Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Methodological Considerations

2.1. Processing Types and Allocation of Cognitive Resources in Translators

2.2. Unit to Describe Cognitive Processing During Translation

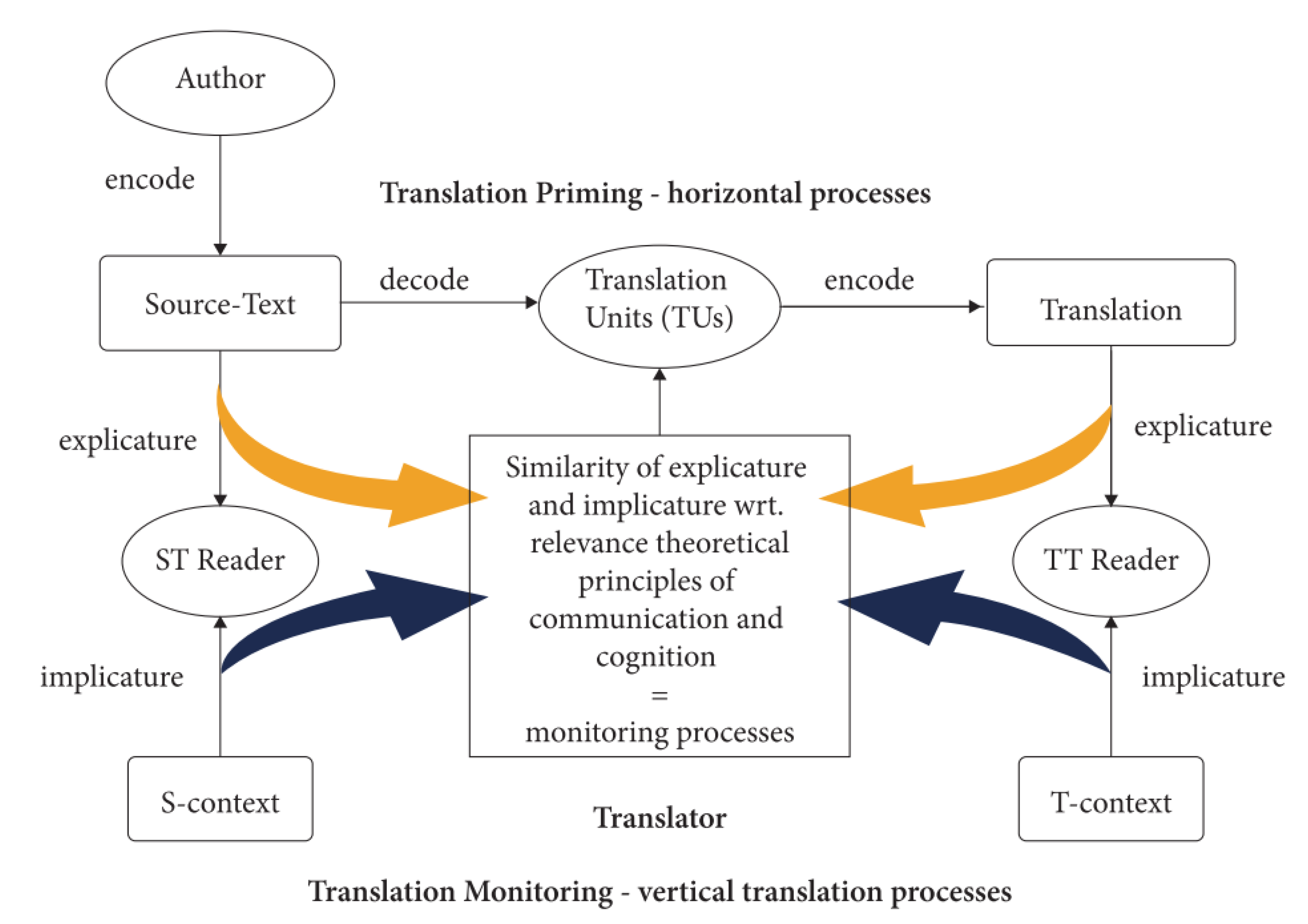

2.3. Models of Translation Processes

2.4. Translation Directionality and Allocation of Cognitive Resources

- 1)

- In both translation directions, parallel coordination of Source Text (ST) processing and Target Text (TT) processing exist.

