Submitted:

07 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

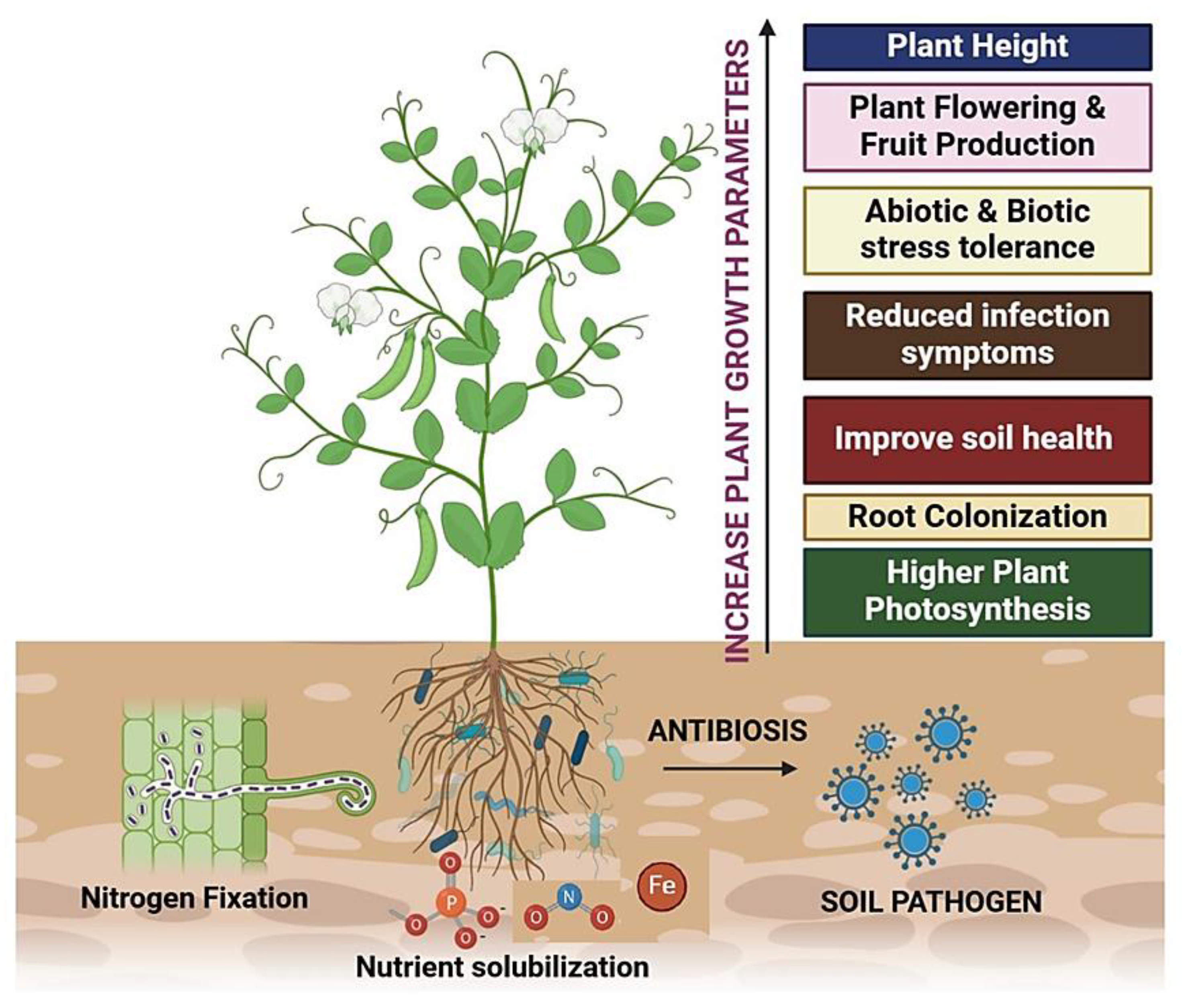

2. Microbial Interactions with Plants Roots and Their Beneficial Roles

3. Rhizomicrobiome Interaction with Secondary Metabolite, Signalling Proteins and Their Relationship in Plants

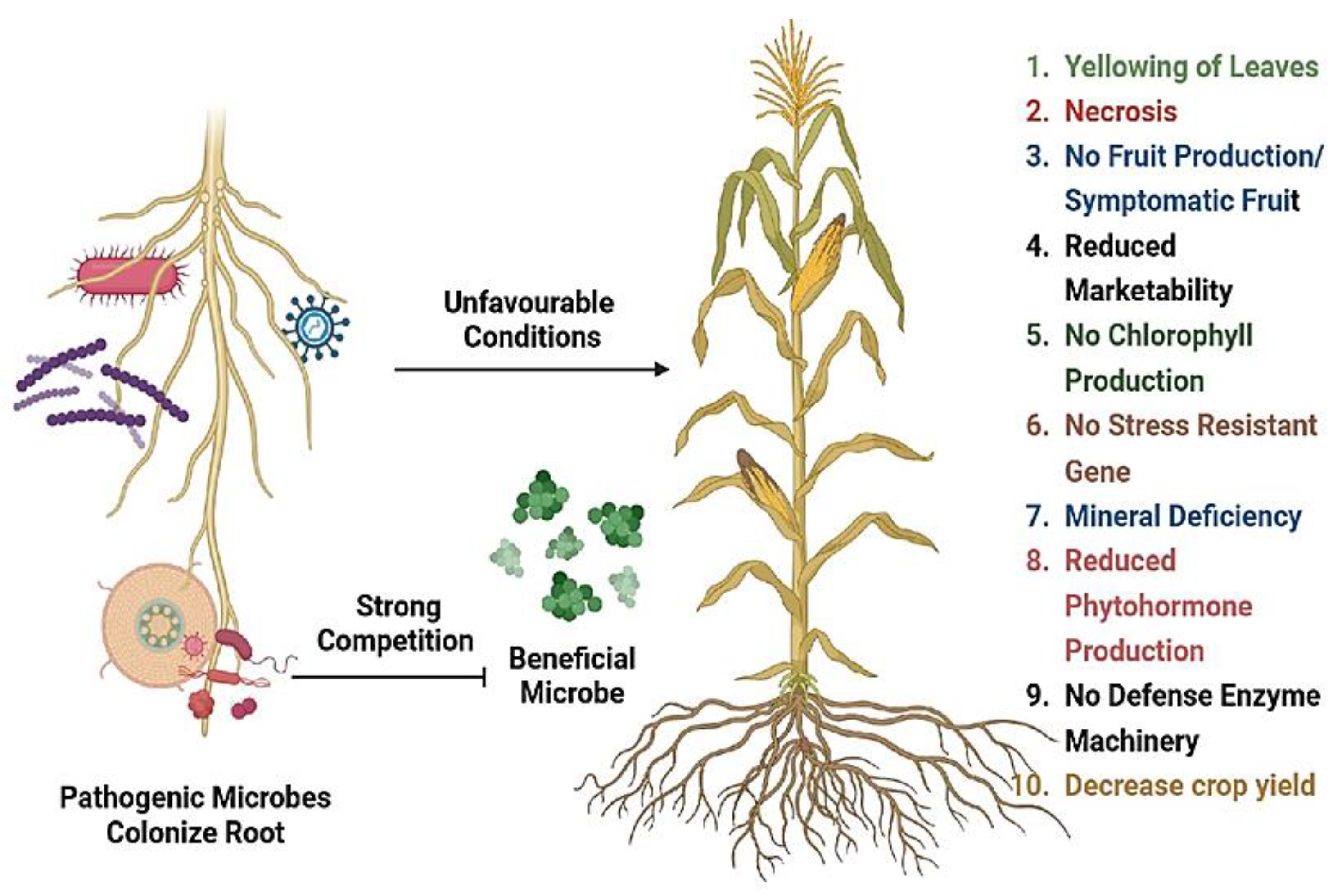

4. Saprophytic Microbial Interaction Can Be Beneficial or Parasitic in Rhizosphere

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase |

| PGPR | Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria |

| PGPF | Plant Growth Promoting Fungi |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| POX/POD | Peroxidase |

| PAL | Phenylalanine lyase |

| PPO | Polyphenol Peroxidase |

| N, P, K | Nitrogen, Phosphorous, Potassium |

| ABA | Abscissic acid |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| AHLs | Amino homoserine lactones |

| HCN | Hydrogen cyanide |

| CAT | Catalas |

| GA- | Gibberellic acid |

| PR | Pathogenesis related proteins |

| ET | Ethylene |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| APX | Ascorbate peroxidase |

