1. Introduction

Stem cell-based therapies, especially mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation, are novel strategies in regenerative medicine. MSC implantation for bone regeneration is applied clinically based on the finding that MSCs from multiple tissues promote bone regeneration [

1,

2,

3]. Although this approach is valuable in regenerative medicine, some issues (such as tumorigenesis [

4], poor survival rate of implanted cells [

5,

6], and transmission of infectious diseases) remain to be resolved.

Conditioned media from human bone marrow-derived MSCs (MSC-CM) contain numerous factors that promote bone regeneration. Insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF), and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) in MSC-CMs promote cell migration, angiogenesis, and cell differentiation; they accelerate bone regeneration [

7,

8,

9]. Recent studies have reported that MSC-CM elicit macrophage phenotype switching and contribute to the establishment of an anti-inflammatory milieu during the early phases of bone regeneration [

10]. Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying MSC-CM-induced bone regeneration will contribute to the development of cell-free regenerative medicine.

Macrophages are activated by diverse stimuli and categorized into two major subtypes according to their functions. Classically activated M1 macrophages produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, whereas alternatively activated M2 macrophages release anti-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors. Recent studies have revealed that MSC-CM affect macrophage activation and subsequently create an anti-inflammatory milieu that promotes tissue regeneration [

11,

12,

13]. We recently reported that MSC-CM promote phenotype switching towards M2 macrophages during the early phase of bone regeneration in a rat calvarial bone defect model [

10]. Furthermore, a previous study showed that monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, suggested to be one of the factors that promote macrophage phenotype switching, is present in MSC-CM by cytokine antibody array analysis [

14]. However, the direct contribution of M2 macrophages to the MSC-CM-induced early osteogenesis remains unclear.

In the present study, we investigated the role of MCP-1 in MSC-CM-induced bone regeneration using a rat calvarial bone defect model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Conditioned Medium

Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were purchased from Lonza inc. (Walkersville, MD, USA) and cultured at 37℃ in 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Ma, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Biowest, Nuaillé, France). The cells were then subcultured to the third to fifth passage and used in the experiment.

hMSCs at 80% confluence were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cultured in serum-free DMEM [DMEM(-)]. After being incubated for 48 hours, the medium was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter sterilizer and stored at 4 or -80℃ until use.

2.2. MCP-1 Depletion from MSC-CM

MCP-1 was depleted from the MSC-CM using rabbit anti-human polyclonal antibodies against MCP-1 (ab9669; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Briefly, Protein G magnetic beads (SureBeads Protein G; Bio-Rad, USA), pre-bound with 100 ng/mL anti-MCP-1 antibodies, were added to MSC-CM and mixed gently at 4℃ for 1 h. Antibody beads were magnetized, and the supernatant was collected. MCP-1 depletion was confirmed using MCP-1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (DCP00; R&D, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Depleted MSC-CMs were defined as depMSC-CM and used in subsequent experiments.

2.3. Bone Marrow Macrophage Isolation and Activation

Bone marrow cells were isolated from the femurs of 8-week-old male Wistar rats (Japan SLC, Shizuoka, Japan) and plated on 60-mm cell culture dishes or cover slips. They were differentiated into bone marrow macrophages (BMMs) in DMEM supplemented with 20 ng/mL macrophage colony stimulating factor (Peprotech, NJ, USA) at 37℃ in 5% CO2 for 7 days and used in subsequent experiments.

2.4. Immunocytochemical Analysis

The cells were fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde Phosphate Buffer Solution (PFA), Fetal bovine serum (FBS)

(Sigma-Aldrich), permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), blocked in 5% goat serum, and incubated with primary antibodies against CD11b (1:1000; Ab1211, Abcam), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (1:100; Ab15323, Abcam), and CD206 (1:10000; ab64693, Abcam). Next, secondary antibodies, AF647-conjugated anti rabbit (1:1000; Ab150079, Abcam), AF488-conjugated anti mouse (1:1000; Ab150113, Abcam) were used and cells were counterstained with DAPI (D9542, Sigma Aldrich). Samples were observed using a fluorescence microscope (Axioplan 2; Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.5. Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

hMSCs and BMMs were cultured with MSC-CMs, depMSC-CM, or DMEM(-) for 48 h, and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen N. V., Venlo, Netherlands) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. qRT-PCR was performed using TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa Bio) in combination with a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System III (TaKaRa Bio). The sequences of specific primers of markers for M1 macrophages (

iNOS and

CD80), markers of M2 macrophages [

CD206 and Arginase-1 (

Arg-1)], and osteogenesis-related genes [osteopontin (

OPN), type I collagen (

COLⅠ), alkaline phosphate (

ALP), and osteocalcin (

OCN)] are listed in

Table 1. The obtained results were normalized to Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (

GAPDH) and the 2-ΔΔCt method was used to calculate relative expression levels.

