1. Introduction

Adopting sophisticated manufacturing technologies has revolutionized production processes, driving industry productivity and market competitiveness [

1]. As manufacturing systems become increasingly automated, digitalized, and intelligent, the digital twin concept has emerged as a cornerstone of intelligent manufacturing [

2]. A digital twin is a high-fidelity virtual representation of a physical system, continuously synchronized with real-time data. This dynamic model replicates its physical counterpart’s behaviour, condition, and interactions, enabling detailed simulations and predictive analytics. The adaptability of digital twins allows them to evolve alongside physical systems, reflecting changes in operations, environments, or configurations [

3]. This capability has positioned digital twins as essential tools for optimizing production processes, diagnosing faults, and enhancing maintenance strategies [

4].

By leveraging these accurate and dynamically adjustable models, digital twins reduce design and maintenance costs while improving manufacturing quality and efficiency [

2]. They bridge the gap between the physical and digital worlds, enabling seamless integration and operational optimization, thus serving as a critical enabler for intelligent manufacturing [

5].

The challenges posed by globalization and digitalization are particularly pronounced in the context of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) [

6]. SMEs are increasingly adopting advanced digital equipment and technologies to remain competitive. However, this transition brings significant complexities, especially in managing real-time operations. These challenges are compounded by limited resources, geographic constraints, and the specialized expertise required to operate and maintain digital systems [

7]. As a result, robust and agile workforce training and technical assistance solutions are essential to address these demands.

1.1. Research Gap and Motivation

Traditional workforce training methods across industries have relied heavily on on-site, hands-on approaches, where trainees engage directly with machinery under supervision [

8]. While effective in ensuring technical proficiency, these methods present several limitations. They are resource-intensive, require physical access to equipment, and lack flexibility and scalability, making them increasingly impractical in modern industrial contexts [

9]. The growing need for cost optimization and environmentally sustainable practices further highlights the limitations of traditional training approaches.

Digital twin (DT) technology offers a transformative solution by enabling the creation of immersive virtual environments that replicate real-world systems [

10]. These environments allow operators to acquire and refine critical skills remotely, eliminating the need for direct access to physical assets [

3]. Digital twins have demonstrated their potential in various industrial contexts, particularly manufacturing and production. For example, Alexopoulos et al. (2020) highlighted their role in enabling supervised machine learning for predictive and operational optimization [

11], while Stavropoulos and Papacharalampopoulos (2022) emphasized their effectiveness in enhancing precision for micromanufacturing processes [

12].

The integration of digital twins into workforce training has also shown promising results. Schneider et al. (2021) introduced a training concept for wafer transportation systems using digital twins, demonstrating significant improvements in skill acquisition [

13]. Similarly, Kaarlela et al. (2020) explored using virtual reality combined with digital twins to improve safety training, emphasizing their ability to create interactive and contextually rich training environments [

14]. Despite these advancements, most existing studies focus on generalized or safety-oriented training frameworks, with limited exploration of tailored approaches for specific industries.

Critical gaps remain in the literature. First, there is a limited understanding of how digital twins can address workforce training challenges for SMEs, which often face financial and technological barriers to adopting advanced solutions [

14]. Second, while digital twins have been extensively studied in production-oriented processes, their application in domain-specific workforce training for industries requiring specialized skills and tools is underexplored [

12]. Lastly, the potential of digital twins to create accessible, scalable, and cost-effective training solutions remains untapped mainly, particularly for industries undergoing digital transformation [

10].

This study seeks to address these gaps by proposing a Digital Twin Framework for Workforce Training (DT4WFT) tailored to the unique needs of SMEs. Using the ornamental stone industry as a representative case [

15], this research explores how digital twins can bridge the limitations of traditional training methods and meet sector-specific requirements. By leveraging the adaptability and scalability of digital twins, the proposed framework aims to create immersive and interactive training environments that enhance workforce capabilities, streamline training processes, and support SMEs in achieving key performance outcomes.

1.2. Research Objective

This research aims to bridge the gap in digital twin applications for workforce training in SMEs by designing a DT4WFT specifically tailored to the ornamental stone industry. Employing the Design Science Research (DSR) methodology [

16], the study focuses on conceptualizing and developing a framework adaptable to this sector’s unique challenges [

17].

DSR is a systematic methodology for addressing real-world challenges by creating and evaluating practical solutions [

18]. Central to DSR is the iterative process of building and refining artefacts—such as frameworks, systems, or models—that bridge the gap between theory and application (Peffers et al., 2007). By balancing relevance and rigour, DSR ensures that solutions are grounded in empirical evidence while addressing the needs of practitioners [

19].

To evaluate the framework, a mixed-methods approach was adopted, integrating interviews and structured questionnaires to ensure robust triangulation and generate empirical evidence [

20]. The evaluation focused on five key dimensions: operator performance, lead time, efficiency, customer satisfaction, and innovation. These dimensions were chosen to assess the framework’s impact comprehensively:

Operator performance: Evaluated improvements in skill levels and productivity.

Lead time: Measured reductions in training duration and process optimization.

Efficiency: Assessed operational workflows and resource utilization.

Customer satisfaction: Considered indirect outcomes linked to enhanced workforce capabilities.

Innovation: Explored the framework’s potential to foster novel solutions within the sector.

The findings provide valuable insights into the framework’s feasibility and potential adoption, emphasizing its ability to address workforce training gaps and its applicability beyond the ornamental stone industry.

2. Literature Review

Integrating humans and machines introduces a transformative dimension to workforce training, requiring a multidisciplinary approach that combines technical expertise with competencies in artificial intelligence, data analysis, and ergonomics [

7]. This synergy is particularly significant in industries such as ornamental stone processing, where operations demand high precision, technical knowledge, and continuous skill enhancement to sustain efficiency and innovation [

21]. As advanced technologies reshape industrial practices, the need for updated technical expertise and comprehensive training programs becomes increasingly critical [

22].

In the ornamental stone industry, workforce training must address the complexities of assembly, machining, and data management while preparing workers to adopt emerging technologies like digital twins. However, disparities in training quality and accessibility remain a significant challenge. Some institutions leverage cutting-edge technologies, while others face resource limitations that hinder their ability to prepare their workforce for global markets [

14]. This disparity underscores the urgent need for innovative, scalable, and universally accessible training solutions to bridge these gaps.

Digital twins have emerged as a cornerstone of Industry 4.0, offering powerful capabilities in simulation, analysis, and process optimization [

23]. A digital twin is a virtual representation of a physical system that enables safe experimentation, scenario testing, and learning through simulated operations. This technology has proven effective in managing complex processes, such as robotic milling and machining, where precision and adaptability are crucial [

24]. Digital twins also allow trainees to engage with complex systems, test solutions, and learn from mistakes without risking physical equipment, significantly reducing costs and accelerating learning while ensuring alignment with industrial practices [

25].

The research underscores the effectiveness of digital twins in fostering immersive and interactive learning experiences. For example, Erdei et al. (2022) developed a digital twin-based training centre for industrial robotic arms, replicating movements like Point-To-Point (PTP), Linear (LIN), and Circular (CIRC) [

26]. Their system allowed users to program movements, interact with the virtual robot, and receive immediate feedback, emphasizing the importance of accurately recreating industrial complexities. Similarly, Zhu et al. (2023) extended this concept to milling robots, incorporating real-time visualization and monitoring to address challenges such as cutting speeds and path strategies. Their system enabled operators to analyze processes, identify deviations, and improve precision and training effectiveness [

24].

Despite these advancements, gaps remain in applying digital twins for workforce training, particularly for SMEs. Existing research predominantly focuses on high-tech industries or generalized frameworks, neglecting SMEs’ specific challenges, such as limited resources and the complexity of specialized operations. Furthermore, current studies have yet to explore how digital twin frameworks can be tailored to create scalable, cost-effective solutions for industries transitioning from traditional to digital operations [

12].

Building on these insights, the following section outlines the methodology employed in designing, evaluating, and validating the DT4WFT framework. This includes a detailed discussion of the DSR methodology and the mixed-methods validation process that forms the foundation of this study.

3. Methodology

This study adopts the DSR methodology to develop and validate the DT4WFT. DSR provides a structured, iterative approach that focuses on creating, evaluating, and refining artefacts to address real-world challenges while ensuring scientific rigour and practical applicability [

16]. By emphasizing relevance and rigour, DSR is particularly suited to addressing the workforce training challenges SMEs face in the ornamental stone industry [

17].

The methodology centres on leveraging digital twin technology to create scalable, accessible, cost-effective training solutions tailored to industry-specific needs. The development process involves several interconnected stages, each addressing critical components of the DT4WFT framework [

27].

The first stage focuses on problem identification, addressing the lack of practical training solutions for SMEs in the ornamental stone industry. These enterprises often contend with limited resources, high training costs, and the need for operational precision. The DT4WFT framework is designed to overcome these challenges by creating immersive virtual training environments that enhance operator performance, improve operational efficiency, reduce training lead times, elevate customer satisfaction, and foster innovation.

The DT4WFT integrates advanced digital twin technologies with tailored training processes in the framework design and development phase. This framework aligns with the capabilities of the Cut-To-Size Smart Lines (CtSSL) systems, a state-of-the-art machine widely used in the Portuguese ornamental stone industry [

28]. Key design elements include developing virtual simulations that replicate critical tasks such as stone cutting and polishing, embedding advanced mechatronic principles to ensure precise modelling of machinery dynamics, implementing robust security measures to guarantee system confidentiality and reliability, and emphasizing the framework’s novelty, modularity, and adaptability for diverse industrial contexts.

The implementation phase involves integrating the DT4WFT into real-world operations in the ornamental stone industry. Using a CtSSL technological system, the framework facilitates virtual training simulations aligned with existing workflows. This includes integrating operational controls, enhancing simulation fidelity through mechatronic concepts, synchronizing virtual and physical systems using signal adapters, and optimizing operator understanding and system performance through motion simulations and diagnostics.

Validation of the DT4WFT framework employs a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative insights from interviews with SME managers and quantitative data from structured questionnaires [

29]. The interviews capture perspectives on the framework’s relevance and effectiveness. At the same time, the questionnaires evaluate the respondent’s opinions across dimensions such as operator efficiency, lead time reductions, and readiness for digital transformation. This comprehensive validation process ensures that the framework meets the unique requirements of SMEs while demonstrating its adaptability and scalability for broader industrial applications.

The following section explores the conceptualization and design of the DT4WFT framework in detail, providing a comprehensive overview of its structure, components, and innovative approach to addressing workforce training challenges in SMEs.

4. Designing and Developing of a Digital Twin Framework for Workforce Training (DT4WFT)

A digital twin’s effectiveness lies in its virtual model’s accuracy [

30]. Any misalignment between the digital twin and its physical counterpart can lead to suboptimal decisions or operational inefficiencies [

2]. Achieving high fidelity requires meticulous mapping of every component, movement, and interaction within the physical system, ensuring a precise and dynamic representation in the virtual environment [

10].

Among SMEs’ advanced technologies in the ornamental stone industry, Cut-To-Size Smart Lines (CtSSL) exemplify state-of-the-art innovation. These systems are engineered to produce customized stone components for high-precision construction applications, setting a benchmark for operational excellence and technological sophistication in the sector [

15].

Integrating digital twin technology with CtSSL systems creates a Cyber-Physical System (CPS) that bridges the physical and virtual realms. This integration allows operators to monitor, simulate, and optimize machine performance in real-time, either locally or remotely [

3]. Such a feedback-driven system promotes continuous precision, efficiency, and adaptability improvement, representing a transformative leap for the ornamental stone industry [

31].

CtSSL systems are characterized by a gantry line with three linear axes (X, Y, Z) and two rotational axes (B, C), making them ideal for high-precision cutting and shaping of ornamental stones. Key components include:

Cutting Tool: Equipped with a rotating cutting disc capable of tilting up to 45 degrees on the B-axis, enabling angled and precision cuts for intricate designs.

Cutting Head Module: Provides 360-degree rotation on the C-axis, facilitating multi-directional cuts and improving processing efficiency.

Z-Axis Module: Ensures vertical motion for precise depth cuts tailored to specific design requirements.

X-Axis Module: This module supports horizontal motion for longitudinal and transverse cuts, complemented by Y-axis movement to ensure full surface coverage.

Feed System: Automated systems stabilize and move stone slabs during cutting, reducing errors and ensuring high precision.

These components work harmoniously to transform raw stone slabs into precisely shaped parts. Integrating CtSSLs with their digital twins enables advanced simulation, real-time monitoring, and predictive optimization. This seamless coordination underscores the transformative potential of digital twin technology, mainly when applied to traditional industries like ornamental stone manufacturing.

In this context, advanced workforce training must integrate methodologies, technologies, and operational practices to ensure both effectiveness and safety. SMEs like ornamental stone manufacturing demand training programs that go beyond knowledge transfer to focus on adapting to advanced technologies and optimizing existing processes [

32]. Effective training programs are critical, especially given the stakes in maintaining precision and efficiency [

26].

