1. Introduction

Salix, which is the largest genus within Salicaceae, comprises approximately 350 to 500 species worldwide [

1].

Salix are widely distributed across the temperate and frigid zone regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Extensive hybridization and genetic introgression among species have resulted in high genetic diversity and a complex evolutionary history. This makes

Salix an excellent model for studying plant genetic evolution [

2,

3,

4].

Subgenera and section are commonly used in the classification of

Salix. Based on the morphological characteristics of American willows, subg.

Salix and subg.

Vetrix were accepted [

5]. Argus conducted a cluster analysis based on phenotypes, dividing the 127 species of willows in the New World into four subgenera: subg.

Salix, subg.

Longifoliae, subg.

Chamaetia, and subg.

Vetrix. Later, the North American

Salix was divided into five subgenera: subg.

Salix, subg.

Protitea, subg.

Longifoliae, subg.

Chamaetia, and subg.

Vetrix [

6,

7]. With the development of bioinformatics, it is possible to study the genetic evolution of species based on genomic data. From the perspective of molecular systematics, it can reveal the real evolutionary relationship of species. In molecular phylogenetic studies,

Salix was a monophyletic group, clearly classified into two lineages. The internal topological structure of the two lineages was inconsistent. For example, Wu (2015), by analyzing nuclear ribosomal DNA external transcribed spacer (ETS), internal transcribed spacer (ITS), and four plastid markers, classified

Salix into two clades: one comprising subg.

Salix, subg.

Longifoliae, and subg.

Protitea, and the other including subg.

Chosenia, subg.

Pleuradenia, subg.

Chamaetia, and subg.

Vetrix, further supporting the merging of subg.

Chamaetia and subg.

Vetrix [

8]. Zhang (2018) used whole chloroplast genome sequences from 42 Salicaceae species to estimate divergence times, confirming that

Salix could be divided into two main clades: the

Chamaetia/

Vetrix clade and the

Salix clade [

9]. Sergey Gulyaev (2022) used whole-genome resequencing data to classifie

Salix into two main groups, namely the paraphyletic

Salix grade and the

Vetrix clade [

10]. The inconsistencies of phylogenetic relationships reveal the complex evolutionary history and high genetic divergence of

Salix.

Chloroplast genomes have been widely used in the study of genetic evolution due to their relatively conservative structure, abundant genetic information, moderate base substitution rate, and significant differences in molecular evolution rates between coding and non-coding regions. LSC and SSC regions usually had higher variation sites, because this region contains more protein-coding genes and non-coding interval sequences, especially functional genes related to photosynthesis and energy conversion, which are more susceptible to selection pressure [

11]. The

matK,

rbcL,

psbA,

ndhC,

ndhK,

accD in the LSC region and

ndhF,

ycf1,

ndhI in the SSC region had been all identified as rapidly evolving chloroplast genes [

12,

13,

14,

15]. In the comparative study of chloroplasts in

Salix, different sampling methods obviously influenced the results. For example, by comparing the chloroplast genome characteristics and interspecific variation of three shrub willows, it was found that the chloroplast genomes of three shrub willow species were highly similar [

16]. Three kinds of sand-fixing shrub willows were found and the non-coding and spacer regions of the chloroplast genome showed more variation than the coding regions [

17]. Zhou (2021) compared the chloroplast genomes of 21 species of willow plants and identified 7 positively selected genes, with different gene types identified for trees and shrubs [

18]. Current research on the chloroplast genomes of the

Salix genus predominantly focused on one or a limited number of species, often relying on comparative analyses of randomly collected samples. However, this approach falls short of fully capturing the variation patterns and evolutionary trends of chloroplast genomes within the genus.

To understand the evolutionary dynamics of the Salix. We developed a comprehensive framework by extensively sampling species of the Salix and constructing a phylogenetic tree based on chloroplast genomes. Based on the phylogenetic tree, studying the differences in chloroplast structure between different clades to understand the chloroplast genome evolution of Salix.

2. Results

2.1. Phylogenetic Analysis

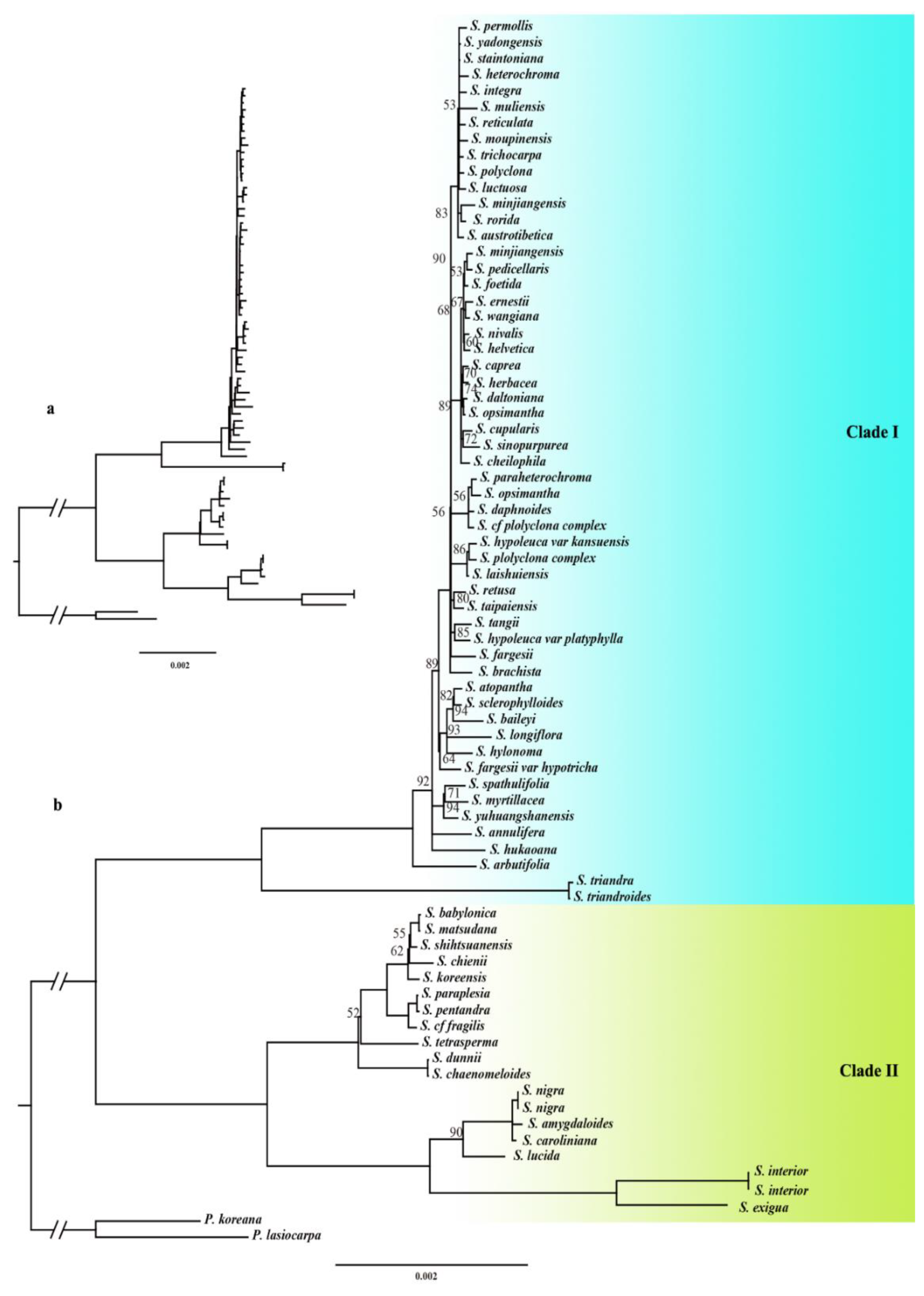

The results indicated that

Salix was a monophyletic group with strong support, showing a bootstrap support value of 100 and relatively low support within the internal branches. To better illustrate the structure of the phylogenetic tree, branches with bootstrap support values below 50 were merged. The phylogenetic tree classified