2.6. Rat Calvarial Bone Defect Model

All animal experiments were performed in strict accordance with the protocols reviewed by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Niigata University (No. SA00456).

10-week-old male Wistar rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of medetomidine, midazolam, and butorphanol. After shaving the parietal region, a transverse incision was made posterior to the eyes, and a longitudinal incision was made at the left ear base. The periosteum was raised to expose the calvarial bones. Two calvarial bone defects, 5 mm in diameter, were created using a trephine bur (Dentech, Tokyo, Japan) and rinsed with PBS to remove bone debris. MSC-CM (30 μl), depMSC-CM (30 μL), or DMEM(-) (30 μL) were implanted to the bone defect using atelocollagen sponges (Terudermis1, Olympus Terumo Bio-materials Corp., Tokyo, Japan) as a scaffold. Finally, the periosteum and skin were sutured using a 4-0 nylon thread. The rats were sacrificed at 72 h, 1 week, and 2 weeks after implantation, and the specimens were harvested.

The rats were randomly divided into four groups (n = 6 in each group) and the experimental groups were as follows: MSC-CM group, depMSC-CM group, DMEM(-) group, or defect group (defect only).

2.7. Microcomputed Tomography (Micro-CT) Analysis

Samples from all groups were harvested at 72 h, 1 week, and 2 weeks after surgery and analyzed using a micro-CT system (CosmoScan Gx, Rigaku Co., Tokyo, Japan). The specimens were observed by micro-CT, and three-dimensional (3D) images were reconstructed using Analyze software (version 12.0; AnalyzeDirect Inc., KS, USA). The newly formed bone area was evaluated as a percentage of surgically created bone defects.

2.8. Histological Analysis

Samples from all groups were harvested at 72 h, 1 week, or 2 weeks after implantation. The samples were fixed in 10% neutral formalin and decalcified with 10% EDTA (pH 7.4) for four weeks. Samples were dehydrated with graded ethanol, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 3 μm thickness in the coronal plane using a microtome (REM-710, YAMATO KOHKI Industrial Co., Ltd., Saitama, Japan). The sections were rehydrated, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and analyzed under a light microscope (FX630, OLYMPUS Co., Tokyo, Japan).

2.9. Immunohistochemical Analysis

Immunohistochemical staining was performed for iNOS (1:100; Ab15323, Abcam) to evaluate M1 macrophages and staining for CD206 (1:10000; ab64693, Abcam) to detect M2 macrophages. The sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, and antigen retrieval was performed with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 minutes at 121˚C. The sections were then incubated with 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. After washing with PBS, the sections were blocked for non-specific binding using 10% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4˚C. Subsequently, the sections were reacted with EnVision Plus (Dako, CA, USA) for 1 h and developed with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution. Finally, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin after DAB staining.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between groups were compared using Tukey’s honestly significant difference test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Since the bone-regenerative effect of MSC-CM was first reported, numerous studies have attempted to elucidate the underlying mechanism of its therapeutic effects. To date, several cytokines in MSC-CM and their effects on bone regeneration have been revealed. Osugi et al. have previously reported that VEGF, IGF-1, and TGF-β – contained in MSC-CMs – promote bone regeneration through cell proliferation, cell recruitment, and angiogenesis [

7]. Katagiri et al. have identified VEGF as a key factor in tissue regeneration that enhances capillary formation, thus supporting cell migration and blood supply to damaged tissues [

9,

15]. Moreover, Takeuchi et al. revealed that exosomes in MSC-CM promote bone regeneration by enhancing angiogenesis [

16]. Recently, the immune regulatory effects of MSC-CMs through macrophage phenotype switching and subsequent anti-inflammatory effects have been reported by several studies [

11,

12]. In this study, we aimed to identify the macrophage phenotype-switching factor in MSC-CM and its effect on bone regeneration.