- 2)

- In both translation directions, the amount of cognitive resources allocated on different attention types differs. Translators allocate more cognitive resources on TT processing than ST processing and parallel processing.

- 3)

- There are differences between descriptive data and participants’ self-reflection. For instance, participants may have a tendency of being unaware of the cognitive resources invested in first language production during L2-L1 translation.

3. Materials and Research Design

3.1. Subjects

3.2. Materials

3.3. Experimental Procedure

4. Results and Discussions

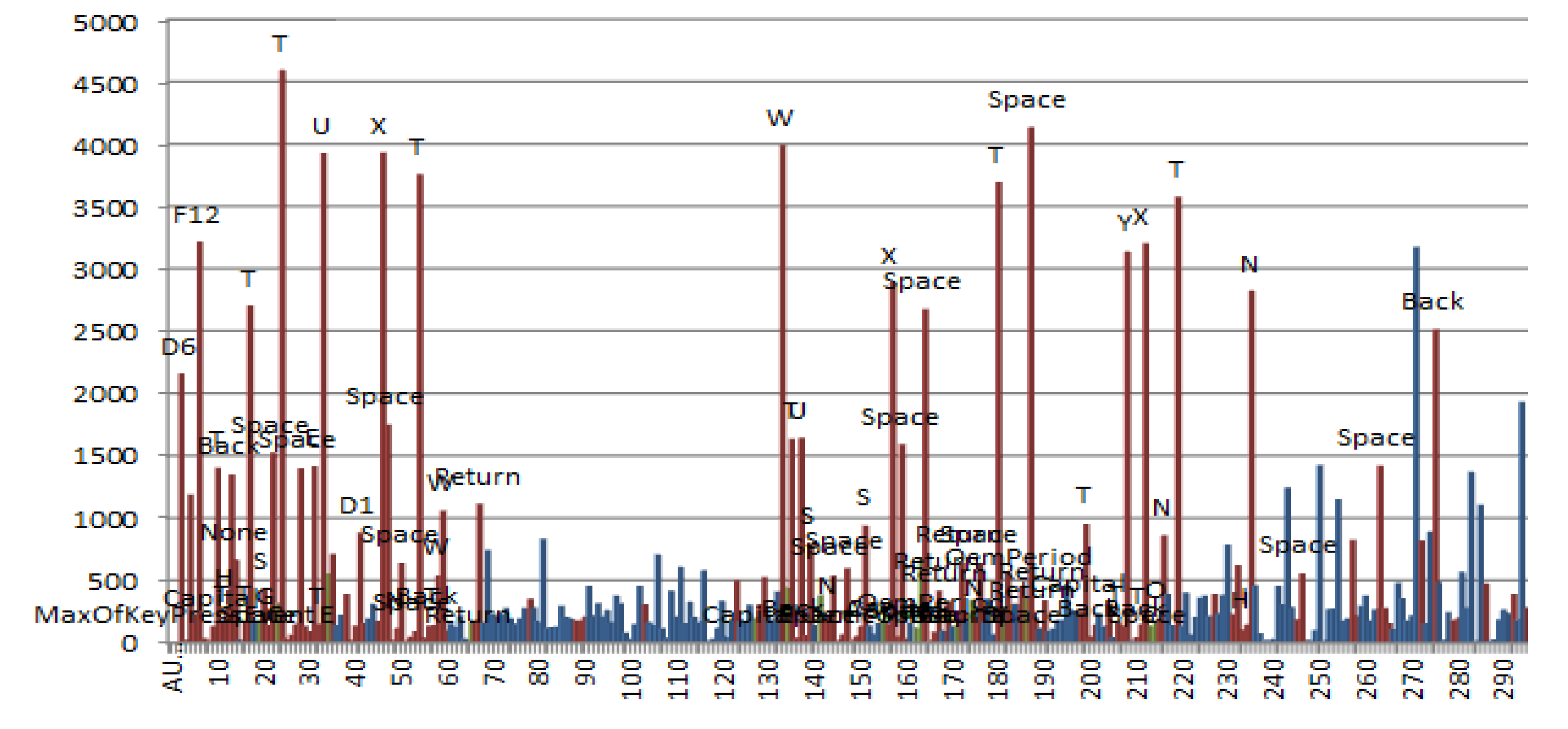

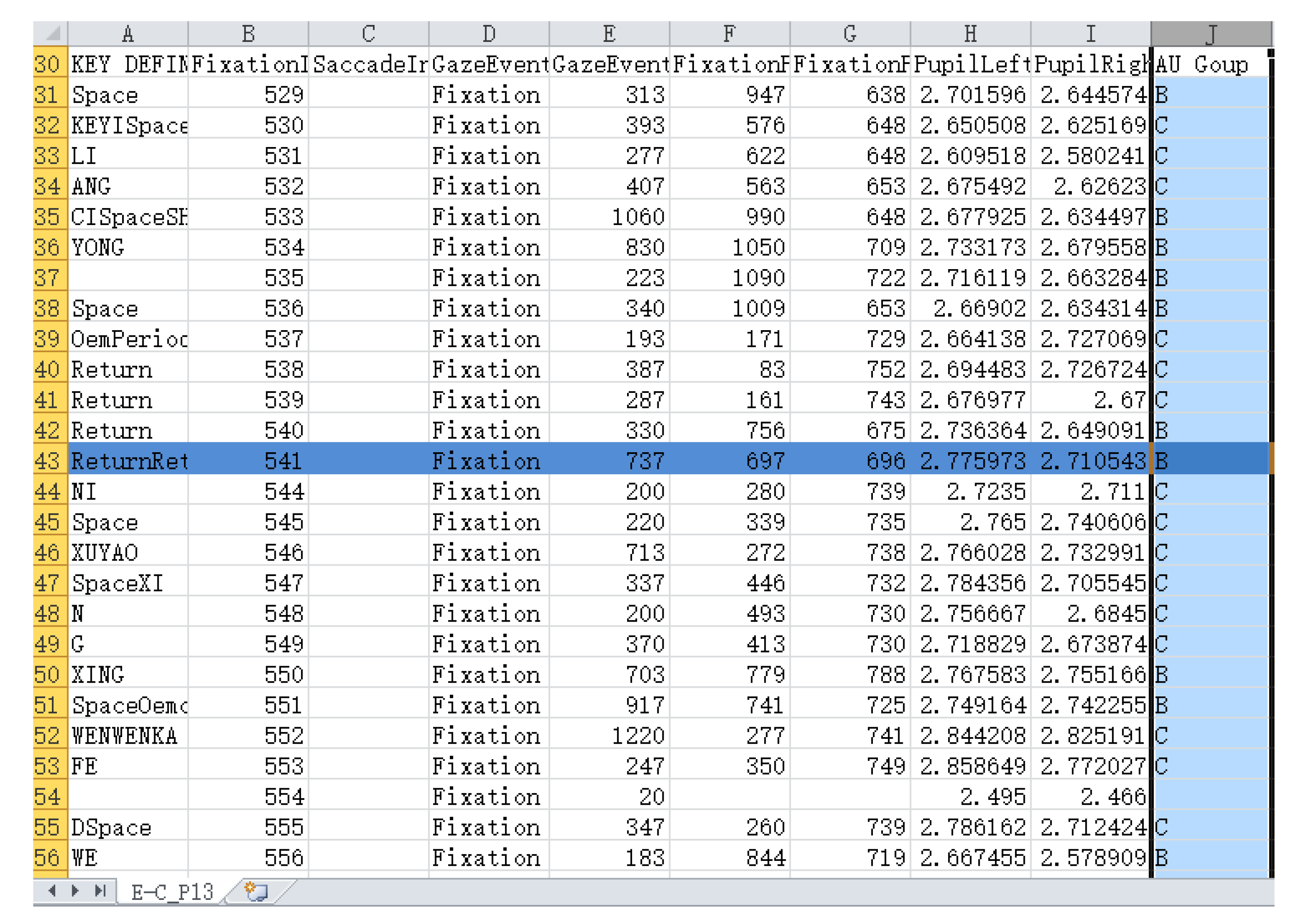

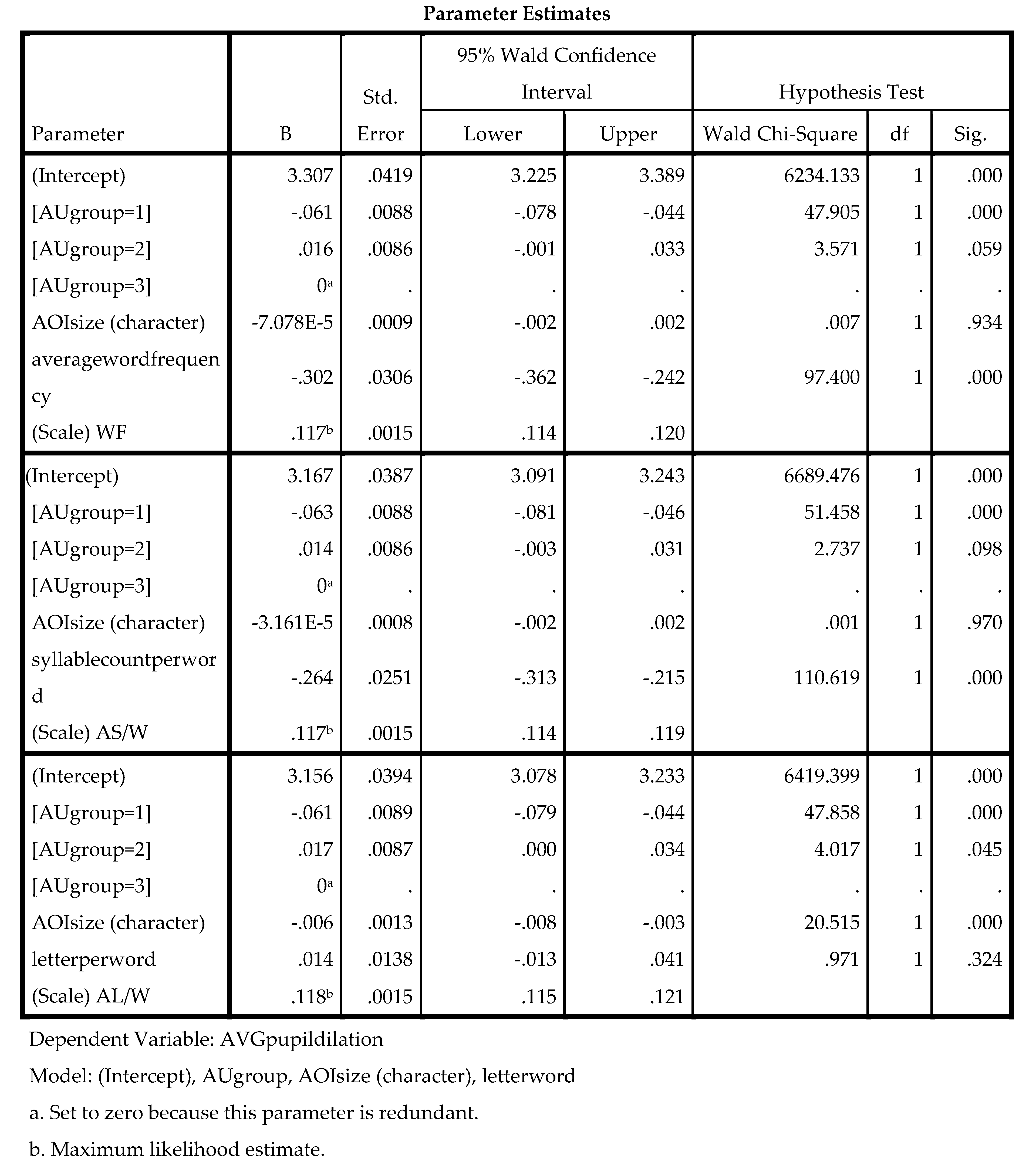

4.1. Eye Tracking and Key Logging Data Analysis

4.2. Retrospective Self-Reflections

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For this indicator, the number of parallel processing AU count is slightly higher than ST processing AU count, but the differences are not statistically significant. |

| 2 | In this model, the pupil dilation of parallel processing AU is bigger than ST processing AU, but the differences are not statistically significant. |

| 3 | The pupil dilation of C-E AU ranks as TT>ST>parallel, but only the difference between TT processing and parallel processing is statistically significant. |

