1. Introduction

Outlined in the Brazilian Land Statute (Brazil, 1964) and implemented through the actions of the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), the Brazilian National Agrarian Reform Policy is characterized as a public management tool aimed at land distribution processes. It involves the creation of rural settlements for the population without access to land ownership (Brazil, 1985; 2003). It is a national development project that generates employment and focuses on food production. It also aligns with the principles established by the United Nations for sustainable development, as outlined in the 2030 Agenda. The project aims to promote the eradication of poverty (SDG1), support family farming (SDG2), gender equality (SDG5), social security in settlements (SDG8), and the reduction of inequalities (SDG10), among other goals (UN, 2015).

Agrarian reform settlement comprises a set of agricultural units on a rural property. It can be proposed and implemented by the Executive Branch at various levels: federal, state, or municipal. In the case of federal agrarian reform settlements, INCRA is responsible for providing the necessary infrastructure for these agricultural units on the rural property. The implementation of this infrastructure is essential to meet basic human needs and ensure sustainable development of the settlements. Studies highlight the importance of rural settlements for the development and stimulation of the local economy (Leite et al. 2004; Durante et al., 2020). However, factors such as location, soil quality, water availability, electric energy, roads, and the type of parceling can limit the productive and organizational development of rural settlements (Hora et al. 2019). From this perspective, inadequate infrastructure directly impacts the possibilities for the development and consolidation of settlements and, consequently, the quality of life of settled families (IPEA 2010). When infrastructure is insufficient, a dependence on the state and precarious conditions are observed.

The Brazilian Normative Instruction No. 129 (INCRA 2022) establishes administrative procedures for the creation of settlement projects and environmentally differentiated settlement projects by this agency. A Settlement Project, hereinafter referred to as SP, is defined as the “conventional project modality created or recognized by INCRA, where the area is intended for the settlement of families of farmers or rural workers.” An Agroextractive Settlement Project, referred as ESP, is defined as an “environmentally differentiated project aimed at exploiting areas with extractive resources through economically viable, socially just, and ecologically sustainable activities to be carried out by the populations traditionally occupying the area” (INCRA, 2022).

In the State of Pará, located in the northern region of Brazil within the Amazon area and the focus of this study, there are nine types of settlements, seven of which cater to the local cultural diversity of traditional populations (INCRA, 2022). These settlements were created in response to the demands of socio-environmental movements to ensure that the agrarian reform model also prioritizes the way of life of traditional Amazonian populations, thereby guaranteeing land ownership rights along with the preservation and conservation of the forest and its territories (MAPA, 2024).

The selection process for families or individuals residing in Agroextractive Settlement Projects (ESP) for inclusion in the National Agrarian Reform Program (PNRA) is regulated at the national level by The Brazilian Normative Instruction No. 136 (INCRA, 2023). The selection is conducted by INCRA’s regional superintendencies with the participation of environmental agencies and civil society. The process is limited to families who already reside in, use, and occupy the area traditionally. Selection criteria include self-identification as a member of a traditional community and recognition by the group, meeting the requirements of family farming established by law, sustainable use of natural resources, ancestral heritage, and a history of occupation demonstrating a deep connection with the environment in which they are situated.