A robust training program relies on key building blocks, including technical content, training tools, and procedural workflows.

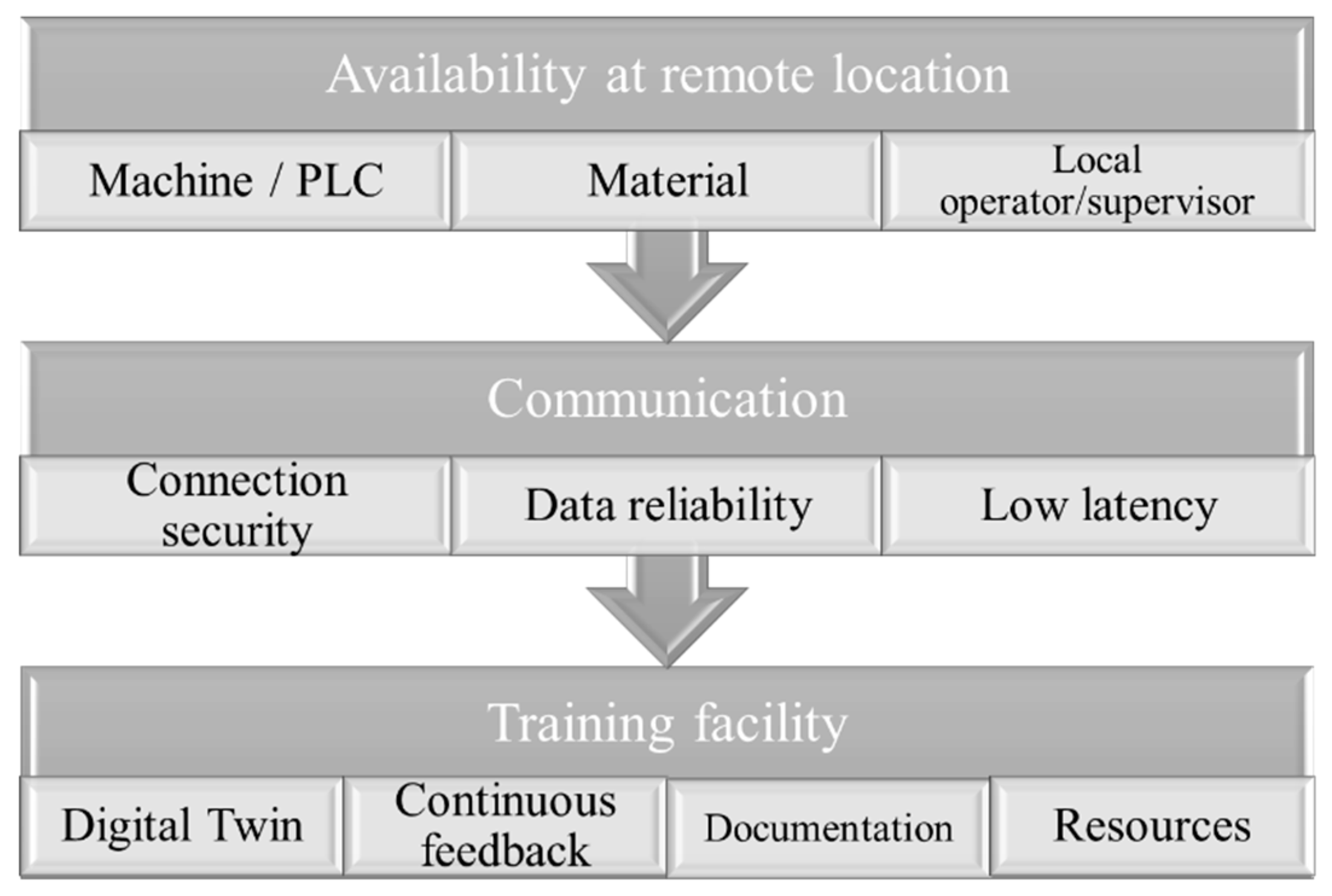

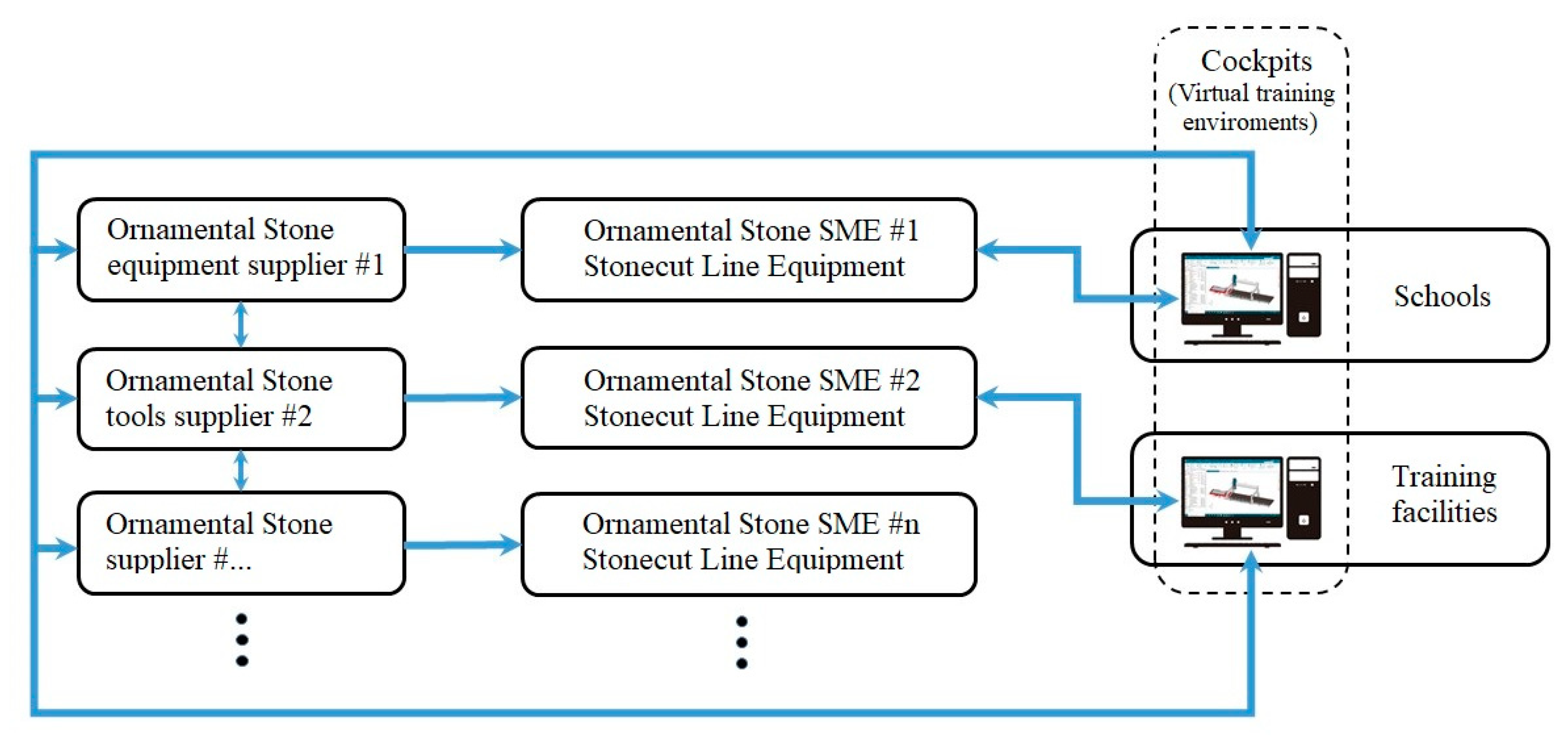

Figure 1 outlines the fundamental assumptions necessary for constructing a successful training session.

The virtual training cockpit is central to this ecosystem, incorporating the digital twin of CtSSL equipment into a controlled virtual environment [

28]. This allows trainees to engage with simulated scenarios and gain hands-on experience without the risks associated with live operations. Key stakeholders play vital roles: (1) Industrial Training Centers or Schools, providing physical facilities connected to real-world equipment used in ornamental stone companies; and (3) Equipment Suppliers, offering updated 3D models and physics-based simulations that form the foundation of the digital twin, along with physical equipment that mirrors the digital twin, ensuring consistency between virtual and physical environments.

Figure 2 illustrates how resources and information flow from equipment suppliers to the training cockpit, enabling seamless transitions between virtual and physical environments and maximizing training effectiveness.

Stakeholder collaboration ensures that digital twins remain aligned with real-world changes. Equipment suppliers continuously update 3D models and simulations based on technological advancements, while training centres integrate these updates into their curricula. This alignment enhances training quality and ensures that workforce skills match industrial demands. Research highlights the importance of stakeholder collaboration in digital twin environments. Schneider et al. (2021) emphasize the value of realistic training scenarios enabled by 3D simulations [

13], while Stavropoulos and Papacharalampopoulos (2022) underscore the role of equipment suppliers in bridging virtual and physical environments [

12]. Alexopoulos et al. (2020) also demonstrate how integrating machine learning insights into digital twin environments creates adaptive and efficient training ecosystems [

11].

By integrating digital twin technology into workforce training, SMEs in the ornamental stone industry can overcome traditional barriers, including geographic constraints, high training costs, and limited access to advanced equipment. This innovative approach enhances workforce skill sets, modernizes training practices, and positions SMEs for success in a technologically advanced industrial landscape.

The Siemens NX Mechatronic Concept Design (MCD) software exemplifies cutting-edge technology that integrates mechanics, electronics, and computer science to develop efficient and adaptable systems [

33]. This integration is critical for optimizing processes and enhancing the operational efficiency of advanced machinery like CtSSLs [

34]. Digital twins, inherently embodying cyber-physical systems, enable dynamic interaction, simulation, and optimization of industrial processes [

33]. Siemens NX MCD provides several features for virtual modelling, including:

Rigid Body Definition: Models mobile components with high accuracy in the virtual environment.

Collision Body Definition: Ensures spatial constraints are respected, mitigating proximity risks.

Virtual Commissioning: This technology supports testing and debugging control code on virtual prototypes, minimizing the risks and costs associated with physical commissioning.

Real-Time Data Integration: Dynamically adjusts virtual models to reflect changing operating conditions, particularly valuable for machinery like CtSSLs with complex moving components.

The complexity of CtSSL systems makes them ideal candidates for Siemens NX MCD, which supports testing configurations, debugging control logic, and visualizing motion dynamics for precise operations.

