Vakirlis et al. 2020b; Vakirlis et al. 2020a; Zile et al., 2020; Weisman 2021; Zeeshan Fakhar et al. 2023). We will focus on orphans (and lineage specific genes in general), as it is here that the confusion is the most pronounced. However, much of what is said will be generally relevant for how we determine the history and function of genes (particularly for the fields of comparative genomics and bioinformatics).

The Levels of Analysis

I will not engage in a long-winded discussion about the nature of the levels of analysis approach because the body of the paper will provide an ideal example. It is worth fleshing the idea out a bit, however, before beginning our discussion of genes. The basic idea is twofold. First, there is a fundamental divide between ultimate and proximate causation, such that ideas across these categories are almost never in competition. In biology, ultimate causation has to do with why questions, and tends to focus on the issue of adaptation (Tinbergen 1963). Birds have feathers because they either need them to keep warm or because they are important for flight, for example. Proximate questions are essentially how questions: how are feathers produced at the genetic, developmental, or physiological levels? The second aspect of the levels of analysis perspective is that within the realm of either ultimate or proximate causation there are also non-mutually exclusive hypotheses. For ultimate causation, these tend to be associated with questions of origin versus current utility, as these can vary sharply. For proximate explanations, these tend to have to do with explorations focused on either genetics, physiology, development, and so forth, generally not being in competition with one another. Work within these realms overlaps, of course, but they are rarely in direct competition. The work of the geneticist and the physiologist not taking a genetic approach, for example, are usually complementary.

Assigning gene function, orphan genes, and genetic novelty

We assign function (and give a name) to a gene in many ways that broadly speaking fall into two categories (Doolittle 1981; Sivashankari and Shanmughavel 2006; Tautz and Domazet-Loso 2011). The first is the old-fashioned method of identifying and exploring a gene’s function experimentally. We will not concern ourselves much with this in the present paper, as it is obviously the gold standard. We will reference such work, of course, when analyzing how well the second method might be working. The second method is to predict function. These approaches come in many forms that vary in their power. For example, we have identified many protein domains that provide specific functions to a gene (Doolittle 1995; Mao et al. 2005, Kanehisa et al. 2016,). Sometimes the presence of such domains in a gene is enough to suggest that it has a particular function and falls into a known gene family. We also have computational tools, which have increased in power in recent years, which can predict protein folding (with variable accuracy), factor in the presence of known domains (and key amino acids in them) and their placement in the three-dimensional structure, in order to give a predictive function (Bock and Gough 2001; Laskowski et al. 2005; Lee et al. 2007; Cooper et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2020,). Finally, we have simple blast searches in which a gene with unknown function is compared to many with known functions. If a significant degree of alignment is found the gene is presumed to be a homolog of the matched gene and the assumption is that it probably has the same, or a similar, function (Dennis et al. 2003; Conesa et al. 2005; Gotz et al. 2008; Seemann 2014; Tatusova et al. 2016; O’Leary et al. 2016). This paper will be primarily concerned with this final approach, and its logical foundation.

We reviewed the naming of genes, and assignment of function, in order to provide some backstory for novel genes. These are genes unique to particular organisms, in which case they are called orphans, or genes found in particular clades only, in which case they are called taxonomically restricted genes (TRGs) (Wilson et al. 2005; Khalturin et al. 2008; Milde et al. 2009; Foret et al. 2010; Johnson and Tsutsui 2011a; Zielezinski et al. 2023). In order to frame the discussion of these genes further its useful to stress that in the early days of biology it seems to have been thought that TRGs were standard. People naively thought beetles had beetle genes, for example, while humans had human genes (Carroll 2005). With Watson and Crick’s elucidation of the structure of DNA (using Franklin’s data and Pauling’s approach to model building), it became clear that the building blocks of life, particularly genes, could be more standardized across species than previously thought (Pauling and Corey 1951; Watson and Crick 1953; Franklin and Gosling 1953b; Franklin and Gosling 1953a). This idea came to fruition with the discovery of hox genes, which are almost universally conserved in the animals, and which play similar roles in clades separated by hundreds of millions of years (Duboule and Dolle 1989; Chisaka and Capecchi 1991; Krumlauf 1994; Burke et al. 1995; Averof and Akam 1995; Carroll 2000; Carroll 2001). This discovery (and more that followed) led to the toolkit paradigm in which we currently reside. Here, the basic idea is that most animals have the same set of genes (at least with respect to the most important ones) and when novelty emerges at the phenotypic level, it is the result of the new use of these genes (changes to their regulatory or sometimes coding sequences) (Arthur 2002; Beldade and Brakefield 2002; Wagner et al. 2007; Carroll 2008; Rokas 2008; Wagner and Lynch 2008). This approach, strongest in the field of evolutionary developmental biology, fits nicely into the model system paradigm, of course, since it provides a foundation for why we can study mice, or fruit flies, to improve our understanding of human health.

The toolkit genes, like the hox transcription factors, were experimentally identified. Once found in the model system, their sequences could be used to design primers to search for the same genes, using PCR, in other species. This process of looking for known genes in non-model systems based on what was found to be important in the model system went on for many decades and the success of this approach is largely responsible for our confidence in the toolkit paradigm. Of course, a blind spot is that one cannot find what one is not looking for and this process is sure to miss the role of novel genes, should they exist. This became apparent with the production of whole genomes and the publishing of official genes sets (OGS). An OGS is thought to be the complete list of genes present in a species. OGSs are obviously incomplete and always growing, but they quickly challenged the paradigm surrounding the ratio of toolkit genes to TRGs because the earliest genomes showed far larger numbers of TRGs (about 10-20% of the OGS) than expected (Domazet-Loso and Tautz 2003; Wilson et al. 2005; Wilson et al. 2007; Khalturin et al. 2009; Tautz and Domazet-Loso 2011; Yang et al. 2013; Zielezinski et al. 2023; Fakhar et al. 2023; Zeeshan Fakhar et al. 2023). Moreover, as more genomes were produced, and as their annotations improved, this ratio stayed the same.

Studies by many authors in the last couple of decades have shown that TRGs play many important lineage specific roles (Domazet-Loso and Tautz 2003; Wilson et al. 2005; Wilson et al. 2007; Khalturin et al. 2008; Sunagawa et al. 2009; Toll-Riera et al. 2009a; Toll-Riera et al. 2009b; Johnson and Tsutsui 2011b; Voolstra et al. 2011; Wissler et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2013; Heames et al. 2020; Jiang et al. 2022; Fakhar et al. 2023). These functions come in many forms, ranging from core biological processes necessary for all life, to traits that define the lineage specific functions of particular clades (Khalturin et al. 2009; Sumner 2014; Verster et al. 2017; Johnson 2018; Jiang et al. 2022; Fakhar et al. 2023). For example, the genes that underlie photosynthesis are TRGs unique to species that photosynthesize. They are not toolkit genes found across all clades. Many venomous animals depend on TRGs for their toxic qualities, while the immune systems of many clades harbor important TRGS (Sackton et al. 2013; van der Burg et al. 2016; Grashof et al. 2019; Chong et al. 2019; Whitelaw et al. 2020). Narrower still, much unique social biology of honey bees is due to TRGs, while gall forming insects have evolved thousands of orphans to commandeer plant physiology (Ferreira et al. 2013; Jasper et al. 2015; Zhao et al. 2015; Sumner et al. 2023). The characteristic stinging cells of cnidarians, nematocytes, are also dependent on TRGs, as are some of the genes important for producing shells in Mollusks (Milde et al. 2009; Kocot et al. 2016). One could go on and on with such examples.

