1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Sanitary Facility Planning Challenges

Sanitary facilities are more than an afterthought in building design; they significantly affect occupant comfort, health, and resource use [

1]. Historically, building codes—like New Zealand’s Building Code (Clause G1 Personal Hygiene) [

2], the United Kingdom’s Building Regulations – Approved Document G [

3], and the International Plumbing Code in the United States [

4]—have guided fixture requirements. However, these guidelines often rely on static assumptions that fail to capture flexible work arrangements or varying daily usage. Thus, many facilities end up overbuilt or underprepared for peak demands.

Traditional approaches based on queueing theory [

5,

6] further illustrate the complexity. While mathematically sound, they tend to overlook the wide range of human behaviors involved in restrooms. This highlights the need for new approaches that adapt to modern building use, evolving demographics, and shifting occupancy patterns.

1.2. Context of the Singapore Office Building Study

In Singapore, a regulatory void for office-specific sanitary facility standards has led to reliance on either broad international codes or personal heuristics. Under the National Environment Agency’s (NEA) Code of Practice for Environmental Health 2024 [

7], no direct guidance exists for offices, prompting designers to borrow from external sources that may not reflect Singapore’s local norms. The Singtel Serangoon TEPL office building project in Singapore addressed this gap by examining cultural practices, workplace habits, and actual occupancy trends to form more precise, context-driven guidelines.

This research combined international codes, queueing theory, and region-specific insights. By probing cultural norms and dynamic occupancy, it became clear that existing rules and models sometimes fall short when applied to a local setting. These observations drove the need for more sophisticated methods, specifically LSTM neural networks, to generate better-informed recommendations.

1.3. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Facility Planning

Recent years have seen AI revolutionize problem-solving in facility management. Unlike rigid models, machine learning (ML) algorithms embrace nonlinear interactions and can adjust to new data streams. LSTM neural networks [

8,

9], designed for sequential inputs, show particular promise when forecasting restroom usage patterns, given their ability to handle time-dependent data and unpredictable behaviors.

1.4. Objectives and Contributions of the Study

This research develops and tests an AI-based framework to optimize sanitary fixture requirements in office buildings in Singapore. Drawing on data from the Singtel Serangoon TEPL building at 1 Serangoon North Avenue 5, Singapore, it aims to:

Build a predictive model that accounts for time-based, demographic, and environmental factors

Compare AI-based forecasts against traditional methods

Pinpoint critical factors shaping restroom usage

Illustrate practical benefits of the model in a working environment

Through these aims, the study expands machine learning’s utility in facility management and offers valuable guidance for designers, engineers, and stakeholders.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Prescriptive Codes – Comparative Analysis of International Toilet Standards

Prescriptive codes have long provided the backbone for establishing fixture counts across multiple regions. Frameworks like the International Plumbing Code [

4], the UK’s Approved Document G [

3], and Australia’s National Construction Code [

10] typically define basic compliance requirements. While straightforward, these standards can differ substantially, reflecting each location’s cultural norms and regulatory outlook.

However, international standards diverge significantly due to cultural practices, regulatory priorities, and design philosophies. Greed [

1] shed light on disparities in Western regulations, especially regarding gender equity and accessibility. The UK’s Approved Document G [

2] strives to address these issues, while Australia’s NCC [

10] offers a more performance-based angle, contrasting with the IPC’s [

4] focus on rigid guidelines. Despite their utility, prescriptive rules:

- -

Rely on static models that may miss flexible work hours or variable occupancy [

11]

- -

Struggle with unique cultural practices or peak events [

1]

- -

Risk over- or under-providing, leading to cost burdens or user frustration [

12]

- -

Often refer to outdated assumptions, overlooking workplace shifts like remote work or evolving gender norms [

13]

Studies such as those by Ching and Winkel [

11] reinforce the call for flexible, data-powered frameworks in response to global variations and changing usage patterns.

2.2. Queueing Theory Models for Toilet Facilities

Queueing theory has a long history in analyzing restroom capacity. Early M/M/c formulations by Haight [

14] shaped the basic concept of arrival rates and service times, while Davidson and Courtney [

13] introduced M/G/c approaches to capture more realistic patterns. Subsequent improvements integrated:

- -

Gender-based factors (Kira [

15])

- -

Time-sensitive variables (Rothausen-Vange et al. [

12])

However, these models tend to oversimplify arrival rates, ignore cultural or behavioral nuances, and need constant parameter fine-tuning [

11,

13,

16]. Such constraints highlight the necessity for more adaptive strategies—ones that machine learning can support.

2.3. Applications of Machine Learning in Facilities Management

Machine learning, though underexplored in sanitary facility planning, has already shown promise in building management at large:

- -

Energy Forecasting: Neural networks surpass traditional statistics in capturing non-linear links among energy usage, weather, and occupancy [

17,

18].

- -

Occupancy Prediction: Techniques like decision trees and random forests help infer real-time occupant counts, guiding resource distribution [

18,

19].

- -

Restroom Optimization: Lokman et al. [

20] used sensor data to optimize cleaning schedules, hinting at wider possibilities for fixture planning.

- -

Deep Learning: LSTM architectures thrive in high-dimensional, rapidly changing systems akin to restroom demand [

18,

21].

Such methods excel at handling diverse inputs, scaling well, and uncovering usage patterns that simpler models miss. Nonetheless, broader data gathering and proper validation remain crucial to confirm their reliability in restroom planning.

2.4. Gaps in Current Approaches

Despite progress in queueing theory and ML-based solutions, notable gaps persist:

- -

Real-world user experiences frequently diverge from purely theoretical models [

6].

- -

Traditional queueing approaches often stumble in dynamic, time-sensitive settings [

6].

- -

Machine learning’s potential in capturing complex user behaviors is largely unfulfilled, with few targeted studies [

6,

16,

22].

- -

Building-focused data sets are still limited, highlighting the importance of innovative collection efforts [

6,

23].

The present work merges the strengths of queueing theory, prescriptive guidelines, and cutting-edge machine learning to propose a more adaptive and context-aware pathway for sanitary facility planning.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview of Proposed Machine Learning Approach

This study adopts a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network, a special class of recurrent neural network (RNN) designed to handle time-series data by capturing both near-term and long-term dependencies. Such adaptability is crucial for modeling dynamic restroom usage, where facility demand can shift throughout the day.

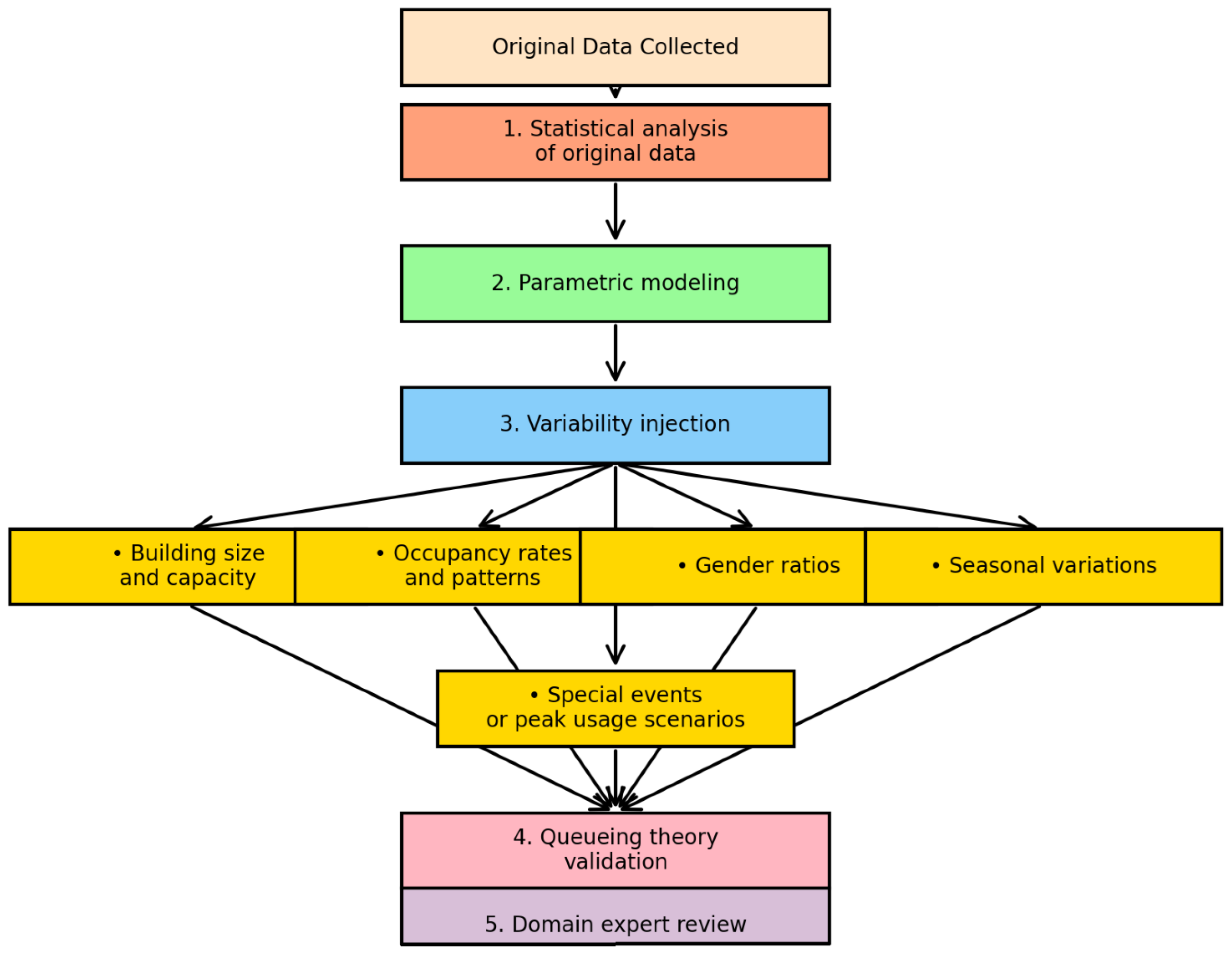

The methodological workflow encompasses five primary stages:

Data Collection and Preprocessing – Compiling both empirical and synthetic datasets to reflect a range of usage scenarios.

Feature Engineering – Identifying and extracting key variables, including occupancy levels, gender distribution, and temporal factors.

Model Development and Training – Designing and refining the LSTM architecture using the preprocessed dataset.

Hyperparameter Tuning – Systematically optimizing the model configuration to elevate predictive accuracy.

Performance Evaluation – Measuring the final model’s performance against standard methods like queueing theory.

The model’s input features capture occupancy, time of day, and gender proportions, while its output focuses on estimating the required counts of toilets, urinals, and washbasins for each gender.

3.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

3.2.1. Original Data from Singtel Report

A significant portion of the dataset originates from the Singtel Serangoon TEPL office building. These data points include:

- -

Occupancy Records: Verified occupant counts (male and female) spanning Floors 2–6, enabling thorough gender-based analysis.

- -

Facility Inventories: Comprehensive listings of toilets (WCs), urinals (URs), wash hand basins (WHBs), and showers, captured across floors.

- -

Floor Plans: Architectural blueprints to factor in spatial layout, accessibility, and fixture distribution.

- -

Usage Assumptions: Behavioral metrics derived from the World Toilet Organization, such as average toilet visits (four per occupant per day) and service durations (3 minutes per visit for females, 1.5 minutes for males).

- -

International Benchmarks: Baseline comparisons grounded in sanitary provisions outlined by the UK, Australia, and the United States.

To examine how the proposed model handles different levels of demand, a set of extended scenarios was introduced:

- -

Population Increases – Occupant surges of 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%, representing various high-demand situations.

- -

Reduced Utilization – Occupancy dropping to 85% of the baseline, simulating lower-demand environments.

By combining real observational data with hypothetical scenarios, the study ensures that the model has exposure to a wider range of usage profiles, thus improving its robustness.

3.2.2. Scenario Variations

In order to test how resilient the model is under changing conditions, the dataset includes modifications related to occupancy and usage behavior:

- -

Population Increases: Gradual escalations of 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% to mirror busier periods.

- -

Reduced Utilization: Scaling back to 85% occupancy to capture off-peak conditions.

These artificial expansions allow the model to forecast facility requirements even in unusual or extreme scenarios, broadening its applicability.

