1. Introduction

Studies have shown that the distribution of species in natural ecosystems is not random. These studies indicate that topographic, climatic, and edaphic factors significantly influence species distributions [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Additionally, factors such as predator-prey relationships and the presence of migratory pathways can also dramatically affect species distributions. These factors often vary by region and over time, making spatial and seasonal changes in species distributions inevitable.

Understanding the interactions between biotic and abiotic factors at both the individual and species richness levels requires the evaluation of complex interrelationships. Considering Earth's ecological, historical, and evolutionary processes, the intricate interactions between species and their environment can be seen as an expected outcome [

8]. This is particularly evident as changing climatic conditions force species to adapt to their environments, resulting in spatial and temporal variations in species distributions. For instance, climate change is altering bird species' behaviors, genetics, phenology (such as breeding and migration timing), abundances, and distributions. As climate conditions shift, many species can relocate to higher altitudes and latitudes. These impacts present significant challenges for the conservation of Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs). Some species identified as critical in an IBA may no longer survive in the area if conditions become unsuitable, while others may colonize these habitats. Consequently, IBAs have the potential to remain pivotal in conserving birds and other biodiversity under climate change. However, achieving this will require a much more dynamic approach to site management objectives [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Therefore, studies conducted in areas with diverse topographic and climatic characteristics are considered essential and of increasing importance.

Türkiye is a country rich in geographical diversity, encompassing three distinct phytogeographical regions: the Mediterranean, Euro-Siberian, and Irano-Turanian zones. Within these regions, topography varies on both macro and micro scales. This topographic variability, combined with the influence of the seas surrounding Türkiye on three sides, results in a highly heterogeneous climatic distribution along its coastal zones. This environmental heterogeneity is considered the primary reason for the spatial and temporal variations in Türkiye's bird species richness [

13,

14].

The scientific literature on birds is extensive. On average, 1,217 papers were published on bird conservation every year during 2010-2021, compared to 892, 609 and 341 for mammal, insect and amphibian conservation respectively. A “Web of Science” keyword search reveals that during 2010–2020, over 75,000 articles were published in academic journals with the word “bird” in the title or abstract—an increase of more than 70% since the previous decade [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Among these studies, those that determine the habitat preferences of bird species and relate them to climatic factors are of great importance. The findings from such research play a key role in developing ecological-based planning aimed at ensuring the sustainability of bird species [

22,

23,

24].

A recent review of the scientific literature largely limited to Europe and North America shows that 24% of the 570 bird species studied globally have already been negatively affected by climate change to date, while only 13% have responded positively. For half of those studied, the impact remains uncertain [

25,

26].

Birds are ubiquitous, being found in every country in the world, and nearly every habitat. Ranging from hummingbirds to ostriches, from penguins to eagles, birds exhibit astounding diversity. Some species have evolved to survive in extreme climates, from the coldest polar regions to the hottest deserts, while others exploit their ability to fly long distances to migrate between climatically suitable areas in different seasons. Birds are often highly sensitive to changes in their environment, and can therefore act as early warning systems of threats to nature. For example, many bird species are already responding to climate change by shifting their distribution or the timing of key events such as migration [

21,

27].

Bird migration occurs as an instinctive response to survival and the search for new habitats when the topographic and climatic factors in their living areas are altered, either naturally or artificially. During migration, birds often follow the same routes every year. However, there is still no definitive evidence explaining how they navigate these routes. Although various theories exist, none have been conclusively proven to date. Bird migrations can occur in large flocks forming massive groups, in smaller groups, or even individually [

28]. Extreme conditions such as heavy snow, rain, hailstorms, extreme temperatures, and the resulting droughts are among the primary threats to birds. Snow, in particular, is one of the most significant climatic factors causing many bird species to either migrate or perish during winter. Similarly, drought is another critical climatic factor that affects migratory birds. The drying up of water sources, especially along long migration routes, leads to many birds dying or altering their migratory paths. For instance, drought along the Pacific Flyway, a key migratory route used by millions of birds annually, poses a severe threat to both breeding and migratory bird populations in the region. The reduction in water resources in their habitats forces more birds into smaller areas, increasing competition and stress. Additionally, this process is reported to contribute to the rise of infectious diseases [

29].

As evident from the information provided, environmental factors such as topography and climate, along with migratory routes, are key parameters influencing the distribution of bird species. A review of studies in this field reveals that early research primarily focused on fauna identification. However, over time, factors such as shifts in ecological paradigms, advancements in statistical approaches, and technological developments have broadened the perspective of these studies.

In Türkiye, studies on bird fauna have a history spanning approximately 100 years. In the 1920s, Turkish biologist Ali Wahby (Vehbi) collected bird records in Istanbul province. He is recognized as the first person in the Country to ring birds, starting with White Storks. His paper titled "Les oiseaux de la région de Stamboul et de ses environs", published in 1930 and 1934, is considered the first ornithological publication by a Turkish author [

30]. Around the same period, Otto Steinfatt observed the remarkable bird migrations over the Bosphorus between September and November 1931. Six years later, Lutz Mauve conducted the first comprehensive spring migration study on raptors and storks at the same observation site [

31,

32,

33].

