Submitted:

07 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

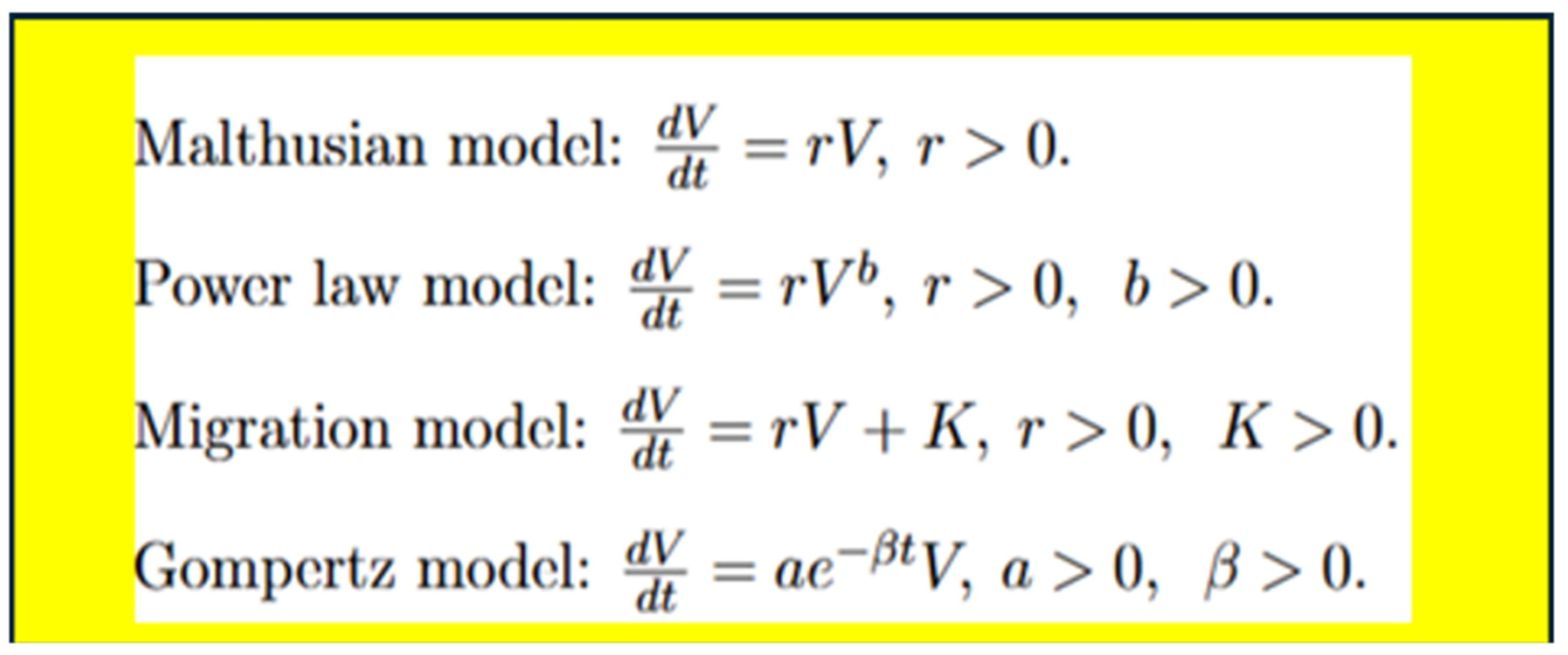

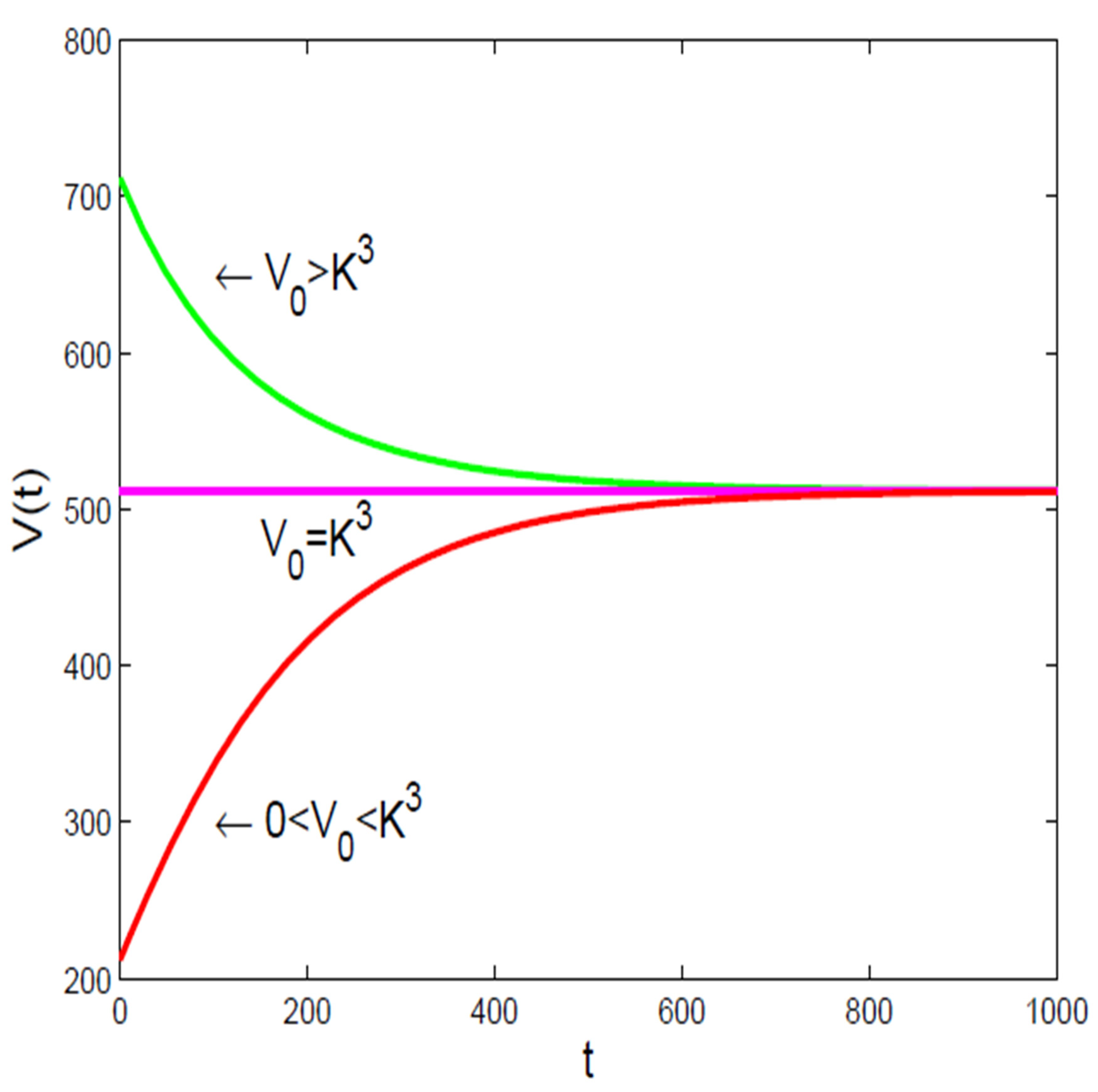

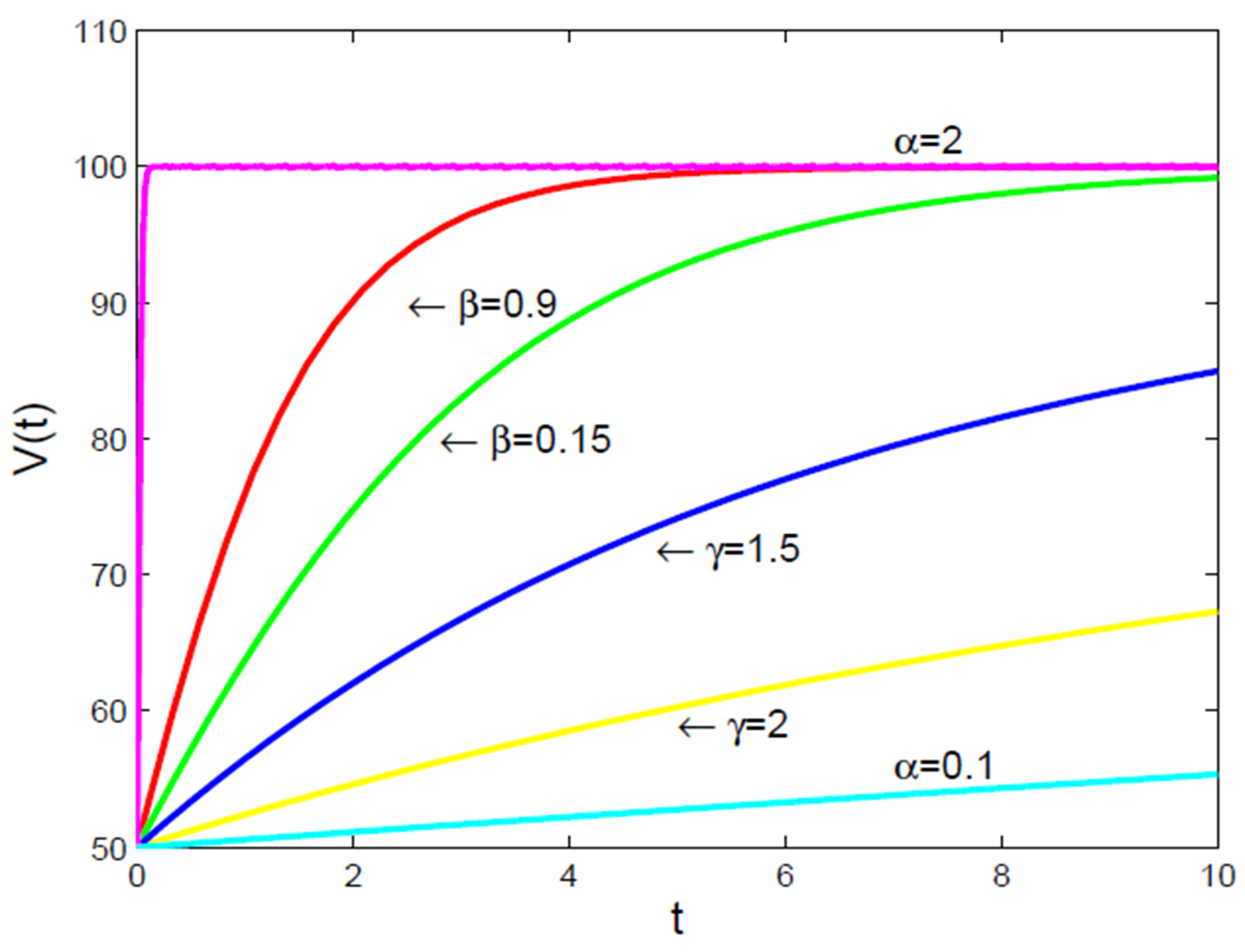

Mathematics is essential in cancer research and treatment because it helps scientists analyze complex data, such as genetic mutations in tumors, to understand cancer progression and estimate how long it has been developing. Mathematical models are used to improve treatment strategies, like determining the best combination of drugs to combat resistant cancer cells and optimizing immunotherapy approaches, such as CAR-T cell therapy. By applying these mathematical concepts, researchers can enhance the effectiveness of cancer treatments and tailor them to individual patients’ needs. Mathematical models, such as differential equations, are essential tools in cancer research for understanding and predicting how tumors grow over time. Models like the Gompertz and logistic growth models describe the dynamics of tumor growth, helping researchers simulate how cancer cells multiply, interact, and respond to various treatments. By using these models, scientists can gain insights into cancer progression and improve treatment strategies, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes. Dosimetry is a crucial aspect of radiation therapy that uses mathematical calculations to determine the right amount of radiation needed to effectively target tumors while protecting healthy tissues from damage. Advanced treatment planning software employs algorithms and simulations to figure out the best angles and intensities for delivering radiation, ensuring that the treatment is both effective and safe for the patient. This mathematical approach helps optimize cancer treatment by maximizing tumor destruction and minimizing side effects. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are important concepts in understanding how drugs work in the body. Pharmacokinetics focuses on how a drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and eliminated, which helps determine the best dosage and timing for chemotherapy. On the other hand, response models use statistical methods to predict how tumors will react to specific chemotherapy drugs, allowing doctors to create personalized treatment plans that are more effective for individual patients. Mathematics plays a crucial role in designing clinical trials for cancer treatments by helping researchers determine how many patients to include (sample size), how to randomly assign them to different treatment groups (randomization methods), and how to analyze the results statistically to see if the treatments are effective. Additionally, survival analysis techniques, like Kaplan-Meier estimation and Cox proportional hazards modeling, are used to study patient survival data, allowing researchers to identify which factors influence how long patients live after treatment. These mathematical tools are essential for ensuring that clinical trials are well-structured and that the findings are reliable. Bioinformatics is a field that uses mathematical and statistical techniques to analyze genomic data, which includes information about a person’s DNA. In cancer research, bioinformatics helps identify genetic mutations and biological pathways that contribute to the disease, allowing scientists to understand how cancer develops and progresses. This information is crucial for developing targeted therapies, which are treatments designed to specifically attack the mutations found in cancer cells, improving treatment effectiveness. The current exposition offers new insights into the cancer research community, as well as providing open problems which offer bridging the gaps to gain more knowledge about the influential role of mathematics to advance next generation cancer treatment.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Offering a plethora of mathathematical applications to advance cancer treatment.

- The provision of several emerging open problem to enrich the existing knowledge within the research community to a next generation cancer treatment.