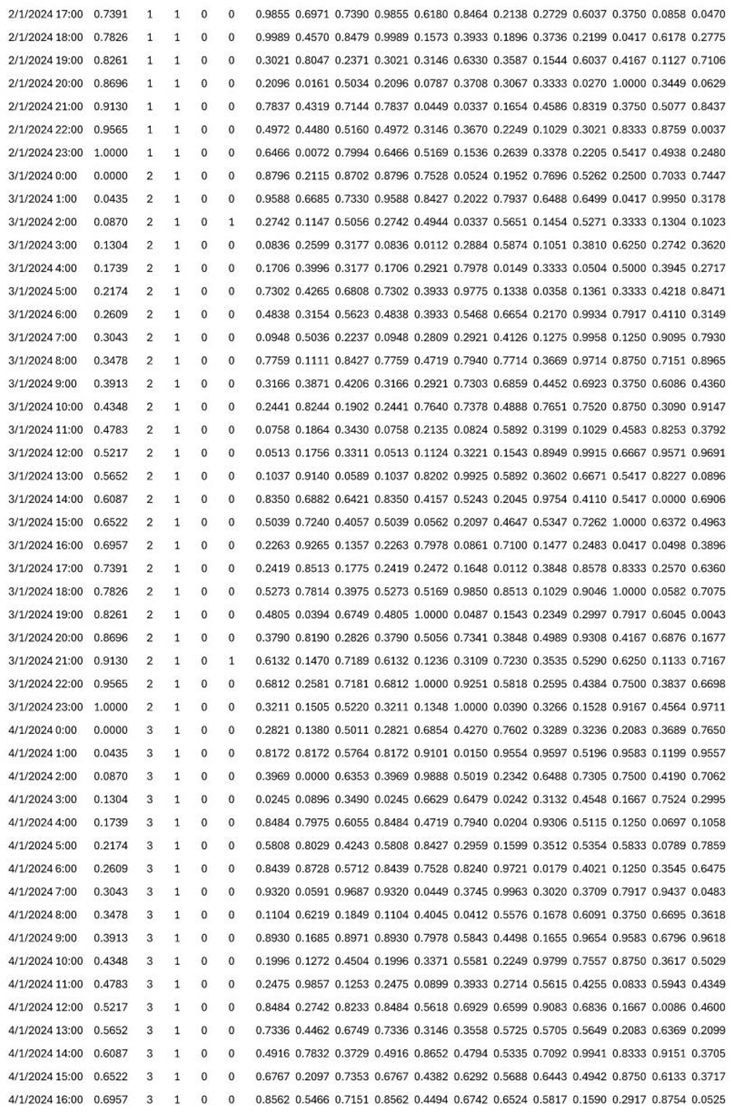

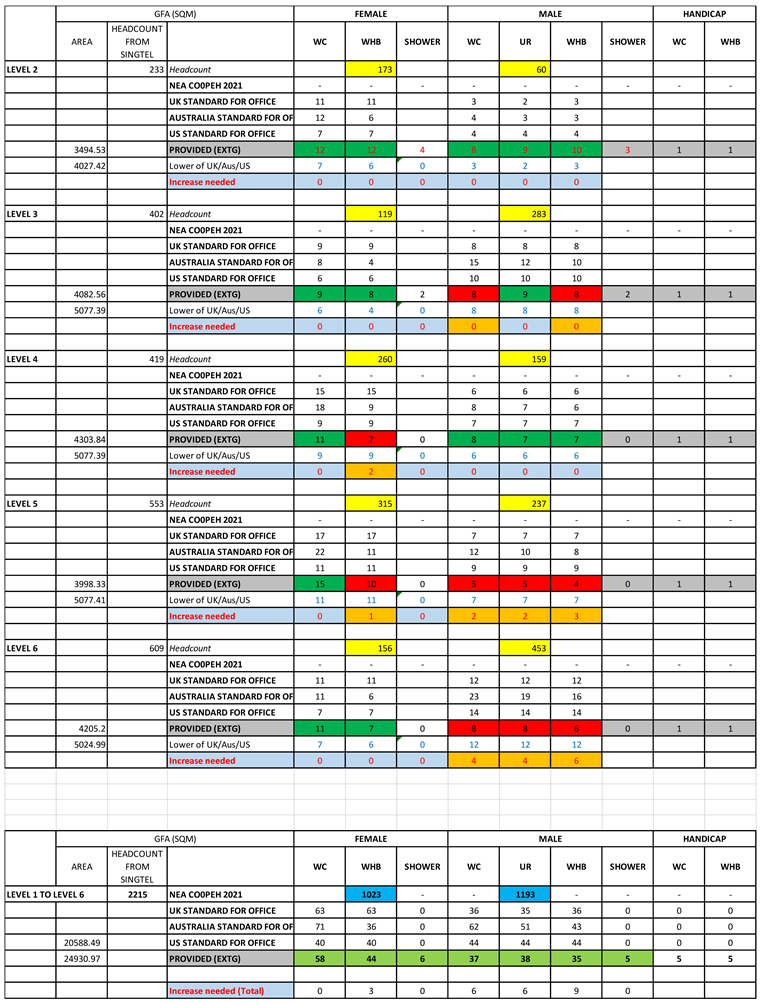

3.2.3. Summary of Current Facilities

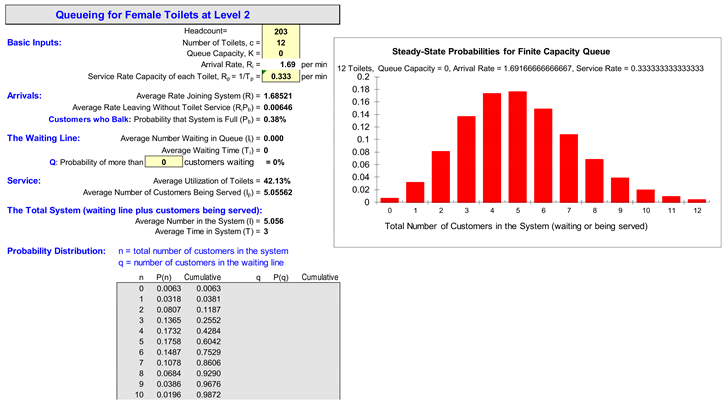

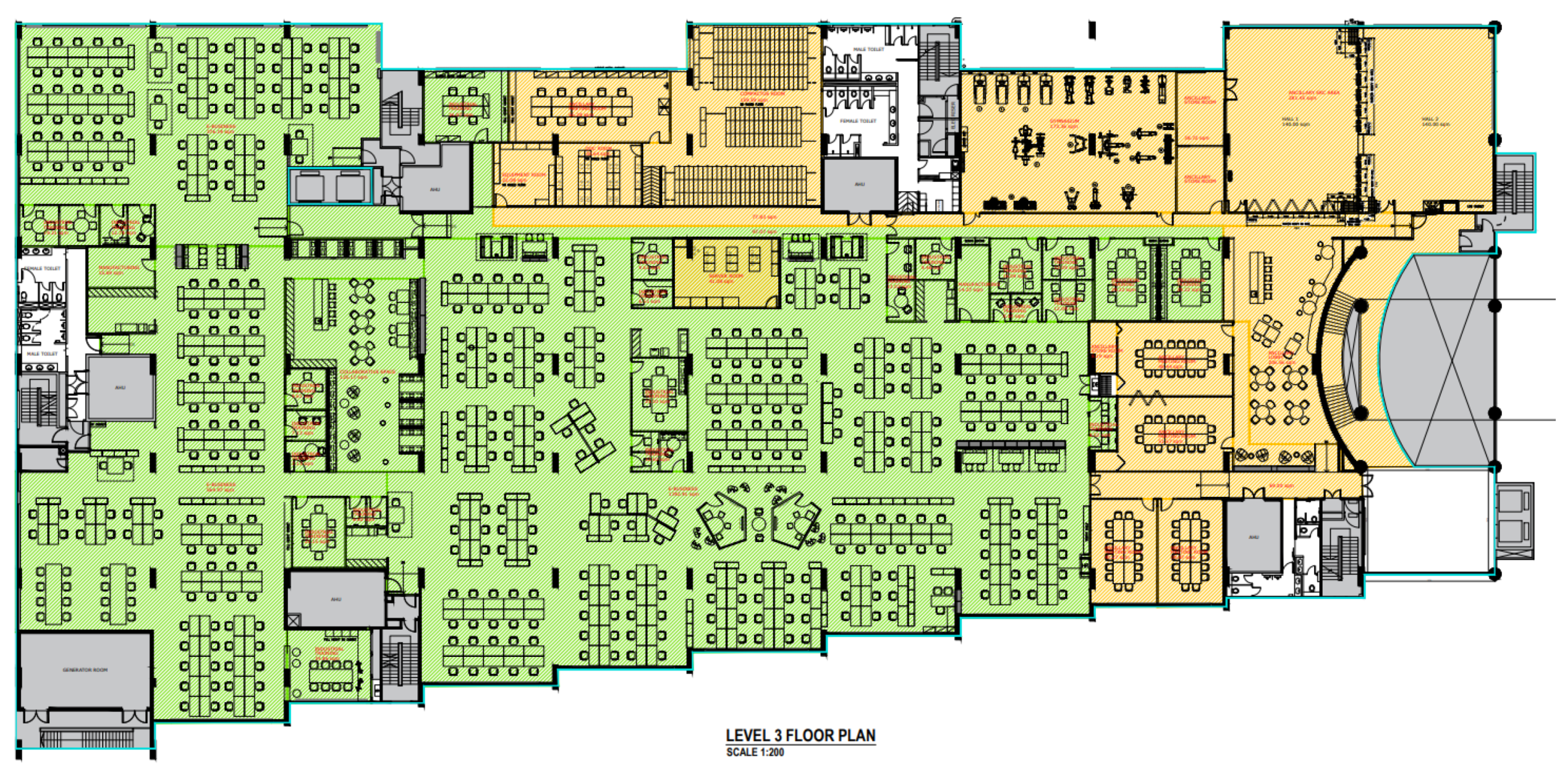

Table 1 provides an overview of how many fixtures are currently allocated for each gender on Floors 2 through 6, shedding light on possible imbalances in fixture distribution. Meanwhile,

Figure 1 illustrates a typical floor layout (Level 3) from the Singtel building, giving insight into restroom locations and accessibility.

3.2.4. Data Enhancement and Scenario Testing

To bolster the dataset and ensure it represents a wide range of daily operations, further variations were introduced:

- 1.

Scenario Variability

- -

Occupancy Adjustments: Incremental increases of 10%–40% and a cutback to 85% baseline to emulate extremes of usage

- -

Demographic Ratios: Shifts in the male-to-female ratio to gauge differential fixture requirements

- -

Temporal Patterns: Inclusion of seasonal and time-of-day fluctuations

- -

Event-Based Surges: Additional bursts in occupancy during conferences, meetings, or other peak activity windows

- 2.

Validation with Queueing Models

- -

M/M/c and M/G/c queueing frameworks were applied to confirm that the synthetic data mirrored realistic operational patterns in queue lengths and waiting times.

- 3.

Expert Review

- -

Facility management practitioners reviewed these extended scenarios to validate that the adjustments stayed true to real-life building dynamics.

Figure 2 illustrates the overall workflow for scenario generation and testing. This structured approach ensures the model’s training extends beyond a single building context, making it more flexible for varied real-world conditions.

3.3. Feature Selection and Engineering

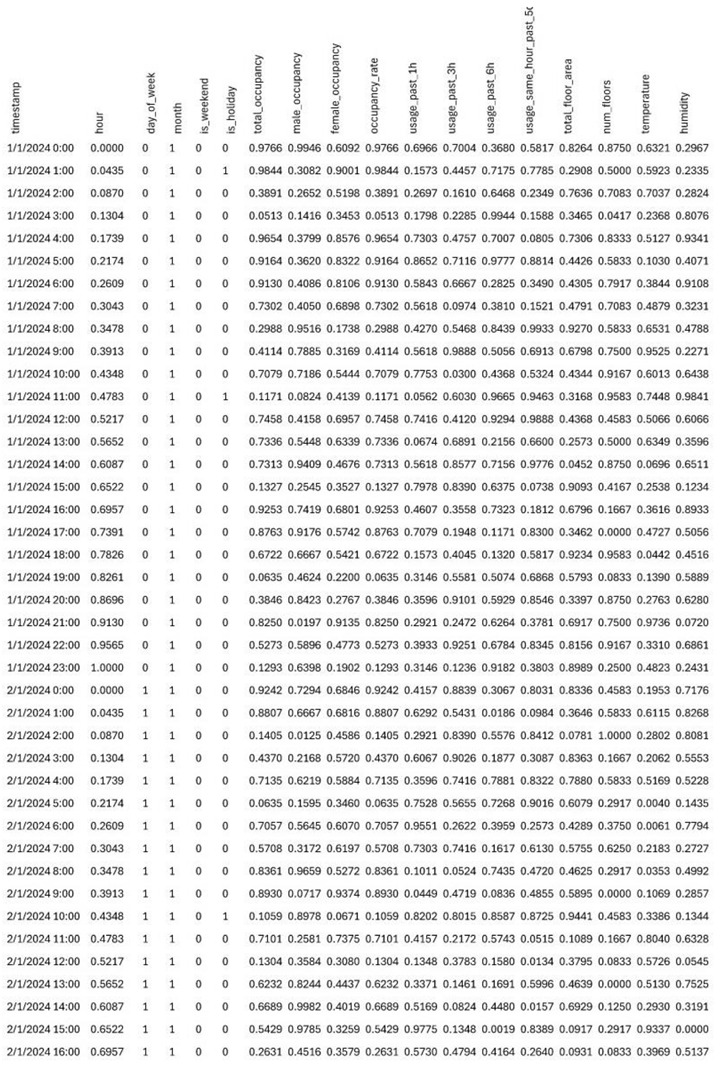

A critical factor in any robust machine learning application is converting raw data into informative features. Based on domain knowledge and dataset specifics, key features included:

- -

Temporal Features: Hourly/daily indicators and seasonal markers, with flags for weekends and holidays

- -

Occupancy Features: Total occupant count, gender ratio, and occupancy change rate

- -

Environmental Features: Weather metrics (temperature and humidity) to control for external factors

- -

Building Characteristics: Floor area, layout constraints, and total floors

- -

Event Features: Indicators for specific events, coupled with estimates of attendee numbers

To avoid redundant or noisy inputs, feature importance was assessed using tree-based methods, and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied where necessary. Numerical variables were normalized to a 0–1 scale, while categorical features underwent one-hot encoding for consistency across the neural network input layers.

