Submitted:

05 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

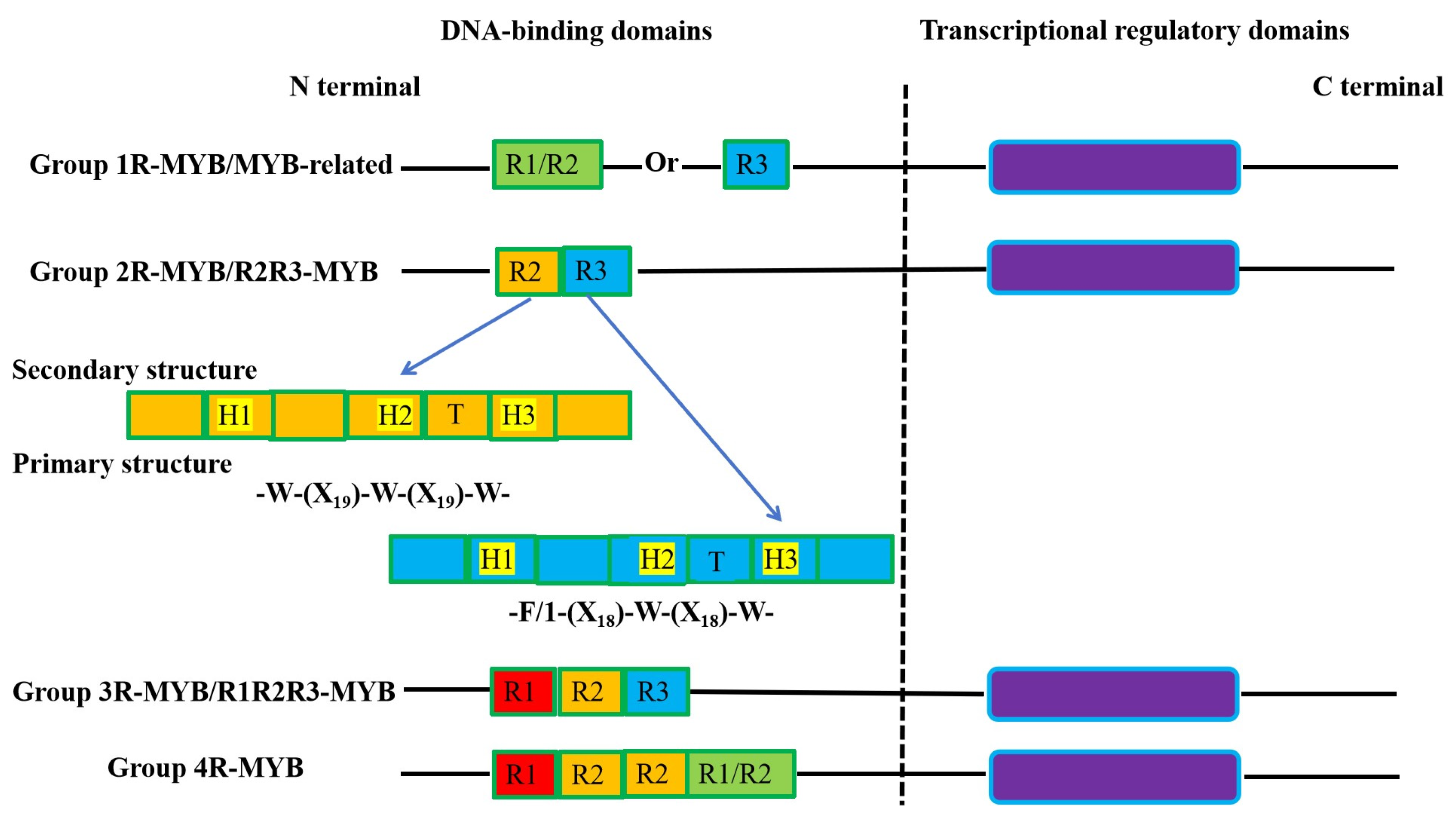

1.1. The structure and classification of the plant MYB transcription factors

2. Role of MYB transcription factors hormone metabolism in plants

3. Mode of action of MYB transcription factors in plants

4. Role of MYB transcription factors in response to abiotic stresses

4.1. MYB transcription factors in response to drought stress

4.2. Molecular mechanisms of MYB transcription factors associated with salt stress

4.3. MYB transcription factors involved in plant response to temperature stress

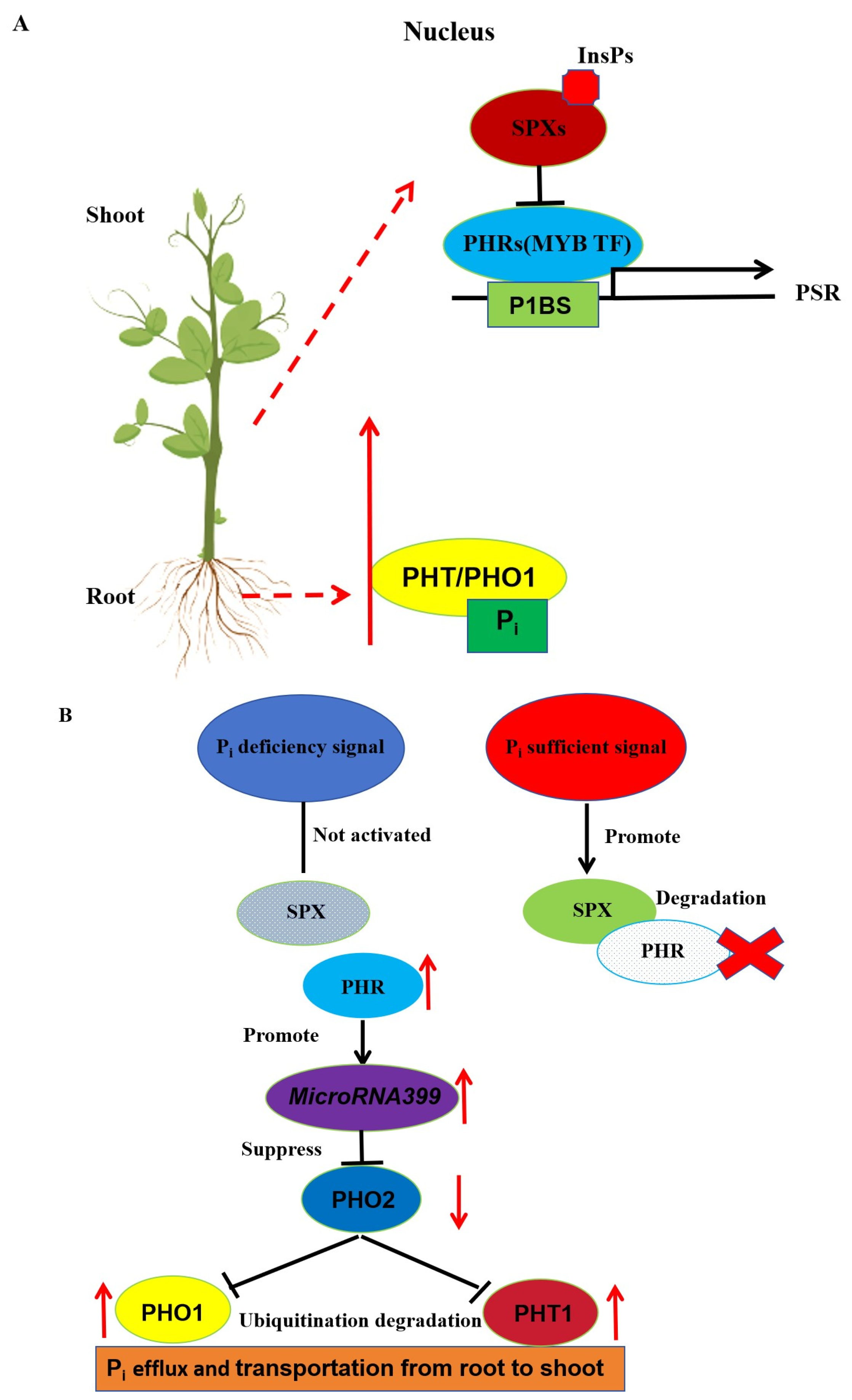

4.4. Role of Plant MYB transcription factors in Response to Nutritional element stress

4.5. MYB transcription factors Involved in Plant Response to heavy metals stress

5. Conclusion and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, H.; Lu, Q.; Huang, K. Selenium suppressed hydrogen peroxide-induced vascular smooth muscle cells calcification through inhibiting oxidative stress and ERK activation. J Cell Biochem. 2010, 111, 1556-64.

- Bayliak, M.M.; Demianchuk, O.I.; Gospodaryov, D.V.; Abrat, O.B.; Lylyk, M.P.; Storey, K.B.; Lushchak, V.I. Mutations in genes cnc or dKeap1 modulate stress resistance and metabolic processes in Drosophila melanogaster. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2020, 248, 110746.

- Shan, W.; Kuang, J.F.; Lu, W.J.; Chen, J.Y. Banana fruit NAC transcription factor MaNAC1 is a direct target of MaICE1 and involved in cold stress through interacting with MaCBF1. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 2116-27.

- Ma, Z.; Hu, L. MicroRNA: A Dynamic Player from Signalling to Abiotic Tolerance in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 11364.

- Ma, Z.; Hu, L.; Jiang, W. Understanding AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Responses and Tolerance to Various Abiotic Stresses in Plants: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 893.

- Ma, Z.; Hu, L. WRKY Transcription Factor Responses and Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 6845.

- Liu, J.; Osbourn, A.; Ma, P. MYB Transcription Factors as Regulators of Phenylpropanoid Metabolism in Plants. Mol Plant. 2015, 8, 689-708.

- Pratyusha, D.S.; Sarada, D.V.L. MYB transcription factors-master regulators of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and diverse developmental and stress responses. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 2245-2260.

- Ambawat, S.; Sharma, P.; Yadav, N.R.; Yadav, R.C. MYB transcription factor genes as regulators for plant responses: an overview. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2013, 19, 307-21.

- Wang, X.; Niu, Y.; Zheng, Y. Multiple Functions of MYB Transcription Factors in Abiotic Stress Responses. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 6125.

- Li, X.; Guo, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, G.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Hu, Z.; Sun, J.; Gao, J.; Yang, A.; Pu, W.; Wen, L. Deciphering the roles of tobacco MYB transcription factors in environmental stress tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 998606.

