1. Prime Ministerial Appointment Gridlocks

In semi-presidential countries or presidential countries with prime ministers, it is commonly stipulated in the constitutions that the president needs approval from the parliament to appoint the prime minister. However, if the president and the parliament majority belong to opposing parties, the parliament may refuse to approve the nomination, even repeatedly, resulting in a gridlock. This is called an appointment gridlock in this paper.

In presidential countries, appointment gridlocks occur also for other executive officials. For example, in the United States, appointments of cabinet members need to be confirmed by the Senate. However, it is perceived by the present author that it is much more difficult to resolve appointment gridlocks for executive officials other than prime minister within the presidential setting. While that topic may be explored in a future paper, the current study is limited to the analysis of prime ministerial appointment gridlocks.

Prime ministerial appointment gridlocks are worth studying also because of their high visibility. In countries with prime ministers, the president makes decisions on ministerial appointments based on the prime minister’s proposals, without requiring further parliamentary approval. Essentially, controlling the prime minister means having near-total control over the government. As a result, neither the president nor the parliament will easily give up this position.

We conducted a survey

1 on the prime ministerial appointment procedures of the 55 UN members that have a semi-presidential system or a presidential system with a prime minister, and our findings are tabulated below. For ease of comparison, the countries are divided into 5 geopolitical groups: mainstream European countries, Russia and former Soviet countries strongly influenced by Russia, Asian-Pacific countries, African countries, and American countries.

| Country |

Prime Minister Must Be a Member of Parliament |

Parliamentary Approval Required before Appointment |

Parliament Can Remove Prime Minister by Vote of No-Confidence with Simple Majority |

President Can Dissolve Parliament after [How Many Approval Failures or How Long after First Nomination, Pass of No-Confidence] |

| Austria |

Normally YES |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, SP1] |

| Bulgaria |

Normally YES |

YES |

YES |

[2, NO] |

| Croatia |

Normally YES |

YES |

YES |

[2, YES] |

| Czech Republic |

Normally YES |

NO |

YES |

[2 Months, NO] |

| Finland |

Normally YES |

YES |

YES |

[Reasonable Time, NO] |

| France |

Normally YES |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Georgia |

Normally YES |

YES |

YES |

[2, NO] |

| Lithuania |

Normally YES |

YES |

YES |

[2, NO] |

| Moldova |

Normally YES |

YES |

YES |

[45 Days, NO] |

| North Macedonia |

YES |

YES |

YES |

[20 Days, YES] |

| Portugal |

YES |

YES |

YES |

[2, SP2] |

| Romania |

Normally YES |

YES |

YES |

[60 Days, YES] |

| Serbia |

YES |

YES |

NO |

[3, YES] |

| Ukraine |

NO |

YES |

NO |

[60 Days, YES] |

| Russia |

NO |

YES |

SP3 |

[3 Months, SP3] |

| Azerbaijan |

NO |

YES |

NO |

[3 or 3 Months, YES] |

| Belarus |

NO |

YES |

NO |

[3, NO] |

| Kazakhstan |

NO |

YES |

NO |

[3, YES] |

| Kyrgyzstan |

YES |

YES |

SP4 |

[3, YES] |

| Tajikistan |

NO |

YES |

NO |

[1 Month, YES] |

| Turkmenistan |

NO |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, NO] |

| Uzbekistan |

NO |

YES |

YES |

[2, NO] |

| Korea (South) |

NO |

YES |

NO |

[NO, NO] |

| Mongolia |

YES |

YES |

YES |

[30 Days, NO] |

| Sri Lanka |

YES |

NO |

YES |

[1 Month, NO] |

| Timor-Leste (East Timor) |

YES |

YES |

YES |

[30 Days, YES] |

| Algeria |

NO |

YES |

YES |

[1, YES] |

| Burundi |

NO |

YES |

NO |

[Not Specified, SP2] |

| Cabo Verde |

NO |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, NO] |

| Cameroon |

NO |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Central African Republic |

NO |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Comoros |

NO |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, NO] |

| Congo (Brazzaville) |

NO |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Congo (Kinshasa) |

NO |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Côte d’Ivoire |

NO |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, NO] |

| Djibouti |

NO |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, NO] |

| Egypt |

NO |

YES |

YES |

[30 Days, NO] |

| Gabon |

NO |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Guinea |

NO |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Guinea-Bissau |

NO |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Madagascar |

NO |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Mauritania |

NO |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, SP5] |

| Mozambique |

NO |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Namibia |

YES |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Niger |

NO |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Rwanda |

NO |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, SP6] |

| Sao Tome and Principe |

NO |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Senegal |

NO |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Tanzania |

YES |

YES |

YES |

[60 Days, NO] |

| Togo |

NO |

NO |

NO |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Tunisia |

Normally YES |

YES |

YES |

[4 Months, NO] |

| Uganda |

YES |

YES |

YES |

[NO, NO] |

| Guyana |

YES |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, SP2] |

| Haiti |

YES |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, NO] |

| Peru |

NO |

NO |

YES |

[Not Applicable, YES] |

SP1: The president can dissolve the parliament if several chancellors in a row failed to secure parliamentary confidence. SP2: No explicit

mention of dissolution for this reason. But the president can dissolve the parliament for a wide range of reasons. SP3: A single pass of

no-confidence can be disregarded, but if no-confidence is passed for the second time within three months, either the prime minister is

removed or the president dissolves the state duma and the prime minister stays until a new prime minister is in place. SP4: In the case

of no-confidence, the president has the option to retain the prime minister, but this can only happen once within a term of parliament. If

a second no-confidence vote is passed, the president must remove the prime minister and appoint a new one. SP5: If, in an interval of

less than 3 years, two changes of government have intervened following a vote of no-confidence or of a motion of censure, the president

can, after consulting the national assembly, pronounce the dissolution of it. SP6: No explicit mention of dissolution for this reason. But

the president can dissolve the parliament for a wide range of reasons, albeit only once.

We see that there are already three measures for avoiding or controlling prime ministerial appointment gridlocks: parliament membership requirement, relinquishment of prior approval, and dissolution of parliament. These measures are discussed below one by one.

Parliament membership requirement: All parliamentary countries have this requirement, so semi-presidential countries with strong parliamentary influence naturally have this requirement too. Thus the original purpose of this requirement is by no means avoiding gridlocks. But it indeed serves that purpose, as it dramatically reduces the number of choices that the president and the parliament have.

Relinquishment of prior approval: Several countries, such as France and Togo, have relinquished the requirement for the president to obtain formal parliamentary approval to appoint the prime minister, thereby eliminating appointment gridlocks. To be considered semi-presidential, these countries must allow the parliament to remove the prime minister with a simple majority, as France does. Those countries without this provision but with relinquishment of prior approval should be classified as presidential or even authoritarian ones.

Dissolution of parliament: Dissolving the parliament is the last resort to resolve a gridlock. In relation to prime minister, there are three scenarios that may call for the dissolution of the parliament: 1) In parliamentary countries, the parliament is so fragmented that they cannot even elect a prime minister for a prolonged period. This is quite rare. 2) In semi-presidential countries, The president and parliament are unable to find a candidate for prime minister who is acceptable to both sides for a long time. 3) The parliament has expressed no-confidence in the prime minister, but the president wants to retain them. Despite its high cost and potential for abuse, parliament dissolution is effective against gridlocks for two reasons: 1) It has deterrent effect to parliament members. 2) The new parliament may have a very different political composition than the old parliament. However, if the new parliament insists on the position of the old parliament, then either the gridlock persists or the president has to surrender, because a freshly elected parliament cannot be dissolved.

France is the prototype of a semi-presidential system. It has adopted all the above three measures, and it is indeed excellent both in eliminating gridlocks and in overall governance. In later sections, the measures used by France will be referenced for discussion.

2. Prime Ministerial Appointment Gridlocks in Korea

References [

1,

2] have focused on the comparative study of prime ministerial appointment gridlocks, offering a broad overview of the topic. In contrast, our paper is specifically focused on Korea

2, making it closely tied to the country’s political system. It is more solution-oriented and offers more technical detail than the existing studies.

