Highlights

What are the main findings?

There is a large gap between the ambitions of UDTs for urban planning and their realised contributions, mainly rooted in socio-technical complexities

There is a shift toward a socio-technical understanding of UDTs, in contrast to the previously predominant purely technical approaches

What is the implication of the main finding?

Adopting a socio-technical approach to UDTs is imperative; thus, we consolidate a socio-technical agenda for their research and development

We further extend this toward an outline of a methodological framework

1. Introduction

Context & Motivation

Since the first peer-reviewed mentions of Urban Digital Twins (UDTs) in 2018 [

1,

2], interest in this field has grown significantly. At the time of writing, a search query on Scopus for urban or city digital twins yields 994 peer-reviewed articles, with 356 of these focusing on urban planning and decision-making. This surge in publications indicates a strong interest within the scientific community. However, among these 356 articles, 48 are review articles, and none directly answer what the ambitions of UDTs have been regarding urban planning and decision-making, what the actual contributions are, why there is still a significant gap between ambitions and contributions eight years later, and how we can ensure UDTs deliver on their promises for urban planning. Here, we aim to answer these questions.

Digital twins were initially defined as digital replicas of physical products, processes, or entities [

3]. Extending this concept to built environment, UDTs have been defined as digital replicas of the urban environment [

4]. Early discussions primarily centered around UDTs as 3D models of urban environments [

5]. Over time, more technical ambitions were introduced, such as UDTs serving as exact replicas [

6], providing real-time representations [

7], and establishing live virtual-real connections [

8]. Recent reviews also show that the majority of UDT prototypes are developed within technical disciplines like urban water management, urban mobility planning, and urban energy planning [

9].

Problem Statement

Yet, the exact contribution of UDTs to urban planning and decision-making processes remains unclear [

10,

11]. There is a growing concern about the dangers of purely technical approaches that oversimplify social complexities or marginalize underrepresented groups through digital universalist methods [

12,

13,

14]. Very few UDT prototypes incorporate human-related dimensions of urban environments e.g. citizens’ perception of space or their preferences [

9]. Moreover, it seems there is minimal contribution to the active engagement of citizens in urban governance processes [

15]. Despite the prevailing lack of conceptual consistency in understanding UDTs—highlighted by varying definitions and categorizations in the literature [

9]—the outlined potentials and ambitions for UDTs seem to be ever expanding.

In the context of ongoing debates about the neglect of social dimensions in developing and using UDTs (UDTing), we try to answer these largely unanswered research questions: (1) what are the ambitions of UDTs for urban planning and decision-making; (2) what are the realized contributions of UDTs to urban planning and decision-making; and (3) how can we close the large gap between (1) and (2).

Methodology

In this study, we aimed to answer these questions by systematically reviewing peer-reviewed articles that either reflect on or demonstrate the implementation of UDTs to support urban planning and decision-making. We reviewed 84 articles—35 claiming a UDT implementation, 45 reflecting on UDTs, and 4 addressing both (

Section 2). Our review first mapped UDTs’ ambitions for urban planning to answer the first research question (

Section 3), and then mapped UDTs’ realized contributions to urban planning and decision-making to answer the second question (

Section 4).

UDT for Integration

The results of review indicates that, although the ambitions of UDTs constitute a diverse spectrum, the common sentiment is

integration. There is no consensus in interpreting what

integration means. It can be interpreted as system integration [

5], data integration [

16], model integration [

17], integration of multiple scales [

12], multi-disciplinary integration [

18], procedural integration [

19], or integration of stakeholders’ views [

11]. However, these different types of integration have not been equally explored in the research, leading to uneven attention across the various integration approaches.

Ambitions Versus Contributions

Comparing the detailed map of UDTs’ ambitions and contributions reveals that most UDT implementations have yet to deliver practical and societal value emphasized in UDTs’ ambitions for planning stakeholders. The reason is that UDT prototypes seldom address the socio-technical complexities of siloed urban disciplines, conflicting stakeholder dynamics, and opaque planning processes. As a result, UDTs fall short of being implemented in actual planning or decision-making processes.

The majority of contributions in UDT implementation articles are limited to demonstrating purely technical integration, with only a minority taking measures to bridge disciplinary silos. Nevertheless, they seldom provide realized digital representations contextualized through active engagement of stakeholders. There is also almost no contribution in operationalizing UDTs within urban planning and decision-making processes. Our findings substantiate these significant shortcomings in addressing socio-technical complexities [

9,

14].

Socio-Technical Agenda

Furthermore, there is no consistent research and development agenda addressing these socio-technical complexities [

20]. Moreover, the unhelpful assumption persists that technical development can proceed without deep consideration of the social, legal, and ethical dimensions of the urban environment [

9]. To address this, we cross-validated the identified gaps between ambitions and contributions with the challenges highlighted in the literature to consolidate a socio-technical agenda for closing these gaps.

AUP

The result is a cross-validated socio-technical agenda that defines UDTs as an integrated collection of urban data and models—integrated in the sense of being Interdisciplinarily Integrated (II), Consensually Contextualized (CC), and Procedurally Operationalized (PO). Such a socio-technically integrated digital representation would adequately augment the urban planning process without diminishing the complex dynamics of disciplines, stakeholders, and processes; hence, we propose Augmented Urban Planning (AUP).

2. Methodology

We use the systematic literature review method of PRISMA [

21] to ensure that we comprehensively cover the diverse literature on the relevance of UDTs for urban planning.

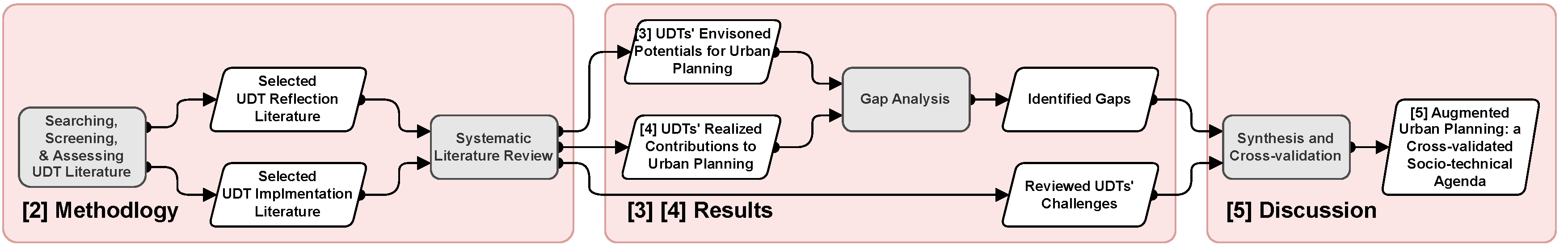

Figure 1, illustrates the methodological process of this article.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

We limit the articles to those directly discussing and contributing to the relation of UDTs with urban planning and decision-making. Therefore, we assessed the documents based on the following criteria:

Does the document pertain to urban planning or decision-making processes?

Does the document pertain to urban built environment?

Does the document pertain to UDTs?

We only included the papers that would satisfy all three criteria.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

We queried the Scopus database with the following query on November 29th 2024: TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( urban* OR city ) AND "digital twin” AND ( decision* OR plan* ) ) AND PUBYEAR > 2018 AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , "ar" ) OR LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , "re" )) AND ( EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "HEAL" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "NEUR" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "PHAR" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "PSYC" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "MEDI" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "ARTS" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "CHEM" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "BIOC" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "CENG" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "BUSI" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "MATE" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , "PHYS" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , "English" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SRCTYPE , "j" ) ).

2.3. Selection Process

We once screened the records and once assessed the documents before full-text review. These were conducted by one researcher. The screening round was based on the abstract of records. The assessment was based on the criteria (plan/decision, urban, and UDT), where we assessed the introduction and conclusion. In the assessment, we separated the articles into two categories of Reflection and Implementation based on whether the articles provided conceptual and theoretical reflections on the UDT discussion or contributed by demonstrating a UDT prototype. All documents were fully reviewed.

