1. Introduction

Juvenile scleroderma (JSD) is a rare chronic multisystem connective tissue disease in children. Its clinical presentation ranges from localized lesions to severe, rapidly progressing pathological processes involving multiple organs in children under 18 years of age [

1]. The condition is characterized by symmetrical skin thickening and hardening, fibrotic changes in vascular walls, and internal organ fibrosis [

2]. In children, localized scleroderma is the most observed form. It is characterized by the presence of localized inflammatory lesions in various areas of the skin, initially manifesting as erythema and edema, followed by the development of atrophy of the skin and subcutaneous tissues [

3,

4,

5]. Beyond skin and organ involvement, one of the manifestations of juvenile scleroderma is calcinosis, defined as the deposition of crystals of hydroxyapatite and calcium phosphate in the extracellular matrix of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. This condition presents a significant therapeutic challenge in the management of such patients [

6]. According to the literature, the pathophysiology of calcification in scleroderma remains an active area of research [

4]. Studies have demonstrated a direct correlation between the presence and progression of calcinosis and inflammation, evidenced by elevated serum levels of interleukins (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-

), the development of hypoxia and increased osteoclast activity [

7,

8]. In juvenile scleroderma, calcinosis typically develops in the joint areas, presenting as subcutaneous nodules ranging from a few millimeters in diameter to much larger sizes, particularly when large joints are involved [

9]. Advancements in the treatment of scleroderma, including calcinosis, have focused on improving both pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies. However, the management of calcinosis remains a significant unresolved challenge, as no specific methods have been developed to effectively target the formation of lesions or the progression of calcification [

10]. According to the 2024 Guidelines of the British Society for Rheumatology on the treatment of systemic scleroderma, the following strategies are recommended for managing calcinosis in scleroderma [

11]:

Early detection and treatment of secondary infection associated with calcinosis should be prioritized, using proper antibiotic therapy (Grade 1C, 99%).

Surgical intervention should be considered in cases of severe, refractory calcinosis that significantly impairs functional ability and quality of life.