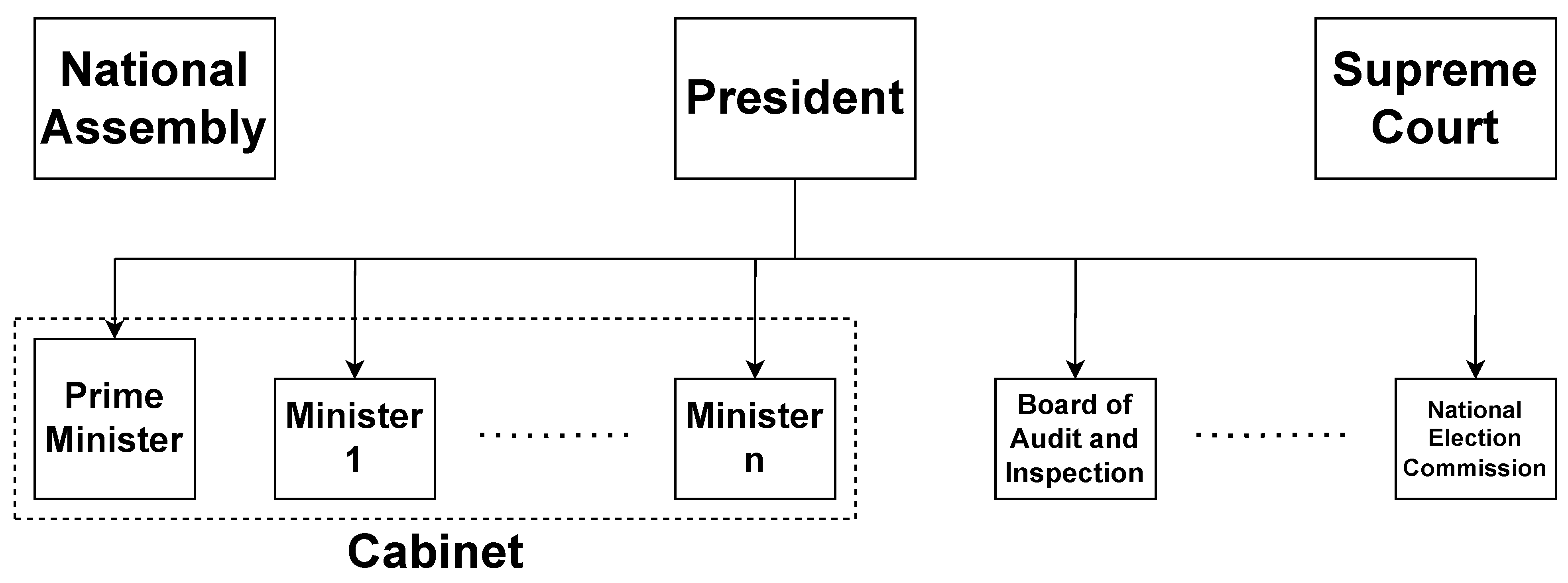

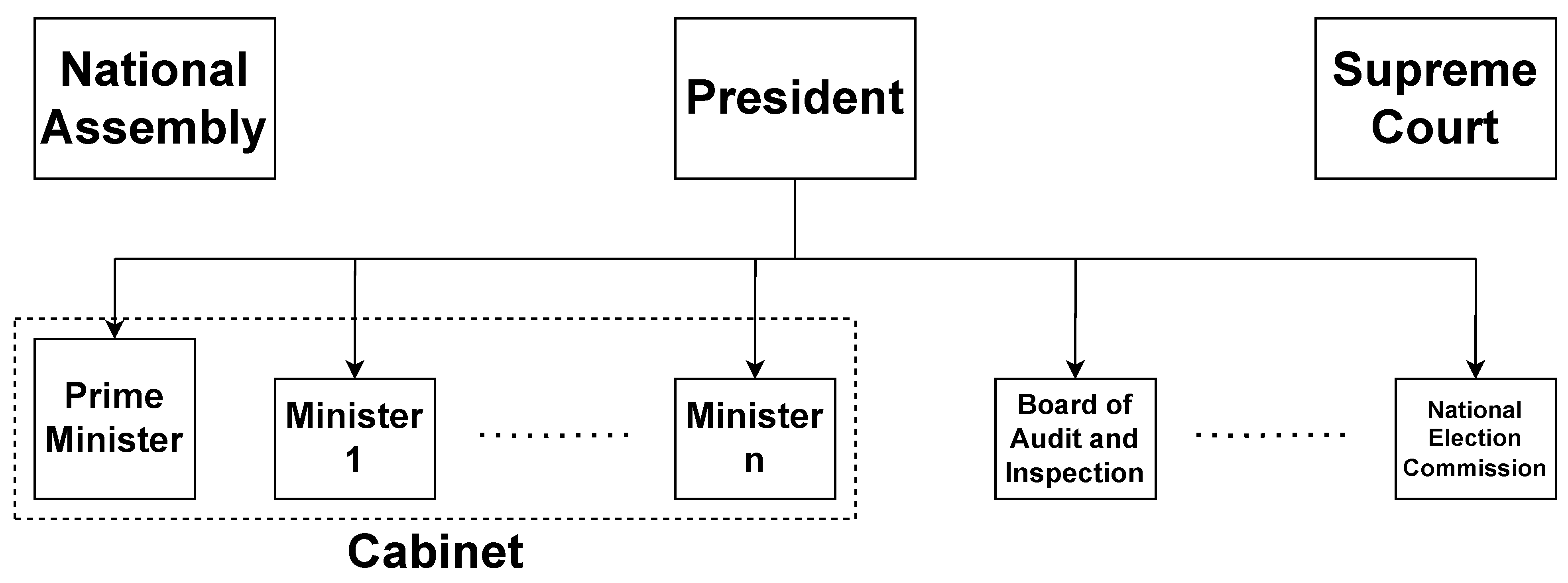

Korea is very special in that it is the only country in the world having the following properties:

The president is directly elected.

The parliament is directly elected and cannot be dissolved before its term expires.

There is a prime minister who is appointed by the president with approval from the parliament.

Unless convicted, the prime minister and other ministers can only be removed by the president.

The prime minister is the head of the cabinet, and the president appoints and dismisses other members of the cabinet (the ministers) based on the recommendations of the prime minister, without needing approval from the parliament.

Properties 1–4 are typical features of a presidential system, but Property 5 has a semi-presidential flavor. Overall, Korea is a presidential republic. In the sequel, we refer to a political system with Properties 1-5 as a Korea-like presidential system. Currently, there is only one Korea-like presidential system, which is Korea’s. But theoretically we cannot rule out other countries in the future may adopt a Korea-like presidential system.

Admittedly, Korea’s political system has essential properties not included in the above list. In other words, Korea is more than Korea-like. For example, Korea’s president has the power to dismiss the prime minister at will, but this was not mentioned above. This omission is intensional, as we will later propose modifications to the current Korean political system, and we want the modified system to remain Korea-like as defined above.

Now let us return to the discussion of prime ministerial appointment gridlocks. The framers of Korea’s current sixth republic constitution envisioned the prime minister’s appointment to resemble that of the U.S. Secretary of State, which is why they did not include provisions to address potential gridlocks in the appointment process. However, in terms of constitutional power, Korea’s prime minister is akin to the prime ministers of semi-presidential countries, and nearly all such countries have incorporated anti-gridlock provisions in their constitutions.

Historically, the political parties in Korea seemed to have respected the tradition formed during the authoritarian era, that is, the prime minister should be a subordinate to the president. Hence, each time a prime ministerial nomination was up for approval, even when the opposition controlled the National Assembly (Korea’s parliament), they ultimately gave up on obstructing the president’s nominee from being approved, who was always chosen from the president’s own camp. In other words, Korea’s political parties have been restrained in using their constitutional power. Therefore, although there were in history a few gridlocks (see table below), they did not erupt violently and were finally resolved through negotiations.

| Time |

President |

Nominee for Prime Minister |

Party Controlling the National Assembly |

| 1998 |

Kim Dae-jung (1998–2003) |

Kim Jong-pil |

Grand National Party (right wing) |

| 2007 |

Roh Moo-hyun (2003-2008) |

Kim Hwang-sik |

Grand National Party (right wing) |

| 2022 |

Yoon Suk-yeol (2022-) |

Han Duck-soo |

Democratic Party of Korea (left wing) |

However, things are going to have a change, and we may not be as fortunate as we were. Political polarization in Korea has intensified, and recent events (President Yoon Suk-yeol ordered martial law and was later impeached) have proven this point. Therefore, ad hoc, non-constitutional methods for resolving gridlocks may need to give way to systematic, constitutional ones.