| GR | Glutathione reductase |

| GST | Glutathione-S-transferase |

| GPX | Gaucol peroxidase |

References

- Nadarajah, K.K. Rhizosphere Interactions: Life Below Ground. In Plant-Microbe Interaction: An Approach to Sustainable Agriculture; Choudhary, D.K., Varma, A., Tuteja, N., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhaj, K.; Cano, L.M.; Prince, D.C.; Kemen, A.; Yoshida, K.; Dagdas, Y.F.; Etherington, G.J.; Schoonbeek, H.J.; Van Esse, H.P.; Jones, J.D.; Kamoun, S. Arabidopsis late blight: Infection of a nonhost plant by Albugo laibachii enables full colonization by Phytophthora infestans. Cellular Microbiology 2017, 19, 12628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Carmen Orozco-Mosqueda M, Fadiji AE, Babalola OO, Glick BR, Santoyo G, Rhizobiome engineering: Unveiling complex rhizosphere interactions to enhance plant growth and health. Microbiological Research 2022, 263, 127137. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, P.; Ravishankar, R. Quorum quenching activity in cell-free-lysate of endophytic bacteria isolated from Pterocarpus santalinus Linn and its effect on quorum sensing regulated biofilm in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. Microbiological Research 2014, 169, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.P.; Grover, M.; Chourasiya, D.; Bharti, A.; Agnihotri, R.; Maheshwari, H.S.; Pareek, A.; Buyer, J.S.; Sharma, S.K.; Schutz, L.; et al. Deciphering the role of trehalose in tripartite symbiosis among rhizobia, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, and legumes for enhancing abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Baumgarten, A.; May, G. Effects of host plant environment and Ustilago maydis infection on the fungal endophyte community of maize (Zea mays). New Phytology 2008, 178, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Jha, D.K. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): Emergence in agriculture. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2011, 28, 1327–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naziya, B.; Murali, M.; Amruthesh, K.N. Plant growth-promoting fungi (PGPF) instigate plant growth and induce disease resistance in Capsicum annuum L. upon infection with Colletotrichum capsici (Syd. ) Butler & Bisby. Biomolecules 2019, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omomowo, I.O.; Adedayo, A.A.; Omomowo, O.I. Biocontrol Potential of Rhizospheric Fungi from Moringa oleifera, their Phytochemicals and Secondary Metabolite Assessment Against Spoilage Fungi of Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis). Asian Journal of Applied Science 2020, 8, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Medina, A.; Del Mar Alguacil, M.; Pascual, J.A.; Van Wees, S.C. Phytohormone profiles induced by Trichoderma isolates correspond with their biocontrol and plant growth-promoting activity on melon plants. Journal of chemical ecology 2014, 40, 804–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adedayo, A.A.; Babalola, O.O. Fungi that promote plant growth in the rhizosphere boost crop growth. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoni, C.; Kia, D.; Vandrovcova, J.; Hardy, J.; Wood, N.; Lewis, P.; Ferrari, R. Genome, transcriptome and proteome: The rise of omics data and their integration in biomedical sciences. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2018, 19, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu A, Chen S, Wang M, Liu D, Chang R, Wang Z, Lin X, Bai B, Ahammed GJ, Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus alleviates chilling stress by boosting redox poise and antioxidant potential of tomato seedlings. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2016, 35, 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Bakr, J.; Daood, H.; Pek, Z.; Helyes, L.; Posta, K. Yield and quality of mycorrhized processing tomato under water scarcity. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 2016, 15, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halifu, S.; Deng, X.; Song, X.; Song, R. Effects of two Trichoderma strains on plant growth, rhizosphere soil nutrients, and fungal community of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica annual seedlings. Forests 2019, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Marina, M.A.; Silva-Flores, M.A.; Cervantes-Badillo, M.G.; Rosales-Saavedra, M.T.; Islas-Osuna, M.A.; Casas-Flores, S. The plant growth promoting fungus Aspergillus ustus promotes growth and induces resistance against different lifestyle pathogens in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2011, 21, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, R.; Kang, S.; Baek, I.; Lee, I. Characterization of plant growth promoting traits of Penicillium species against the effects of high soil salinity and root disease. Journal of Plant Interactions. 2014, 9, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan AL, Shinwari ZK, Kim YH, Waqas M, Hamayun M, Kamran M; et al. Role of endophyte Chaetomium globosum LK4 in growth of Capsicum annum by production of gibberellins and indole acetic acid. Pakistan Journal of Botany 2012, 44, 1601–1607. [Google Scholar]

- lhamed, M.F.A.; Shebany, Y.M. Endophytic Chaetomium globosum enhances maize seedling copper stress tolerance. Plant Biology 2012, 14, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujanovic, V.; Goh, Y.K. qPCR quantification of Sphaerodes mycoparasitica biotrophic mycoparasite interaction with Fusarium graminearum: In vitro and in planta assays. Archives of Microbiology 2012, 194, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogaiah, S.; Abdelrahman, M.; Tran, L.S.P.; Shin-ichi, I. Characterization of rhizosphere fungi that mediate resistance in tomato against bacterial wilt disease. Journal of Experimental Botany 2013, 64, 3829–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzoma, K.; Inoue, M.; Andry, H.; Fujimaki, H.; Zahoor, A.; Nishihara, E. Effect of cow manure biochar on maize productivity under sandy soil condition. Soil Use Management 2011, 27, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noorden, G.E.; Kerim, T.; Goffard, N.; Wiblin, R.; Pellerone, F.I.; Rolfe, B.G.; Mathesius, U. Overlap of proteome changes in Medicago truncatula in response to auxin and Sinorhizobium meliloti. Plant Physiology 2007, 144, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, K.; Krajinski, F.; Hohnjec, N.; Firnhaber, C.; Puhler, A.; Perlick, A.; Kuster, H. Transcriptiome profiling in root-nodules and arbuscualr mycorrhiza identifies a collection of novel genes induced during Medicago truncatula root endosymbioses. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2004, 17, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulekar, M.H. Rhizosphere bioremediation of pesticides by microbial consortium and potential microorganism. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2014, 235–248. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad P, Hashem A, Abd-Allah EF, Alqarawi AA, John R, Egamberdieva D et al. Role of Trichoderma harzianum in mitigating NaCl stress in Indian mustard (Brassica juncea L.) through antioxidative defense system. Frontiers in Plant Science 2015, 6, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, K.; Couch, H.B. Effects of Penicillium simplicissimum on growth, chemical composition, and root exudation of axenically grown marigolds. Phytopathology 1971, 62, 669. [Google Scholar]