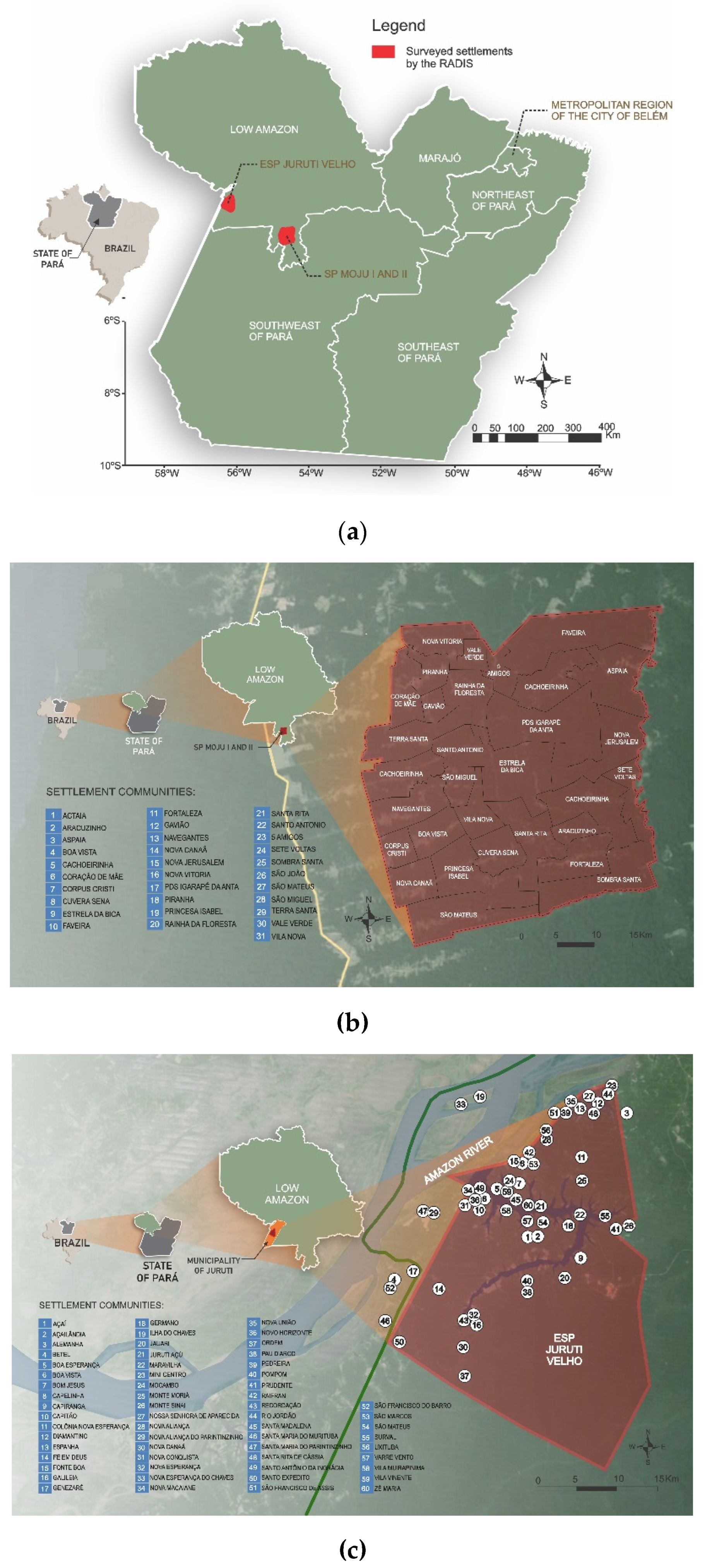

In this context, this study focuses on evaluating the environmental impacts and infrastructure deficiencies in the Moju I and II Settlement Project (SP) and the Juruti Velho Agroextractive Settlement Project (ESP), both implemented in the state of Pará and located in the Lower Amazon mesoregion, with environmentally differentiated characteristics. The first is a federal settlement in the conventional modality, located in the municipalities of Belterra, Mojuí dos Campos, and Placas. It was created by Ordinance No. 87 on November 18, 1996, following expropriation by Decree No. 68.443 on March 29, 1971 (INCRA, 1971). It covers a total area of 134,896 hectares, situated 34 kilometers from Santarém and 1,300 kilometers from Belém. Access is by land via six main branches located between kilometers 119 and 145 of the BR-163 (Souza and Alencar, 2020).The second is located in the district of Juruti Velho (also known as Vila Muirapinima), created on November 10, 2005, covering an area of 109,551 hectares approximately 45 kilometers from the municipal seat of Juruti. It has a population of about 20,000 inhabitants (IBGE, 2017), distributed across 71 traditional communities, of which 15 are community centers.

The Brazilian Agrarian reform settlements serve to decentralize land ownership and improve the quality of life for families of farmers or rural workers through the development of various productive activities on the allotted land. The actions for the development and consolidation of the settlement are carried out with resources from INCRA or through partnerships with local governments and/or public institutions. It is evident that the consolidation process of the settlements involves the implementation of lots and the construction of infrastructure for the formation of agricultural units, which induces environmental impacts despite Brazilian legislation imposing the need for preservation areas.

Environmental impact is understood as any alteration of the physical, chemical, and biological properties of the environment caused by any form of matter or energy resulting from human activities (Brazil, 1986, p. 01). Such alterations can directly or indirectly affect the health, safety, and well-being of the population, as well as the biota, the aesthetic and sanitary conditions of the environment, and/or the quality of environmental resources.

Among the various tools for environmental impact assessment is the “Leopold Matrix” (Cavalcante and Leite 2016; Leopold 1977), which allows for the evaluation of interactions between actions taken on a specific environmental aspect, such as biological, physical, chemical, or anthropic. This matrix has undergone adaptations and has been used in various forms over time, depending on the process type being evaluated (Callejas et al., 2024). In this context, the researches of Brandão Jr. and Souza Jr. (2006), Schneider and Peres (2015), and Farias et al. (2018) are notable. They focused on assessing the environmental impact resulting from deforestation in agrarian reform settlements in the Amazon region using the Leopold Matrix, without however analyzing the impact of the existing infrastructure.

Based on the details provided earlier, this research aims to evaluate whether different types of settlements, such as those implemented in Moju I and II (SP type) and Juruti Velho (ESP type), have induced varying environmental impacts and infrastructure conditions in these settlements, as well as provided different levels of housing habitability. The goal is to draw a parallel between these types, thus supporting the formulation of public policies to enhance the quality of life for future settled families.

2. Materials and Methods

The sample consists of 4,926 lots in SP Moju I and II and ESP Juruti Velho (

Table 1,

Figure 1), derived from the Environmental Regularization Diagnostic Project for Agrarian Reform Settlements (RADIS Project/UFMT) (Durante et al., 2022). Among various objectives, this project conducts technical visits to agrarian reform lots to administer self-reported questionnaires on socioeconomic and environmental aspects to family farmers.

The methodology is based on the Leopold Matrix (Leopold, 1971) and was applied to evaluate environmental impacts, infrastructure deficiencies, and housing habitability conditions in the two settlements. The analysis included environmental variables related to landscape degradation and issues concerning access to water infrastructure, basic sanitation, telecommunications, electricity, and housing habitability in the two types of settlements. These variables were derived from the structured questionnaire of the RADIS Project/UFMT (Durante et al., 2022).

