1. Introduction

Cotton [

1,

2] is an important global cash crop in 80 countries with a total planted area of 32 million hectares and an estimated annual value of

$5.7 billion, with China, India and the United States of America the largest producers, with more than half of global production [

3]. Xinjiang, the largest cotton-growing region in China, had a total output of 5.1 million tons in 2023, accounting for more than 90.00% of total Chinese production. Pests are a serious threat to production; according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, annual global economic losses caused by pests are estimated to be billions of dollars [

4].

There are a wide variety of cotton pests, including

Aphis gossypii,

Tetranychus cinnabarinus, and

Thrips tabaci. Currently, pest control relies primarily on chemical pesticides, which achieve quick and effective control and reduce losses; for example, synthetic pyrethroids and organophosphates significantly reduce pest populations in the short term[

5]. Although chemical pesticides remain important, their misuse has sparked widespread controversy [

6]. Excessive use of insecticides can have a negative impact on beneficial insects and the environment [

7]. Prolonged use of synthetic pesticides may also lead to the development of resistance [

8]. For these reasons, biopesticides are becoming increasingly important in the context of rising demand for green agriculture [

9]. Their use not only significantly reduces pollution and harm to agricultural products, but also counteracts the problem of resistance to traditional chemical pesticides [

10].

Bacillus produce a variety of biologically active substances with high bacteriostatic activities, antagonistic spectra, environmental friendliness, and other advantages. They provide a powerful alternative to chemical fertilizers and pesticides, as many bacteria themselves have strong resistance, high survival, and rapid reproduction; therefore, biological control is widely used [

11].

B. thuringiensis produces δ-endotoxins, including Cry and Cyt proteins, which are toxic to a wide range of insects. Cry proteins are effective against specific insect orders, including Lepidoptera, Diptera, Hymenoptera, and Coleoptera; whereas Cyt proteins are toxic to Diptera [

12].

B. sphaericus is capable of producing a variety of lipopeptides with antimicrobial activity and has been used to control pests. For example, lipopeptide metabolites produced by

B. subtilis have been used to control

Spodoptera littoralis,

Drosophila melanogaster,

Culex quinquefasciatus,

Anopheles stephensi and Aedes aegypti [

13]. Bora et al. identified compounds produced by

Bacillus species using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), including Brevianamide A, Heptadecanoic acid, Thiolutin and Versimide, which showed toxicity against

Oligonychus coffeae [

14].

As the largest desert in China, the extreme environment of the Taklamakan Desert has created unique microbial resources, with

Bacillus spp. the dominant bacteria [

15]. In this study, we aimed to screen strains with efficient

A. gossypii killing activity and to explore their insecticidal active components to provide strain resources and theoretical support for the development of insecticidal biopesticides. To this end, we screened 107 such strains from the Taklamakan Desert for

A. gossypii killing activity. We further characterized them by multiple methods.

2. Materials and Methods

Experiments were conducted at Tarim University, College of Life Science and Technology, Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, Key Laboratory of Conservation and Utilization of Biological Resources in the Tarim Basin.

2.1. Bacteria

All 107 strains of Bacillus spp. selected for this study were provided by the Microbial Strain Resource Bank of Tarim University and had been isolated from the Taklamakan Desert. They were preserved by freeze-drying at 5 °C. They were cultured in LB solid and liquid media.

2.2. Insects

A. gossypii was collected from the Horticultural Experiment Station of Tarim University (81°17 'E, 40°32 'N) during the infestation period. For their maintenance and expansion, cotton seeds were first soaked in pure water for 2–3 days until white shoots developed. Soil was prepared from ratio of nutrient soil:coconut bricks:vermiculite at a ratio of 5:3:2. Seeds were sown at 3–5 cm in this soil and kept moist. Seedlings were watered twice or thrice weekly after emergence. After 2–3 weeks, insects were placed onto the back of the leaves using a fine brush. Insects were reared at 25 °C, 50.00% humidity, and 12:12-h light:dark cycles in 50 × 50 × 65 cm (L×W×H) cages.

2.3. Screening

For shake-flask fermentation, bacteria were thawed at 4 °C, inoculated onto LB plates, and incubated at 28 ºC incubators for 2 days. Colonies were inoculated into liquid LB and shaken at 120 rpm at 30 °C for 2–3 days.

A. gossypii killing was measured from these cultures using the leaf-dip method [

16]. LB without bacteria was used as a negative control and 0.1 g/mL of a 20.00% fludioxonil suspension (Jiangsu Keshen Group Co., Ltd.) was used as a chemical control. Assays were performed in triplicate. Twenty test insects were tested per replicate. Mortality and corrected mortality rates were calculated as:

Mortality rate = number of dead insects/total number of test insects × 100%

Corrected mortality (%) = Mortality in treatment (%) − Mortality in control (%)/100 − Mortality in control (%) × 100

2.4. Strain Characterization

Strains with activity were observed on LB plates. Their microstructures were further observed using scanning electron microscopy. Their DNA was extracted using SDS-CTAB [

17], amplified by PCR using primers 27F and 1492R for the 16S rRNA gene, and sequenced by Sangon Bioengineering Co. (Shanghai, China). The EzBioCloud database (

www.EzBioCloud.net) was utilized for comparison. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of published strains with high similarity were used to construct phylogenetic trees using MEGA 5.05 software to determine the taxonomic status of the strains [

18].

2.5. Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) and antiSMASH

Strains were inoculated into LB grown with at 30 °C with shaking at 120 rpm for 24 h. Bacteria were pelleted at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C and sent to Personal Bio (Shanghai, China, which used the shotgun, paired-end WGS using the Illumina NovaSeq platform. Data with removed splice sequences were assembled from scratch using A5-MiSeq and SPAdes software to construct contigs and scaffolds. Corrections were made using Pilon software [

19,

20,

21]. Functional annotations were obtained by comparison with the NR, eggNOG, KEGG, and Swiss-Prot databases using BLAST software. Secondary metabolite synthesis genes were predicted using antiSMASH (antismash.secondarymetabolites.org).

2.6. Isolation and Characterization of Insecticidal Compounds

Strains exhibiting activity were fermented in large batches. Based on the antiSMASH data, small-molecule compounds were isolated and purified by macroporous resin adsorption, ODS column chromatography, gel column chromatography, and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), then analyzed by

1HNMR,

13CNMR, HSQC, and HMBC spectroscopy [

22,

23]. Larger candidates, such as proteins, were precipitated using ammonium sulfate, purified using gel filtration, and sequenced by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [

24,

25]. Lipopeptides were ethanol precipitated and acid (HCl) precipitation was used to obtain lipopeptides [

26], which were purified by three to five acid washes and deionized water rinses (at 5 °C) in small amounts and many times to pH 6–7. Powdered lipopeptides were obtained by freeze-drying and analyzed using ACQUITY UPLC/VION IMS QTOF MS Compositional testing was performed.

2.7. Insecticidal Assays

Based on the results of the preliminary experiments testing the activity of the products against A. gossypii, gradient concentrations were prepared to conduct insecticidal activity tests. Toxicity regression curves were used to calculate lethal median concentration (LC

50) values [

27].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Experimental data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using DPS_V9.01 software and tested for the significance of differences using Duncan's new compound extreme deviation method (p<0.05). Virulence equations and LC50 were calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software. Graphs and charts were produced using Origin 2021 software.

3. Results

3.1. Screening Identified Two Active Bacillus Strains

The leaf-dip method was used to determine the virucidal activity of shake flask fermentation broth of 107 strains of

Bacillus spp. against

A. gossypii. The corrected mortality rate of

A. gossypii ≥ 60.00% after 48 h of treatment was used as the criterion for the evaluation of active strains. Two strains with high insecticidal activity were identified. Of the two, strain TRM82479 had higher activity, causing 75.00% mortality with a corrected mortality rate of 73.21% (

Table 1). Data from both strains are shown in

Figure 1.

As strain TRM82479 had higher insecticidal activity, it was subjected to species identification, WGS, antiSMASH, and isolation insecticidal active components.

