Introduction

Solid dispersions is one of the most active techniques to increase the solubility of poorly soluble medications. Sekiguchi and Obi introduced the initial account of solid dispersions in 1961 [

1]. Solid dispersion is a significant strategy for circumventing the dissolving rate restrictions on absorption of poorly soluble medicines. The formula of improperly soluble compounds as solid dispersions may lead to reduced particle size, optimized wetting, reduced agglomeration, variability in the physical situation of the drug particles, and potentially a dispersion at the molecular level, depending on the physical state of the solid dispersion. Solid dispersion is a grouping of solid goods having at least two distinct parts, frequently a hydrophilic substrate and a hydrophobic drug. The matrix may be crystalline or uncrystalline [

1,

2]. The medications might be distributed molecularly as crystalline or uncrystalline particles (clusters). The solid-state structures of solid dispersions as well as the type of transporter utilized are used to categorize them in a number of different ways. It is important to categorize different solid dispersion systems according to their fast release mechanisms [

3].

Classification of Solid Dispersions

Despite being studied for more than 50 years, the use of solid dispersion technology in drug progress has only recently been more significant as a result of the extensive use of combinatorial chemistry and High-throughput screening in drug innovation, which has favored the emergence of novel chemical entities that are poorly water-soluble [

4].

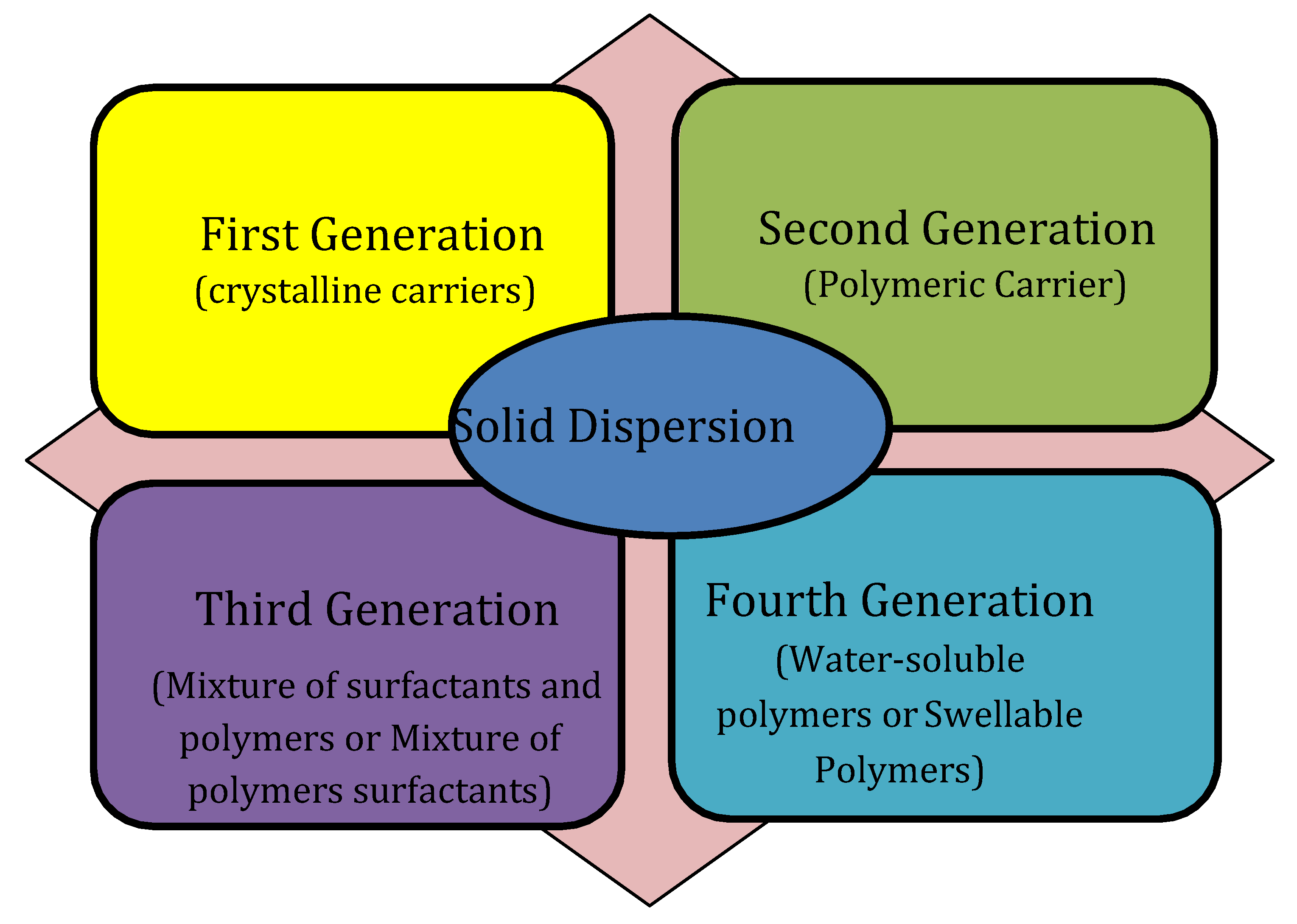

Different criteria can be used to classify solid dispersions. Based on their molecular composition, solid dispersions may be categorized into five sets: glass solutions, solid solutions, uncrystalline solid solutions, glass dispersions, and eutectic mixes. A different method of classifying solid dispersions depends on the complexity of these systems and the knowledge development. Solid dispersion is classified into 1

st, 2

nd, 3

rd, and 4

th generation as presented in

Figure 1. Additionally, it displays the many substances that were employed in the production of the four generations of solid dispersion as drug transporters [

5].

First-Generation Solid Dispersions

Sekiguchi and Obi developed the first solid dispersion for use in pharmaceutical applications by employing urea as a transporter to create eutectic mixture with sulfathiazole [

6]. A mixture of two or more components called eutectic mixture results in a system which hardens at a lesser temperature than any of its constituent parts, although the components do not mix to form a different structure. The process of rapidly cooling a melting mixture of the constituents is the one most usually utilized to create eutectic mixtures. These manufactured solid eutectic combinations frequently comprise tiny crystalline particles of medicines with poor water solubility embedded in hydrophilic transporters. Hence, the decrease in particle size and the incorporation of the drug within a hydrophilic polymeric transporter have an influence on how a medication manufactured from this combination dissolves. This served as the rationale for using solid dispersions to enhance drug absorption. This idea led to the investigation of several polymer matrices as potential transporters.

Mannitol was used as a transporter in solid dispersions in 1963 when the medication was present as a molecular combination [

7]. In several experiments published over the course of two years by Goldberg

et al., it has been shown that molecular dispersions may enhance the solubility and rate of dissolution of medications [

8].

Second-Generation Solid Dispersions

In order to create 2

nd generation solid dispersions, uncrystalline materials with irregular short kind order were used as transporters. In particular, the used polymeric transporters were capable to spread drug particles at the molecular level due to the uneven dispersion of their polymeric chains. Amorphous solid solutions (glass solution) are a formulation in which a glassy substance serves as a solid solvent. The inclusion of an uncrystalline polymer with an elevated Tg is beneficial in expressions of dissolution and solubility because it provides the amorphous solid solutions and the molecular shape of a chilled solution at extreme temperature with elevated viscidness [

9].

The 2

nd generation solid dispersions is able to separate into uncrystalline solid solutions and uncrystalline solid suspensions, or a mixture of both, depending on the medication physical status [

10]. In the case of uncrystalline solid solutions, the transporter and the medication interact to produce a molecularly homogeneous admixture. Alternatively, uncrystalline solid suspensions are dispersions that contain both an uncrystalline medication and an uncrystalline transporter. This is a result of either their limited miscibility or the matrix being supersaturated with the medication [

11]. The drug solubilization in the matrix polymers is involuntary with high concentration in both glass solutions and uncrystalline suspensions (e.g., by HME [

12] or lyophilization [

13]), causing a supersaturation status that has a drawback of high affinity to recrystallization if cooled afterward treating or throughout storing. The polymeric transporter should be extremely miscible with the drug so as to prevent recrystallization throughout drug release or storage [

14]. The method that is most frequently used to assess how miscible medicines and polymers are is thermal analysis [

13]. Even though there have been many research on how to estimate drug-polymer solubility and miscibility, there are certain issues with the techniques that are presently in use [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Third-Generation Solid Dispersions

Third-generation solid dispersions were created by integrating polymers with surfactant capabilities or a combination of uncrystalline polymers and surfactants by advancements in the development of this pharmaceutical sector [

21,

22]. These solid dispersions are created to stop morphological changes during administration and storage and to obtain the highest solubility. The third-generation solid dispersions are uncrystalline, much like the second generation, but the surfactant nature of the transporters enabled an improvement in the solid dispersions' behavior by accelerating dissolution, making them more stable, and lowering precipitation below supersaturation [

23].