2. The Influential Mathematics to Revolutionize Oncology

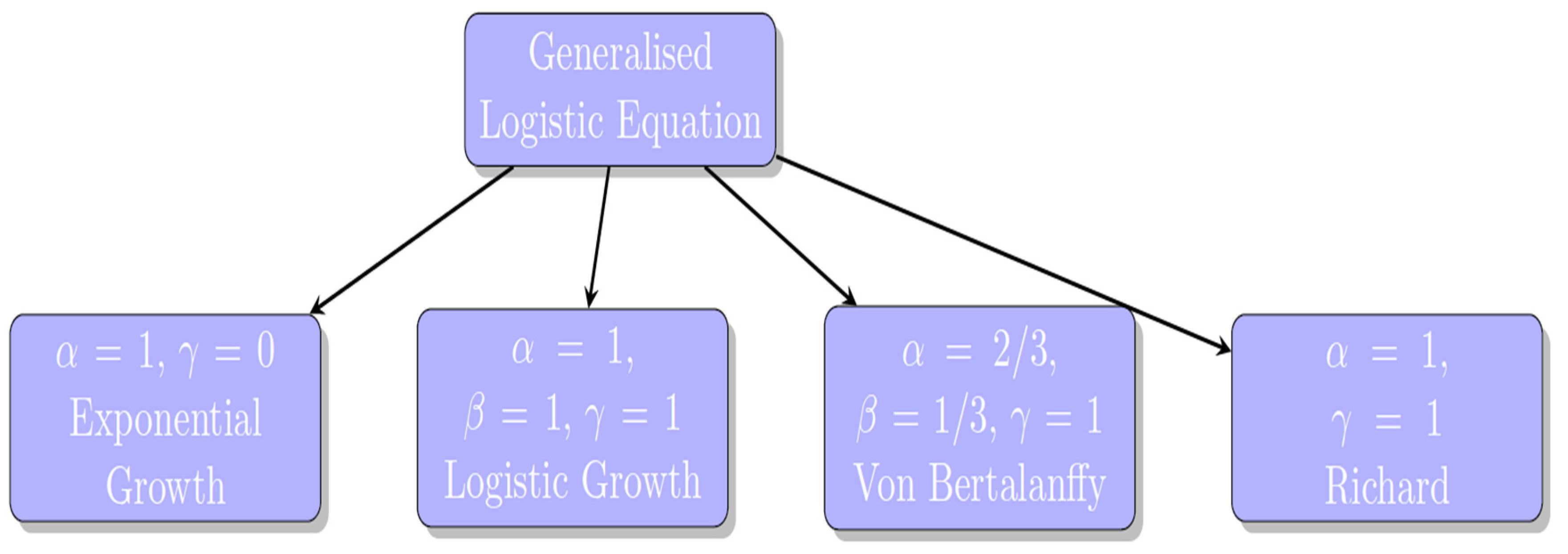

2.1. Modeling Tumor Growth

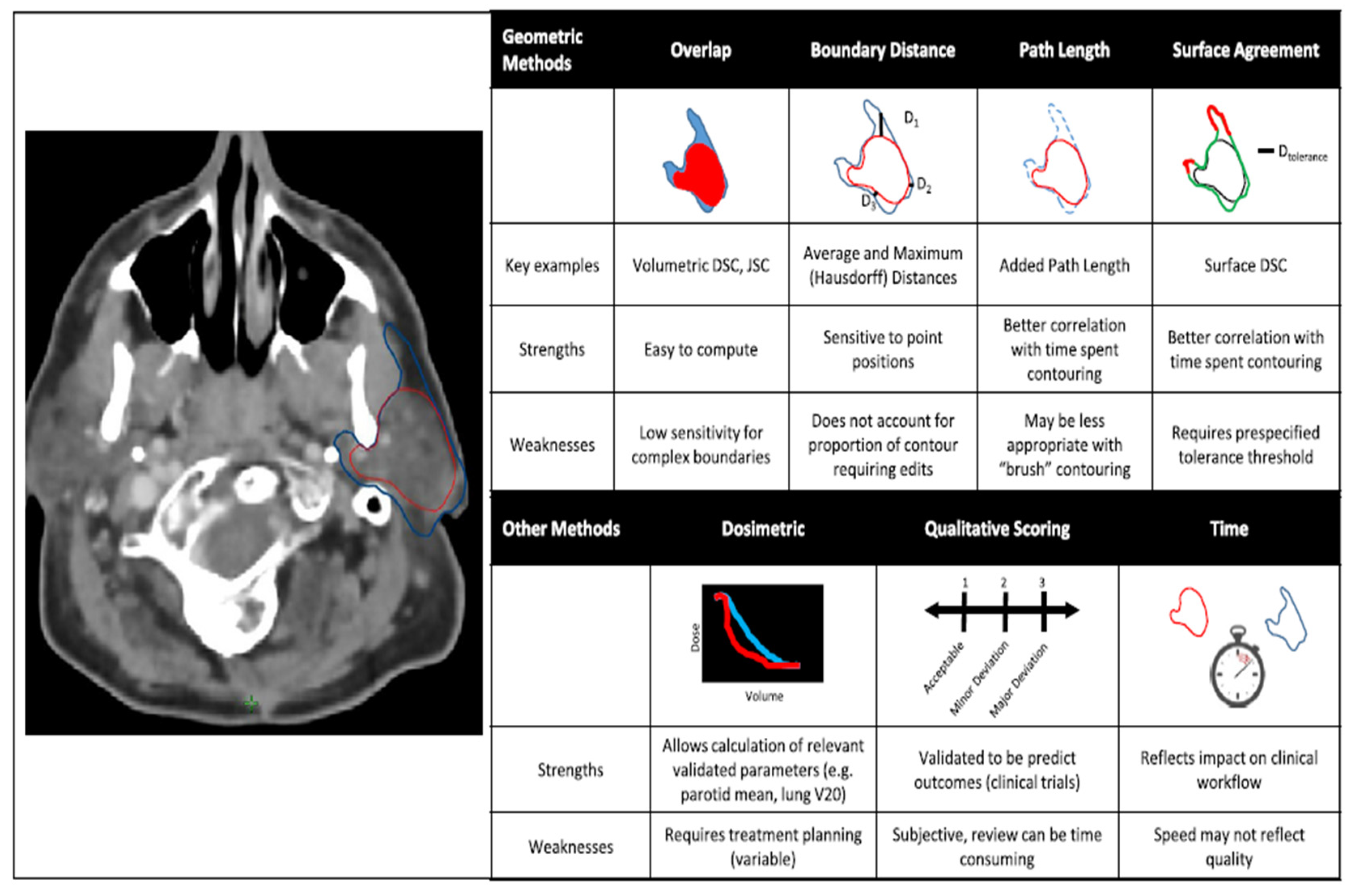

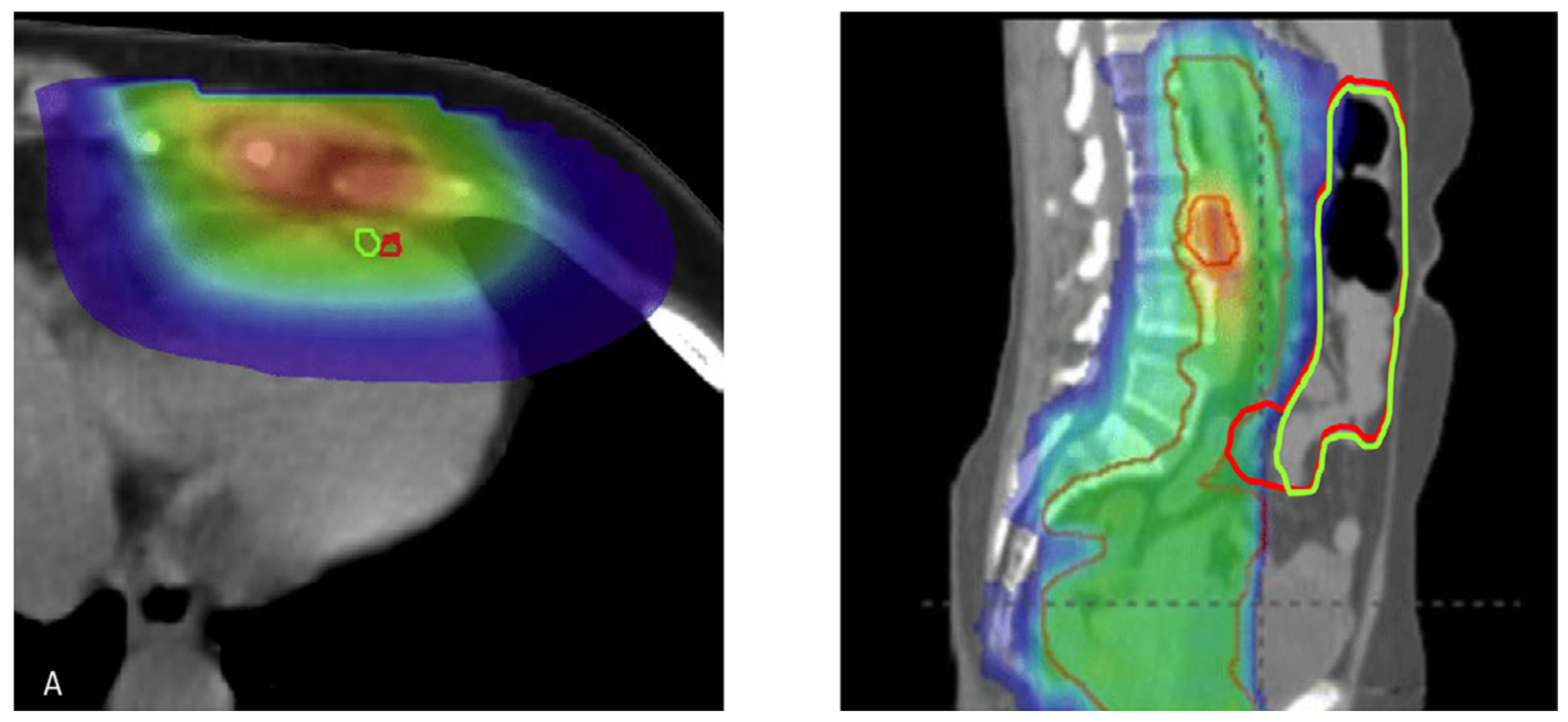

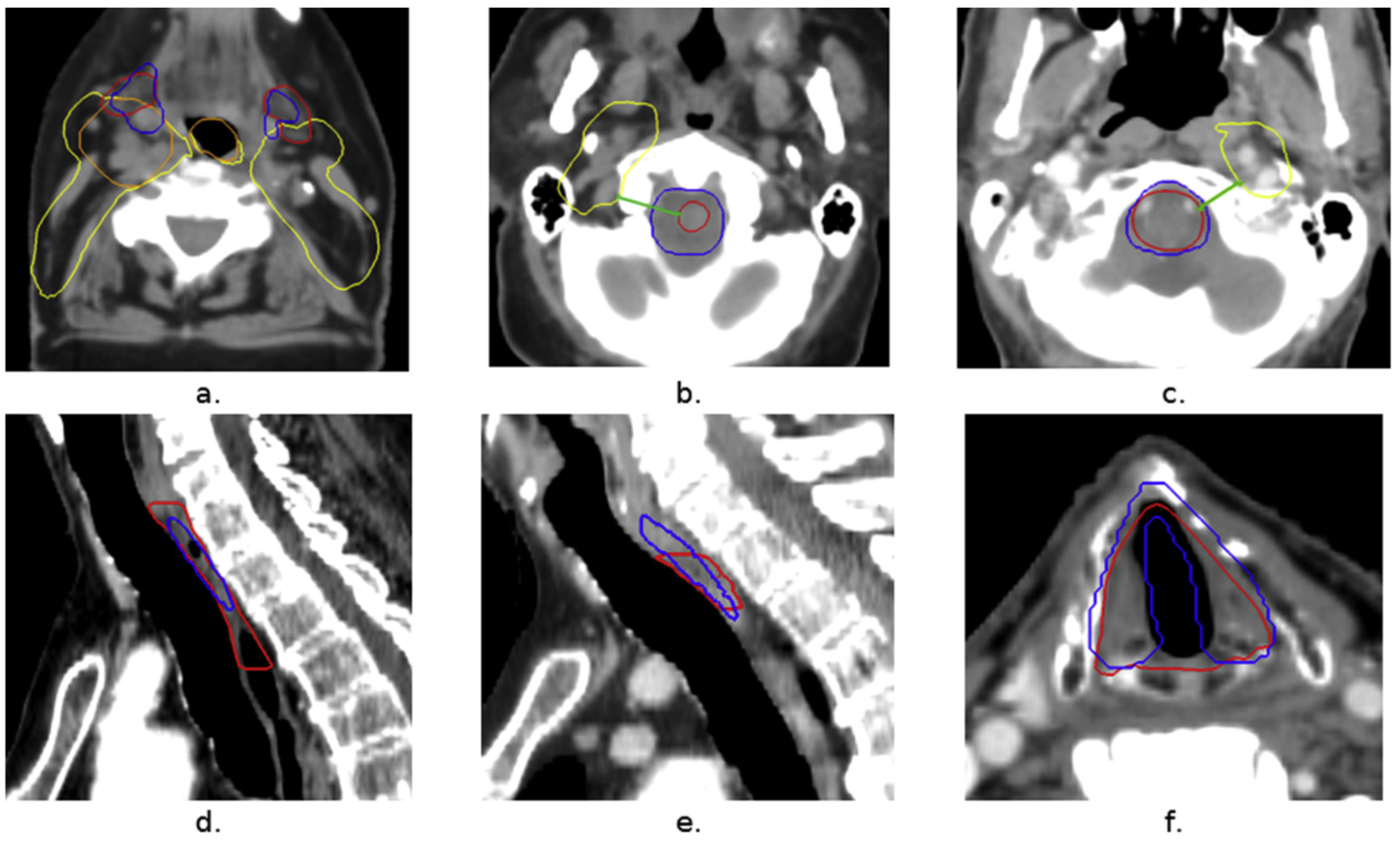

2.2. Radiation Therapy Planning

2.3. Chemotherapy Optimization

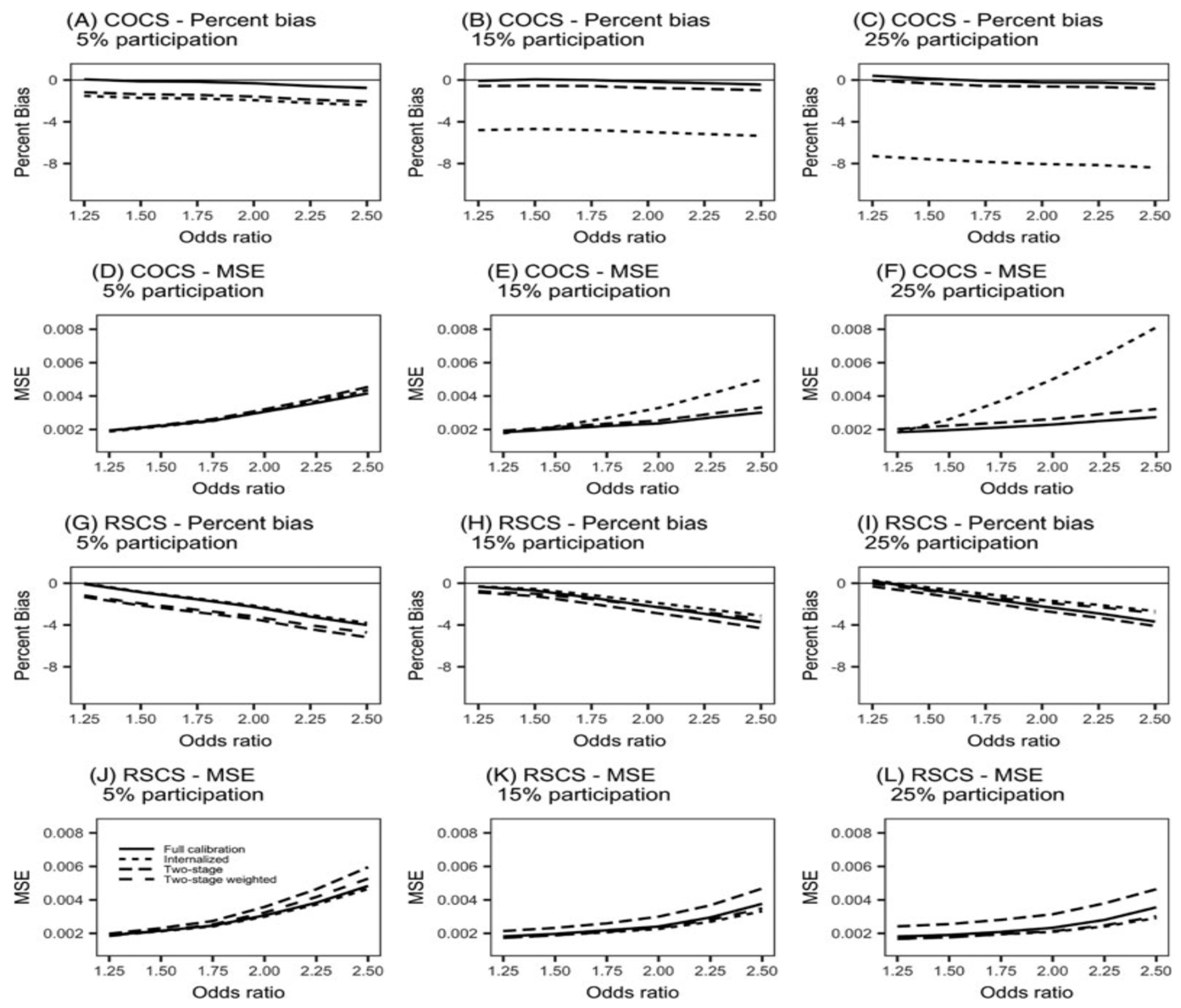

2.4. Clinical Trials and Biostatistics

2.5. Genomic Data Analysis

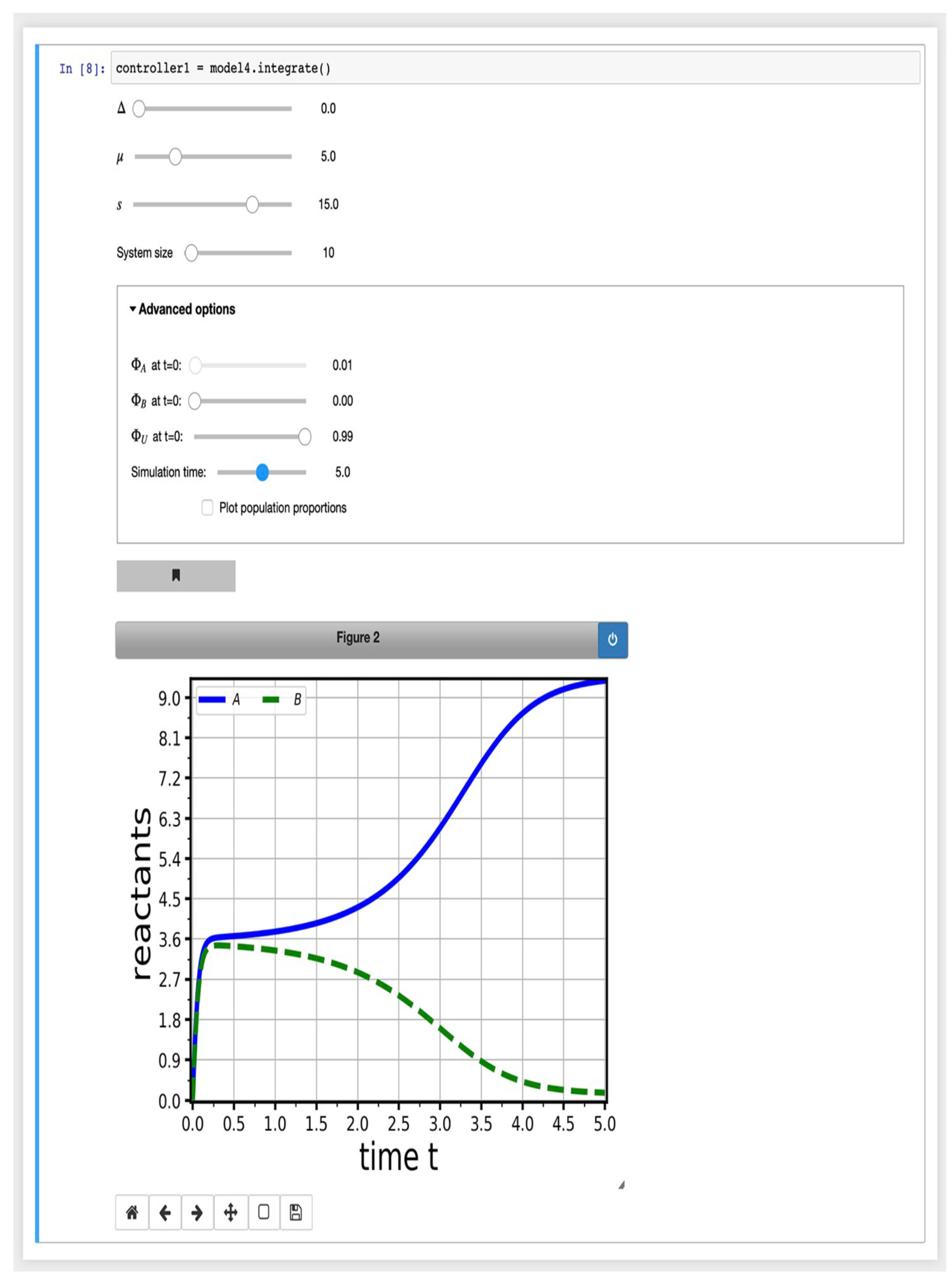

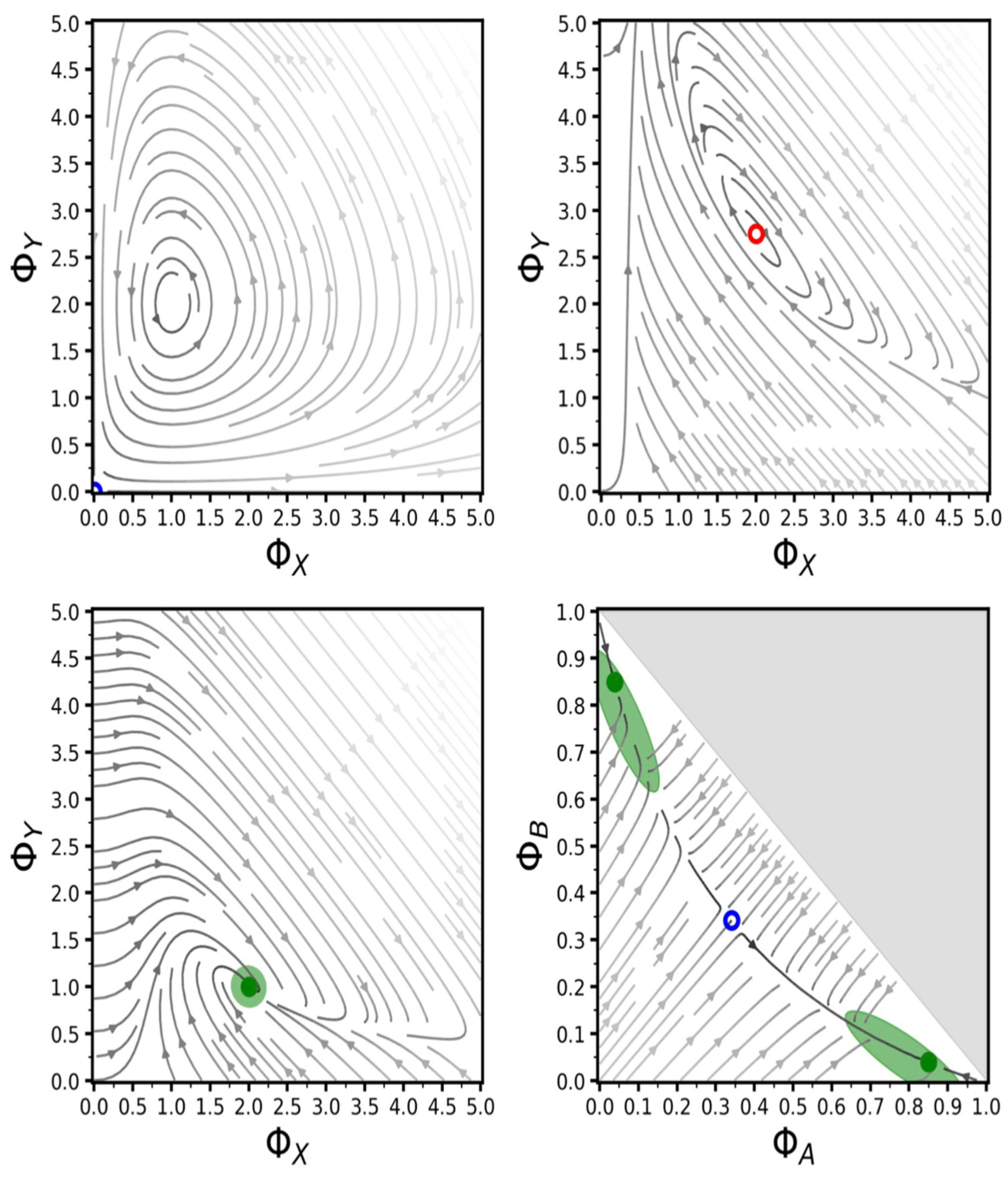

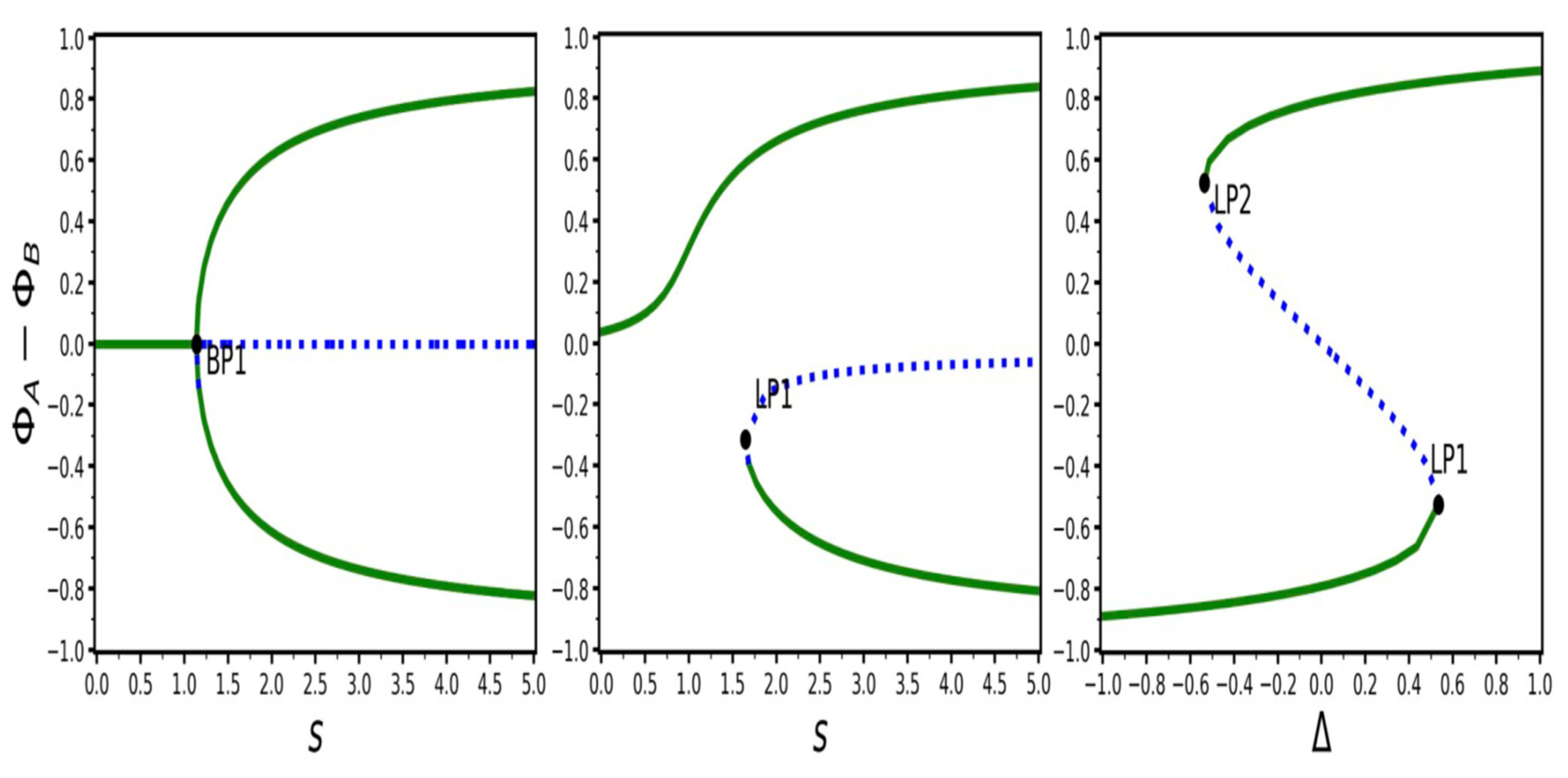

2.6. Immunotherapy and Systems Biology

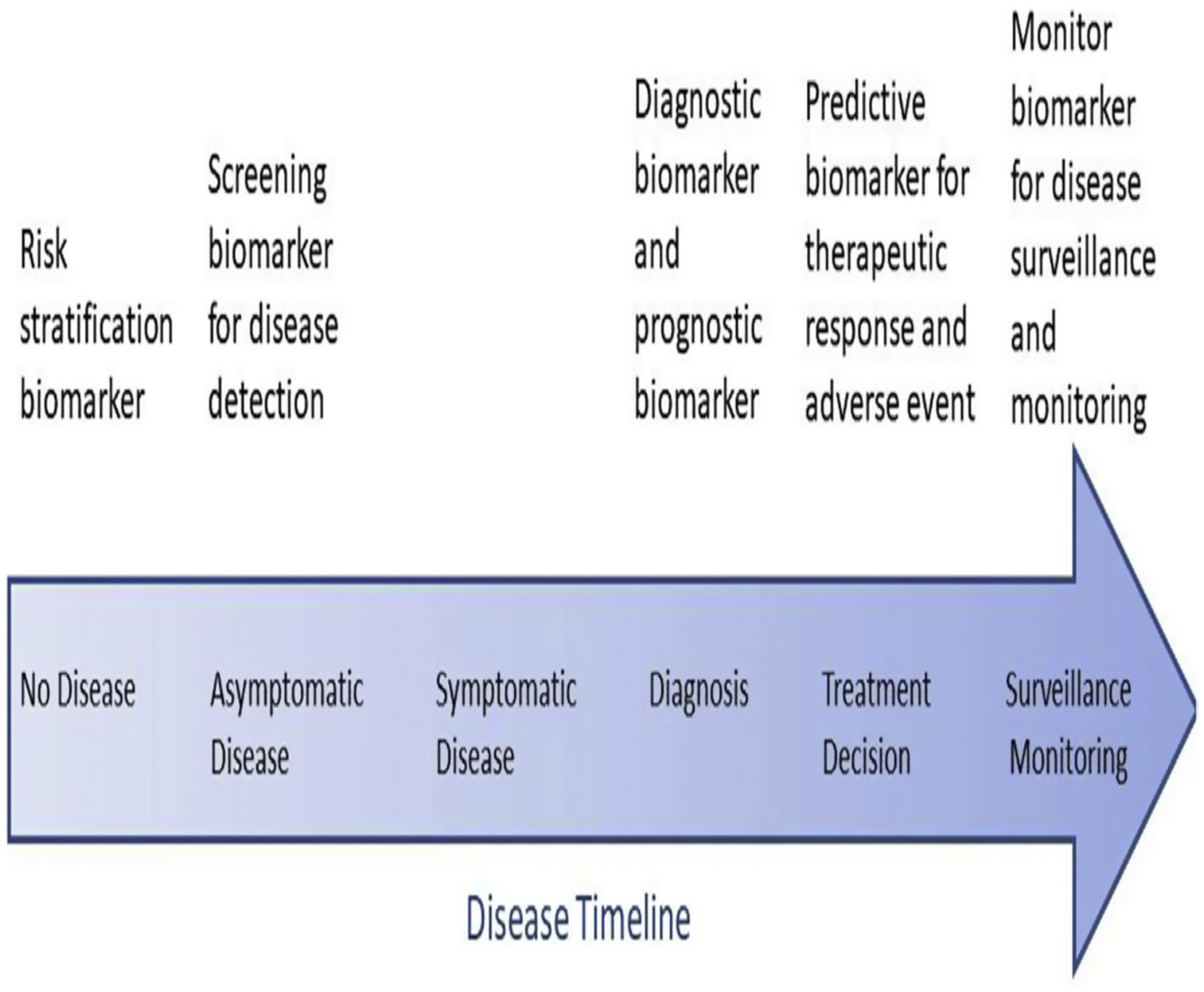

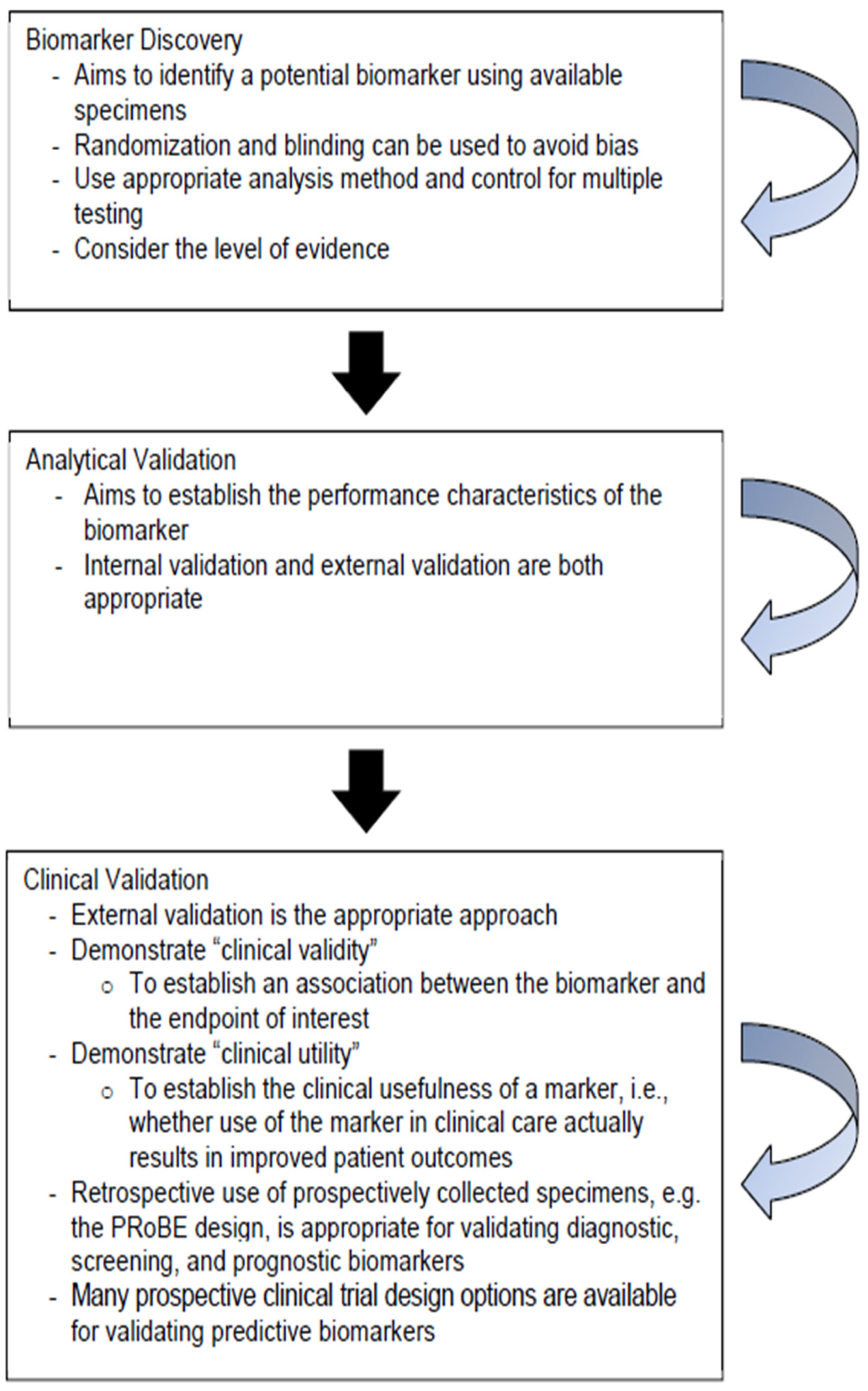