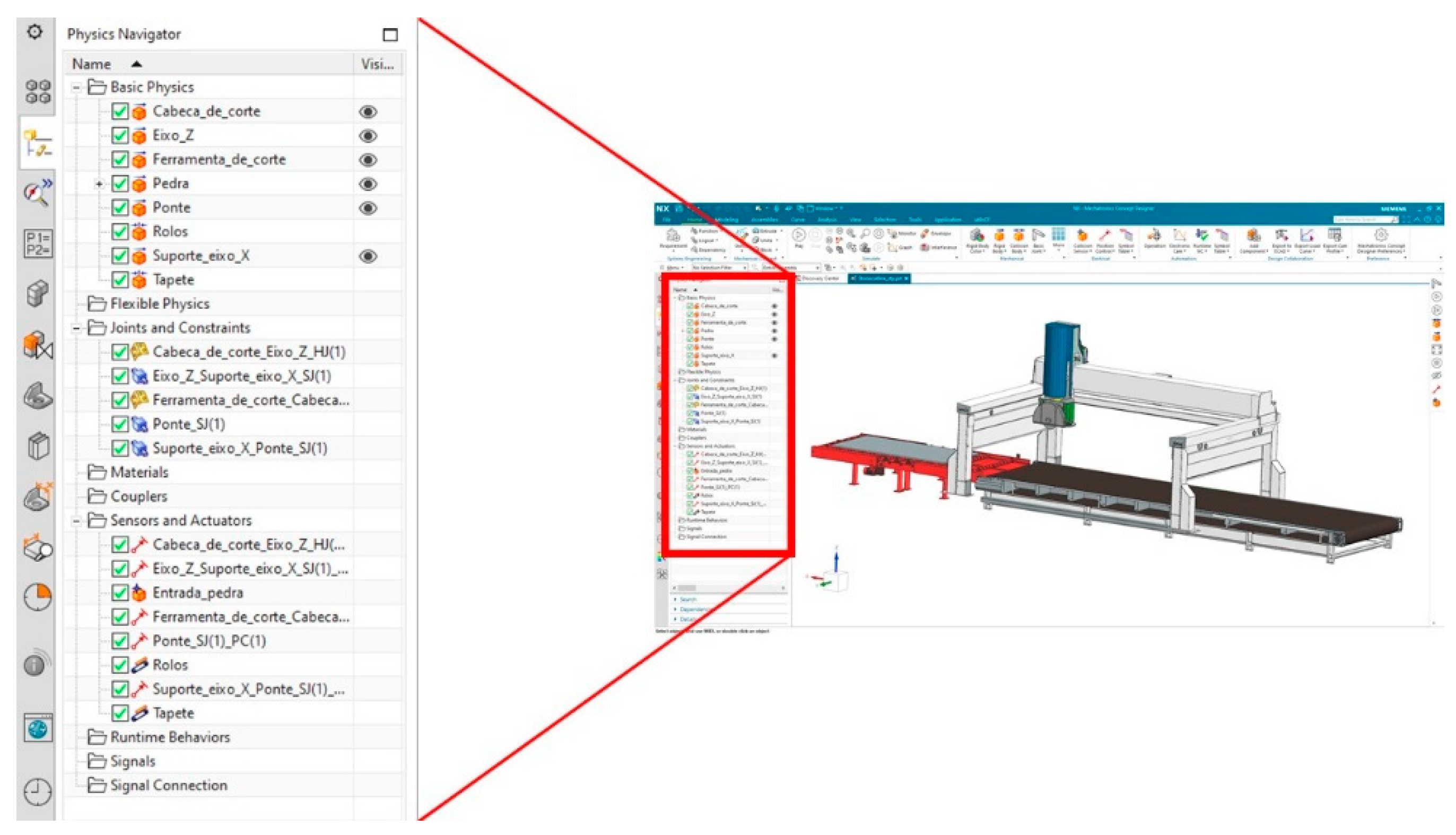

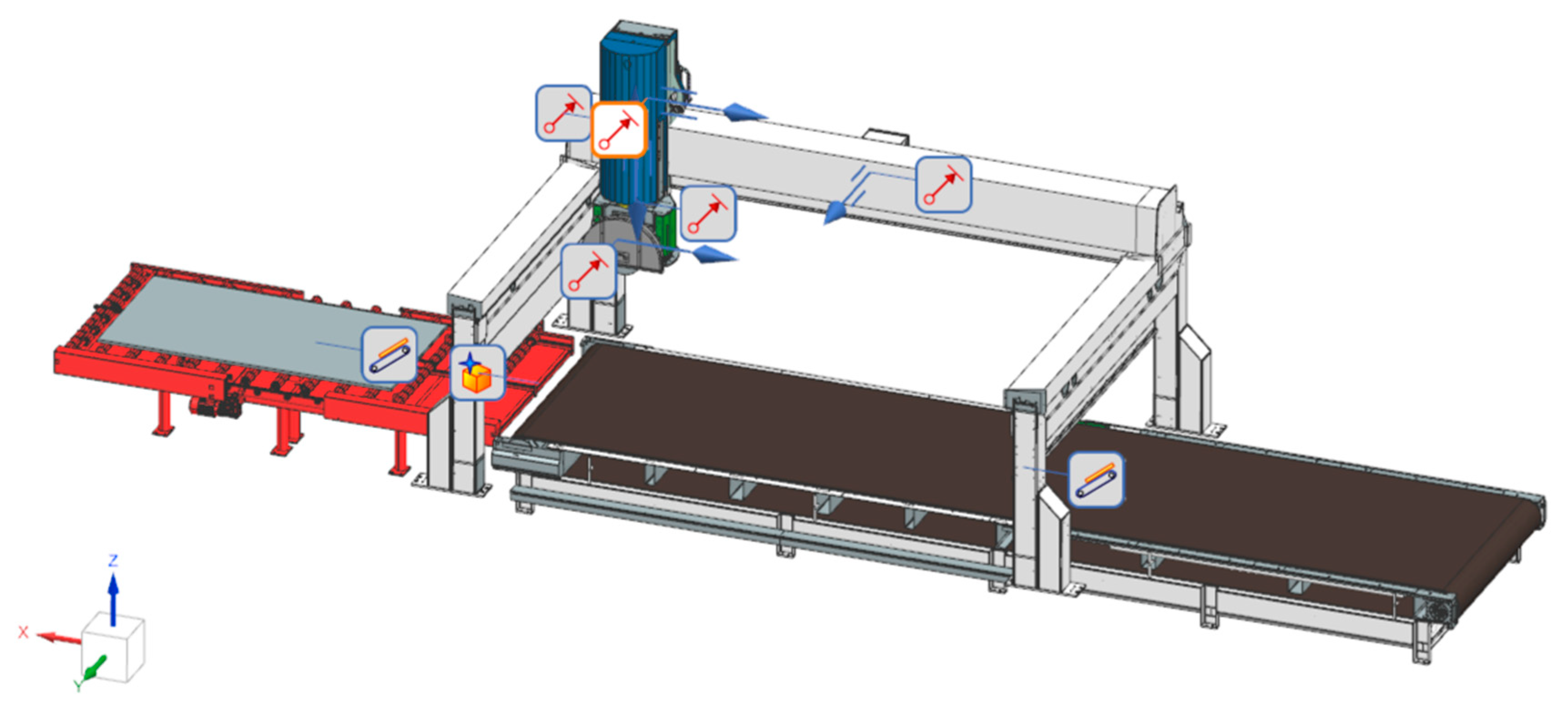

Figure 3 illustrates the physics of CtSSL systems as defined in Siemens NX MCD.

By leveraging these advanced mechatronic design concepts, Siemens NX MCD enhances the precision, efficiency, and reliability of CtSSL digital twins. This integration optimizes current machinery and lays the foundation for future technological advancements in the ornamental stone industry.

4.1. Ensuring Confidentiality and Reliability

The success of digital twin-based training depends on three interconnected pillars: technological infrastructure, pedagogical design, and security and reliability [

26]. Technological infrastructure ensures that robust digital twin systems can accurately simulate real-world scenarios, providing real-time feedback and seamless integration with manufacturing processes [

13]. Pedagogical design tailors training modules to meet trainees’ cognitive and skill-level needs, ensuring clarity, engagement, and skill transferability. Security and reliability provide the foundation for uninterrupted and trusted access to training systems, addressing critical concerns in operational and data integrity [

14].

Digital twin technologies are versatile tools for creating dynamic and interactive training environments. For instance, Schneider et al. (2021) demonstrated their effectiveness in simulating wafer transportation systems, where immersive interactions significantly enhanced trainee understanding [

13]. Similarly, Stavropoulos and Papacharalampopoulos (2022) emphasized the role of precise simulations in micromanufacturing training, enabling trainees to experiment with complex systems without risking physical errors or damages [

12]. These applications highlight the value of virtual environments, where trainees can gain hands-on experience, test hazardous scenarios, and benefit from interactive learning.

Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) complement digital twins by bridging theoretical knowledge and practical applications. Kaarlela et al. (2020) explored VR’s role in safety training, demonstrating how immersive simulations enhance situational awareness and decision-making [

14]. These technologies integrate seamlessly with digital twins, providing opportunities for interactive troubleshooting, safety protocol simulations, and enhanced visualization of intricate systems. Erdei et al. (2022) further highlight the potential of such integrations to foster meaningful learning experiences [

26].

Integrating supervised machine learning with digital twins enables the creation of adaptive training systems. As Alexopoulos et al. (2020) discuss, these systems dynamically adjust training content based on trainee progress, offering personalized learning paths [

11]. This approach ensures real-time performance assessment, identifies skill gaps, and provides tailored interventions, ultimately improving training efficiency and outcomes.

Remote access to digital twin systems introduces challenges related to confidentiality and reliability. Confidentiality safeguards sensitive information, while reliability ensures seamless and accurate system operation. Measures to protect confidentiality include encryption protocols, which secure data during transmission, and authentication mechanisms, which restrict access to authorized users [

35]. Reliability is achieved through strategies such as maintaining uninterrupted data transmission, ensuring smooth operation of simulation models, and preventing errors in motion control systems [

36].

Balancing confidentiality and reliability is critical. While encryption enhances security, it can slow communication speeds. For example, VPNs provide secure connections but may introduce delays due to encryption processes, while IIoT devices offer faster communication but require robust cybersecurity measures to prevent vulnerabilities [

37]. These trade-offs underscore the need for tailored security solutions that align with operational requirements.

Confidentiality and reliability are paramount in digital twin systems like the CtSSLs due to real-time data exchanges for performance monitoring, predictive maintenance, and virtual simulations. Breaches in data security could compromise both the training process and the system’s operational integrity [

26]. Similarly, unreliable connections could disrupt motion simulations, leading to errors and operational inefficiencies in virtual and physical systems [

10].

Effective training programs built on digital twins must address these concerns holistically. Encryption safeguards sensitive data, while authentication mechanisms and robust firewalls ensure secure access. Simultaneously, strategies to enhance reliability—such as redundant connections and real-time data optimization—maintain seamless operations. The integration of VR, AI, and adaptive learning further ensures a comprehensive approach that meets the training needs of SMEs in the ornamental stone industry.

Integrating confidentiality and reliability principles into digital twin systems, like the CtSSLs, showcases the transformative potential of these technologies in aligning workforce training with industry requirements. These considerations set the stage for describing the DT4WFT, which builds on these foundations to offer SMEs a scalable and adaptable solution

The DT4WFT’s backbone is provided by the foundations of confidentiality, reliability, and interactive learning. The following subsection delves into this framework’s design principles and structural components, demonstrating how it addresses industry-specific challenges and transforms workforce training practices.

4.2. Describing the Digital Twin Framework for Workforce Training Framework (DT4WFT)

The DT4WFT addresses a critical research gap in applying digital twin technologies to workforce training in SMEs, particularly in traditional sectors like the ornamental stone industry. While digital twins have gained widespread adoption for optimizing industrial processes, their potential to revolutionize workforce training has remained underexplored. DT4WFT bridges this gap by offering an adaptable, systematic approach tailored to this domain’s unique challenges of workforce development.

Custom Digital Twin Integration forms the core of the framework. DT4WFT leverages tailored digital twin models, such as those designed for CtSSLs, to align closely with the operational and training requirements of the ornamental stone sector. These high-fidelity virtual replicas simulate real-world machinery with precision, enabling trainees to engage with accurate representations of actual operations. By incorporating physics-based simulations and real-time data integration, the framework ensures that virtual environments reflect the dynamics of physical systems, enhancing the relevance and effectiveness of the training.