3.2. Species Identification

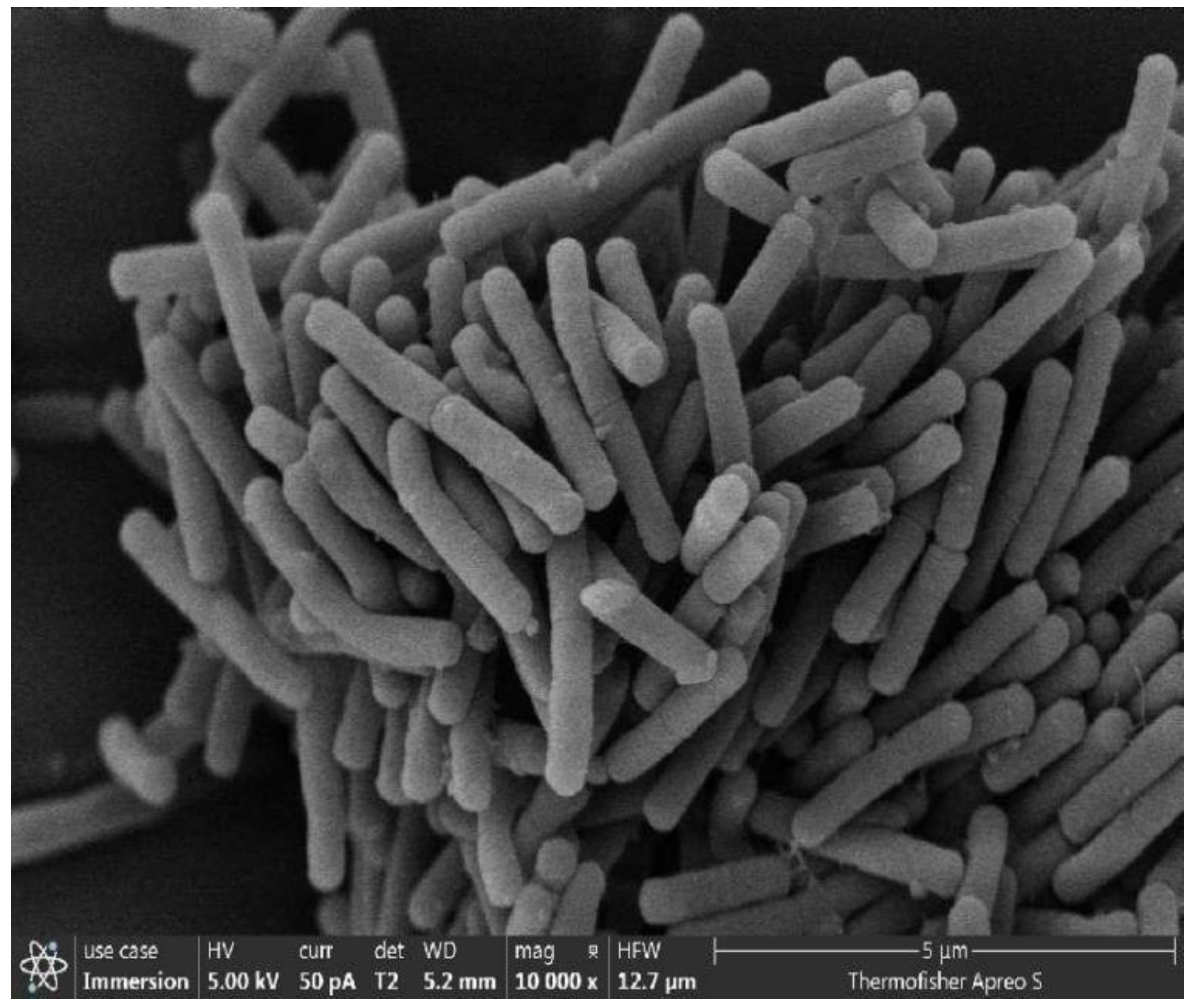

Strain TRM82479 formed milky-white, nearly round colonies on LB plates with a glossy surface (

Figure 2). By scanning electron microscopy, its cells were long and cylindrical, 2–4 μm in length, with a smooth cell surface (

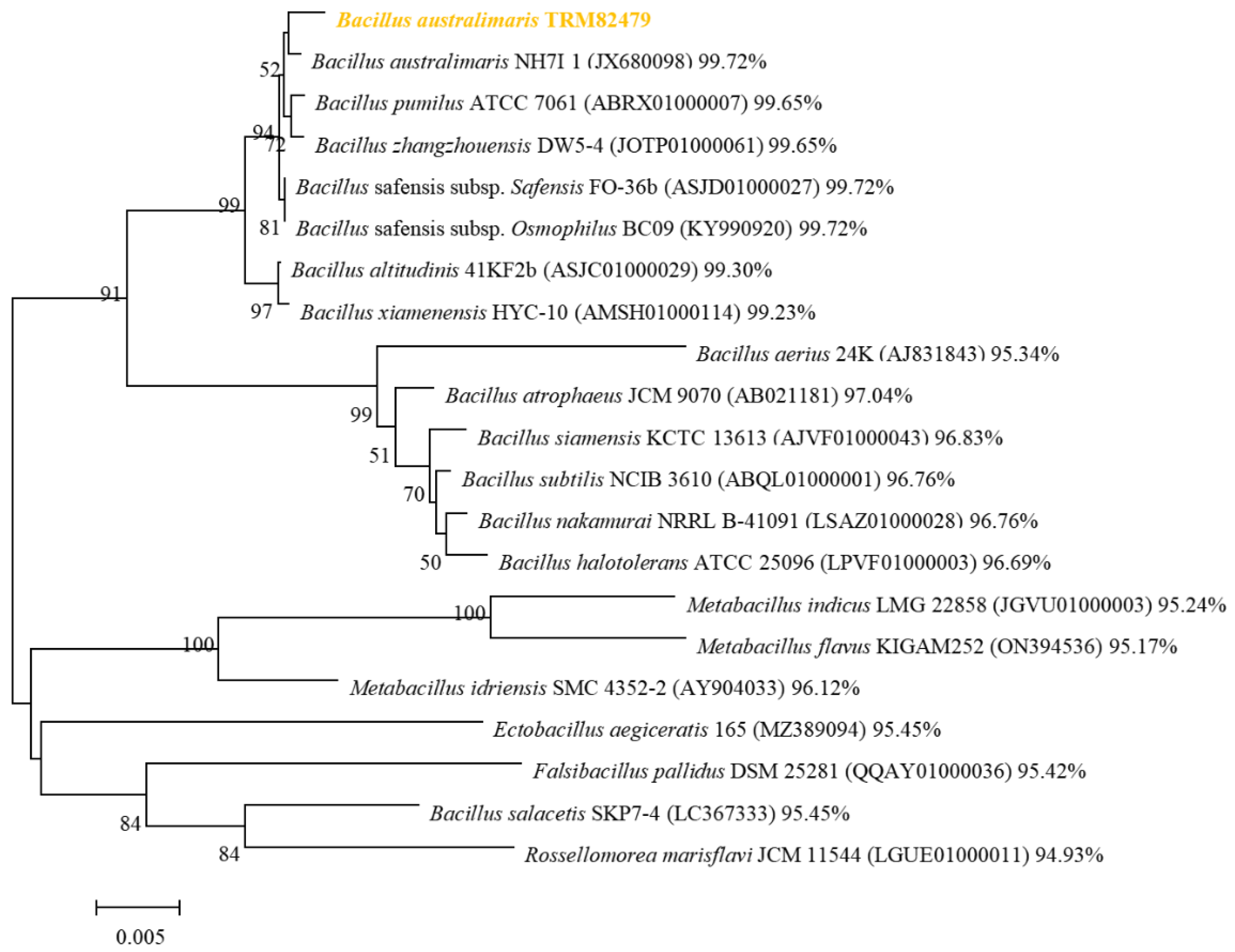

Figure 3). The 16S rRNA sequence of strain TRM82479 was compared with those in the EzBioCloud database. We observed a similarity of 99.72% with the 16S rRNA sequence of

B. australimaris NH71_1; other 16S rRNA sequences similar to this strain were retrieved and downloaded from the EzBioCloud database, and used to construct a phylogenetic tree. The tree suggests that TRM82479 is most closely related to

B. australimaris NH71_1; therefore, the strain was preliminarily identified as

B. australimaris TRM82479 (

Figure 4). The 16S rRNA sequence of this strain has been uploaded to NCBI under GenBank accession number PQ423094.