Ornithofaunistic research in Türkiye, until the publication of Dr. Saadet Ergene’s work in 1945, was predominantly conducted by foreign individuals or groups visiting Anatolia for various purposes. Research on birds gained momentum when Prof. Curt Kosswig, appointed as the head of the Zoology Department at Istanbul University’s Faculty of Science, initiated systematic studies. Prior to this, investigations were limited to specific regions of Anatolia [

34,

35]. During this period, Kosswig, as the director of the Zoology Institute at Istanbul University, highlighted the importance of the large colonies of herons, spoonbills, and cormorants breeding in Lake Manyas, which ultimately led to its designation as a national park in 1958. He also encouraged Saadet Ergene to write an illustrated study on Turkish birds. However, most ornithological research during this period continued to be dominated by Western European visitors. Notably, Kumerloeve’s 1961 publication on Anatolian birds is regarded as a significant contribution. Through these and subsequent scientific studies conducted at Turkish universities, efforts were made to systematically document Türkiye’s ornithofauna [

35,

36,

37,

38].

In 1966, a team of British birdwatchers conducted the first complete autumn census of birds flying over the Bosphorus, which was later published [

39]. Until then, overwintering birds in the region had largely been overlooked. However, following the first visit by the International Waterfowl Research Bureau (IWRB) in 1967, led by Josef Szjj and Hayo Hoekstra, the scope of annual European and Asian midwinter waterbird counts was expanded to include Türkiye. A second IWRB mission, carried out between July and November 1968 by Jacques Viellard and colleagues, made extensive observations in eastern Türkiye and discovered breeding Velvet Scoters.

Following the 1960s, a voluntary bird conservation movement began to take root in Türkiye. Associations, exhibition galleries, birdwatching clubs, books, newsletters, and events became increasingly common. In the 1980s, a new wave of German influence emerged in Turkish ornithology, marked by Max Kasparek’s contributions. Like his predecessor Kumerloeve, Kasparek published numerous articles and books on Türkiye’s avifauna. Notably, he prepared an annotated national bird checklist, the first detailed update of Türkiye’s bird fauna since 1961. Alongside Şahika Ertan and Asaf Ertan, he also compiled Türkiye’s first inventory of Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) [

33,

40]. Subsequent studies expanded these findings, identifying 156 IBAs in Türkiye. Research revealed that at least 112 of these IBAs (72% of the total, covering 93% of the area) host populations of international significance. As further research is conducted, the number of identified IBAs is expected to increase [

41,

42].

Between 1998 and 2003, three major bird surveys were conducted across large regions of Türkiye, marking the first time that breeding bird data were collected using standardized methodologies. These surveys focused on the Konya Basin [

43], Mediterranean forests [

44], and Southeastern Anatolia [

45]. Studies after the 2000s began to emphasize the use of quantitative approaches [

15,

46]. Factors such as the increasingly dramatic impacts of climate change, the publication of climate scenarios by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), advancements in both computer technologies and machine learning methods facilitated the rapid integration of statistical and model-based approaches into studies on bird species [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. In the context of the global drive for sustainability, the integration of quantitative approaches has become increasingly critical for addressing complex biodiversity challenges. As ecosystems face mounting pressures from climate change and habitat loss, quantitative methodologies enable the identification of patterns and processes that inform sustainable conservation strategies. In Türkiye, where diverse ecological regions support rich avian biodiversity, these approaches are essential for linking spatial and temporal variations in species richness to actionable, evidence-based management practices [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

134]. Hence, in the present study, a quantitative process was employed to identify the spatial and temporal variations in bird species richness across Türkiye. The results revealed significant differences, highlighting the need to consider regional and seasonal variations in ecosystem-based planning in Türkiye.

2. Materials and Methods

Study area

Türkiye is a country that straddles both Europe and Asia, lying at a key geographical intersection that has made it a place of strategic importance (

Figure 1). Located between latitudes 36°N and 42°N and longitudes 26°E and 45°E, the Country covers a vast and diverse landmass of approximately 8 million hectares [

60]. Its terrain is remarkably varied, ranging from coastal plains in the west to rugged mountains in the east. The northern regions are dominated by the Pontic Mountains, which run parallel to the Black Sea, while the Taurus Mountains line the southern coast, adjacent to the Mediterranean. In central Türkiye, the Anatolian Plateau extends across a semiarid landscape at an average elevation of 1,000 meters. To the east, the terrain becomes more mountainous, culminating in Mount Ağrı, which at 5,137 meters is the Country's highest peak [

61].

Türkiye is composed of 81 provinces across seven geographical regions (

Table 1) (compiled by authors based on Trakuş dataset). In these regions, climate reflects its geographical diversity, with significant variation from region to region. The Aegean and Mediterranean coasts enjoy a typical Mediterranean climate, characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, rainy winters [

62]. By contrast, the Black Sea coast experiences a humid subtropical climate with consistent rainfall throughout the year [

63]. Inland, the Anatolian Plateau is marked by a continental climate with hot, dry summers and cold winters that exhibit sharp temperature swings [

64]. The elevated regions in the east face harsher winters, with heavy snowfall due to their altitude [

65].