Salix into two main clades: Clade I and Clade II, and was consistent with previous studies (

Figure 1). The low internal branch support within the phylogenetic tree could be attributed to two main factors: (1) Chloroplast genomes were generally more conserved than nuclear genomes, resulting in fewer sequence variations and limited phylogenetic signal, thus reducing branch support; (2) Frequent hybridization within the genus had led to chloroplast capture phenomena.

The phylogenetic tree was divided into two clades (Clade I and Clade II). Clade I comprises species from the subg. Chamaetia and subg. Vetrix, while Clade II comprises species from subg. Salix, subg. Protitea and subg. Longifoliae. Two species are selected for each subgenus. In the Clade I branch, Salix luctuosa, Salix integra, Salix pedicellaris, and Salix nivalis were analyzed. In the Clade II branch, Salix babylonica, Salix matsudana, Salix caroliniana, Salix nigra, Salix interior, and Salix exigua were analyzed.

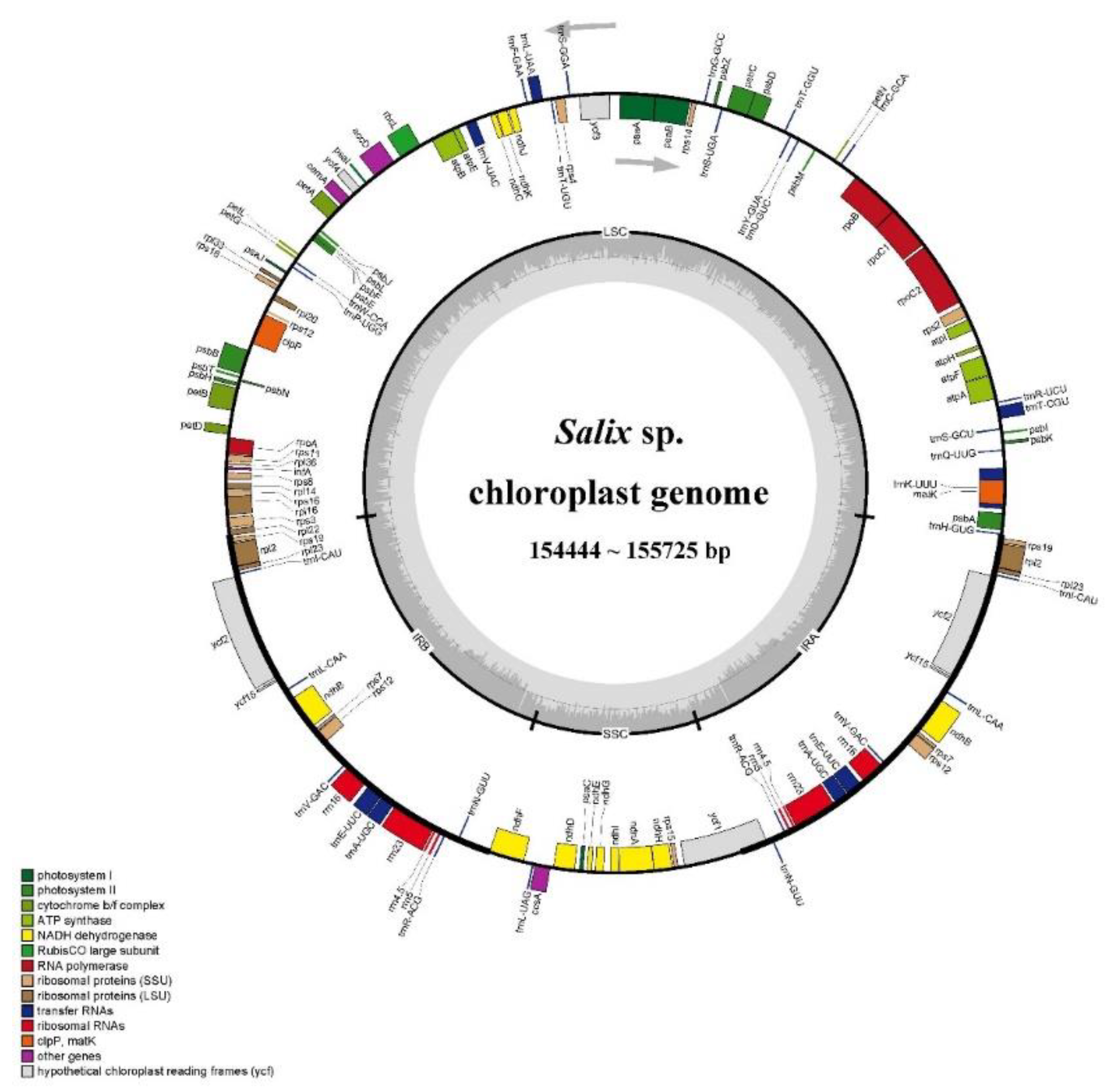

2.2. Chloroplast Genome Features

The chloroplast genomes of 10

Salix species exhibited a typical quadripartite structure, with lengths ranging from 154,444 to 155,725 bp, including IRa/b regions (54,336 to 54,924 bp), LSC regions (83,801 to 84,480 bp), and SSC regions (16,219 to 16,321 bp). A total of 131 genes were successfully annotated across the ten

Salix chloroplast genomes, including 88 protein-coding genes, 35 tRNA genes, and 8 rRNA genes (

Figure 2). These genes were involved in photosynthesis, replication, and several unknown functions. Notably, 18 genes, including 7 protein-coding genes (

ndhB,

rpl2,

rpl23,

rps12,

rps19,

rps7,

ycf2), 4 rRNA genes, and 7 tRNA genes, were duplicated in the inverted repeat regions (

Table S2).

