Submitted:

04 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

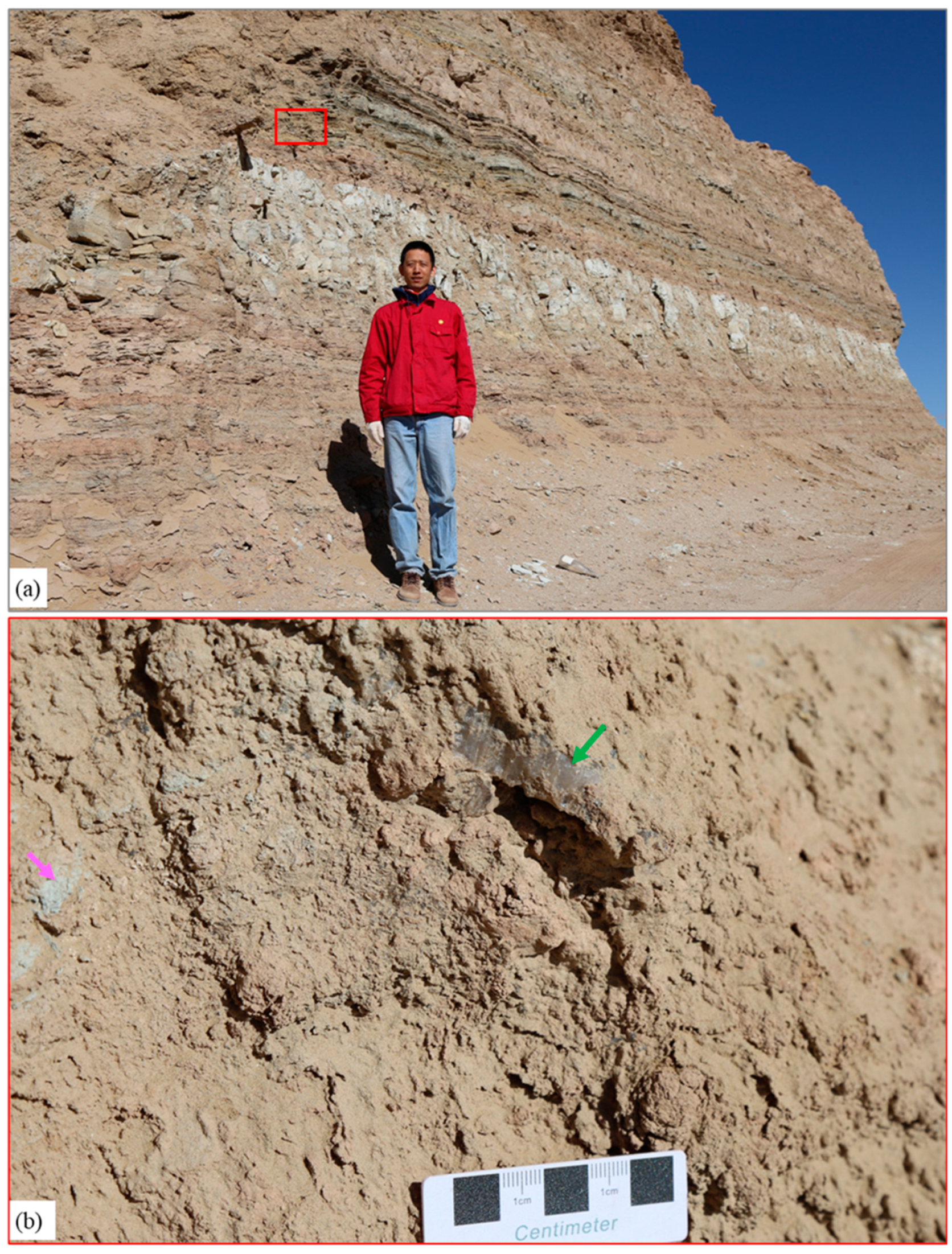

S-wave seismic data are unaffected by natural gas trapped in strata, making them a valuable tool for seismic sedimentology. In this study, S-wave seismic data were utilized to construct an isochronous framework and analyze evaporative facies in the Quaternary biogenic gas-bearing Taidong area, Sanhu Depression, Qaidam Basin, NW China, with calibration from wireline logs and modern analogs. Techniques of phase rotation, frequency decomposition, R (Red), G (Green), B (Blue) fusion, and stratal slices were integrated to reconstruct seismic geomorphological features within the isochronous framework. Linear and sub-circular morphologies, resembling those observed in modern saline pans such as Lake Chad, were identified. Observations from Upper Pleistocene outcrops of anhydrite and halite at Yanshan, east of the Taidong area, salinity measurements from Well TX1 to the north, and lithological and paleo-environmental records from boreholes SG-5, SG-1, and SG-1b to the northwest support the seismic findings. The RGB-fused slices generated from the S-wave seismic data in Taidong area indicate a progressive increase in the occurrence of evaporative features from the K2 standard zone upwards. The vertical occurrence of evaporative facies in the Taidong area mirrors the contemporary regional and global paleo-environmental changes. The interpretation of Quaternary stratal slices from seismic sedimentology—spanning K2, K1, and K0 standard zones—reveals a transition from a freshwater lake to brackish, saline, and finally, a dry saline pan, overlaid by silt. This analysis provides valuable insights into locating evaporites as cap rocks for biogenic gas accumulation and also into mining the evaporite resources in shallow layers of the Taidong area.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Data and method

3.1. Data

3.2. Method

4. Results and Interpretation

4.1. Results

4.2. Interpretation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowen, B. B.; Kipnis, E. L.; Raming, L. W. Temporal dynamics of flooding, evaporation, and desiccation cycles and observations of salt crust area change at the Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah. Geomorphology. 2017, 299, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czauner, B.; Szabó, Z.; Márton, B.; Mádl-Sz˝onyi, J. Basin-scale hydraulic evaluation of groundwater flow controlled biogenic gas migration and accumulation in the central Pannonian Basin. Water. 2023, 15, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, D. R.; George, E. C. Generation, accumulation, and resource potential of biogenic gas. AAPG Bulletin. 1981, 65, 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Efrina, C. A. P.; Hermes, P.; Hamriani, R.; Nor, S. H. Biogenic gas – “from drilling hazard to promising future hydrocarbon resource”: Study of Mamberamo Frontier Basin, north Papua, Indonesia. BIO Web of Conferences. 2023, 73, 04007. [Google Scholar]

