Submitted:

03 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Integrated Online Fantasy Football Platform Promotes Meditation Activity in Male Undergraduate Students: A Self-Determination Theory-Informed Intervention

Online Fantasy Sports as a Platform to Promote Meditation

Applying Self-Determination Theory to Fantasy Sports and Meditation

Materials and Methods

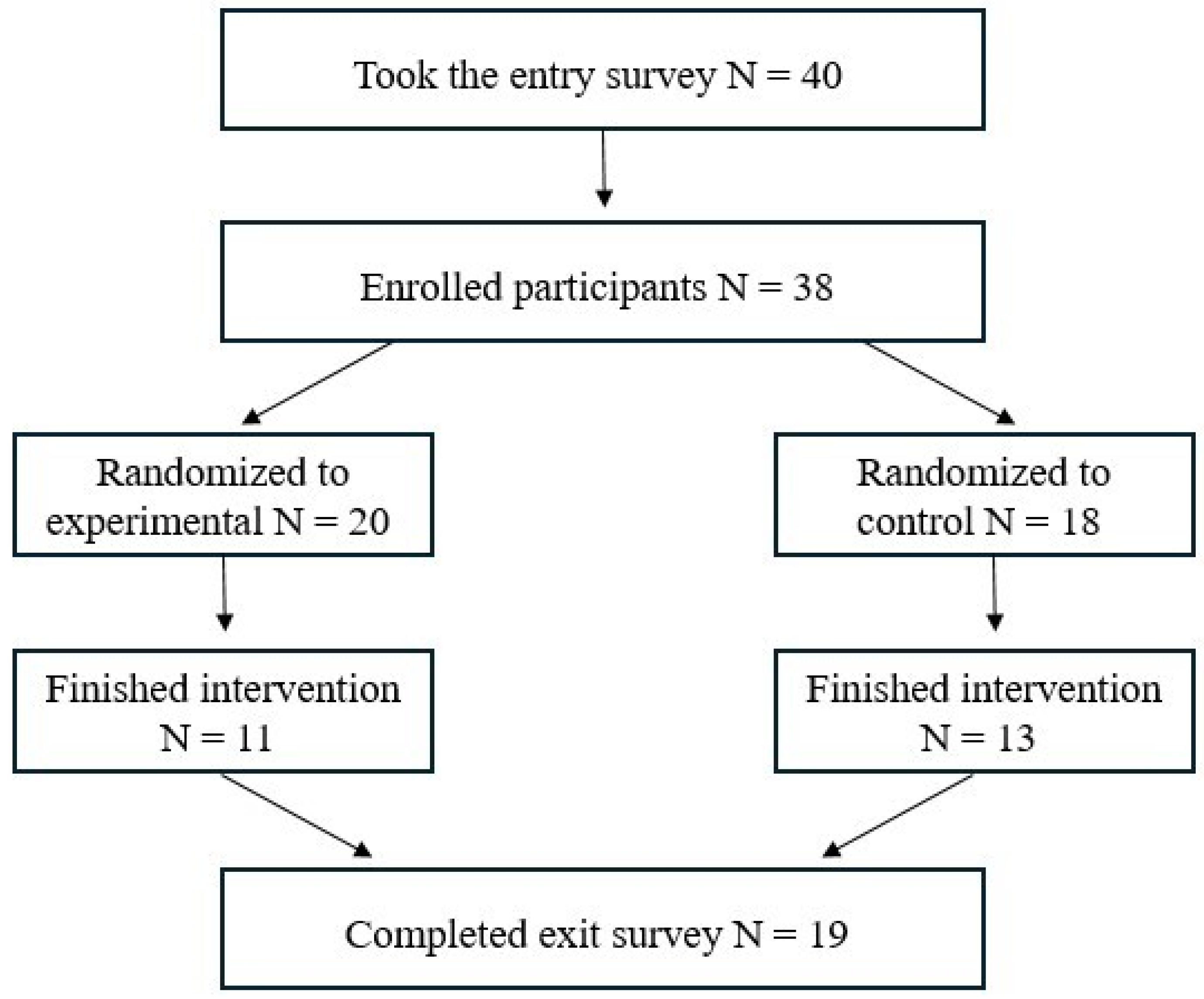

Participants

Materials

Meditation App

Fantasy Sports Platform

Online Group Chat

Pre-Intervention Measures

Post-Intervention Measures

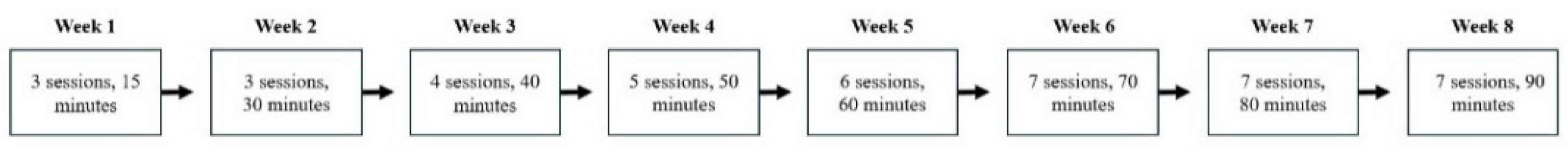

Procedure

Data Analysis Plan

Results

Limitations and Future Directions

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Ethics Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park C, McClure Fuller M, Echevarria TM, Nguyen K, Perez D, Masood H, Alsharif T, Worthen M. A participatory study of college students’ mental health during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2023;11:Article 1116865. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Hegde S, Son C, Keller B, Smith A, Sasangohar F. Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;7(9):Article e22817. [CrossRef]

- Curry D. (2024, January 8). Calm Revenue and Usage Statistics (2024). Business of Apps. Published March 27, 2024. Accessed April 9, 2024. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/calm-statistics/.

- Huberty J, Green J, Glissmann C, Larkey L, Puzia M, Lee C. Efficacy of the mindfulness meditation mobile app “Calm” to reduce stress among college students: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(6):Article e14273. [CrossRef]

- Gál É, Ștefan S, Cristea IA. (2021). The efficacy of mindfulness meditation apps in enhancing users’ well-being and mental health related outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:131–142. [CrossRef]