When comparing chloroplast genome features between Clade I and Clade II, Clade I genomes ranged from 155,508 to 155,608 bp in size, with IR regions from 54,918 to 54,920 bp, LSC regions from 84,369 to 84,471 bp, and SSC regions from 16,219 to 16,221 bp. In contrast, Clade II genomes showed a wider variation, ranging from 154,444 to 155,725 bp, with IR regions from 54,336 to 54,924 bp, LSC regions from 83,801 to 84,480 bp, and SSC regions from 16,293 to 16,321 bp. The greater variation observed in Clade II may reflect gene deletions, pseudogene formation, or noncoding region expansion among different species or individuals. The prediction of GC content in the genome can significantly affect genomic function and species ecology, serving as an important indicator of species affinity [

40]. The GC content of the chloroplast genomes of 10

Salix species, as well as the LSC, SSC, and IR regions, ranged from 36.6% to 36.8%, 34.4% to 34.5%, 30.8% to 31%, and 41.7% to 42%, respectively (

Table S1). Although the variation is small, this may indicate that

Salix species underwent a relatively short or slow evolutionary process during differentiation.

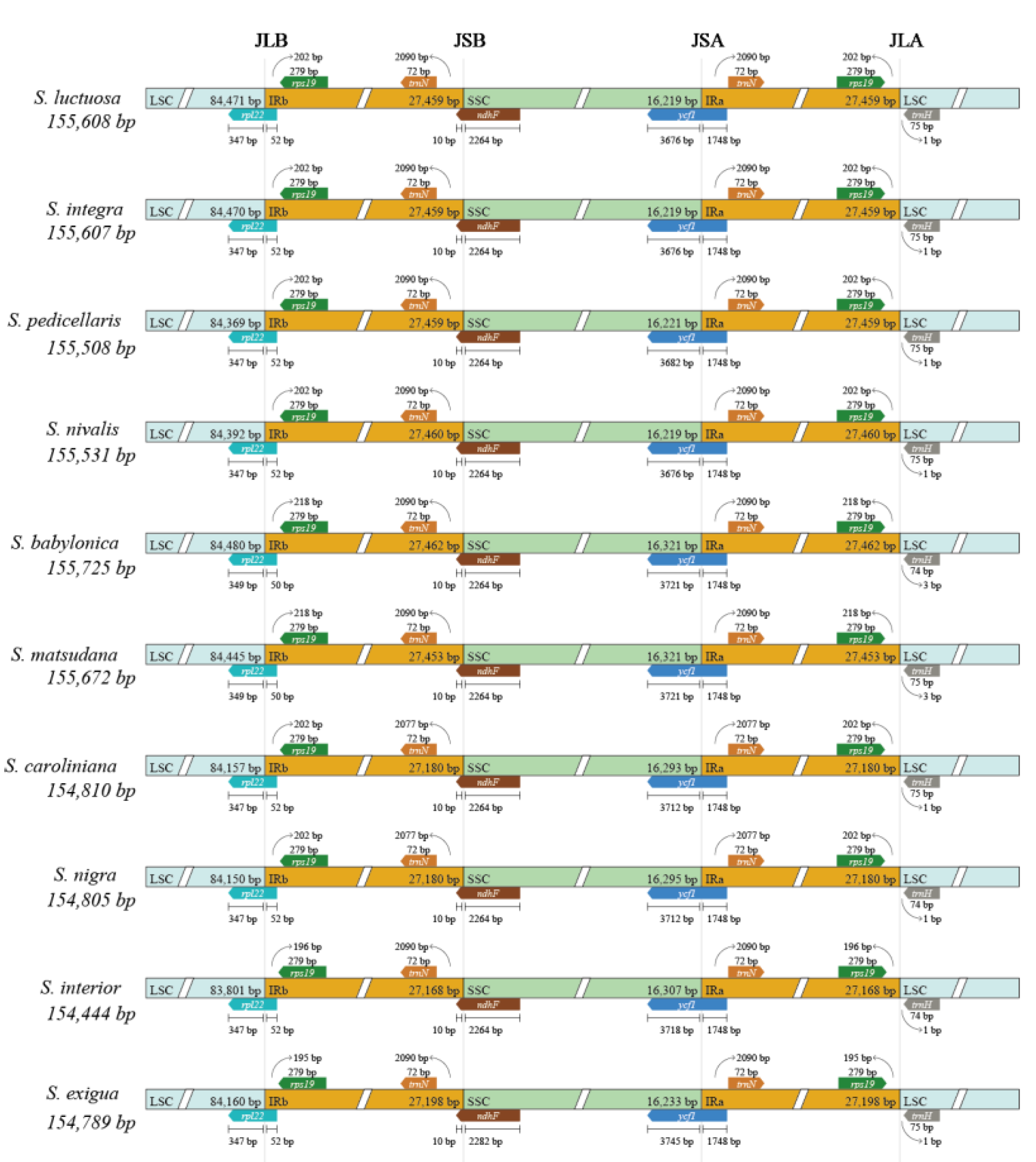

2.3. Comparative Analysis of Salix Chloroplast Genome

Boundary comparisons of the LSC, SSC, and IR regions using IRSCOPE revealed that the gene content at these boundaries was highly conserved, with minimal variation in gene length and boundary positioning among the ten species. For instance,

rpl22 and

rps19 genes were consistently located at the LSC/IRb boundary, while

trnN and

ndhF were present at the IRb/SSC boundary across all genomes examined. Both the SSC/IRa boundary are

ycf1 and

trnN genes, both the IRa/LSC boundary were

rps19 and

trnH genes, while the

rpl22 at the LSC/IRb boundary had only 2 bp variants, and the

ycf1 at the SSC/IRa boundary had only 69 bp differences (

Figure 3).

