Submitted:

05 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

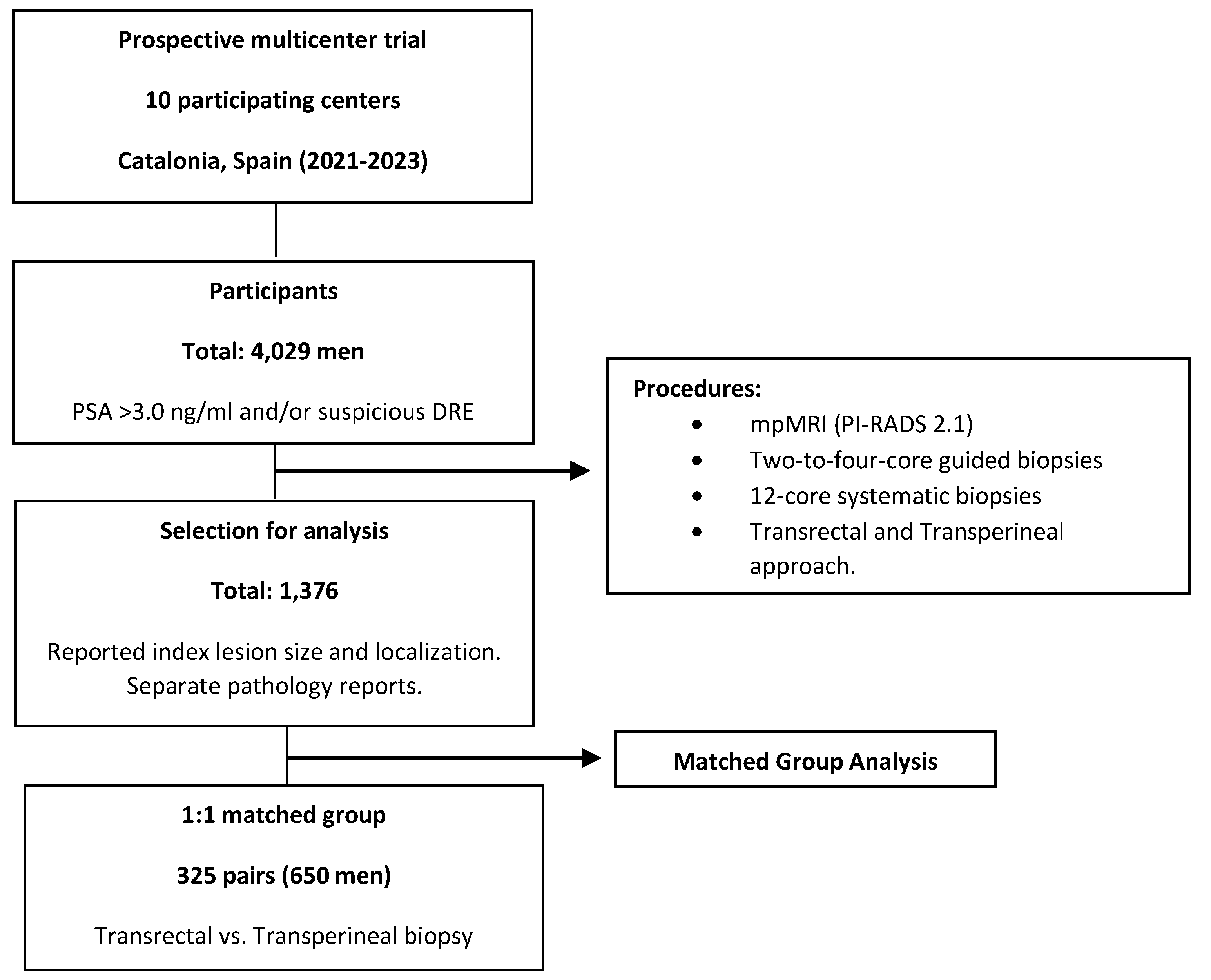

Objective: To compare the efficacy of transrectal and transperineal prostate-guided biopsies to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) index lesions in detecting clinically significant prostate cancer (csPCa), and to evaluate the role of systematic biopsies. Methods: This prospective and multicenter trial, conducted in the early detection program of csPCa of Catalonia (Spain) between 2021 and 2023, involved 4,029 men suspected of ha-ving PCa who underwent multiparametric MRI followed by guided and systematic biopsies. From this cohort, 1,376 men with reported size and localization of index lesions were selected. A matched group of 325 pairs of men subjected to transrectal and transperineal biopsy was chosen to account for confounding variables. We compared csPCa detection rates at index lesions and systematic biopsies, as well as by lesion localization. Results: Transperineal and transrectal biopsies detected csPCa in 49.5% vs. 40.6% overall (p = 0.027), 44.6% vs. 30.8% at index lesions (p = 0.001), and 24.3% vs. 35.1% at systematic biopsies (p = 0.003). CsPCa detection rates were higher in transperineal biopsies across all index lesion localizations, with significant increases in anterior zone (47.8% vs. 20.8% at mid-base, p = 0.039; 52.9% vs. 24.2% at apex, p = 0.024) and central zone (33.3% vs. 5.9%, p = 0.003). CsPCa detected only in systematic biopsies was 10.5% in transrectal biopsies and 4.9% in transperineal biopsies (p = 0.012). Conclusions: Targeted biopsies via the transperineal route showed higher csPCa detection rates than transrectal biopsies, parti-cularly for anterior and apical lesions, with systematic biopsies showing reduced utility.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Setting, and Participants

2.2. PCa Diagnostic Approach

2.3. Variables in the Study

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Cohort Study