Macrophages are activated by two major pathways–classical and alternative–and perform a wide range of functions [

13]. Classically activated macrophages (also known as pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages) are induced by microbial products, T cell-derived signals, and foreign substances. They actively ingest and produce cytokines that stimulate inflammation, thereby playing an essential role in host defense against chronic inflammatory diseases. Alternatively, M2 macrophages are activated by interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 produced by T and mast cells. These macrophages produce TGF-β and other growth factors to terminate inflammation and enter the tissue regenerative phase [

11,

17,

18]. Therefore, macrophage phenotype switching is the principal process for resolving inflammation and initiating tissue regeneration.

MCP-1 is a chemokine that promotes the chemotaxis of immune cells and plays a crucial role in inflammation and pathological circumstances [

19]. Recently, the ability of MCP-1 to convert the macrophage phenotype towards the M2 phenotype has been reported. Hernan et al. reported that MCP-1 promotes macrophage phenotype switching towards the M2 type through inhibition of apoptosis and caspase 8 cleavage [

20]. In this study, we confirmed that the MSC-CM contained MCP-1 at a concentration of 414.9 ± 138.2 pg/mL. Therefore, we hypothesized that MCP-1 plays a central role in MSC-CM-induced macrophage phenotypic switching.

MSC-CM-induced immunoregulatory effects and subsequent tissue regeneration are closely associated with macrophage phenotype switching. Gao et al. reported that MSC-CMs reduced the expression level of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α but enhanced the expression levels of IL-10, arginase-1, and CD206 in mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells. In addition, MSC-CM activated signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 but inhibited nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathways in RAW264.7 cells [

21]. Our previous report revealed that MSC-CM enhanced macrophage phenotype switching within 72 h after MSC-CM implantation and promoted bone regeneration in rat calvarial bone defects [

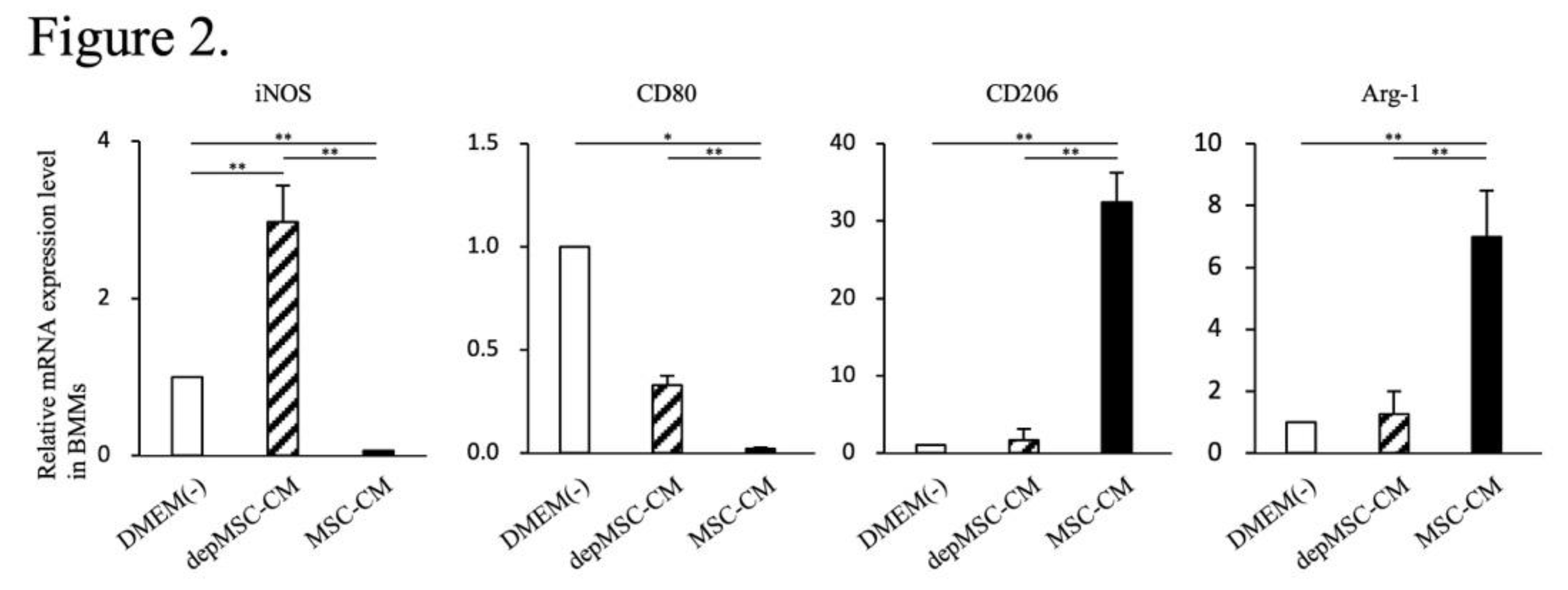

10]. In this study, using BMMs in vitro, we revealed that the expression levels of M2 macrophage markers (