References

- Beeby, A. Direction of translation: Directionality. In: Baker M. (Ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. London and New York: Routledge, 1998; 63-67.

- Gile, D. Directionality in Conference Interpreting: A Cognitive View. Monographies 38(1-2), 2005; 9-26.

- Wang, Y. The Impact of Directionality on Cognitive Patterns in the Translation of Metaphors. In: Muñoz Martín, R., Sun, S., Li, D. (eds) Advances in Cognitive Translation Studies. New Frontiers in Translation Studies. Springer, Singapore, 2021; 201-228.

- Chang V. and Chen I. Translation directionality and the Inhibitory Control Model: a machine learning approach to an eye-tracking study. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Martín R. M., S. Sun, & D. Li Advances in Cognitive Translation Studies. 2021; Singapore: Springer.

- Jensen, K. , Sjørup, A., and Balling, L. Effects of L1 Syntax on L2 Translation. In: Mees, I., Alves, F. and Göpferich, S. (Eds.), Methodology, Technology and Innovation in Translation Process Research: A Tribute to Arnt Lykke Jakobsen. Copenhagen: Samfundslitteratur. 2009; 319-336.

- Balling, L. W., Hvelplund, K. T. & Sjørup, A. C. Evidence of Parallel Processing During Translation. Meta, 59(2), 2014; 234–259. [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, N. Directionality in Collaborative Translation Processes. A Study of Novice Translators. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. 2007. Tarragona: Universitat Rovirai Virgili.

- Pavlović, N. More Ways to Explore the Translating Mind: Collaborative Translation Protocols. Copenhagen Studies in Language (CSL) 37, 2009; 81-105.

- Chang, V. 2011. Translation Directionality and the Revised Hierarchical Model: An Eye-Tracking Study. In: O’Brien, S. (Ed.), Cognitive Explorations of Translation. London and New York: Continuum. 2011; 154-174.

- Jensen, K. and Pavlović, N. Eye tracking translation directionality. In: Pym, A. and Perekrestenko, A. (Eds.), Translation Research Projects 2. Tarragona: Universitate Rovirai Virgili. 2009; 101-119.

- Alves, F. and Gonçalves, J. Investigating the Conceptual-procedural Distinction in the Translation Process: A Relevance-theoretic Analysis of Micro and Macro translation units. Target. 25(1), 2013;.107-124.

- Godijns, R. and Hinderdael, M. (Eds.) Directionality in Interpreting.The ‘Retour’ or the Native? Ghent: Communication and Cognition. 2005.

- Bartlomiejczyk, M. Strategies of Simultaneous Interpreting and Directionality. Interpreting International Journal of Research and Practice in Interpreting. 06(8), 2006; 149-174.

- Gile, D. Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1995.

- Frenchk-Mestre, C. Eye-movement Recording as a Tool for Studying Syntactic Processing in a Second Language: A Review of Methodologies and Experimental Findings. Second Language Research 21 (2), 2005; 175-198.

- Monti, C., Bendazzoli, C., Sandrelli, A. and Russo, M. Studying Directionality in Simultaneous Interpreting through an Electronic Corpus: EPIC (European Parliament Interpreting Corpus). Meta: Translators’ Journal; 50(4), 2005; 2-16.

- Jia J, Wei Z, Cheng H and Wang X. Translation directionality and translator anxiety: Evidence from eye movements in L1-L2 translation. Front. Psychol. 14:1120140. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Carl, Michael. Empirical Translation Process Research: Past and Possible Future Perspectives. Translation, Cognition & Behavior, 6(2), 2023; 252-274.

