1. Introduction

Pollarding is a specific coppice system whereby resprouts originate from artful cuts performed two or more meters above ground level [

1]. The main reason for pollarding is to train the new sprouts above the reach of livestock, which can be introduced to the same field right after harvest without any risk for browsing damage [

2]. For centuries, pollarding has been one of the most popular strategies of European agroforestry [

3,

4] and represented a key element of subsistence farming [

5].

Pollarding is a very ancient practice: its origins have been traced to the development of traditional animal husbandry, approximately 4000 years ago in the mountains of northern Iran [

6]. Pollarding was devised as a strategy for the effective combination of livestock farming and wood production [

7], and its success can be judged by its rapid spread and prolonged use [

8]. In many cases, pollards became a characterizing element of the cultural landscape, as witnessed by such famous masterpiece as “Landscape with Pollard Willows” painted by V. Van Gogh in 1882. Until the last decades, pollards remained a common sight in places as far apart as the Basque country, the Pyrenees, Sicily and Crete [

9,

10]. Then, with the general transition towards industrial agriculture, pollarding suffered a rapid and steady decline, reaching the brink of extinction in the last 20 years [

4].

However, even industrial agriculture may fall behind the increasingly complex requirements of economic development, which now places multiple competing demands on the agrarian landscape: food security, energy production and a whole range of ecosystem services [

11]. As a result, the integration of trees and agriculture is regaining interest as a viable agroecological solution to sustainable intensification [

12]. Obviously, the old systems must be adapted to the new goals and methods of modern societies, but a major revival of agroforestry is within reach…

A key factor for the successful integration of trees and conventional agriculture is canopy management, given that the crowns of maturing trees will progressively cover the underlying agricultural crops, eventually suppressing them. In that case, pollarding can be used to restore light availability [

13], thus offering an essential contribution to the development of modern, efficient and ultimately sound agroforestry systems [

14]. The eventual revival of pollarding as a modern coppicing technique depends on the capacity of developing new work methods that can match the current high requirements for work safety and cost-effectiveness [

15]. Traditional methods based on manual work are unable to match those requirements: cutting large branches while perched on a ladder is neither fast nor safe. Mechanization represents the only solution, which may come in the shape of a conventional feller-buncher, that is: a tree cutting device mounted on the tip of a mechanical boom. The simplest such machine consists of a tracked excavator equipped with a shear or a saw head. The introduction of such machine offers three main advantages. First, it makes work safe, because the operator sits comfortably inside a safety cab, protected against the risk of falling stems and of falling himself; second, it makes work much more productive, because the time to cut a branch is dramatically reduced, and the wood can be cut and stacked at once using the mechanical boom; third, it enables pollarding trees higher than two meters, because cutting height is not limited to the reach of a small ladder. A mechanical boom can extend at least 6 m above ground level, so that topping the tree at a height of 5 m is relatively easy. By extending cut height one can add a further product to the mix: the tree trunk, from which one can obtain valuable timber when the pollards are renewed. Timber production is a strategic goal of the European Union, and the new pollarding systems would then contribute to it [

16].

Such new system is now being tested on fast-growing poplar tree plantations, where the intercropping of poplar and cereals (rice or wheat) is common practice [

17]. This new pollarded variant has been installed at several experimental farms, with a view to pollarding the poplars every four years, then cutting at the base between the 12th and the 16th year, and replanting [

18].

The goal of this study was to obtain science-based data on mechanized pollarding, performed at a height of 5 m with modern excavator-based feller-bunchers. In particular, we wanted to determine the productivity, the cost and the work quality achieved by the two main technologies available on the market, namely: shear and disc saw. The hypothesis underlining the technology comparison is that of no significant difference in the productivity, cost and work quality between shears and disc saw (null hypothesis).

2. Materials and Methods

A two-day trial was conducted on December 16-17, 2021. The trial was conducted in the Sasse Rami farm, located in Ceregnano near Rovigo, an area with a long tradition in poplar farming, and especially suited to it (

Figure 1). The farm was owned by the Regional Authority for Veneto and managed by Veneto Agricoltura, the regional agency for farming research and extension.