CD206 and

Arg-1) were significantly upregulated – whereas the expression levels of M1 macrophage markers (

iNOS and

CD80) were significantly downregulated – in the MSC-CM group compared to those in the depMSC-CM group (

Figure 2) Therefore, MCP-1 in MSC-CM is likely to induce macrophage phenotype switching towards the M2 type. In addition, MSC-CM increased the number of M2 macrophages around the bone edge 72 h after MSC-CM implantation compared to the depMSC-CM group in vivo. Interestingly, the number of M1 macrophage in the MSC-CM group was significantly smaller compared to that in the depMSC-CM group. On the other hand, no significant difference was found in the number of M2 macrophage 1 and 2 weeks after implantation. These results suggest that MSC-CM promote macrophage phenotype switching towards the M2 type within 72 h after implantation; however, this effect is limited to the early phase of bone regeneration.

The interaction between MSCs and M2 macrophages is a key component in bone regeneration. Gong et al. previously reported that M2 macrophages accelerate MSCs differentiation into osteoblasts by releasing pro-regenerative cytokines (such as TGF-β, VEGF, and IGF-1), whereas M1 macrophages suppress osteoblast cell differentiation by producing pro-inflammatory cytokines (including IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α) [

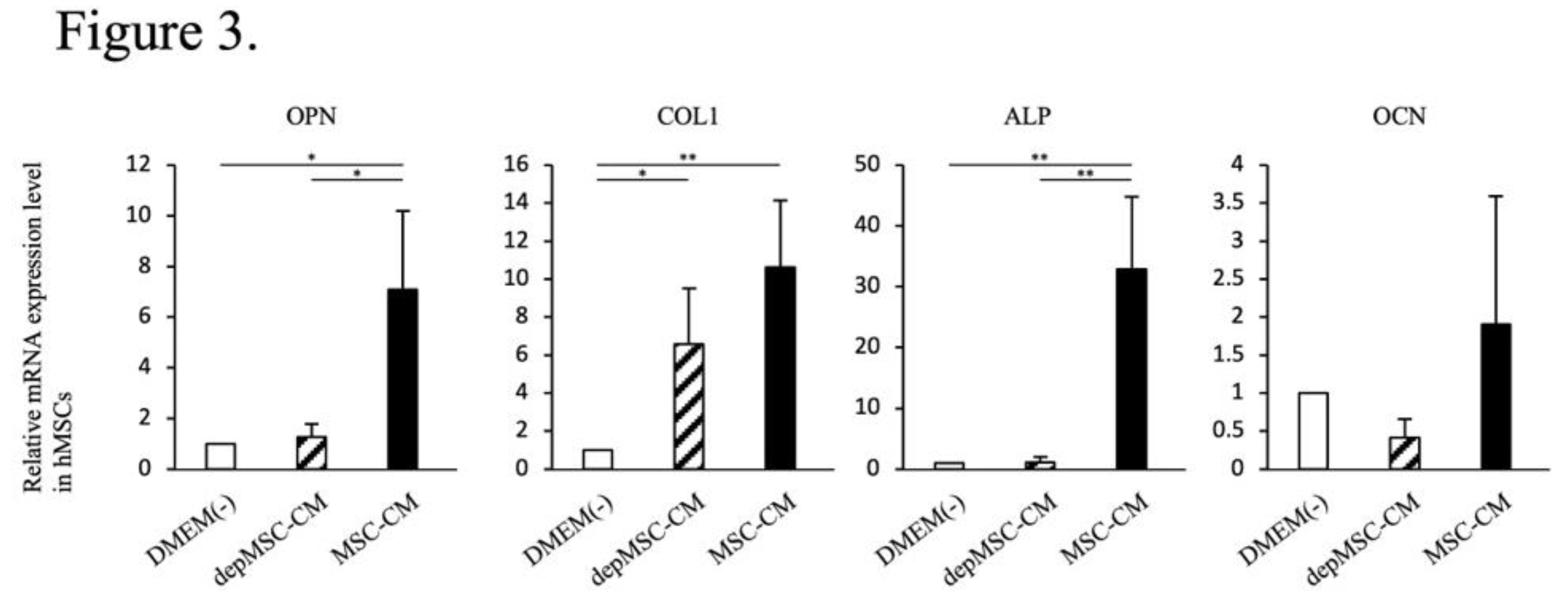

22]. In our study, MSC-CM enhanced osteogenesis-related gene expression in MSCs. However, the expression levels of