Avifauna and Migration Routes of Türkiye

Türkiye, located at the intersection of Europe, Asia, and Africa, serves as an extremely important migration route for birds due to its geographical position. Hence, it stands out as an internationally significant feeding and breeding area. Türkiye, which lies on two major migration routes, is home to 486 bird species, 416 of which are migratory, according to 2019 Trakus data. Of these, 400 species are observed in Türkiye regularly each year, and 313 species breed in the Country [

66,

67]. According to data published by Trakus in 2022, the number of bird species in Türkiye had risen to 497. Currently, 501 bird species have been recorded [

68]. The majority of bird species are listed on the IUCN Red List [

35].

Türkiye is located at the intersection of diverse climate zones and multiple phytogeographical regions (Euro-Siberian, Mediterranean, and Irano-Turanian) and lies on major bird migration routes. In the north, the Euro-Siberian region along the Black Sea is home to dense forests of deciduous and coniferous trees, such as oak, beech, and pine. The Mediterranean region, covering the southern and western coastal areas, is characterized by typical Mediterranean flora, including evergreen shrubs, olive trees, and maquis. The Irano-Turanian region, which encompasses much of central and eastern Türkiye, is dominated by steppe vegetation, featuring shrubs and grasses that have adapted to the dry, harsh conditions of the Anatolian Plateau [

69]. Due to hosting a wide variety of vegetation types across different phytogeographical regions, Türkiye possesses an exceptionally diverse avifauna within the temperate zone [

66,

70,

71].

Türkiye is also a critical corridor for bird migration, acting as a natural bridge between Europe, Asia, and Africa [

72]. Türkiye lies at the convergence of two major migratory routes: the East Africa-West Asia Flyway and the Black Sea-Mediterranean Flyway. Every year, millions of birds traverse these routes during their spring and autumn migrations, using Türkiye as a key stopover. Important migration bottlenecks such as the Bosphorus, the Dardanelles, and Iskenderun Bay serve as vital passageways for large flocks of storks, raptors, and other migratory birds. This makes Türkiye not only a hotspot for biodiversity but also an essential destination for birdwatchers and conservation efforts [

69,

73]. The Country’s diverse habitats, shaped by its varied topography and climate, provide critical breeding and resting grounds for a wide range of bird species throughout the year [

74]. These areas directly influence migration routes and timings throughout the year [

71]. In Türkiye, bird migrations occur from south to north in spring and from north to south in autumn [

75]. One of the two major migration routes passes through the Bosphorus in Istanbul province, following western and central Anatolia, and proceeds to Africa through Hatay province. The other main migration route begins in the Artvin valley, used by birds coming from Central Asia and Eastern Siberia, and continues through eastern and southeastern Anatolia before reaching Africa through Syria [

76].

Each year, more than 200,000 raptors utilize these migration routes, entering Türkiye from the Eastern Black Sea region, crossing the Çoruh River, and dispersing into the wetlands of Eastern Anatolia [

28]. This migration through Türkiye is recorded as the largest raptor migration in the Western Palearctic region. Additionally, along the route known as the "Bosphorus Migration Corridor," which starts in Thrace and passes through the Bosphorus heading southward, over 250,000 storks migrate in groups of 200 to 700. This remarkable movement, one of the most spectacular bird migrations in the world, takes place over Anatolia [

28,

77].

Data collection

Trakus is a scientific database that has documented bird species observed, photographed, or recorded in Türkiye since 2007, based on the species list recognized by the International Ornithologists’ Committee [

68]. Initially, necessary correspondence was carried out to obtain permission to use data from the TRAKUS database, which includes records of bird species observed in Türkiye, to identify species present in summer and winter. Additionally, data on bird species and habitat preferences from the eBird (KuşBank) application, in collaboration with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, were utilized. Using records from Trakus covering 501 bird species, only species present in summer and winter were identified on a provincial basis and organized into tables in MS Excel [

68,

78]. Resident species, or those nesting and remaining in the same region year-round in Türkiye, were excluded from the scope.

Mapping of bird species richness

In the present study, we determined the species richness using bird observation data collected from Türkiye’s 81 provinces during both the summer and winter seasons. Subsequently, we mapped species richness values for both seasons using ArcMap software. To enable an objective comparison between the summer and winter maps, the species richness values in the legends of both maps were grouped based on threshold values identified through the Jenks natural breaks classification method. The Jenks natural breaks classification method, widely used in cartography and geographic information systems (GIS), identifies natural thresholds in data by minimizing variance within classes and maximizing variance between classes [

79,

80]. For this analysis, we run the "getJenksBreaks" function from the “BAMMtools” package in R [

81]. Using this function, the species richness values for the summer season were first classified into five groups based on the calculated thresholds, and the map was categorized accordingly. The same threshold values were then applied to the winter species richness data, resulting in two final species richness maps for the summer and winter seasons. These maps highlighted the seasonal variations in species richness across Türkiye.

Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification

We utilized the Köppen-Geiger climate classification, one of the most widely used climate classification methods to illustrate the climatic differences between regions in this study. This system was first introduced to the scientific literature by Köppen in 1900 and later refined to its current form by the German scientist Geiger in 1961 [

132,

133] (

Table 2) (compiled by authors based on Köppen 1900, and Geiger 1961).

There are various studies that present Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps for Türkiye using different datasets [

82,

83,

84]. In this study, we used the Köppen-Geiger climate classification map produced by Taşoğlu et al. (2024), which was generated using monthly average temperature and monthly total precipitation data with a resolution of 30 arc seconds (~1 km), downloaded from the Chelsa database.

Figure 2 is compiled by authors based on [

84].

The climate type corresponding to each province was identified based on the map of Türkiye's major Köppen-Geiger climate types presented in

Figure 2.

Statistical analysis

To determine the appropriate method for assessing whether the differences across seasons, regions, and Köppen-Geiger climate classes were statistically significant, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test [

85,

86,

87] was applied. Since the analysis showed that the assumption of normality was not met, a logarithmic transformation was applied to the data. However, even after this transformation, the normality assumption was still not satisfied. Hence, we used the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test [

88] to examine the differences between groups. The Kruskal-Wallis test was first used to identify differences between seasons, followed by an analysis of the differences across regions and climate classes. To determine which groups contributed to these differences, Dunn’s test, a non-parametric post-hoc analysis often used after the Kruskal-Wallis test, was employed [

89]. The Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn tests were performed using the “ggpubr” [

90] and “dunn.test” [

91] packages in R, respectively. Then, the "Nonparametric Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Factorial Experiments" method was employed using the “nparLD” package in R [

92] to reveal whether there were significant differences both between regions and climate classes according to seasons. This approach focuses on non-parametric methods for the analysis of repeated measures, longitudinal data, and factorial experiments, with the key advantage of performing statistical analysis without relying on traditional parametric assumptions such as normal distribution and homogeneity of variance [

93]. Accordingly, Wald test results, a parameter of the mentioned method, were used to determine whether the species richness of regions and climate classes showed significant seasonal differences.

3. Results

Studies on the populations or population densities of bird species in Türkiye are almost nonexistent. Research conducted between 2014 and 2017 determined that 313 bird species breed regularly in the Türkiye. Additionally, three new species, whose breeding records have been monitored, were added to the list of regularly breeding species in Türkiye. However, it was found that three significant species no longer breed in Türkiye, as their breeding populations have disappeared in recent years. On the other hand, some species experiencing population declines across Europe, such as

Streptopelia turtur, Alauda arvensis, Lanius collurio, and

Emberiza hortulana, maintain healthy populations in Türkiye [

66].

In the present study, resident species (those that breed in Türkiye and remain in the same area year-round) were excluded.

Table 3 (compiled by authors based on Trakuş dataset) provides information on summer migratory bird species, which come to Türkiye to breed and spend the winter in other countries, as well as winter migratory bird species, which come to Türkiye solely to overwinter.

This study utilized data from 42 bird species across 81 provinces in Türkiye. During the summer, Apus pallidus and Clamator glandarius were the most widespread species, each observed in 44 provinces, while Şanlıurfa province recorded the highest species richness, with 17 species. In winter, Mareca penelope was the most frequently observed species, present in 42 provinces, and Istanbul province had the highest species richness during this season, with 21 species. On an annual basis, Istanbul province also recorded the highest species richness, with data for 26 species.

When seasonal data were evaluated, a total of 20 species were recorded during the summer and 22 species during the winter. The species richness across provinces for summer, winter, and the entire year is summarized in

Table 4 (compiled by authors based on species richness values).

The summer and winter species richness for each province was visualized on maps using ArcMap. Prior to mapping, natural threshold values for the summer period were determined using the Jenks natural breaks classification method to allow for an objective comparison. These thresholds were identified as 2, 4, 7, 11, and 17. The species richness values for both the summer and winter periods were visualized on the maps according to this classification (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) (compiled by authors based on species richness values of provinces).

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate the seasonal variations in bird species richness across Türkiye.

Figure 3 represents species richness during the summer season, while

Figure 4 focuses on the winter season. Noticeable differences can be observed, particularly in regions like the Southeastern Anatolia Region and the Black Sea Region, where richness levels vary significantly between seasons. These seasonal dynamics highlight the influence of climate and habitat availability on bird diversity, emphasizing the need for region-specific conservation strategies.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test was applied to assess whether the data were parametric or non-parametric. The test results indicated a rejection of the normality assumption (p < 0.05), meaning the data did not follow a normal distribution. A logarithmic transformation was then applied, and the normality test was repeated. However, as the normality assumption still could not be satisfied (p < 0.05), Kruskal-Wallis test, a non-parametric method, was chosen to determine differences between groups.