3.3 Strain TRM82479 Genome Contains Clusters of Genes Associated with Lipopeptide Analog Synthesis

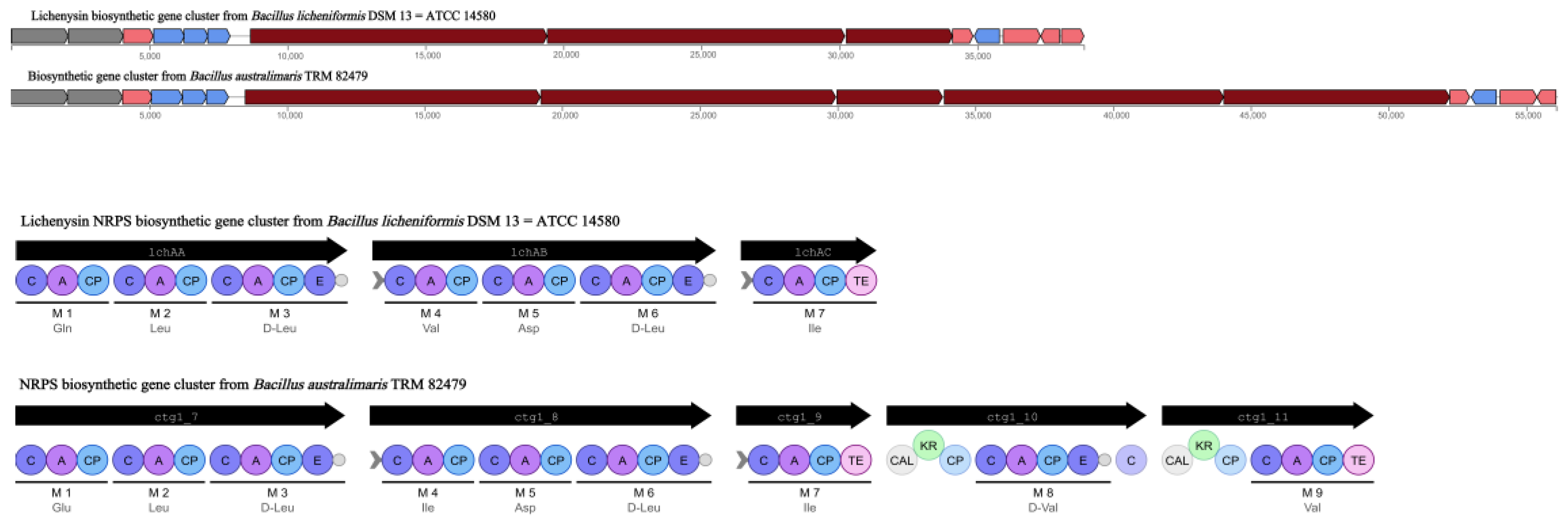

Based on WGS, 12 clusters of secondary metabolite synthesis genes were predicted using the antiSMASH database. Of these, six clusters had higher similarity to known gene clusters, with two associated with fengycin and lichenysin synthesis (

Table 2). In a comparison of Cluster 8 with the lichenysin, 92.00% similarity was found. This cluster of includes three NRPS genes, lchAA, lchAB, and lchAC; it is responsible for the synthesis of a lipopeptide containing seven modules: Gln, Leu, D-Leu, Val, Asp, D-Leu, and Ile. In contrast, the cluster of

B. australimaris TRM82479 includes multiple gene fragments (ctg1_7, ctg1_8, ctg1_9, ctg1_10, and ctg1_11) and contains nine modules: Glu, Ile, D-Leu, Ile, Asp, D-Leu, Ile, D, and Val. In modules 8 and 9, there were modifier enzyme domains such as CAL and KR, but the last putative esterase gene in the lichenysin biosynthesis gene cluster was not observed. These differences suggest that the TRM82479 lipopeptides are significantly different structurally and functionally from lichenysin (

Figure 5). In summary,

B. audiculmaris TRM 82479 may produce lipopeptides that are distinct from fengycin and lichenysin, and lipopeptides have been reported in recent years to have insecticidal activity, we isolated lipopeptides from this strain.