OPN and

ALP was significantly downregulated in the depMSC-CM group compared to those in the MSC-CM group in vitro (

Figure 3). These results suggest that MCP-1 in MSC-CM contributes to MSC osteogenesis. In a rat calvarial defect model, MSC-CM increased the number of M2 macrophages around the bone edge 72 h after implantation and maintained a high M2/M1 ratio for 2 weeks, resulting in enhanced bone regeneration. In contrast, depMSC-CM did not increase the M2/M1 ratio and subsequent bone regeneration was not obvious (Figs. 4-8). Overall, these results indicate that MSC-CM promote bone regeneration not only via a direct effect on MSCs themselves but also via MCP-1-induced macrophage phenotype switching towards the M2 type within 72 h after implantation.

MSC-CM contain numerous cytokines, some of which have been addressed in our previous studies to elucidate the underlying mechanism of bone regeneration induced by MSC-CM. In this study, we demonstrate the positive effects of MCP-1 on macrophage phenotypic switching and subsequent bone regeneration. However, the precise mechanism underlying MCP-1-induced macrophage phenotypic switching and the mechanism by which M2 macrophages promote bone regeneration remain to be elucidated. Clarifying these mechanisms will contribute to establishing the clinical use of MSC-CM in bone regeneration.

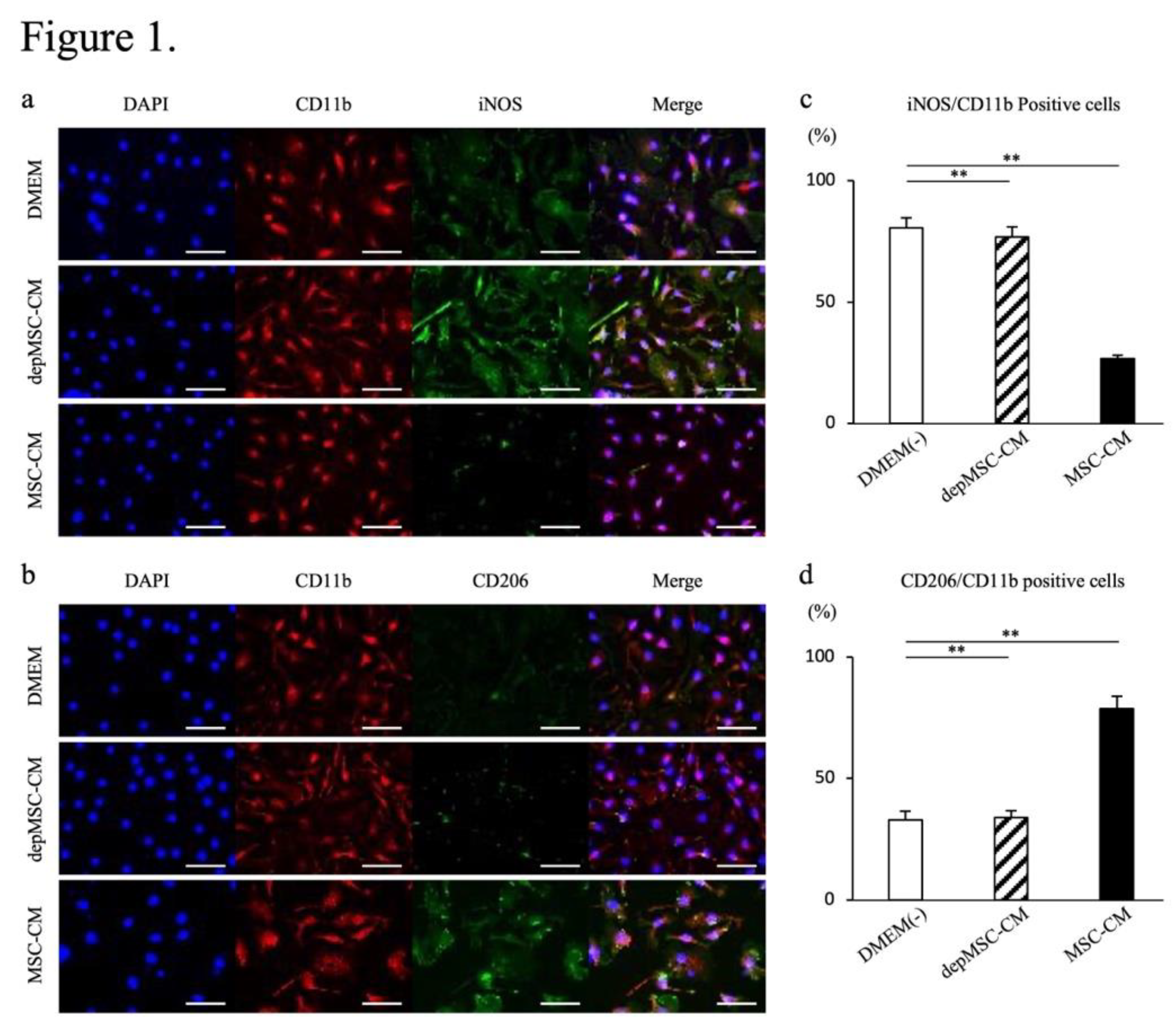

Figure 1.

Effects of MSC-CM and depMSC-CM on BMM gene expression. Representative images of BMMs immunocytologically stained for CD11b (red), iNOS (green), DAPI (blue) (a), CD11b (red), CD206 (green), and DAPI (blue, b) 48 h after incubation with MSC-CMs or depmSC-CMs. Scale bar: 50 μm. Ratios of iNOS and CD11b positive cells (c) and CD206 and CD11b positive cells (d). Gene expression in BMMs 48 h after incubation with MSC-CM and depMSC-CM (