3.2. Binary Logistic Regression for Searching Independent Predictive Variables of csPCa, Selection of a Matched Group to Avoid Confounders, and Characteristics of Paired Groups

3.3. Overall Efficacy of Systematic Biopsies According to the Prostate Biopsy Route

3.4. Overall Efficacy of Guided Biopsies to the Index Lesion According to the Biopsy Route and Localizations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Equal Contribution as Last Authors

Abbreviations

| PCa | Prostate Cancer |

| csPCa | Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer |

| iPCa | Insignificant Prostate Cancer |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| TRB | Transrectal Biopsy |

| TPB | Transperineal Biopsy |

| PSA | Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| PI-RADS | Prostate Imaging-Reporting and Data System |

| DRE | Digital Rectal Examination |

| mpMRI | Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| ISUP-GG | International Society of Urologic Pathology Grade Groups |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| START | Standards of Reporting for MRI-Targeted Biopsy Studies |

References

- Siegel, R.; Miller, K.; Wagle, N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guide de Cancer Early Diagnosis. [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254500/9789241511940-eng.pdf?

- Pepe, P.; Garufi, A.; Priolo, G.; Pennisi, M. Transperineal Versus Transrectal MRI/TRUS Fusion Targeted.

- Biopsy: Detection Rate of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 2017, 15, 33–36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derin, O.; Fonseca, L.; Sanchez-Salas, R.; Roberts, M. Infectious complications of prostate biopsy: winning battles but not war. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 2743–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacewicz, M.; Günzel, K.; Rud, E.; Sandbæk, G. ; MegheliA; Busch, J. ; et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis in transperineal prostate biopsies (NORAPP): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar]