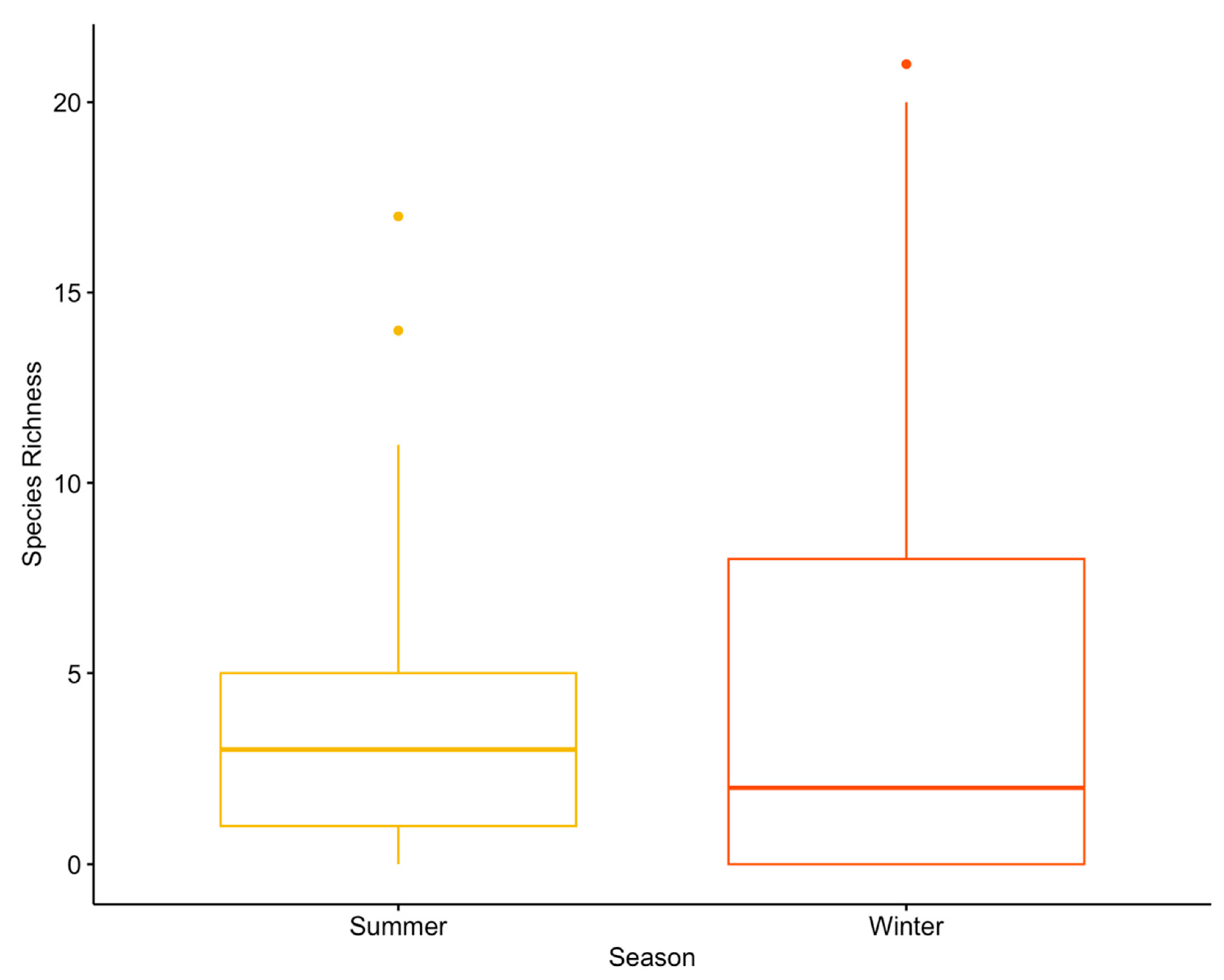

The Kruskal-Wallis test was first applied to compare species richness between the summer and winter seasons. The analysis revealed no statistically significant difference (chi-squared = 0.89989, p = 0.3428) between them (

Figure 5) (compiled by authors based on species richness values of seasons).