Although much work demonstrates the importance of TRGs, there is still considerable skepticism regarding their general importance. This comes in two forms. First, such genes are often ignored or downplayed in general discussions of evolutionary genetics. Second, and more important for the present paper, many authors question the assignment of genes to an orphan or other TRG category (Weisman et al. 2020b; Vakirlis et al. 2020b; Zile et al. 2020; Weisman 2021; Bozorgmehr 2023). Weisman et al. (2020b), for example, is a recent example of such a paper. Here it was argued that genes said to be orphans are actually not orphans because the authors found their homologs in related taxa. In such work, finding the ortholog can either mean using more powerful alignment-based techniques, lowering the threshold for a significant match, or using synteny to show that what has been called an orphan (and novel to one clade) actually evolved from a gene present elsewhere (Moyers and Zhang 2015; Vakirlis et al., 2020b; Weisman et al. 2020a; Zile et al. 2020; Bozorgmehr 2023). In this light it was shown, for example, that 11 yeast genes thought to be orphans have homologs that reside in the same position in a related organism.

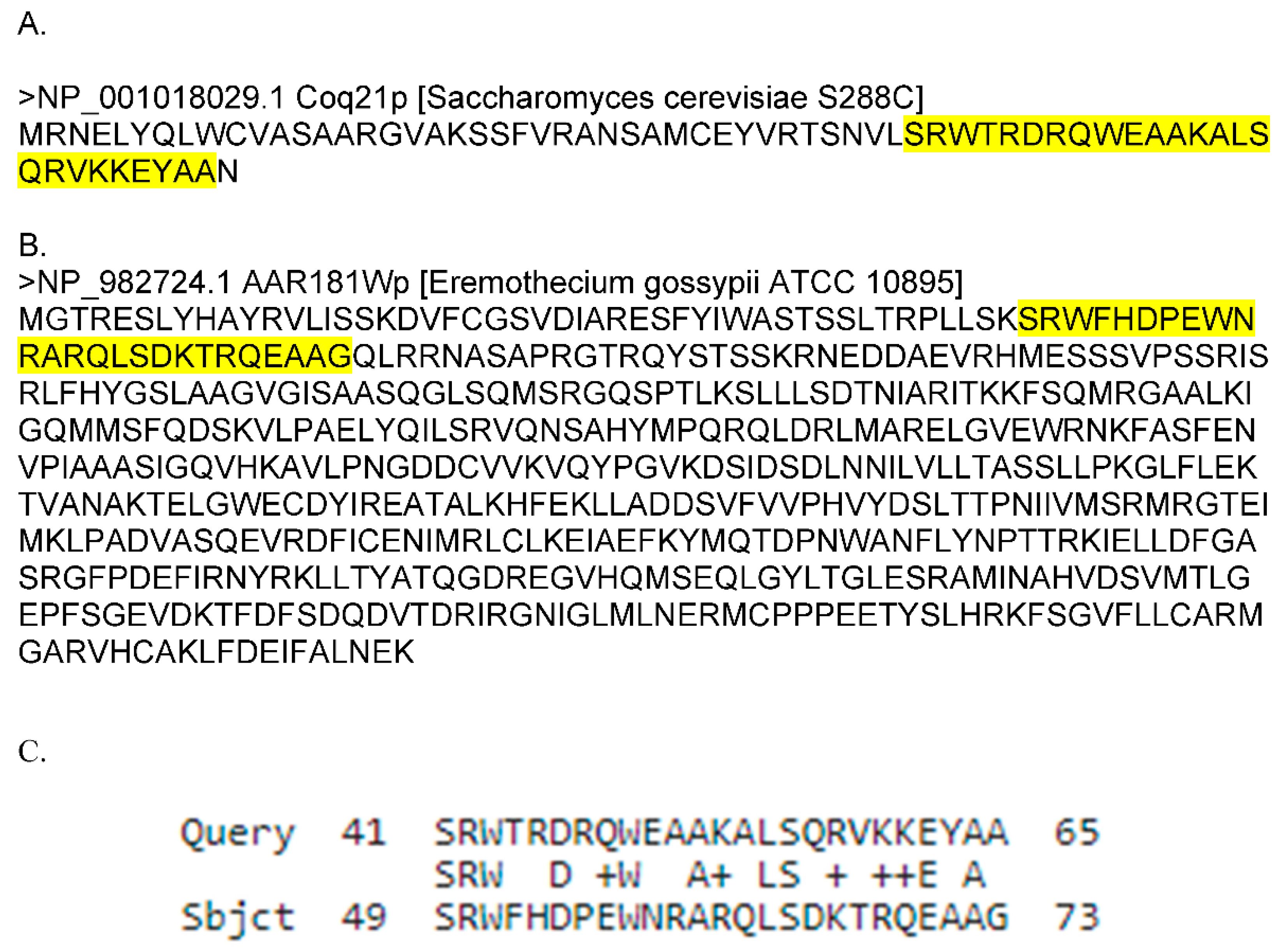

Figure 1 shows the alignment between one of these genes and its purported homolog and is reflective of the general nature of such alignments. The orphan is 66 aa long while the purported homolog is 543 aa long. The alignment is quite small (24 aa) and does not contain a classified domain. A known domain (ABC1_ADCK3) is present on the larger gene, while none are present on the orphan. Weisman et al. (2020) seem to imply that such genes tend to retain their ancestral functions, and there is nothing novel (or special) about them.

Responding to this skeptical work on TRGs will allow us to challenge and explore some assumptions of how we think about evolutionary genetics. This is because this need to challenge whether a gene is novel, and to think that we can assign function at all based common ancestry, violates the levels of analysis with respect to evolutionary origin and current utility. In other words, the present approach of naming genes based on their crude similarity to genes of known function (minus information from domains or other more information rich sources) is known to be error-prone and such assignments are meant to be taken with a grain of salt. We go further to argue that the approach is fundamentally flawed and should be discontinued.

Origin and evolutionary elaboration of genes for novel functions

Before we can explain the fallacious nature of some evolutionary tree reasoning, we must first discuss the origin, elaboration, and function of novel genes in mechanistic terms. With this knowledge we can better understand why and where the analogy between species trees and gene trees breaks down and why it is relevant for assigning function to genes. There seem to be two ways that novel genes evolve. First, they can evolve denovo from noncoding sequence and second, they can evolve by radically changing other genes to give them new functions, often with the help of genomic parasites (Doolittle 1981; Conant and Wagner 2003; Conant and Wolfe 2008; Kaessmann 2010; Tautz and Domazet-Loso 2011; Carvunis et al. 2012; McLysaght and Guerzoni 2015; Cosby et al. 2021). We will mainly discuss the second category as it is more essential to our argument about the error of reasoning from origin to function.

We will illustrate briefly denovo gene birth using data collected by Begun and coauthors on Drosophila (Begun et al. 2006; Begun et al. 2007). This work has shown that small denovo genes spread through the population in a classic population genetic manner before becoming fixed. Presumably in such cases, though the data are preliminary, one or more mutations create a promoter site that triggers expression of whatever protein product can be produced from the bases downstream. Such a protein is undoubtedly small and probably often not of use. In the rare cases when the protein is beneficial, selection leads to the spread of the gene, and later, perhaps, its elaboration in length and functional properties (Carvunis et al. 2012).