2. Case Report

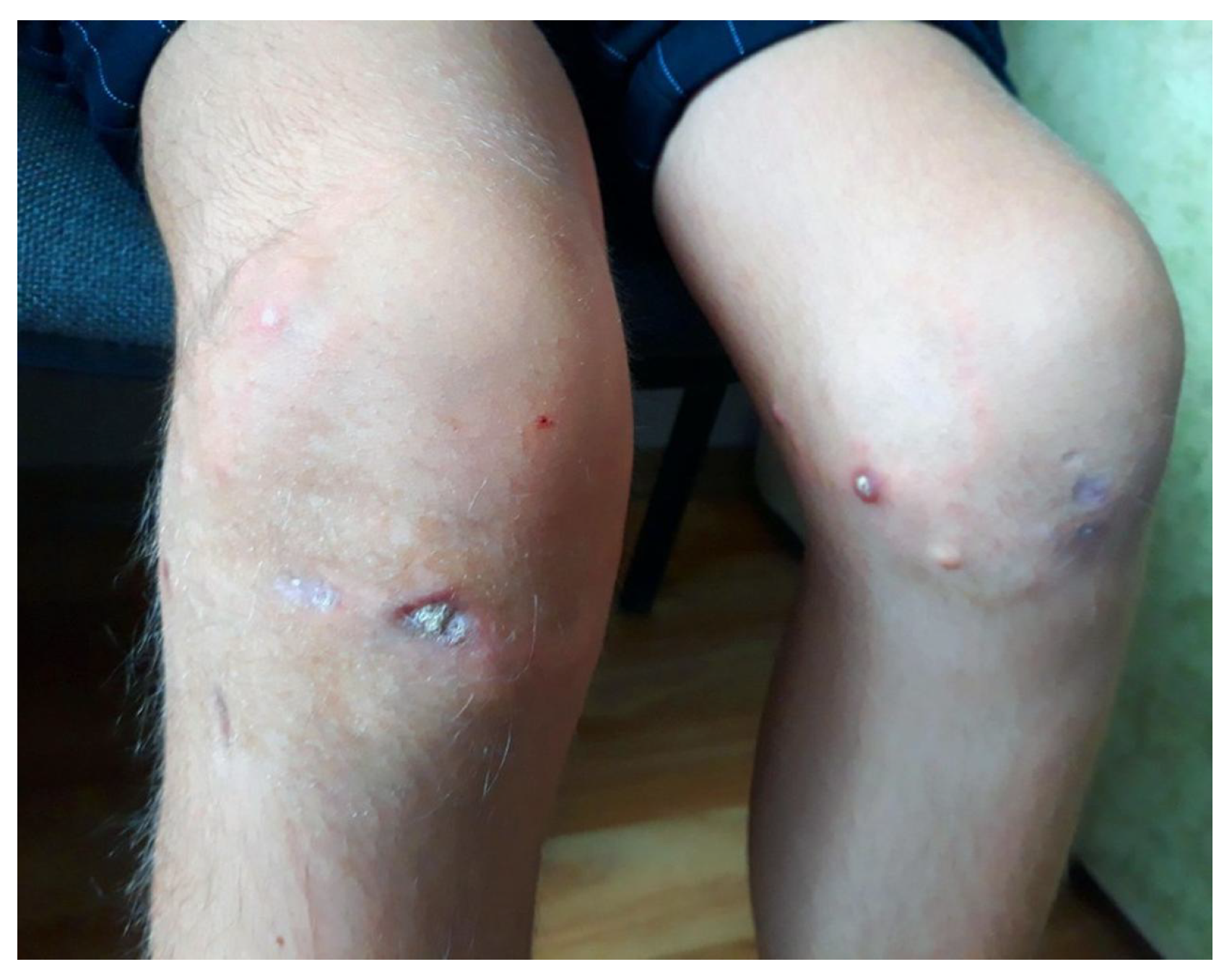

Patient V., a 15-year-old girl born in 2009, has been under observation at the clinic since 2017. Her illness began in 2016 following a bout of furunculosis, after which she first presented with complaints of atrophic changes in the skin of her phalanges, stiffness in the palms and fingers of both hands, and deformity of the knee joints. A year later, she developed multiple dense subcutaneous nodules of rounded shape, measuring 2x2 mm, located on the anterior surface of the knees (

Figure 1), along with periodic headaches.

The patient reported no difficulty swallowing liquids or solid foods, abdominal pain, or constipation. Her family history is notable for autoimmune conditions: a maternal great-aunt with arthritis and a great-grandmother with psoriasis.

In December 2017, the patient was admitted to the pediatric department for evaluation. Laboratory findings revealed anemia, leukopenia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), increased antinuclear antibody (ANA) titers (1:320), negative IgG antibodies to Scl-70, and a decreased C3 complement component.

The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a sinus rhythm with a normal cardiac axis and moderate repolarization abnormalities.

A longitudinal anterior suprapatellar B-mode scan of the knee joints revealed moderate effusion, elevating the prepatellar fat pad and extending proximally to encompass approximately 60% of the visible quadriceps tendon. Power Doppler imaging showed no detectable signal (Grade 0).