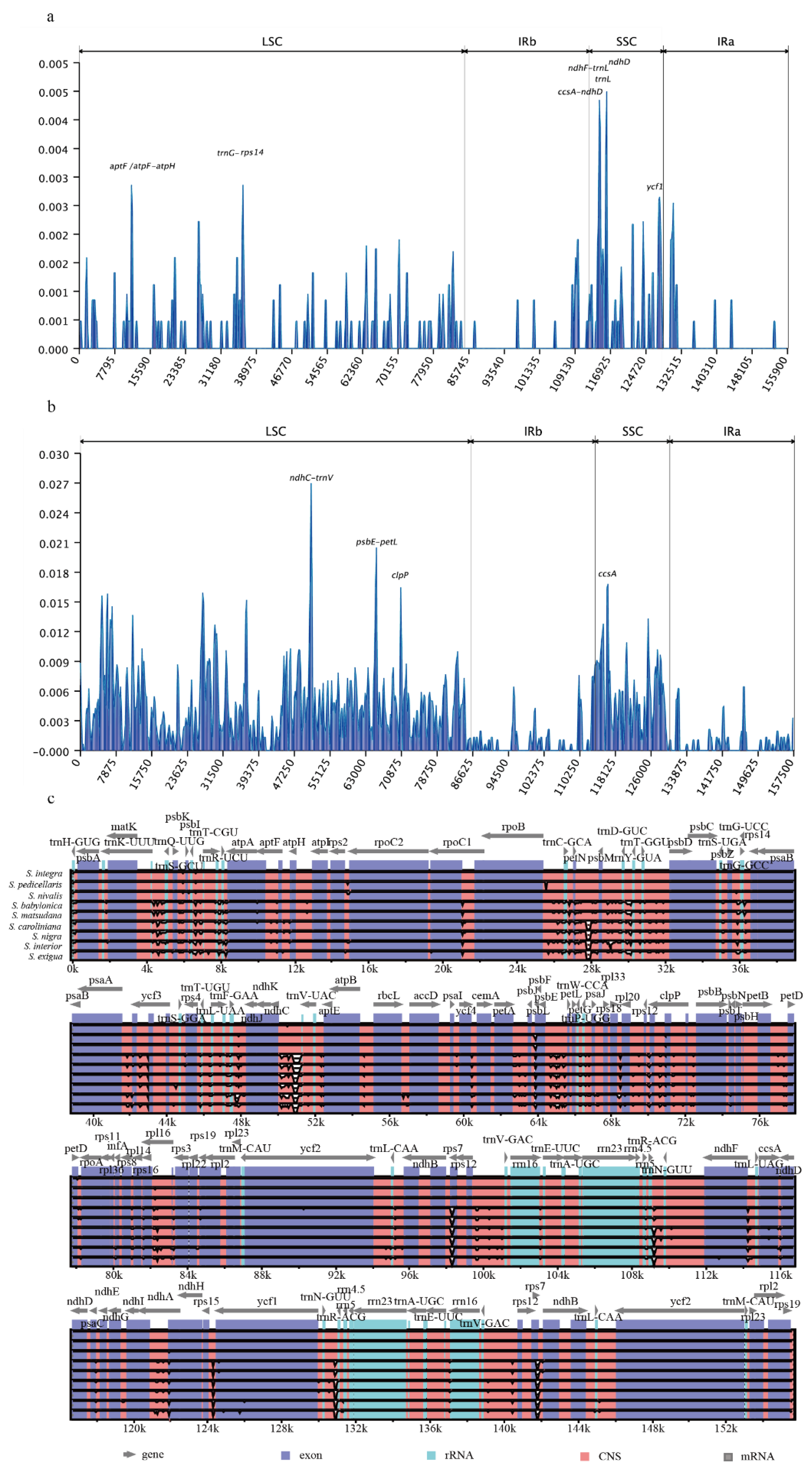

Variability estimation for the 10 sequenced chloroplast genomes was performed using mVISTA, with

Salix luctuosa as the reference. No major genome rearrangements or inversions were detected. Compared with the highly conserved coding regions, non-coding regions (intergenic spacers and introns) exhibited higher levels of variation (

Figure 4c). Sliding window analysis using DnaSP v6.0 revealed higher variation regions in the SSC region of the Clade I, including

ndhD,

ndhF-trnL,

trnL,

ccsA-ndhD,

ycf1,

aptF, and

aptF-rps14 (

Figure 4a). In Clade II, species exhibited higher variation in the LSC region, including

ndhC-trnV,

psdE-petL,

clpP and

ccsA (

Figure 4b).

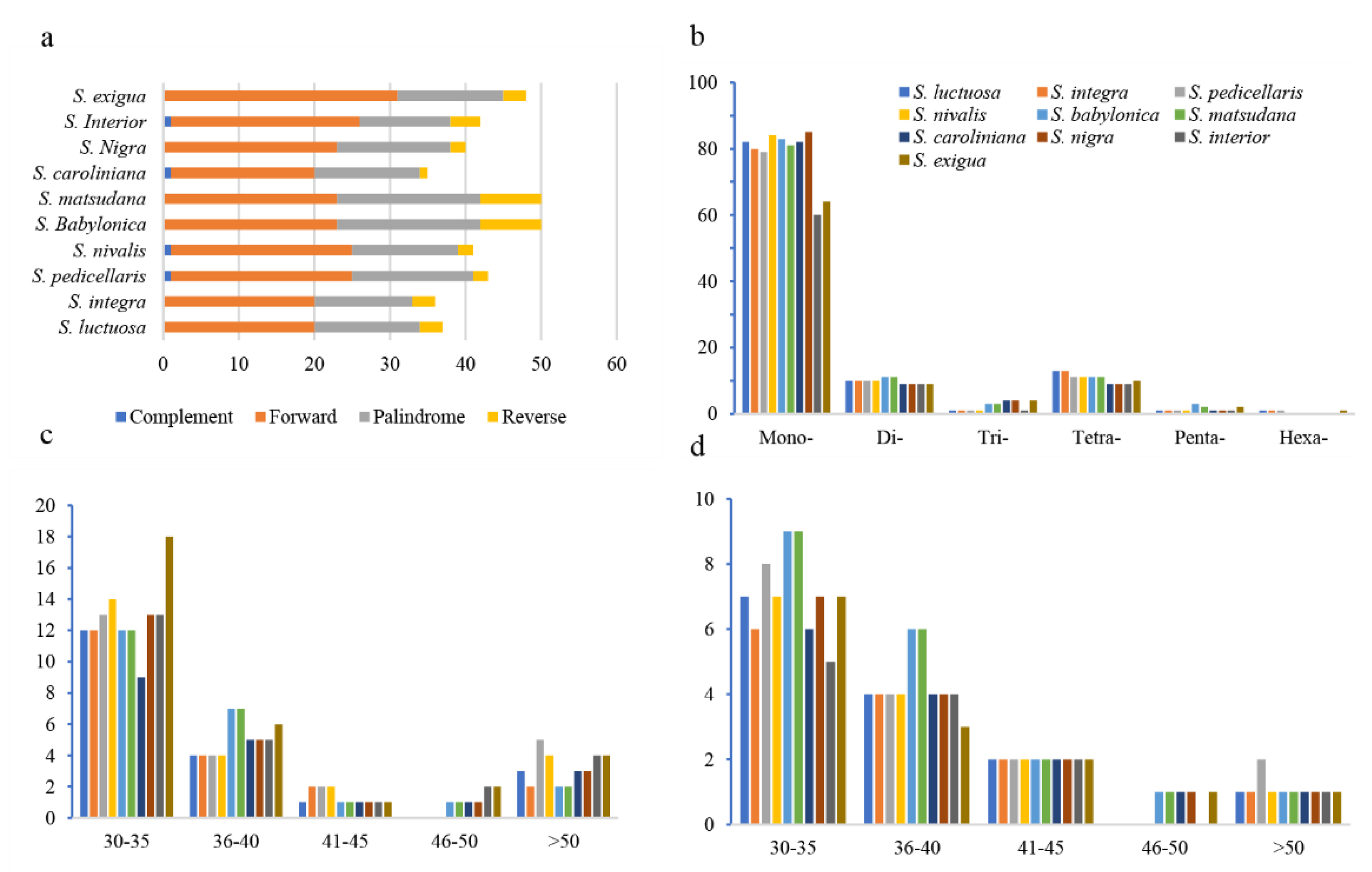

2.4. Result of Chloroplast Genome Repeat Sequences

In Clade I, each species contained 103-108 simple sequence repeats (SSRs), with mononucleotide repeats being the most abundant, accounting for 75.47% (

Salix integra) to 78.5% (

Salix nivalis) of the total (

Figure 5b). Each species had 36-43 long repeat sequences, with forward repeats being the most common, followed by palindromic and reverse repeats (

Figure 5a). In Clade II, each species contained 80-111 SSRs, with mononucleotide repeats being the most abundant, accounting for 71.11% (

Salix interior) to 78.7% (

Salix caroliniana) (

Figure 5b). Long repeat sequences ranged from 35-50 per species, with forward repeats being the most common, followed by palindromic and reverse repeats (

Figure 5a). The length of forward repetition and palindromic repetition is mainly concentrated in 30 ~ 35 bp (

Figure 5c-5d).