3. The Game-Based Scheme for Prime Minister Approval

The French Approach for avoiding gridlocks is quite satisfactory per se, but if Korea were to adopt it, the whole constitution needs to be rewritten. A key fact is that the presidential system has been deeply rooted in the Korean culture, and a reform plan that would preserve the presidential system would be most likely to succeed. In this vein, the dissolution of parliament measure is not usable, and to be balanced, the parliament should not be granted the power to remove the prime minister with a simple majority; hence also to compensate it, the prior parliamentary approval should not be relinquished. Now in our arsenal we have two remaining weapons: parliament membership requirement and redesigning of the approval scheme. We discuss them one by one.

Parliament membership requirement: The advantages of this measure were discussed in the previous section. However, Korea has the tradition of choosing prime ministers from bureaucrats, such as past ministers, mayors, diplomats, etc., therefore restricting the choice to parliament members may be very controversial. So this measure will only be partially adopted in the scheme we describe later.

Redesigning of the approval scheme: Our current approval scheme is based on a false hypothesis: The parliament is unselfish; by going through the approval process they will help the president filter out candidates with poor character or insufficient ability, while also being happy to accept candidates who belong to the president’s camp. But the reality is: The parliament itself can be very partisan; what they care most is usually not the candidate’s character or abilities, but is the candidate’s political alignment. This is human nature, which we cannot resist. Therefore, we should redesign our approval scheme to respect and even leverage this nature, which means we must accept the candidate to be somewhat of a compromise between the president and the parliament. And when the opposition party holds a strong majority (two thirds, for instance) in the parliament, we must accept cohabitation.