The plot marked for the experiment was placed near the farm center (45°03’05.92” N; 11° 52’ 49.90” E); it measured 0.22 ha and contained 121 poplar trees, set at a spacing of 3 m x 6 m. The plantation had been established in 2014 with 2-years old cuttings of the hybrid clone I-214, one the oldest and most widespread. The poplars formed three parallel rows with a length of approximately 130 m each; the rows were divided into two equal segments, and three half rows were assigned to each of the two technologies, in an alternate pattern. That is: on the first row, the shear took the half nearer to the access, while the disc took the other half; on the second row the order was reversed; on the third row the order was repeated as for the first row. That arrangement was considered as the best solution for an even spread of eventual site gradients, while mitigating the error possibly introduced by the overly complex operational environment that would have been created by a purely randomized design.

The two technologies on test were: a 22-ton tracked excavator fitted with a double-blade shear head, and a 13-ton tracked excavator fitted with a disc-saw head (

Figure 2). They represented the shear and the disc treatment, respectively. The shear head was connected to boom tip through an active joint, while the saw-head was a dangle type. Both machines were operated by professional operators, who had the necessary specific qualification and experience.

Before starting the trial, all trees were attributed ID numbers, which were written on their trunks using high-visibility permanent paint, for easy identification during cutting and afterwards. A caliper was used to determine the diameter at breast height (DBH) of all trees with the accuracy of 0.5 cm. The diameter at 5 m was estimated by assuming a taper of 0.6% (-0.6 cm in diameter for each meter upwards the trunk [

19]) , given the difficulty of taking a reliable direct measure of diameter at that height.

During the trial, a researcher recorded the time taken to cut the top off each tree, and to lay it down on the ground [

20]. The treating of one tree, was the observation unit and the time required to do that (i.e. work cycle time) was divided into the following tasks (i.e. work time elements): moving the machine from one work station to the next; extending the boom and grabbing the top to be cut with the grapple arms; cutting the top with the shears or the disc; laying the cut top on the ground. The short descriptors for those tasks were, respectively: “move”, “grab”, “cut” and “dump”. Delay time was kept separate and excluded from the analysis, given that the short observation time could not offer a fair representation for its actual impact. A 25% delay factor was used, instead [

21]. Work time was logged using an iPad equipped with the dedicated software Laubrass UMT Plus (

https://laubrass.com/solutions/umt-plus/). All time records were associated with the respective tree IDs.

Machine costs were calculated with the method developed within the scope of COST Action FP0902 [

22]. Costing assumptions (investment cost, service life, fuel use etc.) were obtained directly from each individual machine owner, or from the manufacturers. Labor cost was assumed to be 20 € per scheduled machine hour (SMH), according to the approved regional price lists (

Table 1).

Work quality was estimated based on the conditions of the cut surface and the vigor of resprouting. For that purpose, all trees were inspected one year later, when one researcher on a lifting platform visually inspected the surface of all cuts to determine the presence of splits and whether the cut end was live or dry. In the latter case, the length of the dried stem portion was also measured. Furthermore, the researcher counted the number of live shoots on the cut and the diameter of three largest shoots taken at 30 cm from their insertion, with the accuracy of 1 mm [

23].

Data analysis consisted in the extraction of simple descriptive statistics, aimed at providing solid indicators for centrality and variability. Then, the statistical significance of the differences between the two treatments was checked using non-parametric statistics, which are robust against any eventual violations of the statistical assumptions. The statistical significance of any differences in the distribution of different cutting quality classes between the two treatment was assessed using the χ2 test. Finally, regression analysis was used to check the statistical significance of any trends. The chosen significance level was α<0.05.