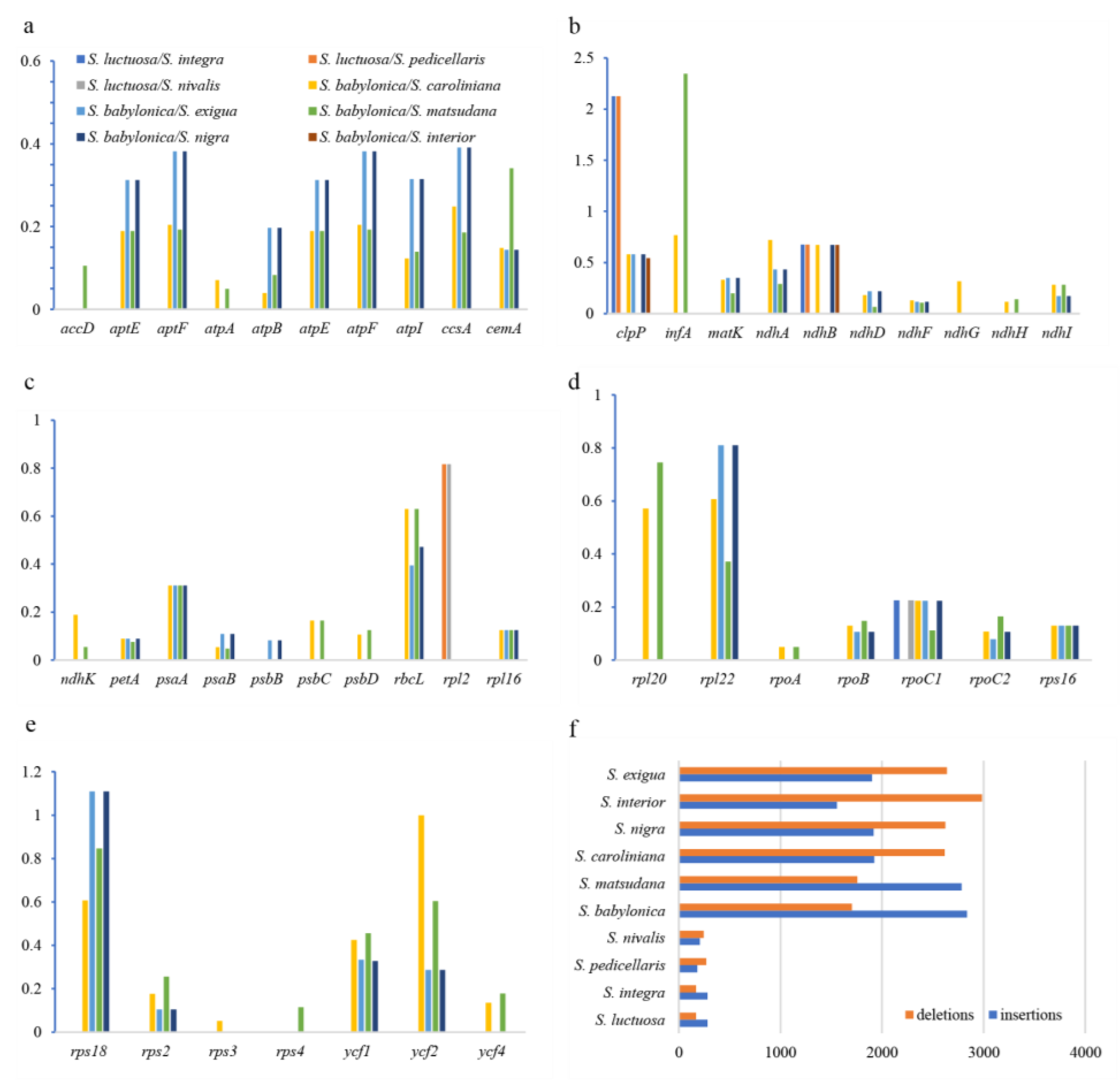

2.5. Result of InDel and Selection Pressure

Insertion and deletion (InDel) variations were identified in chloroplast genomes. In Clade I, the length of deletion sites ranged from 169 - 269 bp, and insertion sites ranged from 183 - 283 bp. In Clade II, deletion sites ranged from 1,703 - 2,984 bp, and insertion sites ranged from 1,556 - 2,837 bp, suggesting that Clade II is undergoing more rapid species divergence (

Figure 6f). Ka/Ks ratios were used to determine the selection pressure on protein-coding genes in

Salix. Four genes (

clpP,

ndhB,

rpoC1,

rpl2) were found in the Clade I branch, with Ka/Ks ratios ranging from 0.22 - 2.127, and the Ka/Ks ratio of the

clpP gene is greater than 1. These four genes are mainly related to protease synthesis, photosynthesis, and self-replication functions. In Clade II, 44 genes were found, with Ka/Ks ratios ranging from 0.03 - 2.34, and only the Ka/Ks ratios of the

rps18 and

infA genes were greater than 1 (

Figure 6a-e). This gene is mainly related to self-replication functions. These results indicated that under different selective pressures, the protein-coding genes between the two clades were undergoing different evolutionary processes.

3. Discussion

3.1. Phylogenetic Relationships Among the Salix

Studies utilizing genomic fragments, plastid genomes, and re-sequencing data consistently indicated that

Salix can be classified into two main clades: Clade I and Clade II. The results of our study were consistent with previous molecular phylogenetic research [

8,

19,

20]. The findings support the results of Gulyaev [

10], and do not support the results of Ogutcen [

21]. Ogutcen’s study classified

Salix into subg.

Chamaetia/

Vetrix and subg.

Salix s.l.. Chen supported the classification of

Salix into five subgenera: subg.

Salix, subg.

Urbaniana, subg.

Triandrae, subg.

Longifoliae, and subg.

Vetrix [

22]. This study strongly suggested the monophyly of subg.

Chamaetia/

Vetrix, subg.

Longifoliae and subg.

Protitea.

The reticulate evolution caused by hybridization, introgression and lineage sorting may be an explanation for the molecular phylogenetic incongruence [

23]. Hybridization may lead to the creation of new gene combinations, enhancing progeny adaptability to diverse environments and promoting the accumulation of genetic diversity [

24,

25]. Nuclear genes, during frequent hybridization, can produce different evolutionary directions and diverse variation regions. The phylogenetic relationship of

Salix is complex, and the internal topological structure cannot be solved by using only chloroplast data [

26,

27]. Our results only reflected the evolutionary relationship of

Salix in terms of the chloroplast genome. Future studies will require nuclear genetic data on parental inheritance and more complete species sampling to resolve this

Salix phylogenetic relationship.