- Mottet, N.; van den Bergh, R.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck De Santis, M.; Lam, T.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO- ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer—2020 update. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.; Vellekoop, A.; Ahmed, H.; Catto, J.; Emberton, M.; Nam, R.; et al. Systematic review of complications of prostate biopsy. Eur Urol. 2013, 64, 876–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grummet, J.; Gorin, M.; Popert, R.; Lamb, A.; Moore, C.; Briers, E.; et al. “TREXIT 2020”: why the time to abandon transrectal prostate biopsy starts now. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020, 23, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanova, V.; Buckley, R.; Flax, S.; Hajek, D.; Tunis, A.; Lai, E.; et al. Transperineal Prostate Biopsies Using Local Anesthesia: Experience with 1,287 Patients. Prostate Cancer Detection Rate, Complications and Patient Tolerability. J. Urol. 2019, 201, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashima, R.; Egawa, S.; Kuwao, S.; Baba, S. Anterior distribution of Stage T1c nonpalpable tumors in radical prostatectomy specimens. Urology. 2002, 59, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Ellis, W. Improved prostate cancer detection with anterior apical prostate biopsies. Urol. Oncol. 2006, 24, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.; Yamamoto, H.; Eddy, B.; Kommu, S.; Omer, A.; Leslie, T.; et al. Protocol for the TRANSLATE prospective, multicentre, randomised clinical trial of prostate biopsy technique. BJU Int. 2023, 131, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paesano, N.; Catalá, V.; Tcholakian, L.; Alomar, X.; Trilla, E.; Morote, J.; et al. The effectiveness of mapping-targeted biopsies on the index lesion in transperineal prostate biopsies. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2024, 50, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkbey, B.; Rosenkrantz, A.; Haider, H.; Padhani, A.; Villeirs, G.; Macura, K.; et al. Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2.1: 2019 Update of Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, J.; Zelefsky, M.; Sjoberg, D.; Nelson, J.; Egevad, L.; Vickers, A.; et al. A Contemporary Prostate Cancer Grading System: A Validated Alternative to the Gleason Score. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.M.; Kasivisvanathan, V.; Gill, I.S.; Emberton, M.; Klotz, L.; Simon, R.; et al. Standards of reporting for MRI-targeted biopsy studies (START) of the prostate: recommendations from an International Working Group. Eur. Urol. 2013, 64, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petov, V.; Azilgareeva, C.; Shpikina, A.; Morozov, A.; Kozlov, V.; Rodler, S.; et al. Robot-Assisted Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Targeted versus Systematic Prostate Biopsy; Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.C.; Assel, M.; Allaf, M.E.; et al. Transperineal Versus Transrectal Magnetic Resonance Imaging-targeted and Systematic Prostate Biopsy to Prevent Infectious Complications: The PREVENT Randomized Trial. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, B.; Mayerhofer, C.; Somani, B.; Kallidonis, P.; Nagele Udo Tokas, T. Magnetic Resonance Imaging/Ultrasound Fusion-guided Transperineal Versus Magnetic Resonance Imaging/Ultrasound Fusion-guided Transrectal Prostate Biopsy-A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2021, 4, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zattoni, F.; Marra, G.; Kasivisvanathan, V.; Grummet, J.; Olivier, J.; Moon, D.; et al. The Detection of Prostate Cancer with Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Targeted Prostate Biopsies is Superior with the Transperineal vs the Transrectal Approach. A European Association of Urology-Young Academic Urologists Prostate Cancer Working Group Multi-Institutional Study. J. Urol. 2022, 208, 830–837. [Google Scholar]

- Koparal, M.; Sözen, T.; Karşıyakalı, N.; Aslan, G.; Akdoğan, B.; Şahin, B.; et al. Comparison of transperineal and transrectal targeted prostate biopsy using Mahalanobis distance matching within propensity score caliper method: A multicenter study of Turkish Urooncology Association. Prostate. 2022, 82, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamand, R.; Guenzel, K.; Mjaess, G.; Lefebvre, Y.; Ferriero, M.; Simone, G.; et al. Transperineal or Transrectal Magnetic Resonance Imaging-targeted Biopsy for Prostate Cancer Detection. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, M.; Medina, L.; Lenon, M.; Aron, M.; Gill, I.; Abreu, A.; et al. Transperineal vs transrectal magnetic resonance and ultrasound image fusion prostate biopsy: a pair-matched comparison. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morote, J.; Picola, N.; Muñoz-Rodriguez, J.; Paesano, N.; Celma, A.; Servian, P.; et al. A Diagnostic Accuracy Study of Targeted and Systematic Biopsies to Detect Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer, including a Model for the Partial Omission of Systematic Biopsies. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15, 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.; El-Shater Bosaily, A.; Brown, L.; Gabe, R.; Kaplan, R.; Parmar, M.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (Promis): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet. 2017, 389, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasivisvanathan, V.; Rannikko, A.S.; Borghi, M.; Panebianco, V.; Vaarala, M.; Briganti, A.; et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy for Prostate-Cancer Diagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1767–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouvière, O.; Puech, P.; Renard-Penna, R.; Claudon, M.; Roy, C.; Colombel, M.; et al. Use of prostate systematic and targeted biopsy on the basis of multiparametric MRI in biopsy-naive patients (MRI-FIRST): A prospective, multicentre, paired diagnostic study. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 20, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhoury, F.; Felker, E.; Kwan, L.; Sisk, A.; Delfin, M.; Marks, L.; et al. Comparison of Targeted vs. Systematic Prostate Biopsy in Men Who Are Biopsy Naive: The Prospective Assessment of Image Registration in the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer (PAIREDCAP) Study. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugosson, J.; Månsson, M.; Wallström, J.; Axcrona, U.; Carlsson, S.; Egevad, L.; et al. Prostate cancer screening with PSA and MRI followed by targeted biopsy only. N Engl. J.Med. 2022, 387, 2126–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uleri, A.; Baboudjian, M.; Tedde, A.; Palou, J.; Basile, G.; Briganti, A.; et al. Is There an Impact of Transperineal Versus Transrectal Magnetic Resonance Imaging-targeted Biopsy in Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer Detection Rate? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2023, 6, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Number of men | 1,376 |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 68 (62-73) |