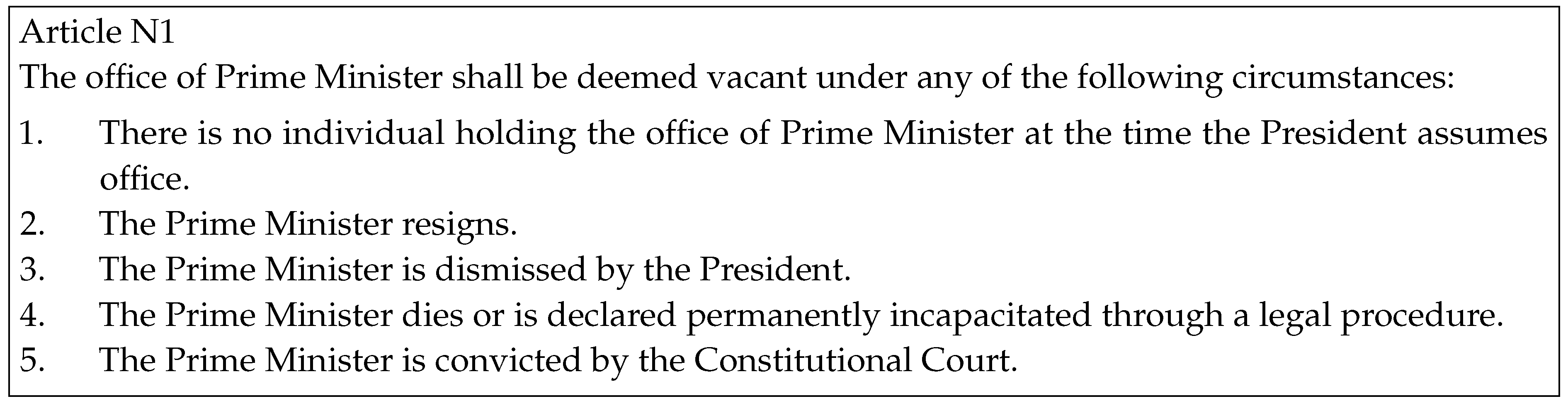

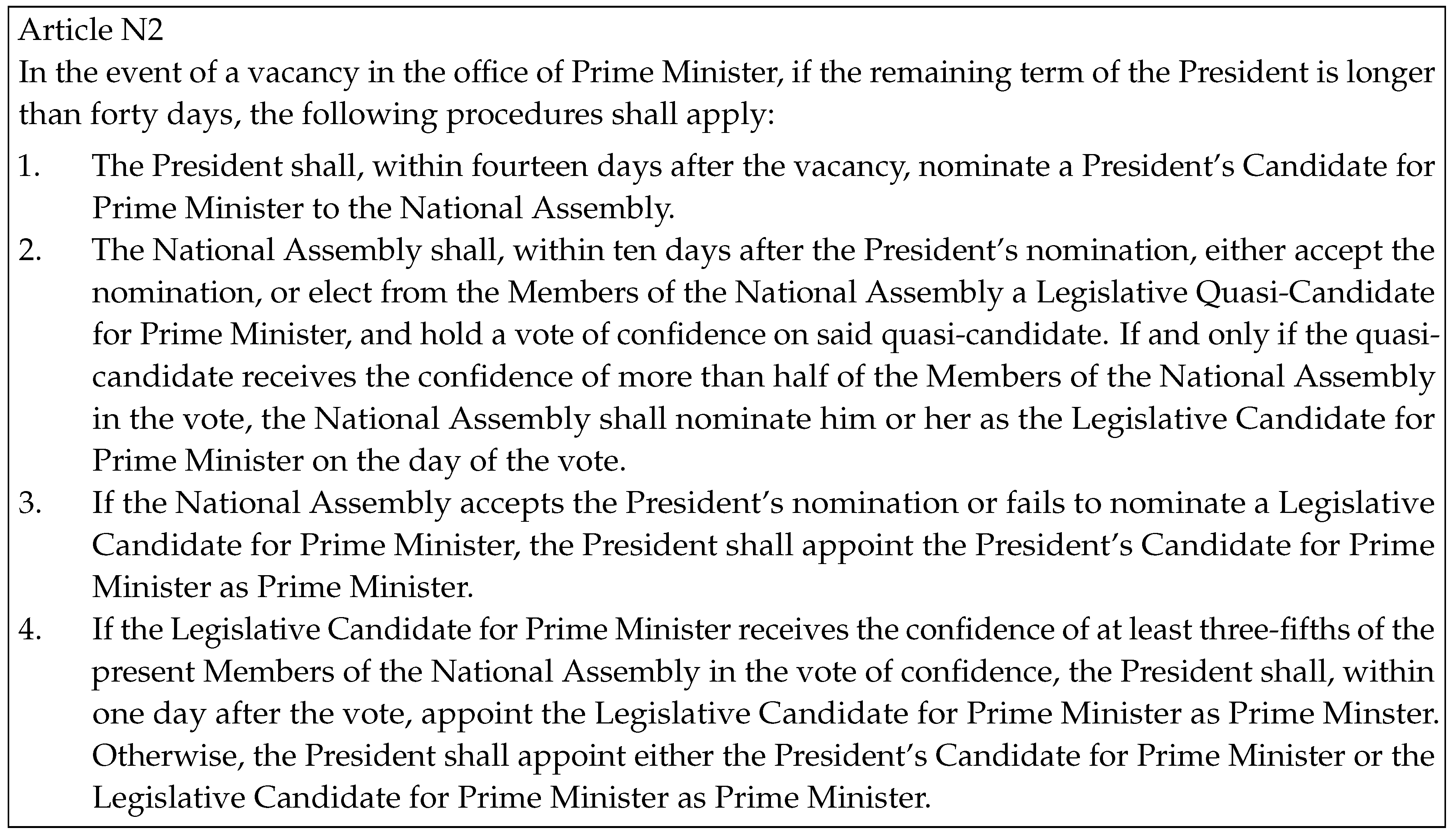

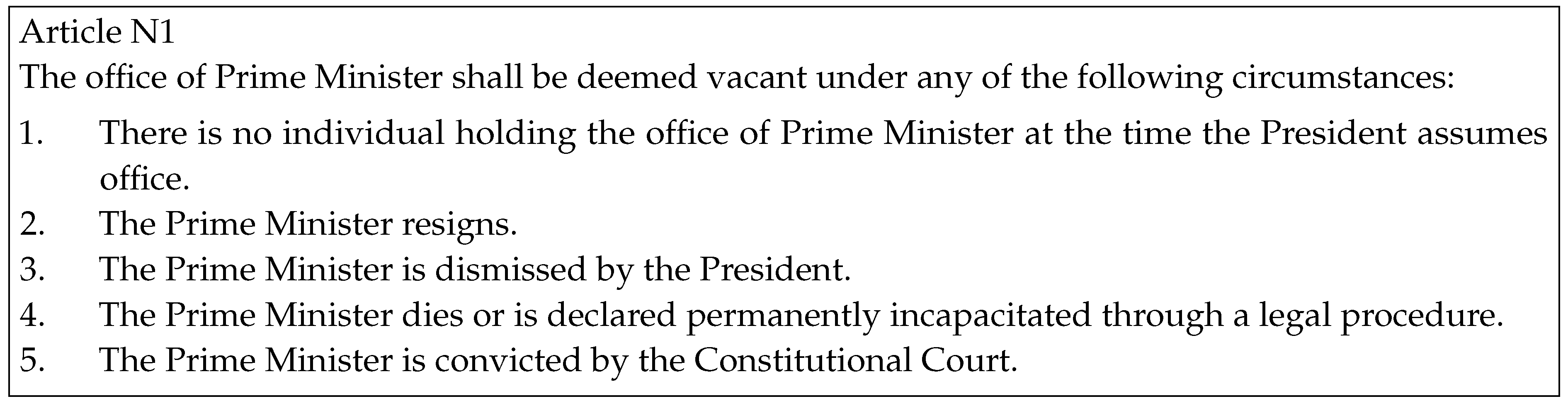

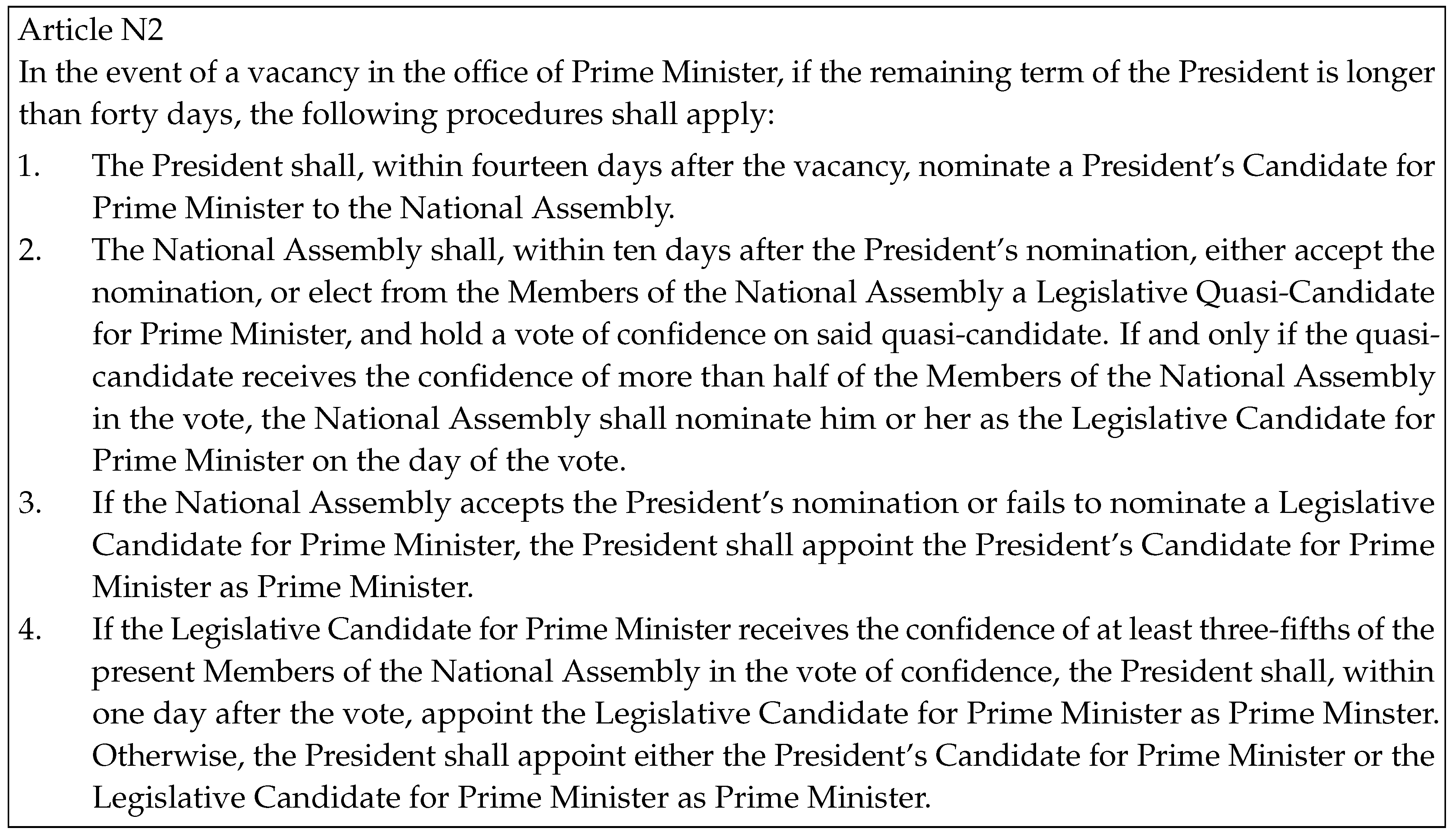

Now it is time to provide a detailed description of our redesigned scheme. It is presented in the form of simulated Korean constitution articles.

This scheme needs detailed explanations.

This scheme is competitive, or put differently, a game. The outcome is guaranteed within the specified time frame, with no possibility of delay. The current scheme, which is traditional approval, usually requires at least one side to make a concession. If neither side concedes, the process could be delayed indefinitely. The application of game theory in policy-making is explored in [

3]. However, to the best of the author’s knowledge, the use of game as a mechanism for selecting a prime minister has not yet been reported in the literature.

The 3/5 (present) threshold for cohabitation is higher than that of France, which is simple majority. This is reasonable given Korea’s presidential history and culture. Moreover, by definition, the cabinet is the president’s inner circle, and its responsibility is to assist the president in exercising executive power. This is another reason for allowing the president to have more say on the formation of the cabinet.

The 3/5 (present) threshold for cohabitation, which will be called cohabitation threshold in the sequel, is a crucial parameter of our scheme. Its value set here is only tentative, and can be adjusted if it is inappropriate. This parameter must be set within the (1/2, 1) interval, with two choices of the denominator when calculating the confidence ratio: all members or present members, and two choices from “more than” and “at least”. If the parameter is set near 1, then our scheme results in a ultra-presidential system; if the parameter is set very near 1/2, then our scheme results in a system resembling the French system.

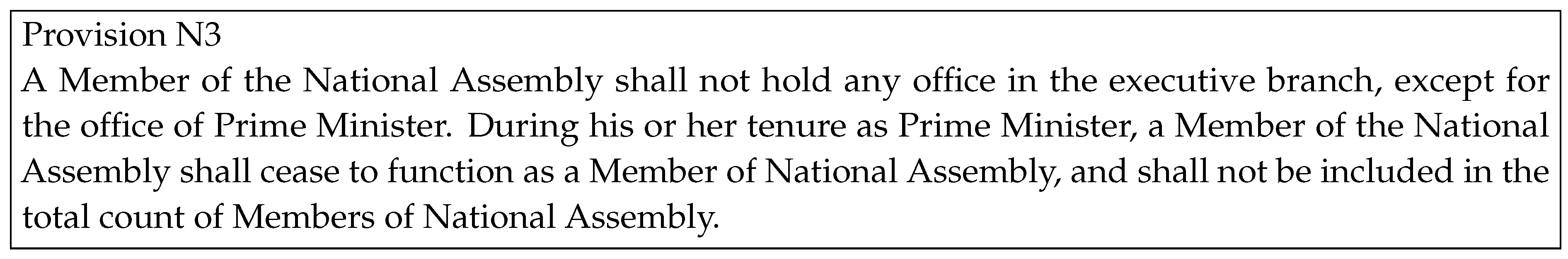

We partially adopted the parliament membership requirement. For the president’s candidate, it is not required, but the legislative candidate is required to be a parliament member. The legislative candidate particularly relies on support from the parliament, and by requiring this, the election is entirely within the parliament, making it much simpler and more efficient. Countries that adopt this requirement usually also stipulate that losing parliamentary membership means losing the position of prime minister. This we believe is unnecessary. Therefore in our scheme, parliament membership is required only when the legislative candidate is nominated.