3. Results

The DBH of pollarded trees varied from 9 cm to 33 cm, with its mean value at 19.6 cm (median = 19 cm). However, the largest number of trees had a DBH between 17 and 22 cm (interquartile range). Despite our effort to achieve an even distribution of tree size between treatments, the trees negotiated by the disc saw were significantly larger than those handled by the shears (

Table 2). Of course, the cut was performed almost 4 m above DBH, and therefore the diameter actually cut was much smaller: the mean diameter was 15.6 cm and 17.0 cm, for the shears and the disc saw, respectively.

The entire topping cycle took less than one minute per tree, including delays, regardless of machine type: that corresponded to a productivity slightly below 100 trees per scheduled machine hour (SMH). Compared with the shears, the disc-saw machine was significantly faster when cutting and when laying down the cut top, but not when moving along the row, reaching out and grabbing the treetop (

Table 3). Fast cutting is a well-known quality of disc-saws and therefore this finding is not surprising: it rather confirms the good quality and the general reliability of the stop watching sessions. In contrast, it is a bit harder to explain why the disc saw was also faster than the shears when laying down the cut tops. A most likely explanation is the smaller size of the excavator carrying the disc-saw. While both excavators were the same power and cost, the unit carrying the disc saw was a compact zero-tail swing model. It stands to reason that a compact machine may enjoy some advantage over a standard one, when working within a 6 m interrow, where it is constrained on both sides by standing trees. The alternative explanation is that of different operator skill and work technique, which is also likely; yet, both operators had similar age, service experience and apparent competence, which may suggest they would perform quite similarly under the same operational conditions.

However, the variability introduced by the other work tasks was large and it offset any advantage gained by the disc-saw when cutting and laying down the tops. Therefore, productivity was not significantly different between the two treatments, and neither was cost. In fact, the disc-saw was more expensive to operate, but the cost increase was not too large (15%) and was largely absorbed by the higher productivity (11%, although not significant). As a result, topping cost was just few cents higher than 1 € tree-1, regardless of the treatment.