2.4. Study Selection

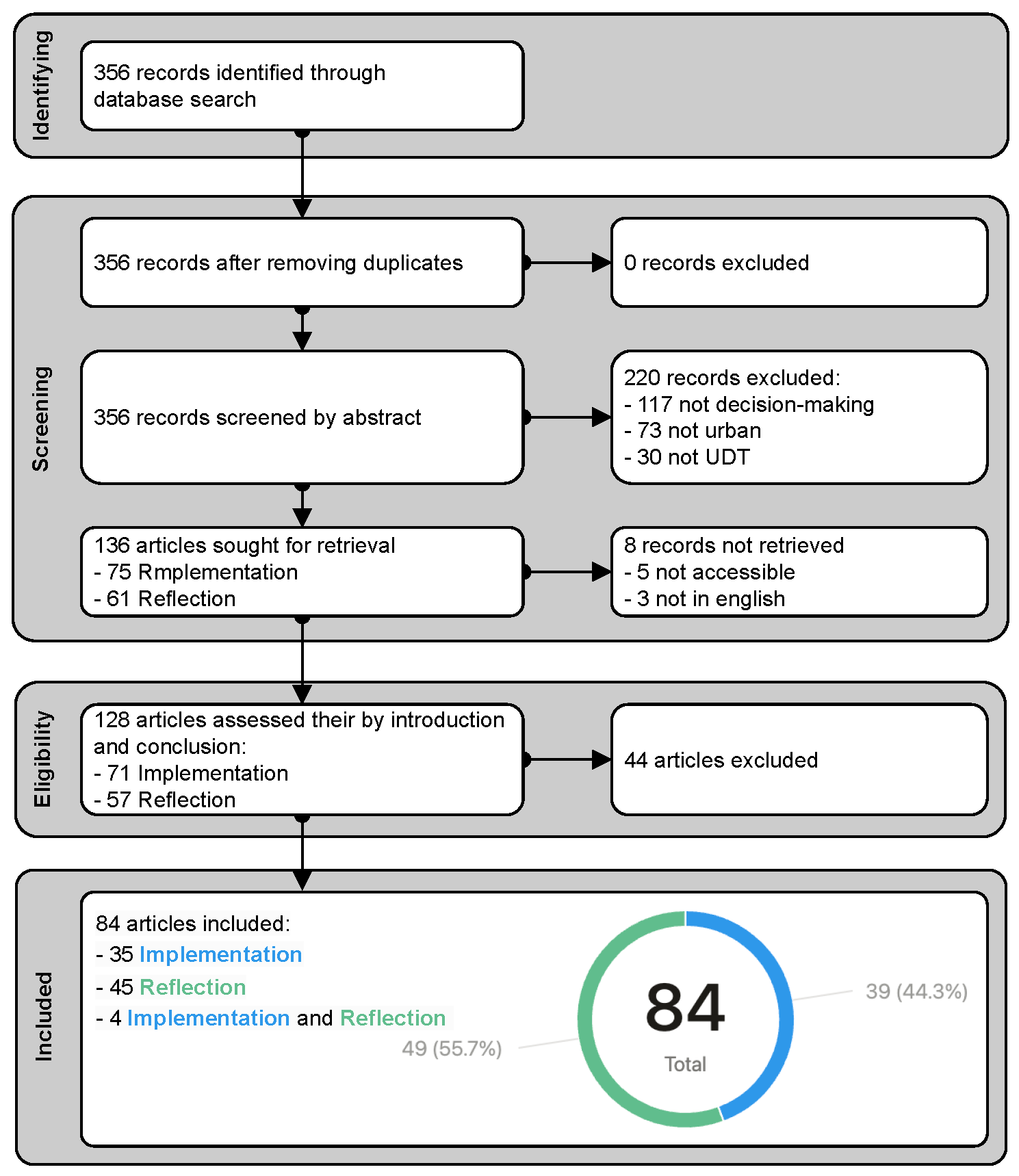

In the PRISMA diagram (

Figure 2) we outline how we selected the literature. In the end, 84 articles were deemed as qualified and included.

2.5. Study Limitations

We only relied on articles that were registered in Scopus, were accessible, and were written in English.

Moreover, we strictly focused on articles that directly contribute to the UDT discussion. Although closely related discussions—such as smart city systems, planning support systems, spatial decision support systems, and others—might offer insightful contributions to the discourse on the socio-technical complexities of integrated information systems. Our main reasoning for this approach is to aid in the consistency of conceptualization of UDTs; therefore, we avoided reviewing articles that have technical similarities but are framed differently. Nevertheless, the necessity for longitudinal studies of the development of such related topics and their relationships with each other could be a potential future avenue of research.

3. UDTs’ Ambitions for Urban Planning

Our systematic review of UDTs’ ambitions reflect a blend of ambitions from previous digital technologies, unified by a core focus on integration [

20]. However, interpretations of `what, how, and why to integrate?’ differ widely, encompassing the interoperability of technical systems [

5], cross-disciplinary alignment [

22], engagement of diverse stakeholders [

23], incorporation of legal and ethical frameworks [

9], as well as the seamless infusion of digital representations throughout the planning process [

14].

Early works on UDTs set high ambitions for technical integration [

13], with initial efforts centered on 3D modeling [

5], virtual-real integration [

24], realistic and real-time representations [

4], and technical scalability [

25]. While legal and ethical concerns, such as transparency [

26], cybersecurity [

25], privacy protection [

27], and legal implications [

28], were briefly acknowledged, they were not a primary focus. However, our review indicates a shift in the reflection literature towards addressing broader social aspects (see

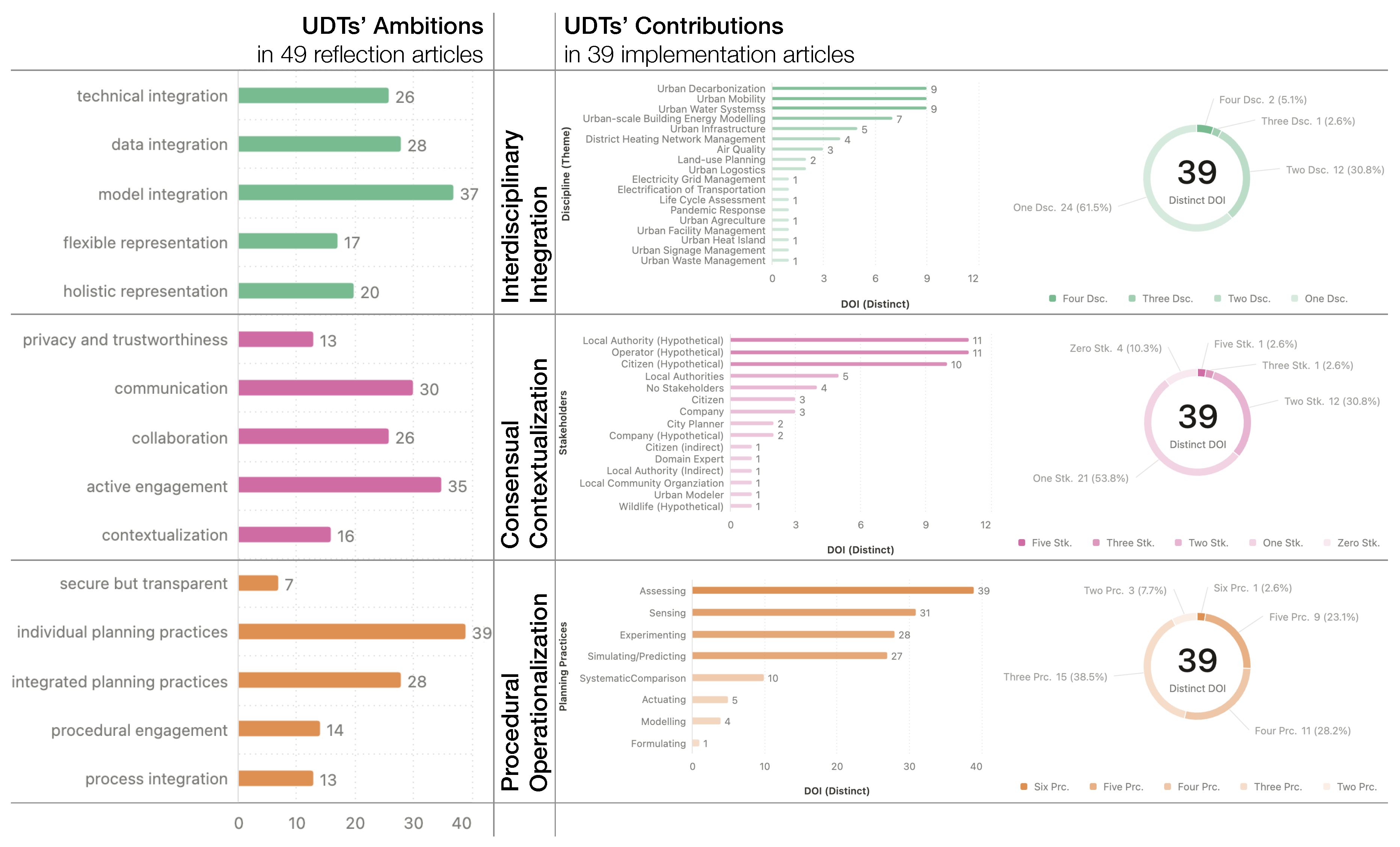

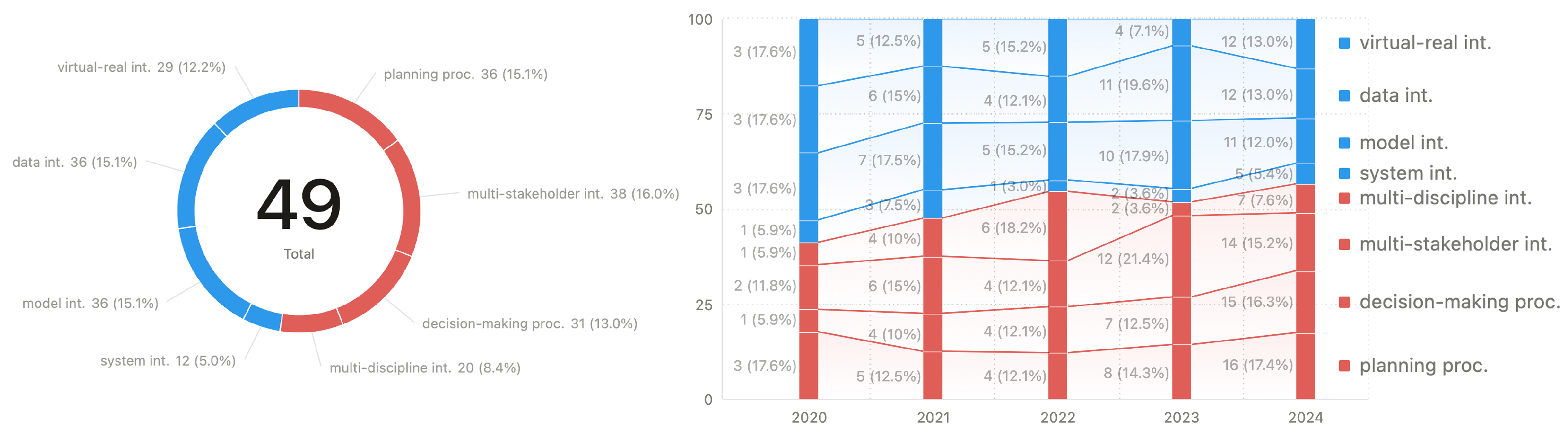

Figure 3).