It may seem odd that no vote on the president’s candidate is arranged in our game-based scheme. But actually there is. The confidence vote on the legislative quasi-candidate is actually a vote of comparison between the two candidates, because all the members of parliament know that one of the two must win the position. It is thus no wonder that we set the threshold for legislative candidate to simple parliamentary majority. If one becomes the legislative candidate, it means that the members of parliament believe they are a better choice than the president’s candidate. To implement Article N2, the parliament will pass a resolution (or law, but a resolution should suffice), and the resolution is expected to include arrangement of hearings for the president’s candidate and the candidates for legislative quasi-candidate, so that the members of parliament have a basis to rely on at the election.

The last sentence in Article N2 says that the president has two choices, but in fact we all know the president will definitely choose their own nominee. But we must write it this way, because otherwise, the president will be prohibited to appoint the legislative candidate, and that is absurd.

Why should the president provide their nomination first? Could we adopt the following rule: “First let the parliament elect and nominate a candidate. If the candidate meets the cohabitation threshold, then they must be appointed. Otherwise, the president can freely appoint someone.”? This latter rule would give the president a high probability of freely appointing the prime minister, because the probability that the parliament’s nominee will not meet the cohabitation threshold is rather high, and hence it is very dangerous. By requiring the president to provide their nomination first, to win the game, the president is pressured to nominate a person with moderate positions, good image and strong qualifications. If the president insists on a candidate who is only loyal to them but lacking good qualifications, they risk losing the position of prime minister to their opposing camp.

Which scheme makes it easier for the president to pass their nomination, the current scheme or the game-based scheme? Hard to tell. The current scheme is multi-round, and no one can force the president to nominate a person not in their camp, albeit with the price of gridlocks. Our game-based scheme is single-round. However, comparing the two schemes in terms of a single round, the parliament is harder to reject the president’s nomination with our scheme, because they now need to elect a very strong alternative candidate. This is very similar to the idea of “constructive vote of no-confidence” adopted in the German Basic Law. In fact, our scheme was inspired from that idea. By the way, some may ask: “Why not arrange a traditional vote of approval first; if not approved, then proceed to the election of the legislative candidate?” Our answer is yes. It is perfectly compliant with the game-based scheme, because the scheme described above does not stipulate how for the parliament to decide to accept the president’s nomination and how to elect their quasi-candidate, and a traditional approval vote is just an implementation of acceptation. However, that is not for their benefit. If the parliament does so, they will give the president extra chance of passing their nomination. Imagine the scenario: The president is left wing, and the parliament is composed of 35% left wing, 20% central wing, and 45% right wing. The central wing can cooperate with the left wing as well as the right wing. Now the president nominates a left wing candidate, then in the traditional approval vote, the left wing and the central wing vote for the candidate, and the nomination gets passed. But actually, if the traditional approval vote is not held, the right wing can ask for the help of the central wing, and they can pass the cohabitation threshold to win the position. By holding a traditional approval vote first, the parliament (which is right-leaning) loses a battle that they could have won.

Indeed, the very attributes of the current scheme that make it prone to gridlocks are also the ones that contribute to its two key advantages: avoiding hasty decisions through multiple rounds and ensuring acceptability by both sides. Thus, until better schemes are invented, the current scheme remains the most suitable for approving officials in neutral, independent agencies, while our game-based scheme is ideally suited for approving prime ministers. Compared with the current scheme, our scheme is more likely to yield a result that pleases only one side, and as a result, the prime minister is more likely to be politically polarized. But this is perfectly fine because cabinet members are allowed and even encouraged to be somewhat politically polarized. Moreover, in our defense, our game-based scheme is in fact also multi-round, only that the rounds are unofficial consultations between the involved parties. Furthermore, in the current scheme, there is no mechanism to quantify whether the demands or concessions of each party are reasonable or not, or to determine who should bear responsibility for gridlock if it occurs. A crafty president might even play this trick: They first nominate a candidate completely at their will, whom the parliament will almost certainly reject, then the president concedes gradually, ultimately making the parliament feel that they’ve rejected too many times and, fearing the responsibility of a gridlock, reluctantly approves the president’s nomination. An honest president would, for the first time, nominate a candidate who has been carefully compromised, but would instead face strict scrutiny from the parliament and fail to be approved. In short, the current scheme has the tendency to award crafty, tough parties, while punish honest, concessive ones. With our game-based scheme, all these problems disappear, and a crafty or tough president has no chance of gaining any advantage; on the contrary, they will be punished by losing the game.

Depending on the composition of the parliament, the president’s candidate could either be their ideal choice or a compromise candidate reached after consultations with other parties in the parliament. The 14-day period mentioned in Article N2 is reserved for such consultations. If the president nominates a compromise candidate, that nominee has a very high chance of being accepted. And a president who has made concessions is likely hoping to secure some assurances from their nominee. Therefore, this 14-day period can also be used for negotiations between the president and the nominee on power-sharing after taking office. Similarly, the 24(14+10)-day period allocated to the parliament is for intra-parliament bargaining, preliminary voting activities, and so on. If these time frames are not suitable, they can be adjusted.

This article does not stipulate that the two candidates must be different, because there is no need for that. The effect of having this rule is exactly the same as not having it.

Some may argue, “Why have such a complicated procedure? Why not simply allow the president to appoint a prime minister at will, as in France, and then allow the parliament to elect a prime minister through a `constructive vote of no-confidence’, as in Germany?”. But we doubt if this French-German scheme is practicable, because the prime minister appointed at will by the president would be afraid to take any big action, as they could be removed by the parliament at any time. However, if we stipulate that the removal by the parliament must occur within a certain time frame, wouldn’t that be exactly what we proposed?

We now use a different model of transition than in version 1. In version 1, we assumed the U.S. model of transition, where all cabinet members automatically vacate their positions when the president who appointed them leaves office, based on the mistaken belief that Korea follows the same practice. In this version, we adopt the transition model currently used in Korea and France, where cabinet members appointed by the outgoing president remain in their positions, legally recognized, until they are officially replaced by the new president. Therefore, we reworded the first item of Article N1 and removed Article N4 in version 1 entirely.

What happens if a vacancy in the office of the prime minister occurs while the parliament is not in session? Normally, the parliament should convene an urgent session to approve a nominee. However, if the vacancy occurs near the end of the parliament’s term, so that the parliament loses its authority midway through the nomination-approval process, then according to Article N2, the president may directly appoint their nominee due to the parliament’s failure to provide its nominee. Thus, Article N2 presents a potential flaw by allowing the president to avoid parliament’s involvement in the process of appointing the prime minister. This issue will be addressed with an additional provision.

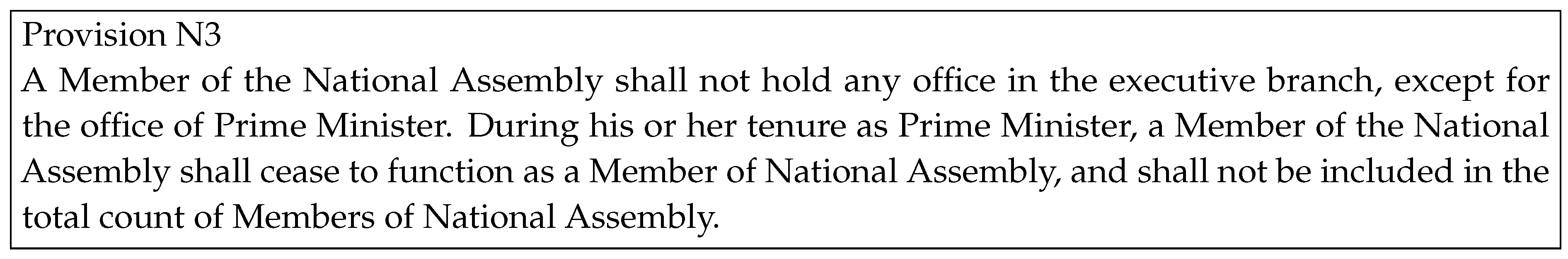

Now, if a parliament member becomes prime minister, shall they retain, suspend, or resign their parliament seat? The “resign” option is too risky for them, because they will permanently lose their parliament seat while they may only be prime minister for a short time. The “retain” option is a direct violation of the separation of powers principle set out in the constitution. So the only reasonable option is “suspend”. And then we have the following provision

3:

As for other ministers, there is no need to change the current practice, which is typical of a presidential system. In presidential systems, it is not encouraged to choose ministers from parliament members.