| Serum PSA, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 7.2 (5.3-10.8) |

| Abnormal DRE, n (%) | 344 (25.0) |

| Repeated prostate biopsy, n (%) | 377 (27.4) |

| PCa family history, n (%) | 149 (10.8) |

| Prostate volume, cc, median (IQR) | 52 (38-73) |

| PSA density, ng/ml/cc, median (IQR) | 0.14 (0.09-0.13) |

| 3 Tesla mpMRI, n (%) | 638 (46.4) |

| Suspicious lesions, n (%) | |

| 1 2 |

1,376 (100) |

| 2 | 329 (23.9) |

| 3 | 52 (3.8) |

| Index lesion PI-RADS score, n (%) | |

| 2 |

355 (15.1) |

| 3 |

449 (20.3) |

| 4 | 960 (43.3) |

| 5 | 468 (21.7) |

| Index lesion length, mm, median (IQR) | 11 (0.7-15) |

| Postero-anterior index lesion localization, n (%) | |

| Peripheral zone | 891 (64.8) |

| Central/transitional zone | 196 (14.2) |

| Anterior (fibromuscular) zone | 289 (21.0) |

| Craniocaudal index lesion localization, n (%) | |

| Mid-Base | 815 (59.2) |

| Apex | 561 (40.8) |

| Software image TRUS-MRI fusion biopsy, n (%) | 767 (55.7) |

| Transperineal route, n (%) | 823 (59.8) |

| Overall PCa detection, n (%) | 867 (63.0) |

| sPCa | 652 (47.4) |

| iPCa | 215 (15.6) |

| PCa detected at index lesion biopsy, n (%) | 749 (54.4) |

| sPCa | 568 (41.3) |

| iPCa | 180 (13.1) |

| PCa detected at systematic biopsies, n (%) | 662 (48.1) |

| sPCa | 408 (29.7) |

| iPCa | 254 (18.5) |

| Predictive variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, Ref. one year | 1.054 (1,035-1.073) - |

< 0.001 |

| Serum PSA, Ref. one ng/mL | 1.035 (1.013-1.057) | 0.001 |

| DRE, Ref. normal | 1.581 (1.152-2.170) | 0.005 |

| Type of biopsy, Ref. initial | 0.627 (0.460-0.857) | 0.003 |

| PCa family history, Ref. no | 1.472 (0.952-2.275) | 0.082 |

| Prostate volume, Ref. one mL | 0.978 (0.972-0.983) | < 0.001 |

| Tesla, Ref. 1.5 | 1.296 (1.221-2.728) | < 0.001 |

| Number of suspicious lesions, Ref. 1 | 1.021 (0.943-1.167) | 0.671 |

| Length of index lesion, Ref. one mm | 1.003 (0.981-1.026) | 0.783 |

| PI-RADS score of index lesion, Ref. 2 | 3.938 (3.201-4.845) | < 0.001 |

| Postero-anterior localization of index lesion, Ref. PZ | 0,888 (0.777-1.015) | 0.081 |

| Craniocaudal localization of index lesion, Ref, mid-base | 0.907 (0.804-1.022) | 0.110 |

| Type of guided biopsy, Ref. software | 1.911 (1.439-2.539) | < 0.001 |

| Characteristic | Transrectal | Transperineal | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of men | 325 | 325 | - |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 67 (62-73) | 67 (63-72) | 1.000 |

| Serum PSA, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 6.9 (4.9-9.6) | 6.9 (5.2-9.9) | 0.998 |