Based on the work developed by Topanotti (2002), the characteristics of the numerical classes (1 to 4) established for each indicator in this research were adapted for the rural context, in ascending order from the least to the greatest impact. The indicators are based on the environmental and infrastructure data of the Conventional Settlement (SP) and Agroextractive Settlement (ESP) projects studied. The classes were divided equally, taking as reference the data from the indicators collected for Brazil and the state of Pará. During the impact assessment stage, scores of 2, 3, 5, and 7 were assigned to classes 1, 2, 3, and 4 respectively for the indicators identified in the research.

Table 2 shows the ranges and classes defined for each of the indicators, referencing the recorded variables as found in the literature regarding each of the environmental impacts and infrastructure deficiencies considered in the study, explained below.

Equation 01 was used to calculate the Impact Magnitude, where the sum of the weights, specifically in this work, equals twenty points. Subsequently, the Impact Magnitude was normalized to a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 and 10 representing the minimum and maximum values of the Impact Magnitude.

The research encompassed components that experience anthropic impact or influence the quality of life of settlers, namely: land use (deforestation of native vegetation), issues of inadequate infrastructure (access and supply of water, electrification, telephone and internet accesses, and irrigation use), water pollution and soil contamination (discharge of wastewater and disposal of pesticide packaging), and habitability conditions here expressed in terms of minimum built area per person in the buildings implanted in in settlements as suggested by Folz and Martucci (2013).

Recognizing that each environmental component and the lack of adequate infrastructure influence the quality of life for settlers, the relevance of each component was established based on a subjective value ranging from 1 to 3, as suggested by Leopold (1977). In this research, relevance was validated by a panel of experts, adopting the following values: a) 3, for impacts of native vegetation deforestation and lack of access to water and energy; b) 2, for impacts related to the disposal of sanitary effluents, pesticide packaging, and type of water supply; and c) 1, for access to irrigation, telephony, internet, and habitability conditions of the building expressed by area (Callejas et al., 2024).

To the extreme conditions that the environment or settlers endure, whether caused by anthropic impact or lack of infrastructure, a maximum value was assigned, calculated in the matrix using a magnitude of 10. Since the research focuses on assessing impacts to conduct a comparative analysis between settlement projects developed in conventional (SP) and agroextractive (ESP) modalities, the impact score represented by the product of magnitude and relevance was not quantified, as it contributes little to the comparative analysis of the settlements.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 3 presents the indicators of degradation of the environmental landscape and infrastructure in the settlements researched located. These results are detailed and discussed in the following sections.

3.1. Environmental Impacts

3.1.1. Degradation of the Environmental Landscape—Native Preservation Area in SP and ESP Settlements

The percentage of settlements included in the sample within the four preservation ranges established in the research, based on the references of preservation area percentages quantified in the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) for both Brazil (26.7%) (set as the lower limit) and the state of Pará (33.2%) (set as the upper limit) (Embrapa Territorial, 2020) can be visualized in the

Table 2 (indicator 1).

An overall analysis of the ranges reveals that the vast majority of settlement lots in the state of Pará report self-declared preservation rates higher than the national average quantified in the CAR. Given that Pará is located in the Amazon biome, which has stricter deforestation criteria, and also because one of the settlements is characterized as extractive, preservation rates are elevated, exceeding both the national and state averages (>98%). It is important to highlight that, according to Embrapa Territorial (2020), the national average rate of native forest preservation assessed in the CAR for the Amazon biome is 53.4%.

For the purpose of determining scores, the decision was made to use the national average rate as the lower limit and the state rate as the upper limit for reference values of native forest preservation within the settlements for the computation of the environmental impact indicator. Four classes were defined to represent the degrees of impact, determined by summing the percentages of one class with the percentages of previous classes and checking if the result fits within the range defined for the class (

Table 1).

The SP and ESP studied in the state of Pará stand out for their high percentages of native forest preservation, exceeding the average rate determined for the state (24.4%) and the Amazon biome (53.4%), classifying them as having low environmental impact (1). Notably, the ESP’s exploitation is based on the sustainable use of existing renewable natural resources in the area, resulting in reduced environmental impact. According to Alencar (2016), the Forest Settlement Projects (FSP), Extractive Settlement Projects (ESP), and Sustainable Development Projects (SDP) have significantly contributed to forest conservation, accounting for only 7% of the deforestation occurring in Amazonian settlements.

3.2. Infrastructure in SP/ ESP Settlements

3.2.1. Access to Water

To consider the rates of adequate water service in rural establishments, the data presented by the National Rural Sanitation Program (PNSR) (Brazil, 2019) was used, indicating that 40% of the Brazilian population is adequately served by this resource, while in the state of Pará, the rate is slightly higher at 48.2%. In this perspective, it is noted that, on average, 88.2% of settlers report not suffering from water intermittency or rationing throughout the year, a rate much higher than that found in the PNSR (

Table 3, indicator 2). Notably, the ESP has nearly 100% service coverage. However, this indicator cannot be generalized as the sample is limited to only two settlements located in the same mesoregion of the state of Pará.