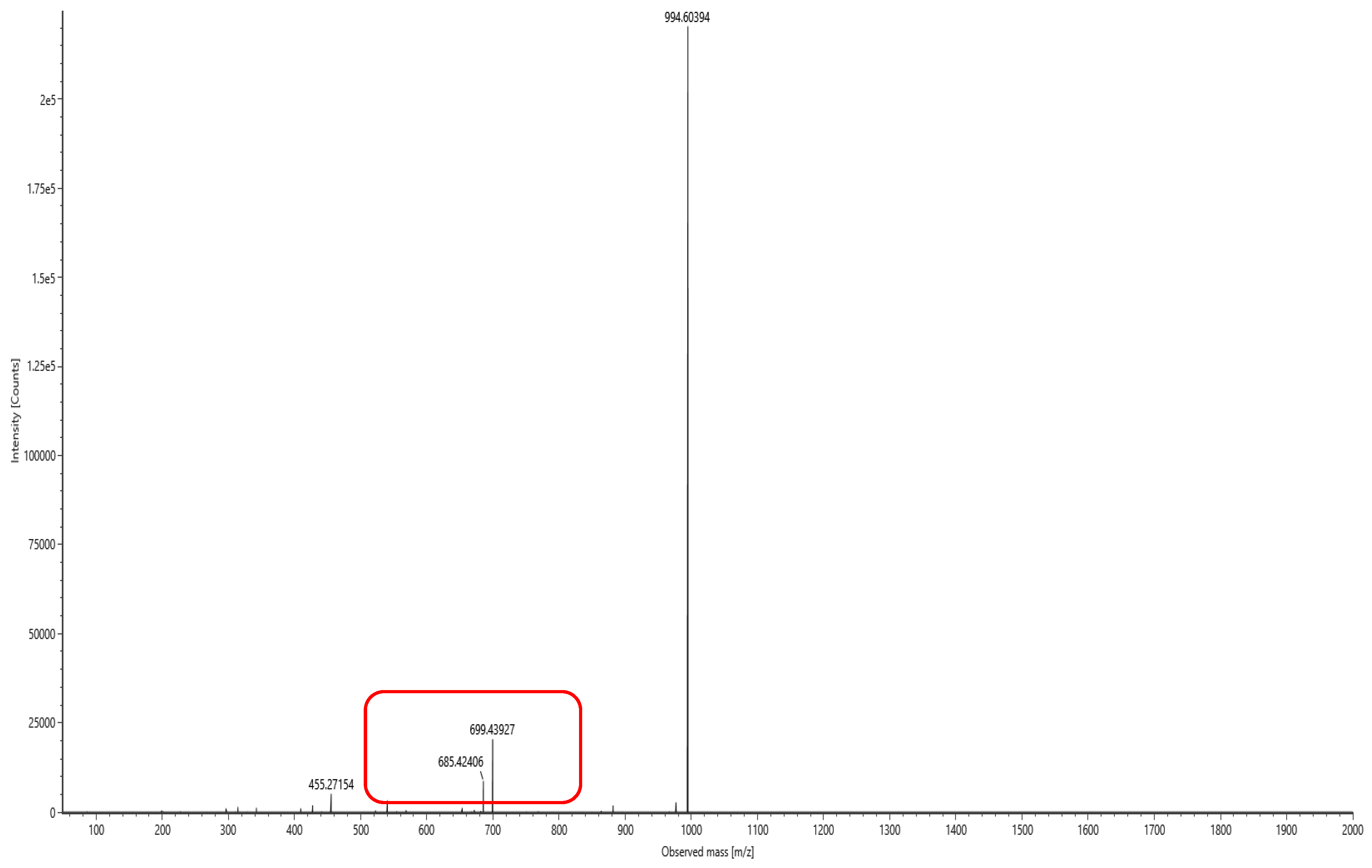

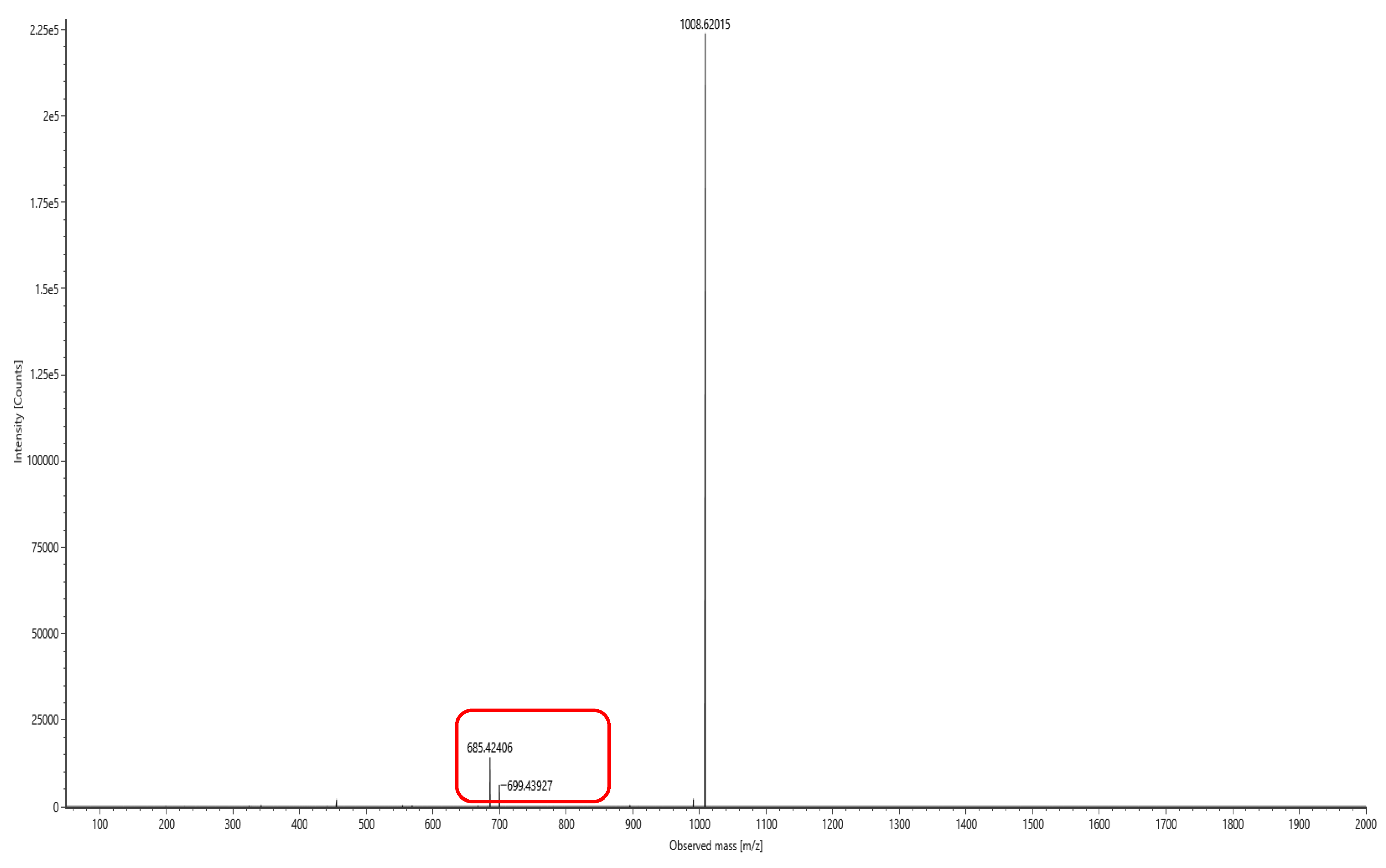

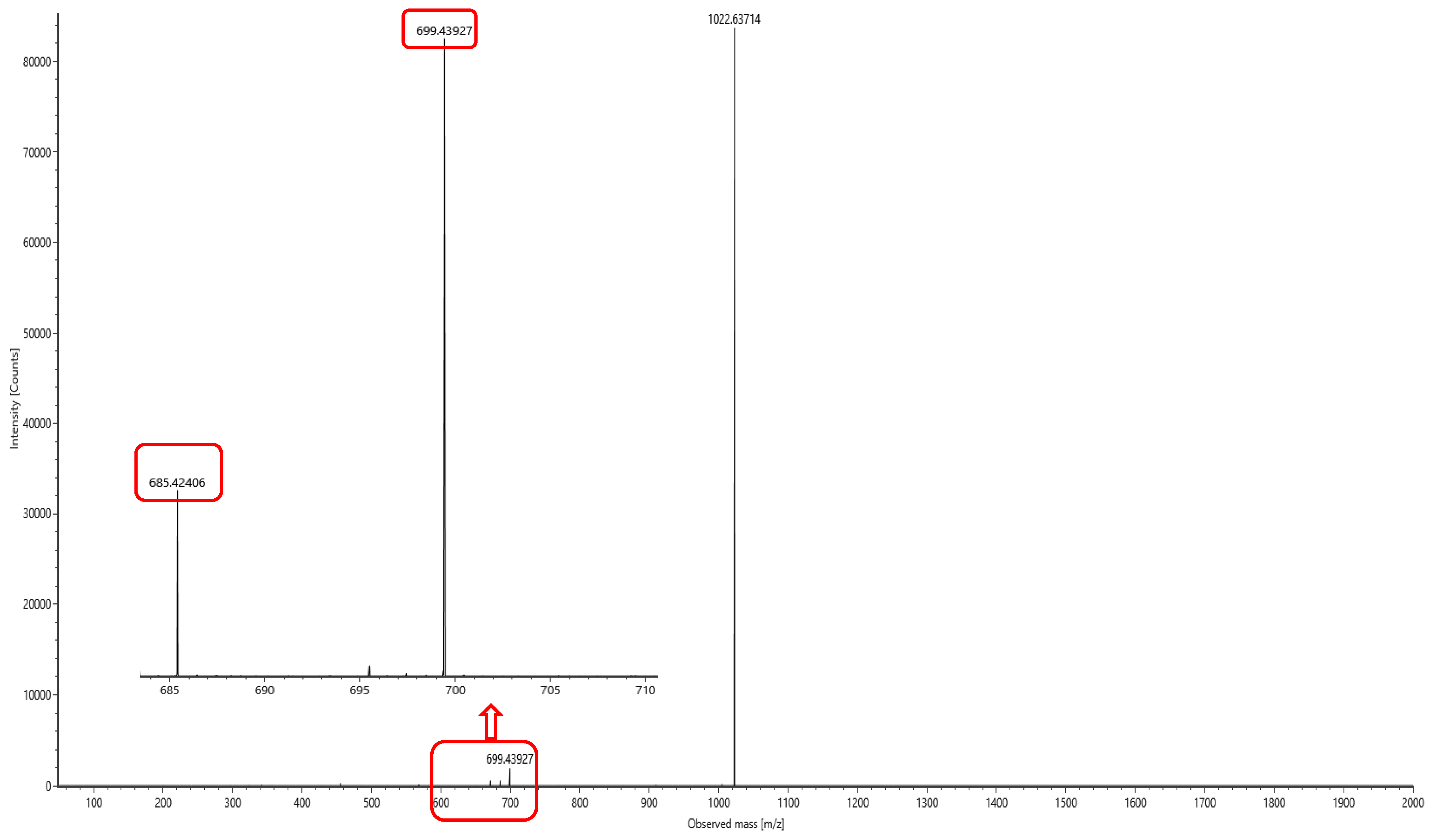

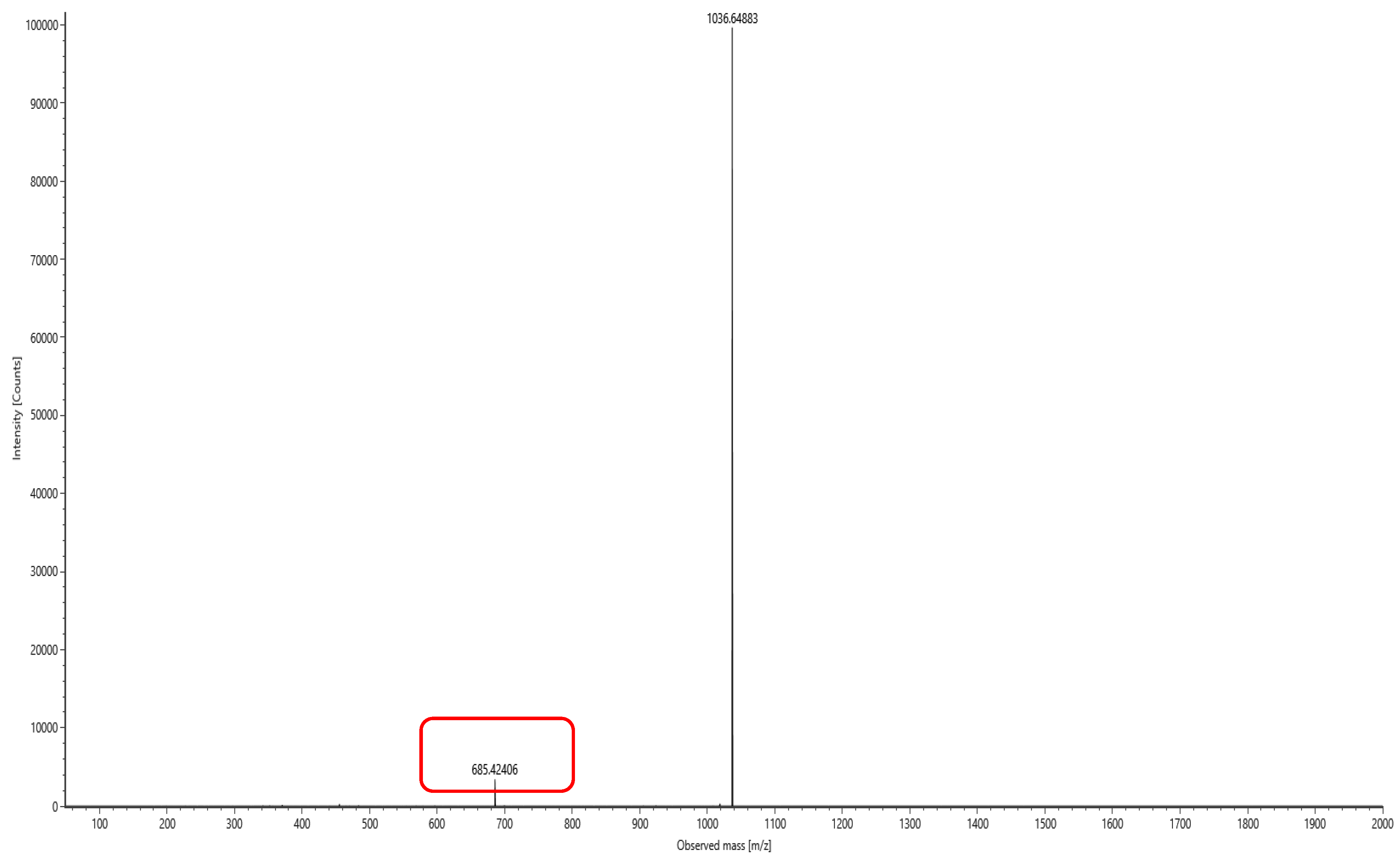

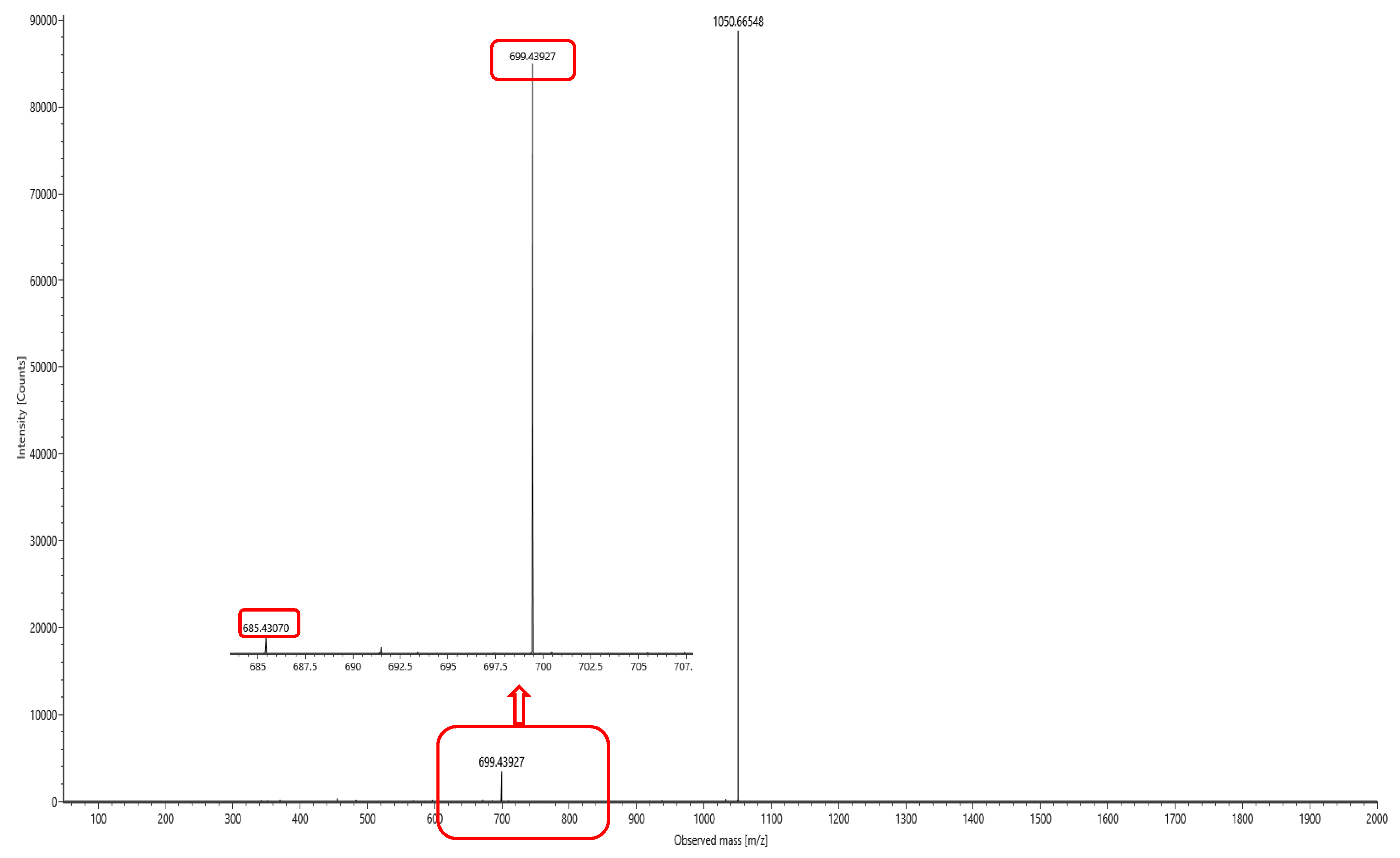

3.4 Identification of Insecticidal Components

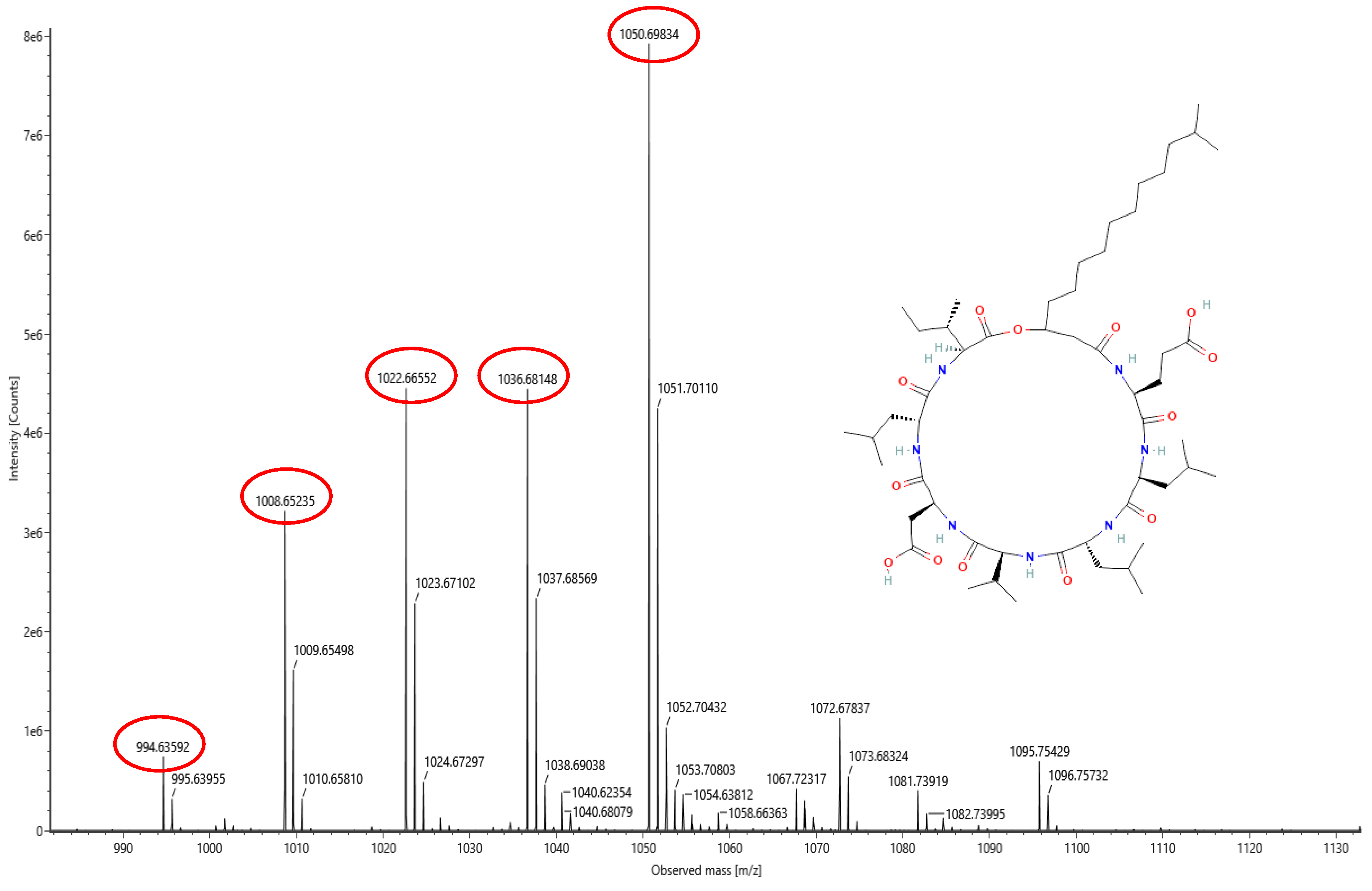

The lipopeptide compounds obtained by isolation and purification were detected by

ACQUITY UPLC/VION IMS QTOF MS (Positive ion mode scanning, mass scanning range of 50–2000 m/z, Capillary voltage: 3.00 kV; Source temperature: 100 °C; Desolvation temperature: 500 °C; Cone gas: 50 