3.2. Chloroplast Genome Differences Between Two Lineages of Salix

The structure and variation of Salix chloroplast genomes were compared, and the results showed significant differences between Clades I and Clades II. In Clade II, species from North America formed a subclade, while species from East Asia formed another subclade. The overall variation in chloroplast structure was greater in Clade II, likely due to (1) genetic differentiation driven by geographic isolation, leading to the accumulation of chloroplast genome variations, (2) historical biogeographic events, such as glacial isolation, resulting in species being trapped in refugia, and subsequent post-glacial dispersal leading to unique genomic features, and (3) chloroplast capture through hybridization between North American and East Asian species.

Nucleotide diversity analysis showed that the IR regions were more conserved compared with the LSC and SSC regions, likely due to sequence homogenization through gene conversion and the role of IR regions in maintaining genomic stability [

28,

29]. In Clade I, the SSC region showed the highest nucleotide diversity, while in Clade II, the LSC region showed the highest nucleotide diversity. Whether these highly divergent regions or genes can be used for phylogenetic analysis of related

Salix species or as potential molecular markers in population genetic studies requires further investigation.

SSRs in chloroplast genomes are important molecular markers due to their abundance and high polymorphism, and they were widely used in studies of genetic diversity, species evolution, and conservation biology [

30,

31]. In both Clade I and Clade II, SSRs and long repeats did not show significant differences, with A/T mononucleotide repeats being dominant, a feature common in other plant lineages [

32]. The identified long repeats, especially forward and palindromic repeats, suggest their involvement in promoting structural variation and plastid stability. Insertions and deletions (InDels) are critical types of genomic variation that can influence genome size and thus affect species evolution [

33,

34]. To evaluate structural changes in

Salix chloroplast genomes during evolution, we calculated the length of InDels for Clade I and Clade II. The insert lengths in Clade I ranged from 183 to 283 bp, while the deletion lengths ranged from 169 to 269 bp. In Clade II, insert lengths ranged from 1,556 to 2,837 bp, and deletion lengths ranged from 1,703 to 2,984 bp. The structural variation in Clade II chloroplast genomes was significantly higher than that of Clade I, indicating a higher evolutionary rate in Clade II species.

The Ka/Ks ratio is correlated with gene adaptive evolution. Nonsynonymous substitutions in plant genomes can cause amino acid changes, leading to protein function alterations that enable species to adapt to new habitats, while synonymous substitutions do not change protein composition [

35]. The Ka/Ks ratio was used to infer gene selection types. Most genes in plants have Ka/Ks values less than 1, because nonsynonymous substitutions are generally disadvantageous, with only a few genes showing positive selection [

36,

37]. When the Ka/Ks ratio is greater than 1, these genes are under rapid positive selection in the current environment, which is significant for species adaptation to new conditions. In Clade I, four genes were identified (

clpP,

ndhB,

rpoC1, and

rpl2), with only the Ka/Ks ratio of the

clpP gene being greater than 1. In Clade II, 44 genes were identified, with only the Ka/Ks ratios of the

rps18 and

infA genes being greater than 1. Clade II has more genes with evolutionary signals, possibly because Clade II species live in more ecological niches or more complex environmental conditions, requiring stronger adaptability. Therefore, their genomes may have undergone more environmental selection. This environmental selection is often a key driving factor for the rapid formation and expansion of species.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material, DNA Extraction, and Genome Sequencing

Following Argus’s (2010) five-subgenus classification system, we collected 76 species of

Salix in the study. Species already included subg.

Salix, subg.

Protitea, subg.

Longifoliae, subg.

Chamaetia, and subg.

Vetrix. Detailed information on the species is provided in

Table S3. Genomic DNA was extracted from leaf samples using a modified CTAB method [

38]. DNA quality and concentration were assessed using a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) and a NanoDrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Qualified DNA samples were fragmented, and sequencing libraries (insert size of 350 bp) were constructed. Sequencing was performed on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform, generating approximately 5 Gb of data per sample.

4.2. Chloroplast Genome Assembly and Annotation

Initial quality control of raw sequencing data was performed using Trimmomatic v0.39 [

39]. Clean, high-quality reads were used for de novo assembly of the chloroplast genome using GetOrganelle v1.7.5 [

40]. For incomplete assemblies, manual assembly was performed using Geneious Prime v2020 [

41]. Chloroplast genome annotation was conducted using Plastid Genome Annotator Version 3 (PGA), with reference genomes

Salix annulifera (GenBank: MZ365447) and

Salix foetida (GenBank: MZ435429). Manual corrections were made in Geneious Prime, and the final chloroplast genome map was generated using the OGDRAW online tool [

42].

4.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic relationships within

Salix were reconstructed based on complete chloroplast genome sequences, with

Populus koreana (GenBank: MW376789) and

Populus lasiocarpa (GenBank: KX641589) used as outgroups. Detailed data of species are shown in

Table S4. Sequence alignment was conducted using MAFFT with default parameters [

43]. After alignment, trimAl v1.4.1 was used to filter unreliable alignment regions [

44]. The best substitution model was selected using ModelFinder v1.5.4. Finally, a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was constructed using RAxML v7.4.2 with the GTRGAMMA model, employing 1000 rapid bootstrap replicates.

4.4. Chloroplast Genome Structural Comparison

The structural comparison of ten

Salix chloroplast genomes was performed using the mVISTA program (

https://genome.lbl.gov/vista/mvista/submit.shtml) with the Shuffle-LAGAN model. The boundaries of LSC, IRb, SSC, and IRa regions were compared using IRscope (

https://genome.lbl.gov/vista/mvista/submit.shtml). After aligning sequences of Clade I using Mafft v7.313, nucleotide diversity (Pi) was calculated using sliding window analysis in DnaSP v6.0, with a window length of 600 bp and a step size of 200 bp. The nucleotide diversity (Pi) of Clade II selected

Salix babylonica as a reference, and the method was the same as above. After aligning all sequences using Mafft v7.313, the insertion and deletion (InDels) site length for each species was calculated based on R. In Clade I,

Salix luctuasa was used for the reference sequence, and in Clade II,

Salix babylonica was used for the reference sequence. The method was the same as above.

4.5. Analysis of Repeat Sequences and SSRs

Repeat sequences in the chloroplast genomes were analyzed using the REPuter program, identifying four types of long repeats: forward, reverse, palindromic, and complementary repeats. The parameters were set as follows: repeat similarity greater than 90%, minimum repeat size of 30 bp, and a Hamming distance of 3. Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were identified using MISA (

https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer), and six types of SSRs (mononucleotide, dinucleotide, trinucleotide, tetranucleotide, pentanucleotide, and hexanucleotide) were analyzed, with repeat thresholds set to 10, 5, 4, 4, 4, and 3, respectively.