It is observed that the ESP settlers reported fewer issues with service compared to the SP, which suffers more from water shortages. When comparing the collected data with those investigated by Alves, Figueiredo, and Bonjour (2009) and by Molch, Simplício, and Pinheiro (2022), there is a notable improvement in the average service rates over the last two decades in the SP and ESP studied in Pará, even relative to the regional average.

Therefore, due to the high rates of access to water supply quantified in the SP/ESP in Pará, these are classified in impact class 1. The high rates quantified in the state of Pará are most likely associated with the presence of hydrographic basins (Amazon, Tocantins Araguaia, and Atlantic Northeast) that contain a large number of rivers, aquifers, and springs. Indeed, the ESP is located next to the Igarapé Juruti Grande, while the conventional SP suffers from greater intermittency due to the absence of this resource in its vicinity. An important aspect relates to the quality of the water being accessed by settlers, considering that there are a number of diseases that can be transmitted through water linkage.

3.2.2. Water Supply Type

The survey revealed contrasts between the settlements studied (

Table 3, indicator 3). In the SP, access to water is primarily through wells or springs, followed by rivers/streams and ponds or reservoirs. This characteristic may be associated with the social organization of these settlements (individual lots) and the ease of access to water due to the large number of aquifers and springs serving the state of Pará (Nascimento et al., 2022). On the other hand, ESP, occupied by traditional populations in Pará that focus on exploiting extractive resources, primarily access water through community networks, followed by wells or springs and rivers/streams. As these settlements are organized into communities, most settlers are supplied through community micro-systems (Silva, 2019), which explains the difference from conventional SP.

Since 2004, evidence has shown that settlements across Brazil access water through common wells (37%) and artesian wells (27%), springs (34%), rivers (18%), and ponds (10%), with supply from public networks being minimal (only 5%) (Leite et al., 2004). It is important to highlight that this research indicates that the majority of families still use water resources available on their properties, such as rivers, streams, and ponds, without any treatment for consumption, posing a health risk to settlers. A contributing factor to the lack of network advancement in SP is the high cost of implementation due to the structural configuration of the lots, which are distant and isolated. Strategies and actions are crucial to drive the improvement of this indicator.

The classification of impact levels based on the different types of water supply modalities considered the data presented in the National Rural Sanitation Program (Brazil, 2019), using the average rate of the modalities identified in the biomes present in the state of Pará (

Table 2). In SP, access to water is mainly through wells or springs, while in ESP it is through community networks, placing them in impact classes 2 and 1, respectively. This is due to the social organization of the settlements, as SP are structured around individual lots, whereas ESP are organized in a community format, close to each other, which facilitates and reduces the costs of network implementation.

3.2.3. Sanitation Modality

Regarding sanitation, the most common method of wastewater disposal remains the cesspit or soakaway (<56%), and the treatment via septic tanks or other ecological methods is still incipient in both settlement modalities (

Table 3, indicator 4). Sanitation networks remain a distant reality for settlers, despite the existence of community water supply systems due to the organizational structure of the ESP. Nevertheless, proper disposal of wastewater in these communities is still nascent, as high rates of self-declaration indicate that there is no form of sanitation in both types of settlements, meaning there is no solution for wastewater management. These findings align with Silva (2019), highlighting the lack of sanitation as one of the main socio-environmental issues reported by settlers in the ESP of the Amazon region.

Rudimentary cesspits (black pits) and soakaways are characterized as inadequate and temporary solutions for the disposal of domestic sewage, potentially contaminating groundwater. Consequently, the settlements studied fall into impact class 4, as over 50% of settlers declared they do not have any method for disposing of their effluents. Despite the limited progress in this area in the ESP (where more than 37% declared having no solution), these settlements are classified as impact class 3.

According to Pereira Júnior et al. (2023), there is a direct relationship between groundwater contamination and cesspits, with the possibility of these contaminating the groundwater, which can affect rivers and streams and increase the incidence of waterborne diseases, especially since most settlers use water from wells or springs. Since ESP utilize community micro-systems, generally through (semi)artesian wells, contamination is less likely. This is important as settlers often lack information about potential waterborne diseases and knowledge about basic sanitation and environmental conservation (Lannes and Soares, 2014). According to the perception of farmers in the agroextractive settlements in the region of Santarém-PA, river, stream, and lake pollution, among others, is the third most reported socio-environmental issue (Silva, 2019).

3.2.4. Electrification Assess

The survey reveals that the settlements studied slightly exceed the regional average (62.5%), but still fall short of the national average (83.5%) (

Table 3, indicator 5), despite the provision of electricity being considered essential. This situation is not unique to the state of Pará but also occurs in other regions within the Amazon biome, such as the SP located in the northern part of Mato Grosso state (Callejas et al., 2024). Electrification is a necessary resource to improve the quality of life for the population and is a key factor in promoting socioeconomic development, presenting a challenge for the Brazilian state to overcome.

Since the rates observed in the studied settlements are similar to and slightly better than those identified in the 2017 Agricultural Census (IBGE, 2019) in the Pará region (62.5%), both modalities fall into impact class 3. Given this scenario, it is clear that universal access to electrification is still far from being achieved in Pará, highlighting the need for the continuation of the National Program for the Universalization of Access and Use of Electric Energy - “Light for All” (Brazil, 2023).