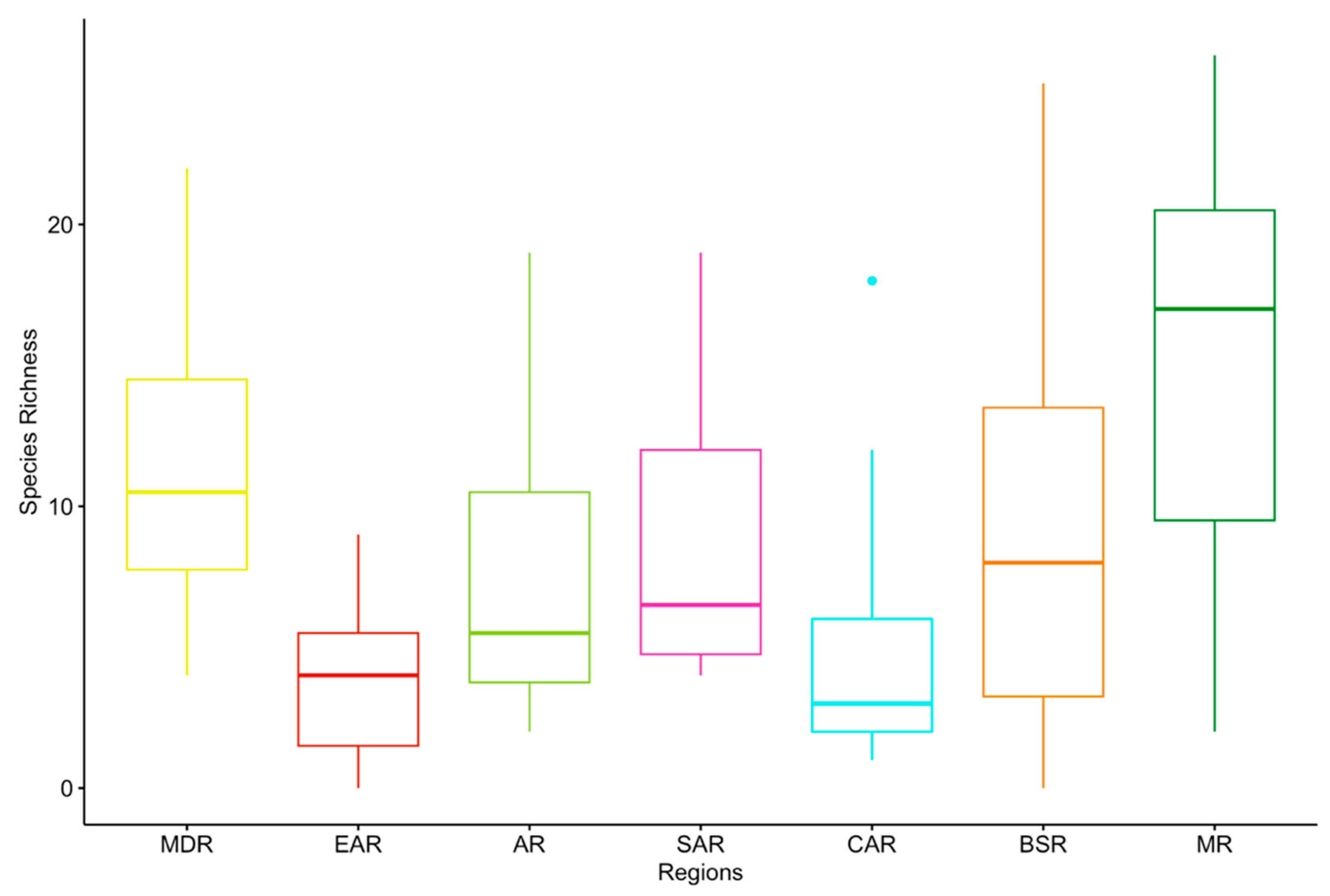

Although no statistically significant difference was found in bird species richness between seasons,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 clearly show notable differences in species richness across Türkiye’s geographical regions. When these differences were statistically evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test, a significant difference (chi-squared = 21.326, p = 0.001603) was found (

Figure 6) (compiled by authors based on species richness values of regions).

Dunn's test was conducted to determine the source of differences between regions, revealing statistically significant differences between the Mediterranean and Eastern Anatolia Regions (MDR-EAR), the Eastern Anatolia and Marmara Regions (EAR-MR), and the Central Anatolia and Marmara Regions (CAR-MR) (

Table 5) (compiled by authors based on species richness values of seasons and regions).