3.4. Machine Learning Model Development

3.4.1. Model Architecture

The proposed model integrates LSTM layers (for capturing temporal trends) with dense (fully connected) layers (for interpreting non-sequential features). It can be broken down as follows:

- 1.

Input Layer

- -

- 2.

LSTM Layers

- -

Two stacked LSTM layers with 128 and 64 units, respectively, designed to identify both short-term fluctuations and longer-term usage cycles.

- 3.

Dense Layers

- -

Two fully connected layers with 64 and 32 units, each leveraging ReLU activa tion. The outputs from the LSTM stack are combined with non-time-based features, providing a holistic view of restroom demand.

- 4.

Output Layer

- -

A final dense layer featuring six units—predicting the number of toilets, urinals, and washbasins needed for both female and male occupants—using a linear activation function.

To control overfitting, dropout layers (rate: 0.2) were inserted after each LSTM and dense layer.

Figure 3 outlines the model flow, while

Figure 4 presents a more detailed schematic of the neural architecture.

3.4.2. Training Process

The model was trained using the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate of 0.001), with Mean Squared Error (MSE) chosen as the loss function:

where

denotes the true value and

the predicted value. The core steps of the training procedure are outlined below:

- 1.

Data Partitioning

- -

70% of the data was assigned for training, 15% for validation, and the final 15% for testing.

- 2.

Batch Training

- -

Mini-batches of size 64 were employed for 100 epochs, facilitating steady gradient updates and helping to deter overfitting.

- 3.

Early Stopping

- -

Training was halted once validation loss failed to improve for 10 consecutive epochs, a safeguard against excessive overfitting.

- 4.

Adaptive Learning Rate

- -

The learning rate was halved whenever the validation loss showed no progress for 5 straight epochs, helping stabilize training.

Figure 5 plots both training and validation loss over 100 epochs. Initially, both losses decrease rapidly, reflecting significant learning in the early stages. The training loss stabilizes at 0.031, while the validation loss ends at 0.160, showing some fluctuation indicative of partial overfitting.

The convergence point around epoch 50 (marked by the green dashed line) indicates diminishing returns from further training, as validation loss becomes more volatile while training loss continues to decline. This suggests overfitting, highlighting the need for techniques such as increased regularization or additional hyperparameter tuning to enhance generalization.

3.4.3. Hyperparameter Tuning

To refine the model’s performance, Bayesian optimization was carried out using the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) in the Hyperopt library [

24]. Key parameters examined included:

- -

Number of LSTM Layers (ranging from 1–3)

- -

Units in Each Layer (32–256)

- -

Number of Dense Layers (1–3)

- -

Dropout Rates (0.1–0.5)

- -

Learning Rates (0.0001–0.01)

- -

Batch Sizes (32–128)

Over 100 optimization trials, the best configuration surfaced with two LSTM layers of 128 and 64 units, two dense layers (64 and 32 units, respectively), a dropout rate of 0.2, and a batch size of 64.

Figure 6 shows a parallel coordinates plot highlighting the interdependencies among hyperparameters, along with an optimization curve converging near trial 40.

3.5. Performance Evaluation Metrics

Several metrics were used to thoroughly assess model performance and compare it with queueing-based models (M/M/c) as well as standards from international building codes:

- 1.

Mean Squared Error (MSE)

- -

Evaluates the average of squared deviations between predictions and actual values.

where

denotes the true value and

the predicted value.

- 2.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

- -

The square root of MSE, offering a direct measure of prediction accuracy in original units.

where RMSE is simply the square root of the MSE, providing a direct measure of prediction accuracy.

- 3.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

- -

The average of absolute differences between predictions and observations.

- 4.

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE)

- -

Reflects relative accuracy by expressing errors as a percentage of observed values.

- 5.

R-squared (R²)

- -

Indicates how much variance in the target variable is explained by the model.

- 6.

Queue Length Accuracy (QLA)

- -

Compares predicted queue lengths (Q_pred) with actual queue lengths (Q_actual).

- 7.

Waiting Time Accuracy (WTA)

- -

Measures the precision of predicted waiting times (W_pred vs. W_actual).

Where Wpred is the predicted waiting time and Wactual is the actual waiting time.

- 8.

Fixture Utilization Accuracy (FUA)

- -

Compares predicted fixture utilization rates (U_pred) to actual rates (U_actual).

Where Upred is the predicted fixture utilization rate and Uactual is the actual utilization rate. This metric assesses how well our model predicts the utilization of sanitary fixtures.

- 9.

Peak Demand Accuracy (PDA)

- -

Assesses the model’s ability to anticipate the highest usage periods accurately.

Where Ppred is the predicted peak demand and Pactual is the actual peak demand.

- 10.

Gender-Specific Accuracy (GSA)

- -

Evaluates how closely predicted fixture counts for each gender match reality (F_pred_gender vs. F_actual_gender).

Where Fpred_gender and Factual_gender are the predicted and actual number of fixtures for a specific gender, and m is the number of fixture types.

These metrics were calculated for both validation and test datasets. Paired t-tests were used to verify significant differences between the LSTM-based approach, queueing theory, and standards-based methods. A follow-up sensitivity analysis isolated changes in key inputs (e.g., gender ratio, occupancy rate) to gauge their impact on predictions.

Finally, the model’s external validity was tested by applying it to fresh data from the Singtel Serangoon TEPL building that were not included in the training phase. This step helps confirm the generalizability of the approach, ensuring it can adapt to realistic operational contexts.

By evaluating these metrics and validating results against multiple scenarios, the study offers a comprehensive view of the model’s performance relative to traditional approaches, highlighting its strengths and outlining areas that could still be enhanced.

4. Results

4.1. Model Performance Analysis

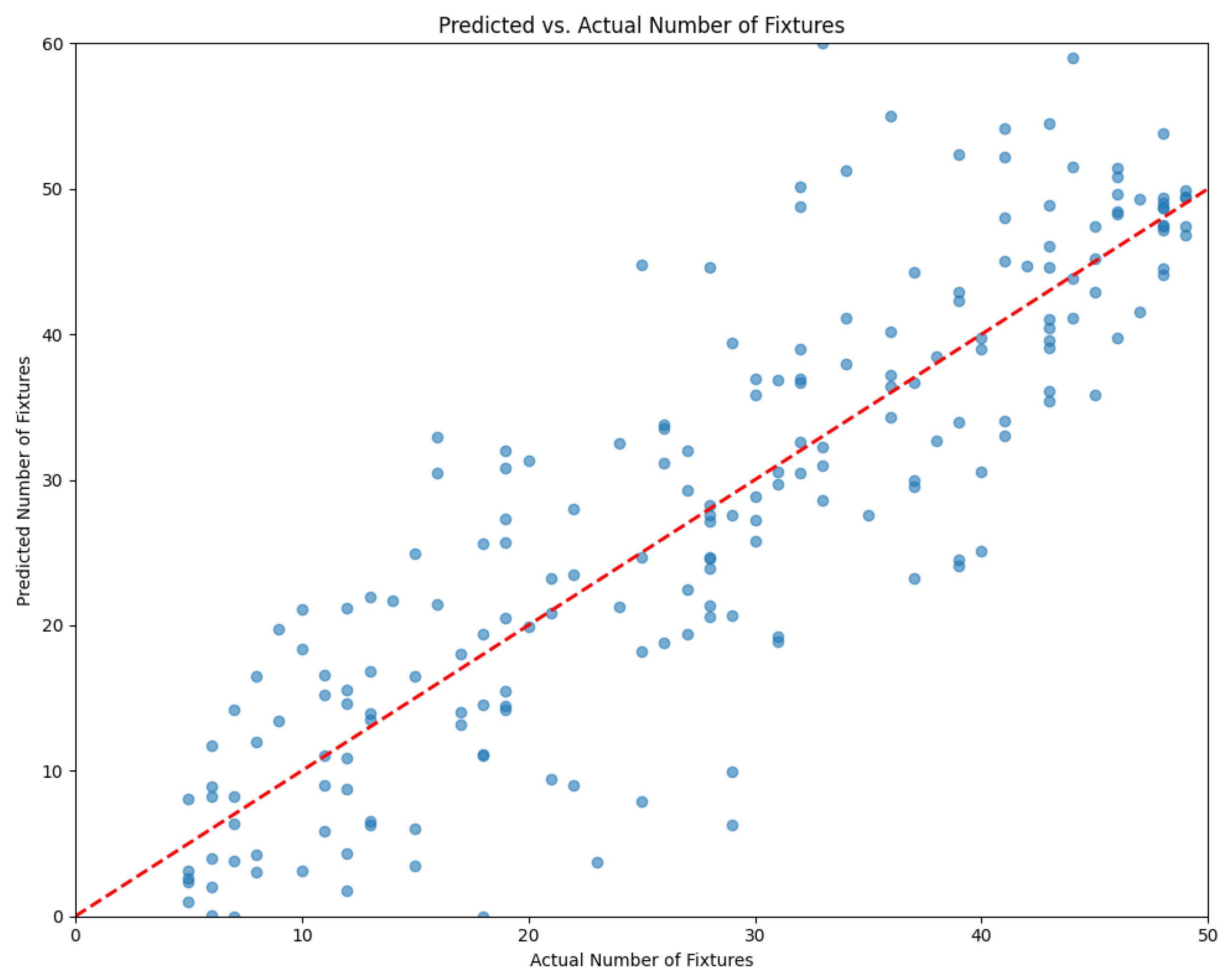

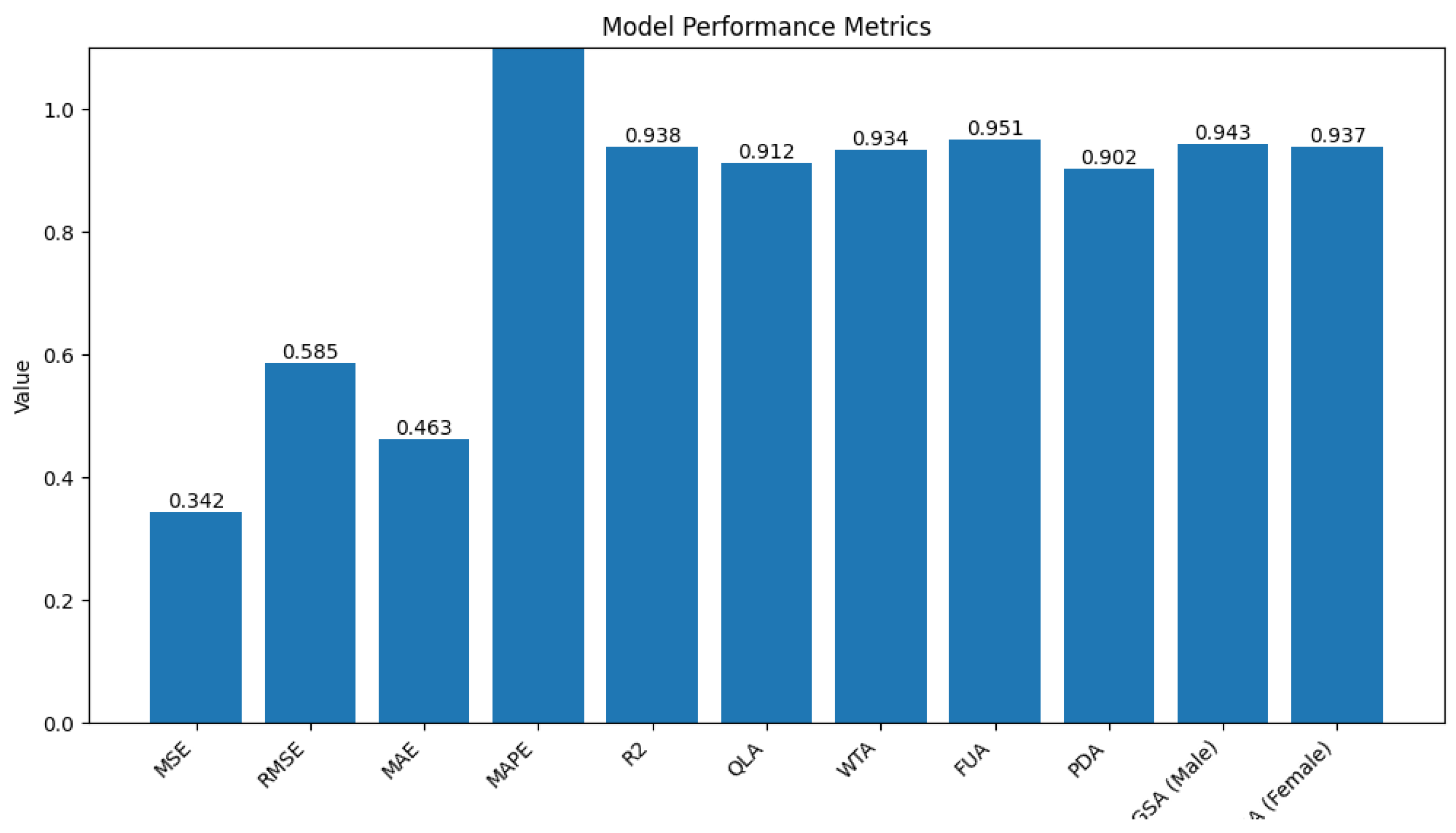

The deep learning model showed strong predictive accuracy on the test dataset, effectively estimating sanitary fixture needs under varying conditions.