| Abnormal DRE, n (%) | 65 (20.0) | 68 (20.0) | 1.000 |

| Repeated prostate biopsy, n (%) | 89 (27.4) | 86 (26.5) | 0.754 |

| PCa family history, n (%) | 39 (12.0) | 43 (13.2) | 0.838 |

| Prostate volume, cc, median (IQR) | 50 (38-68) | 50 (38-68) | 1.000 |

| PSA density, ng/ml/cc, median (IQR) | 0.14 (0.10-0.14) | 0.14 (0.10-0.13) | 0.999 |

| 3 Tesla mpMRI, n (%) | 169 (52.0) | 164 (50.5) | 0.892 |

| Suspicious lesions, n (%) | |||

| 1 2 |

375(100) | 375 (100) | 1.000 |

| 2 | 81 (21.6) | 87 (23.2) | 0.894 |

| 3 | 14 (3.7) | 16 (4.3) | 0.905 |

| Index lesion PI-RADS score, n (%) | |||

| 2 |

3 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) | 1.000 |

| 3 |

72 (22-2) | 72 (22-2) | 1.000 |

| 4 | 193 (59.4) | 193 (59.4) | 1.000 |

| 5 | 57 (15.5) | 57 (15.5) | 1.000 |

| Index lesion length, mm, median (IQR) | 10 (0.7-14) | 10 (7-14) | 1.000 |

| Posteroanterior index lesion localization, n (%) | |||

| Peripheral zone | 213 (49.2) | 220 (50.8) | 0.793 |

| Central (central and transitional) zone | 69 (21.2) | 33 (10.2) | 0.032 |

| Anterior (fibromuscular) zone | 43 (13.2) | 72 (22.2) | 0.028 |

| Craniocaudal index lesion localization, n (%) | |||

| Mid-base | 156 (48.0) | 206 (63.4) | < 0.001 |

| Apex | 169 (52.0) | 119 (36.6) | < 0.001 |

| Software image TRUS-MRI fusion biopsy, n (%) | 164 (49.2) | 158 (48.6) | 0.897 |

| Overall PCa detection, n (%) | 190 (58.5) | 218 (67.1) | 0.028 |

| sPCa | 132 (40.6) | 161 (49.5) | 0.027 |

| iPCa | 58 (17.8) | 57 (17.5) | 0.997 |

| PCa detected at index lesion biopsy, n (%) | 140 (43.1) | 200 (61.5) | < 0.001 |

| sPCa | 100 (30.8) | 145 (44.6) | < 0.001 |

| iPCa | 39 (12.0) | 55 (16.9) | 0.094 |

| PCa detected at systematic biopsies, n (%) | 172 (52.9) | 156 (48.0) | 0.239 |

| sPCa | 114 (35.1) | 79 (24.3) | 0.003 |

| iPCa | 58 (17.8) | 77 (23.7) | 0.082 |

| Type of PCa | Systematic biopsies | Targeted biopsies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR route (n = 325) | TP route (n = 325) |

p Value | TR route (n = 325) |

TP route (n = 325) |

p Value | |

| csPCa, n (%) | 144 (35.1) | 79 (24.3) | 0.003 | 100 (30.8) | 145 (44.6) | < 0.001 |

| iPCa, n (%) | 58 (17.8) | 77 (23.7) | 0.082 | 39 (12.0) | 55 (16.9) | 0.094 |

| Overall PCa, n (%) | 172 (52.9) | 156 (48.0) | 0.239 | 140 (43.1) | 200 (61.5) | < 0.001 |

| Localization of index lesion |

csPCa detection | Transrectal | Transperineal | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PZ-MB, n (%) | 102/217 (47.0) | 36/81 (44.4) | 66/136 (48.5) | 0.577 |

| CZ-MB, n (%) | 11/75 (14.7) | 3/51 (5.9) | 8/24 (33.3) | 0.003 |

| AZ-MB, n (%) | 27/70 (38.6) | 5/24 (20.8) | 22/46(47.8) | 0.039 |

| PZ-AP, n (%) | 79/221 (35.7) | 48/136 (35.3) | 31/85 (36.5) | 0.886 |

| AZ-AP, n (%) | 26/67 (37.7) | 8/33 (24.2) | 18/34 (52.9) | 0.024 |

| All localizations, n (%) | 245/650 (37.7) | 100/325 (30.8) | 145/325 (44.6) | > 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).