We now turn to the essential part of this section, which is concerned with neofunctionalization. Let’s start with some illustrative examples. Some (not all) venoms appear to evolve from digestive enzymes (Kochva et al. 1983; Valdez-Cruz et al. 2007). Phospholipase A2 for example, is abundant in many venoms but also in mammalian pancreatic juices, and other digestive compartments (Valdez-Cruz et al. 2007). The venom form of phospholipase A2 differs somewhat in structure from those serving the ancestral digestive function but the overlap is large and includes functional elements (

Figure 2). Thus, we have the evolution of a new gene class (venoms) that share functionality, breaking down membranes in this case, with their ancestral homologs. Using the ancestral function as a proxy for the current utility in this case is therefore incorrect (a venom is not a digestive enzyme) but not wildly off base. Now consider genes such as the crystallin proteins (Fernald 2006; Roskamp et al. 2020) which makes up the bulk of the vertebrate lens. These genes also have strong sequence similarity to their homologs, but unlike venoms, the relationship between the ancestral function and the current utility is highly complex (Slingsby et al. 2013). There are several classes of crystallin proteins. The most ancient groups, the ά-, β-, and γ-crystallins, evolved from heat shock proteins and probably serve chaperone-like effect in the lens. Other crystallins, however, are digestive enzymes that sometimes retain their enzymatic activity and sometimes not. Birds, for example, have two closely related crystallins, δ1, and δ2. They share strong sequence similarity but δ2, argininosuccinate lyase, retains its enzymatic activity, while δ1 is a lens specific protein with no enzymatic role (

Figure 3). There seems to have been a duplication event early in the lineage leading to birds and reptiles, and in some lineages, there is a shift towards preferred use of δ1 in the eye (Wistow 1993). We will return later to the consequences of such complexity for gene annotation, but, essentially, even strikingly high degrees of similarity between two genes need not imply functional conservation. Finally, consider genes such as those that Weisman et al. (2020), and many others, have studied, in which there is no sequence similarity, but their ancestor can be inferred based on synteny (or lowering blast hit thresholds to the point where practically any alignment, no matter how short, will cause a significant hit). In this case, the evolutionary change is so complete that there is little chance of functional overlap. How can one possibly infer functional conservation from the tiny overlap we saw in

Figure 1. Conversation of function may exist, but can such an alignment show it? Perhaps if the region of alignment was a domain one could draw some functional inference, but it is not. Moreover, in many cases, it is known that functional overlap does not exist between a gene and its ortholog so in terms of annotation, what is point of referencing historical origin?

To flesh out the argument of the previous chapter, consider an anthropomorphic analogy. In the old days when various tape devices were used to store information, such as music and movies, it was common to reuse old tapes when new ones were unavailable. If I wanted to record a movie, I might record over a tape already containing some other movie. In such a case the old movie was lost, and a new one took its place. In terms of the current utility of that tape, its history (the fact that it was used to store another movie) is irrelevant as once overwritten that old movie is irretrievable. Consider now how evolution may be operating in cases in which conservation of sequence falls to near zero for homologs. After duplication, for example, or when many genes serve overlapping functions, selection can lead to neofunctionalization of one or more of the homologs (Zhang 2003; Conant and Wagner 2004; Nei and Rooney 2005; Conant and Wolfe 2008; Innan and Kondrashov 2010; Van De Peer et al. 2017). The basic idea is that keeping both genes is less selectively advantageous than changing the function of one (reviewed in Conant and Wagner 2004). Sometimes neofunctionalization is partial and a gene clearly remains part of its ancestral gene family, but there is nothing stopping selection (in some cases) from doing what we used to do with VCR tapes, which is to overwrite completely and make a whole new gene. In such cases, there would be no sequence similarity, no protein folding similarity, no functional overlap whatsoever between the old gene and the new one. Essentially, a new gene would have been created. Not from scratch, but by overwriting the gene structure (exons, introns, promotors, etc.) of another gene.

I suspect that this last method of novel gene formation (writing over an old gene) may be more important than denovo gene formation for a number of reasons. First and foremost, it seems to be simpler in a manner analogous to how selection can often make use of standing genetic variation to shift a phenotypic trait without the need for new mutations (Hermisson and Pennings 2005; Barrett and Schluter 2008). In the case of what I will call, “overwriting” a complete gene model with structure including exons, introns, and promoters, is present and all selection has to do is write over it by favoring nucleotide changes. This is in contrast to starting from scratch in which case new coding and regulatory regions must coevolve. This certainly happens, but as for the role of mutations in evolution, I suspect this mechanism provides a foundational sort of process for new gene formation, while most new genes (like most new phenotypes) are made by making use of what is already present. Essentially, why make from scratch what you can make by reusing old moderately redundant parts?

Fallacious evolutionary tree reasoning

The contemporary method of assigning gene function based on homology is based, in spite of the known differences between the two, on a vague transfer of evolutionary reasoning from the species to the gene level (Nichols 2001; Rosenberg 2002; Letunic and Bork 2016). Species that are closely related are typically more similar to one another than are those more distantly related, and in most cases the genes of closely related species are more similar than they are to their homologs in more distant clades. However, gene trees are only analogous to species trees meaning the logic of species tree thinking cannot automatically be transferred to genes. In this section, we make a case for this assertion, and our conjecture that assigning function to genes based on ancestry violates the levels of analysis distinction between origin and current utility.

To show the error of applying the logic of species trees to gene trees, consider that members of a monophyletic group can all be said to be members of the same clade. This is true no matter how radically diverged members of the clade become. Termites, for example, used to be their own order but genome level data confirmed that they are evolutionarily nested within the roaches (Lo et al. 2000; Inward et al. 2007). They are now often thought of as wood-eating highly social roaches. Many such cases of systematic reorganization resulted from tree building with genomic data. However, there was never any rationale for thinking that termites were novel, or brand new. In fact, it was long known that they were closest to roaches, it was just not clear how close (Thorne and Carpenter 1992). Essentially, selection cannot overwrite a species. The thousands of genes underlying a species’ biology cannot shift but so much, Further, there is no spontaneous generation of species. They always come from ancestors back to the origin of life. Hence, the denovo formation of genes has no analogous process in speciation. In sum, there is neither overwriting nor denovo species formation in species trees, while these processes are important to the evolution of genes.