- Ogata, K.; Morikawa, S.; Nakamura, H.; Hojo, H.; Yoshimura, S.; Zhang, R.; Aimoto, S.; Ametani, Y.; Hirata, Z.; Sarai, A.; et al. Comparison of the free and DNA-complexed forms of the DNA-binding domain from c-Myb. Nat Struct Biol. 1995, 2, 309-20.

- Yang, J.; Zhang, B.; Gu, G.; Yuan, J.; Shen, S.; Jin, L.; Lin, Z.; Lin, J.; Xie, X. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the R2R3-MYB gene family in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). BMC Genomics. 2022, 23, 432.

- Paz-Ares, J.; Ghosal, D.; Wienand, U.; Peterson, P.A.; Saedler, H. The regulatory c1 locus of Zea mays encodes a protein with homology to myb proto-oncogene products and with structural similarities to transcriptional activators. EMBO J. 1987, 6, 3553-8.

- Muthuramalingam, P.; Jeyasri, R.; Selvaraj, A.; Shin, H.; Chen, J.T.; Satish, L.; Wu, Q.S.; Ramesh, M. Global Integrated Genomic and Transcriptomic Analyses of MYB Transcription Factor Superfamily in C3 Model Plant Oryza sativa (L.) Unravel Potential Candidates Involved in Abiotic Stress Signaling. Front Genet. 2022, 13, 946834.

- Chen, C.; Zhang, K.; Khurshid, M.; Li, J.; He, M.; Georgiev, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, M. MYB transcription repressors regulate plant secondary metabolism. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2019, 38, 159–170.

- Wang, Z.; Peng, Z.; Khan, S.; Qayyum, A.; Rehman, A.; Du, X. Unveiling the power of MYB transcription factors: Master regulators of multi-stress responses and development in cotton. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024, 276, 133885.

- Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Fan, Z.; Qu, X.; Yan, M.; Zhang, C.; Yang, K.; Zou, J.; Le, J. The rice R2R3 MYB transcription factor FOUR LIPS connects brassinosteroid signaling to lignin deposition and leaf angle. Plant Cell. 2024, 36, 4768-4785.

- Du, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Tang, X.F.; Yang, W.J.; Wu, Y.M.; Huang, Y.B.; Tang, Y.X. Biochemical and molecular characterization of plant MYB transcription factor family. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2009, 74, 1-11.

- Prusty, A.; Panchal, A.; Singh, R.K.; Prasad, M. Major transcription factor families at the nexus of regulating abiotic stress response in millets: a comprehensive review. Planta. 2024, 259, 118.

- Wu, Y.; Wen, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, L.; Du, H. Evolution and functional diversification of R2R3-MYB transcription factors in plants. Hortic Res. 2022, 9, uhac058.

- Chen, Y.H.; Yang, X.Y.; He, K.; Liu, M.H.; Li, J.G.; Gao, Z.F.; Lin, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.F.; Wang, X.X.; Qiu, X.M.; Shen, Y.P.; Zhang, L.; Deng, X.H.; Luo, J.C.; Deng, X.W.; Chen, Z.L.; Gu, H.Y.; Qu, L.J. The MYB transcription factor superfamily of Arabidopsis: expression analysis and phylogenetic comparison with the rice MYB family. Plant Mol Biol. 2006, 60, 107-24.