The most popular surfactants are Inulin Lauryl Carbamate, Lauroyl polyoxyl-32 glycerides, Glyceryl Dibehenate, Pluronic® and Lutrol®, etc. Tocofersolan, sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) sucrose laurate, Tween 80, and other emulsifiers and surfactants have also been used as additives in SDs [

23]. It has been demonstrated that using the transporters Inulin Lauryl Carbamate, Lauroyl polyoxyl-32 glycerides, Glyceryl Dibehenate, Pluronic® can provide high polymorphism purity and improve

in vivo bioavailability [

5,

24].

Fourth-Generation Solid Dispersions

4

th generation solid dispersions enhance the solubility of the weakly water soluble medicine as delaying the drug liberation in the dissolving media because they utilize water-insoluble or swellable polymers [

10]. The advantages of these dispersions include increased patient compliance owing to a reduction in dose incidence, a reduction in the occurrence of adverse effects, and a prolonged therapeutic impact for medications that are not very water soluble. With fourth-generation solid dispersions, the medication can be delivered by diffusion or erosion. Fourth-generation solid dispersions may be made using polymers including Eudragit RS, Eudragit RL, ethyl cellulose, Hydroxypropylcellulose, polyethylene oxide, Soluplus ®, and carboxyvinyl polymer (Carbopol ®). Guo

et al. prepared berberine hydrochloride SDs using this technique and the solvent evaporation method with Eudragit S100 as the transporter. The solid dispersions characterization led to an optimization of the drug to polymer ratio to 1:4. According to the outcomes of

in vitro cytotoxicity experiments, the interaction between berberine hydrochloride and Eudragit RS 100 formed an uncrystalline complex with a lesser IC 50 than free berberine HCL. The scientists claim that the solid dispersion boosted berberine HCL's effectiveness, offering the framework for more investigation into berberine HCL as a promising new option for treatment and prophylaxis of the colon cancer [

25].

Factors Influencing SDs in Drug Development

Hygroscopicity of the uncrystalline drug can be changed by polymers, which also prevents nucleation and crystallization. In contrast, they facilitate to realize and sustain the oversaturation status, and interfaces among a medication and a polymer may furthermore aid to reinforce the stability of a solid dispersion by giving mechanical stiffness throughout an increase in the (Tg). To create a successful formulation strategy, it is essential to have a thorough identification of the molecular and thermodynamic properties of solid dispersions, including (Tg), thermal stability, fragility, devitrification kinetics, molecular mobility, chemical interactions, profiles of dissolution in organic solvents, and an ideal drug solubilization in the solid dispersion. The characteristics of the transporter unquestionably play a substantial role in how soon the medicine dissolves. A more water- soluble polymer will cause the drug to be released from the solid dispersion matrix more quickly, whereas a less water-soluble or insoluble polymer will cause the drug to be released more slowly. Nevertheless, a transporter must also possess additional desired qualities, such as staying thermostable with a squat melting point if the combination method is chosen, or existing pharmacologically inert, non-toxic, and chemical consistence with the drug besides of being soluble in a variation of solvents [

26].

It is important to remember that in order to yield a steady and efficient oral solid dosage, the solid dispersion itself entails extra processing steps and formulation. A crucial first objective is to yield a solid dispersion with the least quantity of polymer possible so that the necessary drug dose and polymer mixture is not excessive and has little bearing on the unit size, which in turn has little bearing on the kind and amount of other excipients entailed to confirm proper manufacturing and performance. The amount of polymer must be kept to a minimum to avoid losing the polymer's principal function as a crystallization inhibitor for the solid situation and solvent mediated crystallization. In order to operate effectively, a solid dispersion must first develop a single phase “miscible" system. The same thermodynamic laws that apply to liquid-liquid mixtures also apply to solid-solid mixtures. To choose the best drug-polymer combination, it is essential to take into account the component concentration, their interactivity, their shape and molecular size, and their polarity degree [

27].

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) were used in the earliest polymer-based solid dispersions methods. The primary polymers that are utilized to create solid dispersions are either acid-containing enteric coating polymers that ionize at higher pH levels to turn out to be water soluble, or they can be soluble in water at all pH levels. Despite the wide range of materials that are accessible, preferable polymers are often those that have a history of being safe in other pharmaceutical applications and that can also stabilize the drug's solid state and sustain supersaturation in a liquid form. Therefore, the most widely marketed solid dispersion products (

Table 1) include povidones like cellulosic polymers as hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HPMC), or PVP [

28].

Drug Release from SDs

The nature of the drug distributed in the matrix and the transporter polymer affects how complex mechanism of the drug release from solid dispersions [

29]. The creation of a biorelevant

in-vitro dissolution method is thereby made considerably more challenging. The correlation between

in-vitro and

in-vivo experiments is difficult to establish due to the variety of physiological parameters and dosage forms. For scientific and regulatory purposes, the dissolution test is a standardized method for evaluating the degree of solubilization or liberation of a medicine from solid dosage forms. Understanding and controlling this rate is essential once drug liberation is the step that limits absorption rate and medicinal effect since changes in this rate might cause differences in the bioavailable and safe or effective concerns. The dissolution test enables evaluation of the formulation's key characteristics (active ingredient and excipients), as well as the manufacturing process and physicochemical alterations that occur when a pharmaceutical product is stored, ages, or is stressed. The solubility features and behavior of the transporter affect the drug's

in vitro dissolving ability in formulations including uncrystalline solid dispersions. Polymer characteristics including type, weight of molecules, particle pores, and wetting ability can be used to control medication release. The simulated stomach or mimicked intestinal fluid, which has the lowest solubility capacity for the medication, or perhaps filtered water as a substitute, can be used as the dissolution medium in dissolving research to examine the size of the released drug's particle size. However, the performance of the

in-vivo can be connected to the formulation concentration and the drugs released particle size even if the medicine wouldn't dissolve in such a dissolution media.

Fernandez-Colino'

et al. proposed an innovative model and later confirmed by Romero

et al., which may incorporate both diffusional and polymer relaxation stages involved in the process of drug release. Poloxamer 407 was used as the transporter to suit experimental data collected from the dissolution patterns of solid dispersions of Albendazole and Benznidazole. This method produced good correlation coefficients (R

2 > 0.90), allowing for the quick estimation of a number of parameters with pharmaceutical relevance [

30,

31,

32].

A model was proposed by Craig to describe the drug release activity from the solid dispersion taking into account that it may be controlled by the drug or the transporter after carefully reviewing the theories of the transporter and drug-controlled dissolution of solid dispersions [

29]. Between the dissolution solvent and the solid dispersion, a diffusion layer rich in polymers forms to start the process. The drug passes into this polymer-rich region initially. When the transporter mediates the dissolution, it then diffuses into the dissolving liquid at a pace decided by the transporter either as solvated molecules or as uncrystalline particles. Contrarily, when the drug controls the dissolution rate and the drug dissolves immediately via spreading from the dispersion to the solution medium at a speed depending on the aqueous solubility of the drug, the high solubility of the transporter in the dissolution medium prevents the formation of the polymer-rich phase.

Advantages of Solid Dispersions

Solid dispersion was frequently used to improve the water solubility of medications that were not very water soluble and had the following benefits [

33]:

- [1]

Drugs that interact with water-soluble transporters can speed up absorption and increase bioavailability by reducing aggregation and releasing in a supersaturation situation [

23].

- [2]

Solid dispersion can increase the surface area and increase the wettability of medicines, enhancing their aqueous solubility.

- [3]

Compared to other forms, including liquid goods, solid dispersion could be created in the form of a solid oral dosage, making it more practical for patients.

- [4]

Additionally, solid dispersion outperformed co-crystallization, salt formulation, and other techniques. For instance, cationic or anionic ionized active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are included in salt formulations. These formulations are common in the pharmaceutical industry since there are several methods to build them such that they have the desired pharmacological properties. The phase of the dissociation or stability issue is intrinsic in salt generation or co-crystallization because not all the drugs can ionize with all cations or anions. Better regulatory inspection for sturdy acid salts derived from alkyl alcohols; decreased solubility and dissolution rate; decreased relative bioavailability (common ions effect for HCl salts); and increased hygroscopicity; for example, spray-drying/lyophilization can isolate strong acid salts for Na+ and K+ salts. The problems could be avoided by using solid dispersion to make salt formulation.

- [5]

Practically speaking, total absorption is required for medications to dissolve before they may have the intended therapeutic impact when taken orally. The majority of anticancer medications have poor water solubility, which results in low bioavailability and considerable blood concentration variability. Solid dispersion, a method that encourages supersaturated drug dissolution and, as a result, increases in vivo absorption, can help with the limiting of drug dissolution.

Disadvantages of Solid Dispersions

The solid dispersion is a useful method to improve both the solubility and the bioavailability of hydrophobic drugs, but there are some disadvantages as follows [

33]:

- (1)

As solid dispersions age, their crystallinity changes and their rate of disintegration slows down.

- (2)

Solid dispersion is temperature and humidity sensitive during storage due to its thermodynamic instability. By raising general molecular mobility, lowering the transition glass temperature (Tg), or interference with interacting between the drug and the transporter, these components may encourage separation of phases and crystalline formation of solid dispersion, which lowers the drug's ability to dissolve and dissolving rate.

- (3)

Cancer patients should continue taking anticancer medications while receiving treatment. However, the quality and efficacy of medications may be impacted by the instability of solid dispersion during storage.