Table 2 presents the primary performance metrics:

A Mean Squared Error (MSE) of 0.342 and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) of 0.585 indicate that deviations between predictions and actual usage typically hover below one fixture unit. Meanwhile, the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of 7.21% suggests that predictions differ from ground truth by roughly 7–8% on average.

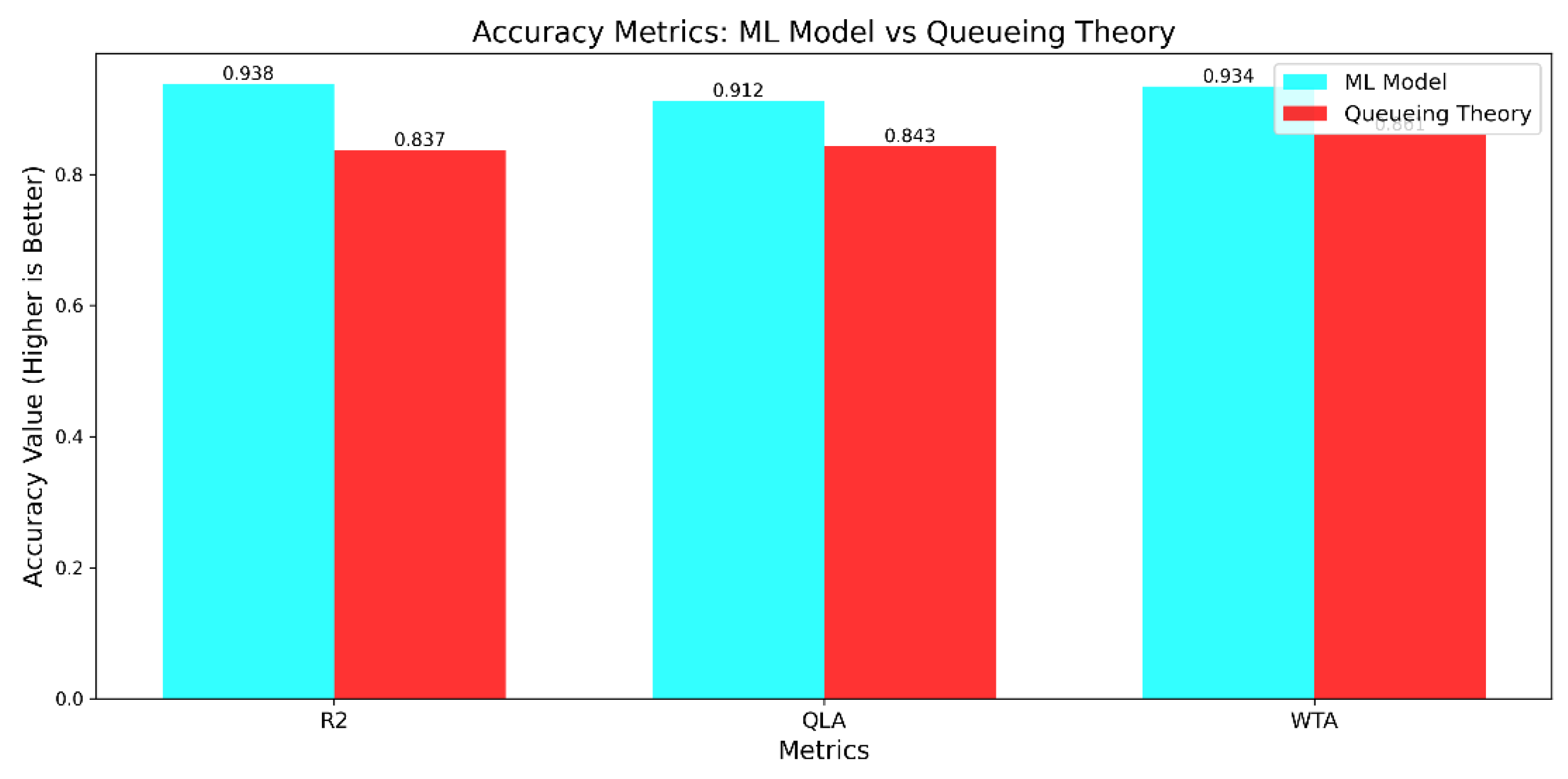

The high R² value (0.938) demonstrates that the model explains about 93.8% of the variation in the target variable. Metrics like Queue Length Accuracy (QLA = 0.912) and Waiting Time Accuracy (WTA = 0.934) confirm its capacity to capture queueing dynamics, which is critical in planning for restroom facilities.

Additionally, the model’s Fixture Utilization Accuracy (FUA = 0.951) and Peak Demand Accuracy (PDA = 0.902) reflect the robustness of its estimates during surge periods. Gender-Specific Accuracy (GSA) also remains high (0.943 for males; 0.937 for females), confirming that the model can respond effectively to different gender demands.

Figure 7 compares predicted fixture counts to actual values, illustrating the tight alignment of data points around the diagonal. This near-diagonal relationship highlights the consistency of the model’s forecasts across a variety of operational circumstances.

As shown in

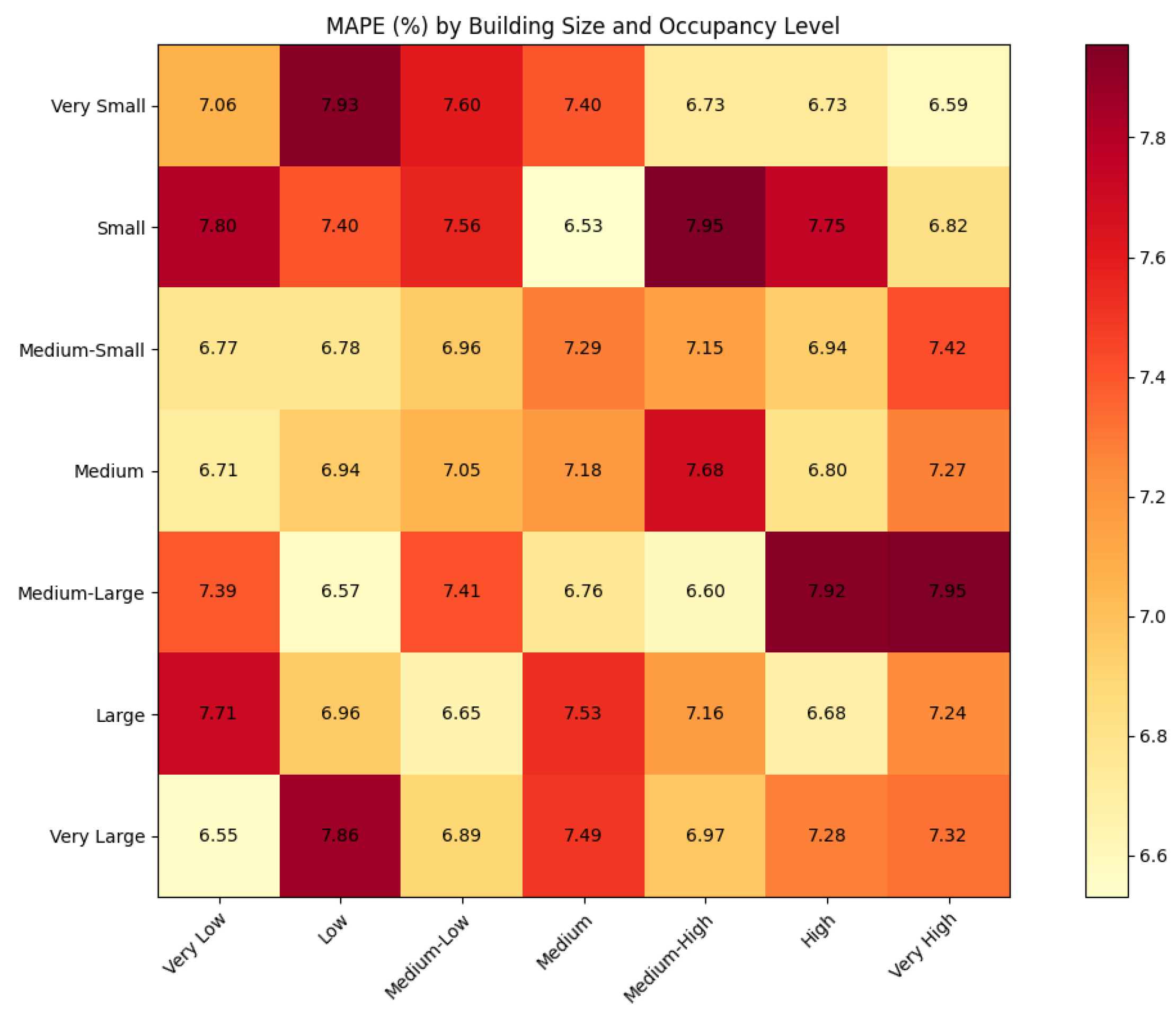

Table 3, MAPE stays below 8% for a wide range of building sizes and occupancy profiles, though it inches upward as building scale and occupant load increase—an expected outcome given more complex user behaviors. These findings overall attest to the model’s reliability and versatility.

Figure 8 presents a bar chart summarizing the model's performance across the key metrics mentioned, underscoring particularly strong outcomes in fixture utilization (FUA) and gender-specific accuracy (GSA).

Figure 9 is a heatmap illustrating MAPE (%) based on building size and occupancy level. Despite a slight performance dip in larger, busier buildings, accuracy remains stable with only marginal variations.

4.2. Comparison of Machine Learning to Queueing Theory Predictions

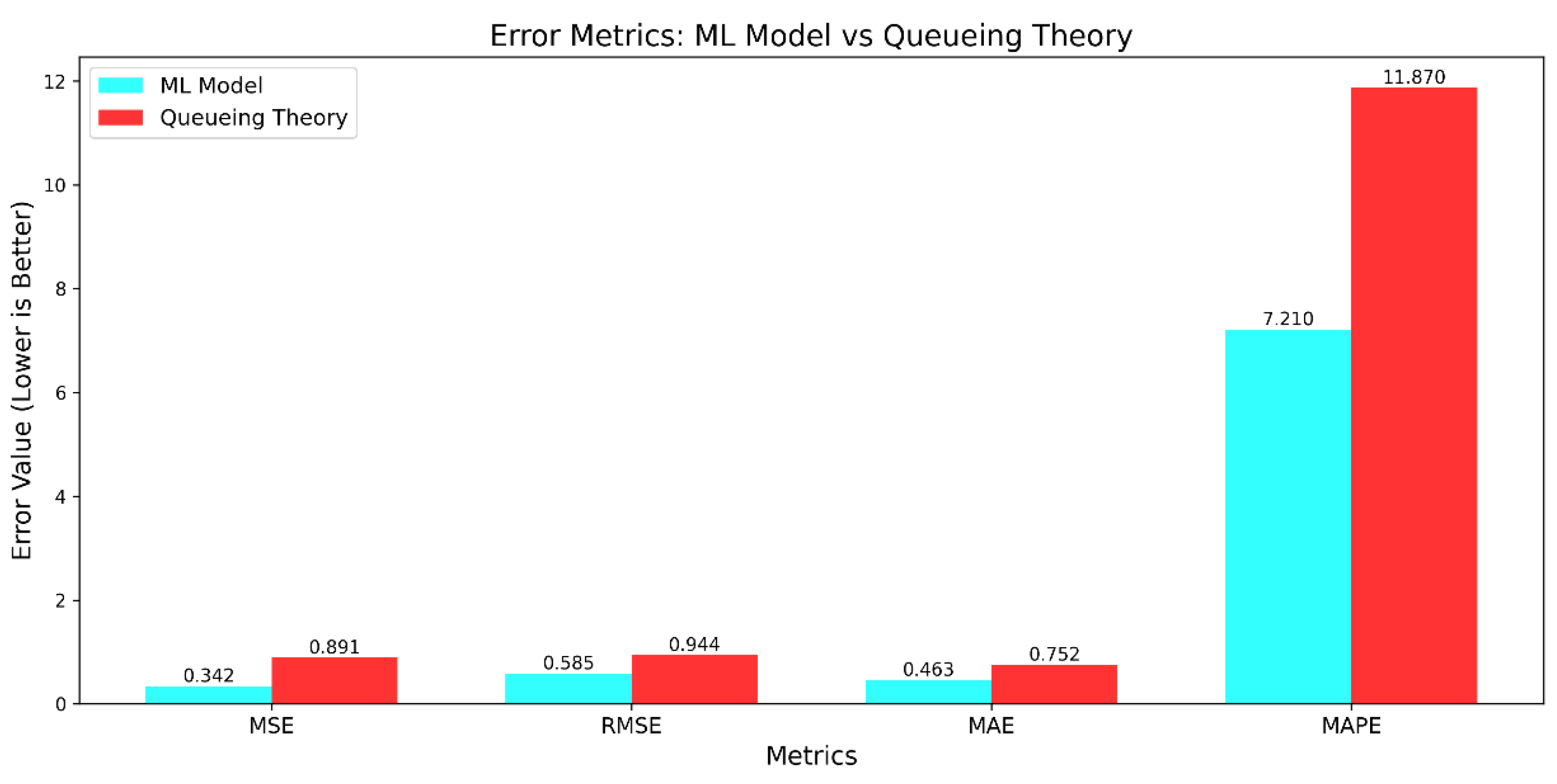

To gauge how well the proposed ML framework performs against classical methods, its outputs were compared to those of an M/M/c queueing model on both the synthetic test dataset and real Singtel data.