- Gac, J. Y.; Al-Droubi, A.; Paquet, H.; Fritz, B.; Tardy, Y. Chemical model for origin and distribution of elements in salts and brines during evaporation of waters. Application to some saline lakes of Tibesti, Chad. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth. 1979, 11, 149–158.

- George, E. C.; Charles, N. T.; Leslie B., M. Biogenic and thermogenic origins of natural gas in Cook Inlet Basin, Alaska. AAPG Bulletin. 1980, 64, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, L. H. Concentration of potash salts in saline basins. AAPG Bulletin. 1969, 53, 790–797. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall, T. M.; North, C. P.; Glennie, K. W. Surface and subsurface sedimentary structures produced by salt crusts. Sedimentology. 2000, 47, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanford, C. R. A process-sedimentary framework for characterizing recent and ancient sabkhas. Sedimentary Geology. 1981, 30, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heermance, R. V.; Pullen, A.; Kapp, P.; Garzione, C. N.; Bogue, S.; Ding, L.; Song, P. Climatic and tectonic controls on sedimentation and erosion during the Pliocene-Quaternary in the Qaidam Basin (China). GSA Bulletin. 2013, 125, 833–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.; Purves, S.J.; Fisher, G.; Leppard, C. Delineation of geological elements from seismic attributes and RGB blending. Lead. Edge. 2008, 27, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isiorho, S. A.; Matisoff, G.; Wehn, K. S. Seepage relationships between Lake Chad and the Chad aquifers. Ground Water. 1996, 34, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Zhang, M.; Tang, L.; Li, J. Evolution of Meso-Cenozoic Qaidam Basin and its control on oil and gas. Oil & Gas Geology. 2004, 25, 603–608.

- John, D. G.; George, F. H. Giant gas fields of northern west Siberia. AAPG Bulletin. 1986, 70, 830–852. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham, A. Shoreline Evolution, Aeolian deflation and anhydrite distribution of the Holocene, Abu Dhabi. GeoArabia. 1997, 2, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, C. Exploration methods for late Quaternary shallow biogenic gas reservoirs in the Hangzhou Bay area, eastern China. AAPG Bulletin. 2010, 94, 1741–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ye, C.; Yang, R.; Appel, E.; Fang, X. Global change modulated Asian inland climate since 7.3Ma: Carbonate manganese records in the western Qaidam Basin. Frontiers in Earth Science. 2021, 9, 1–11.