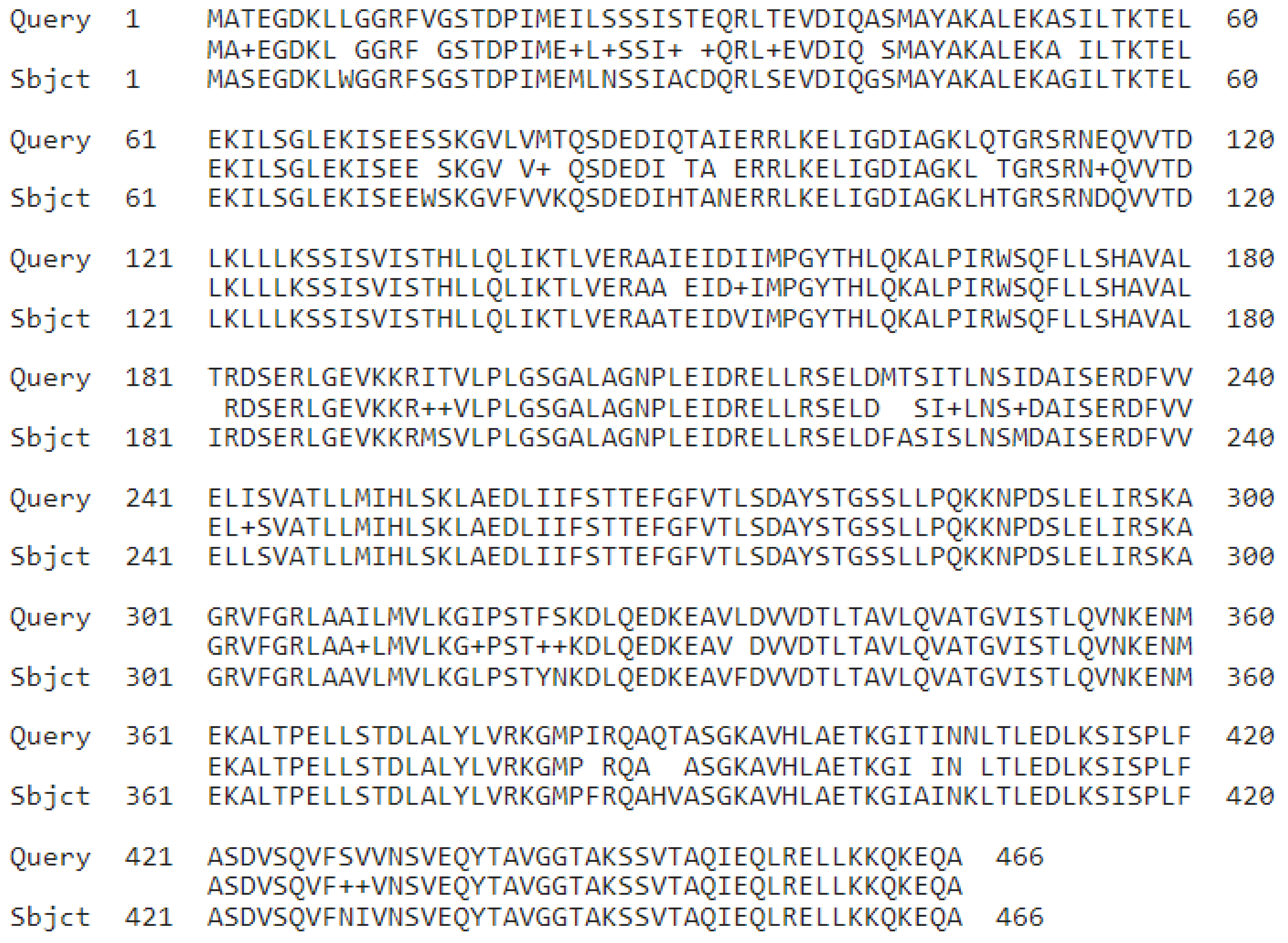

Let’s now return to the crystallin proteins (Fernald 2006; Roskamp et al. 2020), which make up the bulk of the lens material in vertebrate eyes and have long been known to have evolved from metabolic genes that often served radically different roles. In this case, crystallin proteins are easy to localize, their function is rather obvious, and they were experimentally explored long before the genomic era. But what of genes with similar histories that are not easy to experimentally explore? In a new well-assembled genome such genes will give strong blast hits (such as seen in

Figure 3) to their homologs and whatever function those homologs have will be falsely written into the name of the gene. How common this problem is, of course, is wholly unknown but there is no reason to think it uncommon. More common still, however, is the situation exemplified by the yellow proteins. These genes, first identified in

Drosophila, have variable functions within the fly and genes descended from them have even more variable functions in other clades (Wittkopp et al. 2002; Han et al. 2002; Ferguson et al. 2011). The royal jelly proteins, the most famous of which are those fed to the honey bee larva to aid in queen differentiation, are a tandem array of genes arising from duplication of yellow genes (Drapeau et al. 2006; Peixoto et al. 2009; Buttstedt et al. 2014; Albert et al. 2014). In the Hymenoptera, where they have received the most attention, they are expressed in many tissues, and seem to have many functions since the proteins are derived in sequence (Albert et al. 1996; Albert et al. 1999a; Albert et al. 1999b; Buttstedt et al. 2013; Buttstedt et al. 2014). Gene families that appear have highly variable functions within and across clades may be hotspots for the evolution of novel genes. For such genes, there is utility in exploring their evolutionary history, but this history probably has little to do with their current role. Hence naming such genes based on their history is bad practice, since names are typically meant to suggest function.

The importance of leaving unknowns as unknowns

Assigning functions based on blast hits alone is known to be problematic. However, problematic and fundamentally flawed are different things. A core point of this paper is that no answer is generally better than the wrong answer, particularly if the wrong answer is based on little more than bias towards having placeholder answers in place. In general, when we have an answer, even one not initially persuasive, there is a risk that it will come to have the aura of conventional wisdom. Conventional wisdom is difficult to overcome, even when the data against it are clear. Essentially, when there is an answer one must spend time proving it is wrong before one can move on to exploring what the true answer is. This wastes time and labor. It is far better to simply leave unknowns as unknowns, so that whoever chooses to work on them can start with a clean slate.

To make concrete the point of the last chapter. Homology data is useful information and should be included with what is known of a given gene. The point I make is that it can never be enough to prove function, and hence, if this is all we have then the gene should not get a name. Simply leaving it as unknown gene X, about which the following information is known (homology, domains, SLIMs, places of expression, etc.) is a clear unbiased starting point for gene annotation. This further allows us to better estimate how much we really know about genetics, since the number of genes about which we have real experimental information will be easier to quantify. Moreover, unknowns cry out for a search into their function, attracting interest, particularly when the gene is highly expressed and or has other interesting properties. False names, and false senses of knowing what a gene does, can stifle such interest.

To conclude, only experimental evidence is sufficient for naming genes (assigning function) and until it is collected genes should remain as genes of unknown function. Whether presence or absence of a given domain, domain presence plus predicted function from modeling, place and or time of expression, or a study showing cause and effect is sufficient experimental evidence for annotation is a subject for another paper. Here we simply point out that evidence about a gene’s origin and history alone is useful but inappropriate for assigning current function.

Conclusions

The evolution of new genes has received less attention than has the preservation and reuse of conserved genes. This is for several reasons. First, conserved genes are easier to study than novel genes since results from model system can be leveraged in other contexts. Second, conserved genes are those that lend themselves best to the model system paradigm and the use of animals for addressing questions of human health. Lineage specific genes relating to traits not found in humans are obviously not competitive for medical funding and will usually receive less study. The fact that they are less important for medicine, however, does not mean that they are less important for biology. This paper clears up some issues relating to the nature of novel gene formation, particularly overwriting, and will hopefully increase attention on the exploration of novel genes and lineage specific traits. To put it simply, it is thought that the most recent common ancestor of all extant clades had a modest number of genes (Goldman et al. 2013). The millions of genes that have evolved across the tree of life must therefore be the result of fundamentally important processes that lead to new gene formation. Within this paradigm, the creation of new genes must be commonplace, and the default position should not be one of extreme skepticism when one argues that a particular gene appears to be novel to a species or clade.

Acknowledgements

I thank Phil Ward for feedback on the manuscript. This work was funded by a hatch grant to Brian Johnson, CA-D-ENM-2161-H.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no financial interests.

References

- ALBERT, S., BHATTACHARYA, D., KLAUDINY, J., SCHMITZOVA, J. & SIMUTH, J. 1999a. The family of major royal jelly proteins and its evolution. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 49, 290-297. [CrossRef]

- ALBERT, S., KLAUDINY, J. & SIMUTH, J. 1996. Newly discovered features of the updated sequence of royal jelly protein RJP571; longer repetitive region on C-terminus and homology to Drosophila melanogaster yellow protein. Journal of Apicultural Research, 35, 63-68.