- Huberty J, Puzia ME, Green J, Vlisides-Henry RD, Larkey L, Irwin MR, Vranceanu AM. A mindfulness meditation mobile app improves depression and anxiety in adults with sleep disturbance: Analysis from a randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;73:30–37. [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Frankenfeld PM, Trautwein F. App-based mindfulness meditation reduces perceived stress and improves self-regulation in working university students: A randomised controlled trial. Appl Psychol: Health Well-Being. 2021;14(4):1151–1171. [CrossRef]

- Fowers R, Berardi V, Huberty J, Stecher C. Using mobile meditation app data to predict future app engagement: an observational study. J Am Med Inform. Assoc. 2022;29(12): 2057–2065. [CrossRef]

- Diller ML, Mascaro J, Haack C, Master V. Adherence patterns and acceptability of a perioperative, app-based mindfulness meditation among surgical patients with chronic pain. Am Surg. 2024;90(5):936–938. [CrossRef]

- Stecher C, Berardi V, Fowers R, Christ J, Chung Y, Huberty J. Identifying app-based meditation habits and the associated mental health benefits: Longitudinal observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(11):e27282. [CrossRef]

- Jiwani Z, Tatar R, Dahl C, Wilson-Mendenhall CD, Hirshberg MJ, Davidson RJ, Goldberg SB. Examining equity in access and utilization of a freely available meditation app. Npj Mental Health Res. 2023;2: Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Lam SU, Xie Q, Goldberg, SB. Situating meditation apps within the ecosystem of meditation practice: Population-based survey study. JMIR Ment Health. 2023;10:Article e43565. [CrossRef]

- Clarke TC, Barnes PM, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Nahin RL. Use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractors among U.S. adults aged 18 and over. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. 2018.