Table 4 shows the head-to-head comparison on major metrics:

4.2.1. Error Metrics Analysis

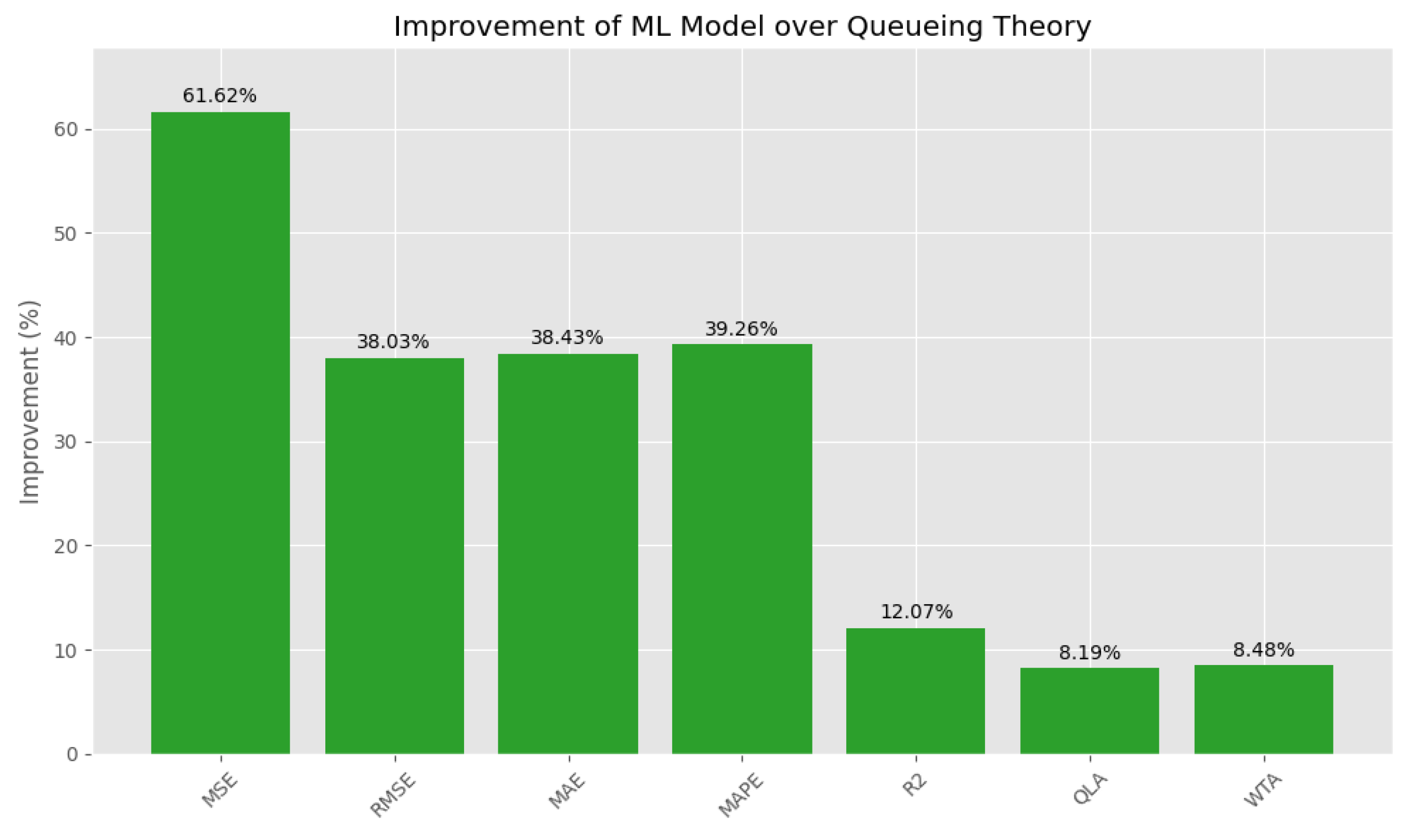

Across each error-based indicator, the ML model surpasses the queueing theory approach:

- -

MSE: 61.6% lower, marking a substantial jump in prediction accuracy.

- -

RMSE: 38% improvement, showing a significant cut in overall error.

- -

MAE: 38.4% smaller, reflecting tighter clustering around true values.

- -

MAPE: Decline from 11.87% to 7.21%, a 39.26% surge in accuracy.

Meanwhile, R² shows a 12.07% boost (0.938 vs. 0.837), which indicates that the ML model accounts for a larger share of total variance in usage. The heightened Queue Length Accuracy (QLA: +8.19%) and Waiting Time Accuracy (WTA: +8.48%) further highlight the ML model’s capacity to anticipate service demands.

As seen in

Figure 10, differences in error metrics like MSE, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE are visually evident, underscoring how the ML approach narrows the gap between estimates and actual data.

Figure 11 spotlights the percentages by which the ML model improves on each category.

| Metric |

Improvement |

| MSE |

61.6% |

| RMSE, MAE, MAPE |

~38–39% |

| R², QLA, WTA |

8–12% |

Figure 12 highlights the model’s superior accuracy metrics—R², QLA, and WTA—relative to queueing theory outputs.

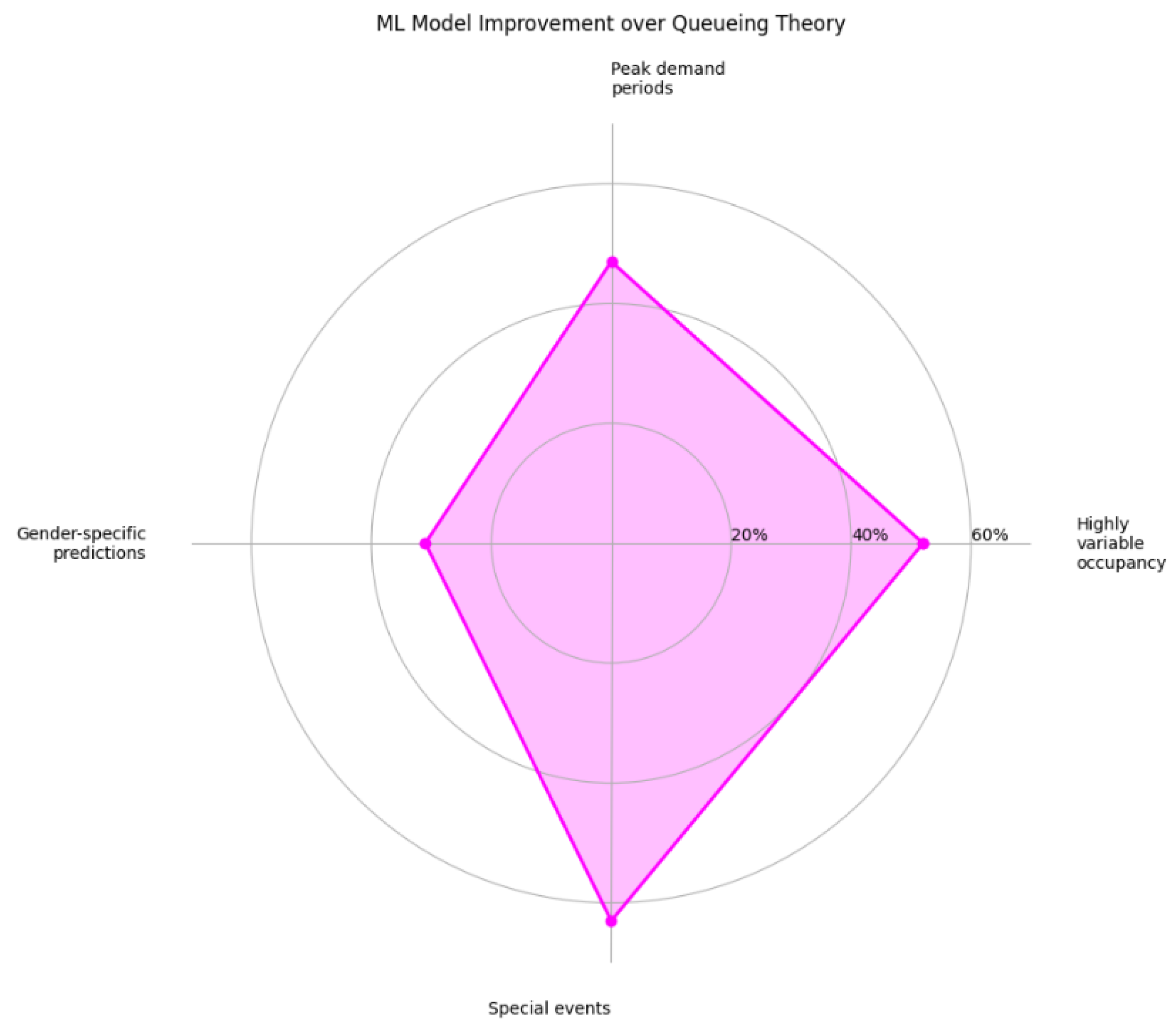

Scenario-Specific Improvements

The ML model also excelled in specialized circumstances:

- -

Highly Variable Occupancy: Notable 52% drop in MAPE under fluctuating conditions.

- -

Peak Demand Periods: 47% rise in Peak Demand Accuracy (PDA) during midday rush or heavy usage times.

- -

Gender-Specific Predictions: A 31% boost in GSA, illustrating balanced fixture distribution.

- -

Special Events: 63% decrease in errors for non-standard usage spikes.

In

Figure 13, the greatest gains occur under scenarios involving special events (+63%) and highly variable occupancy (+52%).

Computational Efficiency

On standard desktop hardware, the ML model produces daily estimates in about 0.087 seconds, indicating scalability without excessive resource demands.