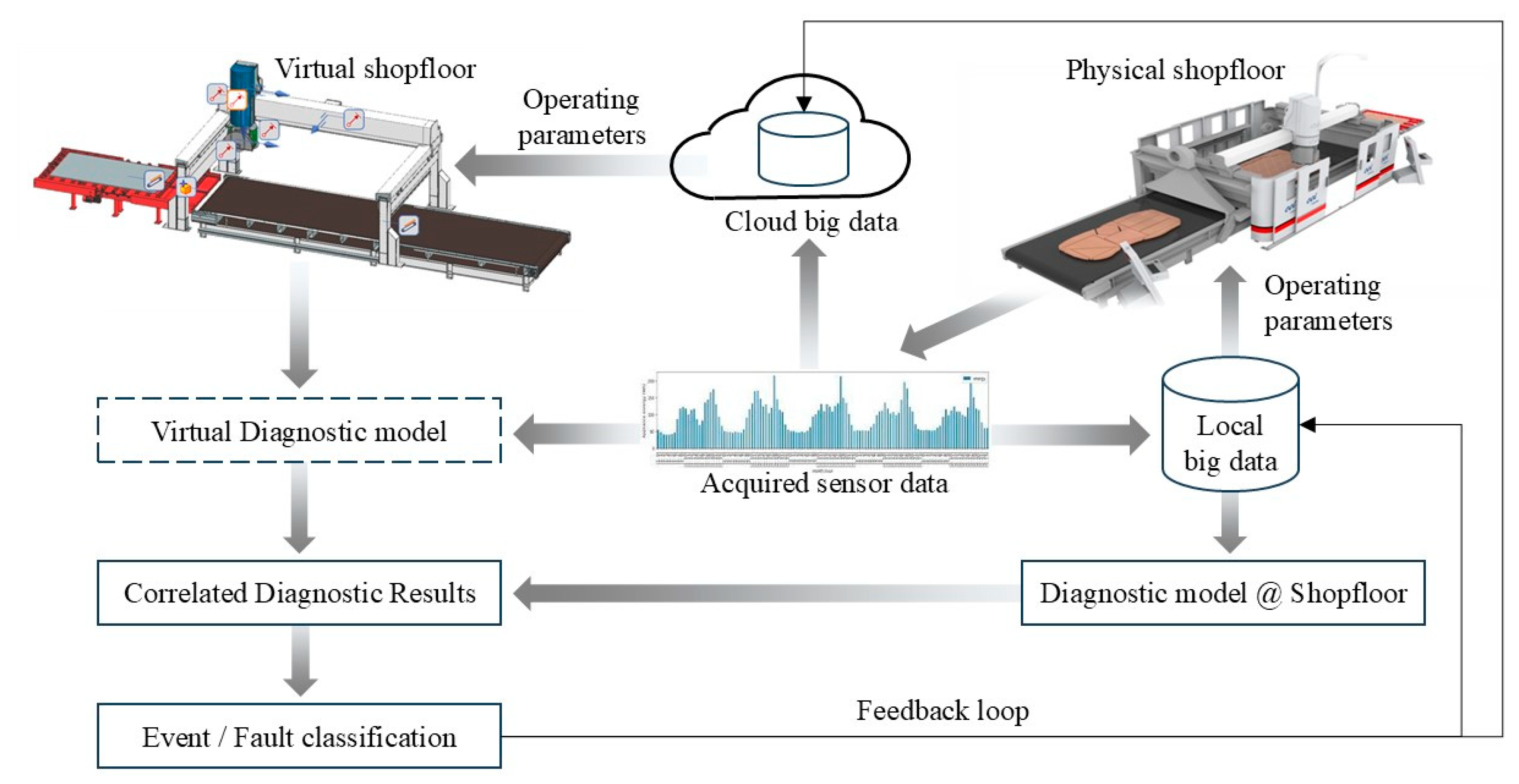

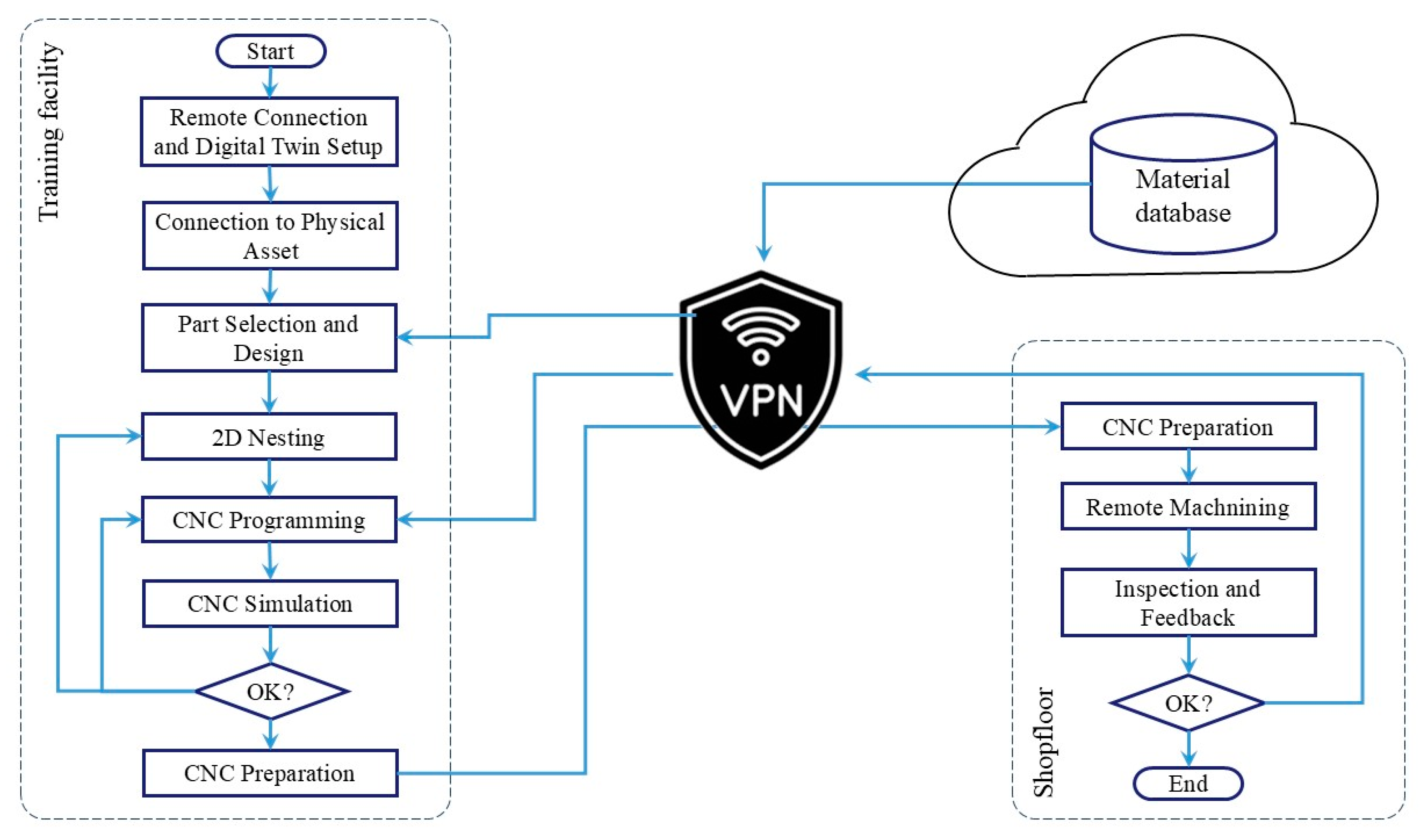

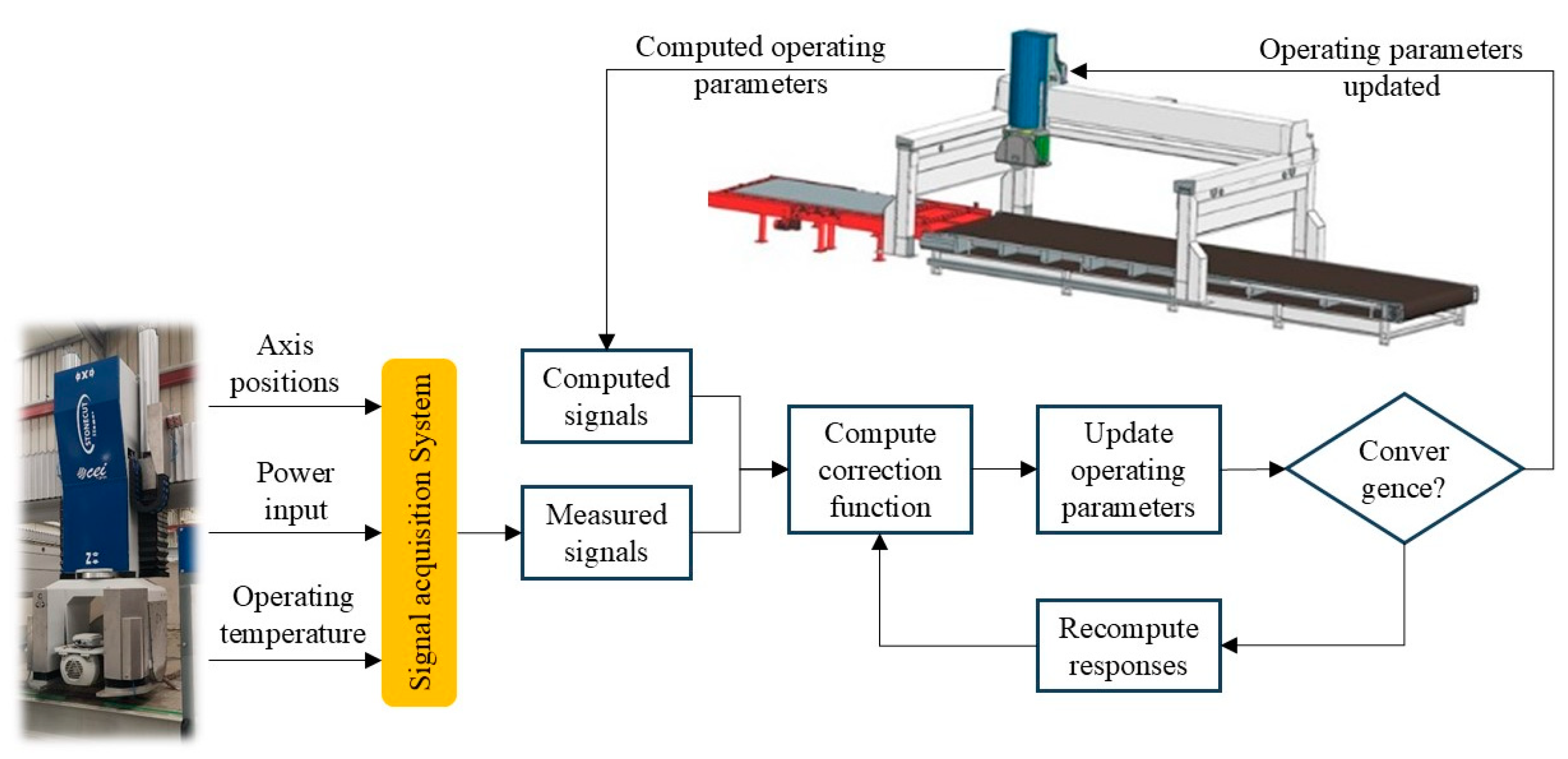

The DT4WFT framework establishes an Advanced Training Ecosystem that integrates virtual training cockpits [

28], real-world equipment, and iterative feedback loops. This ecosystem allows trainees to engage in immersive, context-specific learning experiences replicating complex scenarios, such as machine calibration, fault detection, and precision cutting. As depicted in

Figure 4, the workflow for implementing a training digital twin involves creating digital twin models tailored to specific training objectives, conducting sessions in virtual environments, and applying the insights gained to physical systems at industrial facilities. The iterative nature of this workflow ensures continuous alignment with evolving industry needs and technological advancements.

DT4WFT directly addresses the workforce training challenges of traditional methods in the ornamental stone industry. On-site, hands-on training often faces geographic and logistical constraints, further exacerbated by global disruptions like pandemics or regional conflicts, which limit access to physical facilities and equipment. The framework overcomes these barriers by enabling remote training through advanced simulation environments, allowing trainees to acquire critical machining skills flexibly while maintaining technical depth and specificity.

Distinctive Contributions set DT4WFT apart from general-purpose platforms. It is not a product but a replicable methodology that systemizes integrating digital twins into training environments. Its scalability, adaptability, and scientific rigour emphasize its utility across various industrial contexts. By fostering collaboration among stakeholders—including training centres, SMEs, and equipment suppliers—the framework facilitates the continuous refinement of training content, keeping it aligned with technological advancements and industry demands.

While designed for the ornamental stone sector, DT4WFT’s modular and flexible design extends its applicability beyond this industry. In manufacturing, it can train operators on robotic systems and assembly lines; in healthcare, it can simulate surgical procedures and patient workflows; and in construction, it supports training for heavy machinery operation and technical installations. This adaptability makes the framework a versatile solution for diverse industrial applications.

DT4WFT also bridges the gap between practical implementation and scientific inquiry by integrating real-time data feedback, predictive analytics, and rigorous evaluation metrics. Its structured approach ensures scalability to emerging industries and technologies, providing a robust foundation for future research and development in digital twin applications.

Finally, DT4WFT represents a significant advancement in workforce training methodologies by integrating tailored digital twin applications, fostering stakeholder collaboration, and ensuring adaptability for evolving industry needs. Its ability to address gaps in training accessibility, relevance, and effectiveness underscores its potential as both a scientific contribution and a practical model for workforce development in traditional and emerging sectors.

Having outlined the conceptual foundations and structural components of the DT4WFT framework, the following section delves into its development. It details how the framework is operationalized, highlighting the processes, technologies, and collaborative efforts that bring it to life and ensure its alignment with industrial demands.

5. Implementation of a Digital Twin Framework for Workforce Training (DT4WFT)

The Portuguese ornamental stone industry is crucial to the nation’s economy, contributing significantly to local employment and international trade [

38]. Comprised predominantly of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), the sector supports over 16,600 jobs, providing critical economic stability to inland regions. Despite challenges such as intense global competition and the pressure to adopt advanced technologies, the industry has demonstrated resilience, achieving sustained export growth. This success has solidified Portugal’s position as a leading global player in the ornamental stone market [

15].

SMEs are the backbone of this industry, driving production, processing, and exports while adopting innovative technologies to meet evolving market demands. Among these advancements, CtSSLs have emerged as transformative systems, enhancing operational efficiency and enabling precision manufacturing. The StoneCUT@Line®, one of the most advanced CtSSL systems globally, exemplifies this innovation. Designed to meet the specific needs of the ornamental stone industry, the system integrates state-of-the-art technologies that offer (1) Precision Cutting, achieving high accuracy in shaping natural stones; (2) High-Quality Finishes, delivering superior aesthetic and functional outcomes for architectural applications; and (3) Customization Capabilities, enabling tailor-made products to meet diverse project requirements.

Central to the StoneCUT@Line® is its detailed 3D model, which comprehensively represents its construction and operation. This model allows users and technicians to understand the system’s functionality in-depth, analyze the engineering principles underlying its operation, and interact with components for advanced training and maintenance through visualization and simulation [

10].