Figure 2). The results are expressed relative to the mRNA expression levels in DMEM(-)-treated cells (n = 3 per group). Data are represented as mean ± SD; *

P < 0.05, **

P < 0.01.

Figure 1.

Effects of MSC-CM and depMSC-CM on BMM gene expression. Representative images of BMMs immunocytologically stained for CD11b (red), iNOS (green), DAPI (blue) (a), CD11b (red), CD206 (green), and DAPI (blue, b) 48 h after incubation with MSC-CMs or depmSC-CMs. Scale bar: 50 μm. Ratios of iNOS and CD11b positive cells (c) and CD206 and CD11b positive cells (d). Gene expression in BMMs 48 h after incubation with MSC-CM and depMSC-CM (

Figure 2). The results are expressed relative to the mRNA expression levels in DMEM(-)-treated cells (n = 3 per group). Data are represented as mean ± SD; *

P < 0.05, **

P < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Effects of MSC-CM and depMSC-CM on BMMs gene expression. Gene expression in BMMs 48 h after incubation with MSC-CM and depMSC-CM (Fig.2). The results are expressed relative to the mRNA expression levels in DMEM(-)-treated cells (n = 3 per group). Data are represented as mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Effects of MSC-CM and depMSC-CM on BMMs gene expression. Gene expression in BMMs 48 h after incubation with MSC-CM and depMSC-CM (Fig.2). The results are expressed relative to the mRNA expression levels in DMEM(-)-treated cells (n = 3 per group). Data are represented as mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Figure 3.

Effects of MSC-CM and depMSC-CM on hMSC gene expression. Relative expression levels of osteogenesis-related genes in MSC- and depMSC-CM. The results are expressed relative to the mRNA expression levels in DMEM(-)-treated cells (n = 3 per group). Data are represented as mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Figure 3.