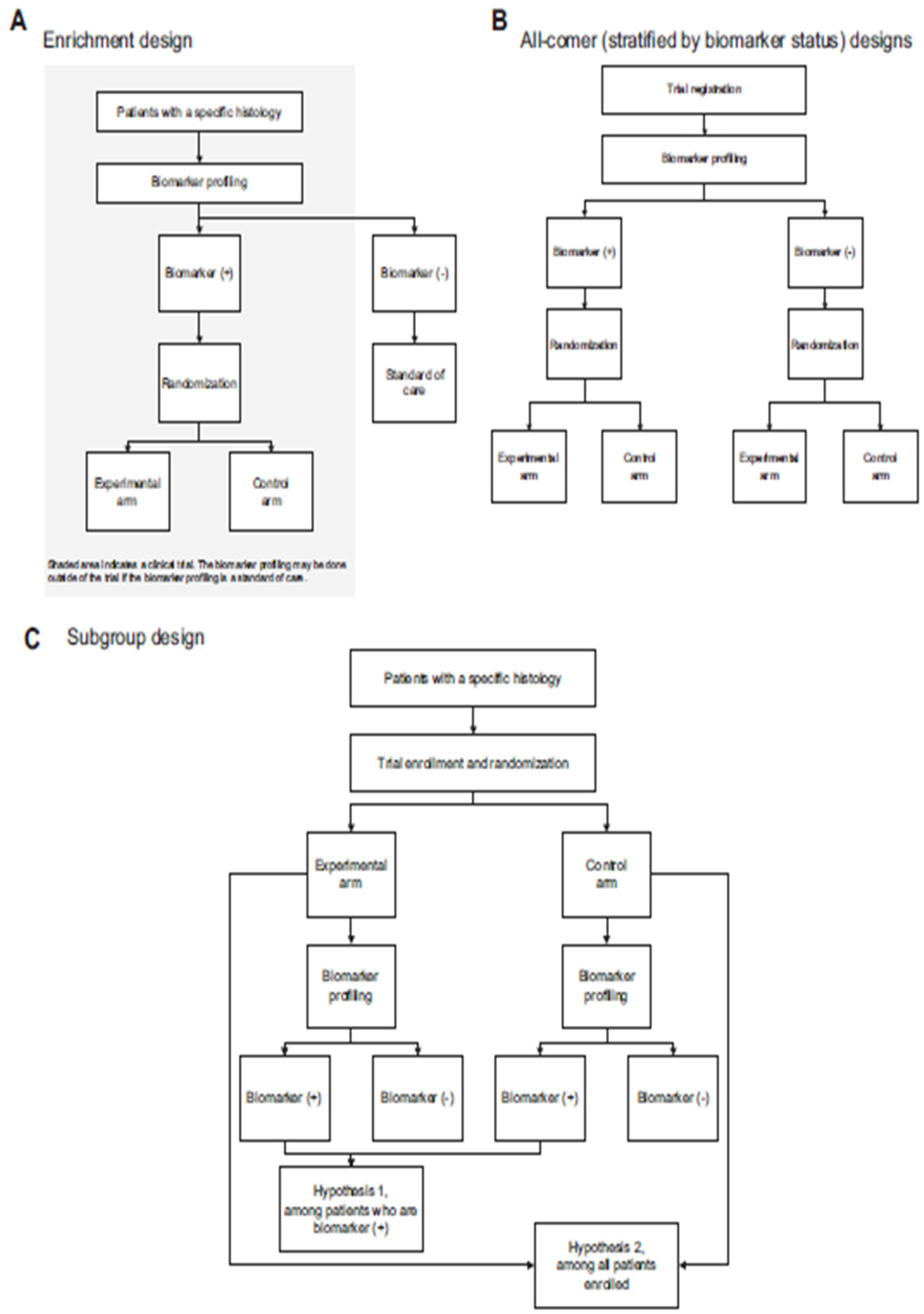

2.7. Tumor Biomarker Research

3. Conclusion, Open Problems and Futuristic Research Avenues

- Current research [4]does not fully explain how gut microbiota influences the effectiveness of radiotherapy and the serious side effects that can occur. Some scientists suggest that gut microbiota might play a role in the immune responses related to radiotherapy, but there is no direct evidence to support this. Understanding the connections between gut health and radiotherapy side effects could be a promising area for future research, potentially leading to new ways to reduce these side effects and enhance cancer treatment.