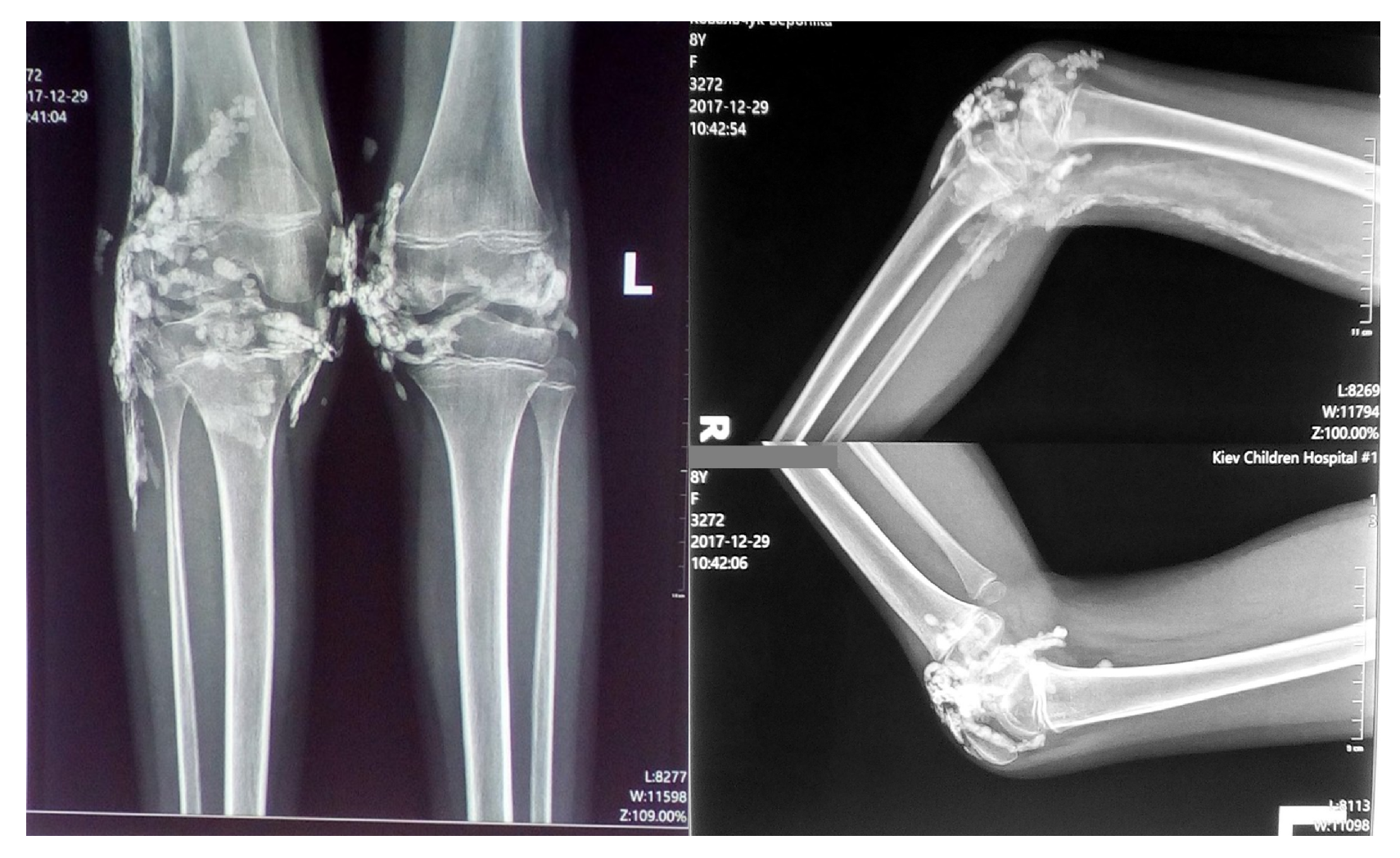

Radiographic examination of the knee joints in two projections revealed multiple small, rounded high-density shadows with well-defined, smooth contours in the projection of the knee joints and synovial recesses. Soft tissue changes were observed along the posterior-lateral surface of the distal femur and the proximal right ankle, characterized by a "feathery" pattern consistent with calcification and/or ossification (

Figure 2).

Echocardiography demonstrated an ejection fraction of 64%, first-degree mitral valve prolapse, first-degree mitral regurgitation, and an aberrant diagonal chord in the left ventricle.