3.2.5. Access to Telecommunication

Regarding telecommunications infrastructure, the average rates of telephony and internet access in Pará are low, with 38% and 12.7% coverage, respectively, as verified in the 2017 Agricultural Census (IBGE, 2019). Consequently, values slightly above the regional average result in lower impact quantification, despite the low rates of this infrastructure quantified in the settlements studied, still generally far from full coverage (

Table 3, indicator 6).

In the SP, there is a certain balance in terms of service rates in both modalities, with access to telephony falling into impact class 3, and internet access into class 1. Conversely, the ESP stands out for higher telephony service, falling into impact class 1, though internet access remains incipient, despite being classified in impact class 2. The 2022 TIC Households survey (CGI, 2022) points to an increase in the proportion of internet users in rural areas, from 53% in 2019 to 73% in 2021. However, the universalization of this service remains far from the reality observed in the settlements studied, posing a significant challenge to achieve the universal coverage established by the Universal Telecommunications Service Fund, instituted by Law No. 9.998 since 2000 (Brazil, 2000).

3.2.6. Access to Irrigation Infrastructure

In general, irrigation in rural properties is still an incipient resource, with its application not exceeding 10% in Brazilian rural properties. In the state of Pará, its use in settlements is very limited, at 2% (

Table 3, indicator 7). It is worth noting that this infrastructure serves as a strategy to prevent production losses due to drought, produce during off-seasons, and increase productivity and the quality of the final product. However, it requires financial investment to be implemented. In this perspective, most likely due to the necessary investments for introducing this technology in properties, the research did not identify the use of this resource in the settlements studied. In the ESP, since exploitation is carried out through agroextractivism, the impact category does not apply, as these resources are exploited considering the natural cycle.

Due to the low usage of this resource in the SP, the impact class is considered high, reaching a maximum grade of 4. This reality indicates the need for a specific program aimed at agrarian reform settlements to overcome the observed limitation. Research has already been conducted on the application of the technique in settlements using low-cost alternative irrigation systems, such as those using PET bottles and black polyethylene hose as sprinklers (Eiden et al., 2016). Alternative methods are important considering the consequences of temperature rise due to climate change, which has caused changes in rainfall patterns (more irregular) and extreme weather events (such as prolonged droughts), indicating that irrigation may play an important role in future agricultural production.

3.2.7. Destination of Agrochemical Packaging

In this regard, it was found that the rates of returning pesticide containers to the seller/manufacturer in the settlement SP and ESP were low (>50%) (

Table 3, indicator 8). The highest rates of improper disposal of containers were observed in settlements where exploitation occurs through extractivism. Burning is still common in both types of settlements. Proper disposal reduces health risks for settlers and environmental contamination, especially of water sources, due to the improper disposal of containers on rural properties (Bernardi, Hermes, and Boff, 2014).

Despite the low return rates observed, there is an improvement in the proper disposal of containers (>50%) compared to those reported in the National Rural Sanitation Program (Brazil, 2019), which was 21.8% in Pará. Thus, a low environmental impact is identified for this aspect in the settlements, classifying them in impact class 1. Federal Law No. 9.974 (Brazil, 2000) regulates the proper disposal of empty pesticide containers, establishing principles for the environmentally correct handling and disposal of empty pesticide containers through shared responsibilities among all agricultural production agents – farmers, distribution channels and cooperatives, industry, and government. According to the National Institute for Processing Empty Packages (2018), 95% of pesticide containers sold in Brazil can be recycled if properly washed.

3.2.8. Infrastructure of Useful Area Built in Settlements

The data survey indicated that most homes in the SP and ESP meet the minimum infrastructure standard of 18m² per person, which is considered an acceptable value to offer a minimum of comfort for low-income families and to meet individual and family balance needs (Folz and Martucci, 2013) (

Table 2). Despite this, higher rates are observed in the SP compared to the ESP. It is important to note that this indicator does not assess the functionality of the living spaces in the settlements or their anthropodynamic standards, which consider the minimum availability of spaces for the use and operation of the housing unit (ABNT, 2021). It also does not evaluate the degree of consolidation of the buildings, although studies indicate that edifications in agrarian reform settlements are usually built in stages, with little technique in the application of construction materials and sizing (Durante et al., 2022).