Particularly, more and more authors reflect on the insufficiency of purely technical developments and set ambitions for UDTs that hinge on

socio-technical integration [

9,

23,

29,

30]. For instance they argue that UDTs should be informed by in-depth local knowledge [

23], consider citizens as humans with agency [

26], enable consensus among them [

31], and facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations [

17].

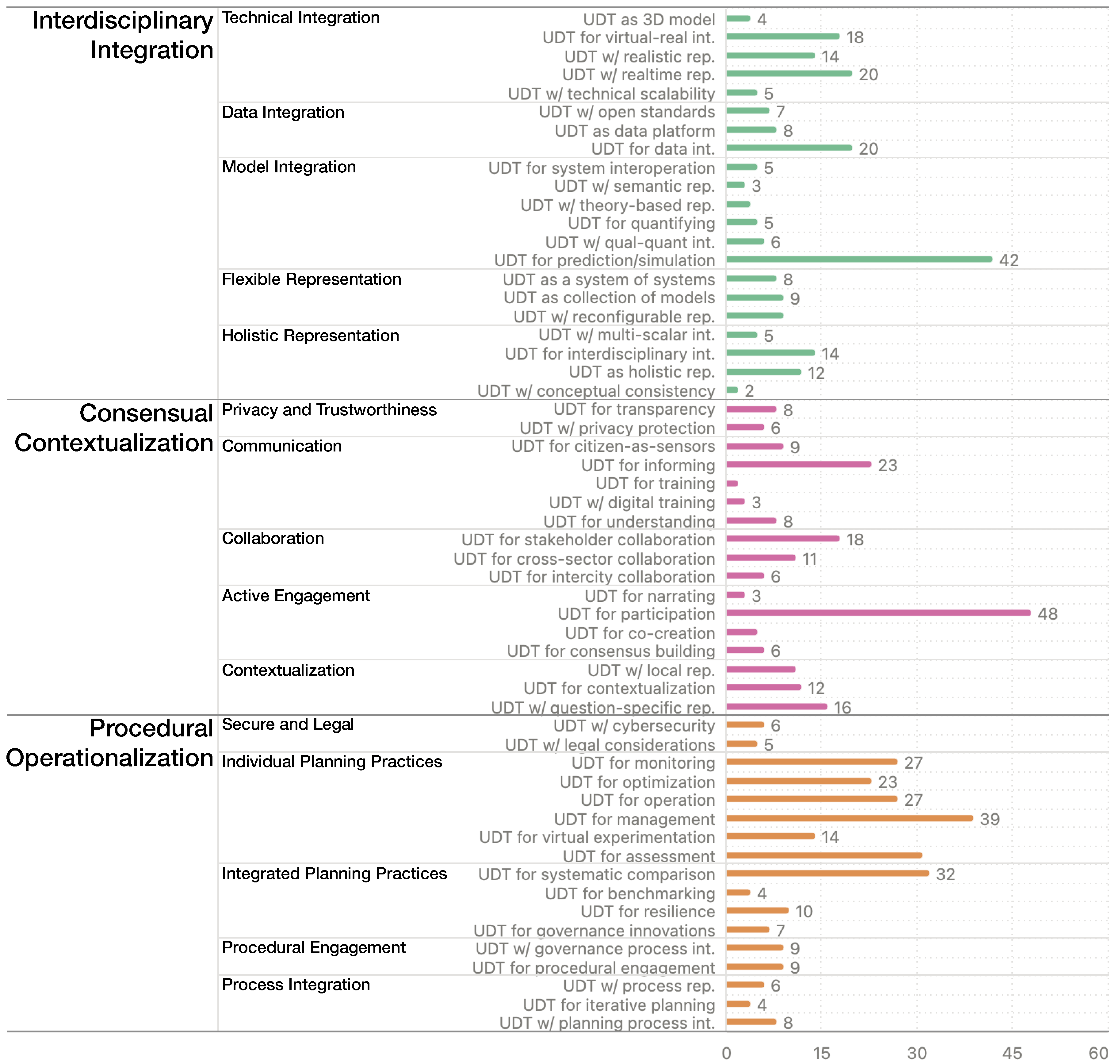

Accordingly, we categorize these different interpretations of integration in three socio-technical categories (see

Figure 4): integration in relation to different fields or Interdisciplinary Integration (II), integration in relation to stakeholders and citizens or Consensual Contextualization (CC), and integration in relation to processes or Procedural Operationalization (PO). The first category emphasizes the ambition for UDTs to be interdisciplinary integrated i.e. UDTs should bridge disciplinary silos and facilitate a holistic view of the urban environment by combining various urban models and data from different disciplines representing different urban functionalities [

20,

32]. The second category emphasizes the ambition for UDTs to be

consensually contextualized, i.e. UDTs should adequately represent the views of different stakeholders about the shared urban environment to facilitate better communication and participatory decision-making toward consensus [

14,

23,

29,

33]. The last category emphasizes the ambition for UDTs to be

procedurally operationalized, i.e. UDTs should be embedded within urban governance, decision-making, or planning processes and can provide insight for various questions that arise in different phases of these processes [

23,

34].

Unlike previous frameworks, we avoid distinguishing ambitions based on social, technical, legal and ethical categories. In our view, such categorizations would perpetuate the misguided notion that technical development can occur independent of its societal, ethical, or legal context [

13]. Instead, we categorize them based their integration complexity: in relation to disciplines (II), in relation to humans (CC), and lastly in relation to processes (PO).

Ambitions for Interdisciplinary Integration

UDTs’ ambitions for II encompass a range of objectives, each closely tied to the goal of bridging disciplinary gaps: technical integration, data integration, modelling consistency, flexible system architecture, and holistic representation. The more technical side of the spectrum focuses on providing an accurate 3D model [

5,

25], seamlessly bridging virtual and real twins [

24,

27], achieving realistic and real-time representations [

5,

6], and ultimately ensuring technical scalability [

5,

25] as a basis for diverse applications. Others highlight the importance of data integration through adopting open standards [

4,

35], establishing interoperable systems [

20,

36], and implementing UDTs as unified data platforms [

7,

37], facilitating seamless data sharing between disciplines. Some discussions revolves around the modeling approaches used in UDTing such as semantic representations [

20,

38,

39], and theory-based models [

23,

24], simulation models used for prediction [

40,

41], along with the integration of qualitative and quantitative methods [

20,

42], allowing for diverse disciplinary insights to be incorporated. Another set of ambitions revolve around UDT system architecture to ensure flexibility for the diverse needs of different disciplines, e.g. UDT as systems of systems [

28,

43], UDT as collection of models [

37,

44], and UDT with reconfigurable models. The last category focuses on holistic representation of urban environment [

12,

42] offering multi-scalar integration [

8,

45] across a diverse set of disciplines [

9,

18].

Ambitions for Consensual Contextualizatoin

UDTs’ ambitions for CC have a broad range of ambitions addressing complexities in human-technology and human-human relations: ethical considerations, communication, collaboration, localization, and participation. UDTs’ ambitions regarding ethical concerns mainly revolve around enhancing transparency [

7] and safeguarding privacy [

39] to ensure that UDTs are developed responsibly. The communication ambitions range from leveraging citizens as sensors [

18], informing citizens about policies [

8], offering digital and practical training [

46], and improving public understanding of urban complexity [

41]. In terms of collaboration, UDTs are envisioned to facilitate interactions among stakeholders [

33], support cross-sector partnerships [

47], and enable cooperation between different cities [

9]. Localization ambitions picture UDTs as contextualized representations [

29] incorporating local urban nuances [

23] and tailoring digital artifacts to specific questions and contexts [

37]. Finally, participation ambitions illustrate UDTs as vehicles for narrating cities by citizen [

29], fostering public participation [

26], enabling active co-creation [

42], and building consensus among diverse stakeholders [

31].

Ambitions for Procedural Operationalization

PO ambitions for UDTs revolve around legal integration, planning features, meta-planning capabilities, and procedural alignment. UDT’s ambitions regarding legal integration focuses on ensuring cybersecurity [

25] and incorporating legal frameworks [

29] to protect the integrity of UDT operations. A certain group of UDT’s ambitions focus on particular decision-making and planning features such as monitoring [

47], optimization [

25], operations [

45], management [

8], virtual experimentation [

48], and assessment [

49], providing practical tools for urban planners. Another set of ambitions address more complex planning activities e.g. systematic comparison of alternatives [

7], benchmarking [

9], ensuring resilience [

50], innovation in urban governance [

28], and representing processes [

49], offering strategic insights for long-term urban development. Lastly, ambitions with regard to procedural integration highlights the role of UDTs as operationalized digital systems that facilitate iterative planning [

17], enable engaging stakeholders in structured processes [

51], and align with governance and planning workflows [

20] to support continuous and adaptive decision-making.

4. UDTs’ Realized Contributions for Urban Planning

Despite the ambitious vision for UDTs, their realized contributions to urban planning and decision-making have been limited. More than half of all articles (53%) focus only on conceptual frameworks and reflective critique, while implemented prototypes are often confined to small-scale lab tests and rarely made publicly accessible. Even when accessible, these prototypes typically offer little more than an online data platform with basic 3D visualization, falling short of their broader potential.