Methods for Solid Dispersion Preparation

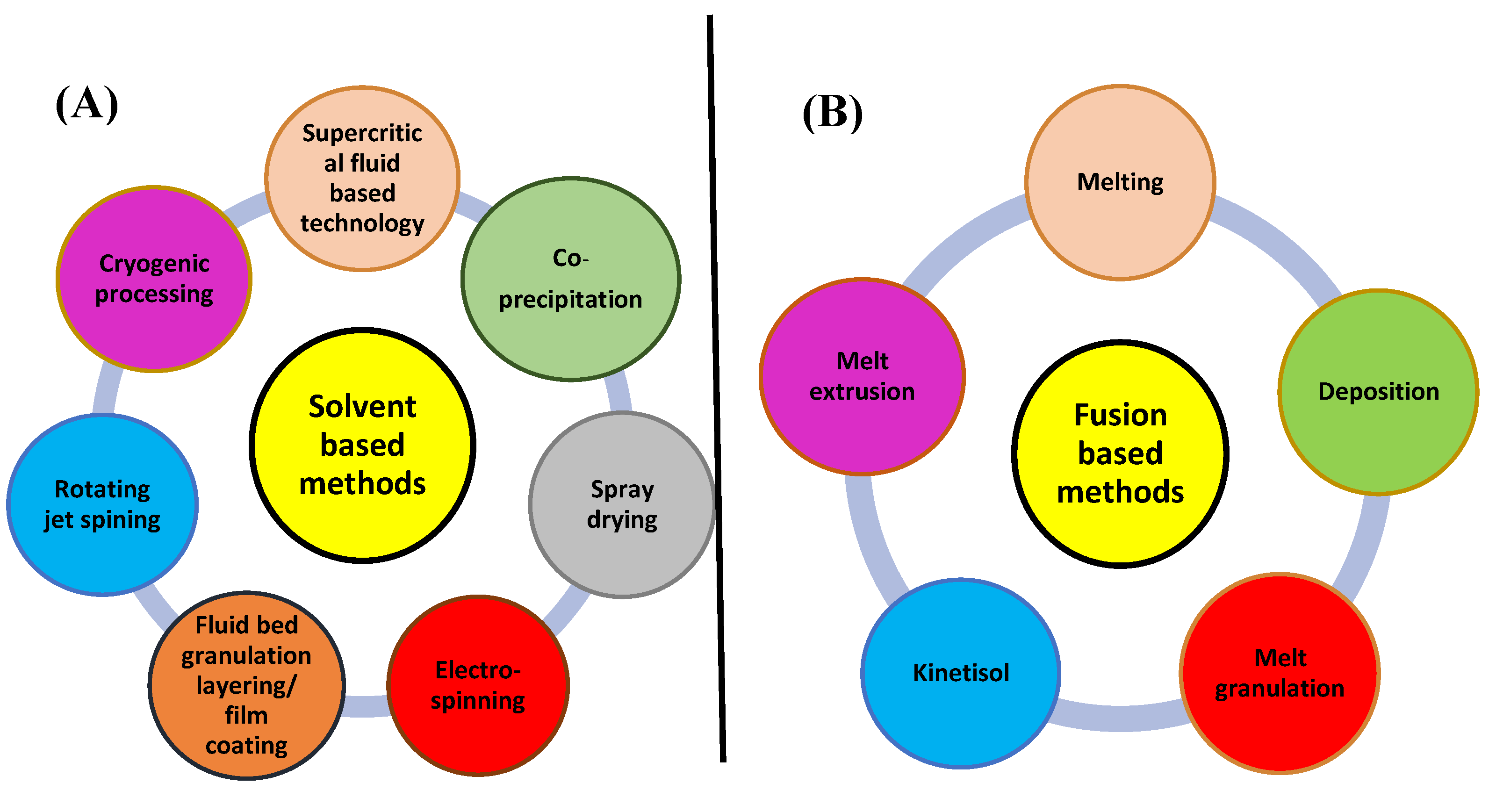

According to Serajuddin [

34], the necessity for appropriate manufacturing methods to be used for commercial production is one of the major obstacles in developing the solid dispersions. Over the past ten years, solid dispersions have attracted a lot of interest, and a variety of approaches have become available for manufacture on a large scale. Solvent evaporation and melt extrusion are the two procedures for creating solid dispersions that are most frequently discussed in the literature (fusion-based method).

Figure 2 depicts a plan outlining the many possibilities used in these techniques.

Despite the facts that spray drying is still a vital technology and the method of solvent evaporation that has received the most research attention, hot-melt extrusion (HME) has had significant commercial success to be at the top of the list of technological advancements. This is mainly clarified by the distinctive profits of the HME process, containing its capacity to work continuously, modularity, solvent-free nature, and ability to make products that are practically complete.

Melting Methods

Pharmaceutical manufacturing is progressively focusing on the rapidity and effectiveness of consistent processing over batch processing, so melting processes have a number of benefits, like having less costly compared with evaporated solvent techniques, having smaller machinery steps, avoiding the need for solvents, as well as being together at a single point in a continuous process [

35,

36]. On the other hand, in order to use this strategy, a few restrictions must be taken into consideration. The medication must first demonstrate enough thermostability at the process temperature in addition to being miscible with the co-melting polymer. Notably, the polymer must be chosen taking into account its thermostability. A nonhomogeneous product could develop from phase separation if the medicine and the transporter are incompatible. This issue might also arise when cooling [

23].

Additionally, during the melting process, the medication is either solubilized or disseminated in the molten polymer, stabilizing the uncrystalline state. In this process, the drug and transporter should be molten together in temperature higher than their eutectic point, and then the homogenous mixture must be cooled and solidified. Sieving and grinding create a solid out of the finished product. The homogenous admixture could be inserted into dosages rather than ground previous to cooling [

37]. Dissolving the drug in the already melted transporter is another way to modify the fusion method to lower the process's temperature [

5]. Several methods can be used to cool and harden the melted mix, including agitating in a bath of ice, passing on a thin layer of refrigerated stainless steel, placing the samples in a desiccator, dipping in liquid nitrogen, dispersing on plates covered in dry ice, and freezing spray [

35,

38,

39]. Some alternatives were put forth to get over this method's drawbacks, including HME, Meltrex TM and liquefy agglomeration, Melt-Dose ®, and Lidose ® [

40,

41,

42]. Pharmacies employ extrusion technology to encourage oral absorption, delayed elease, and targeted release. Extrusion technology is utilized extensively in the polymer and food sectors [

43,

44].

One or more medications and at least one molten excipient is combined using an extruder in the continuous melt-fabrication method known as HME to produce an extruded product, also referred to as an HME product. The medication might be either crystalline or uncrystalline [

45]. This process involves mixing the drug and transporter before they are heated, melted, homogenized, and extruded into bars, pills, or grains, or they are crushed and mixed with additional excipients. Thanks to vigorous mixing and forced agitation by the revolving nail, the drug molecules in the polymer's molten state entirely dissolve, resulting in a uniform dispersion [

10]. Using polymers including PVP, HPMC, polymethacrylate polymers, the polymer of Ethylene Oxide PEO, and HPMC-AS, solid dispersions were effectively made during HME while keeping in mind that transporters should be chosen, so they are not reduced at such high temperature and weights.

Two processes that use this adaptation have received patent protection: Lidose ® by SMB laboratory and MeltDose ® by Lifecycle Pharma A/S. The uniqueness of the MeltDose ® technology lies in the use of a patented nozzle to spray an active drug in the molten transporter, reducing the risk of drug or transporter modification at high temperatures [

34]. The Lidose ® technology, on the opposite side, depends on the delivery system of the drug created by a solid pill that contains both the medication and the transporter, which is melted together and cooled according to predetermined circumstances [

34].

Another unique treatment that makes advantage of the synthesis strategy is Meltrex TM. This method uses a particular matching nail extruder and separate hoppers since the temperature can fluctuate. A high shear mixer is utilized in the melt agglomeration process, and there are various ways to produce the mixture. One approach is to warm the excipients before mixing a molten drug and transporter into the combination. Alternative: Before adding the molten transporter, a medication mixture, the transporter, and the excipients could be heated to a temperature that is approximately equivalent to the melting point of the transporter [

37].

Technique of Solvent Evaporation

Solvent evaporation is one of the most used techniques in the pharmaceutical business for increasing the drug solubility in water. Since the drug and transporter are joint using a solvent rather than heat as in the melting procedure, this method was particularly created for heating unstable elements. Therefore, this technique allows for the employment of transporters with extremely high melting points. This method's central premise is the homogenous mixing of the drug and transporter after they have been dissolved in a volatile solvent. For creating a solid dispersion, the solvent is evaporated while being continuously agitated. Following that, the solid mixes are crushed and separated. In 1965, this technique was used by Tachibana and Nakamura for the first time [

46].