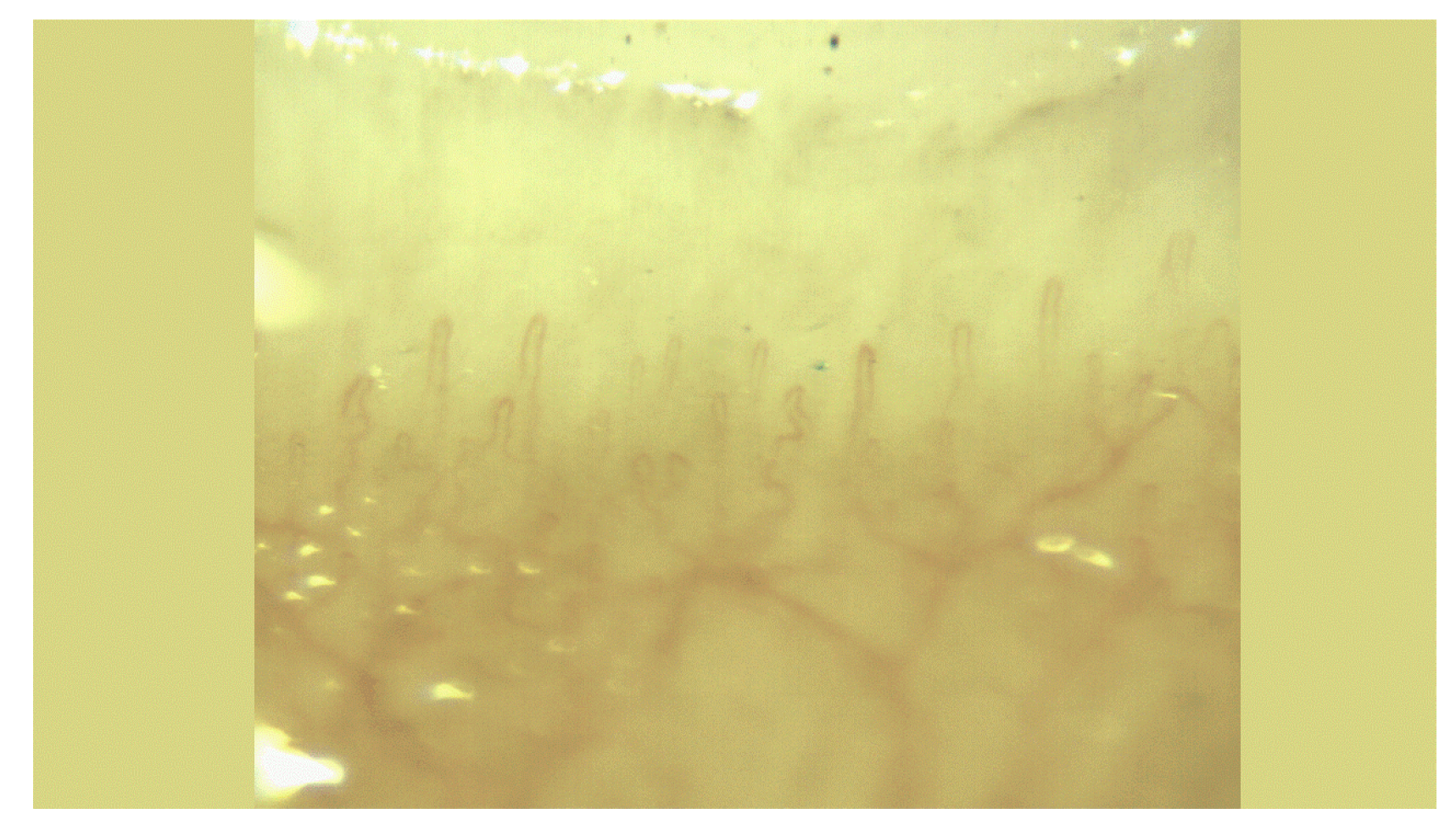

Figure 3 illustrates a slow-progressing scleroderma-type capillary pattern observed through capillaroscopy, along with Raynaud’s phenomenon stage 1.

A skin biopsy from the left knee joint area revealed extensive calcific deposits, significant fibrotic changes, evidence of microvasculitis, and focal disorganization of the connective tissue. These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of a systemic inflammatory connective tissue disease. A chest X-ray showed no pathological abnormalities, and fibrogastroscopy revealed no notable findings.

Based on the examination findings, the diagnosis was established as juvenile systemic scleroderma (M34.0), limited form, with a subacute and rapidly progressive course, activity level 2. The disease manifestations included skin and subcutaneous tissue involvement (subcutaneous calcinosis), oligoarthritis of the knee joints, stage 1 Raynaud’s phenomenon, and stage 2 anemia.