L/h; Desolvation gas: 800 L/h), and ion peaks with regularity of m/z of 994.63592, 1008.65235, 1022.66552, 1036.68148, and 1050.69834 appeared in the primary mass spectra, which were presumed to be the fatty acid chains differing by one substituent methyl (-CH

2) homologue of Surfactin [

28]. Secondary MS was performed on the above five ion peaks. Both 685.4 and 699.4 fragments were present in the secondary mass spectra; the former corresponds to a known characteristic fragment of surfactin, corresponding to the fatty acid chain +Glu (N-terminal fragment after ring-opening) that frequently appears in the MS/MS spectra of Surfactin as a B

1 ion [

29]. The latter fragment likely corresponds to an increase in fatty acid chain length by one CH

2 of the B

1 ion, or the replacement of Val with Leu or Ile. Together, these data strongly suggest that the lipopeptide analog belongs to the surfactin series (

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

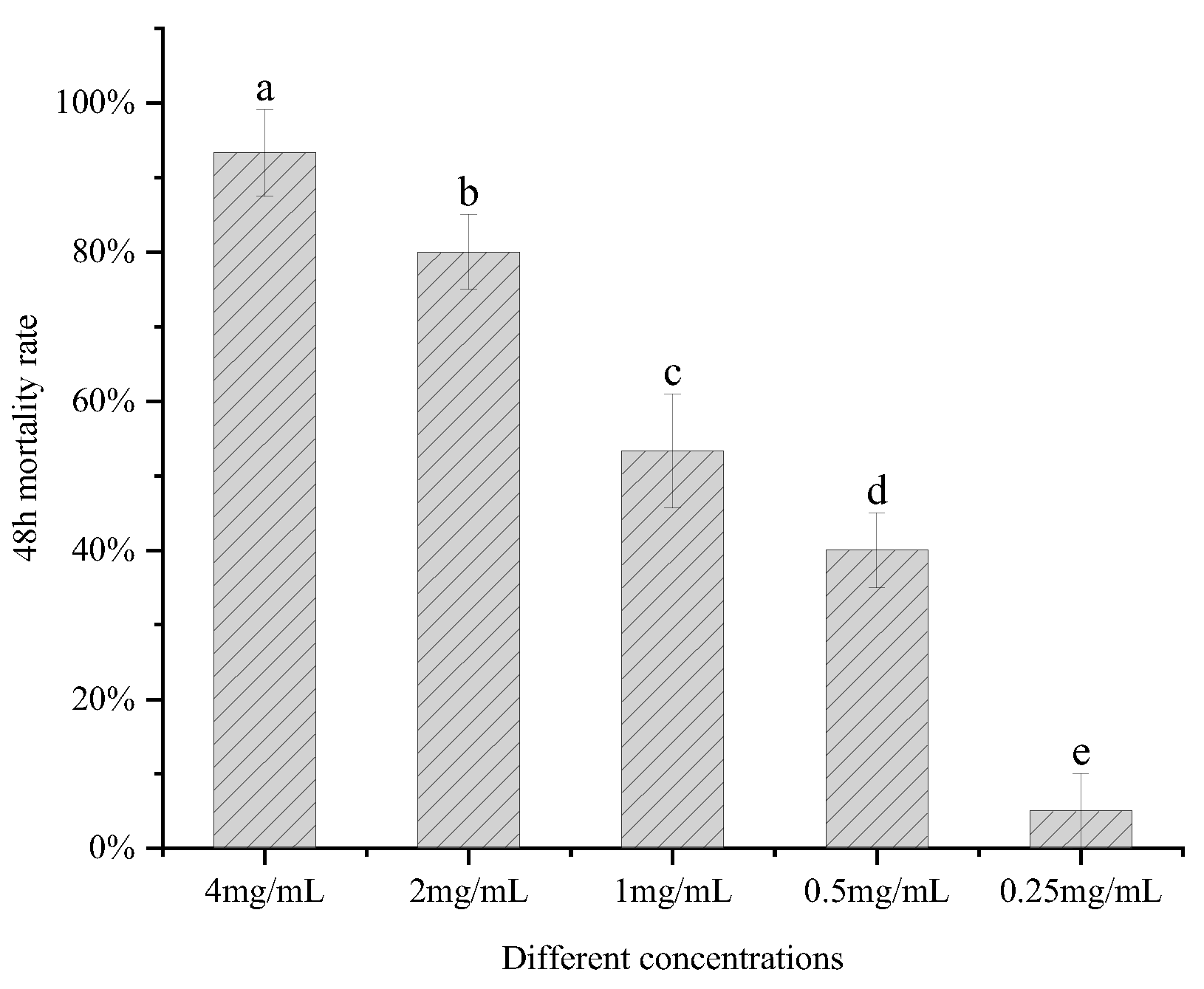

3.5 Surfactin Insecticidal Activity

The aqueous surfactant was dissolved in deionized water with ultrasound assistance at a concentration of 4 mg/mL and tested for