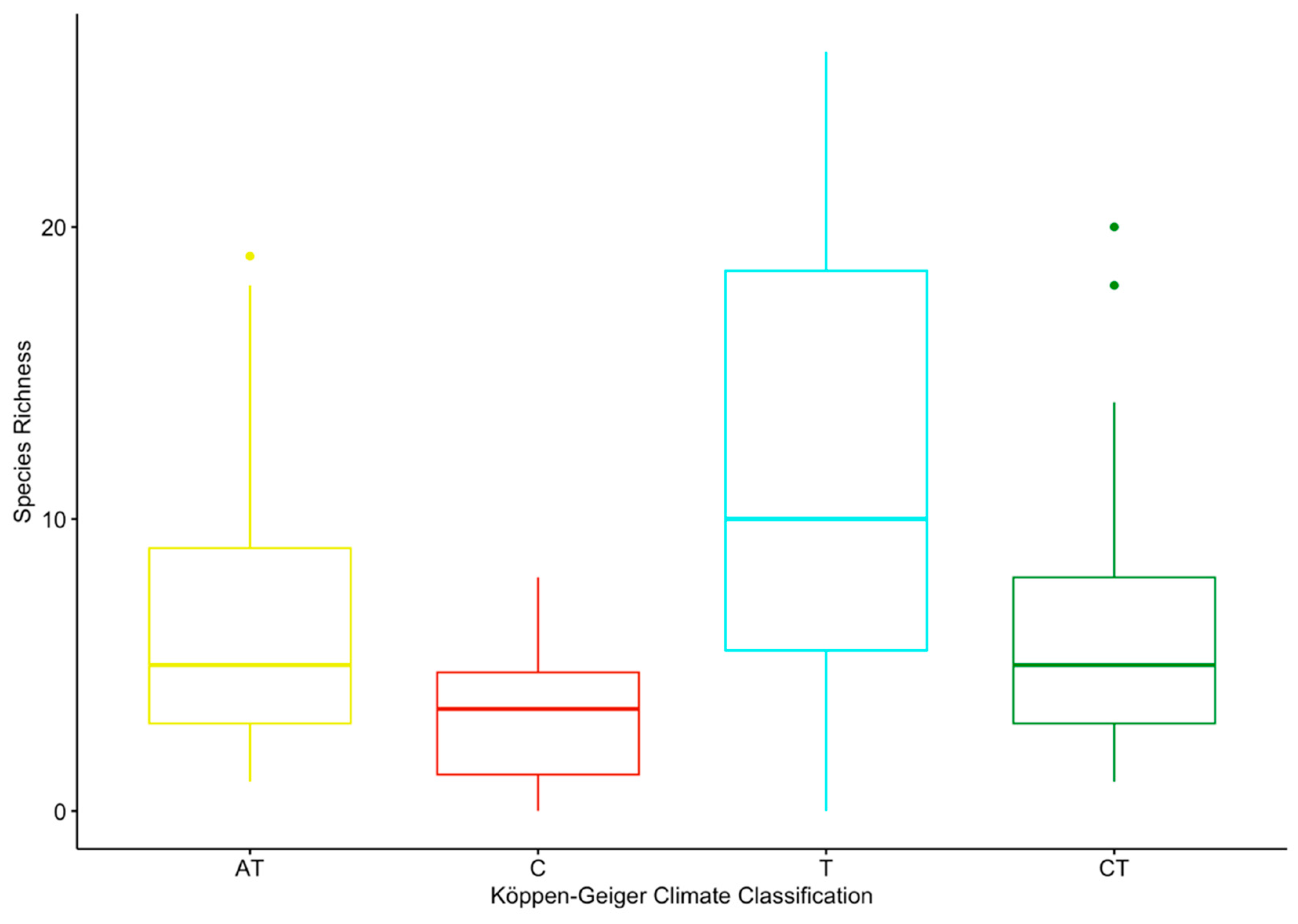

The Kruskal-Wallis test for bird species richness of Köppen-Geiger climate classes also revealed significant differences (chi-squared = 18.31, p = 0.0004) (

Figure 7) (compiled by authors based on species richness values of climate classes).

The results of Dunn's test for climate classifications showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) only between the Cold (C) and Temperate (T) climate classes (

Table 6) (compiled by authors based on species richness values of climate classes).

Finally, to determine whether the regions and climate classifications showed seasonal differences, the Nonparametric Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Factorial Experiments was applied. The Wald test results from this analysis (

Table 7) revealed significant seasonal differences for both regions and climate classifications (compiled by authors based on seasonal and regional species richness values) (p < 0.05).

The Wald statistic results in

Table 7 indicated significant seasonal differences (p < 0.05) for both regions and climate classifications.

4. Discussion

This study thoroughly examined the seasonal variations in bird species richness across Türkiye’s geographical regions and their relationships with Köppen-Geiger climate classes and environmental factors. The findings revealed that, while there were no significant overall differences in species richness between summer and winter seasons, notable differences were observed between regions and climate classifications. These results are consistent with findings from similar studies. For instance, a study by Parish et al. (1994) supports this conclusion, as they found seasonal differences in bird species richness in their research conducted in two different areas of Eastern England [

94]. Another study with similar findings was conducted by Hurlbert and Haskell (2003), where the results identified seasonal variations in bird species richness in relation to the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) [

95]. Okçu (1999) also reported that NDVI varies across regions and seasons in Türkiye [

96]. The results of these studies align with the seasonal patterns we observed in both regions and climate classifications in our research.

On the other hand, significant topographical and climatic variations exist among regions, where climatic differences largely stem from topographical diversity, or more specifically, topographical heterogeneity. Elevation and latitudinal gradients emerge as the primary topographical parameters influencing species distribution. Numerous studies highlight the potential effects of elevation differences on bird species richness [

8]. In understanding patterns of species richness, the species-area relationship and the latitudinal gradient have been well-documented and widely debated, as explored in foundational works by Brown and Gibson (1983), Brown (1988), and Begon et al. (1990) [

3,

5,

7]. While the latitudinal species-richness gradient is now thought to be reasonably well understood [

97,

98], species richness along elevational gradients remains less explored. Nevertheless, many researchers propose that an inverse relationship between species richness and elevation could be as widespread as the latitudinal gradient [

5,

7,

99,

100,

101,

102]. This perspective largely arises from repeated citation of selected studies on tropical avifauna, particularly Terborgh’s (1977) research in the Peruvian Andes, which initially appeared to show a monotonic decline in species richness with increased elevation [

103]. However, Terborgh himself noted that, with standardized sampling efforts, the species richness curve displayed a hump-shaped rather than monotonic pattern, suggesting a more nuanced relationship between elevation and species richness.