- Villa-Rodriguez, E.; Moreno-Ulloa, A.; Castro-Longoria, E.; Parra-Cota, F.I.; de los SantosVillalobos, S. Integrated omics approaches for deciphering antifungal metabolites produced by a novel Bacillus species, B. cabrialesii TE3T, against the spot blotch disease of wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum). Microbiological Research 2021, 251, 126826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monchgesang, S.; Strehmel, N.; Schmidt, S.; Westphal, L.; Taruttis, F.; Muller, E.; Herklotz, S.; Neumann, S.; Scheel, D. Natural variation of root exudates in Arabidopsis thaliana-linking metabolomic and genomic data. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala-Gonzalez, E.A.; Escudero, N.; Lopez-Moya, F.; Aranda-Martinez, A.; Exposito, A.; Ricano-Rodriguez, J.; Naranjo-Ortiz, M.A.; Ramirez-Lepe, M.; Lopez-Llorca, L.V. Some isolates of the nematophagous fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia promote root growth and reduce flowering time of tomato. Annals of Applied Biology 2015, 166, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihorimbere, V.; Cawoy, H.; Seyer, A.; Brunelle, A.; Thonart, P.; Ongena, M. Impact of rhizosphere factors on cyclic lipopeptide signature from the plant beneficial strain Bacillus amyloliquefaciens S499. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2012, 79, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, I.A.; Chen, H.; Chen, J.; Chang, M.; Li, M.; Liu, F.; Fu, Z.Q. Novel salicylic acid analogs induce a potent defense response in Arabidopsis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehmel, N.; Bottcher, C.; Schmidt, S.; Scheel, D. Profiling of secondary metabolites in root exudates of Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 2014, 108, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyakumachi, M. Plant-growth promoting fungi from turf grass rhizosphere with potential for disease suppression. Soil Microorganisms 1994, 44, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, G.E.; Petzoldt, R.; Comis, A.; Chen, J. Interactions between Trichoderma harzianum strain T22 and maize inbred line Mo17 and effects of this interaction on diseases caused by Pythium ultimum and Colletotrichum graminicola. Phytopathology 2004, 94, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagiwa, Y.; Toyoda, K.; Inagaki, Y.; Ichinose, Y.; Hyakumachi, M.; Shiraishi, T. Talaromyces wortmannii FS2 emits β-caryophyllene, which promotes plant growth and induces resistance. Journal of General Plant Pathology 2011, 77, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waweru, B.; Turoop, L.; Kahangi, E.; Coyne, D.; Dubois, T. Non-pathogenic Fusarium oxysporum endophytes provide field control of nematodes, improving yield of banana (Musa sp.). Biological Control 2014, 74, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Huang, H.; Zhu, J.; Fang, Z.; Sun, Q.; Bao, S. A new nematicidal compound produced by Streptomyces albogriseolus HA10002. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2013, 103, 1107–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Tena, A.; Rincon-Enríquez, G.; Lopez-Perez, L.; Quinones-Aguilar, E.E. Effect of mycorrhizae and actinomycetes on growth and bioprotection of Capsicum annuum L. against Phytophthora capsici. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2017, 54, 4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, N.; He, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Huang, L.; Yan, X. Expression and characterization of a novel chitinase with antifungal activity from a rare actinomycete, Saccharothrix yanglingensis Hhs. 015. Protein Expression and Purification 2018, 143, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Carvajal, L.; Orduz, S.; Bissett, J. Growth stimulation in bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ) by Trichoderma. Biological Control 2009, 51, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inderiati, S.; Franco, C.M. Isolation and identification of endophytic actinomycetes and their antifungal activity. Journal of Tropical Biodiversity and Biotechnology 2008, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra-Mohana, N.; Narendra-Kumar, H.K.; Mahadevakumar, S.; Sowmya, R.; Sridhar, K.R.; Satish, S. First Report of Aspergillus versicolor Associated with Fruit Rot Disease of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) from India. Plant Disease 2022, 106, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, M.; Kumar, V.; Saharan, K.; Srivastava, R.; Sharma, A.K.; Prakash, A.; Sahai, V.; Bisaria, V.S. Application of inorganic carrier-based formulations of fluorescent pseudomonads and Piriformospora indica on tomato plants and evaluation of their efficacy. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2011, 111, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palma, M.; Scotti, R.; D’Agostino, N.; Zaccardelli, M.; Tucci, M. Phyto-Friendly Soil Bacteria and Fungi Provide Beneficial Outcomes in the Host Plant by Differently Modulating Its Responses through (In)Direct Mechanisms. Plants 2022, 11, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshaghi Gorgi, O.; Fallah, H.; Niknejad, Y.; Barari Tari, D. Effect of Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and mycorrhizal fungi inoculations on essential oil in Melissa officinalis L. under drought stress. Biologia 2022, 77, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Mahanta, M.; Singh, S.B.; Thakuria, D.; Deb, L.; Kumari, A.; Upamanya, G.K.; Boruah, S.; Dey, U.; Mishra, A.K.; Vanlaltani, L. Molecular interaction between plants and Trichoderma species against soil-borne plant pathogens. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1145715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldredge, S.D.; Geary, B.; Jensen, S.L. Seed isolates of Alternaria and Aspergillus fungi increase germination of Astragalus utahensis. Native Plants Journal 2016, 17, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedidia, I.; Srivastva, A.K.; Kapulnik, Y.; Chet, I. Effect of Trichoderma harzianum on microelement concentrations and increased growth of cucumber plants. Plant and Soil 2001, 235, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, H.; Vatandoost, S.; Aroiee, H.; Mazhabi, M. Would Trichoderma affect seed germination and seedling quality of two muskmelon cultivars, Khatooni and Qasri and increase their transplanting success? Journal of Biological and Environmental Sciences 2011, 5, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Muslim, A.; Horinouchi, H.; Hyakumachi, M. Biological control of Fusarium wilt of tomato with hypovirulent binucleate Rhizoctonia in greenhouse conditions. Mycoscience 2003, 44, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, O.P.; Babalola, O.O. Resident rhizosphere microbiome’s ecological dynamics and conservation: Towards achieving the envisioned Sustainable Development Goals, a review. International Soil and Water Conservation Research 2020, 9, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan AL, Hamayun M, Ahmad N, Waqas M, Kang SM, Kim YH; et al. Exophiala sp. LHL08 reprograms Cucumis sativus to higher growth under abiotic stresses. Physiologia Plantarum 2011, 143, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narsing Rao, M.P.; Lohmaneeratana, K.; Bunyoo, C.; Thamchaipenet, A. Actinobacteria–plant interactions in alleviating abiotic stress. Plants 2022, 11, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Vo, Q.A.T.; Barnett, S.J.; Ballard, R.A.; Zhu, Y.; Franco, C.M.M. Revealing the underlying mechanisms mediated by endophytic actinobacteria to enhance the rhizobia-chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) symbiosis. Plant Soil. 2022, 474, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Perez, J.M.; Gonzalez-Garcia, S.; Cobos, R.; Olego, M.; Ibanez, A.; Diez-Galan, A.; Garzon-Jimeno, E.; Coque, J.J.R. Use of endophytic and rhizosphere Actinobacteria from grapevine plants to reduce nursery fungal graft infections that lead to young grapevine decline. Applied Environmental Microbiology 2017, 83, e01564–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangseekaew, P.; Barros-Rodriguez, A.; Pathom-Aree, W.; Manzanera, M. Plant beneficial deep-sea Actinobacterium, Dermacoccus abyssi MT1.1(T) promote growth of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) under salinity stress. Biology 2022, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.; Mishra, I.; Arora, N.K. 2, 4-Diacetylphloroglucinol producing Pseudomonas fluorescens JM-1 for management of ear rot disease caused by Fusarium moniliforme in Zea mays L. Biotech 2022, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbort, C.J.; Hashimoto, M.; Inoue, H.; Niu, Y.; Guan, R.; Rombola, A.D.; et al. Root-secreted coumarins and the microbiota interact to improve iron nutrition in Arabidopsis. Cell Host & Microbe 2020, 28, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.L.; Ahmad, S.; Gordon-Weeks, R.T.J. Benzoxazinoids in root exudates of maize attract Pseudomonas putida to the rhizosphere. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; He, X.; Baer, M.; Beirinckx, S.; Tian, T.; Moya, Y.A.; et al. Plant flavones enrich rhizosphere Oxalobacteraceae to improve maize performance under nitrogen deprivation. Nature Plants 2021, 7, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringhurst, R.M.; Cardon, Z.G.; Gage, D.J. Galactosides in the rhizosphere: Utilization by Sinorhizobium meliloti and development of a biosensor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2001, 98, 4540–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Effects of different plant root exudates and their organic acid components on chemotaxis, biofilm formation and colonization by beneficial rhizosphere-associated bacterial strains. Plant Soil 2014, 374, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.W.; Li, X.W.; Wang, T.T.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, C.M.; Xing, K.; et al. Root exudates-driven rhizosphere recruitment of the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Bacillus flexus KLBMP 4941 and its growth-promoting effect on the coastal halophyte Limonium sinense under salt stress. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2020, 194, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hida, A.; Oku, S.; Miura, M.; Matsuda, H.; Tajima, T.; Kato, J. Characterization of methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) for amino acids in plant-growth-promoting rhizobacterium Pseudomonas protegens CHA0 and enhancement of amino acid chemotaxis by MCP genes overexpression. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 2020, 84, 1948–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, J.; Pascual, J.; Guillen, M.; Lopez-Martinez, A.; Carvajal, M. Influence of foliar Methyl-jasmonate biostimulation on exudation of glucosinolates and their effect on root pathogens of broccoli plants under salinity condition. Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 282, 110027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnawal, D.; Bharti, N.; Pandey, S.S.; Pandey, A.; Chanotiya, C.S.; Kalra, A. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria enhance wheat salt and drought stress tolerance by altering endogenous phytohormone levels and TaCTR1/TaDREB2 expression. Physiol. Plant 2017, 161, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonia, F.; Francia, E.; Morcia, C.; Ghizzoni, R.; Moulin, L.; Terzi, V.; Ronga, D. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Avoid Processing Tomato Leaf Damage during Chilling Stress. Agronomy 2019, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.Q. Effects of phosphate solubilization and phytohormone production of Trichoderma asperellum Q1 on promoting cucumber growth under salt stress. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2015, 14, 1588–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkasem, P.; Kurniawan, A.; Kao, T.C.; Chuang, H.W. A multifaceted rhizobacterium Bacillus licheniformis functions as a fungal antagonist and a promoter of plant growth and abiotic stress tolerance. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2018, 155, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabood, F.; Souleimanov, A.; Khan, W.; Smith, D. Jasmonates induce Nod factor production by Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2006, 44, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jin, W.; Liu, A.; Zhang, S.; Liu, D.; Wang, F.; Lin, X.; He, C. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) increase growth and metabolism in cucumber subjected to low temperature. Scientia Horticulturae 2013, 160, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yan, W.; Yang, L.; Gai, J.; Zhu, Y. Overexpression of StNHX1, a novel vacuolar Na+ /H+ antiporter gene from Solanum torvum, Enhances salt tolerance in transgenic vegetable Soybean. Horticulture Environment Biotechnology 2014, 55, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeendran, N.; Moot, D.J.; Jones, E.E.; Stewart, A. Inconsistent growth promotion of cabbage and lettuce from Trichoderma isolates. New Zealand Plant Protection 2000, 53, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Sultana, F. Application and mechanisms of plant growth promoting fungi (PGPF) for phytostimulation. Organic agriculture 2020, 1, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Akanda, A.M.; Prova, A.; Sultana, F.; Hossain, M.M. Growth promotion effect of Fusarium spp. PPF1 from Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon) rhizosphere on Indian spinach (Basella alba) seedlings are linked to root colonization. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 2014, 47, 2319–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Effects of different plant root exudates and their organic acid components on chemotaxis, biofilm formation and colonization by beneficial rhizosphere-associated bacterial strains. Plant Soil 2014, 374, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorty, A.M.; Meena, K.K.; Choudhary, K.; Bitla, U.M.; Minhas, P.S.; Krishnani, K.K. Effect of Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria Associated with Halophytic Weed (Psoralea corylifolia L.) on Germination and Seedling Growth of Wheat Under Saline Conditions. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2016, 180, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rin, S.; Mizuno, Y.; Shibata, Y.; Fushimi, M.; Katou, S.; Sato, I.; Chiba, S.; Kawakita, K.; Takemoto, D. EIN2-Mediated signaling is involved in pre-invasion defense in Nicotiana benthamiana against potato late blight pathogen, Phytophthora infestans. Plant Signaling Behaviour 2017, 12, e13007337474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjelloun, I.; Alami, I.T.; El Khadir, M.; Douira, A.; Udupa, S. Co-Inoculation of Mesorhizobium ciceri with either Bacillus sp. or Enterobacter aerogenes on Chickpea Improves Growth and Productivity in Phosphate-Deficient Soils in Dry Areas of a Mediterranean Region. Plants 2021, 10, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, W.; Chen, G.; Xu, H. Dynamics of Bacterial and Viral Communities in Paddy Soil with Irrigation and Urea Application. Viruses 2019, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.Y.; Narsing Rao, M.P.; Wang, H.F.; Fang, B.Z.; Liu, Y.H.; Li, L.; Xiao, M.; Li, W.J. Transcriptomic analysis of two endophytes involved in enhancing salt stress ability of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 686, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Chen, L.J.; Pan, S.Y.; Li, X.W.; Xu, M.J.; Zhang, C.M.; Xing, K.; Qin, S. Antifungal potential evaluation and alleviation of salt stress in tomato seedlings by a halotolerant plant growth-promoting actinomycete Streptomyces sp. KLBMP5084. Rhizosphere 2020, 16, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, A.M.; Murphy, T.M.; Okubara, P.A.; Jacobsen, K.R.; Swensen, S.M.; Pawlowski, K. Novel Expression Pattern of Cytosolic Gln Synthetase in Nitrogen-Fixing Root Nodules of the Actinorhizal Host, Datisca glomerata. Plant Physiology 2004, 135, 1849–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdali, H.; Hafidi, M.; Virolle, M.J.; Ouhdouch, Y. Growth promotion and protection against damping-off of wheat by two rock phosphate solubilizing actinomycetes in a P-deficient soil under greenhouse conditions. Applied Soil Ecology 2008, 40, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.S.; Kun, T.; Shun, X.G. The plant growth-promoting fungus (PGPF) Alternaria sp. A13 markedly enhances Salvia miltiorrhiza root growth and active ingredient accumulation under greenhouse and field conditions. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Mahmood, A.; Kataoka, R.; Takagi, K. Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) degradation by Streptomyces sp. isolated from DDT contaminated soil. Bioremediation Journal 2021, 25, 148–158. [Google Scholar]