- ALBERT, S., KLAUDINY, J. & SIMUTH, J. 1999b. Molecular characterization of MRJP3, highly polymorphic protein of honeybee (Apis mellifera) royal jelly. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 29, 427-434. [CrossRef]

- ALBERT, S., SPAETHE, J., GRUBEL, K. & ROSSLER, W. 2014. Royal jelly-like protein localization reveals differences in hypopharyngeal glands buildup and conserved expression pattern in brains of bumblebees and honeybees. Biology Open, 3, 281-288. [CrossRef]

- ALCOCK, J. 1987. Ardent adaptationism. Natural History, 96, 4.

- ARTHUR, W. 2002. The emerging conceptual framework of evolutionary developmental biology. Nature, 415, 757-764. [CrossRef]

- AVEROF, M. & AKAM, M. 1995. HOX GENES AND THE DIVERSIFICATION OF INSECT AND CRUSTACEAN BODY PLANS. Nature, 376, 420-423. [CrossRef]

- BARRETT, R. D. H. & SCHLUTER, D. 2008. Adaptation from standing genetic variation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23, 38-44. [CrossRef]

- BEGUN, D. J., LINDFORS, H. A., KERN, A. D. & JONES, C. D. 2007. Evidence for de novo evolution of testis-expressed genes in the Drosophila yakuba Drosophila erecta clade. Genetics, 176, 1131-1137.

- BEGUN, D. J., LINDFORS, H. A., THOMPSON, M. E. & HOLLOWAY, A. K. 2006. Recently evolved genes identified from Drosophila yakuba and Drosophila erecta accessory gland expressed sequence tags. Genetics, 172, 1675-1681. [CrossRef]

- BELDADE, P. & BRAKEFIELD, P. M. 2002. The genetics and evo-devo of butterfly wing patterns. Nature Reviews Genetics, 3, 442-452. [CrossRef]

- BOCK, J. R. & GOUGH, D. A. 2001. Predicting protein-protein interactions from primary structure. Bioinformatics, 17, 455-460. [CrossRef]

- BOZORGMEHR, J. H. 2023. Four classic de novo genes all have plausible homologs and likely evolved from retro-duplicated or pseudogenic sequences. bioRxiv, 05. [CrossRef]

- BURKE, A. C., NELSON, C. E., MORGAN, B. A. & TABIN, C. 1995. HOX GENES AND THE EVOLUTION OF VERTEBRATE AXIAL MORPHOLOGY. Development, 121, 333-346. [CrossRef]

- BUTTSTEDT, A., MORITZ, R. F. A. & ERLER, S. 2013. More than royal food - Major royal jelly protein genes in sexuals and workers of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Frontiers in Zoology, 10. [CrossRef]

- BUTTSTEDT, A., MORITZ, R. F. A. & ERLER, S. 2014. Origin and function of the major royal jelly proteins of the honeybee (Apis mellifera) as members of the yellow gene family. Biological Reviews, 89, 255-269. [CrossRef]

- CARROLL, S. B. 2000. Endless forms: the evolution of gene regulation and morphological diversity. Cell, 101, 577-580.

- CARROLL, S. B. 2001. Homeobox genes. American Naturalist, 158, 21-21.

- CARROLL, S. B. 2005. Endless forms most beautiful: The new science of evo devo and the making of the animal kingdom, WW Norton & Company.

- CARROLL, S. B. 2008. Evo-devo and an expanding evolutionary synthesis: A genetic theory of morphological evolution. Cell, 134, 25-36. [CrossRef]

- CARVUNIS, A.-R., ROLLAND, T., WAPINSKI, I., CALDERWOOD, M. A., YILDIRIM, M. A., SIMONIS, N., CHARLOTEAUX, B., HIDALGO, C. A., BARBETTE, J., SANTHANAM, B., BRAR, G. A., WEISSMAN, J. S., REGEV, A., THIERRY-MIEG, N., CUSICK, M. E. & VIDAL, M. 2012. Proto-genes and de novo gene birth. Nature, 487, 370-374. [CrossRef]

- CHISAKA, O. & CAPECCHI, M. R. 1991. REGIONALLY RESTRICTED DEVELOPMENTAL DEFECTS RESULTING FROM TARGETED DISRUPTION OF THE MOUSE HOMEOBOX GENE HOX-1.5. Nature, 350, 473-479. [CrossRef]

- CHONG, H. P., TAN, K. Y., TAN, N. H. & TAN, C. H. 2019. Exploring the Diversity and Novelty of Toxin Genes in Naja sumatrana, the Equatorial Spitting Cobra from Malaysia through De Novo Venom-Gland Transcriptomics. Toxins, 11.

- CONANT, G. C. & WAGNER, A. 2003. Asymmetric sequence divergence of duplicate genes. Genome Research, 13, 2052-2058. [CrossRef]

- CONANT, G. C. & WAGNER, A. 2004. Duplicate genes and robustness to transient gene knock-downs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences, 271, 89-96. [CrossRef]

- CONANT, G. C. & WOLFE, K. H. 2008. Turning a hobby into a job: How duplicated genes find new functions. Nature Reviews Genetics, 9, 938-950. [CrossRef]

- CONESA, A., GOTZ, S., GARCIA-GOMEZ, J. M., TEROL, J., TALON, M. & ROBLES, M. 2005. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics, 21, 3674-3676. [CrossRef]

- COOPER, S., KHATIB, F., TREUILLE, A., BARBERO, J., LEE, J., BEENEN, M., LEAVER-FAY, A., BAKER, D., POPOVIC, Z. & PLAYERS, F. 2010. Predicting protein structures with a multiplayer online game. Nature, 466, 756-760. [CrossRef]

- COSBY, R. L., JUDD, J., ZHANG, R. L., ZHONG, A., GARRY, N., PRITHAM, E. J. & FESCHOTTE, C. 2021. Recurrent evolution of vertebrate transcription factors by transposase capture. Science, 371, 797-+. [CrossRef]

- DENNIS, G., SHERMAN, B. T., HOSACK, D. A., YANG, J., GAO, W., LANE, H. C. & LEMPICKI, R. A. 2003. DAVID: Database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biology, 4.

- DOMAZET-LOSO, T. & TAUTZ, D. 2003. An evolutionary analysis of orphan genes in Drosophila. Genome Research, 13, 2213-2219. [CrossRef]

- DOOLITTLE, R. F. 1981. SIMILAR AMINO-ACID-SEQUENCES - CHANCE OR COMMON ANCESTRY. Science, 214, 149-159. [CrossRef]

- DOOLITTLE, R. F. 1995. THE MULTIPLICITY OF DOMAINS IN PROTEINS. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 64, 287-314.