Griseofulvin solid dispersion was created by Mayersohn and Gibaldi in 1966 using chloroform as the solvent and PVP as the transporter [

47]. At a proportion of 1:20 Griseofulvin: PVP, the dissolution of Griseofulvin from the solid dispersion was 11 times higher than that of the pure drug. Azithromycin, tectorigenin, flurbiprofen, cilostazol, ticagelor, piroxicam, indomethacin, loratadine, diclofenac, efavirenz, and repaglinide have all been made more soluble using this technique [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54].

To improve solubility and bioavailability, a solid dispersion of tectorigenin, PVP, and PEG 4000 was created via solvent evaporation [

50]. The

in vitro drug release of the solid dispersion was 4.35 times more than that of the pure drug after 2.5 hours. Additionally, according to AUC (4.8 fold) and Cmax, the oral bioavailability of the medication from the solid dispersion was greater than that of the traditional drug. (13.1 fold). Paclitaxel, docetaxel, and other anticancer drugs with low water solubility have all been made more soluble by the solvent evaporation approach [

55,

56].

For instance, docetaxel's emulsified solid dispersion's solubility and dissolution were found 34.2 and 12.7 times larger, respectively, at 2 hours than the drug's traditional form [

56]. In Adeli's work, azithromycin solid dispersion was made by the solvent evaporation method using a variety of PEG as the transporters, including PEG 4000, PEG 6000, PEG 8000, PEG 12,000, and PEG 20,000 at varied ratios. In comparison to the pure traditional medication, the drug's solubility is increased when PEG is used as the hydrophilic transporter in solid dispersion. The solid dispersion PEG 6000 containing azithromycin produced the greatest results (1:7). After one hour, more than 49% of the azithromycin in the solid dispersion had been discharged [

49].

The key benefit of the solvent technique is that heat degradation of medicines or transporters may be avoided since organic solvents may evaporate at low temperatures. The increased cost of preparation and the challenge of thoroughly eliminating liquid solvent are drawbacks [

57].

Melting Solvent Method (Melt Evaporation)

Goldberg et al. conducted the initial research on the melting solvent approach. They developed a solid dispersion in their study utilizing methanol as the solvent and succinic acid as the transporter to enhance the solubility of griseofulvin [

58]. Melting and solvent evaporation techniques are used in the melting solvent method. The medicine is first dissolved in an appropriate solvent then mixed with the melt transporter before being evaporated to dryness. For medications with a high melting point, this approach is particularly helpful practically. The 10-hydroxycamptothecin (HCPT) solid dispersion tablet was demonstrated by Chen et al. using PEG 6000 as the transporter and Methanol as the solvent. It was made using the melting solvent technique. The drug's cumulative release at 12 hours was above 90%, and the improved formulation delivered HCPT in simulated intestinal fluid for 12 hours at a steady degree of 1.21 mg/h (SIF; pH 6.8) [

59].

Melt Agglomeration Process

A binder serves as a transporter in the process of melt agglomeration. This method includes heating the drug, the binder, and several excipients above the binder's melting point. As an alternative, the medication is scattered over the heated binder in a dispersion [

42,

60,

61,

62]. To enhance the dissolution rate, a diazepam solid dispersion was made using the melt agglomeration method in a high shear mixer. In this preparation, PEG 3000 or Glucire 50/13 was employed to melt agglomerate lactose monohydrate, which served as the binder. This is applied by either pumping on the binder or melting in it. Using melt agglomeration achieved a high dissolving rate at a lower drug concentration. The dissolution degrees for the pump-on and melt-in methods were similar. Additionally, compared to the solid dispersion containing PEG 3000, the diazepam solid dispersion including Glucire 50/13 demonstrated greater solubility.

Hot-Melt Extrusion Method

Poorly water-soluble pharmaceuticals can be made more soluble and more bioavailable orally using the hot-melt extrusion technique. Because the uncrystalline solid dispersion is created without the use of a solvent, no residual solvents are left in the formulation [

63]. In this method, which combines the melting process with an extruder, an identical combination of the drug, the polymer, and the plasticizer is melted, and the mixture is then extruded using the equipment. The last step of grinding is not necessary since the forms of the products at the extruder's outflow may be regulated. To increase the rate at which efavirenz dissolves, Sathigari

et al. developed an efavirenz solid dispersion utilizing the hot melt extrusion technique with either Eudragit EPO or Plasdone S-630 as transporters. Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS) was added to the dissolving media as a result of the extremely low water solubility (3-9 g/mL) observed in the dissolution test. The findings revealed that, compared to the pure form of the drug, the solubility of Efavirenz's greatly improved (to 197 g/mL).

Lyophilization Techniques

The drug and transporter are dissolved in a solvent as an substitute to the solvent evaporation procedure, and the resultant solution is then frozen in liquid nitrogen to generate a lyophilized molecular dispersion [

64]. Items known as thermolabile, which are unstable in water-based solutions but stable in the dry form for long storage durations, are often handled using this technique. In a prior work, PEG 6000 was used as a transporter to construct nifedipine and sulfamethoxazole solid dispersion and to assess their physicochemical and

in vitro features. The two medications' solid dispersions were effectively created, and the pace at which they dissolved was accelerated [

65].

Electrospinning Method

The electrospinning method combines nanotechnology and solid dispersion technologies. In this method, a polymeric fluid stream or melt is fed via a millimeter- scale nozzle to form solid fibers [

66]. The method is useful since it is straightforward and affordable. Making nanofibers and controlling the delivery of biomedical medicines both benefit from this method. A nanofiber made of Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA): Ketoprofen (1:1, w/w) was produced by electro-spinning [

67].

Co-Precipitation

In this procedure, the solvent is first used to dissolve the transporter to create a solution, and the medicine is then stirred in the solution to create identical combination. The identical mixture is then mixed drop-wise with water to create precipitation. The precipitation is then dried and filtered. Sonali et al. used HPMC E15LV as the transporter, and several techniques including manipulation, spray drying, and co-precipitation were used to create a silymarin solid dispersion. When compared to the other two approaches, the co-precipitated silymarin solid dispersion demonstrated considerably (p 0.05) improved solubility. Additionally, compared to the usual medication, the Silymarin solubility from the solid dispersion created by co- precipitation increased by 2.5 times [

68].

Supercritical Fluid (SCF) Technology

Currently, there are several approaches to carry out SCF, including fast extension from supercritical solution (RESS), gas anti-solvent (GAS), and supercritical anti-solvent (SAS). (SEDS) [

49,

69,

70,

71]. To create a solid dispersion, the medicine and transporter are first dissolved in SCF and sprayed through an atomizer into an extension vessel that is kept at a low pressure. The benefit of this procedure is that the amount of organic solvent needed to create the solid dispersion is reduced. Due to its low critical temperature (31.04 °C) and critical pressure (7.38 MPa), absence of toxicity, lack of flammability, and environmental safety, CO

2 is an appropriate solvent for the synthesis of solid dispersion of insoluble medicines in SCF technology [

72].

Advantage of this method is that the drug and matrix quickly become supersaturated, solidify, and form particles in the droplets as the supercritical anti-solvent quickly permeates them. Precipitation with compressed anti-oven is the overall name for this procedure. However to dissolve both the medication and the matrix, which are more expensive, organic solvents like dichloromethane or methanol must be used.

Spray-Drying Technique

Spray drying is one of the earliest techniques for material drying mainly for thermally gentle supplies such as food and medicine. The transporter is dissolved in water to provide the food solution, and the medicine is dissolved in an appropriate solvent. The two solutions are then mixed by sonication or other suitable techniques up to the mixture is transparent. The procedure began with a high-pressure nozzle blasting the feed solutions to produce minuscule droplets in a drying chamber. In the process of forming the droplets, the drying fluid (hot gas) creates nano- or microparticles [

73]. Nilotinib was made into a solid dispersion by spray-drying in research by Herbrink et al. to increase solubility. Based on in vitro dissolving investigations, the optimal transporter was determined to be Soluplus. Contrary to the pure drug, nilotinib’s solubility was 630-fold higher at a drug: Ratio of Soluplus (1:7) [

74].

Kneading Technique

This approach dissolves the transporter in water and turns it into a glue. Then, the drug is added and well combined. The completed dough is dried and, if necessary, passed through a filter. Dhandapani and El-gied previously produced cefixime solid dispersion using the kneading method with -CD as the transporter. Cefixime's rate of dissolution from the solid dispersion was 6.77 times more than that of the pure medicine, which showed a potential development in bioavailability [

75].

Characterization of Solid Dispersion

The following are the main methods for characterizing solid dispersion:

Physical Composition

It comprises surface attributes, surface area analysis, Raman, Atomic force, and scanning electron microscopy [

76].

Drug-Transporter Defeasibility

It consists of different scanning calorimetry, hot phase microscopy, and powder X-ray deflection [

77].

Stability

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (Tg, Temperature recrystallization), investigations of humidity, isothermal calorimetry, and studies of saturated solubility are also included [

77].

Uncrystalline Content

It involves powder X-ray diffraction, DSC, and optical microscopy using polarized light. (MTDSC) [

76].

Dissolution Augmentation

Intrinsic dissolution, dynamic solubility, and dissolution are all included [

34].

Industrial and Laboratory Scale Manufacturing Procedures

Solid dispersions were created using a variety of production techniques. However, not all techniques can be used in business operations. Practically, the solvent evaporation method and the melting method are two separate procedures that are often utilized in lab and commercial settings.