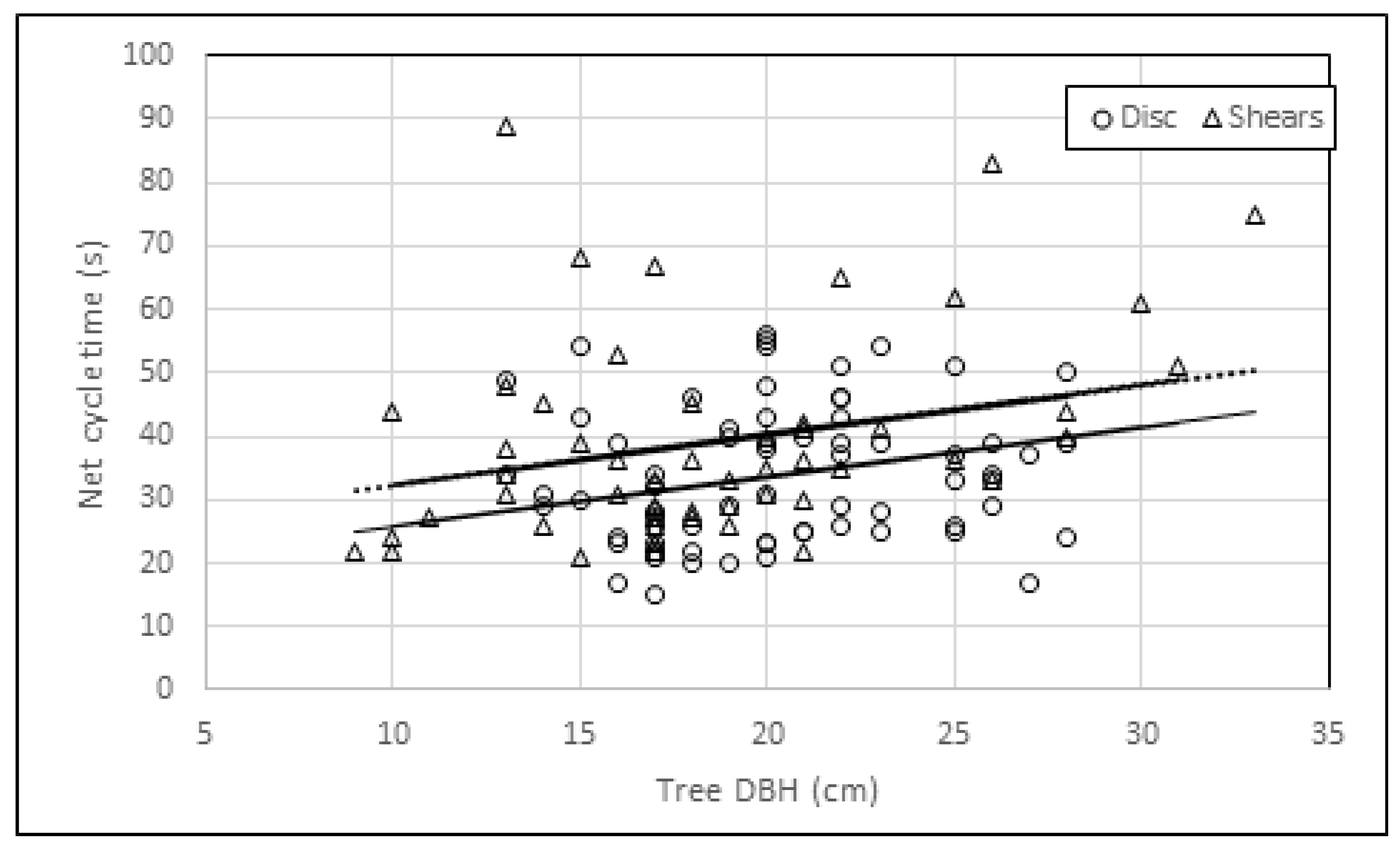

Tree size had a very small effect on time consumption: regression analysis showed that the time to top a tree increased with tree DBH and was shorter when the disc saw was used, but this relationship was very weak (r

2 <0.1), at least within the range of explored tree sizes. Both coefficients were highly significant (p = 0.0025 for DBH, p = 0.0069 for treatment), but the overall effect was modest: it took between 25 s and 35 s to top a tree with a DBH of 10 cm, and between 30 s and 40 s for a tree with DBH of 30 cm (

Figure 3).

Cut quality was much lower for the shears, compared with the disc saw (

Table 3). Over 40% of the cuts performed with the shears presented visible splitting, while no splitting was found on any of the cuts performed with the saw.

4. Discussion

Pollarding can contribute to alley-cropping through sheltering and product integration, and therefore it has a definite role within agroforestry. Modern technology can restore financial and social sustainability to this ancient and valuable practice. The introduction of simple felling machines makes the operation fast and safe. Once mechanized, tree topping incurs a cost that can be estimated at approximately 1 € tree-1, or 250-350 € ha-1. In return, the farmer will obtain a certain amount of biomass and an increase in the yields of the alley crop, extended over several years. Mechanization also allows cutting the treetops several meters above ground level, so that the trunks of the pollarded trees may yield valuable timber once they are renewed.

The occurrence of splitting did not seem to be associated with tree size, since the diameter of trees with splits on their cut surfaces did not differ significantly from the diameter of those without any splits (p = 0.51). Obviously, DBH is not the same as the diameter where the topping cut is performed – 3.7 m higher – but the two are closely related. The absence of any relationship between splitting and diameter suggests that the cause of splitting may not be the compression exerted by the shear mechanism, which is proportional to cut diameter and should result in an increase of splitting events with tree diameter – which was not the case here [

24]. Therefore, a more likely cause of splitting might be the tension applied to the cut stem by the shear head. This machine is designed to perform the cut only after the top has been grabbed by the grapple arms, and therefore some pressure is applied to the stem before cutting – the more so for the model used in this trial, which was connected to the excavator boom through a stiff active joint that left no margins for automatic adjustment. In contrast, disc-saw heads are designed in a way that the grapple arms firmly seize the cut stems only when the cut is completed, for the very purpose of avoiding that tension is applied to the stem during cutting and prevent splitting.