The integration of the DT4WFT within the Portuguese ornamental stone industry addresses both the technological and workforce challenges SMEs face. By combining virtual environments with advanced machinery like the StoneCUT@Line®

1, the framework provides innovative solutions to optimize operations, enhance workforce capabilities, and sustain competitive advantages in a rapidly evolving global market. This approach demonstrates the potential of leveraging cutting-edge technology with tailored training methodologies to meet industry-specific demands. Equipping SMEs with modern tools and techniques positions them for long-term success in a dynamic industrial landscape.

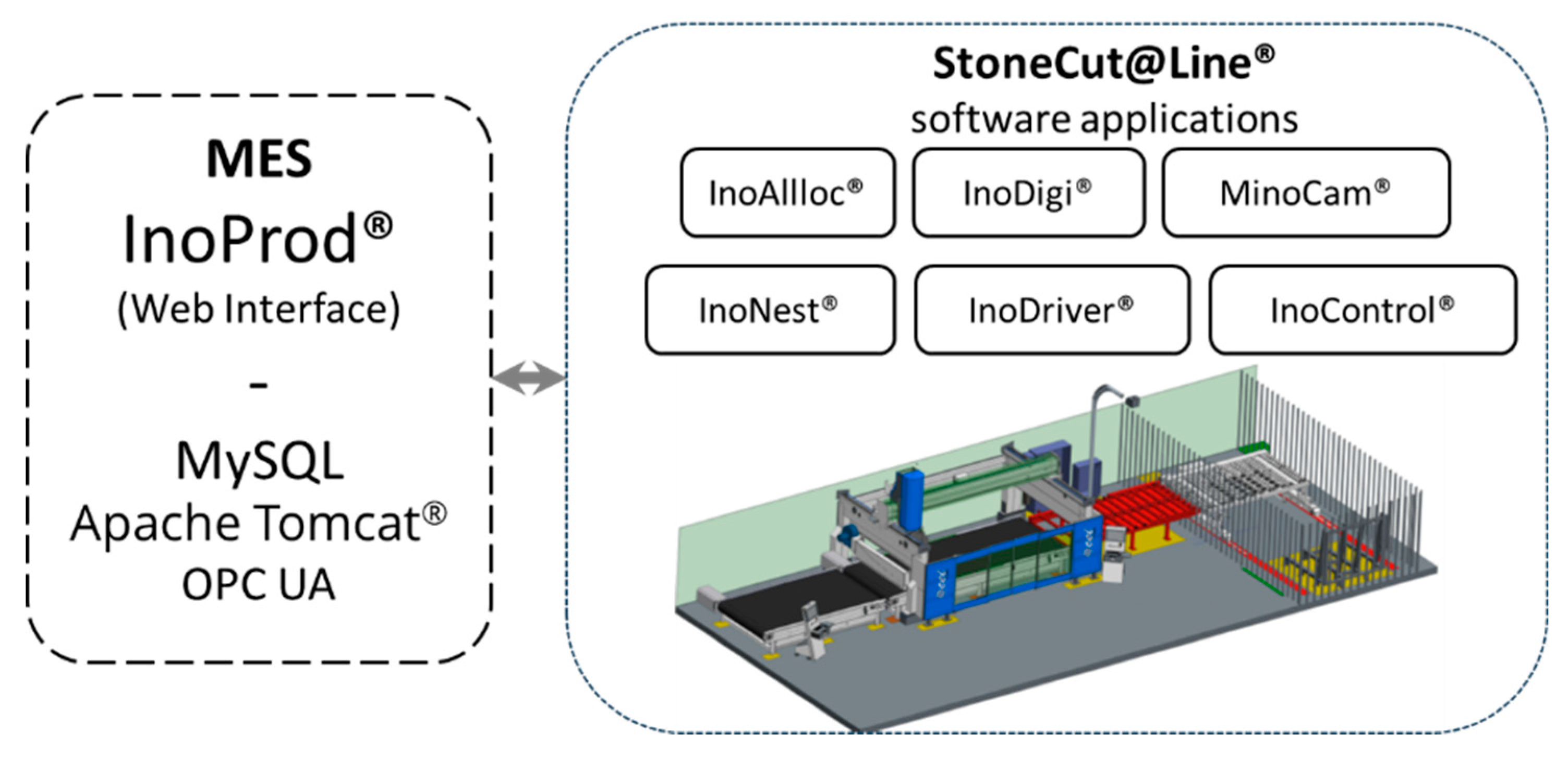

The StoneCUT@Line® features specialized application modules that interface the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system and customer operations. These modules enable real-time data collection via the OPC Unified Architecture (OPC-UA) [

39] protocol, seamlessly gathering information from sensors and actuators. The system’s software ecosystem, detailed in

Table 1, underscores its role in enabling efficient shop floor operations.

The InoProd® platform

2, a robust Manufacturing Execution System (MES), seamlessly integrates with the StoneCUT@Line® through functional apps. This platform collects and manages real-time data, facilitating single-machine and multi-machine setups. Its network architecture, depicted in

Figure 5, ensures efficient communication and coordination across shop floor operations.

The OPC-UA protocol, a secure and platform-independent communication framework, facilitates remote communication in the StoneCUT@Line®. This protocol eliminates bottlenecks and reduces data translation errors, ensuring enhanced interoperability, real-time data collection, and scalability. It also supports digital twin integration by enabling seamless communication between the StoneCUT@Line® and platforms like Siemens NX Mechatronic Concept Design, fostering precise simulation and informed operational decision-making [

40].

By combining the capabilities of the InoProd® platform, its functional apps, and OPC-UA protocols, the StoneCUT@Line® exemplifies the seamless integration of advanced data collection and communication tools [

41]. This architecture enables real-time monitoring, predictive analytics, and virtual simulations, supporting performance optimization and driving innovation. These capabilities position SMEs in the ornamental stone industry to thrive in a competitive global market.

The next step in this development process involves integrating advanced mechatronic concepts, as detailed in the following subsection. This integration ensures that the StoneCUT@Line® digital twin achieves the precision and adaptability required for effective workforce training and operational excellence.

Building on this robust technological foundation, the following subsection explores the incorporation of mechatronic principles into the StoneCUT@Line® digital twin. This step enhances the system’s modelling capabilities, ensuring that it delivers realistic and actionable training and operational outcomes.

5.1. Mechatronic Concept in StoneCUT@Line® Digital Twin Integration

The Siemens NX Mechatronic Concept Design (MCD) software is a state-of-the-art tool that integrates mechanics, electronics, and computer science to develop efficient and adaptable manufacturing systems. This interdisciplinary approach is critical in modern industrial environments, particularly for complex machinery like the StoneCUT@Line®, where precision, adaptability, and operational efficiency are essential [

34]. Siemens NX MCD enhances manufacturing processes by enabling seamless integration across domains and bridging the gap between virtual design and physical implementation.

Central to Siemens NX MCD’s application is its ability to create and manage digital twins—virtual representations of physical systems that enable simulation, analysis, and optimization in controlled environments [

33]. These digital twins replicate the physical system’s behaviours, empowering engineers to refine designs, troubleshoot issues, and optimize performance before deployment, reducing risks and associated costs.

The software offers several advanced features essential for digital twin development. Rigid Bodies simulate the physical behaviour of mobile components, ensuring realistic modelling. Collision Bodies define spatial constraints and interactions between components, safeguarding operational integrity and safety. Virtual Commissioning enables engineers to test and debug control systems on virtual prototypes, ensuring optimized functionality before physical implementation. Real-Time Data Integration incorporates live inputs into virtual models, allowing for dynamic adjustments and responsiveness to changing conditions.

The application of Siemens NX MCD to the StoneCUT@Line® system highlights its transformative potential. With multiple moving components and intricate operational requirements, the StoneCUT@Line® benefits from the software’s ability to simulate motion dynamics and refine system interactions. Engineers can identify and resolve design flaws early, reducing disruptions and development costs. Configurations can be optimized to enhance system performance, while control systems can be debugged in a risk-free virtual environment to ensure reliability and precision.

A key feature of Siemens NX MCD is its ability to visualize the StoneCUT@Line®’s mechanics through detailed modelling of rigid bodies, collision boundaries, and motion dynamics.

Figure 6 illustrates the solid model of the StoneCUT@Line® as defined within Siemens NX MCD, showcasing the system’s physical interactions and configurations.

By integrating mechatronic design principles with digital twin technology, Siemens NX MCD bridges virtual simulations and real-world applications, ensuring complex machinery operates with precision, adaptability, and efficiency. This approach simplifies the design and commissioning process and sets a benchmark for innovation in the ornamental stone industry. The enhanced understanding of system mechanics by Siemens NX MCD also supports advanced workforce training, equipping operators with the tools to engage effectively with cutting-edge machinery.

Building on this robust foundation, the next section delves into the electrical configurations facilitated by signal adapters. These adapters synchronize virtual models with physical systems to enable seamless operation and real-time communication.

5.2. Electrical Configurations Using Signal Adapter

Accurate electrical configurations are essential for ensuring complex machinery’s precise and efficient operation in both manufacturing and simulation contexts. Within MCD, the Signal Adapter acts as a critical intermediary, translating signals between physical equipment and its digital twin. This integration is vital for systems like the StoneCUT@Line®, which generates multiple operational signals—such as position, velocity, and force parameters—for its actuators and sensors [

10].

Signal Mapping and Velocity Calculation are crucial in ensuring the system operates seamlessly. In Siemens NX MCD, signal mapping assigns specific parameters, such as position and velocity, to corresponding components in the 3D model. For example, velocity signals along the X, Y, and Z axes (V

x, V

y, V

z) are processed by the Signal Adapter to calculate the resultant velocity (V

f) of the cutting tool, as shown in Equation 1:

This calculation is critical for defining the tool’s entry and exit strategies, particularly for non-orthogonal cuts involving rotational movement around the Z-axis.

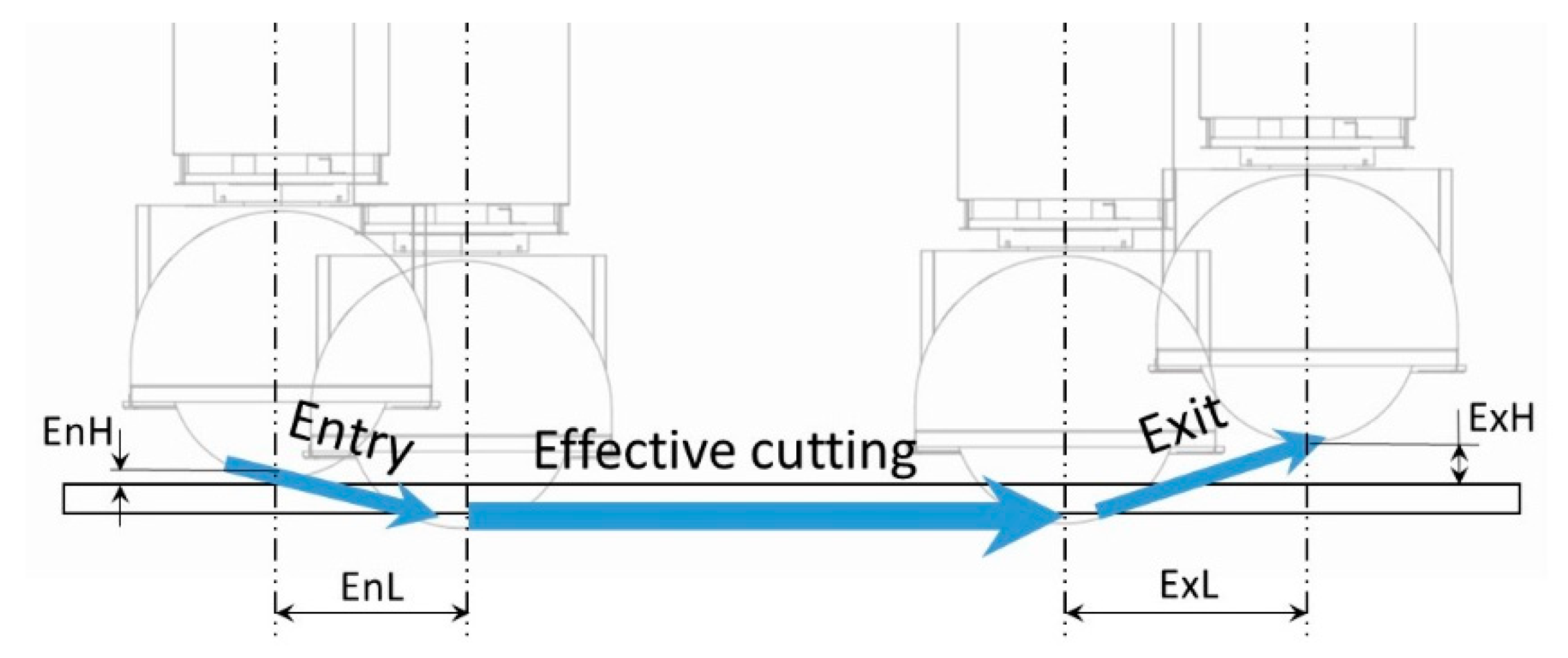

Entry and Exit Ramps for Cutting Tools are essential for protecting the cutting tool’s integrity and minimizing energy consumption during operation. When an external entry is not feasible, a gradual entry ramp allows the tool to descend smoothly to the desired cutting depth.