A rotary evaporator was primarily employed on a lab scale for the solvent evaporation procedure to create solid dispersions. SCF and freeze-drying have recently been used as well. The melting procedure is widely utilized since it is straightforward and affordable. The laboratory can now make solid dispersion amounts ranging from a few grams to a kilogram using a variety of equipment types from several manufacturers such as Brabender Technologies, Coperion GmbH, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Leistritz Advanced Technologies Corp.

Production of solid dispersion on an industrial scale includes a lot of products, ranging from a few to several hundred kilograms, thus it is more complicated than it is at the lab size. Additionally, procedures must be reliable, repeatable, and adhere to good manufacturing principles (GMP). For procedures like solvent cast evaporation or water bath melting, they are challenging to guarantee. The methods of solvent evaporation most frequently employed to create solid dispersion are spray-drying and freeze-drying. Additionally, it is simple to scale up the spray-drying procedure from a lab to an industrial level. On an industrial scale, there are two different kinds of melting processes: melt agglomeration and hot melt extrusion. For instance, hot melt extrusion, which employs twin-screw extruders with a high screw diameter (16–50 mm) as opposed to a tiny screw diameter at lab size, is one of the most popular techniques for producing solid dispersion on an industrial scale (11–16 mm).

In conclusion, the success of a formulation is significantly influenced by the production technique used. The parameters for choosing the melting process on the lab scale depend on the melting point and thermal steadiness. Properties of the medication, the transporter, and an organic solvent are vital considerations when choosing the solvent evaporation technique. Solid dispersion can only be produced through a small number of industrial manufacturing techniques. The most popular melting method for making solid dispersion is hot melt extrusion. The selection parameters for the evaporation process depend on solvent toxicity and loading capability [

33].

Development of Poorly Soluble Anticancer Medicines by the Application of Solid Dispersion

Cancer, a collection of illnesses characterized by atypical cell development with the possible to infiltrate or range to other regions of the body, is one of the top causes of mortality in the world. By 2030, the World Health Organization predicts, there will be

23.6 million new cases of cancer annually. An estimated number of 609,640 Americans died of cancer in 2018, out of the 1,735,350 new instances of the disease, or about 1,700 fatalities every day [

78]. As a result, the most significant topics researched during the several past decades are cancer therapy. Drug anticancer must first be absorbed and circulate in order to provide a therapeutic impact. The majority of anticancer medications are best delivered by IV infusion to guarantee full bioavailability since the entire dose will enter the system of circulatory immediately and instantly disperse to its areas of action. Patients are inconvenienced by IV administration, though, because they must travel to the hospital for care. Additionally, a number of negative effects might manifest while receiving therapy. For instance, the pharmaceutical medicine paclitaxel (Taxol), that uses Ethanol and Cremophor EL as solvents (50:50, v/v), has an association with significant negative effects from Cremophor EL, such as acute hyper-sensitivity, myelo-suppression, neutropenia, and neurotoxicity [

79,

80,

81].

Many oral anticancer medication formulations have been created in the recent years. The preferred method of cancer therapy at the moment is oral administration since it is practical, painless, secure, and affordable. Oral dose forms are very simple to travel and keep. Complete and predictable absorption is a requirement for oral delivery. Medicines should dissolve in water so as to be efficiently absorbed in the GI tract and circulatory system. Yet, the poor water solubility of practically all anticancer drugs can lead to partial absorption and limited bioavailability, which can cause a large inter/intra-individual variance in drug concentration

in vivo. Therefore, a major obstacle to creating more effective cancer medicines is increasing the solubility of anticancer medications in the pharmaceutical industry [

82]. Solid dispersion outperforms other techniques such complexion, lipid-based systems, micronization, nanonization, and co-crystals for improving the solubility and Bioavailability of anticancer medicines. The three anticancer medications Vemurafenib (Zelboraf® Roche), Regorafenib (Stivarga® Bayer), and Everolimus (Afinitor®, Votubia®, Certican®, Novartis) were created using solid dispersion technology [

83].

Due to its ease of use, low cost, and excellent performance, solid dispersion technique is still often employed to increase the solubility and bioavailability of anticancer medicines. In contrast to other techniques, the melting technique, solvent evaporation method, SCF technology, and freeze drying are frequently used to create solid dispersion formulations of anticancer medications. The approach can be chosen according to the physicochemical characteristics of anticancer medications [

33].

Solid Herbal Medicine Dispersion

As a sizable amount of the lead compounds or distinctive chemical compounds in the development of the medication were initially identified in herbal sources, herbal or substitute medication is now concerned by current studies in the discovery and development of drug. Aspirin, digoxin, morphine, and paclitaxel are a few examples [

84]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), herbal medicines are completed, labeled goods that include active substances like aerial or subterranean sections of plants, other plant material, or a combination of them, whether in their raw form or as plant preparations [

85]. Since they are made from plants or natural sources, herbal remedies are frequently believed as safer and have less side effects than western or new therapies, which has recently assisted to their rise in reputation [

86].

Herbal remedies have not been widely accepted in the modern medical system because of insufficient quality control of identified active elements, a lack of research and information in this part, technical troubles in analyzing the complex structure of crude plant extracts, and frequent problems with poor bioavailability. As a result, the majority of herbal remedies are now only available as dietary supplements. To promote the acceptance of herbal remedies in conventional therapy, two directions for future development have been proposed: First, the identification, elaboration, and purification of herbal remedies; second, the improvement and standardization of herbal remedies compositions. For the former, World Health Organization has produced recommendations on proper farming practices for medicinal plants because the quality of herbal remedies could be impacted via the raw herbs. To determine the efficacy and safety of herbal products, several methods and tests, such as chemical fingerprinting, are being developed. This review does not go into detail on the historical background or current developments in this field, but you may find that information in other publications [

85,

87,

88].

Historically, the extemporaneous method of developing herbal medicine formulations involves the individual selection of the final administration form (such as liquid extracts and dried herbs) [

86]. Nevertheless, of the caliber of the herbal raw components, differing formulation options may result in distinct medicinal effects. Standardization of formulations is crucial for ensuring reliable efficiency when selling herbal medications. Weak and unpredictable bioavailability is anticipated to remain a prevalent obstacle with numerous herbal actions even after standardized procedures due to their weak aqueous solubilities [

89].

Overcoming the issue of low water solubility and dissolution via formulation methods seems to be a sensible way for showing that herbal medications may reach comparable or even superior therapeutic effects compared with current pharmaceuticals. To this purpose, the formulation of herbal medications with poor water solubility would seem to benefit from the use of un-crystalline solid dispersion. The polyphenol Curcumin, which is resulting from the roots of Curcuma longa Linn, is a notable example of such application. Though being linked to a wide range of pharmacological actions such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, chemo preventive, and anticancer effects, its oral bioavailability is quite limited, which is in part explained by its inability to dissolve in water (10 ng/ml) [

90]. Spray dried Curcumin-PVP solid dispersions with mass ratios of 1: 7 and 1: 10 have been shown to release nearly all of the Curcumin after 30 minutes, whereas the release from the physical combination was only 1.5% to 1.8% [

91]. Similar results were also obtained using a curcumin- Solutol®HS15 solid dispersion in a 1: 10 w/w ratio. The amount of Curcumin that dissolved during the first hour at pH 6.8 was approximately 0%, 10%, and 90% for raw (unformulated) Curcumin, a physical mix, and a solid dispersion, respectively [

92].

Baicalin, a reactive flavonoid that may have therapeutic/protective qualities for treating cancer and other hepatitis-related conditions, has been transformed into a solid dispersion using PVP as the matrix. Results from DSC, PXRD, and AFM revealed that Baicalin was a molecular distributed in the polymer matrix with a molecular size of 2 nm. It was discovered that the rate of Baicalin dissolution from the dispersion was 21.4 and 9.41 times quicker than the rates provided by the physical mixes of pure Baicalin and Baicalin-PVP, respectively [

93].

Practical Limitations in Solid Dispersion Technique [94,95,96]:

- A.

-

Issue with the creation of the dosage form

Bad flow and compressibility: Grinding and sifting are difficult when solid dispersion is present. It also shows poor stability and compressibility. Drug granulation in-situ is used to address this problem.

Pasting the solid dispersion grains to die and punches: Adhering to die and punch was noticed during compression. This obstacle could be resolved by placing tiny pieces of grease-proof paper among the surface of the metal and the granules. The granules and metal surface were therefore not in direct touch.

- B.

-

Issue with production and scalability

Chance of condensation of moisture over solid dispersion during cooling: Moisture can condense above solid dispersion during evaporation. The revolving or surface-moving belt utilized in continually cooling operations can be employed to address this problem.

Reliability of physicochemical parameters: The preparation circumstances, including the heating rate, maximum temperature employed, cooling rate and technique, pulverization process, and size of particles, significantly affect the physicochemical characteristics of solid dispersions.

- C.