The results of our study can be indirectly related to various other parameters. One of the most important of these parameters is bird migration routes. Türkiye is located at the crossroads of two major migration routes, the East Africa-West Asia flyway and the Black Sea-Mediterranean flyway, making it a vital passage and stopover site for millions of birds [

33,

104]. These migration routes are particularly critical for bird movements during the spring and autumn months [

105]. Narrow straits such as the Bosphorus, the Dardanelles, and the Gulf of Iskenderun create a natural "bottleneck" effect for migratory birds, causing large flocks to congregate at specific points [

106]. These types of narrow passageways allow birds to conserve energy over long distances, contributing to the concentration of species richness in these areas [

72,

107]. The high bird diversity observed throughout the year in provinces along these straits, such as Istanbul, is a reflection of this phenomenon [

108].

Habitat diversity is another critical factor that supports bird species richness [

109,

110]. Türkiye spans a vast geography with diverse ecosystem types, and this diversity facilitates access to various habitats for birds [

111,

112]. The presence of different habitat types, such as forests, agricultural areas, open spaces, wetlands, and mountainous regions, plays an essential role in meeting the shelter, feeding, and breeding needs of bird species [

113,

114,

115,

116,

117]. For instance, the coexistence of both forested areas and agricultural lands in the Marmara region can be seen as a factor enhancing species diversity [

118,

119]. Similarly, the maquis shrublands and coastal forests in the Mediterranean and Aegean regions serve as key stopover sites where migratory birds rest and replenish their energy [

33,

120].

The presence of wetlands is also of great importance for bird species richness [

121,

122,

123]. Lakes, rivers, deltas, and marshes located in various regions of Türkiye provide essential feeding, resting, and energy-storing opportunities for migratory birds [

124]. For example, significant wetlands such as Lake Manyas [

125], Lake Tuz [

126], the Göksu Delta [

127], and Sultan Marshes [

128] are frequently visited by birds during migration. These wetlands play a critical ecological role in ensuring the continuity of migration routes and enhancing the survival chances of bird species. The study’s findings support the observation that regions with such wetlands exhibit higher bird species richness.

Coastal provinces near the sea are another significant factor for bird species richness. The Mediterranean, Aegean, and Black Sea coastlines provide key landing and departure points, particularly for birds migrating over the sea. In these coastal regions, the influence of moisture from the sea and the higher plant diversity creates rich habitats for birds. The forests and humid climate along the Black Sea coast offer ideal environments for meeting the shelter and feeding needs of birds during migration. This is one of the primary reasons for the high species richness observed in the Black Sea region [

129,

130]. Hence, to sustain the ecological integrity of coastal habitats, which are vital for migratory birds, it is crucial to adopt conservation strategies that address both current and future challenges posed by climate change and human activities. The rich biodiversity along the Mediterranean, Aegean, and Black Sea coastlines is not only shaped by plant diversity and climatic conditions but also relies heavily on the preservation of interconnected habitats like wetlands and coastal forests. Integrating these habitats into sustainable land-use planning will ensure their resilience while safeguarding critical migratory pathways. This approach becomes particularly important in regions like the Black Sea, where climatic factors and habitat diversity converge to support high avian richness.

The impact of climate classes on bird species distribution is also among the key findings of this study. The differences between temperate (T) and cold (C) climate regions highlight the crucial role of climatic factors in shaping bird diversity [

131]. Temperate climates provide more favorable temperatures and abundant food resources, supporting greater species diversity, whereas colder climates may limit this diversity. This underscores the importance of anticipating the potential impacts of climate change and adapting conservation strategies to suit varying climate conditions.

This study emphasizes the need for strategic measures to conserve and sustainably manage bird species in Türkiye. Expanding existing protected areas and establishing new protection statuses are crucial for safeguarding bird migration routes. In particular, the conservation of critical habitats, such as wetlands, straits, and coastal zones—essential during migration—can be achieved by restricting development and agricultural activities in these areas. Forestry policies should be designed to prevent the degradation of natural forest structures, and suitable habitats should be created for bird species with forest rehabilitations. In other words, sustainable forestry practices and approaches that focus on preserving natural vegetation must be adopted.

Agricultural and forestry activities should be planned in a way that maintains ecological balance to ensure the sustainability of habitats. Promoting agroecological methods in agricultural areas will not only increase productivity but also support biodiversity. Similarly, adopting principles of sustainable forest management will help make forest ecosystems more resilient to climate change. Future adaptation strategies must be developed with the effects of climate change in mind. These strategies should include flexible, locally tailored measures to protect bird species that are sensitive to climate change.

Finally, more integrated approaches to biodiversity conservation should be adopted, and ecosystem-based management practices must be developed. For instance, creating ecological corridors to strengthen connections between protected areas can enable birds to move safely between habitats. These recommendations provide a scientific foundation for informed and effective decisions aimed at conserving Türkiye's bird diversity and ecosystem health.