4.6. Analysis of Gene Selection Pressure

In Clade I, the coding sequences and protein sequences from

Salix luctuosa were extracted, and the protein sequences of other species were compared with

Salix luctuosa using blastn (2.10.1) to find the best matches, thereby obtaining homologous protein sequences. Use the Mafft (v7.427) software to automatically align the homologous protein sequences. Use a Perl script to map the aligned protein sequences to the coding sequences, thereby obtaining the aligned coding sequences. Use Ka/Ks_Calculator2 to calculate the Ka/Ks values [

45]. Clade II selects

Salix babylonica as the reference, using the same method as above.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1. Chloroplast genome features; Table S2. Gene composition in the chloroplast genomes of Salix sp.; Table S3 Details of the sampling information in this study; Table S4 Samples downloaded from NCBI GenBank for phylogenetic analyses; Table S5 The number and types of simple repeat sequences (SSRs) in the chloroplast genomes of ten Salix species; Table S6 The length and types of Repeat sequences in the chloroplast genomes of ten Salix species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, and project administration, C.S. and Z.Z.; methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, and data curation, F.Y., L.Z. and X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, and supervision, F.Y., C.S. and Z.Z.; funding acquisition, C.S. and Z.Z.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Technology Basic Resources Investigation Program of China (grant no. 2022FY202200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 32001247), and the second comprehensive scientific expedition to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (grant no. 2019QZKK0502).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The chloroplast genome of Salix is deposited in the GenBank database under the following accession number:

Acknowledgments

In this study, we thank for Dr. Jana Vamosi, who comes from the University of Calgary. He provided us with specimens of Salix from North America.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tawfeek, Nora, Mona F Mahmoud, Dalia I Hamdan, Mansour Sobeh, and Assem M El-Shazly. “Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Medicinal Uses of Plants of the Genus Salix: An Updated Review.” Frontiers in Pharmacology 12 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Keoleian, Gregory A., and Timothy A. Volk. “Renewable Energy from Willow Biomass Crops: Life Cycle Energy, Environmental and Economic Performance.” Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 24, no. 5-6 (2005): 385-406.

- Myers-Smith, I. H., B. C. Forbes, and M. Wilmking. “Shrub Encroachment in Arctic and Alpine Tundra: Dynamics, Impacts and Research Priorities.” Environmental Research Letters 6 (2011): 1-15.

- Mohsin, Muhammad, Mir Md Abdus Salam, Nicole Nawrot, Erik Kaipiainen, Daniel J. Lane, Ewa Wojciechowska, Niko Kinnunen, Mikko Heimonen, Arja Tervahauta, and Sirpa Peraniemi. “Phytoextraction and Recovery of Rare Earth Elements Using Willow (Salix Spp.).” Science of the Total Environment, no. 809- (2022): 809. [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Robert D. “A Synopsis of American Salix.” Canadian Journal of Botany 54: 2769–2789 (1976).

- Argus, George W. “Infrageneric Classification of Salix (Salicaceae) in the New World.” Systematic Botany Monographs 52: 1–121 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Argus, George W. . Salix. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, Eds. Flora of North America North of Mexico. . Vol. 7: 23–51. New York: Oxford University, 2010.

- Wu, J., T. Nyman, D. C. Wang, G. W. Argus, Y. P. Yang, and J. H. Chen. “Phylogeny of Salix Subgenus Salix S.L. (Salicaceae): Delimitation, Biogeography, and Reticulate Evolution.” BMC Evol Biol 15 (2015): 31.

- Zhang, L., Z. Xi, M. Wang, X. Guo, and T. Ma. “Plastome Phylogeny and Lineage Diversification of Salicaceae with Focus on Poplars and Willows.” Ecol Evol 8, no. 16 (2018): 7817-23. [CrossRef]

- Gulyaev, S., X. J. Cai, F. Y. Guo, S. Kikuchi, W. L. Applequist, Z. X. Zhang, E. Horandl, and L. He. “The Phylogeny of Salix Revealed by Whole Genome Re-Sequencing Suggests Different Sex-Determination Systems in Major Groups of the Genus.” Ann Bot 129, no. 4 (2022): 485-98. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Xiaoxing, Shihong Sheng, Qi Xu, Rihui Lu, Chuan Chen, Huiming Peng, and Chen Feng. “Structure and Features of the Complete Chloroplast Genome of Salix Triandroides (Salicaceae).” Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 36, no. 1 (2022): 148-58.

- Meucci, S., L. Schulte, H. H. Zimmermann, K. R. Stoof-Leichsenring, L. Epp, P. Bronken Eidesen, and U. Herzschuh. “Holocene Chloroplast Genetic Variation of Shrubs (Alnus Alnobetula, Betula Nana, Salix Sp.) at the Siberian Tundra-Taiga Ecotone Inferred from Modern Chloroplast Genome Assembly and Sedimentary Ancient DNA Analyses.” Ecol Evol 11, no. 5 (2021): 2173-93.

- Moore, M. J., A. Dhingra, P. S. Soltis, R. Shaw, W. G. Farmerie, K. M. Folta, and D. E. Soltis. “Rapid and Accurate Pyrosequencing of Angiosperm Plastid Genomes.” BMC Plant Biol 6 (2006): 17. [CrossRef]

- Wicke, Susann, Gerald M. Schneeweiss, Claude W. dePamphilis, Kai F. Müller, and Dietmar Quandt. “The Evolution of the Plastid Chromosome in Land Plants: Gene Content, Gene Order, Gene Function.” Plant Molecular Biology 76, no. 3-5 (2011): 273-97.

- Fajri, Hayatul, A. R. I. Sunandar, and Mahwar Qurbaniah. “Phylogenetic Analysis of Wild Bananas (Musa Spp.) in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, Based on Maturase K (Matk) Genes.” Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity 25, no. 8 (2024).

- Zhang, Xue-Jiao, Kang-Jia Liu, Ya-Chao Wang, Jian He, Yuan-Mi Wu, and Zhi-Xiang Zhang. “Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Three Salix Species: Genome Structures and Phylogenetic Analysis.” Forests 12, no. 12 (2021).

- Lu, Dongye, Haiguang Huang, Lei Zhang, Lei Hao, and Guosheng Zhang. “Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Three Sand-Fixing Salix Shrubs from Northwest China: Comparative and Phylogenetic Analysis and Interspecific Identification.” Trees 37, no. 3 (2023): 849-61. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Z. Jiao, J. Guo, B. S. Wang, and J. Zheng. “Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequencing of Five Salix Species and Its Application in the Phylogeny and Taxonomy of the Genus.” Mitochondrial DNA B Resour 6, no. 8 (2021): 2348-52. [CrossRef]

- Azuma, Takayuki, Tadashi Kajita, Jun Yokoyama, and Hiroyoshi Ohashi. “Phylogenetic Relationships of Salix (Salicaceae) Based on Rbcl Quence Data.” American Journal of Botany 87, no. 1 (2000): 67-75.