In accordance with the 2017 clinical guidelines for the treatment of juvenile systemic scleroderma, the following treatment regimen was prescribed:

- -

Methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg for 1 month, followed by gradual dose reduction

- -

Iloprost, 10 intravenous injections

- -

Methotrexate 12.5 mg/m²

- -

Folic acid 5 mg every other day following methotrexate administration

- -

Symptomatic analgesic therapy

6 months later, while on methylprednisolone (4 mg daily) and methotrexate (12.5 mg weekly), the patient developed bilateral pneumonia after an acute respiratory infection, which necessitated antibiotic therapy. While undergoing treatment, she developed an infection in the knee area affected by calcinosis, which progressed to phlegmon. Bilateral pneumonia reocurred, and sepsis was diagnosed. The patient received antibacterial therapy, local treatment, and symptomatic management. Methotrexate was discontinued, and chloroquine was initiated.

In 2019, the patient was prescribed methylprednisolone 4 mg/day, chloroquine, and a vitamin K2 supplement (300 mcg/day). Laboratory tests, reflecting the inflammatory activity of the disease, showed normal results, with hemoglobin within the reference range and leukocytes at .

However, calcific lesions developed in the elbow joints (

Figure 4) and increased in size around the knee joints. Periodic subfebrile temperatures were noted, along with localized inflammation in the skin and subcutaneous tissue areas affected by calcifications. The levels of interleukin-6 and TNF-

were measured and found to be within normal limits at the time of assessment.

Immunological blood tests were performed, with the findings summarized in

Table 1.

An additional diagnosis of secondary immunodeficiency was made. The treatment plan included intravenous immunoglobulin at a dose of 0.4 g/kg for 3 days (total dose 1 g/kg) in the inpatient setting, followed by a monthly continuation of 2 g/kg in the hospital. Additionally, cotrimoxazole 480 mg was prescribed twice daily after meals with adequate fluid intake for 3 months. The patient’s condition stabilized, and the inflammatory processes subsided. Subsequently, surgical removal of calcifications from the superficial structures of the right knee and elbow joints was performed. However, intra-articular calcifications, as well as calcifications within the tendons and tendon sheaths of the left knee joint, emerged, leading to impaired joint mobility.

No signs of synovitis were observed. Calcinosis was present in the left knee joint cavity and in the intermuscular space of the right thigh (involving one-third of the femur). Capillaroscopy revealed a scleroderma-type capillaroscopic pattern and Raynaud’s phenomenon stage 1, with no negative changes compared to previous findings.

3. Discussion

After 7 years of disease progression in this patient with scleroderma, the overall inflammatory process has been successfully controlled. However, the progression of subcutaneous calcinosis persists and continues to spread unabated.

This case of JSD illustrates the intricate interplay between the inflammatory, fibrotic, and calcific components of the disease, which complicates its management.

The persistent progression of subcutaneous calcinosis, despite ongoing pharmacological treatment and surgical intervention, highlights the current limitations in therapeutic strategies for this condition. While the pathophysiology of calcinosis in JSD remains an active area of research[

4], with evidence suggesting a link between inflammation and calcification, the lack of targeted treatments underscores the need for innovative approaches.

Immune dysregulation, including elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, plays a critical role in both disease progression and calcification, suggesting that therapies aimed at modulating the immune response could potentially alter the course of the disease.

Furthermore, advancements in imaging techniques may enable earlier detection and more precise monitoring of calcinosis, potentially improving treatment outcomes. Despite the challenges, surgical removal of calcific lesions remains a cornerstone of management, particularly when lesions impair joint function [

10].

Future research should focus on developing therapies that directly target the mechanisms underlying calcification, alongside further exploration of individualized, multi-disciplinary approaches to better control both the inflammatory and calcific aspects of juvenile scleroderma.