- Kang, L.; Teng, Y.; Cen, Q.; Fang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Xue, D. Genome-Wide Identification of R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor and Expression Analysis under Abiotic Stress in Rice. Plants (Basel). 2022, 11, 1928.

- Du, H.; Yang, S.S.; Liang, Z.; Feng, B.R.; Liu, L.; Huang, Y.B.; Tang, Y.X. Genome-wide analysis of the MYB transcription factor superfamily in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 106.

- Stracke, R.; Holtgräwe, D.; Schneider, J.; Pucker, B.; Sörensen, T.R.; Weisshaar, B. Genome-wide identification and characterisation of R2R3-MYB genes in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris). BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 249.

- Li, Z.; Peng, R.; Tian, Y.; Han, H.; Xu, J.; Yao, Q. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the MYB Transcription Factor Superfamily in Solanum lycopersicum. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 1657-77.

- Chen, G.; He, W.; Guo, X.; Pan, J. Genome-Wide Identification, Classification and Expression Analysis of the MYB Transcription Factor Family in Petunia. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 4838.

- Xia, H.; Liu, X.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.; Wang, T.; Deng, H.; Wang, J.; Lin, L.; Deng, Q.; Lv, X.; Xu, K.; Liang, D. Genome-Wide Identification of MYB Transcription Factors and Screening of Members Involved in Stress Response in Actinidia. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 2323.

- Arce-Rodríguez, M.L.; Martínez, O.; Ochoa-Alejo, N. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the MYB Transcription Factor Gene Family in Chili Pepper (Capsicum spp.). Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 2229.

- Tan, L.; Ijaz, U.; Salih, H.; Cheng, Z.; Ni Win Htet, N.; Ge, Y.; Azeem, F. Genome-Wide Identification and Comparative Analysis of MYB Transcription Factor Family in Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. Plants (Basel). 2020, 9, 413.

- Xie, F.; Hua, Q.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, J.; Hu, G.; Chen, J.; Qin, Y. Genome-Wide Characterization of R2R3-MYB Transcription Factors in Pitaya Reveals a R2R3-MYB Repressor HuMYB1 Involved in Fruit Ripening through Regulation of Betalain Biosynthesis by Repressing Betalain Biosynthesis-Related Genes. Cells. 2021, 10, 1949.

- Li, Y.; Liang, J.; Zeng, X.; Guo, H.; Luo, Y.; Kear, P.; Zhang, S.M.; Zhu, G. Genome-wide analysis of MYB gene family in potato provides insights into tissue-specific regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Horticultural Plant Journal. 2021, 7, 129-141.

- MULEKE, E. M. M.; Yan, W. A. N. G.; Zhang, W. T.; Liang, X. U.; Ying, J. L.; Karanja, B. K.; Zhu, X.W.; Fan, L.X.; Ahmadzai, Z.; Liu, L. W. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of MYB transcription factor genes in radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Journal of Integrative Agriculture. 2021, 20, 120-131.

- He, C.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A.; Wang, H.; Si, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Tan, J.; Duan, J. Mining MYB transcription factors from the genomes of orchids (Phalaenopsis and Dendrobium) and characterization of an orchid R2R3-MYB gene involved in water-soluble polysaccharide biosynthesis. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 13818.

- Bertioli, D.J.; Jenkins, J.; Clevenger, J.; Dudchenko, O.; Gao, D.; Seijo, G.; Leal-Bertioli, S.C.M.; Ren, L.; Farmer, A.D.; Pandey, M.K.; Samoluk, S.S.; Abernathy, B.; Agarwal, G.; Ballén-Taborda, C.; Cameron, C.; Campbell, J.; Chavarro, C.; Chitikineni, A.; Chu, Y.; Dash, S.; El Baidouri, M.; Guo, B.; Huang, W.; Kim, K.D.; Korani, W.; Lanciano, S.; Lui, C.G.; Mirouze, M.; Moretzsohn, M.C.; Pham, M.; Shin, J.H.; Shirasawa, K.; Sinharoy, S.; Sreedasyam, A.; Weeks, N.T.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, Z.; Froenicke, L.; Aiden, E.L.; Michelmore, R.; Varshney, R.K.; Holbrook, C.C.; Cannon, E.K.S.; Scheffler, B.E.; Grimwood, J.; Ozias-Akins, P.; Cannon, S.B.; Jackson, S.A.; Schmutz, J. The genome sequence of segmental allotetraploid peanut Arachis hypogaea. Nat Genet. 2019, 51, 877-884.

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Fang, Y.; Wang, B.; Xu, S.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor Family Revealed Their Potential Roles in the Flowering Process in Longan (Dimocarpus longan). Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 820439.

- Li, P.; Wen, J.; Chen, P.; Guo, P.; Ke, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; Tran, L.P.; Li, J.; Du, H. MYB Superfamily in Brassica napus: Evidence for Hormone-Mediated Expression Profiles, Large Expansion, and Functions in Root Hair Development. Biomolecules. 2020, 10, 875.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, C.; Wei, Y.; Meng, J.; Li, Z.; Zhong, C. Genome-wide analysis of MYB transcription factors and their responses to salt stress in Casuarina equisetifolia. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 328.

- Sabir, I.A.; Manzoor, M.A.; Shah, I.H.; Liu, X.; Zahid, M.S.; Jiu, S.; Wang, J.; Abdullah, M.; Zhang, C. MYB transcription factor family in sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.): genome-wide investigation, evolution, structure, characterization and expression patterns. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 2.

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021, 38, 3022-3027.

- Li, X.; Sathasivam, R.; Park, N. I.; Wu, Q.; Park, S. U. Enhancement of phenylpropanoid accumulation in tartary buckwheat hairy roots by overexpression of MYB transcription factors. Industrial Crops and Products. 2020, 156, 112887.

- He, J.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, D.; Duan, M.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Yang, C.; Qiu, Z.; Liu, D.; Wen, P.; Huang, J.; Fan, D.; Xiao, S.; Xin, Y.; Chen, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, H.; Yuan, L.; Wan, J. An R2R3 MYB transcription factor confers brown planthopper resistance by regulating the phenylalanine ammonia-lyase pathway in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020, 117, 271-277.

- Yang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yao, S.; Zhao, K.; Wang, D.; Qin, Q.; Bian, Z.; Li, Y.; Lan, Y.; Zhou, T.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Qi, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y. Jasmonate Signaling Enhances RNA Silencing and Antiviral Defense in Rice. Cell Host Microbe. 2020, 28, 89-103.