Figure 7 illustrates the tool’s entry, cutting, and exit movements.

These movements’ parameters depend on material hardness, stone slab thickness, and the tool’s maximum cutting depth. After completing a cut, the tool follows an exit ramp that gradually V

f and retracts to the Retract Height (ReH) for subsequent fast motions or rotations.

Table 2 details the pre-configured motion parameters for the entry, exit, and retract phases.

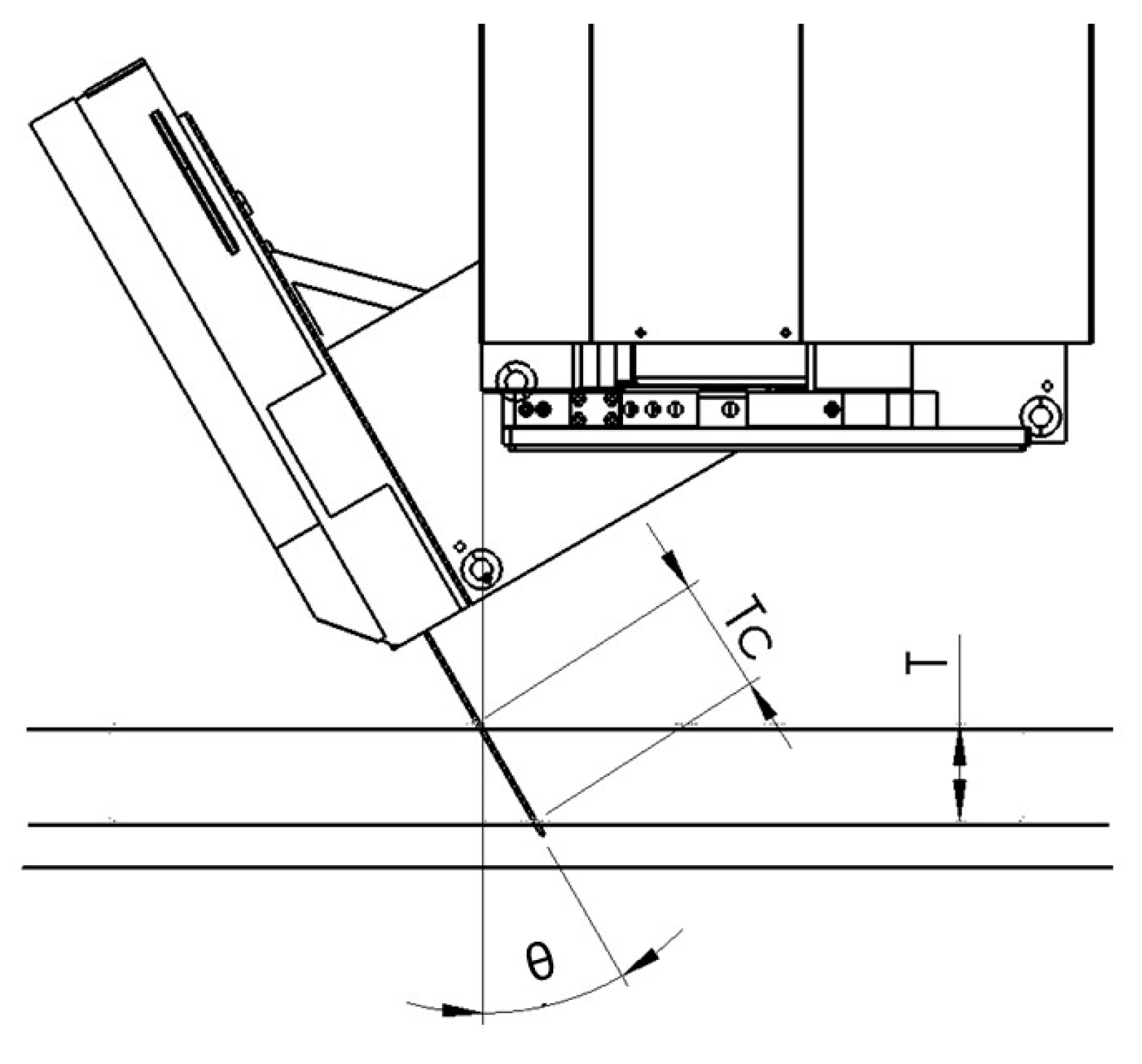

For angled cuts, where the tool rotates around the C-axis, the cutting depth (CD) increases due to the tilt angle (θ). The slab thickness (Tc) corrections are necessary to maintain precision and minimize tool wear.

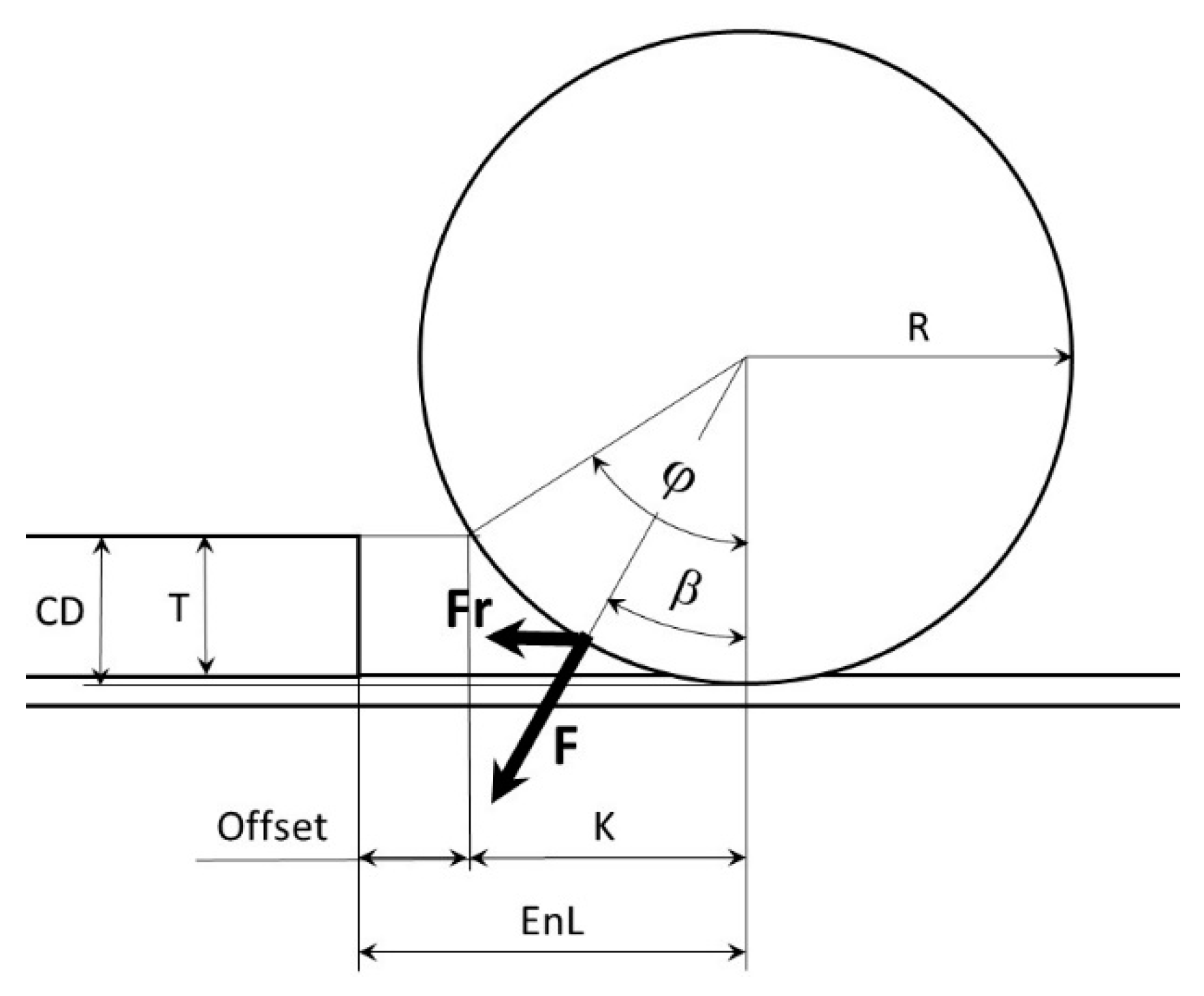

Figure 8 illustrates the adjustments required for cutting depth during angled cuts.

The cutting force (F) is calculated using Equation 2, based on material-specific cutting pressure (σ

c), cutting depth (CD), and tool width:

During the entry phase, the cutting force increases linearly as the cutting depth rises, while it decreases during the exit phase to reduce tool stress.

Figure 11 demonstrates an outside entry strategy, emphasizing precise parameter configurations to avoid unintended tool-material contact.

Figure 9.

Definition of Entry Length (EnL) for an Outside Entry.

Figure 9.

Definition of Entry Length (EnL) for an Outside Entry.

The Signal Adapter’s integration within Siemens NX MCD provides significant benefits, including real-time feedback, which enables dynamic updates to the virtual model; enhanced accuracy, ensuring that motion simulations closely replicate real-world behaviours; and increased efficiency, which facilitates quick identification and resolution of discrepancies, reducing downtime and boosting productivity. Additionally, the rolling force (F

r) can be analyzed using Equations 3 and 4, which depend on cutting force (F) and geometric parameters:

These calculations ensure precise cutting depth and trajectory alignment configurations, optimizing cutting performance and avoiding overlaps.

Figure 10 demonstrates that Entry Length EnL should depend on the cutting depth CD and cutting disc diameter. Therefore, the K value must be calculated and added the offset distance to ensure the perfect cutting of stone parts and avoid overlapping with other cutting trajectories. The K value is given by Equation 5:

These calculations ensure precise cutting depth and trajectory alignment configurations, avoiding overlaps and optimizing cutting performance.

Figure 10 displays the Physics Navigator tab in Siemens NX MCD, showcasing pre-configured electrical signals for sensors and actuators.

Figure 10.

StoneCUT@Line® Physics Defined on Siemens NX MCD.

Figure 10.

StoneCUT@Line® Physics Defined on Siemens NX MCD.

The Signal Adapter ensures accurate, efficient, and adaptive processes by bridging the gap between physical systems and their digital twins. This seamless translation of electrical configurations drives innovation and precision in modern manufacturing, solidifying the StoneCUT@Line® as a benchmark for advanced industrial systems.

Building on these precise configurations, the following section delves into diagnosing motion simulations and control in the StoneCUT@Line®, exploring how these elements optimize training and operational performance.

5.3. Diagnosing Motion Simulation and Control in StoneCUT@Line®

Motion simulation within the StoneCUT@Line® is a pivotal tool for anticipating potential faults, inefficiencies, and areas requiring optimization. Engineers and technicians gain critical insights into the system’s performance by simulating axis movements under diverse scenarios and operating conditions. These iterative simulations validate the digital twin’s fidelity, ensuring it accurately mirrors the physical asset and reliably predicts motion behaviours and system dynamics [

10].

Motion simulation serves two essential purposes. First, it acts as a diagnostic tool, identifying potential faults and inefficiencies before they escalate into operational issues. Second, it provides an educational platform for training operators and technicians by offering an interactive virtual model elucidating system processes and operations. This dual functionality prepares trainees for real-world challenges specific to the ornamental stone industry while ensuring the digital twin remains a reliable predictive tool.

The diagnostic environment within the CPS facilitates fault identification, operator training, and the digital twin’s integration into simulation, validation, and educational contexts.

Figure 11 illustrates the iterative simulation process, emphasizing its diagnostic and training potential.

Figure 11.

Iterative Simulations for Diagnosing the StoneCUT@Line®.

Figure 11.

Iterative Simulations for Diagnosing the StoneCUT@Line®.

Validation through motion simulation provides critical insights into the system’s capabilities, particularly discrepancies between computed signals generated by the digital twin and actual data from the physical asset. Such discrepancies highlight opportunities for refining motion control algorithms, power management, and safety protocols. When computed and measured signals align closely, the digital twin demonstrates its accuracy and reliability, enhancing its diagnostic and predictive effectiveness.

Figure 12 depicts the comprehensive digital twin model of the StoneCUT@Line®.