- Daigham, G.E.; Mahfouz, A.Y.; Abdelaziz, A.M.; Nofel, M.M.; Attia, M.S. Protective role of plant growth-promoting fungi Aspergillus chevalieri OP593083 and Aspergillus egyptiacus OP593080 as biocontrol approach against Alternaria leaf spot disease of Vicia faba plant. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2024, 14, 23073–23089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar Diaz, P.A.; Gil, O.J.; Barbosa, C.H.; Desoignies, N.; Rigobelo, E.C. Aspergillus spp. and Bacillus spp. as growth promoters in cotton plants under greenhouse conditions. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. 2021, 5, 709267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudjordjie, E.N.; Sapkota, R.; Steffensen, S.K.; Fomsgaard, I.S.; Nicolaisen, M. Maize synthesized benzoxazinoids affect the host associated microbiome. Microbiome 2019, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, O.S.; Ayangbenro, A.S.; Glick, B.R.; Babalola, O.O. Plant health: Feedback effect of root exudates-rhizobiome interactions. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2019, 103, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molefe, R.R.; Amoo, A.E.; Babalola, O.O. Communication between plant roots and the soil microbiome; involvement in plant growth and development. Symbiosis 2023, 90, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igiehon, N.; Babalola, O. Rhizosphere microbiome modulators: Contributions of nitrogen fixing bacteria towards sustainable agriculture. International Journal of Environment Research Public Health 2018, 15, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkhalek, A.; Bashir, S.; El-Gendi, H.; Elbeaino, T.; El-Rahim, W.M.A.; Moawad, H. Protective activity of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae strain 33504-Mat209 against Alfalfa Mosaic Virus Infection in Faba Bean Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbodjato, N.A.; Assogba, S.A.; Babalola, O.O.; Koda, A.D.; Aguegue, R.M.; Sina, H.; Dagbenonbakin, G.D.; Adjanohoun, A.; Baba-Moussa, L. Formulation of biostimulants based on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for maize growth and yield. Front Agron 2022, 4, 894489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semchenko, M.; Lepik, A.; Abakumova, M.; Zobel, K. Different sets of belowground traits predict the ability of plant species to suppress and tolerate their competitors. Plant Soil 2017, 424, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, B.; Brader, G.; Pfaffenbichler, N.; Sessitsch, A. Next generation microbiome applications for crop production-limitations and the need of knowledge-based solutions. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2019, 49, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, S.P.; Akanmu, A.O.; Babalola, O.O. Rhizospheric microorganisms: The gateway to a sustainable plant health. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2022, 6, 92580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaya, L.; Istifadah, N.; Hartati, S.; Joni, I.M. In vitro study of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and endophytic bacteria antagonistic to Ralstonia solanacearum formulated with graphite and silica nano particles as a biocontrol delivery system (BDS). Biocatalalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2019, 19, 101153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.K.; Malik, K.A.; Hameed, S.; Saddique, M.J.; Fatima, K.; Naqqash, T.; et al. Growth stimulatory effect of AHL producing Serratia spp. from potato on homologous and non-homologous host plants. Microbiological Research 2020, 238, 126506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, R.; Agrawal, L.; Singh, S.P.; Singh, P.C.; Prasad, V.; Chauhan, P.S. Paenibacillus lentimorbus induces autophagy for protecting tomato from Sclerotium rolfsii infection. Microbiological Research 2018, 215, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.Z.; Sandhya, V.; Grover, M.; Linga, V.R.; Bandi, V. Effect of inoculation with a thermotolerant plant growth promoting Pseudomonas putida strain AKMP7 on growth of wheat (Triticum spp.) under heat stress. Journal of Plant Interaction 2011, 6, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.C.; Song, R.Q.; Qi, J.Y.; Deng, X. Ectomycorrhizal fungus enhances drought tolerance of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica seedlings and improves soil condition. Journal of Forestry Research 2018, 29, 1775–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.B.; Gowtham, H.G.; Murali, M.; Hariprasad, P.; Lakshmeesha, T.R.; Murthy, K.N.; Amruthesh, K.N.; Niranjana, S.R. Plant growth promoting ability of ACC deaminase producing rhizobacteria native to Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2019, 18, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, N.J.; Ebbole, D.J.; Hamer, J.E. Identification and characterization of MPG1, a gene involved in pathogenicity from the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. The Plant Cell 1993, 5, 1575–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Topalovic, O.; Geisen, S. Nematodes as suppressors and facilitators of plant performance. New Phytologist 2023, 238, 2305–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucu, M.A.; Gilardi, G.; Pugliese, M.; Ferrocino, I.; Gullino, M.L. Effects of biocontrol agents and compost against the Phytophthora capsici of zucchini and their impact on the rhizosphere microbiota. Applied Soil Ecology 2020, 154, 103659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, A.; Gilardi, G.; Idbella, M.; Zotti, M.; Pugliese, M.; Bonanomi, G.; Gullino, M.L. Trichoderma enriched compost, BCAs and potassium phosphite control Fusarium wilt of lettuce without affecting soil microbiome at genus level. Applied Soil Ecology 2023, 182, 104678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant host | Rhizosphere Microbes | Plant growth Mechanism |