Issue related with stability

A drug portion in a solid dispersion made by the hot melt method may still be molecularly dispersed in the transporter. If this percentage is high, phase separation, or the separation of the crystalline and uncrystalline phases, may result. To prevent this, some polymers, such as HPMCAC, HPMC, and PVP, are now used. The polymer delays the drug's crystallization at low humidity and slows the nucleation rate as a preventive mechanism for crystallization, acting as a stabilizer in the production of solid dispersion.

Some Challenges in the Solid Dispersion Development

The solid dispersion offers enormous promise for improving medication absorption and creating formulations with controlled release. Solid dispersions have been studied extensively, but their practical use is quite restricted. Solid dispersion technique can significantly improve the drug's solubility, but sadly, there are currently very few medications created with this technology that have been commercialized [

97].

The solid dispersion's commercial applicability is constrained by its time-consuming and expensive preparation procedure, reproducible physiochemical characteristics, preparation into dosage forms, scaling-up of production procedures, and physical and chemical stability of the medication and vehicle.

There are some challenges required for in-depth research such as failure of developing the solid dosage formulation from small-scale melt quench or a solvent-evaporation technique, misunderstanding of the in vitro-in vivo relationship between these dosage forms, lack of knowing the way of drug dissolution from the dosage form, the avoidance of some drugs' crystallization in gastric fluids [

94,

98].

Novel Technologies Associated with Solid Dispersions

The major emphasis of recent research on solid dispersions is the utilization of new polymers and scalable production methods. The goal is to make insoluble and high melting point medications more soluble and bioavailable by creating molecular dispersion using specially created polymers. Instead, Enose A et al. improved the solubility of telmisartan, a drug that is only slightly soluble in water, using the amphiphillic polymer Soluplus (Polyvinyl Caprolactam-polyvinyl Acetate-PEG Graft Copolymer). By using DSC and powder X-Ray diffractometry to characterize the synthesized solid dipersions, it was discovered that they were stable and had a larger drug release than free drug did [

99]. Nevertheless, Zawar et al. explored a new microwave induced solid dispersion technique which is effective, solvent-free, and better manufacturing to current techniques to successfully improve the solubility of a drug that is only moderately water soluble [

100]. In a recent study, Singh et al. shown that employing natural polymers is more successful than using synthetic polymers for increasing medication solubility. The results were more accurately evaluated by measuring the generated dispersions' particle size with a particle size analyzer. It was discovered that these dispersions were nanometric in size and had the highest solubility when locust bean gum was used as a transporter [

101].

Research is being done to assess the application of solid dispersions in numerous other disciplines, in addition to improving the solubility of medications that aren't very soluble. In their work, Usmanova

et al. used PEG as a polymer to create magnetically effective solid dispersions for efficient and focused administration of Phenacetin [

102]. Using atomic force and magnetic force microscopy, the creation of the solid dispersion made of the super-magnetic nanoparticles in a polymeric matrix was verified. As it combines the benefits of greater solubility and tailored delivery, this may be more efficient [

102]. To make nano solid dispersions, Duarte et al. still created a unique solvent controlled precipitation process based on micro-fluidization. They produced crystalline and uncrystalline nano solid dispersions, and it was shown that they had faster dissolving rates and higher bioavailability than micron-sized un-crystalline powder. They came to the conclusion that, in the case of solid dispersions, the amorphization of the medication has a less significant impact than the decrease of particle size into the nanometric range [

103]. By utilizing these cutting-edge procedures, it has been possible to overcome the commonly described process for increasing the solubility of crystalline drugs, the idea of amorphization. Similar to this, it was demonstrated in a study done while solid carvedilol dispersions were being made that it is not necessary to change a crystalline medication into an uncrystalline state in order to increase its solubility. However, utilizing innovative surface attached spray-dried solid dispersion technique; we may change the hydrophobic medication into a hydrophilic form without modifying the crystalline shape by attaching the hydrophilic transporters to the drug's surface. The resulting solid dispersions' drug solubility and dissolution rate were found to be 11,500-fold and two times larger, respectively [

104].

Potential for Solid Dispersion in the Future

Low bioavailability is caused by drug solubility in aqueous solutions, which has a important impact on the rate of drug dissolution and bioavailability after oral delivery. One of the most challenging areas of drug research continues to be improving the solubility of these medications. Over time, a number of devices have been created to increase medication solubility and dissolution. The most efficient way to increase the medication solubility and bioavailability that are poorly soluble in water is presently thought to be solid dispersion. The number of commercial solid dispersion products on market could be constrained by problems with the preparation, stability, and storage formulation of the drug, but clinical use of solid dispersion products is still steadily rising thanks to better manufacturing processes and transporters that address the aforementioned issues.

It may be employed in industry trials as well as bench and lab settings for the effective manufacture of solid dispersions. Solid dispersions have risen to the top of pharmaceutical research due to the rise in poorly soluble drug candidates and the major advancements achieved in solid dispersion production techniques in recent years. In spite of many challenges that must be overcome include scaling up and production costs, solid-state dissolution technology offers a significant promise for improving the drug release profile of poorly water-soluble medications.

Despite their many benefits, sulfated dispersions have not been widely used in marketable dosage forms for pharmaceuticals with low water solubility due to manufacturing, reproducibility, formulation, storage, and stability problems. Recent years have seen successively successful advances of solid-state detection systems for preclinical, clinical, and commercial usage. This has been made feasible by the accessibility of surface-active and self-emulsifying transporters with relatively low melting temperatures. Drugs are dissolved in melted caramel during the production of dosage forms, and the heated solutions are then put into gelatin capsules. Due to the intrinsic characteristics of the production and storage processes, it is predicted that the physicochemical properties would vary dramatically during storage. As a result, the need for solid dosage solutions to address challenging bioavailability difficulties is driven by the expectation that the market for poorly water-soluble pharmaceuticals would expand quickly [

57].

Transporters that are utilized to create solid dispersion have been developed recently. For the creation of solid dispersion formulations, some research employed brand-new transporters, while others used more than one transporter. Numerous efficient techniques were developed, recrystallization was reduced, and the stability of solid dispersion was increased by using more than one transporter in the formulation of solid dispersion. Recently, transporters including Inulin®, Gelucire®, Pluronic®, and Soluplus® have been utilized.

Without the use of external heating sources, kinetic and thermal energy are combined throughout the production process to process the drug and transporter to generate solid dispersions. This is done by using a series of fast revolving blades. An innovative high- energy mixing procedure is called kinetosol dispersing (KSD). This inspires renewed optimism for the creation of future more substantial dispersion items.

Conclusion

The evolution of solid dispersion technologies has significantly contributed to overcoming the challenges associated with poorly soluble drugs. Each generation of solid dispersions has introduced innovative carriers and methods that enhance drug solubility, dissolution rates, and bioavailability. Fourth-generation solid dispersions, in particular, offer promising solutions for controlled drug release and improved therapeutic outcomes. The continuous advancements in this field underscore the importance of selecting appropriate carriers and manufacturing techniques to achieve optimal drug performance. Future research should focus on further refining these technologies and exploring their applications in a broader range of therapeutic areas, particularly in the development of effective treatments for complex diseases such as cancer.

References

- Wadke, D.A.; Serajuddin, A.T.M.; Jacobson, H. Preformulation testing. Pharm Dos forms Tablets. 1989, 1, 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S.; Jain, D.; Shukla, S.B.; Yadav, P.; Sonkar, N.; Soloman, J.A. Role of Modular in Effective Drug Delivery System: A Review. Res J Pharm Dos Forms Technol. 2010, 2, 370–373. [Google Scholar]

- Pawar, S.R.; Barhate, S.D. Solubility enhancement (Solid Dispersions) novel boon to increase bioavailability. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2019, 9, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudipeddi, M.; Serajuddin, A.T.M.; Shah, A.V.; Mufson, D. Integrated drug product development: From lead candidate selection to life-cycle management. In: Drug Discovery and Development, Third Edition. CRC Press; 2019. p. 223–61.

- Vasconcelos, T.; Sarmento, B.; Costa, P. Solid dispersions as strategy to improve oral bioavailability of poor water soluble drugs. Drug Discov Today. 2007, 12, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekiguchi, K.; Obi, N. Studies on Absorption of Eutectic Mixture. I. A Comparison of the Behavior of Eutectic Mixture of Sulfathiazole and that of Ordinary Sulfathiazole in Man. Chem Pharm Bull. 1961, 9, 866–872. [Google Scholar]

- LEVYG Effect of particle size on dissolution and gastrointestinal absorption rates of pharmaceuticals. Am J Pharm Sci Support Public Health. 1963, 135, 78–92.