- Jakobsen, A. L. Logging time delay in translation. LSP Texts and the Translation Process 1 (1). 1998; 73−101.

- Li S, Wang Y & Rasmussen YZ (2022) Studying Interpreters’ Stress in Crisis Communication Evidence from Multimodal Technology of Eye-tracking, Heart Rate and Galvanic Skin Response. The Translator. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, A. and Jensen, K. Eye Movement Behaviour across Four Different Types of Reading Task. In: Göpferich, S., Jakobsen, A. L. and Mees, I. (Ed.), Looking at Eyes: Eye-Tracking Studies of Reading and Translation Processing, Copenhagen Studies in Language 36, Copenhagen: Samfundslitteratur. 2008; 103-124.

- Dragsted, B. Segmentation in translation: differences across level of expertise and difficulty. Target 2005; 17 (1): 49-70.

- Hvelplund, K. Allocation of Cognitive Resources in Translation: An Eye-tracking and Key-logging Study. Ph. D thesis. 2011. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School.

- Jääskeläinen, R. Think-Aloud Protocol Studies into Translation- an Annotated Bibliography. Target 14(1), 2002; 107-136.

- Seleskovitch, D. Interpretation: A Psychological Approach to Translating. In: Brislin, R. (Ed.), Translation: Applications and Research. New York: Gardner. 1976; 92–116.

- De Groot, A. The Cognitive Study of Translation and Interpretation: Three Approaches. In: Danks, H., Shreve, G., Fountain, S. and McBeath, M. (Ed.), Cognitive Processing in Translation and Interpreting. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 1997; 25-56.

- Ruiz, C., Paredes, N., Macizo, P. and Bajo, M. Activation of Lexical and Syntactic Target Language Properties in Translation. Acta Psychologica. 128 (3), 2008; 490-500.

- Kintsch, W. The Role of Knowledge in Discourse Comprehension: A Construction Integration Model. Psychological Review. 95, 1988; 163–182.

- Kintsch, W. Comprehension: A Paradigm for Cognition. 1998. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Danks, H. and Griffin, J. Reading and Translation: A Psycholinguistic Perspective. In: Danks, H., Shreve, G., Fountain, S. and McBeath, M. (Ed.), Cognitive Processing in Translation and Interpreting. CA: Sage, Thousand Oaks. 1997;161-175.

- Padilla, P., Bajo M. and Padila F. Proposal for a Cognitive Theory of Translation and Interpreting: A Methodology for Future Empirical Research. The Interpreter’s Newsletter; 9, 1999; 61–78.

- Kellogg, R. A Model of Working Memory in Writing. In: Levy, C. and Ransdell, S. (Ed.), The Science of Writing. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 1996; 57-71.

- Olive, T. Working Memory in Writing: Empirical Evidence from the Dual-task Technique. European Psychologist 9, 2004; 32-42.

- Anderson, J. Cognitive Psychology and its Implications (5th edn). 2000. New York: Worth.

- Pavlović, N. What Were They Thinking?! Students’ Decision Making in L1 and L2 Translation Processes. Hermes: Journal of Language and Communication Studies. 44, 2010; 63-87.

- Alves, F. , & Gonçalves, J. L. A Relevance Theory approach to the investigation of inferential processes. In F. Alves (Ed.), Triangulating translation: perspectives in process oriented research Vol. 45. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 2003; 3-24.

- Alves, F., J. L. Gonçalves, & K. Szpak. Identifying instances of processing effort in translation through heat maps: an eye-tracking study using multiple input sources. Paper presented at the 24th International Conference on Computational Linguistics. December 2012.

- Carl, M. and Dragsted, B. Inside the Monitor Model: Process of Default and Challenged Translation Production. Translation: Corpora, Computation, Cognition 2(1), 2012; 127-145.

- Balling, L., Hvelplund, K. & A. Sjørup. Evidence of parallel processing during translation. Meta, 2014( 2) : 234-259.