3.3. Summary of Indicators

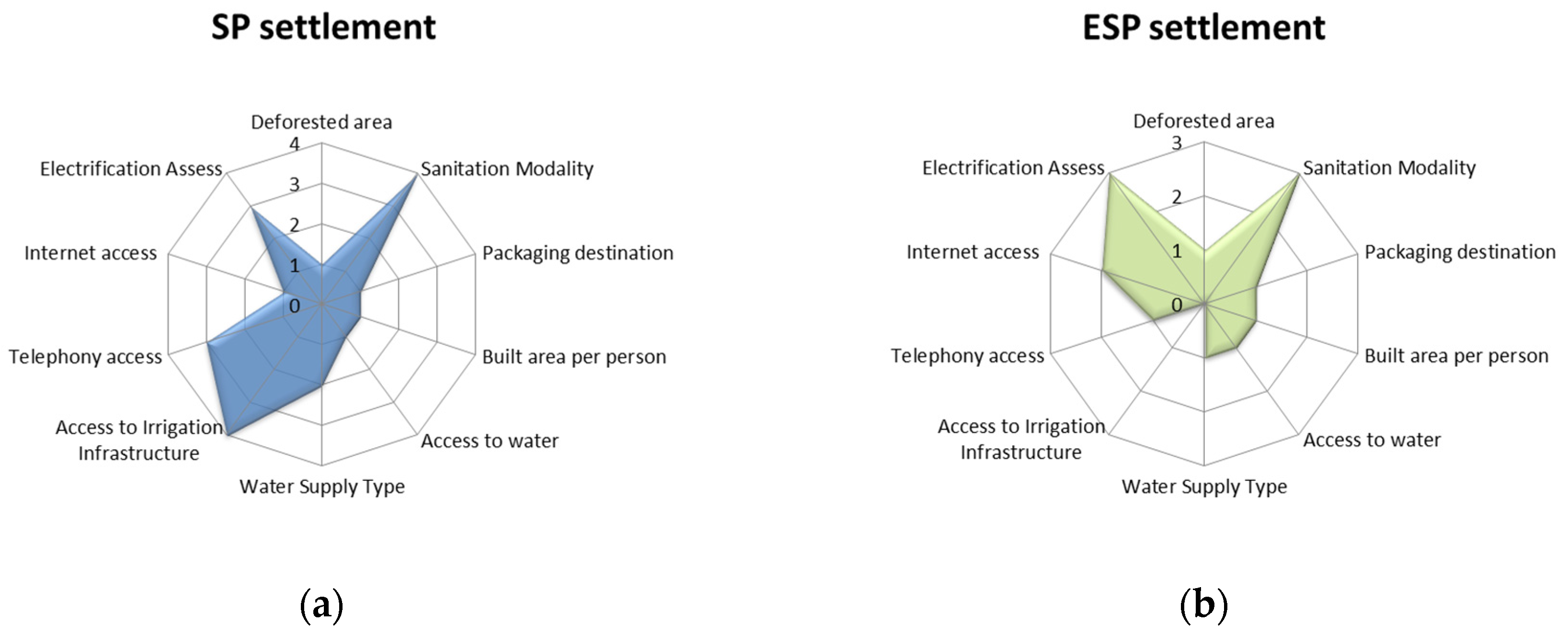

A summary of the impact classes identified in the settlements SP and ESP can be seen in

Figure 2. As can be observed, the lowest environmental impacts are concentrated in the SP, since the exploitation of these areas has a lesser impact on the environment in terms of deforestation. The ESP also shows better access to water supply and telephony infrastructure, but worse access to internet and electrification. Other impacts are similar in both settlement modalities, with little difference between them.

The calculation of the normalized impact magnitudes on a scale from 0 to 10 indicates a contrast between the SP (5.2) and the ESP (3.3).

Regarding the SP, it is important to highlight that the impact is similar to those observed in the northern region of Mato Grosso state, Midwest of Brazil, as these areas are undergoing very similar economic and social development (Callejas et al., 2024). The environmental impacts in this type of settlement are related to landscape degradation, lack of infrastructure, and habitability conditions, similar to those identified in two mesoregions of the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil (Durante et al., 2022), where the impacts found in the Norte de Minas mesoregion (7.0) and Triângulo Mineiro/Alto Paranaíba (6.0) were slightly higher.

Regarding the ESP, the lower quantified values are due to the land exploitation being conducted through agroextractivist activities, whereas in the SP, it is primarily through agropastoral activities. The design of settlement lots also facilitated collective water supply networks, reducing the impact of contamination of distributed water.

Therefore, public policies focused on creating infrastructure and generating sustainable production to support development should be promoted by the state to create minimum conditions for the permanence of settled families, avoiding accelerated deforestation and environmental degradation, which can contribute to forest conservation and sustainable development in agrarian reform settlements, particularly in SP types located in the Amazon region. This need is evident as among the two settlement types, the SP shows the highest impact magnitude identified in this research.

5. Conclusions

The analysis technique using the Leopold Matrix proved to be an appropriate tool for evaluating environmental impacts and infrastructure deficiencies in the two types of agrarian reform settlements located in the state of Pará. By using the percentage of native area as an indicator, the impact of natural landscape degradation was assessed in the settlements located in the Lower Amazon mesoregion, Pará.

The SP modality, due to the economic activities practiced within it, imposes a high level of natural landscape degradation, with an average deforestation percentage exceeding 80% of legal reserves, as stipulated by the current Brazilian Forest Code of 2012 for the Amazon biome. These impacts are similar to those quantified in settlements in the northern and northeastern mesoregions of Mato Grosso, also within the same biome. The Amazon biome has been under significant pressure from agricultural activities within these states, the current frontier of agricultural expansion in the country.

In contrast, the ESP modality, due to the nature of the extractive activities developed within it, requires less deforestation for crop cultivation or pasture, resulting in lower land use impacts. This type of settlement contributes the least to deforestation in the Amazon biome, making it a viable alternative for sustainable development.

The water access indicator revealed that the SP modality (<67%) is more affected by water scarcity than the ESP (97.5%). This is partly explained by their geographical location (the ESP is situated near water courses) and the type of supply they adopt. The community-based organizational model proposed in the ESP facilitates water distribution through community micro-systems (water is drawn from artesian or semi-artesian wells), representing an advancement in terms of both quantity and quality assurance.