- Patel, R.D.; Raval, M.K.; Sheth, N.R. Formation of Diacerein− fumaric acid eutectic as a multi-component system for the functionality enhancement. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020, 58, 101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Mooter, G. The use of amorphous solid dispersions: A formulation strategy to overcome poor solubility and dissolution rate. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2012, 9, e79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.K.; Dhote, V.; Bhargava, A.; Jain, D.K.; Mishra, P.K. Amorphous solid dispersion technique for improved drug delivery: basics to clinical applications. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2015, 5, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemula, V.R.; Lagishetty, V.; Lingala, S. Solubility enhancement techniques. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2010, 5, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, S.; Belton, P.; Nollenberger, K.; Clayden, N.; Reading, M.; Craig, D.Q.M. Characterisation and prediction of phase separation in hot-melt extruded solid dispersions: A thermal, microscopic and NMR relaxometry study. Pharm Res. 2010, 27, 1869–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasanthavada, M.; Tong, W.Q.; Joshi, Y.; Kislalioglu, M.S. Phase behavior of amorphous molecular dispersions I: Determination of the degree and mechanism of solid solubility. Pharm Res. 2004, 21, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konno, H.; Handa, T.; Alonzo, D.E.; Taylor, L.S. Effect of polymer type on the dissolution profile of amorphous solid dispersions containing felodipine. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008, 70, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Inbar, P.; Chokshi, H.P.; Malick, A.W.; Choi, D.S. Prediction of the thermal phase diagram of amorphous solid dispersions by flory-huggins theory. J Pharm Sci. 2011, 100, 3196–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsac, P.J.; Li, T.; Taylor, L.S. Estimation of drug-polymer miscibility and solubility in amorphous solid dispersions using experimentally determined interaction parameters. Pharm Res. 2009, 26, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumondor, A.C.F.; Ivanisevic, I.; Bates, S.; Alonzo, D.E.; Taylor, L.S. Evaluation of drug-polymer miscibility in amorphous solid dispersion systems. Pharm Res. 2009, 26, 2523–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.E.; Tao, J.; Zhang, G.G.Z.; Yu, L. Solubilities of crystalline drugs in polymers: An improved analytical method and comparison of solubilities of indomethacin and nifedipine in PVP, PVP/VA, and PVAc. J Pharm Sci. 2010, 99, 4023–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Huang, Y. A thermal analysis method to predict the complete phase diagram of drug-polymer solid dispersions. Int J Pharm. 2010, 399, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian F, Huang J, Zhu Q, Haddadin R, Gawel J, Garmise R, et al. Is a distinctive single Tg a reliable indicator for the homogeneity of amorphous solid dispersion? Int J Pharm. 2010, 395, 232–235.

- Dannenfelser, R.M.; He, H.; Joshi, Y.; Bateman, S.; Serajuddin, A.T.M. Development of Clinical Dosage Forms for a Poorly Water Soluble Drug I: Application of Polyethylene Glycol-Polysorbate 80 Solid Dispersion Carrier System. J Pharm Sci. 2004, 93, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebremeskel, A.N.; Vemavarapu, C.; Lodaya, M. Use of surfactants as plasticizers in preparing solid dispersions of poorly soluble API: Selection of polymer-surfactant combinations using solubility parameters and testing the processability. Int J Pharm. 2007, 328, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, C.L.N.; Park, C.; Lee, B.J. Current trends and future perspectives of solid dispersions containing poorly water-soluble drugs. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013, 85, 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, B.; Kaur, R.; Kour, S.; Behl, H.; Kour, S. Solid dispersion: an evolutionary approach for solubility enhancement of poorly water soluble drugs. Int J Recent Adv Pharm Res. 2012, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Wang, G.; Wu, T.; Bai, F.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X. Solid dispersion of berberine hydrochloride and Eudragit® S100: Formulation, physicochemical characterization and cytotoxicity evaluation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2017, 40, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.V.; Popovich, N.G.; Ansel, H.C. Ansel’s pharmaceutical dosage forms and drug delivery systems: Ninth edition. Ansel’s Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms and Drug Delivery Systems: Ninth Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. 1–710 p.

- Zografi, G.; Newman, A. Interrelationships Between Structure and the Properties of Amorphous Solids of Pharmaceutical Interest. J Pharm Sci. 2017, 106, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, A.G.; Simonazzi, A.; Palma, S.D.; Bermúdez, J.M. Solid dispersion technology as a strategy to improve the bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs. Ther Deliv. 2019, 10, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, D.Q.M. The mechanisms of drug release from solid dispersions in water-soluble polymers. Int J Pharm. 2002, 231, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Colino, A.; Bermudez, J.M.; Arias, F.J.; Quinteros, D.; Gonzo, E. Development of a mechanism and an accurate and simple mathematical model for the description of drug release: Application to a relevant example of acetazolamide-controlled release from a bio-inspired elastin-based hydrogel. Mater Sci Eng C. 2016, 61, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.I.; Villegas, M.; Cid, A.G.; Parentis, M.L.; Gonzo, E.E.; Bermúdez, J.M. Validation of kinetic modeling of progesterone release from polymeric membranes. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2018, 13, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonazzi, A.; Davies, C.; Cid, A.G.; Gonzo, E.; Parada, L.; Bermúdez, J.M. Preparation and Characterization of Poloxamer 407 Solid Dispersions as an Alternative Strategy to Improve Benznidazole Bioperformance. J Pharm Sci. 2018, 107, 2829–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.; Pyo, Y.C.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, J.K.; Park, J.S. Overview of the manufacturing methods of solid dispersion technology for improving the solubility of poorly water-soluble drugs and application to anticancer drugs. Pharmaceutics. 2019, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwossabi, A.M.; Elamin, E.S.; Ahmed, E.M.M.; Abdelrahman, M. Solubility enhancement of some poorly soluble drugs by solid dispersion using Ziziphus spina-christi gum polymer: Solubility enhancement of some poorly soluble drugs by solid dispersion. Saudi Pharm J [Internet]. 2022, 30, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaber, S.D.; Gerogiorgis, D.I.; Ramachandran, R.; Evans, J.M.B.; Barton, P.I.; Trout, B.L. Economic analysis of integrated continuous and batch pharmaceutical manufacturing: A case study. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2011, 50, 10083–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurter, Patricia, Thomas, Hayden, Nadig, David, Emiabata-Smith, David, Paone A. Implementing Continuous Manufacturing to Streamline and Accelerate Drug Development. AAPS Newsmag. 2013, 16, 15–19.

- Hallouard, F.; Mehenni, L.; Lahiani-Skiba, M.; Anouar, Y.; Skiba, M. Solid Dispersions for Oral Administration: An Overview of the Methods for their Preparation. Curr Pharm Des. 2016, 22, 4942–4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bley, H.; Fussnegger, B.; Bodmeier, R. Characterization and stability of solid dispersions based on PEG/polymer blends. Int J Pharm. 2010, 390, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.W.; Bai, T.C.; Sun, J.P.; Zhu, C.W.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.L. Thermodynamic properties for the system of silybin and poly(ethylene glycol) 6000. Thermochim Acta. 2005, 437, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, D.; Potter, C.B.; Walker, G.M.; Higginbotham, C.L. Investigation of Ethylene Oxide-co-propylene Oxide for Dissolution Enhancement of Hot-Melt Extruded Solid Dispersions. J Pharm Sci. 2018, 107, 1372–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenbach, J. Melt extrusion: from process to drug delivery technology. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2002, 54, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, A.; Holm, P.; Kristensen, H.G.; Schæfer, T. The preparation of agglomerates containing solid dispersions of diazepam by melt agglomeration in a high shear mixer. Int J Pharm. 2003, 259, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, M.M.; Zhang, F.; Repka, M.A.; Thumma, S.; Upadhye, S.B.; Battu, S.K.; et al. Pharmaceutical applications of hot-melt extrusion: Part, I. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2007, 33, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.P.; Jones, D.S.; Diak, O.A.; McCoy, C.P.; Watts, A.B.; McGinity, J.W. The manufacture and characterisation of hot-melt extruded enteric tablets. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008, 69, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, D.B. Plastic compounding equipment and processing. Vol. 14, IEEE Electrical Insulation Magazine. Hanser Publishers; 1998. 40 p.

- Tachibana, T.; Nakamura, A. A methode for preparing an aqueous colloidal dispersion of organic materials by using water-soluble polymers: Dispersion of Β-carotene by polyvinylpyrrolidone. Kolloid-Zeitschrift Zeitschrift für Polym. 1965, 203, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayersohn, M.; Gibaldi, M. New method of solid-state dispersion for increasing dissolution rates. J Pharm Sci. 1966, 55, 1323–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira V da S, Dantas ED, Queiroz AT de S, Oliveira JW de F, da Silva M de S, Ferreira PG, et al. Novel solid dispersions of naphthoquinone using different polymers for improvement of antichagasic activity. Pharmaceutics. 2020, 12, 1–15.

- Adeli, E. Preparation and evaluation of azithromycin binary solid dispersions using various polyethylene glycols for the improvement of the drug solubility and dissolution rate. Brazilian J Pharm Sci. 2016, 52, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai S, Yue S, Huang Q, Wang W, Yang J, Lan K, et al. Preparation, characterization and in vitro/vivo evaluation of tectorigenin solid dispersion with improved dissolution and bioavailability. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2016, 41, 413–422.

- Daravath, B.; Tadikonda, R.R.; Vemula, S.K. Formulation and pharmacokinetics of gelucire solid dispersions of flurbiprofen. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2015, 41, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha O, Kim KS, Shafique S, Kim DS, Jin SG, Seo YG, et al. Comparison of three different types of cilostazol-loaded solid dispersion: Physicochemical characterization and pharmacokinetics in rats. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2017, 154, 89–95.