4. Conclusions

We presented a case of juvenile systemic scleroderma complicated by progressive subcutaneous calcinosis, which despite ongoing pharmacological treatment and surgical intervention, continued to spread. This case highlights the need for more targeted therapies to manage calcinosis, as current methods remain insufficient. Based on this experience, we strongly recommend exploring new treatment strategies aimed at directly addressing the pathophysiological mechanisms of calcification, including immune modulation and advanced imaging. Additionally, we suggest considering a multi-disciplinary approach that combines pharmacological, surgical, and emerging therapies to better control both the inflammatory and calcific aspects of juvenile systemic scleroderma.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.; methodology, Y.M.; software, Y.-E.K.; validation, T.M. and Y.M.; formal analysis, T.M.; data curation, T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-E.K.; writing—review and editing, T.K.; visualization, Y.-E.K.; supervision, T.K.; project administration, Y.-E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from both the patient and her parents to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reason.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANA |

Anti-nuclear antibodies |

| ESR |

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| C3 |

Complement C3 |

| JSD |

Juvenile scleroderma |

References

- Tirelli, F.; Zanatta, E.; Moccaldi, B.; Binda, M.; Martini, G.; Giraudo, C.; Vittadello, F.; Meneghel, A.; Zulian, F. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma is more aggressive in children than in adults. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2024, 63, SI2, SI215–SI218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulian, F.; Lanzoni, G.; Castaldi, B.; Meneghel, A.; Tirelli, F.; Zanatta, E.; Martini, G. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma in children. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022, 61, 2555–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S. C. Scleroderma in children and adolescents: Localized Scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2018, 65, 757–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, G.; Fadanelli, G.; Agazzi, A.; Vittadello, F.; Meneghel, A.; Zulian, F. Disease course and long-term outcome of juvenile localized scleroderma: Experience from a single pediatric rheumatology Centre and literature review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018, 17, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pain, C. E.; Torok, K. S. Challenges and complications in juvenile localized scleroderma: A practical approach. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2024, 38, 101987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elahmar, H.; Feldman, B. M.; Johnson, S. R. Management of calcinosis cutis in rheumatic diseases. J. Rheumatol. 2022, 49, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muktabhant, C.; Thammaroj, P.; Chowchuen, P.; Foocharoen, C. Prevalence and clinical association with calcinosis cutis in early systemic sclerosis. Mod. Rheumatol. 2021, 31, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, A.; Baron, M.; Rodriguez-Reyna, T. S.; Proudman, S.; Khanna, D.; Young, A.; Hinchcliff, M.; Steen, V.; Gordon, J.; Hsu, V.; Castelino, F. V.; Schoenfeld, S.; Li, S.; Wu, J. Y.; Fiorentino, D.; Chung, L. Calcinosis is associated with ischemic manifestations and increased disability in patients with systemic sclerosis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2020, 50, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davuluri, S.; Lood, C.; Chung, L. Calcinosis in systemic sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2022, 34, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Galdo, F.; Lescoat, A.; Conaghan, P. G.; Bertoldo, E.; Čolić, J.; Santiago, T.; Suliman, Y. A.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Gabrielli, A.; Distler, O.; Hoffmann-Vold, A. M.; Castellví, I.; Balbir-Gurman, A.; Vonk, M.; Ananyeva, L.; Rednic, S.; Tarasova, A.; Ostojic, P.; Boyadzhieva, V.; El Aoufy, K.; Farrington, S.; Galetti, I.; Denton, C. P.; Kowal-Bielecka, O.; Mueller-Ladner, U.; Allanore, Y. EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis: 2023 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, ard-2024-226430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, C. P.; De Lorenzis, E.; Roblin, E.; Goldman, N.; Alcacer-Pitarch, B.; Blamont, E.; Buch, M. H.; Carulli, M.; Cotton, C.; Del Galdo, F.; Derrett-Smith, E.; Douglas, K.; Farrington, S.; Fligelstone, K.; Gompels, L.; Griffiths, B.; Herrick, A.; Hughes, M.; Pain, C.; Pantano, G.; Pauling, J. D.; Prabu, A.; O’Donoghue, N.; Renzoni, E. A.; Royle, J.; Samaranayaka, M.; Spierings, J.; Tynan, A.; Warburton, L.; Ong, V. H. The 2024 British Society for Rheumatology guideline for management of systemic sclerosis—executive summary. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2024, 63, 2948–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).