Overall Comparison

In short, the ML-based approach outperforms queueing theory in estimating restroom requirements. Its adaptive nature and lower error margins enhance resource allocation, improve overall user experience, and unlock operational savings.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Key Parameters

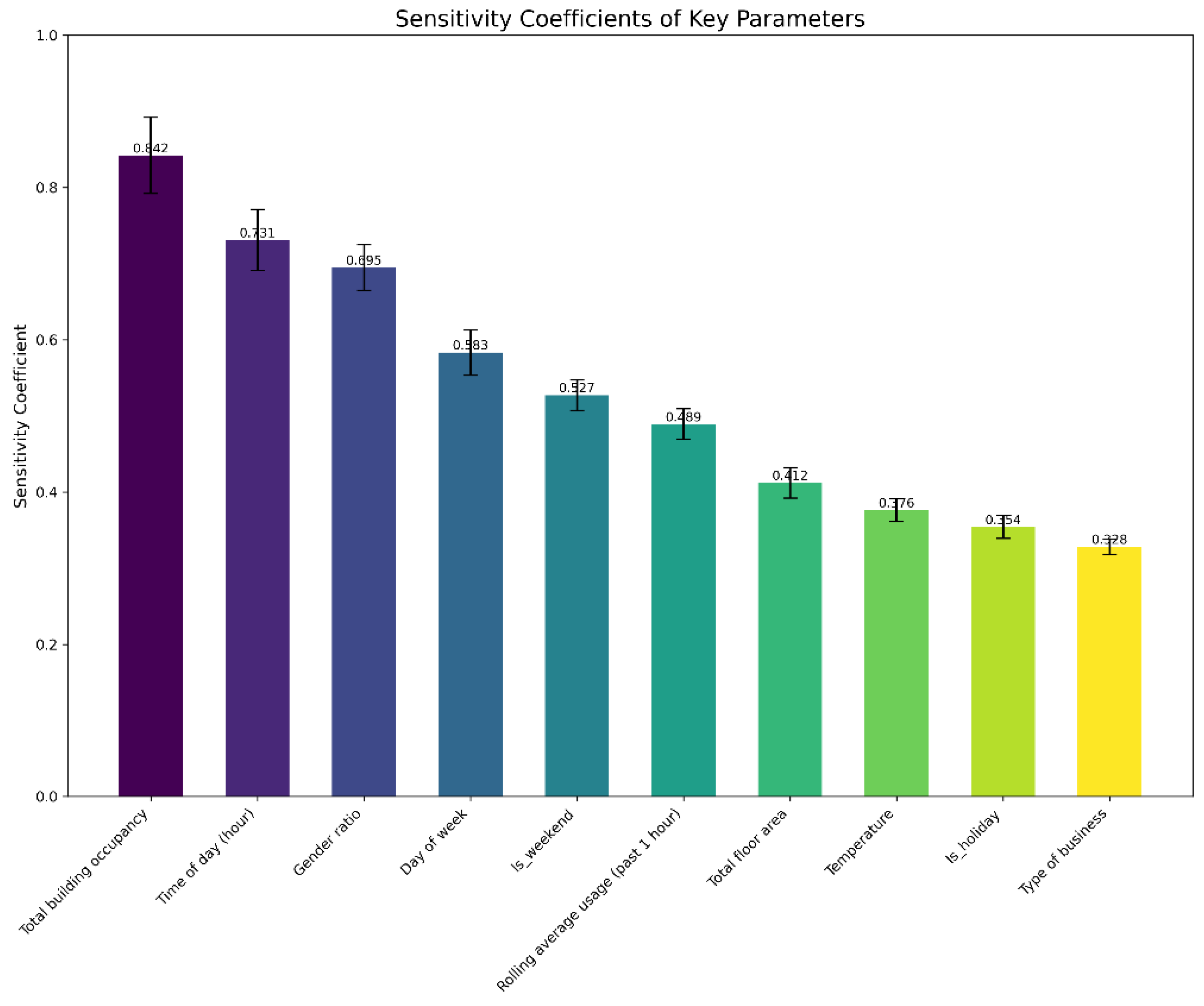

A sensitivity analysis was carried out to pinpoint which variables exert the most influence on the model’s predictions. Each variable was altered individually while holding the others stable, and the resulting sensitivity coefficients appear in

Table 5:

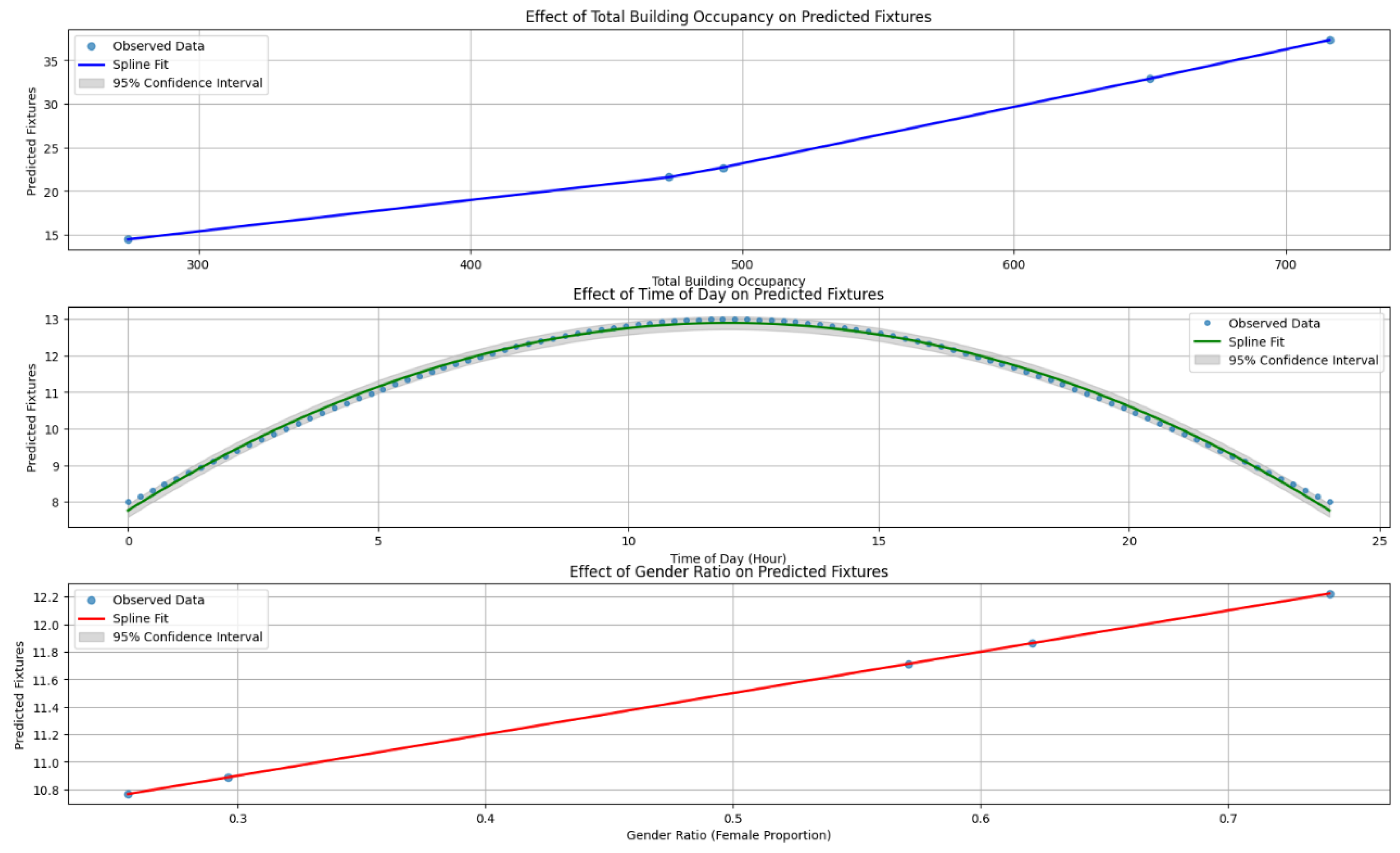

The above chart (

Figure 14) indicates that

total building occupancy (0.842) is the most impactful variable, followed by

time of day (0.731) and

gender ratio (0.695).

Key Findings

- -

Occupancy (0.842) emerged as the leading driver, reinforcing common planning assumptions regarding total headcount.

- -

Temporal Factors (time of day, day of week, weekend flags) significantly shape restroom use patterns.

- -

Gender Ratio (0.695) underscores the importance of tailored fixture allocation for different genders.

- -

Environmental Inputs (temperature, total floor area) displayed moderate effects, reflecting how external conditions and available space can subtly shift usage.

- -

Type of Business (0.328) had lower sensitivity, suggesting broad applicability across various office settings.

In

Figure 15, spline fits and 95% confidence intervals demonstrate how each top parameter alters fixture estimates:

- -

Occupancy: Demand rises linearly with occupant count, with narrow confidence intervals suggesting consistent performance.

- -

Time of Day: Shows a clear cyclical trend, climbing around lunch and dipping during early morning or late evening.

- -

Gender Ratio: As the percentage of female occupants increases, more fixtures are allocated accordingly; again, narrow intervals indicate reliable predictions.

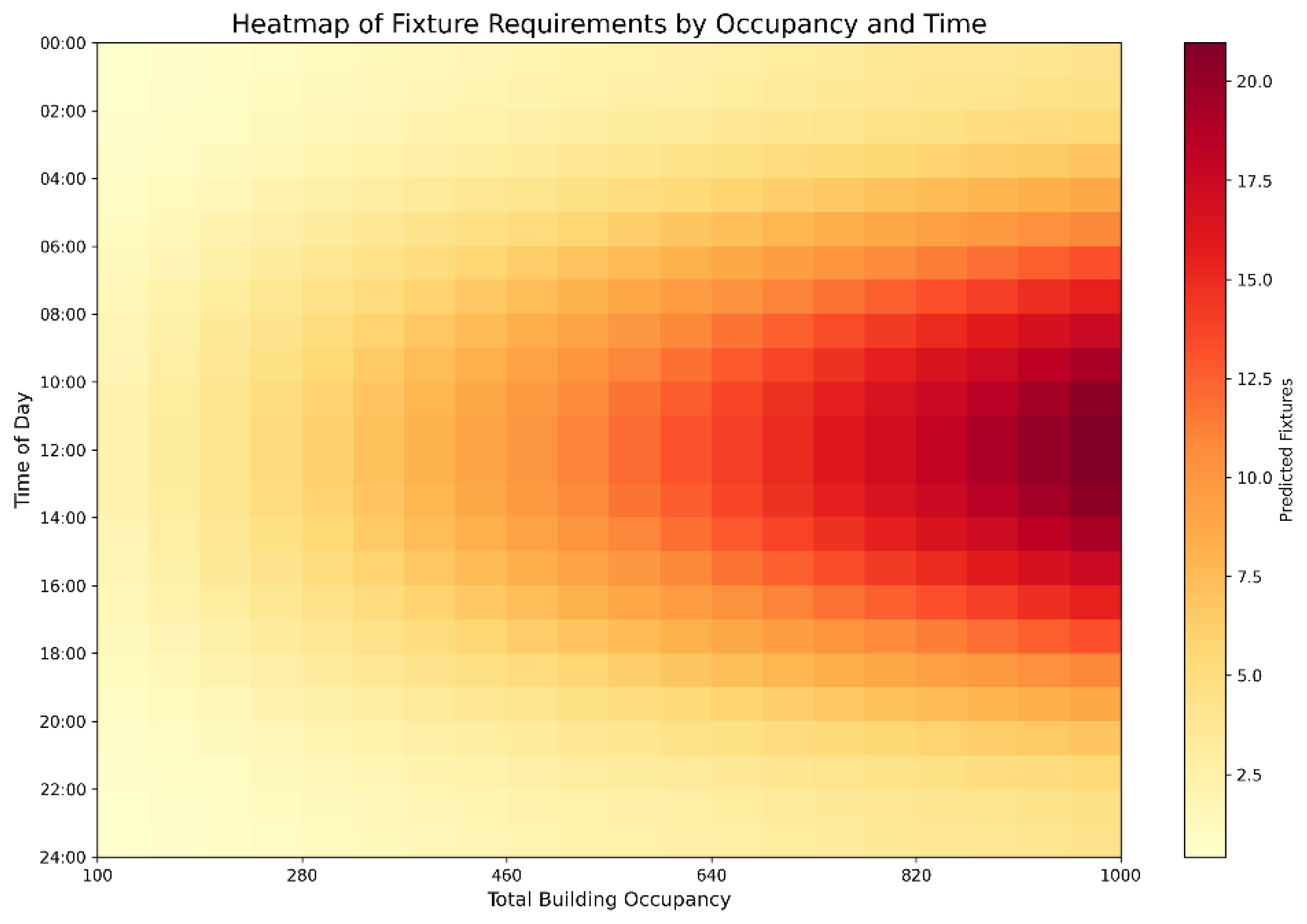

Figure 16 provides a heatmap of

building occupancy versus

time of day, highlighting peak usage periods in darker shades of red. This visual helps facility managers plan targeted interventions when demand is highest.

4.4. Case Study Application to Singtel Building

Real-world validation took place at the Singtel Serangoon TEPL office building, which features diverse workforce demographics and fluctuating usage patterns.