Effects of MSC-CM and depMSC-CM on hMSC gene expression. Relative expression levels of osteogenesis-related genes in MSC- and depMSC-CM. The results are expressed relative to the mRNA expression levels in DMEM(-)-treated cells (n = 3 per group). Data are represented as mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

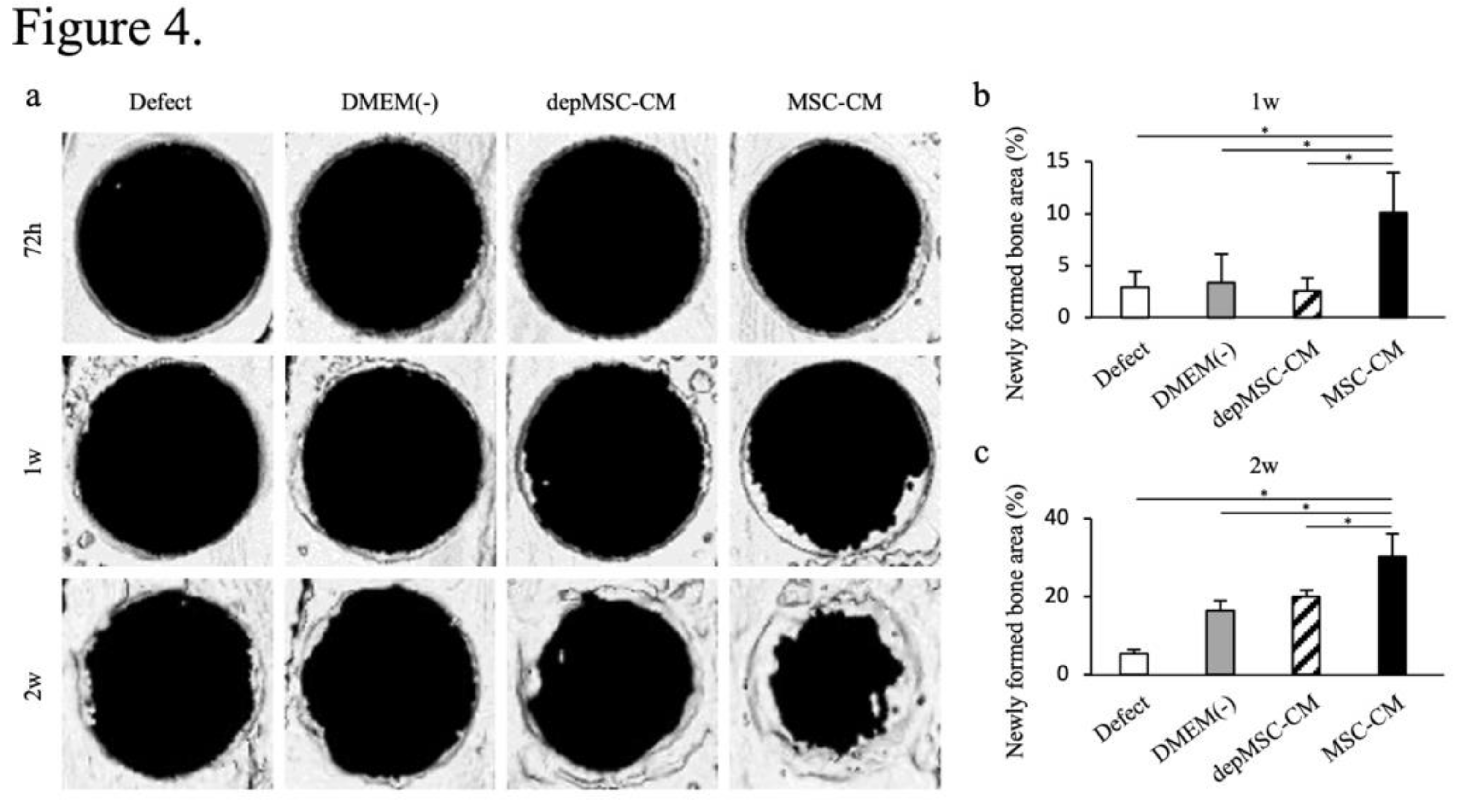

Figure 4.

Micro-CT analysis of bone formation after implantation of MSC-CM and depMSC-CM. Reconstructed images of rat calvarial defects at 72 h, 1 week, and 2 weeks after implantation of MSC-CM, depMSC-CM, or DMEM(-) (a). Patients in the defect group did not undergo implantation. Newly formed bone areas were measured, indicating that MSC-CM significantly promoted bone regeneration at 1 and 2 weeks after implantation compared to the other groups (b, c). Data are represented as mean ± SD; *P < 0.01.

Figure 4.