- Wang, X., Wang, L. and Zheng, B. The Influence of Translation Direction on the Process and Quality of Information Processing. Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 54(01): 2022, 128-139.

- Ferreira, Aline, Stefan Th. Gries & John W. Schwieter. Assessing indicators of cognitive effort in professional translators: A study on language dominance and directionality. In Tra&Co Group (ed.), Translation, Interpreting, Cognition: The Way Out of the Box, Berlin: Language. Science Press. 2021; 115–143. [CrossRef]

- Vinay, J.-P., & Darbelnet, J. Comparative stylistics of French and English: A methodology for translation (Vol. 11). 1995; Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Catford, J. C. A linguistic theory of translation: An essay in applied linguistics. 1965. London: Oxford University Press.

- Newmark, P. A textbook of translation (Vol. 66). 1988. London: Prentice Hall.

- Toury, G. Descriptive translation studies and beyond (Vol. 100). 1995; Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Gerver, D. Empirical Studies of Simultaneous Interpretation: A Review and a Model. In: Brislin, R. (Ed.), Translation: Applications and Research. New York: Gardner. 1976; 165-207.

- Dragsted, B. Segmentation in Translation and Translation Memory Systems. An Empirical Investigation of Cognitive Segmentation and Effects of Integrating a TM System into the Translation Process. Ph.D thesis, 2004. Amsterdam: Copenhagen Business School.

- Alves, F. and D. Vale. Probing the Unit of Translation in Time: Aspects of the Design and Development of a Web Application for Storing, Annotating, and Querying Translation Process Data. Across Languages and Cultures 10 (2). 2009; 251–273.

- Jääskeläinen, R. Features of Successful Translation Processes: A Think-Aloud Protocol Study. Ph. D thesis 1990. University of Joensuu.

- Carl, M. and Kay, M., Gazing and typing activities during translation: a comparative study of translation units of professional and student translators. Meta: Translators’ Journal 56 (4), 2011; 952–975.

- Baddeley, A. Working Memory. 1986. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Schaeffer, M., Dragsted, B., Hvelplund, K. T., Balling, L. W., & Carl, M. Word Translation Entropy: Evidence of Early Target Language Activation During Reading for Translation. In M. Carl, S. Bangalore, & M. Schaeffer (Eds.), New Directions in Empirical Translation Process Research: Exploring the CRITT TPR-DB Cham: Springer. 2016; 183-210.

- Tirkkonen-Condit, S., The monitor model revisited: evidence from process research. Meta: Translators’ Journal 50(2), 2005; 405–414.

- Gutt, Ernst. A. Translation and Relevance: Cognition and Context. 1989/1991/2000. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Gutt, Ernst. A. On the Significance of the Cognitive Core of Translation. The Translator, 11 (1). 2005; 25–49.

- Carl, Michael, and Moritz Schaeffer. Outline for a Relevance Theoretical Model of Machine Translation Post-editing. In Researching Cognitive Processes of Translation, edited by Defeng Li, Victoria Lai Cheng Lei, and Yuanjian He, Singapore: Springer. 2019; 49–67.

- Chang, V. C. Testing Applicability of Eye-tracking and fMRI to Translation and Interpreting Studies: An Investigation into Directionality. Ph.D thesis. 2009; London: Imperial College.

- Rayner, K. Eye movements in reading, and information processing. Psychological Bulletin. 124(3), 1998; 372-422.

- Schmaltz, M. An empirical-experimental study of problem solving in the translation of linguistic metaphors from Chinese into Portuguese. Ph.D thesis. 2015; Macau: University of Macau.