- Hardig, T. M., C. K. Anttila, and S. J. Brunsfeld. “A Phylogenetic Analysis of Salix (Salicaceae) Based on Matk and Ribosomal DNA Sequence Data.” Journal of Botany 2010 (2010): 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Ogutcen, E., P. de Lima Ferreira, N. D. Wagner, P. Marincek, J. Vir Leong, G. Aubona, J. Cavender-Bares, J. Michalek, L. Schroeder, B. E. Sedio, R. J. Vasut, and M. Volf. “Phylogenetic Insights into the Salicaceae: The Evolution of Willows and Beyond.” Mol Phylogenet Evol 199 (2024): 108161. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Kai-Yun, Jin-Dan Wang, Rui-Qi Xiang, Xue-Dan Yang, Quan-Zheng Yun, Yuan Huang, Hang Sun, and Jia-Hui Chen. “Backbone Phylogeny of Salix Based on Genome Skimming Data.” Plant Diversity (2024). [CrossRef]

- Mallet, J. “Hybridization as an Invasion of the Genome.” Trends Ecol Evol 20, no. 5 (2005): 229-37. [CrossRef]

- Seehausen, O. “Hybridization and Adaptive Radiation.” Trends Ecol Evol 19, no. 4 (2004): 198-207. [CrossRef]

- Petit, Rémy J., and Giovanni G. Vendramin. “Plant Phylogeography Based on Organelle Genes: An Introduction.” In Phylogeography of Southern European Refugia, 23-97, 2007.

- Fontaine, M. C., J. B. Pease, A. Steele, R. M. Waterhouse, D. E. Neafsey, I. V. Sharakhov, X. Jiang, A. B. Hall, F. Catteruccia, E. Kakani, S. N. Mitchell, Y. C. Wu, H. A. Smith, R. R. Love, M. K. Lawniczak, M. A. Slotman, S. J. Emrich, M. W. Hahn, and N. J. Besansky. “Mosquito Genomics. Extensive Introgression in a Malaria Vector Species Complex Revealed by Phylogenomics.” Science 347, no. 6217 (2015): 1258524. [CrossRef]

- Birky, C. W., Jr. “The Inheritance of Genes in Mitochondria and Chloroplasts: Laws, Mechanisms, and Models.” Annu Rev Genet 35 (2001): 125-48.

- Palmer, J. D., and W. F. Thompson. “Rearrangements in the Chloroplast Genomes of Mung Bean and Pea.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78, no. 9 (1981): 5533-7. [CrossRef]

- Guisinger, M. M., J. V. Kuehl, J. L. Boore, and R. K. Jansen. “Extreme Reconfiguration of Plastid Genomes in the Angiosperm Family Geraniaceae: Rearrangements, Repeats, and Codon Usage.” Mol Biol Evol 28, no. 1 (2011): 583-600.

- Song, Y., Y. Chen, J. Lv, J. Xu, S. Zhu, M. Li, and N. Chen. “Development of Chloroplast Genomic Resources for Oryza Species Discrimination.” Front Plant Sci 8 (2017): 1854. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D., S. Sun, X. Shan, and W. Wang. “Inbreeding Evaluation Using Microsatellite Confirmed Inbreeding Depression in Growth in the Fenneropenaeus Chinensis Natural Population.” Front Genet 14 (2023): 1077814. [CrossRef]

- Kohler, M., M. Reginato, T. T. Souza-Chies, and L. C. Majure. “Insights into Chloroplast Genome Evolution across Opuntioideae (Cactaceae) Reveals Robust yet Sometimes Conflicting Phylogenetic Topologies.” Front Plant Sci 11 (2020): 729. [CrossRef]

- Shaw., Joey, Edgar B. Lickey., John T. Beck., Susan B. Farmer., Wusheng Liu., Jermey Miller., Kunsiri C. Siripun., Charles T. Winder., Edward E. Schilling., and Randall L. Small. “The Tortoise and the Hare Ii: Relative Utility of 21 Noncoding Chloroplast DNA Sequences for Phylogenetic Analysis.” American Journal of Botany (2005). [CrossRef]

- Köhler., Matias, Marcelo Reginato., Tatiana Teixeira Souza-Chies., and Lucas C. Majure. “Insights into Chloroplast Genome Evolution across Opuntioideae (Cactaceae) Reveals Robust yet Sometimes Conflicting Phylogenetic Topologies.” Frontiers in Plant Science (2020). [CrossRef]

- Wright, S. I., and B. S. Gaut. “Molecular Population Genetics and the Search for Adaptive Evolution in Plants.” Mol Biol Evol 22, no. 3 (2005): 506-19. [CrossRef]

- Wong, W. S., Z. Yang, N. Goldman, and R. Nielsen. “Accuracy and Power of Statistical Methods for Detecting Adaptive Evolution in Protein Coding Sequences and for Identifying Positively Selected Sites.” Genetics 168, no. 2 (2004): 1041-51. [CrossRef]

- Clark, R. M., G. Schweikert, C. Toomajian, S. Ossowski, G. Zeller, P. Shinn, N. Warthmann, T. T. Hu, G. Fu, D. A. Hinds, H. Chen, K. A. Frazer, D. H. Huson, B. Scholkopf, M. Nordborg, G. Ratsch, J. R. Ecker, and D. Weigel. “Common Sequence Polymorphisms Shaping Genetic Diversity in Arabidopsis Thaliana.” Science 317, no. 5836 (2007): 338-42. [CrossRef]

- Li, Jinlu, Shuo Wang, Jing Yu, Ling Wang, and Shiliang Zhou. “A Modified Ctab Protocol for Plant DNA Extraction.” Acta Botanica(Chinese periodical) (2013).

- Jin, Jian-Jun, Wen-Bin Yu, Jun-Bo Yang, Yu Song, Claude W. dePamphilis, Ting-Shuang Yi, and De-Zhu Li. “Getorganelle: A Fast and Versatile Toolkit for Accurate De Novo Assembly of Organelle Genomes.” Genome Biology 21, no. 1 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Kearse, Matthew, Richard Moir, Amy Wilson, Steven Stones-Havas, Matthew Cheung, Shane Sturrock, Simon Buxton, Alex Cooper, Sidney Markowitz, Chris Duran, Tobias Thierer, Bruce Ashton, Peter Meintjes, and Alexei Drummond. “Geneious Basic: An Integrated and Extendable Desktop Software Platform for the Organization and Analysis of Sequence Data.” Bioinformatics 28, no. 12 (2012): 1647-49. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Xiao-Jian, Michael J. Moore, De-Zhu Li, and Ting-Shuang Yi. “Pga: A Software Package for Rapid, Accurate, and Flexible Batch Annotation of Plastomes.” Plant Methods 15, no. 1 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Greiner, Stephan, Pascal Lehwark, and Ralph Bock. “Organellargenomedraw (Ogdraw) Version 1.3.1: Expanded Toolkit for the Graphical Visualization of Organellar Genomes.” Nucleic Acids Research 47, no. W1 (2019): W59-W64. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K., and D. M. Standley. “Mafft Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 30, no. 4 (2013): 772-80. [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, Salvador, José M. Silla-Martínez, and Toni Gabaldón. “Trimal: A Tool for Automated Alignment Trimming in Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analyses.” Bioinformatics 25, no. 15 (2009): 1972-73. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Zhang, Jun Li, Xiao-Qian Zhao, Jun Wang, Gane Ka-Shu Wong, and Jun Yu. “Kaks_Calculator: Calculating Ka and Ks through Model Selection and Model Averaging.” Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 4, no. 4 (2006): 259-63. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).