- Gao, J.; Chen, H.; Yang, H.; He, Y.; Tian, Z.; Li, J. A brassinosteroid responsive miRNA-target module regulates gibberellin biosynthesis and plant development. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 488-501.

- Li, G.; Zhao, J.; Qin, B.; Yin, Y.; An, W.; Mu, Z.; Cao, Y. ABA mediates development-dependent anthocyanin biosynthesis and fruit coloration in Lycium plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 317.

- Xie, Y.; Bao, C.; Chen, P.; Cao, F.; Liu, X.; Geng, D.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Hou, N.; Zhi, F.; Niu, C.; Zhou, S.; Zhan, X.; Ma, F.; Guan Q. Abscisic acid homeostasis is mediated by feedback regulation of MdMYB88 and MdMYB124. J Exp Bot. 2021, 72, 592-607.

- Yuan, Y.; Zeng, L.; Kong, D.; Mao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, C.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, D. Abscisic acid-induced transcription factor PsMYB306 negatively regulates tree peony bud dormancy release. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 2449-2471.

- Raza, A.; Salehi, H.; Rahman, M.A.; Zahid, Z.; Madadkar, H.M.; Najafi-Kakavand, S.; Charagh, S.; Osman, H.S.; Albaqami, M.; Zhuang, Y.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Zhuang, W. Plant hormones and neurotransmitter interactions mediate antioxidant defenses under induced oxidative stress in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 961872.

- Ruan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, M.; Yan, J.; Khurshid, M.; Weng, W.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, K. Jasmonic Acid Signaling Pathway in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 2479.

- Wasternack, C.; Song, S. Jasmonates: biosynthesis, metabolism, and signaling by proteins activating and repressing transcription. J Exp Bot. 2017, 68, 1303-1321.

- Li, C.; Yu, W.; Xu, J.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y. Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Induced by MYB Transcription Factors in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 11701.

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Ge, X.; Li, F.; Hou, Y. GhODO1, an R2R3-type MYB transcription factor, positively regulates cotton resistance to Verticillium dahliae via the lignin biosynthesis and jasmonic acid signaling pathway. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022, 201, 580-591.

- Nolan, T.M.; Vukašinović, N.; Hsu, C.W.; Zhang, J.; Vanhoutte, I.; Shahan, R.; Taylor, I.W.; Greenstreet, L.; Heitz, M.; Afanassiev, A.; Wang, P.; Szekely, P.; Brosnan, A.; Yin, Y.; Schiebinger, G.; Ohler, U.; Russinova, E.; Benfey, P.N. Brassinosteroid gene regulatory networks at cellular resolution in the Arabidopsis root. Science. 2023, 379, eadf4721.

- Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ge, X.; Lu, L.; Qin, W.; Qanmber, G.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, F. Brassinosteroids regulate cotton fiber elongation by modulating very-long-chain fatty acid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2023, 35, 2114-2131.

- Tian, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, F.; Qin, W.; Yang, H.; Zhao, S.; Xia, J.; Du, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, L.; Cao, Y.; Li, H.; Zhuang, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, M.; Deng, X.W.; Deng, D.; Li, J.; Tian, F. Maize smart-canopy architecture enhances yield at high densities. Nature. 2024, 632, 576-584.

- Li, L.; Yu, X.; Thompson, A.; Guo, M.; Yoshida, S.; Asami, T.; Chory, J.; Yin, Y. Arabidopsis MYB30 is a direct target of BES1 and cooperates with BES1 to regulate brassinosteroid-induced gene expression. Plant J. 2009, 58, 275-86.

- Chen, L.; Yang, H.; Fang, Y.; Guo, W.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Dai, W.; Chen, S.; Hao, Q.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Y.; Shan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Qiu, D.; Liu, X.; Tran, L.P.; Zhou, X.; Cao, D. Overexpression of GmMYB14 improves high-density yield and drought tolerance of soybean through regulating plant architecture mediated by the brassinosteroid pathway. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021, 19, 702-716.

- Janda, T.; Szalai, G.; Pál, M. Salicylic Acid Signalling in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Apr 10;21(7):2655.

- Frerigmann H.; Gigolashvili T. MYB34, MYB51, and MYB122 distinctly regulate indolic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant. 2014, 7, 814-28.

- Hu, Z.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, H.; Luo, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; An, H.; Xu, D.; Wan, P.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. GhMYB18 confers Aphis gossypii Glover resistance through regulating the synthesis of salicylic acid and flavonoids in cotton plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 355-369.

- Zhou, L.; Li, J.; Zeng, T.; Xu, Z.; Luo, J.; Zheng, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C. TcMYB8, a R3-MYB Transcription Factor, Positively Regulates Pyrethrin Biosynthesis in Tanacetum cinerariifolium. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 12186.

- Tolosa, L.N.; Zhang, Z. The Role of Major Transcription Factors in Solanaceous Food Crops under Different Stress Conditions: Current and Future Perspectives. Plants (Basel). 2020, 9, 56.

- Roy, S. Function of MYB domain transcription factors in abiotic stress and epigenetic control of stress response in plant genome. Plant Signal Behav. 2016, 11, e1117723.

- Li, J.; Han, G.; Sun, C.; Sui, N. Research advances of MYB transcription factors in plant stress resistance and breeding. Plant Signal Behav. 2019, 14, 1613131.

- Baillo, E.H.; Kimotho, R.N.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, P. Transcription Factors Associated with Abiotic and Biotic Stress Tolerance and Their Potential for Crops Improvement. Genes (Basel). 2019, 10, 771.

- Zhou, Z.; Wei, X.; Lan, H. CgMYB1, an R2R3-MYB transcription factor, can alleviate abiotic stress in an annual halophyte Chenopodium glaucum. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023, 196, 484-496.

- Bhat, Z.Y.; Mir, J.A.; Yadav, A.K.; Singh, D.; Ashraf, N. CstMYB1R1, a REVEILLE-8-like transcription factor, regulates diurnal clock-specific anthocyanin biosynthesis and response to abiotic stress in Crocus sativus L. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 43, 20.

- Du, B.; Liu, H.; Dong, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Over-Expression of an R2R3 MYB Gene, MdMYB108L, Enhances Tolerance to Salt Stress in Transgenic Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 9428.

- Ma, D.; Constabel, C.P. MYB Repressors as Regulators of Phenylpropanoid Metabolism in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 275-289.

- Zheng, T.; Tan, W.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, T.; Liu, B.; Zhang, D.; Lin, H. Regulation of anthocyanin accumulation via MYB75/HAT1/TPL-mediated transcriptional repression. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007993.

- Wang, Y.M.; Wang, C.; Guo, H.Y.; Wang, Y.C. BplMYB46 from Betula platyphylla Can Form Homodimers and Heterodimers and Is Involved in Salt and Osmotic Stresses. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 1171.

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhu, J.K. Abiotic stress responses in plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 104–119.