- Kroll, J. and Erika S. Category in translation and picture naming: Evidence for asymmetric connection between bilingual memory representations. Journal of Memory and Language. 33: 1994; 149–174.

| Categories of micro AUs | Categories of macro AUs |

|---|---|

| ST Gaze | STAU |

| No Gaze + Typing Gaze Off + Typing TT Gaze + Typing TT Gaze |

TTAU |

| ST Gaze + Typing | Parallel AU |

| No Data Gaze Off |

No Data |

| Task | AU group | Count | percentage | Average AU duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-E | ST processing | 2555 | 10.97% | 272.20 |

| TT processing | 4504 | 78.98% | 1147.65 | |

| Parallel processing | 892 | 10.05% | 286.74 | |

| E-C | ST processing | 4721 | 37.4% | 260.98 |

| TT processing | 5534 | 43.9% | 633.15 | |

| Parallel processing | 2360 | 18.7% | 295.85 |

| Indicator/ task |

Results of GLM models | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word Frequency | Syllable Count/ Word | Letter/ Word | ||

| TA duration | E-C | TT> ST> parallel | TT> ST> parallel | TT> ST> parallel |

| C-E | TT> ST> parallel | |||

| AU count | E-C | TT> ST> parallel | TT> ST> parallel | TT> ST> parallel |

| C-E | TT> ST> parallel | |||

| AU duration | E-C1 | TT> parallel TT> ST |

TT> parallel TT> ST |

TT> parallel TT> ST |

| C-E | TT> ST> parallel | |||

| Pupil dilation | E-C | TT> parallel TT> ST2 |

TT> parallel TT> ST |

TT> parallel> ST |

| C-E | TT>parallel3 | |||

| Allocation of cognitive resources on ST and TT | Allocation of cognitive resources on ST and TT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentence 1-3 | S4-6 | S7-9 | S1-3 | S4-6 | S7-9 | |||

| P01 | 60/40 | 50/50 | 50/50 | P12 | 60/40 | 70/30 | 80/20 | |

| P02 | 40/60 | 40/60 | 40/60 | P13 | 60/40 | 60/40 | 65/35 | |

| P03 | 50/50 | 60/40 | 60/40 | P14 | 50/50 | 60/40 | 60/40 | |

| P04 | 50/50 | 50/50 | 30/70 | P15 | 50/50 | 50/50 | 50/50 | |

| P05 | 30/70 | 40/60 | 50/50 | P16 | 50/50 | 50/50 | 50/50 | |

| P06 | 60/40 | 60/40 | 60/40 | P17 | 70/30 | 70/30 | 70/30 | |

| P07 | 50/50 | 60/40 | 60/40 | P18 | 40/60 | 40/60 | 50/50 | |

| P08 | 50/50 | 60/40 | 60/40 | P19 | 70/30 | 70/30 | 80/20 | |

| P09 | 50/50 | 60/40 | 60/40 | P20 | 50/50 | 40/60 | 50/50 | |

| P10 | 60/40 | 70/30 | 70/30 | P21 | 60/40 | 70/30 | 80/20 | |

| P11 | 50/50 | 50/50 | 50/50 | P22 | 50/50 | 50/50 | 50/50 | |

| Allocation of cognitive resources on ST and TT | Allocation of cognitive resources on ST and TT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1-3 | S4-6 | S7-9 | S1-3 | S4-6 | S7-9 | |||

| P01 | 40/60 | 30/70 | 30/70 | P12 | 30/70 | 30/70 | 30/70 | |

| P02 | 40/60 | 40/60 | 40/60 | P13 | 50/50 | 40/60 | 40/60 | |

| P03 | 40/60 | 30/70 | 30/70 | P14 | 30/70 | 30/70 | 30/70 | |

| P04 | 20/80 | 30/70 | 50/50 | P15 | 30/70 | 20/80 | 20/80 | |

| P05 | 20/80 | S | S | P16 | 40/60 | 40/60 | 35/65 | |

| P06 | 40/60 | 50/50 | 50/50 | P17 | 50/50 | 40/60 | 40/60 | |

| P07 | 40/60 | 50/50 | 50/50 | P18 | 30/70 | 30/70 | 20/80 | |

| P08 | 20/80 | 20/80 | 10/90 | P19 | 50/50 | 45/55 | 40/60 | |

| P09 | 40/60 | 30/70 | 20/80 | P20 | 50/50 | 50/50 | 40/60 | |

| P10 | 40/60 | 30/70 | 30/70 | P21 | 50/50 | 40/60 | 30/70 | |

| P11 | 20/80 | 20/80 | 20/80 | P22 | 50/50 | 45/55 | 30/70 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).