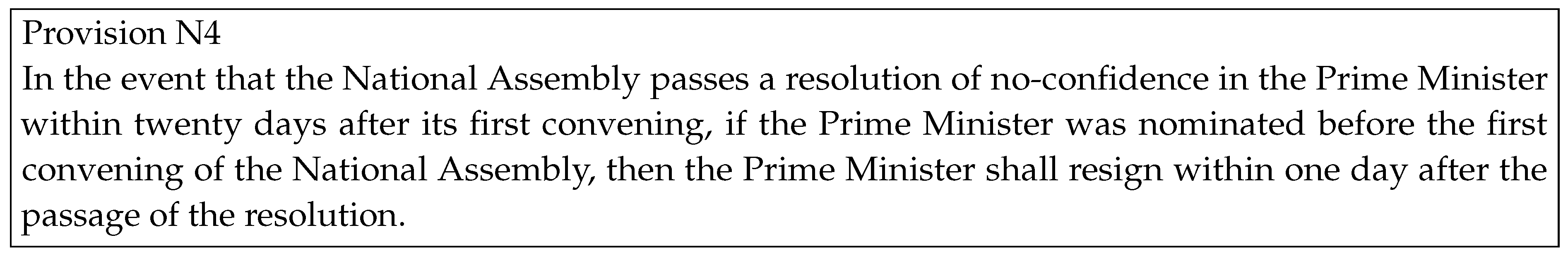

Articles N1 and N2 require additional provisions to address its unresolved issues, which we list below:

The potential flaw mentioned in the last item of the explanation of Article N2 should be resolved.

There should be a mechanism that allows public opinion to influence the composition of the cabinet following parliamentary elections. Version 1 is lacking in such a mechanism because parliament turnover does not necessarily coincide with a vacancy in the office of prime minister.

We need a vote of no-confidence article, which we omit here. The current Korean constitution already has a similar article, but it is not directly usable for our purpose. To suit our purpose, such an article should have the following elements:

Formally, the vote of no-confidence is in the prime minister, not in the cabinet or the government, although the two mean almost the same in effect.

A vote of no-confidence in the prime minister should be passed by a simple majority in parliament and formally take the form of a parliamentary resolution.

Such an article should not include any provisions on the consequences of a no-confidence resolution, which should appear elsewhere in the constitution. This stands in stark contrast to many existing constitutions, where articles on votes of no confidence directly specify that the prime minister must be removed from office.

We have some explanation for the provision.

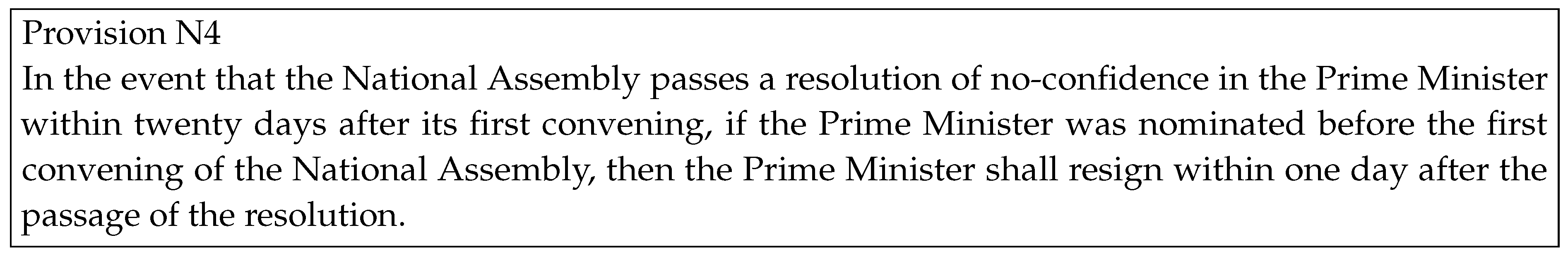

Provision N4 fixes the potential flaw mentioned earlier and introduces a mechanism that allows public opinion to influence the selection of the prime minister after a parliamentary election, as resignation of the prime minister triggers a competitive nomination-approval process. Let us note that with this provision, Property 4 described in

Section 2 is broken. So if our reform plan were adopted in its entirety, the political system will, strictly speaking, no longer be Korea-like as defined before. However, it is important to note that the time window for the parliament to pass a binding resolution of no-confidence is intentionally made very short, as we do not want the parliament to become the sword of Damocles for the prime minister. Furthermore, there is no legal prohibition against the president renominating the original prime minister after their resignation. Therefore, while our plan deviates from Property 4, the deviation is extremely minor.

Why not simply require the prime minister to resign when the parliament first convenes? If so required, a competitive nomination-approval process would inevitably follow. However, under Provision N4, there is a significant chance that such a process may not take place, because a motion of no-confidence may not be raised or may fail to pass within the time window. Provisions that are least damaging to cabinet stability should be preferred.

Why should the no-confidence resolution be binding only for a prime minister who “was nominated before the first convening of the parliament”? The reasoning is that if the prime minister was nominated after the current parliament had convened, the parliament would have already played a role in the appointment process. Moreover, the public opinion, as reflected in the composition of the parliament, has nothing to do with the prime minister, who took office only after the parliamentary election, and therefore, the prime minister should not be forced to resign in this situation. Practically speaking, the provision being written this way serves two purposes. First, theoretically speaking, the parliament may pass multiple no-confidence resolutions within the time window, and our provision ensures that only the first such resolution can be binding. Second, the president may also intend to replace the prime minister; if the provision were not written this way, they would have to wait for the time window to expire before taking relevant actions, fearing that the new prime minister could be forced to resign by a no-confidence resolution passed during the time window.

Why the phrase “nominated before”, instead of “appointed before”? This is purely for the sake of rigor, and is closely related with the flaw mentioned earlier. Recall the scenario described earlier: The prime minister was nominated near the end of the outgoing parliament’s term. Now assume that the gap between the old and new parliament sessions was short, and the president delayed the appointment until the new session began. If the phrase “appointed before” were used, the prime minister could circumvent the binding effect of the new parliament’s no-confidence resolution.

If the parliament is elected simultaneously with the president, Provision N4 is not so essential for the parliament, because the president normally will want to have a new prime minister, and the parliament would then be involved in selecting the new prime minister. Provision N4 is essential for a parliament elected midway through the president’s term, as without it, the parliament would have no means to replace the prime minister unless a vacancy occurs.

4. Supporting Provisions of the Game-Based Scheme

4.1. Provisions for Cabinet Stability

Cabinet stability has never been an issue in the sixth republic of Korea, and we need to take care to ensure that this advantage is not lost after our reform proposal is adopted. The stability of the cabinet is essentially equivalent to the stability of the prime minister. Below, we will go through the various possibilities in which the prime minister might step down.

Possibilities that the prime minister wants to resign: If the prime minister wants to resign because they feel their performance is poor or because of public opposition, it is normally not for institutional reasons. Otherwise, the prime minister’s desire to resign is generally due to a poor relationship with the president. There may be institutional reasons for it and the next subsection contains a relevant discussion about it.

Possibilities that the prime minister steps down involuntarily:

The president feels that the prime minister’s performance is poor, or there is public opposition against the prime minister or even the president, and in the latter case, the president wants to save themselves by throwing the prime minister under the bus. However, none of these are related to our new approval scheme, therefore we will not discuss them further.

The president finds it difficult to get along with the prime minister and wants to dismiss them. There may also be institutional reasons for it and the next subsection contains a relevant discussion about it.