A. gossypii killing activity using foliar sprays [

30], which yielded an

A. gossypii mortality rate of 93.33% at 48 h. Surfactin at concentrations of 2 mg/mL, 1 mg/mL, 0.5 mg/mL, and 0.25 mg/mL yielded mortalities of 80.00%, 53.33%, 40.00%, and 5.00% respectively (

Figure 12). The toxicity regression equation was calculated as Y = 2.331X + 0.156, with an LC

50 of 0.857 mg/mL and an LC

95 of 4.350 mg/mL.

4. Discussion

A. gossypii is one of multiple pests that pose a serious threat to cotton crops. Bacteria provide safer and more environment-friendly alternatives to commercially available synthetic aphidicides [

31]. Numerous studies have shown that certain

Bacillus species exert insecticidal effects against multiple pests and diseases in a wide range of crops [

32,

33,

34]. In this study, we used 107

Bacillus strains isolated from the Taklamakan Desert to explore the

A. gossypii killing potential. We identified two

A. gossypii-killing strains, TRM82467 and TRM82479, under laboratory conditions, with strain TRM82479 showing a 48-h lethality of 75.00% against

A. gossypii (

Table 1). In addition, morphological observations revealed that

A. gossypii was morphologically complete before the activity test, with a yellowish body color, smooth body surface, and clear antennae and foot structures; 24 h after the activity test, the color of

A. gossypii became slightly darker, and the body surface appeared slightly wrinkled or discolored; 48 h after the activity test, the morphological changes of

A. gossypii were more obvious, with significant wrinkling or discoloration of the body surface; severe crumpling (twisting of the abdomen and folding of the legs) and discoloration of

A. gossypii worms occurred 72 h after the activity test (

Figure 1). It has been hypothesized that these changes are caused by a combination of microbial lipopeptides and extracellular cuticle-degrading enzymes (chitinases and proteases), which degrade the chitin and protein components of the cuticle and disrupt the basic function of the exoskeleton [

35].

Previous studies have confirmed the insecticidal efficacy of multiple

Bacillus species. Ruiu et al. found that the spores of

Brevibacillus laterosporu infect

Musca domestica and that this group of bacteria adsorbs secreted laterosporamine toxin to the spores, producing insecticidal activity [

36]. Fathy et al. isolated 200 strains of

B. subtilis from mangrove ecosystems in Egypt and tested their activity against

Spodoptera frugiperda. Among these,

B. subtilis Esh73 had the highest larval mortality (80.00%) [

13]. Ma et al. identified eight

B. thuringiensis strains with activity against

Culex pipiens pallens larvae and adults, with the spore-crystal mixture of strain A4 showing significant activity against larvae with an LC

50 of 1.4±0.5 µg/mL [

37]. Al-Azzazy et al. tested

B. subtilis (2.470 × 10

8 cfu/ml) and

B. qassimus (3.320 × 10

8 cfu/mL) under laboratory conditions on eggplant infested with

Tetranychus urticae and reductions of 72.22% and 70.74% respectively after seven days of treatment [

38]. Liu et al. investigated the insecticidal activity of lipopeptides isolated from

B. velezensis ZLP-101 against

Acyrthosiphon pisum. The LC

50 of the crude extract of ZLP-101 against bean aphids was 411.535 mg/L. The active components in the crude extract, included iturins, engycins, surfactins, and spergualins [

39].

This study analyzed the secondary metabolite synthesis genes of

B. australimaris TRM82479 using antiSMASH and isolated lipopeptide analogs. The lipopeptides obtained from the isolation and purification were detected by ACQUITY UPLC/VION IMS QTOF MS and were confirmed to be a surfactin series by GNPS database comparison and literature research. Xia et al. reported that surfactin produced by

B. subtilis YZ-1 was significantly toxic to

Tenebrio molitor by Xia (2023) et al [

40]. Moreover, there are few reports on the toxicity of surfactin against

A. gossypii. Therefore, the findings of this study not only expand our understanding of the bioactive substances produced by the

B. australimaris TRM82479 strain but also provide new scientific evidence for surfactin as a potential biopesticide.

5. Conclusions

Our findings indicate that B. australimaris TRM82479 and the surfactin series it produces have significant potential for application in the green control of A. gossypii, for which little has been reported about the toxicological activity of Surfactin against A. gossypii. Although this study achieved remarkable results under laboratory conditions, its effectiveness in field applications needs to be further verified. In addition, the development of surfactin as a biopesticide requires further research on its mechanism of action, effects on non-target organisms, and technical issues for large-scale production. This study provides new strain resources and active substances for the biological control of A. gossypii and lays the foundation for the development of surfactin as a biopesticide. Future studies should explore its potential application in the field.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Package S1: antiSMASH analysis packet; Package S2: Secondary mass spectral raw data of Surfactin; Table S1: Confidence level of surfactin in killing A. gossypii.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Yelin Wang and Zhibin Sun; Methodology, Yelin Wang and Zhanfeng Xia; Resources, Feng Wen and Zhanfeng Xia; Software, Yelin Wang and Zhibin Sun; Supervision, Zhanfeng Xia; Validation, Yelin Wang and Shiyu Wang; Writing – original draft, Yelin Wang; Writing – review & editing, Zhanfeng Xia.

Funding

This work was supported by the Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Program (2022xjkk150307), Open Project of the State Key Laboratory of Microbial Metabolism (MMLKF22-01), and Tarim University Graduate Innovation Program (TDGRI2024007).

Data Availability Statement

All data are presented in the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps Key Laboratory for the protection and utilization of biological resources in the Tarim Basin and for providing the experimental site. We thank the Analysis and Testing Center and the Supercomputing Center of Tarim University for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization |

| LB |

Luria-Bertani |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| LC-MSLC-MS/MSNMR |

Liquid Chromatography-Mass SpectrometryLiquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass SpectrometryNuclear Magnetic Resonance |

References

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Yao, Y.; Peters, G.; Macdonald, B.; La Rosa, A.D.; Wang, Z.; Scherer, L.J.N.R.E. Environment: Environmental impacts of cotton and opportunities for improvement. 2023, 4, 703–715. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Y.; Wu, K.J.I. Managing practical resistance of Lepidopteran pests to Bt cotton in China. 2023, 14, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, G.S.; Scavo, A.; Zingale, S.; Tuttolomondo, T.; Santonoceto, C.; Pandino, G.; Lombardo, S.; Anastasi, U.; Guarnaccia, P.J.A. Agronomic strategies for sustainable cotton production: A systematic literature review. 2024, 14, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kooner, R. Arora RJBircfsa: Insect pests and crop losses. 2017, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Malinga, L. Laing MJAACS: A Review of Pesticides for the Control of Some Cotton Pests. 2024, 9, 1148. [Google Scholar]