- Zhang H, Cui D, Wang B, Han Y-H, Balimane P, Yang Z, et al. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions involving 17α-ethinylestradiol: a new look at an old drug. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2007, 46, 133–57.

- Frizon, F.; de Oliveira Eloy, J.; Donaduzzi, C.M.; Mitsui, M.L.; Marchetti, J.M. Dissolution rate enhancement of loratadine in polyvinylpyrrolidone K-30 solid dispersions by solvent methods. Powder Technol. 2013, 235, 532–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao L, Liang Y, Pan W, Gou J, Yin T, Zhang Y, et al. Effect of supersaturation on the oral bioavailability of paclitaxel/polymer amorphous solid dispersion. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2019, 9, 344–356.

- Chen Y, Shi Q, Chen Z, Zheng J, Xu H, Li J, et al. Preparation and characterization of emulsified solid dispersions containing docetaxel. Arch Pharm Res. 2011, 34, 1909–1917.

- DHILLONV; TYAGIR Solid Dispersion: a Fruitful Approach for Improving the Solubility and Dissolution Rate of Poorly Soluble Drugs. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2012, 2, 5–14.

- Goldberg, A.H.; Gibaldi, M.; Kanig, J.L. Increasing dissolution rates and gastrointestinal absorption of drugs via solid solutions and eutectic mixtures III: Experimental evaluation of griseofulvin—succinic acid solid solution. J Pharm Sci. 1966, 55, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Jiang, G.; Ding, F. Monolithic osmotic tablet containing solid dispersion of 10-hydroxycamptothecin. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2009, 35, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Drooge, D.J.; Hinrichs, W.L.J.; Visser, M.R.; Frijlink, H.W. Characterization of the molecular distribution of drugs in glassy solid dispersions at the nano-meter scale, using differential scanning calorimetry and gravimetric water vapour sorption techniques. Int J Pharm. 2006, 310, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhelmsen, T.; Eliasen, H.; Schæfer, T. Effect of a melt agglomeration process on agglomerates containing solid dispersions. Int J Pharm. 2005, 303, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Aggarwal, G.; Singh, G.; Rana, A.C. Improvement of drug solubility using solid dispersion. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012, 4, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Genina, N.; Hadi, B.; Löbmann, K. Hot Melt Extrusion as Solvent-Free Technique for a Continuous Manufacturing of Drug-Loaded Mesoporous Silica. J Pharm Sci. 2018, 107, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betageri, G.V.; Makarla, K.R. Enhancement of dissolution of glyburide by solid dispersion and lyophilization techniques. Int J Pharm. 1995, 126, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, M.A.; Neau, S.H. Investigation of the in vitro performance difference of drug-Soluplus® and drug-PEG 6000 dispersions when prepared using spray drying or lyophilization. Saudi Pharm J. 2017, 25, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.G.; Li, J.J.; Williams, G.R.; Zhao, M. Electrospun amorphous solid dispersions of poorly water-soluble drugs: A review. J Control Release. 2018, 292, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamudji JS, Khairurrijal, Mauludin R, Sudiati T, Evita M. PVA-ketoprofen nanofibers manufacturing using electrospinning method for dissolution improvement of ketoprofen. In: Materials Science Forum. Trans Tech Publ; 2013. p. 166–75.

- Sonali, D.; Tejal, S.; Vaishali, T.; Tejal, G. Silymarin-solid dispersions: Characterization and influence of preparation methods on dissolution. Acta Pharm. 2010, 60, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, J.; Feng, N. Development and in-vivo assessment of the bioavailability of oridonin solid dispersions by the gas anti-solvent technique. Int J Pharm. 2011, 411, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riekes MK, Caon T, da Silva J, Sordi R, Kuminek G, Bernardi LS, et al. Enhanced hypotensive effect of nimodipine solid dispersions produced by supercritical CO2 drying. Powder Technol. 2015, 278, 204–10.

- Jun SW, Kim M-S, Jo GH, Lee S, Woo JS, Park J-S, et al. Cefuroxime axetil solid dispersions prepared using solution enhanced dispersion by supercritical fluids. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010, 57, 1529–1537.

- Abuzar SM, Hyun SM, Kim JH, Park HJ, Kim MS, Park JS, et al. Enhancing the solubility and bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs using supercritical antisolvent (SAS) process. Int J Pharm. 2018, 538, 1–13.

- Singh, A.; Van den Mooter, G. Spray drying formulation of amorphous solid dispersions. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016, 100, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbrink, M.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Beijnen, J.H.; Nuijen, B. Improving the solubility of nilotinib through novel spray-dried solid dispersions. Int J Pharm. 2017, 529, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandapani, N.V.; El-gied, A.A. Solid dispersions of cefixime using β-cyclodextrin : Characterization and in vitro evaluation. Int J Pharmacol Pharm Sci. 2016, 10, 1523–1527. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Feng, X.; Williams, R.O.; Zhang, F. Characterization of amorphous solid dispersions. J Pharm Investig. 2018, 48, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, M.S.; DiNunzio, J.; Khawaja, N.N.; Crocker, L.S.; Pecora, A. Assessing mixing quality of a copovidone-TPGS hot melt extrusion process with atomic force microscopy and differential scanning calorimetry. Aaps Pharmscitech. 2016, 17, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gornstein, E.L.; Schwarz, T.L. Neurotoxic mechanisms of paclitaxel are local to the distal axon and independent of transport defects. Exp Neurol. 2017, 288, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gréen, H.; Khan, M.S.; Jakobsen-Falk, I.; Åvall-Lundqvist, E.; Peterson, C. Impact of CYP3A5*3 and CYP2C8-HapC on paclitaxel/carboplatin-induced myelosuppression in patients with ovarian cancer. J Pharm Sci. 2011, 100, 4205–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tétu, P.; Hamelin, A.; Moguelet, P.; Barbaud, A.; Soria, A. Management of hypersensitivity reactions to Tocilizumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2018, 48, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanki, K.; Gangwal, R.P.; Sangamwar, A.T.; Jain, S. Oral delivery of anticancer drugs: Challenges and opportunities. J Control Release. 2013, 170, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, E.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Beijnen, J.H.; Nuijen, B. Inventory of oral anticancer agents: Pharmaceutical formulation aspects with focus on the solid dispersion technique. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016, 50, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardi, P.V.; Underwood, J.R. Plant-derived medicines: A novel class of immunological adjuvants. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011, 11, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, N.; Sekhon, B. An overview of advances in the standardization of herbal drugs. J Pharm Educ Res. 2011, 2, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Atmakuri, L.R.; Dathi, S. Available online through Current Trends in Herbal Medicines. J fo Pharm Res. 2010, 3, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, N.P.; Dixit, V.K. Recent approaches in herbal drug standardization. Int J Integr Biol. 2008, 2, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.-Z.; Xie, P.-S.; Chan, K. Chromatographic Fingerprinting and Metabolomics for Quality Control of TCM. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2010, 13, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musthaba, S.M.; Baboota, S.; Ahmed, S.; Ahuja, A.; Ali, J. Status of novel drug delivery technology for phytotherapeutics. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009, 6, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireson C, Orr S, Jones DJL, Verschoyle R, Lim CK, Luo JL, et al. Characterization of metabolites of the chemopreventive agent curcumin in human and rat hepatocytes and in the rat in vivo, and evaluation of their ability to inhibit phorbol ester-induced prostaglandin E2production. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1058–1064.

- Kelloff, G.J.; Boone, C.W.; Crowell, J.A.; Steele, V.E.; Lubet, R.; Sigman, C.C. Chemopreventive Drug Development: Perspectives and Progress. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994, 3, 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, S.W.; Han, H.K.; Chun, M.K.; Choi, H.K. Preparation and pharmacokinetic evaluation of curcumin solid dispersion using Solutol ® HS15 as a carrier. Int J Pharm. 2012, 424, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wen, M.; Li, W.; He, M.; Yang, X.; Li, S. Preparation and characterization of baicalin-poly-vinylpyrrolidone coprecipitate. Int J Pharm. 2011, 408, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serajuddin, A.T.M. Solid dispersion of poorly water-soluble drugs: Early promises, subsequent problems, and recent breakthroughs. J Pharm Sci. 1999, 88, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argade PS, Magar DD, Saudagar RB. 9. Solid Dispersion: Solubility Enhancement Technique for poorly water soluble Drugs. J Adv Pharm Educ Res [Internet]. 2013, 3, 427–439.

- Ramesh, V.; Meenakshi, S. Enhancement of solubility for poorly water soluble drugs by using solid dsipersion technology. Int J Pharm Res Bio-Science. 2016, 5, 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Janssens, S.; Van den Mooter, G. Review: physical chemistry of solid dispersions. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009, 61, 1571–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheen, P.C.; Khetarpal, V.K.; Cariola, C.M.; Rowlings, C.E. Formulation studies of a poorly water-soluble drug in solid dispersions to improve bioavailability. Int J Pharm. 1995, 118, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enose, A.A.; Dasan, P. Formulation, Characterization and Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of Telmisartan Solid Dispersions. J Mol Pharm Org Process Res. 2016, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]