- Habibpourmehraban, F.; Wu, Y.; Masoomi-Aladizgeh, F.; Amirkhani, A.; Atwell, B.J.; Haynes, P.A. Pre-Treatment of Rice Plants with ABA Makes Them More Tolerant to Multiple Abiotic Stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 9628.

- Dubos, C.; Stracke, R.; Grotewold, E.; Weisshaar B.; Martin C.; Lepiniec L. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2010 Oct;15(10):573-81.

- Wu, X.; Xia, M.; Su, P.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, L.; Zhao, H.; Gao, W.; Huang, L.; Hu, Y. MYB transcription factors in plants: A comprehensive review of their discovery, structure, classification, functional diversity and regulatory mechanism. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024, 282, 136652.

- Baldoni, E.; Genga, A.; Cominelli, E. Plant MYB Transcription Factors: Their Role in Drought Response Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2015, 16, 15811-51.

- Colombage, R.; Singh, M.B.; Bhalla, P.L. Melatonin and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 7447.

- Huang, S.; Ma, Z.; Hu, L.; Huang, K.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, W.; Wu, T.; Du, X. Involvement of rice transcription factor OsERF19 in response to ABA and salt stress responses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 167, 22–30.

- Vadez, V.; Grondin, A.; Chenu, K.; Henry, A.; Laplaze, L.; Millet, E.J.; Carminati, A. Crop traits and production under drought. Nat Rev Earth Environ. 2024.

- Huang, K.; Wu, T.; Ma, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Bian, M.; Bai, H.; Jiang, W.; Du, X. Rice Transcription Factor OsWRKY55 Is Involved in the Drought Response and Regulation of Plant Growth. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 4337.

- Chieb, M.; Gachomo, E.W. The role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in plant drought stress responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 407.

- Zhang, G.; Li, G.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, A. The transcription factor ZmMYB-CC10 improves drought tolerance by activating ZmAPX4 expression in maize. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022, 604, 1-7.

- Lim, J.; Lim, C.W.; Lee, S.C. Role of pepper MYB transcription factor CaDIM1 in regulation of the drought response. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1028392.

- Peng, D.; Li, L.; Wei, A.; Zhou, L.; Wang, B.; Liu, M.; Lei, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, X. TaMYB44-5A reduces drought tolerance by repressing transcription of TaRD22-3A in the abscisic acid signaling pathway. Planta. 2024, 260, 52.

- Fang, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Tang, X.; Liu, C.; Yin, H.; Ye, S.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Luo, K. The poplar R2R3 MYB transcription factor PtrMYB94 coordinates with abscisic acid signaling to improve drought tolerance in plants. Tree Physiol. 2020, 40, 46-59.

- Zhou, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, F.; Lin, H.; Guo, Y. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J Genet Genomics. 2024, 51, 16-34.

- Zhou, Y.; Feng, C.; Wang, Y.; Yun, C.; Zou, X.; Cheng, N.; Zhang, W.; Jing, Y.; Li, H. Understanding of Plant Salt Tolerance Mechanisms and Application to Molecular Breeding. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 10940.

- Zhang, C.; Meng, Y.; Zhao, M.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Dong, J.; Fan, W.; Xu, F.; Wang, D.; Xie, Z. Advances and mechanisms of fungal symbionts in improving the salt tolerance of crops. Plant Sci. 2024, 349, 112261.

- Kausar, R.; Komatsu, S. Proteomic Approaches to Uncover Salt Stress Response Mechanisms in Crops. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 24, 518.

- Xiao, F.; Zhou, H. Plant salt response: Perception, signaling, and tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1053699.

- Park, S. J.; Jang, H. A.; Lee, H.; Choi, H. Functional Characterization of PagMYB148 in Salt Tolerance Response and Gene Expression Analysis under Abiotic Stress Conditions in Hybrid Poplar. Forests. 2024, 15, 1344.

- Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Hu, Y.; Liu, X.; Shareng, T.; Cao, G.; Xing, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, Z.; Bai, G.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Y. Transcriptome-Based Identification of the SaR2R3-MYB Gene Family in Sophora alopecuroides and Function Analysis of SaR2R3-MYB15 in Salt Stress Tolerance. Plants (Basel). 2024, 13, 586.

- Lu, M.; Chen, Z.; Dang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Zheng, H.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Du, X.; Sui, N. Identification of the MYB gene family in Sorghum bicolor and functional analysis of SbMYBAS1 in response to salt stress. Plant Mol Biol. 2023, 113, 249-264.

- Huang, J.; Zhao, X.; Bürger, M.; Chory, J.; Wang, X. The role of ethylene in plant temperature stress response. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 808-824.

- Wen, J.; Sui, S.; Tian, J.; Ji, Y.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, F.; Ottosen, C.O.; Zhong, Q.; Zhou, R. Moderately Elevated Temperature Offsets the Adverse Effects of Waterlogging Stress on Tomato. Plants (Basel). 2024, 13, 1924.

- Islam, W.; Adnan, M.; Alomran, M. M.; Qasim, M.; Waheed, A.; Alshaharni, M. O.; Zeng, F. Plant responses to temperature stress modulated by microRNAs. Physiologia Plantarum. 2024, 176, e14126.

- Zhou, C.; Wu, S.; Li, C.; Quan, W.; Wang, A. Response Mechanisms of Woody Plants to High-Temperature Stress. Plants (Basel). 2023, 12, 3643.

- Mariana, Distéfano A.; Bauer, V.; Cascallares, M.; López, G.A.; Fiol, D.F.; Zabaleta, E.; Pagnussat G.C. Heat stress in plants: sensing, signalling and ferroptosis. J Exp Bot. 2024, 11, erae296.

- Zhu, J.; Cao, X.; Deng, X. Epigenetic and transcription factors synergistically promote the high temperature response in plants. Trends Biochem Sci. 2023, 48, 788-800.

- Zhang, Y.S.; Xu, Y.; Xing, W.T.; Wu, B.; Huang, D.M.; Ma, F.N.; Zhan, R.L.; Sun, P.G.; Xu, Y.Y.; Song, S. Identification of the passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims) MYB family in fruit development and abiotic stress, and functional analysis of PeMYB87 in abiotic stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1124351.

- Li, Z.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, M.; Yao, Y.; Luo, H.; Wu, Q.; Wang, F.L.; Zhou, Y. Analysis of Transcriptional and Metabolic Differences in the Petal Color Change Response to High-Temperature Stress in Various Chrysanthemum Genotypes. Agronomy. 2024, 14, 2863.

- Xiao, L.; Cai, X.; Yu, R.; Nie, X.; Yang, K.; Wen, X. Functional analysis of HpMYB72 showed its positive involvement in high-temperature resistance via repressing the expression of HpCYP73A. Scientia Horticulturae. 2024, 338, 113741.