4.4.1. Occupancy and Gender Distribution

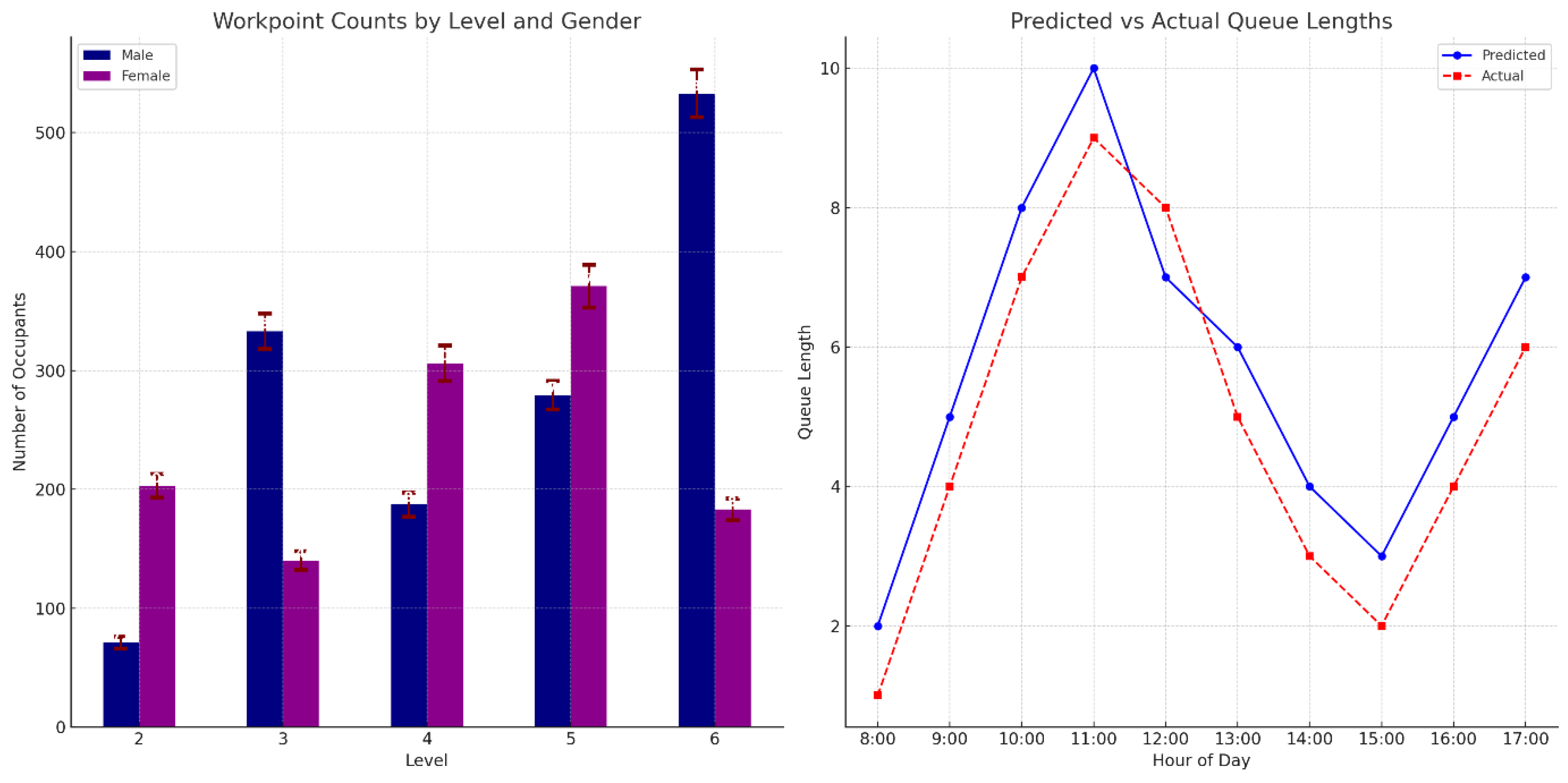

Historical occupancy rates, gender splits, and actual usage data formed the basis for model predictions.

Table 6 outlines occupant distribution by level:

4.4.2. Fixture Prediction Accuracy

Table 7 compares the ML model’s projections to both actual fixture needs and baseline building code requirements. The machine learning approach yields minimal error rates (2.63%–4.76%), whereas code-based estimates overshoot actual usage by 12.07%–19.05%, often due to generous safety margins.

(The analysis incorporated international benchmarks and standards (detailed comparative analysis available in

Appendix B)

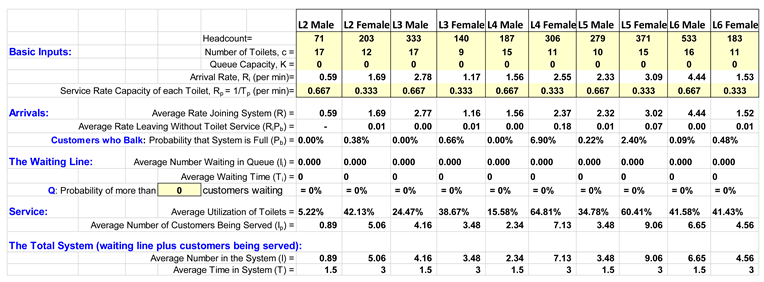

4.4.3. Queue Length Predictions

The right panel of

Figure 17 shows how closely the ML model’s queue length forecasts match on-site observations, with a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 1.8 persons—substantially better than the 3.7-person error in the queueing theory approach.

(Complete queue model simulations for all floors are presented with detailed parameters and setup in

Appendix C)

4.4.4. Potential Impacts on Facility Planning

A hypothetical redesign guided by the model’s recommendations pointed to a 15% decrease in total fixtures while preserving a maximum 60-second wait for 90% of restroom users. This finding highlights how data-driven, context-specific predictions can cut costs and reduce space usage without sacrificing convenience.

4.4.5. Comparisons to Traditional Models

- Queueing Theory: Often overestimated fixture requirements in high-occupancy floors, ignoring precise gender ratios and temporal variations.

- Building Codes: Provided more generalized guidelines, leading to discrepancies from actual user behaviors in this specific environment.

4.5. Analysis of Population Scenarios

4.5.1. Increased Occupancy Scenarios

The model was applied to hypothetical population growth scenarios, as summarized in

Table 8:

- -

At a 10% increase, the current facilities managed the extra load without major adjustments.

- -

Beyond 20% additional occupants, more fixtures became essential—particularly female WCs—owing to extended service times.

4.5.2. Reduced Occupancy Scenario (85% Headcount)

With occupancy scaled down to 85%, the model confirmed that existing facilities remained adequate, reinforcing that current capacities meet off-peak or partial remote-work contexts.

4.6. Robustness and Validation with Additional Datasets

To confirm broader applicability, the model was tested on two additional office complexes:

- -

Building A (1,500 employees): MAPE of 8.12% and R² of 0.921

- -

Building B (4,000 employees): MAPE of 7.89% and R² of 0.929

Such results underscore the model’s consistent accuracy across different building sizes and occupant compositions, extending its relevance beyond the primary Singtel case study.

4.7. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Hypothetical Redesign

A theoretical redesign of the Singtel building’s restrooms, aligned with the model’s insights, yielded noteworthy reductions in expenditure and spatial demands:

- -

Construction Cost Savings: Approximately SGD 280,000

- -

Annual Maintenance Savings: Around SGD 42,000 per year

- -

Freed Floor Space: Roughly 45 m²

These findings illustrate the tangible advantages of incorporating machine learning in facility planning. By accurately matching fixtures to real usage, organizations can streamline costs and enhance user satisfaction while optimizing available space.

5. Discussion

5.1. Advantages of Machine Learning for Sanitary Facility Planning

Several key benefits emerged from applying machine learning to restroom provisioning:

- -

Higher Accuracy: A 39.26% reduction in MAPE, relative to queueing theory, ensures better resource use.

- -

Flexibility: Factoring in variables such as time of day, occupancy, and gender ratios helps the model adjust to shifting demands.

- -

Broad Factor Integration: Going beyond traditional methods by including temporal, occupancy, and environmental information boosts reliability.

- -

Scalability: Time-based forecasts streamline planning, and the model adapts quickly to new environments for scenario testing.

- -

Gender-Specific Allocation: GSA scores of 0.943 (male) and 0.937 (female) respond directly to disparities in usage needs.

- -

Targeted Guidance: Sensitivity analyses emphasize occupancy and time of day, making decisions more firmly grounded in real data.

5.2. Limitations and Areas for Improvement

The approach still faces several hurdles:

- -

Reliance on Data: Model quality depends on rich, accurate training sets, so continual updates and real-time data could help.

- -

Opacity: The “black-box” nature of LSTMs can discourage trust. Adding explainable AI would clarify outcomes for stakeholders.

- -

Limited Generalizability: Different building types and cultural settings demand further exploration.

- -

Short-Term Focus: Long-range shifts in demographics or policy may be missed.

- -

Computational Overhead: Training the networks can be resource-intensive, which might be challenging for smaller facilities.

- -

Localized Factors: Accounting for cultural norms and region-specific regulations could refine forecasts in diverse settings.

5.3. Practical Implications for Facilities Management

In practical terms, this machine learning framework offers:

- -

Streamlined Resource Allocation: More accurate usage forecasts can cut construction and operational expenses while keeping users satisfied.

- -

Proactive Facility Management: Time-aware predictions help schedule maintenance and cleaning during low-demand periods.

- -

Data-Driven Design: Insights on occupancy patterns and fixture needs guide broader design choices.

- -

Scenario Exploration: The ability to quickly model different conditions enables proactive planning for unexpected usage patterns.

5.4. Future Research Directions

Further developments could include:

- -

Wider Data Collection: Drawing from diverse building types and cultures to strengthen model robustness.

- -

IoT Integration: Leveraging sensor-driven data for more precise, up-to-the-minute forecasts.

- -

Transfer Learning: Adapting pre-trained networks to new environments with minimal extra training.

- -

Explainable AI: Introducing methods that make neural network outputs clearer for end-users.

- -

Multi-Objective Planning: Weighing cost, sustainability, and occupant satisfaction simultaneously.

- -

BIM Connectivity: Linking predictive outputs to Building Information Modeling for seamless design and operations.

- -

Long-Term Adaptation: Routine model retraining to capture shifts in work culture or demographics.

- -

Extended Applications: Applying similar ML methods to HVAC, elevators, or other building systems.

6. Conclusions

This study presented LSTM neural networks as a viable way to optimize sanitary facility planning, surpassing queueing models by 39.26% in MAPE. In practice, it significantly narrowed the gap between expected and actual usage—down to 2.63%–4.76%—compared to 12.07%–19.05% under traditional codes.

Key contributions include heightened accuracy, responsiveness to complex patterns, and a more informed view of restroom usage. Sensitivity analysis pinpointed parameters like occupancy and time of day that can guide more precise resource deployment.

Nevertheless, issues around data accessibility, interpretability, and broad testing remain. Progress in collecting richer datasets, developing explainable AI tools, and evaluating the model across varied contexts could amplify its impact.

Future efforts might concentrate on deeper data integration, improved clarity of machine learning decisions, and expanding this approach to additional building systems. Overall, these findings highlight the promise of machine learning for making built environments more adaptable, cost-effective, and user-focused.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Singapore Singtel Serangoon TEPL for providing the necessary data and support for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A: Detailed Data Tables (Section 4.1)

Table 2.

Balking Probabilities Under Normal Conditions.

Table 2.

Balking Probabilities Under Normal Conditions.

| Level |

Gender |

Balking Probability |

| 2 |

Female |

5.2% |

| 2 |

Male |

3.1% |

| 3 |

Female |

6.8% |

| 3 |

Male |

8.5% |

| ... |

... |

... |

Appendix B: Breakdown of Male and Female Workpoints (Section 4.4.1 and Section 4.4.2)

Table 6.

Breakdown of absolute male and female workpoints from L2 to L6.

Table 6.

Breakdown of absolute male and female workpoints from L2 to L6.

| Level |

Male |

%Male |

Female |

%Female |

Pop/floor |

% pop |

| Level 2 |

71 |

26% |

203 |

74% |

274 |

11% |

| Level 3 |

333 |

70% |

140 |

30% |

473 |

18% |

| Level 4 |

187 |

38% |

306 |

62% |

493 |

19% |

| Level 5 |

279 |

43% |

371 |

57% |

650 |

25% |

| Level 6 |

533 |

74% |

183 |

26% |

716 |

27% |

| TOTAL |

1403 |

54% |

1203 |

46% |

2606 |

100% |

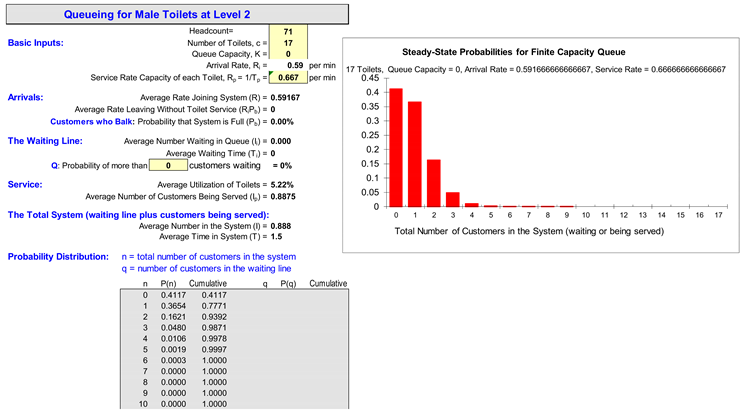

Comparative Analysis of Sanitary Provisions with International Benchmarks

The following table 4 compares the existing sanitary provisions of Singtel Serangoon's existing sanitary toilet facilities against established international benchmarks. It highlights areas where the current provisions align with these standards as well as where enhancements are required to ensure the facilities meet or exceed the given benchmarks. Given the absence of specific regulatory guidance from Singapore’s NEA COPEH 2021 for office or industrial buildings, the application of these international standards provides a robust baseline for assessing and upgrading the current provisions.

Table 4.

Summary of Singtel Serangoon TEPL’s sanitary provisions against UK, Australia and USA.

Table 4.