Most claimed contributions of UDT implementations extend traditional urban modeling and analysis by integrating digital representations beyond conventional boundaries. For example Hofmeister et al. [

52] employ a knowledge graph-based approach for integrating dynamic control, emission dispersion, heat demand forecasting, cost optimization and air quality assessment to enable comprehensive urban energy scenario planning. Similarly Todorov et al. [

53] integrate virtual piloting of vehicle fleets, emissions assessment, total cost of ownership analysis, and practical considerations like depot locations, and vehicle technology to support comprehensive green planning of logistic vehicle fleet.

terms of the three socio-technical categories of integration: across disciplines (II), among stakeholders (CC), and throughout processes (PO). Appendix 6 describes in detail how we reviewed, categorized, and assessed contributions of UDTs to each of the socio-technical integration categories. While most integrative efforts have focused on advancing II, contributions to CC and PO remains limited. The major shortcoming in CC is that the dominant majority of articles only considered hypothetical stakehodlers. The foremost drawback in PO is that the vast majority of articles concentrated solely on isolated planning practices, neglecting an integrated approach to urban planning and decision-making processes. This starkly contrasts with UDTs’ ambitions that increasingly emphasize the importance of CC and PO.

Contributions to Interdisciplinary Integration

More than 80% of all contributions are in II, but they are not distributed evenly among subcategories. Our review indicates that the majority of focus has been on case-based technical integration, data integration and developing integrated models. While ensuring flexible system architecture and providing holistic representations have received less attention.

Examples of technical integration include automated information cascading [

52], continuous data acquisition [

54], and real-time situational awareness [

55]. Data integration received contributions from 80% of all implementation articles e.g. open data licensing [

56], deriving building-energy archetypes through data fusion [

35], and integrating IFC and COBie standards [

38]. The subcategory with most contributions by far is integrated model development that includes simulations e.g. agent based models for traffic [

57], assessments e.g. for GHG emissions [

58], and semantic models e.g. predicting demand in district heating networks [

52]. All 39 implementation articles claim at least one form of assessment module and the majority (70%) claim contributions based on simulation and predictive models. Despite strong emphasis on modularity in UDTs’ [

15] the majority of contributions here are limited to adopting or publishing open-source models [

51,

59]. The outstanding exception is the contribution of [

52] where they rely on a combination of knowledge graphs and modular computational agents based on the architecture of World Avatar project.

24 out of 39 implementation articles focus on only one discipline, with some involving two (12 articles), three (1 article [

60]), or four disciplines (2 articles [

52,

58]). Most interdisciplinary integrations occur within technical fields like urban water systems, urban decarbonization, urban mobility, urban-scale building energy modeling, and infrastructure, where cross-disciplinary links are conventionally established.

Contributions to Consensual Contextualization

Although all papers highlight the potential of UDTs to incorporate social aspects of urban built environment, very few implementation articles contribute explicitly. The majority of those contributing to CC are focused on digital interfaces (web-based, AR, VR, etc.) While some discuss crowd-sourcing and a few adopt a participatory approach, almost none advance co-creation, co-narration, co-visioning, or consensus-building potentials of UDTs.

The legal and ethical aspects of CC received little attention in implementation articles. The only contribution aimed at ensuring privacy protection and trustworthiness is the federated learning approach of Pang et al. [

27]. With regard to transparency efforts are limited to a few open-source models [

51,

59] and open-license data [

56]. The main bulk of contributions to CC are focused on digital interfaces used for communication with potential UDT users e.g. visual analytics [

54,

55,

61,

62] as well as crowd sourcing and gathering citizen sentiments [

51,

63]. In terms of collaboration, only 14 out of 39 articles considered more than one stakeholder type: 12 considered two; one considered three [

61], while only one considered five different stakeholder types [

23]. Moreover, one article contributed to inter-city UDTs [

27]. Participatory approaches were not common either. With 25 implementation articles focusing solely on technical or governmental stakeholders, 28 only considering hypothetical stakeholders, 10 with hypothetical citizens, and only 3 involving citizens in their studies [

23,

63,

64]. Some works involved local authorities [

10] and system operators [

65], while others presented preliminary work for citizen engagement [

51]. Contributions to contextualization were also minimal, with most studies merely incorporating demographic data. A notable exception is Nochta et al. [

23], which consulted a spectrum of participants about inclusion and importance of various urban dimensions to localize the UDT.

Contributions to Procedural Operationalization

The contributions to PO are even scarcer than CC. The majority of PO contributions are focused on isolated urban planning and decision-making practices such as assessing,monitoring, operating, or virtually experimenting with alternatives. while very few addressed more integrated urban planning practices such as systematic comparison of alternatives, modelling digital representations, long-term visioning and cultivating resilience. None of the implementation articles demonstrated the integration of UDTs in ubran planning, decision-making, or governance processes.

The only contribution to cyber security of UDTs was DUET’s proposed security architecture based on their T-Cell model [

28]. With respect to isolated planning activities, 39 out of 39 implementation articles highlight technical contributions to decision assessment, 31 to sensing and data acquisition, 28 to virtually experimenting with policy alternatives and 27 to simulation and prediction. Some argue that these technical developments contribute to monitoring [

62], operating [

6,

54], managing [

66], and optimizing [

57,

65]. Nevertheless, neither of these technical contrubtions have been implemented or tested in official planning and deicion-making processes. A few implementation articles address more integrated planning activites e.g. benchmarking [

67], cultivating resilience [

35], and systematic comparison of alternatives [

60,

62,

68]. In terms of iterative planning processes, procedural engagement of citizens, integration with governance processes, and procedural operationalization, there is no substatial contribution. The limited developments include the emphasis on iterative modelling to be able to adapt to local insights of citizens [

51], participatory development of UDT viewer [

61], and participatory workshops for co-drafting the required UDT features and potential alternatives [

23]. Lastly, there where only four implementation articles that addressed modelling and formulating activities in the planning process (e.g. [

37]), the rest were only focused on how UDTs can be used.

Figure 5.

Gap Analysis of the UDTs’ Contributions with respect to their Ambitions. The leftside illustrates the number of reflection articles outlining each of the high-level ambition categories. The rightside quantifies the contributions of implementation articles for each of the socio-technical types of integration. For II based on involved disciplines, for CC based on considered stakeholders, and for PO based on individual planning practices.

Figure 5.

Gap Analysis of the UDTs’ Contributions with respect to their Ambitions. The leftside illustrates the number of reflection articles outlining each of the high-level ambition categories. The rightside quantifies the contributions of implementation articles for each of the socio-technical types of integration. For II based on involved disciplines, for CC based on considered stakeholders, and for PO based on individual planning practices.

5. Augmented Urban Planning: A Cross-Validated Socio-Technical Agenda

5.1. UDT for Integration: A Comprehensive Definition

Integration

Our review reveals that despite the colorful pallet of ambitions set for UDTs, the common thread is

Integration. It can be system integration [

5], data integration [

16], model integration [

17], integration of multiple scales [

12], multi-disciplinary integration [

18], procedural integration [

19], or integration of stakeholders’ views [

11]. Nevertheless, these different interpretations of

Integration have not recieved equal attention (

Figure 3).

Purely Technical Perspective

Most UDT developments are concentrated in technically advanced fields. Our review indicates that implementation articles most frequently address urban water systems (9 articles), decarbonization (9 articles), urban mobility (9 articles), urban-scale building energy modeling (7 articles), and urban infrastructure (5 articles), with majority of other disciplines having only one article. Similarly, Wu and Guan [

9] also found in their literature review that the majority of developments occur in technically advanced urban fields such as mobility, energy, and water [

9]. Nevertheless, reflection articles depict a shift toward socio-technical perspectives.

In the recent years, there has been an increasing number of articles that emphasize the neglected social dimension in development of UDTs (see

Figure 3). Some scholars highlight the danger of technical optimisim [

13] and the UDT-specific branch of it dubbed digital universalism [

12]. They warn against the danger of overlooking social and ethical concerns [

13] that might be driven by `short-term economic-efficient fixies’ instead of societally informed investments and developments [

15]. Charitonidou [

12] calls for transcending purely technical aspects and emphasizes the socio-technical aspects.

Emerging Socio-Technical Perspective

While there is an emerging consensus on the need for a socio-technical approach, there is no concrete agenda or methodology. In their case review Quek et al. [

20] criticise fragmented technological development and argue for more `interoperability and compatibility’ in UDT developments. Wan et al. [

48] criticizes the neglect of theory-driven models in favour of data-driven approaches and calls for a combined theory-based and data-based approach. In their systematic review, Wu and Guan [

9] highlights the social and ethical chllanges in addition to technical challenges and proposes a hierarchy of UDTs: namely domain UDTs, intra-city UDTs, and inter-city UDTs. Lastly, Nochta et al. [

23] demonstrates a participatory workshoping approach for developing and using UDTs. Nonetheless, there is still a lack of clear agenda for ensuring that UDTs are socio-technically integrated. Here, we synthesize our findings to consolidate a socio-technical agenda for developing and using UDTs in urban planning and decision-making processes.