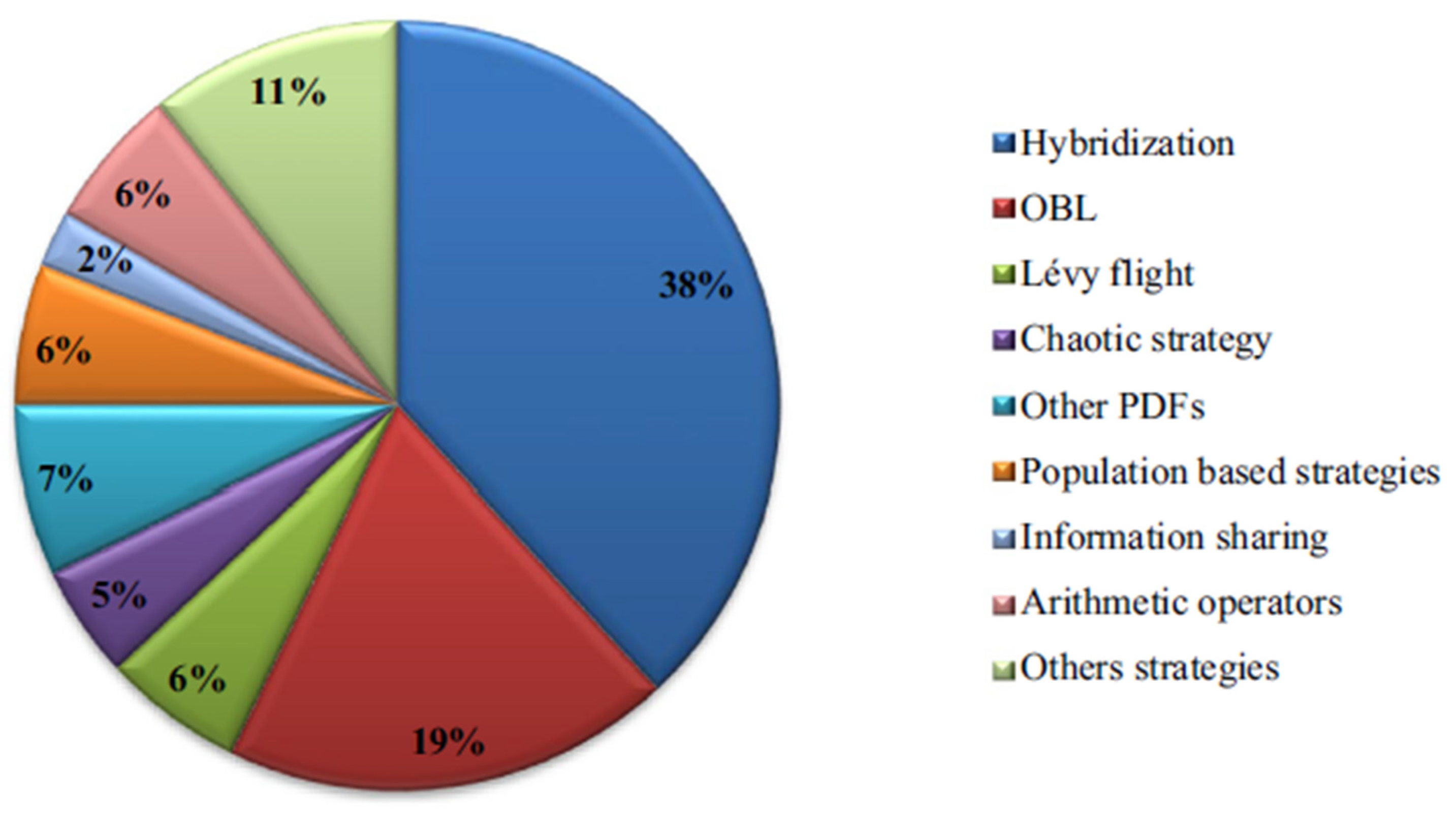

- The undertaken exposition in [11] has emerged some open problems, for example, improving the AOA (Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm). It suggests that more research should focus on adapting parameters like population size to make AOA more flexible for different problems. Additionally [11], it emphasizes the need for better communication and information sharing among solutions, exploring its applications in areas like machine learning and computer vision, and developing a mathematical framework to enhance understanding and effectiveness.

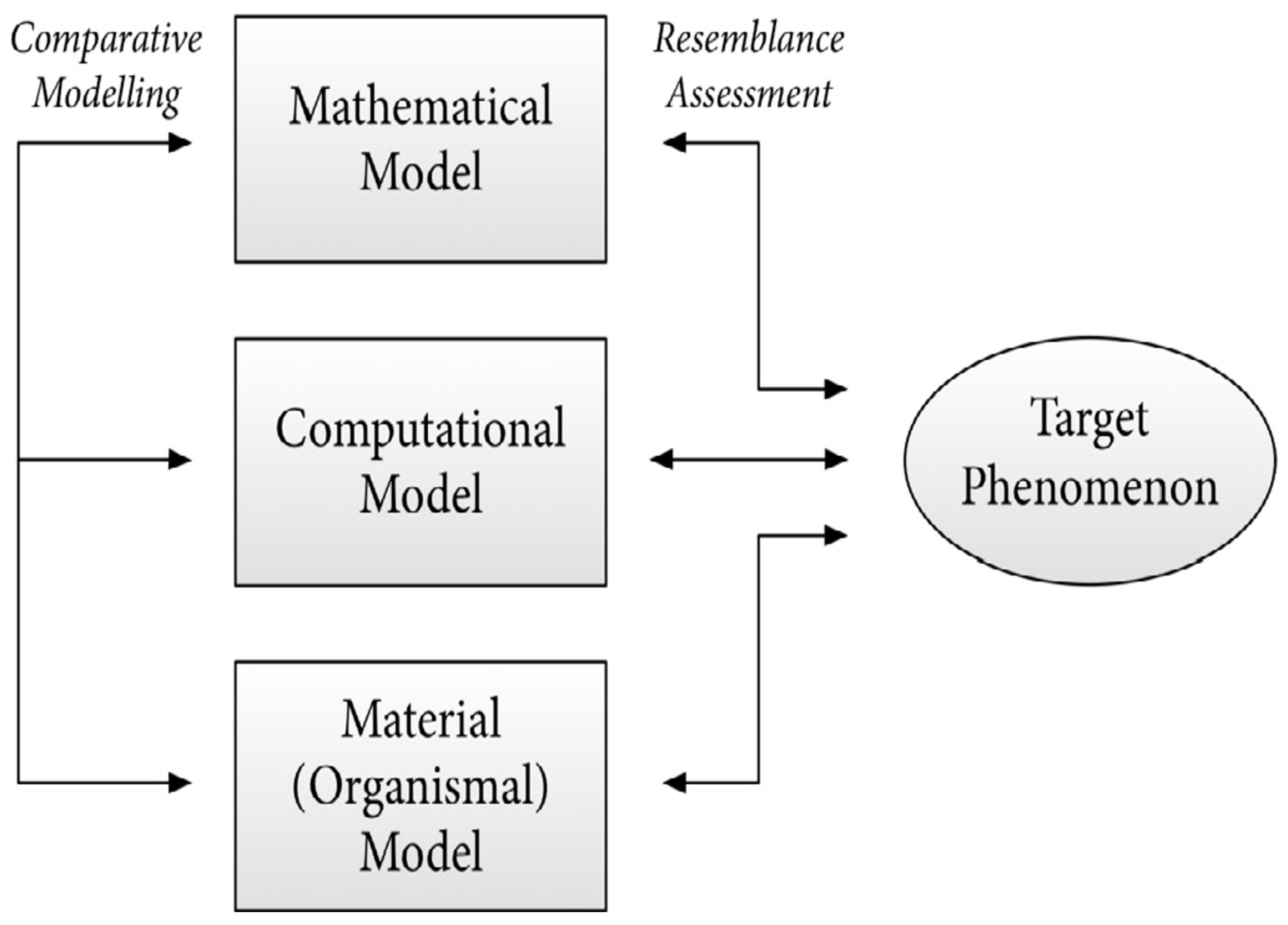

- It is acknowledged that while microbial and bacterial models offer many practical benefits for research, these advantages are not unique to microorganisms alone; other types of organisms can also provide useful insights. This triggers an open problem, yet unsolved till current, namely, exploring the history of microbial models to help researchers better understand the philosophical aspects of using multiple models in scientific research. This deeper understanding could enhance the undertaken scientific approach and interpret findings across different biological systems.

- It is to be noted [16], that there are not many well-established principles in biology, like the “universal” growth law, which makes most mathematical models used in cancer research based on observations rather than fundamental rules. Because of this [16], it’s hard to determine the best models for understanding how tumors grow, and these models need to be updated as new biological information becomes available. Additionally, many important factors, like how quickly cancer cells grow or how many are resistant to treatment, are not well-defined or measurable with current technology, limiting the models’ ability to accurately predict treatment outcomes.

- A key challenge [16] in creating predictive models for tumors is dealing with uncertainties in the data collected from experiments and the models themselves. Experimental data can be affected by random errors and inaccuracies [16], which can lead to wrong estimates of important factors like tumor size or protein levels. To address these uncertainties [16], researchers can use statistical methods that treat data and model parameters as probabilities, allowing for more accurate and reliable predictions about tumor behavior and treatment outcomes.

- For mathematical models to be useful in medicine, they need to work with real patient data [16], such as information from imaging, biopsies, and genetic tests that help identify the type and severity of tumors. This data can be used to set up the models or adjust their parameters when direct measurements are not possible. It is really a burning open problem to offer an exploratory approach on how to combine imaging techniques, like MRI and PET scans, with mathematical models to better understand tumor growth and behavior, which can lead to improved cancer treatments.

- If the main goal is to ensure that the contours created by auto-segmentation are clinically relevant [29], the best method is still to have a physician evaluate them, as this method has the strongest link to patient outcomes. However [29], this evaluation process can take a lot of time and effort, so there is a need for alternative measures that can be used to assess the quality of these automated systems more efficiently. The evaluation should also focus on specific goals [29], like how accurate the anatomical shapes are or how quickly the process can be done, depending on what is most important for the clinical situation.

- The main limitation of the study [31] is the lack of reliable “ground truth” data, which means that for some patients, the outline of the submandibular gland (SMG) can be clearly seen on CT scans, while for others, it is difficult to distinguish due to similar tissue densities. This can make accurate contouring challenging [31], and additional imaging techniques like MRI might be needed for better clarity. Other limitations include using only one evaluation metric for model performance, reducing the training area due to memory limits, and not testing the model on different datasets or types of treatment plans, which could affect the results.

- It is suggested [32] that the guidelines for GRID therapy should be adjusted according to specific treatment goals, like reducing the size of large tumors or enhancing the body’s immune response to cancer. As research in spatially fractionated radiation therapy (SFRT) continues to evolve, these guidelines must be updated to incorporate new findings and improve treatment effectiveness. This flexibility ensures that the therapy can be tailored to meet the unique needs of each patient.

- There is a significant gap [40] between research on outpatient chemotherapy operations management (OCP) and the use of advanced technologies from Industry 4.0, known as Health 4.0. Health 4.0 includes tools like cloud computing and big data, which can improve how chemotherapy services are automated and optimized. Integrating these technologies into existing models to enhance decision-making and service performance in outpatient clinics is a sophisticated open problem that needs to be solved.