The president’s party gained considerably more seats in a recent parliamentary election and the president wants to replace the prime minister with someone who is closer to them. Or the prime minister’s opposition party gained considerably more seats in a recent parliamentary election and the opposition wants to replace the prime minister with someone from their camp by raising a motion of no-confidence. These are both normal political operations and should not be discouraged at the legal level.

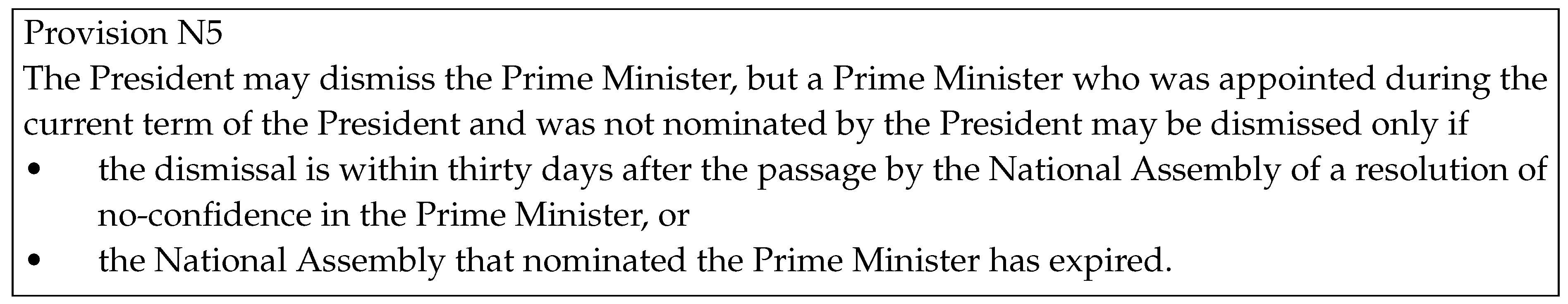

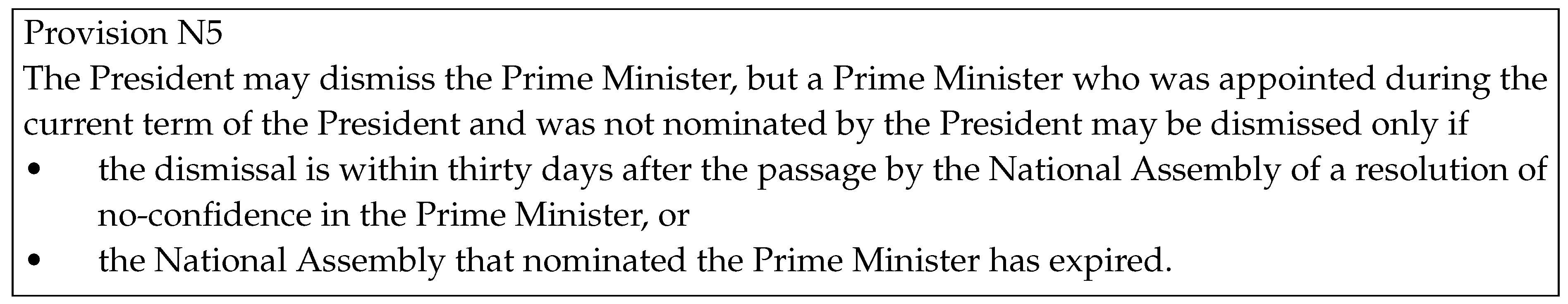

The president thinks they made a bad decision in the nomination-approval process and got a prime minister they are dissatisfied with (who must be a legislative candidate). They want to dismiss the prime minister and go through the process again. This is typically a reckless action that wastes state resources and causes unnecessary cabinet instability, and therefore, it should be discouraged. So we have the following provision.

In version 1 of this paper, we used the phrase “the National Assembly consents to the dismissal”. The current wording is considered far better, although the essence is kept unchanged. With this provision, such a dismissal is highly unlikely, if not impossible, as the parliament is currently controlled by the opposition and is therefore unlikely to agree to the dismissal. Normally, the president has to wait until the next parliamentary election to replace the prime minister. However, if they want, the president can easily retain the power to dismiss the prime minister at will by nominating the leader of the parliamentary majority when the president’s party holds only a small minority in parliament. The limitation is that, after the dismissal, the president can virtually do nothing – they still cannot appoint their preferred candidate.

It is also important to note that under this provision, the president has the authority to dismiss a prime minister appointed by a previous president or by themselves in a prior term (in case of reelection, though reelection is currently prohibited in Korea), regardless of who nominated the prime minister. Note that a prime minister can be appointed by a past president but nominated by the current parliament. Ultimately, it is because the president holds this power that the prime minister typically resigns on the day a new president takes office, unless the new president explicitly wishes to retain the prime minister.

With Provision N5, it is inaccurate to say that the president can dismiss the prime minister at will, and that is why we stated Property 4 in

Section 2 that way.

There is also a practice worth mentioning, which is “fake resignation, actual dismissal”. The president can, before nomination or appointment, request a candidate for prime minister to submit a resignation letter without a date. Then, at any time during the prime minister’s term, the president can announce the prime minister’s resignation, even though the prime minister does not actually wish to resign. In reality, this is effectively a dismissal. This practice is recognized in the constitutional practices of various countries. In our game-based scheme with Provision N5, there are two cases that this practice can be used:

A President’s Candidate for Prime Minister may be requested for a resignation letter before their nomination, or later but before appointment, if there is a Legislative Candidate for Prime Minister who only fails to pass the cohabitation threshold, in which case the president has two choices. However, the president does not need to do so, because in this case the prime minister is nominated by the president, and the president can dismiss the prime minister at will.

A Legislative Candidate for Prime Minister who only fails to pass the cohabitation threshold may be requested for a resignation letter, because it is possible for the president to appoint them. In this case, the president genuinely needs this letter, as it allows the president to circumvent constitutional restrictions (see Provision N5).

A Legislative Candidate for Prime Minister who passes the cohabitation threshold is mandatorily to be appointed as prime minister. Therefore, the candidate will almost certainly refuse any such request, if it exists, therefore typically, the president will not make such a request to them.

Finally, it is believed that cabinet stability after adopting our game-based scheme with Provision N5 will be quite good. A fundamental fact is that, apart from prime minister removal due to misgovernment, in a president’s term, who will be prime minister is largely determined by the political composition of the parliament, therefore, both sides can only expect to gain an advantage from replacing the prime minister immediately following a parliamentary election, and as a result, the cabinet is expected to remain stable between parliamentary elections. To ensure that presidential and parliamentary elections are evenly distributed over time, an election system with fixed election dates and midterm elections is essential. Such a reform plan was recently proposed for Korea in [

4].

4.2. Provisions for Cohabitation

When the nomination-approval process is finished, the result can be one of the following:

Non-cohabitation: The prime minister and the president belong to the same party, so of course, the prime minister is nominated by the president.

Soft cohabitation: The prime minister and the president do not belong to the same party, but the prime minister is nominated by the president.

Hard cohabitation: The prime minister is not nominated by the president.

The term “hard cohabitation” has already appeared in the literature, for example, in [

5]. In existing studies, it typically refers to a situation characterized by significant conflict or tension between the president and the prime minister. Clearly, the term is used with a different meaning in this paper. We initially sought to avoid terminological conflicts but were unable to find a better term to convey our intended meaning. As a result, we have no choice but to retain “hard cohabitation”. Another reason for this choice is that the situation we define as “hard cohabitation” often coincides with the scenario described by the term in the existing literature.

Earlier, we used the term “cohabitation”, but it actually means “hard cohabitation” here. The distinction between hard cohabitation and the other two terms is legal in nature, whereas the difference between soft cohabitation and non-cohabitation is mere political.

In Korea, there have been cases exclusively of non-cohabitation. In France, there have been cases of non-cohabitation and soft cohabitation. Hard cohabitation (as defined in this paper) is the artifact of our game-based scheme, and has never appeared in human history so far.