- DRAPEAU, M. D., ALBERT, S., KUCHARSKI, R., PRUSKO, C. & MALESZKA, R. 2006. Evolution of the Yellow/Major Royal Jelly Protein family and the emergence of social behavior in honey bees. Genome Research, 16, 1385-1394. [CrossRef]

- DUBOULE, D. & DOLLE, P. 1989. THE STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL-ORGANIZATION OF THE MURINE HOX GENE FAMILY RESEMBLES THAT OF DROSOPHILA HOMEOTIC GENES. Embo Journal, 8, 1497-1505. [CrossRef]

- FAKHAR, A. Z., LIU, J., PAJEROWSKA-MUKHTAR, K. M. & MUKHTAR, M. S. 2023. The Lost and Found: Unraveling the Functions of Orphan Genes. Journal of Developmental Biology, 11. [CrossRef]

- FERGUSON, L. C., GREEN, J., SURRIDGE, A. & JIGGINS, C. D. 2011. Evolution of the Insect Yellow Gene Family. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 28, 257-272. [CrossRef]

- FERNALD, R. D. 2006. Casting a genetic light on the evolution of eyes. Science, 313, 1914-1918. [CrossRef]

- FERREIRA, P. G., PATALANO, S., CHAUHAN, R., FFRENCH-CONSTANT, R., GABALDON, T., GUIGO, R. & SUMNER, S. 2013. Transcriptome analyses of primitively eusocial wasps reveal novel insights into the evolution of sociality and the origin of alternative phenotypes. Genome Biology, 14, 14. [CrossRef]

- FORET, S., KNACK, B., HOULISTON, E., MOMOSE, T., MANUEL, M., QUEINNEC, E., HAYWARD, D. C., BALL, E. E. & MILLER, D. J. 2010. New tricks with old genes: the genetic bases of novel cnidarian traits. Trends in Genetics, 26, 154-158. [CrossRef]

- FRANKLIN, R. E. & GOSLING, R. G. 1953a. EVIDENCE FOR 2-CHAIN HELIX IN CRYSTALLINE STRUCTURE OF SODIUM DEOXYRIBONUCLEATE. Nature, 172, 156-157. [CrossRef]

- FRANKLIN, R. E. & GOSLING, R. G. 1953b. THE STRUCTURE OF SODIUM THYMONUCLEATE FIBRES. 1. THE INFLUENCE OF WATER CONTENT. Acta Crystallographica, 6, 673-677. [CrossRef]

- GOLDMAN, A. D., BERNHARD, T. M., DOLZHENKO, E. & LANDWEBER, L. F. 2013. LUCApedia: a database for the study of ancient life. Nucleic Acids Research, 41, D1079-D1082. [CrossRef]

- GOTZ, S., GARCIA-GOMEZ, J. M., TEROL, J., WILLIAMS, T. D., NAGARAJ, S. H., NUEDA, M. J., ROBLES, M., TALON, M., DOPAZO, J. & CONESA, A. 2008. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Research, 36, 3420-3435. [CrossRef]

- GOULD, S. J. 1987. Freudian slip. Natural HIstory, 96, 14-21.

- GOULD, S. J. 1987 Stephen Jay Gould replies. Natural History, 96, 14-21.

- GRASHOF, D. G. B., KERKKAMP, H. M. I., AFONSO, S., ARCHER, J., HARRIS, D. J., RICHARDSON, M. K., VONK, F. J. & VAN DER MEIJDEN, A. 2019. Transcriptome annotation and characterization of novel toxins in six scorpion species. Bmc Genomics, 20. [CrossRef]

- HAN, D., FANG, J. M., DING, H. Z., JOHNSON, J. K., CHRISTENSEN, B. M. & LI, J. Y. 2002. Identification of <i>Drosophila melanogaster</i> yellow-f and yellow-f2 proteins as dopachrome-conversion enzymes. Biochemical Journal, 368, 333-340.

- HEAMES, B., SCHMITZ, J. & BORNBERG-BAUER, E. 2020. A Continuum of Evolving De Novo Genes Drives Protein-Coding Novelty in <i>Drosophila</i>. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 88, 382-398.

- HERMISSON, J. & PENNINGS, P. S. 2005. Soft sweeps: Molecular population genetics of adaptation from standing genetic variation. Genetics, 169, 2335-2352.

- INNAN, H. & KONDRASHOV, F. 2010. The evolution of gene duplications: classifying and distinguishing between models. Nature Reviews Genetics, 11, 97-108. [CrossRef]

- INWARD, D., BECCALONI, G. & EGGLETON, P. 2007. Death of an order: a comprehensive molecular phylogenetic study confirms that termites are eusocial cockroaches. Biology Letters, 3, 331-335. [CrossRef]

- JASPER, W. C., LINKSVAYER, T. A., ATALLAH, J., FRIEDMAN, D., CHIU, J. C. & JOHNSON, B. R. 2015. Large-Scale Coding Sequence Change Underlies the Evolution of Postdevelopmental Novelty in Honey Bees. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 32, 334-346. [CrossRef]

- JIANG, M., LANG, H., LI, X., ZU, Y., ZHAO, J., PENG, S., LIU, Z., ZHAN, Z. & PIAO, Z. 2022. Progress on plant orphan genes. Yichuan, 44, 682-694. [CrossRef]

- JOHNSON, B. R. 2018. Taxonomically Restricted Genes Are Fundamental to Biology and Evolution. Frontiers in Genetics, 9. [CrossRef]

- JOHNSON, B. R. & TSUTSUI, N. D. 2011a. Taxonomically restricted genes are associated with the evolution of sociality in the honey bee. BMC Genomics, 12, 164. [CrossRef]

- KAESSMANN, H. 2010. Origins, evolution, and phenotypic impact of new genes. Genome Research, 20, 1313-1326. [CrossRef]

- KANEHISA, M., SATO, Y., KAWASHIMA, M., FURUMICHI, M. & TANABE, M. 2016. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Research, 44, D457-D462. [CrossRef]

- KHALTURIN, K., ANTON-ERXLEBEN, F., SASSMANN, S., WITTLIEB, J., HEMMRICH, G. & BOSCH, T. C. G. 2008. A Novel Gene Family Controls Species-Specific Morphological Traits in Hydra. Plos Biology, 6, 2436-2449. [CrossRef]

- KHALTURIN, K., HEMMRICH, G., FRAUNE, S., AUGUSTIN, R. & BOSCH, T. C. G. 2009. More than just orphans: are taxonomically-restricted genes important in evolution? Trends in Genetics, 25, 404-413.

- KOCHVA, E., NAKAR, O. & OVADIA, M. 1983. VENOM TOXINS - PLAUSIBLE EVOLUTION FROM DIGESTIVE ENZYMES. American Zoologist, 23, 427-430. [CrossRef]

- KOCOT, K. M., AGUILERA, F., MCDOUGALL, C., JACKSON, D. J. & DEGNAN, B. M. 2016. Sea shell diversity and rapidly evolving secretomes: insights into the evolution of biomineralization. Frontiers in Zoology, 13. [CrossRef]

- KRUMLAUF, R. 1994. HOX GENES IN VERTEBRATE DEVELOPMENT. Cell, 78, 191-201. [CrossRef]

- LASKOWSKI, R. A., WATSON, J. D. & THORNTON, J. M. 2005. ProFunc: a server for predicting protein function from 3D structure. Nucleic Acids Research, 33, W89-W93. [CrossRef]

- LEE, D., REDFERN, O. & ORENGO, C. 2007. Predicting protein function from sequence and structure. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 8, 995-1005. [CrossRef]

- LETUNIC, I. & BORK, P. 2016. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Research, 44, W242-W245. [CrossRef]

- LO, N., TOKUDA, G., WATANABE, H., ROSE, H., SLAYTOR, M., MAEKAWA, K., BANDI, C. & NODA, H. 2000. Evidence from multiple gene sequences indicates that termites evolved from wood-feeding cockroaches. Current Biology, 10, 801-804. [CrossRef]

- MAO, X. Z., CAI, T., OLYARCHUK, J. G. & WEI, L. P. 2005. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics, 21, 3787-3793. [CrossRef]