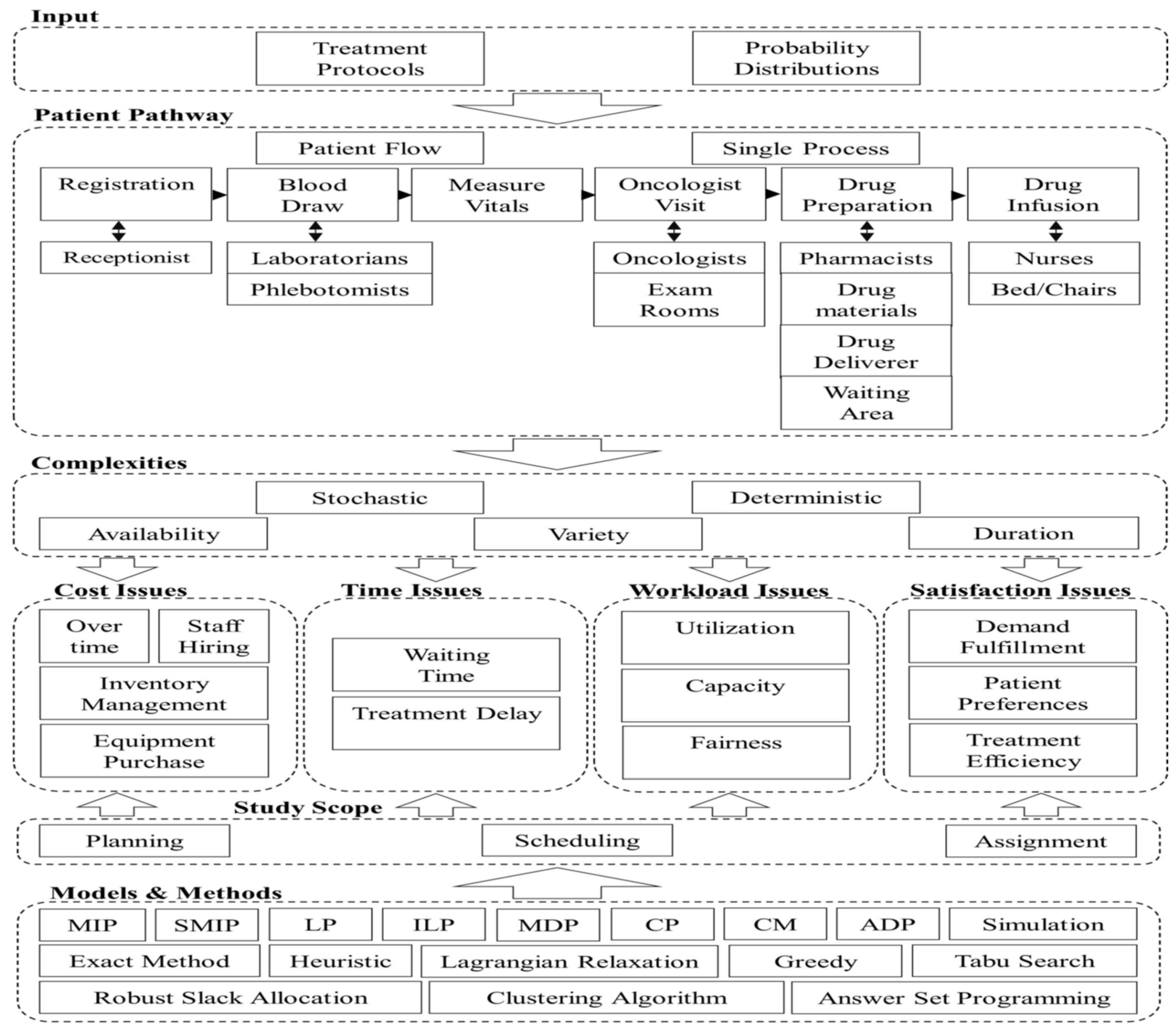

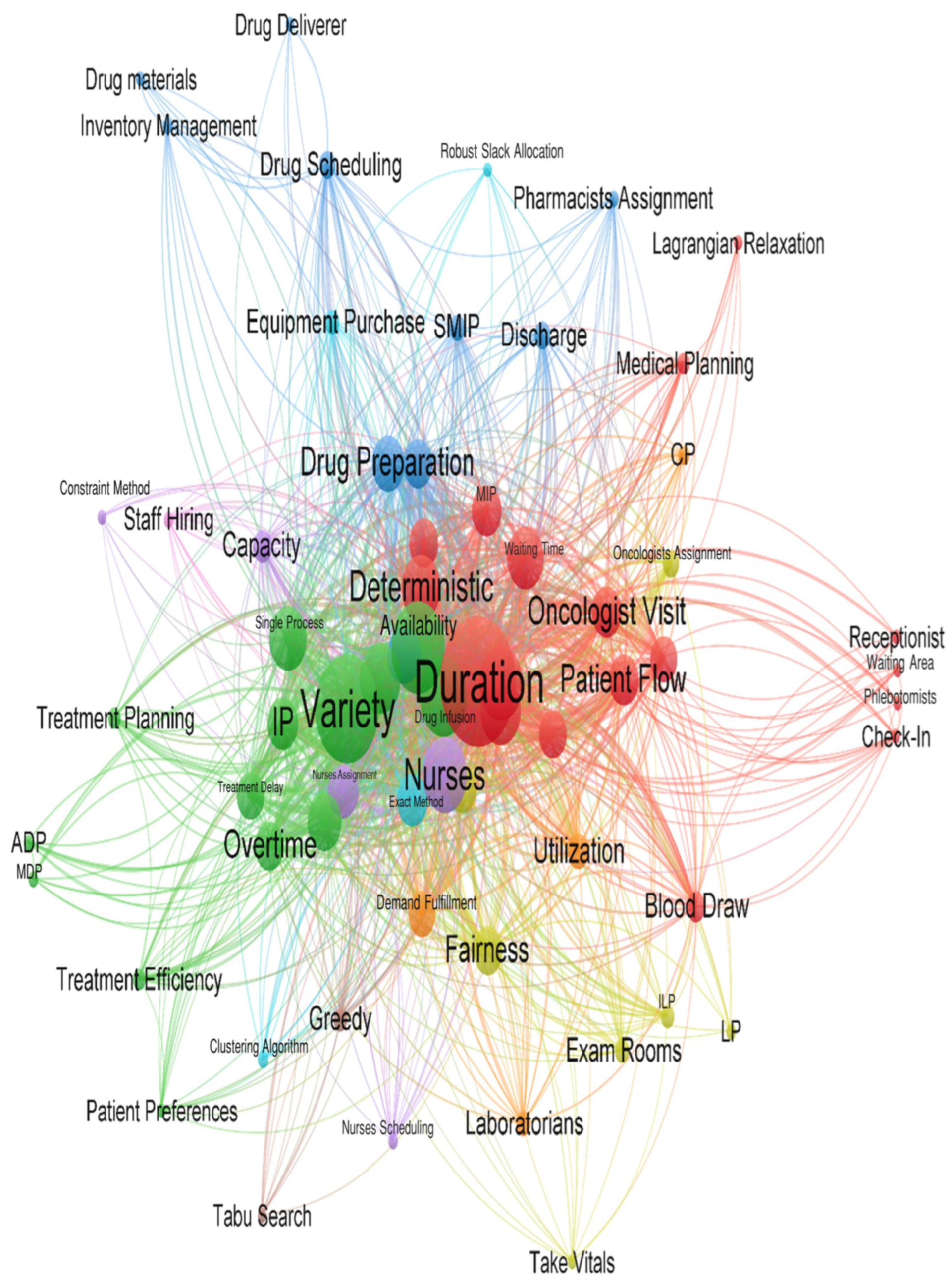

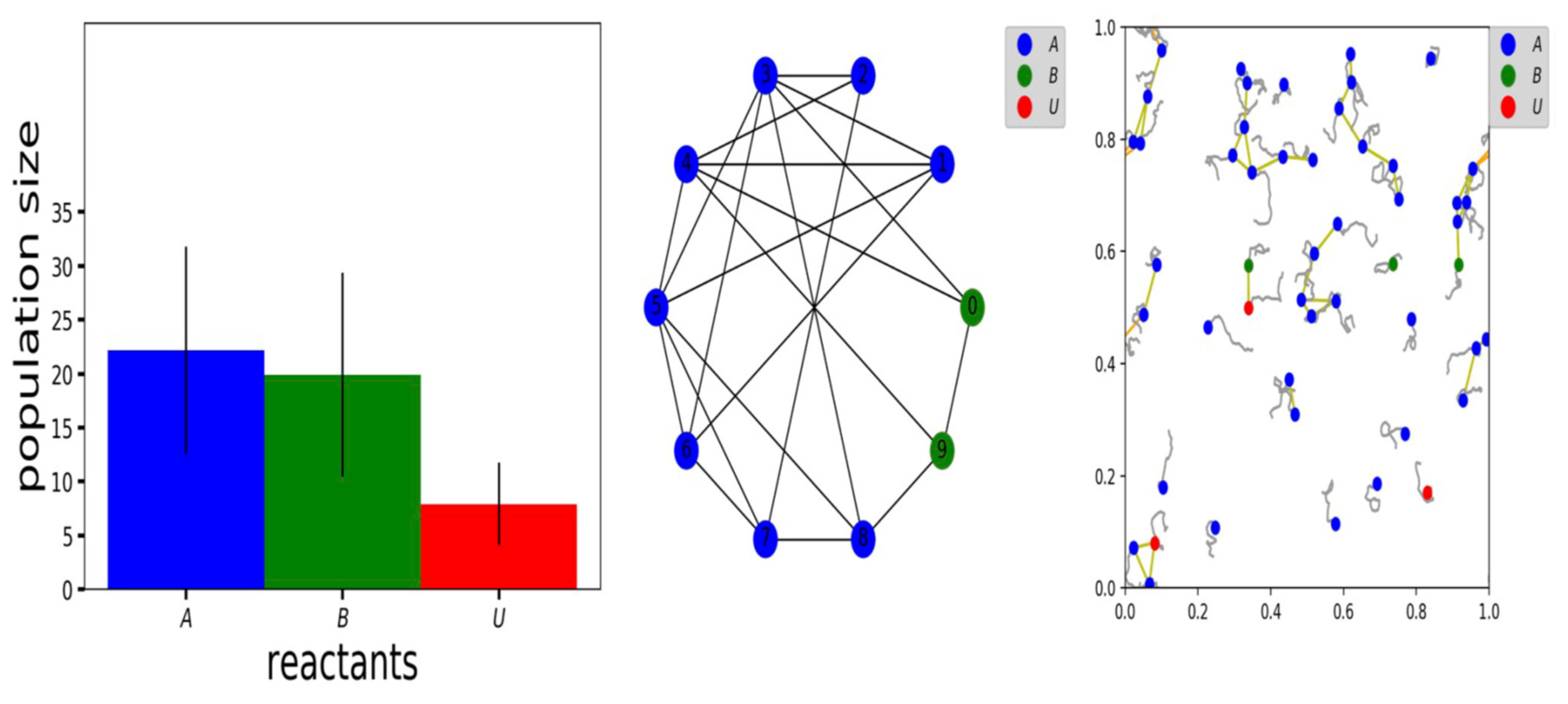

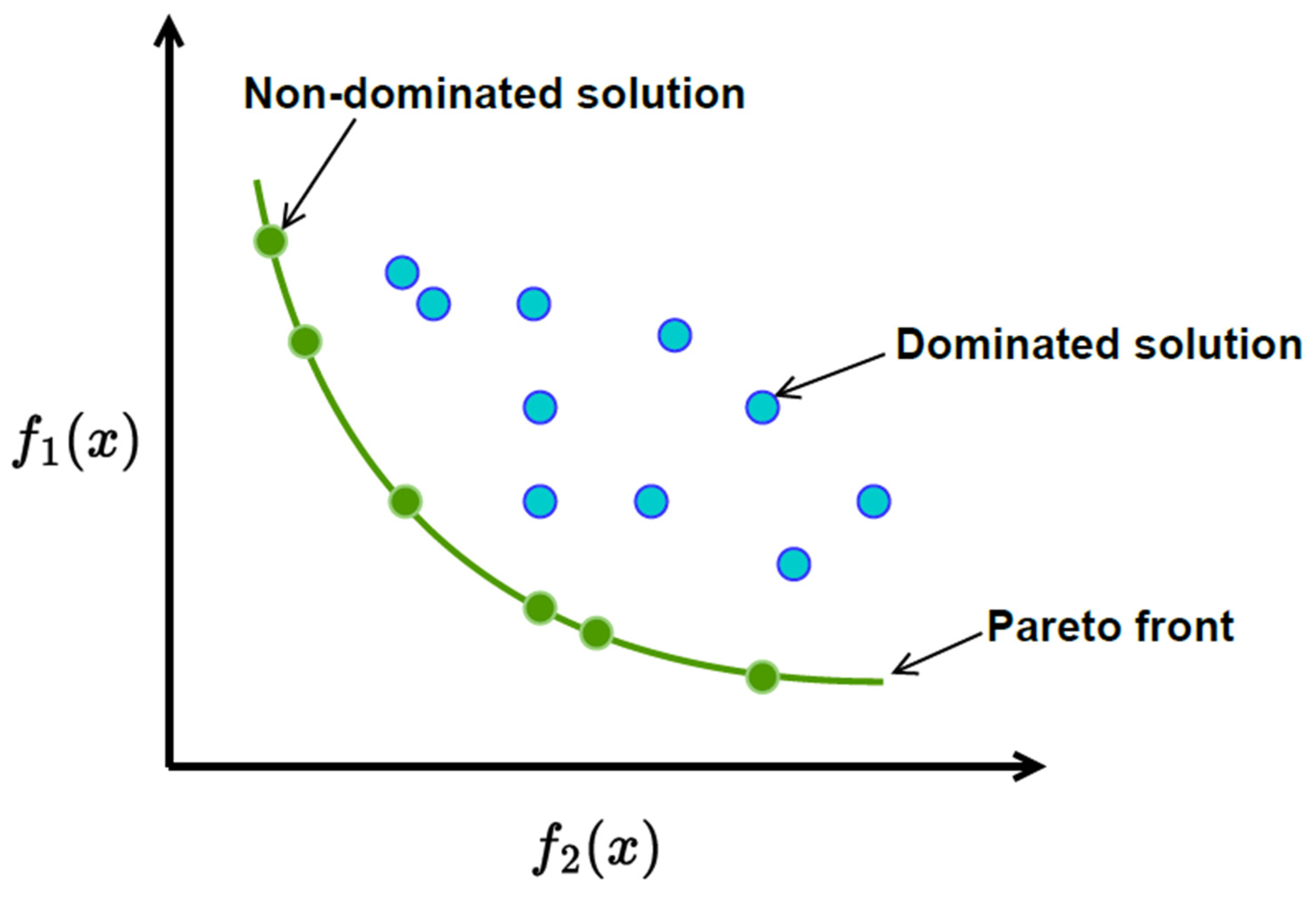

- The current state of research in optimizing outpatient chemotherapy planning (OCP)[40], highlighting that many existing studies are still in the development phase and have not fully addressed important gaps, identifying eight key areas, including creating a comprehensive optimization model that can improve performance without oversimplifying the problem. Additionally [40], there is a need for faster methods, known as heuristics, to solve complex OCP models effectively and to improve processes in real-world applications, as summarized by the following Figure (c.f., [40]).

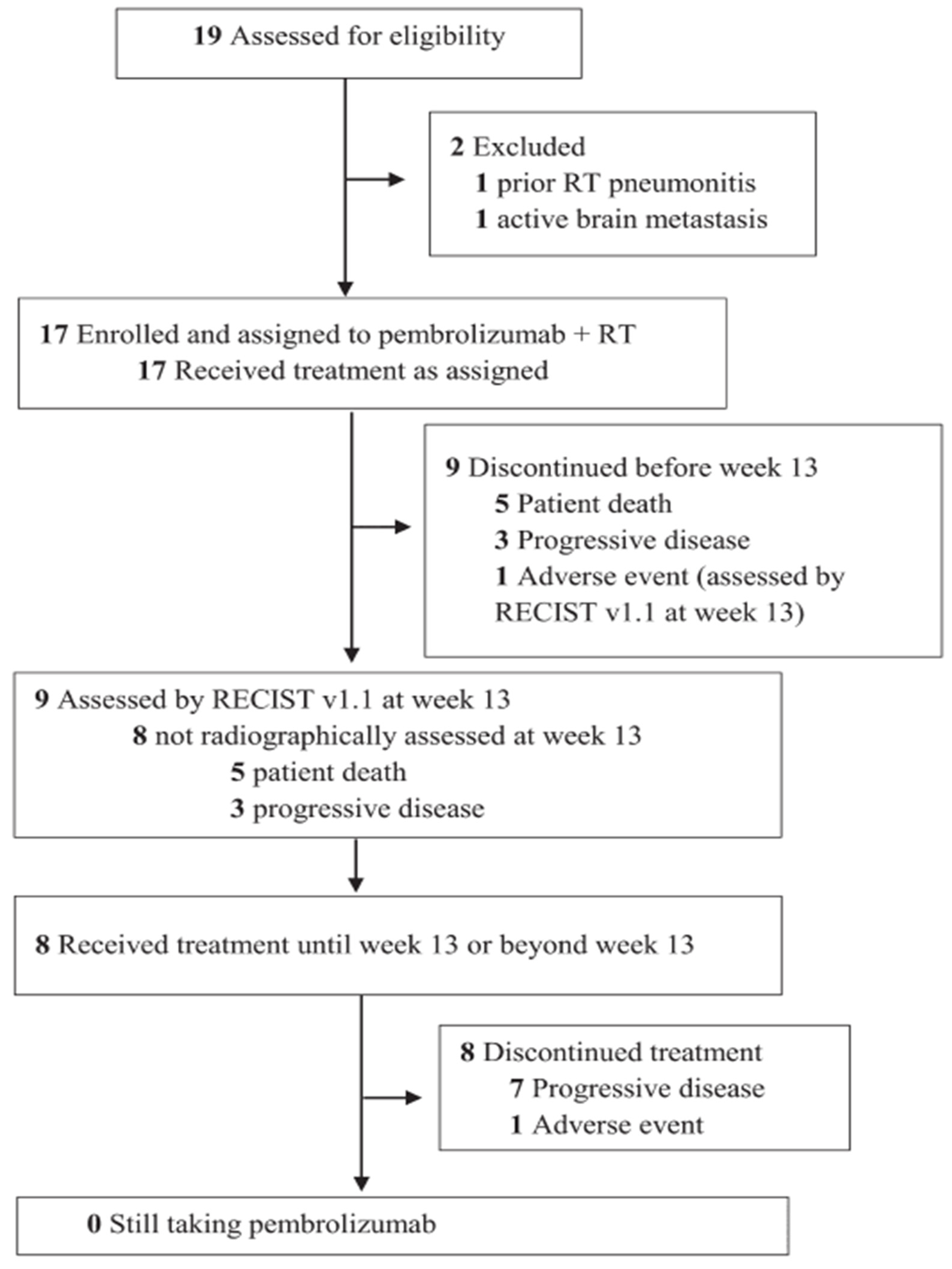

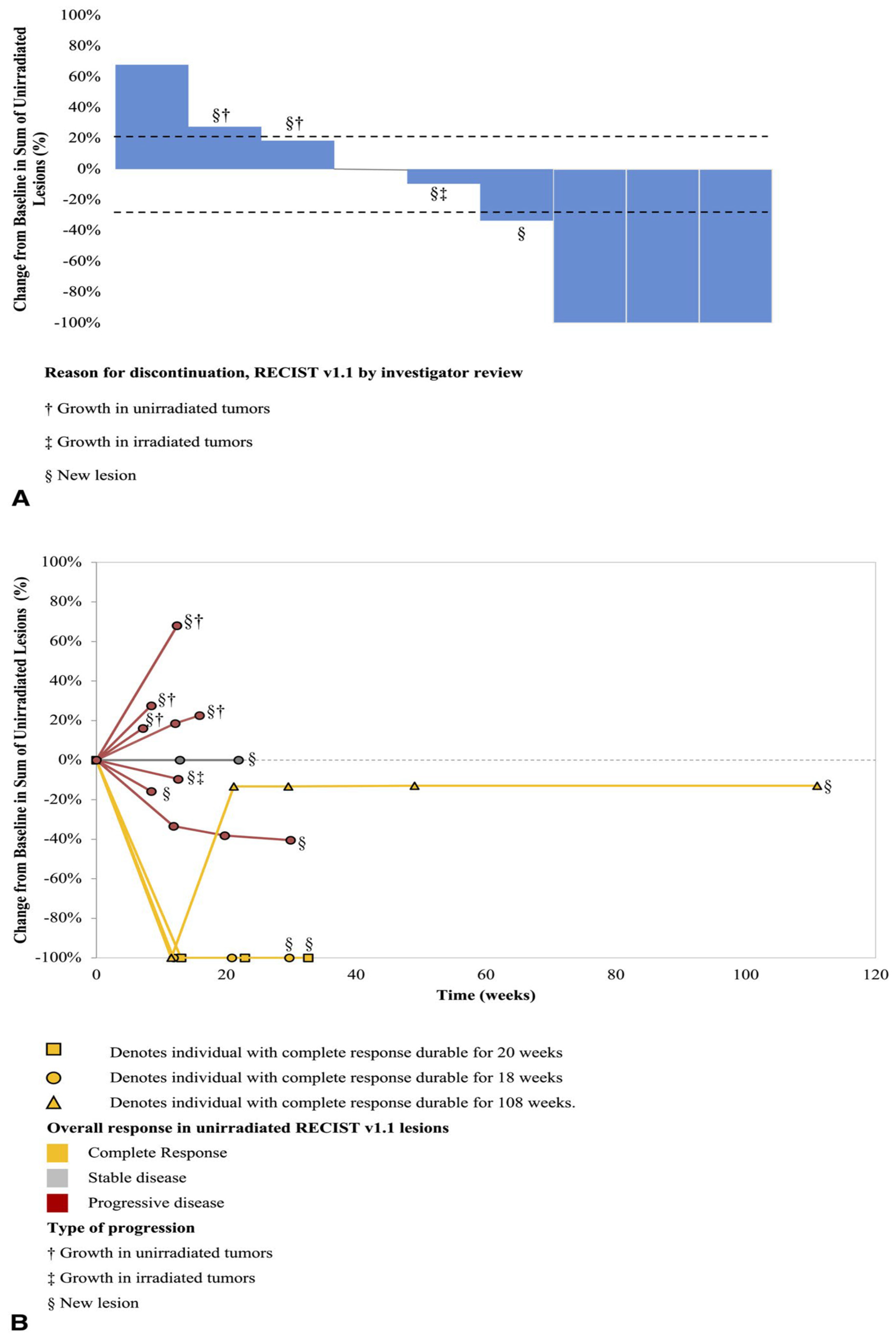

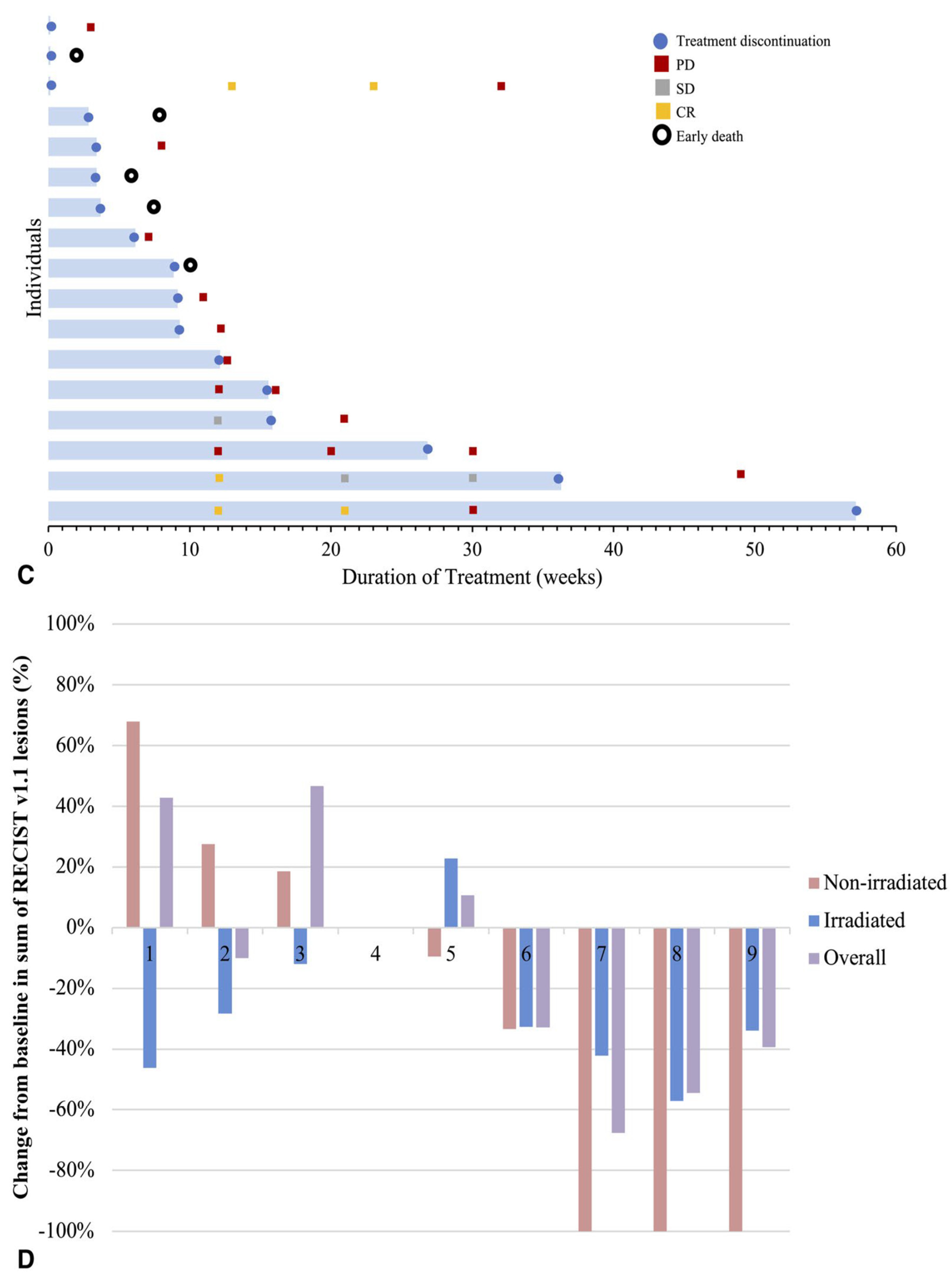

- The authors [55] found that giving pembrolizumab (an immunotherapy drug) and radiation therapy (RT) at the same time made it hard to see how much each treatment contributed to the overall effect. Because the number of patients was small [55], the researchers couldn’t analyze many important factors that might affect treatment response, like previous treatments or tumor characteristics. They [55] also noted differences in how tumors responded, with some tumors showing complete responses while others did not, which complicates understanding how effective the combination treatment really is.