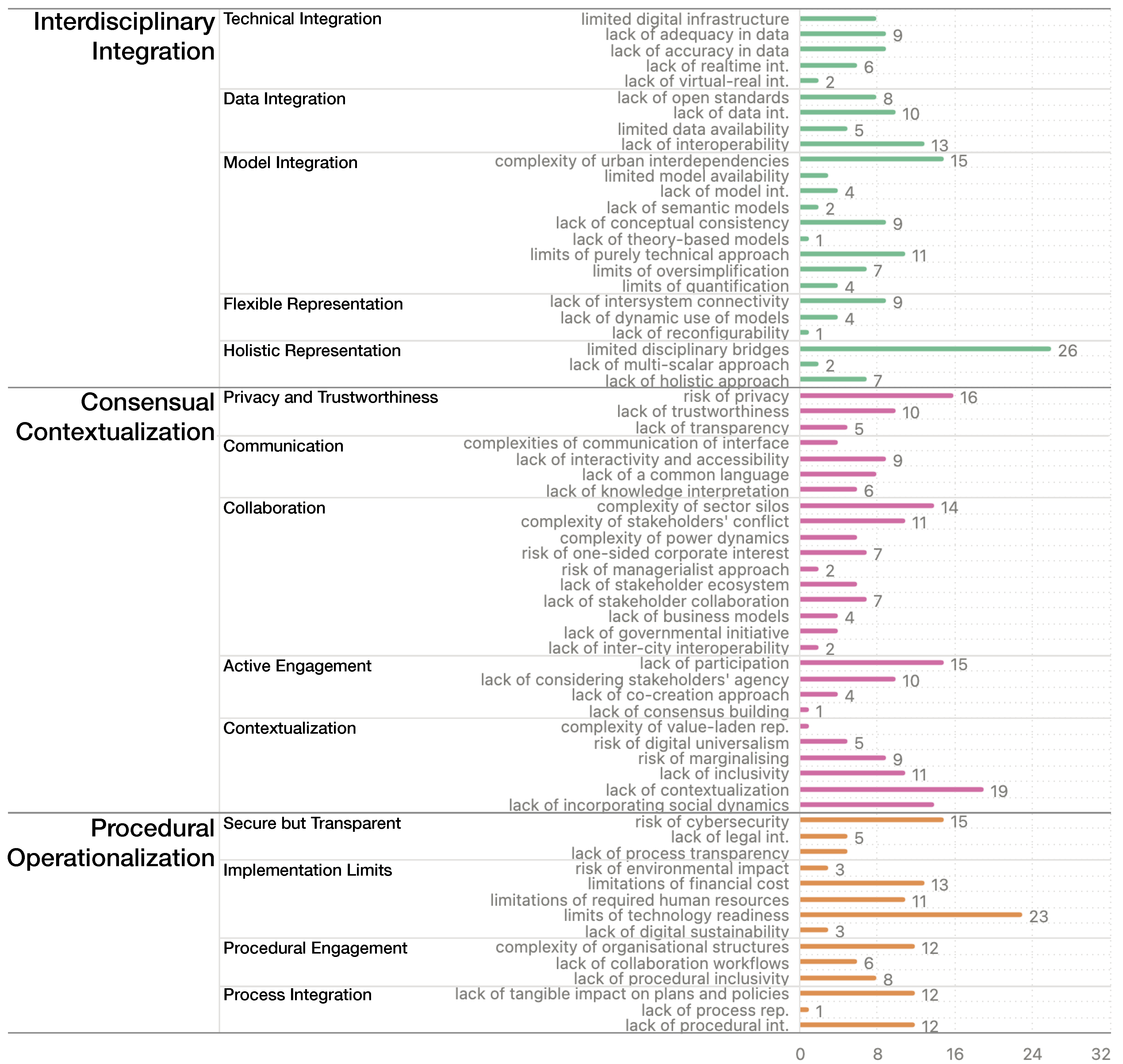

Figure 6.

Cross-validation of Augmented Urban Planning (AUP) Agenda: Number of Reflection articles contributing to each socio-technical limitations. II is green, CC is pink, and PO is orange. rep. stands for representation; int. stands for integration.

Figure 6.

Cross-validation of Augmented Urban Planning (AUP) Agenda: Number of Reflection articles contributing to each socio-technical limitations. II is green, CC is pink, and PO is orange. rep. stands for representation; int. stands for integration.

A Socio-Technical Definition of UDTs

To consolidate a research and development agenda for UDTs, we need to avoid isolating social and technical from each other. Thus, we define an ideal case where UDTs are socio-technically integrated; that is, UDTs are a consistent collection of urban data and models that are Interdisciplinarily Integrated (II), Consensually Contextualized (CC), and Procedurally Operationalized (PO) within urban planning processes. Such socio-technically integrated UDTs, as a collection of digital representations, are capable of augmenting the urban planning process to address (not resolve) its wicked complexity; thus, we call this ideal process an Augmented Urban Planning (AUP) process.

In the following, we present the socio-technical integration types as PO, CC, and II to ensure logical consistency of why such considerations are necessary in AUP. This order facilitates a natural flow of arguments and comprehensive coverage of concepts, while importantly demonstrating that technical development depends on and cannot be separated from procedural, contextual, and interdisciplinary considerations.

5.2. Procedural Operationalization

If UDTs are to achieve procedural operationalization (PO), it is crucial to integrate them into existing processes (

5.2.1). This integration depends on actively engaging relevant stakeholders in both the development and use of UDTs, ensuring that their needs and insights shape the technology (

5.2.2). Moreover, practical considerations like implementation budgets and limitations must be addressed to make UDTs feasible and sustainable (

5.2.3). Ultimately, UDTs should be developed to be secure yet transparent, balancing data protection with openness to foster trust and accountability (

5.2.4).

5.2.1. Process Integration

To effectively integrate UDTs into existing processes, it is essential to specify their relationship with current decision-making, planning, and governance frameworks [

69]. This involves identifying which questions within these processes require insights from UDTs and considering the complexities and dynamics inherent in planning to address ambiguity and support the entire planning process [

15,

20]. By doing so, we can specify, measure, and assess the tangible impact of UDTs on planning and policymaking outcomes [

20,

42]. However, achieving this integration is not an easy feat; it heavily depends on the depth and breadth of engagement from relevant stakeholders in the process (

5.2.2).

5.2.2. Procedural Engagement

For UDTs to facilitate active engagement of relevant stakeholders across the decision-making process, they need to address the complexity of organizational structures—such as isolated working methods [

69]—and ambiguities in regulatory frameworks and processes [

13]. Developing collaborative workflows is crucial, allowing stakeholders not only to inform or be informed but also to act as active agents in earlier decision-making stages like visioning and agenda-setting [

70]. Moreover, UDT developments must avoid reinforcing existing organizational barriers to citizen engagement and instead promote broader procedural inclusivity [

42,

47]. However, ensuring procedural engagement is impossible without UDTs enabling communication (

5.3.4), collaboration (

5.3.3), and active engagement (

5.3.2).

5.2.3. Implementation Limits

For UDTs to become a tangible information system, it is crucial to balance their cost and impact. Addressing the environmental footprint of the computationally intensive resources required for UDTs is essential [

18]. Developing standardized frameworks and infrastructures can lower the financial barriers to developing and using UDTs [

71]. Furthermore, implementing digital training programs that equip current practitioners with both technical and non-technical skill sets will enable them to use and contribute to these technologies critically [

23,

30,

46]. Given UDTs’ low technology readiness, they require further assessment and evaluation not only on technical criteria but also regarding their socio-technical contributions to demonstrate their usability [

72]. Lasltly, In an era of rapidly accelerating technologies, UDTs must be digitally sustainable to ensure future interoperability over a reasonable timeframe, considering the significant efforts and expenses involved [

20,

23]. Nonetheless, feasibility should not come at the cost of security and transparency (

5.2.4).

5.2.4. Secure but Transparent

If the procedural operationalization of UDTs strengthens opaque organizational processes or introduces cybersecurity risks, then despite technological progress, they could lead to social regress. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure that integrated platforms of data and models do not introduce cybersecurity vulnerabilities [

13,

73]. This should be achieved in accordance with existing legal frameworks like the GDPR [

28]. Equally important, UDTs should enhance procedural transparency in urban governance processes, facilitating public scrutiny and administrative accountability [

5,

13]. Nonetheless, this is deeply tied to how UDTs protect privacy and foster trust (

5.3.5).

5.3. Consensual Contextualization

To achieve consensual contextualization (CC) in UDTs, it is essential to provide local and context-specific representations of the urban environment (

5.3.1). This requires actively engaging relevant stakeholders, enabling them to interpret knowledge in their own context, co-create shared understanding, and reach consensus on immediate challenges and future decisions (

5.3.2). Such level of engagement depends on fostering collaboration among stakeholders (

5.3.3), which fundamentally relies on facilitating the emergence of a shared language for clear communication (

5.3.4). However, all these efforts are only possible if UDTs strive to protect citizens’ privacy and foster trust among the broader spectrum of stakeholders (

5.3.5).

5.3.1. Contextualization

If UDTs are to be local and contextual, we need to be wary of the danger of digital universalism, i.e., treating cities as if they are the same or one one single frame is enough to represent a city [

12,

23]. All models and data are value-laden; there are particular values embedded in their methods of measurement, assessment, aggregation, assumptions, etc. Therefore, we strongly argue that no representation (including the maximalist UDT) can be the single source of truth [

20,

48,

74]. If we treat any representation as such, we risk marginalizing those that are underrepresented in the frame of that representation and reinforcing age disparities, income disparities, race disparities, and more [

20,

47].

Thus, it is necessary to commit to the plurality of contextual representations, i.e., a plurality of specific UDTs: not only domain-specific and city-specific UDTs but also community-specific and stakeholder-specific UDTs; each curated with a set of data and models to serve the views and purposes of its particular stakeholder. With such a plurality, we would be able to get closer to ensuring inclusivity of diverse voices and views that co-live in cities [

46,

48]. This entails that in each of these stakeholder-specific UDTs, context information such as social and economic dimensions would be curated, incorporated, and interpreted through the lens of that particular stakeholder [

20,

41]. Nevertheless, we need to go beyond contextualizing in the isolated view of a single stakeholder and establish an interconnected system of stakeholder-specific UDTs that enables communication (

5.3.4), collaboration (

5.3.3), and ultimately consensus (

5.3.2).