Resistance Mechanism |

Abiotic Pressure | Pathogen | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Promoting Bacteria/ Actinobacteria | ||||||

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum) |

P. putida | Produce more tiller, grain/ spike formation & 100 seed weight | Higher antioxidant activity, Proline, Total proteins, Sugars & Amino acids | Heat Stress | - | [102] |

|

Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) |

Pseudomonas strains R62 & R81 | Increase dry root weight, shoot weight & fruit yield under field conditions |

Control wilt disease incidence |

- | Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. lycopersici | [44] |

| - | Streptomyces albogriseolus | Higher 6-methyl-fungichromin | - | - | Meloidogyne incognita & Meloidogyne javanica | [38] |

| Chilli (Capsicum annuum) |

Actinomycetes | Increase plant height, stem diameter, leaves number & leaf area | Increased radical volume & reduce disease severity | - |

Phytophthora capsici |

[39] |

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum) |

Arthrobacter protophormiae (SA3) & Dietzia natronolimnaea (STR1) | Promote IAA content & reduced ABA/ACC content | - | Increase (ABA) & ACC under salt & drought stress | - | [67] |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) |

Paenibacillus lentimorbus | - | Expression of defense-related & autophagy-related genes |

- |

Sclerotium rolfsi | [101] |

| Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) |

Saccharothrix yanglingensis | Antifungal activity & Chitinase Production |

- |

Valsa mali | [40] | |

| Potato (Solanum tuberosum) | Lysinibacillus sp. | - | Antibiosis |

- |

Ralstonia solanacearum | [99] |

| Helianthus annuus | Bacillus subtilis | Increase Plant Biomass, Phosphate & iron solubilization, | Phytohormone production | - | Fusarium oxysporum |