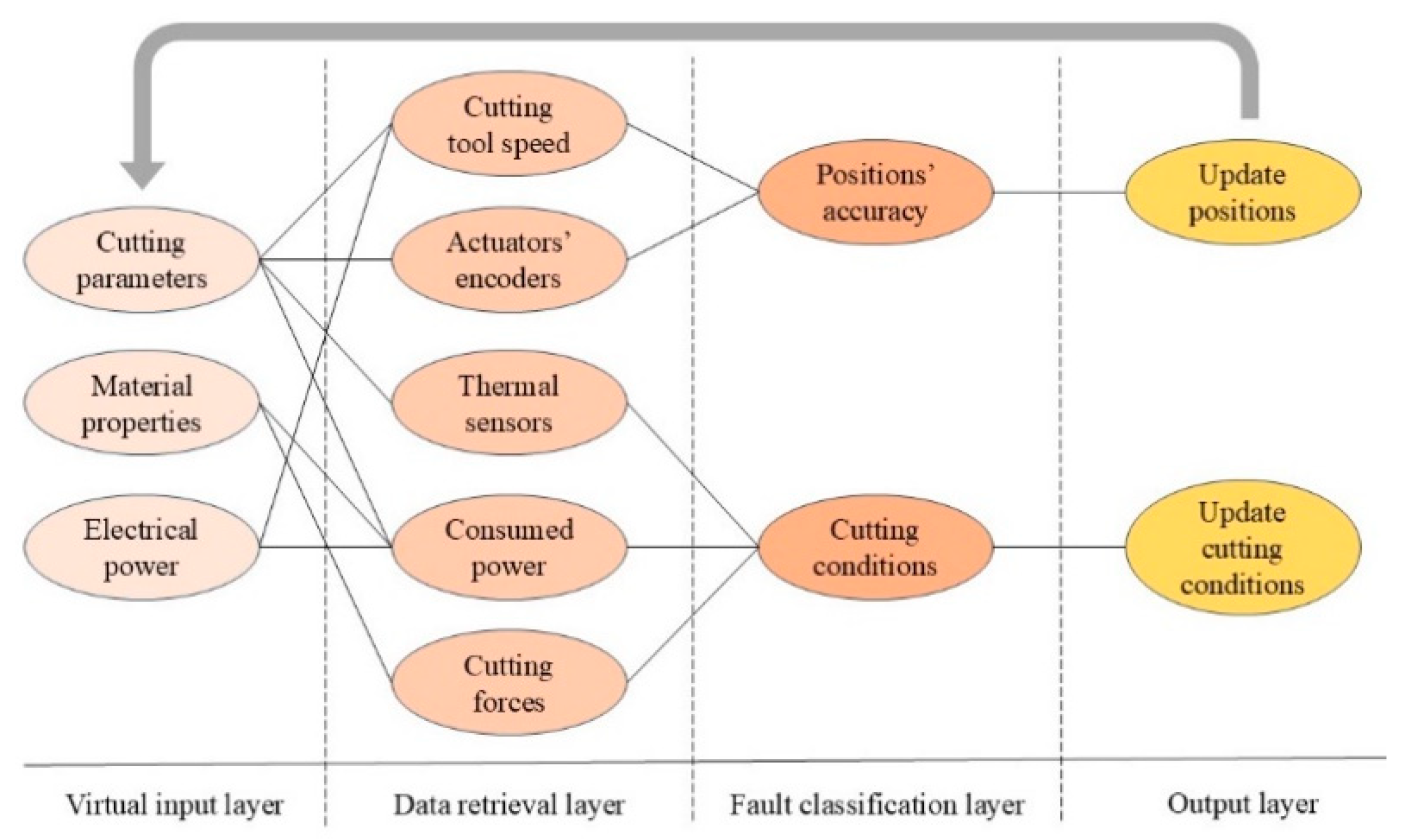

Specific conditions, such as angled cuts and entry/exit procedures, place unique demands on the system. During angled cuts, where the cutting disc tilts around the C-axis, varying forces necessitate precise control. Similarly, cutting forces fluctuate significantly during the entry and exit phases, requiring careful observation to maintain tool integrity and ensure system safety. The Cutting Head plays a central role in managing these conditions. Its digital monitoring architecture, depicted in

Figure 13, showcases actuators and system simulations under demanding scenarios.

The digital twin of the StoneCUT@Line® provides transformative advantages, including proactive fault identification, enhanced operator training, and reliable validation of motion simulation and control systems under varied conditions. These capabilities improve operational reliability, safety, and equipment lifespan, demonstrating the value of digital twin technology in advancing the ornamental stone industry.

The Cockpit integrates the virtual machine controller, the remote physical asset, and the digital twin to form a unified CPS [

28]. The virtual machine controller replicates the actual machine’s console, enabling trainees to interact with identical functional apps, generate CNC trajectories to feed the signal adapter in Siemens NX MCD and gain practical experience. This integration mirrors real-world operations, connecting training and industrial applications seamlessly.

Communication Approaches for Remote Training further enhance the system’s utility. Two primary methods support remote training: (1) Cloud-Based Connections, which offer lower latency and centralized data management but pose higher cybersecurity risks requiring encryption protocols and multi-layered authentication [

13], 2021), and (2) Peer-to-Peer Connections, operating through secure VPN bridges for enhanced reliability and security. The latter is particularly advantageous for industrial shop floors, where localized control and data security are priorities [

14].

For the StoneCUT@Line®, a peer-to-peer connection was chosen due to its security and reliability. The facility’s training cockpit connects to the remote machine through a secure VPN network, utilizing InoServer and Apache Tomcat® to deliver OPC-UA data directly [

39]. This setup eliminates the need for external programmable logic controllers (PLCs), enhancing system compatibility, security, and real-time control.

Beyond workforce training, the digital twin framework supports applications in equipment condition monitoring, enabling real-time diagnostics and predictive maintenance, and equipment optimization, analyzing performance parameters to ensure peak operational capacity [

12]. By linking the training cockpit to the StoneCUT@Line®’s communication shell, this framework empowers SMEs to develop a highly skilled workforce while maximizing equipment utilization and ensuring operational excellence.

This comprehensive approach to motion simulation and control sets the stage for the next phase of this study, where the DT4WFT’s Validation and Preliminary Testing are explored. These efforts assess the framework’s practical application, scalability, and impact on workforce development and industrial innovation.

6. Validation and Preliminary Testing of the Digital Twin Framework for Workforce Training (DT4WFT)

The validation of the DT4WFT was conducted as part of the DSR methodology, emphasizing both empirical and theoretical evaluation to ensure its relevance and applicability [

42]. This study used the StoneCUT@Line® technology as a case study to assess the framework’s ability to address workforce training challenges in Portuguese SMEs within the ornamental stone industry. With advanced 3D modelling, simulation, and predictive maintenance tools, StoneCUT@Line® offered an ideal platform for demonstrating how digital twins can enhance operational efficiency and reduce costs.

A mixed-methods approach, combining interviews and a questionnaire [

20], comprehensively analyzed the framework’s effectiveness. Semi-structured interviews offered qualitative insights into the DT4WFT framework’s practical utility, focusing on managers’ experiences with digital twin technologies, workforce training challenges, and the framework’s potential outcomes. Interview questions explored specific examples of implementation, challenges encountered, and benefits observed. Two guiding questions addressed the perceived impact of digital twins on workforce training challenges and examples of how these technologies bridged resource gaps or facilitated transitions to digital tools. Responses were transcribed, coded, and analyzed thematically, uncovering trends and insights into the framework’s practical relevance.

The structured questionnaire captured quantitative measures of the framework’s impact through three sections: an introduction to contextualize workforce training challenges, an assessment of the DT4WFT’s effectiveness across five dimensions (operator performance, efficiency improvements, lead time reduction, customer satisfaction, and innovation enablement), and participant demographic data to contextualize the findings. Each assessment was rated on a 1-to-5 scale, ensuring consistency and comparability across responses. Pretesting with industry experts refined the questionnaire’s clarity and relevance, achieving a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.81, indicative of high internal consistency. Validity was established through expert reviews, correlation with existing measures of digital maturity and workforce training effectiveness, and face validity evaluations by industry professionals.

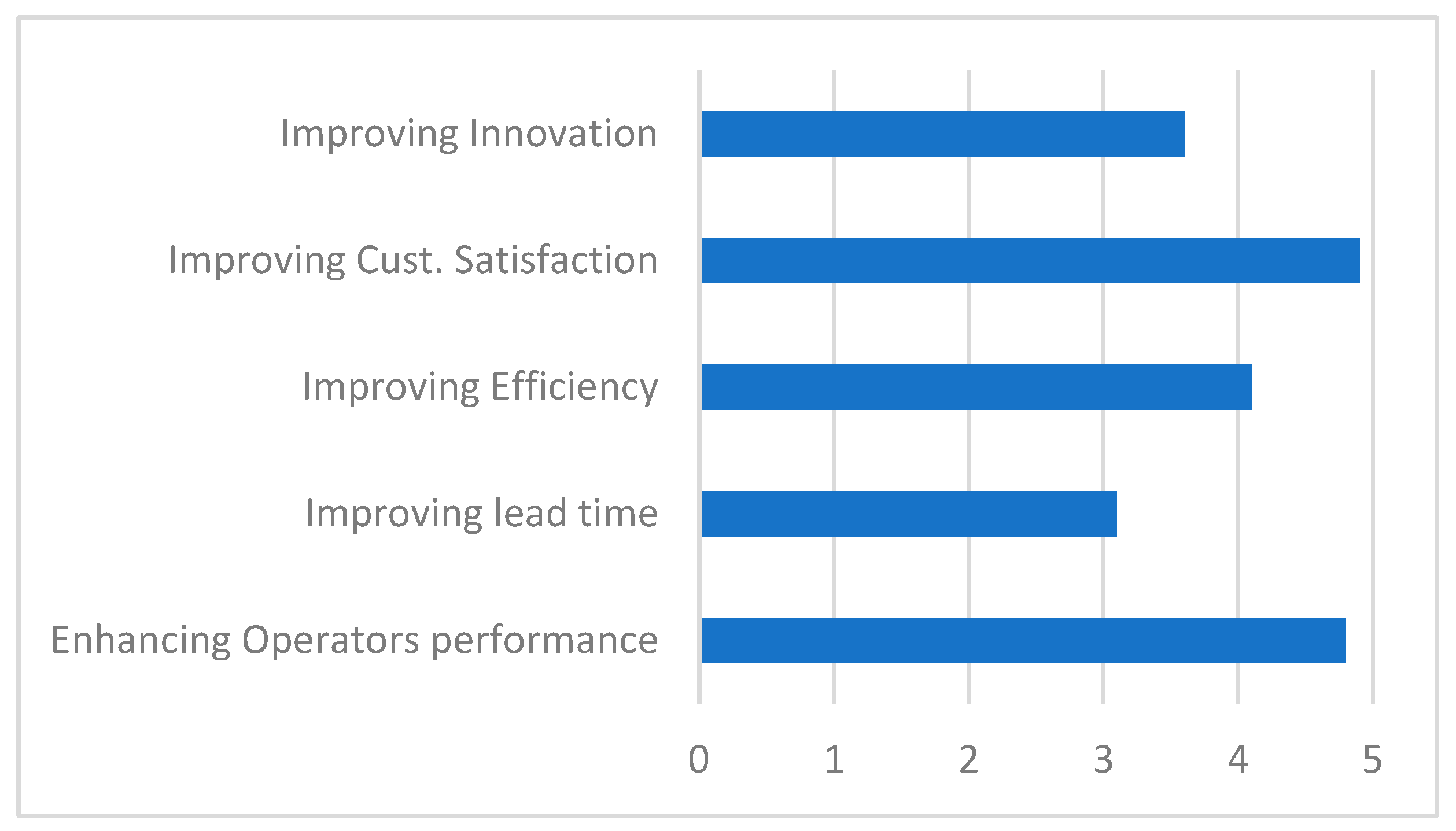

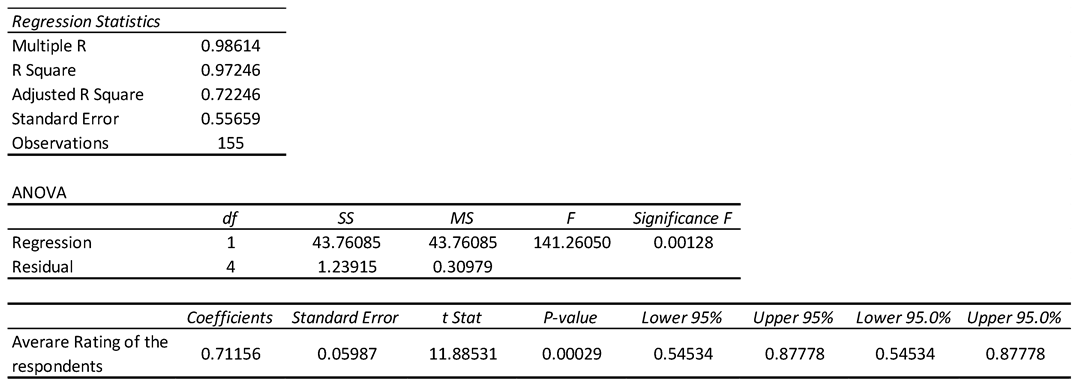

Quantitative findings highlighted strong endorsements of the DT4WFT framework, with respondents rating its impact positively across all dimensions: operator performance (4.2/5), efficiency improvements (4.0/5), lead time reduction (3.8/5), customer satisfaction (4.1/5), and innovation enablement (3.9/5).