- The study [76] acknowledged several limitations and suggests future directions for improving the mathematical model used in DC immunotherapy. Key issues include large discrepancies between experimental data and model predictions [76], which may stem from measurement errors or insufficient sample sizes. The authors [76] recommended incorporating more experimental data, especially regarding specific immune cell types [76], and conducting sensitivity analyses to simplify the model by focusing on the most important parameters, ultimately enhancing its accuracy and applicability in understanding tumor-immune interactions.

- A strong and effective team of scientists working together is essential for developing biomarkers [89], which are important tools for diagnosing and treating diseases. By encouraging collaboration among researchers, the goal is to speed up the process of taking new scientific discoveries from the lab (bench) to real-world medical applications (bedside). This teamwork ultimately aims to enhance patient care and improve health outcomes. Until current, this open problem has not been solved yet.

References

- Primac, I., Penning, A., & Fuks, F. (2022). Cancer epitranscriptomics in a nutshell. Current opinion in genetics & development, 75, 101924. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, E. G. (2023). In a nutshell. [CrossRef]

- El Rami, F. E., Barsoumian, H. B., & Khneizer, G. W. (2020). Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer therapeutic roadmap: current and novel approaches in a nutshell. Therapeutic advances in medical oncology, 12, 1758835920967238. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Ke, X., Zuo, D., Wang, Z., Fang, F., & Li, B. (2022). New insights into the relationship between gut microbiota and radiotherapy for cancer. Nutrients, 15(1), 48. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A., & Rao, L. N. (2021). Areca nut an ignored carcinogen of Asian continent in a nutshell. Journal of Global Oral Health, 4(1), 67-68. [CrossRef]

- Kirby, M. (2024). Prostate cancer in a nutshell. Trends in Urology & Men’s Health, 15(2), 17-18. [CrossRef]

- Pepple, N. M., Ekoriko, W. U., Idih, F. M., & Chidozie, V. O. (2020). Chemo preventive effect of methanol extract of Anacardium occidentale nut shell on ultra-violet radiation induced skin damage. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research, 14(9), 488-495. [CrossRef]

- Zombe, K., Nyirenda, J., Lumai, A., & Phiri, H. (2022). Impact of solvent type on total phenol and flavonoid content and sun protection factor of crude cashew nutshell liquid. Sustainable Chemistry, 3(3), 334-344. [CrossRef]

- Ziesche, S., & Yampolskiy, R. V. (2020). Towards the Mathematics of Intelligence. The Age of Artificial Intelligence: An Exploration, 1.

- Gill, P. E., Murray, W., & Wright, M. H. (2019). Practical optimization. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. [CrossRef]

- Dhal, K. G., Sasmal, B., Das, A., Ray, S., & Rai, R. (2023). A comprehensive survey on arithmetic optimization algorithm. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 30(5), 3379-3404. [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, T., Lancaster, K., & Rosengarten, M. (2020). A model society: maths, models and expertise in viral outbreaks. Critical Public Health, 30(3), 253-256. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J. A., Reina, A., & Bose, T. (2019). Multiscale modelling tool: Mathematical modelling of collective behaviour without the maths. PloS one, 14(9), e0222906. [CrossRef]

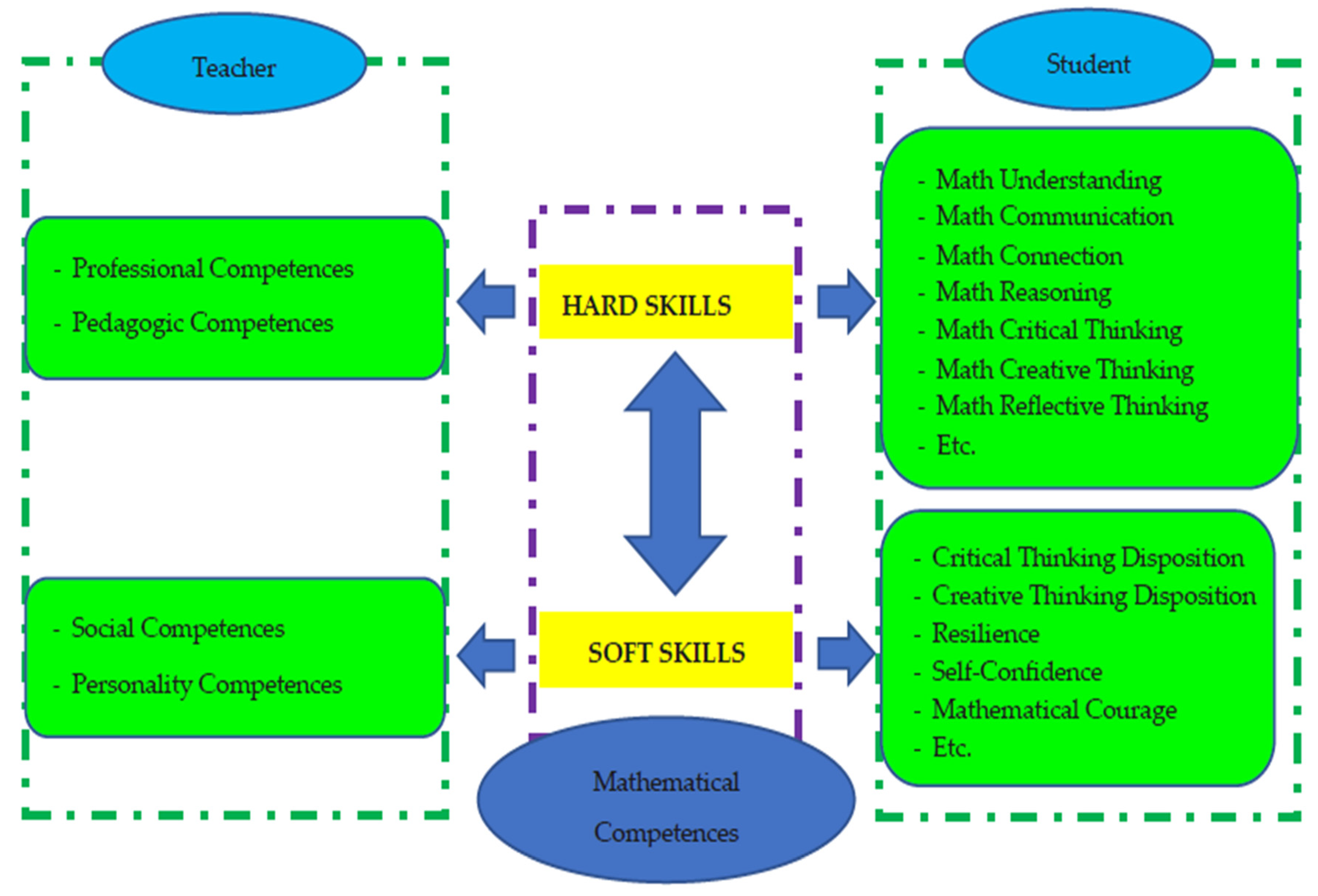

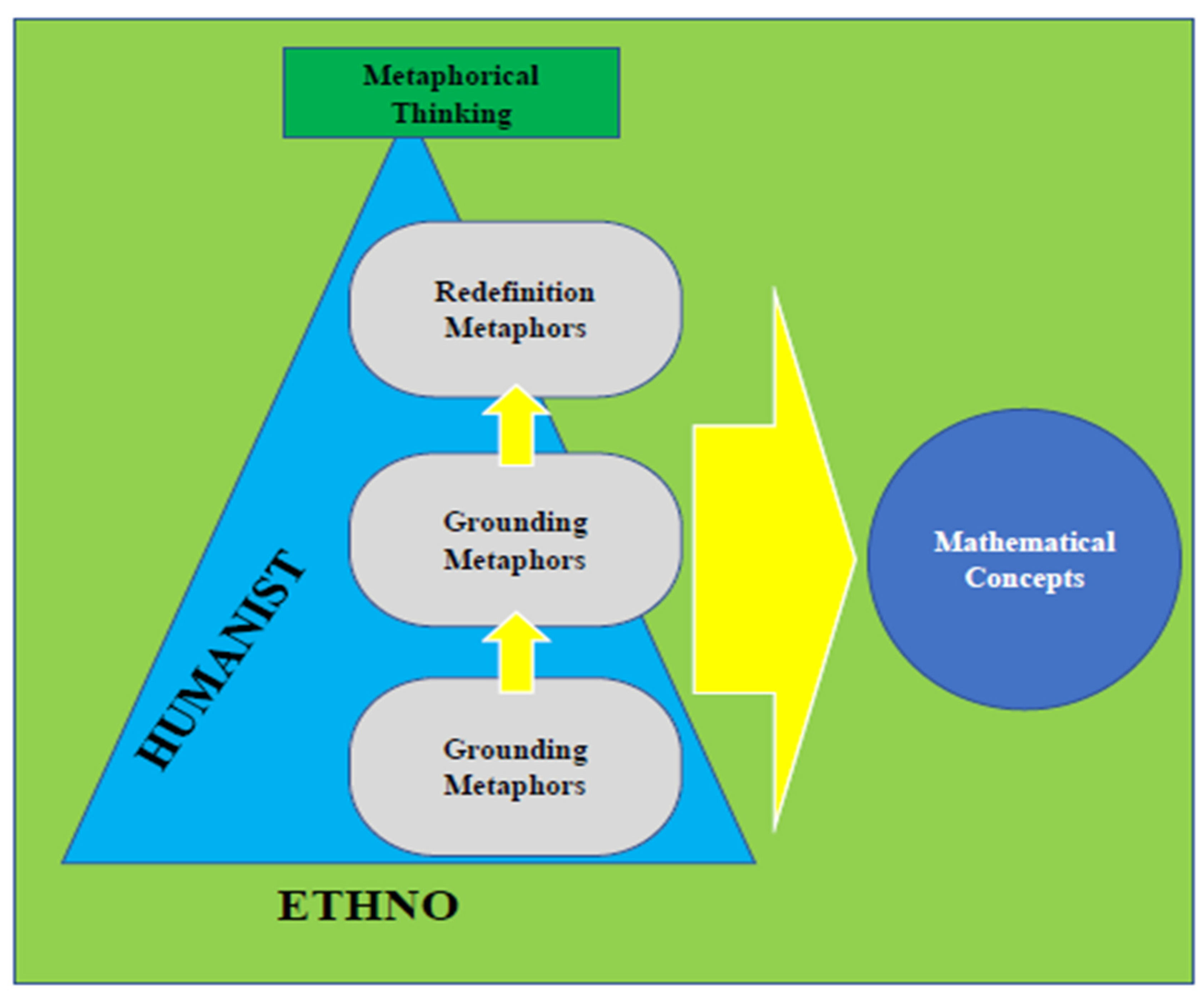

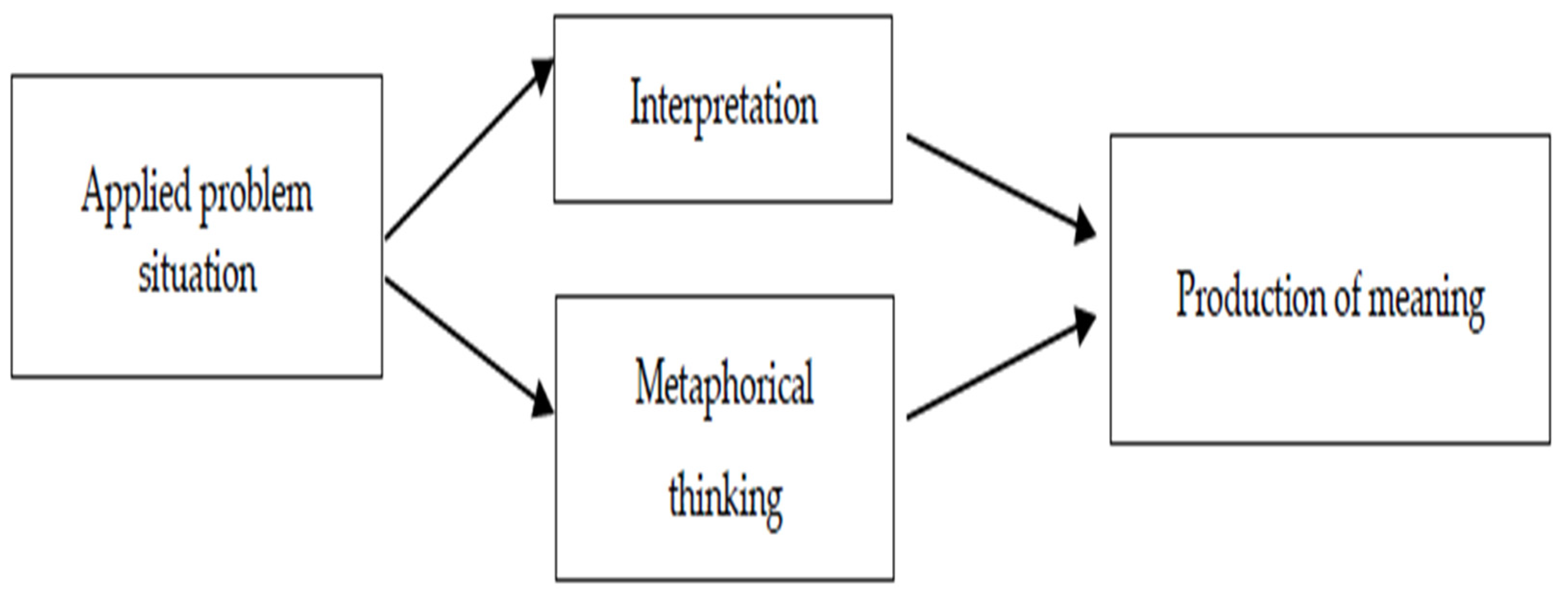

- Hendriana, H., Prahmana, R. C. I., Ristiana, M. G., Rohaeti, E. E., & Hidayat, W. (2022, October). The theoretical framework on humanist ethno-metaphorical mathematics learning model: An impactful insight in learning mathematics. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 7, p. 1030471). Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, M. A., & Parke, E. C. (2018). Microbes, mathematics, and models. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, 72, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, A. M., Lima, E. A., Hormuth, D. A., McKenna, M. T., Feng, X., Ekrut, D. A., ... & Yankeelov, T. E. (2018). Mathematical models of tumor cell proliferation: A review of the literature. Expert review of anticancer therapy, 18(12), 1271-1286. [CrossRef]

- Ira, J. I., Islam, M. S., Misra, J. C., & Kamrujjaman, M. (2020). Mathematical modelling of the dynamics of tumor growth and its optimal control. [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, S., Rosli, N. B., & Binti Mazalan, M. S. A. (2019, November). Mathematical modeling of cancer growth process: a review. In Journal of physics: conference series (Vol. 1366, No. 1, p. 012018). IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Wei, H. C. (2018). A mathematical model of tumor growth with Beddington–DeAngelis functional response: a case of cancer without disease. Journal of biological dynamics, 12(1), 194-210. [CrossRef]

- Rivaz, A., Azizian, M., & Soltani, M. (2019). Various mathematical models of tumor growth with reference to cancer stem cells: a review. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions A: Science, 43, 687-700. [CrossRef]

- Flegg, J. A., & Nataraj, N. (2019). Mathematical Modelling and Avascular Tumor Growth: Interdisciplinary Research. Resonance, 24, 313-325. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X., & Sweidan, M. (2018). A mathematical model of angiogenesis and tumor growth: analysis and application in anti-angiogenesis therapy. Journal of Mathematical Biology, 77, 1589-1622. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Hussain, M., Ghaffar, A., Ali, Z., Nisar, K. S., Alharthi, M. R., & Jamshed, W. (2021). Numerical simulations and analysis for mathematical model of avascular tumor growth using Gompertz growth rate function. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 60(4), 3731-3740. [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, S., & Gooding, R. J. (2018). The importance of chaotic attractors in modelling tumor growth. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 507, 268-277. [CrossRef]

- Trobia, J., Tian, K., Batista, A. M., Grebogi, C., Ren, H. P., Santos, M. S., ... & Iarosz, K. C. (2021). Mathematical model of brain tumor growth with drug resistance. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 103, 106013. [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, K. P., & Aktar, F. (2020). Mathematically modelling inflammation as a promoter of tumor growth. Mathematical medicine and biology: a journal of the IMA, 37(4), 491-514. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, M., & Kolobov, A. (2020). Investigation of solid tumor progression with account of proliferation/migration dichotomy via Darwinian mathematical model. Journal of Mathematical Biology, 80(3), 601-626. [CrossRef]

- Bull, J. A., Mech, F., Quaiser, T., Waters, S. L., & Byrne, H. M. (2020). Mathematical modelling reveals cellular dynamics within tumor spheroids. PLoS computational biology, 16(8), e1007961. [CrossRef]

- Sherer, M. V., Lin, D., Elguindi, S., Duke, S., Tan, L. T., Cacicedo, J., ... & Gillespie, E. F. (2021). Metrics to evaluate the performance of auto-segmentation for radiation treatment planning: A critical review. Radiotherapy and Oncology, 160, 185-191. [CrossRef]

- Giglioli, F. R., Garibaldi, C., Blanck, O., Villaggi, E., Russo, S., Esposito, M., ... & Mancosu, P. (2020). Dosimetric multicenter planning comparison studies for stereotactic body radiation therapy: methodology and future perspectives. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, 106(2), 403-412. [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, W., Dahele, M., Brandao, H. R., Delaney, A. R., Slotman, B. J., & Verbakel, W. F. (2019). Deep learning-based delineation of head and neck organs at risk: geometric and dosimetric evaluation. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, 104(3), 677-684. [CrossRef]

- Andres, E. A., Fidon, L., Vakalopoulou, M., Lerousseau, M., Carré, A., Sun, R., ... & Robert, C. (2020). Dosimetry-driven quality measure of brain pseudo computed tomography generated from deep learning for MRI-only radiation therapy treatment planning. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, 108(3), 813-823. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Wu, X., Zhang, X., Chang, S. X., Megooni, A., Donnelly, E. D., ... & Mayr, N. A. (2020). Photon GRID radiation therapy: a physics and dosimetry white paper from the Radiosurgery Society (RSS) GRID/LATTICE, microbeam and FLASH Radiotherapy Working Group. Radiation research, 194(6), 665-677. [CrossRef]

- Tino, R., Yeo, A., Leary, M., Brandt, M., & Kron, T. (2019). A systematic review on 3D-printed imaging and dosimetry phantoms in radiation therapy. Technology in cancer research & treatment, 18, 1533033819870208. [CrossRef]

- Dudas, D., Saghand, P. G., Dilling, T. J., Perez, B. A., Rosenberg, S. A., & El Naqa, I. (2024). Deep learning-guided dosimetry for mitigating local failure of patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving stereotactic body radiation therapy. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, 119(3), 990-1000. [CrossRef]

- Hachadorian, R., Bruza, P., Jermyn, M., Mazhar, A., Cuccia, D., Jarvis, L., ... & Pogue, B. (2019). Correcting Cherenkov light attenuation in tissue using spatial frequency domain imaging for quantitative surface dosimetry during whole breast radiation therapy. Journal of biomedical optics, 24(7), 071609-071609. [CrossRef]

- Chin, S., Eccles, C. L., McWilliam, A., Chuter, R., Walker, E., Whitehurst, P., ... & Choudhury, A. (2020). Magnetic resonance-guided radiation therapy: a review. Journal of medical imaging and radiation oncology, 64(1), 163-177. [CrossRef]

- Jones, S., Thompson, K., Porter, B., Shepherd, M., Sapkaroski, D., Grimshaw, A., & Hargrave, C. (2024). Automation and artificial intelligence in radiation therapy treatment planning. Journal of Medical Radiation Sciences, 71(2), 290-298. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Kim, J., Kumarasiri, A., Mayyas, E., Brown, S. L., Wen, N., ... & Chetty, I. J. (2018). An automated dose tracking system for adaptive radiation therapy. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine, 154, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Hadid, M., Elomri, A., El Mekkawy, T., Jouini, O., Kerbache, L., & Hamad, A. (2022). Operations management of outpatient chemotherapy process: An optimization-oriented comprehensive review. Operations Research Perspectives, 9, 100214. [CrossRef]

- Dömény, M. F., Puskás, M., Kovács, L., & Drexler, D. A. (2024, May). A review of multi-objective optimization algorithms in the field of chemotherapy optimization. In 2024 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI) (pp. 000345-000350). IEEE.