Micro-CT analysis of bone formation after implantation of MSC-CM and depMSC-CM. Reconstructed images of rat calvarial defects at 72 h, 1 week, and 2 weeks after implantation of MSC-CM, depMSC-CM, or DMEM(-) (a). Patients in the defect group did not undergo implantation. Newly formed bone areas were measured, indicating that MSC-CM significantly promoted bone regeneration at 1 and 2 weeks after implantation compared to the other groups (b, c). Data are represented as mean ± SD; *P < 0.01.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical staining of the newly formed bone 72 hours, 1 week, and 2 weeks after implantation. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed the orientation of the specimens, indicating newly formed bone edges and surrounding tissue (a). Seventy-two hours after implantation, the number of iNOS-positive cells was lower in the MSC-CM group than in the other groups, whereas the number of CD206 positive cells was the highest among all groups (b). Data are represented as mean ± SD; *P < 0.01.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical staining of the newly formed bone 72 hours, 1 week, and 2 weeks after implantation. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed the orientation of the specimens, indicating newly formed bone edges and surrounding tissue (a). Seventy-two hours after implantation, the number of iNOS-positive cells was lower in the MSC-CM group than in the other groups, whereas the number of CD206 positive cells was the highest among all groups (b). Data are represented as mean ± SD; *P < 0.01.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemical staining of the newly formed bone 1 week after implantation. One week after implantation, the number of iNOS-positive cells was lower in the MSC-CM group; however, there were no significant differences in the number of CD206 positive cells between the groups (a, b).

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemical staining of the newly formed bone 1 week after implantation. One week after implantation, the number of iNOS-positive cells was lower in the MSC-CM group; however, there were no significant differences in the number of CD206 positive cells between the groups (a, b).

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemical staining of the newly formed bone two weeks after implantation. Two weeks after implantation, the number of iNOS-positive cells was lower in the MSC-CM group; however, there were no significant differences in the number of CD206 positive cells between the groups (a, b).

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemical staining of the newly formed bone two weeks after implantation. Two weeks after implantation, the number of iNOS-positive cells was lower in the MSC-CM group; however, there were no significant differences in the number of CD206 positive cells between the groups (a, b).

Figure 8.

The ratio of CD206-positive (M2) and iNOS-positive (M1) cells after implantation. At Seventy-two hours, one week and two weeks after implantation, MSC-CM improved the M2/M1 ratio around the newly formed bone edge, while it remained low in the other three groups.

Figure 8.

The ratio of CD206-positive (M2) and iNOS-positive (M1) cells after implantation. At Seventy-two hours, one week and two weeks after implantation, MSC-CM improved the M2/M1 ratio around the newly formed bone edge, while it remained low in the other three groups.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR.

| Gene |

|

Sequence |

Accession no. |

| OPN |

F |

5’-ACACATATGATGGCCGAGGTGA-3’ |

NM_000582.2 |

| |

R |

5’-GTGTGAGGTGATGTCCTCGTCTGTA-3' |

|

|

COLⅠ

|

F |

5’-CCCGGGTTTCAGAGACAACTTC-3’ |

NM_000088.3 |

| |

R |

5’-TCCACATGCTTTATTCCAGCAATC-3’ |

|

| ALP |

F |

5’-GCCATTGGCACCTGCCTTAC-3’ |

NM_000478.5 |

| |

R |

5’-AGCTCCAGGGCATATTTCAGTGTC-3’ |

|

| OCN |

F |

5’-CATGAGAGCCCTCACACTCCT-3’ |

NM_199173.5 |

| |

R |

5’-CACCTTTGCTGGACTCTGCAC-3’ |

|

| iNOS |

F |

5'-GCTGCCAAGCTGAAATTGAATG-3' |

NM_000625.4 |

| |

R |

5'-TCTGTGCCGGCAGCTTTAAC-3' |

|

| CD80 |

F |

5'-CACCTCCATTTGCAATTGACC-3' |

NM_005191.4 |

| |

R |

5'-TCCTGCAAAGCAACTGAAGTGA-3' |

|

| CD206 |

F |

5'-ATGCCCGGAGTCAGATCACAC-3' |

NM_002438.4 |

| |

R |

5'-TTCTGCAGCACTTTCAATGGAAAC-3' |

|

| Arg-1 |

F |

5'-CTGGCAAGGTGGCAGAAGTC-3' |

NM_000045.3 |

| |

R |

5'-ATGGCCAGAGATGCTTCCAA-3' |

|

| GAPDH |

F |

5’-AGGCTAGCTGGCCCGATTTC-3’ |

NM_001256799.2 |

| |

R |

5’-TGGCAACAATATCCACTTTACCAGA-3’ |

|