- Milner A, Kavanagh A, King T, Currier D. The influence of masculine norms and occupational factors on mental health: Evidence from the baseline of the Australian longitudinal study on male health. Am J Men’s Health. 2018;12(4):696–705. [CrossRef]

- Ekoh PC, Nnadi F, Nwabineli H, Oluwagbemiga O, Odo C, Okolie TJ, Onuh SC, Ugwu EO, Bhatta K, Onalu C. Barriers to the use of mental health services amongst men in Nigeria and the potential of digital mental health support. Adv Mental Health. 2023:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Opozda MJ, Oxlad M, Turnbull D, Gupta H, Smith JA, Ziesing S, Nakivell ME, Wittert G. Facilitators of, barriers to, and preferences for e-mental health interventions for depression and anxiety in men: Metasynthesis and recommendations. J Affect Disord. 2024;346:75–87. [CrossRef]

- Opozda MJ, Drummond M, Gupta H, Petersen J, Smith JA. E-mental health interventions for men: an urgent call for cohesive Australian policy and investment. Health Promot Int. 2024;39(2):daae033. [CrossRef]

- Moller AC, Majewski S, Standish M, Agarwal P, Podowski A, Carson R, Eyesus B, Shah A, Schneider KL. Active fantasy sports: rationale and feasibility of leveraging online fantasy sports to promote physical activity. JMIR Serious Games. 2014;2(2):Article e13. [CrossRef]

- Keeney J, Schneider KL, Moller AC. Lessons learned during formative phase development of an asynchronous, active video game intervention: Making sedentary fantasy sports active. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019;41:200–210. [CrossRef]

- Barclay P, Bowers C. Feasibility of a meditation video game to reduce anxiety in college students. OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine. 2018;3(4):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Fish MT, Saul AD. The gamification of meditation: A randomized-controlled study of a prescribed mobile mindfulness meditation application in reducing college students’ depression. Simulation & Gaming. 2019;50(4): 419–435. [CrossRef]

- Litvin S, Saunders R, Maier MA, Lüttke S. Gamification as an approach to improve resilience and reduce attrition in mobile mental health interventions: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(9):Article e0237220. [CrossRef]

- Brown M, O’Neill N, van Woerden H, Eslambolchilar P, Jones M, John A. Gamification and adherence to web-based mental health interventions: A systematic review. JMIR Ment Health. 2016;3(3):e39. [CrossRef]

- Duda JL, Appleton PR. Empowering and disempowering coaching climates: Conceptualization, measurement, considerations, and intervention implications. In: Raab M, Wylleman P, Seiler R, Elbe A, Hatzigeorgiadis A, eds. Sport and Exercise Psychology Research: From Theory to Practice. Elsevier Inc.; 2016: 373–388.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P., Wright, C. E., Avishai, A., Villegas, M. E., Lindemans, J. W., Klein, W. M. P., Rothman, A. J., Miles, E., & Ntoumanis, N. (2020). Self-determination theory interventions for health behavior change: Meta-analysis and meta-analytic structural equation modeling of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(8), 1151–1171. [CrossRef]

- Upchurch DM, Johnson PJ. Gender differences in prevalence, patterns, purposes, and perceived benefits of meditation practices in the United States. J Women’s Health. 2019;28(2):135–142. [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Shi H, Shen M, Ni Y, Zhang X, Pang Y, Yu T, Lian X, Yu T, Yang X, Li F. The effects of mhealth-based gamification interventions on participation in physical activity: Systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10(2):Article e27794. [CrossRef]

- Antezana G, Venning A, Smith D, Bidargaddi N. Do young men and women differ in well-being apps usage? Findings from a randomised trial. Health Informatics J. 2022;28(1). [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Fang Y, Frank E, Walton MA, Burmeister M, Tewari A, Dempsey W, NeCamp T, Sen S, Wu Z. Effectiveness of gamified team competition as mHealth intervention for medical interns: a cluster micro-randomized trial. Npj Digit Med. 2023;6(1):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Fantasy Sports & Gaming Association. Industry Demographics. 2024. Accessed April 10, 2024.