[104] |

|

Solanum tuberosum Oryza sativa, Zea mays & Phaseolus vulgaris |

Serratia spp. | Higher phytase activity |

AHLs- acyl homoserine lactone & phytohormone production | - | - | [100] |

| Limonium sinense | Bacillus flexus KLBMP 4941 | Increase root length, shoot length & fresh weight | Organic acids production | Mitigated salt stress by producing organic acids (stearic, palmitic, palmitoleic & oleic acids | - | [64] |

| Wheat (Triticum turgidum) | Bacillus cabrialesii | Increase chlorophyll content & Roots colonization | Increased antibacterial metabolites such as Bacillaene, Bacilysin, Bacillibactin & subtilosin-A | - | Bipolaris sorokiniana | [28] |

| Solanum lycopersicum | Dermacoccus abyssi | Phosphate solubilization, Phytohormone (IAA) production, more total soluble sugar & total chlorophyll content |

Mitigated salt stress & osmoregulate by soluble sugars. Increase H2O2 scavenging activity | - |

- | [57] |

| Zea mays | Pseudomonas fluorescens | - | Reduced ear rot disease incidence | Fusarium moniliforme | [58] | |

| Growth Promoting Fungi/ Mycorrhizae | ||||||

| Tagetes erecta |

Penicillium citrinum & Penicillium simplicissimum |

Maximized the carbohydrates & reducing sugars. Increased size, dry matter & flower early. | Produced root exudated & enhanced polygalacturonase, & cellulase enzymes activity |

- | - | [27] |

| Cucumis melo | Trichoderma harzianum Trichoderma ghanense & Trichoderma hamatum. | Maximize leaves number, root and shoot weight, & IAA production | Inhibitory activity, Decrease wilt Incidence, Increase in SA & JA. |

More ACC deaminase |

Fusarium oxysporum | [10] |

| Sesamum indicum | Penicillium sp. NICS01 | Increased plant length, amino acid content & plant weight. | - | Salt stress | - | [17] |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) |

Funneliformis mosseae. | Increased biomass (Root and Shoot Fresh weight) | Improving Antioxidant Machinery |

Lowered Ascorbate, glutathione, redox ratio & L-galactono-1,4- lactone dehydrogenase ratio | - | [13] |

| Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica |

G. mosseae, G. etunicatum, G. claroideum, G.microaggregatum, G. geosporum & R. irregularis |

Promoted Lycopene & β-Carotene contents |

Increased antioxidant potential by enhancing ascorbic acid content |

Improved Leaf water content (%) under water stress. |

[14] | |

|

Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica |

Trichoderma harzianum E15 Trichoderma virens & S. luteus | Improved root structure by increasing root length & surface area. Increased fresh & dry weight. |

Lower proline content & MDA content | Increase superoxide dismutase-SOD & peroxidase-POX) activity to withstand drought stress |

- |

[15,103] |

| Chilli (Capsicum annuum L.) |

Talaromyces funiculosus | Phosphate solubilization, Siderophore, HCN, IAA, Chitinase & Cellulase production, Increase chlorophyll, fruit weight & plant Biomass. | Higher antagonistic activity, Disease Protection, PAL, POX, Chitinase, ISR, Lignin & Callose production | - | Colletotrichum capsici | [08] |

| Drum stick (Moringa Oleifera) |

P. chrysogenum & T. viride |

- | Maximize Antagonistic behaviour | - |

Fusarium oxysporum, Penicillium digitatum, & Aspergillus wentii |

[09] |

| Rape Mustard (Brassica juncea) | Trichoderma harzianum | Plant height, Root Length & Plant Dry weight | Maximized SOD, POD, APX, GR, GST, GPX, GSH & GSSG activities | Plant tolerant to saline stress [Proline 59.12%, H2O2 69.5% & MDA contents by 36.5%] |

- | [26] |

| Maize (Zea mays) |

Trichoderma harzianum |

Promoted root growth size, area & root hair area | Reduced anthracnose symptoms by maximizing β,1-3 glucanase, exochitinase & endochitinase in roots & shoots. |

- |

Pythium ultimum, & Colletotrichum graminicola |

[35] |

|

Brassica campestris L. var. perviridis. |

Talaromyces wortmannii | Increased growth by high levels of β-caryphyllene contents | Reduce infection symptoms |

- |

Colletotrichum higginsianum | [36] |

| Chilli (Capsicum annuum) | Arbuscular Vesicular Mycorrhizae (AMF) | More plant height, stem diameter, leaves number & leaf area | Increased radical volume & reduced disease severity |

- |

Phytophthora capsici |

[39] |

| Phaseolus vulgaris | Trichoderma sp. | Enhanced root length & aerial parts | Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) |

- |

- |

[41] |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) |

Rhizoctonia G1, L2, W1 & W7 | Increase Plant weight (stems & leaves). | Reduced Disease Severity |

- |

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici |

[51] |

| Cucumber (Cucumis melo) |

Funneliformis mosseae | More fresh weight & dry weight was noticed | Increased Phenols, flavonoids, lignin, DPPH activity & phenolic compounds | Increased tolerance to temperature stress by maximizing glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH), shikimate dehydrogenase (SKDH), (PAL), cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), (PPO), guaiacol peroxidase (G-POD), caffeic acid peroxidase (CA-POD) & chlorogenic acid peroxidase (CGA-POD). |

- |

[72] |

| Maize | Pseudomonas putida | - | Benzoxazinoids Allelochemical/ antimicrobial effect |

- | - | [60] |

| Cucumis sativus | Exophiala sp. LHL08 | GA production | Induce defense response by SA production | Increased abscisic acid (ABA) & other phytohormone production under salinity & drought | - | [53] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).