5.3.2. Active Engagement

For UDTs to facilitate active engagement of stakeholders in urban governance processes, it’s necessary to ensure involvement of communities not just to be informed or as sources of information, but as active participants [

46,

50]. This entails that UDTs need to respect the agency of all stakeholders from experts and authorities to most importantly citizens. This can be done by providing stakeholder-specific representations allowing them to curate and interpret information [

15,

48]. This is crucial for enabling participants to co-create knowledge, vision, and policy alternatives through the interaction of their stakeholder-specific representations [

13,

70], which ultimately enables stakeholder-specific representations to converge toward at least a consensual policy, if not a consensual representation [

48]. However, the basic component of co-creation toward consensus is collaboration (

5.3.3).

5.3.3. Collaboration

For UDTs to enable collaboration, they need to address existing silos and unbalanced collaboration. Misalignment of terminology, views, and objectives strongly prevails not only between cities [

39], but also among sectors [

54], disciplines [

9], and even departments of a single organization [

69]. This entails that in any collaborative process, stakeholders’ conflicts are inevitable [

53]. Such conflicts can potentially lead to unbalanced power dynamics [

42], cessation of collaboration, or even further misalignments that foster predatory business models [

20] or managerialist approaches [

15].

Ultimately, developing and using UDTs need to rely on an existing ecosystem of stakeholders that allow experimenting with different structures of digital representations to support and strengthen their existing collaboration [

15,

71]. Governmental initiatives can be beneficial here as they are better positioned to host and stimulate collaboration [

15,

69]. And ideally, non-predatory business models can emerge in the social experiment of stakeholder-specific UDTs networks to provide practical values to all parties and sustain this step of digital transition [

13,

23]. Nonetheless, it is not possible to collaborate if there is no well-established communication network (

5.3.4).

5.3.4. Communication

For UDTs to facilitate communication with and among stakeholders, they need to provide customizable interfaces that can be adapted to stakeholders’ areas of expertise and skill levels [

10,

72]. In particular, visual interfaces should be interactive and accessible to ensure they are user-oriented [

8,

54] and practice-first [

15]. This is especially important with new technologies like AR and VR, which promise interactivity but are not accessible to all groups [

63]. Moreover, we need to avoid presenting data as if it is value-neutral; UDT interfaces should be transparent about the sources and assumptions behind each data and model, providing enough flexibility for stakeholders to interpret information [

20,

33,

48]. This approach would not only make UDTs more useful, but also enable stakeholders to access each other’s curation and interpretation of data, facilitate discussions, and ultimately allow peer learning and the co-creation of shared views and common language about the issues they are facing in their urban environment [

7,

13]. Yet, facilitating communication should occur in an environment where privacy is protected and trust is fostered (

5.3.5).

5.3.5. Privacy and Trustworthiness

Cultivating trust are essential prerequisites for effective communication, collaboration, consensus-building, and contextualization in UDTs. Trust is particularly hindered by growing anxiety about digital surveillance [

26] and wariness of large-scale digital solutions [

20]. Therefore, it is imperative that appropriate data privacy protections are implemented in UDT development [

17,

46]. These measures should range from obtaining informed consent during data gathering and conducting regular infrastructure audits to employing data anonymization and differential privacy techniques to reduce the risk of identification. Simultaneously, fostering trust requires transpaency regarding how data is managed [

42] and how models are prepared [

23].

5.4. Interdisciplinary Integration

Interdisciplinary integration (II) in UDTs involves creating a holistic representation—not as a universalist model but as a consistent collection of digital representations—that can provide insights for stakeholder-specific planning questions spanning across disciplines and scales of the urban environment (

5.4.1). Since all representations are inherently limited by their specific frames, the goal is to match these frames to the requirements of the planning questions. Naturally, iterative and dynamic planning processes mean that stakeholder-specific questions will inevitably evolve over time; therefore, UDTs must be flexible enough to continuously adapt to these changing frames and continue providing valid insights (

5.4.2). Achieving such flexibility necessitates a diverse spectrum of compatible models ready to be included as modules (

5.4.3), along with open standards that allow for integrating a wide range of data into the systems (

5.4.4). This flexibility in reconfiguring UDTs and integrating models and data necessitates technical integration (

5.4.5), which ultimately places the technical ambitions for UDTs within a socio-technical perspective.

5.4.1. Holistic Representation

To provide a holistic representation, UDTs require models that adopt a comprehensive approach. This entails developing representations that are less fine-grained but more integrated, which are essential for co-creating strategic and long-term visions [

9,

42]. Such models would be less domain-specific and bridge various disciplines in their representation [

10,

53]. Moreover, they need to offer insights at a variety of scales, allowing stakeholders to delve into details as much as necessary, which requires multi-scalar integration of digital representations [

42,

69]. This approach would provide the basis for stakeholders to establish the boundaries of the digital representation independent of domain silos and scale discrepancies, ultimately allowing them to change it dynamically (

5.4.2).

5.4.2. Flexible Representation

To effectively support urban planning—which often involves addressing wicked problems lacking static and clear problem formulations—UDTs must be flexible and adaptable rather than static. As these problems evolve during participatory processes, UDTs need to be reconfigurable to adjust representational boundaries to support evolving needs. Realizing this flexibility requires the ability to use models dynamically by changing their hyper-parameters to better represent stakeholders’ particular views and assumptions as they evolve [

23]. Moreover, it is necessary to switch and reconfigure models as stakeholders’ planning questions evolve [

33]. Achieving such a level of flexibility in model configuration necessitates a wide spectrum of available models that can be readily integrated (

5.4.3).

5.4.3. Model Integration

Because urban environments have complex interdependencies, UDTs must incorporate models from different urban domains to provide holistic and flexible representations [

17,

18]. However, during the preparation, implementation, and integration of these models, it is crucial to avoid neglecting social, cultural, and political complexities. Purely technical approaches often oversimplify by relying solely on quantification to represent urban environments, overlooking important dimensions [

20,

48,

69]. Therefore, a spectrum of models and modeling approaches beyond purely data-driven models is necessary, including semantic models and theory-based models [

48,

69]. Moreover, these models should be curated and interpreted by stakeholders to ensure their use is grounded in local knowledge (

5.3.1) and consensus among local stakholders (

5.3.2). In addition to diverse modeling approaches, flexible use of models requires systematic integration of all computational processes to ensure model integration [

13] and intersystem connectivity [

50], thereby reducing the cost and effort of experimenting with different models. Model integration depends on ensuring that the requirements and assumptions of different models are not conflicting and necessitates a robust framework for data integration (

5.4.4).

5.4.4. Data Integration

Flexibility in customizing and adapting urban representations requires an integrated framework that brings together heterogeneous data from various sources and domains, allowing stakeholders to easily superimpose and compose this data to curate a stakeholder-specific UDT. This process relies firstly on the availability and accessibility of data, which unlocks the ability of stakeholders to construct their own curated, evidence-based representations of the city [

75]. Secondly, it depends on structuring these heterogeneous data based on open standards to lower the barriers to integration and use [

52]. Lastly, it necessitates the adoption of open standards in public data infrastructures and private data services to ensure interoperability within the broader ecosystem of digital tools and services [

28]. Both model integration and data integration, in turn, rely on a robust and integrated ICT infrastructure (

5.4.5).

5.4.5. Technical Integration

With all the social considerations clarified in the agenda, it becomes clear why technical integration is necessary—not to achieve ever more accurate, efficient, fast, or universal digital representations, but to facilitate the socio-technical integrations, namely II, CC, and PO. In this context, adequacy and accuracy [

75] are important insofar as they serve the interdisciplinary integration of stakeholder-specific UDTs (

5.4). Similarly, real-time integration of virtual and real elements [

40] is valuable as it enhances communication, collaboration, and consensus-building among stakeholders (

5.3). Lastly, digital infrastructure is necessary to the extent that it supports the operationalization of UDTs within existing urban planning and decision-making processes (

5.2).

6. Towards a Methdological Framework

The Augmented Urban Planning (AUP) agenda outlines the socio-technical complexities that must be addressed in the development and use of UDTs. However, this agenda alone does not provide a clear roadmap for achieving these objectives. Here, we outline a methodological framework as a first step toward addressing these challenges systematically.

Custom UDTs

the first step is enabling the custom integration of data and models through open, standardized, and modular representations of urban data and models across urban disciplines. This requires explicit representations of the “what,” “where,” “when,” and “who” data pertains to. Additioonally, assumptions and uncertainties inherent in urban models and data need to be made transparent. This would lead to reaching a broad set of building blocks that are standardized to be modular and reconfigurable to lower the threshold for curating and configuring these elements into larger digital representations i.e. UDTs. This flexibility would allow iterative and experimental adjustments, supporting diverse urban planning needs.

Specific UDTs

UDT implementations should move away from the notion of being monolithic and universal representations of urban environments. Recognizing that no representation can ever be perfect, we need to aim for a diverse plathore of specific and useful representations. The aforementioned flexible representations can enable custom UDTs that are tailored to specific planning questions, stakeholders’ views, or communities concerns. With openly standardized and shared building blocks (data and model), this plathora can shape a network of specific UDTs to encompass diverse voices, make communication and collaboration explicit, and support evidence-based co-visioning and co-creation processes, ultimately facilitating convergence of participants toward consensus.