- Bräutigam, K. (2024). Optimization of chemotherapy regimens using mathematical programming. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 191, 110078. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. L., Bach, S. M., & Looker, S. A. (2019). Chemotherapy scheduling template development using an optimization approach. International journal of health care quality assurance, 32(1), 59-70. [CrossRef]

- Samy, P. G., Kanesan, J., & Tiu, Z. C. (2023). Optimization of chemotherapy using hybrid optimal control and swarm intelligence. IEEe Access, 11, 28873-28886. [CrossRef]

- Shindi, O., Kanesan, J., Kendall, G., & Ramanathan, A. (2020). The combined effect of optimal control and swarm intelligence on optimization of cancer chemotherapy. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 189, 105327. [CrossRef]

- Bodzioch, M., Bajger, P., & Foryś, U. (2021). Angiogenesis and chemotherapy resistance: Optimizing chemotherapy scheduling using mathematical modeling. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 147(8), 2281-2299. [CrossRef]

- Dömény, M. F., Puskás, M., Kovács, L., & Drexler, D. A. (2023, May). In silico chemotherapy optimization with genetic algorithm. In 2023 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI) (pp. 000097-000102). IEEE.

- Abdulrashid, I., Delen, D., Usman, B., Uzochukwu, M. I., & Ahmed, I. (2024). A multi-objective optimization framework for determining optimal chemotherapy dosing and treatment duration. Healthcare Analytics, 5, 100335. [CrossRef]

- Dhieb, N., Abdulrashid, I., Ghazzai, H., & Massoud, Y. (2023). Optimized drug regimen and chemotherapy scheduling for cancer treatment using swarm intelligence. Annals of Operations Research, 320(2), 757-770. [CrossRef]

- Szűcs, T. D., Puskás, M., Drexler, D. A., & Kovács, L. (2023, May). Model predictive fuzzy control in chemotherapy optimization. In 2023 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI) (pp. 103-108). IEEE.

- Ajayi, T., Hosseinian, S., Schaefer, A. J., & Fuller, C. D. (2024). Combination chemotherapy optimization with discrete dosing. INFORMS Journal on Computing, 36(2), 434-455. [CrossRef]

- Samy, P. G., Kanesan, J., Badruddin, I. A., Kamangar, S., & Ahammad, N. A. (2024). Optimizing chemotherapy treatment outcomes using metaheuristic optimization algorithms: A case study. Bio-Medical Materials and Engineering, (Preprint), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Yee, L. M., McShane, L. M., Freidlin, B., Mooney, M. M., & Korn, E. L. (2019). Biostatistical and logistical considerations in the development of basket and umbrella clinical trials. The Cancer Journal, 25(4), 254-263. [CrossRef]

- D’Arrigo, G., El Hafeez, S. A., Mezzatesta, S., Abelardo, D., Provenzano, F. P., Vilasi, A., ... & Tripepi, G. (2024). Common mistakes in biostatistics. Clinical Kidney Journal, 17(7), sfae197. [CrossRef]

- Ho, A. Y., Barker, C. A., Arnold, B. B., Powell, S. N., Hu, Z. I., Gucalp, A., ... & McArthur, H. L. (2020). A phase 2 clinical trial assessing the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab and radiotherapy in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer, 126(4), 850-860. [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, M., Moshier, E. L., Özbek, U., & Parsons, R. (2018). Ten essential practices for developing or reforming a biostatistics core for a NCI designated cancer center. JNCI Cancer Spectrum, 2(1), pky010. [CrossRef]

- Cook, R. J., & Moodie, E. E. (2024). A retrospective and prospective study of biostatistics in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Hofman, M. S., Murphy, D. G., Williams, S. G., Nzenza, T., Herschtal, A., Lourenco, R. D. A., ... & Lawrentschuk, N. (2018). A prospective randomized multicentre study of the impact of gallium-68 prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) PET/CT imaging for staging high-risk prostate cancer prior to curative-intent surgery or radiotherapy (proPSMA study): clinical trial protocol. BJU international, 122(5), 783-793. [CrossRef]

- Denkert, C., Seither, F., Schneeweiss, A., Link, T., Blohmer, J. U., Just, M., ... & Loibl, S. (2021). Clinical and molecular characteristics of HER2-low-positive breast cancer: pooled analysis of individual patient data from four prospective, neoadjuvant clinical trials. The Lancet Oncology, 22(8), 1151-1161. [CrossRef]

- Sedrak, M. S., Li, D., Walter, L. C., Mustian, K., High, K. P., Canin, B., ... & Sun, C. L. (2020). Cores for geriatric oncology infrastructure in the Cancer and Aging Research Group: Biostatistics, epidemiology, and research design (the analytics core). Journal of geriatric oncology, 11(2), 355-358. [CrossRef]

- Lin, R., Yin, G., & Shi, H. (2023). Bayesian adaptive model selection design for optimal biological dose finding in phase I/II clinical trials. Biostatistics, 24(2), 277-294. [CrossRef]

- Buteau, J. P., Moon, D., Fahey, M. T., Roberts, M. J., Thompson, J., Murphy, D. G., ... & Emmett, L. (2024). Clinical trial protocol for PRIMARY2: a multicentre, phase 3, randomised controlled trial investigating the additive diagnostic value of [68Ga] Ga-PSMA-11 positron emission tomography/computed tomography in men with negative or equivocal multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer. European Urology Oncology, 7(3), 544-552. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Jayaraj, S., Ludmir, E., & Roberts, K. (2024, January). Text classification of cancer clinical trial eligibility criteria. In AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings (Vol. 2023, p. 1304).

- Rodin, G., Lo, C., Rydall, A., Shnall, J., Malfitano, C., Chiu, A., ... & Hales, S. (2018). Managing cancer and living meaningfully (CALM): a randomized controlled trial of a psychological intervention for patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 36(23), 2422-2432. [CrossRef]

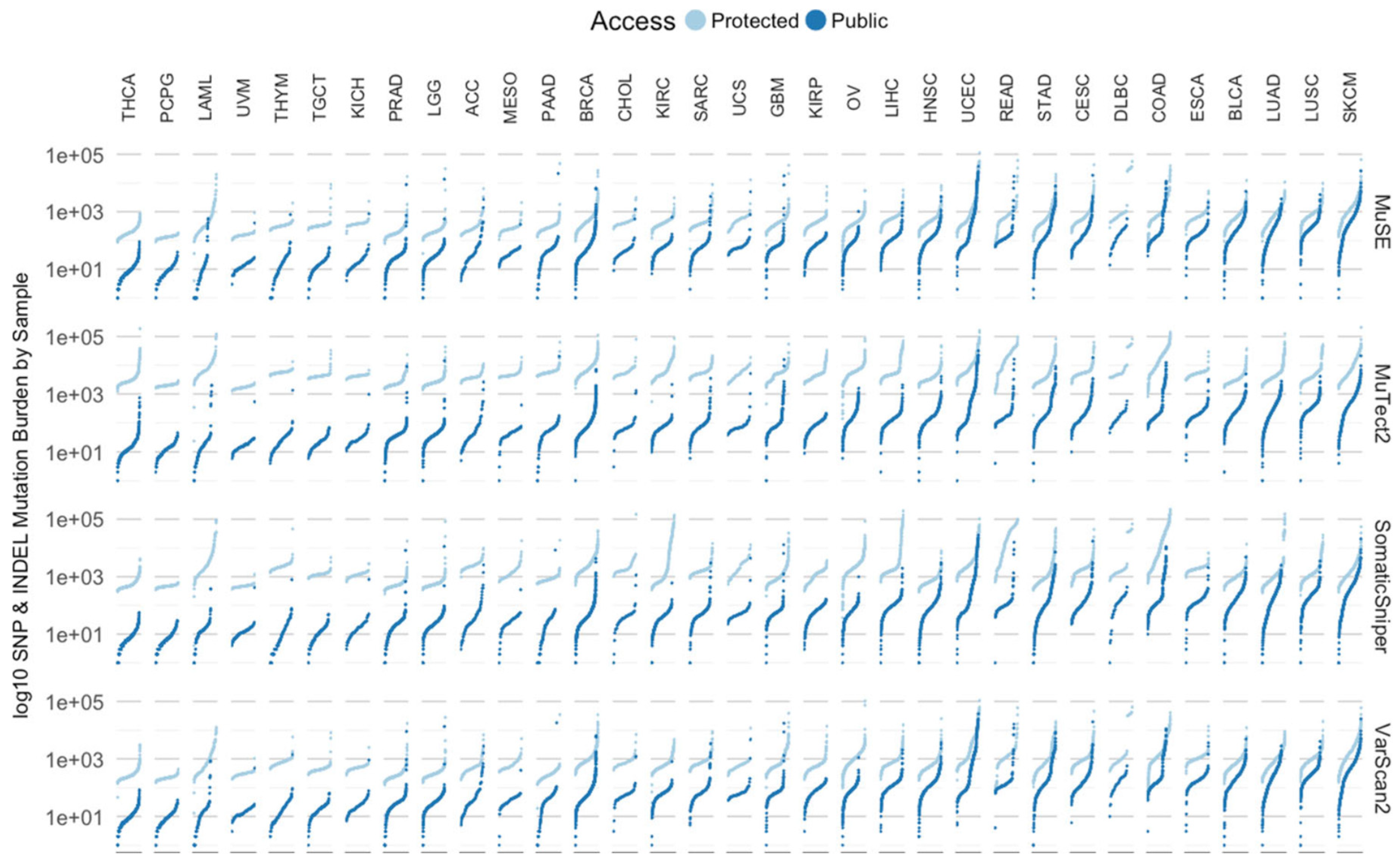

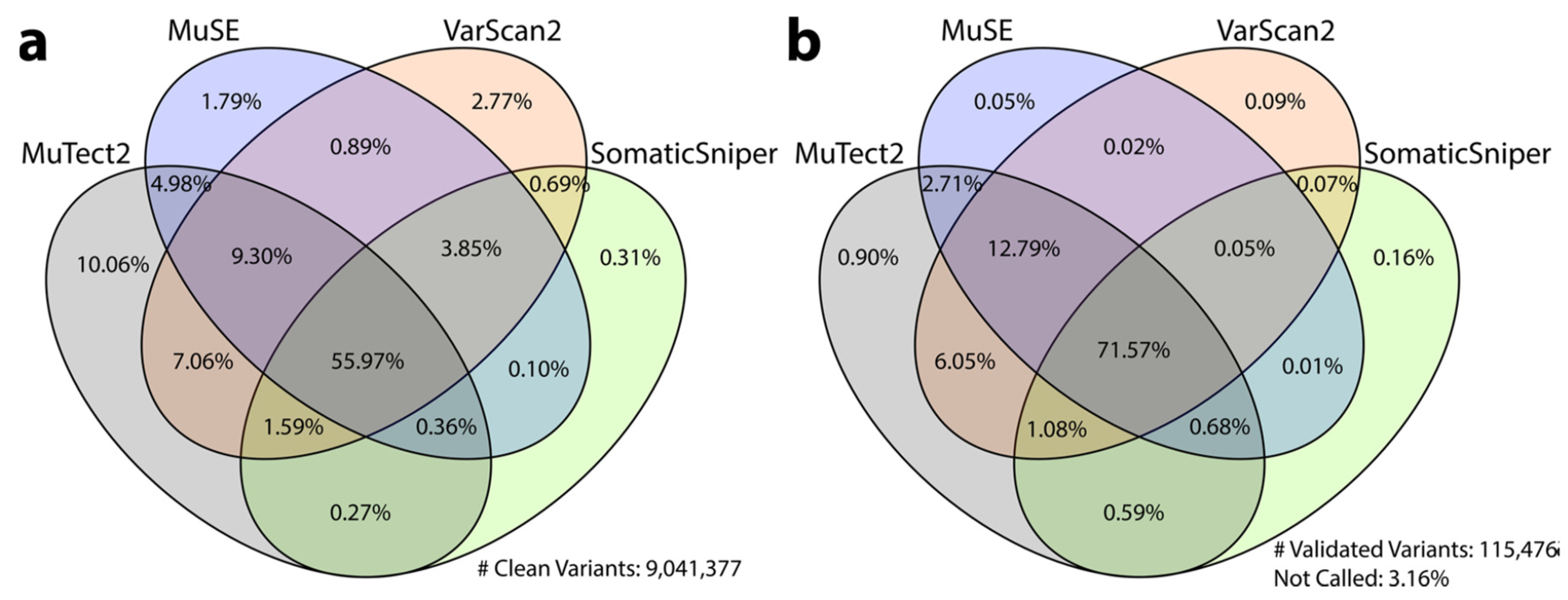

- Zhang, Z., Hernandez, K., Savage, J., Li, S., Miller, D., Agrawal, S., ... & Grossman, R. L. (2021). Uniform genomic data analysis in the NCI Genomic Data Commons. Nature communications, 12(1), 1226. [CrossRef]

- Schatz, M. C., Philippakis, A. A., Afgan, E., Banks, E., Carey, V. J., Carroll, R. J., ... & Walker, J. (2022). Inverting the model of genomics data sharing with the NHGRI Genomic Data Science Analysis, Visualization, and Informatics Lab-space. Cell Genomics, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., Wang, M., Xu, S., Huang, Z., & Grant, P. W. (2021). The unsupervised feature selection algorithms based on standard deviation and cosine similarity for genomic data analysis. Frontiers in Genetics, 12, 684100. [CrossRef]

- Kolisnik, T., Keshavarz-Rahaghi, F., Purcell, R. V., Smith, A. N., & Silander, O. K. (2024). pyRforest: A comprehensive R package for genomic data analysis featuring scikit-learn Random Forests in R. Briefings in Functional Genomics, elae038. [CrossRef]

- Dervishi, L., Wang, X., Li, W., Halimi, A., Vaidya, J., Jiang, X., & Ayday, E. (2023, April). Facilitating federated genomic data analysis by identifying record correlations while ensuring privacy. In AMIA annual symposium proceedings (Vol. 2022, p. 395).

- Liu, K., Newbury, P. A., Glicksberg, B. S., Zeng, W. Z., Paithankar, S., Andrechek, E. R., & Chen, B. (2019). Evaluating cell lines as models for metastatic breast cancer through integrative analysis of genomic data. Nature communications, 10(1), 2138. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L., Laiouar-Pedari, S., Kuntz, S., Krieghoff-Henning, E., Hekler, A., Kather, J. N., ... & Brinker, T. J. (2022). Integration of deep learning-based image analysis and genomic data in cancer pathology: A systematic review. European journal of cancer, 160, 80-91. [CrossRef]

- Rehan, H. (2023). AI-Powered Genomic Analysis in the Cloud: Enhancing Precision Medicine and Ensuring Data Security in Biomedical Research. Journal of Deep Learning in Genomic Data Analysis, 3(1), 37-71.

- Piñero, J., Saüch, J., Sanz, F., & Furlong, L. I. (2021). The DisGeNET cytoscape app: Exploring and visualizing disease genomics data. Computational and structural biotechnology journal, 19, 2960-2967. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D., Xu, L., Tao, W., & Li, Y. (2024, August). Research on genome data recognition and analysis based on Louvain algorithm. In Fourth International Conference on Biomedicine and Bioinformatics Engineering (ICBBE 2024) (Vol. 13252, pp. 233-238). SPIE.