What are the consequences of splitting, then? One may imagine two main effects: weaker resprouting and wood decay [

25]. In fact, the measurements taken one year after cutting did not bring any evidence of the former, and could not shed any light on the latter, which would take some time to show, if it will. After one year of vegetation, pollards with a split top did not seem to have lost any resprouting vigor: there was no significant difference between sound and split pollards regarding the number of shoots and the size of the three dominant shoots (

Table 3). A possible indicator of wood decay could be the drying of the stem below the cut surface. Such phenomenon was observed on 40% of the stems, under both treatments and for both cut qualities - that is: sound or split. Drying was more frequent for split cuts than for sound ones (67% vs. 36%), although such difference did not check as significant for the χ2 test. Given that the frequency of drying is not significantly associated with split damage or treatment, it is logical to look somewhere else for its probable cause – maybe bud position relative to cut. Furthermore, until we cut the trunks and open them, we cannot know if trunks with dry ends are more likely to present wood stain or decay, compared with the other trunks that do not show any drying, but just live scar tissue. This is definitely one of the main subjects of the new research planned in Ceregnano.

Another question concerns the mass of treetops, which may be turned into a biomass product and sold to recoup part of the pollarding cost. However, that was not determined in this study and should be addressed in future research.

Clearly, the present study is far from perfect – yet, it offers viable reference figures and it is the only one available so far on the technical and operational aspects of pollarding – mechanized or otherwise. However preliminary and approximate, the knowledge obtained from this study represents the only solid foundation available to date for analyzing and hopefully improving the financial sustainability of a valuable tradition that can accrue strong environmental benefits through the multiple ecosystem services provided by pollarded trees [

26].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M., G.M. and R.S.; methodology, R.S.; resources, G.M.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, N.M., G.M., R.S.; supervision, R.S.; project administration, N.M.; funding acquisition, G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Acknowledgments

The Authors acknowledge the scientific, technical, administrative and organizational support of Dott. Loris Agostinetto – Veneto Agricoltura.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Burnett, C.; Gilluly, D. Pollarding for Multiple Benefits. Northern J Appl For 1988, 5, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, H.J.; Dagley, J.; Elosegui, J.M. Restoration of lapsed beech pollards: evaluation of techniques and guidance for future work. Arboric J 2013, 35, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, S.; Watkins, C. Pollarding trees: changing attitudes to a traditional land management practice in Britain 1600–1900. Rural Hist 2003, 14, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, H.J. (2008) Pollards and pollarding in Europe. Br Wildl 2008, 19, 250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Sjölund, M.J.; Jump, A.S. The benefits and hazards of exploiting vegetative regeneration for forest conservation management in a warming world. Forestry 2013, 86, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedri, L.; Ghahramany, L.; Ghazanfari, H.; Pulido, F. (2017) A quantitative study of pollarding process in silvopastoral systems of Northern Zagros, Iran. For Syst 2017, 26, e018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Pearce, B.; Wolfe, M. A European perspective for developing modern multifunctional agroforestry systems for sustainable intensification. Renew Agric Food Syst 2012, 27, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. Looking Back to the Future: Ancient, Working Pollards and Europe’s Silvo-Pastoral Systems. 10.1007/978-94-007-6159-9_25. P. 371-376. In: Rotherham, I. Cultural Severance and the Environment: The Ending of Traditional and Customary Practice on Commons and Landscapes Managed in Common. 2013, 10.1007/978-94-007-6159-9. Springer, Dordrecht. 447 p.

- Read, H. A study of practical pollarding techniques in northern Europe. Report of a three month study tour August to November 2003. 234 p. https://www.ancienttreeforum.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/A-study-of-practical-pollarding-techniques-in-northern.pdf. Accessed on February 2nd, 2024.