Adaptive UDTs

Neither individual UDTs nor their networks should remain static. UDTs need to be adaptive—not merely in updating data but in continuously evolving through re-curation, re-configuration, and re-interpretation of urban data and models. This adaptability allows for tracing the ever-changing opinions, views, and preferences inherent in participatory urban planning without imposing the rigidity of digital representations on their human-centered processes. Such adaptability requires us to have explicit representation of planning, decision-making, and organizational processes with UDTs embedded in them. Such procedural representions must support a complete cycle: formulating planning questions, modeling UDTs, using them to explore and evaluate scenarios, and iterating across all the previous stages.

Systematic implementation of these will require additional layers of digital representation, making this a substantial and complex undertaking. Yet, to move beyond techno-optimistic visions of UDTs, we must embrace the broader social, cultural, political, legal, ethical, and organizational dimensions of urban environments. What we present here reamins a merely speculative outline—a first step toward reimagining UDTs through a socio-technical lens that recognizes the complexities of integrating technology into urban planning processes.

7. Conclusions

Seven years have passed since Urban Digital Twins (UDTs) were first discussed. Nevertheless, their realized contribution to urban planning and decision-making is still unclear. In this study, we reviewed 84 peer-reviewed implementation and reflection articles to (1) map the ambitions of UDTs for urban planning, (2) map their realized contributions to urban planning, and (3) consolidate an agenda to fill the gap between (1) and (2).

Our mapping of UDTs’ ambitions indicates that the common thread is

integration. Still, there is diversity in how researchers interpret

integration—from technical, data, and model integration to interdisciplinary and procedural (

Section 3). Our analysis of UDTs’ realized contributions shows that the majority focus on technical and interdisciplinary integration, while stakeholder engagement and implementation in actual planning processes are lagging behind (

Section 4). Anlyzing the trends in literature indicates that the field is increasingly aware of this shortfall, with various reflection articles highlighting the necessity to incorporate the social dimension as socio-technical complexities hinder the further operationalization of UDTs in urban governance.

Accordingly, we take the next step by synthesizing the gaps we identified and cross-validate them with the challenges highlighted in the literature to consolidate a socio-technical agenda for further research and development of UDTs: Augmented Urban Planning (AUP) (

Section 5). In short, AUP outlines the ideals where UDTs are a consistent collection of data and models that are Interdisciplinarily Integrated (II), Consensually Contextualized (CC), and Procedurally Operationalized (PO). AUP does not separate ethical, legal, and social dimensions from technical aspects; it adopts an integrated approach to clarify the societal

why we need technical development if we need them.

Funding

This work was carried out under the Urban Development Initiative’s Urban Planning Reimagined (UDI UPR) and supported by the Regio Deal Brainport Eindhoven.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UDTs |

Urban Digital Twins |

| UDTing |

Urban Digital Twinning i.e. process of developing and using UDTs |

| AUP |

Augmented Urban Planning |

| II |

Interdisciplinary Integration |

| CC |

Consensual Contextualization |

| PO |

Procedural Operationalization |

Appendix A. Details of Reviwing UDT Contributions

In our review of the implementation articles, we extracted specific information regarding the contributions of their UDT prototype to urban planning. This assessment was based on extending the main socio-technical categories that emerged from reviewing the ambitions—namely, Interdisciplinary Integration (II), Consensual Contextualization (CC), and Procedural Operationalization (PO).

In assessing contributions to PO, we determined which phases of and practices in urban planning processes the UDT implementations contributed to and how integrative they were. Categorizing the planning practices that UDTs contribute to individual practices like assessment, sensing, actuating, experimenting, and simulating as well more holistic planning practices like formulating problems and modelling digital representations. This analysis allowed us to understand the extent to which the UDTs were operationalized within existing planning processes and how effectively they supported the procedural aspects of urban planning and decision-making.

To evaluate contributions to CC, we examined how the implementations considered stakeholders and how they addressed communication, collaboration, and consensus-building among them. We identified which stakeholders were involved, categorizing them as local authorities, citizens, experts, companies, etc. We also distinguished between cases were the stakeholder was actively engaged, passively consulted, provided indirect inputs, or when only a hypothetical typology of the stakeholder were considered. This assessment provided insight into the level of stakeholder engagement and the strategies used to facilitate their participation.

For assessing contributions to II, we analyzed the functionalities offered by the UDT implementations and the disciplines that data and models from the were used in UDT prototype. We evaluated to what degree data and models were integrated across disciplines. Specifically, we assessed how disciplinary integration was achieved in each UDT—whether they employed single-discipline models and data, single-discipline models with multidiscipline data, or both multidiscipline data and models.

This allowed us to assess the level of integratedness in each of the II, CC, and PO categories. Correspondingly, we think this can be used to evaluate future contributoins of UDTs to urban planning and decision-making based on the AUP socio-technical agenda.

References

- Kumar, S.A.P.; Madhumathi, R.; Chelliah, P.R.; Tao, L.; Wang, S. A novel digital twin-centric approach for driver intention prediction and traffic congestion avoidance. Journal of Reliable Intelligent Environments 2018, 4, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Xu, N. Digital Twin for Sustainability Evaluation of Railway Station Buildings. Frontiers in Built Environment 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M. Digital Twin: Manufacturing Excellence through Virtual Factory Replication 2015.