Figure 14 illustrates the average ratings, clearly visualisinvisualizationrk’s perceived effectiveness.

Regression analysis reinforced these results, showing a Multiple R of 0.98 and an R Square of 0.97, indicating a strong correlation between the framework’s implementation and perceived benefits. The Adjusted R Square of 0.72 accounted for potential biases, and the low Standard Error of 0.55 underscored prediction precision. ANOVA analysis validated the model’s reliability, with an F-statistic of 141.26 (p < 0.01), and regression coefficients further emphasized the impact of average ratings on perceived benefits, with a coefficient of 0.711 (p = 0.0003).

Table 3 summarizes the summarization statistics, demonstrating the robustness and predictive accuracy of the findings.

Thematic analysis of interview data aligned with these findings, highlighting the framework’s ability to improve training accessibility, operational efficiency, and workforce adaptability. Participants emphasized the emphasizedn of simulation tools and real-time feedback as critical factors in addressing training challenges. High ratings for operator performance and customer satisfaction underscored the framework’s direct benefits, while its contributions to efficiency and innovation demonstrated its strategic advantages for SMEs navigating digital transformation.

This validation confirms the DT4WFT framework’s utility in overcoming workforce training challenges specific to SMEs in the ornamental stone industry. The framework provides a scalable and adaptable model for broader use across similar industrial contexts by aligning theoretical insights with practical applications. The findings also emphasize the importance of tailoring the framework to specific industries, ensuring its relevance and maximizing its

effectiveness. Based on these results, the next section concludes the study by synthesizing its findings, limitations, and recommendations for future research to extend the DT4WFT’s applicability and scalability to other sectors.

6. Conclusions

This study underscores the transformative potential of the DT4WFT in addressing critical workforce training challenges faced by SMEs, particularly within the ornamental stone industry. By integrating advanced digital twin technologies with tailored training processes, the DT4WFT provides a scalable, cost-effective, and immersive solution for skill development. Tools such as Siemens MCD and the StoneCUT@Line® system have demonstrated their potential to enhance operator performance, reduce lead times, improve operational efficiency, and foster innovation. Combining qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys, the mixed-methods validation revealed consistent and robust findings. High ratings across dimensions such as operator performance and customer satisfaction highlight the framework’s capacity to bridge the gap between theoretical advancements in digital twin technology and their practical application in workforce development. The adaptability of the DT4WFT framework extends its relevance beyond the ornamental stone industry, positioning it as a replicable model for other sectors requiring high levels of precision and technical expertise.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the validation relied solely on managers’ perceptions, as the DT4WFT framework has not yet been implemented in real-world training environments. While insightful, this reliance on subjective feedback limits the comprehensiveness of the findings and underscores the need for future research to evaluate the framework’s practical effectiveness through on-the-ground implementation. Additionally, the study was conducted exclusively within the ornamental stone industry, which may restrict the generalizability of its findings to other sectors without further adaptation. Although sufficient for initial insights, the sample size could be expanded to increase statistical power and reliability. Moreover, the study focused on immediate training outcomes, leaving long-term impacts on workforce skills, operational efficiency, and organizational organizational unexplored. Finally, the reliance on advanced systems like StoneCUT@Line® and Siemens NX MCD may present accessibility challenges for resource-constrained SMEs, raising questions about the framework’s scalability in diverse industrial contexts.

Future research should address these limitations to enhance the framework’s applicability and impact. Implementing and testing the DT4WFT in real-world settings across diverse industries, such as healthcare, construction, and high-tech manufacturing, would provide critical insights into its adaptability and refine its design. Longitudinal studies should assess sustained impacts on workforce skills, operational efficiency, and organizational organization. Expanding the sample size and geographic diversity of participants would improve the robustness of findings and broaden their relevance. Incorporating emerging technologies, such as AI-driven analytics, augmented reality, and IoT connectivity, could further enhance the framework’s predictive and adaptive capabilities. Future iterations of the DT4WFT should prioritize cost-effective, modular designs to democratize access for SMEs with limited resources. Lastly, fostering partnerships between governments, industries, and academic institutions could accelerate the adoption of digital twin-based training solutions, ensuring their widespread applicability and transformative impact across industrial sectors navigating digital transformation.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- E. den Hartigh, C. C. M. Stolwijk, J. R. Ortt, and L. M. Punter, “Configurations of digital platforms for manufacturing: An analysis of seven cases according to platform functions and types,” Electron. Mark., vol. 33, no. 1, p. 30, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Cremonini, J. O. C. Vasco, M. R. C. Gaspar, and A. da Silva, “Digital Twins and the Ornamental Stone Industry: Key Factors,” Comun. Geológicas 111, 91-100 ISSN 0873-948X; e-ISSN 1647-581X, 2023, [Online]. Available: https://dspace.uevora.pt/rdpc/handle/10174/36970?mode=full9.

- S. Mariani, M. Picone, and A. Ricci, “Agents and Digital Twins for the engineering of Cyber-Physical Systems: opportunities, and challenges,” Ann. Math. Artif. Intell., vol. 92, no. 4, pp. 953–974, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, Y. Sun, X. Liu, and Y. Zheng, “A Digital-Twin-Assisted Fault Diagnosis Using Deep Transfer Learning,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 19990–19999, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Silva, A. Dionisio, and I. Almeida, “Enabling Cyber-Physical Systems for Industry 4.0 operations: A Service Science Perspective,” Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng., vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 838–846, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Di Bella, A. Katsinis, J. Lagüera-González, L. Odenthal, M. Hell, and B. Lozar, “Annual Report on European SMEs 2022/2023,” 2023.

- A. S. Kulinan, M. Park, P. P. W. Aung, G. Cha, and S. Park, “Advancing construction site workforce safety monitoring through BIM and computer vision integration,” Autom. Constr., vol. 158, p. 105227, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Lyons, K. Vidamour, R. Jain, and M. Sutherland, “Developing an understanding of lean thinking in process industries,” Prod. Plan. Control, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 475–494, 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. Gillani, K. A. Chatha, S. S. Jajja, D. Cao, and X. Ma, “Unpacking Digital Transformation: Identifying key enablers, transition stages and digital archetypes,” Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, vol. 203, p. 123335, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Tao, L. Chunhui, X. Hui, Z. Zhiheng, and W. Guangyue, “A review of digital twin intelligent assembly technology and application for complex mechanical products,” Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol., vol. 127, no. 9–10, pp. 4013–4033, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Alexopoulos, N. Nikolakis, and G. Chryssolouris, “Digital twin-driven supervised machine learning for the development of artificial intelligence applications in manufacturing,” Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf., vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 429–439, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Stavropoulos and A. Papacharalampopoulos, “Designing a digital twin for micromanufacturing processes,” Adv. Mech. Eng., vol. 14, no. 6, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Schneider, M. Wendl, S. Kucek, and M. Leitner, “A Training Concept Based on a Digital Twin for a Wafer Transportation System,” in 2021 IEEE 23rd Conference on Business Informatics (CBI), Sep. 2021, pp. 20–28. [CrossRef]

- T. Kaarlela, S. Pieska, and T. Pitkaaho, “Digital Twin and Virtual Reality for Safety Training,” in 2020 11th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Sep. 2020, pp. 000115–000120. [CrossRef]

- A. Silva and A. Pata, “Value Creation in Technology Service Ecosystems - An Empirical Case Study,” in Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering, 2023, pp. 26–36.

- K. Peffers, T. Tuunanen, M. A. Rothenberger, and S. Chatterjee, “A Design Science Research Methodology for Information Systems Research,” J. Manag. Inf. Syst., vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 45–77, Dec. 2007. [CrossRef]

- A. Da Silva and A. Cardoso, “Design Science for Networks Designing: A Service-Dominant Logic Approach,” Eur. Conf. Res. Methodol. Bus. Manag. Stud., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 35–42, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. da Silva and A. J. Marques Cardoso, “Designing the future of coopetition: An IIoT approach for empowering SME networks,” Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol., vol. 135, no. 1–2, pp. 747–762, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. vom Brocke, A. Hevner, and A. Maedche, “Introduction to Design Science Research,” no. September, 2020, pp. 1–13.

- N. V. Ivankova and V. L. Plano Clark, “Teaching mixed methods research: using a socio-ecological framework as a pedagogical approach for addressing the complexity of the field,” Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 409–424, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. da Silva and I. Almeida, “Towards INDUSTRY 4.0 | a case STUDY in ornamental stone sector,” Resour. Policy, vol. 67, p. 101672, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Kasmi, S. M. Amir, A. Aman, B. Haruna, and A. F. Usman, “Implementation of Science and Technology for Regional Development: Improving the Quality of Ornamental Fish Production with a Concentration of Clove Oil Alternative to Sustainable Fishing Gear,” Mattawang J. Pengabdi. Masy., vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 370–379, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chioma Ann Udeh, Omamode Henry Orieno, Obinna Donald Daraojimba, Ndubuisi Leonard Ndubuisi, and Osato Itohan Oriekhoe, “Big Data Analytics: a Review of Its Transformative Role in Modern Business Intelligence,” Comput. Sci. IT Res. J., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 219–236, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhu, Z. Lin, J. Huang, L. Zheng, and B. He, "A digital twin-based machining motion simulation and visualization mvisualizationtem for milling robot," Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol., vol. 127, no. 9–10, pp. 4387–4399, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Hagedorn, T. Riedelsheimer, and R. Stark, “PROJECT-BASED LEARNING IN ENGINEERING EDUCATION – DEVELOPING DIGITAL TWINS IN A CASE STUDY,” Proc. Des. Soc., vol. 3, pp. 2975–2984, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. I. Erdei, R. Krakó, and G. Husi, “Design of a Digital Twin Training Centre for an Industrial Robot Arm,” Appl. Sci., vol. 12, no. 17, p. 8862, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Legner, T. Pentek, and B. Otto, “Accumulating Design Knowledge with Reference Models: Insights from 12 Years’ Research into Data Management,” J. Assoc. Inf. Syst., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 735–770, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. da Silva and A. J. M. Cardoso, “Coopetition with the Industrial IoT: A Service-Dominant Logic Approach,” Appl. Syst. Innov., vol. 7, no. 3, p. 47, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Creswell and P. Clark, Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 2017.

- V. A. Arowoiya, R. C. Moehler, and Y. Fang, “Digital twin technology for thermal comfort and energy efficiency in buildings: A state-of-the-art and future directions,” Energy Built Environ., vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 641–656, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Ke et al., “Intelligent machine plus production line digital twin model construction technology,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 2478, no. 10, p. 102011, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Itohan Oviawe, “Bridging Skill Gap to Meet Technical, Vocational Education and Training School-Workplace Collaboration in the 21.,” Int. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. Res., vol. 3, no. 1, p. 7, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Berriche, F. Mhenni, A. Mlika, and J.-Y. Choley, “Towards Model Synchronization for Consistency Management of Mechatronic Systems,” Appl. Sci., vol. 10, no. 10, p. 3577, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Y. Zhong, X. Xu, E. Klotz, and S. T. Newman, “Intelligent Manufacturing in the Context of Industry 4.0: A Review,” Engineering, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 616–630, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A.-R. Sadeghi, C. Wachsmann, and M. Waidner, “Security and privacy challenges in industrial internet of things,” in Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Design Automation Conference, Jun. 2015, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Madruga, É. Renato Silva, J. Francisco Moreira Pessanha, H. Henriques de Arruda, and A. Naked Haddad, “From IFCX to CXMMI: Validation and Evolution of a Customer Experience Management Maturity Model,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, no. July, pp. 119350–119370, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Yazdinejad, B. Zolfaghari, A. Dehghantanha, H. Karimipour, G. Srivastava, and R. Parizi, “Accurate threat hunting in industrial internet of things edge devices,” Digital Communications and Networks, vol. 9, no. 5. pp. 1123–1130, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Silva and M. Gil, "Industrial processes optimization inoptimizationketplace context: A case study in ornamental stone sector," Results Eng., vol. 7, no. April, p. 100152, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Hoppe, “OPC Unified Architecture-Interoperability for Industrie 4.0 and the Internet of Things,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://opcfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/OPC-UA-Interoperability-For-Industrie4-and-IoT-EN.pdf.

- M. Borchert and C. Bonefeld-Dahl, “A Stronger Digital Europe: Our Call to Action Towards 2025,” DigitalEurope, 2018, [Online]. Available: https://www.digitaleurope.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/DIGITALEUROPE-–-Our-Call-to-Action-for-A-STRONGER-DIGITAL-EUROPE.pdf.

- M. S. Mahmoud, M. Sabih, and M. Elshafei, “Using OPC technology to support the study of advanced process control,” ISA Trans., vol. 55, pp. 155–167, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Creswell, Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).