In [

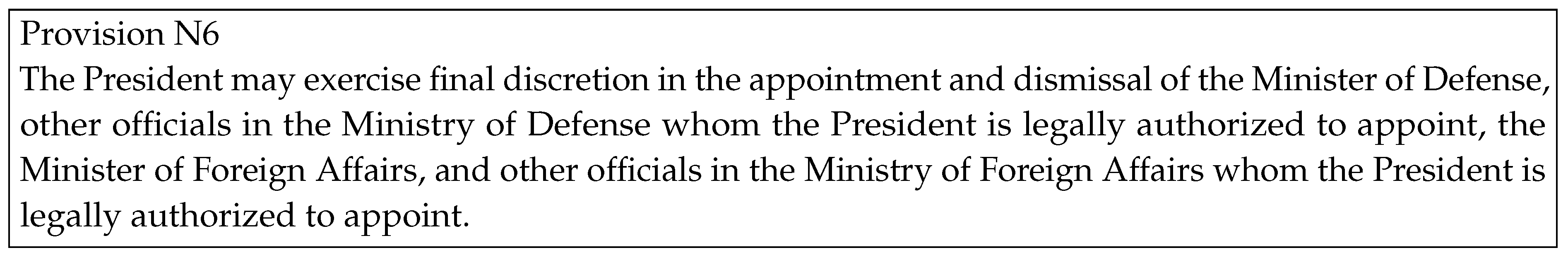

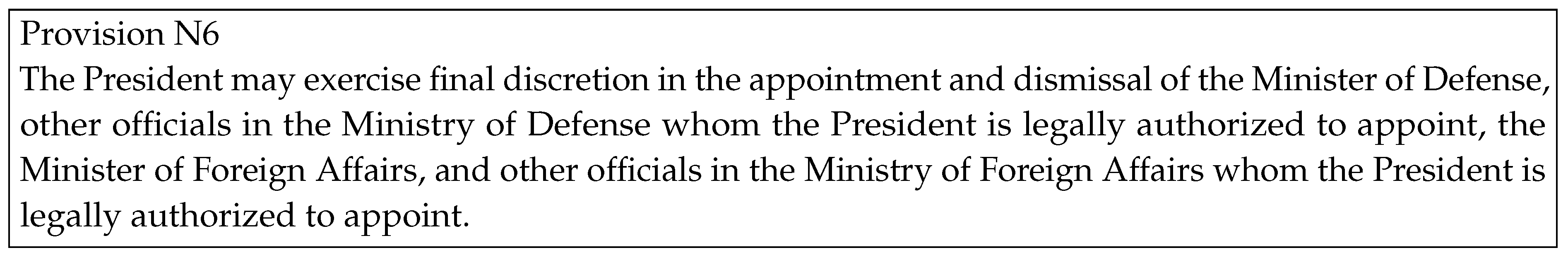

6], analysis is provided about the dynamics of semi-presidential systems and presidential systems, with a focus on the relationship between presidents and prime ministers. In this paper, we will look at the issue with a different perspective. The constitution leaves a significant grey area regarding the distribution of powers between the president and the prime minister. The appointment and dismissal of every cabinet member and government official require the president and the prime minister to consult and reach a common decision. However, if both use their constitutional powers to the fullest, a deadlock occurs when their opinions differ. In the case of non-cohabitation, since the president is superior to the prime minister within their party, the president’s opinion often prevails, thus avoiding a deadlock. In the case of soft cohabitation, the relationship between the president and the prime minister is like that of a “mentor” and “disciple”. Additionally, since they usually have a power-sharing agreement reached before the nomination, a deadlock generally does not occur. The issue is severest in the case of hard cohabitation. The two may refuse to cooperate, leading to a more frequent deadlock. This issue needs to be addressed, and we suggest to amend the constitution to include a provision as follows.

The purpose of this provision is that, in the absence of a power-sharing agreement, the president and the prime minister can each govern their respective domains with minimal interference from one another. This arrangement for cohabitation, where the president is in charge of defense and foreign affairs, while the prime minister is responsible for domestic affairs, has been in place in France for decades, but in France, it remains a constitutional convention and has not yet been codified. France can use it as a constitutional convention because, in France, the prime minister is always nominated by the president, and there exists a power-sharing agreement — whether explicit or tacit — between them. But this is not the case with hard cohabitation, because there the prime minister is not nominated by the president. However, this provision does not forbid the president and the prime minister from reaching a power-sharing agreement later during their cohabitation. A power granted by the law does not have to be fully exercised; it is permissible to exercise a power with restraint in exchange for the other party’s commitment. Therefore, if there is a power-sharing agreement between the two, the president may intervene in domestic affairs, while the prime minister may take on responsibilities in defense and foreign affairs, even in a situation of hard cohabitation.

Symmetrically, could we stipulate that the prime minister hold some decision-making power in domestic affairs? This is probably not a good idea. First, the president holds a higher ceremonial status than the prime minister, and such a provision could be seen as disrespectful to the president. Second, the constitution already grants the prime minister significant authority: in domestic matters, the prime minister’s recommendations regarding the appointment and dismissal of ministers are legally binding. Third, introducing such a provision would create an overly rigid division of powers between the president and the prime minister, hindering their communication and potentially worsening their relationship. Then, is it appropriate to have such a provision specifically for hard cohabitation? Still no. In hard cohabitation, with Provision N5, the president has virtually no power to dismiss the prime minister, leaving them with no choice but to accept the prime minister’s control over domestic affairs, unless they have a power-sharing agreement. Therefore, such a provision would be unnecessary.

5. Conclusions

We addressed the issue of gridlocks in the approval of prime ministers in semi-presidential countries and presidential countries with prime ministers. After analyzing prime ministerial appointment gridlocks in South Korea, we explored potential measures to resolve them. In light of South Korea’s presidential culture, we proposed a game-based scheme for prime minister approval, specifically designed for presidential systems like Korea’s. Our proposed constitutional reform incorporates this game-based approval scheme (comprising three articles and two provisions) alongside two supporting provisions, requiring only minimal revisions to the existing constitution.

This scheme has two salient features. First, it is actually not a single scheme, but rather a family of schemes. It has a parameter that can be adjusted, enabling the political system to gradually transition from a French-style semi-presidential system to an ultra-presidential system. We have tentatively set the value of this parameter at 3/5, which is considered balanced, though whether it is truly balanced awaits testing in future practice. Second, the scheme introduces a new form of cohabitation: hard cohabitation, in which the prime minister is not nominated by the president. Hard cohabitation will likely bring about two new challenges: potential cabinet instability and difficulties in cooperation between the president and the prime minister. And the two supporting provisions are specifically designed to address these challenges.

This is version 3 of the proposal. Beginning with version 2, a transition model which is truly used in South Korea is adopted. Also, thanks to this model change, we successfully resolved several issues identified in version 1. Additionally, a newly added provision also introduces a mechanism allowing the parliament to possibly replace the prime minister following a parliamentary election. Compared with version 2, the provisions in version 3 are more concise, elegant, and rigorous. As a result, this version is significantly more polished.

Overall, we believe that, if implemented, this reform will effectively eliminate gridlocks, ensure fairness for all parties, maintain cabinet stability, and preserve a balanced distribution of power between the president and the prime minister. We strongly hope that this reform will eventually be adopted by South Korea or other countries with similar presidential systems.

References

- Elgie, R. The role of the president in semi-presidential systems: The case of France. European Journal of Political Research 1999, 35, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelizzo, R.; Stojanović, J. The politics of prime ministerial appointment: A comparative analysis of parliamentary, semi-presidential, and presidential systems. Government and Opposition 2015, 50, 345–373. [Google Scholar]

- Hine, D. Game theory in political decision-making: The case of constitutional reforms. Journal of Political Science 2020, 48, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y. Importance of midterm elections and how to introduce them in Korea, 2024. Online. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387217738_Importance_of_Midterm_Elections_and_How_to_Introduce_Them_in_Korea.

- von Metternich, M. The challenges of hard cohabitation in semi-presidential systems. Political Studies Review 2015, 13, 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Shugart, M.S.; Carey, J.M. Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics; Cambridge University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

Date of survey: 25-Dec-2024 |

| 2 |

In the body of this paper, we use “Korea” to refer to South Korea, that is, the Republic of Korea. |

| 3 |

This rule is designated as a provision and intended to be included within an article, because it is considered not sufficiently broad or self-contained to constitute an independent article. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).