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, G.; Wang, X.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Huang, L.; Qin, P. Identifying Core Genes Related to Low-Temperature Stress Resistance in Quinoa Seedlings Based on WGCNA. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 6885.

- Jahed, K.R.; Saini, A.K.; Sherif, S.M. Coping with the cold: unveiling cryoprotectants, molecular signaling pathways, and strategies for cold stress resilience. Front Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1246093.

- Tiwari, M.; Kumar, R.; Subramanian, S.; Doherty, C.J.; Jagadish, S.V.K. Auxin-cytokinin interplay shapes root functionality under low-temperature stress. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 447-459.

- Xiao, J.; Li, Z.; Song, X.; Xie, M.; Tang, Y.; Lai, Y.; Sun, B.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Li, H. Functional characterization of CaSOC1 at low temperatures and its role in low-temperature escape. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024, 217, 109222.

- Li, W.; Li, P.; Chen, H.; Zhong, J.; Liang, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Han, D. Overexpression of a Fragaria vesca 1R-MYB Transcription Factor Gene (FvMYB114) Increases Salt and Cold Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 5261.

- Chen, B.C.; Wu, X.J.; Dong, Q.J.; Xiao, J.P. Screening and functional analysis of StMYB transcription factors in pigmented potato under low-temperature treatment. BMC Genomics. 2024, 25, 283.

- Chen, N.; Pan, L.; Yang, Z.; Su, M.; Xu, J.; Jiang, X.; Yin, X.; Wang, T.; Wan, F.; Chi, X. A MYB-related transcription factor from peanut, AhMYB30, improves freezing and salt stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis through both DREB/CBF and ABA-signaling pathways. Front Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1136626.

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, S.; Mohapatra, T. Interaction Between Macro- and Micro-Nutrients in Plants. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 665583.

- Antenozio, M.L.; Caissutti, C.; Caporusso, F.M.; Marzi, D.; Brunetti, P. Urban Air Pollution and Plant Tolerance: Omics Responses to Ozone, Nitrogen Oxides, and Particulate Matter. Plants (Basel). 2024, 13, 2027.

- Ge, L.; Dou, Y.; Li, M.; Qu, P.; He, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Ma, Y. SiMYB3 in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica) Confers Tolerance to Low-Nitrogen Stress by Regulating Root Growth in Transgenic Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 5741.

- Wang, W.; Fang, H.; Aslam, M.; Du, H.; Chen, J.; Luo, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, X. MYB gene family in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum revealing their potential functions in the adaption to nitrogen deficiency and diurnal cycle. J Phycol. 2022, 58, 121-132.

- Prathap, V.; Kumar, A.; Maheshwari, C.; Tyagi A. Phosphorus homeostasis: acquisition, sensing, and long-distance signaling in plants. Mol Biol Rep. 2022, 49, 8071-8086.

- Gu, M.; Chen, A.; Sun, S.; Xu, G. Complex Regulation of Plant Phosphate Transporters and the Gap between Molecular Mechanisms and Practical Application: What Is Missing? Mol Plant. 2016, 9, 396-416.

- Wang, Z.; Ruan, W.; Shi, J.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, D.; Yang, C.; Li, C.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Shou, H.; Mo, X.; Mao, C.; Wu, P. Rice SPX1 and SPX2 inhibit phosphate starvation responses through interacting with PHR2 in a phosphate-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014, 111, 14953-8.

- Wild, R.; Gerasimaite, R.; Jung, J.Y.; Truffault, V.; Pavlovic, I.; Schmidt, A.; Saiardi, A.; Jessen, H.J.; Poirier, Y.; Hothorn, M.; Mayer, A. Control of eukaryotic phosphate homeostasis by inositol polyphosphate sensor domains. Science. 2016, 352, 986-90.

- Dong, J.; Ma, G.; Sui, L.; Wei, M.; Satheesh, V.; Zhang, R.; Ge, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, T.E.; Wittwer, C.; Jessen, H.J.; Zhang, H.; An, G.Y.; Chao, D.Y.; Liu, D.; Lei, M. Inositol Pyrophosphate InsP8 Acts as an Intracellular Phosphate Signal in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2019, 12, 1463-1473.

- Ried, M.K.; Wild, R.; Zhu, J.; Pipercevic, J.; Sturm, K.; Broger, L.; Harmel, R.K.; Abriata, L.A.; Hothorn, L.A.; Fiedler, D.; Hiller, S.; Hothorn, M. Inositol pyrophosphates promote the interaction of SPX domains with the coiled-coil motif of PHR transcription factors to regulate plant phosphate homeostasis. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 384.

- Liu, T.Y.; Huang, T.K.; Tseng, C.Y.; Lai, Y.S.; Lin, S.I.; Lin, W.Y.; Chen, J.W.; Chiou, T.J. PHO2-dependent degradation of PHO1 modulates phosphate homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012, 24, 2168-83.

- Xiao, X.; Zhang, J.; Satheesh, V.; Meng, F.; Gao, W.; Dong, J.; Zheng, Z.; An, G.Y.; Nussaume, L.; Liu, D.; Lei, M. SHORT-ROOT stabilizes PHOSPHATE1 to regulate phosphate allocation in Arabidopsis. Nat Plants. 2022, 8, 1074-1081.

- Du, Q.; Wang, K.; Zou, C.; Xu, C.; Li, W.X. The PILNCR1-miR399 Regulatory Module Is Important for Low Phosphate Tolerance in Maize. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 1743-1753.

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Du, Q.; Wang, K.; Zou, C.; Li, W.X. The long non-coding RNA PILNCR2 increases low phosphate tolerance in maize by interfering with miRNA399-guided cleavage of ZmPHT1s. Mol Plant. 2023, 16, 1146-1159.

- Mulet, J.M.; Porcel, R.; Yenush, L. Modulation of potassium transport to increase abiotic stress tolerance in plants. J Exp Bot. 2023, 74, 5989-6005.

- Xiao, L.; Shi, Y.; Wang, R.; Feng, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Shi, X.; Jing, G.; Deng, P.; Song, T.; Jing, W.; Zhang, W. The transcription factor OsMYBc and an E3 ligase regulate expression of a K+ transporter during salt stress. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 843-859.

- Niu, M.; Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Song, J.; Cui, J.; Wang, L.; Su, N. Sugar Signals and R2R3-MYBs Participate in Potassium-Repressed Anthocyanin Accumulation in Radish. Plant Cell Physiol. 2023, 64, 1601-1616.

- Zhang, H.; Lu, L. Transcription factors involved in plant responses to cadmium-induced oxidative stress. Front Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1397289.

- Liu, C.; Wen, L.; Cui, Y.; Ahammed, G.J.; Cheng, Y. Metal transport proteins and transcription factor networks in plant responses to cadmium stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 218.