- MCLYSAGHT, A. & GUERZONI, D. 2015. New genes from non-coding sequence: the role of de novo protein-coding genes in eukaryotic evolutionary innovation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 370. [CrossRef]

- MILDE, S., HEMMRICH, G., ANTON-ERXLEBEN, F., KHALTURIN, K., WITTLIEB, J. & BOSCH, T. C. G. 2009. Characterization of taxonomically restricted genes in a phylum-restricted cell type. Genome Biology, 10. [CrossRef]

- MOYERS, B. A. & ZHANG, J. Z. 2015. Phylostratigraphic Bias Creates Spurious Patterns of Genome Evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 32, 258-267. [CrossRef]

- MOYERS, B. A. & ZHANG, J. Z. 2016. Evaluating Phylostratigraphic Evidence for Widespread De Novo Gene Birth in Genome Evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 33, 1245-1256. [CrossRef]

- NEI, M. & ROONEY, A. P. 2005. Concerted and birth-and-death evolution of multigene families. Annual Review of Genetics, 39, 121-152. [CrossRef]

- NICHOLS, R. 2001. Gene trees and species trees are not the same. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16, 358-364. [CrossRef]

- O’LEARY, N. A., WRIGHT, M. W., BRISTER, J. R., CIUFO, S., MCVEIGH, D. H. R., RAJPUT, B., ROBBERTSE, B., SMITH-WHITE, B., AKO-ADJEI, D., ASTASHYN, A., BADRETDIN, A., BAO, Y. M., BLINKOVA, O., BROVER, V., CHETVERNIN, V., CHOI, J., COX, E., ERMOLAEVA, O., FARRELL, C. M., GOLDFARB, T., GUPTA, T., HAFT, D., HATCHER, E., HLAVINA, W., JOARDAR, V. S., KODALI, V. K., LI, W. J., MAGLOTT, D., MASTERSON, P., MCGARVEY, K. M., MURPHY, M. R., O’NEILL, K., PUJAR, S., RANGWALA, S. H., RAUSCH, D., RIDDICK, L. D., SCHOCH, C., SHKEDA, A., STORZ, S. S., SUN, H. Z., THIBAUD-NISSEN, F., TOLSTOY, I., TULLY, R. E., VATSAN, A. R., WALLIN, C., WEBB, D., WU, W., LANDRUM, M. J., KIMCHI, A., TATUSOVA, T., DICUCCIO, M., KITTS, P., MURPHY, T. D. & PRUITT, K. D. 2016. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Research, 44, D733-D745. [CrossRef]

- PAULING, L. & COREY, R. B. 1951. The structure of proteins: two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 37, 205-211. [CrossRef]

- PEIXOTO, L. G., CALABRIA, L. K., GARCIA, L., CAPPARELLI, F. E., GOULART, L. R., DE SOUSA, M. V. & ESPINDOLA, F. S. 2009. Identification of major royal jelly proteins in the brain of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Journal of Insect Physiology, 55, 671-677. [CrossRef]

- ROKAS, A. 2008. The Origins of Multicellularity and the Early History of the Genetic Toolkit For Animal Development. Annual Review of Genetics, 42, 235-251. [CrossRef]

- ROSENBERG, N. A. 2002. The probability of topological concordance of gene trees and species trees. Theoretical Population Biology, 61, 225-247. [CrossRef]

- ROSKAMP, K. W., PAULSON, C. N., BRUBAKER, W. D. & MARTIN, R. W. 2020. Function and Aggregation in Structural Eye Lens Crystallins. Accounts of Chemical Research, 53, 863-874. [CrossRef]

- SACKTON, T. B., WERREN, J. H. & CLARK, A. G. 2013. Characterizing the Infection-Induced Transcriptome of <i>Nasonia vitripennis</i> Reveals a Preponderance of Taxonomically-Restricted Immune Genes. Plos One, 8.

- SEEMANN, T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics, 30, 2068-2069. [CrossRef]

- SHERMAN, P. W. 1988. THE LEVELS OF ANALYSIS. Animal Behaviour, 36, 616-619.

- SHERMAN, P. W. 1989. THE CLITORIS DEBATE AND THE LEVELS OF ANALYSIS. Animal Behaviour, 37, 697-698. [CrossRef]

- SIVASHANKARI, S. & SHANMUGHAVEL, P. 2006. Functional annotation of hypothetical proteins - A review. Bioinformation, 1, 335-338. [CrossRef]

- SLINGSBY, C., WISTOW, G. J. & CLARK, A. R. 2013. Evolution of crystallins for a role in the vertebrate eye lens. Protein Science, 22, 367-+. [CrossRef]

- SUMNER, S. 2014. The importance of genomic novelty in social evolution. Molecular Ecology, 23, 26-28. [CrossRef]

- SUMNER, S., FAVREAU, E., GEIST, K., TOTH, A. L. & REHAN, S. M. 2023. Molecular patterns and processes in evolving sociality: lessons from insects. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 378. [CrossRef]

- SUNAGAWA, S., DESALVO, M. K., VOOLSTRA, C. R., REYES-BERMUDEZ, A. & MEDINA, M. 2009. Identification and Gene Expression Analysis of a Taxonomically Restricted Cysteine-Rich Protein Family in Reef-Building Corals. Plos One, 4. [CrossRef]

- SYMONS, D. 1979. The Evolution of Human Sexuality, New York, Oxford University Press.

- TATUSOVA, T., DICUCCIO, M., BADRETDIN, A., CHETVERNIN, V., NAWROCKI, E. P., ZASLAVSKY, L., LOMSADZE, A., PRUITT, K., BORODOVSKY, M. & OSTELL, J. 2016.

- NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Research, 44, 6614-6624.

- TAUTZ, D. & DOMAZET-LOSO, T. 2011. The evolutionary origin of orphan genes. Nature Reviews Genetics, 12, 692-702. [CrossRef]

- THORNE, B. L. & CARPENTER, J. M. 1992. PHYLOGENY OF THE DICTYOPTERA. Systematic Entomology, 17, 253-268. [CrossRef]

- TINBERGEN, N. 1963. On aims and methods of ethology. Z. Tierpsychol., 20, 410-433. [CrossRef]

- TOLL-RIERA, M., BOSCH, N., BELLORA, N., CASTELO, R., ARMENGOL, L., ESTIVILL, X. & MAR ALBA, M. 2009a. Origin of Primate Orphan Genes: A Comparative Genomics Approach. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 26, 603-612. [CrossRef]

- TOLL-RIERA, M., CASTELO, R., BELLORA, N. & ALBA, M. M. 2009b. Evolution of primate orphan proteins. Biochemical Society Transactions, 37, 778-782. [CrossRef]

- VAKIRLIS, N., ACAR, O., HSU, B., COELHO, N. C., VAN OSS, S. B., WACHOLDER, A., MEDETGUL-ERNAR, K., BOWMAN, R. W., HINES, C. P., IANNOTTA, J., PARIKH, S. B., MCLYSAGHT, A., CAMACHO, C. J., O’DONNELL, A. F., IDEKER, T. & CARVUNIS, A. R. 2020a. De novo emergence of adaptive membrane proteins from thymine-rich genomic sequences. Nature Communications, 11. [CrossRef]

- VAKIRLIS, N., CARVUNIS, A. R. & MCLYSAGHT, A. 2020b. Synteny-based analyses indicate that sequence divergence is not the main source of orphan genes. Elife, 9. [CrossRef]

- VALDEZ-CRUZ, N. A., SEGOVIA, L., CORONA, M. & POSSANI, L. D. 2007. Sequence analysis and phylogenetic relationship of genes encoding heterodimeric phospholipases A2 from the venom of the scorpion <i>Anuroctonus phaiodactylus</i>. Gene, 396, 149-158.