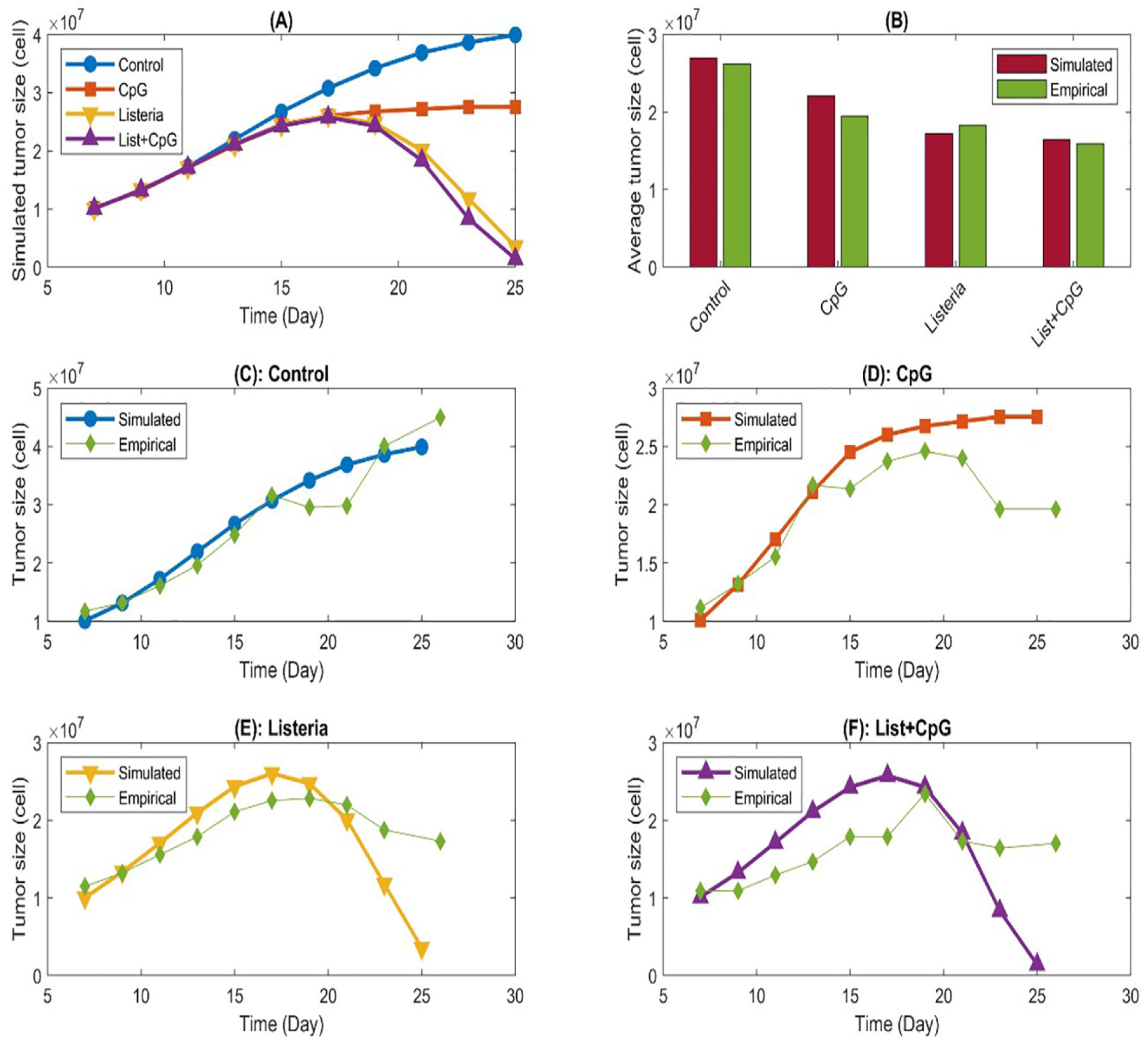

- Jarrett, A. M., Song, P. N., Reeves, K., Lima, E. A., Larimer, B., Yankeelov, T. E., & Sorace, A. G. (2023). Investigating tumor-host response dynamics in preclinical immunotherapy experiments using a stepwise mathematical modeling strategy. Mathematical Biosciences, 366, 109106. [CrossRef]

- Zand, B., Arab, S., Kheshtchin, N., Arabameri, A., Ashourpour, M., Asemani, D., ... & Hadjati, J. (2022). Identification of the optimal pattern of the injection and dosage of DC immunotherapy using the mathematical models based on ordinary differential equations. Iranian Journal of Immunology, 19(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

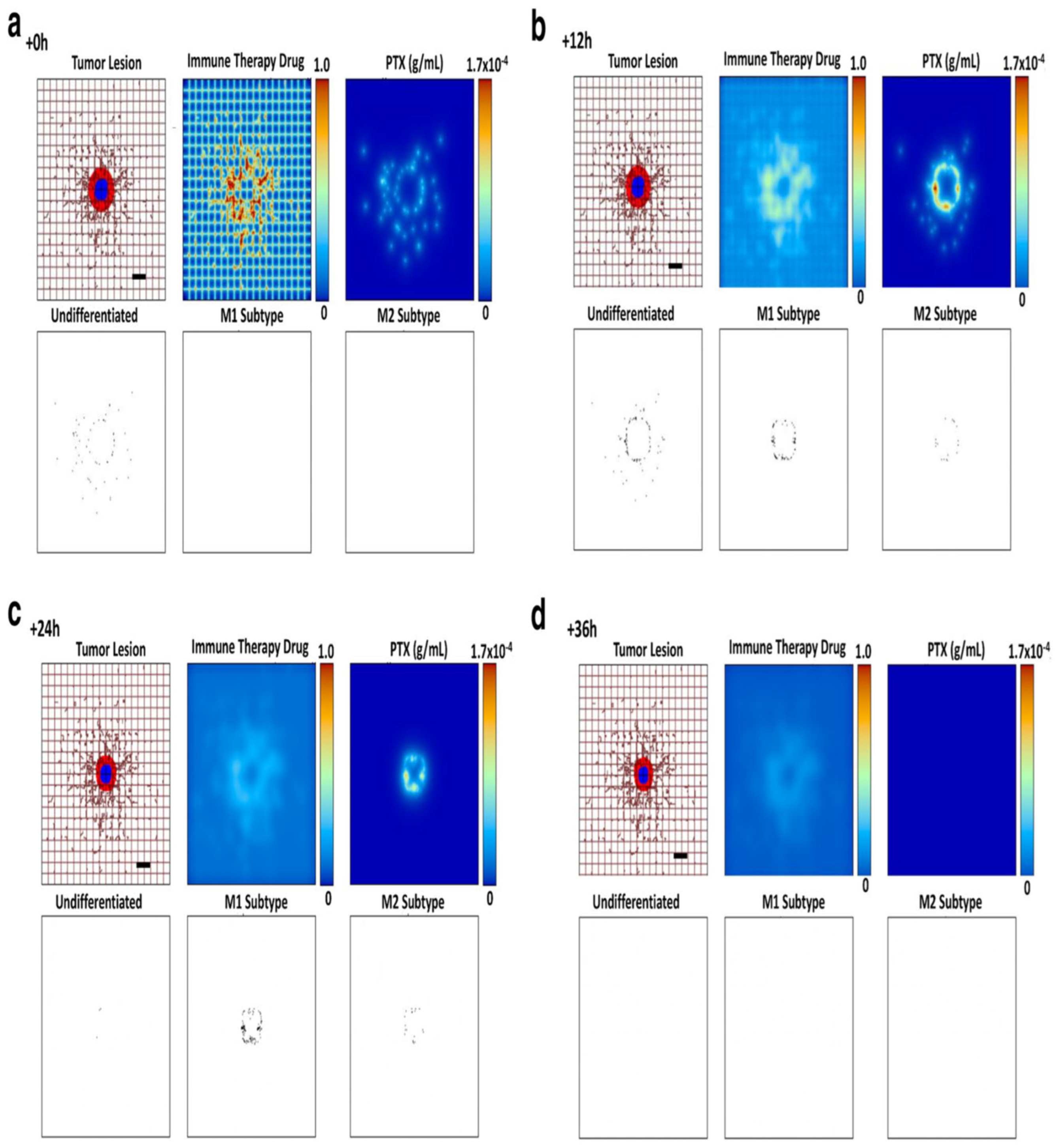

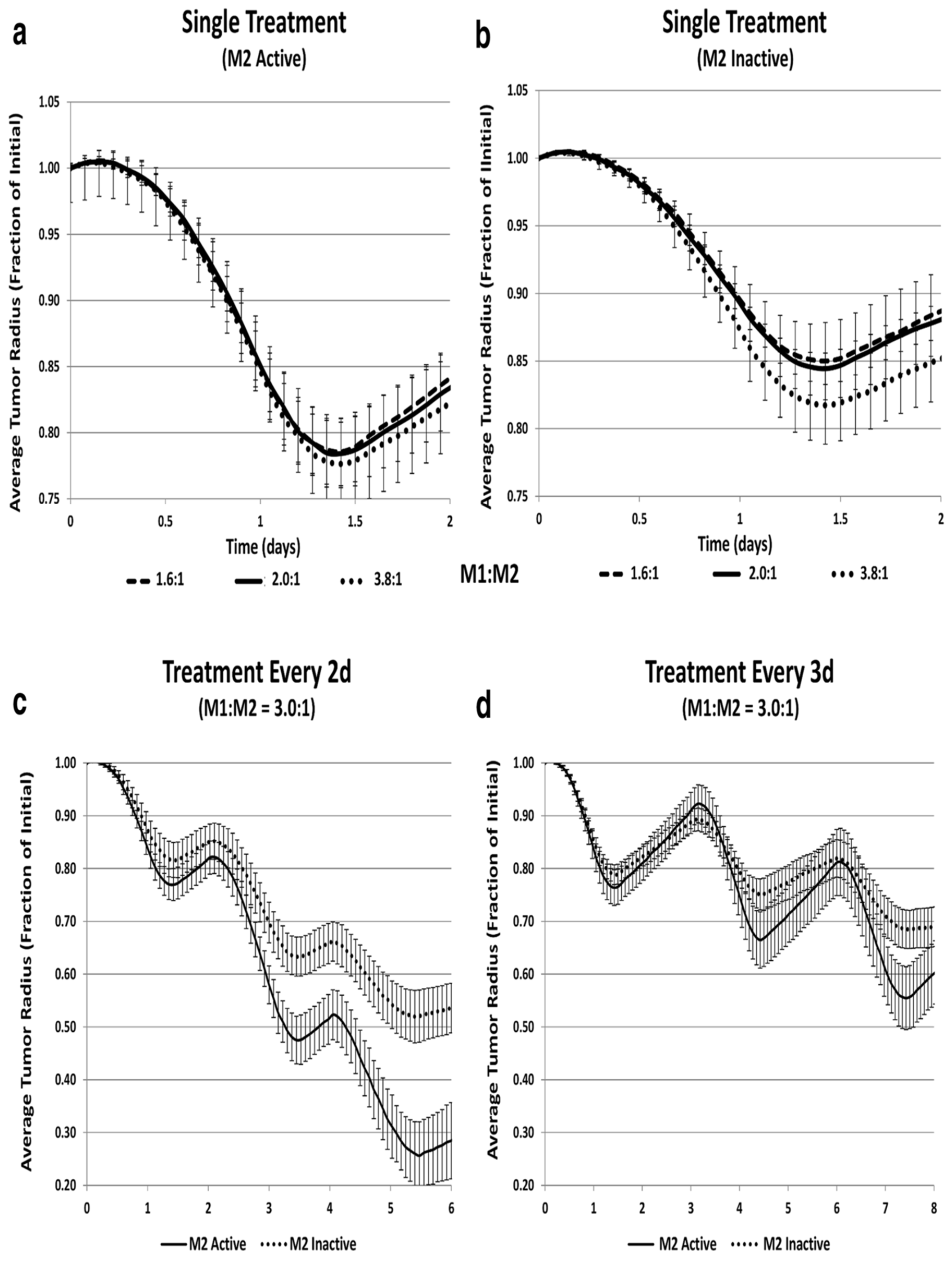

- Leonard, F., Curtis, L. T., Hamed, A. R., Zhang, C., Chau, E., Sieving, D., ... & Frieboes, H. B. (2020). Nonlinear response to cancer nanotherapy due to macrophage interactions revealed by mathematical modeling and evaluated in a murine model via CRISPR-modulated macrophage polarization. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy, 69, 731-744. [CrossRef]

- Atsou, K. K. (2020). Mathematical modeling of tumor-immune system interactions: equilibrium and escape phase (Doctoral dissertation, Universite cote d’Azur).

- Khalili, P., & Vatankhah, R. (2023). Studying the importance of regulatory T cells in chemoimmunotherapy mathematical modeling and proposing new approaches for developing a mathematical dynamic of cancer. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 563, 111437. [CrossRef]

- Nave, O., Elbaz, M., & Bunimovich-Mendrazitsky, S. (2020). Analysis of a breast cancer mathematical model by a new method to find an optimal protocol for HER2-positive cancer. Biosystems, 197, 104191. [CrossRef]

- Ghiyabi, E., Arabameri, A., & Charmi, M. (2024). Mathematical modeling of hypoxia and adenosine to explore tumor escape mechanisms in DC-based immunotherapy. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 11387. [CrossRef]

- Dehingia, K., Sarmah, H. K., Alharbi, Y., & Hosseini, K. (2021). Mathematical analysis of a cancer model with time-delay in tumor-immune interaction and stimulation processes. Advances in Difference Equations, 2021, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, S., Shafiekhani, S., Allahverdy, A., Jamali, A., Kheshtchin, N., Ajami, M., ... & Jafari, A. H. (2022). Agent-based modeling of tumor and immune system interactions in combinational therapy with low-dose 5-fluorouracil and dendritic cell vaccine in melanoma B16F10. Iranian Journal of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. [CrossRef]

- Dhar, B., Gupta, P. K., & Yildirim, A. (2022). Dynamical behaviour of a tumour-immune model focusing on the dosage of targeted chemotherapeutic drug. International Journal of Computer Mathematics, 99(12), 2568-2582. [CrossRef]

- Cotra, S. (2024). Systems biology models for cancer immunotherapy.

- Przedborski, M., Smalley, M., Thiyagarajan, S., Goldman, A., & Kohandel, M. (2021). Systems biology informed neural networks (SBINN) predict response and novel combinations for PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Communications Biology, 4(1), 877. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Chen, Y., Li, M., Cao, S., Wang, N., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2023). A PDA-Functionalized 3D Lung Scaffold Bioplatform to Construct Complicated Breast Tumor Microenvironment for Anticancer Drug Screening and Immunotherapy. Advanced Science, 10(26), 2302855. [CrossRef]

- Sloan, A., Song, Y., Gail, M. H., Betensky, R., Rosner, B., Ziegler, R. G., ... & Wang, M. (2019). Design and analysis considerations for combining data from multiple biomarker studies. Statistics in medicine, 38(8), 1303-1320. [CrossRef]

- Ou, F. S., Michiels, S., Shyr, Y., Adjei, A. A., & Oberg, A. L. (2021). Biomarker discovery and validation: statistical considerations. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 16(4), 537-545. [CrossRef]

- Terkelsen, T., Krogh, A., & Papaleo, E. (2020). CAncer bioMarker Prediction Pipeline (CAMPP)—A standardized framework for the analysis of quantitative biological data. PLoS computational biology, 16(3), e1007665. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z., & Pepe, M. S. (2020). Adding rigor to biomarker evaluations—EDRN experience. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 29(12), 2575-2582. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q., Zhang, F., Xu, L., Yue, L., Kon, O. L., Zhu, Y., & Guo, T. (2021). High-throughput proteomics and AI for cancer biomarker discovery. Advanced drug delivery reviews, 176, 113844. [CrossRef]

- Shieh, K. R., Huang, A., & Xu, Y. (2021). Response to immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment in advanced cervical cancer and biomarker study. Frontiers in Medicine, 8, 669587. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D. F. (2021). Defining clinical utility of tumor biomarker tests: a clinician’s viewpoint. Journal of clinical oncology, 39(3), 238-248. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D. F., Sauerbrei, W., & McShane, L. M. (2023). REMARK guidelines for tumour biomarker study reporting: A remarkable history. British Journal of Cancer, 128(3), 443-445. [CrossRef]

- Nakayasu, E. S., Gritsenko, M., Piehowski, P. D., Gao, Y., Orton, D. J., Schepmoes, A. A., ... & Metz, T. O. (2021). Tutorial: best practices and considerations for mass-spectrometry-based protein biomarker discovery and validation. Nature Protocols, 16(8), 3737-3760. [CrossRef]

- Chang, J., Lin, G., Ye, M., Tong, D., Zhao, J., Zhu, D., ... & Li, W. (2019). Decreased mean platelet volume predicts poor prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with first-line chemotherapy: results from mCRC biomarker study. BMC cancer, 19, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Cheng, B., Xie, H., Zhan, C., Li, S., & Bai, P. (2022). Bladder cancer biomarker screening based on non-targeted urine metabolomics. International Urology and Nephrology, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Hristova, V. A., & Chan, D. W. (2019). Cancer biomarker discovery and translation: proteomics and beyond. Expert review of proteomics, 16(2), 93-103. [CrossRef]

- Elkahwagy, D. M. A. S., Kiriacos, C. J., & Mansour, M. (2024). Logistic regression and other statistical tools in diagnostic biomarker studies. Clinical and Translational Oncology, 26(9), 2172-2180. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Yang, Y., Xu, J., Bai, W., Ren, X., & Wu, H. (2018). CircRNAs as biomarkers of cancer: a meta-analysis. BMC cancer, 18, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Bratman, S. V., Yang, S. C., Iafolla, M. A., Liu, Z., Hansen, A. R., Bedard, P. L., ... & Pugh, T. J. (2020). Personalized circulating tumor DNA analysis as a predictive biomarker in solid tumor patients treated with pembrolizumab. Nature Cancer, 1(9), 873-881. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Rong, Z., Wang, G., Hou, Y., Yang, F., & Qiu, M. (2023). Cancer metabolites: promising biomarkers for cancer liquid biopsy. Biomarker Research, 11(1), 66. [CrossRef]

- Bartha, Á., & Győrffy, B. (2021). TNMplot. com: a web tool for the comparison of gene expression in normal, tumor and metastatic tissues. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(5), 2622. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y., Meng, W. Y., Li, R. Z., Wang, Y. W., Qian, X., Chan, C., ... & Leung, E. L. H. (2021). Early lung cancer diagnostic biomarker discovery by machine learning methods. Translational oncology, 14(1), 100907. [CrossRef]

- Kumbrink, J., Bohlmann, L., Mamlouk, S., Redmer, T., Peilstöcker, D., Li, P., ... & Holch, J. W. (2022). Serial analysis of gene mutations and gene expression during first-line chemotherapy against metastatic colorectal cancer: identification of potentially actionable targets within the multicenter prospective biomarker study reveal. Cancers, 14(15), 3631. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Xu, H., Liu, R., Gao, P., Yang, X., Jin, W., ... & Li, Q. (2019). A novel strategy for targeted lipidomics based on LC-tandem-MS parameters prediction, quantification, and multiple statistical data mining: evaluation of lysophosphatidylcholines as potential cancer biomarkers. Analytical chemistry, 91(5), 3389-3396. [CrossRef]

- Acs, B., Fredriksson, I., Rönnlund, C., Hagerling, C., Ehinger, A., Kovács, A., ... & Hartman, J. (2021). Variability in breast cancer biomarker assessment and the effect on oncological treatment decisions: a nationwide 5-year population-based study. Cancers, 13(5), 1166. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).