Regarding basic sanitation, there has been little improvement compared to the mapping conducted in the National Rural Sanitation Program (Brazil, 2019), with rudimentary cesspits and soakaways still being the main solutions for wastewater disposal in both settlement types. Networked disposal and septic tank treatment remain distant realities in these settlements. It should be noted that the wastewater disposal found in both settlements poses a high potential for groundwater contamination, which can increase the incidence of waterborne diseases among settlers.

Rural electrification is an essential service guaranteed by the Brazilian Federal Constitution; however, its reach in the settlements SP and ESP is still limited (<67%), indicating a need for investments in this type of infrastructure in the Amazon biome, aiming for universalization through government programs such as the National Program for the Universalization of Access and Use of Electric Energy - “Light for All”.

Despite the average telephony and internet rates in Pará showing better performance than regional and national levels, the universalization of communication in the settlements SP and ESP is still far from being achieved. Service coverage in both settlement types does not exceed 73% for telephony and 58% for internet. The SP is better served in terms of internet services, while the ESP excels in telephony services. It is important to emphasize that universalizing telecommunications services is still a significant challenge to be overcome in rural areas of Brazil.

Irrigation in SP crops is still a very restricted strategy, with only 2% of settlers reporting its use. The main obstacle is the need for financial investments to introduce this technology on properties, limiting its use. Therefore, to increase the rates recorded in this research, there is a need for specific programs aimed at agrarian reform settlements for this purpose.

Regarding the environmental impact of pesticide container disposal, it was found that almost 50% of ESP settlers declare they burn or discard them, while in the SP this rate drops to 30%, which is still considered high. Compared to data quantified in the National Rural Sanitation Program, there has been an improvement in proper disposal within the studied settlements, which is beneficial for reducing health risks for settlers and helping to avoid environmental contamination. Nonetheless, reducing burning or discarding strategies is still a goal to be achieved in these settlements, with the ESP showing higher impacts in this aspect.

The analysis of the usable built area in the studied settlements showed that most of the housing in the settlements meets the minimum acceptable standard of more than 18m² per person, ensuring comfort and individual and family balance (Folz and Martucci, 2013). However, this indicator does not consider the functionality of the residential spaces in the settlements or their anthropodynamic standards aimed at the minimum availability of areas for the use and operation of buildings. Therefore, future interviews should include questions that allow for the recording of the degree of consolidation of buildings in agrarian reform settlements.

Finally, the analysis of the impact magnitude (normalized from zero to ten) according to the Leopold Matrix methodology reveals the asymmetry in the two types of settlements. The ESP presents lower environmental impacts due to its form of exploitation, with less environmental degradation in terms of deforestation. Conversely, in the SP, aligned with its agropastoral form of economic activity, the impacts are greater due to land use for income generation.

The ESP also shows better access to water supply and telephony infrastructure, but worse access to internet and electrification compared to the SP. It is worth noting that both settlement types still use rudimentary technologies for wastewater treatment, which impacts their living environment and can compromise settlers’ health. The same applies to container disposal, with environmental impacts since a significant number of settlers declare they burn or discard pesticide containers. As for other impacts, they are similar, with little differentiation between the two modalities studied. In conclusion, it is evident that the ESP has lower impacts compared to the SP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.J.A.C. and L.C.D.; methodology, I.J.A.C. and L.C.D.; validation, I.J.A.C., L.C.D, G.G.D.N., O.C.R., P.C.V., R.F.S.T., D.M.D.F.L. and K.A.C.R.; formal analysis, I.J.A.C., L.C.D. and P.C.V.; investigation, I.J.A.C., L.C.D. and P.C.V.; resources, P.C.V..; data curation, R.F.S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, I.J.A.C. and L.C.D.; writing—review and editing, G.G.D.N., O.C.R. and P.C.V.; visualization, K.A.C.R.; supervision, P.C.V.; project administration, P.C.V.; funding acquisition, P.C.V and R.F.S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) and by Federal University of Mato Grosso.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the field teams and all family farmers who participated in the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- Alencar, A. et al. 2016. Deforestation in Amazonian Settlements: History, Trends and Opportunities. Brasília: IPAM. 93p.

- Alves, J., Figueiredo, A. M. R., & Bonjour, S. C. M. (2009). Rural Settlements in Mato Grosso: An Analysis of Data from the Agrarian Reform Census Socioeconomic Overview, 27(39), 152-167.

- Brazilian Association of Technical Standards (ABNT). NBR 15575-1:2021 - Residential buildings — Performance Part 1: General requirements. Rio de Janeiro. 2021.

- Azevedo, M. A. M.; et al. 2024. Strategies and challenges in the development of rural settlement projects in the Amazon. Journal of Management and Secretariat, 15(8), e4065.

- Bernardi, A. C. A., Hermes, R., & Boff, V. A. (2028). Management and Destination of Agrochemical Packaging. Perspectiva, 42(159), 15-28.

- Brandão Jr, A., & Souza Jr, C. (2006). Deforestation in agrarian reform settlements in the Amazon. The State of the Amazon, 4. Available online: https://encurtador.com.br/Igrqy (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Brasil. Resolution CONAMA No. 01, January 23, 1986. Considering the need to establish definitions, responsibilities, basic criteria and general guidelines for the use and implementation of the Environmental Impact Assessment as one of the instruments of the National Environmental Policy. Official Gazette of the Federative Republic, Brasília, DF, 23 jan. 1986.