- VAN DE PEER, Y., MIZRACHI, E. & MARCHAL, K. 2017. The evolutionary significance of polyploidy. Nature Reviews Genetics, 18, 411-424.

- VAN DER BURG, C. A., PRENTIS, P. J., SURM, J. M. & PAVASOVIC, A. 2016. Insights into the innate immunome of actiniarians using a comparative genomic approach. Bmc Genomics, 17. [CrossRef]

- VERSTER, A. J., STYLES, E. B., MATEO, A., DERRY, W. B., ANDREWS, B. J. & FRASER, A. G. 2017. Taxonomically Restricted Genes with Essential Functions Frequently Play Roles in Chromosome Segregation in <i>Caenorhabditis elegans</i> and <i>Saccharomyces cerevisiae</i>. G3-Genes Genomes Genetics, 7, 3337-3347.

- VOOLSTRA, C. R., SUNAGAWA, S., MATZ, M. V., BAYER, T., ARANDA, M., BUSCHIAZZO, E., DESALVO, M. K., LINDQUIST, E., SZMANT, A. M., COFFROTH, M. A. & MEDINA, M. 2011. Rapid Evolution of Coral Proteins Responsible for Interaction with the Environment. Plos One, 6. [CrossRef]

- WAGNER, G. P. & LYNCH, V. J. 2008. The gene regulatory logic of transcription factor evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23, 377-385. [CrossRef]

- WAGNER, G. P., PAVLICEV, M. & CHEVERUD, J. M. 2007. The road to modularity. Nature Reviews Genetics, 8, 921-931.

- WATSON, J. D. & CRICK, F. H. C. 1953. MOLECULAR STRUCTURE OF NUCLEIC ACIDS - A STRUCTURE FOR DEOXYRIBOSE NUCLEIC ACID. Nature, 171, 737-738. [CrossRef]

- WEISMAN, C. 2021. Novelty or Nuisance? Where Lineage-Specific Genes Come from and Why It Matters. Dissertation/Thesis.

- WEISMAN, C., MURRAY, A. W. & EDDY, S. R. 2020a. Many, but not all, lineage-specific genes can be explained by homology detection failure. Plos Biology, 18, e3000862. [CrossRef]

- WEISMAN, C. M., MURRAY, A. W. & EDDY, S. R. 2020b. Many, but not all, lineage-specific genes can be explained by homology detection failure. Plos Biology, 18. [CrossRef]

- WHITELAW, B. L., COOKE, I. R., FINN, J., DA FONSECA, R. R., RITSCHARD, E. A., GILBERT, M. T. P., SIMAKOV, O. & STRUGNELL, J. M. 2020. Adaptive venom evolution and toxicity in octopods is driven by extensive novel gene formation, expansion, and loss. Gigascience, 9. [CrossRef]

- WILSON, G. A., BERTRAND, N., PATEL, Y., HUGHES, J. B., FEIL, E. J. & FIELD, D. 2005. Orphans as taxonomically restricted and ecologically important genes. Microbiology-Sgm, 151, 2499-2501. [CrossRef]

- WILSON, G. A., FEIL, E. J., LILLEY, A. K. & FIELD, D. 2007. Large-Scale Comparative Genomic Ranking of Taxonomically Restricted Genes (TRGs) in Bacterial and Archaeal Genomes. Plos One, 2. [CrossRef]

- WISSLER, L., GADAU, J., SIMOLA, D. F., HELMKAMPF, M. & BORNBERG-BAUER, E. 2013. Mechanisms and Dynamics of Orphan Gene Emergence in Insect Genomes. Genome Biology and Evolution, 5, 439-455. [CrossRef]

- WISTOW, G. 1993. LENS CRYSTALLINS - GENE RECRUITMENT AND EVOLUTIONARY DYNAMISM. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 18, 301-306. [CrossRef]

- WITTKOPP, P. J., VACCARO, K. & CARROLL, S. B. 2002. Evolution of yellow gene regulation and pigmentation in Drosophila. Current Biology, 12, 1547-1556. [CrossRef]

- YANG, J. Y., ANISHCHENKO, I., PARK, H., PENG, Z. L., OVCHINNIKOV, S. & BAKER, D. 2020. Improved protein structure prediction using predicted interresidue orientations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117, 1496-1503. [CrossRef]

- YANG, L. D., ZOU, M., FU, B. D. & HE, S. P. 2013. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of lineage-specific genes within zebrafish. Bmc Genomics, 14, 15. [CrossRef]

- ZEESHAN FAKHAR, A., LIU, J., PAJEROWSKA-MUKHTAR, K. & MUKHTAR, S. M. 2023. The Lost and Found: Unraveling the Functions of Orphan Genes. Journal of Developmental Biology, 11, 27.

- ZHANG, J. Z. 2003. Evolution by gene duplication: an update. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 18, 292-298. [CrossRef]

- ZHAO, C. Y., ESCALANTE, L. N., CHEN, H., BENATTI, T. R., QU, J. X., CHELLAPILLA, S., WATERHOUSE, R. M., WHEELER, D., ANDERSSON, M. N., BAO, R. Y., BATTERTON, M., BEHURA, S. K., BLANKENBURG, K. P., CARAGEA, D., CAROLAN, J. C., COYLE, M., EL-BOUHSSINI, M., FRANCISCO, L., FRIEDRICH, M., GILL, N., GRACE, T., GRIMMELIKHUIJZEN, C. J. P., HAN, Y., HAUSER, F., HERNDON, N., HOLDER, M., IOANNIDIS, P., JACKSON, L., JAVAID, M., JHANGIANI, S. N., JOHNSON, A. J., KALRA, D., KORCHINA, V., KOVAR, C. L., LARA, F., LEE, S. L., LIU, X. M., LOFSTEDT, C., MATA, R., MATHEW, T., MUZNY, D. M., NAGAR, S., NAZARETH, L. V., OKWUONU, G., ONGERI, F., PERALES, L., PETERSON, B. F., PU, L. L., ROBERTSON, H. M., SCHEMERHORN, B. J., SCHERER, S. E., SHREVE, J. T., SIMMONS, D., SUBRAMANYAM, S., THORNTON, R. L., XUE, K., WEISSENBERGER, G. M., WILLIAMS, C. E., WORLEY, K. C., ZHU, D. H., ZHU, Y. M., HARRIS, M. O., SHUKLE, R. H., WERREN, J. H., ZDOBNOV, E. M., CHEN, M. S., BROWN, S. J., STUART, J. J. & RICHARDS, S. 2015. A Massive Expansion of Effector Genes Underlies Gall-Formation in the Wheat Pest Mayetiola destructor. Current Biology, 25, 613-620. [CrossRef]

- ZIELEZINSKI, A., DOBRYCHLOP, W. & KARLOWSKI, W. M. 2023. TRGdb: a universal resource for the exploration of taxonomically restricted genes in bacteria. Database-the Journal of Biological Databases and Curation, 2023. [CrossRef]

- ZILE, K., DESSIMOZ, C., WURM, Y. & MASEL, J. 2020. Only a Single Taxonomically Restricted Gene Family in the <i>Drosophila melanogaster</i> Subgroup Can Be Identified with High Confidence. Genome Biology and Evolution, 12, 1355-1366.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).