- Goncharuk, E.A.; Zagoskina, N.V. Heavy Metals, Their Phytotoxicity, and the Role of Phenolic Antioxidants in Plant Stress Responses with Focus on Cadmium: Review. Molecules. 2023, 28, 3921.

- Feng, Z.; Gao, B.; Qin, C.; Lian, B.; Wu, J.; Wang, J. Overexpression of PsMYB62 from Potentilla sericea confers cadmium tolerance in tobacco. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024, 216, 109146.

- Sun, M.; Qiao, H.X.; Yang, T.; Zhao, P.; Zhao, J.H.; Luo, J.M.; Liu, F.F.; Xiong, A.S. DcMYB62, a transcription factor from carrot, enhanced cadmium tolerance of Arabidopsis by inducing the accumulation of carotenoids and hydrogen sulfide. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024, 216, 109114.

- Li, X.; Lu, J.; Zhu, X.; Dong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chu, S.; Xiong, E.; Zheng, X.; Jiao, Y. AtMYBS1 negatively regulates heat tolerance by directly repressing the expression of MAX1 required for strigolactone biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100675.

- Wang, F.; Kong, W.; Wong, G.; Fu, L.; Peng, R.; Li, Z.; Yao, Q. AtMYB12 regulates flavonoids accumulation and abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Genet Genomics. 2016, 291, 1545-59.

- Beathard, C.; Mooney, S.; Al-Saharin, R.; Goyer, A.; Hellmann, H. Characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana R2R3 S23 MYB Transcription Factors as Novel Targets of the Ubiquitin Proteasome-Pathway and Regulators of Salt Stress and Abscisic Acid Response. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 629208.

- Li, Y.; Tian, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Sun, G.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, H. The Transcription Factor MYB37 Positively Regulates Photosynthetic Inhibition and Oxidative Damage in Arabidopsis Leaves Under Salt Stress. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 943153.

- Ortiz-García, P.; Pérez-Alonso, M.M.; González, O.V.A.; Sánchez-Parra, B.; Ludwig-Müller, J.; Wilkinson, M.D.; Pollmann, S. The Indole-3-Acetamide-Induced Arabidopsis Transcription Factor MYB74 Decreases Plant Growth and Contributes to the Control of Osmotic Stress Responses. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 928386.

- Lee, S.B.; Kim, H.U.; Suh, M.C. MYB94 and MYB96 Additively Activate Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 2300-2311.

- Yang, A.; Dai, X.; Zhang, W.H. A R2R3-type MYB gene, OsMYB2, is involved in salt, cold, and dehydration tolerance in rice. J Exp Bot. 2012, 63, 2541-56.

- Tang, Y.; Bao, X.; Zhi, Y.; Wu, Q.; Guo, Y.; Yin, X.; Zeng, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; He, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, Q.; Jia, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, K. Overexpression of a MYB Family Gene, OsMYB6, Increases Drought and Salinity Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Rice. Front Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 168.

- Chen, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, L.; Qi, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Du, H.; Tao, Z.; Zhao, T.; Deng, P.; Shu, Q.; Qian, Q.; Yu, H.; Song, S. Nuclear translocation of OsMFT1 that is impeded by OsFTIP1 promotes drought tolerance in rice. Mol Plant. 2021, 14, 1297-1311.

- Xiong, H.; Li, J.; Liu, P.; Duan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ali, J.; Li, Z. Overexpression of OsMYB48-1, a novel MYB-related transcription factor, enhances drought and salinity tolerance in rice. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e92913.

- Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Qi, H.; Guo, J.; Zhang, L.; Shen, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, F.; Xie, L.; Zhu, W.; Lü, P.; Qian, Q.; Yu, H.; Song, S. The OsFTIP6-OsHB22-OsMYBR57 module regulates drought response in rice. Mol Plant. 2022, 15, 1227-1242.

- Jian, L.; Kang, K.; Choi, Y.; Suh, M.C.; Paek, N.C. Mutation of OsMYB60 reduces rice resilience to drought stress by attenuating cuticular wax biosynthesis. Plant J. 2022, 112, 339-351.

- Zhu, N.; Cheng, S.; Liu, X.; Du, H.; Dai, M.; Zhou, D.X.; Yang, W.; Zhao, Y. The R2R3-type MYB gene OsMYB91 has a function in coordinating plant growth and salt stress tolerance in rice. Plant Sci. 2015, 236, 146-56.

- Su, C.F.; Wang, Y.C.; Hsieh, T.H.; Lu, C.A.; Tseng, TH.; Yu, S.M. A novel MYBS3-dependent pathway confers cold tolerance in rice. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 145-58.

- Dai, X.; Xu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Xu, W.; Wang, T.; Xue, Y.; Chong, K. Overexpression of an R1R2R3 MYB gene, OsMYB3R-2, increases tolerance to freezing, drought, and salt stress in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1739-51.

- Lv, Y.; Yang, M.; Hu, D.; Yang, Z.; Ma, S.; Li, X.; Xiong, L. The OsMYB30 Transcription Factor Suppresses Cold Tolerance by Interacting with a JAZ Protein and Suppressing β-Amylase Expression. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 1475-1491.

- El-Kereamy, A.; Bi, Y.M.; Ranathunge, K.; Beatty, P.H.; Good, A.G.; Rothstein, S.J. The rice R2R3-MYB transcription factor OsMYB55 is involved in the tolerance to high temperature and modulates amino acid metabolism. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e52030.

- Casaretto, J.A.; El-Kereamy, A.; Zeng, B.; Stiegelmeyer, S.M.; Chen, X.; Bi, Y.M.; Rothstein, S.J. Expression of OsMYB55 in maize activates stress-responsive genes and enhances heat and drought tolerance. BMC Genomics. 2016, 17, 312.

- Gao, L.J.; Liu, X.P.; Gao, K.K.; Cui, M.Q.; Zhu, H.H.; Li, G.X.; Yan, J.Y.; Wu, Y.R.; Ding, Z.J.; Chen, X.W.; Ma, J.F.; Harberd, N.P.; Zheng, S.J. ART1 and putrescine contribute to rice aluminum resistance via OsMYB30 in cell wall modification. J Integr Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 934-949.

- Wang, F.Z.; Chen, M.X.; Yu, L.J.; Xie, L.J.; Yuan, L.B.; Qi, H.; Xiao, M.; Guo, W.; Chen, Z.; Yi, K.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, R.; Shu, W.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Q.F. OsARM1, an R2R3 MYB Transcription Factor, Is Involved in Regulation of the Response to Arsenic Stress in Rice. Front Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1868.

- Ren, C.; Li, Z.; Song, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Han, D. Overexpression of a Grape MYB Transcription Factor Gene VhMYB2 Increases Salinity and Drought Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 10743.