- Liu, Z.; Sun, S.; Yang, F.; Zhou, Z. Quaternary stratigraphy and its chronology analysis from Sanhu region of Qaidam Basin. Science in China (Series B). 1990, 11, 1201–1212.

- Lowenstein, T. K.; Hardie, L. A. Criteria for the recognition of salt-pan evaporites. Sedimentology. 1985, 32, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Ma, Y.; Lü, S.; Han, W.; Han, S.; Han, F.; Fang, X. Systematic boron isotope analysis on a Quaternary deep SG-1 core from the Qaidam Basin, NE Tibetan Plateau and its paleoclimate implication. Quaternary International. 2022, 631, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugli, S.; Schreiber, B. C.; Triberti, B. Giant polygons in the Realmonte mine (Agrigento, Sicily): Evidence for the desiccation of a Messinian halite basin. Journal of Sedimentary Research Section A-Sedimentary Petrology & Processes. 1999, 69, 764–771.

- Ma, F.; Lv, P.; Cao, M. The Effects of Wind Regime and Sand Supply on the Coexistence of Barchans and Linear Dunes in China’s Qaidam Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 897640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, S.; Broccoli, A.J. Mountains and arid climates of middle latitudes. Science, 1990, 247, 192–195limates of middle latitudes.

- Morris, R. C.; Dickey, P. A. Modern evaporite deposition in Peru. AAPG Bulletin. 1957, 41, 2467–2474. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, M. R.; Stillings, L. L.; Kane, T.; Campbell, K.; Vitale, M. P. G.; Spanjers, R. P.G. Li and Ca enrichment in the Bristol dry lake brine compared to brines from Cadiz and Danby dry lakes, Barstow-Bristol Trough, California, USA. Minerals. 2020, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fang, X.; Appel, E.; Song, C. Pliocene-Pleistocene climate change at the NE Tibetan Plateau deduced from lithofacies variation in the drill core SG-1, western Qaidam Basin, China. J. Sediment. Res. 2012, 82, 933–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wara, M. W.; Ravelo, A. C.; Delaney, M. L. Permanent El Niño-Like conditions during the Pliocene warm period. Science. 2005, 309, 758–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, J.K. Evaporites: A Geological compendium (second edition). Springer International Publishing Switzerland, 2016.

- Williams, C. J. R.; Lord. N. S.; Kennedy-Asser, A. T.; Richards, D. A.; Crucifix, M.; Kontula, A.; Thorne, M.; Valdes, P. J.; Foster, G. L.; Brown, R.; McClymont, E. L.; Lunt, D. J. The relative role of orbital forcing, CO2 and ice sheet feedbacks on Quaternary climate. 2024, Preprint.

- Xu, Z.; Hu, S.; Wang, L.; Zhao, W.; Cao, Z.; Wang, R.; Shi, S.; Jiang, L. Seismic sedimentologic study of facies and reservoir in middle Triassic Karamay Formation of the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, China. Marine and Petroleum Geology. 2019, 107, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Y; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Z. Application of 9-component S-wave 3D seismic data to study sedimentary facies and reservoirs in a biogas-bearing area: A case study on the Pleistocene Qigequan Formation in Taidong area, Sanhu Depression, Qaidam Basin, NW China. PETROL. EXPLOR. DEVELOP. 2024, 51, 647–660.

- Zeng, H.; Henry, S. C.; Riola, J. P. Stratal slicing: Part II. Real seismic data. Geophysics. 1998, 63, 514– 522.

- Zeng, H.; Hentz, T. F. High-frequency sequence stratigraphy from seismic sedimentology: applied to Miocene, Vermilion Block 50, Tiger Shoal area, offshore Louisiana. AAPG Bulletin. 2004, 88, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Zhao, W.; Xu, Z.; Fu, Q.; Hu, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, B. Carbonate seismic sedimentology: A case study of Cambrian Longwangmiao Formation, Gaoshiti-Moxi area, Sichuan Basin, China. PETROL. EXPLOR. DEVELOP. 2018, 45, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, T.; Fang, X.; Zhang, T.; Yan, M.; Zan, J.; Yang, Y.; Khatri, D. B. Chronological and rock magnetic constraints on the transition of the Quaternary paleoclimate in the western Qaidam Basin, NE Tibetan Plateau. Quaternary Research. 2021, 104, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).