- Goldberg SB, Imhoff-Smith T, Bolt DM, Wilson-Mendenhall CD, Dahl CJ, Davidson RJ, Rosenkranz MA. Testing the efficacy of a multicomponent, self-guided, smartphone-based meditation app: Three-armed randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(11):Article e23825. [CrossRef]

- Hirshberg MJ, Frye C, Dahl CJ, Riordan KM, Vack NJ, Sachs J, Goldman R, Davidson RJ, Goldberg SB. A randomized controlled trial of a smartphone-based well-being training in public school system employees during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Educ Psychol. 2022;114(8):1895–1911. [CrossRef]

- Xie Q, Dyer RL, Lam SU, Frye C, Dahl CJ, Quanbeck A, Nahum-Shani I, Davidson RJ, Goldberg SB. Understanding the implementation of informal meditation practice in a smartphone-based intervention: A qualitative analysis. Mindfulness. 2024;15: 479–490. [CrossRef]

- Degenhard SM, Mobile phone mindfulness: Effects of app-based meditation intervention on stress and HRV of undergraduate students. Modern Psychological Studies. 2023;29(1):1.

- Cox CE, Gallis JA, Olsen MK, Porter LS, Gremore T, Greeson JM, Morris C, Moss M, Hough CL. Mobile mindfulness intervention for psychological distress among intensive care unit survivors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Inter Med. 2024;184(7):749–759.

- Wilkins L, Beukes E, Dowsett R, Allen PM. A qualitative exploration of the positive and negative experiences of individuals who play fantasy football. Entertain Comput. 2023;45. [CrossRef]

- Borghouts J, Eikey E, Mark G, De Leon C, Schueller SM, Schneider M, Stadnick N, Zheng K, Mukamel D, Sorkin DH. Barriers to and facilitators of user engagement with digital mental health interventions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e24387. [CrossRef]

- Wilkins L, Dowsett R, Zaborski Z, Scoles L, Allen PM. Exploring the mental health of individuals who play fantasy football. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 2021;3(5):1004–102. [CrossRef]

| Overall Sample | N | % |

| Male-identifying White |

38 33 |

100.00 86.84 |

| Enrolled in an undergraduate program | 37 | 97.36 |

| Previous fantasy sports experience | 29 | 76.31 |

| Previous meditation experience | 12 | 31.58 |

| Participants Who Completed Intervention1 | N | % |

| Male-identifying | 24 | 100.00 |

| White | 19 | 79.97 |

| Enrolled in an undergraduate program | 23 | 95.83 |

| Previous fantasy sports experience | 19 | 79.17 |

| Previous meditation experience | 10 | 41.67 |

| Overall | Exp.b | Con.c | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Knew everyone before starting | 4.85 | 1.18 | 5.67 | 1.32 | 4.20a | 0.42 |

| Cash prizes tied directly to meditation activity | 4.95 | 1.41 | 4.78 | 1.79 | 5.20 | 1.03 |

| Cash prizes tied directly to performance in fantasy sports league | - | - | 6.17 | 1.17 | - | - |

| Playing in a mindful fantasy sports league again with a group of friends | - | - | 5.17 | 2.14 | - | - |

| Playing in a mindful fantasy sports league again with a group of people you didn’t know | - | - | 2.67 | 1.51 | - | - |

| Never | Rarely | Almost Every Week | Several Days per Week | Every Day | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

N 3 1 5 3 |

% | |

| Checked meditation app | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 42 | 7 | 37 | 16 | |

| Checked study GroupMe chat | 1 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 10 | 53 | 5 | 26 | 5 | |

| Messaged group member with third party service (Snapchat, WhatsApp, etc.) |

7 |

37 |

5 |

26 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

26 |

|

| Checked ESPN fantasy app or website | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 50 | 50 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).