- Al-Sehrawy, R.; Kumar, B.; Watson, R. A digital twin uses classification system for urban planning and city infrastructure management. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 2021, 26, 832–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketzler, B.; Naserentin, V.; Latino, F.; Zangelidis, C.; Thuvander, L.; Logg, A. Digital Twins for Cities: A State of the Art Review. Built Environment 2020, 46, 547–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, P.C.; Alzamora, F.M.; Carot, M.H.; Campos, J.A. Building and exploiting a Digital Twin for the management of drinking water distribution networks. Urban Water Journal 2020, 17, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, M. Urban development with dynamic digital twins in Helsinki city. IET Smart Cities 2021, 3, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtola, V.V.; Koeva, M.; Elberink, S.O.; Raposo, P.; Virtanen, J.P.; Vahdatikhaki, F.; Borsci, S. Digital twin of a city: Review of technology serving city needs. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2022, 114, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.G.; Guan, C. Advancing Intra and Inter-City Urban Digital Twins: An Updated Review. Journal of Planning Education and Research 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Mavrokapnidis, D.; Ly, H.T.; Mohammadi, N.; Taylor, J.E. Assessing and forecasting collective urban heat exposure with smart city digital twins. Scientific Reports 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, M.; Rajabifard, Abbas anweil2023challengesd Foliente, G. Climate resilient urban regeneration and SDG 11 - stakeholders’ view on pathways and digital infrastructures. International Journal of Digital Earth 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitonidou, M. Urban scale digital twins in data-driven society: Challenging digital universalism in urban planning decision-making. International Journal of Architectural Computing 2022, 20, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Janssen, P.; Stoter, J.; Biljecki, F. Challenges of urban digital twins: A systematic review and a Delphi expert survey. Automation in Construction 2023, 147, 104716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oti-Sarpong, K.; Bastidas, V.; Nochta, T.; Wan, L.; Tang, J.; Schooling, J. A Social Construction of Technology View for Understanding the Delivery of City-Scale Digital Twins. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2022, X-4/W3-2022, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzati, S. No longer hype, not yet mainstream? Recalibrating city digital twins’ expectations and reality: a case study perspective. Frontiers in Big Data 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, W.; Cornelissen, H.; Borst, J.; Klerkx, R.; Araghi, Y.; Walraven, E. Building digital twins of cities using the Inter Model Broker framework. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023, 148, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagap, U.; Ghaffarian, S. Digital post-disaster risk management twinning: A review and improved conceptual framework. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2024, 110, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peldon, D.; Banihashemi, S.; LeNguyen, K.; Derrible, S. Navigating urban complexity: The transformative role of digital twins in smart city development. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 111, 105583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Alomari, I.; Taffese, W.Z.; Shi, Z.; Afsharmovahed, M.H.; Mondal, T.G.; Nguyen, S. Multifunctional Models in Digital and Physical Twinning of the Built Environment—A University Campus Case Study. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 836–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quek, H.Y.; Sielker, F.; Akroyd, J.; Bhave, A.N.; von Richthofen, A.; Herthogs, P.; Yamu, C.v.d.L.; Wan, L.; Nochta, T.; Burgess, G.; et al. The conundrum in smart city governance: Interoperability and compatibility in an ever-growing ecosystem of digital twins. Data and Policy 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zhang, C.; Yahja, A.; Mostafavi, A. Disaster City Digital Twin: A vision for integrating artificial and human intelligence for disaster management. International Journal of Information Management 2021, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nochta, T.; Wan, L.; Schooling, J.M.; Parlikad, A.K. A Socio-Technical Perspective on Urban Analytics: The Case of City-Scale Digital Twins. International Journal of Urban Sciences 2020, 28, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcucci, E.; Gatta, V.; Pira, M.L.; Hansson, L.; Bråthen, S. Digital Twins: A Critical Discussion on Their Potential for Supporting Policy-Making and Planning in Urban Logistics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Kim, H. Urban digital twin applications as a virtual platform of smart city. International Journal of Sustainable Building Technology and Urban Development 2021, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. The Seductive Smart City and the Benevolent Role of Transparency. Interaction Design and Architecture(s) 2021, 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Huang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Li, J.; Cai, Z. Collaborative city digital twin for the COVID-19 pandemic: A federated learning solution. Tsinghua Science and Technology 2021, 26, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, L.; Michiels, P.; Adolphi, T.; Tampere, C.; Dalianis, T.; Mcaleer, S.; Kogut, P. DUET: A Framework for Building Secure and Trusted Digital Twins of Smart Cities. IEEE Internet Computing 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yossef Ravid, B.; Aharon-Gutman, M. The Social Digital Twin:The Social Turn in the Field of Smart Cities. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 2022, 50, 1455–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adade, D.; de Vries, W.T. An extended TOE framework for local government technology adoption for citizen participation: insights for city digital twins for collaborative planning. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pultrone, G. The city challenges and the new frontiers of urban planning. TeMA - Journal of Land Use 2023, 16, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenheim, N.; Sabri, S.; Chen, Y.; Kesmanis, A.; Felson, A.; Mueller, A.; Rajabifard, A.; Zhang, Y. Adapting a Digital Twin to Enable Real-Time Water Sensitive Urban Design Decision-Making. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2022, XLVIII-4/W4-2022, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Du, J.; Han, Y.; Newman, G.; Retchless, D.; Zou, L.; Ham, Y.; Cai, Z. Developing Human-Centered Urban Digital Twins for Community Infrastructure Resilience: A Research Agenda. Journal of Planning Literature 2022, 38, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, A.N.; Borup, M.; Brink-Kjær, A.; Christiansen, L.E.; Mikkelsen, P.S. Living and Prototyping Digital Twins for Urban Water Systems: Towards Multi-Purpose Value Creation Using Models and Sensors. Water 2021, 13, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HosseiniHaghighi, S.; de Uribarri, P.M.A.; Padsala, R.; Eicker, U. Characterizing and structuring urban GIS data for housing stock energy modelling and retrofitting. Energy and Buildings 2022, 256, 111706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yang, B. GIS-Enabled Digital Twin System for Sustainable Evaluation of Carbon Emissions: A Case Study of Jeonju City, South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsson, J.; Atta, K.T.; Schweiger, G.; Birk, W. Experiences from City-Scale Simulation of Thermal Grids. Resources 2021, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, Y.; Mao, Z.; Hu, M.; Sugumaran, V.; Wang, Y.K. A digital twin-based decision analysis framework for operation and maintenance of tunnels. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 2021, 116, 104125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Jia, F.; Cheng, X. Digital twin-supported smart city: Status, challenges and future research directions. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 217, 119531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfadel, A.; Hörl, S.; Tapia, R.J.; Politaki, D.; Kureshi, I.; Tavasszy, L.; Puchinger, J. A conceptual digital twin framework for city logistics. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2023, 103, 101989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccardo, P.; La Riccia, L.; Yadav, Y. Urban Echoes: Exploring the Dynamic Realities of Cities through Digital Twins. Land 2024, 13, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprari, G.; Castelli, G.; Montuori, M.; Camardelli, M.; Malvezzi, R. Digital Twin for Urban Planning in the Green Deal Era: A State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson-Smith, A.; Batty, M. Ubiquitous geographic information in the emergent Metaverse. Transactions in GIS 2022, 26, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziehl, M.; Herzog, R.; Degkwitz, T.; Niggemann, M.H.; Ziemer, G.; Thoneick, R. Transformative Research in Digital Twins for Integrated Urban Development: Two Real-World Experiments on Unpaid Care Workers Mobility. International Journal of E-Planning Research 2023, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, C.R.; DeLong, S.M.; Holt, E.G.; Hua, E.Y.; Tolk, A. Combining Green Metrics and Digital Twins for Sustainability Planning and Governance of Smart Buildings and Cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astarita, V.; Guido, G.; Haghshenas, S.S.; Haghshenas, S.S. Risk Reduction in Transportation Systems: The Role of Digital Twins According to a Bibliometric-Based Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzachor, A.; Sabri, S.; Richards, C.E.; Rajabifard, A.; Acuto, M. Potential and limitations of digital twins to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nature Sustainability 2022, 5, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Jin, Y.; Echenique, M.; Batty, M.; Wegener, M. From urban modelling to city digital twins - Reflections from the applied urban modelling (AUM) symposia. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, P.; Xu, X. Literature review of digital twin technologies for civil infrastructure. Journal of Infrastructure Intelligence and Resilience 2023, 2, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E.; Huang, J.; Jagatheesaperumal, S.K.; Krogstie, J. The synergistic interplay of artificial intelligence and digital twin in environmentally planning sustainable smart cities: A comprehensive systematic review. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2024, 20, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Kang, J. Participatory Framework for Urban Pluvial Flood Modeling in the Digital Twin Era. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 108, 105496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeister, M.; Lee, K.F.; Tsai, Y.K.; Müller, M.; Nagarajan, K.; Mosbach, S.; Akroyd, J.; Kraft, M. Dynamic control of district heating networks with integrated emission modelling: A dynamic knowledge graph approach. Energy and AI 2024, 17, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, Y.; Hajduk, P.; Horak, T.; Pithartova, K.; Rantala, S.; Farzam Far, M. Virtual piloting of vehicle fleets to accelerate the green transition in logistics. Transportation Planning and Technology 2024, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, D.J.; Polesel, F.; Refstrup Sørensen, H.; Gustafsson, L.G. Connecting digital twins to control collections systems and water resource recovery facilities: From siloed to integrated urban (waste)water management. Water Practice and Technology 2024, 19, 2267–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Berres, A.; Yoginath, S.B.; Sorensen, H.; Nugent, P.J.; Severino, J.; Tennille, S.A.; Moore, A.; Jones, W.; Sanyal, J. Smart Mobility in the Cloud: Enabling Real-Time Situational Awareness and Cyber-Physical Control Through a Digital Twin for Traffic. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023, 24, 3145–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cureton, P.; Hartley, E. City Information Models (CIMs) as precursors for Urban Digital Twins (UDTs): A case study of Lancaster. Frontiers in Built Environment 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, A.; Fernandes, P.; Guerreiro, A.P.; Tomás, R.; Agnelo, J.; Santos, J.L.; Araújo, F.; Coelho, M.C.; Fonseca, C.M.; d’Orey, P.M.; et al. MobiWise: Eco-routing decision support leveraging the Internet of Things. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 87, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, S.; Pallonetto, F.; De Donatis, L.; De Rosa, M. District energy modelling for decarbonisation strategies development—The case of a University campus. Energy Reports 2024, 11, 1256–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clementi, M.; Dessì, V.; Podestà, G.M.; Chien, S.C.; Wei, B.A.T.; Lucchi, E. GIS-Based Digital Twin Model for Solar Radiation Mapping to Support Sustainable Urban Agriculture Design. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, P.; Mosteiro-Romero, M.; Miller, C.; Stouffs, R. Mitigating operational greenhouse gas emissions in ageing residential buildings using an Urban Digital Twin dashboard. Energy and Buildings 2024, 322, 114681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiullari, D.; Nageli, C.; Rudena, A.; Isacson, A.; Dokter, G.; Ellenbroek, I.; Wallbaum, H.; Thuvander, L. Digital twin for supporting decision-making and stakeholder collaboration in urban decarbonization processes. A participatory development in Gothenburg. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Qin, W.; Luo, H.; Yu, Q.; Fan, B.; Zheng, Q. Digital twin for smart metro service platform: Evaluating long-term tunnel structural performance. Automation in Construction 2024, 167, 105713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Liu, P.; Cao, L. Coupling a Physical Replica with a Digital Twin: A Comparison of Participatory Decision-Making Methods in an Urban Park Environment. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2022, 11, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembski, F.; Wssner, U.; Letzgus, M.; Ruddat, M.; Yamu, C. Urban Digital Twins for Smart Cities and Citizens: The Case Study of Herrenberg, Germany. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, L.; Schweiger, L.; Benedech, R.; Ehrat, M. From data to value in smart waste management: Optimizing solid waste collection with a digital twin-based decision support system. Decision Analytics Journal 2023, 9, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.M.; Kuriqi, A.; Coronado-Hernández, O.E.; López-Jiménez, P.A.; Pérez-Sánchez, M. Are digital twins improving urban-water systems efficiency and sustainable development goals? Urban Water Journal 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Y.; Chew, A.; Meng, X.; Cai, J.; Pok, J.; Kalfarisi, R.; Lai, K.C.; Hew, S.F.; Wong, J.J. High Fidelity Digital Twin-Based Anomaly Detection and Localization for Smart Water Grid Operation Management. Sustainable Cities and Society 2023, 91, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Ma, L.; Broyd, T.; Chen, W.; Luo, H. Digital twin enabled sustainable urban road planning. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 78, 103645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, C.; Bibri, S.E.; Longchamp, R.; Golay, F.; Alahi, A. Urban Digital Twin Challenges: A Systematic Review and Perspectives for Sustainable Smart Cities. Sustainable Cities and Society 2023, 99, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, M.; Rajabifard, A.; Foliente, G. Urban regeneration and placemaking: a Digital Twin enhanced performance-based framework for Melbourne’s Greenline Project? Australian Planner 2023, 59, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, R.; Ashtari, M.A.; Aziminezhad, M. Digital Twin-Enabled Infrastructures: A Bibliometric Analysis-Based Review. Journal of Infrastructure Systems 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leplat, L.; López-Alfaro, C.; Styve, A.; da Silva Torres, R. NorDark-DT: A digital twin for urban lighting infrastructure planning and analysis. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 2024, 0, 23998083241272099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.W.; Guo, S.S.; Xu, W.X.; Du, B.G.; Liang, J.Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.B. Digital Twin-Based Pump Station Dynamic Scheduling for Energy-Saving Optimization in Water Supply System. Water Resources Management 2024, 38, 2773–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, B.; Cai, H.; Khayatian, F.; Munoz, E.; An, J.; Mutschler, R.; Sulzer, M.; De Wolf, C.; Orehounig, K. Digitalization of urban multi-energy systems - Advances in digital twin applications across life-cycle phases. Advances in Applied Energy 2024, 16, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, V. Energy transition: digital (t)win? TeMA - Journal of Land Use 2023, 16, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).