- Fang, L.; Wang, Z.; Su, L.; Gong, L.; Xin, H. Vitis Myb14 confer cold and drought tolerance by activating lipid transfer protein genes expression and reactive oxygen species scavenge. Gene. 2024, 890, 147792.

- Wang, J.; Chen, C.; Wu, C.; Meng, Q.; Zhuang, K.; Ma, N. SlMYB41 positively regulates tomato thermotolerance by activating the expression of SlHSP90.3. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023, 204, 108106.

- Ning, C.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, X.; He, L.; Li, L.; Zong, D.; Chen, J. An R2R3 MYB transcription factor PsFLP regulates the symmetric division of guard mother cells during stomatal development in Pisum sativum. Physiol Plant. 2023, 175, e13943.

- Chen, X.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Ding, Q.; Shah, S.H.A.; Lin, W.; Li, Y.; Hou, X. BcMYB111 Responds to BcCBF2 and Induces Flavonol Biosynthesis to Enhance Tolerance under Cold Stress in Non-Heading Chinese Cabbage. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 8670.

- Liu, T.; Chen, T.; Kan, J.; Yao, Y.; Guo, D.; Yang, Y.; Ling, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B. The GhMYB36 transcription factor confers resistance to biotic and abiotic stress by enhancing PR1 gene expression in plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2022, 20, 722-735.

- Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Lei, J.; Chai, S.; Jin, X.; Zou, Y.; Sun, X.; Mei, Y.; Cheng, X.; Yang, X.; Jiao, C.; Tian, X. IbMYB308, a Sweet Potato R2R3-MYB Gene, Improves Salt Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Tobacco. Genes (Basel). 2022, 13, 1476.

| Gene name | Species | R2R3-MYB number | MYB-related number |

R1R2R3-MYB and Atypical MYB number |

Total number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AtMYBs | Arabidopsis thaliana | 126 | 64 | 8 | 198 | [22] |

| OsMYBs | Oryza sativa | 148 | 87 | 4 | 239 | [15,23] |

| GmMYBs | Glycine max | 244 | 0 | 10 | 254 | [24] |

| BvMYBs | Beta vulgaris | 70 | 0 | 5 | 75 | [25] |

| SlMYBs | Solanum lycopersicum | 122 | 0 | 5 | 127 | [26] |

| PhMYBs | Petunia hybrida | 106 | 40 | 9 | 155 | [27] |

| AcMYBs | Actinidia chinensis | 91 | 87 | 3 | 181 | [28] |

| CaMYBs | Capsicum annuum | 116 | 92 | 7 | 215 | [29] |

| MaMYBs | Musa acuminata | 222 | 73 | 10 | 305 | [30] |

| MbMYBs | Musa balbisiana | 184 | 59 | 8 | 251 | [30] |

| HuMYBs | Hylocereus undatus | 105 | 75 | 5 | 185 | [31] |

| StMYBs | Solanum tuberosum | 124 | 90 | 3 | 217 | [32] |

| RsMYBs | Raphanus sativus | 174 | 2 | 11 | 187 | [33] |

| DoMYBs | Dendrobium officinale | 117 | 42 | 5 | 164 | [34] |

| AhMYBs | Arachis hypogaea | 209 | 219 | 15 | 443 | [35] |

| DlMYBs | Dimocarpus longan | 119 | 95 | 5 | 219 | [36] |

| BnMYBs | Brassica napus | 429 | 227 | 24 | 680 | [37] |

| CeMYBs | Casuarina equisetifolia | 107 | 69 | 6 | 182 | [38] |

| PaMYBs | Prunus avium | 14 | 51 | 4 | 69 | [39] |

| Abiotic Stress Type | MYB transcription factors | Species | Target genes and sites | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High temperature | AtMYBS1 | Arabidopsis thaliana L. | MAX1 | [132] |

| High temperature, salt, drought | AtMYB12 | Arabidopsis thaliana L. |

ZEP, NCED, ABA2, AAO, P5CS, P5CR, LEA, SOD, CAT, POD and Flavonoid biosynthesis genes |

[133] |

| Salt | AtMYB25 | Arabidopsis thaliana L. | DREB2C, RD29a, SLAH1, JAZ10 | [134] |

| Salt, drought | AtMYB37 | Arabidopsis thaliana L. |

ABF2/3, COR15A, RD29a, RD22, PSII/I |

[135] |

| High temperature | AtMYB74 | Arabidopsis thaliana L. |

ERF53, NIG1, HSFA6a, MYB47, MYB90, MYB102 |

[136] |

| Drought | AtMYB94/96 | Arabidopsis thaliana L. | KCS1/2/6, KCR1, CER1/3, WSD1 | [137] |

| Salt, drought, cold | OsMYB2 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | OsLEA3,OsRab16A,OsDREB2A | [138] |

| Salt, drought | OsMYB6 | Rice (Oryza sativa) |

OsLEA3,OsDREB2A,OsDREB1A,OsP5CS, SNAC1,OsCATA |

[139] |

| Drought | OsMYB26 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | OsLEA3 | [140] |

| Drought | OsMYB48-1 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | OsNCED4,OsNCED5 | [141] |

| Drought | OsMYBR57 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | OsLEA3,Rab21 | [142] |

| Drought | OsMYB60 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | OsCER1 | [143] |

| Salt | OsMYB91 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | SLR1 | [144] |

| Cold | OsMYBS3 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | DREB1 | [145] |

| Cold | OsMYB3R-2 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | DREB2A,COR15a,RCI2A | [146] |

| Cold | OsMYB30 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | OsAGPL3,OsSSIIIb,OsSSIIb,OsSSIIc | [147] |

| High temperature | OsMYB55 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | OsGS1,GAT1,GAD3 | [148,149] |

| Heavy metal stress | OsMYB30 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | Os4CL5 | [150] |

| Heavy metal stress | OsARM1 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | OsLsi1,OsLsi2,OsLsi6 | [151] |

| Salt, drought | VhMYB2 |

V. labrusca×V. riparia |

SOS1/2/3, NHX1, SnRK2.6, NCED3, P5CS1, CAT1 |

[152] |

| Salt, drought, cold | VaMYB14 | Vitis amurensis | ABA signaling genes, CORs, LTPs, CAT, POD |

[153] |

| High temperature | SlMYB41 |

Solanum lycopersicum |

SlHSP90.3 | [154] |

| Drought | PsFLP | Pisum sativum |

CYCA2;3, CDKA;1, AAO3, NCED3, SnRK2.3 |

[155] |

| Cold | BcMYB111 | Brassica campestris | F3H, FLS1 | [156] |

| Drought | GhMYB36 | Gossypium hirsutum | PR1 | [157] |

| Salt | IbMYB308 | Ipomoea batatas | SOD, POD, APX, P5CS | [158] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).