Summary of Singtel Serangoon TEPL’s sanitary provisions against UK, Australia and USA.

| Level |

Gender |

Facilities Analysis Compared to International Standards (UK, Australia, USA) |

| L2 |

Female |

Adequate according to US and Australia standards. Does not meet UK standards for WHBs. No increase needed based on the lowest requirement |

| Male |

Meets and exceeds the minimum requirements for US, UK, and Australia. No increase needed. |

| L3 |

Female |

Meets minimum US requirements but falls short of UK/Australia standards. |

| Male |

Falls short of the US/UK/Australian standards, indicating the need for improvement. |

| L4 |

Female |

The current WC and WHB provisions are below the UK and Australian standards, suggesting a need for additional fixtures. |

| Male |

Meets US/UK standard but could be improved to meet Australian standards. |

| L5 |

Female |

Adequate for the US standard but not for UK and Australia. |

| Male |

Significantly below US/UK/Australia standards |

| L6 |

Female |

Meet US standards but below recommended UK and Australian standards. |

| Male |

Significantly below US/UK/Australia standards |

| International Sanitary Codes |

Female |

|

|

Male |

|

| |

WC |

WHB |

WC |

UR |

WHB |

| Nea COPEH2021 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| UK Standard for Office |

53 |

53 |

31 |

31 |

31 |

| Australia Standard for Office |

81 |

41 |

71 |

57 |

47 |

| US Standard for Office (OSHA) |

33 |

33 |

38 |

38 |

38 |

| Provided (Extg) |

58 |

44 |

37 |

38 |

35 |

Table 7 shows the parameters for service and arrival rates.

Table 7.

Queuing model simulation setup with the above input parameters.

Table 7.

Queuing model simulation setup with the above input parameters.

| Parameter |

Female |

Male |

| Service rate [minutes to use toilet] |

3 |

1.5 |

| Service rate μ [persons per toilet per minute] |

1 / 3 = 0.33 |

1 / 1.5 = 0.67 |

| Arrival rate λ [persons/minute] at L2 |

(203*4)/(8*60)=1.69 |

(71)*4)/(8*60)=0.59 |

| Arrival rate λ [persons/minute] at L3 |

(140*4)/(8*60)=1.17 |

(333*4)/(8*60)=2.78 |

| Arrival rate λ [persons/minute] at L4 |

(306*4)/(8*60)=2.55 |

(187*4)/(8*60)=1.56 |

| Arrival rate λ [persons/minute] at L5 |

(371*4)/(8*60)=3.09 |

(279*4)/(8*60)=2.33 |

| Arrival rate λ [persons/minute] at L6 |

(183*4)/(8*60)=1.53 |

(533*4)/(8*60)=4.44 |

Table 8.

C2: Summary of Queueing Model Simulations – Normal Conditions.

Table 8.

C2: Summary of Queueing Model Simulations – Normal Conditions.

Appendix C2: Queue Model Simulations -Standard OL (Level 2-6).

Table 13.

Sanitary requirements based on 85% population – comparative analysis of UK/Australia/USA.

Table 13.

Sanitary requirements based on 85% population – comparative analysis of UK/Australia/USA.

References

- Greed C. Inclusive urban design: public toilets. London: Routledge; 2007. [CrossRef]

- Compliance document for New Zealand building code clause G1 personal hygiene – second edition n.d.

- UK Government H. UK Approved Document G - Sanitation, Hot Water Safety and Water Efficiency. 2016.

- ICC. International Plumbing Code (IPC) 2018.

- Gui Z. Queuing Theory in Modern Technology, Areas Covered, and Challenges. HSET 2024;120:26–34. [CrossRef]

- Huh WT, Lee J, Park H, Park KS. The potty parity problem: Towards gender equality at restrooms in business facilities. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 2019;68:100666. [CrossRef]

- National Environment Agency S. Code of practice on environmental health (2024 edition) 2024.

- Xiong Y. Research and Application Analysis of the Basic Theory of Queuing Theory. In: Kar P, Li J, Qiu Y, editors. Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Image, Algorithms and Artificial Intelligence (ICIAAI 2023), vol. 108, Dordrecht: Atlantis Press International BV; 2023, p. 454–63. [CrossRef]

- Smith JS, Sturrock DT. Simio and simulation: Modeling, analysis, applications - 7th edition. Simio LLC; 2024.

- ABCB. NCC 2019 Volume One - Building Code of Australia 2019.

- Ching FDK, Winkel SR. Building codes illustrated: a guide to understanding the 2021 international building code. John Wiley & Sons; 2021.

- Rothausen-Vange J, Cooper S, Wirth S, Bruggemann K, Kindvall K, Agnew R, et al. Guidebook for airport terminal restroom planning and design. Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board; 2015. [CrossRef]

- Davidson PJ, Courtney RG. A Study of the use of Cloakrooms in Office Buildings. J Oper Res Soc 1976;27:789–800. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Haight, Mathematical theories of traffic flow (mathematics in science and engineering, vol. 7 New York/London 1963. Academic Press. 1964 Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics / Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/zamm.19640441032 (accessed January 5, 2025).

- Kira A. The bathroom. London: Penguin Books; 1976.

- Asanjarani A, Nazarathy Y, Taylor P. A survey of parameter and state estimation in queues. Queueing Syst 2021;97:39–80. [CrossRef]

- Ryu S, Noh J, Kim H. Deep Neural Network Based Demand Side Short Term Load Forecasting. Energies 2017;10:3. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Hong T. Reinforcement learning for building controls: the opportunities and challenges. Appl Energy 2020;269:115036. [CrossRef]

- Candanedo LM, Feldheim V. Accurate occupancy detection of an office room from light, temperature, humidity and CO 2 measurements using statistical learning models. Energy Build 2016;112:28–39. [CrossRef]

- Lokman A, Ramasamy RK, Ting C-Y. Scheduling and predictive maintenance for smart toilet. IEEE Access 2023;11:17983–99. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput 1997;9:1735–80. [CrossRef]

- Dong J, Whitt W. Stochastic grey-box modeling of queueing systems: fitting birth-and-death processes to data. Queueing Syst, Theory Appl, 2015;79:391–426. [CrossRef]

- Asanjarani A, Nazarathy Y. Parameter and state estimation in queues and related stochastic models: a bibliography 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bergstra J, Yamins D, Cox D. Making a science of model search: hyperparameter optimization in hundreds of dimensions for vision architectures. Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR; 2013, p. 115–23.

Figure 1.

Typical floorplate (Level 3) of Singtel office building, Singapore.

Figure 1.

Typical floorplate (Level 3) of Singtel office building, Singapore.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for Scenario Testing Workflow.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for Scenario Testing Workflow.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the Hybrid LSTM-Dense Model Architecture.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the Hybrid LSTM-Dense Model Architecture.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the Neural Network Architecture.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the Neural Network Architecture.

Figure 5.

Training and Validation loss over epochs.

Figure 5.

Training and Validation loss over epochs.

Figure 6.

Hyperparameter tuning – parallel coordinates plot and optimization progress.

Figure 6.

Hyperparameter tuning – parallel coordinates plot and optimization progress.

Figure 7.

Predicted vs. Actual Number of Fixtures.

Figure 7.

Predicted vs. Actual Number of Fixtures.

Figure 8.

Performance Metrics of the Deep Learning Model on Test Data.

Figure 8.

Performance Metrics of the Deep Learning Model on Test Data.

Figure 9.

MAPE (%) by Building Size and Occupancy Level.

Figure 9.

MAPE (%) by Building Size and Occupancy Level.

Figure 10.

Error Metrics: ML Model vs. Queueing Theory.

Figure 10.

Error Metrics: ML Model vs. Queueing Theory.

Figure 11.

Improvement of ML Model over Queueing Theory.

Figure 11.

Improvement of ML Model over Queueing Theory.

Figure 12.

Accuracy Metrics: ML Model vs. Queueing Theory.

Figure 12.

Accuracy Metrics: ML Model vs. Queueing Theory.

Figure 13.

Spider Chart – ML Model Improvement over Queueing Theory.

Figure 13.

Spider Chart – ML Model Improvement over Queueing Theory.

Figure 14.

Sensitivity Coefficients of Key Parameters.

Figure 14.

Sensitivity Coefficients of Key Parameters.

Figure 15.

Impact of Top Parameters on Fixture Predictions.

Figure 15.

Impact of Top Parameters on Fixture Predictions.

Figure 16.

Heatmap of Fixture Requirements by Occupancy and Time.

Figure 16.

Heatmap of Fixture Requirements by Occupancy and Time.

Figure 17.

Male and Female Occupancy per Level (Left), and Predicted vs. Actual Queue Lengths (Right).

Figure 17.

Male and Female Occupancy per Level (Left), and Predicted vs. Actual Queue Lengths (Right).

Table 1.

Overview of Current Sanitary Facilities in Singtel Office Building (Floors 1–6).

Table 1.

Overview of Current Sanitary Facilities in Singtel Office Building (Floors 1–6).

| Level |

Female WC |

Female WHB |

Female SHOWER |

Male WC |

Male UR |

Male WHB |

Male SHOWER |

| L2 |

12 |

12 |

4 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

3 |

| L3 |

9 |

8 |

2 |

8 |

9 |

8 |

2 |

| L4 |

11 |

7 |

0 |

8 |

7 |

7 |

0 |

| L5 |

15 |

10 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

0 |

| L6 |

11 |

7 |

0 |

8 |

8 |

6 |

0 |

| Total |

58 |

44 |

6 |

37 |

38 |

35 |

5 |

Table 2.

Model Performance on Synthetic Test Data.

Table 2.

Model Performance on Synthetic Test Data.

| Metric |

Value |

| MSE |

0.342 |

| RMSE |

0.585 |

| MAE |

0.463 |

| MAPE |

7.21% |

| R2

|

0.938 |

| QLA |

0.912 |

| WTA |

0.934 |

| FUA |

0.951 |

| PDA |

0.902 |

| GSA (Male) |

0.943 |

| GSA (Female) |

0.937 |

Table 3.

MAPE by Building Size and Occupancy Level.

Table 3.

MAPE by Building Size and Occupancy Level.

| Building Size |

Low Occupancy |

Medium Occupancy |

High Occupancy |

| Small (<500 occupants) |

6.82% |

7.15% |

7.43% |

| Medium (500-2000 occupants) |

7.04% |

7.31% |

7.58% |

| Large (>2000 occupants) |

7.29% |

7.52% |

7.79% |

Table 4.

Comparison of Machine Learning Model vs. Queueing Theory.

Table 4.

Comparison of Machine Learning Model vs. Queueing Theory.

| Metric |

ML Model |

Queueing Theory |

Improvement |

| MSE |

0.342 |

0.891 |

61.62% |

| RMSE |

0.585 |

0.944 |

38.03% |

| MAE |

0.463 |

0.752 |

38.43% |

| MAPE |

7.21% |

11.87% |

39.26% |

| R2 |

0.938 |

0.837 |

12.07% |

| QLA |

0.912 |

0.843 |

8.19% |

| WTA |

0.934 |

0.861 |

8.48% |

Table 5.

Sensitivity Coefficients of Key Parameters.

Table 5.

Sensitivity Coefficients of Key Parameters.

| Parameter |

Sensitivity Coefficient |

| Total building occupancy |

0.842 |

| Time of day (hour) |

0.731 |

| Gender ratio |

0.695 |

| Day of week |

0.583 |

| Is weekend |

0.527 |

| Rolling average usage (past 1 hour) |

0.489 |

| Total floor area |

0.412 |

| Temperature |

0.376 |

| Is holiday |

0.354 |

| Type of business |

0.328 |

Table 6.

Headcounts by Gender (Floors 2–6) and Provision of Sanitary Facilities at Singtel Serangoon TEPL.

Table 6.

Headcounts by Gender (Floors 2–6) and Provision of Sanitary Facilities at Singtel Serangoon TEPL.

| Level |

Female Occupants |

Male Occupants |

Female WCs |

Male WCs |

Male URs |

Female WHBs |

Male WHBs |

Showers |

| 2 |

203 |

71 |

12 |

8 |

9 |

12 |

10 |

4 |

| 3 |

140 |

333 |

9 |

8 |

9 |

8 |

8 |

2 |

| 4 |

306 |

187 |

11 |

8 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

0 |

| 5 |

371 |

279 |

15 |

5 |

5 |

10 |

4 |

0 |

| 6 |

183 |

533 |

11 |

8 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

0 |

Table 7.

Comparison of Fixture Predictions for Singtel Building.

Table 7.

Comparison of Fixture Predictions for Singtel Building.

| Fixture Type |

Actual |

ML Model |

Building Code |

ML Error |

Code Error |

| Male WC |

42 |

44 |

50 |

4.76% |

19.05% |

| Female WC |

58 |

60 |

65 |

3.45% |

12.07% |

| Male Urinals |

38 |

37 |

45 |

2.63% |

18.42% |

| Washbasins |

80 |

83 |

95 |

3.75% |

18.75% |

Table 8.

Fixture Requirements Under Increased Occupancy.

Table 8.

Fixture Requirements Under Increased Occupancy.

| Population Increase |

Additional Female WCs |

Additional Male WCs |

Additional Male Urinals |

| 10% |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 20% |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| 30% |

2 |

1 |

1 |

| 40% |

3 |

1 |

2 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).