- BRASIL. Law No. 9,974 of June 6, 2000. Provides for research, experimentation, production, packaging and labeling, transportation, storage, marketing, commercial advertising, use, import, export, final destination of waste and packaging, registration, classification, control, inspection and supervision of pesticides, their components and the like, and provides other measures. Official Gazette of the Federative Republic, Brasília, DF, 07 jun. 2000.

- Brasil. Decreto nº 11.628, de 4 de agosto de 2023. Provides for the National Program for Universal Access to and Use of Electric Energy - Light for All. Official Gazette of the Federative Republic, Brasília, DF, 07/08/2023, pág. nº 1. Available online: https://encurtador.com.br/TZU6x (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Brasil. Lei nº 9.998 de 17 de agosto de 2000. Establishes the Telecommunications Services Universalization Fund. Official Gazette of the Federative Republic, Brasília, DF, 18/08/2000, pág. nº 1. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9998.htm (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Callejas, I. J. A.; et al. 2024. Environmental and infrastructure impacts on agrarian reform settlements in Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Contribuciones a las Ciencias Sociales, 17(7), e8584.

- Cavalcante, L. G., & Leite, A. O. S. 2026. Application of the Leopold Matrix as a tool for assessing environmental aspects and impacts in a gas cylinder factory. Revista Tecnologia, 37(1/2), 111-124.

- Internet Steering Committee in Brazil (CGI). 2022. Research on the use of information and communication technologies in Brazilian households [livro eletrônico]: TIC Domicílios 2021. São Paulo: Comitê Gestor da Internet no Brasil.

- Durante, L. C.; et al. 2020. Environmental impacts and infrastructure in agrarian reform settlements in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Sustainability in Debate, 11(3), 445–484.

- Durante, L. C.; et al. 2022. Socioeconomic and Environmental Atlas of Agrarian Reform Settlements. Ananindeua, PA: Palafita Book.

- Eiden, A.; et al. 2016. Preliminary evaluation of a low-cost irrigation system in agrarian reform settlements on the western edge of the Pantanal. In: Seminário sobre uso e conservação do cerrado do Sul de Mato Grosso do Sul, 5; Feira de sementes nativas e crioulas e de produtos agroecológicos, 12, Juti. Anais... Dourados: UFGD.

- Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA). 2020. Agriculture and environmental preservation: an analysis of the rural environmental registry. Campinas. Available online: www.embrapa.br/ca (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Farias, M. H. C. S., Beltrão, N. E. S., Santos, C. A., Cordeiro, Y. E. M. 2028. Impact of Rural Settlements on the Deforestation of the Amazon. Mercator, 17, 1–20.

- Folz, R. R., & Martucci, R. 2013. Minimum housing: discussion of the minimum area standard applied to social housing units. Revista Tópos, 1(1), 23–40.

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). 2019. Agricultural Census 2017: Final results. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. 105p. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/periodicos/3096/agro_2017_resultados_definitivos.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA). 2022. Normative Instruction nº 129, de 15 de dezembro de 2022. Provides for administrative procedures for the creation by the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform - Incra of settlement projects and environmentally differentiated settlement projects. Available online: https://shre.ink/g5Jx (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA). 2020. A. Infrastructure. 28 jan. 2020. Available online: http://www.incra.gov.br/pt/infraestrutura-atuacao.html (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Lannes, L. S., & Soares, G. F. 2014. Saneamento Básico e Assentamento Rural – Um Estudo de Caso do Assentamento Zumbi dos Palmares, RJ. Biológicas & Saúde, 4(13), 44-58.

- Leopold, L. B. 1971. Leopold Matrix. Washington: U.S. Geologican Survey.

- Molch, C. O., Simplício, L. C., & Pinheiro, A. S. F. 2022. Aspect of basic sanitation in the Lower Amazon. Delos: Desarrollo Local Sostenible, 12(35), 1-10.

- Nascimento, R. L. X.; et al. 2022. Characterization notebook: State of Pará. Brasília- DF: Codevasf. 146 p.

- Pereira Júnior, M., Ismail, I. A. L., Silveira, K. A., & Abrantes, A. C. T. G. 2023. Groundwater contamination by rudimentary pits. Caderno Progressus, Curitiba, 3(5), 40-47.

- Schneider, M., & Peres, C. A. 2015. Environmental costs of government-sponsored agrarian settlements in Brazilian Amazonia. PloS one, 10(8), e0134016.

- Silva, V. A. 2019. Agroextractive Settlement Project Eixo Forte in Santarém – PA: history, concepts and reality. 158f. Dissertation (Master’s) – Federal University of Western Pará, Interdisciplinary Postgraduate Studies in Society, Environment and Quality of Life.

- Souza, M. L., & Alencar, A. S. 2020. Sustainable Settlements in the Amazon: Family Farming and Environmental Sustainability in the World’s Largest Tropical Forest. Amazon Environmental Research Institute, Brasília. 176p.

- Topanotti, V. P. 2022. Study of the Environmental Impacts of Urban Invasions in Cuiabá – MT. 176p. Dissertation (Master in Environmental Engineering). Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro.

- Venere, P. C.; et al. (2024). Socioeconomic and environmental atlas of Agrarian Reform settlements in Mato Grosso and Pará. [S. I.: s. n].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).