- Eichhorn, M.P.; Paris, P.; Herzog, F. Silvoarable systems in Europe - Past, present and future prospects. Agrofor Syst 2006, 67, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollen-Norrlin, M.; Ghaley, B.; Rintoul, N. Agroforestry Benefits and Challenges for Adoption in Europe and Beyond. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciotto, G.; Minotta, G.; Paris, P.; Pelleri, F. Tree farming, agroforestry and the new green revolution. A necessary alliance. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Congress of Silviculture“Designing the future of the forestry sector”. Florence (Italy) 26-29 Nov 2014. Accademia Italiana di Scienze Forestali, Firenze, Italy, vol. 2, pp. 658-669.

- Dufour, L.; Gosme, M.; Le Bec, J.; Dupraz, C. Does pollarding trees improve the crop yield in a mature alley-cropping agroforestry system? J Agron Crop Sc 2020, 206, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhech, A.; Genin, D.; Ait-El-Mokhtar, M.; Outamamat, M.; M’Sou, S.; Alifriqui, M.; Meddich, A.; Hafid, M. Traditional Pollarding Practices for Dimorphic Ash Tree (Fraxinus dimorpha) Support Soil Fertility in the Moroccan High Atlas. Land 2020, 9, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero, A.; Passola, G.; Aragón, A.; de Francisco, M.; Mugarza, V.; Riaño, P. Notes on pollards – best practice guide for pollarding. Gipuzkoako Foru Aldundia-Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa. 2017. 92 p. https://symposiumleitza2017.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/notes-on-pollards-best-practice-guide.pdf.

- Báder, M.; Németh, R.; Vörös, Á.; Toth, Z.; Novotni, A. The effect of agroforestry farming on wood quality and timber industry and its supportation by Horizon 2020. Agroforest Syst 2023, 97, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, L.; Cantamessa, S.; Chiarabaglio, P.M.; Coaloa, D. Competition effects and economic scenarios in an agroforestry system with cereal crops and wood plantations: a case study in the Po Valley (Italy). iForest 2021, 14, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, P.; Leonardi, L.; Cherubini, M.; Chiocchini, F.; Lauteri, M.; Pisanelli, A.; Dalla Valle, C.; Mezzalira, G.; Sangiovanni, M.; Facciotto, G.; Nervo, G.; Coaloa, D. Hybrid poplars for timber with arable crops in Italy: innovating the tradition facing Global Changes. In: Proceedings of the “4th World Congress on Agroforestry”. Montpellier (France) 20-22 May 2019. CIRAD, Paris, France, pp. 314.

- Spinelli, R.; Hartsough, B.; Pottle, S. On-site veneer production in short-rotation hybrid poplar plantations. For Prod J 2008, 58, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Magagnotti, N.; Kanzian, C.; Schulmeyer, F.; Spinelli, R. A new guide for work studies in forestry. Int J For Eng 2013, 24, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, R.; Visser, R. Analyzing and estimating delays in harvester operations. Int J For Eng 2008, 19, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, P.; Belbo, H.; Eliasson, L.; de Jong, A.; Lazdins, A.; Lyons, J. The COST model for calculation of forest operations costs. Int J For Eng 2014, 25, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, B.; Magagnotti, N.; Picchio, R.; Spinelli, R. Assessing the resprouting vigour of an Italian coppice stand after alternative felling methods. For Ecol Manag 2023, 545, 121250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeel, J.; Czerepinski, F. Effect of felling head design on shear-related damage on Southern yellow pine. South J Appl For 1987, 11, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.; Jeschke, M.; Wommelsdorf, T.; Backes, T.; Lv, C.; Zhang, X.; Thomas, F. Wood harvest by pollarding exerts long-term effects on Populus euphratica stands in riparian forests at the Tarim River, NW China. For Ecol Manag 2015, 353, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel-Pérez, D.; Hernández-Alonso, H.; Castro, F.; Sangüesa-Barreda, G.; Mutke, S.; García-Hidalgo, M.; Rozas, V.; Olano, J. 250-Year reconstruction of pollarding events reveals sharp management changes in Iberian ash woodlands. Trees 2022, 36, 1909–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).