- Aktar, W.; Sengupta, D. Chowdhury AJIt: Impact of pesticides use in agriculture: their benefits and hazards. 2009, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, A.V.; Potin, D.M.; Torres, J.B. Torres CSSJE, Safety E: Selective insecticides secure natural enemies action in cotton pest management. 2019, 184, 109669. [Google Scholar]

- Kone, P.W.E.; Didi, G.J.R.; Ochou, G.E.C.; Kouakou, M.; Bini, K.K.N.; Mamadou, D.; Ochou, O.G. Susceptibility of cotton leafhopper Jacobiella facialis (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) to principal chemical families: implications for cotton pest management in Côte d'Ivoire. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Samada, L.H.; Tambunan, U.S.F.J.O.J.B.S. Biopesticides as promising alternatives to chemical pesticides: A review of their current and future status. 2020, 20, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenibo, E.; Ijoma, G.; Matambo, T. Biopesticides in sustainable agriculture: A critical sustainable development driver governed by green chemistry principles. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021, 5, 619058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.; Sharma, D.; Kumar, P.; Dubey, R.C.J.P.; Pathology, M.P. Biocontrol potential of Bacillus spp. for resilient and sustainable agricultural systems. 2023, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajashekhar, M.; Shahanaz, E.; Vinay, K.J.J.E.Z.S. Biochemical and molecular characterization of Bacillus spp. isolated from insects. 2017, 5, 581–588. [Google Scholar]

- Fathy, H.M.; Awad, M.; Alfuhaid, N.A.; Ibrahim, E.-D.S.; Moustafa, M.A.; El-Zayat, A.S.J.B. Isolation and Characterization of Bacillus Strains from Egyptian Mangroves: Exploring Their Endophytic Potential in Maize for Biological Control of Spodoptera frugiperda. 2024, 13, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, P.; Gogoi, S.; Deshpande, M.V.; Garg, P.; Bhuyan, R.P.; Altaf, N.; Saha, N.; Borah, S.M.; Phukon, M.; Tanti, N.J.M. Rhizospheric Bacillus spp. exhibit miticidal efficacy against oligonychus coffeae (Acari: tetranychidae) of tea. 2023, 11, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, F.; Wu, S.; Luo, X.; Bai, L.; Xia, Z.J.B. Microbial Community Structure in the Taklimakan Desert: The Importance of Nutrient Levels in Medium and Culture Methods. 2024, 13, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Queiroz, O.; Nyoike, T.W.; Koch, R.L.J.C.P. Baseline susceptibility to afidopyropen of soybean aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) from the north central United States. 2020, 129, 105020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesapogu, S.; Jillepalli, C.M.; Arora, D.K. Microbial DNA extraction, purification, and quantitation. In Analyzing microbes: manual of molecular biology techniques; Springer, 2012; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.-H.; Ha, S.-M.; Kwon, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, Y.; Seo, H. Chun JJIjos, microbiology e: Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. 2017, 67, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar]

- Coil, D.; Jospin, G.; Darling, A.E.J.B. A5-miseq: an updated pipeline to assemble microbial genomes from Illumina MiSeq data. 2014, 31, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S. Prjibelski ADJJocb: SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.J.; Abeel, T.; Shea, T.; Priest, M.; Abouelliel, A.; Sakthikumar, S.; Cuomo, C.A.; Zeng, Q.; Wortman, J. Young SKJPo: Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. 2014, 9, e112963. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Hu, D.; Jin, L.; Yang, S. Song BJJoss: Separation, interconversion, and insecticidal activity of the cis-and trans-isomers of novel hydrazone derivatives. 2013, 36, 602–608. [Google Scholar]

- CHAI Y-q, JIN Y-w, CHEN G-j, LIU Y-g, LI X-l, WANG G-eJASiC: Separation of insecticidal ingredient of Paecilomyces cicadae (Miquel) Samson. 2007, 6, 1352–1358.

- Koteshwara, A.; Philip, N.V.; Aranjani, J.M.; Hariharapura, R.C. Volety Mallikarjuna SJSR: A set of simple methods for detection and extraction of laminarinase. 2021, 11, 2489. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhu, H.-J.J.M. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)-based proteomics of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters. 2020, 25, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajlani, M.; Shiekh, A.; Hasnain, S.; Brantner, A.J.C. Purification of bioactive lipopeptides produced by Bacillus subtilis strain BIA. 2016, 79, 1527–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramasivam, M.; Selvi, C.J.J.o.E.; Studies, Z. Laboratory bioassay methods to assess the insecticide toxicity against insect pests-A review. 2017, 5, 1441–1445. [Google Scholar]

- Mnif, I.; Grau-Campistany, A.; Coronel-León, J.; Hammami, I.; Triki, M.A.; Manresa, A.; Ghribi, D.J.E.S.; Research, P. Purification and identification of Bacillus subtilis SPB1 lipopeptide biosurfactant exhibiting antifungal activity against Rhizoctonia bataticola and Rhizoctonia solani. 2016, 23, 6690–6699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochynek, M.; Lewińska, A.; Witwicki, M.; Dębczak, A. Łukaszewicz MJFiB, Biotechnology: Formation and structural features of micelles formed by surfactin homologues. 2023, 11, 1211319. [Google Scholar]

- Paliwal, D.; Hamilton, A.J.; Barrett, G.A.; Alberti, F.; Van Emden, H.; Monteil, C.L.; Mauchline, T.H.; Nauen, R.; Wagstaff, C.; Bass, C.J.M.B. Identification of novel aphid-killing bacteria to protect plants. 2022, 15, 1203–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Adeleke, B.S.; Akinola, S.A.; Fayose, C.A.; Adeyemi, U.T.; Gbadegesin, L.A.; Omole, R.K.; Johnson, R.M.; Uthman, Q.O.; Babalola, O.O.J.F.i.M. Biopesticides as a promising alternative to synthetic pesticides: A case for microbial pesticides, phytopesticides, and nanobiopesticides. 2023, 14, 1040901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Ahmad, I.; Ali, M.J.B.J.o.B. Biocontrol studies on rizpspheric microorganisms against black rot disease of tea caused by Corticium theae Bernard. 2018, 47, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-I.; Ajuna, H.B.; Won, S.-J.; Choub, V.; Kim, C.-W.; Moon, J.-H.; Ahn, Y.S.J.C.P. The insecticidal potential of Bacillus velezensis CE 100 against Dasineura jujubifolia Jiao & Bu (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) larvae infestation and its role in the enhancement of yield and fruit quality of jujube (Zizyphus jujuba Miller var. inermis Rehder). 2023, 163, 106098. [Google Scholar]

- Pappas, M.L.; Samaras, K.; Koufakis, I.; Broufas, G.D.J.A. Beneficial soil microbes negatively affect spider mites and aphids in pepper. 2021, 11, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpor, O.B.; Akinwusi, O.D.; Ogunnusi, T.A.J.H. Production, characterization and pesticidal potential of Bacillus species metabolites against sugar ant (Camponotus consobrinus). 2021; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiu L, Satta A, Floris I: Emerging entomopathogenic bacteria for insect pest management. 2013.

- Ma, X.; Hu, J.; Ding, C.; Portieles, R.; Xu, H.; Gao, J.; Du, L.; Gao, X.; Yue, Q.; Zhao, L.J.B.m. New native Bacillus thuringiensis strains induce high insecticidal action against Culex pipiens pallens larvae and adults. 2023, 23, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Azzazy, M.M.; Alsohim, A.S.; Yoder, C.E.J.A. Biological effects of three bacterial species on Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) infesting eggplant under laboratory and greenhouse conditions. 2020, 60, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.J.B.m. Lipopeptides from Bacillus velezensis ZLP-101 and their mode of action against bean aphids Acyrthosiphon pisum Harris. 2024, 24, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Munir, S.; Li, Y.; Ahmed, A.; He, P.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, P.; Wang, Z.; He, P.J.P.M.S. Bacillus subtilis YZ-1 surfactins are involved in effective toxicity against agricultural pests. 2024, 80, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).